Abstract

Background

Conservative therapy of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) consists largely of compression treatment. However, this often causes discomfort and has been associated with poor compliance. Therefore, oral drug treatment is an attractive option. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2002 and updated in 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010.

Objectives

To review the efficacy and safety of oral horse chestnut seed extract (HCSE) versus placebo, or reference therapy, for the treatment of CVI.

Search methods

For this update the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Review Group searched their Specialised Register (last searched June 2012) and CENTRAL (Issue 5, 2012). For the previous versions of the review the authors searched AMED (inception to July 2005) and Phytobase (inception to January 2001) for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of HCSE for CVI. Manufacturers of HCSE preparations and experts on the subject were contacted for published and unpublished material. There were no restrictions on language.

Selection criteria

RCTs comparing oral HCSE mono‐preparations with placebo, or reference therapy, in people with CVI. Trials assessing HCSE as one of several active components in a combination preparation, or as a part of a combination treatment, were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors independently selected the studies and, using a standard scoring system, assessed methodological quality and extracted data. Disagreements concerning evaluation of individual trials were resolved through discussion.

Main results

Overall, there appeared to be an improvement in CVI related signs and symptoms with HCSE compared with placebo. Leg pain was assessed in seven placebo‐controlled trials. Six reported a significant reduction of leg pain in the HCSE groups compared with the placebo groups, while another reported a statistically significant improvement compared with baseline. One trial suggested a weighted mean difference (WMD) of 42.4 mm (95% confidence interval (CI) 34.9 to 49.9) measured on a 100 mm visual analogue scale. Leg volume was assessed in seven placebo‐controlled trials. Six trials (n = 502) suggested a WMD of 32.1ml (95% CI 13.49 to 50.72) in favour of HCSE compared with placebo. One trial indicated that HCSE may be as effective as treatment with compression stockings. Adverse events were usually mild and infrequent.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence presented suggests that HCSE is an efficacious and safe short‐term treatment for CVI. However, several caveats exist and larger, definitive RCTs are required to confirm the efficacy of this treatment option.

Keywords: Humans; Aesculus; Aesculus/adverse effects; Seeds; Administration, Oral; Chronic Disease; Leg; Leg/blood supply; Pain; Pain/drug therapy; Phytotherapy; Phytotherapy/adverse effects; Phytotherapy/methods; Plant Extracts; Plant Extracts/adverse effects; Plant Extracts/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Treatment Outcome; Venous Insufficiency; Venous Insufficiency/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Horse chestnut seed extract for long‐term or chronic venous insufficiency

Poor blood flow in the veins of the legs, known as chronic venous insufficiency, is a common health problem, particularly with ageing. It can cause leg pain, swelling (oedema), itchiness (pruritus) and tenseness as well as hardening of the skin (dermatosclerosis) and fatigue. Wearing compression stockings or socks helps but people may find them uncomfortable and do not always wear them. A seed extract of horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum L.) is a herbal remedy used for venous insufficiency. Seventeen randomised controlled trials were included in the review. In all trials the extract was standardised to escin, which is the main active constituent of horse chestnut seed extract.

Overall, the trials suggested an improvement in the symptoms of leg pain, oedema and pruritus with horse chestnut seed extract when taken as capsules over two to 16 weeks. Six placebo‐controlled studies (543 participants) reported a clear reduction of leg pain when the herbal extract was compared with placebo. Similar results were reported for oedema, leg volume, leg circumference and pruritis. The other studies which compared the extract with rutosides (four trials), pycnogenol (one trial) or compression stockings (two trials) reported no significant differences between the therapies for leg pain or a symptom score that included leg pain. The herbal extract was equivalent to rutosides, pycnogenol and compression on the other symptoms with the exception that it was inferior to pycnogenol on oedema.

The adverse events reported (14 trials) were mild and infrequent. They included gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, nausea, headache and pruritus, from six studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is one of the commonest conditions afflicting humans. About 10‐15% of men and 20‐25% of women present signs and symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of CVI, indicating that being female is an important risk factor, as well as age, geographical location and race (Callam 1992; Callam 1994). This condition is characterised by chronic inadequate drainage of venous blood and venous hypertension, which results in leg oedema (swelling), dermatosclerosis (hardening of the skin) and feelings of pain, fatigue and tenseness in the lower extremities (Spraycar 1995). Patients often require hospitalisation and surgery, for instance, for symptomatic varicose veins (London 2000; Rigby 2002).

Description of the intervention

Mechanical compression is the treatment of choice for this condition (Partsch 1991). However, compression therapy, for example, using compression stockings often causes discomfort and has been associated with poor compliance. Oral drug treatment is therefore an attractive option.

How the intervention might work

Horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum L.) has traditionally been used as a herbal remedy for treating CVI (Bombardelli 1996). The seed extract of Aesculus hippocastanum L. (HCSE) contains escin, a triterpenic saponin, as its active component (Guillaume 1994; Lorenz 1960; Schrader 1995). Escin has been shown to inhibit the activity of hyaluronidase, an enzyme involved in proteoglycan degradation (Facino 1995). The accumulation of leucocytes (white blood cells) in CVI‐affected limbs (Moyses 1987; Thomas 1988) and subsequent activation and release of such enzymes (Sarin 1993) is considered to be an important pathophysiological mechanism of CVI.

Why it is important to do this review

Regardless of the postulated mechanism of action, the most important clinical questions are whether HCSE is safe and efficacious for treating patients with CVI.

Objectives

To review the evidence from rigorous clinical trials assessing the efficacy and safety of HCSE versus placebo, or reference therapy, for the symptomatic treatment of CVI.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised, controlled trials (RCTs), i.e. trials with a randomised generation of allocation sequences. Studies assessing acute effects only were excluded. No restrictions regarding the language of publication were imposed (Egger 1997).

Types of participants

Studies were included if participants were patients with CVI. Studies that did not use adequate diagnostic criteria (e.g. Widmer 1978) were excluded.

Types of interventions

Trials were included if they compared oral preparations containing HCSE as the only active component (mono‐preparation) with placebo or reference therapy. Trials assessing HCSE as one of several active components in a combination preparation or as a part of a combination treatment were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Trials using clinical outcome measures were included. Studies focusing exclusively on physiological parameters were excluded.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measures were CVI‐related symptoms (e.g. leg pain, pruritus (itching), oedema (swelling)).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were, leg volume and leg circumference at ankle and calf. Adverse events were assessed as reported in the included trials.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched June 2012) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2012, Issue 5, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com. See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

For the original review Phytobase inception to January 2001 and AMED were searched using the terms listed in Appendix 2 .

Searching other resources

Manufacturers of HCSE preparations and experts on the subject were contacted and asked to contribute published and unpublished material. Furthermore, our own files were scanned. The bibliographies of the studies retrieved were searched for further trials.

Data collection and analysis

Max Pittler and Edzard Ernst independently screened and selected trials for inclusion, assessed their methodological quality and extracted data. Disagreements at any of these stages were resolved by discussion.

Selection of studies

Trials were selected according to the criteria outlined above under Criteria for considering studies for this review.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted independently by both authors using a data extraction form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The following data were extracted:

Participant characteristics: age, gender.

Methods used: randomisation, double‐blinding, concealment of treatment allocation, description of drop outs.

