Abstract

Background

Treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) in dialysis patients has been shown to be highly effective in terms of correcting anaemia and improving quality of life. There is debate concerning the benefits of rHuEPO use in predialysis patients which may accelerate the deterioration of kidney function. However the opposing view is that if rHuEPO is as effective in predialysis patients, improving the patient's sense of well‐being may result in the onset of dialysis being delayed. This is an update of a review first published in 2001 and last updated in 2005.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to ascertain the effects of rHuEPO treatment in predialysis patients primarily in terms of the timing of the onset of dialysis; but also that predialysis rHuEPO: 1) corrects haemoglobin/haematocrit (markers of anaemia); 2) improves quality of life; and 3) is not associated with an increased incidence of adverse events such as hastening of the onset of dialysis, increased hypertension, clotting of arterio‐venous fistulae or seizures.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register (up to 29 June 2015) through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs comparing the use of rHuEPO with no treatment or placebo in predialysis patients.

Data collection and analysis

Only published data were used. Quality assessment was performed by two assessors independently. Data were abstracted by a single author onto a standard form, a sample of which was checked by another author. Results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) or mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Nineteen studies (enrolling 993 participants) were included. Due to the age of the included studies (most performed prior to 2000) the risk of bias was judged to be unclear in the majority of the studies for most of the domains. There was an improvement in haemoglobin (MD 1.90 gm/L, 95% CI ‐2.34 to ‐1.47) and haematocrit (MD 9.85%, 95% CI 8.35 to 11.34) with treatment and a decrease in the number of patients requiring blood transfusions (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.83). The data from studies reporting quality of life or exercise capacity demonstrated an improvement in the treatment group. Most of the measures of progression of kidney disease showed no statistically significant difference. No significant increase in adverse events was identified.

Authors' conclusions

Treatment with rHuEPO in predialysis patients corrects anaemia, avoids the requirement for blood transfusions and also improves quality of life and exercise capacity. We were unable to assess the effects of rHuEPO on progression of kidney disease, delay in the onset of dialysis or adverse events. Based on the current evidence, decisions on the putative benefits in terms of quality of life are worth the extra costs of predialysis rHuEPO need careful evaluation.

Plain language summary

Erythropoietin helps people with kidney failure and symptoms from anaemia who are not yet on dialysis

Anaemia (low red blood cells) is a common complication of kidney failure. Anaemia causes some of the tiredness and problems associated with kidney failure. Manufactured erythropoietin (a hormone that increases red blood cell production) improves this, and is used by people on dialysis (treatment from an artificial kidney machine). This review found it can also reduce anaemia for people with kidney failure who are not yet on dialysis. It is not known if erythropoietin use can delay the need for dialysis.

Background

Anaemia is often an associated condition in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). There is a direct relationship between the severity of the anaemia and the decline in kidney function (Koch 1991). This anaemia is a source of significant morbidity causing symptoms such as lack of energy, breathlessness, dizziness, angina, poor appetite and decreased exercise tolerance (Canadian EPO Study Group 1990; Lundin 1989). The main cause of this anaemia is a decreased production of erythropoietin, a naturally occurring hormone mainly produced by the kidney (Jensen 1994). Much of the impaired quality of life and morbidity suffered by patients with CKD may be a consequence of this anaemia and it may have a major impact on their sense of well‐being as well as impairing their ability to work and affecting their social and sexual lives. In the past, iron and folate were the main treatments for this condition and blood transfusions, with their associated risks of transmission of infection and induction of cytotoxic antibodies, which could jeopardise a future kidney transplant (Ward 1990), were used sparingly. In 1983 the cloning of the human gene for erythropoietin was achieved (Lin 1985), production of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) followed and by 1986 the efficacy of rHuEPO treatment in dialysis patients was first demonstrated (Winearls 1986).

Although treatment with rHuEPO in dialysis patients has been shown to be highly effective in terms of correcting anaemia and improving quality of life (Canadian EPO Study Group 1990), there is debate concerning the benefits of rHuEPO use in predialysis patients (patients with CKD anticipated to start renal replacement therapy (RRT) in the near future). Nonetheless there is increasing use of erythropoietin in predialysis patients and professional guidelines are increasingly recommending its use. Anaemia may be a cause of significant morbidity in such patients and substantial numbers of the predialysis population may benefit from treatment with rHuEPO. Its use may enable patients to carry on working longer and, importantly, by improving the patients' sense of well‐being could delay the onset of dialysis. In a survey of 20 investigators in rHuEPO clinical trials and 250 randomly selected nephrologists it was estimated that by improving symptoms of anaemia, rHuEPO therapy could delay the initiation of dialysis for an average of 3.7 months (Sheingold 1990). This could have important cost implications which need to be taken into account in an economic evaluation should such a delay exist. The converse opinion, based on results from animal studies, is that rHuEPO may cause or worsen hypertension (Garcia 1985) and potentially cause an accelerated deterioration in kidney function hence bringing forward initiation of dialysis. Based on work with partially nephrectomised rats, Garcia 1985 suggested that anaemia may have a protective effect on the development of progressive kidney failure and could be an adaptive mechanism. One small clinical study suggested a similar detrimental effect of rHuEPO on kidney function (Muirhead 1994). Other adverse effects which have also been attributed to the use of rHuEPO are clotting of the arterio‐venous fistula which provides access to the circulation for haemodialysis, elevation of blood pressure and seizures (Koch 1991).

The debate about the effectiveness of treating predialysis patients with rHuEPO combined with the perceived increased cost of using this expensive drug may have led to a reluctance to use rHuEPO in this group of patients.

This review aimed to determine the effects of treating the anaemia of CKD with rHuEPO in predialysis patients. Studies evaluating newer erythropoietic stimulating agents (darbepoetin, CERA) have not been included as they are the subject of other reviews (Palmer 2012; Palmer 2014).

Objectives

The objective of this review was to ascertain the effects of rHuEPO treatment in predialysis patients primarily in terms of the timing of the onset of dialysis; but also that predialysis rHuEPO:

corrects haemoglobin/haematocrit (markers of anaemia);

improves quality of life;

is not associated with an increased incidence of adverse events such as hastening of the onset of dialysis, increased hypertension, clotting of arterio‐venous fistulae or seizures.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCT) or quasi‐RCTs (in which concealment of allocation of patients to treatment groups is less secure e.g. alternation where patients are consecutively allocated to different treatments) comparing rHuEPO treatment (experimental group) with either placebo or no rHuEPO (control group) in predialysis patients with renal anaemia were included in this review.

Types of participants

Patients with the anaemia of CKD who have not yet commenced dialysis were included. The definitions of anaemia and CKD used by each individual study were accepted. There were no age exclusions.

