Abstract

Purpose of review:

This review describes social determinants of HIV in two geographic and epidemic settings, the Dominican Republic (DR) and Tanzania, among female sex workers (FSW), their influence on HIV outcomes including 90-90-90 goals, and the development and impact of tailored, context driven, community empowerment-based responses in each setting.

Recent findings:

Our review documents the significance of social determinants of HIV including sex work-related stigma, discrimination and violence and the impact of community empowerment-based approaches on HIV incidence in Tanzania and other HIV prevention, treatment and care outcomes, including care engagement and adherence, in the DR and Tanzania.

Summary:

Community empowerment approaches where FSW drive the response to HIV and strategically engage partners to target socio-structural and environmental factors can have a demonstrable impact on HIV prevention, treatment and care outcomes. Such approaches can also support further gains towards reaching the 90-90-90 across geographies and types of epidemics.

Keywords: HIV, sex work, social determinants, stigma, violence, community empowerment

Introduction

Progress is being made on reaching the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals (1, 2), namely that by 2020, 90 percent of all people living with HIV (PLHIV) will know their HIV status, 90 percent of all people with HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy and 90 percent of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) will be virally suppressed. However, important challenges remain. As was acknowledged when the goals were set and is documented in a recent UNAIDS report, stigma and discrimination present considerable barriers to achieving the 90-90-90 goals (1, 2). HIV prevalence among key populations such as female sex workers (FSW), men who have sex with men, transgender women, and people who use drugs, often highly stigmatized and marginalized groups, is often 10–15 times higher than the general population in any country setting (3). In many contexts, half or more than half of individuals within a key population are infected with HIV (3). Marginalized populations are also much less likely to know their status, be on ART and be virally suppressed (4–6). Modeling suggests that even when the 90-90-90 goals are reached through universal test-and-treat interventions at a population level, high country and regional HIV incidence will persist if key and marginalized populations are not equitably engaged in care and virally suppressed (6).

Social determinants such as intersectional stigma, discrimination and violence, poverty and gender inequality heighten vulnerability to HIV infection as well as inhibit optimal care and treatment outcomes such as those articulated in the 90-90-90 goals. Among FSW, for example, social determinants are foundational to high HIV prevalence and difficulties achieving positive care outcomes (7, 8). FSW are subject to multiple forms of stigma and discrimination related to their occupation, gender, socioeconomic position and often their HIV status (7). Such intersectional stigma may be enacted by community members, family and friends, government agencies and health care facilities (9). Stigma and discrimination encountered by FSW underlie their exposure to multiple human rights violations including high rates of physical and sexual violence from sexual partners, community members and from state actors such as police (7). Stigma, discrimination and violence impede the human rights of FSW including their right to health care and lead in turn to high incidence and poor treatment outcomes (7). HIV prevalence among FSW is 13.5 times the overall prevalence among the general population of women 15–49 years old and access to HIV prevention services is low, with less than 50% of FSW reporting access to basic prevention services (10). In terms of the 90-90-90 goals, it is estimated that antiretroviral use among FSW living with HIV is just above a third (38%) and just above half of FSW living with HIV (57%) are virally suppressed (11).

As Shannon and colleagues outline, effective responses to HIV acquisition and transmission risks among FSW must address “high-order” determinants such as stigma and violence (8). While they acknowledge a dearth of mathematical modeling studies on the population level effects of structural interventions, they note the unique promise shown by community empowerment and mobilization interventions which are cost-effective and show a reduction of new infections by 17–40% across a variety of epidemic settings (8). A recent systematic review led by Kerrigan and colleagues, including researchers and members of the sex-worker community, underscores the effectiveness of a community empowerment-based response to HIV among FSW (9). This review showed significant reductions in HIV, including a 32% reduction in the odds of HIV infection, and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) among FSW and a 3-fold increase in condom use when a community empowerment-based response to HIV was employed (9). As Kerrigan and colleagues explain, a community empowerment-based response is one in which the impacted population, in this case, FSW, address social and structural barriers to their overall health and human rights through collective ownership and engagement in the design of interventions and programs focused on reducing HIV risk and improving HIV outcomes (9). Community empowerment approaches among FSW are recommended globally for HIV prevention by the World Health Organization (WHO) (12) and are a UNAIDS Best Practice (13).

