Abstract

Chronic diseases, like diabetes and heart disease, disproportionately impact women of color as compared to White women. Community-engaged and participatory approaches are proposed as a means to address chronic disease health disparities in minority communities, as they allow for tailoring and customization of strategies that align with community needs, interests, and priorities. While community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a framework that offers a clear set of principles to guide intervention design and development, the complexity and diversity of community contexts make it challenging to anticipate all of the possible pathways to implementation. This article describes the application of CBPR principles in the design and development of SHE Tribe (She’s Healthy and Empowered), a social network–based healthy lifestyle intervention intended to promote the adoption of sustainable health behaviors in underserved communities. Practical and specific strategies are described to aid practitioners, researchers, and community partners as they engage in community–academic partnerships. These strategies uncover some of the inner workings of this partnership to promote trust and collaboration and maximize partner strengths, with the aim to aid others with key elements and practical steps in the application of participatory methods.

Keywords: program planning and evaluation, behavior change, community-based participatory research, health research, partnerships/coalitions, women-s health

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases including heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes are the leading causes of death among women today (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Disparities exist between class and race; for example, Black and Hispanic women are 1.9 and 1.6 times as likely to develop diabetes compared to their White counterparts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, 2016a, 2016b). The prevalence of obesity is also highest among women of color, and due to its association with chronic disease, obesity has become a focus in health interventions through weight loss (Flegal, Kruszon-Moran, Carroll, Fryar, & Ogden, 2016; Kumanyika, 2008). A focus on weight loss alone minimizes other contributing factors to poor health and well-being. Studies show that risk of premature mortality among individuals who are overweight or obese (higher BMI ⩾25) and have good cardiorespiratory fitness is similar to those who have a healthy BMI, and there are similar findings for reduced cardiovascular risk in this group (Barry et al., 2014; Koolhaas et al., 2017; Lavie, McAuley, Church, Milani, & Blair, 2014; McAuley et al., 2012). Social determinants of health, the environment, interpersonal factors like social support, individual behaviors, and genetics all contribute to the risk of developing chronic diseases (Bauer, Briss, Goodman, & Bowman, 2014). Programs that focus on a broader context are needed to increase the sustainability of health outcomes among individuals and communities (Dodgen & Spence-Almaguer, 2017).

Empowerment theory offers a multilevel perspective to engage individuals, groups and communities in identifying and addressing health disparities (Wiggins, 2011). Rooted in empowerment-based perspectives, community-engaged approaches, like community-based participatory research (CBPR), offer a more holistic approach to improving health within a community (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). This enables community and research partners to use one another’s strengths to focus on the broader context of needs, assets, and resiliencies within communities together (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Wallerstein, Duran, Minkler, & Foley, 2005). Participatory methods produce programs that better align with community priorities, build capacity, and produce meaningful outcomes (Jagosh et al., 2012). While the principles of CBPR are clear, the details of partnerships and how they work together to develop programs or other community actions can be indistinct, in that they vary by context and maturity of relationships. What works in one partnership may not work for another, showing a need to tailor principles to honor the differences in community environments and priorities (Israel et al., 2003; Nelson, Harris, Horner-Ibler, Harris, & Burns, 2016).

Researchers and practitioners need to be flexible to make adjustments and changes to the research process along the way (Nelson et al., 2016). Furthermore, every partnership represents a unique composition of individuals with knowledge, experience, strengths, and assets. Maintaining flexibility in order to identify these competencies and use them to influence forward momentum will increase likelihood of success (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). This article describes the processes and strategies used to develop a new participatory partnership to address changes in a project. Specific examples of partnering and actions to help researchers and practitioners as they engage with communities are described.

BACKGROUND

At the center of a CBPR orientation to research are partnerships committed to transformation of communities (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). This transformation more often than not occurs through a long-term commitment by partners to the iterative processes that occur through multiple actions together over time (Israel et al., 2003; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006).

