Abstract

To sustain iron homeostasis, microorganisms have evolved fine-tuned mechanisms for uptake, storage and detoxification of the essential metal iron. In the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus, the fungal-specific bZIP-type transcription factor HapX coordinates adaption to both iron starvation and iron excess and is thereby crucial for virulence. Previous studies indicated that a HapX homodimer interacts with the CCAAT-binding complex (CBC) to cooperatively bind bipartite DNA motifs; however, the mode of HapX-DNA recognition had not been resolved. Here, combination of in vivo (genetics and ChIP-seq), in vitro (surface plasmon resonance) and phylogenetic analyses identified an astonishing plasticity of CBC:HapX:DNA interaction. DNA motifs recognized by the CBC:HapX protein complex comprise a bipartite DNA binding site 5′-CSAATN12RWT-3′ and an additional 5′-TKAN-3′ motif positioned 11–23 bp downstream of the CCAAT motif, i.e. occasionally overlapping the 3′-end of the bipartite binding site. Phylogenetic comparison taking advantage of 20 resolved Aspergillus species genomes revealed that DNA recognition by the CBC:HapX complex shows promoter-specific cross-species conservation rather than regulon-specific conservation. Moreover, we show that CBC:HapX interaction is absolutely required for all known functions of HapX. The plasticity of the CBC:HapX:DNA interaction permits fine tuning of CBC:HapX binding specificities that could support adaptation of pathogens to their host niches.

INTRODUCTION

Iron is a redox catalyst for many essential cellular processes, however, in excess it can result in the liberation of toxic levels of reactive oxygen species (1,2). Consequently, adaptation to iron starvation as well as iron excess is essential for survival in dynamically changing growth niches. In the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus, HapX is a basic region leucine zipper (bZIP) protein that acts as a Janus type transcription factor to mediate this adaptation (3,4). Under iron starvation, HapX is involved in repression of iron-dependent pathways and activation of iron acquisition. During iron excess, HapX activates iron dependent pathways, particularly vacuolar iron deposition, which appears to be the major mechanism of iron detoxification.

Orthologs of HapX have been shown to be crucial for maintaining iron homeostasis in several filamentous ascomycetes, i.e., in Aspergillus nidulans (5), Fusarium oxysporum (6), Fusarium graminearum and Verticillium dahliae (7,8), as well as in the yeast ascomycete Candida albicans (9–11) and the yeast basidiomycete Cryptococcus neoformans (12), demonstrating the functional conservation of this transcription factor within the fungal kingdom. During infection, A. fumigatus has to survive in an environment where levels of free iron are tightly regulated by the host. Adaptation to this iron-poor host niche is an important virulence attribute of pathogens. Indeed, genetic inactivation of HapX was shown to attenuate virulence of A. fumigatus in murine models of pulmonary aspergillosis (4). Likewise, HapX orthologs are essential for full virulence of both plant- (F. oxysporum and V. dahliae) (6,8) as well as animal-pathogenic fungal species (C. albicans and C. neoformans) (9,12), albeit with a rather modest role in C. neoformans.

