Abstract

Background

Considerable controversy exists as to whether any benefit of doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy outweighs increased toxic effects, inconvenience, and additional costs, compared to single‐agent doxorubicin. There is substantial variation in clinical practice in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (STS).

Objectives

To determine: 1) the effect, if any on response rate or survival, by using doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy compared with single‐agent doxorubicin for the treatment of patients with incurable locally advanced or metastatic STS 2)if combination chemotherapy is associated with increased adverse effects compared with single‐agent doxorubicin in this setting.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (Cochrane Library, issue 4, 2002), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2002), CANCER LIT (1975 to October 2002), reference lists, the Physician Data Query (PDQ) clinical trials database, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting Proceedings (1995 to 2002).

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing single‐agent doxorubicin with doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy in adults with locally advanced or metastatic STS requiring palliative chemotherapy. Abstracts and full reports published in English were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

Data were abstracted and assessed by two reviewers. Response and survival data were pooled. Data on adverse effects was tabulated.

Main results

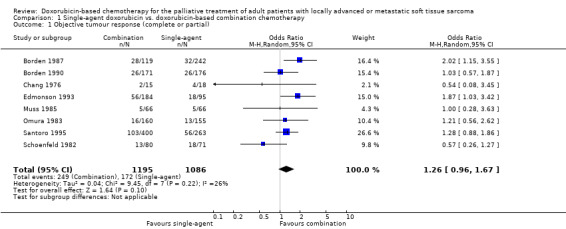

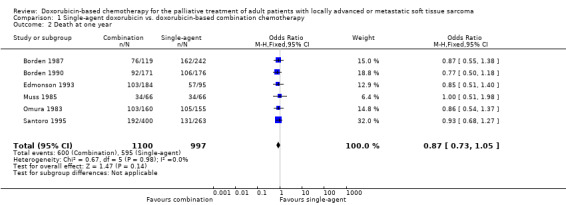

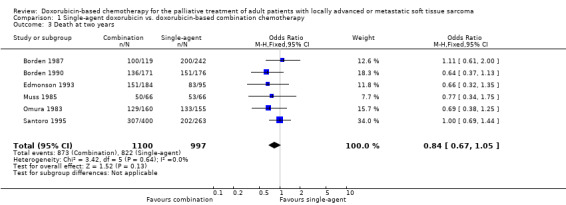

Data on 2281 participants from eight RCTs were available from reports of single‐agent doxorubicin versus doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy. Meta‐analysis using the fixed effect model detected a higher tumour response rate with combination chemotherapy compared with single‐agent chemotherapy (odds ratio [OR= 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 1.60; p = 0.03), but the OR from a pooled analysis using the random effects model and the same data did not achieve statistical significance (OR= 1.26; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.67; p = 0.10). No significant difference between the two regimens was detected in the pooled one‐year mortality rate (OR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.05; p=0.14) or two‐year mortality rate (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.06; p=0.13) (N=2097). Although reporting of adverse effects was limited and inconsistent among trials (making pooling of data for this outcome impossible), adverse effects such as nausea/vomiting and hematologic toxic effects were consistently reported as being worse with combination chemotherapy across the eight eligible studies.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to single‐agent doxorubicin, the combination chemotherapy regimens evaluated, given in conventional doses, produced only marginal increases in response rates, at the expense of increased toxic effects and with no improvements in overall survival.

Plain language summary

Additional chemotherapy with doxorubicin marginally improves tumour response but increases side effects with no improvement in survival

Doxorubicin is commonly used as palliative chemotherapy for patients with advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (cancer of muscle/tendon/fat/blood vessel). This review was conducted to find out if combining doxorubicin with other drugs is more effective than doxorubicin alone. Eight studies were considered together, which showed if combination chemotherapy is given: (1) tumour shrinkage was marginally better than in patients treated with doxorubicin alone; (2) survival was no different; and (3) side effects were worse than for patients treated with doxorubicin alone

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare tumours of mesenchymal origin and represent approximately one per cent of all adult cancers. They may occur anywhere in the body but have a particular predilection for the limbs (including the buttock and shoulders) and the retroperitoneal space. Histological classification and grading of soft tissue sarcomas, which can be difficult and controversial, has changed over time with the incorporation of new histochemical markers. However, the classification schema outlined in the textbook by Enzinger and Weiss is widely accepted (Enzinger 1995). Histological groups described in European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group protocols for adult soft tissue sarcomas (as described below) will be used for this systematic review.

Doxorubicin was first identified as an active agent in the treatment of adult soft tissue sarcomas in the 1970s. Response rates in early studies ranged from 9 to 70% (Pinedo 1977). More recently, large randomized multicentre studies have established response rates in the range of 16 to 27% for single bolus doses of doxorubicin given every three weeks (Chang 1976; Schoenfeld 1982; Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995) . Subsequently, dacarbazine (DTIC) and ifosfamide (IFOS) were identified as active agents, with single‐agent response rates of 18% (Buesa 1991) and 18 to 36% (Stuart‐Harris 1983; Bramwell 1987; Antman 1989), respectively. A large number of other drugs have been evaluated, but these had minimal or inconsistent activity in patients with soft tissue sarcomas (Demetri 1995).

