CONSPECTUS:

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcriptase (RT) contains two distinct functional domains: a DNA polymerase (pol) domain and a ribonuclease H (RNase H) domain, both of which are required for viral genome replication. Over the last three decades, RT has been at the forefront of HIV drug discovery efforts with numerous nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) approved by FDA. However, all these RT inhibitors target only the pol function, and inhibitors of RT-associated RNase H have yet to enter the development pipeline, which in itself manifests both the opportunity and challenges of targeting RNase H: if developed, RT RNase H inhibitors would represent a mechanistically novel class of HIV drugs that can be particularly valuable in treating HIV strains resistant to current drugs. The challenges include: 1) the difficulty in selectively targeting RT RNase H over RT pol due to their close interplay both spatially and temporally; and over HIV-1 integrase strand transfer (INST) activity because of their active site similarities; 2) to a larger extent the inability of active site inhibitors to confer significant antiviral effect, presumably due to a steep substrate barrier by which the pre-existing substrate prevents access of small molecules to the active site. As a result, previously reported RT RNase H inhibitors typically lacked target specificity and significant antiviral potency. Achieving meaningful antiviral activity via active site targeting likely entails selective and ultra-potent RNase H inhibition to allow small molecules to cut into the dominance of substrates. Based on a pharmacophore model informed by prior work, we designed and redesigned a few metal-chelating chemotypes, such as 2-hydroxyisoquinolinedione (HID), hydroxypyridonecarboxylic acid (HPCA), 3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione (HPD) and N-hydroxythienopyrimidine-2,4-dione (HTPD). Analogues of these chemotypes generally exhibited improved potency and selectivity inhibiting RT RNase H over the best previous compounds, and further validated the pharmacophore model. Extended structure-activity relationship (SAR) on the HPD inhibitor type by mainly altering the linkage generated a few subtypes showing exceptional potency (single-digit nM) and excellent selectivity over the inhibition of RT pol and INST. In parallel, a structure-based approach also allowed us to design a unique double-winged HPD subtype to potently and selectively inhibit RT RNase H and effectively compete against the RNA/DNA substrate. Significantly, all potent HPD subtypes consistently inhibited HIV-1 in cell culture, suggesting that carefully designed active site RNase H inhibitors with ultra-potency could partially overcome the barrier to antiviral phenotype. Overall, in addition to identifying our own inhibitor types, our medicinal chemistry efforts demonstrated the value of pharmacophore and structure based approaches in designing active side directed RNase H inhibitors, and could provide a viable path to validating RNase H as a novel antiviral target.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Since the approval of azidothymidine (AZT) as the first human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) drug in 1987,1 drug discovery targeting HIV-1 has successfully delivered over 30 FDA-approved single agents2 of seven mechanistically distinct classes: anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody, CCR5 antagonist, fusion inhibitor, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs). These drugs form the basis of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART),3 which has been largely successful in managing HIV-1 infections. However, HAART is not curative, and the treatment is expected to be lifelong, which magnifies the resistance issue that often plagues antiviral therapy. Combatting resistance requires novel antivirals mechanistically distinct from current drug classes. If developed, inhibitors of reverse transcriptase (RT)-associated RNase H will represent such a new drug class.

Structure and Functions

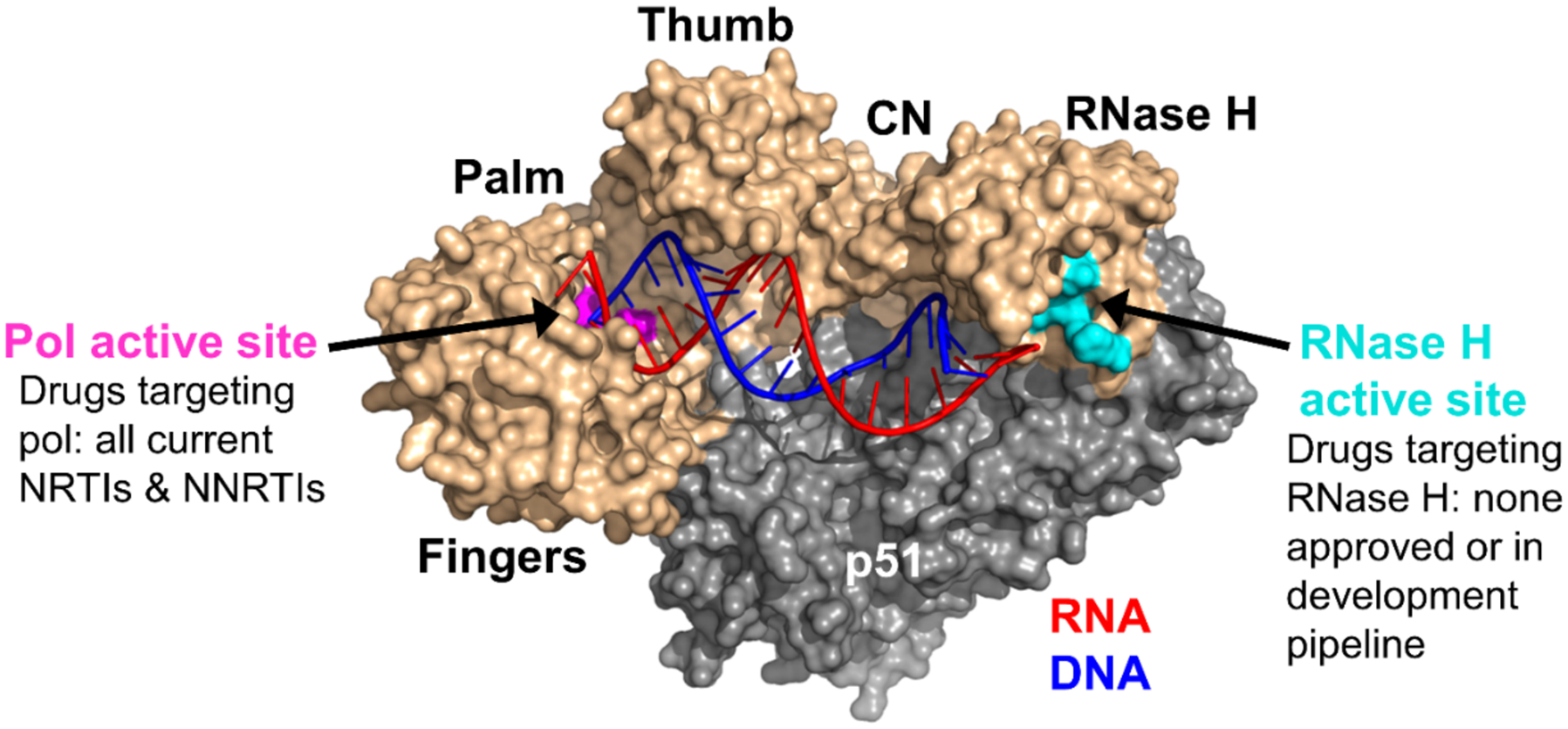

HIV-1 RT4 encodes two functionally distinct enzymatic activities, a DNA polymerase (pol) activity responsible for both RNA-dependent and DNA-dependent viral DNA polymerization; and an RNase H activity,5,6 which degrades the RNA strand from the RNA/DNA heteroduplex, the reverse transcription intermediate. In addition, RT RNase H also processes the tRNA and polypurine tract (PPT) primers for the (−) and (+) strand DNA synthesis, respectively. These two enzymatic activities of RT, housed in two separate domains, are both required for viral genome replication as mutations deleterious to either confer attenuated viral replication.6,7 Structurally, HIV-1 RT is a heterodimer consisting of two subunits: a catalytic p66, which contains a pol domain at the N-terminus and an RNase H domain at the C-terminus; and a non-catalytic p51, which lacks the RNase H domain and acts only as a structural scaffold for the p66 subunit (Figure 1).8,9 The pol domain of p66 adopts a classic right hand architecture composed of fingers, palm, thumb and the connection subdomains, whereas the RNase H domain contains a highly conserved and essential DEDD motif comprising four catalytic acidic residues (D443, E478, D498, and D549).10 Interestingly, while numerous NRTIs11 and NNRTIs12 have been approved by FDA, they all target the pol domain of RT. RT RNase H inhibitors have yet to enter the development pipeline despite many years of medicinal chemistry efforts.

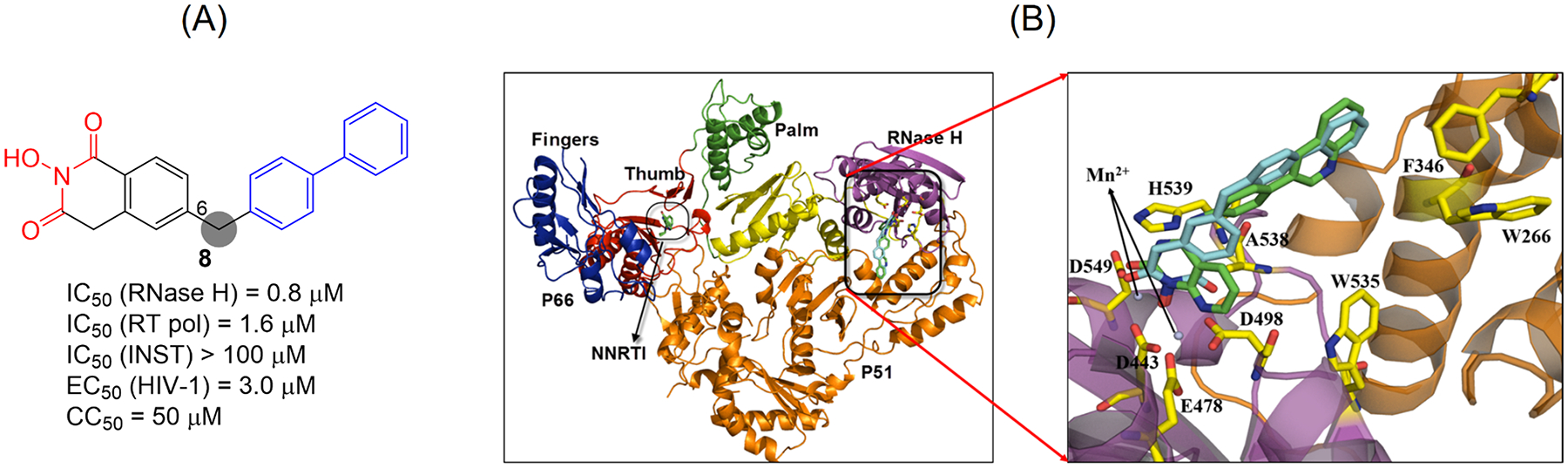

Figure 1.

Structure of RT (created with PyMOL based on PDB code 4PQU8). The active site of pol is shown in pink and that of RNase H in cyan. The RNA (red) / DNA (blue) heteroduplex engages with both active sites. CN = connection domain. Adapted from ref 14. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Challenges of RT RNase H as a Drug Target

Successfully targeting RT RNase H has been hindered by two major barriers: the difficulty in selectively inhibiting RNase H over RT pol and INST, and the general lack of translatability of RNase H inhibition to antiviral phenotype. DNA pol and the RNase H functions are carried out by RT in a highly concerted fashion temporally and spatially,5,6 during which the nucleic acid substrate (RNA/DNA hybrid) binds to both domains of p66, as well as the connection and thumb sub domains of p51 (Figure 1), and interacts with both the pol and the RNase H active sites separated by ~18 base-pairs. The interplays between the two functions of RT underlie the barrier to selective RNase H inhibition over pol. On the other hand, RT RNase H belongs to the retroviral integrase super family (RISF)13 and shares a high degree of structural and mechanistic similarities with HIV-1 integrase, including a common fold of the catalytic core, a carboxylate motif (DDE for IN and DEDD for RNase H) forming the active site, and a catalytic dependence on two Mg2+ ions. These similarities complicate efforts toward selective inhibition of RNase H over INST.

