Abstract

Background

Evidence for the effectiveness of nutritional supplements containing protein and energy, often prescribed for older people, is limited. Malnutrition is more common in this age group and deterioration of nutritional status can occur during illness. It is important to establish whether supplementing the diet is an effective way of improving outcomes for older people at risk from malnutrition.

Objectives

This review examined trials for improvement in nutritional status and clinical outcomes when extra protein and energy were provided, usually as commercial 'sip‐feeds'.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Healthstar, CINAHL, BIOSIS, CAB abstracts. We also hand searched nutrition journals and reference lists and contacted 'sip‐feed' manufacturers.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of oral protein and energy supplementation in older people, with the exception of groups recovering from cancer treatment or in critical care.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed trials prior to inclusion and independently extracted data and assessed trial quality. Authors of trials were contacted for further information as necessary.

Main results

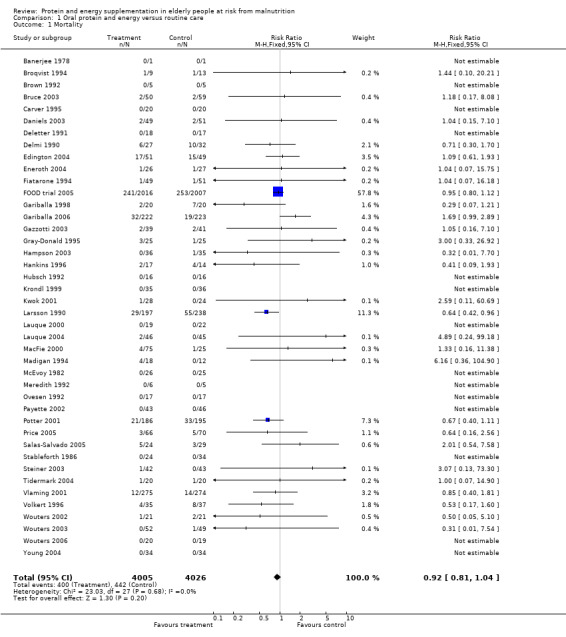

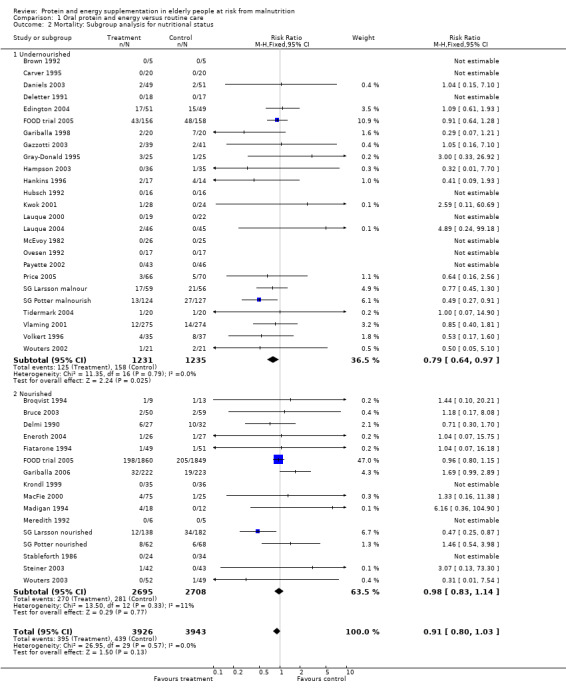

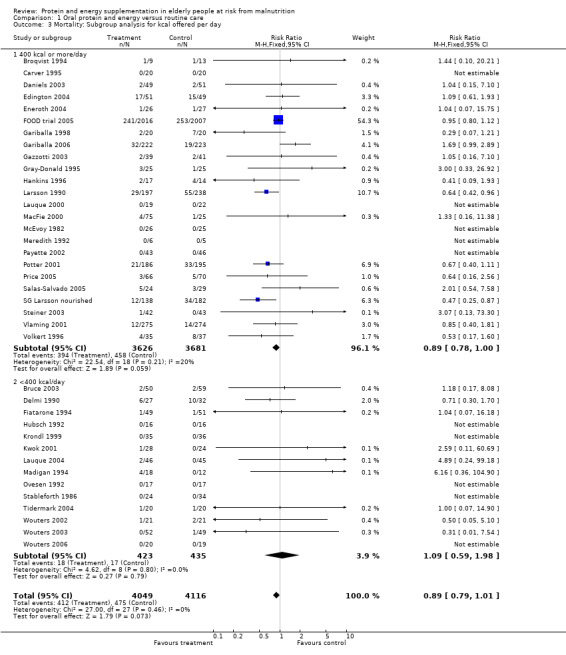

Sixty‐two trials with 10,187 randomised participants have been included in the review. Maximum duration of intervention was 18 months. Most included trials had poor study quality. The pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) for percentage weight change showed a benefit of supplementation of 2.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8 to 2.5) from 42 trials. There was no significant reduction in mortality in the supplemented compared with control groups (relative risk (RR) 0.92, CI 0.81 to 1.04) from 42 trials. Mortality results were statistically significant when limited to trials in which participants (N = 2461) were defined as undernourished (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97).

The risk of complications was reduced in 24 trials (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99). Few trials were able to suggest any functional benefit from supplementation. The WMD for length of stay from 12 trials also showed no statistically significant effect (‐0.8 days, 95% CI ‐2.8 to 1.3). Adverse effects included nausea or diarrhoea.

Authors' conclusions

Supplementation produces a small but consistent weight gain in older people. Mortality may be reduced in older people who are undernourished. There may also be a beneficial effect on complications which needs to be confirmed. However, this updated review found no evidence of improvement in functional benefit or reduction in length of hospital stay with supplements. Additional data from large‐scale multi‐centre trials are still required.

Plain language summary

Protein and energy supplementation in elderly people at risk from malnutrition

Much emphasis is placed on the importance of good diet, usually in relation to concern about the health risks of obesity. However it has been generally agreed that the risk of undernutrition rather than overnutrition is the main cause for concern in elderly people, particularly those who are hospitalised or institutionalised. Malnutrition has been shown to have important effects on recovery in a broad range of patients and conditions. It has been associated strongly with impaired immune response, impaired muscle and respiratory function, delayed wound healing, overall increased complications, longer rehabilitation, greater length of hospital stay and increased mortality. Oral protein and energy supplements are potentially safer and easier to administer than nasogastric enteral feeds and are therefore particularly suited to elderly people and are also widely used. However, there may be problems with the willingness and ability of older people to consume oral supplements, and supplements may not be used effectively. Even if supplements are prescribed, they may not always be given, or are given but not consumed. In addition to taste, the composition and timing of administration in relation to meals may be important. Efforts also need to be made to provide normal meals and snacks which meet the needs of elderly people and to provide assistance with feeding if required.

A total of 10,187 randomised participants from the 62 trials has been included. Maximum duration of intervention was 18 months. The reviewers suggest that supplementation appears to produce a small but consistent weight gain. There was no evidence in this updated review of a beneficial effect on mortality overall, but there may be a beneficial effect on mortality in people who are undernourished. Supplementation may also reduce the number of complications. The reported acceptance of supplements was variable between trials. Some adverse effects such as nausea or diarrhoea were reported. However, there were problems of study design and quality. More studies are required to confirm the beneficial effect on the number of complications, to establish whether there is a beneficial effect on mortality for undernourished elderly people and to provide evidence about whether protein and energy supplements can improve morbidity and functional status in frail older people.

Background

Description of the condition

Much emphasis is placed on the importance of good diet, usually in relation to concern about the health risks of obesity. However it has been generally agreed that the risk of undernutrition rather than overnutrition is the main cause for concern in elderly people, particularly those who are hospitalised or institutionalised (DoH 1992; Potter 1988). There have been recent UK and international initiatives to improve practice in this area of health care (Council Europe 2002; NHSQIS 2003; NICE 2006).

There is no universally accepted clinical definition of malnutrition or undernutrition (the terms are used interchangeably here). However, Allison 2000 defined undernutrition as "a state of energy, protein or other specific nutrient deficiency which produces a measurable change in body function and is associated with worse outcome from illness as well as being specifically reversed by nutritional support".

Increased length of hospital stay is associated with malnutrition. Studies have reported the presence of malnutrition in a substantial proportion of hospital patients both on admission and during hospital stay in the USA, Norway, Ireland, UK, Sweden, The Netherlands and Australia (Bistrian 1976; Bruun 1999; Corish 2000; Edington 2000; Flodin 2000; Kruizenga 2003; Zador 1987). This is a particular problem for elderly people as a) over 40% of hospital admissions are elderly people who have longer periods of illness and longer hospital stay (HCUP 2002), and b) data show that elderly patients are more at risk of malnutrition than others (Gallager‐Allred 1996; Kruizenga 2003; McWhirter 1994).

Reasons for poor nutritional status in older people are multi‐faceted and include the physiological, psychological and social changes associated with aging which affect food intake and body weight, exacerbated by the presence of illness. Five to ten percent of elderly people in the community may also be malnourished (McCormack 1997). Elderly people who are already malnourished at home may be at a disadvantage if admitted to hospital for treatment. Within Europe and the USA, nutritional status has been shown to decline with hospital stay due to a lack of adequate nutritional intake during hospitalisation (Corish 2000; Larsson 1990; McWhirter 1994; Sullivan 1999). This is because the poor nutritional state of many patients often goes unrecognised and there may be a lack of awareness of malnutrition by health professionals who receive little training on nutritional issues (Elia 2001). Disease or treatment such as surgery may also increase nutritional demands, so patients who have a poor appetite or difficulty eating will lose weight.

Measurement of nutritional status

Commonly used methods to measure nutritional status are body mass index (BMI) (weight in kg / height in m2), anthropometry such as triceps skin fold thickness and arm muscle circumference, and history of recent weight loss. Serum albumin has also been used as a measure of nutritional status as malnutrition causes a decrease in the rate of synthesis of albumin, but serum albumin levels are known to be affected by changes in fluid balance and illness itself. Illness, injury and age may all therefore confound the measurement of nutritional status. Improved tools for nutrition risk screening have been developed, which include subjective measures of recent weight loss and inadequate intake (BAPEN 2003). The difficulty of defining and measuring nutritional status may help explain some of the wide variation in the reported prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalised adults of between 11% and 40% (Corish 2000).

Effects of malnutrition

Malnutrition has been shown to have important effects on recovery in a broad range of patients and conditions. It impacts on both physiological and biochemical systems and has been associated strongly with impaired immune response, impaired muscle and respiratory function, delayed wound healing, overall increased complications, longer rehabilitation, greater length of hospital stay and increased mortality (Kelly 1984; Potter 1995; Robinson 1987; Sullivan 1990; Windsor 1988). Apathy, depression, fatigue and a loss of will to recover have been demonstrated following weight loss in experimental volunteers (Keys 1950).

