After 2014, U.S. life expectancy fell for three straight years.1 While this trend has stabilized in the most recent data,2 this is a very disturbing finding, not associated with other wealthy countries in the world. Decreased life expectancy is most pronounced among males in the United States.1 Declining life expectancy in the U.S. has been widely covered by newspapers around the globe and given rise to a cottage industry of speculation on causes, with varied social, cultural, and political actors making use of the findings for preferred narratives. Some of this speculation arose after Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton coined the term “deaths of despair,”3 an easily misunderstood term. Case and Deaton used the term to refer to fatal drug overdoses, alcohol-related diseases, and suicides. “We think of all these deaths as suicides, by a very broad definition,” these economists have written,3 “and we attribute them to a broad deterioration in the lives of Americans without a college degree who entered adulthood after 1970.”

In late 2019, a National Institute on Aging-supported review offered a comprehensive examination of falling U.S. life expectancy. This study4 used data from the CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, and U.S. Mortality Database to trace life expectancy trends over a longer time frame and analyze mortality rates for particular age cohorts. It paints a complicated picture of poor U.S. mortality trends, which are not driven just by our polysubstance epidemics, and a decidedly unhappy one. The authors write, “According to one estimate, if the slow rate of increase in U.S. life expectancy persists, it will take the United States more than a century to reach the average life expectancy that other high-income countries had achieved by 2016.”4

Results of Study on U.S. Life Expectancy

This study found that U.S. life expectancy, between 1959 and 2016, rose to 78.9 years from 69.9 years. But, following 2014, life expectancy began declining. “A major contributor,” this study’s authors write, “has been an increase in mortality from specific causes (e.g., drug overdoses, suicides, organ system diseases) among young and middle-aged adults of all racial groups, with an onset as early as the 1990s and with the largest relative increases occurring in the Ohio Valley and New England.”

This study also finds that:

Mortality increases are concentrated among Americans at “midlife”, or those between 25–64 years of age. The all-cause mortality rate rose by six percent between 2010–2017 for Americans between these ages.

Rising mortality between 2010–2017 led to 33,307 excess deaths.

More than 32 percent of these deaths happened in Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, and West Virginia—or the Ohio Valley states. The upper New England states also had some of the largest mortality increases, though they account for a lower share of the overall total.

These rising mortality figures are found among all racial groups in the U.S.

These trends do not significantly reflect changes in violent crime or gun violence. The U.S. is much less violent than it used to be, and although it still has higher violent crime rates than other rich countries, things have gotten much better in the last 30 years. Other medical conditions, such as infectious diseases and cancers, were also not behind these changes, as outcomes for certain medical problems actually improved.

These researchers offer some answers. They first examine life expectancy from 1959 to trace when it started to change and, recognizing that fatal overdoses started to rise in the nineties, next look at cause-specific mortality between 1997–2017. They note that U.S. life expectancy first diverged from other wealthy countries in the ‘80s. Our rate of increase in life expectancy was not as fast as in other wealthy countries. In the ‘90s, cause-specific mortality rose for Americans in midlife. By 1998, the U.S. fell below the life expectancy average of other rich countries. Then U.S. life expectancy increases ended in 2010 and started falling in 2014. Fatal overdoses account for an important share of this increase — they rose by almost 387% between 1999–2017. Deaths from alcoholic liver disease rose by around 41 percent, and suicides by around 38 percent. But other causes were, or still are, at play, too. Hypertensive disease rates, for example, also rose — by about 79 percent. And obesity death rates were higher, rising by 114 percent. The authors observe that one study found that, for women, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions accounted for nearly as many deaths as fatal overdoses.

What’s Going On?

