Abstract

Background

The treatment of distal (below the knee) deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is not clearly established. Distal DVT can either be treated with anticoagulation, or monitored with close follow‐up to detect progression to the proximal veins (above the knee), which requires anticoagulation. Proponents of this monitoring strategy base their decision to withhold anticoagulation on the fact that progression is rare and most people can be spared from potential bleeding and other adverse effects of anticoagulation.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different treatment interventions for people with distal (below the knee) deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Search methods

The Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL databases and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov trials registers to 12 February 2019. We also undertook reference checking to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for the treatment of distal DVT.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials and extracted data. We resolved disagreements by discussion. Primary outcomes of interest were recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), DVT and major bleeding and follow up ranged from three months to two years. We performed fixed‐effect model meta‐analyses with risk ratio (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed the certainty of the evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We identified eight RCTs reporting on 1239 participants. Five trials randomised participants to anticoagulation for up to three months versus no anticoagulation. Three trials compared anticoagulation treatment for different time periods.

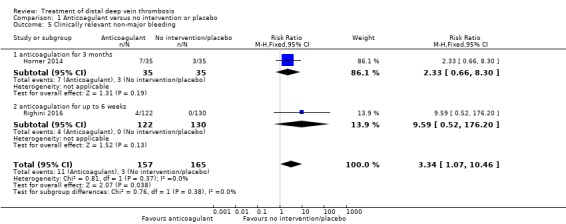

Anticoagulant compared to no intervention or placebo for distal DVT treatment

Anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) reduced the risk of recurrent VTE during follow‐up compared with participants receiving no anticoagulation (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.77; 5 studies, 496 participants; I2 = 3%; high‐certainty evidence), and reduced the risk of recurrence of DVT (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.67; 5 studies, 496 participants; I2 = 0%; high‐certainty evidence). There was no clear effect on risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.18 to 3.59; 4 studies, 480 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). There was little to no difference in major bleeding with anticoagulation compared to placebo (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.13 to 4.62; 4 studies, 480 participants; I2 = 26%; low‐certainty evidence). There was an increase in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding events in the group treated with anticoagulants (RR 3.34, 95% CI 1.07 to 10.46; 2 studies, 322 participants; I2 = 0%; high‐certainty evidence). There was one death, not related to PE or major bleeding, in the anticoagulation group.

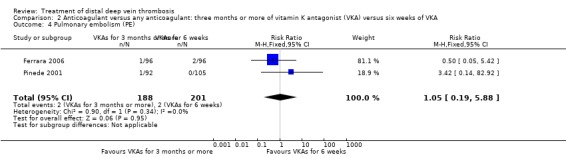

Anticoagulation for three months or more compared to anticoagulation for six weeks for distal DVT treatment

Three RCTs of 736 participants compared three or more months of anticoagulation with six weeks of anticoagulation. Anticoagulation with a VKA for three months or more reduced the incidence of recurrent VTE to 5.8% compared with 13.9% in participants treated for six weeks (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.68; 3 studies, 736 participants; I2 = 50%; high‐certainty evidence). The risk for recurrence of DVT was also reduced (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.64; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 48%; high‐certainty evidence), but there was probably little or no difference in PE (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.19 to 5.88; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). There was no clear difference in major bleeding events (RR 3.42, 95% CI 0.36 to 32.35; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) or clinically relevant non‐major bleeding events (RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.90 to 3.42; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 1%; low‐certainty evidence) between three months or more of treatment and six weeks of treatment. There were no reports for overall mortality or PE and major bleeding‐related deaths.

Authors' conclusions

Our review found a benefit for people with distal DVT treated with anticoagulation therapy using VKA with little or no difference in major bleeding events although there was an increase in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding when compared to no intervention or placebo. The small number of participants in this meta‐analysis and strength of evidence prompts a call for more research regarding the treatment of distal DVT. RCTs comparing different treatments and different treatment periods with placebo or compression therapy, are required.

Plain language summary

Treatment of below‐the‐knee deep vein thrombosis

Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a condition in which a blood clot forms in a vein, most commonly in the deep veins of the legs or pelvis. This is known as deep vein thrombosis, or DVT. The blood clot can dislodge and travel in the blood, particularly to the pulmonary arteries. This is known as pulmonary embolism, or PE. The term VTE includes both DVT and PE.

Distal DVT (also known as isolated distal DVT, calf DVT or below‐the‐knee DVT) occurs when the blood clot develops inside the leg veins (below the knee). The extension of the clot in proximal (above the knee) veins and the migration of a clot to the lungs (PE) are the most common complications. The best treatment of distal DVT is not clearly established. Distal DVT can either be treated with anticoagulation (medicines that help prevent blood clots), with or without additional use of compression stockings, or no medications can be given, and monitoring with repeat ultrasounds can be performed to see if the clots grow, which requires anticoagulation. The main side effect of anticoagulation medication is the increased risk of bleeding.

Study characteristics and key results

We identified eight randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) reporting on 1239 participants. Five of these trials randomised participants to anticoagulation for up to three months compared with no anticoagulation. Three trials compared anticoagulation treatment for different time periods.

Our review demonstrated that in participants with distal DVT compared with no anticoagulation or placebo (pretend treatment), anticoagulation reduced the risk of recurrence of VTE. There were similar results for the recurrence of DVT, while there was no clear effect on risk of PE. This benefit was seen at the expense of an increase in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, but not major bleeding.

In a direct comparison of treatment duration, anticoagulation for three months or more was superior to a shorter course lasting up to six weeks, showing a reduced risk of recurrence of VTE and DVT with no clear difference in major bleeding and clinically relevant non‐major bleeding.

Reliability of the evidence

For the comparison anticoagulation versus no anticoagulation or placebo, the reliability of the evidence was high for recurrence of VTE, DVT, and clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, and low for PE and major bleeding. For the comparison anticoagulation for three months or more versus six weeks, the reliability of the evidence was high for recurrence of VTE and DVT; and low for PE, major bleeding and clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, The reliability of the evidence was downgraded because of variation (or imprecision) of the results due to small numbers of events.

Conclusion

Our review found a benefit for people with distal DVT treated with anticoagulation therapy with little or no clear difference in major bleeding events, although there was an increase in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding when compared with no treatment or placebo. The small number of participants in this meta‐analysis and strength of evidence suggests more research regarding the treatment of distal DVT is needed. Randomised controlled trials comparing different treatments and different treatment periods with placebo or compression therapy are required.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the obstruction of any deep vein by a blood clot or the embolism of pulmonary arteries after thrombus migration. The pathophysiology of venous thromboses are described by Virchow's Triad as hypercoagulability, haemodynamic changes (as stasis or turbulence) and endothelial injury. VTE is comprised of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), or both, and can occur spontaneously. The incidence of VTE in mostly white populations is between 100 per 100,000 person‐years and 200 per 100,000 person‐years (Heit 2015; White 2003). Of these, it is estimated that 45 per 100,000 person‐years to 117 per 100,000 person‐years are due to DVT (without PE) and 29 per 100,000 person‐years to 78 per 100,000 person‐years are due to PE (with or without DVT) (Heit 2015). After anticoagulant discontinuation, recurrent VTE occurs in approximately 7.4% of people in one year, rising to 30.4% of people in 10 years (Cushman 2007; Heit 2015; White 2003). There are many risk factors for VTE, including periods of inactivity, dehydration, hospitalisation, trauma, surgery, clotting disorders and previous thrombosis, superficial vein thrombosis, pregnancy, oral combined hormonal contraceptives, malignancy, obesity, smoking and advancing age (Anderson 2003; NICE 2018).