Two obesity projects using a CBPR approach were prioritized as part of a 5-year federally funded Center of Excellence to reduce health disparities and create synergy in the region to address obesity among women. One of the projects was funded as a research study and the other an outreach initiative, and each project was led by a different investigative team. The research-focused project concentrated on implementing and testing a culturally relevant faith-based Diabetes Prevention Program among African American women in churches (Kitzman et al., 2017), and the outreach-focused project was less defined and emphasized building community capacity to promote sustainable obesity prevention activities in underserved neighbourhoods in the same region. Initial efforts in the outreach initiative involved identifying health priorities in neighborhoods through town hall meetings and focus groups, and resulted in implementation of 12-to 16-week educational series that focused on responding to resident requests for nutrition and exercise programming. One neighborhood was chosen each year in Years 1 to 3. These programs were supposed to be sustained in the neighborhoods through community champions. The original intention of the Center of Excellence was for the research study and outreach initiative to overlap and inform one another. Over the first 3 years, multiple investigator changes limited these integration goals.

As the two projects progressed, each grew relationships with different community groups: the outreach initiative with Spanish-speaking residents and the research study with African American churches and residents; however, opportunities for collaboration or crossover in the region had not been identified missing the proposed goal of project integration. There were also challenges with sustainability within the outreach initiative. Each year the process of identifying needs and responding with programming was being replicated in a new neighborhood. While great partnerships had been formed, programs for health improvement had not continued even in those places that had selected community champions and created action plans. These limitations set the stage for embarking on a new approach to sustainable health promotion that resulted in the development of SHE Tribe (She’s Healthy and Empowered), a peer-led, social network–based women’s lifestyle intervention. This article documents the methods and strategies associated with the design and development of SHE Tribe.

STRATEGIES

In a recent critical review of participatory literature, five strategies were frequently mentioned to successfully engage community partners: creation of an advisory group, forming a written agreement, using group facilitation methods and techniques, hiring of community members, and communication through frequent meetings (Salsberg et al., 2015). All of these strategies and others were used to facilitate a new direction for the outreach initiative. In Year 4, leaders of both projects sought to strengthen participatory practices and identified the need for a new strategy to create crossover between groups and think differently about sustainability. The focus was to leverage the relationships that had been built in both projects and to develop a new program that would build expertise to stay within underserved communities to address obesity and improve health.

Forming the Design and Action Team

To leverage the relationships between the two projects, community members and liaisons from both projects came together to form an advisory work group, the Obesity Prevention Core Design and Action Team. The name was chosen to communicate a message of engagement and active partnering rather than solely giving advice. An application was created to garner interest from community members, community health workers, and lay leaders of other obesity prevention programs from the communities reached in Years 1 to 3. The proposed concept was to develop an innovative, evidence-informed, sustainable, train-the-trainer program as a flexible model that could be easily integrated into what community members already do in their lives. Together the team was formed with 10 women (4 public health professionals and 6 community members) of African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian race/ethnicities between the ages of 25 and 60 years and in various life stages (young mothers, early-mid career, professionals, and retirement).

The approach to this work was rooted in CBPR aiming for a mutually beneficial and participatory partnership. The women who came together each represented a different area of the community where previous work had been completed and held different perspectives from community liaison to lay health promoter, graduate student, nonprofit director, health professional, or researcher. These unique viewpoints helped the group see strengths and weaknesses of the previous work, and also look forward to identify strategies that worked and did not work, gaps in programs or services, and ideas for how to improve. The reality of the challenges to implementing programs in each neighborhood were described in detail, as well as those challenges from a research and implementation standpoint (see Table 1). Creative ideas that may have been based on programs in communities or academic learning were balanced with the reality of people’s lives and experiences of community members, as well as an informed history of what had previously been helpful or harmful in the community context.

TABLE 1.

Examples of the design and action team outputs

| What are the similarities of existing obesity prevention, intervention and wellness programs? | |

| • Diet and exercise weight-loss ocus | |

| • Accountability in group format | |

| • Program commitment is long (12–16 weeks) | |

| • Motivation fades over time | |

| • Groups provide encouragement and support | |

| • Actions focus on tracking and monitoring progress | |

| • Temporary results and habits, not lifelong | |

| • Great information and easy to understand | |

| What are the Challenges to implementing programs in neighborhoods? | |

| • Lack of access to healthy food | |

| • Poor walkability of neighborhoods | |

| • Multiple roles of women in homes | |

| • Need for transportation and childcare | |

| • Requires ongoing support after program ends (programs may not continue to be offered) | |