The biggest challenge in targeting RT RNase H is the difficulty in achieving antiviral activity with active site inhibitors, which is likely due to the intrinsic biochemical barrier posed by the RNA/DNA substrate.15 As mentioned earlier, RT requires a coordinated binding of the RNA/DNA substrate to both pol and RNase H domains, and the majority of the binding interactions are in the pol domain,16 resulting in a low binding dependence of the substrate on RNase H domain. In fact, the isolated RT RNase H domain is catalytically inactive presumably due to insufficient substrate binding, and the nuclease activity can be restored by N-terminal fusion of structural components capable of RNA/DNA binding, such as the basic loop of the E. coli RNase H.17 The low binding dependence on RNase H also allows HIV-1 RT to perform its nuclease activity without a well-defined and deep pocket at the RNase H active site, rendering it extremely difficult for small molecules to compete against the dominant substrate. This substrate dominance is also manifested in the inability of small molecule inhibitors to bind to the pre-formed RT-substrate complex.15 Conferring antiviral activity via active site inhibition likely requires inhibitors of extraordinary potency.

Catalytic Activities and Biochemical Assays

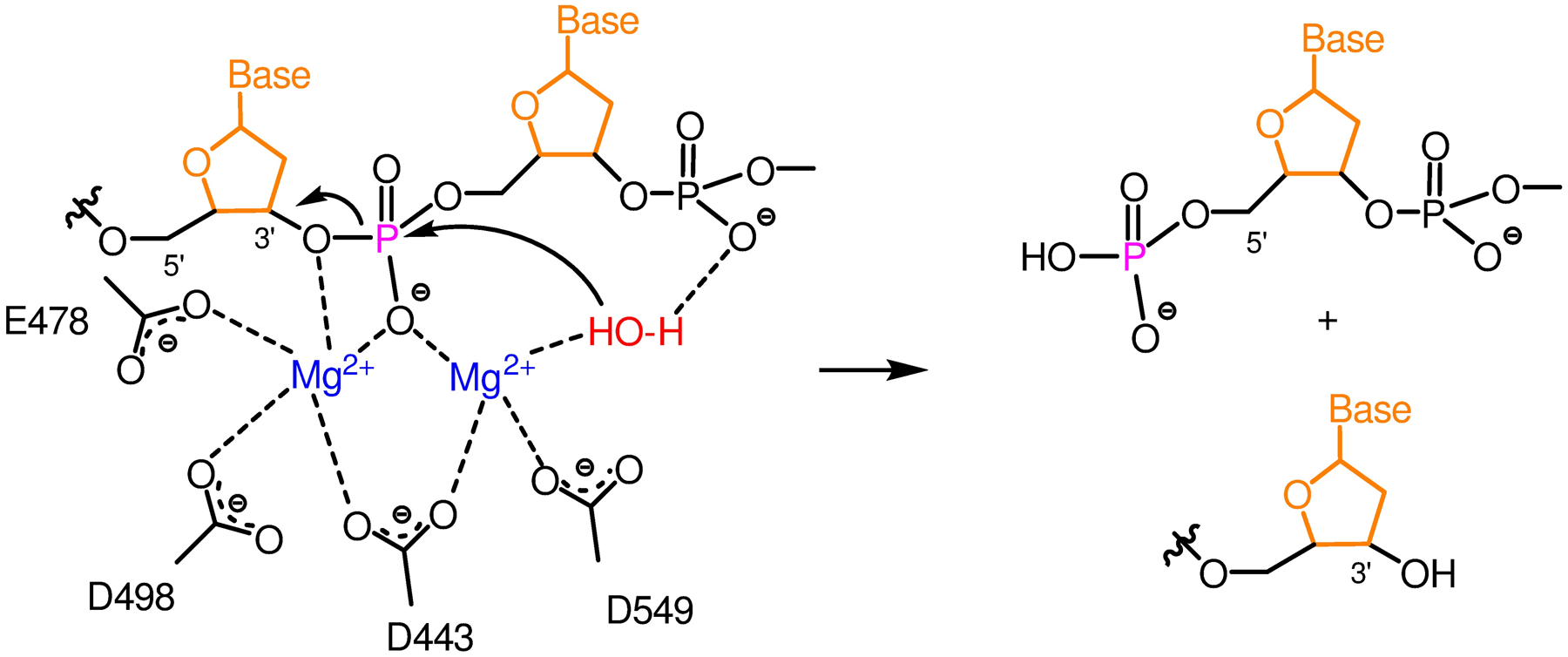

Chemically RT RNase H carries out a hydrolytic nuclease activity likely via a two Mg2+ mechanism: one Mg2+ ion coordinates, positions and activates a water nucleophile, while the other stabilizes the transition state and primes the 3'-O leaving group, leading to the formation of cleaved RNA products containing a 5'-phosphate and a 3'-OH (Figure 2).6,18

Figure 2.

Two-metal mechanism for HIV-1 RNase H activity.6

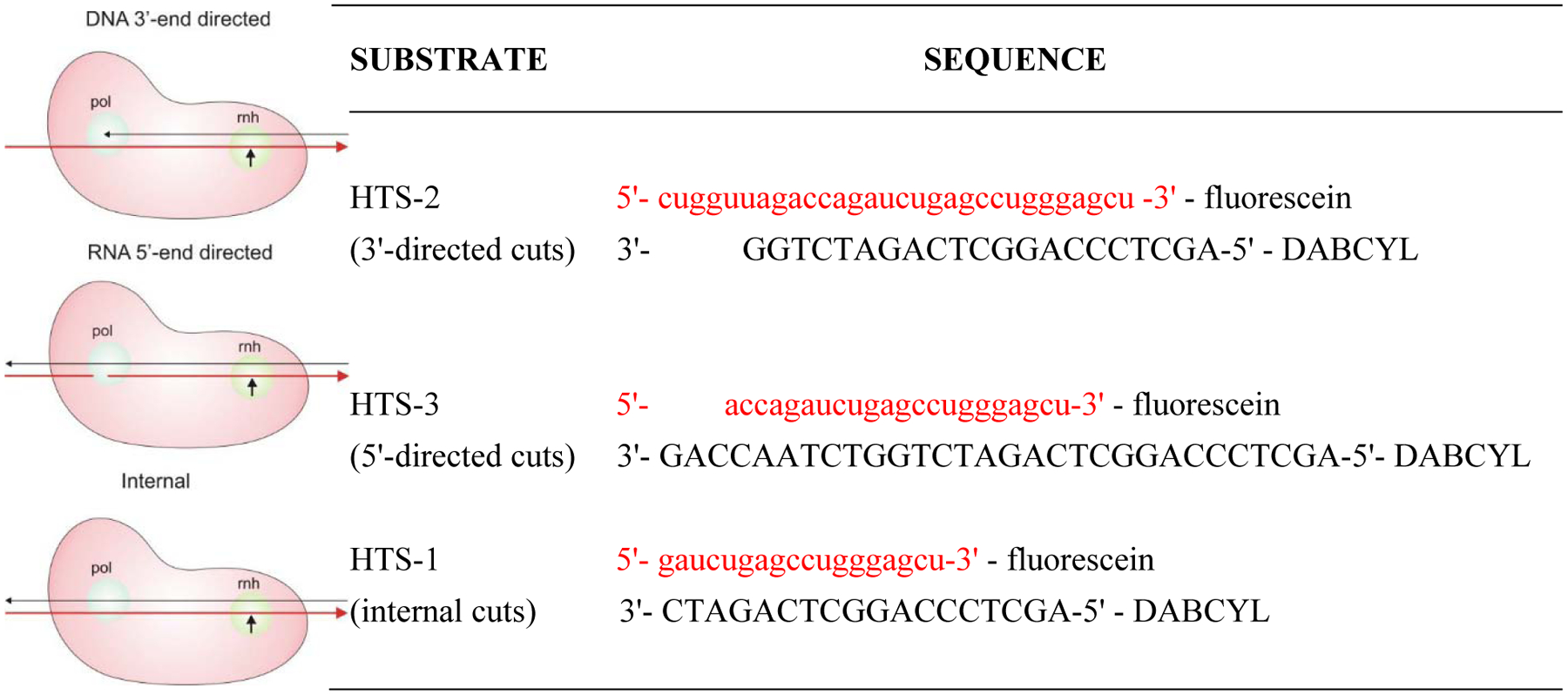

These hydrolytic reactions take place at multiple stages of reverse transcription involving at least three distinct modes of cleavage:6,18 DNA 3'-end directed cuts, RNA 5'-end directed cuts, and the random internal cuts (Figure 3, left). The DNA 3'-end directed cleavage is polymerase dependent and functions during active DNA polymerization where a recessed 3'-end of the DNA primer engages with the pol active site to position the RNA template in the RNase H active site. This mode is insufficient as RNA fragments generated are not small enough to dissociate from the primer DNA, necessitating the two pol-independent modes. In RNA 5'-end directed cleavage mode, the primer DNA strand is positioned at the pol active site by a recessed 5'-end of the template RNA to allow RNA cutting at the RNase H active site. The non-directed internal cleavage occurs within large segments of RNA/DNA duplex without positioning, and likely represents the majority of cutting events during reverse transcription. Substrates designed to measure each mode of cutting in our high-throughput (HTS) FRET assays are shown in Figure 3, right. In this account we are only presenting data from the HTS-1 substrate which measures the most frequent internal cutting events.

Figure 3.

Schematic description of modes of HIV-1 RT RNase H cleavage (left, adapted with permission from ref. 6. Copyright 2008 Elsevier) and the corresponding RNA/DNA substrates for measuring each cutting mode (right).