Types of interventions

Treatment with rHuEPO irrespective of dose or mode of delivery versus placebo or no rHuEPO were included.

Types of outcome measures

Measures of progression of kidney failure: time from start of rHuEPO to start of dialysis; numbers starting RRT in each group; glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at the end of the study; change in GFR; serum creatinine at the end of the study and change in creatinine in each group. Accepted methods for measurement of GFR were inulin clearance, any isotopic measure and formula based estimated GFR (e.g. MDRD and Cockcroft Gault).

Measures of correction of anaemia: haemoglobin/haematocrit values; numbers of blood transfusions.

Quality of life measures, including changes in exercise capacity.

Measures of hypertension: systolic blood pressure; diastolic blood pressure; numbers with an increase or introduction of antihypertensive treatment.

Other adverse events: numbers discontinued due to adverse events; access problems for patients commenced on haemodialysis; seizures.

Mortality.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register (to 29 June 2015) through contact with the Trials' Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review. The Specialised Register contains studies identified from several sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All electronically‐derived citations and abstracts were read by two assessors. All studies, relevant to the use of erythropoietin in kidney failure which might possibly be an RCT or a quasi‐RCT, were identified. Assessment and identification was designed to be sensitive and not precise (specific). This was to avoid missing possible RCTs/quasi‐RCTs. The full published copies of all identified relevant studies were retrieved.

Data extraction and management

The full published hard copies of studies identified through electronic searching and by our other methods of study ascertainment were assessed for subject relevance, eligibility for inclusion in our review and methodological quality. A standard form, which recorded details of quality of randomisation (particularly security of concealment of randomisation), blinding, description of withdrawals/dropouts and numbers lost to follow‐up and whether intention‐to‐treat analysis was possible on the available data, was used for this quality assessment. If it was unclear from the published study whether it met the methodological inclusion criteria the authors were contacted. These studies remained excluded unless the authors confirmed that our eligibility criteria had been met. Assessment was undertaken by two assessors independently, one of whom was a clinician (nephrologist). If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion a third assessor made the final decision. The assessors were not blind to author, institution or journal. Where appropriate, studies were translated prior to methodological assessment.

Studies which met the criteria for methodological quality and subject relevance for this review passed to the stage of data abstraction. Data relevant to the pre‐stated outcome measures, the characteristics of the study, interventions and participants were abstracted by a single assessor on to a data abstraction form generated for this review. Data relevant to study methodology had already been abstracted onto the quality assessment form. These data were then, where appropriate, entered by a single researcher into Review Manager. No raw data were sought from the authors. Apart from translation by the authors and ascertainment of study methodology all data were obtained from the published paper or abstract.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the 2016 update all studies were reassessed using the risk of bias assessment tool (Appendix 2) (Higgins 2011).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Where appropriate, data were quantitatively combined using meta‐analysis to determine the typical effect of the intervention. We calculated a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous data and a mean difference (MD) or a standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous data. A random effects model was used for analyses of both dichotomous and continuous data. Following the convention of the Cochrane Collaboration, all comparisons were framed in terms of unfavourable events such as adverse symptoms or death. RRs of less than one therefore favour the experimental treatment while RRs greater than one favour the control treatment. Ninety‐five per cent confidence intervals (95% CI) were derived for all comparisons.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Evidence of statistical heterogeneity across studies was explored using the Chi‐squared test for heterogeneity and the I2 test (Higgins 2003).

Data synthesis

Data which could not be combined quantitatively were presented in a narrative form.

Certain outcomes were expressed as negative values so that the estimated effect size would lie on the left side of the line of no effect. These outcomes were;

GFR: a higher GFR (mL/min) indicates better kidney function.

Haemoglobin and haematocrit levels: a higher haemoglobin (g/dL) or haematocrit level (%) is considered a beneficial outcome.

Quality of life measures: a higher quality of life measure is a beneficial outcome.

Change in exercise capacity: a higher score in change in exercise capacity (watts (W)) is a beneficial outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Studies were also examined for methodological and clinical heterogeneity particularly if significant statistical heterogeneity was identified (Thompson 1994).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

2001 review

Twelve studies (Abraham 1990; Brown 1995; Clyne 1992; Eschbach 1989; Kleinman 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Lim 1989; Roth 1994; Stone 1988; Teehan 1989; Teehan 1991; Watson 1990) with a total of 232 participants, reported in published papers, one in abstract form (Brown 1995), were included in the review after methodological assessment. Four studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989; Lim 1989; Stone 1988) formed part of a larger multicentre study (Teehan 1991). If an outcome measure was common to both a small study and the multicentre study, only the results from the multicentre study were included in the meta‐analysis (see Characteristics of included studies); the smaller studies were analyses of individual centres’ data.

Ten studies were conducted in the USA, one in Sweden (Clyne 1992), and one in Japan (Kuriyama 1997). The majority of studies had few participants and were of short duration (8 to 12 weeks) not long enough to assess the effects on the progression of kidney disease. Only three studies (Brown 1995; Kuriyama 1997; Roth 1994) were of longer duration between 36 weeks and one year, however Brown 1995 only included 17 participants.

2005 review update

For the 2005 update of the review, three studies (Ganguli 2003; Teplan 2001b; Teplan 2003) were identified for inclusion, and 10 were excluded either because they did not fit the inclusion criteria of the review or it was unclear how patients had been allocated to groups. This brought the total number of included studies to 15. For the update some authors (Mignon 2001; Teplan 2003) were contacted to seek clarification on how patients were allocated to groups and for data which could be included in the review. Teplan confirmed patients were randomised and that Teplan 2001b was a separate sample of participants from Teplan 2003. No response was received for Mignon and this study was excluded as it appeared both groups received erythropoietin. Unfortunately no additional data were received from Ganguli 2003 and Teplan 2001b.

These new studies were conducted in India (Ganguli 2003) and the Czech Republic (Teplan 2001b; Teplan 2003). The number of participants ranged from 36 to 186 and the duration of the studies was six months to three years.