In two epidemic settings, we have conducted formative work to assess the landscape of social determinants of HIV among FSW. In partnership with the sex worker community in each setting, we developed a community empowerment response to address barriers to optimal HIV prevention, treatment and care outcomes. In this review, we will examine both formative and intervention research conducted in two distinct socio-political and epidemic settings, the Dominican Republic (DR) and Tanzania. The purpose of this review is to: 1) share assessments of underlying social determinants and their association with HIV prevention, treatment and care outcomes in each setting; 2) provide detail on the development of tailored, context driven, community empowerment-based response to these assessments; 3) consider the impact of this response in each setting; and 4) explore implications of our findings for an evolving and nuanced understanding of the role that social determinants of HIV play in reaching the 90-90-90 as well as how to adapt community empowerment-based approaches to emerging and novel elements of combination HIV prevention and treatment as prevention approaches.

The nexus of social determinants and HIV outcomes among FSW in the DR

We have been working with FSW in the DR since 1996. Early work focused on adapting environmental-structural approaches that had been successful in increasing condom use in other global settings to the Dominican context where sex work was previously largely establishment-based. Our first intervention research project implemented in 1999–2000, Compromiso Colectivo (Collective Commitment), involved two environmental-structural interventions aimed at reducing the risk of HIV infection and STIs among FSW. Formative research engaged FSW, male paying clients and non-paying steady partners, sex work establishment owners and staff and governmental and nongovernmental (NGO) stakeholders with the aim of stimulating an environment that enabled HIV/STI risk reduction including condom promotion in sex work establishments (14). A pre-intervention mixed methods assessment conducted as part of the intervention found that environmental-structural support structures for condom use and HIV/STI prevention were organically in place in some establishments and where those supports and solidarity were greater, so was the level of consistent condom use between FSW and their regular clients (14). This early work underscored the importance of socio-structural determinants and of nurturing solidarity between FSW and establishment owner/managers/staff and engaging government actors to address FSW‟s HIV risk.

Building on insights from Compromiso Colectivo and recognizing the need to include FSW living with HIV in efforts to address structural and social determinants of HIV and facilitate community empowerment, we developed a community driven, multi-level intervention called Abriendo Puertas (Opening Doors) which was implemented among a cohort of 250 FSW living with HIV. At baseline in 2011–2012, we found that our participants experienced significant levels of both HIV and sex work stigma, discrimination, and violence (15). In qualitative work conducted with a sub set of the cohort, women noted that they had experienced these intersecting stigmas and discrimination from multiple actors including governmental authorities such as police or health care providers as well as employers and community members (16). Almost a fifth (18.3%) of had experienced intimate partner violence in the last six months (17). Working in a sex work venue environment where alcohol and substance use are prevalent created additional structural risk. Nearly half of the sample (46.8%) reported using alcohol sometimes or always before having sex and nearly a quarter reported prior drug (15).

Documented social determinants were tied to challenges in HIV care continuum outcomes. Women who scored higher on an internalized sex work stigma scale were more likely to have an interruption in HIV treatment (AOR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.16) and significantly lower odds of retention in care (AOR: 0.93; 95 % CI: 0.88, 0.98). Women who experienced sex work-related discrimination were more than three times more likely to experience treatment interruption (AOR: 3.24, 95% CI: 1.28, 8.20) (18, 19). Positive perceptions of HIV care providers led participants to have a significantly higher odds of being retained in care (AOR: 1.17; 95 % CI: 1.10, 1.25) (18).

Experiences with violence were also associated with greater difficulty in reaching the 90-90-90. Intimate partner violence in the last six months was significantly associated with not currently being on ART (AOR: 4.05, 95% CI: 1.00, 16.36) and missing an ART dose in the last 4 days (AOR: 5.26, 95% CI: 1.91, 14.53). Client violence was tied to not having received HIV care in the last 6 months (AOR: 2.85, 95% CI: 1.03, 7.92) and having interrupted ART (AOR: 5.45, 95% CI: 1.50, 19.75) (17).

Substance use was also found to limit women‟s engagement along the HIV care continuum. Women who had ever used drugs were more likely to have a detectable viral load (AOR: 2.34, 95% CI 1.14,4.79) (15) while women who reported any drug use in the past six months were less likely to be retained in treatment (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.13,1.01) (18). Women who reported any alcohol consumption in the last month were also less likely to be retained in HIV treatment (AOR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.92) (18). Baseline analyses from this multi-level community-empowerment cohort underscore the impact of stigma, discrimination, violence and an environment conducive to alcohol and drug use on HIV care continuum outcomes.