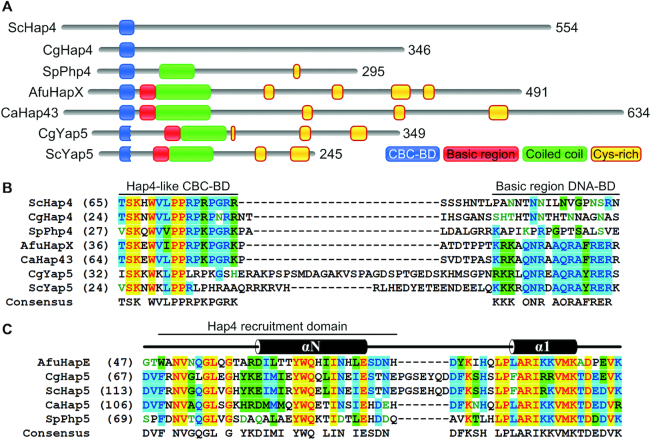

The A. fumigatus HapX protein consists of 491 amino acid (aa) residues and harbors several phylogenetically conserved domains (Figure 1). DNA-binding is thought to be mediated by the basic region of its bZIP domain (13); however, this domain alone is insufficient to allow high-affinity DNA binding (3). Previous studies suggested that HapX promoter-specific DNA-binding requires intermolecular protein-protein interaction with an additional DNA-binding factor, the CCAAT-binding complex (CBC). The CBC is a heterotrimeric protein complex conserved in all eukaryotes, and is known as Nuclear Factor Y (NF-Y) in mammals, HapB/C/E complex in Aspergillus spp. and Hap2/3/5 complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14). Early evidence demonstrating how the CBC interacts with its binding partners was revealed in S. cerevisiae, where the transcriptional subunit Hap4 activates genes involved in gluconeogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation during glucose deprivation or growth on non-fermentable carbon sources by physical interaction with the core CBC. A very short 16 aa stretch of Hap4 was proven to be required for association with Hap2/3/5 and Hap4 function (15,16). HapX lacks any significant sequence identity to Hap4 with the sole exception of this Hap4-like CBC binding domain (CBC-BD; Figure 1).

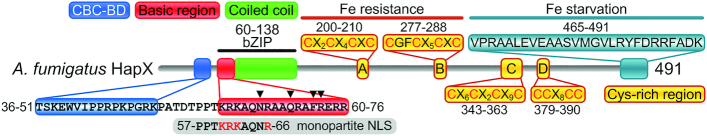

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the A. fumigatus HapX domain organization. The N-terminal Hap4-like CBC binding domain (CBC-BD) is shown in blue. Basic region and coiled coil parts of the bZIP domain are depicted in red and green, respectively. Cysteine-rich regions are marked in yellow. Cysteine-rich regions A and B are essential for HapX function during iron excess but not during iron starvation, while the C-terminus is crucial during iron starvation (shown in turquois). Residues N65, Q69, F72 and R73, which mediate specific DNA contacts in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe bZIP Pap1:DNA complex (17), are labeled with a black triangle. The location of a putative monopartite nuclear localization sequence (NLS) motif identified within the Aspergillus oryzae HapX basic region (18) is shown in grey.

In A. nidulans, the CBC-BD was shown to be essential for interaction with the HapX recruitment domain of the CBC subunit HapE and this interaction was found to be essential for repression of iron consuming pathways during iron starvation (5). In A. fumigatus, the HapX C-terminus was identified to be essential for coping with iron deficiency, while two cysteine-rich regions, termed CRR-A and CRR-B, were identified as essential for iron resistance (3). The presence of both of these CRRs in most HapX orthologs implicates conservation of their role in iron resistance (3). However, the HapX ortholog Hap43 and its phylogenetically conserved CRR-A and CRR-B domains were found to be almost dispensable for iron resistance in C. albicans (19,20). Hence, Hap43 is mainly involved in the repression of iron consuming pathways.

In the Saccharomycotina species S. cerevisiae and Candida glabrata, the bZIP-type transcription factor Yap5, which contains both the CRR-B and a rudimentary Hap4-like domain, acts as a CBC regulatory subunit for coping with high iron stress (21–26). Despite the lack of Yap5 function in adaptation to iron starvation, the role in iron resistance and the common protein domains indicate homology of Yap5, HapX and Hap43. Evolutionary aspects of the development of these transcription factors have been discussed extensively in two recent reviews (27,28).

Cooperative binding of HapX and the CBC to bipartite DNA motifs has been shown to be important for repression of iron-consuming pathways in A. nidulans (5,13). In A. fumigatus, cooperative DNA binding by the CBC and HapX has been shown in vitro but formal in vivo evidence has not been demonstrated (3,29). The consensus sequence of the CBC binding motif, 5′-CCAATVR-3′, is largely conserved in most target genes (29,30). DNA-binding loci of HapX have been identified in promoters of only three genes, namely those that encode the A. nidulans cytochrome c (CycA), the A. fumigatus vacuolar iron transporter CccA, and the A. fumigatus 14-α sterol demethylase Cyp51A (3,13,29). Remarkably, no discernable shared motif is evident between these HapX-recognized regions. Furthermore, Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation (MEME) analysis (31) of promoters regulated by Hap43, the HapX ortholog of C. albicans, revealed only the signature CCAAT sequence of the CBC (11). Taken together, these data indicated low conservation of the DNA sequence recognized by HapX/Hap43-type transcription factors leaving the mode of specific DNA-binding by HapX elusive.