Interventions: oral preparations containing HCSE as the only active component (mono‐preparation), compared with placebo or comparator medication(s).

Outcome measures: CVI‐related symptoms (e.g. leg pain, pruritus, oedema), leg volume, circumference at ankle and calf, and adverse events.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality was assessed using the Jadad score (Jadad 1996) and the Cochrane risk of bias tool. The Jadad score was applied independently by both authors and disagreements were resolved by discussion. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was applied by the first author only.

Measures of treatment effect

The effect measures of choice in case of dichotomous data were odds ratio (improvement of leg pain, improvement of oedema, improvement of pruritus), in case of continuous data the mean difference (reduction of leg pain, reduction of oedema, reduction of lower leg volume, reduction of circumference at ankle, reduction of circumference at calf, improvement of symptom score, leg volume).

Unit of analysis issues

There were no special issues such as carry‐over effects or period effects with the analysis of the three cross over trials included in this review.

Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan Analyses 1.0.4. It uses the inverse of the variance to assign a weight to the mean of the within‐study treatment effect. For most studies, however, the information was insufficient. The Cochrane Collaboration suggests imputing the variance of the change by assuming a correlation factor between pre‐intervention and post‐intervention values. The variance of the change was imputed using a correlation factor of 0.4, which was then used to assign a weight to the mean of the within‐study treatment effect.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The chi‐square test for heterogeneity tested whether the distribution of the results was compatible with the assumption that inter‐trial differences were attributable to chance variation alone.

Data synthesis

Data‐pooling of continuous data was performed using the weighted mean difference; for dichotomous data the odds ratio was used. Summary estimates of the treatment effect were calculated using a random effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There are no planned subgroup analyses as yet. Subgroup analyses to investigate possible heterogeneity will be performed in future if more data become available.

Sensitivity analysis

There are no planned sensitivity analyses as yet. Sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the main analysis will be performed in future if more data become available.

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

Seventeen trials met the above mentioned inclusion criteria (Cloarec 1992; Diehm 1992; Diehm 1996a; Diehm 2000; Erdlen 1989; Erler 1991; Friederich 1978; Kalbfleisch 1989; Koch 2002; Lohr 1986; Morales 1993; Neiss 1976; Pilz 1990; Rehn 1996; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a). Of these, ten were placebo‐controlled; two compared HCSE against reference treatment with compression stockings and placebo (Diehm 1996a; Diehm 2000); four were controlled against reference medication with O‐ß‐hydroxyethyl rutosides (HR) (Erdlen 1989; Erler 1991; Kalbfleisch 1989; Rehn 1996) and one was controlled against medication with pycnogenol (Koch 2002). In all trials the extract was standardised to escin which is the main active constituent of HCSE.

Excluded studies

Fourteen trials were excluded (Bisler 1986; Boehm 1989; Coninx 1974; Dols 1987; Dustmann 1984; Hirsch 1982; Krc¡lek 1973; Lochs 1974; Marhic 1986; Nill 1970; Neumann‐Mangoldt; Paciaroni 1982; Pauschinger 1987; Zuccarelli 1986). The trial by (Pauschinger 1987;) used non‐clinical outcome measures; seven tested HCSE as a component in combination preparations or combination treatments (Boehm 1989; Coninx 1974; Dols 1987; Dustmann 1984; Hirsch 1982; Neumann‐Mangoldt; Zuccarelli 1986); and two focused exclusively on physiological parameters (Bisler 1986; Lochs 1974). The four additional trials identified through update searches were excluded because they used topical treatment (Marhic 1986; Paciaroni 1982), did not asses clinical outcomes (Nill 1970) or tested a combination preparation (Krc¡lek 1973).

Risk of bias in included studies

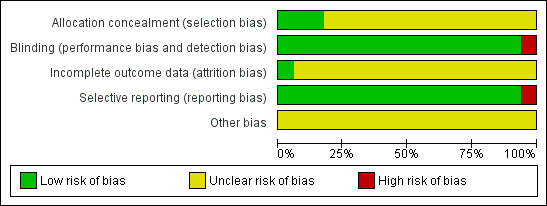

Figure 1 displays the risk of bias associated with the included studies.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Key data from the included trials, including scores for quality and allocation concealment, are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Allocation

Most trials did not report on allocation concealment and it is therefore unclear to what extent bias was introduced. Only three trials (Erdlen 1989; Pilz 1990; Steiner 1986) reported adequate allocation concealment.

Blinding

Only one of the included RCTs was not double‐blinded (Koch 2002). All of the included studies administered HCSE in capsules, permitting the preparation of adequate placebos. The likelihood that bias was introduced through blinding or the lack thereof is minimal.

Incomplete outcome data

In all but three studies (Friederich 1978; Steiner 1990a; Rehn 1996) it is unclear whether incomplete outcome data were addressed. It is therefore unclear to what extent bias was introduced.

Selective reporting

None of the included trials showed evidence of selective reporting and therefore it is unlikely that bias was introduced here. In the included trials, all of the pre‐stated outcomes were reported.

Effects of interventions

The majority of the included studies diagnosed the patients according to the classification by Widmer (Widmer 1978). Fourteen trials reported inclusion criteria for CVI patients relating to this classification. Eighty‐two percent of the participants in these trials were categorised into CVI stages I, II or I‐II. Three trials, comprising 22% of the total number of participants did not refer to this classification. Overall, the included placebo‐controlled trials suggested an improvement in the CVI related symptoms of leg pain, oedema and pruritus.

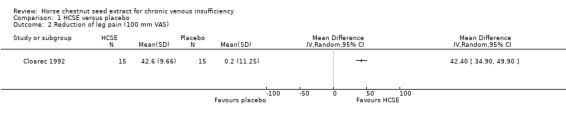

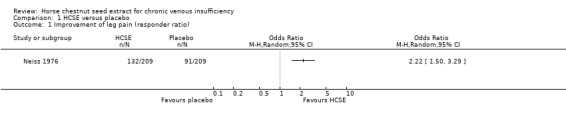

Leg pain

Leg pain was assessed in seven placebo‐controlled trials (Cloarec 1992; Friederich 1978; Lohr 1986; Morales 1993; Neiss 1976; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1990a). Six studies (n = 543) reported a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.05) of leg pain on various measurement scales in participants treated with HCSE compared with placebo, while another reported an improvement compared with baseline (Steiner 1990a). One study (Cloarec 1992), reported adequate data which could be included within RevMan Analyses (Analysis 1.2), assessed on a 100 mm VAS, suggesting a weighted mean difference (WMD) of 42.40 mm (95% confidence interval (CI) 34.90 to 49.90). Other studies which compared HCSE with HR (Kalbfleisch 1989), pycnogenol (Koch 2002) or compression (Diehm 2000) reported no significant inter group differences for leg pain or a symptom score including leg pain.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 2 Reduction of leg pain (100 mm VAS).