It’s a tough question. The authors write, “The largest relative increases in midlife mortality occurred among adults with less education and in rural areas or other settings with evidence of economic distress or diminished social capital.” But these observations aren’t necessarily explanatory factors in our life expectancy decline. This review considers different explanations and evidence in their favor. Isn’t it really just our drug epidemics — the rising death toll from heroin in the ‘60s and ‘70s, cocaine in the ‘80s and then the three-stage opioid epidemic of prescriptions, heroin, and synthetics? Well, the authors say, this is a significant part of the story, but far from complete. Suicides and alcohol-related liver diseases have also contributed substantially and the timing is off because our life expectancy divergence started in the eighties, “and involved multiple diseases and nondrug injuries.” They also point to two studies suggesting that only 15 percent of our life expectancy divergence can be explained by fatal overdoses. Washington University experts including Professor Ted Cicero were the first to alert us that the prescription opioid epidemic had morphed into an injection and heroin epidemic.5 Sadly, things have only gotten worse with fentanyl being added to illicit heroin and now multiple fentanyl added to street drugs and the emergence of primary fentanyl use.6

What about smoking? Americans smoke less than we used to, but smoking more decades ago could still kill more people today. And, Americans are often more obese than their peer country counterparts, so could that account for the differences? This review points to research on other countries, like Australia, that resemble the U.S. in smoking and obesity but haven’t followed our marked life expectancy divergence. Health care? The U.S. famously spends more to cover fewer people than its peers, and Americans also face higher costs of care, but the authors note that this wouldn’t account for why we have more deaths from some diseases and not others, and from suicides or obesity-related deaths “which originate outside the clinic.” Might the problem be “deaths of despair” after all, then, or a large increase in psychological distress? There’s “inconclusive evidence” that depression and anxiety, which can also harm physical health, rose over the relevant time period, and, the authors say, it’s also hard to figure out the link between conditions like depression and all the rising specific causes of death. But it is difficult to not conclude that overdose deaths, suicides, and accidents are not related. The Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and our own work7 has supported this with data showing that many opioid overdoses are passive suicide attempts and others are death by opioids.

This review continues like this, carefully weighing the relative evidence about which factors make sense and under which conditions. For socioeconomic status, the authors say that the timing works, because the U.S. experienced pronounced economic churn in the ‘80s and ‘90s, with the most economically impacted areas and people also experiencing the largest mortality rises. But then localized data on income and employment don’t always align with the geographic and demographic trackers. What’s the answer? It’s likely that there isn’t a particular cause, or at least one we can decisively identify right now. The authors say these various possible causes “are not independent and collectively shape mortality patterns.” They call for the accumulation of more rigorous evidence, gathered from machine learning, migration research, and cohort studies, and interdisciplinary research, given how many different areas may contribute, and attempts to answer comparative questions about why some states and regions have worse life expectancy than others, and why other rich countries do better. These are sensibly modest conclusions but gravely important — they affect our view of the most important challenge we face.

This review does not consist of entirely dreary findings. Life expectancy has risen in some U.S. states, deaths from some causes, like violence, have declined, and black men’s life expectancy has improved. Deaths from screenable prostate, breast, cervical, and colon cancer are down, as are cardiovascular diseases. Reports8 say that the cancer death rate has dropped 29 percent, leading to about three million fewer deaths relative to a steady mortality rate. But supporting data has been stubbornly consistent. University of Pennsylvania researchers have found that outside of metropolitan areas following 1990, mortality increased even though it declined for many other demographic groups.9 Overdoses and overdose deaths are projected by the Stanford artificial intelligence group to continue at this pace as opioid use disorders relapse and risk of overdose does not appear to diminish in these patients even after long term medication assisted therapy.10

Many death certificates show a different story. Looking at death certificates from 2017 nearly 75,000 people died in the U.S. in 2017 from liver disease and alcohol-related conditions, a steep rise from 1999, when 36,000 died from those causes. Women used to die at lower rates from these conditions, but that gap has closed.11 As reported first by Case and Deaton and reiterated in their upcoming book,12 rising morbidity and mortality among whites due to accidents, drug overdoses, alcoholism, liver disease, and suicides means reduced overall longevity. These deaths are alarming businesses, too, as there are more suicides in the workplace than in the past.13 I expect that suicides, as well as overdose deaths, are undercounted.14 This should not be surprising as suicide is generally more stigmatized than accidental overdose. The most recent Florida data suggests that 1 out of 3 opioid overdose deaths, and an even greater share of cocaine deaths, are not reported.15 So, deaths of despair, may be occurring more frequently than we have thought.