Costs

The economic consequences of malnutrition are also considerable. In 1992 the economic cost to the United Kingdom National Health Service of preventable malnutrition was estimated to be £266 (297 EUR, 2009 currency translation) million a year, mainly due to increased length of bed occupancy and associated treatment costs (Lennard‐Jones 1992). More recently, it has been estimated that the annual additional health care cost of malnutrition and associated disease is over £5.3 (5,9 EUR, 2009 currency translation) billion in the UK (Elia 2005). However more studies which gather information regarding the cost‐effectiveness of nutritional support are required.

Description of the intervention

Oral supplements are potentially safer and easier to administer than nasogastric enteral feeds and are therefore particularly suited to elderly people and are also widely used. However, there may be problems with the willingness and ability of older people to consume oral supplements, and supplements may not be used effectively. Even if supplements are prescribed, they may not always be given, or are given but not consumed (Peake 1998). In addition to taste, the macronutrient composition and timing of administration in relation to meals may be important (Wilson 2002). Efforts also need to be made to provide normal meals and snacks which meet the needs of elderly people and to provide assistance with feeding if required.

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review in 1998 examined the effects of oral and enteral protein and energy supplementation in adults from thirty eligible trials which were identified up to the end of 1996 (Potter 1998). Outcomes assessed were change in body weight and arm muscle circumference, and case fatality. There were indications that nutritional supplementation was associated with improvements in outcomes assessed. However, uncertainties remained, because of the poor quality of included trials.

The present Cochrane review of older adults, when last updated and published in January 2005 included 49 trials with 4790 randomised participants. Most trials had poor study quality. Results suggested a beneficial effect of supplementation for percentage weight change from 34 trials (weighted mean difference (WMD) 2.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 2.7) and a reduced mortality in the supplemented groups compared to the control groups from 32 trials (relative risk (RR) 0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 2.7).

Other reviews have included a review of randomised and non randomised studies in different diagnostic groups with chronic non malignant disorders (Akner 2001) suggesting that patients with certain disorders (such as hip fracture) may be more likely to benefit than others. Stratton 2003 and colleagues also extensively reviewed the evidence base for nutritional support in a recently published book, including a review of 166 randomised and non‐randomised trials of oral nutritional support published up to 2002 in all ages, across different disease groups, both in hospital and in the community.

A recent update of the systematic review for the Cochrane Collaboration (Avenell 2006), of nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in older people, included 21 trials involving 1727 participants. There was some evidence that oral protein and energy feeds (evaluated by eight trials), reduced unfavourable outcome (death or complications), but there was no demonstrable effect on deaths alone in participants recovering from hip fracture. However overall, the evidence was still weak due to defects in the reviewed studies, particularly inadequate size, methodology and outcome assessment.

A Cochrane systematic review of dietary advice for illness‐related malnutrition in adults of all ages has also been carried out (Baldwin 2008). Thirty‐six studies (37 comparisons) met the inclusion criteria with 2714 randomised participants. No comparison showed a significant difference in mortality. There were several significant results for change in weight and other nutritional indices favouring nutritional intervention, but it remains uncertain whether nutritional supplements and dietary advice produce the same effects. There was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about clinical outcomes and cost. For specific information on dietary advice for illness related malnutrition, the reader is referred to Baldwin 2000.

Elderly people who are ill and malnourished may be expected to benefit more from supplementation. Providing higher energy supplements over a longer duration may also be expected to be associated with greater benefit. The present review includes a more comprehensive search for randomised trials to specifically examine the effectiveness of oral protein and energy supplements for elderly people.

Objectives

To assess the effects and acceptability of oral dietary supplements in both hospitalised elderly people and elderly people in the community, irrespective of setting:

to test the null hypothesis that there was no difference in outcomes between participants who were given oral nutritional supplements compared to those participants who were given no intervention, a placebo, or an alternative supplement with a different amount of calories and protein.

to carry out subgroup analysis in order to assess whether participants who were malnourished, were ill, were aged 75 years or over, were given supplements of 400 kcal or more or who had longer duration (35 days or more) of supplementation showed most benefit.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Ideally studies were randomised controlled trials, but we also considered quasi‐randomised controlled trials (for example allocation by day of week, date of birth, alternation). We only accepted trials that had a minimum duration of two weeks (with a minimum duration of intervention of one week).

Types of participants

To be defined as elderly, groups of study participants had to have a minimum average age of 65 years. All groups were included, with the exception of groups exclusively of older people in critical care or recovering from cancer treatment who may have had specific nutritional needs relating to their condition. Mixed groups of patients, where some were recovering from cancer and some had been undergoing critical care were included. Efforts were made to obtain data for the groups of interest from the authors.

Types of interventions

Interventions were aimed at improving the intake of protein and energy using only the normal oral route. Protein was provided together with non‐protein energy sources such as carbohydrate and fat, and with or without added minerals and vitamins. We were interested in supplements in the form of:

commercial sip feeds;

milk based supplements;

via the fortification of normal food sources.

Studies of dietary advice alone were not included in this review. We also excluded studies of specially designed immunomodulatory supplements or supplements of specific amino acids. The comparison intervention was 'usual practice' (for example using no supplement or an alternative supplement with a different amount of calories and protein) or a placebo (for example a low energy drink). Although protein‐only supplementation has occasionally been used for experimental purposes, it would not be considered for routine use and was therefore excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

(for all participants unless otherwise stated)

all cause mortality;

morbidity, number of people with complications (for example pressure sores, deep vein thrombosis, respiratory and urinary infections);

functional status (for example cognitive functioning, muscle functioning, mobility, ability to perform activities of daily living).

Secondary outcomes

participants' perceived quality of life, ideally using a validated scale;

length of hospital stay (hospital patients only);

number of primary care contacts (non‐hospital participants only);

adverse effects of nutritional supplementation;

level of care and support required;

number of hospital / care home admissions / re admissions;

nutritional status (change in anthropometry, for example percentage weight change, percentage change arm muscle circumference);

percentage change in dietary intake (energy and protein intake from food and supplements);

compliance with intervention (proportion of the supplement provided which is consumed, alone or with assistance);

economic outcomes.

Desired timing of outcome measures

The outcome measurements were evaluated at the last available time point of the studies. Short term outcomes were defined as up to three months, medium term outcomes 3 to 6 months and long term outcomes over six months.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 4, 2007);

MEDLINE (until November 2007);

EMBASE (until December 2007);

Healthstar (until March 2001);

CINAHL (until November 2007);

BIOSIS (until December 2007);

CAB abstracts (until October 2007).

The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted for the other electronic databases searched.

The nutrition search strategy was based on the strategy used in a Cochrane review by one of the authors (Avenell 2004). Some additional terms relating to malnutrition and food sources were also included. Phases one and two of the search strategy for randomised controlled trials developed by the United Kingdom Cochrane Centre were used (Alderson 2004). For a detailed search strategy see Appendix 1.

Databases of registered trials were also searched:

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), December 2007.

The results were double‐checked with trials identified by two of the authors for previous systematic reviews: trials of routine protein energy supplementation in adults identified between February 1979 and July 1996 using MEDLINE (Potter 1998), and more recently, trials of nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in the elderly (Avenell 2004), searching The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Healthstar, CINAHL, BIOSIS and CAB abstracts.

Searching other resources

Handsearching

The following journals were hand searched:

Journal of Human Nutrition: Applied Nutrition: Vol 36A(1) 1982 ‐ Vol 41A(6) 1987;

Journal of Human Nutrition: Clinical Nutrition: Vol 36C(1) 1982 ‐ Vol 41C(6) 1987;

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics: Vol 1(1) 1988 ‐ Vol 20(3) 2007;

Clinical Nutrition: Vol 1(1) 1982 ‐ Vol 26(6) 2007;

Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Vol 5(1) 1981 ‐ Vol 31(6) 2007;

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society: Vol 50(2) 1991 ‐ Vol 53(3) 1994 and Vol 57(1) 1998 ‐ Vol 66 2007;

Journal of the American Dietetic Association Vol 90(1) 1990 ‐ Vol 107(7) 2007;

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Vol 62(10) 1995 ‐ Vol 86(4) 2007;

Australian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, which became Nutrition and Dietetics,1989 ‐ Vol 64(4) 2007.

The references of all retrieved studies and reviews were searched for additional trials. Books relating to geriatric medicine and nutrition were searched. Authors of published trials, colleagues, and manufacturers of nutritional supplements were contacted for overlooked, unpublished and ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the present update, one reviewer (AA) carried out the search by scanning the titles, abstract sections and keywords of every record retrieved. Full articles were then retrieved for further assessment by two reviewers if the information given suggested that the study:

used random allocation to the comparison groups;

compared a protein and energy supplement with no intervention, a placebo or an alternative supplement;

involved participants who were over 65 years old;

assessed one or more relevant clinical outcome measure.

Articles were also retrieved if there was some doubt about eligibility. If necessary, trialists were contacted for further information on methodology and data. If no clarification had been provided, and there had been disagreement about eligibility for inclusion, the review group editorial base would have been consulted.

Data extraction and management

Information was independently extracted by two reviewers (either AA and AV or AM and JP). All differences in data extraction were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer, referring back to the original article.

Information gathered included:

location;

participant description;

inclusion and exclusion criteria;

details and duration of intervention;

baseline characteristics of the individuals studied;

participant flow;

relevant outcome measures recorded.