| • Language barriers | |

| • Technology may not be available or familiar | |

| • Research evolves changing health information and causing confusion to community members | |

| • Lack community resources | |

| • Limited resources | |

| What are the challenges to implementing intervention research studies? | |

| • Address community concerns while navigating university institutional review board | |

| • Collecting meaningful data to measure health outcomes with community members | |

| • Cost and feasibility | |

| • Sustainability of programs | |

| • Research changes and materials become dated quickly | |

| • Changes in leadership | |

| • Researchers lack knowledge of community history and associated context | |

| What are some ideas to keep/ add as we move forward with a new design? | |

| • Shorter programs (5–6 sessions) | |

| • Personally chosen goals versus assigned | |

| • Social and fun environment | |

| • Use technology for monitoring and feedback | |

| • Small, sustainable health behaviour changes versus big weight loss goals | |

| • Focus on overall wellness not just obesity | |

| • Smaller groups | |

| • Ability to share with friends and family | |

| • Opportunities for reflection and personal evaluation |

Partnership-Building Practices and Structure

Members of the team had different levels of preexisting relationships among one another. Each person involved had a connection to at least one other person in the group, which helped establish initial trust. While community members may not have known one university partner, they did know another team member, so they were able to engage initially based on the trust they had built with the known partner (proxy trust). These relationships also facilitated quicker connections between partners who did not know each other, creating familiarity and the ability to share with one another more openly from the beginning due to this proxy trust (Lucero et al., 2018). This set the stage for a team culture of listening and respecting others’ input.

Proxy trust or initial trust is not enough to sustain a partnership, so other strategies were used to help create an environment that would lend itself to open conversation and to increased confidence in the partnership. Since many community partners worked during the day, meetings were held during evening hours at a central location. Though child care was not provided, children were welcomed and given space in the large meeting room to stay occupied during the team discussions. The room was set up in either a circle or an open square to facilitate conversation and eye contact. Name tents were also used to increase familiarity. There was a shared meal at the beginning of each meeting, and initial conversations purposefully avoided meeting agenda items or other “business talk.” The team came to share each other’s personal milestones and share in celebrating these things together. In addition, there was a strong effort to start and end the meetings on time to respect the commitments of all partners. University and organizational partners were attending as part of their job descriptions and were therefore compensated for their time and effort. As this is not the case for community partners, partners were paid for their time during and outside meetings to work on communications or deliverables. These strategies helped create a low-pressure, welcoming environment and facilitate relationships and work among the partners.