Recent anecdotal data suggests from suicide hotlines and suicide text services have increased dramatically as COVID-19 has spread. Anxiety, by itself, can increase relapses in treated psychiatric illnesses including depression and also substance use disorders. Substance and Opioid Use Disorder relapses are often fatal. New SUDs can develop among people who had not had one beforehand. New drug use and users, can have more accidents and overdoses. Alcohol use may increase and the association between alcohol, depression, and suicide is direct. Chinese citizens16 surveyed in February found that 42.6% of respondents experienced anxiety related to the coronavirus outbreak. Social distancing can cause loneliness and depression. Quarantine or extreme isolation can trigger PTSD as we found after the SARS outbreak.

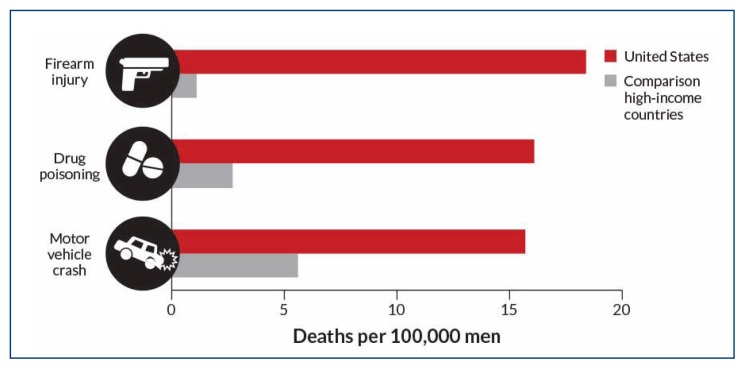

Figure 1.

Three Causes of Death Among Men

Footnotes

Mark S. Gold, MD, is Adjunct Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University and an internationally recognized and expert in addiction medicine.

Contact: msgold@ufl.edu

References

- 1.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31769830

- 2.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm

- 3.https://www.princeton.edu/~accase/downloads/Case_and_Deaton_Comment_on_CJRuhm_Jan_2018.pdf

- 4.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31769830 several citations used in parentheses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc1505541

- 6.https://www.addictionpolicy.org/blog/tag/research-you-can-use/fentanyl-crisis-getting-worse

- 7.https://www.addictionpolicy.org/blog/tag/research-you-can-use/opioids-and-suicide

- 8.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/08/health/cancer-deaths-decline.html

- 9.Elo IT, Hendi AS, Ho JY, Vierboom YC, Preston SH. Trends in non-Hispanic white mortality in the United States by metropolitan-nonmetropolitan status and region, 1990–2016. Pop Dev Rev. 45(3):549–583. doi: 10.1111/padr.12249. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31588154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/news/opioid-overdose-risk-high-after-medical-treatment-ends-study-finds

- 11.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol-related deaths increasing in the United States [news release] 2020. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/alcohol-related-deaths-increasing-united-states.

- 12.Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2018 [news release] 2019. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf.

- 13.https://www.amazon.com/Deaths-Despair-Future-Capitalism-Anne-ebook/dp/B082YJRH8D/ref=dp_kinw_strp_1

- 14.https://www.addictionpolicy.org/blog/tag/research-you-can-use/opioids-and-suicide

- 15.https://www.usf.edu/news/2020/federal-data-undercounts-fatal-overdose-deaths.aspx

- 16.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-mental/chinese-public-dial-in-for-support-as-coronavirus-takes-mental-toll-idUSKBN2070H2