If any data were missing in a published report (see data extraction list), trialists were contacted for further information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality was assessed by two reviewers (either AA and AV or AM and JP) all differences were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer if necessary. A sensitivity analysis was carried out based on the quality assessment. The assessment protocol scored each item between nil and two as described below. In addition, risk of pre‐allocation disclosure of assignment was rated A, B or C according to the Cochrane Handbook 1997. The following aspects of internal and external validity was reported and assessed:

a) Was the assigned treatment adequately concealed prior to allocation? 2 = method did not allow disclosure of assignment (A) 1 = chance of disclosure of assignment or states random but no description (B) 0 = quasi‐randomised (C)

b) Were the outcomes of patients who withdrew included in the analysis (intention to treat)? 2 = intention to treat analysis based on all cases randomised possible or carried out 1 = states number and reasons for withdrawal but intention to treat analysis not carried out 0 = withdrawals not mentioned, intention to treat analysis not possible

c) Were the outcome assessors blinded to treatment status? 2 = action taken to blind assessors, or outcomes such that bias was unlikely 1 = chance of unblinding of assessors 0 = not mentioned

d) Were the treatment and control group comparable at entry? 2 = good comparability of groups, or confounding adjusted for in analysis 1 = confounding possible; mentioned but not adjusted for 0 = large potential for confounding, or not discussed

e) Were care programmes, other than the trial options, identical? 2 = care programmes identical 1 = differences in care programmes but unlikely to influence study outcomes 0 = not mentioned or differences in care programmes likely to influence study outcomes

f) Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined? 2 = clearly defined 1 = inadequately defined 0 = not defined

g) Were the interventions clearly defined (including estimates of nutritional value)? 2 = clearly defined interventions were applied with a standardised protocol 1 = clearly defined interventions were applied but the application protocol was not standardised 0 = intervention and/or application protocol were poorly or not defined

h) Were the participants blind to assignment status following allocation? 2 = effective action taken to blind subjects 1 = small or moderate chance of unblinding subjects 0 = not mentioned (unless double‐blind), or not done

i) Were the treatment providers blind to assignment status? 2 = effective action taken to blind treatment providers 1 = small or moderate chance of unblinding of treatment providers 0 = not mentioned (unless double‐blind), or not done

j) Was the overall duration of surveillance clinically appropriate? 2 = optimal (six months or more) 1 = adequate (one up to six months) 0 = not defined, or not adequate

Data synthesis

Data were combined for meta‐analysis for dichotomous variables mortality and number of patients with complications as described in the protocol. In those studies where the data were reported as the total number of complications instead of the number of affected patients, it was assumed that there was one outcome per patient. For each study relative risks and 95% confidence limits were calculated, the results were combined using fixed‐effect models and presented with 95% confidence limits. Where there was evidence of heterogeneity a random‐effects model was applied. Heterogeneity between comparable trials was explored using the I2 test (Higgins 2003) using more than 50% as the cut‐off for significant heterogeneity. A funnel plot to assess small study bias for mortality data was also carried out.

Data for length of hospital stay were combined for meta‐analysis as a continuous variable. Data were combined for meta‐analysis from studies which provided length of stay data as mean number of days and standard deviation. If the data were provided as the median and interquartile range, the median was used instead of the mean and the standard deviation estimated from the interquartile range. Weighted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a fixed‐effect model which assumes the same underlying effect in all studies and considers any heterogeneity between trials to be due to random errors. A random‐effects model was also used if there was any evidence of heterogeneity.

Data were also combined for meta‐analysis for percentage weight change and arm muscle circumference (AMC) and as described in the protocol. Weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using fixed‐ and random‐effects models as appropriate for changes in weight and anthropometry measures. The trials reported body weight and anthropometric measures in several ways. For meta‐analysis the same method was used to standardise data as used previously by Potter 1998. The mean and standard deviation of the percentage change in body weight during the trial period was selected as the measurement of choice because of its clinical relevance (Potter 1998). Where percentage weight change was not available the difference was calculated between the initial and final body weight, expressed as a percentage of baseline weight and a standard deviation of 10% inferred. This standard deviation was conservative, and at the upper limit of any of the observed results. As in Potter 1998, if baseline weight was not reported, a standard value of 60 kg was assumed, which applied to all patients regardless of their nutritional status. Assumptions made regarding standard deviations were checked by restricting the analysis to those trials where no inferences were made. As in Potter 1998, arm muscle circumference (AMC) was chosen as the anthropometry measure as it is both a measure of fat and muscle. Where this was not described in a trial it was derived from the mid‐arm circumference or mid‐upper arm circumference (MAC / MUAC) and triceps skinfold (TSF) using a standard formula (Gurney 1973). Anthropometry data were then pooled as weight data.

Data were also combined for meta‐analysis for change in handgrip strength where this was provided or could be calculated from the data provided. Weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals were again calculated using the fixed‐ and random‐effects model as appropriate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was carried out on the basis of:

baseline nutritional status (nourished, undernourished);

health status (healthy volunteers or ill patients);

mean age (less than 75 years, 75 years or more);

amount of kilocalories provided in supplement (less than 400 kcal, 400 kcal or more);

duration of intervention (less than 35 days, 35 days or more).

Additional post hoc subgroup analyses

As the result of comments resulting from the previous version of this review, additional subgroup analyses were carried out in order to provide a breakdown of the meta‐analyses on the basis of diagnostic group:

mortality by diagnostic group;

complications by diagnostic group;

length of hospital stay by diagnostic group;

percentage weight change by diagnostic group;

percentage arm muscle circumference change by diagnostic group.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were carried out in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analysis taking into account of study quality, as specified above.

repeating the analysis excluding a large study to establish how much it dominated the results.

repeating the analysis excluding studies using industry funding.

Results

Description of studies

In addition to the twenty‐one thousand titles / abstracts which were identified using the above database search strategies and through hand searching and reference list searching, in 2001, another twelve thousand titles / abstracts were identified for the 2005 update and an additional 28 studies identified for the present update (20 full reports, one ongoing study and seven abstracts). From the database search, reading the abstracts or reading the full article allowed most to be eliminated because they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. This left an additional 18 potentially relevant trials. Two reviewers independently assessed these trials and as a result of mutual agreement, 13 additional trials have been included to date (see Characteristics of included studies). The remaining were excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies) for a variety of reasons (for example no outcomes of interest, did not meet age or intervention criteria).

Contacts with authors

Requests for further information have been made. Of the 62 included trials, information on outcomes of interest and study quality was requested for 31 trials and has been obtained for 15 (Banerjee 1978; Brown 1992; Bruce 2003; Hankey 1993; Hankins 1996; Jensen 1997; Krondl 1999; Kwok 2001; Lauque 2000; MacFie 2000; Payette 2004; Potter 2001; Saudny 1997; Schols 1995; Yamaguchi 1998).

Trial design

Included studies were all randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials. The large study by Bourdel 2000 with 672 participants was cluster randomised and has not been included in the meta‐analysis, but the results have been included in the narrative part of the review. Young 2004 is also a cluster randomised crossover trial which following discussion with a statistician has been included in the meta‐analysis. Rosendahl 2006 is included in the meta‐analysis as it is clustered for exercise and individually randomised for supplementation.

Six of the included trials also examined the effects of exercise (Bonnefoy 2003; Daniels 2003; Fiatarone 1994; Meredith 1992; Rosendahl 2006; Schols 1995), with the same exercise component in both the supplemented and control groups. In the study by Bonnefoy 2003 a factorial design was used with participants receiving either exercise or memory training. In the study by Fiatarone 1994 there were sufficient data available to include the no exercise group only. In the studies by Schols 1995 and Tidermark 2004, groups of patients randomised to receive nandrolone decanoate has been excluded from the analysis. In the trial of surgical patients (Jensen 1997), there was an analysis of a subgroup of patients over 75 years, which has been used in this review.

Participants

A total of 10,187 randomised participants from the 62 trials has been included. Studies were carried out in Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and Hong Kong. Approximately 55% of participants were female (no information on gender was provided in seven studies). The mean age reported in studies varied from 65 to 88 years (not reported in seven studies). The number of participants in trials varied greatly between 10 (Brown 1992) and 4023 (FOOD trial 2005), 42 trials had fewer than 100 participants.

Although studies took place in a variety of settings, most participants (71%, 26 studies) were hospitalised in‐patients with acute conditions. Other participants were either in long‐stay / care of the elderly / continuing care wards or nursing homes (14%, 15 studies), or at home in the community (15%, 21 studies). Forty studies (48% participants) included older people with no specified disease or condition, except some trials where some or all patients had Alzheimer's disease. Other studies included patients with hip fracture (Brown 1992; Bruce 2003; Daniels 2003; Delmi 1990; Hankins 1996; Madigan 1994; Stableforth 1986; Tidermark 2004), stroke patients (FOOD trial 2005, Gariballa 1998), patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) (Broqvist 1994), patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Deletter 1991; Knowles 1988; Saudny 1997; Schols 1995; Steiner 2003, Vermeeren 2004), older surgical patients (Jensen 1997; MacFie 2000) and patients at home with diabetic foot ulcer (Eneroth 2004). Apart from diagnosis being considered as a marker of nutritional risk (for example post‐surgery, COPD, hip fracture), 60% of participants in the included trials underwent screening and were then classified as actually being undernourished or at nutritional risk. The definition for this (for example weight, BMI, unable to eat independently) varied between studies and was often not provided, very few studies used weight loss as an indicator of nutritional risk. Separate data were provided for those well nourished and undernourished in two studies (Larsson 1990; Potter 2001) and these have been analysed separately as appropriate in this review.

Interventions

The interventions used in the trials aimed to provide between 175 additional kcal/day and up to a maximum of 1350 additional kcal/day. Additional protein was between 10 g protein/day and 50 g protein/day. Less than 400 kcal/day was provided in 20 trials, 400 kcal/day or more in 32 trials, and the energy supplemented was not known for ten trials.

Thirty‐five trials reported using supplements with at least some vitamins and minerals, or both, one gave equivalent vitamins to the control group (Carver 1995), one also gave extra vitamins to some patients in a factorial design (Vlaming 2001), two trials gave calcium and vitamin D supplements to both the intervention and control group (Hampson 2003; Tidermark 2004), 27 trials did not report vitamin content or it was unclear, although the majority of commercial supplements do provide vitamins and minerals. MacFie 2000 had a control group and three groups receiving supplements (pre‐operative supplements only, post‐operative supplements only, and both pre and post‐operative supplements), those receiving supplements have been grouped together.

When reported, supplements were given twice daily for around 31% of participants, but this could also be between one and four times or any number of times for the remaining participants. Thirty‐nine trials used named commercial supplements, the others did not specify a manufacturer. Commercial supplements may have been provided by the manufacturer free of charge, although this was not often explicitly stated. Extra milk alone was provided for one study (Barr 2000), and low lactose milk powder was used in one study (Kwok 2001).

The minimum time period of the intervention was 10 days, the maximum was 18 months. The length of time of the intervention was less than 35 days for 17 trials, and 35 days or more for 37 trials, from admission to discharge in five trials and the intervention period was unclear for two trials. The duration of follow‐up was generally the same as the duration of the intervention, and varied from one week to 18 months.

Outcomes assessed

Most trials assessed nutritional outcomes, particularly weight change and dietary intake, but also change in anthropometry. Mortality was not the principle outcome for most trials. Morbidity and complications and length of hospital stay were provided in a limited number of trials. The majority of trials also included a measure of functional status, however these were often disease specific and too diverse for meta analysis. Sixteen studies measured the effect of supplementation on quality of life. Only one trial provided data on cost effectiveness (Edington 2004).