DVT describes the formation of thrombus in the deep veins in the legs, and can be divided into three types:

distal DVT (also known as isolated distal DVT, calf DVT or below the knee DVT), involving the infrapopliteal venous system;

femoropopliteal DVT, involving the proximal leg veins up to the inguinal ligament; and

iliofemoral DVT involving proximal DVT that extends above the inguinal ligament.

DVT is also sometimes categorised as provoked or unprovoked, that is, the DVT is caused by a known risk factor or not. Risk factors may be transient or persistent and the presence of risk factors and the type of risk factor influence the risk of recurrent VTE.

DVT can also occur in the upper extremities (arms) but this is not the focus of this Cochrane Review and has been addressed in Feinberg 2017.

Clinical presentation of DVT of the lower limbs may be associated with localised pain, swelling and erythema, and the later occurrence of post‐thrombotic syndrome (PTS) (leg pain, tenderness, leg fatigue, persistent swelling, erythema, pigmentation or ulceration). Distal DVT is a common form of DVT but the precise incidence of distal DVT is unknown. It is estimated that it affects 0.1% of people per year (48 per 100,000) and represents about one‐third to one‐half of lower extremity DVT (Kesieme 2011). Distal DVT, particularly if left untreated, may recur or extend to the proximal veins, so increasing the risk for complications, including PE and PTS. Although rare, symptomatic PE can present as a complication of isolated distal DVT, with shortness of breath, pain on inspiration, tachycardia and right heart overload. If untreated, it can lead to circulatory collapse and death. After anticoagulation treatment there is a lower annualised incidence of VTE recurrence in people with isolated DVT compared with people with proximal DVT, but a similar incidence of PE recurrence (Galanaud 2014).

The standard treatment for VTE is anticoagulation therapy (Kearon 2016), which aims to interrupt the extension of the thrombus in proximal veins and reduce the risk for VTE recurrence (as DVT or PE). Anticoagulant drugs have the risk of bleeding as a complication of the treatment. The severity of bleeding is a reason for discontinuing the treatment and major bleeding episodes mostly require transfusion, endoscopic or angiographic intervention or surgery. Some major bleedings are fatal, and people with comorbidities are more prone to bleedings and most often interrupt the treatment (Di Nisio 2016).

Description of the intervention

Clinical guidelines provide recommendations for treatment of DVT and VTE in different settings (Kearon 2016; NICE 2012; Streiff 2016). In general, anticoagulation is the recommended treatment of choice. The recommended initial treatment is with either a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC; with or without initial parenteral anticoagulation as indicated) or a parenteral anticoagulant in conjunction with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA). Long‐term therapy (usually anticoagulation for a minimum of three months) is indicated to treat acute VTE. Then extended‐duration anticoagulation, often referred to as 'indefinite therapy' when no anticipated stop date exists, may be used among select patients for the secondary prevention of thrombosis. In some cases of VTE associated with an increased risk for morbidity or mortality, initial thrombolysis may be appropriate (Kearon 2016; NICE 2012; Watson 2016). Evidence and guidance do not recommend using compression stockings routinely for the prevention of PTS (Kahn 2014; Kearon 2016). In people with VTE in whom anticoagulation is inappropriate, or in those who develop further pulmonary emboli despite adequate anticoagulation, temporary intravenous catheter filters can be placed to prevent further embolisation (NICE 2012).

The best treatment for people with distal DVT is not clearly established. Distal DVT can be treated with anticoagulation, for example, a form of heparin or fondaparinux transitioned to a VKA, a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or a DOAC. Distal DVT can also be managed expectantly with close follow‐up to detect progression to the proximal veins requiring anticoagulation. Proponents of this strategy base their decision to withhold anticoagulation on the fact that progression is rare and most people can be spared from potential bleeding and other adverse effects of anticoagulation.

To date, only a limited number of studies have reported on treatment of distal DVT using VKAs (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001), and some on LMWHs such as nadroparin (Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010). The CACTUS trial reported that anticoagulation with "nadroparin was not superior to placebo in reducing the risk of proximal extension or venous thromboembolic events in low‐risk outpatients with symptomatic calf DVT, but did increase the risk of bleeding" (Righini 2016). However, in one systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies, Lim 2017 concluded that in a low‐risk population, the risk for recurrence of DVT or the extension of the distal DVT in a proximal deep vein was higher when a no treatment approach was performed compared with treatment with an anticoagulant drug.

How the intervention might work

Compression may improve venous function by preventing venous stasis, which in turn may prevent progression of the distal DVT to the proximal veins.

Where no treatment is given, close observation with ultrasound is required for two weeks (Fleck 2017; Kearon 2012; Kearon 2016), so anticoagulation can be started selectively in those few patients with documented proximal progression of the thrombus.

Treatment with any anticoagulation limits the extension of the thrombus and decreases the risk for recurrence and complications. The anticoagulant effect of VKAs is achieved by decreasing the production of coagulation factors from the liver. LMWHs indirectly inhibit factors IIa and Xa; and synthetic pentasaccharides (including fondaparinux) are selective indirect factor Xa inhibitors. Among the new oral anticoagulants, dabigatran is a selective direct thrombin inhibitor, while rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban are selective factor Xa inhibitors (Kesieme 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Distal DVT represents a separate issue from proximal DVT for several reasons, including the initial clinical decision to observe or treat; and if anticoagulation is given, there is debate on the appropriate treatment length. To date, existing Cochrane Reviews on this topic have not provided subgroup analyses to deal with these issues, as included RCTs either did not involve participants with isolated distal DVTs, or did not report distal DVT separately from proximal DVT (Brandao 2017; Middeldorp 2014; Robertson 2015; Robertson 2017). Therefore, it is currently unclear which treatment for distal DVT is most effective and safe. Due to ongoing controversy, some people may be denied anticoagulation based on relatively small and possibly underpowered trials. There is a need for a standardised treatment approach for distal DVT in daily clinical practice. We aimed to identify existing RCT evidence for treatment of distal DVT and to determine the most effective and safe treatment options. Our review first determined if there is a need to anticoagulate; and second, what is the most appropriate length of anticoagulation.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different treatment interventions for people with distal (below the knee) deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised control trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years or older) with distal (also known as below the knee or calf) DVT. Diagnosis of a first or recurrent DVT was made using venography or ultrasonography.

Types of interventions

We included studies which use anticoagulants (including LMWHs, DOACs, VKAs, synthetic pentasaccharides), or compression therapy for the treatment of distal DVT, of any dose or treatment duration. We planned to include the following comparisons:

any anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo;

any anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant;

any compression therapy versus no intervention or placebo;

any anticoagulant versus any compression therapy;

compression therapy versus no compression therapy.

No intervention or placebo may have included serial ultrasound observations.

We listed all treatment groups in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were measured at the end of the intervention and the follow‐up period, as reported by the individual studies, usually between three and six months from recruitment. We include long‐term results (one to two years), where available.

Primary outcomes

Recurrence of VTE: defined as DVT recurrence in the calf veins, or progression of DVT to proximal veins (e.g. popliteal or femoral vein) or PE, provided that these were objectively diagnosed with venography or ultrasonography for DVT and pulmonary angiography, computed tomography or V/Q scan for PE. We considered any episode of DVT after the first episode, including propagation of distal DVT, as recurrence.