2016 review update

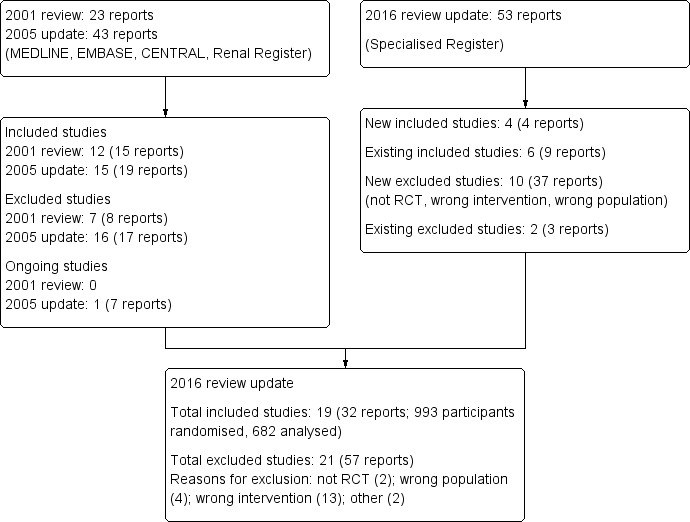

This update found an additional four studies (four reports) (Akizawa 1993; Kim 2006e; Kristal 2008; Wang 2004b). Three studies were only available as abstracts (Akizawa 1993; Kim 2006e; Wang 2004b). Therefore a total of 19 studies have been included in this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

These new studies were conducted in Japan (Akizawa 1993), Korea (Kim 2006e), Israel (Kristal 2008), and Hong Kong (Wang 2004b). The number of participants ranged from 40 to 107 and the duration of the studies was 12 weeks to 21 months.

Because the benefit of EPO therapy is now established for patients with CKD not yet on dialysis, further updates of this review with the addition of studies comparing EPO with placebo or no treatment are unnecessary and therefore this review will no longer be updated.

Risk of bias in included studies

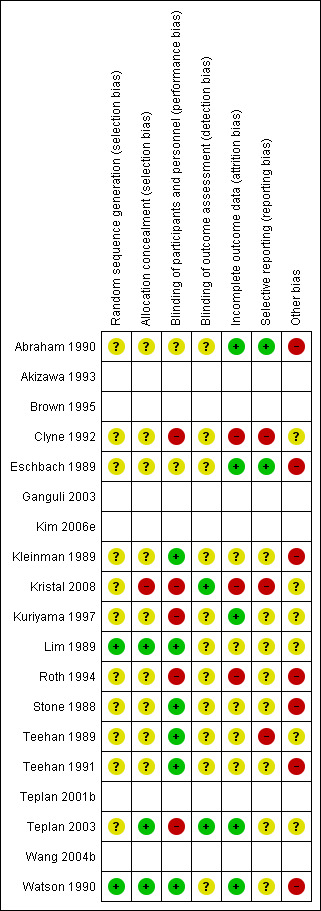

The risk of bias was reassessed for 13 studies; for the six studies only reported as a conference abstract (Akizawa 1993; Brown 1995; Ganguli 2003; Kim 2006e; Teplan 2001b; Wang 2004b) the risk of bias was not assessed resulting in blank rows in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. The empty rows relate to abstract‐only publications ‐ risk of bias could not be assessed

Allocation

Random sequence generation was at low risk of bias in two studies (Lim 1989; Watson 1990) and unclear in 11 studies

Allocation concealment was at low risk of bias in three studies (Lim 1989; Teplan 2003; Watson 1990), high in Kristal 2008 (patients allocated according to visit to clinic), and unclear in nine studies.

Blinding

Performance bias was assessed as high in five studies; two explicitly stated there was no blinding of patients or health care providers (Clyne 1992; Roth 1994), and three studies randomised the control group to no treatment (Kristal 2008; Kuriyama 1997; Teplan 2003). Six studies were assessed as being at low risk of performance bias (Kleinman 1989; Lim 1989; Stone 1988; Teehan 1989; Teehan 1991; Watson 1990) and performance bias was unclear in two studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989).

Detection bias was low in two studies (Kristal 2008; Teplan 2003) and unclear in the remaining 11 studies.

Incomplete outcome data

Five studies (Clyne 1992; Kleinman 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Lim 1989; Roth 1994) mentioned the numbers and reasons for withdrawals or dropouts. Attrition bias was low in five studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Teplan 2003; Watson 1990), high in three studies (Clyne 1992; Kristal 2008; Roth 1994) and unclear in five studies.

Selective reporting

Reporting bias was low in two studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989), high in three studies (Clyne 1992; Kristal 2008; Teehan 1989), and unclear in eight studies.

Other potential sources of bias

Other potential biases were high (industry funding) in seven studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989; Kleinman 1989; Roth 1994; Stone 1988; Teehan 1991; Watson 1990) and unclear in six studies.

Effects of interventions

Measures of progression of kidney failure

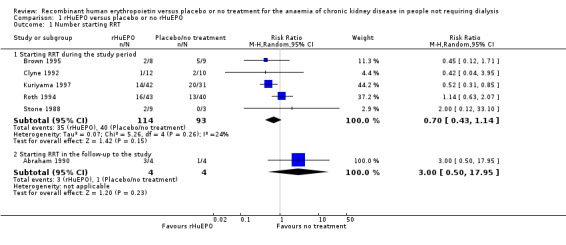

Number of patients starting renal replacement therapy during study period

Five studies (Brown 1995; Clyne 1992; Kuriyama 1997; Roth 1994; Stone 1988) with a total of 207 patients recorded data on the number of patients starting RRT during the study period. Overall the numbers starting dialysis (Analysis 1.1.1 (5 studies, 207 participants): RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.14; I2 = 24%) showed no evidence of a difference between the two groups. The confidence interval is sufficiently wide for a clinically and economically important difference to exist. There was no evidence of heterogeneity. The different lengths of study duration should be considered when interpreting these data. The study periods ranged from 8 to 10 weeks for three studies (Brown 1995; Clyne 1992; Stone 1988), 48 weeks for Kuriyama 1997 and Roth 1994, and 36 months for Teplan 2003. In the study by Teplan 2003 there was no mention of anyone progressing to dialysis presumably because their progression of kidney failure was less advanced (serum creatinine 2.79 ± 0.97 mg/dL).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 1 Number starting RRT.

Akizawa 1993 reported that the proportions of patients with deteriorating kidney function did not differ between groups.

Time to commencement of dialysis

Only Roth 1994 reported data on time from start of rHuEPO therapy to onset of dialysis. The time to start of dialysis for patients receiving rHuEPO (43) compared with those not receiving rHuEPO (40) was not statistically significant at conventional levels, Kaplan ‐ Meier survival curves (Log‐rank test P = 0.99).

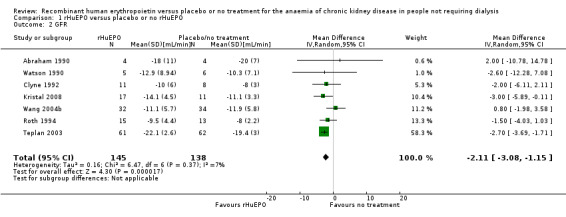

GFR at the end of study

Seven studies (Abraham 1990; Clyne 1992; Kristal 2008; Roth 1994; Teplan 2003; Wang 2004b; Watson 1990) compared GFR in a manner that allowed the data to be combined (i.e. reported both means and standard deviations). The overall estimate of effect favoured treatment and while this was statistically significant it was not clinically significant (Analysis 1.2 (7 studies, 283 participants): (MD ‐2.11 mL/min, 95% CI ‐3.08 to ‐1.15; participants = 283; studies = 7; I2 = 7%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 2 GFR.

