Abstract

Genomic instability resulting from defective DNA damage responses or repair causes several abnormalities, including progressive cerebellar ataxia, for which the molecular mechanisms are not well understood. Here, we report a new murine model of cerebellar ataxia resulting from concomitant inactivation of POLB and ATM. POLB is one of key enzymes for the repair of damaged or chemically modified bases, including methylated cytosine, but selective inactivation of Polb during neurogenesis affects only a subpopulation of cortical interneurons despite the accumulation of DNA damage throughout the brain. However, dual inactivation of Polb and Atm resulted in ataxia without significant neuropathological defects in the cerebellum. ATM is a protein kinase that responds to DNA strand breaks, and mutations in ATM are responsible for Ataxia Telangiectasia, which is characterized by progressive cerebellar ataxia. In the cerebella of mice deficient for both Polb and Atm, the most downregulated gene was Itpr1, likely because of misregulated DNA methylation cycle. ITPR1 is known to mediate calcium homeostasis, and ITPR1 mutations result in genetic diseases with cerebellar ataxia. Our data suggest that dysregulation of ITPR1 in the cerebellum could be one of contributing factors to progressive ataxia observed in human genomic instability syndromes.

INTRODUCTION

A fine balance between DNA damage and repair is critical for proper nervous system development and function (1,2). Multiple defense mechanisms are activated to repair damaged DNA or remove the impaired neural cells bearing DNA damage (3). Defects in these defense mechanisms can disrupt brain development and function, leading to human genetic disorders with neurological phenotypes, such as Ataxia Telangiectasia (A-T; caused by mutations in the gene encoding Ataxia telangiectasia mutated, ATM, mutations), Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy 1 (SCAN1; Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, TDP1, mutations), Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia (AOA1; Aprataxin, APTX, mutations) and Ataxia oculomotor apraxia 4 (AOA4; Polynucleotide kinase phosphatase, PNKP, mutations, which is also responsible for Microcephaly, seizures and developmental delay, MCSZ) (1,2,4,5). A common neurological feature of these genetic disorders is progressive cerebellar ataxia, although these repair proteins are involved in different mechanisms of DNA damage repair. ATM is a protein kinase activated immediately upon DNA strand breaks to regulate DNA damage responses, including cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, whereas TDP1, APTX and PNKP are key enzymes that process broken DNA strand ends for proper ligation (1,2,4,6). Despite the association between cerebellar ataxia and defective DNA damage repair, the detailed molecular mechanisms, as well as the progression of ataxia in particular, are not fully understood due to the limited availability of human tissues from the early stage of cerebellar ataxia.

Previously, X-ray repair cross complementing 1 (Xrcc1) inactivation during neurodevelopment in the mouse was studied to understand the connection between defective DNA single-strand break (SSB) repair and neural abnormalities (7). DNA damage accumulates throughout the brains of Xrcc1 conditional knockout animals, yet restricted neural abnormalities such as a selective p53-dependent loss of cerebellar interneurons and sporadic seizures likely due to hippocampal defects were observed (7). XRCC1 is a scaffold protein that binds to multiple DNA SSB repair and Base Excision Repair (BER) factors, including Apurinic/apyrimidinic [AP] endonuclease 1 (APEX1), TDP1, APTX DNA ligase III (LIG3), Poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP1) and DNA polymerase β (POLB), and brings these binding proteins to the sites of DNA damage to facilitate precise damage repair (6,8,9). As XRCC1 involvement in DNA damage repair is reflected by the function of these binding factors, one or a combination of binding partners may be responsible for neurological abnormalities observed in the Xrcc1 conditional knockout animal. However, the neurological phenotypes, particularly cerebellar defects, resulting from Xrcc1 inactivation were not fully replicated by inactivation of these XRCC1 binding proteins, such as Aptx, Lig3, Tdp1, Apex1 and Pnkp, in the nervous system (10–15). Interestingly, Parp1 inactivation, which by itself does not alter the cerebellar interneuron population, rescued the loss of cerebellar interneurons in Xrcc1 conditional knockout animals (9,16).

Here, we examined whether Polb inactivation during neurodevelopment is related to the XRCC1-dependent neurological phenotypes. POLB performs two enzymatic activities: it adds one nucleotide to the 3′ end of DNA strands as a DNA polymerase, and it removes 5′ sugar phosphates as a deoxyribose phosphate lyase during the repair of AP sites in BER that corrects DNA base damage (17). BER also could regulate gene expression by participating in the cycle of DNA demethylation (18). We demonstrate that conditional inactivation of Polb in the nervous system does not result in substantial neural abnormalities. However, double knockout animals deficient for Polb and Atm displayed severe ataxia in the absence of significant neuropathology, but with reduced cerebellar expression of Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1 (Itpr1), a gene associated with cerebellar ataxia in humans (19,20), which likely resulted from misregulated cytosine methylation. These findings suggest that a reduction of Itpr1 could be one of contributors to the progression of cerebellar ataxia caused by genomic instability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Animals harboring a floxed DNA polymerase β gene (Polb) (B6.129P2-Polbtm1Rsky/J, stock no: 009154) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). As germline deletion was embryonic lethal (21), exon 1 of Polb flanked by LoxP sites was targeted by crossed with the Nestin-Cre line [B6.Cg-Tg(Nes-cre)1Kln/J, stock no: 003771] to restrict Polb inactivation in the nervous system during development, yielding Polb LoxP/LoxP; Nestin-Cre (indicated as Polb cKO or Polb Nes-Cre, hereafter) animals. As no phenotypic difference was observed between male and female mice, both sexes were used for analyses. Xrcc1 conditional knockout (Xrcc1Nes-Cre) and Atm knockout animals were described before (7,13). All irradiated (Cs137) tissue samples were prepared at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis, TN, USA). The presence of a vaginal plug indicated as Embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5), and the day of birth was designated as postnatal day 0 (P0). All animals were housed in the Laboratory Animal Research Center of Ajou University Medical Center and maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures for animal use were approved by the committee.

Quantitative realtime PCR

To assess the efficacy of gene deletion by Cre recombinase, the genomic DNA from the several brain areas of the adult mice were extracted. The exon 1 (targeted) and exon 14 (control) of the Polβ gene were measured by realtime polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method using a Qiagen system (Roto-Gene Q PCR machine and SYBR Green PCR kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The efficacy of gene deletion was calculated as a ratio between exon 1 and exon 14 measurements.

Western blot analysis

Tissue samples from two to three animals for each genotype were collected and snap frozen at various time points. Western blotting was performed as described previously with a slight modification (7,13). The equal loading of samples was confirmed by antibodies against actin (1:2500, mouse; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) or tubulin (1:40 000, mouse; a gift from Dr Sang Gyu Park) or by Ponceau-staining. The list of antibodies used for western blot analyses is presented in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Histopathological analysis

Histopathological analyses were performed as described previously (7,13). Two to four embryos or brains for each genotype were collected and fixed at various time points. Nissl staining was performed via a routine procedure. Immunopositive signals were visualized using the VIP substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), or with fluorophore (FITC- or Cy3-) conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Immunoreactive signals were enhanced with citric acid-based antigen retrieval as needed. For apoptosis analysis, a TUNEL assay using Apoptag (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) was applied. The list of antibodies used for histopathological analyses is presented in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Genomics analysis

Four analyses were performed to ascertain the genomic event underlying the observed ataxia in mutant mouse models. First, the RNAseq was performed with an assistance provided by DNA Link (Seoul, Korea). The reads were mapped with the Tophat aligner using the UCSC mouse mm10 genome (Genome Reference Consortium GRCm38), and the Cuffdiff program was used to screen for differentially expressed genes. Further functional annotation analysis was carried out with the DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (https://david.ncifcrf.gov). RNAseq data were also analyzed with another genomic analysis platform, StrandNGS (Strands Life Sciences, Bengaluru, India). All RNAseq data were normalized and filtered by expression levels. Genes that showed at least a 2-fold difference (5-fold difference for the further screening) in multiple comparisons after statistical evaluation, including analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni false-discovery rate correction, were selected and analyzed further by the pathway algorithm provided by StrandNGS using 627 publicly available signaling pathways. Second, DNA methylation was interrogated using mouse CpG Island Microarray (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) covering 15,342 CpG Islands (97,652 CpG probes) and the UCSC mm9 genome (NCBI Build 37) with a support from Genomictree (Daejeon, Korea). Fluorescence was scanned and the intensities calculated for data analysis, including per spot and per chip Lowess normalization, and fold differences were calculated with GeneSpring software and the Workbench program (Agilent Genomics). We further analyzed the lists of significant genes from the CpG Island Microarray analysis using publicly available web-based application, Venn diagram analysis (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Third, DNA methylation on the promoter region of Itpr1 was assessed via DNA pyrosequencing with a support from Genomictree. CpG Island prediction was carried out using the web-based application, MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org/cgi-bin/methprimer/methprimer.cgi) (22). The methylation percentage was calculated by the average degree of methylation at 1–7 CpG sites formulated in pyrosequencing. Fourth, the DNA sites with 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) modification and their frequencies at a single-base resolution were further analyzed via the Reduced Representation Hydroxymethylation Profiling (RRHP) (23). The DNA library preparation and sequencing were performed by Zymo Research (Irvine, CA, USA). The RRHP reads and locations of 5hmC throughout the whole genome, particularly at the Itpr1 gene, were visualized using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway) and Integrative Genomics Viewer (http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/). The lists of genes from genomic analyses were further examined with gene ontology enrichment analysis (http://geneontology.org, http://pantherdb.org, and https://tools.dice-database.org/GOnet/—which provides gene nodes colored by expression in various cell types/tissues including the cerebellum: Bgee DB [http://bgee.org] for the mouse).