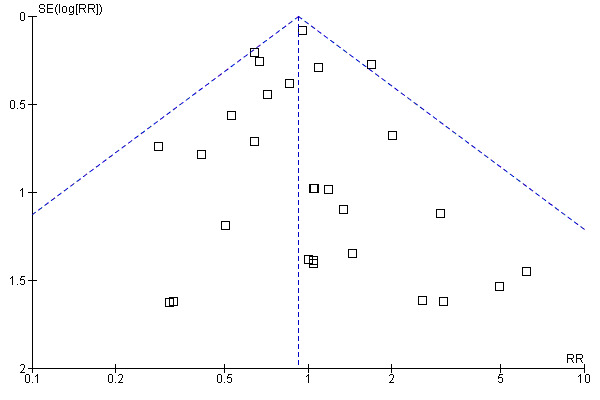

Funnel plot

The funnel plot of the comparison "oral protein and energy versus routine care ‐ outcome: mortality" appeared to be symmetrical (Figure 1).

1.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Oral protein and energy versus routine care, outcome: 1.1 Mortality.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details see Appendix 2. The method of scoring used is described above (quality assessment of trials). Concealment of allocation was confirmed in only 19 studies which used computer allocation or sealed opaque envelopes. A clear 'intention to treat' analysis was only carried out in 24 studies. The quality was poorest with regard to blinding. Action to ensure blinding of outcome assessors was reported in only 12 studies, action to blind participants in 16 studies, and blinding of treatment providers was reported in only 14 studies.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

Mortality

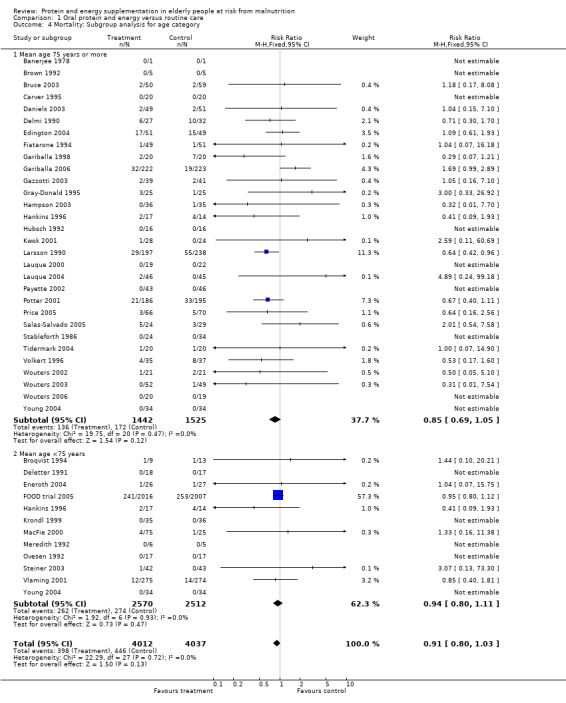

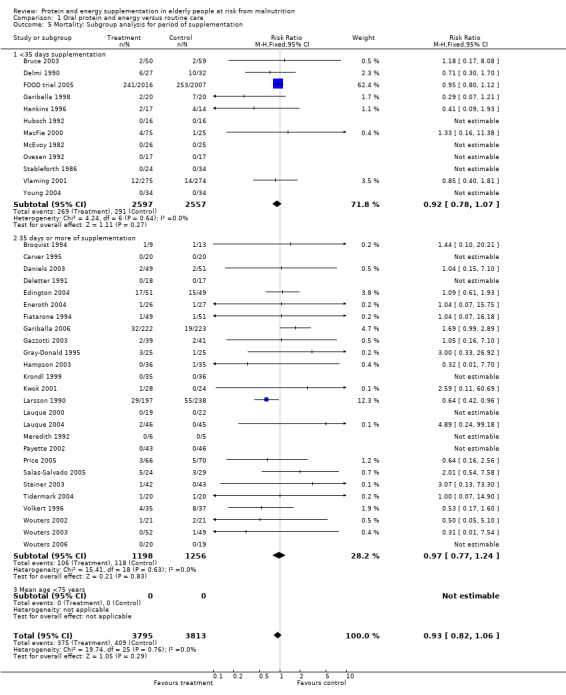

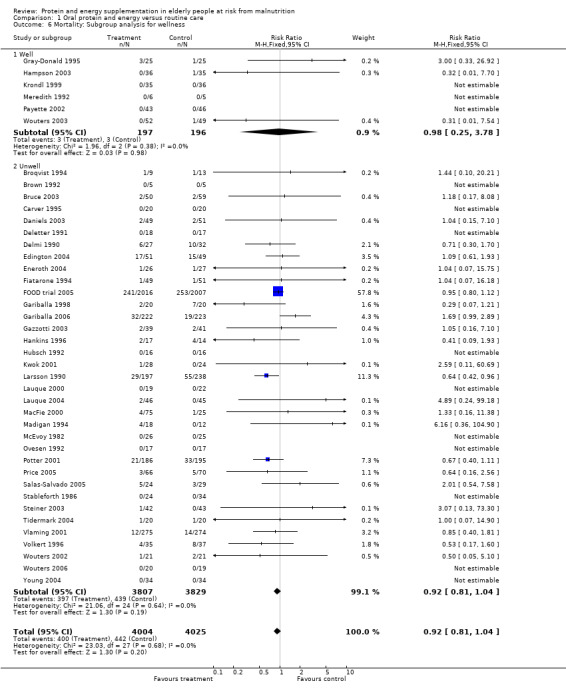

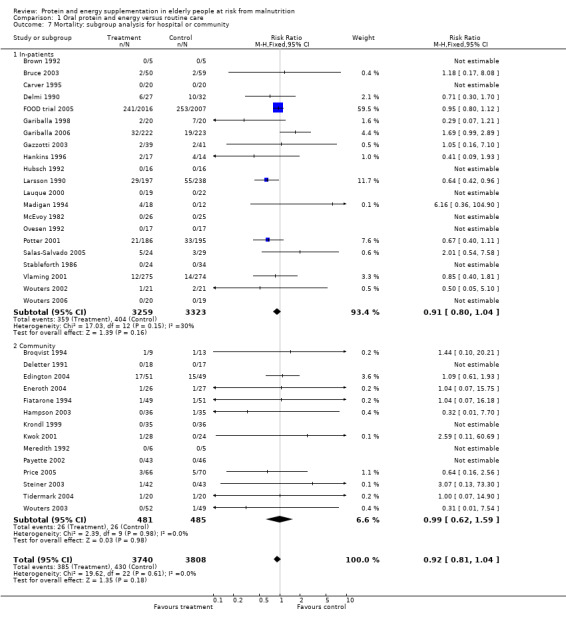

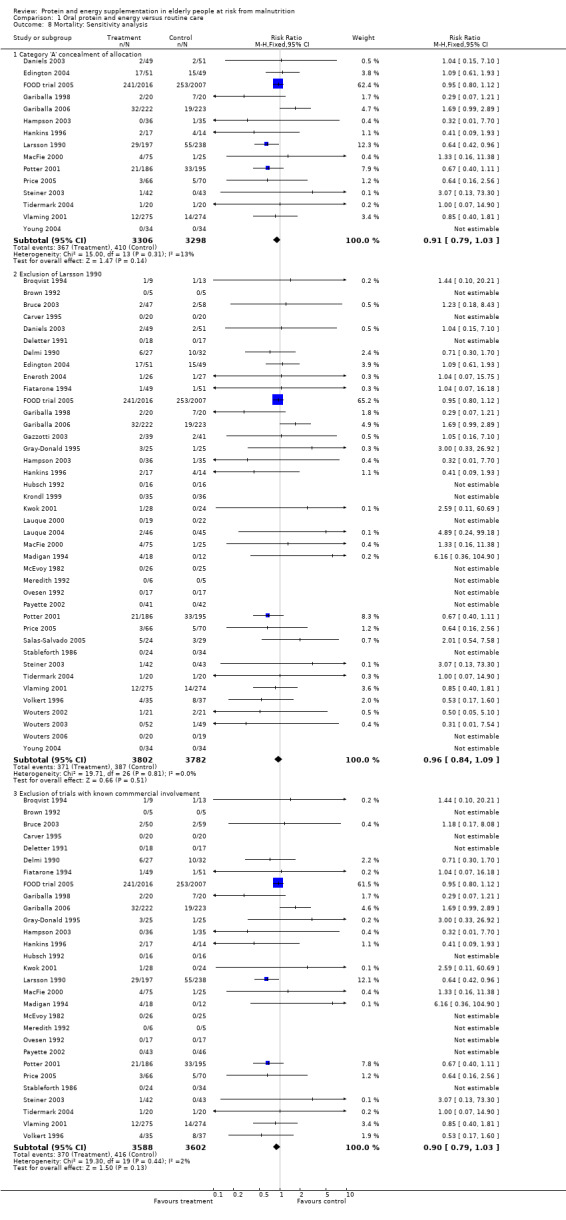

Deaths were reported in 50 trials. Data from Banerjee 1978; Bonnefoy 2003; Rosendahl 2006; Saudny 1997; Schols 1995; Woo 1994 and Wouters 2005, have been excluded as further clarification from the authors was not received. Data on mortality from Bourdel 2000 have been excluded from the meta‐analysis because the trial was cluster randomised, however Bourdel 2000 found no significant difference in the incidence of death during the 15 day follow‐up: 25 in the nutritional intervention group and 22 in the control group (P = 0.18). The relative risk by the end of follow‐up from the remaining 42 trials (8031 participants) did not show a reduced mortality in supplemented compared with control groups (relative risk (RR) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.04), with no significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The results of fourteen of these trials fall out of the analysis because the effect measure could not be calculated for zero events (no deaths).

Subgroup analyses

The subgroup analyses suggested that the results were statistically significant or approaching statistical significance when limited to trials in which participants (N = 2461) were defined as undernourished (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97), and when 400 kcal or more was offered per day in the supplement (N = 7307), (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.00).

Results were not significant, when analyses were limited to participants who were at least 75 years old (N = 2967), (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.05), when supplementation was continued for 35 days or more (N = 2454), (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.24), and when participants were unwell (N = 7636), (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.04), and when participants were in hospital or in a nursing home (N = 6582), (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.04), all with evidence of little heterogeneity.

