Abstract

Background

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are chronic diseases with significant mortality and morbidity. Whilst immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies are frequently used, the optimal therapeutic regimen remains unclear. This is an update of a review first published in 2005.

Objectives

To assess the effects of immunosuppressants and immunomodulatory treatments for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (August 2011), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 3 2011), MEDLINE (January 1966 to August 2011), EMBASE (January 1980 to August 2011) and clinicaltrials.gov (August 2011). We checked the bibliographies of identified trials and wrote to disease experts.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs involving participants with probable or definite dermatomyositis and polymyositis as defined by the criteria of Bohan and Peter, or definite, probable or mild/early by the criteria of Dalakas. In participants without a classical rash of dermatomyositis, inclusion body myositis should have been excluded by muscle biopsy. We considered any immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory treatment. The two primary outcomes were the change in a function or disability scale measured as the proportion of participants improving one grade, two grades etc, predefined based on the scales used in the studies after at least six months, and a 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months. Other outcomes were: the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definition of improvement, number of relapses and time to relapse, remission and time‐to‐remission, cumulative corticosteroid dose and serious adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected papers, extracted data and assessed risk of bias in included studies. They collected adverse event data from the included studies.

Main results

The review authors identified 14 relevant RCTs. They excluded four trials.

The 10 included studies, four of which have been added in this update, included a total of 258 participants. Six studies compared an immunosuppressant or immunomodulator with placebo control, and four studies compared two immunosuppressant regimes with each other. Most of the studies were small (the largest had 62 participants) and many of the reports contained insufficient information to assess risk of bias.

Amongst the six studies comparing immunosuppressant with placebo, one study, investigating intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), showed statistically significant improvement in scores of muscle strength in the IVIg group over three months. Another study investigating etanercept showed some evidence of a longer median time to relapse in the etanercept group, a secondary outcome in this review, but no improvement in other assessed outcomes. The other four randomised placebo‐controlled trials assessed either plasma exchange and leukapheresis, eculizumab, infliximab or azathioprine against placebo and all produced negative results.

Three of the four studies comparing two immunosuppressant regimes (azathioprine with methotrexate, ciclosporin with methotrexate, and intramuscular methotrexate with oral methotrexate plus azathioprine) showed no statistically significant difference in efficacy between the treatment regimes. The fourth study comparing pulsed oral dexamethasone with daily oral prednisolone and found that the dexamethasone regime had a shorter median time to relapse but fewer side effects.

Immunosuppressants were associated with significant side effects.

Authors' conclusions

This systematic review highlights the lack of high quality RCTs that assess the efficacy and toxicity of immunosuppressants in inflammatory myositis.

Plain language summary

Drugs that suppress or modify the immune system for dermatomyositis and polymyositis

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are long‐term inflammatory muscle diseases, causing muscle weakness and disability. For some reason, the body's immune system turns against its own muscles in an autoimmune response. Corticosteroids are the principal treatment but due to side effects, there is a need for additional treatment with drugs that suppress the immune system (immunosuppressants) or modify it (immunomodulatory therapies) to improve patient outcomes. For this review, an update of a review first published in 2005, we found ten randomised trials available, involving 258 participants.

Amongst the six studies comparing immunosuppressant with placebo, one study, investigating intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), showed statistically significant improvement in scores of muscle strength in the IVIg group over three months. Another study investigating etanercept showed some evidence of a longer median time to relapse in the etanercept group, a secondary outcome in this review, but no improvement in other assessed outcomes. The other four randomised placebo‐controlled trials assessed either plasma exchange and leukapheresis, eculizumab, infliximab or azathioprine against placebo and all produced negative results.

Three of the four studies comparing two immunosuppressant regimes (azathioprine with methotrexate, ciclosporin with methotrexate, and intramuscular methotrexate with oral methotrexate plus azathioprine) showed no statistically significant difference in efficacy between the treatment regimes. The fourth study comparing pulsed oral dexamethasone with daily oral prednisolone and found that the dexamethasone regime had a shorter median time to relapse but fewer side effects.

Most of the studies were small (the largest had 62 participants) and many of the reports contained insufficient information to assess risk of bias. Immunosuppressants were associated with significant side effects. The small number of RCTs of immunosuppressants and immunomodulatory therapies are inadequate to decide whether these agents are beneficial in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Two small trials, one of IVIg in dermatomyositis, the other of etanercept in dermatomyositis suggested that they are beneficial. More RCTs are needed.

Background

The inflammatory myopathies include recognised causes of muscle inflammation such as those due to infection by bacteria, viruses and parasites. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies refer to diseases in which muscle inflammation occurs without a recognised infective cause and these include dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Such diseases are thought to result from an auto‐immune process. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are characterised by chronic inflammation of skeletal muscle which can result in persisting muscle weakness with significant disability (Dalakas 1991; Dalakas 2001). They may both occur in association with gastrointestinal, pulmonary and cardiac dysfunction, while only dermatomyositis has skin involvement. The prevalence of idiopathic inflammatory myositis is approximately 11 per 100,000 (Ahlstrom 1993). As idiopathic inflammatory myositis is uncommon, optimal therapy has not been adequately defined (Choy 2002).

Corticosteroids are the principal treatment. Both high‐ and low‐dose corticosteroid regimes are used. In many people, long‐term high dose corticosteroids are necessary to control disease and, in a few people, myositis may be refractory to steroid treatment. Therefore, many people with an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy suffer from the side effects of corticosteroids. The mortality and morbidity of inflammatory myositis remains high despite such treatment (Carpenter 1977; Joffe 1993; Riddoch 1975). Thus, there is a frequent need to use additional treatment both to improve the disease response and to reduce the side effects of corticosteroids.

Immunosuppressive agents, especially azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and ciclosporin, are commonly used in autoimmune diseases as well as in transplant rejection and chronic inflammatory diseases. They are usually employed as second‐line therapy to corticosteroids for disease refractory to steroid treatment alone. They can also be used as adjuvants to steroid treatment to allow reduction in the dosage of corticosteroids and thereby decrease the risk of long‐term complications. While these treatments are in use for dermatomyositis and polymyositis, the optimal therapeutic regimen remains unclear (Choy 2002). Biological agents, in particular the anti‐TNF agents and the B‐cell depleting agent rituximab, are also presently being assessed as potential therapeutic agents in the inflammatory myopathies.

An alternative approach to improving the treatment of dermatomyositis and polymyositis is the use of immunomodulatory therapy. This includes interferon, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and plasma exchange which have proven efficacy in various autoimmune disorders. They are gaining attention as possible second‐line treatment for polymyositis and dermatomyositis (Choy 2002; Dalakas 2001).

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2005.

Objectives

To assess the effects of immunosuppressants and immunomodulatory treatments for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs (trials in which allocation is not strictly random but is based, for example, on case record number or date of birth).

Types of participants

People with probable or definite dermatomyositis and polymyositis as defined by the criteria of Bohan and Peter (Bohan 1975 a; Bohan 1975 b) (Table 1) or definite, probable or mild/early by the criteria of Dalakas (Dalakas 1991) (Table 2). In participants without a classical rash of dermatomyositis, inclusion body myositis should have been excluded by muscle biopsy. If no diagnostic criteria were cited, all the assessors would have judged the quality of evidence for correct diagnosis. The study was included in the review only if the assessors agreed that the participants had probable or definite dermatomyositis or polymyositis.