Facilitated Engagement Activities

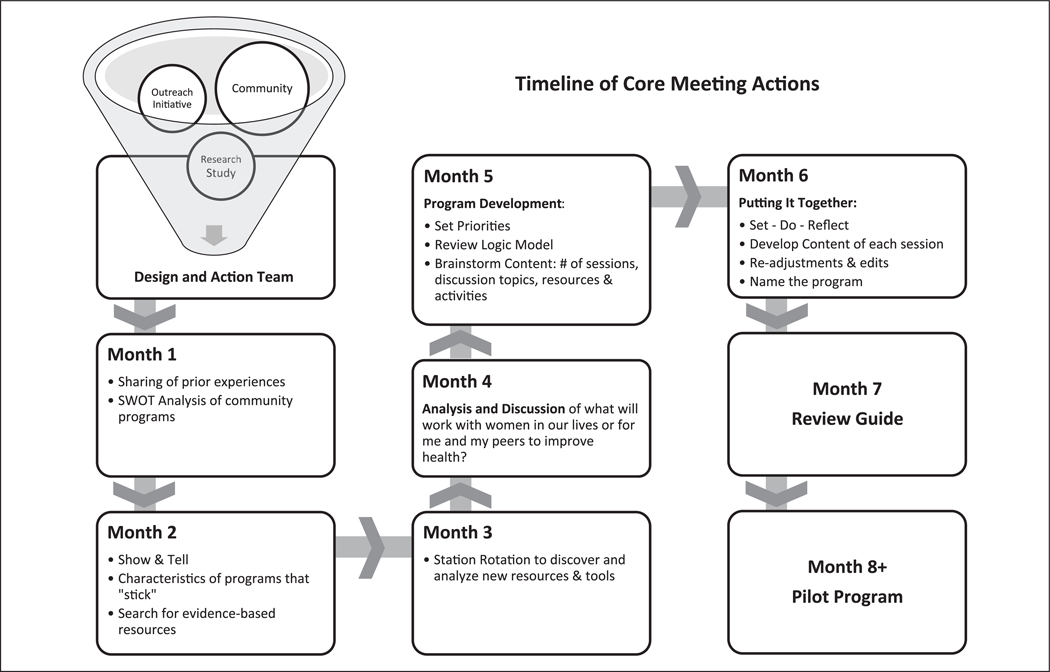

In building the partnership another integral part of each meeting was facilitated engagement and colearning. These techniques included the use of different activities and open-ended questions to draw out feedback from individuals in a group (Tucker et al., 2016). An emphasis on colearning helped equalize partner voices, gather knowledge, and share experiences to synthesize the information and direct the partnership (Salsberg et al., 2015). Several different activities were used throughout the meetings to facilitate group engagement (see Figure 1). Flip charts were used to help document facilitated conversations creating an easy way to both visualize and document common ideas or themes of discussions. In the first meeting, a university partner facilitated a SWOT analysis where members were urged to think about the characteristics of the obesity prevention and health programs in which each member had previous experience and recall the strengths (S), weaknesses (W), opportunities (O), and threats (T) of each. This activity helped communicate each person’s experience to the group, allowing partners to colearn from one another, and also gave information to begin thinking about a new framework for a more sustainable approach.

FIGURE 1. Timeline of core Meeting actions.

Another activity that facilitated group discussion was a Show & Tell. In one session, before coming to the meeting, group members were prompted to reflect on a health-focused resource that continues to successfully affect health personally, among friends and family, or has been successful in their previous program experience. At the meeting, each member presented their reflections, taking 5 minutes to discuss their resources and why they continue to be effective. A facilitator led the group in a discussion about the common elements that were present in these resources, highlighting key words like easy, supportive, enhanced motivation, reinforced previous knowledge or skills, and accountability. This activity prepared the group in reviewing evidence-based tools and resources while engaging in critical thinking and evaluation.

In another meeting, a station rotation was used to evaluate evidence-based resources and materials. Group members were given a worksheet for each resource, asking for feedback on the physical look of the material, readability, value for women, ease of use (for individual or program leader/facilitator), actionability (will people actually use it or engage in the behavior), and content that may be biased, offensive, or unrepresentative of the community. Partners rotated in pairs to each station and were given 10 to 12 minutes to review and critique the material before moving to the next station. When all individuals had visited each station, a group member led a discussion to debrief the activity together. Flip charts were used to document common elements perceived to promote success, which were then placed as priorities for the future program framework.

Coordinated Communication

Another key process to develop ongoing communication between meetings was through homework. The timeline for planning the program was approximately 6 months, so taking time to communicate between meetings was helpful for keeping the group engaged in the process. Assignments usually involved a set of questions to reflect on, a brainstorming activity, or a search via the Web or other resources. The topics expanded on what was previously discussed at a meeting or may have been a question to launch the group forward in thinking about women’s health. These topics were delivered through e-mail and responses collected through online surveys. Topics included the following: your “go-to” health information resource or strategy, a health habit, skill or item that has stuck with you over time, health issues of concern for women in your life, and helpful activities to communicate health information. At the beginning of each meeting, both university and community partners reported back to the group about their assignments.

Openness to New Paths

As the partnership developed, it became clear that obesity was not the primary concern of the group or the communities they represented. Obesity was too narrow of a topic to address all the concerns of women in these communities, and shifting to a lifestyle of health was viewed as beneficial for all the health conditions previously discussed. The partnership wanted to promote changes that are helpful for a lifetime and not simply focus on a certain behavior or one condition.

Previous programs were perceived to be lengthy, and there were concerns about sustaining motivation among community members. The concept of focusing on small, realistic health changes instead of drastic or big changes was voiced as a realistic way to adopt habits that could be continued for life. As these themes emerged, the word obesity was dropped from the partnership’s name, changing to simply the Design and Action Team. The direction of program planning shifted toward a holistic approach with wellness behaviors that encompassed multiple dimensions of health (mental, social, physical, spiritual, and environmental health).