In the current study, we sought to elucidate the cooperative DNA-binding pattern of HapX and the CBC. We identified three prerequisites, represented by individual motifs, for high-affinity recognition of CBC:HapX target genes. A CBC-binding site with the consensus sequence 5′-CSAAT-3′ recognized by the CBC and, unexpectedly, two 3′-downstream HapX recognition sites. The first motif recognized by HapX is a conserved A/T-rich trinucleotide (5′-RWT-3′) located exactly 12 bp downstream of the CBC-binding site. The second consists of single or overlapping 5′-T(T/G)AN bZIP half-sites. Surprisingly, the latter site displays a high degree of variation in terms of relative orientation and distance to the 5′-CSAAT-3′ motif, resulting in highly variable site specificities. Furthermore, we demonstrate that both interaction with the CBC and DNA-binding is essential for all known functions of HapX during both iron starvation and iron excess.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains, growth conditions

A. fumigatus strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For ChIP-seq analysis, three A. fumigatus strains sharing the A1160P+ genetic background were used: hapCGFP, venushapX and NLS-Venus. In the previously described strain hapCGFP (29), HapC is C-terminally tagged with GFP and expression of the encoding gene is under control of the native promoter. In strain venushapX, HapX is N-terminally tagged with yellow fluorescent protein derivative Venus and expression of the encoding gene is under control of the native promoter. In strain NLS-Venus, a nuclear localization signal (NLS; PKKKRKV) derived from the Simian Virus 40 (SV40) large T-antigen is fused with Venus and expression of the fusion gene is under control of the native hapX promoter. The generation of venushapX and NLS-Venus strains are described below. For ChIP-seq, fungal strains were cultivated at 37°C in Aspergillus Minimal Medium (AMM) according to (32) with 1% (w/v) glucose as carbon source and 20 mM ammonium tartrate as nitrogen source. Iron was omitted to mimic iron starvation. For iron-replete conditions, AMM contained 30 μM FeSO4. For growth phenotyping, Northern blot and siderophore production analysis, fungal strains were cultivated at 37°C in AMM with 1% (w/v) glucose as carbon source and 20 mM glutamine as nitrogen source. To increase iron depletion in solid minimal medium, 0.2 mM of the iron chelator bathophenanthroline disulfonate (BPS) was added. For high-iron conditions, AMM was supplemented with 5, 7.5 or 10 mM FeSO4. Growth assays were performed with either 104 or 108 conidia inoculated on solid medium or grown in 100 ml liquid culture, respectively.

N-terminal Venus-tagging of HapX (strain venushapX) in A. fumigatus A1160P+

To generate a hapX deletion mutant (ΔhapX) in A. fumigatus A1160P+, the hapX gene deletion cassette containing a ptrA resistance cassette and including 1 kb 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of hapX was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of an A. fumigatus AfS77 ΔhapX strain (3). This deletion construct was used for transformation of A1160P+ protoplasts, yielding a ΔhapX mutant. Strain ΔhapX was subsequently used as a recipient strain to integrate linearized plasmid phapXVENUS-hph (containing a hygromycin resistance cassette), yielding strain venushapX as described previously (3). Correct integration of constructs was verified by Southern blot analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Generation of an NLS-Venus producing A. fumigatus A1160P+ strain

To generate the NLS-Venus expression construct, a DNA fragment containing 1.2 kb 5′- and 1 kbp 3′-flanking regions of hapX was amplified by inverse PCR from phapXVENUS-hph (3) and assembled with a SV40 NLS-Venus fusion gene derived from plasmid pVenus-NLS using a NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly cloning kit (NEB). For construction of pVenus-NLS, a fragment from plasmid pV2A-T (33) was PCR amplified using primers Venus.521.R and Venus.522.F and re-ligated. Next, the NLS-Venus expression cassette was amplified by PCR from the assembled plasmid phapXP-NLS-Venus with the primers CRISPR-HX-P5 and CRISPR-HX-P6. The resultant NLS-Venus expression cassette includes 50 bp of homology arms to a non-functional transposon encoding atf4 locus of the A. fumigatus genome (Heys et al., unpublished data), and the construct was introduced to the atf4 locus of A. fumigatus A1160P+ using a CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome-editing system (34). Correct integration of the expression cassette was verified by PCR amplification of the regions immediately flanking the insertion site followed by Sanger sequencing. The primers and guide RNAs used for the generation and validation of NLS-Venus are listed in Supplementary Table S2D.