ELISA and chemiluminescent assay

To measure percent 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5hmC DNA, denatured single-stranded DNA samples from the cerebral cortices and cerebella were either plated directly onto an ELISA plate for 5mC measurement or onto a 5hmC antibody-coated ELISA plate for 5hmC measurement according to the manufacturer's manual (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), and then the positive signals were measured at 405 nm. Each sample was prepared in triplicates, and these analyses were repeated twice. Percent 5mC and 5hmC were calculated by the equation provided in the manufacturer's manual.

The enzyme activities of DNMT1 and TET1 in the protein lysates from the cerebral cortices and cerebella were measured using chemiluminescent assay kits from BPS Bioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). The chemiluminescence signals were measured according to the manufacturer's protocol and then further normalized by protein quantity. Each sample was prepared in triplicates, and these analyses were repeated two times.

Image and statistical analyses

Microscopy images and other digital images were composited using Photoshop software (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed in ImageJ (NIH, USA) with the measuring and densitometry function. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

The complete description of materials and methods is presented in the Supplementary Data; Supplementary Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

Polb inactivation during neurogenesis does not affect overall brain development

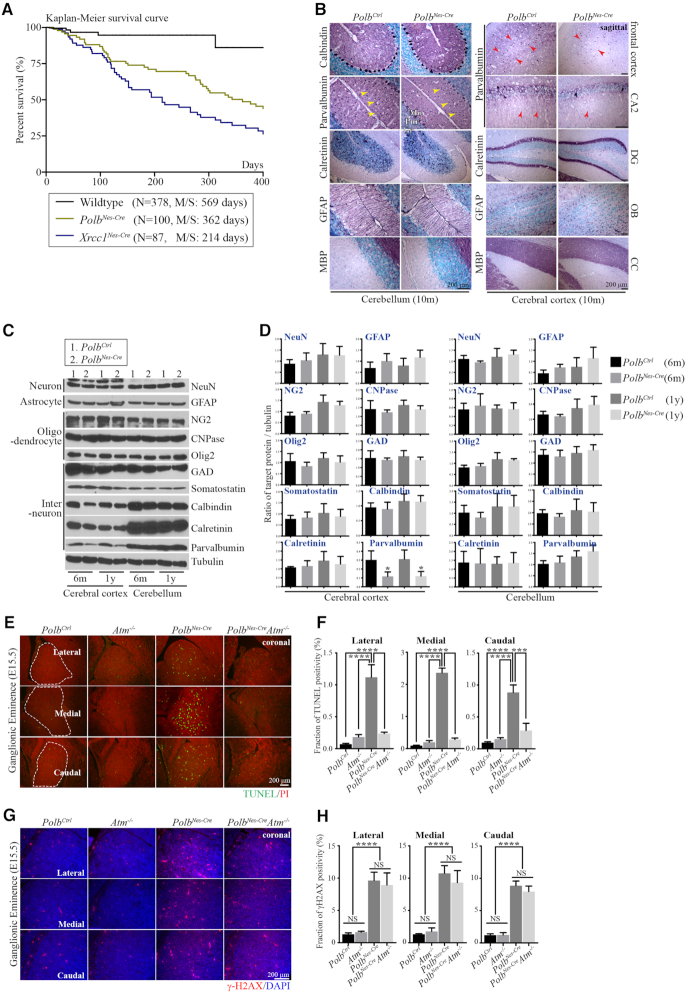

Germline deletion of Polb in mice is embryonic lethal and induces neural apoptosis, particularly in the ganglionic eminence (GE) of the embryonic brain (21,24). To circumvent embryonic lethality, Polb was selectively inactivated during neurogenesis in a Nestin-Cre line. The PolbNes-Cre animals were born at an expected Mendelian ratio and had a shorter life span without any noticeable neurological or behavioral abnormities (Figure 1A). The Polb gene and POLB protein were absent from brain tissues of adult PolbNes-Cre mice, whereas expression of XRCC1 and APEX1, which are related DNA damage repair proteins (9), was not affected in these mutant brains (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). Furthermore, neuron, interneuron and glial cell (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes) populations in brains of adult PolbNes-Cre animals were comparable to those in control animals (Figure 1B–D). Importantly, the cerebellar defects found in the Xrcc1Nes-Creanimals, such as cerebellar interneuron loss (7), were not observed in the PolbNes-Cre animals. Particularly parvalbumin-positive (Par+) interneurons were intact in the molecular layer of the PolbNes-Cre cerebellum, and the corresponding expression levels of cerebellar parvalbumin did not differ from those of the controls (Figures 1B–D and 3), suggesting that Polb inactivation did not contribute to the neurological defects, especially cerebellar defects resulting from Xrcc1 deficiency.

Figure 1.

Polb inactivation during neurogenesis does not affect overall brain development. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Polb inactivation in the nervous system (PolbNes-Cre) of the mouse was associated with a shorter life span than in wild-type animals, yet it was longer than that in Xrcc1 conditional (Xrcc1Nes-Cre; Xrcc1 inactivation in the nervous system using a Nestin-Cre line) animals. N indicates the number of animals observed for the analysis. M/S, median survival days. (B) Histopathological analysis of adult (10 months old [10 m]) cerebella and cerebral cortices (sagittal plane). There was no difference between the control (Ctrl) and PolbNes-Cre brains, except for fewer parvalbumin-positive interneurons and axons (red arrow heads) in the PolbNes-Cre cerebral cortex. There was also no sign of cerebellar interneuron loss (yellow arrow heads) in the PolbNes-Cre cerebellum, which is one of the major neural defects found in the Xrcc1 null cerebellum (7). CA2, Cornu ammonis area 2 of the hippocampus; DG, Dentate gyrus of the hippocampus; OB, Olfactory bulb; CC, Corpus Callosum; Mo, Molecular layer in the cerebellum; Pur, Purkinje cell layer in the cerebellum; Gr, Granule cell layer in the cerebellum. (C and D) Western blots (C) and quantification (D) analyses of several neural markers in the cerebral cortices and cerebella of mice at 6 months (6 m) and 1 year (1 y) of age, which show no defects in the PolbNes-Cre animals except for reduced parvalbumin in the PolbNes-Cre cerebral cortices, not in the cerebella. The protein levels of indicated markers were measured using ImageJ (densitometry) and were normalized to those of tubulin (D). N = 3. All bars indicate mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05. Neuronal marker, (NeuN); Astrocyte marker, (GFAP); Oligodendrocyte marker, (NG2, CNPase, Olig2); Interneuron/specialized neuronal marker, (GAD, Somatostatin, Calbindin, Calretinin, Parvalbumin). (E and F) Apoptosis detected by TUNEL (Green staining, E) and corresponding quantification (F) in the lateral, medial and caudal Ganglionic Eminence at E15.5 (coronal plane). Neural apoptosis was found only in the PolbNes-Cre Ganglionic Eminence, which disappeared in an Atm−/− background. TUNEL positivity was measured using ImageJ in the demarcated areas (white dotted lines) from multiple embryonic sections (F). Counter staining: Propidium Iodide (PI). N = 4 (Ctrl), N = 3 each (each genetic backgrounds). All bars indicate mean ± SEM; ****, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.005. (G and H) DNA damage visualized as γ-H2AX foci formation (red punctate staining, (G) and corresponding quantification (H) in the lateral, medial and caudal Ganglionic Eminence at E15.5 (coronal plane). The amounts of DNA damage are similar in the PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− Ganglionic Eminence, and were negligible in control (Ctrl) and Atm−/− embryos. γ-H2AX foci were measured using ImageJ in several 150-μm2 areas from multiple embryonic sections (H). Counter staining: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). N = 4 (Ctrl), 3 (Atm−/−, PolbNes-Cre) and 2 (PolbNes-CreAtm−/−). All bars indicate mean ± SEM; ****, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

