Abstract

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic is spreading across the world. Many patients will not be suitable for mechanical ventilation owing to the underlying health conditions, and they will require a conservative approach including palliative care management for their important symptom burden.

Objectives

To develop a management plan for patients who are not suitable for mechanical ventilation that is tailored to the stage their COVID-19 disease.

Methods

Patients were identified as being stable, unstable, or at the end of life using the early warning parameters for COVID-19. Furthermore, a COVID-19–specific assessment tool was developed locally, focusing on key symptoms observed in this population which assess dyspnoea, distress, and discomfort. This tool helped to guide the palliative care management as per patients' disease stage.

Results

A management plan for all patients' (stable, unstable, end of life) was created and implemented in acute hospitals. Medication guidelines were based on the limitations in resources and availability of drugs. Staff members who were unfamiliar with palliative care required simple, clear instructions to follow including medications for key symptoms such as dyspnoea, distress, fever, and discomfort. Nursing interventions and family involvement were adapted as per patients' disease stage and infection control requirements.

Conclusion

Palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic needs to adapt to an emergency style of palliative care as patients can deteriorate rapidly and require quick decisions and clear treatment plans. These need to be easily followed up by generalist staff members caring for these patients. Furthermore, palliative care should be at the forefront to help make the best decisions, give care to families, and offer spiritual support.

Key Words: COVID-19, palliative, symptoms, emergency

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is rapidly spreading across the world. Many patients will present with a high symptom burden, which specialists in palliative care can help manage. Although the focus in the media has been on mechanical ventilation, increasing number of patients will not be suitable for this support because of underlying health conditions. Instead, they will require a conservative approach and palliative care management.

After two weeks of caring for inpatients with COVID-19 in a Swiss hospital near Northern Italy, treatment plans have changed dramatically. In part, this is due to competition for palliative care drugs, which are also used in intensive care unit. But these changes are also related to staffing. Health care workers are reallocated from their own specialities to care for patients with COVID-19, and palliative care is new to them. Hence, palliative care assessment and treatment recommendations need to be clear and simple to enact to achieve maximum palliation of symptoms. In addition, our decision making needs to be rapid, as patients are likely to deteriorate quickly. This is emergency palliative care. In this article, we describe the management plan for three types of patients who are not suitable for ventilation: stable, unstable, or at the end of life.

Categorization of Patients

We use early warning parameters1 to assess patients with COVID-19, as recommended by the World Health Organization.2 In addition, patients with a respiration rate of more than 25 per minute and saturations of <88% (irrespective of supplemental oxygen therapy) are categorized in the unstable category. As these patients deteriorate, they will be categorized as end of life.

Assessment and Treatment

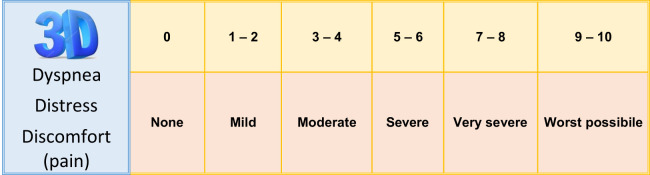

Assessment needs to be concise and quick as patients can deteriorate rapidly. Assessment guidelines and treatment plans for patients who are not suitable for life-sustaining therapies need to be shared with emergency department staff in particular, as patients present there, and palliative care teams may not be able to assess in time. Assessments are tailored to the additional time required because of limited contact due to infection control nursing requirements and reducing risk of contamination.3 A COVID-19-specific assessment tool was developed locally, the 3D-Ticino 2019-nCov Score, which focuses on key symptoms observed in this population, such as dyspnea, distress, and discomfort (pain). The tool is depicted in Fig. 1 . Pressure areas are also assessed and the need for pressure-relieving devices.

Fig. 1.

3D-Ticino 2019-nCov Score.

Our medication guidelines are based on the limitations in resources, particularly the availability of midazolam and fentanyl, and are presented for each category of patient in Table 1 . Each country will have their own preferred route of administration, dose, and second-line drugs and initially greater drug availability. Consider using oral and rectal routes of administration, especially in care homes or the community. In all cases, nonessential pharmacological treatments such as statins are temporarily stopped to prevent potential interactions with experimental COVID-19 disease-related therapies

Table 1.

Recommendations for Conservative and Palliative Care Management of COVID-19 Patients (3D-TiCoS)

| Phase of Illness | Monitoring (Nursing) | Drugs for Symptom Control |

|---|---|---|

Stable:

|

|

Dyspnea/pain: Morphine PO 2–5 mg, 4 hourly with rescue doses (10%–20% of the total daily dose) or PRN Anxiety: Lorazepam sublingual 1–2.5 mg, 8 hourly or PRN or Levomepromazine PO 5–10 mg, 6 hourly or PRN Fever: Paracetamol PO 1 g, 6 hourly or PRN Shivers: Morphine 2–5 mg IV/SC PRN or Pethidine 25–50 mg SC PRN Prescribing opioids in renal insufficiency: choose Hydromorphone (accordingly to palliative care consultation) Temporary de-prescribing of usual drugs |