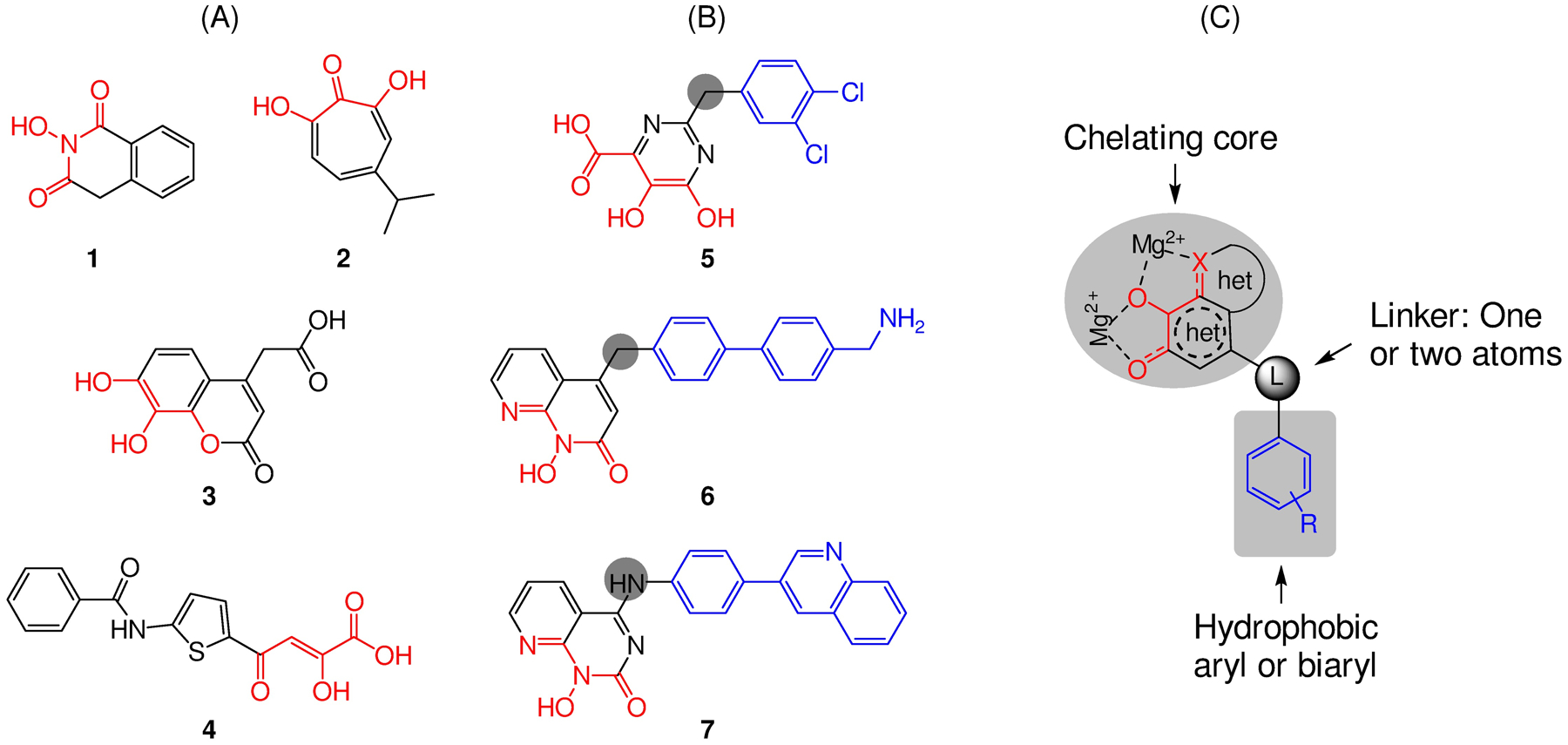

PRIOR INHIBITOR TYPES AND PHARMACOPHORE MODEL

Prior to our own work, efforts by others had identified and characterized a few active-site RNase H inhibitor types,19 including 2-hydroxyisoquinolinedione (HID, 1),20 β-thujaplicinol (2),21 dihydroxycoumarin (3),22 diketoacid (DKA, 4),23 pyrimidinol carboxylic acid (5),24 N-hydroxynaphthyridinone (6),25 and pyridopyrimidinone (7)26 (Figure 4). Among them, early inhibitor types (1-3) allowed the determination of the metal chelation requirement for active-site RNase H inhibition (Figure 4, A), though compounds of these chemical classes typically showed weak RNase H inhibition without antiviral activity. A similar inhibitory profile was observed with the original DKA chemotype 4,23 though another DKA subtype reported later showed antiviral activity with a characterized target binding mode involving chelating properties and specific interactions with the RNase H primer grip motif.27 Structurally more elaborate chemotypes (5-7, Figure 4, B) produced substantially improved RNase H inhibition. While not inhibiting HIV-1 in cells, the pyrimidinol carboxylic acid (5) chemotype inhibited RNase H in sub to low μM range, and its mode of RNase H active site binding was confirmed via co-crystal structures with RT.24,28 Of all prior HIV-1 RNase H active site inhibitor types, N-hydroxynaphthyridinone (6)25 and pyridopyrimidinone (7),26 were the most potent and best characterized, both with reported low nM RNase H inhibition and antiviral activity in the sub to low μM range. Significantly, a recent report described detailed biochemical, structural and antiviral characterization of a few N-hydroxynaphthyridinone analogues, showing that these compounds inhibited both the RNase H and pol of RT, that the best compound potently inhibited HIV-1 (EC50 = 94 nM) with a moderate therapeutic index (CC50 = 2.4 μM), and that the antiviral activity was retained against HIV-1 vectors harboring well-known INSTI, NNRTI, and NRTI resistance mutations.29 Similar dual RNase H / pol inhibition and low μM cytotoxicity were observed with the pyridopyrimidinone (7) inhibitor type. In our own assays, benchmarking compound 7 inhibited both RT RNase H (IC50 = 0.7 μM) and RT pol (IC50 = 0.85 μM) in sub μM range, and was cytotoxic (CC50 = 2.0 μM). The RNase H inhibitory potency of 7 observed in our assay was consistent with the reported binding affinity15 (Kd = 0.4 μM). Interestingly, further characterization of 7 revealed slow dissociation and tight binding kinetics, indicating that the pyridopyrimidinone inhibitor type could form long-lasting complexes with HIV-1 RT.15 Collectively, these prior studies informed the current understating on the binding mode, mechanism of inhibition and pharmacophore requirements of RNase H active site inhibitors. However, even with the best compounds of chemotypes 6 and 7, resistance selection with coding changes at RNase H active site has not been reported, and direct evidence linking the observed antiviral activity to RNase H active site inhibition still lacked. In addition, as mentioned earlier, these compounds inhibited both the pol and RNase H functions of RT in biochemical assays. Although the implication of the RT RNase H / pol dual inhibition may be open to interpretation, our goal was to achieve potent and selective RNase H inhibition.

Figure 4.

Active site inhibitor types reported prior to our work. (A) Early inhibitor types 1-3 were mostly metal chelating fragments. (B) Structurally more elaborate inhibitor types 5-7 generally conferred better potency and selectivity. (C) Prior research informed a pharmacophore model consisting of a chelating triad built around a monocyclic or bicyclic heterocycle, a hydrophobic aryl or biaryl moiety, and a one or two atoms flexible linker.

Having worked on the inhibition of both RT pol and INST, we were particularly mindful that achieving potent and selective RNase H inhibition would likely entail a design approach aligned with a good pharmacophore model. Upon close examination, the best inhibitor types (5-7) (Figure 4, B) all featured a chelating triad (red) built around a monocyclic or bicyclic heterocycle, a hydrophobic aryl or biaryl moiety (blue), and a one to three atom linker typically connected to the core right across from the central oxygen atom of the chelating triad (Figure 4, C). This pharmacophore model provided the basis of our design for novel RNase H inhibitor types.

PHARMACHOPHORE-BASED DESIGN OF HIV-1 RT RNASE H INHIBITOR TYPES

2-Hydroxyisoquinolinedione (HID).

As a stereotypical Mg2+ chelator HID (1) was among the earliest chemotypes reported to inhibit RNase H,30 and had been reported to also inhibit influenza virus PA endonuclease31 and hepatitis C virus NS5B inhibitors.32 With an oxygen-chelating triad built around a 6-membered ring, this core provides the ideal chelation to two Mg2+ ions: electronically the O atom has high affinity for Mg2+; and stereoelectronically the 6-membered ring allows the orbitals of chelating O atoms to perfectly align with those of Mg2+ ions. Based on the pharmacophore model we first redesigned the parent HID by introducing a biaryl moiety at the C-6 position via a methylene linker (Figure 5, A).33 Analogues of the redesigned series, represented by compound 8 (Figure 5, A), demonstrated low to sub μM activity inhibiting RT RNase H, exceptional selectivity over the inhibition of INST, good selectivity over E. coli RNase H and particularly MoMLV RT RNase H. However, the inhibition was not selective as most analogues also inhibited RT pol with nearly equal potency (Figure 5, A). Nevertheless, the observed inhibitory activity against HIV-1 RT was retained when tested against NNRTI-resistant mutants, suggesting that our new HID analogues do not bind to the NNRTI binding pocket. Molecular docking confirmed a binding mode consistent with active site HIV-1 RNase H inhibition (Figure 5, B). Importantly, few analogues, including 8, inhibited HIV-1 in cell culture without significant cytotoxicity.

Figure 5.

Redesigned HID subtype represented by compound 8. The design was based on the pharmacophore model. (A) Activity profile of compound 8. (B) Binding mode of 8. Left: structure of full length RT with two subunits p66 and p51. Right: a close-up view of RNase H active site with predicted binding mode of the reference compound 7 (green) and our inhibitor 8 (cyan). Adapted from ref 33. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

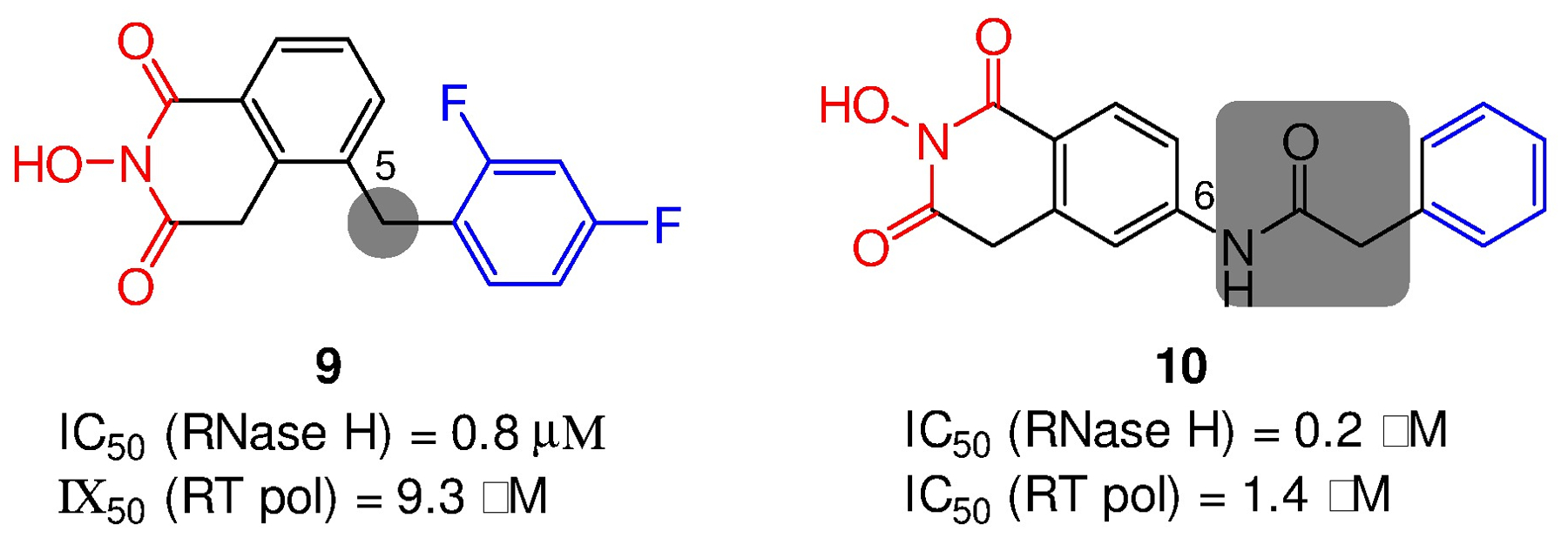

Further SAR around the HID chemotype identified a C-5 aryl subtype (9) as well as a C-6 variant (10) featuring a carboxamide linker (Figure 6).34 In biochemical assays, both subtypes inhibited HIV-1 RT-associated RNase H in nM range with good selectivity (4–11 fold) over RT pol inhibition. Although antiviral activity was not observed, the tolerance of a carboxamide as part of the linker was an important finding.

Figure 6.

Structures and activity profiles of two additional HID subtypes 9 and 10.

Hydroxypyridonecarboxylic acid (HPCA).