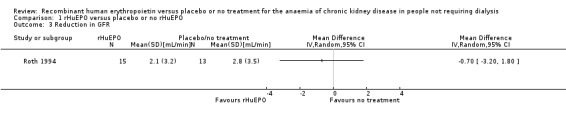

Reduction in GFR

Roth 1994 recorded change in GFR. Of the original 83 participants reduction in GFR was only available for 28 participants at the end of the study. The result was not statistically significant (Analysis 1.3: MD of ‐0.70 mL/min, 95% CI ‐3.20 to 1.80).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 3 Reduction in GFR.

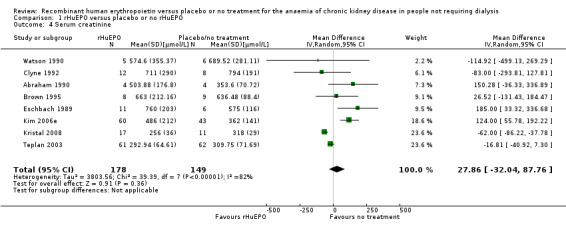

Serum creatinine at end of study

Eight studies (Abraham 1990; Brown 1995; Clyne 1992; Eschbach 1989; Kristal 2008; Kim 2006e; Teplan 2003; Watson 1990) measured serum creatinine at the end of the study period in a way that could be incorporated into the meta‐analysis. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (Analysis 1.4 (8 studies, 327 participants): MD 27.86 µmol/L, 95% CI ‐32.04 to 87.76; participants = 327; studies = 8; I2 = 82%). There was significant heterogeneity between studies; differences in baseline serum creatinine were not taken into account in this analysis which may have accounted for this.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 4 Serum creatinine.

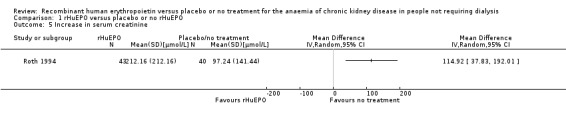

Change in serum creatinine from baseline

Only Roth 1994 reported change in serum creatinine in a form which could be entered for analysis. Although this showed a significantly greater rise in creatinine at the end of the study with participants receiving rHuEPO (Analysis 1.5 (1 study, 83 participants): MD 114.92 μmol/L, 95% CI 37.83 to 192.01), other included studies reported data which were not consistent with this finding. Teehan 1991 reported mean change in serum creatinine without standard deviations and found no significant difference between participants treated with rHuEPO and those receiving placebo (P > 0.05). Kleinman 1989 recorded the change in kidney function by measuring the change in the slope of the inverse of serum creatinine over time and concluded that there was no statistical difference between those receiving rHuEPO and the controls (P = 0.83). Eschbach 1989 reported the inverse of serum creatinine level multiplied by 100 as the measure of change in kidney function. The slopes were determined for each patient and the pre‐ and post‐treatment slopes compared. There was no significant change (P = 0.78) in the rate of decline of kidney function after a median of 12 months of rHuEPO therapy. Teehan 1991 measured the inverse of serum creatinine as a function of time for 83 participants in whom serum creatinine values were available for at least two months before and after the study; the slopes did not increase after initiation of rHuEPO therapy.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 5 Increase in serum creatinine.

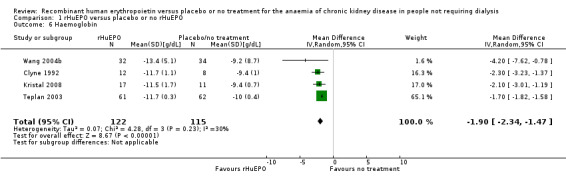

Measures of correction of anaemia

Haemoglobin at the end of the study

Four studies (Clyne 1992; Kristal 2008; Teplan 2003; Wang 2004b) reported haemoglobin at the end of the study. rHuEPO significantly increased Hb compared to placebo or no treatment (Analysis 1.6 (4 studies, 237 participants): MD 1.90 g/dL, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.34; I2 = 30%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 6 Haemoglobin.

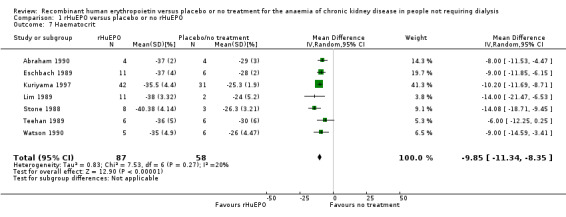

Haematocrit at the end of the study

Seven studies (Abraham 1990; Eschbach 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Lim 1989; Stone 1988; Teehan 1989; Watson 1990) reported haematocrit levels at the end of the study period in a manner that could be combined in a meta‐analysis. rHuEPO significantly improved haematocrit compared to placebo or no treatment (Analysis 1.7 (7 studies, 145 participants): MD 9.85%, 95% CI 8.35 to 11.34; I2 = 20%). Three additional studies measured haematocrit levels results of which could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Kleinman 1989 presented data without standard deviations and showed at the end of the study that a haematocrit of 35.8% was achieved for those treated with rHuEPO compared with 28.3% for the placebo group (P = 0.004). Roth 1994 noted mean haematocrit (again no standard deviations) were available. He reported, however, that correction of anaemia to at least 36% was achieved in 34/43 participants receiving rHuEPO compared with none in the control group. Teehan 1991 demonstrated that 90% of participants treated with 150 units rHuEPO/kg of body weight, 79% who received 100 units and 57% receiving 50 units responded to therapy (defined as an increase of six percentage points in haematocrit) compared with a response rate of 10% in the placebo group. This response rate of 10% was based on an increase in haematocrit, on a single occasion in three placebo participants.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 7 Haematocrit.

Change in haemoglobin or haematocrit levels

No study recorded change in haemoglobin or haematocrit in a form that could be used in a meta‐analysis and no study recorded data on haemoglobin values one to three months after commencement of RRT.

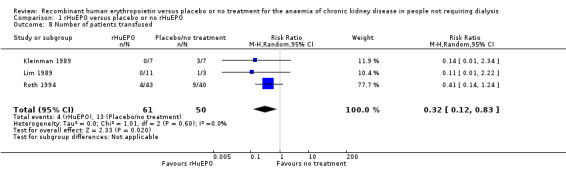

Number of participants requiring blood transfusions

Three studies (Kleinman 1989; Lim 1989; Roth 1994) reported the number of participants who required blood transfusions. the number requiring blood transfusions in the rHuEPO group was significantly less than those in the placebo or no treatment group (Analysis 1.8 (3 studies, 111 participants): RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.83; I2 = 0%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 8 Number of patients transfused.