The nexus of social determinants and HIV outcomes among FSW in Tanzania

Since 2011, we have been working with FSW in the Iringa region of Tanzania. Our work in the DR reinforced the importance of addressing multiple barriers to prevention and treatment across levels faced by FSW, holistically and regardless of HIV status. Our mixed methods formative work in Tanzania revealed again the prevalence and impact of social determinants on HIV risk and care. FSW were recruited from venues in which sex work occurs and reported frequent experiences with stigmatization from the community as well as self-stigmatization. Additional interviews with local stakeholders including health care workers and government officials highlighted the interplay of HIV and sex work stigma where sex work and the venues in which sex work occurs were seen as drivers of the HIV epidemic in Iringa (20). Concerns about being stigmatized or treated poorly in clinic settings made many FSW participants reluctant to seek HIV testing and care (20–22). Participants detailed verbal abuse and physical and sexual violence perpetrated by patrons at venues, clients and intimate partners and the ways in which violence increased risk by preventing condom use (23). Women also noted the impact of alcohol on violence and HIV risk. In-depth interviews revealed alcohol consumption to be an integral component of venue-based sex work where refusal to accept a drink from a client, could result in violence or losing a client (20, 23, 24). FSW described during in-depth interviews the connection between poverty, sex work and HIV-related risk. The majority of participants had one or more financial dependents and perceived their own financial security as fair or poor (25). Poverty and the need to provide for a family were primary reasons to engage in sex work and FSW sometimes engaged in unsafe sex including sex without a condom to receive higher payment (20, 25).

In 2015, we established a cohort of 496 FSW (293 HIV-negative and 203 HIV-positive) for participation in a community randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of a comprehensive community empowerment-based combination prevention intervention in Iringa. Baseline prevalence for our cohort was high at 40.9%, while engagement in the HIV care continuum was low (26), as measured against the 90-90-90. Of those who tested positive at baseline, only a third (30.5%) knew that they were living with HIV. Of those who were aware of their status, just above two thirds (69.4%) reported being on ART and of those, just above two thirds were virally suppressed (69.8%) (26).

Nearly half of the cohort (48.6%) had experienced at least one form of stigma associated with being a sex worker while half had ever experienced some form of gender-based violence (GBV) (50.8%) (26). Among participants living with HIV, 33.1% had experienced GBV in the last 6 months and this was significantly associated with a reduction in ART adherence in the last 4 days (AOR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.99) (27). Substance use which was predominantly alcohol use, during sex work, was significantly associated with being infected with HIV(AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.04, 2.53) and among those living with HIV, not being virally suppressed (AOR: 0.31; 95% CI: 0.09, 1.06) (26). Nearly half (42%) of our participants reported being frequently intoxicated during sex work in the past 30 days (23). Finally, lower income per sex work encounter was significantly associated with having HIV (AOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.96) (26). In the Tanzanian context, as in the DR, stigma and discrimination were highly prevalent and substance use was associated with challenges meeting the 90-90-90 goals. In Tanzania, gender-based violence was strikingly high and the role of poverty in HIV risk was particularly salient.

Developing community empowerment interventions for FSW in the DR and Tanzania

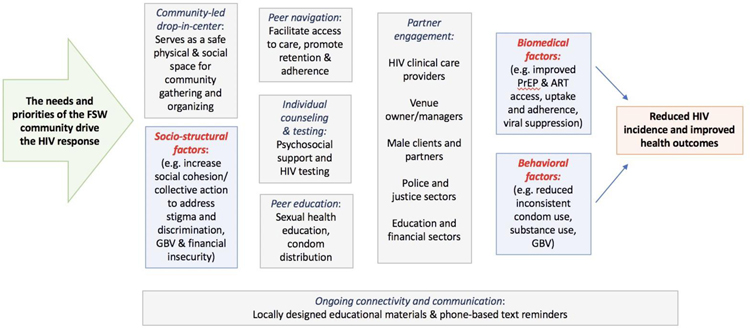

Formative research conducted in both settings around barriers and facilitators to achieving the 90-90-90 goals informed the contours of the community empowerment-based interventions developed in partnership with the respective sex worker communities in the DR and Tanzania. Principles of health and human rights are foundational to community empowerment approaches as is the collective ownership of impacted communities in developing programs that address the barriers they experience in trying to fully access their health and human rights. Our work in the DR was conducted under these fundamental concepts, which were later formally recognized in the Sex Worker Implementation Tool (SWIT) developed in 2013 by the United Nations agencies and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (12). The SWIT stresses the importance of facilitating solidarity and capacity building among impacted communities and engaging stakeholders through strategic partnerships. The SWIT also notes the need for programs flexibility. In Tanzania, our work was guided both by the principles of the SWIT as well as our experiences in the DR developing context-driven community empowerment-based combination prevention interventions (28). Figure 1 shows the community empowerment-based response to HIV that we have adapted in each setting with detail on each component of the model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of community empowerment response to HIV among FSW1