1. Bohan and Peter criteria.

| Features | Polymyositis | Dermatomyositis |

| 1. Symmetrical proximal muscle weakness | Definite: all 1‐4 | Definite: 5 plus any 3 of 1‐4 |

| 2. Muscle biopsy evidence of myositis | Probable: any 3 of 1‐4 | Probable: 5 plus any 2 of 1‐4 |

| 3. Elevation in serum skeletal muscle enzymes | Possible: any 2 of 1‐4 | Possible: 5 plus any 1 of 1‐4 |

| 4. Characteristic electromyographic pattern of myositis | ||

| 5. Typical rash of dermatomyositis |

2. Dalakas criteria (PM: polymyositis; DM: dermatomyositis).

| Features | Definite PM | Probable PM | Definite DM | Mild/early DM |

| Muscle strength | Myopathic muscle weakness | Myopathic muscle weakness | Myopathic muscle weakness | Seemingly normal strength |

| Electromyographic findings | Myopathic | Myopathic | Myopathic | Myopathic or non‐specific |

| Muscle enzymes | Elevated (up to 50‐fold) | Elevated (up to 50‐fold) | Elevated (up to 50‐fold) or normal | Elevated (up to 10‐fold) or normal |

| Muscle‐biopsy findings | Diagnostic for this type of inflammatory myopathy | Non‐specific myopathy without signs of primary inflammation | Diagnostic | Non‐specific or diagnostic |

| Rash or calcinosis | Absent | Absent | Present | Present |

Types of interventions

Any immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory treatment including corticosteroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, ciclosporin, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, IVIg, interferon and plasma exchange in dermatomyositis and polymyositis, compared with placebo, no treatment or another immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Change in a function or disability scale after at least six months, measured as the proportion of participants improving one grade, two grades etc, predefined based on the scales used in the studies after at least six months. In order to harmonise results we planned to try to convert the results from all studies to either the disability scale that is used in most studies or to one which seemed to us most appropriate.

A 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months.

Secondary outcomes

Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement (DOI) after at least six months. The definitions of improvement use six core set measures among five domains (Oddis 2005; Rider 2004). These core set measures are: the physician global disease activity, parent/patient global disease activity, muscle strength (manual muscle testing (MMT)), physical function assessment, laboratory assessment and extramuscular disease complications. Improvement is defined as occurring if three of any six core set measures improve by 20%, with no more than two worsening by 25% (measures that worsen cannot include manual muscle strength).

Number of relapses and time to relapse.

Remission and time‐to‐remission (remission is modified Rankin score of 0 or 1) (Van Swieten 1988) after at least six months.

Cumulative corticosteroid dose after at least six months.

Serious adverse effects as defined by any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose results in death, is life‐threatening, requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or is a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

In this update we included 'Summary of findings' tables showing our primary outcomes and the first of our secondary outcomes. 'Summary of findings' tables in future updates of the review will include serious adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (August 2011), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 3 2011), MEDLINE (January 1966 to August 2011), EMBASE (January 1980 to August 2011) and clinicaltrials.gov (August 2011) for articles including the terms 'corticosteroids', 'anti‐metabolites' or 'azathioprine' or 'mercaptopurine' or 'methotrexate' or 'ciclosporin' or 'cyclosporin' or 'chlorambucil' or 'cyclophosphamide' or 'immunoglobulin' or 'interferon', 'gamma globulin' or 'plasma exchange' or 'plasmapheresis' or 'immunosuppressant' or 'immunosuppression' and 'dermatomyositis' or 'polymyositis' or 'inflammatory myositis' or 'myositis' and 'randomised controlled trial'. We searched clinicaltrials.gov (completed studies as of August 2011) for completed studies using the terms 'Myositis', 'polymyositis' and 'dermatomyositis'. We undertook a manual search using the bibliographies of trials identified. We also wrote to known disease experts and authors of trials that we discovered, asking them for more information about their trials and whether they knew of trials other than those which we identified.

Electronic database strategies

For detailed search strategies please see: Appendix 1 (CENTRAL), Appendix 2 (MEDLINE), Appendix 3 (EMBASE) and Appendix 4 (Clinicaltrials.gov).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the previous version of the review, two review authors (EC and JH) independently selected trials and four authors independently assessed each study.

For the update two review authors (JW and PG) independently selected trials from the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register (August 2011), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL) (August 2011), clinicaltrials.gov (August 2011), MEDLINE (January 1966 to August 2011) and EMBASE (1980 to August 2011).

Two review authors (JH and PG) independently assessed each study except one, in which JH was an author, which JW and PG independently assessed. The review authors recorded methodological criteria and the results of each study on data extraction forms.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JH and PG) independently assessed the risk of bias for each trial using the domain based 'Risk of bias' tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011). In one trial JH was an author and therefore PG and JW independently assessed the risk of bias in this study.

We assessed the risk of bias as high, low or unclear based on the following questions, each representing a domain.

• Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? • Was allocation adequately concealed? • Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? • Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? • Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? • Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

We then used the results to create the 'Risk of bias' tables presented in this review. Where the two review authors (JH and PG or PG and JW) could not agree on an domain, this was settled by a third author (JW or JH).

Data synthesis

If sufficient data had been available, we would have performed meta‐analysis using the Cochrane statistical software, Review Manager 5.1 (RevMan) (RevMan 2011). We would have expressed results as risk ratios (RR) and risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. We would have carried out tests for homogeneity. If there had been evidence of heterogeneity, we would have performed sensitivity analysis and excluded trials of lowest quality.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We would have analysed the following subgroups when possible.

Younger (up to 18 years of age) versus older.

Reason for failure of initial treatment (corticosteroids) in case of second‐line intervention: inadequate response versus unacceptable side effects.

Diagnostic subgroups: polymyositis versus dermatomyositis versus myositis associated with other connective tissue disease versus myositis in the presence of cancer.

Myositis‐specific autoantibodies: participants with autoantibodies versus participants without autoantibodies (Bunch 1980).

Sensitivity analysis

We would have carried out sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of using different diagnostic criteria on outcome: probable and definite versus definite only (Bohan 1975 a; Bohan 1975 b) versus Dalakas 1991 versus non‐specified.

Results

Description of studies

The number of papers found by the new, current strategies are: MEDLINE 774; EMBASE 1880; Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group Specialized Register 30 (14 new papers); CENTRAL 43; and clinicaltrials.gov 77. From the searches we identified fourteen potentially relevant RCTs (Bunch 1980; Bunch 1981; Chung 2007; Coyle 2008; Dalakas 1993; Donov 1995; Fries 1973; Miller 1992; Miller 2002; Muscle Study Group 2011; Takada 2002; Vencovsky 2000; Van de Vlekkert 2010; Villalba 1998). Ten are full publications in peer reviewed journals, four are only published as abstracts (Coyle 2008; Donov 1995; Miller 2002; Takada 2002). Two of the studies included authors who were also authors of this review (Miller 2002 (JW) and Van de Vlekkert 2010 (JH)). We excluded four trials (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded one as it was an open unblinded follow‐up of another study included in this review, and one because the agent being investigated was not felt to be immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory. We excluded the third because we could not confirm that the participants had polymyositis on the basis of the inclusion criteria. We excluded the fourth study as there was no evidence of randomisation or blinding.