Major bleeding: defined as clinically overt and associated with a fall in haemoglobin level of 20 g/L or more; transfusion of two or more units of red cells; retroperitoneal, intracranial, occurred in a critical site, or contributed to death.

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence of DVT, which included DVT recurrence in the calf veins, progression of DVT to proximal veins (e.g. popliteal or femoral vein); objectively diagnosed with venography or ultrasonography. We considered any episode of DVT after the first episode, including propagation of distal DVT, as recurrence.

PE: objectively diagnosed with pulmonary angiography, computed tomography or V/Q scan.

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, defined as overt bleeding not meeting the criteria for major bleeding but associated with medical intervention, unscheduled contact with a physician, interruption or discontinuation of study treatment, or associated with any other discomfort such as pain or impairment of activities of daily life.

Overall mortality.

Mortality related to PE or major bleeding.

Post‐thrombotic syndrome (PTS).

Resolution of symptoms.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist conducted systematic searches of the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web searched from inception to 12 February 2019);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO 2019, Issue 1);

MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE) (1946 onwards) (searched from 1 January 2017 to 12 February 2019);

Embase Ovid (from 1974 onwards) (searched from 1 January 2017 to 12 February 2019);

CINAHL EBSCO (from 1982 onwards) (searched from 1 January 2017 to 12 February 2019).

The Information Specialist modelled search strategies for other databases on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. Where appropriate, they were combined with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6, Lefebvre 2011). Search strategies for major databases are provided in Appendix 1.

The Information Specialist searched the following trials registries on 12 February 2019:

the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (who.int/trialsearch);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (GIK, SS) independently screened titles and abstracts of retrieved studies for relevance. We retrieved full‐text articles of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors (GIK, SS) independently reviewed each full‐text article for eligibility. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author (SKK). We illustrated the study selection process in a PRISMA diagram (Liberati 2009). We listed all articles excluded after full‐text assessment in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and provided the reasons for their exclusion. Where studies had multiple publications, we collated the reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest for the review, and such studies had a single identifier with multiple references.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (GIK, SS) independently extracted relevant data on primary and secondary outcomes and transfer the information to data collection sheets. We resolve discrepancies by consulting with a third review author (SKK) and transferred additional general information on each included study, including numbers, gender, mean age of participants, and types of interventions, to the Characteristics of included studies table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GIK, SS) independently assessed each included study for risk of bias according to the following criteria: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias) and other bias, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We judged all included studies as having low, high or unclear risk of bias based on these criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author (SKK).

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5 to calculate the measures of treatment effect (Review Manager 2014). We assessed dichotomous data by calculating risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed continuous data by calculating the mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) with corresponding 95% CI. We used standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs to combine outcomes from trials that used different scales.

Unit of analysis issues

Each individual participant was the unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We recorded missing and unclear data. If possible, we performed all analyses using an intention‐to‐treat approach, that is, we analysed all participants and their outcomes within the groups to which they were allocated, regardless of whether they received the intervention or were assessed for the outcome. If necessary, we contacted study authors to request missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed interstudy heterogeneity using a forest plot. We calculated Chi2 and I2 statistics to measure the amount of heterogeneity. I2 values less than 50% indicate low heterogeneity, I2 values between 50% and 75% indicate moderate heterogeneity, and I2 values greater than 75% indicate significant heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). We performed subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess reporting bias by using funnel plots, when a meta‐analysis included more than 10 studies (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis when we observed no or low heterogeneity. In cases of moderate/significant heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we planned to use a random‐effects model. If we had identified substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity across included trials, we planned not to report pooled results from the meta‐analysis but instead use an alternative approach to data synthesis (McKenzie 2019).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where possible and when sufficient data were available, we performed subgroup analysis by examining:

different types of anticoagulants;

different types of compression;

treatment length (short‐term about six weeks, or long‐term, about three to six months) as suggested by previous research and the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Union of Angiology guidelines (Kearon 2016; Nicolaides 2013);

dose of anticoagulant;

provoked or unprovoked DVT;

number of thrombosed calf veins (one versus multiple).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis by excluding RCTs with a high risk for bias in any domain displayed in the 'Risk of bias' graph and repeat the analyses.

Summary of findings and assessment of certainty of the evidence

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (www.gradepro.org), to present the main findings of the review (Atkins 2004). The population consisted of people with distal DVT. We included the following outcomes that are considered essential for decision‐making in our 'Summary of findings' tables:

recurrence of VTE;

major bleeding;

recurrence of DVT;

PE;

clinically relevant non‐major bleeding;

overall mortality;

mortality related to PE.

We create one 'Summary of findings' table for each comparison considered to be of clinical relevance. We evaluated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We assigned one of four levels of quality: high, moderate, low or very low, based on overall risk of bias, directness of the evidence, inconsistency of results, precision of the estimates and risk of publication bias as previously described (Higgins 2011). We explained the downgrading of the evidence in the footnotes. We did not stratify into risk groups or use external information for the assumed risk of the comparison group.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

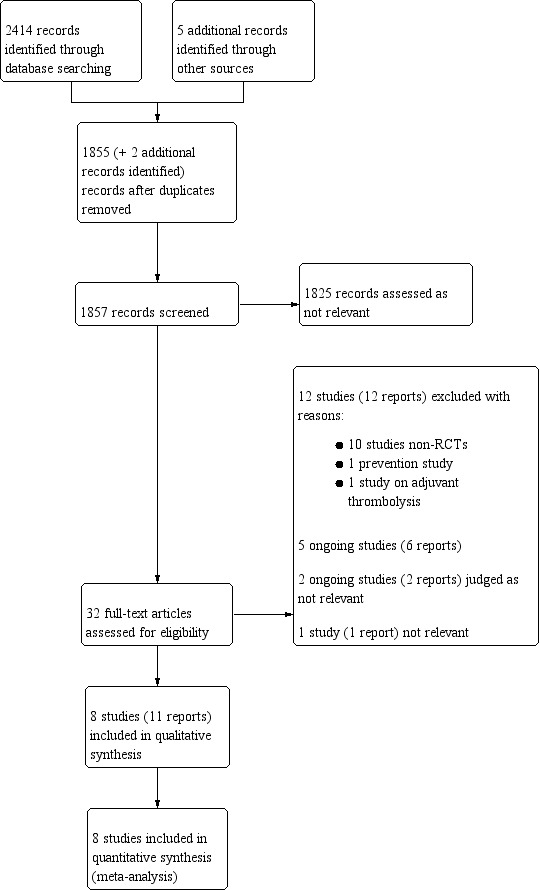

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We identified eight studies (11 records) which met the inclusion criteria (Ferrara 2006; Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001; Righini 2016; Schulman 1995; Schwarz 2010). We excluded 15 studies (15 records) (Dentali 2017; Donadini 2017; Galanaud 2017; Ho 2016; Leizorovicz 2003; McBane 2018; Musil 2000; NCT00816920; NCT01234064; NCT01252420; NCT02746185; Pegoraro 2016; Schulman 1986; Schwarz 2001; Utter 2016). In addition, we identified five ongoing studies (six records) (EUCTR2005‐004235‐21‐IT; NCT02722447; NCT03368313; NCT03590743; UMIN000028105).