Filtering and Organizing: Using Qualitative Research Skills With Vision

The charge of this partnership was to build capacity, while fulfilling the grant goals to address obesity among underserved women. Few limitations were put on the partners as they engaged in discussions and activities. There was a broad charge to think about women in their communities, and they knew that our deliverable needed to be a program or resource for women. This broad focus led to many moments during meetings where partners would ask, “Where are we going?” or “What are we supposed to be doing again?” as we got caught up in larger discussions of social, environmental, or political factors contributing to health. Leaving these conversations as they were without direction could become overwhelming; therefore, it was important for university partners to direct the iterative process in between meetings and to filter the themes that were occurring during sessions to accomplish the new direction and vision of the group. While this could be perceived as the university exerting power over community members to accomplish their own agenda, it was more an action to help deconstruct and reconstruct what was communicated by all partners in the meetings while listening for core themes. In this process of filtering, the essence of all partner voices were distilled so that work could continue and not become cluttered in the cacophony of enthusiastic voices around the table each meeting.

University partners had strengths in qualitative methods and used agendas, presentations, flip charts, notes, and recordings to distill themes that were repeated during meetings. Similar to qualitative analysis, the university partners would compile notes from meetings, identify themes, bundle conceptually similar ideas, and determine which components could be used to advance the progress of the intervention development. This process helped formulate the agenda for the next meeting. At the beginning of each meeting the core ideas that had been discussed would be presented and partners would propose new ideas and affirm, amend, or reject the themes, and then the next step would be taken to propel the conversation forward.

One example of filtering and organizing occurred after the SWOT analysis when core ideas were extracted and set as priorities for a new program. Another example happened after a review of evidence-based materials and reflecting on health needs of women in the community, when university partners came to the next meeting with a logic model and proposed creating the program structure around health domains mentioned in the previous meeting. A logic model was chosen for its simple structure and visual nature as a way to develop program components with community partners. Other planning models like PRECEDE-PROCEDE could also be used incorporating partners in the planning phases to gather data, interpret information, and design program features, but due to time constraints they were not used in this project (Green & Kreuter, 2005).

Using the logic model, partners began an iterative process to develop pieces of the program. Using flip charts, the partnership listed one domain on each chart then discussed what they would want to cover in discussing the topic in a module. Postmeeting, these charts were then filtered into core sections within a module: setting goals, doing activities to accomplish those goals, and reflecting on progress (set, do, reflect). The following meeting, partners used flip charts again to create content related to “set,” then “do,” and “reflect” portions for each domain. This content postmeeting was crafted into an outline for a facilitator guide that was reviewed in the next meeting. This process continued until a facilitator guide was created, and eventually, after brainstorming and voting on several options, the new program was named SHE Tribe. A checklist of strategies, actions, and tips for success is available in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Checklist of CBPR Strategies for Intervention design and development

| Strategy | Activities | Tips for Success |

|---|---|---|

| Forming the Design and Action Team | Identify purpose and duration of group | • Have a predetermined time commitment and anticipated end date of a work group |

| • Allow the group to select a name | ||

| Promote diverse participation (demographic, skills, experiential, etc.) | • Use both an open application process and outreach based on existing relationships | |

| • Communicate directly about the value and importance of different forms of expertise (research, experiential) | ||

| Promote partnership-building practices and structure | Engage in activities that build trust and familiarity | • Share meals as part of the planning process and allow time for social discussion |

| • Provide a welcoming space and be flexible with the presence of children | ||

| • Use name tents | ||

| Respect time and commitment made by community members | • Pay community members for their time | |

| • Start and end on time | ||

| • Identify convenient locations/times to meet | ||

| Offer facilitated engagement activities | Design activities that promote colearning | • Engage in a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of existing interventions or research studies |

| • Conduct Show & Tell activities where work group members propose and practice new ideas and share them with the full group | ||

| • Use station rotation to allow work group members to spend time reviewing existing evidence-based practices, discuss, and provide feedback | ||