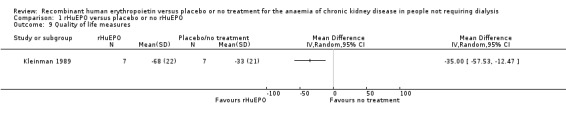

Quality of life measures at the end of the study period

Only Kleinman 1989 recorded data on quality of life in a manner suitable for analysis (reported means and standard deviations). Quality of life was assessed by asking participants to:‐

"Rate your energy level during the past week"

"Judge your ability to do work during the previous week"

"Rate your overall quality of life during the past week"

Participants treated with rHuEPO had a better quality of life after 12 weeks. There was evidence of a statistically significant difference between the two groups favouring treatment with rHuEPO (Analysis 1.9: MD 35.00, 95% CI 12.47 to 57.53).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 9 Quality of life measures.

Roth 1994 used a health‐related quality of life (HRQL) assessment carried out at 16, 32 and 48 weeks. Scales from the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) were used. Four scales taken from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form and other Medical Outcome Study measures, which have demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability, were also included. During the 48 weeks of follow up the control group showed a significant decrease in physical function (P = 0.03); those receiving rHuEPO showed significant increases in energy (P = 0.045) and physical function (P = 0.015). The results from Kleinman 1989 and Roth 1994 could not be combined as different measures were used. Lim 1989 reported that all 11 participants who received rHuEPO experienced an increased sense of well‐being, felt more energetic and were more able to perform their work. Ganguli 2003 reported a significant improvement in quality of life and work capacity in those receiving EPO.

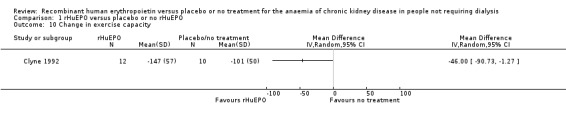

Change in exercise capacity

Only data from Clyne 1992 could be entered in the analysis. A standardised exercise test was performed using a bicycle ergometer. Clyne 1992 demonstrated a marginally significant result favouring treatment with rHuEPO (Analysis 1.10: MD 46.00 W, 95% CI 1.27 to 90.73). Participants in Teehan 1991 completed questionnaires before and after the study, rating their energy levels and ability to do work during the previous week. Teehan 1991 concluded that correction of anaemia was associated with significant improvements in participants' energy levels.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 10 Change in exercise capacity.

Measures of blood pressure control

Blood pressure measurements

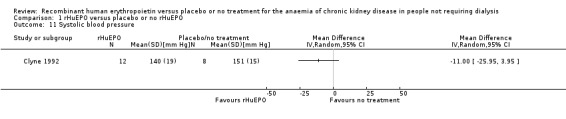

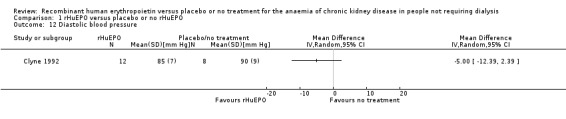

Clyne 1992 measured systolic blood pressure at the end of the study. The point‐estimate favours treatment, however the result was not statistically significant (Analysis 1.11: MD ‐11.00 mm Hg, 95% CI ‐25.95 to 3.95). Abraham 1990 recorded mean arterial blood pressure and showed no evidence of a significant difference between the groups. Kleinman 1989 measured changes in systolic blood pressure but no standard deviations were reported and hence the data could not be used in the analysis; the investigators however reported no evidence of a significant increase in blood pressure for several months after the study although several participants had begun dialysis at that time. An analysis by Teehan 1991 showed no statistically significant difference either in systolic or diastolic blood pressure at the end of the study. He also reported that no medically significant change occurred in any treatment group. Watson 1990 reported that there were no major problems with blood pressure. No study reported change in systolic blood pressure in a form that could be entered for analysis. Roth 1994 however, reported that the change in systolic blood pressure during the study was not significantly different between the group receiving rHuEPO and the control group (P = 0.67). Diastolic blood pressure at the end of the study was reported by Clyne 1992 and showed a lower diastolic blood pressure at the end of the study in those receiving rHuEPO but the difference was not significant (Analysis 1.12: MD ‐5.00, 95% CI ‐12.39 to 2.39).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 11 Systolic blood pressure.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 12 Diastolic blood pressure.

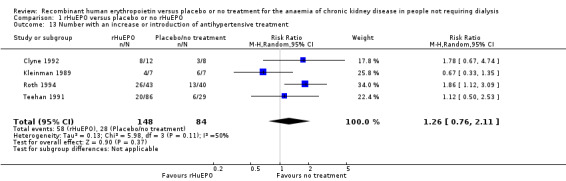

Antihypertensive treatment

Seven studies reported data on numbers of participants in whom there was an increase in or introduction of antihypertensive treatment. Data in Abraham 1990, Lim 1989 and Stone 1988 formed a subset of those in the multicentre study of Teehan 1991, and hence only Teehan 1991 data were used in the meta‐analysis. Of the four remaining studies (Clyne 1992; Kleinman 1989; Roth 1994; Teehan 1991) three showed that there was a more frequent need to increase or introduce antihypertensive treatment in participants receiving rHuEPO. The overall estimate of effect was not statistically significant (Analysis 1.13 (4 studies, 232 participants): RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.11; I2 = 50%), however the CIs were sufficiently wide enough to include a clinically important difference. There was some evidence of heterogeneity between the studies however this was not significantly different (P = 0.11). Eschbach 1989 recorded that 11 participants required an increase in or initiation of antihypertensives but the study did not report to which groups the participants belonged. Clyne 1992 reported that in 4/12 participants receiving rHuEPO therapy, rHuEPO treatment was stopped until blood pressure was controlled. It is worth noting that in the earlier studies higher doses of rHuEPO were used than is used in current practice.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 13 Number with an increase or introduction of antihypertensive treatment.

Other adverse events

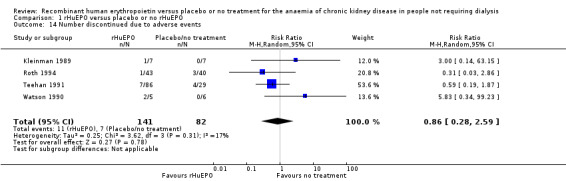

Discontinued treatment due to adverse events

Four studies (Kleinman 1989; Roth 1994; Teehan 1991; Watson 1990) recorded numbers of participants discontinuing treatment due to adverse events including sepsis, myocardial infarction, nausea and vomiting, and suspicion of acceleration of kidney failure. There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment and control groups (Analysis 1.14 (4 studies, 223 participants): RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.59; I2 = 17%). Eschbach 1989 and Roth 1994 both reported "no adverse events attributable to rHuEPO therapy".