Included studies

We included eight studies (11 records) that met the inclusion criteria, reporting outcomes on 1239 participants (Ferrara 2006; Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001; Righini 2016; Schulman 1995; Schwarz 2010). Three studies compared VKA treatment for six weeks versus 12 weeks or more (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995). From the remaining five studies, three studies compared anticoagulants versus no intervention or placebo for three months (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994), and two studies compared anticoagulants versus placebo for up to six weeks (Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010). One trial that enrolled postoperative patients studied provoked DVT (Ferrara 2006), and two trials that enrolled outpatients with a first episode of isolated calf DVT studied unprovoked DVT (Horner 2014; Righini 2016). The remaining five trials enrolled populations with provoked and unprovoked DVT without providing details for the subgroups (Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schwarz 2010). See Characteristics of included studies table for further details. Two included studies had more than one reference (Horner 2014; Righini 2016).

Excluded studies

We excluded 15 studies (15 reports) due to: retrospective study design (Dentali 2017; Donadini 2017; Ho 2016; Utter 2016), prospective single‐arm study design (McBane 2018), observational nature of the studies (Galanaud 2017; NCT00816920; NCT01252420), cohort studies (Pegoraro 2016; Schwarz 2001), prevention study (Leizorovicz 2003), testing of adjuvant thrombolysis (Schulman 1986), ongoing prevention study (NCT01234064), ongoing study for VTE in cancer (NCT02746185), and irrelevant (Musil 2000). See Characteristics of excluded studies table for further details.

Ongoing studies

We identified five ongoing studies (EUCTR2005‐004235‐21‐IT; NCT02722447; NCT03368313; NCT03590743; UMIN000028105). See Characteristics of ongoing studies table for details of the ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2; Figure 3. With the exception of performance bias, risk of bias domains were mostly low risk.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The randomisation method was unclear in two included RCTs (Ferrara 2006; Nielsen 1994).

We identified an unclear risk for allocation concealment in two included RCTs (Ferrara 2006; Schwarz 2010).

Blinding

There was a high risk of performance bias in seven studies because of their open‐label randomisation (Ferrara 2006; Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schwarz 2010). Only one study was double‐blind and judged at low risk of performance bias (Righini 2016).

One study reported outcome assessors were blinded (Righini 2016). The remaining studies did not blind outcome assessors, but we judged that the outcome measures reported by the studies this review (recurrent VTE, major bleeding, recurrent DVT, PE, clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, overall mortality and mortality related to PE and major bleeding) were not likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding of outcome assessors (Ferrara 2006; Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995; Schwarz 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

There was no incomplete outcome data reporting.

Selective reporting

We identified no findings of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

There was no other potential source of bias.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anticoagulant compared to no intervention or placebo for distal deep vein thrombosis treatment.

| Anticoagulant compared to no intervention or placebo for distal DVT treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with distal DVT Setting: hospital Intervention: anticoagulant Comparison: no intervention or placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention or placebo | Risk with anticoagulant | |||||

|

Recurrence of VTE (follow‐up: 3 months) |

Study population | RR 0.34 (0.15 to 0.77) | 496 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b |

— | |

| 91 per 1000 | 31 per 1000 (14 to 70) | |||||

| Major bleeding (follow‐up: 3 months) | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.13 to 4.62) | 480 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

— | |

| 8 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (1 to 38) |

|||||

|

Recurrence of DVT (follow‐up: 3 months) |

Study population | RR 0.25 (0.10 to 0.67) | 496 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b |

— | |

| 79 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (8 to 53) | |||||

|

PE (follow‐up: 3 months) |

Study population | RR 0.81 (0.18 to 3.59) | 480 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

— | |

| 12 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (2 to 44) | |||||

|

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding (follow‐up: 3 months) |

Study population | RR 3.34 (1.07 to 10.46) | 322 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b |

— | |

| 18 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (19 to 190) | |||||

| Overall mortality (follow‐up: 3 months) | Study population |

RR 3.2 (0.13 to 77.69) |

430 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

1 death reported in the anticoagulant group. 0 deaths reported in the no intervention or placebo group. | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Mortality related to PE (follow‐up: 3 months) | See comment | Not estimable | 430 (3 studies) |

See comment | 0 PE‐related deaths reported. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolism; RR: risk ratio; VTE: venous thromboembolism. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level as total number of events was fewer than 300. bUpgraded one level due to large treatment effect. cDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to very few events and 95% CIs include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm.

Summary of findings 2. Anticoagulation for three months or more compared to anticoagulation for six weeks for distal deep vein thrombosis treatment.

| Anticoagulation for 3 months or more compared to anticoagulation for 6 weeks for distal DVT treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with distal DVT Setting: hospital Intervention: VKA for ≥ 3 months Comparison: VKA for 6 weeks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with anticoagulation for 6 weeks | Risk with anticoagulation for ≥ 3 months | |||||

|

Recurrence of VTE (follow‐up: 16 weeks to 24 months) |

Study population | RR 0.42 (0.26 to 0.68) | 736 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b |

— | |

| 135 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (35 to 92) | |||||

|

Major bleeding (follow‐up: 16 weeks to 15 months) |

Study population | RR 3.42 (0.36 to 32.35) | 389 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

— | |

| 5 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (2 to 161) | |||||

|

Recurrence of DVT (follow‐up: 16 weeks to 15 months) |

Study population | RR 0.32 (0.16 to 0.64) | 389 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b |

— | |

| 144 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (23 to 92) | |||||

|

PE (follow‐up: 16 weeks to 15 months) |

Study population | RR 1.05 (0.19 to 5.88) | 389 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

— | |

| 10 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (2 to 59) | |||||

|

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding (follow‐up: 16 weeks to 15 months) |

Study population | RR 1.76 (0.90 to 3.42) | 389 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

— | |

| 60 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (54 to 204) | |||||

| Overall mortality | See comment | See comment | — | See comment | The included studies did not report on overall mortality. | |

|

Mortality related to PE (follow‐up: 15 months) |

See comment | Not estimable | 197 (1 study) |

See comment | 1 included study reported there were no cases of death from PE. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolism; RR: risk ratio; VTE: venous thromboembolism. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level as total number of events was fewer than 300. bUpgraded one level due to large treatment effect. cDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to very few events and 95% CIs include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm.

Five RCTs compared anticoagulation therapy versus placebo (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010). Three RCTs compared treatment with VKAs for six weeks versus three months or more (Schulman 1995; Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001).

We found no relevant studies for compression therapy versus no intervention or placebo, anticoagulation versus compression therapy and compression therapy versus no compression therapy.

Any anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo

Five RCTs compared anticoagulation therapy versus no intervention or placebo (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010). The studies used different forms of anticoagulation therapy: unfractionated heparin (Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994), nadroparin (Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010), and dalteparin (Horner 2014).

Primary outcomes

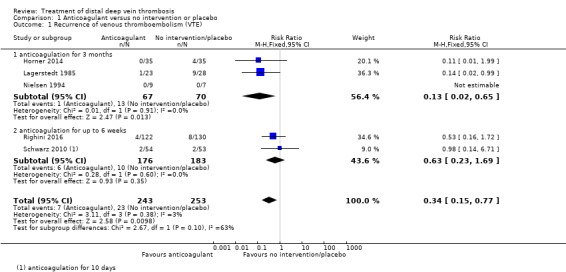

Recurrence of venous thromboembolism

Five RCTs compared the effect of anticoagulation therapy versus no intervention or placebo, for the rates of recurrence of VTE: two RCTs for up to six weeks (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.69; 2 studies, 359 participants; I2 = 0%) (Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010), and the remaining three RCTs for three months (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.65; 3 studies, 137 participants; I2 = 0%) (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994). The overall recurrence of VTE was lower in the anticoagulation group compared with the no intervention or placebo group (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.77; 5 studies, 496 participants; I2 = 3%; high‐certainty evidence). The test for subgroup differences showed no clear difference in recurrence of VTE between the subgroups anticoagulation for three months and anticoagulation for up to six weeks (P = 0.10) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 1 Recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Major bleeding

The meta‐analysis showed there was little to no difference in major bleeding events between anticoagulation therapy and no intervention or placebo (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.13 to 4.62; 4 studies, 480 participants; I2 = 26%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 2 Major bleeding.