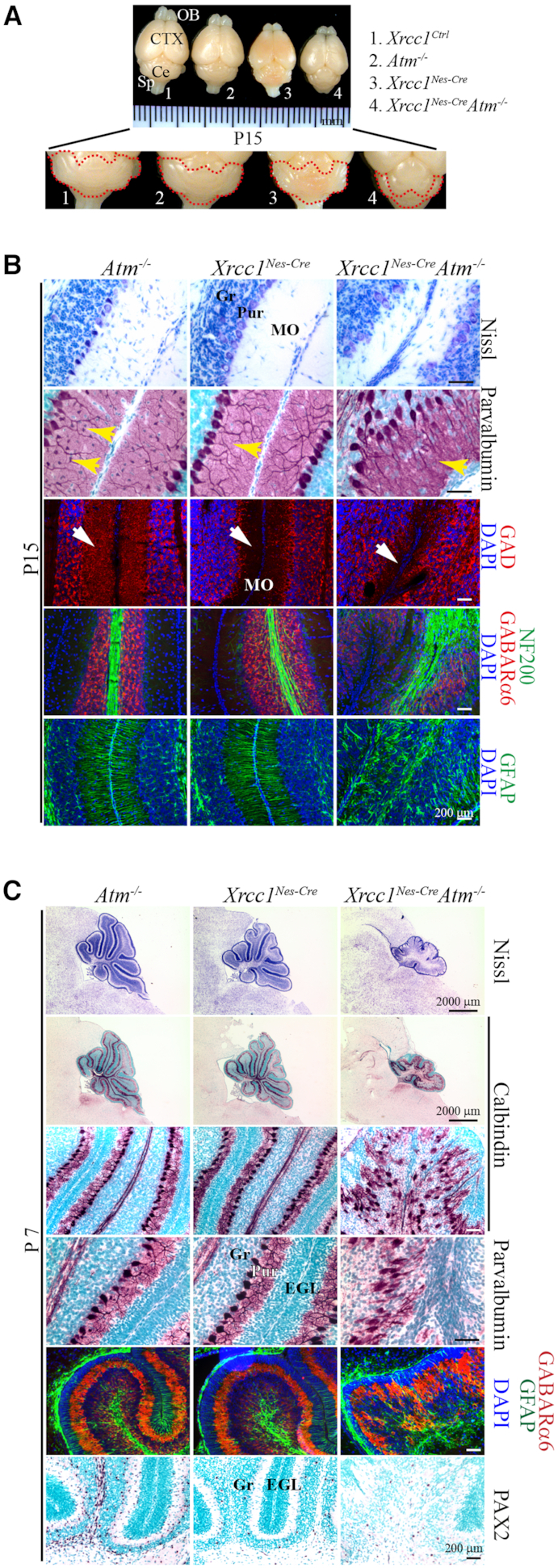

Figure 3.

Atm inactivation in the Xrcc1Nes-Cre brain results in abnormal cerebellum. (A) Gross view of the brains of mice from different genetic backgrounds (control, Atm−/−, Xrcc1Nes-Cre, Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/−) at P15. The red lines demarcate the cerebellum. The size of the cerebellum was reduced in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/- mice. OB, Olfactory bulb; CTX; Cerebral cortex; Ce, Cerebellum; Sp, Spinal cord. (B) Histopathological analysis of the cerebellum at P15. GAD (glutamate decarboxylase) immunoreactivity is for the GABAergic neuron network, and NF200 (neurofilament 200) immunoreactivity is for neurons. The Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella showed signs of interneuron loss (yellow arrows, parvalbumin positive interneurons; white arrows, GABAergic neurons) in the molecular layer, similarly to the Xrcc1Nes-Cre cerebella, suggesting that interneuron loss in Xrcc1 deficiency is ATM independent and p53 dependent (7). Gr, Granule cell layer; Pur, Purkinje cell layer; MO, Molecular layer. (C) Histopathological analysis of the cerebella of Atm−/−, Xrcc1Nes-Cre, and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals at P7 (sagittal plane), when the Purkinje cells are in a single-cell layer and foliation of all cerebellar lobules are noticeable. Nissl staining shows the overall structure of the cerebellar vermis. Calbindin immunoreactivity for the Purkinje cell layer, parvalbumin immunoreactivity for interneurons in the molecular layer and Purkinje cells, GABARa6 immunoreactivity for the granule cell layer, GFAP immunoreactivity for the Bergmann glia network, and PAX2 immunoreactivity for interneurons in the cerebellum are shown. The Atm null cerebellum was normal for the formation of Purkinje and granule cell layers and for the interneuron population. The Xrcc1Nes-Cre cerebellum also showed normal development except for fewer interneurons (PAX2-positive cells) as described before (7). However, the Purkinje cell layer was not properly organized in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum, which was smaller and less foliated. Also, PAX2-positive interneurons were not rescued in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum. Gr, Granule cell layer; EGL, External germinal layer; Pur, Purkinje cell layer.

By contrast, the cerebral cortices of PolbNes-Cre animals exhibited a selective reduction of Par+ interneurons (Figure 1B–D). As Par+ cortical interneurons originate from the GE (25), we examined PolbNes-Cre animals during embryogenesis. For this analysis, the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− embryos were also included in order to investigate ATM involvement in this neurological context. Proliferation and maturation in the brains of Atm−/−, PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− embryos were similar to those in control embryos (Supplementary Figure S1C). Signs of neural apoptosis were found mainly in the GE of the PolbNes-Cre embryonic brain, similarly to previous reports (24,26), which was disappeared in an Atm-null background (Figure 1E and F; Supplementary Figure S1D). However the amounts of DNA damage as measured by the formation of γ-H2AX foci in all three GE subdivisions were similar between the PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− embryos, and the sign of DNA damage was negligible in the control and Atm−/− embryonic GEs (Figure 1G and H; Supplementary Figure S2A). These data suggest that Polb inactivation results in DNA damage, and that ATM is involved in neural apoptosis triggered by DNA damage during neurogenesis, as previously demonstrated (27). It is likely that apoptosis confined to the GE resulted in reduced Par+ neurons in the PolbNes-Cre cerebral cortex. This loss of cortical Par+ interneurons and apoptosis in the GE was not apparent in the Xrcc1Nes-Cre brain (7), implicating a complex involvement of DNA damage repair factors in brain development and function.

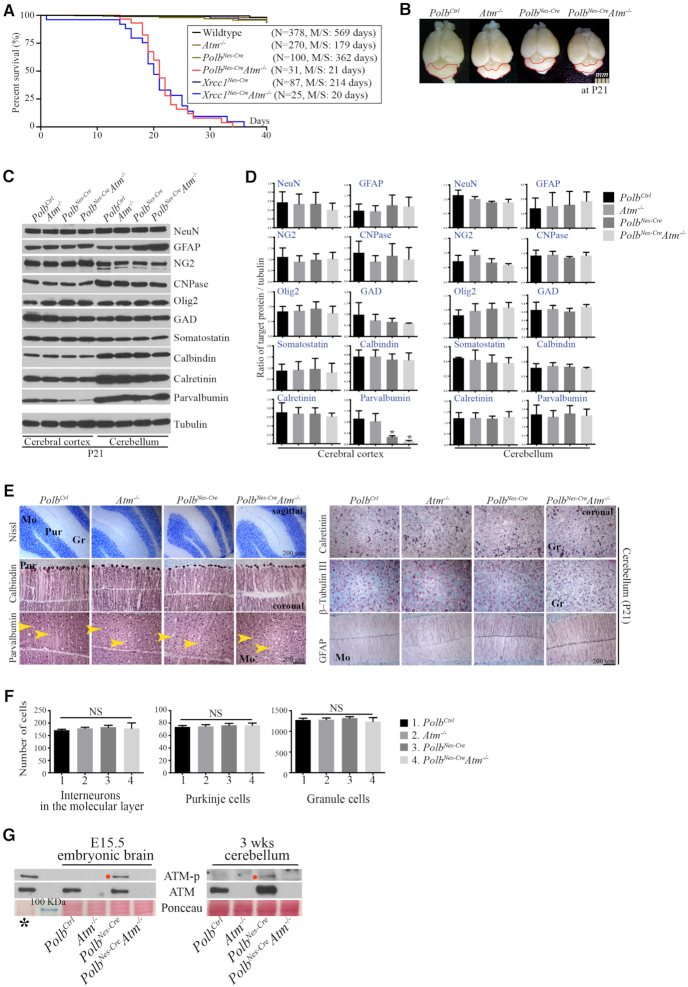

Polb deficiency causes chronic DNA damage in the brain, and double inactivation of Polb and Atm results in severe ataxia

Unexpectedly, double inactivation of Polb and Atm during neurogenesis resulted in severe ataxia which became apparent after 2 weeks of age. All Polb and Atm double knockout animals could not control hind limb movements and hold still, and these double knockout animals did not survive beyond ∼3–4 weeks, likely due to inanition (Figure 2A; Supplementary Movie clip). This neurological phenotype was similar to that observed in the Xrcc1 and Atm double knockout animals (13). However, a thorough examination of the Polb and Atm double knockout brains did not reveal any neuropathological abnormalities, particularly in the cerebellum. The PolbNes-CreAtm−/− brains were grossly normal in size, with no alterations of neural population except for a reduction in cortical Par+ neurons comparable to that observed in the cerebral cortices of PolbNes-Cre animals (Figure 2B–D). Although Atm inactivation suppressed neural apoptosis in the Polb conditional knockout GE during embryogenesis (Figure 1E and F), this was not sufficient enough to recover the maturation process of cortical Par+ neurons, which occur during postnatal development (25). Alternatively, interneuron progenitor cells in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− GE, which would express parvalbumin in the mature cerebral cortex, could not restore their proliferative potential, as a similar observation reported previously (28).