The results of mortality were also not statistically significant when limited to trials when participants were not defined as undernourished (N = 5403), (RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.53 to 1.15 ‐ RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.14), when less than 400 kcal were offered per day in the supplement (N = 858), (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.98), participants were less than 75 years old (N = 8049 ‐ N = 5082), (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.03 ‐ RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.11), when supplementation was continued for less than 35 days (N = 5054), (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.07), when participants had not been defined as unwell (N = 393), (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.25 to 3.78), and when living in the community (N = 966), (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.62 to 1.59).

Sensitivity analyses

The results were consistent when analysis was restricted to 15 trials (N = 6604) with clearly concealed randomisation (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.03).

For six trials, there was co‐authorship with an employee of the manufacturer or full funding of the trial by a manufacturer of oral supplements (Edington 2004; Eneroth 2004; Krondl 1999; Lauque 2000; Lauque 2004; Salas‐Salvado 2005; Vermeeren 2004; Wouters 2002; Wouters 2003; Wouters 2006). The meta‐analysis of mortality data was also therefore carried out with the exclusion of these trials in order to explore the influence on effect size. Results with the remaining 29 trials, suggest that this had no demonstrable effect (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.03).

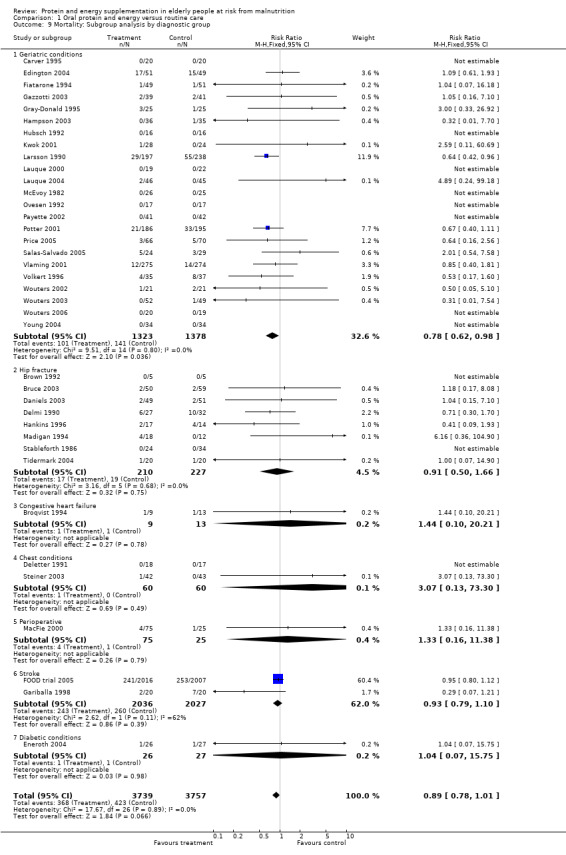

Post‐hoc subgroup analyses for mortality based on diagnostic group suggested that the results were statistically significant when including only trials in patients with a variety of geriatric conditions (N = 2701), (RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.98), where most of these participants were in hospital. However, there was no demonstrable benefit for patients with hip fracture (N = 437), (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.66) from eight small trials. The limited data from other diagnostic groups such as stroke patients and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) did not suggest a reduction in mortality.

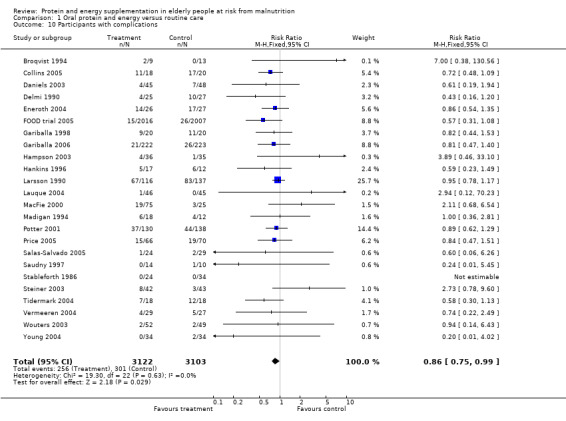

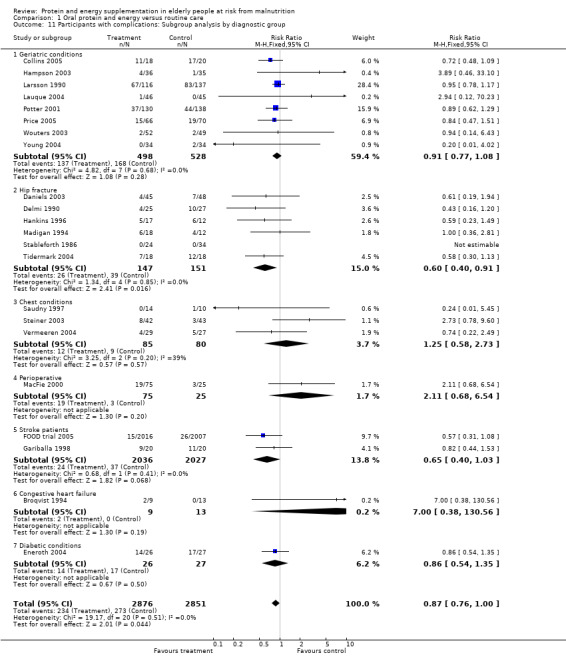

Morbidity

Data on morbidity were available from 28 trials. Data from Wouters 2005 were unsuitable for analysis without additional information from the authors. Data on development of pressure sores from Benati 2001 and Bourdel 2000 were also unsuitable for meta‐analysis. The results from Bourdel 2000 showed an increased risk of developing pressure ulcer in the control group versus the intervention group in 672 elderly patients (RR 0.57; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.38). Data from the remaining 24 trials (N = 6225), have been combined for meta‐analysis (Broqvist 1994; Delmi 1990; Gariballa 1998; Gariballa 2006; Potter 2001; Tidermark 2004 (infective complications); FOOD trial 2005; Hankins 1996; Larsson 1990 (total pressure sores); Hampson 2003; MacFie 2000; Madigan 1994; Saudny 1997; Wouters 2003 (patients too ill to continue used as a measure of complications); Steiner 2003 (exacerbation of COPD); Stableforth 1986 (anaesthetic, surgical infection, gastrointestinal, urinary); Daniels 2003; Lauque 2004; Vermeeren 2004; Young 2004 (hospital readmission); Collins 2005; Eneroth 2004; (incomplete wound healing); Price 2005 (prescription of antibiotics); Salas‐Salvado 2005 (total severe adverse events). Data on complications from Lauque 2000 have not been included because further clarification from the authors is required. The risk of complications by the end of follow‐up in supplemented groups was statistically significantly different from the control groups (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99), with no significant statistical heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses for complications based on diagnostic group suggested that there may be a reduced risk of complications with supplementation for hip fracture patients only (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.91).

Functional status

Functional status measures were very diverse, few were able to suggest any functional benefit with supplementation. One or more of the following measures of mobility were included in 14 studies: number of falls, activity rating, mobility, physical activity, walking, stair climbing, timed up and go (Bonnefoy 2003; Brown 1992; Deletter 1991; Fiatarone 1994; Gray‐Donald 1995; Hampson 2003; Larsson 1990; Madigan 1994; Payette 2004; Schols 1995; Saudny 1997; Steiner 2003; Tidermark 2004; Wouters 2003). In mixed groups of elderly people Gray‐Donald 1995 reported that the number of falls was lower among supplemented participants than controls (0% versus 21%; P = 0.05). Larsson 1990 reported a significant improvement in the activity rating in the supplemented group at eight weeks compared to the control group (P < 0.05) due mainly to improvement in the initially well nourished patients, however the number of patients studied was not clear. Muscle function and mobility were measured by Bonnefoy 2003, there was a short term improvement in quadriceps muscle power at three months with supplementation (56.8%; P = 0.03) but this was not sustained at nine months. Bonnefoy 2003 found no statistically significant effect on six meters walk, five time chair rise, or six stair climb at 3 and 6 months. Wouters 2003 also found no significant effect of supplementation on a timed 'up and go' test (Podsiadlo 1991), although Payette 2004 found a trend towards improvement in this test (P = 0.057).

In patients following hip fracture Madigan 1994 found that patients given supplements did significantly less well. The number of patients unable to reach goal two of physio‐independent mobility was significantly greater in the intervention group (5 versus 1; P < 0.01). Tidermark 2004 also failed to demonstrate any beneficial effect of supplementation on mobility in women with hip fracture. Hampson 2003 found no difference in level of physical activity in elderly community‐living women with osteoporosis given supplements.

Walking distance or velocity was assessed in four studies of patients with COPD, (Deletter 1991; Saudny 1997; Schols 1995; Steiner 2003) with no statistically significant improvement with supplementation reported, however a non significant trend towards improvement in 12 minute walking distance after nine weeks in the supplemented group compared to the control group was noted by Deletter 1991(65 m versus 16 m; P > 0.05). Activities of daily living (ADL) (Katz 1963; Mahoney 1965) was measured in 11 studies (Barr 2000; Bruce 2003; Gariballa 1998; Hankins 1996; Lauque 2004; Potter 2001; Tidermark 2004; Volkert 1996; Woo 1994; Wouters 2002; Wouters 2006). Overall only one study demonstrated a significant improvement at end of follow‐up. Woo 1994 reported a significant difference between the groups with a lower level of functional ability after three months in the control group in patients following chest infection (20 versus 19.5; P < 0.01). Tidermark 2004, however found an improvement at six months (P < 0.05) but no difference at 12 months (number of participants remaining independent 11/16 in the control group versus 14/17 in the intervention group (from graph)). Potter 2001 reported a significant improvement with supplementation only in a subgroup of very malnourished patients (17 versus 11; P < 0.04). Volkert 1996 found an improvement in the ADL score from admission to six months only in the subgroup with good acceptance of the supplement (72% versus 39%; P < 0.05). There was no improvement in frail elderly functional capacity (FEFA) in the study by Manders 2006.