The characteristics of the ten selected studies are listed in Characteristics of included studies.

We identified 10 ongoing studies, which are described in Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Study designs

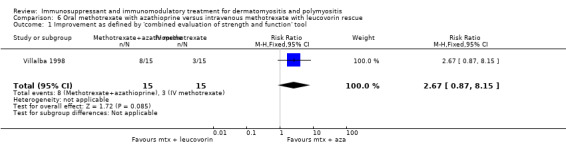

Six studies compared immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory therapy with placebo (Bunch 1980; Coyle 2008; Dalakas 1993; Miller 1992; Muscle Study Group 2011; Takada 2002), four trials compared one immunosuppressant regime with another: one compared ciclosporin with methotrexate (Vencovsky 2000), one methotrexate with azathioprine (Miller 2002), one oral daily prednisolone with pulsed oral dexamethasone (Van de Vlekkert 2010) and the fourth trial compared intravenous methotrexate with oral methotrexate plus azathioprine (Villalba 1998). Three trials were cross‐over studies (Coyle 2008; Dalakas 1993; Villalba 1998).

Participants

All trials recruited adults over 18 years of age. SIx trials included participants with either polymyositis or dermatomyositis (Coyle 2008; Miller 1992; Miller 2002; Vencovsky 2000; Villalba 1998; Van de Vlekkert 2010), one trial studied polymyositis participants only (Bunch 1980) while the other three only included dermatomyositis participants (Dalakas 1993; Muscle Study Group 2011; Takada 2002). The Bohan and Peter diagnostic criteria (Bohan 1975 a; Bohan 1975 b) were the most frequently used. Muscle biopsies were performed in five studies (Bunch 1980; Coyle 2008; Dalakas 1993; Miller 1992; Vencovsky 2000). Three of the six trials that included participants with polymyositis specifically stated exclusion of inclusion body myositis (Miller 1992; Vencovsky 2000; Villalba 1998). A fourth, reported in abstract, is known to have excluded inclusion body myositis (Miller 2002). A fifth excluded participants who had three or more three rimmed vacuoles per 1000 muscle fibers on muscle biopsy (Van de Vlekkert 2010).

Interventions

The interventions studied included the following.

Monthly infusions of 2 g/kg of immunoglobulin or placebo for three months (Dalakas 1993).

Plasma exchange, leukapheresis or sham apheresis with twelve treatments given over a one month period (Miller 1992).

Azathioprine 2 mg/kg/day or placebo for three months in addition to 60 mg of prednisolone daily (Bunch 1980).

Prednisolone and either low‐dose methotrexate (15 mg weekly) or azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg daily) for one year (Miller 2002).

Methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg (mostly 10 mg) orally weekly or ciclosporin 3.0 to 3.5 mg/kg/day for at least six months (Vencovsky 2000).

Oral methotrexate up to 25 mg weekly with azathioprine 150 mg daily for six months or intravenous methotrexate 500 mg/m2 every two weeks for 12 treatments each with leucovorin rescue (50 mg/m2 every six hours for four doses) (Villalba 1998).

Infliximab 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6 and 14 or placebo (Coyle 2008).

Eculizumab (a humanised monoclonal antibody to C5 that inhibits cleavage of C5) 8 mg/kg weekly for five weeks then two‐weekly for a further two doses or placebo (Takada 2002).

Oral dexamethasone pulse therapy or oral daily prednisolone (Van de Vlekkert 2010).

Etanercept (50mg subcutaneously weekly) or placebo for 52 weeks (Muscle Study Group 2011).

Outcomes

Function or disability was assessed in eight trials using the modified Convery Assessment Scale (Miller 1992; Villalba 1998), the modified Rankin scale (Van de Vlekkert 2010), the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (Muscle Study Group 2011), the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF‐36) (Van de Vlekkert 2010), ad hoc scales (Dalakas 1993; Vencovsky 2000), time to arise from a chair and time to walk 30 feet (Muscle Study Group 2011), the Neuromuscular Symptom Score (NSS) (Dalakas 1993; Van de Vlekkert 2010), the individualised neuromuscular quality of life questionnaire (Muscle Study Group 2011) or timed walk (Miller 2002).

Improvement in MMT by 15% or more was used as a defined outcome in one study (Coyle 2008) and could be inferred from another (Dalakas 1993).

Assessment of muscle strength was done by MMT in eight of the selected trials. Two used the standard six point MRC scale, (Miller 1992; Villalba 1998), one the five point MRC scale (Van de Vlekkert 2010) and two expanded MRC scales, one an eight point scale (Dalakas 1993) and one an expanded 13 point scale (Muscle Study Group 2011). One study used a non‐standard scale (with 0 being normal and ‐4 being no movement) (Bunch 1980). Two, published in abstract form only, did not define the MMT scale used (Coyle 2008; Takada 2002). The studies also varied in the number of muscle groups assessed. One used 26 muscle groups (Muscle Study Group 2011), two used 18 muscle groups (Bunch 1980; Dalakas 1993), two used 16 muscle groups (Miller 1992; Villalba 1998) but one of these did not specify the muscle groups used (Miller 1992) and one used 15 muscle groups (Van de Vlekkert 2010). Two published in abstract form only did not include the number of muscle groups used (Coyle 2008; Takada 2002).

In the majority of studies the MMT results were expressed as a sum score, this being the addition of all the scores from all the muscles tested, and maximum sum scores were therefore 80 (Miller 1992; Villalba 1998), 90 (Dalakas 1993), and 140 (Van de Vlekkert 2010). The maximum sum score for one non‐standard strength scale was not given (Bunch 1980) and another quoted a maximum score of 160 (Coyle 2008). One study reported the mean manual muscle strength of all the muscles tested (Muscle Study Group 2011). One trial assessed muscle endurance using repetitive testing with a 1 kg weight on a range of muscle groups that were stated. The maximum score in this test was 56 but it was not stated how this score was obtained (Vencovsky 2000). One trial used myometry of nine muscle groups and hand grip measurements to assess muscle strength (Miller 2002).

The IMACS definition of improvement was used as an outcome in two studies (Coyle 2008; Muscle Study Group 2011), in a modified form in one case (Muscle Study Group 2011).

Two studies assessed time to relapse or treatment failure as an outcome (Muscle Study Group 2011; Van de Vlekkert 2010).

The number of participants in remission and time‐to‐remission was an outcome measure in one study, which compared dexamethasone therapy to prednisolone therapy (Van de Vlekkert 2010).

Cumulative steroid dose was an outcome measure in one 52‐week study comparing etanercept to placebo (Muscle Study Group 2011).

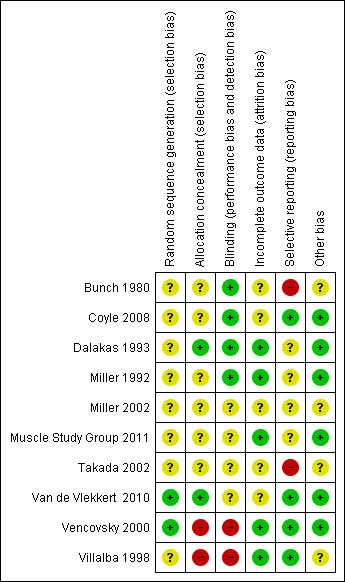

Risk of bias in included studies

Two trials were open label studies (Vencovsky 2000; Villalba 1998). One study had a randomised period followed by an open label cross‐over period which were not reported separately (Coyle 2008). One study included the SF‐36 in the protocol; however, in the abstract the trial authors did not report the result (Takada 2002). Due to limited information many of the 'Risk of bias' domains for the studies were reported as 'unclear' (see 'Risk of bias' tables in the section Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1).