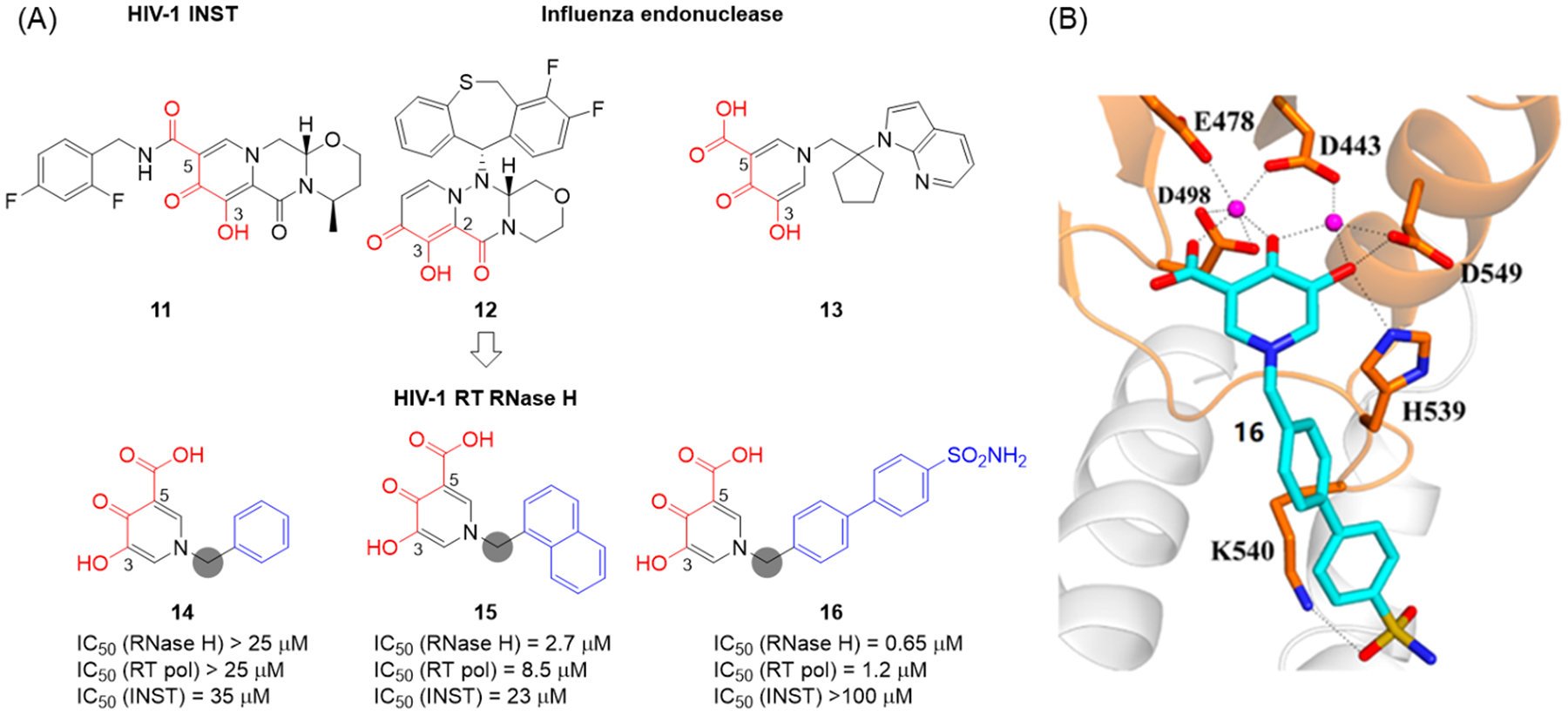

3-Hydroxy-4-pyridone-5-carboxylate and the isomeric 3-hydroxy-4-pyridone-2-carboxylate are featured in FDA approved antiviral drugs: dolutegravir (11),35 an HIV-1 INSTI bearing a 5-carboxylate; and baloxavir (12),36 an influenza virus PA endonuclease inhibitor containing a 2-carboxylate. In addition, HPCA, another closely related chelating triad with a 5-carboxylic acid as the third prong, was also the core of a large series of potent influenza virus PA endonuclease inhibitors (13).37 We designed our pharmacophore-based HPCA inhibitor types by introducing an N-1 aromatic (phenyl, naphthyl and biaryl) moiety via a methylene linker (Figure 7, A).38 In biochemical assays, analogues with a phenyl ring (14) did not inhibit RNase H, whereas the ones with a naphthyl (15), a biaryl (16) or a phenylcycloalkyl moiety demonstrated potent inhibition, suggesting that a phenyl ring itself may not provide sufficient hydrophobic binding. Such an SAR trend strongly corroborated the pharmacophore model (Figure 4, C). In addition, HPCA analogues did not significantly inhibit HIV-1 INST and inhibited RT pol moderately. To understand the molecular details of RNase H inhibition by the HPCA analogues, crystal structure of HIV RT in complex with compound 16 was solved (Figure 7, B), which shows that 16 chelates two Mg2+ through the HPCA triad and interacts directly with RT via H-bonds between the HPCA hydroxyl group and RT H539 as well as between the terminal sulfonamide group of the N-1 biaryl moiety with RT K540.

Figure 7.

(A) Pharmacophore-based design of HPCA inhibitor types 14-16. (B) X-ray crystal structure of HIV RT in complex with 16. Cross-eyed stereoview of 16 (cyan) bound at the RNase H active site of HIV RT. The RNase H domain of RT is shown in orange, the p51 in light gray. Conserved active site residues are shown as sticks, and Mg2+ ions are shown as magenta spheres. Adapted from ref 38. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione (HPD).

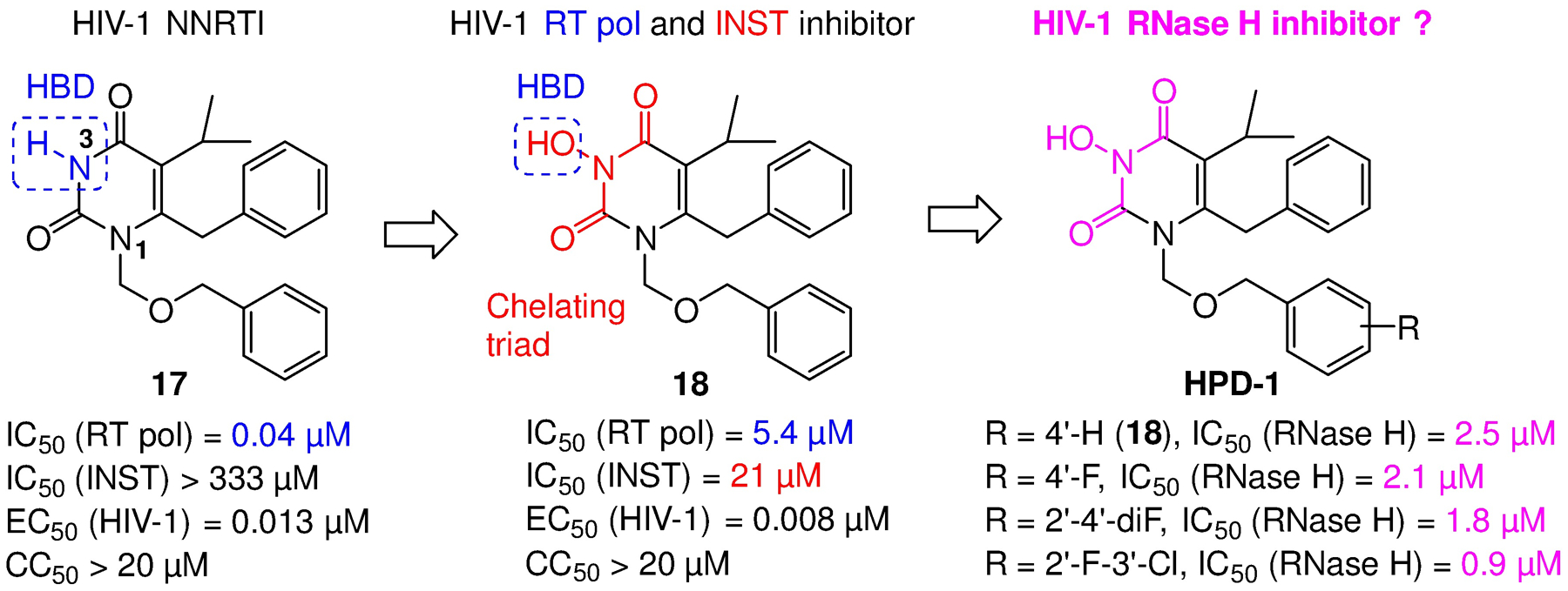

The HPD chemotype was initially designed by us to dually inhibit the RT pol and INST of HIV-1 (Figure 8),39–41 which also inhibited similar enzymes of other viruses.42–43 The design was based on a well-known NNRTI 1744 which has an N-H at the 3 position flanked by two carbonyl groups. The N-H group forms a key H-bond with K101 of RT, and thus is typically considered intolerable toward SAR. Our idea was that simply introducing an OH at the N-3 position could preserve the H-bond, though the binding to the NNRTI binding pocket could be suboptimal due to potential steric hindrance of the extra O atom. Nevertheless, this newly introduced OH will form a prototypical Mg2+ chelating triad, along with the two flanking carbonyls, to satisfy the minimal pharmacophore requirement45,46 for inhibiting INST (18, Figure 8). Essentially this was a non-invasive design with regard to inhibiting RT pol, and a highly atom economical induction of INST inhibition as either or both of the two phenyl rings could also provide the required hydrophobic binding to IN. As expected, analogues of 18 did inhibit both RT pol and INST in low μM range, and demonstrated exceptional antiviral potency in low nM range (Figure 8).39 Interestingly, when tested against RT RNase H, 18 and its analogues showed consistent inhibition in low μM range, and the inhibition requires the OH group at N-3 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The design of the original HPD chemotype and its inhibition of RT RNase H: a simple N-hydroxylation converts a potent NNRTI (17) into an RT pol/ INST dual inhibitor (18), which was later found to also inhibit RT RNase H. As was the case with INST inhibition, the OH group on N-3 was required for RNase H inhibition. HBD: hydrogen bond donor.

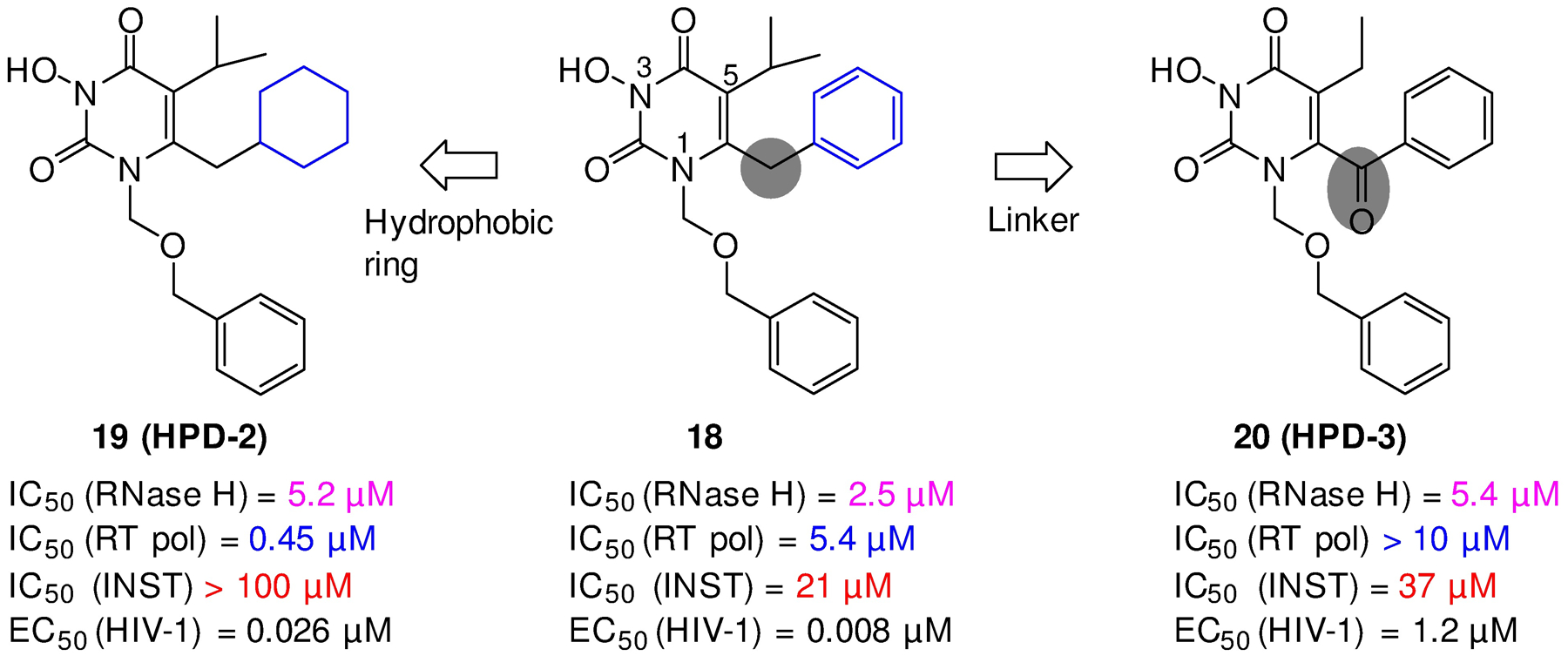

Our early SAR efforts around 18 generated two additional HPD subtypes: 19 (HPD-2)47 where the C-6 aryl was replaced with a hydrophobic cyclohexyl group; and 20 (HPD-3)48 which features a less-flexible carbonyl linker (Figure 9). Interestingly, while both subtypes inhibited RT RNase H with similar potencies, their overall biochemical inhibitory profiles and antiviral potencies were quite different. 19 inhibited RT pol in sub μM range, and did not inhibit INST at concentrations up to 100 μM, suggesting that its nM antiviral activity (EC50 = 0.026 μM) against HIV-1 mostly reflects strong RT pol inhibition. This was confirmed by an RT/19 co-crystal structure where the compound binds to the NNRTI binding pocket; and by its lack of biochemical inhibition against Y181C and K103N RT mutants. 20 did not inhibit RT pol at concentrations up to 10 μM, but weakly inhibited INST (IC50 = 37 μM). Overall, results with these early subtypes indicated that 1) cyclohexyl group as the main hydrophobic group substantially favors the inhibition of pol over RNase H and that going forward to an aryl moiety should be used at C-6 for RNase H inhibition; and 2) the carbonyl linkage at the C-6 is tolerated for RNase H inhibitor design.