1. FSW (Female Sex Worker); GBV (Gender Based Violence); PrEP (Pre-exposure Prophylaxis); ART (Antiretroviral Therapy).

In the DR, our first collaborative intervention, Compromiso Colectivo, reflected efforts already conducted by a local NGO, Centro de Orientación e Investigación Integral (COIN) and Centro de Promocion de Salud (CEPROSH) to train FSW peer educators in collaboration with the sex worker rights group, Movimiento de Mujeres Unidas (MODEMU). This community-led outreach, health education and social support was grounded in a rights-based approach in which sex work is viewed as work and FSW are empowered to advocate for their labor rights, including safe working conditions. Significant formative work with FSW, clients, sex work establishment/venue owners and staff, and government and NGO stakeholders informed development of an environmental–structural intervention which was implemented in two distinct regions of the country. Each setting received the following four intervention components: solidarity and collective commitment (regular workshops and meetings with FSW and establishment owners and staff); environmental cues (condom promotion); quality tailored clinical services (provider sensitivity training and peer educators); monitoring and encouraging adherence, e.g. to intervention components. One community received an additional intervention component, government policy which required condoms to be available and used by clients in participating sex establishment as indicated by a regional health policy. A local implementing NGO monitored their progress against establishment based outcomes (29).

Abriendo Puertas, the follow up intervention for FSW living with HIV in the DR, built on the model of Compromiso Colectivo and was shaped by formative research including in depth interviews and focus groups with FSW living with HIV and key informants such as HIV service providers. Findings highlighted concerns with stigma and discrimination as well as financial insecurity including the costs of clinic transportation and costs of other health services and medicines, and poor quality HIV services (16). In response to these findings, a community-driven, multi-level intervention was developed and included four components: individual counselling and health education; peer led healthcare navigation and support, sensitivity training for clinical care providers; and community solidarity and mobilization activities in a community-led drop-in center (DIC). MODEMU led casas abiertas (open houses) in the DIC. Topics reflected concerns raised in formative research and during the intervention such as layered stigma and discrimination related to HIV and sex work, low social support, financial security and exploring partnerships to start micro-businesses, resources available for people living with HIV, and challenges taking care of a family member living with HIV.

Our experiences in the DR, including the importance of the value of FSW led programming and building partnerships with key stakeholders, along with formative work and engagement with members of our Community Advisory Board (CAB), led to the development of a community empowerment-based combination HIV prevention intervention, Project Shikamana (Let‟s Stick Together) in Iringa, Tanzania. Project Shikamana had five elements including: mobilization activities in a community-led DIC; sensitivity training for health care providers; venue based peer education with HIV testing and counseling and condom distribution; peer navigation and support for HIV prevention, care and treatment services and SMS text messaging tied to each element of the intervention. As in the DR, programming at the DIC reflected concerns raised by FSW in formative interviews which included sex work stigma and discrimination, managing violence from clients and police, sex worker human and labor rights, and financial security and business development. Programming and activities at the DIC also reflected ongoing input from the CAB, peer navigators and participants (20). For example, in the Iringa region of Tanzania, informal networks and savings groups (michezo) of FSW are common and a means of addressing shared concerns such as client violence or money management and financial security (25, 30). Peer navigators and participants with an interest in formalizing this model within the framework of Project Shikamana formed sex worker community savings groups and violence prevention groups to address these shared challenges that met weekly in the DIC and used materials from DIC programming to support discussion and action.

To ensure stakeholder support of Project Shikamana, our study team initiated contact with local government health officials very early on in the process of intervention planning and throughout intervention implementation. These relationships laid the foundation for provider sensitivity trainings at local healthcare facilities that encouraged collaborative problem solving around barriers to healthcare access that FSW face and welcomed the active participation of FSW peer navigators. We also added a police sensitivity training as the intervention rolled out in response to concerns raised by the FSW community about experiences with human rights abuses from police. Finally, peer educator/navigators were integrally involved in every component of the community empowerment-based intervention. In addition to navigation, they conducted venue outreach and education, and led DIC workshops and sensitivity trainings. Their investment in Project Shikamana and its success underscore the value of a sex worker-led intervention.

The impact of community empowerment responses to social determinants on HIV outcomes including the 90-90-90

In our early work in the DR implementing Compromiso Colectivo among FSW who were HIV negative, we found that participation in a community solidarity intervention was significantly associated with increases in condom use with new clients (OR: 4.21; 95% CI:1.55, 11.43) and that participation in an intervention that combined community solidarity with a government policy intervention was associated with significant increases in condom use with regular partners (OR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.33, 6.66) and in participants verbal rejections of unsafe sex (OR:3.86; 95% CI: 1.96, 7.58), as well as significant reductions in STI prevalence (OR:0.50; 95% CI: 0.32, 0.78) (31). Participating establishments in the community that received this integrated community solidarity and government policy intervention were also significantly more likely to achieve a study goal of no STIs in routine monthly screeners for FSW (OR:1.17; 95% CI:1.12, 1.22). We also found that participants that reported a high level of exposure to the intervention were significantly more likely than participants without such exposure to have used condoms consistently with all sex partners in the past month (OR:1.90; 95% CI:1.12, 3.21) (31).