Various combinations of the active drugs have been evaluated in a number of nonrandomized studies with documented response rates in the range of 35 to 60%, generally at the expense of greater toxicity (Bramwell 1991; Demetri 1995). Combination chemotherapy regimens not containing doxorubicin have consistently yielded poor results in adult patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (Yap 1981; Schoenfeld 1982; Spielmann 1988). Results from large randomized studies comparing doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy regimens with single‐agent doxorubicin regimens have been more varied (Chang 1976; Schoenfeld 1982; Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995). In some of these trials, response rates have been higher in the combination chemotherapy arms, whereas in others, primary outcomes have not been significantly different between the treatments (Omura 1983; Borden 1990; Santoro 1995).

Thus, there is considerable controversy as to whether any added benefit of combination chemotherapy outweighs increased toxic effects and inconvenience to patients, as well as the additional costs to health care systems. This has led to substantial variation in clinical practice. The Sarcoma Disease Site Group (DSG) felt that an unbiased, systematic review of the evidence was warranted.

Objectives

1. To determine if there is an advantage, in terms of response rate or survival, in using doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy compared with single‐agent doxorubicin for the palliative treatment of patients with incurable locally advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma.

2. To determine if combination chemotherapy is associated with increased toxic effects compared with single‐agent doxorubicin in this setting.

The use of adjuvant chemotherapy is not covered in this review, but has been the subject of an individual‐patient‐data meta‐analysis (SMAC 1997) and a separate systematic review and practice guideline developed by the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative (Figueredo 2000).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials that were published in English and compared single‐agent doxorubicin with a doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy regimen.

Types of participants

At least 90% of trial participants met the following criteria:

1. Adult patients (i.e. older than 15 years of age) with locally advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma who were candidates for palliative chemotherapy.

2. Eligible histological types including the following: alveolar soft part sarcoma, angiosarcoma / lymphangiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, neurogenic sarcoma, pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, unclassifiable sarcoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, miscellaneous sarcomas including uterine (mixed mesodermal, leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma).

3. The following tumour types were excluded: bone sarcomas (e.g.., osteosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, chondrosarcoma), embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, malignant mesothelioma, neuroblastoma.

Types of interventions

Doxorubicin alone versus any doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

1. Tumour response rate (complete and partial responses) 2. Progression‐free survival (PFS) 3. Overall survival (OS) 4. Adverse effects 5. Quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

We originally searched MEDLINE (1966 through June 1999) and CANCERLIT (1975 through June 1999). We also searched EMBASE from 1979 to 1995 using the truncated keywords, "random" and "sarcoma" and scanned citation lists and personal files for additional studies. The Physician Data Query (PDQ) clinical trials database on the Internet (http://www.cancer.gov/search/clinical_trials/) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting Proceedings (1995‐1999) were also searched for additional reports of completed or ongoing trials. No further attempt was made to find reports of unpublished randomized controlled trials. Relevant articles and abstracts were selected and assessed by two reviewers (VB, DA), and the reference lists from these sources were searched for additional trials.

The original literature search has been updated using CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library issue 4, 2002), MEDLINE (through October 2002), CANCERLIT (through October 2002), and the proceedings of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (2000 to 2002).

MEDLINE, CANCERLIT and CENTRAL were searched through Ovid, using the following search strategy: 001 random:.sh,tw,pt. 002 (double‐blind method: or single‐blind method:).sh,tw. 003 prospective: stud: .sh,tw. 004 multicent: stud: .sh,tw. 005 placebos/ 006 or/1‐5 007 (doxorubicin or adriamycin) .sh,tw. 008 combin: .tw. 009 7 and 8 010 exp sarcoma/ 011 sarcoma:.mp. 012 (soft and tissue: and sarcoma:).mp. 013 or/10‐12 014 9 and 13 015 14 and 6

Data collection and analysis

Trial reports were assessed and data were abstracted by two reviewers (VB and DA). Studies were assessed for adherence to the following quality criteria: method of randomization, description of statistical methods and inclusion of sample size calculations.

Objective tumour response and mortality data from all eligible trials were pooled, in order to calculate overall estimates of treatment efficacy. The meta‐analysis was based on data abstracted or estimated from the text, tables and figures in published papers. These data included the numbers of patients in each treatment group who experienced a complete or partial tumour response, died within one year of randomization, died within two years of randomization and were randomly allocated to the treatment. Death rates for single‐agent and combination chemotherapy were compared at one year and two years after randomization. We used specific time points rather than other measures of survival, such as Hazard Ratios, because it was not possible to generate Kaplan Meier curves from the published data. In patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, median overall survival is nine to twelve months. The early time point for survival analyses was chosen to be close to the expected median. By the second time point, at least 75% of deaths should have occurred. For trials with more than one doxorubicin‐based single‐agent or combination chemotherapy arm, data from all relevant groups in the trial were combined for the meta‐analysis. Toxicity data were not combined, as the outcomes and measures varied greatly among studies.