Figure 9.

Two early HPD subtypes (19, 20) derived from 18, both showing low μM inhibition of RT RNase H of RT, yet different biochemical and antiviral inhibitory profiles. Structural modifications included mainly the C6 hydrophobic moiety (HPD-2) and the linker (HPD-3).

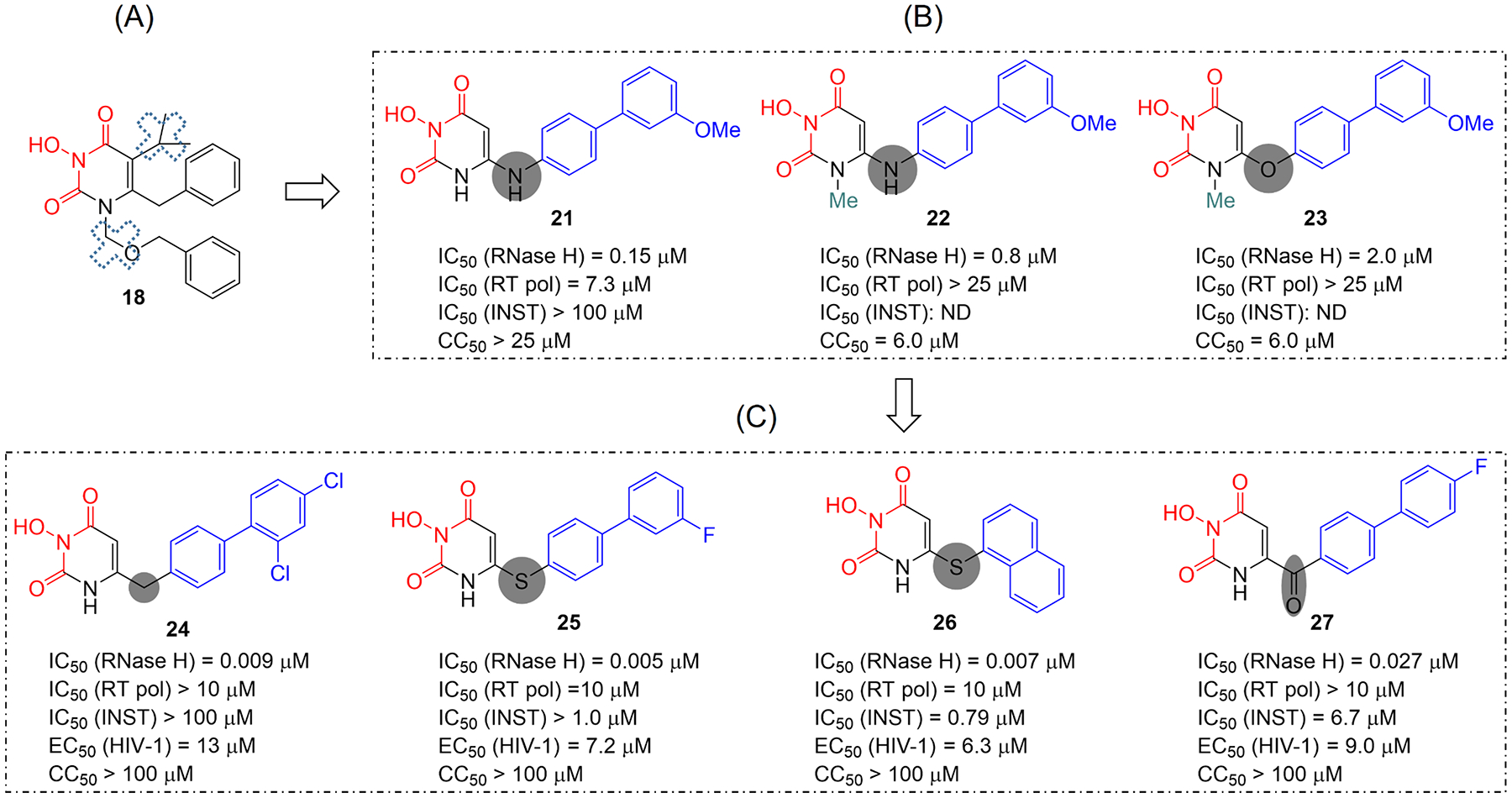

At this point our further design on HPD was geared toward achieving selective RNase H inhibition by minimizing or eliminating N-1 and / or C-5 substituents (Figure 10, A) essential for inhibiting RT pol while introducing the biaryl moiety important for RT RNaser H inhibition. As such, we designed and synthesized HPD subtypes 21–23 (Figure 10, B)49 featuring an amino (21, 22) or ether (23) linkage. SAR observations included 1) the amino linkage conferred better RNase H inhibition than the ether linkage (22 vs 23); 2) N-1 methylation caused decreased inhibitory potency (22 vs 21) and major cytotoxicity (22 and 23), suggesting that for RNase H inhibition the N-1 site should remain unsubstituted. In the end, subtype 21, which bears an amino linker at C-6 and no substituent at N-1, did inhibit RT RNase H potently (IC50 = 0.15 μM) with weak RT pol inhibition (IC50 = 7.3 μM) and no INST inhibition at concentrations up to 100 μM. This potent and selective RNase H inhibitory profile represented a drastic improvement over the original HPD 18, and superior to that of the reference compound 7. However, 21 did not inhibit HIV-1 in cell culture, which warranted further pharmacophore-based SAR.

Figure 10.

Redesigned HPD subtypes. (A) The original HPD (18) inhibited RT RNase H moderately and non-selectively. (B) Pharmacophore-based approach led to the design of more potent and selective RNase H inhibitor types 21-23 by eliminating or minimizing N-1 and C-5 substituents. (C) Further SAR identified subtypes 24-27 with optimized RNase H inhibitory profile and significant antiviral activity.

Toward this end, we designed and synthesized a few more HPD subtypes featuring different linkers at the C-6 (Figure 10, C): methylene (24),50 thioether (25, 26),51 and a nonflexible carbonyl (27).52 Remarkably, these subtypes all inhibited RT RNase H with IC50 values in single-digit (24–26) or low (27) nM range. In addition, they all showed marginal or no RT pol inhibition at concentrations up to 10 μM. In the INST assay subtypes 24 and 25 did not show significant inhibition, whereas subtypes 26 and 27 inhibited INST, though the biochemical inhibition still largely favored (>100 fold) RNase H inhibition. Consistent with the observation with the HPCA chemotype, thioether analogues with a biaryl or naphthyl moiety at C-6 position displayed far superior biochemical inhibitory profiles to those with a phenyl moiety, further confirming that a bulky aryl group is required to maximize the hydrophobic interactions. In cell-based assays, many analogues of 24-27 demonstrated significant antiviral activity in low μM range without cytotoxicity. Taken together, the linkage at C-6 position appeared to profoundly influence the inhibitory profile of the designed inhibitors: while a methylene or thioether linker provided optimal RT RNase H inhibition with single-digit nM potency and excellent selectivity, the superb inhibitory profile conferred by subtype 27 confirmed that a nonflexible linker is tolerated for RT RNase H inhibition as initially observed with 20 (HPD-3, Figure 9). The impact of functional groups on the terminal phenyl ring of the hydrophobic biaryl moiety is far less significant as compared to the linker effect, and thus not discussed herein.

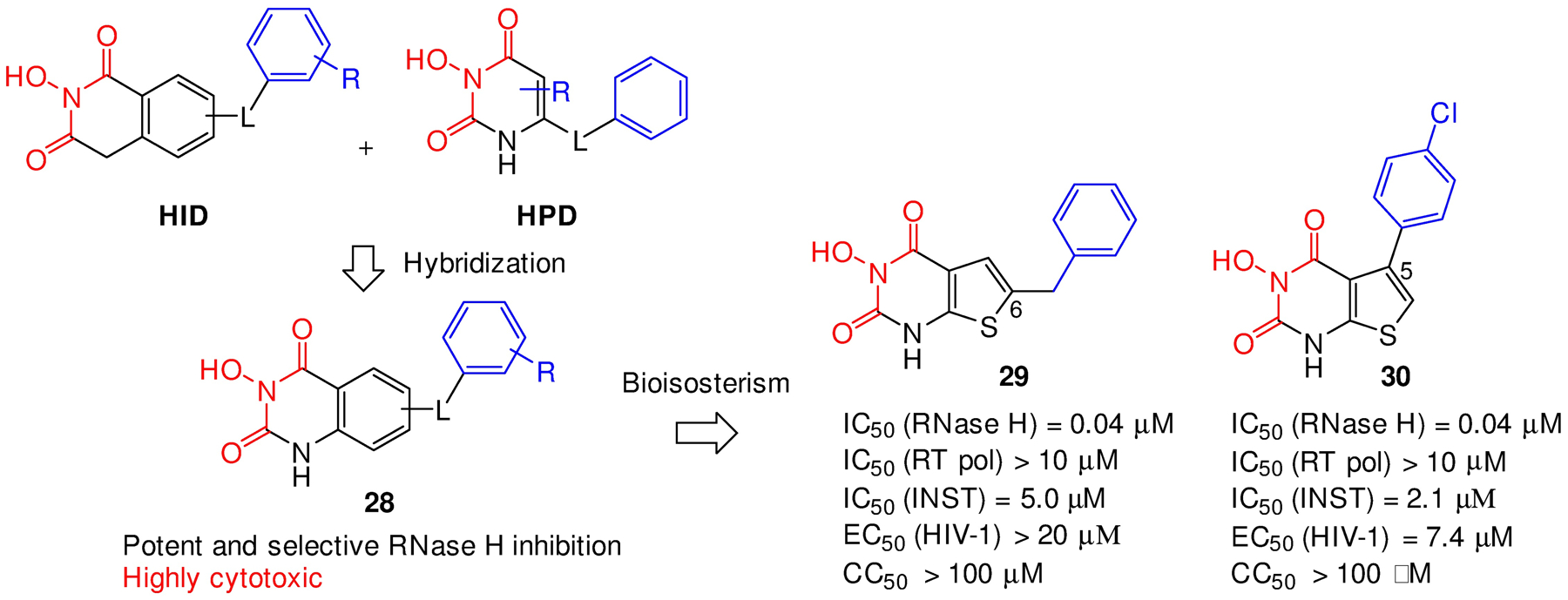

N-Hydroxythienopyrimidine-2,4-dione (HTPD).