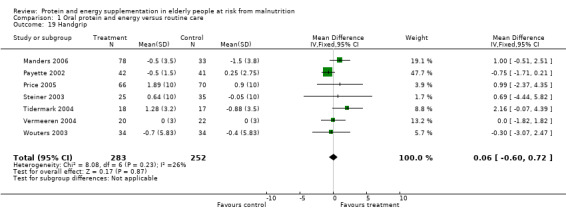

No statistically significant effect of supplementation was reported for hand grip strength in 13 studies (Edington 2004; Gray‐Donald 1995; Kwok 2001; Lauque 2000; MacFie 2000; Manders 2006; Payette 2002; Price 2005; Saudny 1997; Steiner 2003; Tidermark 2004; Wouters 2003; Vermeeren 2004). There was a trend towards improvement in grip strength for COPD patients in the study by Steiner 2003 (0.64 kg force versus ‐0.05; P = 0.06). There was also a trend towards short term improvement in the study by Edington 2004 after eight weeks (1.2 versus ‐0.5; P = 0.055) but with no difference at 24 weeks. Price 2005 reported that the intervention group (when analysed by intention‐to ‐treat) showed a greater increase in handgrip strength over 12 weeks compared to the control group which of borderline statistical significance (P = 0.055). Seven studies (Manders 2006; Payette 2002; Price 2005; Steiner 2003; Tidermark 2004; Wouters 2003; Vermeeren 2004) (535 participants) provided data on the change in handgrip which could be combined for meta‐analysis. Results suggest that supplementation had no demonstrable effect (weighted mean difference (WMD) 0.06; 95% CI ‐0.60 to 0.72).

There was no evidence of an improvement in dynamic strength (maximum weight lifted on a 'thigh‐knee' machine) (Meredith 1992), both the supplemented and control groups gained dynamic strength (P < 0.001) with no effect of diet. There was also no significant effect of the supplement on balance, gait or lower limb strength (Rosendahl 2006). Calf circumference was significantly improved at 24 weeks of supplementation in the study by Manders 2006.

Four studies involving older patients with COPD measured changes in lung function with supplementation. There was a statistically significant improvement in lung function [maximal inspiratory mouth pressure measured in kiloPascals (kPa)] in non tissue depleted patients with COPD between pre and post intervention, which was not seen in the control group (Schols 1995) (0.8 kPa versus 0.5 kPa; P < 0.05), but only in the first four weeks, and in Saudny 1997 forced vital capacity (percentage predicted) improved in the supplemented group as compared with the control group (8.7% versus ‐3.5%; P = 0.015). Deletter 1991 and Vermeeren 2004 however found no evidence of change in ventilatory performance in the supplemented group.

There was no evidence of an improvement in cognitive function between groups with supplementation (Collins 2005; Gariballa 2006; Lauque 2004; Salas‐Salvado 2005; Young 2004).

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life

Quality of life was ascertained using a variety of measures (general and disease specific well‐being and self perceived health questionnaires (for example SF36, hospital anxiety and depression score (HADS), Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), EQ5D and Self Reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire) in 16 studies (Barr 2000; Collins 2005; Edington 2004; FOOD trial 2005; Gariballa 2006; Price 2005; Hampson 2003; Krondl 1999; MacFie 2000; Payette 2002; Saudny 1997; Scorer 1990; Steiner 2003; Tidermark 2004; Woo 1994; Wouters 2002). Collins 2005 was unusable because result between groups was not reported. Gariballa 2006 reported SF36 in a subgroup of patients suggesting significant improvement in physical and social score. Hampson 2003 reported that more women 'felt better' in the supplemented group (48% versus 20%; P = 0.029). Saudny 1997 reported a greater improvement in well‐being in the supplemented group that was not statistically significant (12 points versus ‐10 points; P = 0.07). In the study by Edington 2004, although there was no effect on overall EQ5D score or for the visual analogue scale, the supplemented group reported fewer mobility problems at 24 weeks (P = 0.022). In the study by Krondl 1999, scores for vitality and general health perception increased more from baseline to termination in the supplemented group (P < 0.01), however it was not clear whether these were within or between group differences. No other meaningful between group differences were found.

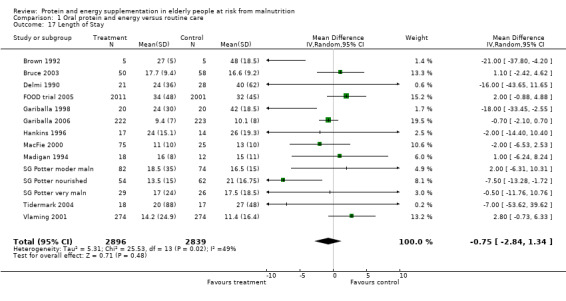

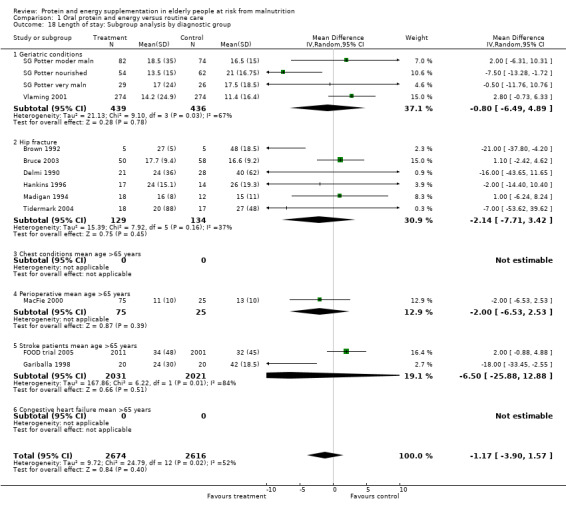

Length of hospital stay

Length of hospital stay was measured in 12 studies (Brown 1992; Bruce 2003; Delmi 1990; FOOD trial 2005; Gariballa 1998; Gariballa 2006; Hankins 1996; MacFie 2000; Madigan 1994; Potter 2001; Tidermark 2004; Vlaming 2001). Data were analysed separately for three groups in the study by Potter 2001(severely malnourished, moderately malnourished and adequately nourished). Data from Gazzotti 2003 require further clarification from the authors before inclusion. Data were combined for meta‐analysis from studies which provided length of stay data as mean number of days and standard deviation (SD) (Brown 1992; Bruce 2003; FOOD trial 2005; Gariballa 2006; Hankins 1996; Madigan 1994; Vlaming 2001), the SD was assumed to be 10 days in one study (MacFie 2000), based on the SDs for length of stay from the other studies. The median was used instead of the mean and SD estimated from the interquartile range for the four remaining studies (Delmi 1990; Gariballa 1998; Potter 2001; Tidermark 2004). The pooled weighted mean difference for length of stay using a random‐effects model showed no benefit from supplementation ‐0.8 days (‐2.8 to 1.3) with significant heterogeneity (chi‐square 25.53; df 13; P = 0.02; I2 = 49%). Subgroup analyses for length of stay were too limited to suggest any difference between diagnostic groups.

Adverse effects

Eighteen trials discussed adverse effects from supplementation, in most cases no comparison with the control group was performed, six reported no adverse effects (Delmi 1990; McWhirter 1996; Potter 2001; Saudny 1997; Tidermark 2004; Wouters 2002). Problems with tolerance and side‐effects were reported in 12 studies: Eneroth 2004 reported nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea in the intervention group. FOOD trial 2005 reported 28% stopped their supplements before discharge (refusal, weight gain, unwanted, nausea), Gariballa 2006 reported 20% nausea in both groups. Hankins 1996 reported dysphagia, nausea, diarrhoea and fatigue as reasons for drop‐out from the study in four out of 17 patients; Fiatarone 1994 reported diarrhoea in two out of 49 participants; Gazzotti 2003 reported loss of appetite, nausea or diarrhoea in five out of 39 patients; Price 2005 reported intolerance to supplements as reason for withdrawal in 20% of participants and significantly more gastro‐intestinal adverse events in the intervention group. Ovesen 1992 excluded ten out of 37 participants from the study because they refused to continue due to gastro‐intestinal discomfort attributed to the supplements; Vermeeren 2004 reported that nausea caused dropouts in three of 29 patients in the supplemented group and in one out of 27 patients in the control group. Stableforth 1986 stated that "intolerance of the supplements proved to be a handicap in correcting the deficits in many patients".

Nutritional status

Weight change

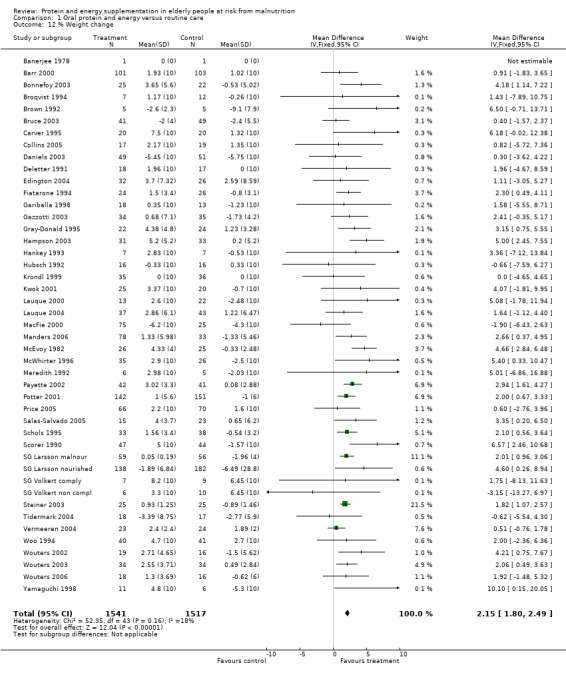

Measures of weight were converted into percentage weight change to allow data from 42 trials with 3058 participants to be included in the meta‐analysis. Percentage change in body mass index (BMI) was used as a proxy measure for weight in one study (Bonnefoy 2003). A standard deviation of 10% was assumed in 20 studies as described previously.

There was a mean weight loss during the trial period for the supplemented group in seven trials, this contrasts with a mean weight loss in 23 trials for the control group. The pooled weighted mean difference for percentage weight change showed a benefit of supplementation of 2.2% (1.8 to 2.5) with no significant heterogeneity (chi‐square 52.35; df 43; P = 0.16; I2 =17.5%). This would mean an average weight gain of 1.2 kg for a person weighing 55 kg.

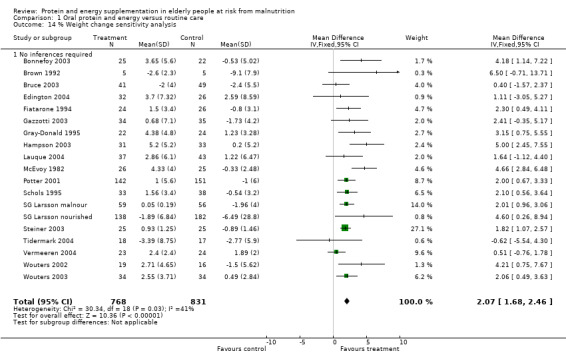

Sensitivity analysis of weight change data

When analysis was restricted to 18 trials where no inference was made regarding standard deviations the results remained consistent for weighted mean difference 2.1% (1.7 to 2.5).