For both response and death, the pooled result is expressed as an odds ratio (OR), which is the odds of an event occurring in the experimental group (combination chemotherapy) divided by the odds of an event occurring in the control group, (single‐agent doxorubicin), and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For death, odds ratios greater than 1.0 favour single‐agent therapy and estimates less than 1.0 favour combination therapy. For response, odds ratios less than 1.0 favour single‐agent therapy and estimates greater than 1.0 favour combination therapy. Both the random effects and fixed effect model were considered. The results of the random effects model are reported in the text below, as the more conservative estimate of effect (DerSimonian 1986). The Q‐test was used to measure the quantitative heterogeneity among study results.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on trials that included a combination of doxorubicin with at least one other known active agent for soft tissue sarcoma (i.e. ifosfamide or DTIC) in their regimens.

Results

Description of studies

Eight randomized controlled trials that compared doxorubicin combination chemotherapy with single‐agent doxorubicin met the eligibility criteria (Chang 1976; Schoenfeld 1982; Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995) (Table 1). No eligible studies were excluded from the systematic review. The trials ranged in size from 33 (Chang 1976) to 749 randomized patients (Santoro 1995). In five studies central pathology review was performed for a majority of tumours (Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Edmonson 1993). Some analysis of delivered dose of relevant drugs was performed in four studies (Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995).

1. RCTs ‐ Doxorubicin combination chemotherapy.

| Study | Tumour type | Chemotherapy | Regimens* | Evaluable Patients |

| Chang & Wiernik, 1976 (4) NCI (US) | Adult STS (4 bone sarcomas) 4 prior chemo | DOX DOX STREPT | 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 500 mg/m2 IV bolus d1‐5 | 18 (17) 15 (14) |

| Schoenfeld et al, 1982 (5) † ECOG | Adult STS (18 bone sarcomas, 9 mesotheliomas) 3 prior chemo | DOX DOX VCR CYCLO | 70 mg/m2 IV bolus 50 mg/m2 IV bolus 1.4 mg/m2 IV bolus 750 mg/m2 IV bolus | 71 (66) 80 (70) |

| Omura et al, 1983 (6) GOG | Uterine sarcomas 31 prior chemo | DOX DOX DTIC | 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 250 mg/m2 IV bolus d1‐5 | 155 (120) 160 (106) |

| Muss et al, 1985 (7) GOG | Uterine sarcomas | DOX DOX CYCLO | 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 500 mg/m2 IV bolus | 66 (50) 66 (54) |

| Borden et al, 1987 (8) ECOG | Adult STS | DOX DOX DOX DTIC | 70 mg/m2 IV bolus 20 mg/m2 d1,2,3 IV bolus, then 15 mg/m2/wk 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 250 mg/m2 IV bolus d1‐5 | 123 (94) 119 (88) 119 (92) |

| Borden et al, 1990 (9) ECOG | Adult STS | DOX DOX VND | 70 mg/m2 IV bolus 70 mg/m2 IV bolus 3 mg/m2 IV bolus | 176 (151) 171 (147) |

| Edmonson et al, 1993 (10) ECOG | Adult STS (4 bone sarcomas) | DOX DOX IFOS DOX MITC DDP | 80 mg/m2 IV bolus 60 mg/m2 IV bolus 3.75 g/m2 IV 4 hrs x 2 days 40 mg/m2 IV bolus 8 mg/m2 IV bolus 60 mg/m2 IV bolus | 95 (90) 94 (88) 90 (84) |

| Santoro et al,1995 (11)EORTC | Adult STS | DOX DOX VCR CYCLO DTIC DOX IFOS | 75 mg/m2 IV bolus 50 mg/m2 IV bolus 1.5 mg/m2 IV bolus 500 mg/m2 IV bolus 750 mg/m2 IV 30 mins 50 mg/m2 IV bolus 5 g/m2 CIV 24 hrs | 263 (240) 142 (134) 258 (231) |

| Footnote: | ||||

| CYCLO = cyclophosphamide | ||||

| DDP = cisplatin | ||||

| DOX = doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | ||||

| DTIC = dacarbazine | ||||

| ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | ||||

| EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer | ||||

| GOG = Gynecologic Oncology Group | ||||

| IFOS = ifosfamide | ||||

| MITC = mitomycin | ||||

| NCI = National Cancer Institute | ||||

| STREPT = streptozotocin | ||||

| STS = soft tissue sarcoma | ||||

| VCR = vincristine | ||||

| VND = vindesine | ||||

| * all doses given every three weeks, unless otherwise stated | ||||

| † third arm: vincristine, Actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide. | ||||

Data on tumour response, survival, nausea and vomiting, and hematologic toxicity were reported for all eight trials. Two papers provided very limited data on adverse effects (Schoenfeld 1982; Omura 1983) , and only two papers provided detailed tabular reports of toxic effects seen in multiple systems (Borden 1990; Santoro 1995). Because the number of patients randomized to each treatment group was not reported, the number of eligible patients was used for the meta‐analysis for one trial (Santoro 1995). Progression‐free survival was not reported consistently across studies. Quality of life was not addressed in any of the studies included in this review.