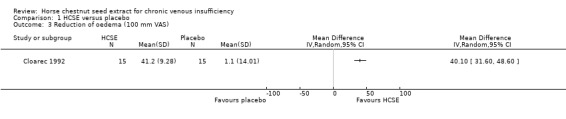

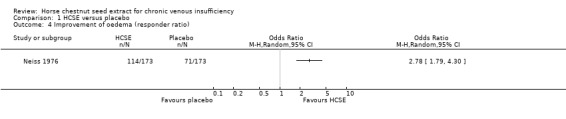

Oedema

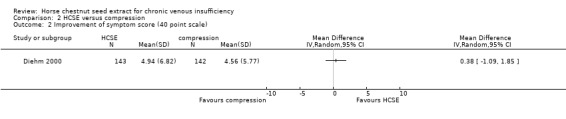

Oedema was assessed in six placebo‐controlled trials (Cloarec 1992; Friederich 1978; Lohr 1986; Morales 1993; Neiss 1976; Steiner 1990a). Four trials (n = 461) reported a statistically significant reduction of oedema in participants treated with HCSE compared with placebo, whilst one (Steiner 1990a) reported an improvement compared with baseline. One study (Cloarec 1992) reported adequate data suggesting a WMD of 40.10 mm (95% CI 31.60 to 48.60) in favour of HCSE assessed on a 100 mm VAS. Another study (Koch 2002) reported that HCSE was inferior to pycnogenol, whereas a further trial (Diehm 2000) reported no significant differences for a score including the symptom oedema compared with compression. Oedema provocation before and after treatment with HCSE revealed oedema protective effects (Erler 1991).

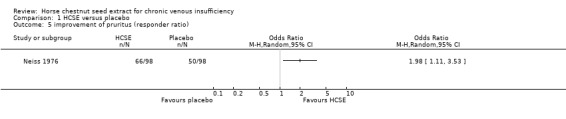

Pruritus

Pruritus was assessed in eight placebo‐controlled trials (Diehm 1992; Friederich 1978; Lohr 1986; Morales 1993; Neiss 1976; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a). Four trials (n = 407) suggested a statistically significant reduction of pruritus in participants treated with HCSE compared with placebo (P < 0.05). Two trials (Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a) suggested a statistically significant difference in favour of HCSE compared with baseline (P < 0.05). Another trial (Kalbfleisch 1989), which compared HCSE with HR, but failed to include a placebo group, seemed to corroborate these findings. A further trial (Diehm 2000) reported no significant differences for a score including the symptom pruritus compared with compression.

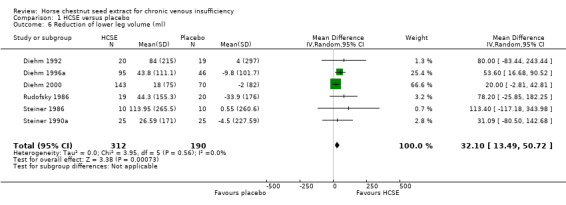

Leg volume

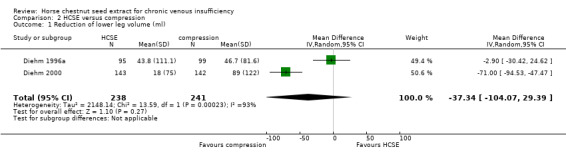

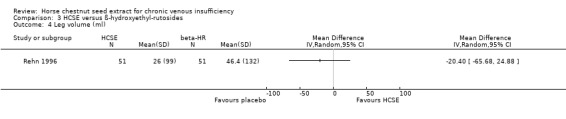

Leg volume was assessed in seven placebo‐controlled trials (Diehm 1992; Diehm 1996a; Diehm 2000; Lohr 1986; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a). All of these studies used water displacement plethysmometry to measure this outcome. Meta‐analysis of six trials (Diehm 1992; Diehm 1996a; Diehm 2000; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a; n = 502) suggested a WMD of 32.1ml (95% CI 13.49 to 50.72) in favour of HCSE compared with placebo (Analysis 1.6) (pooled standardised mean difference 0.34; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.52). One trial (Rehn 1996) reported findings suggesting that HCSE was equivalent to HR, and another (Diehm 1996a, n = 194) suggested that it may be as efficacious as treatment with compression stockings (WMD ‐2.90 ml; 95% CI ‐30.42 to 24.62). Significant beneficial effects for CVI patients were reported in trials which administered HCSE standardised to 100‐150 mg escin daily. Three studies, using 100 mg escin daily, reported a statistically significant reduction of mean leg volume after two weeks of treatment compared with placebo (P < 0.01) (Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a). Persistence of treatment effects was suggested by one study (Rehn 1996). At the end of a six‐week follow‐up period mean leg volume was similar to post‐treatment values.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 6 Reduction of lower leg volume (ml).

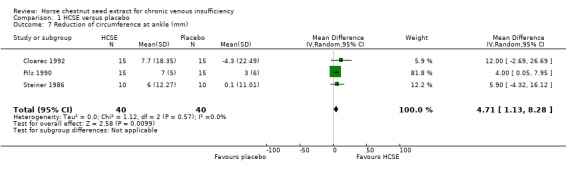

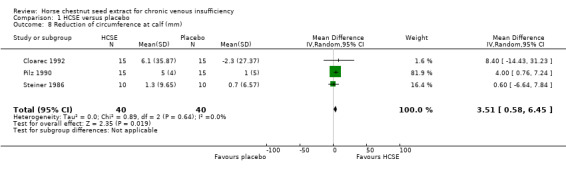

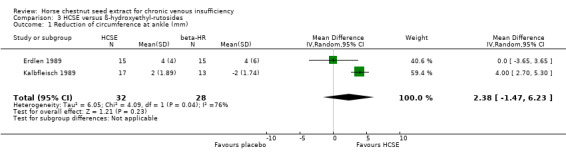

Circumference

Circumference at calf and ankle was assessed in seven placebo‐controlled trials (Cloarec 1992; Diehm 1992; Lohr 1986; Pilz 1990; Rudofsky 1986; Steiner 1986; Steiner 1990a). Five studies (n = 172) suggested a statistically significant reduction at the ankle, and three (n = 112) at the calf in favour of HCSE compared with placebo. At the ankle, meta‐analysis of three trials (Cloarec 1992; Pilz 1990; Steiner 1986), which reported adequate data suggested a statistically significant reduction in favour of HCSE compared with placebo (WMD 4.71 mm; 95% CI 1.13 to 8.28; pooled standardised mean difference 0.60; 95% CI 0.15 to 1.05) (Analysis 1.7). At the calf, the pooled analysis of three trials (Cloarec 1992; Pilz 1990; Steiner 1986), suggested a statistically significant reduction in favour of HCSE compared with placebo (WMD 3.51 mm; 95% CI 0.58 to 6.45; pooled standardised mean difference 0.42; 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.88).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 7 Reduction of circumference at ankle (mm).

Adverse events

Fourteen studies reported on adverse events. Four studies (Cloarec 1992; Diehm 1996a; Pilz 1990; Rudofsky 1986) reported that there were no treatment‐related adverse events in the HCSE group. Gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, nausea, headache and pruritus were reported as adverse events in six studies (Diehm 2000; Friederich 1978; Morales 1993; Neiss 1976; Rehn 1996; Steiner 1990a). The frequency ranged from 1 to 36% of treated patients. Four other studies (Diehm 1992; Koch 2002; Lohr 1986; Steiner 1986) reported good tolerability with HCSE.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The results of our systematic review suggest, overall, that compared with placebo and reference treatment, HCSE is an effective treatment option for CVI. The adverse events reported in the reviewed trials were mild and infrequent. Thus, according to the available data the risk/benefit ratio of HCSE for the short term treatment of CVI is positive.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In an attempt to locate all randomised trials of oral preparations containing HCSE, 29 trials were identified of which 17 could be included. It is noteworthy that one unpublished trial was supplied by a manufacturer of HCSE‐containing preparations, while a second unpublished trial was identified in a report by another author (Diehm 2000). The search strategy for this review involved several databases including those with a focus on the European and American literature, as well as manual searching and contact with experts and manufacturers. Moreover, searching was not restricted in terms of publication language.