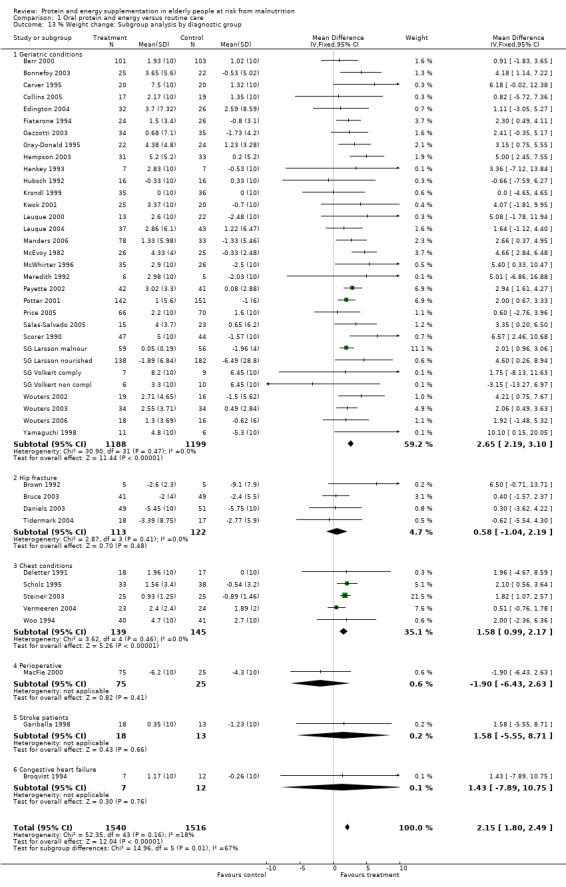

Subgroup analyses for weight change

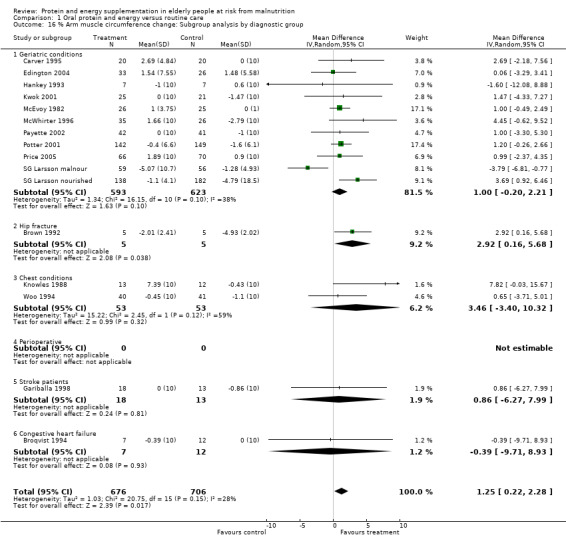

Subgroup analyses for weight change based on diagnostic group confirmed a significant increase in weight for mixed group of patients with geriatric conditions, weighted mean difference 2.7% (2.2 to 3.1), and for patients with chest conditions, weighted mean difference 1.6% (1 to 2.2). This could not be confirmed for other patient groups with the limited data available.

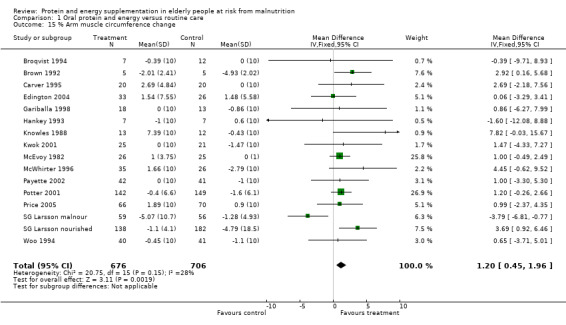

Arm muscle circumference (AMC)

Fifteen trials with 1382 participants reported a measure of AMC which was, or could be calculated from mid‐upper arm circumference and triceps skinfold thickness (Gurney 1973) and combined in a meta‐analysis. The pooled weighted mean difference for percentage AMC change using a fixed‐effect model showed a benefit of supplementation of 1.2% (0.5 to 2), with no significant heterogeneity (chi‐square 20.75; df 15; P = 0.15; I2 = 27.7%).

Subgroup analyses for percentage arm muscle circumference

Subgroup meta‐analyses for percentage AMC change based on diagnostic group were unable to confirm a statistically significant difference in AMC for any diagnostic group where more than one trial could be included.

Intake

Thirty‐two studies using a variety of methods for example dietary recall and weighed intake, reported that supplementation increased daily protein intake and energy intake, or both (Banerjee 1978; Barr 2000; Bourdel 2000; Broqvist 1994; Brown 1992; Deletter 1991; Delmi 1990; Edington 2004; Gariballa 1998; Gazzotti 2003; Hampson 2003 (within group change); Hankey 1993; Hankins 1996; Jensen 1997; Knowles 1988; Krondl 1999; Lauque 2000; MacFie 2000 (pre‐operative only); McWhirter 1996; Meredith 1992; Ovesen 1992; Payette 2002; Payette 2004; Potter 2001; Price 2005; Saudny 1997; Stableforth 1986; Steiner 2003 (within group change); Vermeeren 2004; Woo 1994; Yamaguchi 1998; Young 2004). Wouters 2003 reported no compensation of energy intake from usual diet had occurred with additional supplements. Volkert 1996 found that a statistically significant increase in protein intake during hospital stay was limited to 55% of patients in the intervention group with good acceptance of the supplement. In one study (Fiatarone 1994), supplementation was associated with significant reductions in total energy and protein from habitual diet, and energy intake was only significantly increased in exercising participants who also received nutritional supplementation. Six studies did not find that intake was significantly increased (Gray‐Donald 1995; Kwok 2001; Lauque 2004; Madigan 1994; Salas‐Salvado 2005, Wouters 2006), although reasons for this were not clear. Intake was not reported or not clear in the remaining 21 studies.

Compliance (acceptance of the supplement)

Acceptance was reported to be good in 17 studies although this was often not or variously defined (Barr 2000; Broqvist 1994; Carver 1995; Collins 2005; Delmi 1990; Fiatarone 1994; Gazzotti 2003; Krondl 1999; Kwok 2001; Lauque 2000; Lauque 2004; McWhirter 1996; Potter 2001; Rosendahl 2006; Steiner 2003; Vermeeren 2004; Wouters 2002). Bonnefoy 2003 reported 54% compliance at nine months, FOOD trial 2005 reported 76% compliance, Manders 2006 reported 67% compliance in the 111 out of 176 who completed the study. Payette 2002 found that 55% of participants were compliant at four months, Price 2005 reported 62% compliance overall, Scorer 1990 excluded patients who were unable to consume two cans supplement per day. Vlaming 2001 reported that 63% of 222 participants took 50% or more of the sip‐feed supplement in hospital and Wouters 2003 found no difference in compliance between the intervention and placebo products over six months: 85% (SD 36%) versus 94% (SD 24%) respectively. Bruce 2003 reported that poor compliance in patients after hip fracture had limited the effectiveness of the supplements despite encouragement and strategies offered by the dietitian (mean compliance 20.6/28 cans) due to 'taste problems'. Problems with acceptance were reported in the study by Gray‐Donald 1995, where 36% of potentially eligible participants refused to participate mainly because they did not wish to take a nutritional supplement; of those that did take part, compliance was realised by 68% (measured by counting supplements during a home visit on a weekly basis). Larsson 1990 found that 39 out of 197 patients refused the supplement and were withdrawn from the study and therefore not included in the analysis. Volkert 1996 reported data from 45% of participants who had poor acceptance of the supplements, but stated that "if taken they were well tolerated".

Other outcomes

Insufficient data were provided from these trials to examine other outcomes listed in the protocol, which included number of primary care contacts, level of care and support required. Edington 2004 measured heath care professionals services and social service costs over a period of 24 weeks following hospitalisation with or without eight weeks of supplementation of elderly malnourished patients on discharge from hospital. There was no reduction in health care costs with supplementation.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Supplementation appears to produce a small but consistent weight gain. There was no beneficial effect on mortality overall, but there was a reduction in mortality in undernourished groups and in general geriatric populations which were mainly hospitalised patients. There was a beneficial effect on the number of complications, particularly in hip fracture patients. There was no difference in the length of hospital stay. There was little evidence of benefit to functional outcomes or quality of life.The updated review was dominated by the large international FOOD trial 2005 which tested the hypothesis that adding oral protein‐energy supplements to standard hospital diet until discharge would improve outcome at six months after stroke. The trial contributed 4023 of the 10,187 randomised participants in this review, with only a minority (8%) of the FOOD trial 2005 participants classified as undernourished at baseline. The results of the trial suggest that it is unlikely that routine oral supplementation in well nourished stroke patients is useful. The trial did not answer the question about whether routine oral supplements may have a role to play in the management of undernourished patients.Care must be taken with the inclusion criteria for participants in order to achieve external validity. Trials ideally should have included a representative sample of elderly people who would under normal circumstances be eligible for oral nutrition support. Severely malnourished patients who are likely to benefit most have not been included in many trials for ethical reasons. Furthermore, many trials did not adequately screen participants for nutrition risk or malnutrition. The inclusion of marginal candidates for nutrition support in trials may mask the benefits of treatment (Wolfe 1997).

Mortality

The subgroup comparison of 'undernourished' versus 'not undernourished' was based on a definition of undernourished that was not the same for all trials. Unfortunately there were not enough data provided to stratify the subgroups using a standard measure of nutrition risk such as body mass index or recent weight loss. No single trial was adequately powered or long enough to investigate mortality as a primary outcome.

Morbidity, functional status and quality of life

The definition of complications was also not the same for all trials although most complications were infection related.

Few studies were able to provide data on improvements in functional status or quality of life in general, apart from handgrip data. Measures were too diverse or too limited to combine for meta‐analyses.

Length of stay

The FOOD trial 2005 with a slightly longer average stay for supplemented stroke patients dominated the results for the meta‐analysis of length of hospital stay with supplementation, although non significant, the trend is still towards a slightly shorter stay for supplemented patients.

Nutritional status

The pooled weighted mean difference for percentage weight change in this study showed a small but consistent benefit from supplementation, and there was no evidence that assuming a standard deviation in so many trials biased the results. The evidence from most trials suggested that supplements, if taken, produce weight gain. However we do not know the composition of that weight gain, which could be a gain in fat mass, muscle mass or both. In terms of providing functional benefit, a gain in fat mass may have cosmetic benefit but will not improve muscle strength. Results from Fiatarone 1994 suggested that exercise is also required to produce a significant improvement in muscle strength and function. Trials involving patients living at home provided supplements for periods of between six weeks and six months, with quite modest gains in weight. In the absence of more evidence of benefit for older people in the community, long‐term supplementation at home may not be cost‐effective.