There were nine single‐agent doxorubicin arms (1086 total patients entered) in the eight studies. One study contributed data from two single‐agent doxorubicin arms (Borden 1987). Each study included an arm in which high‐dose single‐agent doxorubicin was given every three weeks. In three studies the dose was 60 mg/m2 (Chang 1976; Omura 1983; Muss 1985), in another three studies, 70 mg/m2 (Schoenfeld 1982; Borden 1987; Borden 1990), and in one study each it was 75 mg/m2 (Santoro 1995) and 80 mg/m2 (Edmonson 1993). In one study (Borden 1987), there was an additional arm in which doxorubicin (20 mg/m2 daily x 3) was administered as a loading dose followed by 15 mg/m2 weekly.

There were ten doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy regimens given in eight studies (1195 total patients entered). The dose of doxorubicin in combination with other agents was 40 mg/m2 in one study (Edmonson 1993), 50 mg/m2 in two studies (Schoenfeld 1982; Santoro 1995), 60 mg/m2 in five studies (Chang 1976; Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Edmonson 1993), and 70 mg/m2 in one study (Borden 1990); in each case treatment was repeated every three weeks. The doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin with vindesine (Borden 1990), streptozotocin (Chang 1976), cyclophosphamide (Muss 1985), ifosfamide (Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995), DTIC (Omura 1983; Borden 1987), mitomycin‐C and cisplatin (Edmonson 1993), vincristine and cyclophosphamide (Schoenfeld 1982), and vincristine, cyclophosphamide and DTIC (Santoro 1995).

Although a few patients who had received previous chemotherapy were included in the earlier studies (Chang 1976; Schoenfeld 1982; Omura 1983), most patients were chemotherapy‐naive at study entry. Similarly, the majority had adult soft tissue sarcoma; although a few bone sarcomas and mesotheliomas were included in three studies (Chang 1976; Schoenfeld 1982; Edmonson 1993). All the trials excluded from their analysis some randomized patients who were subsequently found to be ineligible, as well as a variable number of patients who were not evaluable for survival and a larger number who were not evaluable for response.

No eligible ongoing trials were identified.

Risk of bias in included studies

Only randomized trials were included in this systematic review. The trials were published between 1976 and 1995. In general, later reports included more details about study methods, particularly statistical analysis. Four studies described a satisfactory (central office) method of randomization (Schoenfeld 1982; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Santoro 1995), and four studies included an outline of the statistical methods employed for analysis (Omura 1983; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Santoro 1995). However, in only two papers were accrual goals set and met (Borden 1990; Santoro 1995). The studies conducted by Chang et al and Muss et al were of inadequate size to properly evaluate differences in response rate or survival (Chang 1976; Muss 1985). Although response criteria were described or referenced in all except one study report (Schoenfeld 1982), it is generally accepted that the quality of evaluation of response has improved over the past 20 years because of better imaging techniques and attention to quality‐control procedures. Thus, the results reported in later studies may be more reliable.

Overall, we did not feel that there were a sufficient number of trials in which the quality exceeded the remainder to justify a sensitivity analysis based on study quality.

Effects of interventions

Tumour response

Response rates for single‐agent doxorubicin ranged between 16% and 27% (Table 2). Response rates for combination chemotherapy ranged from a low of 14% for doxorubicin and streptozotocin (Chang 1976) to 34% for doxorubicin and ifosfamide (Edmonson 1993). Response rates were significantly better for the combination chemotherapy regimens in only two trials. In one study (Borden 1987), the combination of doxorubicin and DTIC was superior to doxorubicin (p=0.03), given by two different schedules; in the second study (Edmonson 1993), the combination of doxorubicin and ifosfamide was superior to single‐agent doxorubicin (p=0.03). In one study (Schoenfeld 1982), response rate was significantly better on doxorubicin compared with the combination of doxorubicin/vincristine/cyclophosphamide (p=0.03). Objective tumour response data were available for pooling from all eight trials, providing eight comparisons with a total of 2281 patients. There was no significant numerical heterogeneity among studies for objective tumour response (chi square = 9.45, p = 0.22). The pooled analysis for response (comparison 1.1) detected a difference favouring combination therapy with the fixed effect model (OR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.60; p = 0.03) but not with the random effects model (OR = 1.26; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.67; p = 0.10). When the meta‐analysis was restricted to the four trials using combination regimens of known active agents (Omura 1983; Borden 1987; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995), this difference was more pronounced (OR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.95; p = 0.002 with both models).