Figure 2.

Polb and Atm double inactivation results in severe ataxia without significant neuropathological defects in the cerebellum. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curve. The PolbNes-CreAtm−/− animals did not live beyond 3–4 weeks of age, similar to the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals. Polb/Atm and Xrcc1/Atm double conditional knockout animals were both severely ataxic. N indicates the number of animals observed for the analysis. M/S, median survival days. (B) Gross view of the brains in different genetic backgrounds at postnatal day (P) 21. The red lines demarcate the cerebellum, which shows no difference in size. (C and D) Western blot analysis of several neural markers in the cerebral cortices and cerebella at P21 (C) and quantification analyses of neural markers (D). No abnormal expression was found in either PolbNes-Cre or PolbNes-CreAtm−/− brains except for cortical parvalbumin (C). Atm deficiency was not sufficient to rescue reduced parvalbumin expression in the PolbNes-Cre cerebral cortex. The protein levels of indicated neural markers were measured using ImageJ (densitometry) and were normalized to those of tubulin (F). N = 3. All bars indicate mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05. (E and F) Histopathological analysis of the cerebellum at P21 (E) (sagittal and coronal planes). In the cerebella of PolbNes-CreAtm−/− animals that showed severe ataxia, the Purkinje cell layer detected by calbindin immunopositivity (quantified in F) is normally organized, and parvalbumin-(yellow arrowheads, quantified in D) and calretinin-positive interneurons are intact. Increased GFAP immunoreactivity (Bergmann glia) in the PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella is visible, which is a common feature among animal models of genomic instability. Interneurons in the molecular layer, Purkinje cells and granule cells were counted (D) in numerous 0.27-mm2 areas (0.07 mm2 for granule cells; Nissl staining [C]) of the matched cerebellar parts, which show no difference. Counter staining: methyl Green. N = 4 (Ctrl), N = 3 each (other genetic backgrounds). All bars indicate mean ± SEM; NS, not significant; Mo, Molecular layer; Gr, Granule cell layer; Pur, Purkinje cell layer. (G) ATM phosphorylation (ATM-p) was observed only in the Polb inactivated embryonic brain at E15.5 and in the Polb null cerebellum at 3 weeks (wks) of age. The red dots indicate mouse ATM phosphorylated at serine 1987. * ionizing radiated (10Gy) murine thymus as a positive control. The blue line indicates a 100-kDa molecular weight marker.

To determine the cause of ataxia, we focused on the cerebella of PolbNes-CreAtm−/− animals. Continually induced DNA damage, visualized as the formation of nuclear γ-H2AX foci, was present at similar distributions and amounts in both Polb conditional knockout and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− brains during neurogenesis and in the brain (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). This endogenously induced DNA damage likely triggered ATM phosphorylation, particularly in the cerebellum (Figure 2G). Nevertheless, signs of apoptosis were not observed in the developing cerebella of the PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− embryos (Supplementary Figure S1D). There were comparable amounts of parvalbumin detected in the cerebella of mice from all four different genetic backgrounds (Figure 2C and D); these originate from the ventricular zone of embryonic cerebellum (Supplementary Figure S1C) (29). Moreover, there were no signs of neuropathology related to ataxia in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, with similar cerebellar structures and neuronal populations, including Purkinje cells, granule cells, and cerebellar interneurons, as in the Atm−/− and PolbNes-Cre cerebella (Figure 2E and F; Supplementary Figure S2C). In a stark contrast to the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella were smaller and less foliated than age-matched Atm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-Cre cerebella. Furthermore, the Purkinje cell layer was entirely disarrayed in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella (Figure 3A and B), resulting in severe ataxia (Supplementary Movie clip) (13). In addition, Par+ interneurons, PAX2 positive interneurons and glutamic acid decarboxylase positive GABAergic neurons were not recovered in the Atm null background (Figure 3B and C), indicating that cerebellar interneuron loss resulting from Xrcc1 inactivation was p53 dependent but Atm independent (7).

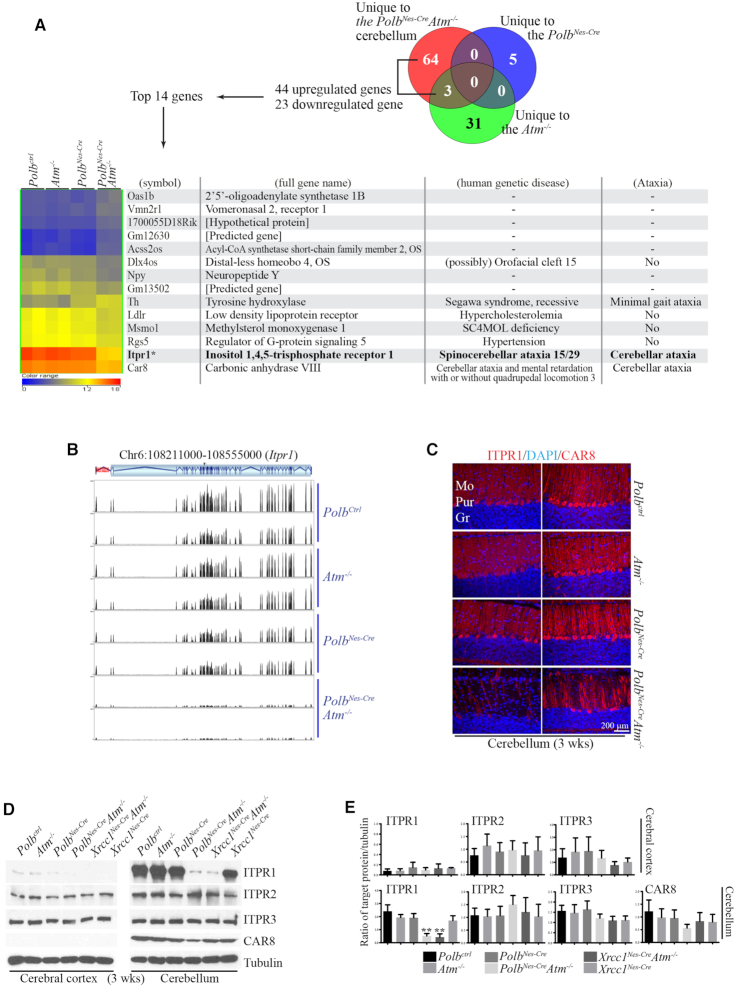

Itpr1 is the most differentially expressed gene in Polb/Atm and Xrcc1/Atm double knockout cerebella

As the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella appeared structurally normal, we next performed RNA sequencing (RNAseq) to identify genetic modifications contributing to the ataxia. Cerebellar samples from control, Atm−/−, PolbNes-Cre and PolbNes-CreAtm−/− animals had similar genic regions overall (Supplementary Figure S3A), and robust data-mining analyses revealed small groups of genes that were differentially expressed in each of the genetic backgrounds studied (five genes in the PolbNes-Cre, 31 in Atm−/−, 64 in PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and three in both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Atm−/−) (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S3B, their hierarchical analyses: Supplementary Figure S3C-F). The ontology and signaling analyses, using publicly and commercially available platforms, of these differentially expressed genes did not reveal any outcomes significantly related to progressive cerebellar ataxia in human genetic diseases. Next, a stringent and higher fold-difference filtering was applied to the 67 genes that were differentially expressed in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum, and 14 genes were retained (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S3E and F). Among these genes, only Itpr1 and carbonic anhydrase 8 (Car8) are directly related to cerebellar ataxia in humans (19,20,30–32). Notably, Itpr1 was the highest expressed gene in the control, Atm−/− and PolbNes-Cre cerebella. Also this gene was the most downregulated in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Itpr1 expression is reduced the most in the cerebella of PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals that show severe ataxia. (A) Hierarchical cluster analysis of cerebellar RNAseq data. The Venn diagram indicates the numbers of genes significantly and uniquely up- or downregulated in each mutant cerebellum. Hierarchical clustering of the top 14 genes among 44 upregulated and 23 downregulated genes unique to the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum is shown. The color scale of the normalized expression values ranges from 0 (blue) to 12 (yellow) to 18 (red). The gene list also includes related human genetic disease information obtained from the public database (http://omim.org and http://rarediseases.info.nih.gov). The most differentially expressed gene in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum was Itpr1, compared with that in the control, Atm−/− and PolbNes-Cre cerebella at 3 weeks of age. ITPR1 mutations or deletions are responsible for Spinocerebellar ataxia 15/29 or Gillespie syndrome. (B) RNAseq profiling of Itpr1 in the mouse cerebellum at 3 weeks of age; the Itpr1 gene is located on chromosome 6 (Chr6) 108,213,083–108,551,116. The vertical lines in the gene structure indicate exons, and the zigzag lines indicate introns. The black peaks matched with exon locations represent the normalized RNAseq reading (y-axis scale, 0–1900), and these peaks are negligible in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum, indicating the reduction of Itpr1 expression in this particular genetic background. (C) Immunostainings of ITPR1 and CAR8, which are highly and exclusively expressed in the Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum (coronal plane). ITPR1 immunopositivity is almost absent in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum. Also reduced CAR8 staining is visible in the double knockout cerebellum. Mo, Molecular layer; Pur, Purkinje cell layer; Gr, Granule cell layer. (D and E) Western blots (D) and quantification (E) analyses for ITPR1, ITPR2, ITPR3 and CAR8 in the cerebral cortices and cerebella at 3 weeks of age. A dramatic reduction of ITPR1 is evident only in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella. Both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals displayed severe ataxia. The expressions of ITPR1 and CAR8 in the cerebral cortex were barely detected. The protein levels of indicated proteins were measured using ImageJ (densitometry) and were normalized to those of tubulin (E). N = 3. All bars indicate mean ± SEM; **, P < 0.01.