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 14 Number discontinued due to adverse events.

Access problems for patient commenced on haemodialysis

Kleinman 1989 was the only study to report on venous access (arterio‐venous fistula/synthetic graft) problems. Two of seven participants in each group had either an arterio‐venous fistula or bovine graft in preparation for haemodialysis and there were no clotting episodes.

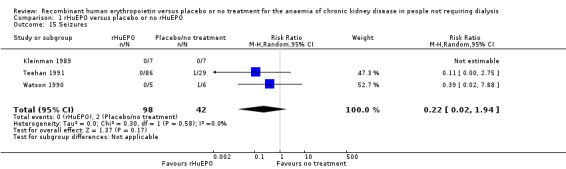

Seizures

Three studies reported seizures (Kleinman 1989; Teehan 1991; Watson 1990). Teehan 1991 and Watson 1990 reported one seizure in each of their studies in the control group and Kleinman 1989 reported there were no seizures during the course of their study (Analysis 1.15 (3 studies, 140 participants): RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.94; I2 = 0%).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 15 Seizures.

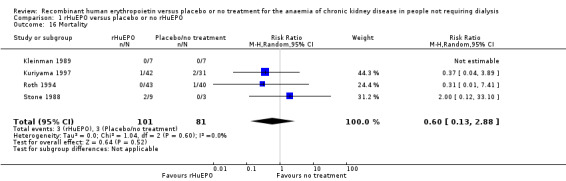

Mortality

Mortality was reported in four studies (Kleinman 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Roth 1994; Stone 1988). Kuriyama 1997, Roth 1994 and Stone 1988 recorded data on mortality within their studies, however, the wide confidence interval reflects the small number of events (six deaths in total). Kleinman 1989 reported there were no deaths during the course of the study (Analysis 1.16 (4 studies, 182 participants): RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.13 to 2.88; I2 = 0%).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO, Outcome 16 Mortality.

Discussion

This review has generated no clear evidence that rHuEPO treatment has either a beneficial or adverse effect on the progression of CKD or on the timing of initiation of dialysis. Though a formal meta‐analysis, of quality of life and exercise capacity measures were not possible, all the studies reporting these outcomes demonstrated statistically significant differences favouring treatment with rHuEPO. There was no statistically significant result as regards deterioration in blood pressure control or seizure necessitating withdrawal of treatment, however study duration was short and the confidence intervals wide. The combined results from two studies (Teehan 1991; Watson 1990) provide no evidence that rHuEPO treatment was associated with seizures although the short duration of most of the studies resulted in very few events. The meta‐analysis of four studies did not indicate a significant increase in the number of participants in whom antihypertensives were introduced, although as the confidence interval is wide this could not be ruled out. The increase in the use of antihypertensives in some of the studies could have been as a result of the higher doses of rHuEPO used in some of the earlier studies, lower doses are now used. The review also generated convincing evidence that predialysis rHuEPO does correct renal anaemia and reduces blood transfusion requirements.

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was not one of the predetermined outcomes of this review. Though it may be an independent predictor of mortality in participants with CKD (Harnett 1995; Levin 1996) it is clearly a surrogate marker. There is no convincing evidence that reversing or delaying the progression of LVH has an impact on mortality, morbidity or quality of life. If such evidence becomes available it would support LVH becoming an outcome measure in future RCTs and systematic reviews in this area.

GFR was statistically significantly higher at the end of the study period in the rHuEPO treated group. This result was driven mainly by Teplan 2003 included in this first update. The difference of 2.5 mL/min may however not be clinically significant. In addition the numbers are still small and the GFR was higher at the beginning of Teplan 2003 in the rHuEPO group and when we calculated the relative risk this difference was statistically significant. This imbalance was not incorporated into the meta‐analysis.

It is regrettable that none of the included RCTs continued follow‐up beyond commencement of dialysis. It is possible that participants whose haemoglobin/haematocrit has been partially corrected by rHuEPO may have less morbidity, less hospitalisation, less initial rHuEPO requirements and consume less health care resources around the period of dialysis commencement.

A number of characteristics of the included studies make it difficult to demonstrate either clear evidence of benefit or lack of benefit of predialysis rHuEPO. Many of the studies were of short duration not long enough to assess the effects on the progression of kidney disease and included small numbers of randomised participants. Participants were not equally distributed between treatment and placebo groups in 7/15 studies (Clyne 1992; Eschbach 1989; Kuriyama 1997; Lim 1989; Roth 1994; Stone 1988; Teehan 1991). The way data were reported in many of the studies included in this review (without means or measures of dispersion) made incorporation into a meta‐analysis impossible and thus the statistical power of combined patient numbers could not always be utilised. Teplan 2003 was one of the largest studies and longest duration of 36 months, and contributed to the statistically significant result in the GFR favouring EPO, although clinical significance is questionable. There was no mention of any of the participants progressing to dialysis, presumably because their kidney failure was less advanced, a follow‐up study of these participants to start of dialysis would be interesting.

With the exception of two studies (Brown 1995; Kuriyama 1997) which included participants with diabetes, the studies generally excluded participants with significant comorbidity. The results of this review may not be generalisable to the present predialysis patient population.

This review also demonstrated the potential pitfall of double‐counting randomised participants in systematic reviews when some individual centres in a multi‐centre RCT publish their data separately in addition to their inclusion in the full report of the complete RCT. All the reports from multi‐centre RCTs should clearly describe the involvement of all centres and highlight any previous or potential future publications derived from the RCT.

In summary there was a marked improvement in measures of anaemia with the treatment and a decrease in the number of participants requiring blood transfusion. Though difficult to summarise, the data from all studies which reported quality of life or exercise capacity demonstrated an improvement in the rHuEPO group. Only one of the measures of progression of kidney disease (GFR) (when a summary statistic was calculated) demonstrated a statistically significantly difference but with questionable clinical significance. Hence there is no evidence from this review of the hypothesised delay in requirement for RRT or of a further deterioration in kidney function attributable to rHuEPO treatment. The requirement for antihypertensive treatment appears not to be increased by rHuEPO therapy and there was no other statistically significant increase in adverse events.

The addition of four studies in 2016 did not alter the conclusions of the review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The benefits of rHuEPO treatment in predialysis participants are that it corrects anaemia and avoids the requirement for blood transfusions. In the long term the critical question as to whether treatment with rHuEPO either speeds or delays the onset of RRT remains unanswered.