In our follow up research with FSW living with HIV during Abriendo Puertas, we found significant improvements in the HIV care continuum among those who participated in the intervention. Engagement in care (86% to 95% (p<0.001)) and adherence to ART over the last 4 days (72 to 89 % (p<0.001)) increased significantly while interrupted treatment declined significantly (35.6% to 17.2% (p<0.001) (32, 33). Exposure to a high/moderate intensity of the intervention was associated with significantly greater odds of ART adherence at follow up (AOR: 2.42; 95 % CI: 1.23,4.51). Women exposed to high/moderate intensity of the intervention also had a significantly higher odds of protected sex in the last 30 days (AOR: 1.76, 95 % CI: 1.09, 2.84). Participants in the intervention reported significantly less drug (7.5 to 3.5 % (p = 0.013)) or alcohol use (47% to 40 % (p = 0.034)) before sex at study follow-up (32, 33). In qualitative research, participants provided insights into the processes which supported improvements in engaging in care and adhering to ART (16).

Participants explained that through participation in casas abiertas they were able to move from feeling alone in their struggle with HIV infection to overcoming self and societal marginalization by building social cohesion (16). Cohesion facilitated positive narratives around courage, strength, resilience and agency for FSW living with HIV to “fight for their lives and provide for their loved ones” (16). Participants articulated a growing sense that life was worth living and that HIV did not define them. This evolution in how women viewed themselves and HIV was tied to embracing health seeking behaviors such as engaging in HIV medical care and adherence to HIV treatment (16). These findings in aggregate from the DR suggest that interventions that engage FSW and other stakeholders in a collaborative effort to target socio-structural environmental factors and nurture social cohesion can have a demonstrable impact on HIV care continuum outcomes from prevention through the 90-90-90.

Findings from our research in Tanzania, the first trial of a community empowerment-based combination HIV prevention intervention for FSW in sub Saharan Africa, also show the promise of participation in community empowerment-based interventions. Among HIV negative participants, women in the intervention community were significantly less likely to become infected with HIV at the 18-month follow-up study visit (OR 0.38; P = 0.047), with a cumulative HIV incidence of 5.0% in the intervention community vs. 10.4% in the control community (34). Women in the intervention community also reported significantly lower rates of inconsistent condom use. Among participants living with HIV, women in the intervention community had higher rates of engagement in care and treatment than in the control community. They were more likely to have ever been in care (RR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.15–1.81), currently be in care (RR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.18–1.91), have ever been on ART (RR:1.22, 95% CI: 1.02,1.46), currently be on ART (RR:1.28, 95% CI: 1.05,1.55) and of those currently on ART, currently adhering to ART (RR:1.21, 95% CI: 1.00,1.46) (35). Adherence to ART in the last 4 days was significantly higher at follow up in the intervention (71.4%) versus the control (46.2%) arm (RR: 1.54; P = 0.002) (34). In the intervention community, at follow-up 79.1% of participants were linked to care vs. 55% in the control arm (RR: 1.44; P = 0.002), 81.3% % of participants were on ART at follow-up in the intervention arm vs. 63.8% in the control arm (RR: 1.27; P = 0.013) and 50.6% of individuals were virally suppressed in the intervention community compared to 47.4% in the control community (34).

Increasing intervention exposure was tied to significantly improved care continuum outcomes. For example, significant associations were seen with medium and high levels of exposure (compared to lower levels of intervention exposure), and engagement in HIV care in the last six months (RR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.12,3.07 and RR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.31, 3.51 respectively); currently being on ART (RR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.08, 2.71 and RR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.24, 3.02 respectively); and reported adherence within the last 4 days (RR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.04, 3.26 and RR: 2.24; 95% CI: 1.29, 3.90 respectively) (34). For participants with the highest level of exposure, significant associations with both reduced inconsistent condom use (RR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.42, 0.96) and increased viral suppression were observed (RR: 2.30, 95% CI:1.12,4.71) (34).