Prior to the preparation of ChIP-seq samples, we investigated phenotypes of NLS-Venus in the iron-replete and the iron depleted culture conditions and confirmed that there are no significant differences in their growth profiles compared to the wild-type strain (data not shown). We also confirmed that NLS-Venus expresses compatible levels of the venus transcripts with the venushapX transcripts in venushapX strain and the hapX transcripts in the wild-type strain. Furthermore, functional expression and nuclear localization of the NLS-Venus fusion protein were verified by microscopic observation and Western blotting (data not shown).

Generation of A. fumigatus venushapX ΔCBC-BD and venushapX DNA-BDm mutant strains in A. fumigatus AfS77

For deletion of A. fumigatus HapX CBC-BD (venushapX ΔCBC-BD) and mutation of HapX DNA-BD (venushapX DNA-BDm), plasmid phapXVENUS-hph (3) was used as template and modified using Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB). Primers used for generation of phapXVENUS-ΔCBC-BD-hph and phapXVENUS-DNA-BDm-hph are listed in Supplementary Table S2A. Deletion of HapX CBC-BD (amino acids 36–51) was introduced on plasmid phapXVENUS-hph by using primers oHapX-MM90 and oHapX-MM91 that flank the upstream and downstream regions of the CBC-BD. For mutation of four amino acids of the HapX DNA-BD, primers oHapX-MM92 and oHapX-MM93 were designed containing the desired nucleotide exchanges: asparagine (aa 65), glutamine (aa 69), phenylalanine (aa 72) and arginine (aa 73) were substituted to glutamic acid, glycine, serine and glutamic acid, respectively. A. fumigatus strain ΔhapX (3) was transformed with 5 μg plasmid phapXVENUS-ΔCBC-BD-hph or phapXVENUS-DNA-BDm-hph linearized through EcoRV digestion. A. fumigatus mutants were selected using 0.2 mg/ml hygromycin B. Correct single-copy integration at the hapX locus was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

ChIP-seq of VenusHapX and NLS-Venus

1 × 106 spores/ml of the VenusHapX or NLS-Venus producing strain were grown in 50 ml of Aspergillus minimal medium in the presence and the absence of iron for 24 h at 37°C with constant shaking at 180 rpm. Cross-linking was carried out by the addition of formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1.0% followed by incubation at 37°C for 20 min. Fixation was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM and continuing shaking for 10 min at 37°C. Mycelia were then collected by filtration, washed twice with distilled water and immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen and kept frozen at −80°C until used.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed essentially as described previously (29,35). Briefly, the cross-linked mycelia were ground to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen, and approximately 100 mg of the mycelial powder was suspended in 1.0 ml of ChIP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% deoxycholate (Sigma D6750), 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, and fungal proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)). The cell suspension was then sonicated with a Q125 sonicator (Qsonica, USA) to shear the chromatin to fragments with an average size of 0.2–0.5 kbp. After sonication, the insoluble cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the soluble fraction was used for ChIP experiments and input control preparations. ChIP reaction was performed with a GFP-polyclonal antibody (A-11122, Thermo Fischer Scientific) on Dynabeads Protein A magnetic beads (Thermo Fischer Scientific). Immunoprecipitated DNA was reverse cross-linked, treated with RNase A (Sigma), and then purified using a MinElute PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). To prepare input control, the sonicated extract was reverse cross-linked, treated with RNaseA (Sigma-Aldrich), and then purified using a MinElute PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). ChIP-seq libraries were constructed following the manufacturer's instructions for Illumina ChIP-seq library preparation. Each immunoprecipitated DNA sample was indexed and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500 as paired-end reads.