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome measure

Change in function or disability scale at six months

IVIg

In Dalakas 1993 (15 participants), although an activities of daily living (ADL) score was assessed, the results in the two groups were not reported systematically and statistical comparison between the two groups was not reported. A significant improvement in the NSS (measured in 13 participants) was reported for IVIg (44.1 (SD 8.2) pretreatment and 51.4 (SD 6.0) at three months) but not for the placebo group (45.9 (SD 9.0) pretreatment and 45.7 (SD 11.3) at three months). The NSS is a score based on 20 activities, each scored from zero to three, where three signifies no impairment and zero severe impairment.

Azathioprine

One azathioprine trial did not have functional measures as an outcome (Bunch 1980). In another trial (28 participants), the abstract stated there was no significant difference between azathioprine and low dose methotrexate using timed walk as the outcome measure (data not available for analysis) (Miller 2002). In a trial which included participants on azathioprine and methotrexate, ADL score was used as an outcome but the results were only reported in participants who improved according to the trial definition (Villalba 1998).

Plasma exchange or apheresis

In one study the ADL scale measured after just one month of plasma exchange, leukopheresis or placebo was reported as not showing any significant change (Miller 1992, 39 participants, data not supplied).

Methotrexate

In Vencovsky 2000 (36 participants), significant improvement at 6 months in a composite score of muscle endurance and function (maximum score 56) was found in those taking methotrexate, from 24.1 (SD 14.9) to 40 (SD 9.3). Subgroup analysis showed that dermatomyositis and polymyositis participants showed similar changes in the composite score. There was also significant improvement over six months in the 'clinical assessment' score, a composite score of disease manifestations and function, from 12.0 (SD 6.7) to 5.6 (SD 4.6), and the global patient's assessment, the patient's subjective scoring of disability from 0 to 10, from 4.7 (SD 2.0) to 7.3 (SD 2.3).

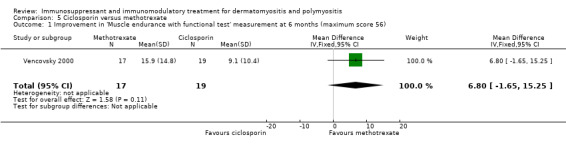

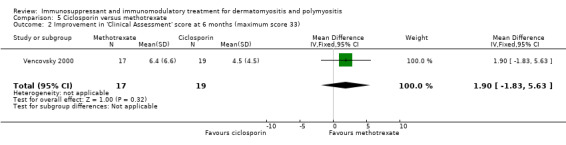

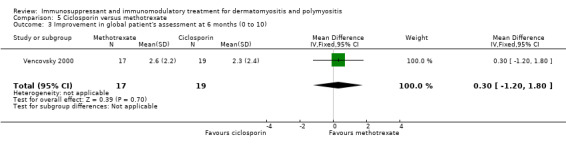

The comparative arm was those treated with ciclosporin, with no statistical difference noted at six months between methotrexate and ciclosporin for the composite score of muscle endurance and function (MD 6.80, 95% CI ‐1.65 to 15.25) (Analysis 5.1), the 'clinical assessment' score (MD 1.90, 95% CI ‐1.83 to 5.63) (Analysis 5.2) or the global patient's assessment (MD 0.30, 95% CI ‐1.20 to 1.80) (Analysis 5.3).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Ciclosporin versus methotrexate, Outcome 1 Improvement in 'Muscle endurance with functional test' measurement at 6 months (maximum score 56).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Ciclosporin versus methotrexate, Outcome 2 Improvement in 'Clinical Assessment' score at 6 months (maximum score 33).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Ciclosporin versus methotrexate, Outcome 3 Improvement in global patient's assessment at 6 months (0 to 10).

In Villalba 1998, which compared a combination of oral azathioprine and methotrexate to intravenous methotrexate, activities of daily living score was used as an outcome but the results were only reported in participants who improved according to the trial definition.

Ciclosporin

In Vencovsky 2000 (36 participants), significant improvement in a composite score of muscle endurance and function (maximum score was 56) was found in those taking ciclosporin, from 30.5 (SD 12.8) to 39.6 (SD 14.6) at six months. There was also significant improvement over six months in the 'clinical assessment' score, a composite score of disease manifestations and function, from 11.3 (SD 5.5) to 6.8 (SD 5.1), and the global patient's assessment, the patient's subjective scoring of disability from 0 to 10, from 4.5 (SD 2.0) to 6.8 (SD 2.4).

The comparative arm was those treated with methotrexate, with no statistical difference seen between methotrexate and ciclosporin at 6 months for the composite score of muscle endurance and function (MD 6.20, 95% CI ‐2.25 to 14.65) (Analysis 5.1), the 'clinical assessment' score (MD 1.90, 95% CI ‐1.83 to 5.630) (Analysis 5.2) or the global patient's assessment (MD 0.30, 95% CI ‐1.20 to 1.80) (Analysis 5.3).

Infliximab

Beyond the IMACS definitions of improvement, change in function or disability scale was not reported in this study (Coyle 2008).

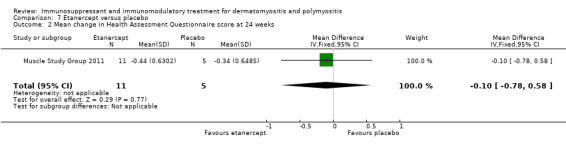

Etanercept

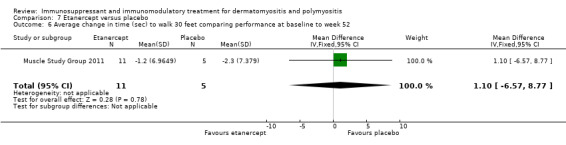

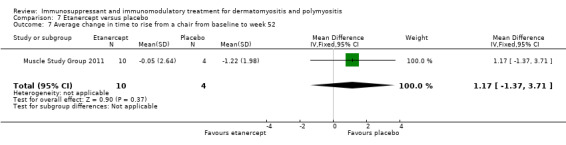

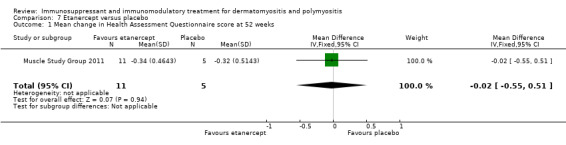

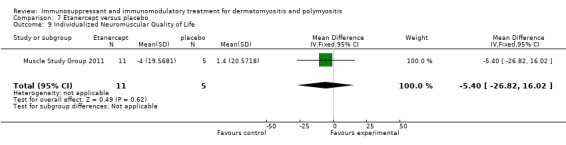

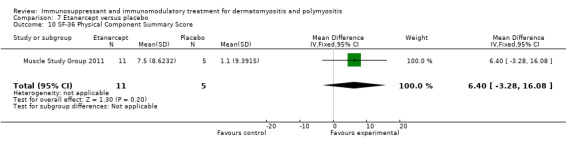

In a 52‐week pilot study of etanercept compared to placebo (16 participants), no statistically significant differences between treatment groups were found for time to walk 30 feet (s) (MD 1.10, 95% CI ‐6.57 to 8.77) (Analysis 7.6), time to rise from a chair (MD 1.17, 95% CI ‐1.37 to 3.71) (Analysis 7.7), HAQ (MD ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.51) (Analysis 7.1), individualized Neuromuscular Quality of Life (INQoL) (MD ‐5.40, 95% CI ‐14.19 to 3.39) (Analysis 7.9) or physical component summary of the SF‐36 at 52 weeks (MD 6.4, 95% CI 1.98 to 10.81) (Analysis 7.10) (Muscle Study Group 2011).