ITPR1 immunoreactivity, found exclusively in the Purkinje cell bodies aligned as a single cell layer and their axons in the molecular layer, was drastically diminished in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, even though the Purkinje cell layer was intact in these animals (Figures 2E and 4C). This reduction of ITPR1 protein was confirmed by western blotting, which also included the Xrcc1Nes-Cre and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− brains to evaluate any difference between Polb and Xrcc1 deficiency in the Atm null nervous system, since both double knockout animal models displayed severe ataxia (Figure 4D and E). Remarkably, the reduction of ITPR1 was evident in both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, but not in the cerebral cortices of these double knockout animals (Figure 4D and E). These data revealed that the ITPR1 reduction was restricted to the cerebellum, particularly to Purkinje cells, as no loss was detected in the double knockout cerebral cortex. Reduction of Itpr1 expression likely occurs in a progressive manner, since no reduction was observed in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella at the early stage of postnatal development (Figure 4D and E; Supplementary Figure S4A and B). The expression levels of ITPR2 and ITPR3 were similar in the cerebral cortices and cerebella of all analyzed animals, suggesting that there was no compensation by other ITPR family proteins for ITPR1 reduction in the double knockout cerebella (Figure 4D and E; Supplementary Figure S4A and B). In addition, there was a minor reduction of CAR8 detected in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, which is expressed in Purkinje cells and can bind to ITPR1 (Figure 4C–E) (33). Aged PolbNes-Cre and Atm−/− animals did not exhibit reduced cerebellar ITPR1 levels (Supplementary Figure S4C and D), suggesting that the reduction of ITPR1 in the cerebellum is restricted to a certain physiological condition. As ITPR1 mutations have clinical relevance for cerebellar ataxia (Figure 4A) (19,20,34,35), reduced expression of ITPR1 in the cerebellum is likely one of contributing factors toward progressive cerebellar ataxia in human disorders with genomic instability.

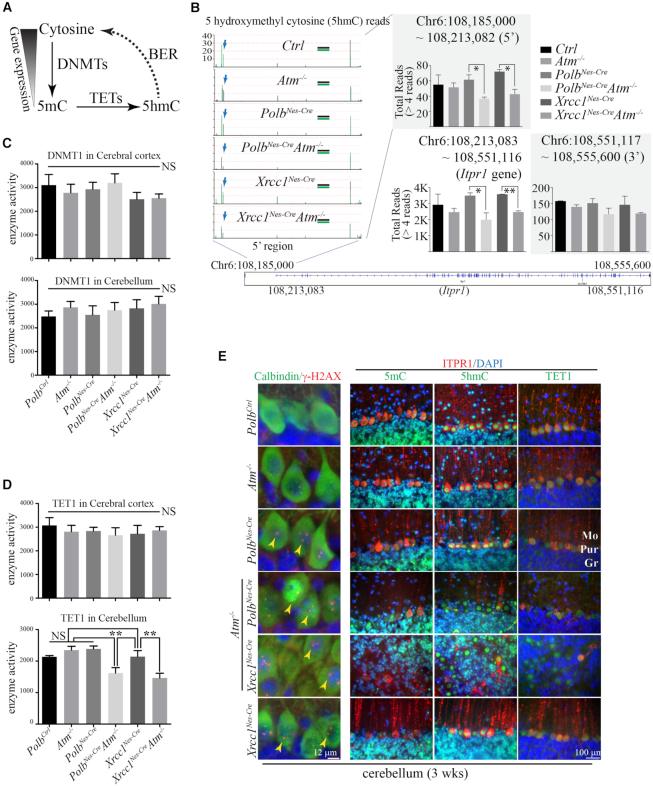

Altered cytosine methylation could result in Itpr1 reduction in the Polb/Atm and Xrcc1/Atm double knockout cerebella

We next examined DNA methylation as a potential mechanism for reduced Itpr1 expression in the double knockout cerebella. Gene expression correlates inversely with 5-methylcytosine (5mC) levels, whose methyl groups are transferred by DNA methyltransferases including DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b. And it positively correlates with levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) which is converted from 5mC by methylcytosine dioxygenase members of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family. Eventually, modified cytosine bases are corrected by demethylation processes in which BER is involved, thereby influencing gene expression (Figure 5A) (18,36). Furthermore, ATM regulates both the activity of TET1 in response to DNA damage in the cerebellum (37) and the stability of DNMT1 (38).

Figure 5.

Epigenetic regulation likely contributes to Itpr1 reduction in the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella. (A) Simplified diagram of DNA methylation cycle. Cytosine in DNA is methylated by DNMTs (DNA methyltransferases) to become 5mC (5-methylcytosine), whose levels are inversely correlated with gene expression. 5mC is oxidized by TETs (Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenases), into 5hmC (5-hydroxymethylcytosine). This chemically modified cytosine is recognized for base excision repair (BER) (POLB and XRCC1 are involved) and then is eventually restored to cytosine. Thus, BER participates in the regulation of gene expression. (B) The repetitive 5hmC reads and locations on the Itpr1 gene on chromosome (Chr) 6 from the reduced representation hydroxymethylation profiling (RRHP) analyses. The total reads of 5hmC (>4 reads) in the 5′ (108,185,000 –108,213,082 [promoter, magnified]), Itpr1 gene (108,213,083–108,551,116) and 3′ (108,551,117–108,555,600) regions were calculated. In the magnified portion, two plots (in black and green) were overlaid for each genetic background, and the vertical lines indicate the locations of 5hmC and the amounts of repetitive reads. The blue arrows indicate one of several 5hmC sites that were reduced in both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella. In the graphs, all bars for total 5hmC reads in the marked regions indicate mean ± SEM; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. (C and D) DNMT1 (C) and TET1 (D) enzyme activities in the cerebral cortices and cerebella of mice from six different genetic backgrounds at 3 weeks of age. Chemiluminescence readings for enzyme activity in triplicates (repeated twice) were normalized by protein quantity. There is less enzyme activity of TET1 detected in both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, than in the other genetic backgrounds. N = 4 each (all genetic backgrounds). All bars indicate mean ± SEM; **, P < 0.01; NS, not significant. (E) Immunohistochemical analyses of 5mC, 5hmC and TET1 with ITPR1 immunoreactivity as well as DNA damage visualized by nuclear γ-H2AX foci in Purkinje cells (calbindin positive) of the cerebellum (sagittal and coronal planes). TET1 is strongly expressed and localized in the nuclei of the Purkinje cells. Similarly strong nuclear 5hmC staining is evident in the Purkinje cells, which showed DNA damage (γ-H2AX foci, yellow arrowheads) only in the Polb and Xrcc1 null cerebellum regardless of the status of Atm, and not in the Ctrl and Atm−/− cerebellum. Nuclear 5mC immunoreactivity was not as robust as that of 5hmC in the Purkinje cells. Reduced ITPR1 immunoreactivity in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum is apparent. Mo, Molecular layer; Pur, Purkinje cell layer; Gr, Granule cell layer.

First, we compared the global status of genes in the mutant cerebella with those in wild-type cerebella to identify hyper- or hypomethylated genes in each genetic background using two-color CpG Island Microarray technology (Agilent). A number of genes were differentially methylated at CpG Islands in the double knockout cerebella, but various data-mining analyses of these genes did not reveal any close correlation to cerebellar ataxia in humans (Supplementary Figures S4E and S5A). As Itpr1 was not present on this particular CpG microarray for the mouse, pyrosequencing was performed to measure the methylation levels of the Itpr1 promotor regions in the cerebral cortices and cerebella of all six genetic strains including both double knockout animals. Due to technical limitations, only two promoter regions of the Itpr1 gene were applicable for pyrosequencing, and the methylation levels were similar among all samples (Supplementary Figure S5B and C).