Raw sequencing reads were quality controlled with Illumina chastity filter and fastqc v0.11.3, and then Illumina adapters were trimmed from them using Trimmomatic v0.32. The resulting reads were aligned to the A. fumigatus A1163 genome from EnsemblGenomes fungi (36), version 28 using Bowtie2 v2.2.3. Peak calling was carried out to identify binding peak regions for VenusHapX using a Model-based Analysis for ChIP-Sequencing (MACS2) (37) version 2.1.0 with a q-value cutoff of 0.01 with input DNA as a control. Peak calling was also carried out for the NLS-Venus control samples using MACS2 without a control to identify non-specific background peak regions. Specificity of the HapX binding to the significant peak regions (>3-fold changes, q-value <0.01) was validated by cross-referencing the peak regions detected in the VenusHapX ChIP-seq and the NLS-Venus ChIP-seq datasets (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S3).

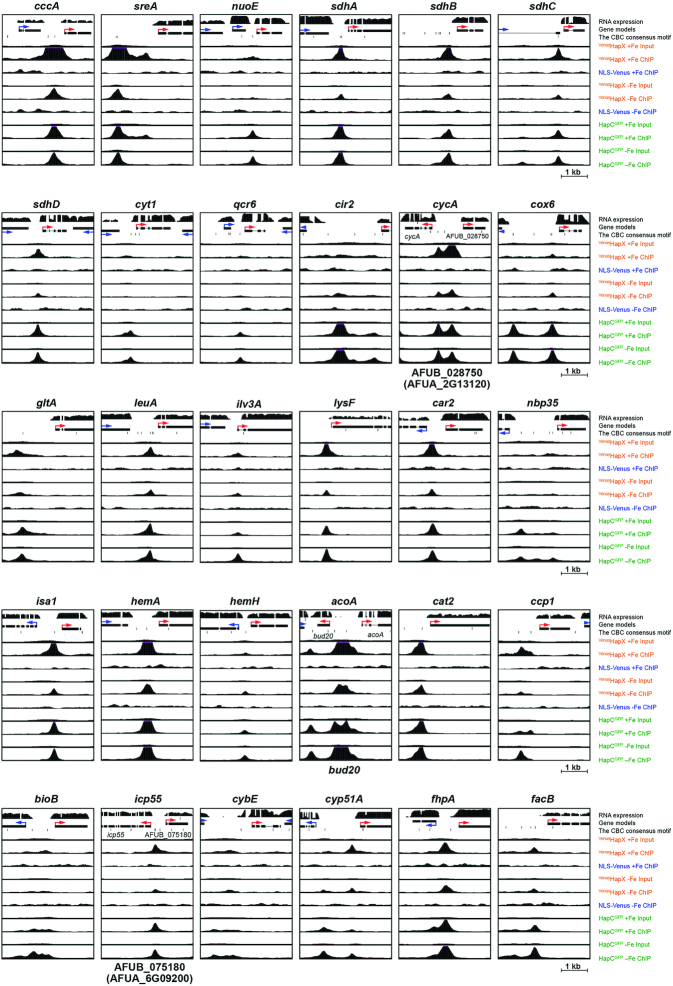

Figure 3.

Binding of HapX and the CBC on the promoter region of the selected 33 HapX-regulated genes. In vivo binding of VenusHapX and HapCGFP on the 5′-upstream region of the 33 HapX-regulated genes are shown. In cases where no A. fumigatus gene designation was assigned, we used the gene name of the respective S. cerevisiae ortholog. Tracks for the ChIP-seq (ChIP), their input DNA control (Input), and the binding specificity controls for HapX (NLS-Venus ChIP) are visualized in the UCSC genome browser together with annotated gene models and their transcript, which are expressed in RPMI-1640 culture conditions. RNA-seq data were taken from (49). Direction of the target gene and the proximal genes are shown in red arrows and blue arrows, respectively. The positions of the nucleotide motif matched with the consensus binding sequence for the CBC identified from our ChIP-seq analysis (5′-CCAATVR-3′) are also shown.