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 6 Average change in time (sec) to walk 30 feet comparing performance at baseline to week 52.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 7 Average change in time to rise from a chair from baseline to week 52 .

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 1 Mean change in Health Assessment Questionnaire score at 52 weeks.

7.9. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 9 Individualized Neuromuscular Quality of Life.

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 10 SF‐36 Physical Component Summary Score.

Eculizumab

In a pilot study of eculizumab compared to placebo, the SF‐36 was included in the study protocol but not reported in the published abstract (Takada 2002).

Dexamethasone

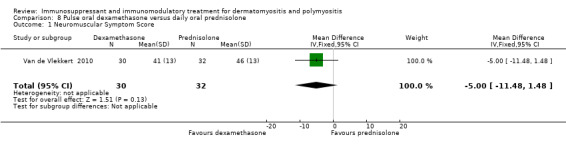

In a study comparing pulsed oral dexamethasone to oral daily prednisolone (62 participants), the NSS showed no significant differences between the two groups at 18 months (MD ‐5.00, 95% CI ‐11.48 to 1.48) (Analysis 8.1) (Van de Vlekkert 2010). We decided not to impute a correlation to calculate the SD of the difference between groups for change from baseline scores as the difference in the means at follow‐up was almost the same as at baseline. The physical function component of the SF‐36 was also reported as showing no significant differences between the two groups at 18 months (full data not supplied).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone, Outcome 1 Neuromuscular Symptom Score.

15% or greater improvement in muscle strength at six months

Only four trials measured muscle strength at six months or more, using MMT in three (Villalba 1998; Van de Vlekkert 2010; Muscle Study Group 2011) and limited to hand grip in another (Miller 2002); the proportion of participants having a 15% improvement in muscle strength was not an outcome in any of these studies. Only one study used the outcome 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength (Coyle 2008) but this study assessed it at 16 weeks rather than six months.

IVIg

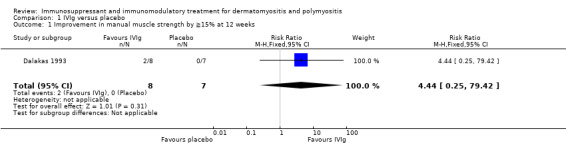

The only trial of IVIg (15 participants) measured muscle strength after just three months (Dalakas 1993). It found a statistically significant improvement in scores of muscle strength (maximum score 90) from 76.6 to 84.6 in the IVIg group but no change in the placebo group. The MD in improvement in muscle strength between the active and placebo group was 9.50 (95% CI 4.33 to 14.67). Using data derived from the figures in the paper, two of the eight participants treated with IVIg achieved ≥15% improvement in muscle strength at three months compared to none of the seven participants in the placebo group (RR 4.44, 95% CI 0.25 to 79.42) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 IVIg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement in manual muscle strength by ≧15% at 12 weeks.

Azathioprine

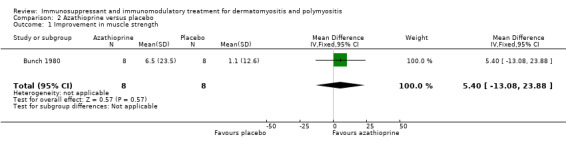

In a trial of 16 participants with polymyositis, after three months of treatment, muscle strength (maximum score 0, minimum ‐140) increased by 6.5 (SD 23.5) in the azathioprine group compared with 1.1 (SD 12.6) in the placebo group (Bunch 1980). The MD in improvement in muscle strength between the azathioprine group and the placebo group was 5.40 (95% CI ‐13.08 to 23.88) (Analysis 2.1). However, the difference was not statistically significant. In another trial of 28 participants, using change in hand held myometry readings as the primary outcome, the authors reported that azathioprine had equivalent efficacy to methotrexate (Miller 2002), although no specific data were given in the abstract. In a third trial, data on muscle strength were only given in those who improved according to the trial definition (Villalba 1998).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Azathioprine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement in muscle strength.

Plasma exchange or leukapheresis

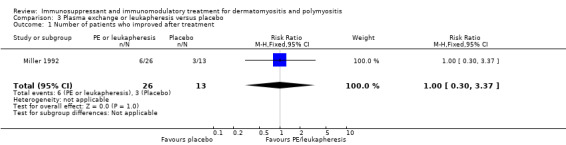

The trial of plasma exchange or leukapheresis versus placebo with 39 participants lasted only one month. During this time the RR of muscle strength improvement was not significantly different, being 1.0 (95% CI 0.3 to 3.37) in the active compared with the placebo treatment of the group (Miller 1992) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Plasma exchange or leukapheresis versus placebo, Outcome 1 Number of patients who improved after treatment.

Methotrexate

One trial (28 participants) the investigators reported that hand grip strength after one year did not improve any more with oral methotrexate than with azathioprine (Miller 2002). In a trial of oral methotrexate and azathioprine versus intravenous methotrexate including 30 participants (Villalba 1998), the authors reported no significant difference in muscle strength (maximum score 80) between the two groups at six months (P = 0.50, data not supplied).

Ciclosporin

Muscle strength was not tested for this intervention (Vencovsky 2000).

Infliximab

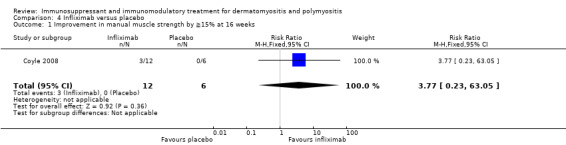

In a cross‐over study that was unblinded at 16 weeks (when participants on placebo were moved to the active arm), three of the 12 participants achieved a 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength after 16 weeks therapy with infliximab 5 mg/kg compared to none of the six participants during placebo therapy (RR 3.77, 95% CI 0.23 to 63.05) (Analysis 4.1). This difference was not statistically significant (Coyle 2008).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Infliximab versus placebo, Outcome 1 Improvement in manual muscle strength by ≧15% at 16 weeks.

Etanercept

In a 52‐week randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial involving 16 participants, there was no significant difference in the improvement in muscle strength as assessed by MMT (MD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.27) and quantitative myometry utilizing maximum voluntary isometric contraction testing (MVICT) (MD 0.67, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 2.78) between the treatment groups at 52 weeks. Our primary outcome, a 15% improvement in muscle strength, is a component of the IMACS DOI, but was not reported as individual item in this study (Muscle Study Group 2011).