| Provide Coordinated communication | Identify multiple methods of communicating with group members to move the agenda forward in between meetings | • Identify homework activities that work group members can complete independently |

| • Ask group members to provide feedback and ideas through surveys in-between sessions | ||

| Openness to new paths | Strike a balance between sufficient structure to accomplish work, with flexibility to innovate | • Recognize the importance of language use and terminology, considering how community members experience negative diagnostic–sounding labels |

| • Encourage solution-focused discussions that identify multiple pathways to achieve the same overarching goals of promoting healthy communities | ||

| Filter and organize information by using qualitative research skills with a vision | Maximize the research skills of university partners by having them distill information and ideas generated during meetings | • Qualitatively code ideas after each meeting with basic descriptive codes and grouped categories of codes |

| • Present distilled themes and examples back to the full work group each meeting to generate further insights |

NOTE: CBPR = community-based participatory research.

DISCUSSION

Reflecting on this partnership, one key to success was having prior relationships with someone involved in the project. The prior relationships made the transition into a larger group partnership easier through a mechanism of proxy trust (Lucero et al., 2018). This also meant that community members were familiar with the constraints and processes that are often present in these types of organizations (i.e., funding requirements, university policies, processes, and time lines, etc.). As time went on, relationships developed across all members, but these preexisting relationships helped partners listen and engage perhaps earlier than if this had been a group of strangers (Lucero et al., 2018).

Other helpful steps included having facilitation throughout the meetings to engage all voices in the project, creating a comfortable environment, taking time to develop relationships through sharing meals, encouraging active participation by all group members, and having respect for the time it took to develop the program. This was an iterative process, and while there was a time line in place, the group was able to take time and work with purpose, not rushing the development of ideas or products. The partnership was also able to shift directions, showing both trust and flexibility in the relationship (Wallerstein et al., 2005). The filtering and organization process that allowed for iterative development of the program and communication between meetings contributed to productivity and momentum in the partnership (Becker, Israel, & Allen, 2005; Israel et al., 1998).

Some limitations should be noted. First, this group was formed with a preconceived purpose from the grant that was funding the work of the university and community organization. Though informed by a local obesity prevention coalition, specific community members from the neighborhoods did not come up with the needs that were to be addressed through the partnership. This is a key feature of participatory projects, and the partners noticed early that obesity was not holistic or broad enough to encompass the focus of the community members (Israel et al., 1998). A change to a focus on wellness still met the objectives of the grant, honored the voices within the partnership, and showed that trust and flexibility were characteristics of the partnership (Wallerstein et al., 2005). This echoed a similar transition in another CBPR project where the emphasis shifted from weight loss to a “commonsense approach” to health and well-being (Nelson et al., 2016). Second, the partnership started with a focused project and therefore did not work through many of the steps that occur in relationships that are just starting off like discussing community needs and strengths or identifying areas of mistrust or addressing social inequalities (Becker et al., 2005; Israel et al., 1998; Salsberg et al., 2015; Wallerstein et al., 2005). Having established a trusting relationship and successfully beginning to pilot the work, there is momentum to think about long-term strategies to improve health in the region.

The strengths of this partnership are, first, that we were able to create crossover between two previous projects to continue work to improve health among women in underserved communities. Second, although not completely representing the CBPR approach, the partnership was successful in engaging community partners in a participatory way. Finally, the goal to create a program was achieved. These strategies could be implemented with multiple program-planning models, like PRECEDE-PROCEED, to pragmatically review data and gather information to jointly design programs (Green & Kreuter, 2005). Currently, this work has led to a clinical trial that is now under way.

CONCLUSION

Through this partnership, a community work group redirected an obesity prevention program to evolve as a sustainable wellness initiative designed to appeal to diverse groups of women residing in low-income communities. The final model, SHE Tribe, is a peer facilitated, social network–based intervention that includes five session topics: goal setting, stress reduction, physical activity, dietary choices, and social support. Each peer facilitator is provided with a discussion guide and encouraged to tailor activities that fit best with the interests of her Tribe. Rather than being presented as a curriculum, participants are encouraged to seek valid sources of health information, reflect on their own needs and interests, and set goals based on their unique circumstances and motivations. In an early pilot test of this intervention, participants made significant progress in four of five key domains (physical activity, diet, mental health, and general health promotion behaviors). The final domain, social support, increased slightly but was nonsignificant (Chhetri, Anguiano, & Spence-Almaguer, 2018). Our next steps have included a refinement of the intervention based on early feedback and results, inclusion of new community partners, and the implementation of a larger scale clinical trial.