The conservative treatment of CVI comprises a number of other therapeutic modalities. Compression therapy improves venous return and is widely accepted as the treatment of choice (Tooke 1996). In combination with heparin, it prevents venous stasis and reduces the risk of deep vein thrombosis. O‐ß‐hydroxyethyl rutosides are reported to have beneficial short‐term effects by reducing oedema and relieving symptoms of CVI. However, their efficacy during long‐term use has yet to be established (Wadworth 1992). Ruscus extract decreases capillary filtration rate in healthy volunteers and people with CVI (Rudofsky 1991). A review has concluded that combined treatment using oedema protective agents and compression therapy improves CVI to a greater extend than either treatment alone (Diehm 1996b).

The mechanism of action involved in the observed effects when HCSE is administered may be of interest. The active component of HCSE is the saponin escin (Lorenz 1960). This has been shown to inhibit the activity of elastase and hyaluronidase in vitro. Both these enzymes are involved in proteoglycan degradation (proteoglycan constitutes part of the capillary endothelium and is the main component of the extravascular matrix) (Facino 1995). The accumulation of leucocytes (white blood cells) in CVI‐affected limbs (Moyses 1987; Thomas 1988), and subsequent activation and release of such enzymes (Sarin 1993), is considered to be an important pathophysiological mechanism of CVI. An earlier study found increased serum activity of proteoglycan hydrolases in patients with CVI that were reduced with HCSE (Kreysel 1983). HCSE treatment may shift the equilibrium between degradation and synthesis of proteoglycans towards a net synthesis, thus preventing vascular leakage. This hypothesis has been supported by animal experiments (Enghofer 1984). Using electron microscopy, the author demonstrated a marked reduction in vascular leakage after treatment with HCSE. Uncertainty exists regarding the effects of HCSE on venous tone. In vitro, HCSE increases venous pressure of normal and pathologically altered veins. This is corroborated by studies in laboratory animals, which demonstrate an increase in venous pressure and venous flow after HCSE administration (Guillaume 1994). However, studies on humans have failed to replicate effects on venous capacity (Bisler 1986; Rudofsky 1986).

Quality of the evidence

All randomised double‐blind trials included in this review scored at least one out of five points for methodological quality. Nonetheless, the extent of methodological rigour varied between studies. Only three trials (Diehm 1996a; Rehn 1996; Rudofsky 1986) reported data indicating that compliance was monitored. The majority of studies suffered from a small sample size with drop‐out rates ranging from zero to 19.5%.

Potential biases in the review process

Despite systematic efforts to find all studies on the subject, it is conceivable that some were not uncovered. Several forms of publication and location bias exist (Egger 1998) including the tendency for negative trials to remain unpublished (Easterbrook 1991), for positive findings to be published in English language journals (Egger 1997) and for some European journals to not be indexed in major medical databases (Nieminen 1999). There is also evidence that positive findings may be over‐represented in complementary medicine journals (Ernst 1997; Schmidt 2001) and that these journals favour positive conclusions at the expense of methodological quality (Pittler 2000). Therefore, there is a possibility that treatment effects are exaggerated. Overall, we are confident that the search strategy that we used and the therefore the completeness of the evidence minimised bias. However, more trials assessing the efficacy of HCSE in larger patient samples using adequate outcome measures and systematic investigations of its safety are still required (Ernst 2001).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

These findings update and extend the findings of previous systematic reviews (Pittler 1998; Pittler 2004; Siebert 2002). In the reviewed trials adverse events were mild and infrequent, which supports the findings of post‐marketing surveillance studies (Greeske 1996; Leskow 1996) reporting pruritus, nausea, gastrointestinal complaints, headache and dizziness in 43 of 6183 patients (0.7%) treated with HCSE.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence presented suggests that HCSE is an efficacious and safe short‐term treatment for CVI. However, caveats exist and more rigorous, large RCTs are required to assess the efficacy of this treatment option.

Implications for research.

Future studies should be rigorously executed and reported in a uniform manner following the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001). Detailed description of randomisation and double‐blinding procedures should be included in the report. More controlled clinical trials are needed, which should include larger numbers of participants and assess HCSE particularly for long‐term use and as an adjunct to compression treatment.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 October 2012 | Review declared as stable | No new included studies have been identified since 2005. This Cochrane review has been marked stable and will only be updated when new studies are identified. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 1, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 June 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches re‐run, no new trials found. The review was assessed as up to date. |

| 19 June 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches re‐run, no new trials found. Minor copy edits made, conclusions not changed. |

| 27 July 2010 | New search has been performed | Searches re‐run and four additional studies were excluded from the review. Risk of bias tables added to the Included studies and minor changes made to the text of the review. |

| 22 September 2008 | New search has been performed | Searches re‐run, no new trials found. Minor changes to the text of the review. |

| 22 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 15 February 2007 | Amended | Search dates changed, no new trials found. Plain language summary added and minor copy edits. |

| 15 November 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Substantive amendment. One additional trial included but no change to conclusions. |

| 25 February 2004 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Substantive update. One additional trial included but no change to conclusions. |

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group ran the searches of CENTRAL and the Specialised Register. The Plain Language Summary was provided by the Cochrane Consumer Network.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL 2012

| #1 | MeSH descriptor Venous Insufficiency explode all trees | 337 |

| #2 | insuffic* or CVI or isch* | 30384 |

| #3 | (#1 OR #2) | 30409 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor Escin explode all trees | 53 |

| #5 | aesculus* | 31 |

| #6 | escin* or aescin* or essaven* | 113 |

| #7 | rosskastani* | 16 |

| #8 | horse* near (chestnut or chest‐nut) | 54 |

| #9 | venosta* | 25 |

| #10 | (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9) | 171 |

| #11 | (#3 AND #10) | 37 |

Appendix 2. Search strategy for Amed and Phytobase

| Search strategy |

| horse chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum escin venostasin Rosskastanie [Rosskastanie is the German common name for Aesculus hippocastanum L.] |