As part of our extended efforts exploring more chelating chemotypes, we designed a novel 3-hydroxyquinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione chemotype (28) via structural hybridization between the HID and HPD inhibitor types (Figure 11). Similar hydroxyurea type of compounds have been reported to inhibit flap endonuclease 1.53 Although analogues of 28 did inhibit RNase H potently and selectively in sub μM range, they also showed significant cytotoxicity, which limits their value as a medicinal chemotype. Further efforts by replacing the fused phenyl ring with a bioisosteric thiophene ring led to the design of the HTPD core (Figure 11).54 Significantly, the bioisosterism seemed to effectively mitigate cytotoxicity as all HTPD analogues exhibited marginal or no cytotoxicity. Extensive SAR allowed us to identify analogues potently inhibiting RT RNase H in nM range with an excellent biochemical inhibitory profile including no inhibition against RT pol and very modest inhibition against INST, as exemplified by compounds 29 and 30. Some analogues with the phenyl moiety at C-5 position (30) also inhibited HIV-1 in cell-based assays (EC50 = 7.4 μM). Crystallographic studies and molecular modeling also confirmed the binding mode supporting RNase H active site inhibition.

Figure 11.

Design of the HTPD inhibitor types. Hybridization of HID and HPD designed inhibitor type 28, which upon bioisosterism inhibitor led to improved HTPD inhibitor types 29 and 30.

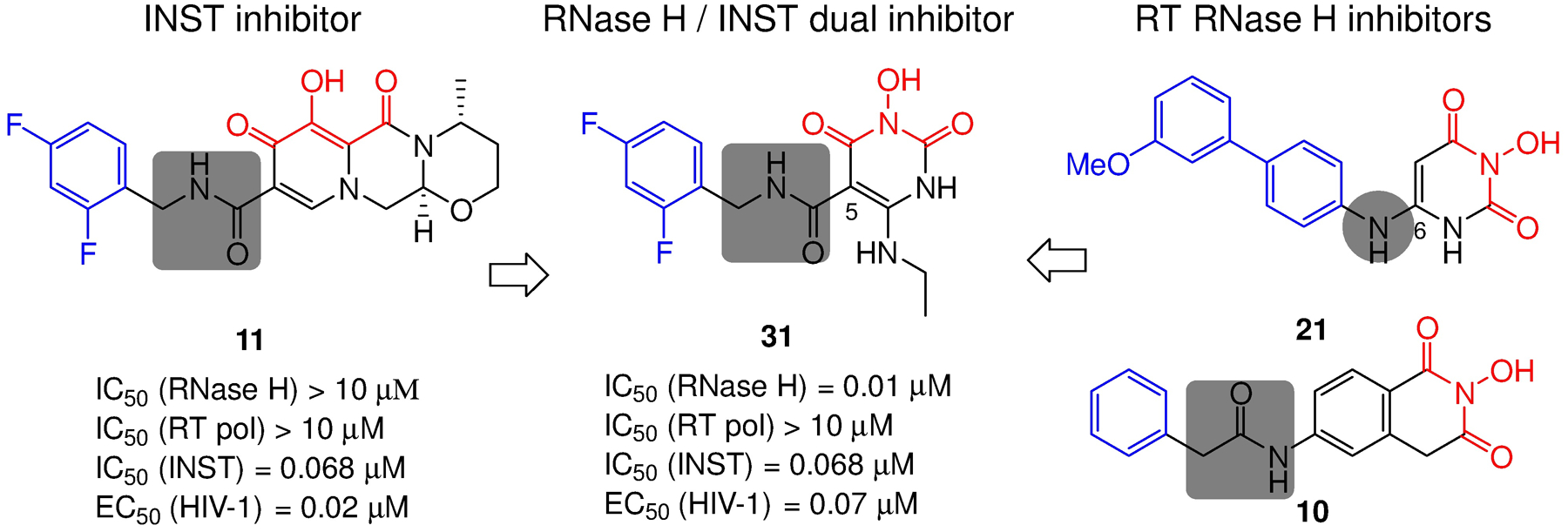

A C-5 HPD subtype for RT RNase H / INST dual inhibition.

We have previously designed an HPD subtype (compound 31, Figure 12) to inhibit HIV-1 INST.55 The design featured a HPD core, a hydrophobic aromatic ring and a carboxamide linkage at C-5 of HPD to satisfy the canonical pharmacophore45,46 of INST inhibitors, such as FDA-approved DTG (11, Figure 12). Compound 31 inhibited INST (IC50 = 68 nM) and HIV-1 (EC50 = 70 nM) with high potency. Interestingly, all these pharmacophore elements were also found in RT RNase H inhibitors (21 and 10) except that the amide linkage was reversed (31 vs 10), and the aryl moiety were translocated from C-6 to C-5 (31 vs 21). Remarkably, 31 and its analogues also inhibited RNase H with exceptional potency (IC50 = 10 nM for 31, Figure 12),55 suggesting that repositioning the aryl and the linkage from C-6 to C-5 of HPD is tolerated, and that the observed potent antiviral activity could be due to dual target inhibition. Such dual inhibitors hold the promise of single-molecule-multi-target therapy, while also highlighting the challenge of designing RNase H specific inhibitors over INST.

Figure 12.

HPD subtype represented by compound 31 fits the pharmacophore of both INST and RT RNase H inhibitors, and inhibited both enzymatic functions with high potency.

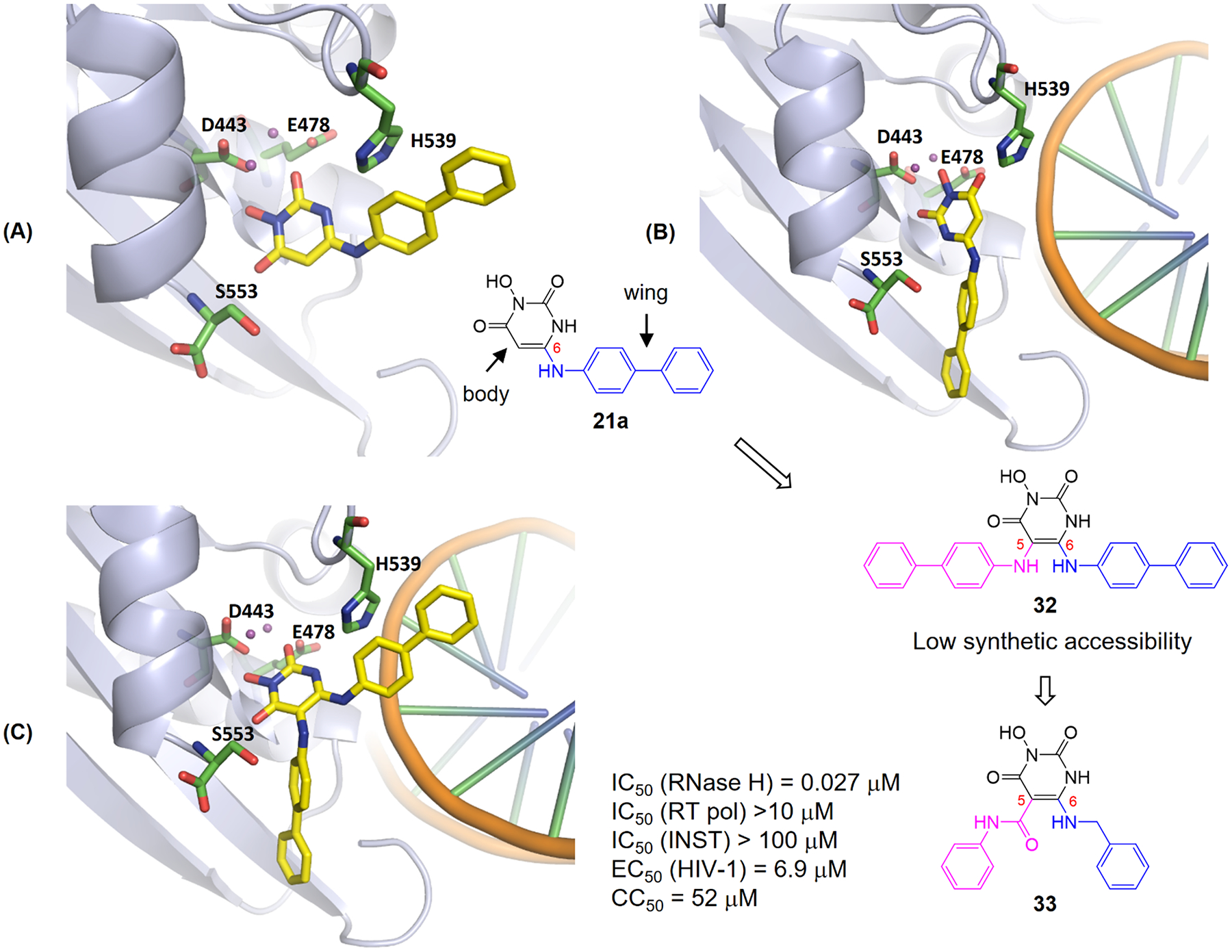

STRUCTURE-BASED DESIGN OF DOUBLE-WINGED RT RNASE H INHIBITORS

Targeting the RT RNase H active site is hindered by the dominant RNA/DNA substrate. We have shown that achieving consistent and significant antiviral activity is possible with highly potent inhibitors designed using a pharmacophore-based approach. Structure-based design represents another distinct approach that could yield potent inhibitors to cut into the substrate dominance. We describe herein our attempt14 to redesign the HPD subtype 21 which inhibited RT RNase H in sub range but did not exhibit antiviral activity. Interestingly, when docked into the active site of RNase H, compound 21a adopts two distinct binding modes in the absence or presence of the nucleic acid substrate (Figure 13). Without the substrate, 21a prefers a pose where the chelating core (the body) latches on the two divalent metal ions in an orientation to allow the C-6 biarylamino moiety (the wing) to reach and interact with H539 (Figure 13, A). However, this key interaction is lost in the presence of the nucleic acid substrate which forces the wing of 21a to point away from H539 (Figure 13, B). To allow the inhibitor to better compete against the more dominant substrate, we envisioned a double-winged subtype (32) capable of interacting with H539 with or without the substrate (Figure 13, C). Further design of the C-5 wing involved replacing the amino linkage with a synthetically more accessible carboxamide linkage55 which is tolerated in the design of RNase H inhibitors as shown earlier. As expected, the addition of a C-5 wing drastically improved RNase H inhibition as compound 33 inhibited RNase H with excellent potency (IC50 = 27 nM) and selectivity, and conferred significant antiviral activity (EC50 = 6.9 μM).14

Figure 13.