Secondary outcomes

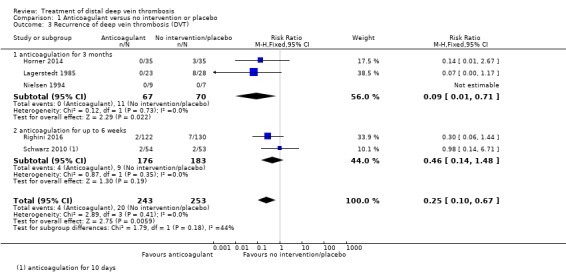

Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis

Results for recurrence of DVT showed a similar pattern to the results for recurrence of VTE. The overall recurrence of DVT was lower in the anticoagulation group compared with the no intervention or placebo group (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.67; 5 studies, 496 participants; I2 = 0%; high‐certainty evidence). The risk of recurrence of DVT in the subgroup of three months of anticoagulation was RR 0.09 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.71; 3 studies, 137 participants; I2 = 0%) and the subgroup of up to six weeks of anticoagulation was RR 0.46 (95% CI 0.14 to 1.48; 2 studies, 359 participants; I2 = 0%). The test for subgroup differences showed no clear difference in recurrence of DVT between the subgroups anticoagulation for three months and anticoagulation for up to six weeks (P = 0.18) (Analysis 1.3)

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 3 Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

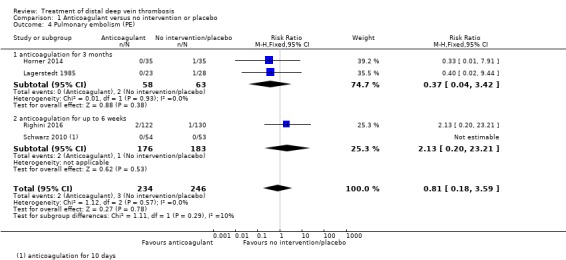

Pulmonary embolism

We identified no clear difference in PE between the anticoagulation group compared with the no intervention or placebo group (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.18 to 3.59; 4 studies, 480 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). The risk of PE in the subgroup of three months of anticoagulation was RR 0.37 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.42; 2 studies, 121 participants; I2 = 0%) and in the subgroup up to six weeks of anticoagulation was RR 2.13 (95% CI 0.20 to 23.21; 2 studies, 359 participants; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 4 Pulmonary embolism (PE).

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding events were increased in the anticoagulation group compared with the no intervention or placebo group (RR 3.34, 95% CI 1.07 to 10.46; 2 studies, 322 participants; I2 = 0%; high‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 5 Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding.

Overall mortality

Two studies reported no deaths in each of the study arms (Horner 2014; Schwarz 2010), and one study reported one death from cancer in the nadroparin group (Righini 2016) (RR 3.20, 95% CI 0.13 to 77.69; 3 studies, 430 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). The remaining two studies did not report on mortality (Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 6 Overall mortality.

Mortality related to pulmonary embolism or major bleeding

There were no cases of mortality related to PE or major bleeding in three studies (Horner 2014; Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010). The remaining two studies did not report on mortality related to PE or major bleeding (Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994).

Post‐thrombotic syndrome

There were no reports of PTS in four studies included in the quantitative synthesis (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Schwarz 2010). An additional publication of an included study (Righini 2016) reported on PTS (Galanaud 2018). A minimum of one year after randomisation, participants were assessed for PTS. Galanaud 2018 reported PTS was present in 54/178 (29%) of participants and was moderate or severe in 13/54 (24%) of cases. There was no clear difference in rates of PTS in the nadroparin compared with the placebo group (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.41; 1 study, 178 participants).

Resolution of symptoms

There were no reports for resolution of symptoms in the studies included in the quantitative synthesis (Horner 2014; Lagerstedt 1985; Nielsen 1994; Righini 2016; Schwarz 2010), but one additional publication of an included study (Righini 2016) did report on pain (Righini 2019). Righini 2019 reported no clear difference in the mean visual analogue pain scale (VAS) reduction between 106 participants treated with therapeutic nadroparin and 109 treated with placebo (after 1 week: 2.6 (SD 2.4) with nadroparin versus 2.3 (SD 2.0) with placebo; after 6 weeks: 4.4 (SD 2.8) with nadroparin versus 4.0 (SD 2.4) with placebo). The use of compression stockings was associated with a reduction in pain.

Any anticoagulation versus any anticoagulation: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist versus six weeks of vitamin K antagonist

Three RCTs compared treatment with VKAs for three months or more versus six weeks (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995). Stratified data for Schulman 1995 were only available for recurrent VTE.

Primary outcomes

Recurrence of venous thromboembolism

The incidence of recurrence of VTE was lower for the three months or more treatment period compared with the six weeks' treatment period (5.8% with 3 months or more versus 13.9% with 2 weeks; RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.68; 3 studies, 736 participants; I2 = 50%; high‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 1 Recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Major bleeding

There was no clear difference in major bleeding events between the three months or more and six weeks' treatment period (RR 3.42, 95% CI 0.36 to 32.35; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 2 Major bleeding.

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis

The risk for recurrence of DVT was reduced for the three months or more treatment period compared with the six weeks' treatment period (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.64; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 48%; high‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 3 Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Pulmonary embolism

There was probably little or no difference in recurrent PE between three months or more and six weeks' treatment period (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.19 to 5.88; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 4 Pulmonary embolism (PE).

Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding

There was no clear difference in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding events between the three months or more and the six weeks' treatment period (RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.90 to 3.42; 2 studies, 389 participants; I2 = 1%; low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 5 Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding.

Overall mortality

There were no reports of overall mortality in included studies for people with distal DVT (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995).

Mortality related to pulmonary embolism or major bleeding

Two included studies reported no deaths related to major bleeding (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001). One study reported no cases of mortality related to PE (Pinede 2001).

Post‐thrombotic syndrome

There were no reports of PTS (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995).

Resolution of symptoms

There were no reports of resolution of symptoms (Ferrara 2006; Pinede 2001; Schulman 1995).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our review has demonstrated that in people with distal DVT compared with no anticoagulation or placebo, anticoagulation reduces the risk of VTE recurrence. The results showed a clear effect for a three‐month course of anticoagulation, but not for a treatment lasting up to six weeks, likely as a result of a type II error due to the small number of events, or it may represent a true difference between a shorter or longer course of therapy. There were similar results for the outcome measure of recurrence of DVT, while there was no clear effect on risk of PE, again, likely as a result of a type II error. This benefit was obtained at the expense of clinically relevant non‐major bleeding, but not major bleeding. In a direct comparison of treatment duration, anticoagulation for three months or more was superior to a shorter course lasting up to six weeks, in terms of reduced risk for recurrence of VTE and DVT with no clear difference in major bleeding and clinically relevant non‐major bleeding.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The number of VTE events, as clearly shown in the corresponding forest plots, is relatively small and this may prompt further trials. However, the magnitude and direction of the effect is consistent in the subgroup of Analysis 1.1, but also in Analysis 2.1, suggesting that three months of anticoagulation may be more beneficial than a course of shorter duration.