In qualitative research conducted after the completion of Project Shikamana, participants articulated the importance of a community led process that heard what participants needed and lead them to where they wanted to go (28). They valued the process of building solidarity and the opportunities it offered them to support each other through, for example, negotiations with clients or accessing HIV services. The formation of financial security and violence prevention groups which generated context specific solutions to addressing the barriers created by these social determinants are emblematic of the strength and sustainability of a process of building social cohesion. Partnerships created between peer navigators and health care providers and local police through sensitivity trainings further underscore the benefits that can arise from a thoughtful and deliberate process that is allowed to evolve organically (28). Findings from Project Shikamana suggest that effective, sustainable, context driven approaches to combination HIV prevention are possible in low-resource, high prevalence epidemics of sub Saharan Africa.

Conclusions

Our body of work on community empowerment-based approaches suggests the utility of further refining and expanding these models to address both the context within which risk and care occur as well as emerging HIV prevention and treatment options. For example, building on work discussed here, we are currently developing a valid and reliable aggregate measure of sex work-related stigma for use in the two distinct social and epidemic contexts of the DR and Tanzania. This work will also enable a better understand the relationship between HIV and sex work stigma and biological outcomes such as ART in the blood and viral suppression. We will also be able to assess other factors such as ART resistance and the potential contribution this may be making to reaching 90-90-90 goals in each setting. Indeed, a recent analysis of baseline samples among FSW living with HIV from our current work in the DR and Tanzania show that more than a third (39.1%) of women with viral loads greater than 1,000 copies/mL had HIV drug resistance and more than a fifth (21.0%) had multi-class resistance (36). Rigorous measures that can accommodate differences in settings and can be linked to biological outcomes will strengthen our interventions allowing us to address barriers to optimal prevention and treatment outcomes with greater precision and efficacy. Similarly, work could be done to better understand the complexities of violence and the extent to which the form of violence experienced and/or type of perpetrator may drive HIV prevention and treatment outcomes in different settings and contexts. Further, the interplay of violence with other behaviors (e.g. substance use) and dynamics (e.g. mobility and migration) also merits further work. We know from our cross-sectional work to date that substance use including alcohol use is intertwined with experiences of violence (23) and that mobility and migration can shape and increase experiences of violence among FSW (37).

We have recently adapted the Abriendo Puertas model for transgender sex workers as gender identity is another critically important contextual factor in both HIV risk as well as intervention design. Through this work, we aim to assess how an adapted community empowerment-based model operates against HIV outcomes and gain insight on how to further tailor a response to the context of the transgender sex worker community. How we measure social determinants, how we understand the complex ways in which these social and behavioral factors operate on HIV prevention and treatment outcomes longitudinally and in different sub populations of sex workers, and how they can be addressed through strategic interventions, will ultimately determine our ability to make meaningful and lasting progress towards the 90-90-90 goals.

It will also be important to use the power of community empowerment-based interventions to test optimal methods for introducing new biomedical HIV prevention and treatment modalities to marginalized and vulnerable key populations. We are currently in the process of incorporating pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into Project Shikamana for our HIV negative participants. Working with FSW and community stakeholders including the Project Shikamana CAB, we are designing a rights-based, community driven model for introducing PrEP that will be tested against a standard of care approach. Other innovations such as self-testing or long acting formulations of ART or PrEP would also be candidates for inclusion and assessment within a community empowerment-based model. We have begun to conduct formative research regarding injectable forms or PrEP and ART among FSW in each setting. Ensuring access to these innovations for key populations, particularly vulnerable women, is critical to our ultimate success against each region‟s epidemic but must reflect the deliberate and thoughtful assessment of underlying barriers and the development of community-driven approaches that address these barriers.

Finally, we anticipate that the components of a community empowerment-based model itself may evolve where we look to further improve our progress against HIV prevention and treatment outcomes. While better measurement and conceptualization of social determinants and innovations around prevention and care modalities is essential, we also want to evaluate whether other emerging interventions may be effectively incorporated into multi-level community empowerment-based models. For example, the challenge of sustained undetectable viral load may lead us to more fully understand how we can support and strengthen adherence beyond intervening against social determinants. We have recently found in our work in the DR and Tanzania that higher scores on a mindfulness measure were associated with higher engagement in care and adherence to ART and reduced HIV stigma in the case of the DR (38). These kinds of investigations, which support continued innovation to refine the current model itself, are also necessary as we work to develop interventions that allow for the highest degree of efficacy.

To reach the 90-90-90 and ultimately epidemic control, the needs of the “10–10-10”, including vulnerable and marginalized populations such as FSW who are particularly impacted by social determinants, must be addressed (39). Community driven responses have shown efficacy among FSW across settings and will continue to be critical in improving both HIV outcomes and the broader health and human rights of sex workers and other key populations globally.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Compliance with Ethical Standards Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Deanna Kerrigan, Center on Health, Risk and Society, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20016-8012.