2. Response rates and median survival times.

| Study | Treatment | Evaluable patients | Responders | Med. surv. (months) |

| Chang & Wiernick, 1976 (4) | DOX DOX/STREPT | 17 14 | 4 (24) 2 (14) p=NS | 10.2 10.6 |

| Schoenfeld et al, 1982 (5) | DOX DOX/VCR/CYCLO | 66 70 | 18 (27) 13 (19) p=0.03* | 8.5 7.8 |

| Omura et al, 1983 (6) | DOX DOX/DTIC | 120 106 | 13/80 (16) 16/66 (24) p=NS | 7.7 7.3 |

| Muss et al, 1985 (7) | DOX DOX/CYCLO | 50 54 | 5/26 (19) 5/26 (19) p=NS | 11.6 10.9 |

| Borden et al, 1987 (8) | DOX q 3 wk DOX loading then weekly DOX/DTIC | 94 88 92 | 17 (18) 15 (17) 28 (30) p=0.03† | 8.0 8.4 8.0 |

| Borden et al, 1990 (9) | DOX DOX/VND | 151 147 | 26 (17) 26 (18) p=NS | 9.4 9.9 |

| Edmonson et al, 1993 (10) | DOX DOX/IFOS DOX/MITC/DDP | 90 88 84 | 18 (20) 30 (34) 27 (32) p=0.03† | 8.4 11.5 9.4 |

| Santoro et al, 1995 (11) | DOX DOX/VCR/CYCLO/DTIC DOX/IFOS | 240 134 231 | 56 (23) 38 (28) 65 (28) p=NS | 12.0 11.8 12.7 |

| Footnote: | ||||

| CYCLO = cyclophosphamide | ||||

| DDP = cisplatin | ||||

| DOX = doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | ||||

| DTIC = dacarbazine | ||||

| IFOS = ifosfamide | ||||

| MITC = mitomycin | ||||

| NS = not significant | ||||

| STREPT = streptozotocin | ||||

| VCR = vincristine | ||||

| VND = vindesine | ||||

| * Single‐agent doxorubicin better than combination chemotherapy | ||||

| † Doxorubicin combination chemotherapy better than single‐agent doxorubicin. |

Survival

Median survival ranged from 7.7 to 12.0 months with single‐agent doxorubicin ranged and 7.3 to 12.7 months with combination chemotherapy (Table 2). None of the studies detected any significant differences in survival between single‐agent doxorubicin and combination chemotherapy. Overall survival data for pooling were extracted directly from survival curves for six of the eight trials (Omura 1983; Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995), with a total of 2097 patients. In two trials, survival data either were not reported (Chang 1976), or could not be extracted (Schoenfeld 1982). There was no significant numerical heterogeneity among studies for one‐year (chi square = 0.67, p = 0.98) or two‐year mortality (chi square = 3.42, p = 0.64). Pooled analysis of mortality data across six studies did not detect a statistically significant difference between single‐agent and combination doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy at one year (OR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.05; p=0.14 with the random effects model) (comparison 1.2) or at two years (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.05; p=0.13 with the random effects model) (comparison 1.3); results with the fixed effect model were almost identical (p = 0.13 at one year and 0.14 at two years). The conclusions of the meta‐analysis did not significantly change when the data were restricted to the four trials using combinations of known active agents (Omura 1983; Borden 1987; Edmonson 1993; Santoro 1995) (mortality OR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.09; p = 0.3 at one year; OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.16; p = 0.4 at two years; with both models).

Adverse effects

Reporting of adverse effects was quite variable among the eight eligible trials, but all reported data on nausea/vomiting and hematological toxic effects (Table 3). As all these studies were performed before the widespread use of 5HT3‐antagonists, nausea and vomiting were reported frequently. With the exception of the study reported by Borden and colleagues (Borden 1990), rates of nausea and vomiting were always greater for combination regimens, often significantly so. Hematologic toxic effects were reported in different ways among studies. Sometimes leucopenia and thrombocytopenia were reported separately, sometimes in combination. In many of these studies, nadir blood counts were not necessarily performed and hematological toxicity may have been under‐reported. As with nausea and vomiting, the rate of hematologic toxicity of combination chemotherapy was always higher than with single‐agent doxorubicin. Neutropenic fever and other toxic effects, such as mucositis., were not reported consistently. Although the more recent studies did report toxic deaths (Muss 1985; Borden 1987; Borden 1990; Santoro 1995), these were uncommon. Reporting of cardiotoxicity was highly variable and it was impossible to determine whether this was worse for single‐agent or combination regimens; ultimately, it depended on the individual dose of doxorubicin received by each patient.

3. Toxic effects.

| Study | Treatment | Nausea & vomiting | WBC | Platelet count | Haematologic |

| Chang & Wiernick, 1976 (4) | DOX DOX + STREPT | 59% mild/mod 100% mod/severe | WBC <2000 9% 30% (p<0.01) | PLATS <100,000 3% 13% (p<0.03) | ‐ |

| Schoenfeld et al, 1982 (5) | DOX DOX/VCR/CYCLO | 42% mod/severe 60% mod/severe (p=0.09) | ‐ | ‐ | 17% severe 30% severe (p=0.07) |

| Omura et al, 1983 (6) | DOX DOX/DTIC | Grade 3/4 2.2% 8.5% | Grade 3/4 16% 35% | Grade 3/4 4% 13% | ‐ |

| Muss et al, 1985 (7) | DOX DOX/CYCLO | 0% severe 6% severe | WBC <2000 10% 35% | PLATS<50,000 0% 0% | ‐ |

| Borden et al, 1987 (8) | DOX q 3 wk DOX loading q/wk DOX/DTIC | 11% severe 6% severe 29% severe (p=0.00003) | ‐ | ‐ | 28% severe 13% severe 29% severe (p=0.87) |

| Borden et al, 1990 (9) | DOX DOX/VND | 6% severe 3% severe | ‐ | ‐ | 36% severe 50% severe |

| Edmonson et al, 1993 (10) | DOX DOX/IFOS DOX/MITC/DDP | 7% severe 18% severe 17% severe | ‐ | ‐ | 53% 80% 55% (p=0.01) |

| Santoro et al, 1995 (11) | DOX DOX/VCR/CYCLO/DTIC DOX/IFOS | Grade 3/4 17% 40% NR | Grade 4 13% 15% 32% (p<0.001) | Grade 3/4 4% 10% 6% | ‐ |

| Footnote: | |||||

| DOX=doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | |||||

| STREPT=streptozotocin | |||||

| VCR=vincristine | |||||

| CYCLO=cyclophosphamide | |||||

| DTIC=dacarbazine | |||||

| VND=vindesine | |||||

| WBC = white blood cell | |||||

| IFOS=ifosfamide | |||||

| MITC=mitomycin | |||||

| DDP=cisplatin | |||||

| NR = not reported |

Discussion

Potential flaws of these studies include insufficient patient numbers for reliable statistical analysis and variability in pathological interpretation. A number of authors have suggested that response to chemotherapy may vary with histological subtype, but there are discrepancies between studies in identifying the most and least responsive histologies. The EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group has established the most extensive database that has been subjected to central histopathological review (van Glabbeke 1999). Van Glabbeke et al reported on 2,185 patients with advanced STS treated in seven clinical trials investigating the use of anthracycline‐containing regimens as first‐line chemotherapy. Univariate analysis showed increased survival times for patients with liposarcoma and synovial sarcoma, decreased survival times for patients with malignant fibrous histiocytoma and a higher response rate for patients with liposarcoma (p<0.05 for all log‐rank and chi square tests). Multivariate analysis, however, identified a diagnosis of liposarcoma as the only favourable prognostic factor for response rate among the pathological subtypes (p=0.0065).

The main limitation of the present review is the fact that a number of different doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy regimens have been compared with doxorubicin. Four of the eight studies compared combinations that included drugs considered to have limited activity as single‐agent regimens in advanced soft tissue sarcoma (i.e. vincristine, vindesine, cyclophosphamide, streptozotocin, mitomycin‐C, cisplatin). Even the four studies that used the known active agents in combination with doxorubicin (i.e. ifosfamide and DTIC) produced mixed results. Thus, the response rate for doxorubicin plus DTIC was better than that for doxorubicin alone in one study (Borden 1987) and similar in another study (Omura 1983). For doxorubicin plus ifosfamide, the response rate was better than for doxorubicin alone in the study reported by Edmonson and colleagues (Edmonson 1993), but similar in the EORTC study reported by Santoro and colleagues (Santoro 1995). A meta‐analysis of these four trials did detect a significant difference between single‐agent doxorubicin and combination chemotherapy in terms of tumour response but not survival. The three‐drug combination of doxorubicin, DTIC and ifosfamide (MAID) has never been directly compared with doxorubicin alone. However, a randomized study did detect a superior response rate with MAID compared with the combination of doxorubicin and DTIC (32% vs. 17%, p<0.002) but with increased myelosuppression and no improvement in overall survival (Antman 1993). Since the publication of these studies, no new active drugs have been identified in soft tissue sarcoma.

In virtually all of the reviewed studies, the toxicity of combination chemotherapy (particularly nausea and vomiting, and myelosuppression) exceeded that of single‐agent doxorubicin. It can be argued that modern anti‐emetics and growth factor support might reduce or eliminate these differences, but in the setting of palliative chemotherapy, the costs of such strategies (particularly with granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor [G‐CSF]) must be weighed against the expected benefits.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Combinations of the known active drugs used at conventional doses can produce marginal increases in response rate in advanced metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, at the expense of increased adverse effects, but do not significantly increase survival rates. Thus, the results of this review favour the use of single‐agent doxorubicin for palliative treatment of advanced/metastatic soft tissue sarcoma.

Implications for research.

Future randomized clinical trials should compare new regimens, whose activity has been established in single‐arm studies, with single agent doxorubicin. Future trials should include quality of life as an outcome measure.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 January 2019 | Review declared as stable | This review will be superseded by 'First‐ and second‐line systemic treatments for metastatic and locally advanced soft tissue sarcomas in adults'. The protocol was published in October 2016 (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012383/full). Full review expected 2019. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 7 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 29 August 2006 | New search has been performed | The literature search as described in the search strategy sections was updated on 29 September 2006. No new relevant studies were found. |

| 27 July 2001 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This systematic review formed the basis for a clinical practice guideline developed by the Sarcoma Disease Site Group of the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative. It has been converted to a Cochrane review. It should be noted that for the purposes of the guidelines, the authors were requested to search only for studies published in English. The complete guideline report may be found on the web at: www.cancercare.on.ca/english/home/toolbox/qualityguidelines/diseasesite/sarcoma‐ebs/sarcoma‐dsg/

Acknowledgements

*Robert Bell, Charles Catton, Jordi Cisa, Jane Curry, Aileen Davis, C. Jay Engel, Alvaro Figueredo, Victor Fornasier, Lorraine Hands, Brian O'Sullivan, Shailendra Verma, Rebecca Wong, Caroline Zwaal also contributed to the development of this systematic review. Please see the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative (CCOPGI) web site for a complete list of current Sarcoma Disease Site Group members: www.cancercare.on.ca/english/home/toolbox/qualityguidelines/diseasesite/sarcoma‐ebs/sarcoma‐dsg/

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Single‐agent doxorubicin vs. doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Objective tumour response (complete or partial) | 8 | 2281 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.96, 1.67] |

| 2 Death at one year | 6 | 2097 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.73, 1.05] |

| 3 Death at two years | 6 | 2097 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.67, 1.05] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Single‐agent doxorubicin vs. doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy, Outcome 1 Objective tumour response (complete or partial).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Single‐agent doxorubicin vs. doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy, Outcome 2 Death at one year.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Single‐agent doxorubicin vs. doxorubicin‐based combination chemotherapy, Outcome 3 Death at two years.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Borden 1987.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 361 randomized 275 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox q 3 weeks Dox weekly Dox + DTIC |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity PFI | |

| Notes | Two single‐agent doxorubicin arms included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Borden 1990.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 347 randomized 298 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + vindesine |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity PFI | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chang 1976.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 33 randomized 31 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + streptozotozin |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Edmonson 1993.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 279 randomized 262 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + ifosfomide Dox + mitomycin + CDDP |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity | |

| Notes | Two dox‐based combination arms included | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Muss 1985.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 132 randomized 104 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + cyclo |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity PFI | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Omura 1983.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 315 randomized 226 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + DTIC |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Santoro 1995.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 749 randomized 663 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + ifosfamide CYVADIC |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity PFI | |

| Notes | Two dox‐based combination arms included CYVADIC arm closed early |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Schoenfeld 1982.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 151 randomized 136 evaluable | |

| Interventions | Dox Dox + cyclo + vincristine |

|

| Outcomes | Response Survival Toxicity PFI | |

| Notes | Third arm not included ‐ did not contain dox | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

CDDP, cisplatin; cyclo, cyclophosphamide; CYVADIC, cyclophosphamide/vincristine/doxorubicin/dacarbazine; dox, doxorubicin; DTIC, dacarbazine; PFI, progression‐free interval; RTC, randomized controlled trial

Contributions of authors

The primary reviewer is Vivien Bramwell. Dale Anderson and Manya Charette also contributed to the development of the systematic review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Cancer Care Ontario, Canada.

External sources

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care, Canada.

Declarations of interest

Members of the Sarcoma Disease Site Group were asked to disclose potential conflict of interest related to this systematic review. There was no known conflict of interest.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Borden 1987 {published data only}

- Borden EC, Amato DA, Rosenbaum C, Enterline HT, Shiraki MJ, Creech RH, et al. Randomized comparison of three adriamycin regimens for metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1987;5:840‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borden 1990 {published data only}

- Borden EC, Amato DA, Edmonson JH, Ritch PS, Shiraki M. Randomized comparison of doxorubicin and vindesine to doxorubicin for patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1990;66:862‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chang 1976 {published data only}

- Chang P, Wiernik PH. Combination chemotherapy with adriamycin and streptozotocin. I. Clinical results in patients with advanced sarcoma. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1976;20:605‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edmonson 1993 {published data only}

- Edmonson JH, Ryan LM, Blum RH, Brooks JSJ, Shiraki M, Frytak S, et al. Randomized comparison of doxorubicin alone versus ifosfamide plus doxorubicin or mitomycin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin against advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1993;11:1269‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muss 1985 {published data only}

- Muss MB, Bundy B, DiSaia J, Homesley HD, Fowler WC, Creasman W, et al. Treatment of recurrent or advanced uterine sarcoma: A randomized trial of doxorubicin versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (a phase III trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group). Cancer 1985;55:1648‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Omura 1983 {published data only}

- Omura GA, Major FJ, Blessing JA, Sedlacek TV, Thigpen JT, Creasman WT, et al. A randomized study of adriamycin with and without dimethyl triazenoimidazole carboxamide in advanced uterine sarcomas. Cancer 1983;52:626‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Santoro 1995 {published data only}

- Santoro A, Tursz T, Mouridsen H, Verweij J, Steward W, Somers R, et al. Doxorubicin versus CYVADIC versus doxorubicin plus ifosfamide in first‐line treatment of advanced soft tissue sarcomas: A randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1995;13:1537‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schoenfeld 1982 {published data only}

- Schoenfeld DA, Rosenbaum C, Horton J, Wolter JM, Falkson G, DeConti RC. A comparison of adriamycin versus vincristine and adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide versus vincristine, actinomycin‐d and cyclophosphamide for advanced sarcoma. Cancer 1982;50:2757‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Antman 1989

- Antman KH, Ryan L, Elias A, Sherman D, Grier HE. Response to ifosfamide and mesna: 124 previously treated patients with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1989;7:126‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Antman 1993

- Antman K, Crowley J, Balcerzak SP, Rivkin SE, Weiss GR, et al. An Intergroup phase III randomized study of doxorubicin and dacarbazine with or without ifosfamide and mesna in advanced soft tissue and bone sarcomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1993;11:1276‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bramwell 1987

- Bramwell VHC, Mouridsen HT, Santoro A, Blackledge G, Somers R, Verwey J, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus ifosfamide: Final report of a randomized phase II trial in adult soft tissue sarcomas. European Journal of Cancer & Clinical Oncology 1987;23:311‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bramwell 1991

- Bramwell VH. Chemotherapy for metastatic soft tissue sarcomas ‐ another full circle?. British Journal of Cancer 1991;64:7‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buesa 1991

- Buesa JM, Mouridsen HT, Oosterom AT, Verweij J, Wagener T, Steward W, et al. High dose DTIC in advanced soft tissue sarcomas in the adult. A phase II study of the EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Annals of Oncology 1991;2:307‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Demetri 1995

- Demetri GD, Elias AD. Results of single agent and combination chemotherapy for advanced soft tissue sarcomas: implications for decision making in the clinic. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America 1995;9:765‐85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials 1986;7:177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Enzinger 1995

- Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft Tissue Tumours. Third Edition. St. Louis, USA: Mosby, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Figueredo 2000

- Figueredo A, Bramwell VHC, Bell R, Davis AM, Charette M and the members of the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Sarcoma Disease Site Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy following complete resection of soft tissue sarcoma. Data on file. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Pinedo 1977

- Pinedo HM, Kenis Y. Chemotherapy of advanced soft‐tissue sarcomas in adults. Cancer treatment reviews 1977;4:67‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SMAC 1997

- Sarcoma Meta‐analysis Collaboration. Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft‐tissue sarcoma of adults: meta‐analysis of individual data. The Lancet 1997;350(9092):1647‐54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spielmann 1988

- Spielmann M, Sevin D, Chevalier T, Subirana R, Contesso G, Genin J, et al. Second line treatment in advanced sarcomas with vindesine (VDS) and cisplatin (DDP) by continuous infusion (CI) [abstract]. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1988;7:276. Abstract 1072. [Google Scholar]

Stuart‐Harris 1983

- Stuart‐Harris RC, Harper PG, Parsons CA, Kaye SB, Mooney CA, Gowing NF, et al. High dose alkylation therapy using ifosfamide infusion with mesna in the treatment of adult advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Chemotherapy & Pharmacology 1983;11:69‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van Glabbeke 1999

- Glabbeke M, Oosterom A, Oosterhuis J, Mouridsen H, Crowther D, Somers R, et al. Prognostic factors for the outcome of chemotherapy in advanced soft tissue sarcoma: An analysis of 2,185 patients treated with anthracycline‐containing first‐line regimens ‐ a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1999;17:150‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yap 1981

- Yap B‐S, Benjamin RS, Burgess MA, Murphy WK, Sinkovics JG, Bodey GP. A phase II evaluation of methyl CCNU and actinomycin D in the treatment of advanced sarcomas in adults. Cancer 1981;47:2807‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Bramwell 2000

- Bramwell VHC, Anderson D, Charette ML. Doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy for the palliative treatment of adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic soft‐tissue sarcoma: a meta‐analysis and clinical practice guideline. Sarcoma 2000;4(3):103‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]