Furthermore, most RCTs included in this review excluded recurrent and cancer‐associated distal DVT, which makes any extrapolation to these groups unsafe; in view of the high‐risk nature of these groups, it is plausible to accept that a minimum of three months of anticoagulation, if not longer, would be also required in these high‐risk situations. Certainly, RCTs on extended treatment (secondary prevention) would be required, ideally testing VKAs and DOACs in prophylactic and therapeutic doses, against placebo. Therapies associated with a low risk for bleeding, such as the prophylactic dose of DOACs may well be tested in secondary prevention of other distal DVTs thought to be high‐risk conditions, such as unprovoked DVT.

All but one RCT used a VKA in the investigational arm (following an initial course of heparin), which has the implication that our results apply only to this type of anticoagulant. Further RCTs with LMWHs or DOACs are required.

One of the included studies gave anticoagulation for 10 days only (Schwarz 2010), while the remainder of the studies used anticoagulation treatment for six weeks or more.

This review identified no studies using compression for the treatment of distal DVT. RCTs using compression would be required to make a statement regarding this intervention as either a stand‐alone treatment or adjunct to anticoagulant therapy.

Finally, our findings may not apply to people with single vein postoperative distal DVT in view of the findings of one RCT included in this review (Ferrara 2006), where there was no benefit of a three‐month course compared with the shorter six‐week course. The same may also apply to people with thrombosis limited in extent to the soleal or gastrocnemius veins, pending confirmatory results.

Quality of the evidence

We observed a low risk of bias for most attributes, with the exception of blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) due to the open‐label design of most RCTs. Nevertheless, the results of the present meta‐analysis update are generally consistent with a low amount of heterogeneity in almost all comparisons. However, the inclusion of RCTs only in this review must be viewed as a strong point.

Using the GRADE assessment, the certainty of evidence for recurrence of VTE and DVT was high; and for PE was low for the comparison of anticoagulation versus placebo and for the comparison of anticoagulation for six weeks versus three months.

The certainty of the evidence for the comparison of anticoagulation versus placebo was low for major bleeding and high for clinically relevant non‐major bleeding. The certainty of the evidence for major bleeding and clinically relevant non‐major bleeding for the comparison of anticoagulation for six weeks versus three months was low..

The certainty of the evidence was downgraded because of imprecision due to small number of events and wide confidence intervals.

Potential biases in the review process

The review authors made a conscious effort to identify all potentially relevant trials for inclusion in the present review. Nevertheless, publication bias still could have limited the validity of our results.

This review set out to assess only RCTs. Although five of the eight RCTs were published before 2010, the reporting of the study methodology was mostly adequate.

The review assessed recurrence of VTE, defined as DVT recurrence in the calf veins, or progression of DVT to proximal veins (e.g. popliteal or femoral vein) or PE, provided that these were objectively diagnosed with venography or ultrasonography for DVT and pulmonary angiography, computed tomography or V/Q scan for PE, as the primary outcome measure. Recurrence of DVT, which included DVT recurrence in the calf veins or progression of DVT to proximal veins, was included as a secondary outcome measure, but in future updates, data permitting, we will add symptomatic proximal DVT and clinically important VTE (proximal DVT and symptomatic PE) as additional important outcomes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results presented here agree with one systematic meta‐analysis of 20 case‐control or cohort studies and RCTs that included 2936 people with calf DVT (Franco 2017). Franco 2017 demonstrated a reduction in recurrent VTE rates in people who received anticoagulation compared to those who did not receive anticoagulation (either therapeutic or prophylactic, odds ratio (OR) 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.79), without an increase in the risk of major bleeding (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.73). PE rates were also lower with anticoagulation than in the control group (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.91; 1997 participants). There was a lower rate of recurrent VTE in people who received more than six weeks of anticoagulation in comparison to those who received six weeks of anticoagulation (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.90; 4 studies, 1136 participants). In comparison, our meta‐analysis included only RCTs known to provide a higher level of evidence than case‐control studies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our review suggests a benefit for people with distal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) treated with anticoagulation therapy using VKA with little or no difference in major bleeding although there was an increase in clinically relevant non‐major bleeding when compared with no intervention or placebo. This evidence may be used in daily practice for treatment of distal DVT and influence decisions made in guidelines for treatment of DVT, considering the certainty of evidence included in this review.

Implications for research.

The small number of participants of this review prompts for more extended research in distal DVT. More randomised control trials comparing different treatments and different treatment periods with placebo or compression therapy are required to support these results. An interesting endpoint for future randomised control trials is the discrimination of symptomatic or asymptomatic recurrence of DVT or venous thromboembolism.

Acknowledgements

The review authors and the Cochrane Vascular editorial base are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Scott M Stevens, University of Utah, USA; Shannon M Bates, McMaster University, Canada; Dee Shneiderman, USA.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Database searches February 2019

| Source | Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies | #1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Pulmonary Embolism EXPLODE ALL AND INREGISTER #2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Thromboembolism EXPLODE ALL AND INREGISTER #3 MESH DESCRIPTOR Thrombosis EXPLODE ALL AND INREGISTER #4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Venous Thromboembolism EXPLODE ALL AND INREGISTER #5 MESH DESCRIPTOR Venous Thrombosis EXPLODE ALL AND INREGISTER #6 (vein* or ven*) adj thromb* AND INREGISTER #7 blood adj3 clot* AND INREGISTER #8 deep vein thrombosis AND INREGISTER #9 lung adj3 clot* AND INREGISTER #10 PE or DVT or VTE AND INREGISTER #11 peripheral vascular thrombosis AND INREGISTER #12 post‐thrombotic syndrome AND INREGISTER #13 pulmonary embolism AND INREGISTER #14 pulmonary adj3 clot* AND INREGISTER #15 thrombus* or thrombopro* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol* or microembol* AND INREGISTER #16 venous thromboembolism AND INREGISTER #17 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 #18 below the knee AND INREGISTER #19 cDVT AND INREGISTER #20 ICMVT AND INREGISTER #21 IDDVT AND INREGISTER #22 infrapopliteal deep veins AND INREGISTER #23 calf AND INREGISTER #24 distal AND INREGISTER #25 #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 #26 #25 AND #17 |

360 |

| CENTRAL via CRSO | #1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Pulmonary Embolism EXPLODE ALL TREES 890 #2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Thromboembolism EXPLODE ALL TREES 1784 #3 MESH DESCRIPTOR Thrombosis EXPLODE ALL TREES 4275 #4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Venous Thromboembolism EXPLODE ALL TREES 479 #5 MESH DESCRIPTOR Venous Thrombosis EXPLODE ALL TREES 2413 #6 (((vein* or ven*) adj thromb*)):TI,AB,KY 8171 #7 (blood adj3 clot*):TI,AB,KY 3981 #8 (deep vein thrombosis):TI,AB,KY 3534 #9 (lung adj3 clot*):TI,AB,KY 7 #10 (PE or DVT or VTE):TI,AB,KY 5333 #11 (peripheral vascular thrombosis):TI,AB,KY 0 #12 (post‐thrombotic syndrome):TI,AB,KY 133 #13 (pulmonary embolism):TI,AB,KY 2206 #14 (pulmonary adj3 clot*):TI,AB,KY 10 #15 (thrombus* or thrombopro* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol* or microembol*):TI,AB,KY 23686 #16 (venous thromboembolism):TI,AB,KY 2471 #17 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 30248 #18 (below the knee):TI,AB,KY 173 #19 cDVT:TI,AB,KY 2 #20 ICMVT:TI,AB,KY 1 #21 IDDVT:TI,AB,KY 4 #22 (infrapopliteal deep veins):TI,AB,KY 0 #23 calf:TI,AB,KY 1451 #24 distal:TI,AB,KY 8172 #25 #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 9724 #26 #17 AND #25 901 |