Appendix 3. Search strategy for CENTRAL 2010

| #1 | MeSH descriptor Venous Insufficiency explode all trees | 303 |

| #2 | insuffic* or CVI or isch* | 26623 |

| #3 | (#1 OR #2) | 26646 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor Escin explode all trees | 52 |

| #5 | aesculus* | 30 |

| #6 | escin* or aescin* or essaven* | 101 |

| #7 | rosskastani* or roskastani* | 14 |

| #8 | horse* near chest* | 49 |

| #9 | venosta* | 23 |

| #10 | (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9) | 156 |

| #11 | (#3 AND #10) | 37 |

Appendix 4. Search strategy for CENTRAL 2008

| Number of records retrieved | |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Venous Insufficiency explode all trees | 271 |

| #2 (ven* or chron*) near insuffic* | 1366 |

| #3 (#1 OR #2) | 1382 |

| #4 MeSH descriptor Escin explode all trees | 50 |

| #5 aesculus* near hippocastan* | 16 |

| #6 escin* or aescin* or essaven* | 97 |

| #7 rosskastani* | 14 |

| #8 horse* near (chestnut or chest‐nut) near seed* | 29 |

| #9 venosta* | 23 |

| #10 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9) | 136 |

| #11 (#3 AND #10) | 37 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. HCSE versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement of leg pain (responder ratio) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Reduction of leg pain (100 mm VAS) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Reduction of oedema (100 mm VAS) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Improvement of oedema (responder ratio) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 improvement of pruritus (responder ratio) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Reduction of lower leg volume (ml) | 6 | 502 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 32.10 [13.49, 50.72] |

| 7 Reduction of circumference at ankle (mm) | 3 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 4.71 [1.13, 8.28] |

| 8 Reduction of circumference at calf (mm) | 3 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.51 [0.58, 6.45] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement of leg pain (responder ratio).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 3 Reduction of oedema (100 mm VAS).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 4 Improvement of oedema (responder ratio).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 5 improvement of pruritus (responder ratio).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HCSE versus placebo, Outcome 8 Reduction of circumference at calf (mm).

Comparison 2. HCSE versus compression.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Reduction of lower leg volume (ml) | 2 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐37.34 [‐104.07, 29.39] |

| 2 Improvement of symptom score (40 point scale) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HCSE versus compression, Outcome 1 Reduction of lower leg volume (ml).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HCSE versus compression, Outcome 2 Improvement of symptom score (40 point scale).

Comparison 3. HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Reduction of circumference at ankle (mm) | 2 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.38 [‐1.47, 6.23] |

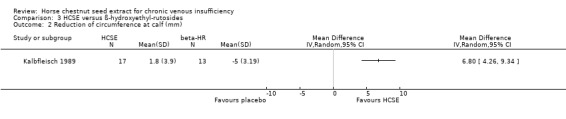

| 2 Reduction of circumference at calf (mm) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

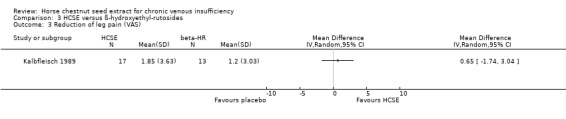

| 3 Reduction of leg pain (VAS) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Leg volume (ml) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

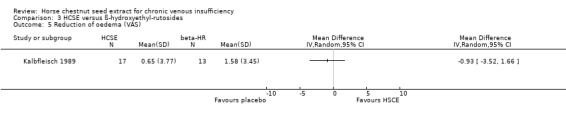

| 5 Reduction of oedema (VAS) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides, Outcome 1 Reduction of circumference at ankle (mm).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides, Outcome 2 Reduction of circumference at calf (mm).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides, Outcome 3 Reduction of leg pain (VAS).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides, Outcome 4 Leg volume (ml).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HCSE versus ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides, Outcome 5 Reduction of oedema (VAS).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cloarec 1992.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: none. Losses to follow up: none. Quality score = 3. |

|

| Participants | Country: France. Setting: hospital. No: 30 entered, 0 drop outs. Age: (mean) 45.5 and 47.7 years in HCSE and placebo group, respectively. Sex: males 15; females 15. Inclusion criteria: patients with functional symptoms due to CVI at least in one leg; patients with impression oedema at least in one leg. Exclusion criteria: systolic blood pressure ankle/arm > 0.9; acute or precedent (< 1 month) thrombophlebitis; leg ulcer of venous origin; cardiac, renal or orthopaedic oedema. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 4 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly stated).

Secondary: (not explicitly stated). 1) circumference (mm) 2) leg pain (mm) 3) oedema (mm) |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): 1) circumference a) ankle 0.57 (‐0.16 to 1.30) b) calf 0.26 (‐0.46 to 0.98) 2) 3.93 (2.65 to 5.22) 3) 3.28 (2.14 to 4.43) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "In a double blind study Venostasin versus placebo was studied in 30 cases ..." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed; intention to treat analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Diehm 1992.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blind. Method of randomisation: block randomisation. Exclusion post randomisation: one patient. Losses to follow up: none. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 40 entered, 1 excluded post randomisation. Age: (mean) 53 and 48 years in treatment and control groups, respectively. Sex: reported males 9; females 29. Inclusion criteria: CVI stage 2 according to Hach, venous flow impairment, oedema, possible trophic skin changes, venous capacity and / or venous return outside normal limits. Exclusion criteria: CVI liable to venous compression, acute venous inflammation, acute thrombosis, venous ulceration, oedema due to other conditions than CVI. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 75 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 6 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: leg volume (ml). Secondary: 1) circumference 2) pruritus |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: 0.30 (‐0.33 to 0.94) Secondary: 1), 2) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "The double blind nature of the trial as assured by using placebos which in terms of outer appearance and taste were identical to verum" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Diehm 1996a.

| Methods | Study design: 3 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blinded (for placebo and HCSE only). Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: none. Losses to follow up: not reported. Quality score = 2. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 240 entered, drop outs not reported. Age: (mean) 52 years. Sex: not reported. Inclusion criteria: oedema due to CVI (confirmed by medical history, clinical findings, venous Doppler and duplex sonography. Exclusion criteria: venotherapeutic drugs within the last 6 weeks before run‐in. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo or compression stockings. Duration: 12 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly stated) leg volume (ml). Secondary: (not explicitly stated) circumference, symptoms . |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: HCSE versus placebo 0.49 (0.14 to 0.85) HCSE versus compression ‐0.03 (‐0.31 to 0.25) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Patients were treated over a period of 12 weeks in a randomised partially blinded placebo controlled paralles study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Diehm 2000.

| Methods | Study design: 3 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: 69. Quality score = 2. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: unclear. No: 355 entered, drop outs 69. Age: not reported. Sex: not reported. Inclusion criteria: CVI stage II and IIIA. Exclusion criteria: venotherapeutic drugs within the last 6 weeks, patients with oedema of non‐venous origin. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo or compression stockings. Duration: 16 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: leg volume (ml). Secondary: symptom score computed from: 1) feeling of swelling 2) tiredness in the leg 3) itching 4) leg cramps 5) paraesthesia 6) plantar burning 7) unspecific complaints |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: HCSE versus placebo 0.26 (‐0.03 to 0.54) HCSE versus compression 0.70 (‐0.94 to 0.46) Secondary: HCSE versus compression 0.06 (‐0.17 to 0.29) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "The study was double‐blind regarding allocation to HCSE or placebo and open regarding allocation to the compression group" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Reported within a review article only |