Reduced Representation Hydroxymethylation Profiling (RRHP) technology (23) was then applied to analyze 5hmC sites and levels at single-base resolution throughout the whole genome from the cerebellar samples of control and knockout animals. The overall coverage of genic 5hmC reads by the RRHP analysis did not differ in all six genetic strains including both double knockout animals (Supplementary Figure S6B). In addition, ELISA measurements of DNA samples from the cerebral cortices and cerebella of all examined animal models showed comparable levels of 5mC and 5hmC, with the exception of a minor reduction of the 5mC level in the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebellum (Supplementary Figure S6A). Nevertheless, the RRHP analysis revealed reduced 5hmC levels at a few genes in both PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella compared with those in the controls (Supplementary Figure S7A). Among these genes, Itpr1 and Calmodulin-binding transcription activator 1 (Camta1) are related to cerebellar ataxia in humans, yet mutations in CAMTA1 cause non-progressive ataxia in humans (39). Apparently, Itpr1 was most specific for the cerebellum among these genes from the RRHP and gene ontology analyses using the Bgee DB (Supplementary Figure S7B). The sites of 5hmCs in the Itpr1 gene region were identical in all the genetic backgrounds studied, and there were no aberrations found in the DNA sequences of the Itpr1 gene, except for few single nucleotide polymorphisms, in all DNA samples (Supplementary Figure S6C and D). However, the repetition of 5hmC reads presented as the height of the bars in the figures, particularly in the promoter region, of the Itpr1 gene was reduced in the cerebella of the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals compared with that in the cerebellar samples from other genetic backgrounds (Figure 5B; Supplementary Figure S6C), suggesting that misregulation of cytosine methylation may be responsible in part for the reduced Itpr1 gene expression.

Next we examined the status of DNA methyltransferases and methylcytosine dioxygenases related to cytosine modification. First, as ATM could interact physically with DNMT1 and regulate its stability (38), we measured the protein levels of DNMT1 as well as DNMT3a and DNMT3b by western blotting. The expression levels of these enzymes in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum did not differ between double knockout and control animals (Supplementary Figure S7C–F). Also the brains from aged PolbNes-Cre and Atm−/− animals did not show any significant change and difference in the expression of these methyltransferases compared with controls (Supplementary Figure S7G and H). We further measured the enzyme activity of DNMT1 in cortical and cerebellar samples, which did not differ in all examined animal models (Figure 5C). By contrast, the enzyme activity of TET1 was reduced in cerebella, but not cerebral cortices, of PolbNes-CreAtm−/− and Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− animals, likely reflecting the reduced 5hmC levels for Itpr1 in the double knockout cerebella (Figure 5D). Previously, it has been demonstrated that the enzyme activation of TET1 is under the control of ATM upon DNA damage, thereby affecting 5hmC levels (37). TET1 and 5hmC immunoreactivity was found in the nuclei of Purkinje cells. And DNA damage as visualized by γ-H2AX foci was observed only in animals deficient in DNA damage repair regardless of the presence of Atm (Figure 5E), suggesting that PolbNes-Cre and Xrcc1Nes-Cre Purkinje cells are chronically exposed to genotoxic stress, which likely acts as one of contributing factors to cerebellar ataxia in an Atm deficient condition. Similarly to the PolbNes-CreAtm−/− cerebella, ITPR1 immunopositivity was rarely spotted in disarrayed Purkinje cells of the Xrcc1Nes-CreAtm−/− cerebella (Figure 5E).

DISCUSSION

As demonstrated in several animal models (7,11,27), endogenous DNA damage occurs during brain development, and defective responses to this kind of damage result in various genetic disorders associated with neurological phenotypes, including progressive cerebellar ataxia (1,2,4). In patients with A-T, it has been known that neurodegeneration of Purkinje and granule cells in the cerebellum is the main cause for ataxia (1,40), yet the molecular details of this pathological process are not fully understood. A number of animal models have been generated and studied to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms of A-T etiology (41,42). Even though Atm mutant animal models recapitulate extra-neural phenotypes of A-T, such as immunodeficiency, increased risk to develop cancer, radiosensitivity, but none of A-T animal models display a genuine cerebellar ataxic phenotype in a progressive manner related to A-T syndrome (41,42). Indeed, the Atm knockout animal model used for the current study did not show any sign of cerebellar ataxia and other neurological phenotypes, yet Atm null neurons are resistant to induced DNA damage (27,43,44). Perhaps, an additional genetic impetus may be required to induce ataxia in this Atm null animal model. For example, Xrcc1 deficiency in the nervous system of the Atm null animal model induces severe ataxia resulting from developmental defects and malformation of the cerebellum (13). Nevertheless, this model does not accurately reflect progressive cerebellar ataxia manifested in A-T patients.

Here, we introduce a new animal model with double inactivation of Polb and Atm in the nervous system that exhibits severe ataxia without developmental and anatomical defects in the cerebellum. While Xrcc1 inactivation during neurogenesis selectively affects cerebellar interneuron populations by arresting the cell cycle in interneuron progenitors, and produces abnormal hippocampal activity correlated with sporadic seizures (7), Polb inactivation by itself in the nervous system selectively reduced cortical interneurons in the absence of behavioral and cerebellar abnormalities, despite the fact that XRCC1 and POLB work coordinately for base damage repair (9,17). The different neurophenotypes resulting from Polb and Xrcc1 inactivation might be influenced by redundant or compensatory functions from other DNA polymerases taking part in BER, such as DNA polymerase delta, epsilon and lambda (17,45). However, their exclusive roles in the nervous system have not yet been explored. Apparently, other XRCC1 binding proteins, such as LIG3, TDP1, PNKP and APEX1, play their distinct roles during neurogenesis and brain function, different from those of XRCC1 (11,13–15,46). Nevertheless, Polb inactivation in the brain resulted in chronic DNA damage, particularly in the cerebellum, evidenced by ATM phosphorylation, γ-H2AX foci formation, and dense glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity. Genomic instability in the Polb null cerebellum was manifested as medulloblastoma formation, the most common pediatric brain tumor mainly located in the cerebellum, in p53 deficiency (47), similarly as in other animal models of genomic instability in a p53 null background (7,14,48–50).

Atm deficiency in the cerebellum in conjunction with chronic DNA damage from Polb inactivation led to severe cerebellar ataxia without apparent neuropathological defects and to reduced Itpr1 expression in Purkinje cells. Reduced Itpr1 expression was also observed in the cerebella of ataxic Xrcc1 and Atm double null animals, suggesting that Itpr1 reduction in the cerebellum may be one of contributing factors to cerebellar ataxia resulting from genomic instability. The main function of ITPR1, expressed exclusively in Purkinje cells which are rich with calcium binding proteins, such as calbindin and parvalbumin, is to release calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum (33,51,52). Purkinje cells integrate the large number of neural input signals from various cerebellar interneurons, parallel fibers and climbing fibers to coordinate motor movements (Figue 6). As calcium balance is critical for maturation and normal function of Purkinje cells, a disturbance of calcium homeostasis in the cerebellum eventually leads to ataxia (33,53,54). Accordingly, ITPR1 mutations are implicated in human genetic diseases with progressive ataxia such as Spinocerebellar ataxia 15/29 and Gillespie syndrome, for which cerebellar ataxia and aberrant calcium spikes in Purkinje cells have been demonstrated in animal models for Itpr1 mutations (19–20,33–35,55).