Eculizumab

In a pilot study, MMT improved by an average of 6% in the actively treated arm (10 participants) after nine weeks of therapy compared to an average of 26% in those who received placebo (three participants) (Takada 2002). These data were from an abstract provided by the manufacturer. No raw data were available for analysis.

Dexamethasone

In an 18‐month placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomised trial (62 participants), the mean MMT scores (maximum 140) were 136 (SD 5) in the dexamethasone group and 135 (SD 6) in the prednisolone group at 18 months (Van de Vlekkert 2010).

Secondary outcome measures

Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement

Only two studies assessed this outcome (Coyle 2008; Muscle Study Group 2011).

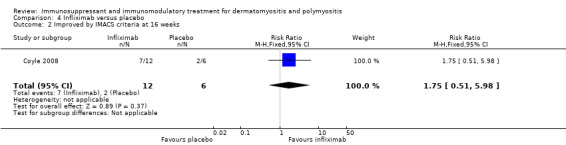

In one, which compared infliximab therapy to placebo, seven out of 12 participants improved by the IMACS definition after 16 weeks of therapy with infliximab compared to two out of six participants treated with placebo (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.51 to 5.98) (Analysis 4.2) (Coyle 2008).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Infliximab versus placebo, Outcome 2 Improved by IMACS criteria at 16 weeks.

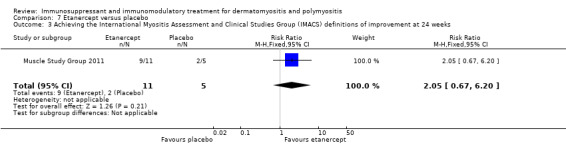

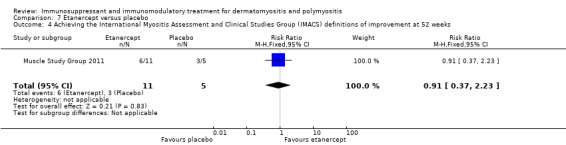

The second, comparing etanercept to placebo, used a modified form of the IMACs DOI in that the average percent of predicted normal MVICT score in addition to the MMT score was used for muscle strength testing (Muscle Study Group 2011). At 24 weeks nine of the 11 participants in the etanercept group achieved this definition of improvement compared to two of the five placebo‐treated participants (RR 2.05, 95% CI 0.67 to 6.20) (Analysis 7.3). At 52 weeks, six of the 11 participants in the etanercept group achieved this definition of improvement compared to three of the five placebo‐treated participants (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.23) (Analysis 7.4).There was no significant difference between the groups at either of these time points.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 3 Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement at 24 weeks.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 4 Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement at 52 weeks.

Number of relapses and time to relapse

Only two studies assessed time to relapse or treatment failure as an outcome (Muscle Study Group 2011; Van de Vlekkert 2010).

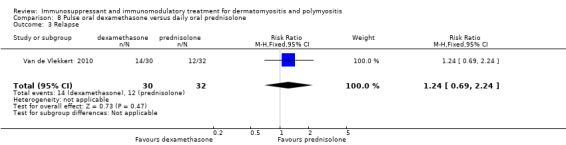

One study compared dexamethasone to prednisolone (Van de Vlekkert 2010). Relapse was defined as 1. a decrease in MRC sum score by four points or more (maximum score 140), or 2. a reduction in the Rankin score by one or more, or 3. a greater than two‐fold increase in serum creatine kinase associated with a reduction in strength or function. At 18 months, 14 of the 30 (47%) dexamethasone‐treated participants had relapsed compared to 12 of the 32 (38%) prednisolone‐treated participants (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.24) (Analysis 8.3). Median time to relapse was 44 weeks (standard error (SE) 4.7) in the dexamethasone group compare to 60 (SE 2.9) in the prednisolone treated group (log rank test P = 0.03).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone, Outcome 3 Relapse.

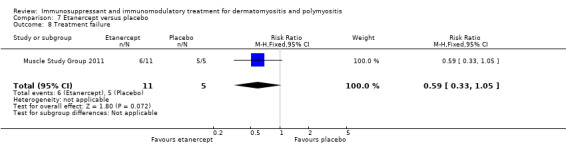

The other study compared etanercept to placebo (Muscle Study Group 2011). Treatment failure was said to have occurred if the study physicians felt it necessary to increase the participant's prednisolone and/or change to another agent, or if any one of the following five criteria were fulfilled:1. reduction in the physician global disease activity assessment visual analogue scale by 2 cm or more; 2. worsening of MMT composite score by 20% or more; 3. worsening of oropharyngeal muscle weakness sufficient to compromise nutrition or cause a risk of aspiration; 4. 20% worsening of forced vital capacity or diffusion capacity; 5. no improvement in muscle strength after 12 weeks.

Six of 11 participants in the etanercept arm were treatment failures. All five participants receiving placebo were treatment failures (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.05) (Analysis 7.8). Median time to treatment failure was 148 days in the placebo arm versus 358 days in the etanercept arm (P = 0.0002).

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 8 Treatment failure.

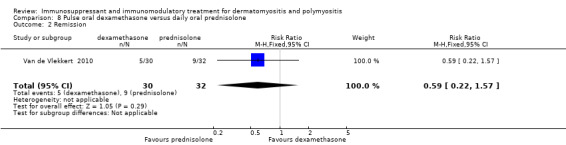

Number of participants in remission, and time‐to‐remission after at least six months

This was an outcome measure in one study, which compared dexamethasone therapy to prednisolone therapy (Van de Vlekkert 2010), and defined remission as a Rankin score of zero or one. At 18 months, five of 30 (17%) dexamethasone‐treated participants and nine of 32 (28%) prednisolone‐treated participants were in remission (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.57) (Analysis 8.2). Mean time to remission was 58.8 (SE 5.1) weeks in the dexamethasone‐treated group and 58.8 (SE 4.6) weeks in the prednisolone‐treated group (log‐rank test P = 0.73).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone, Outcome 2 Remission.

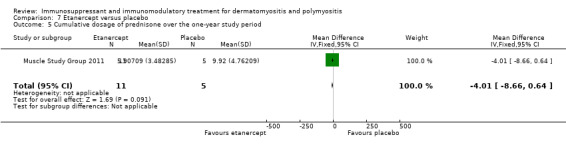

Cumulative corticosteroid dose after at least six months

This was an outcome measure in one study comparing etanercept to placebo (Muscle Study Group 2011), although the data were not presented in the paper, they were published on the clinicaltrials.gov website. The mean (SD) cumulative prednisolone dose in g over the one year study period was 5.90709 (3.48285) in the etanercept group and 9.91765 (4.76209) in the placebo group (MD ‐4.01, 95% CI ‐8.66 to 0.64) (Analysis 7.5, no significant difference). The median prednisolone dose from weeks 25 to 52 was significantly higher in the placebo group (median 29.2 mg/day, range 9.9 to 62.6 mg/day) than the etanercept group (median 1.2 mg/day, range 0.0 to 31.1 mg/day) (P = 0.02).

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Etanercept versus placebo, Outcome 5 Cumulative dosage of prednisone over the one‐year study period .

Serious adverse effects

IVIg

In the study of IVIg for dermatomyositis no serious adverse events were reported (Dalakas 1993). In two participants a severe headache occurred with each infusion, requiring treatment with narcotics.