The pooled weighted mean difference for percentage change in arm muscle circumference (which is a measure of both lean and fat tissue) in this study suggested a very small benefit of supplementation.

Intake

It has been suggested that nutritional supplementation may significantly reduce the intake of ordinary diet (Bastow 1983), and this obviously would reduce the effectiveness of supplements. However, the majority of studies reported that supplementation significantly increased total daily protein intake, energy intake or both. It should, however, be remembered that it is very difficult to measure nutrient intake with any degree of accuracy, and few assessors of intake were reported as being blinded to treatment status.

There was one notable exception to the findings above. Results of the trial by Fiatarone 1994 suggested that after 10 weeks of supplementation the supplemented participants did not increase their total energy intake significantly compared to the controls, despite high compliance with the supplements, which was offset by a reduction in normal food intake.

We also do not know yet which component(s) of the supplement may be providing the beneficial effect if any, specifically, whether it is actually the energy and protein that is important or the provision of extra vitamins and minerals from the supplement or all of these. Assessing this was made difficult because it was not clear in many studies whether vitamins and mineral were actually included in the supplements.

At least 10 trials also included some dietary advice as part of the intervention. Furthermore, participants at home received regular phone calls or visits. It is not known what influence this might have had, although it seems likely that this would improve compliance and outcomes. A recent systematic review of dietary advice alone to patients with illness related malnutrition (Baldwin 2008), would suggest that it is difficult to disentangle the different effects of advice and supplements.

Compliance (acceptance of the supplement)

The literature suggests that under normal conditions acceptance of supplements can be a problem for elderly people. This review does not include studies examining only the acceptability in terms of taste of different kinds of supplements for this age group. Problems with acceptance or adverse events such as nausea, gastro‐intestinal discomfort were reported in a few studies. From this review there was no evidence that participants at home were less compliant with supplementation than those in hospital or long term care.

Potential biases in the review process

The review was limited because the quality rating of included trials as reported was poor, particularly for blinding of outcome assessors, participants and treatment providers. Blinding of participants and treatment providers cannot be done without a placebo, and it can be difficult to have an untreated arm for ethical reasons in some trials. Without a placebo group bias may result from supplemented patients receiving a higher standard of care and attention from treatment providers. It should be possible however, to design a trial where the outcome assessors are blinded to the treatment allocation. The fact that this was only done (or at least reported) in 17 studies was a major deficiency of the review and may bias the results towards finding a more beneficial effect.

Analysis of outcomes on an 'intention‐to‐treat basis' was also deficient and this also potentially represents a source of bias. There was inadequate reporting of numbers of participants who were allocated and assessed, and reasons for losses to follow‐up were often not reported. Some patients were excluded from the analysis because they were unable or willing to take the supplements. If the outcomes from all patients had been included in the analysis, then the results would be more representative of the effectiveness of supplements under real life conditions.

The beneficial effect of supplementation on mortality was still evident when only higher quality trials with adequate allocation concealment were included, and also when trials with substantial proprietary involvement were excluded from the analysis. There was therefore no evidence that the commercial trials that did report on mortality, were more likely to report favourable outcomes. But there is a general concern that selective reporting of outcomes such as mortality, could have introduced bias.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of the present review, which included more than twice the number of patients than the previous version of this review, supports the findings of the previous review in that there is a small weight gain, but no longer supports the finding that there is a beneficial effect on mortality overall. However, mortality in undernourished patients may be reduced. There is more evidence of a reduction in complications than in the previous review. Results however still require to be substantiated as there are doubts due to many included trials having poor study quality.

Although proprietary sip feeds have become a widely accepted means of improving nutritional status, it is not enough to provide supplements and hope for the best. Under normal circumstances patients should have a variety of options for increasing intake. In hospital or long‐term care, at the very least, a choice of attractive and acceptable food should be offered along with dietary advice if required. Furthermore, elderly people may become more malnourished because they do not get assistance with feeding on a busy ward, and encouragement and assistance may be all that they require. There were too few randomised trials that had considered other methods of supplementation such as altering the nutrient density and diversity of the diet, which may be preferable to sip‐feeds for some elderly people, and also few trials which had tried to improve the way that the sip‐feeds were provided in order to improve acceptability and reduce wastage. However proprietary protein and energy supplements used appropriately with nutritionally 'at risk' patients have a useful role to play as part of a raft of measures which should be used to improve the intakes and nutritional status of older people in hospital or long‐term care.

For older people in the community who are at risk, it is also important to consider both dietary ways (for example meals‐on‐wheels) and non‐dietary ways (for example treatment of depression, correction of dental problems and exercise regimes) of improving intakes and nutritional status before they are admitted to hospital. More evidence of benefit from oral nutritional supplements for older people at risk of malnutrition in the community is still required.

Implications for research.

Large scale multi‐centre pragmatic trials of interventions to improve nutritional status of elderly people, particularly malnourished elderly people from clearly defined patient groups (such as patients with hip fracture) are still required. Most individual studies in this review had an intervention time that was too short to have a realistic chance of detecting differences in morbidity, functional status or quality of life. Future trials need to have sufficient statistical power and length of follow‐up to be able to detect any beneficial effects. Future trials of nutritional supplementation should also have properly concealed allocation, blinding and follow‐up of all participants to ensure that those who are not able to consume the supplements, are included (intention‐to‐treat analysis). Trials should also focus more on primary outcomes of relevance to patients such as improvement in function or quality of life measures.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 November 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The last updated and published review in November 2004 included 49 trials with 4790 randomised participants. Most trials had poor study quality. Results suggested a beneficial effect of supplementation for percentage weight change from 34 trials (weighted mean difference (WMD) 2.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 2.7) and a reduced mortality in the supplemented groups compared to the control groups from 32 trials (relative risk (RR) 0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 2.7). Sixty‐two trials with 10,187 randomised participants have been included in the current update. Most included trials had poor study quality. The pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) for percentage weight change showed a benefit of supplementation of 2.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8 to 2.5) from 42 trials. There was no significant reduction in mortality in the supplemented compared with control groups (relative risk (RR) 0.92, CI 0.81 to 1.04) from 42 trials. Mortality results were statistically significant when limited to trials in which participants (N = 2461) were defined as undernourished (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97). The risk of complications was reduced in 24 trials (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99). Few trials were able to suggest any functional benefit from supplementation. The WMD for length of stay from 12 trials also showed no statistically significant effect (‐0.8 days, 95% CI ‐2.8 to 1.3). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 October 2004 | New search has been performed | First update: New studies found and included or excluded: 4/1/04 Conclusions changed: 10/9/04 |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Christine Baldwin, Professor AK Banerjee, Dr Daniel Bunout, Dr Alison Kretser, Ann Coulston, Dr S Lauque, Diane Palmer, Mr J MacFie, Dr Catherine Hankey, Dr Katrina Brown, Professor Maria Krondl, Professor A Schols, Professor T Kwok, Professor J Woo, Dr MB Jensen, Elizabeth Weekes, Rosemary Price, Helga Saudny‐Unterberger, Jackie Edington, Dr D Bruce, Dr Hélène Payette and Dr Ian Cameron who took time to provide further information about the trials. Magnus McGee, Craig Ramsey and Marion Campbell for statistical advice and Dr Helen Handoll who was involved in the data extraction of trials included in this review from the review by Avenell 2004.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| Search terms |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms were free text terms; exp = exploded MeSH: Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); the dollar sign ($) stands for any character(s); the question mark (?) = to substitute for one or no characters; tw = text word; pt = publication type; sh = MeSH: Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); adj = adjacency.

MEDLINE 1. nutrition [MeSH, all subheadings included] 2. nutri* (textword) 3. maln* (textword) 4. undernutr* (textword) 5. under‐nutr* (textword) 6. undernourish* (textword) 7. under‐nourish* (textword) 8. protein‐energy malnutrition [MeSH, all subheadings included] 9. protein‐energy malnutrition (textword) 10. nutritional status [MeSH, all subheadings included] 11. nutrition disorders [MeSH, all subheadings included] 12. food,fortified [MeSH, all subheadings included] 13. food,formulated [MeSH, all subheadings included] 14. diet [MeSH, all subheadings included] 15. diet therap* (textword) 16. dietary supplements [MeSH, all subheadings included] 17. (diet* or nutri*) near supplement* (textword) 18. enteral nutrition [MeSH, all subheadings included] 19. dietary proteins [MeSH, all subheadings included] 20. energy intake [MeSH, all subheadings included] 21. randomized controlled trial.pt. 22. controlled clinical trial.pt. 23. randomized controlled trials.sh. 24. random allocation.sh. 25. double‐blind method.sh. 26. single‐blind method.sh. 27. or/1‐26 28. limit 27 to animal 29. limit 27 to human 30. 28 not 29 31. 27 not 30 32. clinical trial.pt. 33. exp clinical trials/ 34. (clinic$ adj25 trial$).tw. 35. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (mask$ or blind$)).tw. 36. placebos.sh. 37. placebo$.tw. 38. random$.tw. 39. research design.sh. 40. (latin adj square).tw. 41. or/32‐40 42. limit 41 to animal 43. limit 41 to human 44. 42 not 43 45. 41 not 44 46. comparative study.sh. 47. exp evaluation studies/ 48. follow‐up studies.sh. 49. prospective studies.sh. 50. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 51. cross‐over studies.sh. 52. or/46‐51 53. limit 52 to animal 54. limit 52 to human 55. 53 not 54 56. 52 not 55 57. 31 or 45 or 56 58. obesity [MeSH, all subheadings included] 59. critical care [MeSH, all subheadings included] 60. 58 or 59 61. or/1‐20 62. 61 not 60 63. 62 and 57 64. limit 63 to (newborn infant or infant <1 to 23 months> or preschool child <2 to 5 years> or child <6 to 12 years> or adolescence <13 to 18 years> or adult <19 to 44 years>) 65. 63 not 64 |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias

| Study | a) A/C b) ITT | c) assessor blind | d) comparability | e) identical care | f) in/exclusion | g) interventions | h) participant blind | i) carers blind | j) duration |

| Banerjee 1978 | 1 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Barr 2000 | 1 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Benati 2001 | 1 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonnefoy 2003 | 2 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bourdel 2000 | 1 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Broqvist 1994 | 1 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Brown 1992 | 0 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bruce 2003 | 0 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Carver 1995 | 0 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Collins 2005 | 1 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Daniels 2003 | 2 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Deletter 1991 | 1 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Delmi 1990 | 1 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Edington 2004 | 2 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |