Abstract

Introduction.

The development and initial assessment in a clinical setting of a theory-driven, individually tailored educational application (app), MomsTalkShots, focused on increasing uptake of maternal and infant vaccines is described.

Methods.

MomsTalkShots algorithmically tailored videos based on parent needs to deliver an intervention that was specifically responsive to individual vaccine attitudes, beliefs and intentions, demographics, and source credibility. MomsTalkShots was evaluated among 1,103 pregnant women recruited from 23 geographically and socio-demographically diverse obstetrician-gynecologist offices in Georgia and Colorado in 2017. Self-reported information needs were assessed pre-and post-videos and participants self-reported factors related to usability and analyzed in 2018.

Results.

The vast majority of women reported MomsTalkShots was helpful (95%), trustworthy (94%), interesting (97%) and clear to understand (99%), none of which varied by demographics or parity. Reported usability was slightly lower among vaccine hesitant women, yet the majority reported MomsTalkShots was helpful (91%), trustworthy (85%), interesting (97%) and clear (99%). The majority of women (72%) who did not have enough vaccine information pre-videos reported enough information post-videos.

Conclusions.

MomsTalkShots was designed to provide individually tailored vaccine information to pregnant women from a population with varied vaccine intentions, confidence and vaccine concerns. MomsTalkShots was extremely well-received among pregnant women, even among women who were initially vaccine hesitant and did not intend to vaccinate themselves and their infants according to the recommended immunization schedule. Next steps include evaluation to assess impact on vaccine uptake and expansion to adolescent and adult vaccines.

Vaccine hesitancy - concerns about vaccinating oneself or one’s child(ren) – threatens vaccination programs in the United States (US) and globally.1 Vaccine refusal has led to widespread outbreaks of measles in Europe including more than 82,000 cases and 72 deaths in 2018.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) named vaccine hesitancy as a top ten threat to global health in 2019.3 Increasingly, American parents are delaying and refusing vaccines leading to outbreaks of preventable diseases4–12 like the measles outbreak that started in Disneyland in 2015 and ongoing outbreaks in Oregon, Washington and New York. The most recent population-based US data on parental vaccine attitudes and beliefs suggest that more than 7 in 10 parents have concerns such as (not mutually exclusive): too many vaccines given at one doctor visit (36%) or in the first two years of life (34%), that vaccines may cause conditions such as autism (30%), and that vaccine ingredients are unsafe (26%).13

Interventions addressing vaccine hesitancy have focused on providers and patients including, at the patient-level, written educational information (brochures, pamphlets, posters), PowerPoint presentations, and a web-based decision aid but studies have found no convincing evidence of effective interventions to address parental vaccine hesitancy.14–15 A randomized controlled trial found a web-based social media intervention that included interaction with vaccine experts targeting pregnant women showed a modest improvement in vaccine attitudes and uptake.16–17 However, implementation of this intervention may be challenging given the need for access to highly specialized clinical and epidemiological vaccine expertise. Correcting vaccine misinformation and emphasizing the risks of vaccine preventable diseases, in isolation of more comprehensive approaches, potentially backfires among hesitant parents.18

At the provider-level, a presumptive approach framing vaccination as the default option and Motivational Interviewing have shown promise in improving vaccine uptake.19–22 Relying mainly on clinicians to educate parents about vaccination and to address their concerns is simply not working given the high prevalence of parental vaccine concerns. Ideally patients could discuss immunization with health care providers but, in reality, there is little time during patient visits for questions, dialogue, and decisions about vaccination. The time burden has been reported as a barrier to vaccine discussions; many parents with concerns requiring 10–19+ minutes of discussion.26 Early child visits require consultation on a number of issues and counseling for vaccines is time-intensive and not billable to health insurance. Some pediatricians reported considering stopping providing vaccinations given the financial loss now equated with vaccine administration.27 Medicaid reimbursement for vaccine administration, $2–18 to cover ordering, handling, storage, administration, record keeping and counseling, is inadequate, particularly considering counseling time.28

Patient-level interventions to address vaccine hesitancy are needed. However, a one-size-fits-all approach to patient-level vaccine education is unlikely to be effective and risks being counter-productive given the complexity of immunization decision-making and wide variability in parental vaccine attitudes and beliefs. The WHO recommends “messages need to be tailored for the specific target group, because messaging that too strongly advocates vaccination may be counterproductive, reinforcing the hesitancy of those already hesitant.” 15 There is little work on tailored, patient-centered, scalable and low-cost interventions. Cross-sectional surveys in the US and Australia have used audience segmentation to profile parents based upon their vaccine attitudes, beliefs and intentions. Parents generally fall into five vaccine groups/profiles: 1) Immunization Advocates who actively seek vaccination, 2) Go Along to Get Along who follow the advice of their doctors and perceived social norms to vaccinate, 3) Cautious Acceptors who vaccinate but with caution, 4) Fence-Sitters who are very uncertain in their vaccine decisions, and 5) Refusers who actively reject some or all vaccines.23–29

Segmenting parents allows for tailoring interventions though, to our knowledge, tailoring vaccine educational interventions based upon audience segmentation has not been widely used outside of conversations between providers and parents. Interventions need to be cautious to not raise concerns that do not already exist, particularly among Immunization Advocates and Go Along to Get Along parents who have few concerns. Cautious Acceptors and Fence-Sitters are the most important to target to overcome concerns and accept timely vaccination. Among Cautious Acceptors and Fence-Sitters, concerns vary as previously characterized by cross-sectional surveys.13 Parents who actively refuse vaccines have largely already made up their minds and are thus very challenging, although they may agree to at least some vaccines to their children.25

The growth of maternal vaccination affords the opportunity to address both maternal and infant vaccination during pregnancy. Pregnancy can be used as a “teachable moment” when expectant parents are eager for information to ensure the health of their infant. Especially among first-time mothers, vaccine attitudes and beliefs may not yet be fully formed making them well suited for educational interventions. Since 2016, approximately half of pregnant women received influenza and/or pertussis vaccination.30

Our theory-driven individually tailored educational application (app) targeting pregnant women, MomsTalkShots, focused on increasing uptake of maternal and infant vaccines and sustaining changes in vaccine attitudes and beliefs. MomsTalkShots is the patient-component of a larger intervention that also included provider- and practice-level interventions.31 The impact of MomsTalkShots for these outcomes is being evaluated through a cluster randomized controlled trial and will be reported when outcomes data are available. We describe usability of and patient satisfaction with MomsTalkShots and changes in self-reported vaccine information needs after use of the app.

MomsTalkShots

In the waiting room, participants were given a tablet with the MomsTalkShots app. MomsTalkShots begins with a short questionnaire to capture patient-level, socio-demographics and vaccine attitudes, beliefs and intentions and to measure behavioral change or for tailoring the intervention. Questions from the short version of the Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccine survey (PACV-SF)32 were modified to identify hesitant parents without creating concerns that do not already exist. For example, only patients who indicated they were not confident in the safety of vaccines were asked about serious side effects, the timing of vaccines, and vaccine ingredients.

MomsTalkShots offers various videos with introductions from obstetricians and pediatricians of different ethnicities as well as animation to communicate messages in an engaging and interesting manner. The approach takes advantage of current research on vaccine decision-making, effective communication strategies, and behavioral theory to persuade parents to accept vaccines.33 MomsTalkShots is rooted in theoretical behavioral constructs including risk perception (severity and susceptibility to disease), vaccine efficacy, empathy, and self-efficacy. These constructs were chosen based on team discussions, pre-testing, literature review, and formative research. Tailoring to each parent’s existing vaccine knowledge and beliefs was also guided by the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM),34 a model of persuasive communication and behavior change that postulates that messages are evaluated along a continuum.

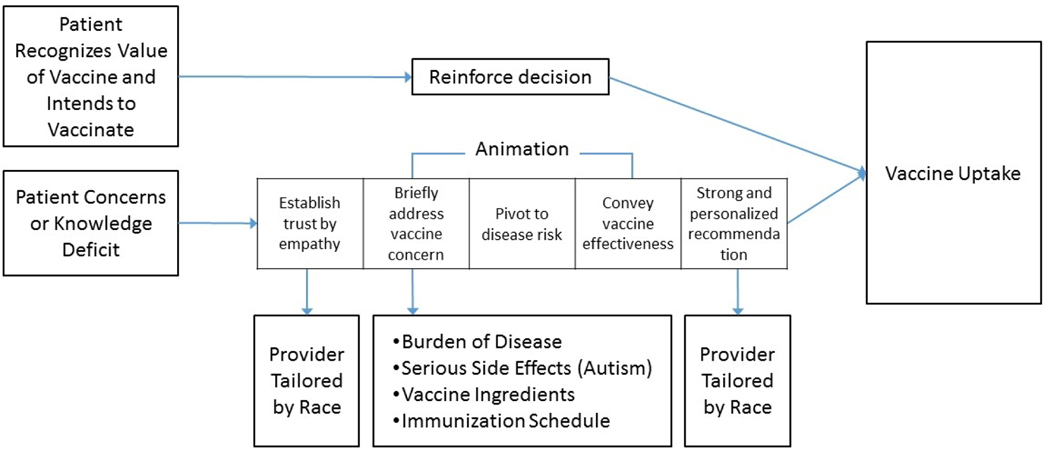

MomsTalkShots algorithmically tailored videos based on survey responses to be specific to parents’ vaccine attitudes, beliefs and intentions, demographics, and source credibility (Figure 1). Combined video length for each participant ranged from 9 to 17 minutes depending on how many videos were assigned. If only assigned 3 videos, 9 minutes; if assigned all 6, 17 minutes. Videos averaged 3 minutes in length. About half of pregnant women and mothers have very favorable vaccine attitudes and intend to follow their doctor’s advice; these women receive only a short video reinforcing the value of timely vaccination. MomsTalkShots is careful to do no harm with this segment of the population. MomsTalkShots is tailored to address vaccine concerns or lack of familiarity with the diseases.

Figure 1:

MomsTalkShots Audience Segmentation and Tailoring

Among mothers with vaccine concerns, each video starts with a provider introduction (tailored by patients’ race) intended to establish trust and build empathy. The use of empathy was careful and deliberate; if a mother expressed concerns about vaccine ingredients, the provider did not say “I understand why you are concerned about vaccine ingredients” as doing so could validate the concern. Rather, the provider said, “I understand why you want to be careful about everything that goes in your baby’s body” to establish trust and understanding by finding common ground without reinforcing false beliefs. Animation was used to address specific concerns (Figure 1) then continued to disease salience (risk perception), efficacy of solution, and a call to action with a strong, personalized recommendation from the provider to vaccinate on time. Depending on the number of vaccine concerns, each patient could receive up to 6 videos, with total length of 9–17 minutes. MomsTalkShots was designed to reinforce vaccination among those who intend to vaccinate and encourage a behavior change toward vaccine acceptance if hesitant, improve perceptions of disease susceptibility and severity, and increased confidence in vaccine safety, effectiveness and timely vaccine uptake.

Evaluation of MomsTalkShots

Study Population

To understand the effects of the app, MomsTalkShots was evaluated among pregnant women recruited from 23 geographically and socio-demographically diverse obstetrician-gynecologist offices in Georgia and Colorado in 2017. Women were eligible for participation if they were 18–50 years old, 8–26 weeks pregnant, and spoke English. Latent class analysis (an approach for audience segmentation) of our study population identified three groups of women: 1) Vaccine Enthusiasts (strong positive vaccine attitudes; most intending to get maternal and infant vaccines); 2) Vaccine Acceptors (positive vaccine attitudes without strong conviction; many intending to get maternal and infant vaccines); 3) Vaccine Skeptics (more negative vaccine attitudes; most not intending to get maternal and infant vaccines).35 Of the 2,196 pregnant women surveyed, 36% were Vaccine Enthusiasts, 41% were Vaccine Acceptors and 23% were Vaccine Skeptics.

Women were approached by trained research staff in each office; eligible women were consented and offered $20 for participation. Those who refused to participate were asked the reason for refusal. The study was approved by the Emory University IRB.

Pre-Post Intervention Survey Questions

Prior to receiving the videos, participants answered questions related to socio-demographics, maternal and infant vaccine intentions, and vaccine confidence/concerns. Demographics included race, education, and parity. Participants were asked their intention to receive maternal vaccines (no vaccines, Tdap only, influenza only, both Tdap and influenza, undecided) and infant vaccines (no vaccines, some recommended vaccines spread out, some recommended vaccines on time, all recommended vaccines spread out, all recommended vaccines on time, undecided).

Confidence in safety of maternal flu vaccine.

“I am confident that getting the flu vaccine during my pregnancy is safe for ME.” (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree). Women who disagreed or strongly disagreed were asked to choose one of the following reasons: “The flu vaccine is more likely to make me sick than protect ME from getting the flu; I do not want to put the flu vaccine in my body when I am pregnant because I think it is unnatural; I worry that the ingredients in the flu vaccine are not safe for ME to have while I am pregnant.”

Confidence in safety of maternal vaccination for the unborn infant.

“I am confident that getting the flu vaccine during my pregnancy is safe for MY UNBORN BABY.” (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree). Women who disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement were asked to choose one of the following reasons: “The flu vaccine is more likely to make me sick than protect MY UNBORN BABY from getting the flu; I do not want to put the flu vaccine into my body when I am pregnant because I think it is unnatural; I worry that the flu vaccine will cause birth defects; and I worry that the ingredients in the flu vaccine given to me during pregnancy are not safe for MY UNBORN BABY.”

Confidence in safety of maternal pertussis vaccine.

The maternal flu question that was asked specific to the pertussis vaccine.

Confidence in safety of pediatric pertussis vaccine.

The pediatric flu question that was asked specific to the pertussis vaccine.

Confidence in safety of pediatric vaccines.

“I am confident that vaccines are safe for MY BABY AFTER BIRTH.” Women who disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement were asked: “It is better for babies to get fewer vaccines as the same visit; babies get more vaccines in their first two years of life than are good for them; vaccines often cause serious side effects in babies, and the ingredients in vaccines are not safe for my baby.”

Information needs.

“I have most of the important information I need to make a decision about vaccines given during pregnancy; and I have most of the important information I need to make a decision about vaccines for MY BABY AFTER BIRTH.” Respondents were asked: “I trust the information provided by my obstetrician or midwife about vaccines during pregnancy, for babies after birth, and likewise. regarding trust about the baby’s doctor, naturopathic and/or chiropractic doctors, federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and scientists and doctors at universities and academic institutions.”

Usability.

After watching the videos, participants were asked: “The information in the app was helpful; I trust the information in the app; the app was interesting; the information in the app was clear; I have most of the important information I need to make a decision about vaccines given during pregnancy; and I have most of the important information I need to make a decision about vaccines for my baby.”

Data analysis

Four-point Likert scales were dichotomized into strongly agree and agree versus disagree and strongly disagree. Each of the four usability questions (information in app helpful, trustworthy, interesting, and clear) and change in information needs were summarized among the study population and then stratified by demographics, audience segmentation groups, maternal and infant vaccine intentions, confidence in maternal and infant vaccines, and trust in each of the sources for vaccine information. Differences in these outcome variables were modeled using logistic regression to calculate differences between groups with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Our study population of 1,103 pregnant women were demographically diverse by race (62% white, 17% Black/African American, 12% Hispanic/Latina, and 9% other) and education (13% high school diploma or equivalent, 27% some college, 35% associates or bachelor’s degree, and 25% graduate degree; Table 1). Nearly half (48%) were pregnant with their first child. Reasons for declining participation included being too busy to screen (18%), not interested in the study (40%), being wary of the study (5%), and not able to communicate or read in English (13%).

Table 1:

MomsTalkShots Usability among 1,103 Pregnant Women by Demographics

| Demographics | Total N (%) | Helpful, N (%) | Trustwort hy, N (%) | Interestin g, N (%) | Clear, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1103 | 448 (95) | 441 (94) | 450 (97) | 461 (99) |

| State | |||||

| Colorado | 545 (49) | 225 (94) | 227 (95) | 232 (97) | 237 (99) |

| Georgia | 558 (51) | 223 (97) | 214 (93) | 218 (97) | 224 (99) |

| Education* | |||||

| Graduate degree | 230 (25) | 92 (95) | 94 (97) | 91 (96) | 94 (99) |

| College degree | 312 (35) | 123 (98) | 121 (96) | 141 (95) | 149 (100) |

| Some college | 240 (27) | 97 (94) | 92 (89) | 94 (97) | 96 (99) |

| High school diploma or less | 117 (13) | 51 (94) | 49 (91) | 43 (100) | 41 (95) |

| Ethnicity† | |||||

| White | 573 (62) | 232 (94) | 233 (94) | 237 (96) | 245 (99) |

| Black/African American | 159 (17) | 64 (98) | 62 (95) | 63 (100) | 63 (100) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 116 (12) | 48 (96) | 46 (92) | 39 (91) | 41 (95) |

| Other | 83 (9) | 44 (100) | 42 (95) | 36 (100) | 36 (100) |

| First Child | |||||

| First Child | 524 (48) | 211 (97) | 207 (95) | 230 (97) | 236 (99) |

| Not first child | 576 (52) | 237 (94) | 234 (93) | 220 (97) | 225 (99) |

Graduate degree includes Master’s, Doctoral, and Professional degrees. 899 respondents, 204 participants did not report education demographics.

931 respondents, 172 participants did not report ethnicity demographics.

Percent usability are based on percent of participants who responded to the survey question, participants were randomized to receive survey questions.

The vast majority of women reported MomsTalkShots was helpful (95%), trustworthy (94%), interesting (97%) and clear (99%), which did not vary by demographics or parity (Table 2). The only difference was slightly lower reported trustworthiness among Vaccine Skeptics who reported MomsTalkShots was helpful (91%), trustworthy (85%), interesting (97%) and clear (99%). Usability factors were very high across maternal and infant vaccine intentions, though lower among those with intentions that were inconsistent with the recommended maternal and infant vaccine schedule (Table 2). Usability factors were very high among those reporting having and not having enough information to make maternal and infant vaccine decisions. Trustworthiness was lower (yet still high) among those without enough current knowledge about maternal (89%) and infant (87%) vaccines (Table 2). A very high proportion of women reported that MomsTalkShots was helpful, trustworthy, interesting and clear, and this was seen across confidence in vaccine safety, disease susceptibility, disease severity, and trust in information sources.

Table 2:

MomsTalkShots Usability by Vaccine Attitude, Vaccine Intention, Vaccine Confidence, Perceptions of Disease Susceptibility & Severity, and Trust in Information Sources

| Selected Characteristics | Helpful, N (%) | Trustworthy, N (%) | Interesting, N (%) | Clear, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Attitude Class⁺ | ||||

| Vaccine Enthusiasts | 164 (97) | 161 (95) | 171 (97) | 175 (99) |

| Vaccine Acceptors | 204 (96) | 205 (96) | 190 (96) | 195 (99) |

| Vaccine Skeptics | 80 (91) | 75 (85) | 89 (97) | 91 (99) |

| Vaccine Intention | ||||

| Maternal Vaccine Intention | ||||

| Both vaccines | 247 (98) | 249 (99) | 267 (99) | 268 (99) |

| Pertussis only | 43 (96) | 43 (96) | 40 (95) | 42 (100) |

| Flu only | 31 (100) | 30 (97) | 34 (97) | 33 (94) |

| No vaccines | 62 (85) | 55 (75) | 50 (87) | 58 (100) |

| Undecided | 65 (94) | 64 (93) | 59 (97) | 60 (98 |

| Infant Vaccine Intention | ||||

| All vaccines on time | 308 (98) | 310 (98) | 330 (98) | 334 (99) |

| All vaccines spread out | 69 (96) | 68 (84) | 48 (100) | 48 (100) |

| Some vaccines on time | 19 (95) | 17 (85) | 21 (88) | 24 (100) |

| Some vaccines spread out | 10 (77) | 7 (54) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) |

| No vaccines | 2 (22) | 3 (33) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) |

| Undecided | 40 (98) | 36 (88) | 42 (100) | 41 (98) |

| Self-Reported Vaccine Knowledge | ||||

| Has most of the important information to make a decision about maternal vaccines | 355 (96) | 353 (95) | 372 (97) | 382 (99) |

| Does not have most of the important information to make a decision about maternal vaccines | 93 (93) | 88 (89) | 77 (97) | 77 (97) |

| Has most of the important information to make a decision about infant vaccines | 365 (95) | 365 (95) | 390 (97) | 399 (99) |

| Does not have most of important information to make a decision about infant vaccines | 83 (95) | 76 (87) | 59 (98) | 60 (100) |

| Vaccine Confidence* | ||||

| Confident in safety of flu vaccine for pregnant mother | 358 (98) | 361 (98) | 362 (98) | 364 (99) |

| Not confident in safety of flu vaccine for pregnant mother | 90 (88) | 80 (78) | 87 (92) | 96 (100) |

| 1. I do not want to put the flu vaccine into my body when I am pregnant because I think it is unnatural. | 73 (85) | 64 (74) | 65 (92) | 72 (100) |

| 2. The flu vaccine is more likely to make me sick than protect me from getting the flu. | 58 (87) | 50 (75) | 50 (94) | 53 (100) |

| 3. I worry that the ingredients in the flu vaccine are not safe for me to have while I am pregnant. | 80 (86) | 70 (75) | 72 (92) | 79 (100) |

| Confident in safety of flu vaccine for unborn baby | 359 (98) | 360 (98) | 358 (98) | 361 (99) |

| Not confident in safety of flu vaccine for unborn baby | 89 (87) | 81 (79) | 91 (92) | 99 (99) |

| 4. The flu vaccine is more likely to make me sick than protect my unborn baby from getting the flu. | 49 (86) | 44 (77) | 46 (92) | 50 (100) |

| 5. I worry that the flu vaccine will cause birth defects. | 50 (85) | 47 (80) | 51 (94) | 54 (100) |

| 6. I worry that the ingredients in the flu vaccine given to me during pregnancy are not safe for my unborn baby. | 70 (85) | 63 (77) | 77 (92) | 84 (99) |

| Confident in safety of pertussis vaccine for pregnant mother | 377 (98) | 378 (98) | 379 (98) | 387 (99) |

| Not confident in safety of pertussis vaccine for pregnant mother | 71 (83) | 63 (73) | 70 (93) | 72 (96) |

| 7. I do not want to put the whooping cough vaccine into my body when I am pregnant because I think it is unnatural. | 56 (80) | 49 (70) | 59 (94) | 61 (97) |

| 8. The whooping cough vaccine is more likely to cause me to get sick than protect me from getting whooping cough. | 26 (74) | 24 (69) | 23 (88) | 26 (100) |

| 9. I worry that the ingredients in the whooping cough vaccine are not safe for me to have while I am pregnant. | 59 (81) | 52 (71) | 58 (95) | 59 (97) |

| Confident in safety of pertussis vaccine forunborn baby | 371 (98) | 373 (98) | 379 (98) | 387 (99) |

| Not confident in safety of pertussis vaccine for unborn baby | 77 (86) | 68 (76) | 70 (93) | 72 (96) |

| 10. The whooping cough vaccine is more likely to cause me to get sick than protect my unborn baby from getting whooping cough. | 30 (79) | 27 (71) | 23 (92) | 25 (100) |

| 11. I worry that the whooping cough vaccine will cause birth defects. | 47 (84) | 44 (79) | 47 (94) | 49 (98) |

| 12. I worry that the ingredients in the whooping cough vaccine given to me during pregnancy are not safe for my unborn baby. | 59 (83) | 52 (73) | 61 (94) | 64 (98) |

| Confident in safety of infant vaccines | 406 (98) | 405 (98) | 412 (98) | 416 (99) |

| Not confident in safety of infant vaccines | 42 (77) | 36 (65) | 37 (86) | 43 (100) |

| 13. It is better for babies to get fewer vaccines at the same time. | 34 (72) | 29 (62) | 29 (88) | 33 (100) |

| 14. Babies get more vaccines in their first two years of life than are good for them. | 34 (79) | 29 (67) | 24 (83) | 29 (100) |

| 15. Vaccines often cause serious side effects in babies. | 22 (71) | 16 (52) | 22 (81) | 27 (100) |

| Do not worry I could get the pertussis while pregnant | 274 (94) | 266 (91) | 24 (96) | 24 (96) |

| Worry my newborn could get pertussis | 257 (97) | 258 (98) | 21 (95) | 21 (95) |

| Do not worry my newborn could get pertussis | 159 (92) | 151 (88) | 14 (100) | 14 (100) |

| Disease Severity | ||||

| The flu is dangerous for pregnant women | 30 (97) | 30 (97) | 358 (97) | 367 (99) |

| The flu is not dangerous for pregnant women | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 57 (97) | 59 (100) |

| Pertussis is dangerous for pregnant women | 310 (96) | 311 (96) | 23 (96) | 24 (100) |

| Pertussis is not dangerous for pregnant women | 106 (94) | 98 (87) | 12 (100) | 11 (92) |

| Pertussis is dangerous for babies | 380 (96) | 375 (94) | 31 (97) | 31 (97) |

| Pertussis is not dangerous for babies | 36 (92) | 34 (87) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) |

| Trust in Information Sources | ||||

| Do not trust information from my OB/midwife | 20 (74) | 15 (56) | 27 (90) | 30 (97) |

| Trust information from my pediatrician | 384 (96) | 385 (97) | 393 (98) | 398 (99) |

| Do not trust information from my pediatrician | 18 (75) | 13 (54) | 12 (80) | 15 (100) |

| Trust information from the CDC | 371 (98) | 372 (99) | 374 (98) | 377 (99) |

| Do not trust information from the CDC | 77 (83) | 69 (74) | 75 (90) | 83 (99) |

| Trust information from scientists & doctors at universities | 368 (97) | 368 (97) | 370 (98) | 377 (99) |

| Do not trust information from scientists & doctors at universities | 80 (88) | 73 (80) | 79 (94) | 83 (99) |

Bold: p-value for the Pearson chi-squared proportion test at significance level of (α) 5% is significant

These classes were created by latent class analysis of mothers’ knowledge, confidence, beliefs and trust in information sources. Vaccine Enthusiasts (strong positive attitudes towards vaccines with most intending to get maternal and infant vaccines); Vaccine Acceptors (mostly positive vaccine attitudes but without strong conviction, many intending to get maternal and infant vaccines); Vaccine Skeptics (more common negative vaccine attitudes and most do not intend to get maternal and infant vaccines)

Participants received the numbered specific concerns question if they were not confident in the stated maternal or childhood vaccine questions.

Participants who were not confident in the safety of vaccines had a median number of 3 specific concerns, with an inter-quartile range from 2 to 4. Participants had a range of 1 to 14 specific concerns, having 1 specific concern was most frequent (24%).

The vast majority of women reported having enough information to decide about vaccines during pregnancy (95%) and for infants (95%) after watching the videos. Changes in self-assessment of knowledge pre- and post- MomsTalkShots videos is summarized in Table 3. Across all groups, the majority (72%) without enough information pre-videos reported having enough information post-videos. Across all groups, a small proportion who had enough information pre-videos did not have enough information after watching the videos: these 16 women were about equally split between those who were and were not intending to get maternal and infant vaccines, confident in vaccine safety, and trusting of various sources for vaccine information.

Table 3:

Changes in Self-Assessment of Knowledge Pre and Post MomsTalkShots Intervention videos, Stratified by First Time Motherhood, Maternal & Infant Vaccine Intentions, Vaccine Confidence and Trust in Information Sources

| I have most of the important information I need to make a decision about…. | Maternal vaccines, N (%) | Infant vaccines, N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Enough Information Pre Video | Enough Information Pre Video | Not Enough Information Pre Video | Enough Information Pre Video | |||||

| Not Enough Information Post Video | Enough Information Post Video | Not Enough Information Post Video | Enough Information Post Video | Not Enough Information Post Video | Enough Information Post Video | Not Enough Information Post Video | Enough InformationPost Video | |

| All Pregnant Women | 29 (3) | 131 (15) | 16 (2) | 687 (80) | 28 (3) | 111 (13) | 13 (2) | 711 (82) |

| First Child | ||||||||

| First Child | 20 (5) | 89 (22) | 9 (2) | 294 (71) | 22 (5) | 82 (20) | 6 (2) | 302 (73) |

| Not first child | 9 (2) | 42 (9) | 7 (2) | 393 (87) | 6 (1) | 29 (6) | 7 (2) | 409 (91) |

| Vaccine Intention | ||||||||

| Maternal Vaccine Intention | ||||||||

| Both vaccines | 3 (0.5) | 39 (8) | 8 (1.5) | 437 (90) | 2 (0.5) | 41 (8.5) | 6 (1) | 438 (90) |

| Whooping cough only | 4 (5) | 15 (19) | 0 (0) | 59 (76) | 6 (8) | 8 (10) | 0 (0) | 64 (82) |

| Flu only | 4 (5) | 9 (14) | 2 (3) | 48 (76) | 2 (3) | 13 (21) | 2 (3) | 46 (73) |

| No vaccines | 10 (9) | 24 (20) | 5 (4) | 79 (67) | 11 (9) | 20 (17) | 3 (3) | 84 (71) |

| Undecided | 8 (7) | 44 (37) | 1 (1) | 64 (55) | 7 (6) | 29 (25) | 2 (2) | 79 (68) |

| Infant Vaccine Intention | ||||||||

| All vaccines on time | 8 (1.5) | 73 (12) | 8 (1.5) | 508 (85) | 4 (0.5) | 51 (8.5) | 6 (1) | 536 (90) |

| All vaccines spread out | 5 (4) | 20 (17) | 2 (2) | 88 (77) | 7 (6) | 17 (15) | 3 (2) | 88 (77) |

| Some vaccines on time | 4 (10) | 8 (20) | 2 (5) | 26 (65) | 1 (2.5) | 11 (27.5) | 2 (5) | 26 (65) |

| Some vaccines spread out | 3 (16) | 1 (5) | 2 (11) | 13 (68) | 2 (11) | 5 (26) | 0 (0) | 12 (63) |

| No vaccines | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (93) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (93) |

| Undecided | 8 (10) | 29 (37) | 2 (3) | 39 (50) | 13 (17) | 27 (35) | 2 (2) | 36 (46) |

| Vaccine Confidence | ||||||||

| Confident in safety of flu vaccine for pregnant mother | 12 (2) | 79 (12) | 11 (2) | 576 (85) | 7 (1) | 72 (11) | 11 (1) | 588 (87) |

| Not confident in safety of flu vaccine for pregnant mother | 17 (9) | 52 (28) | 5 (3) | 111 (60) | 21 (11) | 39 (21) | 2 (1) | 123 (66) |

| Confident in safety of flu vaccine for unborn baby | 12 (2) | 77 (11) | 12 (2) | 577 (85) | 8 (1) | 77 (11) | 11 (2) | 582 (86) |

| Not confident in safety of flu vaccine for unborn baby | 17 (9) | 54 (29) | 4 (2) | 110 (59) | 20 (11) | 34 (18) | 2 (1) | 129 (70) |

| Confident in safety of whooping cough vaccine for pregnant mother | 12 (2) | 90 (12) | 13 (2) | 603 (84) | 12 (2) | 81 (11) | 9 (1) | 616 (86) |

| Not confident in safety of whooping cough vaccine for pregnant mother | 17 (12) | 41 (28) | 3 (2) | 84 (58) | 16 (11) | 30 (21) | 4 (3) | 95 (65) |

| Confident in safety of whooping cough vaccine for unborn baby | 10 (1) | 82 (11) | 14 (2) | 609 (85) | 10 (1) | 78 (11) | 9 (1) | 618 (87) |

| Not confident in safety of whooping cough vaccine for unborn baby | 19 (13) | 49 (33) | 2 (1) | 78 (53) | 18 (12) | 33 (22) | 4 (3) | 93 (63) |

| Confident in safety of infant vaccines | 15 (2) | 106 (14) | 12 (1) | 638 (83) | 13 (2) | 80 (10) | 11(2) | 667 (86) |

| Not confident in safety of infant vaccines | 14 (15) | 25 (27) | 4 (4) | 49 (53) | 15 (16) | 31 (34) | 2 (2) | 44 (48) |

| Trust in Information Sources | ||||||||

| Trust information from my OB/midwife | 16 (2) | 115 (14) | 13 (2) | 665 (82) | 16 (2) | 91 (11) | 12 (2) | 690 (85) |

| Do not trust information frommy OB/midwife | 13 (24) | 16 (30) | 3 (5) | 22 (41) | 12 (22) | 20 (37) | 1 (2) | 21 (39) |

| Trust information from my pediatrician | 16 (2) | 98 (13) | 14 (2) | 611 (83) | 17 (2) | 72 (10) | 11 (1) | 639 (87) |

| Do not trust information from my pediatrician | 6 (15) | 11 (28) | 1 (3) | 21 (54) | 6 (15) | 15 (38) | 1 (3) | 17 (44) |

| Trust information from the CDC | 13 (2) | 92 (13) | 8 (1) | 587 (84) | 12 (2) | 71 (10) | 9 (1) | 608 (87) |

| Do not trust information from the CDC | 16 (10) | 39 (24) | 8 (5) | 100 (61) | 16 (10) | 40 (25) | 4 (2) | 103 (63) |

| Trust information from scientists & doctors at universities | 16 (2) | 100 (14) | 12 (2) | 577 (82) | 14 (2) | 80 (11) | 11 (2) | 600 (85) |

| Do not trust information from scientists & doctors at universities | 13 (8) | 31 (20) | 4 (2) | 110 (70) | 14 (9) | 31 (20) | 2 (1) | 111 (70) |

Discussion

MomsTalkShots was designed to provide individually tailored vaccine information to pregnant women, a population with varied vaccine intentions, confidence, and vaccine concerns. MomsTalkShots was extremely well received among pregnant women, with the vast majority reporting it was helpful, trustworthy, interesting and clear, even among women who did not intend to vaccinate themselves or their infants according to the recommended immunization schedule. MomsTalkShots also filled an information gap; among hesitant mothers, pre- vs. post-app data indicated a two-thirds reduction in mothers reporting a need for additional vaccine information to make their vaccine decisions.

The majority of pregnant women reported already having enough information on vaccines to make decisions about maternal and infant vaccines and had already formed vaccine intentions. Few new mothers (26%) reported not have enough information about maternal or infant vaccines or being unsure of their intentions for maternal (19%) or infant vaccines (14%). MomsTalkShots, designed to move participants along the vaccine acceptance pathway, may also be useful for these parents who have already given considerable thought to vaccines.

Our study population, from only two states, may limit generalizability. Recruitment was done prior to the 2019 measles outbreak which could have effected MomsTalkShots usage. However, our study population had diverse demographics and vaccine attitudes and beliefs. Our participants was well educated; future studies could consider capturing a larger number of less-educated participants. There is the potential for selection bias as participants consented to participate in a clinical trial. Translation of MomsTalkShots into other languages is warranted. Additional studies are required to identify approaches to MomsTalkShots outside a clinical trial setting in which participants are recruited and incentivized. Scale-up from a technological perspective has very low marginal costs though gaining widespread use among the target population may require innovative approaches. This study focused on usability and filling information gaps. Vaccine education needs to also provide sustained changes in vaccine knowledge, attitudes and beliefs and increase vaccine uptake. We are evaluating MomsTalkShots in a randomized controlled trial allowing us to measure these important outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first tailored, patient-centered, scalable and low-cost vaccine intervention described in the literature.