Erdlen 1989.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised double‐blind. Method of randomisation: Central randomisation by company. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: not reported. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP setting. No: 30 entered, drop outs not reported. Age: (mean) 55 years in treatment group; no data for control. Sex: males 10; females 20. Inclusion criteria: varicosis due to CVI, peripheral venous oedema. Exclusion criteria: oedema due to other conditions than CVI, vasoactive medication, compression treatment, venous ulcers. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: rutoside. Duration: 4 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: circumference (mm). Secondary: not reported. |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: ankle 0.0 (‐0.72 to 0.72) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomisation was done. Random codes were kept in sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment and placebo capsules were indistinguishable in terms of outer appearance |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Erler 1991.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blind. Method of randomisation: block randomisation. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: not reported. Quality score = 3. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 40 entered, drop outs not reported. Age: (mean) 55.5 and 53.9 years in treatment and control group, respectively. Sex: males 10; females 20. Inclusion criteria: oedema due to CVI. Exclusion criteria: oedema due to other conditions than CVI, vasoactive medication, compression treatment, venous ulcers. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 75 mg escin) twice daily. Control: O‐beta‐hydroxyethyl rutosides (2 g daily). Duration: 8 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: circumference before and after oedema provocation. Secondary: (not explicitly defined) symptoms (leg pain, oedema, pruritus, fatigue). |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. Secondary: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Neutrally coated capsules which were indistinguishable in terms of outer appearance |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Friederich 1978.

| Methods | Study design: crossover, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: 23. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 118 entered, 23 drop outs. Age: (mean) 48 and 47 years in men and women, respectively. Sex: males 11; females 107. Inclusion criteria: oedema, leg pain, pruritus, feeling of tenseness and fatigue. Exclusion criteria: not reported. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 20 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly defined) symptoms

1) leg pain

2) oedema

3) pruritus Secondary: (not explicitly defined) patients' impression of effectiveness. |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: 1), 2), 3) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. Secondary: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment and placebo capsules were identical in terms of outer appearance |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Kalbfleisch 1989.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: none. Losses to follow up: three. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP practice. No: 33 entered, 3 drop outs. Age: "18 years and over". Sex: male and female (numbers not reported). Inclusion criteria: CVI and oedema. Exclusion criteria: cardiac and hepatic oedema, patients with kidney and liver dysfunctions, venous ulcers, vasoactive medication, NSAIDs, glucosides. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) once daily. Control: O‐beta‐hydroxyethyl rutosides (50 mg daily). Duration: 8 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly stated)

circumference (mm). Secondary: (not explicitly stated) 1) leg pain (mm) 2) oedema (mm) 3) pruritus |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: a) ankle 2.13 (1.20 to 3.06) b) calf 1.83 (0.95 to 2.21) Secondary: 1) 0.19 (‐0.54 to 0.91) 2) ‐0.25 (‐0.97 to 0.48) 3) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment and placebo capsules were neutrally coated |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Koch 2002.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised, open. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: one. Losses to follow up: not reported. Quality score = 1. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP practice. No: 40 entered, drop outs not reported. Age: (mean) 56 and 59 years in HCSE and pycnogenol group respectively. Sex: males 7; females 33. Inclusion criteria: CVI. Exclusion criteria: not reported. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin twice daily). Control: pycnogenol (360 mg daily). Duration: 4 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly defined)

1) Symptoms

a) leg pain

b) oedema

c) cramps

d) feeling of heaviness

e) leg reddening 2) Circumference (mm). Secondary: (not explicitly defined) Serum cholesterol. |

|

| Notes | 1), 2) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | "In an open controlled comparative study 40 patients with diagnosed CVI were treated." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is not clear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Lohr 1986.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised, double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: 6. Quality score = 3. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP practice. No: 80 entered, 6 drop outs. Age: (mean) 54 years in total patient sample. Sex: males 17; females 57. Inclusion criteria: CVI. Exclusion criteria: not reported. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 8 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary:

leg volume Secondary: 1) circumference 2) leg pain 3) oedema 4) pruritus |

|

| Notes | Primary and secondary outcomes: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The study was conducted randomised and double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is not clear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Morales 1993.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: three. Quality score = 3. |

|

| Participants | Country: Brazil. Setting: hospital. No: 54 entered, 3 drop outs. Age: (mean) 40 years in total patient sample. Sex: males 2; females 52. Inclusion criteria: oedema, varicosis, venous ulcers. Exclusion criteria: diabetes mellitus, oedema of other origin, peripheral arterial disease, diuretic medication. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 20 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly defined)

oedema Secondary: (not explicitly defined) 1) leg pain 2) pruritus |

|

| Notes | Primary and secondary outcomes: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "This is a double blind randomised placebo controlled parallel study of the ise of dried horse chestnut extract (Venostasin retard) in chronic venous insufficiency of the limbs:" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No evidence for selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of further biases |

Neiss 1976.

| Methods | Study design: crossover, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: seven. Quality score = 3. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP practice. No: 233 entered, 7 drop outs. Age: (mean) 56 and 55 in women and men, respectively. Sex: males 29; females 197. Inclusion criteria: CVI with symptoms including oedema, leg pain, pruritus fatigue and tenseness, calf cramps. Exclusion criteria: concomitant medication or physical treatments. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 20 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly defined) symptoms

1) leg pain

2) oedema

3) pruritus

4) feeling of fatigue and tenseness

5) calf cramps Secondary: not described. |

|

| Notes | 1), 2), 3), 4), 5) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "...the study was carried out in a double‐blind design." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Pilz 1990.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: block randomisation. Exclusion post randomisation: two. Losses to follow up: none. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: GP practice. No: 30 entered, 2 drop outs. Age: (mean) 46 in total patient sample. Sex: males 6; females 24. Inclusion criteria: Symptoms of CVI with peripheral leg oedema. Exclusion criteria: patients under 20 and over 70 years of age, less than 2 symptoms of CVI, leg ulcers, oedema or leg pain of other origin than CVI, rheumatic diseases, concomitant medication, compression treatment. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 20 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly stated). Secondary: (not explicitly stated). |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: circumference (mm). a) ankle 0.70 (‐0.04 to 1.45) b) calf 0.86 (0.11 to 1.61) Secondary: (not explicitly stated) adverse events. none. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomisation and allocation of patients to treatment and control groups was performed centrally by Klinge Pharma. The random code was stored in sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Verum and placebo were indistinguishable in terms of outer appearance and taste |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Rehn 1996.

| Methods | Study design: 3 parallel arms, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: 21. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: not reported. No: 158 entered, 21 drop outs. Age: mean 58.4 years ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides (1 g daily) group; 62.8 years ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides (1 to 0.5 g daily) group; 59.0 years HCSE group. Sex: all females. Inclusion criteria: uni‐ or bilateral CVI stage II, doppler sonographic assessment within the past 6 months. Exclusion criteria: oedema due to other conditions than CVI, over 70 years of age, current acute phlebitis or thrombosis, concomitant medication, compression treatment. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides (1 g daily) or ß‐hydroxyethyl‐rutosides (1 to 0.5 g daily). Duration: 12 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: leg volume (ml). Secondary: Symptoms: tired, heavy legs (VAS (mm)). |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: HR (1g): ‐0.17 (‐0.56 to 0.22) HR (1 to 0.5g): 0.05 (‐0.38 to 0.48) Secondary: (mean, SD) 4.1, 2.9; 3.8, 2.6; 3.0, 2.2 at baseline for beta‐HR 1 g, beta‐HR 1 to 0.5 g and HCSE respectively. ‐1.5, 3.0; ‐1.0, 3.3; ‐0.2, 2.5 are the respective changes from baseline (no formal statistical analysis). |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "According to the double dummy procedure both for oxerutin film tablets and horse chestnut extract capsules identically appearing placebo tablets or capsules were used." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Missing data were interpolated if possible or the method of last value carry forward was used." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases |

Rudofsky 1986.

| Methods | Study design: 2 parallel arms, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: random number generator. Exclusion post randomisation: none. Losses to follow up: 1. Quality score = 5. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 40 entered, 1 drop out. Age: (mean) 41 and 38 years in treatment and placebo groups, respectively. Sex: males 14, females 25. Inclusion criteria: clinical signs of CVI (e.g. varicosis, hyperpigmentation), symptoms (e.g. leg pain, pruritus), venous capacity of over 6 ml per 100 ml tissue, venous pressure (dorsum pedis) of at least 60 mmHg. Exclusion criteria: CVI stage III, acute phlebitis, oedema of other origin than CVI, concomitant medication (e.g. diuretics, vasoactive drugs). |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 4 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: (not explicitly stated)

leg volume (ml) Secondary: (not explicitly stated) 1) circumference 2) leg pain 3) pruritus |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: 0.46 (‐0.18 to 1.10) Secondary: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Verum and placebo capsules were indistinguishable .... Thus it was impossible for physician and patient to determine whether they received the true or placebo medication |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | There is no evidence of other biases |

Steiner 1986.

| Methods | Study design: crossover, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: none. Losses to follow up: none. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 20 entered, drop outs none. Age: (range) 20 to 40 years in total patient sample. Sex: all females. Inclusion criteria: CVI stage I, peripheral venous oedema. Exclusion criteria: Patients in third trimenon, CVI stages II and III, diuretics, vasoactive medication. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 2 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary:

leg volume (ml) Secondary: 1) circumference (mm) 2) symptoms (e.g. pruritus). |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: 0.41 (‐0.48 to 1.30) Secondary: 1) a) ankle 0.48 (‐0.41 to 1.38) b) calf 0.07 (‐0.81 to 0.95) 2) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The random code was kept in sealed envelopes (information from duplicate publication Steiner 1990b) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Verum and placebo capsules were indistinguishable in terms of colour and taste (information from duplicate publication Steiner 1990b) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other bias |

Steiner 1990a.

| Methods | Study design: crossover, randomised,

double‐blind. Method of randomisation: not reported. Exclusion post randomisation: not reported. Losses to follow up: two. Quality score = 4. |

|

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: hospital. No: 52 entered, 2 drop outs. Age: (mean) not reported. Sex: all females. Inclusion criteria: over 18 years of age, varicose veins and clinically detectable oedema, CVI had to be confirmed by at least two of either Doppler sonography, plethysmography venous pressure measurements or light reflection rheography. Exclusion criteria: not described. |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 capsule HCSE (standardised to 50 mg escin) twice daily. Control: placebo. Duration: 2 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary:

1) leg volume (ml)

2) circumference (mm) Secondary: symptoms: leg pain, pruritus, oedema, fatigue. |

|

| Notes | Standardised mean difference (95% CI): Primary: 1) 0.15 (‐0.40 to 0.71) 2) Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. Secondary: Not enough data provided for effect size calculation. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Patients were given either one capsule of Venostasin retard twice daily or an identical placebo" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear how incomplete outcome data were addressed. Drop outs are described: "Of the 52 patients who were entered two patients discontinued the study; one had to undergo an operation and the other was lost to follow‐up" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | There is no evidence of other biases |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bisler 1986 | Used non‐clinical outcome measures. |

| Boehm 1989 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Coninx 1974 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Dols 1987 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Dustmann 1984 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Hirsch 1982 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Krc¡lek 1973 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Lochs 1974 | Trial performed on healthy volunteers, not people with CVI. |

| Marhic 1986 | Used cream, not oral preparation. |

| Neumann‐Mangoldt | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

| Nill 1970 | Used non‐clinical outcome measures. |

| Paciaroni 1982 | Used cream, not oral preparation. |

| Pauschinger 1987 | Used non‐clinical outcome measures. |

| Zuccarelli 1986 | HCSE applied as part of a combination preparation. |

Contributions of authors

Conception and design: MH Pittler, E Ernst Analysis and interpretation of the data: MH Pittler, E Ernst Drafting of the article: MH Pittler, E Ernst Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: MH Pittler, E Ernst Final approval of the article: MH Pittler, E Ernst

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates, The Scottish Government, UK.

The PVD Group editorial base is supported by the Chief Scientist Office.

Declarations of interest

None known

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Cloarec 1992 {published and unpublished data}

- Cloarec, M. Study on the effect of a new vasoprotective Venostasin administered over a period of 2 months in chronic venous insufficiency of the lower limb (data from 1992). Data on file.

Diehm 1992 {published data only}

- Diehm C, Vollbrecht D, Amendt K, Comberg HU. Medical edema protection ‐ Clinical benefit in patients with chronic deep vein incompetence. VASA 1992;21(2):188‐92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diehm 1996a {published data only}

- Diehm C, Trampisch HJ, Lange S, Schmidt C. Comparison of leg compression stocking and oral horse‐chestnut seed extract therapy in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Lancet 1996;347(8997):292‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diehm 2000 {unpublished data only}

- Diehm C, Schmidt C. Venostasin retard gegen Plazebo und Kompression bei Patienten mit CVI II/IIIA. Final Study Report. Klinge Pharma GmbH Munich, Germany. Reported in: Ottillinger B et al. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2001;1:5.

Erdlen 1989 {published data only}

- Erdlen F. Clinical efficacy of Venostasin: A double blind trial [Klinische Wirksamkeit von Venostasin retard im Doppelblindversuch]. Medizinische Welt 1989;40(36):994‐6. [Google Scholar]

Erler 1991 {published data only}

- Erler M. Horse chestnut seed extract in the therapy of peripheral venous edema ‐ clinical therapies in comparison [Roßkastaniensamenextrakt bei der Therapie peripherer venöser Ödeme ‐ ein klinischer Therapievergleich]. Medizinische Welt 1991;42(7):593‐6. [Google Scholar]

Friederich 1978 {published data only}

- Friederich HC, Vogelsberg H, Neiss A. Evaluation of internally effective venous drugs [Ein Beitrag zur Bewertung von intern wirksamen Venenpharmaka]. Zeitschrift fur Hautkrankheiten 1978;53(11):369‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kalbfleisch 1989 {published data only}

- Kalbfleisch W, Pfalzgraf H. Ödemprotektiva. Äquipotente Dosierung ‐ Roßkastaniensamenextrakt und O‐ß‐Hydroxyethylrutoside im Vergleich. Therapiewoche 1989;39:3703‐7. [Google Scholar]

Koch 2002 {published data only}

- Koch R. Comparative study of venostasin and pycnogenol in chronic venous insufficiency. Phytotherapy Research 2002;16(Suppl 1):S1‐S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lohr 1986 {published data only}

- Lohr E, Garanin G, Jesau P, Fischer H. Anti‐oedemic treatment in chronic venous insufficiency with tendency to formation of oedema [Ödempräventive Therapie bei chronischer Veneninsuffizienz mit Ödemneigung]. Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1986;128(34):579‐81. [Google Scholar]