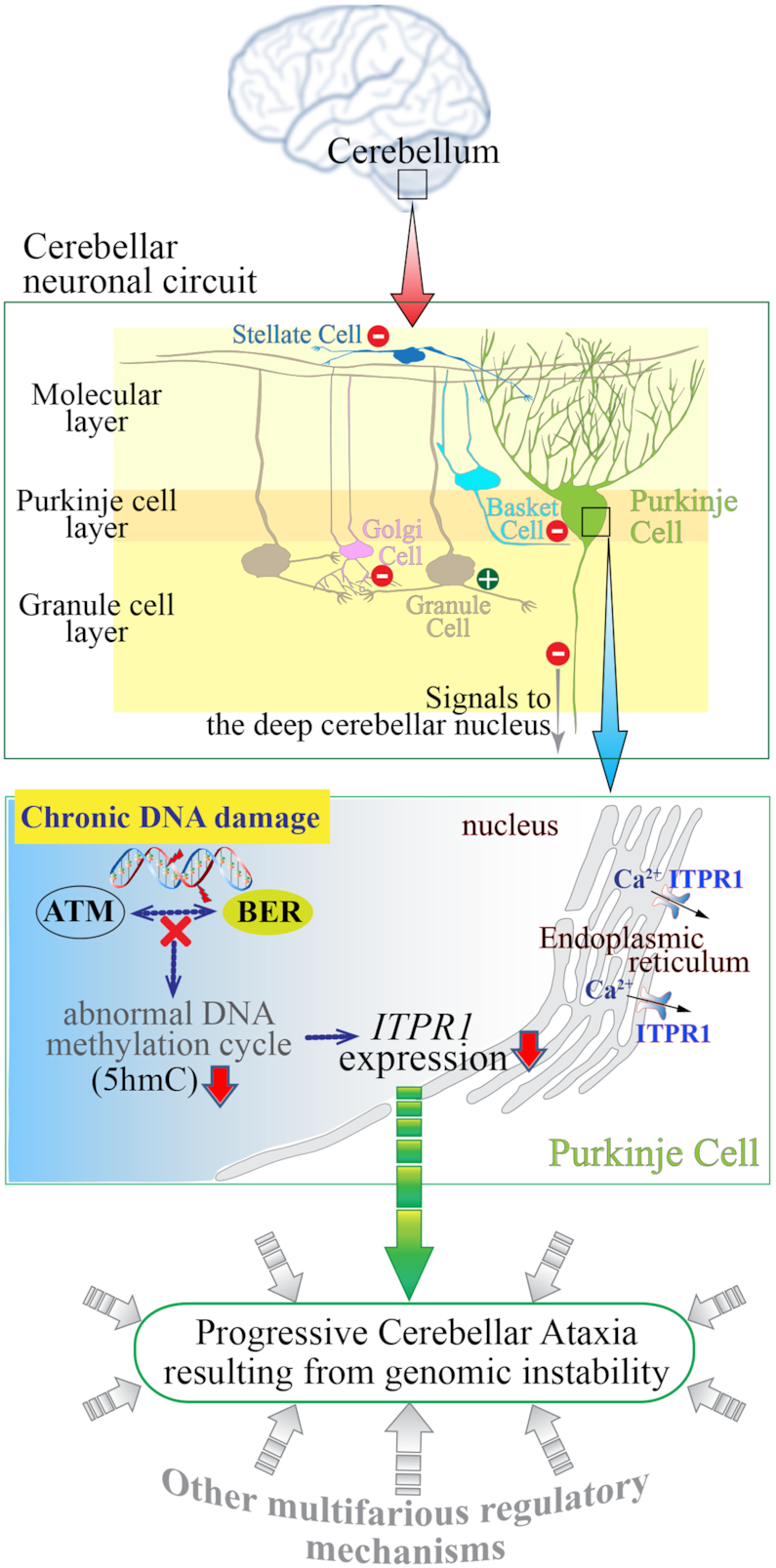

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram showing the consequences of genomic instability resulting from defective BER and ATM deficiency in the cerebellum leading to ataxia. The cerebellum, which is located at the back of the brain and is involved in the coordination of motor movement, comprises distinct cellular layers: the molecular layer, Purkinje layer and granule cell layer. Purkinje cell axons transmit inhibitory signals (−) to the deep cerebellar nucleus while integrating inhibitory inputs (−) from interneurons (Stellate and Basket cells) in the molecular layer and excitatory inputs (+) from Granule cells which are under the inhibitory control (−) of Golgi cells in the granule cell layer, as well as (+) inputs from the climbing fibers (not shown). As the only neuronal output is from the Purkinje cells, their dysfunction leads to abnormal coordination of movement (ataxia). Improper responses to chronic DNA damage in the cerebellum due to faulty base excision repair (BER) and ATM dysfunction likely result in various defects, including aberrant DNA methylation and consequently reduced ITPR1 expression in Purkinje cells. ITPR1 is involved in homeostatic control of Ca2+ levels necessary for normal Purkinje cell function (54). This physiological condition might be one of contributing factors to cerebellar ataxia resulting from genomic instability.

Interestingly, the cerebella from A-T patients showed differential alteration of the 5mC and 5hmC levels in gene loci compared to normal cerebella, which was not noticeable in the A-T cerebral cortices, and ITPR1 was one of genes altered substantially in the A-T cerebella (37), though it is not clear if this is a cause or consequence of Purkinje cell neurodegeneration in A-T patients. In addition, the expression of ITPR1 was reduced in cerebellar neurons derived from A-T patient specific induced pluripotent stem cells, compared with that of normal controls (56). The analyses of cerebrospinal fluid from A-T patients and cerebellar transcripts from Atm−/− animals suggested calcium homeostasis is one of affected physiological conditions in the ATM null cerebellum (57). Furthermore, it has been proposed that an impairment of calcium homeostasis may be predegenerative lesions to Purkinje cell degeneration in A-T patients, as progressive calcium deficits were observed in the Purkinje cells of another Atm null animal model (58).

The Purkinje cell layer is vulnerable to a diversity of genetic insults (1,53), and these cells exhibit a highly dynamic cycle of cytosine demethylation and remethylation, which can influence gene expression (59). Given the previous demonstrations that Polb-dependent BER is necessary for DNA demethylation in the nervous system (60), and that ATM controls TET1 enzyme activity, which converts 5mC to 5hmC, in the cerebellum upon DNA damage (37), our data suggest that a misregulation of cytosine methylation in the Itpr1 gene caused in part by diminished TET1 enzyme activity results in reduced Itpr1 expression in the cerebellum, leading to the neuronal vulnerability associated with cerebellar ataxia. Thus, Atm deficiency likely contributes to reduced Itpr1 expression in the cerebellum under a condition of chronic DNA damage.

As illustrated in Figure 6, ATM and BER are necessary for proper cerebellar function. Defective BER in association with Atm deficiency in the cerebellum results in chronic DNA damage that leads to cerebellar ataxia, in part by reducing Itpr1 expression in connection with epigenetic misregulation. The findings presented here contribute another piece to the large puzzle of how cerebellar ataxia is initiated and how it progresses in human patients with genomic instability. Cerebellar ataxia resulting from genomic instability cannot be explained by one or two regulatory mechanisms. The various molecular mechanisms should be involved in the progression of cerebellar ataxia, as exemplified by the diverse functions of ATM to maintain cellular homeostasis (41). Perhaps ITPR1 reduction is one of common denominators in the prodromal phase of progressive cerebellar ataxia in various genomic instability disorders. Further analyses of the double knockout animal model with extended lifespans as a result of additional genetic modification or pharmacological intervention for calcium homeostasis will help us to examine in greater detail the neurodegenerative attributes and underlying mechanisms related to ataxia in the Polb and Atm double null cerebellum.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Laboratory Animal Research Center (LARC) of Ajou University Medical Center for animal husbandry. We also thank Dr. Peter McKinnon for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable discussions.