901 |

| MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE) 1946 to present 2017, 2018 and 2019 only |

1 Pulmonary Embolism/ 2 Thromboembolism/ 3 Thrombosis/ 4 exp Venous Thromboembolism/ 5 exp Venous Thrombosis/ 6 ((vein* or ven*) adj thromb*).ti,ab. 7 (blood adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 8 deep vein thrombosis.ti,ab. 9 (lung adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 10 (PE or DVT or VTE).ti,ab. 11 peripheral vascular thrombosis.ti,ab. 12 post‐thrombotic syndrome.ti,ab. 13 pulmonary embolism.ti,ab. 14 (pulmonary adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 15 (thrombus* or thrombopro* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol* or microembol*).ti,ab. 16 venous thromboembolism.ti,ab. 17 or/1‐16 18 "below the knee".ti,ab. 19 cDVT.ti,ab. 20 ICMVT.ti,ab. 21 IDDVT.ti,ab. 22 "infrapopliteal deep veins".ti,ab. 23 calf.ti,ab. 24 distal.ti,ab. 25 or/18‐24 26 17 and 25 27 randomized controlled trial.pt. 28 controlled clinical trial.pt. 29 randomized.ab. 30 placebo.ab. 31 drug therapy.fs. 32 randomly.ab. 33 trial.ab. 34 groups.ab. 35 or/27‐34 36 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 37 35 not 36 38 26 and 37 39 (2017* or 2018* or 2019*).ed. 40 38 and 39 41 from 40 keep 1‐244 |

244 |

| Embase 2017, 2018 and 2019 only | 1 lung embolism/ 2 thromboembolism/ 3 thrombosis/ 4 exp venous thromboembolism/ 5 exp vein thrombosis/ 6 ((vein* or ven*) adj thromb*).ti,ab. 7 (blood adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 8 deep vein thrombosis.ti,ab. 9 (lung adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 10 (PE or DVT or VTE).ti,ab. 11 peripheral vascular thrombosis.ti,ab. 12 post‐thrombotic syndrome.ti,ab. 13 pulmonary embolism.ti,ab. 14 (pulmonary adj3 clot*).ti,ab. 15 (thrombus* or thrombopro* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol* or microembol*).ti,ab. 16 venous thromboembolism.ti,ab. 17 or/1‐16 18 "below the knee".ti,ab. 19 cDVT.ti,ab. 20 ICMVT.ti,ab. 21 IDDVT.ti,ab. 22 "infrapopliteal deep veins".ti,ab. 23 calf.ti,ab. 24 distal.ti,ab. 25 or/18‐24 26 17 and 25 27 randomized controlled trial/ 28 controlled clinical trial/ 29 random$.ti,ab. 30 randomization/ 31 intermethod comparison/ 32 placebo.ti,ab. 33 (compare or compared or comparison).ti. 34 ((evaluated or evaluate or evaluating or assessed or assess) and (compare or compared or comparing or comparison)).ab. 35 (open adj label).ti,ab. 36 ((double or single or doubly or singly) adj (blind or blinded or blindly)).ti,ab. 37 double blind procedure/ 38 parallel group$1.ti,ab. 39 (crossover or cross over).ti,ab. 40 ((assign$ or match or matched or allocation) adj5 (alternate or group$1 or intervention$1 or patient$1 or subject$1 or participant$1)).ti,ab. 41 (assigned or allocated).ti,ab. 42 (controlled adj7 (study or design or trial)).ti,ab. 43 (volunteer or volunteers).ti,ab. 44 trial.ti. 45 or/27‐44 46 26 and 45 47 (2017* or 2018* or 2019*).em. 48 46 and 47 |

747 |

| CINAHL 2017, 2018 and 2019 only | S42 S40 AND S41 S41 EM 2017 OR EM 2018 OR EM 2019 S40 S26 AND S39 S39 S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 S38 MH "Random Assignment" S37 MH "Single‐Blind Studies" or MH "Double‐Blind Studies" or MH "Triple‐Blind Studies" S36 MH "Crossover Design" S35 MH "Factorial Design" S34 MH "Placebos" S33 MH "Clinical Trials" S32 TX "multi‐centre study" OR "multi‐center study" OR "multicentre study" OR "multicenter study" OR "multi‐site study" S31 TX crossover OR "cross‐over" S30 AB placebo* S29 TX random* S28 TX trial* S27 TX "latin square" S26 S17 AND S25 S25 S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 S24 TX distal S23 TX calf S22 TX infrapopliteal deep veins S21 TX IDDVT S20 TX ICMVT S19 TX cDVT S18 TX below the knee S17 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 S16 TX venous thromboembolism S15 TX thrombus* or thrombopro* or thrombotic* or thrombolic* or thromboemboli* or thrombos* or embol* or microembol* S14 TX pulmonary n3 clot* S13 TX pulmonary embolism S12 TX post‐thrombotic syndrome S11 TX peripheral vascular thrombosis S10 TX PE or DVT or VTE S9 TX lung n3 clot* S8 TX deep vein thrombosis S7 TX blood n3 clot* S6 TX ((vein* or ven*) n thromb*) S5 (MH "Venous Thrombosis+") S4 (MH "Venous Thromboembolism") S3 (MH "Thrombosis") S2 (MH "Thromboembolism") S1 (MH "Pulmonary Embolism") |

50 |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | below the knee OR distal OR calf | Interventional Studies | Venous Thromboembolism OR Venous Thrombosis OR Pulmonary Embolism OR deep vein thrombosis OR DVT | 94 |

| ICTRP Search Portal | below the knee OR distal OR calf | Venous Thromboembolism OR Venous Thrombosis OR Pulmonary Embolism OR deep vein thrombosis OR DVT | 18 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) | 5 | 496 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.15, 0.77] |

| 1.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 3 | 137 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.02, 0.65] |

| 1.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.23, 1.69] |

| 2 Major bleeding | 4 | 480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.13, 4.62] |

| 2.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 2 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.01, 4.80] |

| 2.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [0.13, 77.69] |

| 3 Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | 5 | 496 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.10, 0.67] |

| 3.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 3 | 137 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 0.71] |

| 3.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.14, 1.48] |

| 4 Pulmonary embolism (PE) | 4 | 480 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.18, 3.59] |

| 4.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 2 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.04, 3.42] |

| 4.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [0.20, 23.21] |

| 5 Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding | 2 | 322 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.34 [1.07, 10.46] |

| 5.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [0.66, 8.30] |

| 5.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 1 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.59 [0.52, 176.20] |

| 6 Overall mortality | 3 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [0.13, 77.69] |

| 6.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 360 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [0.13, 77.69] |

| 7 Mortality related to PE | 3 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 360 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Mortality related to major bleeding | 3 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.1 anticoagulation for 3 months | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 anticoagulation for up to 6 weeks | 2 | 360 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Post‐thrombotic syndrome (PTS) | 1 | 178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.58, 1.41] |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 7 Mortality related to PE.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 8 Mortality related to major bleeding.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticoagulant versus no intervention or placebo, Outcome 9 Post‐thrombotic syndrome (PTS).