Morales 1993 {published data only}

- Morales Paris CA, Barros Soares RM. Efficacy and safety on use of dried horse chestnut extract in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency of the limbs. Revista Brasileira de Medicina 1993;50(11):1563‐5. [Google Scholar]

Neiss 1976 {published data only}

- Neiss A, Böhm C. Demonstration of the effectiveness of horse chestnut seed extract in the varicose syndrome complex [Zum Wirksamkeitsnachweis von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt beim varikösen Symptomenkomplex]. Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1976;118(7):213‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pilz 1990 {published data only}

- Pilz E. Oedemas in venous disease [Ödeme bei Venenerkrankungen]. Medizinische Welt 1990;41(12):1143‐4. [Google Scholar]

Rehn 1996 {published data only}

- Rehn D, Unkauf M, Klein P, Jost V, Lücker PW. Comparative clinical efficacy and tolerability of oxerutins and horse chestnut extract in patients with chronic venous insufficiency [Vergleich der klinischen wirksamkeit und vertraglichkeit von oxerutin und Rosskastanien‐extrakt bei patienten mit chronischer venoser Insuffizienz]. Arzneimittel‐Forschung 1996;46(5):483‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rudofsky 1986 {published data only}

- Rudofsky G, Neiss A, Otto K, Seibel K. Oedema‐protective effect and clinical efficacy of horse chestnut seed extract in a double blind study [Ödemprotektive Wirkung und klinische Wirksamkeit von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt im Doppeltblindversuch]. Phlebologie und Proktologie 1986;15(2):47‐54. [Google Scholar]

Steiner 1986 {published data only}

- Steiner M. Evaluation of the oedema protective effect of horse chestnut seed extract [Ausmaß der ödemprotektiven Wirkung von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt]. Vasa 1991;20(Supplement 33):S217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner M. Investigation into the oedema reducing and oedema protective effects of horse chestnut seed extract [Untersuchungen zur ödemvermindernden und ödemprotektiven Wirkung von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt]. Phlebologie und Proktologie 1990;19(5):239‐42. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner M, Hillemanns HG. Tests for anti‐oedema action of a venous therapy [Untersuchung zur oedemprotektiven Wirkung eines Venentherapeutikums]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1986;128(31):551‐2. [Google Scholar]

Steiner 1990a {published data only}

- Steiner M, Hillemanns HG. Venostasin retard in the management of venous problems during pregnancy. Phlebology 1990;5(1):41‐4. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bisler 1986 {published data only}

- Bisler H, Pfeifer R, Klüken N, Pauschinger P. Effect of horse chestnut seed extract on transcapillary filtration in chronic venous insufficiency [Wirkung von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt auf die transkapilläre Filtration bei chronisch venöser Insuffizienz]. Deutschs Medizinische Wochenschrift 1986;111(35):1321‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boehm 1989 {published data only}

- Bohm, C. Venodiuretics: a new combination and oedema protective drug [Venodiuretikum ‐ Kombination eines Diuretikums mit einem Oedemprotektivum]. Medizinische Welt 1989;40(30‐31):887‐8. [Google Scholar]

Coninx 1974 {published data only}

- Coninx S. Supplementary drug therapy in the treatment of venous insufficiency. Results of a double blind study [Medikamentoese Zusatztherapie bei der Behandlung der venoesen Insuffizienz]. Fortschritte der Medizin 1974;92(18):792‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dols 1987 {published data only}

- Dols W, Fiala G. Treatment of varicosis in patients with chronic venous insufficiency and peripheral oedema [Therapie der Varikosis bei chronischer Varikosis und peripheren Oedemen]. Therapiewoche 1987;37(38):3601‐4. [Google Scholar]

Dustmann 1984 {published data only}

- Dustmann HO, Godolias G, Seibel K. Foot volume with chronic venous insufficiency while standing; effect of a new treatment [Verminderung des Fußvolumens bei der chronischen venösen Insuffizienz im Stehversuch durch eine neue Wirkstoffkombination]. Therapiewoche 1984;34(36):5077‐86. [Google Scholar]

Hirsch 1982 {published data only}

- Hirsch J. The effect of Essaven ultra in chronic venous insufficiency. Fortschritte der Medizin 1982;100(10):436‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krc¡lek 1973 {published data only}

- Krc¡lek A, Smejkal V. [Therapeutic effects of venotonics in clinical pharmacotherapeutical evaluations by double‐blind tests]. Casopis Lekaru Ceskych 1973;112:930‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lochs 1974 {published data only}

- Lochs H, Baumgartner H, Konzett H. Effect of horse chestnut seed extract on venous tone [Zur Beeinflussung des Venetonus durch Rosskastanienextrakte]. Arzneimittel‐Forschung 1974;24(9):1347‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marhic 1986 {published data only}

- Marhic C, Anglade JP. [Analgesic effect of rap cream on venous insufficiency pain syndrome of the lower limbs]. Phlebologie 1986;39(4):1011‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neumann‐Mangoldt {published data only}

- Neumann‐Mangoldt P. Experiences in the use of Essaven capsules in the treatment of venous leg diseases. Results of a double blind study [Erfahrungen in der Behandlung venoeser Beinleiden mit Essaven‐Kapseln]. Fortschritte der Medizin 1979;97(45):2117‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nill 1970 {published data only}

- Nill HJ, Fischer H, Nill HJ, Fischer H. [Comparative investigations concerning the effect of extract of horse chestnut upon the pressure‐volume‐diagramm of patients with venous disorders]. [German]. Arztliche Forschung 1970;24(5):141‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paciaroni 1982 {published data only}

- Paciaroni E, Marini M. Topical therapy for phlebopathies. Results of a controlled clinical study. Policlinico ‐ Sezione Medica 1982;89(3):255‐64. [Google Scholar]

Pauschinger 1987 {published data only}

- Pauschinger P. Clinical investigation into the effects of horse chestnut seed extract on transcapillary filtration and intravenous volume in patients with chronic venous insufficiency [Klinisch experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Wirkung von Roßkastaniensamenextrakt auf die transkapilläre Filtration und das intravasale Volumen an Patienten mit chronisch venöser Insuffizienz]. Phlebologie und Proktologie 1987;16:57‐61. [Google Scholar]

Zuccarelli 1986 {published data only}

- Zuccarelli F. Study of the clinical efficacy of escin plus metescufylline in painful manifestations of chronic venous insufficiency [Etude de l'efficacite clinique du Veinotonyl sur les manifestations douloureuses de l'insuffisance veineuse chronique]. Gazette Medicale 1986;93(42):67‐70. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bombardelli 1996

- Bombardelli E, Morazzoni P, Griffini A. Aesculus hippocastanum L. Fitoterapia 1996;67(6):483‐511. [Google Scholar]

Callam 1992

- Callam M. Prevalence of chronic leg ulceration and severe chronic venous disease in western countries. Phlebology 1992;7(Suppl 1):6‐12. [Google Scholar]

Callam 1994

- Callam MJ. Epidemiology of varicose veins. British Journal of Surgery 1994;81(2):167‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diehm 1996b

- Diehm C. The role of oedema protective drugs in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency: a review of evidence based on placebo‐controlled trials with regard to efficacy and tolerance. Phlebology 1996;11(1):23‐9. [Google Scholar]

Easterbrook 1991

- Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337(8746):867‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Zellweger‐Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997;350(9074):326‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1998