Yeycy Donastorg, Instituto Dermatologico y Cirugia de la Piel, Calle Albert Thomas, 66, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

Clare Barrington, Department of Health Behavior, UNC, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599.

Martha Perez, Instituto Dermatologico y Cirugia de la Piel, Calle Albert Thomas, 66, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

Hoisex Gomez, Instituto Dermatologico y Cirugia de la Piel, Calle Albert Thomas, 66, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

Jessie Mbwambo, Muhimibili University of Health and Allied Sciences, 9 United Nations Road, P.O. Box 65001, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Samuel Likindikoki, Muhimibili University of Health and Allied Sciences, 9 United Nations Road, P.O. Box 65001, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Andrea Mantsios, Center on Health, Risk and Society, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20016-8012.

S. Wilson Beckham, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Anna Leddy, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 533 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143.

Tahilin Sanchez Karver, Center on Health, Risk and Society, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20016-8012.

Noya Galai, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Wendy W. Davis, Center on Health, Risk and Society, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20016-8012.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Communities at the Centre: Defending Rights, Breaking Barriers, Reaching People with HIV Services. Global AIDS Update 2019. 2019.

- 3.Kerrigan D, Barrington C. Introduction In: Kerrigan D, Barrington C, editors. Structural Dynamics of HIV, Social Aspects of HIV: Springer International Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson M The first 90: the gateway to prevention and care: opening slowly, but not for all. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2019;14(6):486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin D, Zhang CY, He ZK, Zhao XD. How does hard-to-reach status affect antiretroviral therapy adherence in the HIV-infected population? Results from a meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortblad KF, Baeten JM, Cherutich P, Wamicwe JN, Wasserheit JN. The arc of HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: new challenges with concentrating epidemics in the era of 90-90-90. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2019;14(5):354–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerrigan D, Kennedy C, Morgan T, Reza-Paul S, Mwangi P, Win K, et al. Female, Male and Transgender Sex Workers, Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. Encylopedia of AIDS. 2015:pp 1–8.