These processes demonstrate unique ways of working with partners in a participatory way to develop a health program. Partnerships can be difficult to manage and sustain, but by using some key strategies it is possible to build trust and collaborate together to address the health needs of communities. Despite experiencing multiple leadership changes, the use of CBPR strategies remained a priority of the university through support by the National Institutes of Minority Health and Health Disparities. These projects highlight the importance of sustaining the spirit of community engagement and making the best use of the knowledge and skills of individuals who are partnering to promote community health.

REFERENCE

- Barry VW, Baruth M, Beets MW, Durstine JL, Liu J, & Blair SN (2014). Fitness vs. fatness on all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 56(4), 382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, & Bowman BA (2014). Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: Elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet, 384(9937), 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AB, Israel BA, & Allen AJ (2005). Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships In Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.), Methods in community-based participatory research for health (pp. 69–94). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Leading causes of death (LCOD) by race/ethnicity, all females—United States, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2014/race-ethnicity/index.htm

- Chhetri S, Anguiano K, & Spence-Almaguer E. (2018, May). Utilizing a social network based peer-led model and improving women’s health. Poster session presented at the Institute for Healthcare Advancement Annual Health Literacy conference, Irvine, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgen L, & Spence-Almaguer E. (2017). Beyond body mass index: Are weight-loss programs the best way to improve the health of African American women? Preventing Chronic Disease, 14, 160573. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, & Ogden CL (2016). Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. Journal of the American Medical Association, 315, 2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, & Kreuter MW (2005). Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, & Guzman JR (2003). Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles In Minkler M. & Wallterstein N. (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health (pp. 53–76). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, … Seifer SD (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Quarterly, 90, 311–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman H, Dodgen L, Mamun A, Slater JL, King G, Slater D, … DeHaven M. (2017). Community-based participatory research to design a faith-enhanced diabetes prevention program: The better me within randomized trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 62, 77–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas CM, Dhana K, Schoufour JD, Ikram MA, Kavousi M, & Franco OH (2017). Impact of physical activity on the association of overweight and obesity with cardiovascular disease: The Rotterdam study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 24, 934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S. (2008). Ethnic minorities and weight control research priorities: Where are we now and where do we need to be? Preventive Medicine, 47, 583–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, Milani RV, & Blair SN (2014). Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: Implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63, 1345–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, … Schulz A. (2018). Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(1), 55–74. doi: 10.1177/1558689816633309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley PA, Artero EG, Sui X, Lee DC, Church TS, Lavie CJ, … Blair SN (2012). The obesity paradox, cardiorespiratory fitness, and coronary heart disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87, 443–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, & Wallerstein N. (Eds.). (2008). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Harris A, Horner-Ibler B, Harris KS, & Burns E. (2016). Hearing the community: Evolution of a nutrition and physical activity program for African American women to improve weight. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27, 560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberg J, Parry D, Pluye P, Macridis S, Herbert CP, & Macaulay AC (2015). Successful strategies to engage research partners for translating evidence into action in community health: A critical review. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jeph/2015/191856/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker MT, Lewis DW Jr., Payne Foster P, Lucky F, Yerby LG, Hites L, … Higginbotham JC (2016). Community-based participatory research–speed dating: An innovative model for fostering collaborations between community leaders and academic researchers. Health Promotion Practice, 17, 775–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. (2016a). Diabetes and African Americans. Retrieved from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. (2016b). Diabetes and Hispanic Americans. Retrieved from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=63

- Wallerstein NB, & Duran B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Minkler M, & Foley K. (2005). Developing and maintaining partnerships with communities In Israel B, Eng E, & Schulz A. (Eds.), Methods in community-based participatory research for health (pp. 31–51). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins N. (2011). Popular education for health promotion and community empowerment: A review of the literature. Health Promotion International, 27, 356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]