Design of double-winged HPD subtype 33. Docking of single-winged subtype 21a into RNase H active site without (A) or with (B) substrate. With the substrate binding to the active site, the wing of 21a is forced to flip and the key interaction with H539 is lost. Introducing a second wing (pink) at the C-5 position of HPD led to the design of 32 which allows interactions with H539 and nucleic acid substrate (C, docking of 32). Unsymmetrically double-winged subtype 33 is designed for synthetic accessibility. Adapted from ref 14. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVE

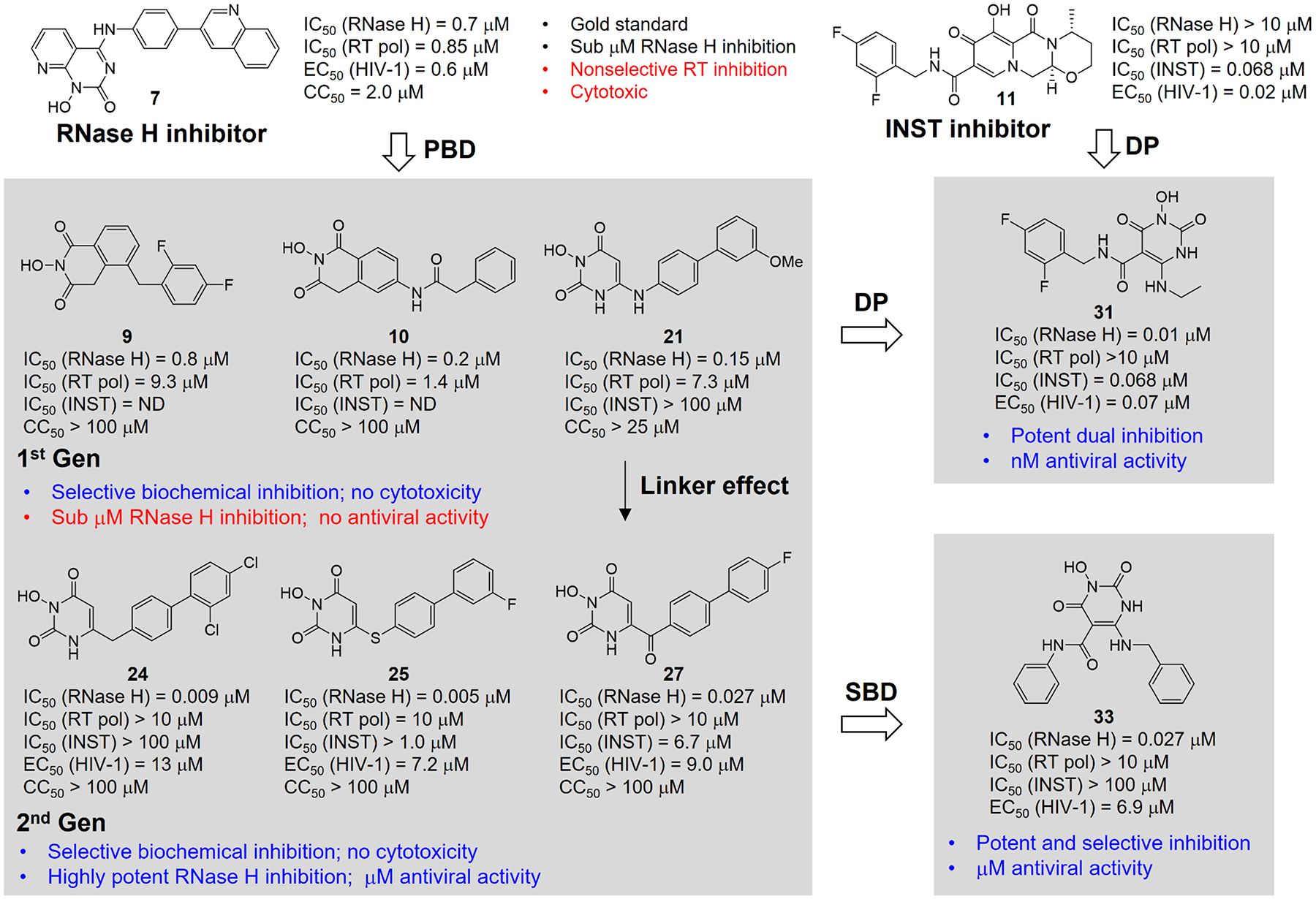

While RT inhibitors targeting pol are among the most successful drugs for treating HIV-1 infection, RT-associated RNase H remains difficult to target. Prior to our work, medicinal chemistry efforts had produced many biochemical inhibitors of RT RNase H. However, many of these inhibitors did not inhibit HIV-1. In cases where antiviral activity was observed, inhibitors still lacked selective RNase H inhibition over RT pol inhibition, and exhibited significant cytotoxicity (benchmarking compound 7, Figure 14). Considering that the antiviral barrier is mostly due to RNA/DNA substrates overwhelming small molecules for active site binding, we hypothesized that selective RNase H inhibitors with the potency substantially better than previous best compounds could compete better to cut into the substrate dominance, and thus conferring the coveted antiviral effect.

Figure 14.

Evolution of our designed inhibitor types. The best previous compound (7) was used for benchmarking. Pharmacophore-based design (PBD) led to the 1st Gen inhibitor types (9, 10, and 21) with improved selectivity profile; further design by altering the linker identified 2nd Gen HPD subtypes (24, 25, and 27) exhibiting optimal RNase H inhibition and significant antiviral activity. A parallel structure-based design (SBD) generated a double-winged subtype 33 with excellent overall activity profile. A dual pharmacophore (DP) approach allowed the design of 31 which fits the pharmacophores of both RT RNase H and INST.

Achieving a biochemical inhibitory profile with exceptional potency and excellent selectivity lends itself to a pharmacophore-based approach. Therefore, while aiming at exploring novel inhibitor types for more potent and selective RT RNase H inhibition, we formulated a pharmacophore model informed by best previous inhibitor types (5-7), and used it in our design. Although our 1st generation inhibitors (9, 10 and 21) did not confer antiviral activity, likely because the RNase H inhibition was not significantly improved compared to reference compound 7, they did show selective inhibition over RT pol and no significant cytotoxicity (Figure 14). The subsequent design, particularly via altering the linker, identified our 2nd generation HPD inhibitor types (24, 25 and 27) with exceptional potency, excellent selectivity, and no cytotoxicity (Figure 14). More importantly, these subtypes inhibited HIV-1 in cell culture consistently in low μM range, which supports our hypothesis that ultra-potent active site inhibitors could confer antiviral activity. The pharmacophore-based approach also allowed us to design a potential RNase H / INST due inhibitor type 31. In parallel, a structure-based approach led to the design of a distinct “double-winged” HPD subtype 33 showing superior inhibitory profile to subtype 21. Overall, our pharmacophore-based and structure-based approaches have identified numerous RNase H inhibitor types substantially more potent and selective, and much less toxic than the benchmarking compound 7. These approaches, along with the new inhibitor types, could provide a path forward in designing RT RNase H active site inhibitors.

On the other hand, our efforts also demonstrated that directly competing against the RNA/DNA substrates at active site to confer potent antiviral activity remains difficult. Structural studies8,56,57 have confirmed the easy access of the RNA/DNA substrate into RNase H domain active site and the facile displacement of active site inhibitors by the substrate. In this sense, targeting non-competitive allosteric binding sites within or around the RNase H active site to impact the precise positioning of the RNA/DNA hybrid could be more effective. However, the cryptic nature of allosteric binding sites renders medicinal chemistry intractable and hit generation will almost certainly rely on random screening. In addition, reported allosteric inhibitors,58 including acyl hydrazones, anthraquinones, naphthalene sulfonic derivatives, vinylogous ureas, thienopyrimidinones, and recently benzothienooxazinone,59 mostly fit the profile of pan-assay interference structures (PAINS),60 and may not be amenable to specific inhibition. Furthermore, some of these allosteric inhibitors actually bound to the pol domain near the NNRTI binding pocket,61 and thus may not offer advantages in resistance profile over NNRTIs. Some did not confer antiviral activity.59 Nevertheless, given the critical roles of RNase H in HIV-1 genome replication, and the approval of multiple metal-chelating pharmacophores as important antiviral drugs (Figure 7), targeting the active site of RT RNase H should remain a coveted and viable scientific endeavor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The research described herein was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI100890 to SGS and ZW) and partially by the Center for Drug Design, University of Minnesota. This account is in memory of Dr. Michael A. Parniak who was a major contributor to the early studies.

Biographies

Lei Wang received his Ph.D. from Hokkaido University in 2016. Since then, he joined Prof. Zhengqiang Wang’s group in University or Minnesota as a postdoctoral associate. In 2019, he started his research work at Dalian University of Technology, China. His interests are in the areas of medicinal chemistry and organic chemistry.

Stefan G. Sarafianos is the Nahmias Schinazi Distinguished Research Chair Professor and at the LOBP, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine. He received his PhD in 1993 from Georgetown University (Chemistry/Biochemistry). He was trained as a structural biologist in the Arnold laboratory (Rutgers University) solving structures of HIV-1 RT complexes. His research focuses on HIV-1, HBV structural biology, biochemistry, and virology.

Zhengqiang Wang is Professor and Program Director of Chemistry at the Center for Drug Design, University of Minnesota. He received Ph.D. in 2003 from Wayne State University in synthetic organic chemistry, and learned medicinal chemistry at University of Minnesota as a postdoctoral associate. His independent research since 2008 has focused on antiviral medicinal chemistry targeting HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and human cytomegalovirus.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).Hirsch MS AIDS Commentary. Azidothymidine. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1988, 157, 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Antiretroviral drugs used in the treatment of HIV infection, April 12, 2018. www.fda.gov.