- 8.Shannon K, Crago AL, Baral SD, Bekker LG, Kerrigan D, Decker MR, et al. The global response and unmet actions for HIV and sex workers. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):698–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerrigan D, Kennedy CE, Morgan-Thomas R, Reza-Paul S, Mwangi P, Win KT, et al. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):172–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerrigan D, Wirtz A, Baral S, Decker M, Murray L, Poteat T, et al. The Global HIV Epidemics among Sex Workers. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mountain E, Mishra S, Vickerman P, Pickles M, Gilks C, Boily MC. Antiretroviral therapy uptake, attrition, adherence and outcomes among HIV-infected female sex workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(9):e105645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO, UNFPA, UNAIDS, NSWP, The World Bank. Implementing comprehensive HIV/STI programmes with sex workers: practical approaches from collaborative interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDS. Best Practices on Effective Funding of Community-Led HIV Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, et al. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. Aids. 2003;17(3):415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donastorg Y, Barrington C, Perez M, Kerrigan D. Abriendo Puertas: baseline findings from an integrated intervention to promote prevention, treatment and care among FSW living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e88157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrasco MA, Barrington C, Kennedy C, Perez M, Donastorg Y, Kerrigan D. ‘We talk, we do not have shame’: addressing stigma by reconstructing identity through enhancing social cohesion among female sex workers living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(5):543–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendoza C, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, Perez M, Fleming PJ, Decker MR, et al. Violence From a Sexual Partner is Significantly Associated With Poor HIV Care and Treatment Outcomes Among Female Sex Workers in the Dominican Republic. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2017;74(3):273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zulliger R, Maulsby C, Barrington C, Holtgrave D, Donastorg Y, Perez M, et al. Retention in HIV care among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic: implications for research, policy and programming. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(4):715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zulliger R, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, Perez M, Kerrigan D. High Drop-off Along the HIV Care Continuum and ART Interruption Among Female Sex Workers in the Dominican Republic. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015;69(2):216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckham S, Kennedy C, Brahmbhatt H, et al. Strategic Assessment to Define a Comprehensive Response to HIV in Iringa, Tanzania Research Brief: Female Sex Workers. Baltimore, MD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layer E, Kennedy C, Beckham S, Mbwambo J, Likindikodi S, Davis W, et al. Multi-Level Factors Affecting Entry into and Engagement in the HIV Continuum of Care in Iringa, Tanzania. Baltimore, MD: Project Search: Research to Prevention/JHU/USAID; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Layer EH, Kennedy CE, Beckham SW, Mbwambo JK, Likindikoki S, Davis WW, et al. Multi-level factors affecting entry into and engagement in the HIV continuum of care in Iringa, Tanzania. PloS one. 2014;9(8):e104961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leddy AM, Underwood C, Decker MR, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Galai N, et al. Adapting the Risk Environment Framework to Understand Substance Use, Gender-Based Violence, and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Female Sex Workers in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leddy A, Kerrigan D, Kennedy C, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Underwood C. ‘You already drank my beer, I can decide anything’: using structuration theory to explore the dynamics of alcohol use, gender-based violence and HIV risk among female sex workers in Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2018:20(12):1409–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantsios A, Galai N, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Shembilu C, Mwampashi A, et al. Community Savings Groups, Financial Security, and HIV Risk Among Female Sex Workers in Iringa, Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2018:22(11):3742–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerrigan D, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Beckham S, Mwampashi A, Shembilu C, et al. Project Shikamana: Baseline findings from a community empowerment based combination HIV prevention trial among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2017(74 Suppl 1):S60–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizinduko M, Faini D, Ambroce T, Leddy A, Likindikoki S, Beckham S, et al. , editors. Gender-Based Violence Is Negatively Associated with ART Adherence among Female Sex Workers Living With HIV in Iringa, Tanzania Center for AIDS Research SSA Symposium; 2019; Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leddy AM, Mantsios A, Davis W, Muraleetharan O, Shembilu C, Mwampashi A, et al. Essential elements of a community empowerment approach to HIV prevention among female sex workers engaged in project Shikamana in Iringa, Tanzania. Cult Health Sex. 2019:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, Gomez B, Jerez H, Weiss E, et al. Combining Community Approaches and Government Policy to Prevent HIV Infection in the Dominican Republic. Washington, D.C.: Horizons/Population Council/USAID; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantsios A, Shembilu C, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Beckham S, Mwampashi A, et al. , editors. “When you don‟t have money, he controls you”: financial security, community savings groups, and HIV risk among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania. 21st International AIDS Conference; 2016 Jul 18–22; Durban, South Africa: Oral Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, Gomez B, Jerez H, Barrington C, et al. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American journal of public health. 2006;96(1):120–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerrigan D, Donastorg Y, Perez M, Zulliger R, Carrasco M, Fleming P, et al. Abriendo Puertas: Feasibility and Initial Effects of a Multi-Level Intervention among Female Sex Workers Living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. Baltimore, MD. : Project Search: Research to Prevention/JHU/USAID; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.**Kerrigan D, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, Perez M, Galai N. Abriendo Puertas: Feasibility and Effectiveness a Multi-Level Intervention to Improve HIV Outcomes Among Female Sex Workers Living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):1919–27.This study provides the first evidence of the efficacy of a community driven intervention to improve HIV outcomes, engagement in care and ART adherence, among FSW living with HIV.

- 34.**Kerrigan D, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Davis W, Mantsios A, Beckham SW, et al. Project Shikamana: Community Empowerment-Based Combination HIV Prevention Significantly Impacts HIV Incidence and Care Continuum Outcomes Among Female Sex Workers in Iringa, Tanzania. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2019;82(2):141–8.This study provides the first evidence of the efficacy of a community empowerment-based intervention to signficantly reduce HIV incidence among FSW in sub Saharan Africa.

- 35.Galai N, Mbwambo J, Likindioki S, Beckham S, Shembilu S, Mwampashi A, et al. , editors. Impact of a community empowerment-based combination HIV prevention model (Project Shikamana) on the HIV continuum of care among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania. 22nd International AIDS Conference; 2018 Jul 23–27; Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenawalt W, Fogel J, Clarke W, Breaud A, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, et al. , editors. HIV Drug Resistance in Female Sex Workers from the Dominican Republic and Tanzania. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 2020 March 8–11, 2020; Boston, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendrickson ZM, Leddy AM, Galai N, Mbwambo JK, Likindikoki S, Kerrigan DL. Work-related mobility and experiences of gender-based violence among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from Project Shikamana. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e022621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerrigan D, Sanchez Karver T, Davis W, Beckham SW, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, et al. , editors. Mindfulness, Mental Health, and HIV Outcomes Among Women Living with HIV in the Dominican Republic and Tanzania. 10th Anniversary Conference: Global Mental Health without Borders 2019 April 8–9; Bethesda, Maryland, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincent W, Sevelius J, Lippman SA, Linnemayr S, Arnold EA. Identifying Opportunities for Collaboration Across the Social Sciences to Reach the 10–10-10: A Multilevel Approach. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2019;82 Suppl 2:S118–s23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]