Conclusion

MomsTalkShots was developed for maternal and infant vaccines; if shown to positively impact attitudes, beliefs and vaccine uptake, expansion to adolescent and adult vaccines should be a priority. MomsTalkShots was based on extensive population-based surveys available in the published literature regarding vaccine attitudes, beliefs and intentions. Other developed countries such as Canada, Australia and most European countries have such data available and could use our approach to developing tailored vaccine interventions for their populations. With hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries36 and widespread mobile use, the potential for a tailored vaccine intervention to impact vaccine uptake is also relevant. Many other areas of clinical medicine and public health require information tailored on factors such as disease status, information deficits and source credibility; MomsTalkShots is easily tailored to meet these needs. MomsTalkShots offers a platform to deliver audience segmented tailored communication to inform patients and increase adherence with clinical recommendations.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01AI110482]. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

D Salmon received consulting and/or research support form Merck, Walgreens and Pfizer. M Dudley received some support from Walgreens. N Halsey served on one day advisory committees for Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur; he serves on safety monitoring committees for an experimental Norovirus vaccine developed by Takeda and HPV vaccines developed by Merck; he also serves on advisory boards for a Lyme disease vaccine developed by Valneva and a live pertussis vaccine developed by ILiAD Biotechnologies. A Chamberlain received paid consultancy with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists regarding provider-to-patient communications.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosure

R Limaye, O Oloko, C Church-Balin, M Ellingson, C Spina, S Brewer, F Malik P Frew, S O’Leary, W Orenstein, S Omer have no conflicts and report no financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine Hesitancy: Causes, Consequences, and a Call to Action. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6 Suppl 4):S391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Measles in Europe: record number of both sick and immunized. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/sections/press-releases/2019/measles-in-europe-record-number-of-both-sick-and-immunized Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 3.WHO. Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event--Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August-September 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(7):169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glanz JM, McClure DL, Magid DJ, Daley MF, France EK, Hambidge SJ. Parental refusal of varicella vaccination and the associated risk of varicella infection in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glanz JM, McClure DL, O’Leary ST, Narwaney KJ, Magid DJ, Daley MF, Hambidge SJ. Parental decline of pneumococcal vaccination and risk of pneumococcal related disease in children. Vaccine. 2011;29(5):994–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Gallagher K, Rota PA, Rota J, Bellini W, Seward J. Measles in the United States during the postelimination era. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(10):1520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, Phillips L, Smith NJ, Chen RT. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws: individual and societal risk of measles. JAMA. 1999;282(1):47–53. Erratum in: JAMA. 2000 May 3;283(17):2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glanz JM, McClure DL, Magid DJ, Daley MF, France EK, Salmon DA, Hambidge SJ. Parental refusal of pertussis vaccination is associated with an increased risk of pertussis infection in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1446–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omer SB, Enger KS, Moulton LH, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Salmon DA. Geographic clustering of nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements and associations with geographic clustering of pertussis. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168(12):1389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omer SB, Pan WK, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Moulton LH, Navar AM, Pierce M, Salmon DA. Nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidence. JAMA. 2006;296(14):1757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, et al. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy A, Lavail K, Nowak G, Basket M, Landry S. Confidence about vaccines in the United States: understanding parents’ perceptions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(6):1151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, Salmon DA, Omer SB. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013. September 13;31(40):4293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daley MF, Narwaney KJ, Shoup JA, Wagner NM, Glanz JM. Addressing Parents’ Vaccine Concerns: A Randomized Trial of a Social Media Intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(1):44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanz JM, Wagner NM, Narwaney KJ, et al. Web-based Social Media Intervention to Increase Vaccine Acceptance: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014. April;133(4):e835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The Influence of Provider Communication Behaviors on Parental Vaccine Acceptance and Visit Experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1998–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, Devere V, Zhou C, Robinson JD. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrikson NB, Opel DJ, Grothaus L, et al. Physician Communication Training and Parental Vaccine Hesitancy: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):70–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dempsey AF, Pyrznawoski J, Lockhart S, et al. Effect of a Health Care Professional Communication Training Intervention on Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):e180016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards KM, Hackell JM; Committee On Infectious Diseases, The Committee On Practice And Ambulatory Medicine. Countering Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keane MT, Walter MV, Patel BI, et al. Confidence in vaccination: a parent model. Vaccine 2005;23(19):2486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, Cheater F, Bedford H, Rowles G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gust D, Brown C, Sheedy K, Hibbs B, Weaver D, Nowak G. Immunization attitudes and beliefs among parents: beyond a dichotomous perspective. Am J Health Behav 2005;29(1):81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gust DA, Darling N, Kennedy A, Schwartz B. Parents with doubts about vaccines: which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):718–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahan DM. Vaccine Risk Perceptions and Ad Hoc Risk Communication: An Empirical Assessment CCP Risk Perception Studies Report No. 17 Yale Law & Economics Research; Paper No. 491 Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2386034 Accessed March 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, Zhao Z, Dorell CG, Howes C, Hibbs B. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126 Suppl 2:135–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC. Maternal Vaccination Coverage. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pregnancy/hcp-toolkit/maternal-vaccination-coverage.html Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 31.Bednarczyk RA, Chamberlain A, Mathewson K, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Practice-, Provider-, and Patient-level interventions to improve preventive care: Development of the P3 Model. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frew PM, Randall LA, Malik F, et al. Clinician perspectives on strategies to improve patient maternal immunization acceptability in obstetrics and gynecology practice settings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;19:123–205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dudley MZ, Limaye RJ, Omer SB, et al. Characterizing maternal vaccine attitudes and beliefs. 2019. In process. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: Analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form data-2015–2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3861–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]