Azathioprine

In the study of azathioprine in polymyositis (Bunch 1980) only 16 of 23 participants completed the study. The other participants failed to complete the study either because they were lost to follow‐up (three), failed to respond to treatment (one on placebo) or experienced adverse effects (three). Two of the three subjects withdrawn from the study due to adverse effects were on azathioprine with one having severe nausea and vomiting and the other developing pneumonitis after one month of treatment. One subject on placebo developed acute diverticulitis and needed surgery. A further subject on azathioprine developed significant leukopenia at the end of the study but this was judged to be unrelated to the study as she was later found to have cyclic neutropenia. Azathioprine was also part of the oral regime in another trial (Villalba 1998) (see under methotrexate).

Plasma exchange or apheresis

Adverse events on apheresis were common in the study comparing plasma exchange, leukapheresis and sham apheresis (Miller 1992). Nine out of 39 participants required placement of a central venous catheter to maintain venous access. Three participants had major vasovagal episodes. Two participants had clinically important citrate reactions; and one participant receiving sham treatments required red cell transfusion for an apheresis‐related decline in haemoglobin. In the plasma exchange group, one participant developed acute transient respiratory distress and one developed herpes zoster.

Methotrexate

Four out of 17 participants receiving oral methotrexate withdrew prematurely from one trial (Vencovsky 2000) because of pancytopenia, gut perforation, acute alveolitis or withdrawal of consent after suffering petechiae. Seven participants had minor adverse events including hypertension and rash which were not sufficient to stop their treatment. Assessment of the adverse effects of methotrexate in another trial (Villalba 1998) is complicated by the fact that oral methotrexate was given in combination with azathioprine and by the cross‐over study design. A total of 28 participants had oral combination therapy (13 of whom had crossed over from the intravenous methotrexate arm). Of these, six had their oral treatment curtailed due to gastrointestinal side effects, and there was one fatality due to Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. A total of 26 participants had intravenous methotrexate (11 having had prior oral treatment) of whom four had adverse events including gastrointestinal intolerance, abscesses, pseudomonas skin infection and legionella pneumonia. Liver enzyme elevations, infections and gastrointestinal intolerance were common side effects with both oral and intravenous methotrexate (Villalba 1998).

Ciclosporin

In one study two out of 19 subjects taking ciclosporin were withdrawn prematurely due to side effects which were creatinine elevation (one participant) and pneumonia (one participant); a third participant was withdrawn due to the adverse event of non‐compliance (Vencovsky 2000). A further five had minor side effects including hypertension (three participants), bronchitis (one) and bronchopneumonia (one), that did not necessitate withdrawal from the trial (Vencovsky 2000).

Infliximab

Two undisclosed severe adverse events, reported as unrelated to infliximab, occurred in this study. In addition, one participant experienced an infusion reaction and an undisclosed number of mild adverse events occurred (Coyle 2008).

Etanercept

In a small study of 16 participants with dermatomyositis, six severe adverse events were reported in the etanercept group and three in the placebo group (Muscle Study Group 2011). In the etanercept group, the six serious adverse events occurred in three participants, comprising pregnancy and miscarriage in a partner; hospitalization for a urinary tract infection and fever of unknown origin; postherpetic neuralgia and two admissions for psychosis. Two participants in the etanercept group developed positive antinuclear antibodies compared to one of the placebo group (Muscle Study Group 2011). Five participants in the etanercept‐treated group compared to one in the placebo group had worsening of their skin disease.

Eculizumab

In a pilot study of eculizumab compared to placebo the numbers of adverse events was not significantly different between the two groups. The nature of these adverse events was not disclosed. There were no serious adverse events in either group (Takada 2002).

Because the eight trials used different interventions and variable outcome measures, no meta‐analysis was possible.

Dexamethasone

In a study comparing pulsed oral dexamethasone to oral daily prednisolone, there was a high rate of discontinuation of both treatments: 21 out of 30 in the dexamethasone group and 17 out of 32 in the prednisolone group (Van de Vlekkert 2010). The main reasons for discontinuation were relapse at less than six months, no improvement and serious side effects. The dexamethasone‐treated participants had fewer side effects in total, with 22 (79%) suffering any side effect in the dexamethasone group compared to 29 (97%) in the prednisolone‐treated group. The prednisolone group had a greater incidence of mood changes, diabetes mellitus, mean weight gain of more than 5 kg, cushingoid features, skin thinning, gastric symptoms, impaired wound healing, hair loss, infections, acne, hirsutism, hypertension, cataract formation and striae. One adverse event occurred with greater frequency in the dexamethasone group, renal crisis, which occurred in two participants, both in the dexamethasone group.

Subgroup analyses

Although we intended to analyse subgroups, this proved impossible. All the studies examined adult participants, therefore the effect of immunosuppressants on participants under the age of 18 could not be assessed. Participants with and without autoantibodies were not separated into different subgroups when analysing response to treatment. Reason for failed response to corticosteroids was rarely reported and subsequent analyses did not separate participants with inadequate response to corticosteroids versus those who had unacceptable side effects.

Comparison with excluded studies as sensitivity analysis

In contrast to the selected studies, the excluded studies predominantly reported positive results.

Bunch 1981 reported one‐ and three‐year follow‐up data from the 1980 RCT comparing azathioprine with placebo discussed above (Bunch 1980). Muscle strength was not reported but the improvement in functional disability (graded from one to six, one being normal, six unable to walk without assistance) in the azathioprine group (from 4.5 (SD 0.9) to 2.1 (SD 0.6)) was greater than that achieved in the prednisolone only group (from 4 (SD 0.8) to 3 (SD 0.6)). Mean change was 2.4 (SD 1.1) and 1 (SD 0.6) respectively.

Chung and colleagues reported a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial of creatine supplements in participants with established dermatomyositis or polymyositis undergoing a home exercise programme (Chung 2007). There was a significantly greater reduction in the primary outcome, the percentage change in the aggregate functional performance time, in the creatine arm (P = 0.029) at six months (Chung 2007). The aggregate functional performance time consisted of four timed functional activities: a 50 foot timed walk; the 'get up and go test'; a 19‐step stair ascent test; and a 19‐step stair descent test. Muscle strength was reported for individual muscle groups and only showed a significant difference between the two groups at six months, favouring the creatine‐treated arm in four of the ten muscle groups assessed.

Fries 1973 reported a randomised open‐label study comparing 16 weeks of cyclophosphamide therapy with high dose oral prednisolone. The cyclophosphamide dose was titrated to maintain a white cell count of 3500 to 4000 cells/cu mm, this group received no prednisolone. The actual cyclophosphamide dose given averaged 125 mg daily. Where initial white counts permitted, participants in the cyclophosphamide group also received an initial infusion of nitrogen mustard at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg. The prednisolone group were commenced on a dose of 1 mg/kg or greater. Only eight polymyositis subjects were included, with five receiving initial cyclophosphamide therapy and three receiving prednisolone therapy. The trial authors stated that the muscle enzyme and sedimentation rates normalised in the prednisolone group but not the cyclophosphamide group, with a difference that was significant at the five per cent level. Although not stated, as the initial treatment period was 16 weeks it is likely that these data refer to this time period.