Unstable:

|

|

Dyspnea/pain: Morphine IV/SC 5 mg, 2–4 hourly with rescue doses (10%–20% of the total daily dose) or PRN Anxiety/delirium/distress: Diazepam 2.5–5 mg IV or rectal 10 mg 8–12 hourly with rescue doses PRN or chlorpromazine 12.5–25 mg IV PRN or levomepromazione 6.25–25 mg SC PRN Fever: Diclofenac 75 mg IV with rescue doses PRN or paracetamol rectal 600 mg, 6 hourly Shivers: Morphine 5 mg IV/SC PRN or pethidine 25–50 mg SC PRN Hydration maximum 250 mL/day Suspend futile treatments |

End-of-Life:

|

|

Terminal dyspnea–Respiratory distress:

Shivers: Morphine 5 mg IV/SC PRN or pethidine 25–50 mg SC PRN |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; 3D-TiCoS = 3D-Ticino 2019-nCov Score; EWS1 = Early Warning Score and rules for 2019-novel coronavirus-infected patients; RR = respiratory rate; O2 sat = oxygen saturation; 3D = dyspnea, distress, and discomfort/pain (from Italian: Dispnea, Distress, and Dolori); Vital signs = blood pressure, oxygen saturation, pulse, and body temperature; PRN = pro re nata (as needed); PO = per os (by mouth); SC = subcutaneously; IV = intravenous; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ABDT2 = agitation, shivering (hyperthermia), distress, tachycardia, and tachypnea (from Italian: Agitazione, Brividi (ipertermia), Distress, Tachicardia e Tachipnea).

Stable Patients

Stable patients, although not suitable for intubation, may still recover. They have a high symptom burden, including dyspnea, fever, anxiety, and shivering. They have their Early Warning Score and the 3D-Ticino 2019-nCov Score assessment recorded each nursing shift. Pulse oximetry is more useful than listening to the chest, as some nondyspneic patients are still hypoxic and reduces risk of contamination. Dyspnea can be persistent or intermittent and managed with morphine.

Fever leads to excessive shivering, which causes discomfort. Shivers can be managed with morphine, and in some cases, pethidine has been used.

Anxiety is high as patients are nursed in isolation, and the diagnosis of COVID-19 is received as a death sentence. Lorazepam is helpful. Families also have high anxiety as they have minimal contact. In some hospitals, one visit is permitted in exceptional situations, but it is time consuming to dress families in personal protective equipment and risks greater contamination. This is difficult if families are in quarantine or unwell themselves. All families are told the patient is sick enough to die.4 Virtual visits have been possible. Chaplains take the lead on supporting and informing families.

Unstable Patients

A patient may present as unstable or deteriorate and become unstable. Deterioration can be rapid. Unstable patients are categorized by an increase in the Early Warning Score to more than 7 and decreased saturation levels below 88% irrespective of supplemental oxygen. These patients are not going to recover and need their symptoms managed. Some hydration is given to keep the patient comfortable as well as mouth care. The family needs to be informed of the change in situation, and it may be possible to arrange a visit. Visits are kept short (about 15 minutes) to reduce infection risk5

End-of-Life Patients

These patients have very low saturation levels and are dying. If the patient is unable to communicate each shift their restlessness, shivering (hyperthermia), distress, tachycardia, and tachypnea are assessed (ABDT2 from Italian Agitazione, Brividi [ipertermia], Distress, and Tachicardia e Tachipnea). Delirium is problematic, especially in combination with dementia, as it increases the contamination risk. Patients need sedation but because of limitations in availability of midazolam, creative solutions using diazepam, chlorpromazine, and levopromazine are used. Sedation is also used in the presence of hemoptysis, but hemoptysis is only experienced by a minority of patients.6 Oxygen therapy and other futile treatments are stopped, and comfort care is given. Oxygen in this context is not helpful to palliate symptoms as it does not improve hypoxic patients' comfort, rather opioids are more effective.7 In addition, the mask can cause discomfort especially for patients with delirium. If possible, a visit from the family is arranged. We would not recommend virtual contact with families using Skype or another online system as our experience is at this point as they find it too distressing.

Conclusion

Palliative care teams, intensivists, and internal medicine specialists all work side by side as palliative care is recognized to be at the forefront of this crisis, as it can offer symptom management, support to families, and spiritual care. Most patients with COVID-19 need palliative care input because of the large symptom burden and need for clear and open communication with patients and their families. However, because of the potential for rapid deterioration, decisions need to be made quickly, and treatment plans need to be clear and simple to follow for the generalist staff caring for them. Care of patients with COVID-19 results in huge ethical dilemmas and a toll on the health care teams caring for them, not least from shortages in resources, both staffing and pharmaceutical. Palliative care needs to adapt to an emergency style of palliative care and be at the forefront to help make the best decisions, give care to families, and find spiritual support.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians . Royal College of Physicians; London: 2017. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected Available from.

- 3.Sun Q., Qiu H., Huang M., Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver D. David Oliver: what to say when patients are “sick enough to die”. Br Med J. 2019;367:l5917. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghinai I., McPherson T.D., Hunter J.C. First known person-to-person transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the USA. Lancet. 2020;395:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30607-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Characteristics of COVID-19 patients dying in Italy: report based on available data on March 20th, 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_20_marzo_eng.pdf Available from.

- 7.Clemens K.E., Quednau I., Klaschik E. Use of oxygen and opioids in the palliation of dyspnoea in hypoxic and non-hypoxic palliative care patients: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;17:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]