- (3).Yeni P Update on HAART in HIV. J. Hepatol 2006, 44, S100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sarafianos SG; Marchand B; Das K; Himmel DM; Parniak MA; Hughes SH; Arnold E Structure and Function of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase: Molecular Mechanisms of Polymerization and Inhibition. J. Mol. Biol 2009, 385, 693–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Beilhartz GL; Gotte M HIV-1 Ribonuclease H: Structure, Catalytic Mechanism and Inhibitors. Viruses 2010, 2, 900–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Schultz SJ; Champoux JJ RNase H Activity: Structure, Specificity, and Function in Reverse Transcription. Virus. Res 2008, 134, 86–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Schatz O; Cromme FV; Grüninger-Leitch F; Le Grice SFJ Point Mutations in Conserved Amino Acid Residues within the C-Terminal Domain of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Specifically Repress RNase H Function. FEBS Lett. 1989, 257, 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Das K; Martinez SE; Bandwar RP; Arnold E Structures of HIV-1 RT-RNA/DNA Ternary Complexes with dATP and Nevirapine Reveal Conformational Flexibility of RNA/DNA: Insights into Requirements for RNase H Cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8125–8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nowotny M; Gaidamakov SA; Crouch RJ; Yang W Crystal Structures of RNase H Bound to an RNA/DNA Hybrid: Substrate Specificity and Metal-Dependent Catalysis. Cell 2005, 121, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Davies J; Hostomska Z; Hostomsky Z; Jordan; Matthews D Crystal Structure of the Ribonuclease H Domain of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Science 1991, 252, 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cihlar T; Ray AS Nucleoside and Nucleotide HIV Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors: 25 Years after Zidovudine. Antiviral Res. 2010, 85, 39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).de Bethune MP Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs), Their Discovery, Development, and Use in the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection: a Review of the Last 20 Years (1989–2009). Antiviral Res. 2010, 85, 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nowotny M Retroviral Integrase Superfamily: the Structural Perspective. EMBO Rep. 2009, 10, 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Vernekar SKV; Tang J; Wu BL; Huber AD; Casey MC; Myshakina N; Wilson DJ; Kankanala J; Kirby KA; Parniak MA; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ Double-Winged 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones: Potent and Selective Inhibition against HIV-1 RNase H with Significant Antiviral Activity. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 5045–5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Beilhartz GL; Ngure M; Johns BA; DeAnda F; Gerondelis P; Gotte M Inhibition of the Ribonuclease H Activity of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase by GSK5750 Correlates with Slow Enzyme-Inhibitor Dissociation. J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 16270–16277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sarafianos SG; Das K; Tantillo C; Clark AD Jr; Ding J; Whitcomb JM; Boyer PL; Hughes SH; Arnold E Crystal Structure of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase in Complex with a Polypurine Tract RNA:DNA. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1449–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Keck JL; Marqusee S Substitution of a Highly Basic Helix/Loop Sequence into the RNase H Domain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reverse Transcriptase Restores its Mn2+-Dependent RNase H Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2740–2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ilina T; Labarge K; Sarafianos SG; Ishima R; Parniak MA Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase-Associated Ribonuclease H Activity. Biology 2012, 1, 521–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wang XS; Gao P; Menendez-Arias L; Liu XY; Zhan P Update on Recent Developments in Small Molecular HIV-1 RNase H Inhibitors (2013–2016): Opportunities and Challenges. Curr. Med. Chem 2018, 25, 1682–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Billamboz M; Bailly F; Lion C; Touati N; Vezin H; Calmels C; Andreola ML; Christ F; Debyser Z; Cotelle P Magnesium Chelating 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones, as Inhibitors of HIV-1 Integrase and/or the HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Ribonuclease H Domain: Discovery of a Novel Selective Inhibitor of the Ribonuclease H Function. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 1812–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Himmel DM; Maegley KA; Pauly TA; Bauman JD; Das K; Dharia C; Clark AD Jr.; Ryan K; Hickey MJ; Love RA; Hughes SH; Bergqvist S; Arnold E Structure of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase with the Inhibitor β-Thujaplicinol Bound at the RNase H Active Site. Structure 2009, 17, 1625–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Himmel DM; Myshakina NS; Ilina T; Van Ry A; Ho WC; Parniak MA; Arnold E Structure of a Dihydroxycoumarin Active-Site Inhibitor in Complex with the RNase H Domain of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase and Structure-Activity Analysis of Inhibitor Analogs. J. Mol. Biol 2014, 426, 2617–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shaw-Reid CA; Munshi V; Graham P; Wolfe A; Witmer M; Danzeisen R; Olsen DB; Carroll SS; Embrey M; Wai JS; Miller MD; Cole JL; Hazuda DJ Inhibition of HIV-1 Ribonuclease H by a Novel Diketo Acid, 4-[5-(Benzoylamino)thien-2-yl]-2,4-dioxobutanoic Acid. J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 2777–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lansdon EB; Liu Q; Leavitt SA; Balakrishnan M; Perry JK; Lancaster-Moyer C; Kutty N; Liu X; Squires NH; Watkins WJ; Kirschberg TA Structural and Binding Analysis of Pyrimidinol Carboxylic Acid and N-Hydroxy Quinazolinedione HIV-1 RNase H Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 2905–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Williams PD; Staas DD; Venkatraman S; Loughran HM; Ruzek RD; Booth TM; Lyle TA; Wai JS; Vacca JP; Feuston BP; Ecto LT; Flynn JA; DiStefano DJ; Hazuda DJ; Bahnck CM; Himmelberger AL; Dornadula G; Hrin RC; Stillmock KA; Witmer MV; Miller MD; Grobler JA Potent and Selective HIV-1 Ribonuclease H Inhibitors Based on a 1-Hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one Scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2010, 20, 6754–6757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Velthuisen EJ; Johns BA; Gerondelis P; Chen Y; Li M; Mou K; Zhang W; Seal JW; Hightower KE; Miranda SR; Brown K; Leesnitzer L Pyridopyrimidinone Inhibitors of HIV-1 RNase H. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2014, 83, 609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Corona A; Leva FSD; Thierry S; Pescatori L; Crucitti GC; Subra F; Delelis O; Esposito F; Rigogliuso G; Costi R; Cosconati S; Novellino E; Santo RD; Tramontano E Identification of Highly Conserved Residues Involved in Inhibition of HIV-1 RNase H Function by Diketo Acid Derivatives. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014, 58, 6101–6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kirschberg TA; Balakrishnan M; Squires NH; Barnes T; Brendza KM; Chen X; Eisenberg EJ; Jin W; Kutty N; Leavitt S; Liclican A; Liu Q; Liu X; Mak J; Perry JK; Wang M; Watkins WJ; Lansdon EB RNase H Active Site Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reverse Transcriptase: Design, Biochemical Activity, and Structural Information. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 5781–5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Boyer PL; Smith SJ; Zhao XZ; Das K; Gruber K; Arnold E; Burke TR Jr., Hughes SH Developing and Evaluating Inhibitors against the RNase H Active Site of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. J. Virol 2018, 92, e02203–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Klumpp K; Hang JQ; Rajendran S; Yang Y; Derosier A; Wong Kai In P; Overton H; Parkes KEB; Cammack N; Martin JA Two-Metal Ion Mechanism of RNA Cleavage by HIV RNase H and Mechanism-Based Design of Selective HIV RNase H Inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 6852–6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Parkes KEB; Ermert P; Fässler J; Ives J; Martin JA; Merrett JH; Obrecht D; Williams G; Klumpp K Use of a Pharmacophore Model To Discover a New Class of Influenza Endonuclease Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2003, 46, 1153–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Chen YL; Tang J; Kesler MJ; Sham YY; Vince R; Geraghty RJ; Wang Z The Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluations of C-6 or C-7 Substituted 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-diones as Inhibitors of Hepatitis C Virus. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2012, 20, 467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Vernekar SK; Liu Z; Nagy E; Miller L; Kirby KA; Wilson DJ; Kankanala J; Sarafianos SG; Parniak MA; Wang Z Design, Synthesis, Biochemical, and Antiviral Evaluations of C6 Benzyl and C6 Biarylmethyl Substituted 2-Hydroxylisoquinoline-1,3-diones: Dual Inhibition against HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H and Polymerase with Antiviral Activities. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 651–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Tang J; Vernekar SKV; Chen YL; Miller L; Huber AD; Myshakina N; Sarafianos SG; Parniak MA; Wang ZQ Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modeling of 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-dione Analogues as Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase Associated Ribonuclease H and Polymerase. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2017, 133, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Johns BA; Kawasuji T; Weatherhead JG; Taishi T; Temelkoff DP; Yoshida H; Akiyama T; Taoda Y; Murai H; Kiyama R; Fuji M; Tanimoto N; Jeffrey J; Foster SA; Yoshinaga T; Seki T; Kobayashi M; Sato A; Johnson MN; Garvey EP; Fujiwara T Carbamoyl Pyridone HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors 3. A Diastereomeric Approach to Chiral Nonracemic Tricyclic Ring Systems and the Discovery of Dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572) and (S/GSK1265744). J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 5901–5916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hayden FG; Sugaya N; Hirotsu N; Lee N; de Jong MD; Hurt AC; Ishida T; Sekino H; Yamada K; Portsmouth S; Kawaguchi K; Shishido T; Arai M; Tsuchiya K; Uehara T; Watanabe A Baloxavir Marboxil for Uncomplicated Influenza in Adults and Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med 2018, 379, 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fujishita T; Mikamiyama M; Kawai M; Akiyama T Substituted 3-Hydroxy-4-Pyridone Derivative. U.S. Patent. 8,835,461 B2, September, 16, 2014.

- (38).Kankanala J; Kirby KA; Liu F; Miller L; Nagy E; Wilson DJ; Parniak MA; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluations of Hydroxypyridonecarboxylic Acids as Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase Associated RNase H. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 5051–5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tang J; Maddali K; Dreis CD; Sham YY; Vince R; Pommier Y; Wang Z N-3 Hydroxylation of Pyrimidine-2,4-diones Yields Dual Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase and Integrase. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 2, 63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tang J; Maddali K; Metifiot M; Sham YY; Vince R; Pommier Y; Wang Z 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones as an Inhibitor Scaffold of HIV Integrase. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 2282–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Tang J; Maddali K; Dreis CD; Sham YY; Vince R; Pommier Y; Wang Z 6-Benzoyl-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones as Dual Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase and Integrase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 21, 2400–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Huber AD; Michailidis E; Tang J; Puray-Chavez M; Boftsi M; Wolf J; Boschert K; Sheridan M; Leslie M; Kirby KA; Singh K; Mitsuya H; Parniak MA; Wang Z; Sarafianos SG 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones as Novel Hepatitis B Virus Antivirals Targeting the Viral Ribonuclease H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e00245–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wang Y; Tang J; Wang Z; Geraghty RJ Metal-Chelating 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones Inhibit Human Cytomegalovirus pUL89 Endonuclease Activity and Virus Replication. Antiviral Res. 2018, 152, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Hopkins AL; Ren J; Esnouf RM; Willcox BE; Jones EY; Ross C; Miyasaka T; Walker RT; Tanaka H; Stammers DK; Stuart DI Complexes of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase with Inhibitors of the HEPT Series Reveal Conformational Changes Relevant to the Design of Potent Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 1996, 39, 1589–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dayam R; Sanchez T; Clement O; Shoemaker R; Sei S; Neamati N β-Diketo Acid Pharmacophore Hypothesis. 1. Discovery of a Novel Class of HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2005, 48, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Zhao XZ; Smith SJ; Maskell DP; Métifiot M; Pye VE; Fesen K; Marchand C; Pommier Y; Cherepanov P; Hughes SH; Burke TR Structure-Guided Optimization of HIV Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 7315–7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Tang J; Kirby KA; Huber AD; Casey MC; Ji J; Wilson DJ; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ 6-Cyclohexylmethyl-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione as an Inhibitor Scaffold of HIV Reverase Transcriptase: Impacts of the 3-OH on Inhibiting RNase H and Polymerase. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2017, 128, 168–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Tang J; Maddali K; Dreis CD; Sham YY; Vince R; Pommier Y; Wang Z 6-Benzoyl-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones as Dual Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase and Integrase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 21, 2400–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tang J; Liu F; Nagy E; Miller L; Kirby KA; Wilson DJ; Wu BL; Sarafianos SG; Parniak MA; Wang Z 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones as Selective Active Site Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H: Design, Synthesis, and Biochemical Evaluations. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 2648–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wang L; Tang J; Huber AD; Casey MC; Kirby KA; Wilson DJ; Kankanala J; Parniak MA; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ 6-Biphenylmethyl-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones Potently and Selectively Inhibited HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 156, 680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wang L; Tang J; Huber AD; Casey MC; Kirby KA; Wilson DJ; Kankanala J; Xie JS; Parniak MA; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ 6-Arylthio-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones Potently Inhibited HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H with Antiviral Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 156, 652–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Tang J; Do HT; Huber AD; Casey MC; Kirby KA; Wilson DJ; Kankanala J; Parniak MA; Sarafianos SG; Wang Z Pharmacophore-Based Design of Novel 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione Subtypes as Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H: Tolerance of a Nonflexible Linker. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2019, 166, 390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Tumey LN; Bom D; Huck B; Gleason E; Wang J; Silver D; Brunden K; Boozer S; Rundlett S; Sherf B; Murphy S; Dent T; Leventhal C; Bailey A; Harrington J; Bennani YL The Identification and Optimization of a N-Hydroxy Urea Series of Flap Endonuclease 1 Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2005, 15, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Kankanala J; Kirby KA; Huber AD; Casey MC; Wilson DJ; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluations of N-Hydroxy Thienopyrimidine-2,4-diones as Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase-Associated RNase H. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2017, 141, 149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Wu BL; Tang J; Wilson DJ; Huber AD; Casey MC; Ji J; Kankanala J; Xie JS; Sarafianos SG; Wang ZQ 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione-5-N-benzylcarboxamides Potently Inhibit HIV-1 Integrase and RNase H. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 6136–6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lapkouski M; Tian L; Miller JT; Le Grice SFJ; Yang W Complexes of HIV-1 RT, NNRTI and RNA/DNA Hybrid Reveal a Structure Compatible with RNA Degradation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2013, 20, 230–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tian L; Kim MS; Li HZ; Wang JM; Yang W Structure of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Cleaving RNA in an RNA/DNA Hybrid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Corona A; Masaoka T; Tocco G; Tramontano E; Le Grice SF Active Site and Allosteric Inhibitors of the Ribonuclease H Activity of HIV Reverse Transcriptase. Future Med. Chem 2013, 5, 2127–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Massari S; Corona A; Distinto S; Desantis J; Caredda A; Sabatini S; Manfroni G; Felicetti T; Cecchetti V; Pannecouque C; Maccioni E; Tramontano E; Tabarrini O From cycloheptathiophene-3-carboxamide to oxazinone-based derivatives as allosteric HIV-1 ribonuclease H inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem 2019, 34, 55–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Baell JB; Holloway GA New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from Screening Libraries and for Their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Himmel DM; Sarafianos SG; Dharmasena S; Hossain MM; McCoy-Simandle K; Ilina T; Clark AD; Knight JL; Julias JG; Clark PK; Krogh-Jespersen K; Levy RM; Hughes SH; Parniak MA; Arnold E HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Structure with RNase H Inhibitor Dihydroxy Benzoyl Naphthyl Hydrazone Bound at a Novel Site. ACS Chem. Biol 2006, 1, 702–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]