Implications for research.

A future RCT to look specifically at whether rHuEPO can delay or hasten RRT in patients with chronic kidney failure is required. Nephrology is a low volume specialty and multicentre studies are therefore necessary to recruit sufficient numbers to achieve acceptable statistical power. Further RCTs should be designed to be large enough and of long enough duration to address this question adequately. These studies could also examine the proposition that a patient with a higher haemoglobin is in better health and better able to cope with the commencement of dialysis when it is eventually necessary. Hospitalisation duration for initiation of dialysis, hospitalisation rates and mortality for the first three months of RRT should provide further relatively hard end‐points. Considering the demonstrable effectiveness of rHuEPO in improving haemoglobin it may be impossible to blind health care providers effectively in such a study.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 March 2016 | Review declared as stable | As of January 2016 this Cochrane Review is no longer being updated. The clinical efficacy of rHuEPO compared with placebo or no treatment is now clinically well established. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2001 Review first published: Issue 4, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 June 2015 | New search has been performed | Studies awaiting classification have been resolved |

| 29 June 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Four new studies included with no change to the conclusions |

| 27 February 2014 | Review declared as stable | As of March 2014 this Cochrane Review is no longer being updated. The clinical efficacy of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) is now clinically well established |

| 23 December 2013 | Amended | Search strategies revised and updated |

| 14 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

| 25 May 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

As of January 2016 this Cochrane Review is no longer being updated. The clinical efficacy of rHuEPO compared with placebo or no treatment is now clinically well established.

Acknowledgements

Health Services Research Unit and Health Economics Research Unit are funded by the Chief Scientist's Office, Scottish Office Department of Health. Grateful thanks to Carol Ritchie for secretarial and clerical support. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Paul Lawrence, formerly Chief Librarian of the Medical School Library, University of Aberdeen. Thanks also to Oliver Campbell for undertaking the Internet searching.

We wish to thank Alison MacLeod, Conal Daly, Marion Campbell, Cameron Donaldson, Adrian Grant, Izhar Khan, Susan Pennington, Luke Vale, Sheila Wallace and Kannaiyan Rabindranath who contributed to the 2001 and 2005 reviews.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub‐scales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. rHuEPO versus placebo or no rHuEPO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number starting RRT | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Starting RRT during the study period | 5 | 207 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.43, 1.14] |

| 1.2 Starting RRT in the follow‐up to the study | 1 | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.50, 17.95] |

| 2 GFR | 7 | 283 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.11 [‐3.08, ‐1.15] |

| 3 Reduction in GFR | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Serum creatinine | 8 | 327 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 27.86 [‐32.04, 87.76] |

| 5 Increase in serum creatinine | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Haemoglobin | 4 | 237 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.90 [‐2.34, ‐1.47] |

| 7 Haematocrit | 7 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.85 [‐11.34, ‐8.35] |

| 8 Number of patients transfused | 3 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.12, 0.83] |

| 9 Quality of life measures | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Change in exercise capacity | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 11 Systolic blood pressure | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12 Diastolic blood pressure | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 13 Number with an increase or introduction of antihypertensive treatment | 4 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.76, 2.11] |

| 14 Number discontinued due to adverse events | 4 | 223 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.28, 2.59] |

| 15 Seizures | 3 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.02, 1.94] |

| 16 Mortality | 4 | 182 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.13, 2.88] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Abraham 1990.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Co‐interventions (both groups)

Duration of study: 8 to 12 weeks until goal HCT of 40% (males) or 37% (females) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear, reported to be randomised however method not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear, states "double‐blind placebo‐controlled..." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients completed the first phase of the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | High risk | "Financial support and erythropoietin was provided by Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation, Raritan, N.J., USA" |

Akizawa 1993.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Brown 1995.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Duration of study: 1 year |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Clyne 1992.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron supplementation

Duration of treatment: 12 weeks |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Open randomised parallel‐group study" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Attrition was 1/12 (8%) in the epoetin beta arm and 2/10 (20%) in the control arm. As this was > 10% overall this was judged to be high risk |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Major cardiovascular outcomes were not available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Eschbach 1989.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Patients and physicians blinded were blinded to the identify of the study medication but not the dose |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients completed the short phase study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Portions of this study were funded by research grants from National Institutes of Health and Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation. |

Ganguli 2003.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Control group

Duration of study: 6 months |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Kim 2006e.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Study said to continue for further 21 months but unclear whether all patients received EPO after 3 months |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Kleinman 1989.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron administered

Duration of study: 12 weeks or until HCT of 38% or 40% |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo controlled |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 1 patient withdrew from EPO group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | High risk | Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation was an author on the paper |

Kristal 2008.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

All patients received oral maintenance iron supplementation, calcium bicarbonate, statins, beta‐blockers, and calcium channel blockers |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients allocated in order according to visit to clinic (information from authors) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding; open label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Relevant outcomes were laboratory based and unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 12/40 (30%) did not complete study (3/20 in treatment group and 9/20 in control group) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No report of adverse effects |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Kuriyama 1997.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron: at the investigators discretion Duration of study: 36 weeks |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Control group received no treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Lim 1989.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron administered: ferrous sulphate 300 mg orally 3 x day Folate administered: folic acid 1 mg orally daily Duration of study: 8 weeks |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Third party |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate, third party |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Roth 1994.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron administered: investigators discretion Folate administered: no Duration of study: 48 weeks |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Nor reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 23/43 in the EPO group and 25/40 in the control group did not complete the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | High risk | Funded by Ortho Biotech |

Stone 1988.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Iron administered: ferrous sulphate 300 mg 3 times/day Folate administered: 1 mg daily Duration of study: 8 weeks |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blind, placebo controlled |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | High risk | Funded by Ortho Pharmaceutical |

Teehan 1989.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo controlled |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data for cardiovascular outcomes not available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Teehan 1991.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Folate administered: yes Duration of study: 8 weeks or until HCT reached 40% for men or 37% for women |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 106/117 completed the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | High risk | Part funded by Ortho Pharmaceuticals |

Teplan 2001b.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Control group

Duration of study: 3 years |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Teplan 2003.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1

Treatment group 2

Control group

Duration of study: 36 months |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate; sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only biochemical parameters reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

Wang 2004b.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

Watson 1990.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

Duration of study: 12 weeks or until target HCT of 38% is achieved |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Performed by a third party |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Performed by a third party |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Stated double blind; placebo used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Other bias | High risk | Funded by Ortho Pharmaceuticals |