Author Contributions’: Y.S.L. conceived the idea; J.S.K., K.E.K., J.S.M. and Y.S.L. performed the experiments and analyzed data; J.S.K., K.E.K. and J.S.M. contributed to the manuscript; and Y.S.L. finalized the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning) [2014R1A1A2056224, 2017R1A2B2009284]. Funding for open access charge: National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planing) [2017R1A2B2009284].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee Y., Choi I., Kim J., Kim K.. DNA damage to human genetic disorders with neurodevelopmental defects. J. Genet. Med. 2016; 13:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKinnon P.J. Genome integrity and disease prevention in the nervous system. Genes Dev. 2017; 31:1180–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blackford A.N., Jackson S.P.. ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK: The trinity at the heart of the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. 2017; 66:801–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McKinnon P.J., Caldecott K.W.. DNA strand break repair and human genetic disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2007; 8:37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madabhushi R., Pan L., Tsai L.H.. DNA damage and its links to neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2014; 83:266–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Caldecott K.W. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008; 9:619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee Y., Katyal S., Li Y., El-Khamisy S.F., Russell H.R., Caldecott K.W., McKinnon P.J.. The genesis of cerebellar interneurons and the prevention of neural DNA damage require XRCC1. Nat. Neurosci. 2009; 12:973–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caldecott K.W. DNA single-strand break repair. Exp. Cell Res. 2014; 329:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caldecott K.W. XRCC1 protein; Form and function. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2019; 81:102664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahel I., Rass U., El-Khamisy S.F., Katyal S., Clements P.M., McKinnon P.J., Caldecott K.W., West S.C.. The neurodegenerative disease protein aprataxin resolves abortive DNA ligation intermediates. Nature. 2006; 443:713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao Y., Katyal S., Lee Y., Zhao J., Rehg J.E., Russell H.R., McKinnon P.J.. DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair. Nature. 2011; 471:240–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katyal S., el-Khamisy S.F., Russell H.R., Li Y., Ju L., Caldecott K.W., McKinnon P.J.. TDP1 facilitates chromosomal single-strand break repair in neurons and is neuroprotective in vivo. EMBO J. 2007; 26:4720–4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Katyal S., Lee Y., Nitiss K.C., Downing S.M., Li Y., Shimada M., Zhao J., Russell H.R., Petrini J.H., Nitiss J.L. et al.. Aberrant topoisomerase-1 DNA lesions are pathogenic in neurodegenerative genome instability syndromes. Nat. Neurosci. 2014; 17:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dumitrache L.C., Shimada M., Downing S.M., Kwak Y.D., Li Y., Illuzzi J.L., Russell H.R., Wilson D.M. 3rd, McKinnon P.J.. Apurinic endonuclease-1 preserves neural genome integrity to maintain homeostasis and thermoregulation and prevent brain tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018; 115:E12285–E12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimada M., Dumitrache L.C., Russell H.R., McKinnon P.J.. Polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase enables neurogenesis via multiple DNA repair pathways to maintain genome stability. EMBO J. 2015; 34:2465–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoch N.C., Hanzlikova H., Rulten S.L., Tetreault M., Komulainen E., Ju L., Hornyak P., Zeng Z., Gittens W., Rey S.A. et al.. XRCC1 mutation is associated with PARP1 hyperactivation and cerebellar ataxia. Nature. 2017; 541:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krokan H.E., Bjoras M.. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013; 5:a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu X., Zhang Y.. TET-mediated active DNA demethylation: mechanism, function and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017; 18:517–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van de Leemput J., Chandran J., Knight M.A., Holtzclaw L.A., Scholz S., Cookson M.R., Houlden H., Gwinn-Hardy K., Fung H.C., Lin X. et al.. Deletion at ITPR1 underlies ataxia in mice and spinocerebellar ataxia 15 in humans. PLos Genet. 2007; 3:e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egorova P.A., Bezprozvanny I.B.. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and neurodegenerative disorders. FEBS J. 2018; 285:3547–3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu H., Marth J.D., Orban P.C., Mossmann H., Rajewsky K.. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994; 265:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li L.C., Dahiya R.. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002; 18:1427–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petterson A., Chung T.H., Tan D., Sun X., Jia X.Y.. RRHP: a tag-based approach for 5-hydroxymethylcytosine mapping at single-site resolution. Genome Biol. 2014; 15:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sugo N., Niimi N., Aratani Y., Takiguchi-Hayashi K., Koyama H.. p53 deficiency rescues neuronal apoptosis but not differentiation in DNA polymerase beta-deficient mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004; 24:9470–9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Butt S.J., Stacey J.A., Teramoto Y., Vagnoni C.. A role for GABAergic interneuron diversity in circuit development and plasticity of the neonatal cerebral cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017; 43:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sugo N., Aratani Y., Nagashima Y., Kubota Y., Koyama H.. Neonatal lethality with abnormal neurogenesis in mice deficient in DNA polymerase beta. EMBO J. 2000; 19:1397–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee Y., Barnes D.E., Lindahl T., McKinnon P.J.. Defective neurogenesis resulting from DNA ligase IV deficiency requires Atm. Genes Dev. 2000; 14:2576–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lang P.Y., Nanjangud G.J., Sokolsky-Papkov M., Shaw C., Hwang D., Parker J.S., Kabanov A.V., Gershon T.R.. ATR maintains chromosomal integrity during postnatal cerebellar neurogenesis and is required for medulloblastoma formation. Development. 2016; 143:4038–4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leto K., Bartolini A., Rossi F.. Development of cerebellar GABAergic interneurons: origin and shaping of the “minibrain” local connections. Cerebellum. 2008; 7:523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Turkmen S., Guo G., Garshasbi M., Hoffmann K., Alshalah A.J., Mischung C., Kuss A., Humphrey N., Mundlos S., Robinson P.N.. CA8 mutations cause a novel syndrome characterized by ataxia and mild mental retardation with predisposition to quadrupedal gait. PLos Genet. 2009; 5:e1000487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aspatwar A., Tolvanen M.E., Ortutay C., Parkkila S.. Carbonic anhydrase related protein VIII and its role in neurodegeneration and cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010; 16:3264–3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsumoto M., Nakagawa T., Inoue T., Nagata E., Tanaka K., Takano H., Minowa O., Kuno J., Sakakibara S., Yamada M. et al.. Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature. 1996; 379:168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimobayashi E., Kapfhammer J.P.. Calcium Signaling, PKC Gamma, IP3R1 and CAR8 Link Spinocerebellar Ataxias and Purkinje cell dendritic development. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018; 16:151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schorge S., van de Leemput J., Singleton A., Houlden H., Hardy J.. Human ataxias: a genetic dissection of inositol triphosphate receptor (ITPR1)-dependent signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2010; 33:211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tada M., Nishizawa M., Onodera O.. Roles of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in spinocerebellar ataxias. Neurochem. Int. 2016; 94:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lyko F. The DNA methyltransferase family: a versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018; 19:81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang D., Zhang Y., Hart R.P., Chen J., Herrup K., Li J.. Alteration in 5-hydroxymethylcytosine-mediated epigenetic regulation leads to Purkinje cell vulnerability in ATM deficiency. Brain. 2015; 138:3520–3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shamma A., Suzuki M., Hayashi N., Kobayashi M., Sasaki N., Nishiuchi T., Doki Y., Okamoto T., Kohno S., Muranaka H. et al.. ATM mediates pRB function to control DNMT1 protein stability and DNA methylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013; 33:3113–3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thevenon J., Lopez E., Keren B., Heron D., Mignot C., Altuzarra C., Beri-Dexheimer M., Bonnet C., Magnin E., Burglen L. et al.. Intragenic CAMTA1 rearrangements cause non-progressive congenital ataxia with or without intellectual disability. J. Med. Genet. 2012; 49:400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McKinnon P.J. ATM and the molecular pathogenesis of ataxia telangiectasia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012; 7:303–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choy K.R., Watters D.J.. Neurodegeneration in ataxia-telangiectasia: multiple roles of ATM kinase in cellular homeostasis. Dev. Dyn. 2018; 247:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lavin M.F. The appropriateness of the mouse model for ataxia-telangiectasia: neurological defects but no neurodegeneration. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2013; 12:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herzog K.H., Chong M.J., Kapsetaki M., Morgan J.I., McKinnon P.J.. Requirement for Atm in ionizing radiation-induced cell death in the developing central nervous system. Science. 1998; 280:1089–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee Y., Chong M.J., McKinnon P.J.. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated-dependent apoptosis after genotoxic stress in the developing nervous system is determined by cellular differentiation status. J. Neurosci. 2001; 21:6687–6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Braithwaite E.K., Prasad R., Shock D.D., Hou E.W., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. DNA polymerase lambda mediates a back-up base excision repair activity in extracts of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:18469–18475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Katyal S., McKinnon P.J.. Disconnecting XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Cell Cycle. 2011; 10:2269–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim J., Kim J., Lee Y.. DNA polymerase beta deficiency in the p53 null cerebellum leads to medulloblastoma formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018; 505:548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee Y., McKinnon P.J.. DNA ligase IV suppresses medulloblastoma formation. Cancer Res. 2002; 62:6395–6399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Frappart P.O., Lee Y., Lamont J., McKinnon P.J.. BRCA2 is required for neurogenesis and suppression of medulloblastoma. EMBO J. 2007; 26:2732–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Frappart P.O., Lee Y., Russell H.R., Chalhoub N., Wang Y.D., Orii K.E., Zhao J., Kondo N., Baker S.J., McKinnon P.J.. Recurrent genomic alterations characterize medulloblastoma arising from DNA double-strand break repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:1880–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bastianelli E. Distribution of calcium-binding proteins in the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2003; 2:242–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leto K., Arancillo M., Becker E.B., Buffo A., Chiang C., Ding B., Dobyns W.B., Dusart I., Haldipur P., Hatten M.E. et al.. Consensus Paper: Cerebellar development. Cerebellum. 2016; 15:789–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huang M., Verbeek D.S.. Why do so many genetic insults lead to Purkinje Cell degeneration and spinocerebellar ataxia. Neurosci. Lett. 2019; 688:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hoxha E., Balbo I., Miniaci M.C., Tempia F.. Purkinje cell signaling deficits in animal models of Ataxia. Front. Synaptic. Neurosci. 2018; 10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Crepel F., Dupont J.L., Gardette R.. Selective absence of calcium spikes in Purkinje cells of staggerer mutant mice in cerebellar slices maintained in vitro. J. Physiol. 1984; 346:111–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nayler S.P., Powell J.E., Vanichkina D.P., Korn O., Wells C.A., Kanjhan R., Sun J., Taft R.J., Lavin M.F., Wolvetang E.J.. Human iPSC-Derived cerebellar neurons from a patient with Ataxia-Telangiectasia reveal disrupted gene regulatory networks. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017; 11:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Canet-Pons J., Schubert R., Duecker R.P., Schrewe R., Wolke S., Kieslich M., Schnolzer M., Chiocchetti A., Auburger G., Zielen S. et al.. Ataxia telangiectasia alters the ApoB and reelin pathway. Neurogenetics. 2018; 19:237–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chiesa N., Barlow C., Wynshaw-Boris A., Strata P., Tempia F.. Atm-deficient mice Purkinje cells show age-dependent defects in calcium spike bursts and calcium currents. Neuroscience. 2000; 96:575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhou F.C., Resendiz M., Lo C.L., Chen Y.. Cell-Wide DNA De-Methylation and Re-Methylation of Purkinje neurons in the developing cerebellum. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0162063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Onishi K., Uyeda A., Shida M., Hirayama T., Yagi T., Yamamoto N., Sugo N.. Genome stability by DNA polymerase beta in neural progenitors contributes to neuronal differentiation in cortical development. J. Neurosci. 2017; 37:8444–8458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.