Donov 1995 performed a trial of plasmapheresis in 30 children with juvenile dermatomyositis. There was no evidence of randomisation or blinding in the abstract. Four participants received sham plasmapheresis and 26 active therapy. The therapeutic regime consisted of plasmapheresis with a subsequent methylprednisolone dose one to three times a week. Therapy duration varied fom one to 10 weeks. No improvement was seen in the sham plasmapheresis subjects but complete remission seen in 24 participants in the active arm with 'considerably decreased' disease activity in the other two cases. No definitions of complete remission or objective measures of disease activity were given.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the lack of high quality RCTs that assess the efficacy and toxicity of immunosuppressants in inflammatory myositis. Ten trials were included in the review with only one agent, IVIg demonstrating statistically significant superior efficacy against control, and a second agent, etanercept showing a possible steroid‐sparing effect. Therefore, we have to conclude that there is insufficient evidence from available RCTs to confirm the value of immunosuppressants in inflammatory myositis. For 'Summary of findings' tables see Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; and Table 12.

3. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) versus placebo for dermatomyositis.

| IVIg versus placebo for dermatomyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: IVIg versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | IVIg | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data available, only one study of three months duration |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Although an activities of daily living score was assessed, the results in the 2 groups were not reported systematically and statistical comparison between the 2 groups was not reported. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IVIg: intravenous immunoglobilin | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

4. Azathioprine versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Azathioprine versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: azathioprine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Azathioprine | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months. ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data as study only lasted three months |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

5. Azathioprine plus prednisolone versus methotrexate plus prednisolone.

| Azathioprine plus prednisolone compared with methotrexate plus prednisolone for polymyositis or dermatomyositis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis Settings: Intervention: prednisolone plus either azathioprine 2.5 mg per kg daily Comparison: prednisolone plus methotrexate 15 mg weekly for 1 year | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Low dose methotrexate | Azathioprine | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least 6 months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | Hand‐held myometry used but data not provided |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement at 52 weeks ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

|

Change in function or disability scale at 6 months ‐ not reported |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | Timed walk was measured but data not available |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

6. Plasma exchange or leukapheresis versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Plasma exchange or leukapheresis versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: plasma exchange or leukapheresis versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Plasma exchange or leukapheresis | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | One study of only one month duration. |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months1 ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | One study of only 1 month duration. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

7. Oral methotrexate with azathioprine versus intravenous methotrexate with leucovorin rescue for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Oral methotrexate with azathioprine versus intravenous methotrexate with leucovorin rescue for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: oral methotrexate with azathioprine Comparison: intravenous methotrexate with leucovorin rescue | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Intravenous methotrexate with leucovorin rescue | Oral methotrexate with azathioprine | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | One study of 1 month's duration |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data available. Activities of daily living score was measured but the results were only presented in participants who improved according to the trial definition |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

8. Methotrexate versus ciclosporin for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Methotrexate versus ciclosporin for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: methotrexate Comparison: ciclosporin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Ciclosporin | Methotrexate | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Muscle strength data not available. |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not an outcome in this study |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Function measured but not reported separately from composite score of 'muscle endurance with function'. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

9. Infliximab versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Infliximab versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: infliximab versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Infliximab | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No data |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement Follow‐up: 16 weeks | 333 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (77 to 1000) | RR 3.77 (0.23 to 63.05) | 18 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | ‐ |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Extremely small numbers and includes open follow‐up.

10. Etanercept versus placebo.

| Etanercept versus placebo | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis, either 1. treatment naïve (prednisolone < 2 months) or 2. refractory to therapy with prednisolone > 2 months and either methotrexate (stable dose ≥1 month or more) or intravenous immunoglobulin ≥ 3 months Settings: Intervention: etanercept versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Etanercept | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least 6 months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not an outcome in this study |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement at 24 weeks | 400 per 1000 | 820 per 1000 (268 to 1000) | RR 2.05 (0.67 to 6.2) | 16 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ‐ |

| Change in function or disability score Various measures Follow‐up: 24 weeks | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 16 (1 study) | See comment | No significant difference between control and etanercept in any measure of function or disability (final values) (see text) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Pilot study with small sample size of 16 participants. Wide 95% CI of RR (0.75 to 2.45).

11. Eculizumab versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Eculizumab versus placebo for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis Settings: Intervention: eculizumab versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Eculizumab | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Single study of only 9 weeks' duration. |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not an outcome in this study |

| Change in function or disability scale at six months ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Single study of only 9 weeks' duration. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

12. Pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone for dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

| Pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone for dermatomyositis and polymyositis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis, non‐specific myositis, myositis with a co‐existing connective tissue disease or with cancer within 2 years before onset of myositis, disease of less than one year duration. On no more than 20 mg prednisolone and no other immunosuppressant or immunomodulatory therapy Settings: Intervention: pulse oral dexamethasone versus daily oral prednisolone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Daily oral prednisolone | Pulse oral dexamethasone | |||||

| 15% or greater improvement in muscle strength compared with baseline after at least 6 months ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not an outcome in this study |

| Achieving the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) definitions of improvement at 52 weeks ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Not an outcome in this study |

|

Change in function or disability scale

Neuromuscular Symptom Score Scale from: 0 to 60 Follow‐up: 18 months |

The mean function or disability scale score in the control group was 461 | The mean function or disability scale score in the intervention groups was 5 lower (11.48 lower to 1.48 higher) | ‐ | 62 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean final NSS in placebo group.

2 Only one study of 62 participants with 61% discontinuing the study early.

This conclusion appears to contradict the experience of many clinicians. However, the lack of good evidence is not the same as no evidence. The lack of RCTs in inflammatory myositis is typical of the problem faced by evidence‐based medicine. Conducting high quality RCTs in rare diseases is extremely difficult. Yet without data from high quality RCTs, it is impossible for clinicians to assess the benefit/risk ratio of immunosuppressants in myositis accurately. The trial of plasma exchange and leukapheresis is a good example of where a treatment is ineffective but has significant side effects. Indeed, this review found that immunosuppressants are associated with significant side effects. Clearly, it is important for physicians and participants to appreciate the precise benefit and risk of immunosuppressants in inflammatory myositis. Participants with inflammatory myositis are managed by different specialists: neurologists, rheumatologists, dermatologists or general physicians. Since high quality RCTs require sufficient sample sizes to deliver the necessary statistical power, individual clinicians rarely have a sufficient number of potential participants under their care to conduct trials. Therefore, multicentre trials with collaboration between all these specialists are the only means to study this rare disease. In recent years new collaborative efforts such as the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS), the European Myositis Network (EUMYONET) and the United Kingdom Myositis Network (UK MYONET) have formed to foster such collaboration.

Another major obstacle in evidence‐based medicine in inflammatory myositis has been the lack of international consensus on outcome measures and how data should be presented in publications. However, in recent years the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) has developed international multidisciplinary outcome measures (Isenberg 2004; Oddis 2005; Rider 2004). These include the 'definitions of improvement' which comprise six core set measures among five domains (Oddis 2005; Rider 2004). These core set measures are: the physician global disease activity, parent/patient global disease activity, muscle strength (MMT), physical function assessment, laboratory assessment and extramuscular disease complications. Improvement is defined as occurring if three of any six core set measures improve by 20%, with no more than two worsening by 25% (measures that worsen cannot include manual muscle strength).