BP ‐ blood pressure; CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; CrCl ‐ creatinine clearance; EPO ‐ erythropoietin; GFR ‐ glomerular filtration rate; Hb ‐ haemoglobin; HCT ‐ haematocrit; HDL ‐ high‐density lipoprotein; IV ‐ intravenous; LDL ‐ low‐density lipoprotein; M/F ‐ male/female; PCV ‐ packed cell volume; QoL ‐ quality of life; RCT ‐ randomised control trial; RRT ‐ renal replacement therapy; SC ‐ subcutaneous; SCr ‐ serum creatinine; SD ‐ standard deviation; SE ‐ standard error

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Brown 1988 | All patients received EPO |

| CREATE Study 2001 | Comparing the same ESA derivative in different treatment arms |

| EPOCARES Study 2010 | Ineligible population |

| Frenken 1989 | All patients received EPO |

| Frenken 1992 | All patients received EPO |

| Furukawa 1992 | All patients received EPO |

| Jabs 1994 | Not randomised |

| Koene 1990 | All patients received EPO |

| Macdougall 2007 | Compares early with late commencement of EPO |

| Marcas 2003 | All patients received EPO |

| Meloni 2003 | Unclear how patients allocated to groups. Written to authors for clarification |

| Mignon 2001 | All patients received EPO |

| Muirhead 1992 | Haemodialysis patients |

| N0287023177 | All patients received EPO |

| Palazzuoli 2007 | Ineligible population. Cardiac failure patients |

| Pratt 2006 | Compares EPO delta with EPO alpha |

| Schwartz 1989 | Data only from EPO treated patients |

| Singh 1999 | Randomised study. Not all participants were predialysis some had commenced dialysis |

| Teehan 1990 | Unclear if randomised. Wrote to authors all patients received EPO |

| Yamazaki 1993 | All patients received EPO |

| Zheng 1992 | All patients received EPO |

EPO ‐ erythropoietin

Contributions of authors

2001 and 2005 review: JC and MC undertook, independently, the quality assessment of the studies. Data extraction was performed by JC and a sample was double‐checked by SP. Extensive literature searching was performed by SW. JC entered the data and wrote the text of the review. MC and AG gave statistical and methodological advice. AM, CD, KR and IK provided a clinical perspective. CD and LV provided a health economics perspective. All reviewers commented on the review.

2016 review: EH assessed the four studies and updated the review

Declarations of interest

None known.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Abraham 1990 {published data only}

- Abraham PA, Opsahl JA, Rachael KM, Asinger R, Halstenson CE. Renal function during erythropoietin therapy for anemia in predialysis chronic renal failure patients. American Journal of Nephrology 1990;10(2):128‐36. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl JA, Halstenson CE, Rachael KM, Abraham PA. Recombinant‐human erythropoietin (EPO) in chronic renal failure (CRF): no adverse effect on renal hemodynamics or progression of disease [abstract]. Kidney International 1989;35(1):198. [CENTRAL: CN‐00766225] [Google Scholar]

Akizawa 1993 {published data only}

- Akizawa T, Koshikawa S. Effect of rHuEPO on progression of renal disease [abstract]. 12th International Congress of Nephrology; 1993 June 13‐18; Jerusalem, Israel. 1993:300. [CENTRAL: CN‐00764752]

Brown 1995 {published data only}

- Brown CD, Zhao ZH, Thomas LL, Friedman EA. Erythropoietin delays the onset of uremia in anemic azotemic diabetic predialysis patients [abstract]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 1995;6(3):447A. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Clyne 1992 {published data only}

- Clyne N, Jogestrand T. Effect of erythropoietin treatment on physical exercise capacity and on renal function in predialytic uremic patients. Nephron 1992;60(4):390‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eschbach 1989 {published data only}

- Eschbach JW, Kelly MR, Haley NR, Abels RI, Adamson JW. Treatment of the anemia of progressive renal failure with recombinant human erythropoietin. New England Journal of Medicine 1989;321(3):158‐63. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ganguli 2003 {published data only}

- Ganguli A, Singh NP, Ahuja N. A comparative study of nandrolone decanoate and erythropoietin on albumin levels, quality of life, and progression of renal disease in Indian predialysis CKD patients [abstract no: W455]. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2003;18(Suppl 4):692. [CENTRAL: CN‐00653811] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli A, Singh NP, Singh T, Agarwal SK, Neeraj A. Nandrolone decanoate is equiefacious to erythropoietin in correcting anemia and quality of life in predialysis chronic kidney disease patients [abstract no: 137]. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2003;51(Dec):1188. [CENTRAL: CN‐00765715] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NP, Anirban G, Singh T, Agarwal SK, Neera A. Long term effects of anemia correction on progression of renal disease and cognitive function using erythropoietin and androgenic steroids [abstract no: 136]. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2003;51(Dec):1188. [CENTRAL: CN‐00783567] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NP, Ganguli A, Singh T. A comparative study of nandrolone decanoate versus recombinant human erythropoietin on anemia in Indian predialysis chronic kidney disease patients [abstract no: W456]. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2003;18(Suppl 4):692‐3. [CENTRAL: CN‐00447760] [Google Scholar]

Kim 2006e {published data only}

- Kim BS, Do JY, Kim DJ, Kim Y, Kim C, Park S, et al. Renal outcome of CKD patients with predialysis erythropoietin therapy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study [abstract no: TH‐FC057]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2006;17(Abstracts):13A. [CENTRAL: CN‐00766279] [Google Scholar]

Kleinman 1989 {published data only}

- Kleinman KS, Schweitzer SU. Human recombinant erythropoietin (rHuEPO) treatment of severe anemia associated with progressive renal failure may delay the need to initiate regular dialytic therapy [abstract]. Kidney International 1990;37:240. [CENTRAL: CN‐00626057] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman KS, Schweitzer SU, Perdue ST, Abels RI. The use of recombinant human erythropoietin in the correction of anemia in pre‐dialysis patients and its effects on renal function: a double blind placebo controlled trial [abstract]. Kidney International 1989;35(1):229. [CENTRAL: CN‐00636148] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman KS, Schweitzer SU, Perdue ST, Bleifer KH, Abels RI. The use of recombinant human erythropoietin in the correction of anemia in predialysis patients and its effect on renal function: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 1989;14(6):486‐95. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kristal 2008 {published data only}

- Kristal B, Shurtz‐Swirski R, Tanhilevski O, Shapiro G, Shkolnik G, Chezar J, et al. Epoetin‐alpha: preserving kidney function via attenuation of polymorphonuclear leukocyte priming. Israel Medical Association Journal ‐ Imaj 2008;10(4):266‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kuriyama 1997 {published data only}

- Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O. Reversal of anemia by EPO therapy retards the progression of chronic renal failure in non‐diabetic pre‐dialysis patients [abstract]. Nephrology 1997;3(Suppl 1):S506. [CENTRAL: CN‐00461123] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]