Comparison 2. Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) | 3 | 736 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.26, 0.68] |

| 2 Major bleeding | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.42 [0.36, 32.35] |

| 3 Recurrence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.16, 0.64] |

| 4 Pulmonary embolism (PE) | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.19, 5.88] |

| 5 Clinically relevant non‐major bleeding | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.90, 3.42] |

| 6 Mortality related to PE | 1 | 197 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Mortality related to major bleeding | 2 | 389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 6 Mortality related to PE.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Anticoagulant versus any anticoagulant: three months or more of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) versus six weeks of VKA, Outcome 7 Mortality related to major bleeding.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ferrara 2006.

| Methods | Open, randomised, controlled clinical trial | |

| Participants | Number: 192 participants Group 1: 68 participants, involved a single collecting vein. 24 participants had undergone orthopaedic surgery, 22 abdominal surgery and 22 urological surgery. The thrombus was present in a single collecting vein in 48 of these participants and in a single muscular vein in 20. This group was subdivided into 2 subgroups of 34 participants (called 1A and 1B); in the 1A subgroup, the treatment was continued for 12 weeks, and in the 1B subgroup, it was continued for 6 weeks. Group 2: 124 participants involved > 1 collecting vein. 35 participants had undergone orthopaedic surgery, 45 abdominal surgery and 44 urological surgery. 89 of these participants with distal DVT in > 1 vessel presented with thrombotic lesions in 2 vessels and 35 participants had thrombotic lesions in 3 vessels. This group was divided into 2 subgroups of 62 participants (called 2A and 2B); in the 2A subgroup, treatment was continued for 12 weeks, and in the 2B subgroup, it was continued for 6 weeks. Age (range; years): 44–71, group 1; 48–72, group 2 Gender (M/F): 23/45, group 1; 41/83, group 2 |

|

| Interventions | VKAs for 12 weeks vs VKAs for 6 weeks. All participants were treated with nadroparin calcium at daily doses of 200 IU anti‐Xa per kg bodyweight, given in 2 doses. Contemporarily, sodium warfarin was administered, and nadroparin was stopped until prothrombin activity had stabilised at about 30–40% with an INR of 2–3. Heparin treatment was stopped in all participants after 5 or 6 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Extension of calf DVT to proximal veins, symptomatic PE and major bleeding | |

| Notes | People with cancer, inherited coagulopathies (factor V Leiden, G20120 mutation in prothrombin, hyperhomocystinaemia, dysplasminogenaemia, deficits in vitamin C or protein S, dysfibrinogenaemia), hyperviscosity syndromes or antiphospholipid antibodies, or absolute or relative contraindications for heparin or anticoagulant treatment were excluded. Funding/support: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the allocation concealment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No blinding of outcome assessment but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The published report included all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appeared free of other sources of bias. |

Horner 2014.

| Methods | Randomised, open‐label trial 93 assessed for eligibility and 23 excluded 0 lost to follow‐up |

|

| Participants | Number: 70 participants 35 allocated to therapeutic anticoagulation and 35 allocated to conservative management Age (mean ± SD; years): 60.9 ± 17.8, therapeutic anticoagulation; 59.8 ± 17.9, conservative management Gender (M/F): 9/26, therapeutic anticoagulation; 15/20, conservative management |

|

| Interventions | Dalteparin/VKA for 3 months vs no anticoagulation. Intervention group: initially given a subcutaneous therapeutic dose of dalteparin with phased transition to an oral VKA for a total of 3 months. All participants were followed up in a dedicated anticoagulant clinic for INR monitoring, with target INR 2.5 (range: 2.0–3.0). Control group: given anti‐inflammatory medication and paracetamol for symptomatic relief, but received no anticoagulation. All participants regardless of treatment allocation were referred for fitted grade 2 compression stockings. |

|

| Outcomes | Proximal propagation with or without symptoms, symptomatic PE, VTE‐related sudden death or major bleeding | |

| Notes | People with previous VTE were excluded. Funding/support: "This work was funded by the College of Emergency Medicine and supported by the National Institute for Health Research through the comprehensive local research network." |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Via a web‐based platform with an externally generated randomisation sequence in variable permuted block sizes. Participants were randomised in a 1:1 allocation ratio. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central allocation via a web‐based platform. Quote: "Randomization occurred following written informed consent, such that allocation concealment was maintained until the absolute pint of inclusion." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No blinding of outcome assessment but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published report included all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appeared free of other sources of bias. |

Lagerstedt 1985.

| Methods | Randomised, open label trial 52 randomised, 1 excluded and lost follow‐up |

|

| Participants | Number: 51 participants 23 received warfarin and 28 control group with no anticoagulation Age (mean ± SD; years); 65.0 ± 14.4, warfarin group; 60.9 ± 12.4, control group Gender (M/F): 14/9, warfarin group; 15/13, control group |

|

| Interventions | UFH/warfarin for 3 months vs no anticoagulation All participants received a 5‐day course of sodium heparin intravenously, 500–600 IU/kg/day in 6 divided doses. Intervention: participants receiving oral anticoagulation were started on warfarin as soon as a diagnosis was confirmed by phlebography. The aim was to achieve an INR of 2.5–4.2. Heparin treatment was extended for 1–2 days if the therapeutic level was not reached on the 5th day. Control: no anticoagulation All participants were asked to wear graded compression stocking during the study |

|

| Outcomes | VTE recurrence, clinical or revealed (or both) on imaging | |

| Notes | People with previous VTE, PE, thrombi extending into popliteal vein, malignancy were excluded. Funding/support: quote: "The study was supported in part by grants from the National Organisation against Heart and Lung Diseases." |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Used sealed envelopes. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Used sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No blinding of outcome assessment but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published report included all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appeared free of other sources of bias. |

Nielsen 1994.

| Methods | Randomised, open‐label trial | |

| Participants | Number; 16 participants 9 received anticoagulant treatment and 7 received no anticoagulant treatment Age: not specified for participants with distal DVT Gender: not specified for participants with distal DVT |

|

| Interventions | UFH/phenprocoumon for 3 months vs no anticoagulation. Intervention: sodium heparin administered intravenously. Treatment initiated by bolus injection of 10,000 IU, followed by continuous infusion (20,000 IU of heparin in 500 mL of 5% dextrose) with APTT target at 1.5–2.5. Phenprocoumon was given from the 3rd day. Heparin treatment was continued for ≥ 6 days or until INR had reached 2.0–4.3. Control: participants were treated with phenylbutazone 200 mg 3 times at the day of admission and then 100 mg 3 times daily for the following 9 days. All participants were actively mobilised from the day of admission and wore graduated compressing stockings. |

|

| Outcomes | Propagation or development of new VTE | |

| Notes | People with clinical symptoms of PE were excluded. Study protocol involved 90 participants with DVT; 16 were diagnosed with distal DVT. Funding/support: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about sequence generation process. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Random allocation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No blinding of outcome assessment but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published report included all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appeared free of other sources of bias. |

Pinede 2001.

| Methods | Open‐label, randomised, controlled trial | |