Results reported herein are for the combined reads from two biological replicate samples. All ChIP-seq experiments were carried out in two biological replicate samples.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene set enrichment analysis was carried out using the FungiFun2 2.2.8 BETA (38) web-based server (https://elbe.hki-jena.de/fungifun/fungifun.php) with the A. fumigtus A1163 genome annotation. Significance level of the enrichment was analyzed using the Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment method with a P-value cutoff <0.05.

Conserved motif discovery

The reproducible 150-bp of the merged peak regions with >3-fold (for VenusHapX) read enrichment compared to the corresponding control were subjected to conserved nucleotide motif discovery analysis using the MEME suite (31) version 5.1.0. DNA sequence of the ChIP peak regions were retrieved from the genomic locations using the getfasta function from the BED tools suite (39) and analyzed with the default setting.

Correlation analysis

The Spearman's rank-order correlation between HapX binding affinity (the KD value derived from SPR analysis) and the ChIP-seq fold enrichment was calculated using Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad).

Retrieval and selection of investigated promoter sequences

The genome files for the 20 Aspergillus species (Supplementary Table S8), and their respective gene annotations, were downloaded from AspGD (40). For each investigated promoter region, the respective gene was first retrieved as amino acid sequence and then, using blastp (41), blasted against a database including all the Aspergilli's annotated protein sequences. Best hits were collected and aligned with the respective sequence used as probes for blasting. The protein alignments were performed to investigate if the identified orthologs were correctly annotated. Those proteins having wrongly annotated sequences were manually re-annotated. Each group of orthologs was included in a single fasta file and the genome coordinates for each identified and/or re-annotated ORF were retrieved. This allowed to extract for each candidate the sequence corresponding to the upstream regulatory DNA region, directly from the Aspergilli chromosome contig files.

Promoter analysis

For promoter analysis either the upstream 2000, 1000, 500 bp regions or the complete 5′ intergenic non-coding regions were selected. The extracted sequences were grouped and successively aligned. Putative CBC:HapX binding motifs were identified using the MEME motif discovery tool provided by the MEME suite platform (31). To specify for bipartite CBC:HapX motifs the following parameters were used: motif width 6–50 bp; zero or one occurrence per sequence.

Purification of recombinant proteins and SPR analysis

The A. fumigatus CBC consisting of HapB(230–299), HapC(40–137) and HapE(47–164) as well as HapX(24–158) were produced and purified as described (3). Briefly, synthetic genes coding for HapB(230–299), HapC(40–137) and HapE(47–164) were cloned in the pnCS vector (42) for expression of a polycistronic transcript. The expression plasmid was transformed in E. coli BL21(DE3). After overnight autoinduction and cell lysis, the heterotrimeric CBC was purified to homogeneity by subsequent cobalt chelate affinity and size exclusion chromatography. A cDNA fragment encoding A. fumigatus HapX(24–158) with an extended N-terminus including a cleavage site for tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease was amplified and subcloned into the pMAL-c2X (New England Biolabs) vector. The resulting plasmid was transformed into E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells for overnight autoinduction. Crude bacterial lysates were purified by Dextrin Sepharose affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare). The maltose-binding protein HapX(24-158) fusion was cleaved with TEV protease and further purified sequentially using CellufineSulfate (Millipore) affinity chromatography, (NH4)2SO4 precipitation (50% w/v), and Superdex 75 prep grade (GE Healthcare) size exclusion chromatography. HapX mutant proteins (24–158 DNA-BDm, 59–158 ΔCBC-BD, 24–158 CgY5 and CgY5c) as well as the A. fumigatus Yap1(135–234) bZIP peptide were purified by the same procedure. Real-time SPR protein–DNA interaction measurements were performed by using protocols published previously (3,29).

Generation of lacZ reporter strains

The A. fumigatus cccA promoter was cloned upstream to the E. coli lacZ gene, containing the small terminator from the S. cerevisiae SLT2 gene, and inserted in the A. fumigatus pksP locus. The inactivation of pksP lead to albino colonies (43,44), which allowed phenotypical screening of positive recombinant strains. The cccA promoter was amplified from the A. fumigatus AfS77 genome with primers cccApro_for and cccApro_rev, cloned in a pJET2.1 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and sequenced. Promoter mutagenesis were performed by PCR using primers cccApro_tt_for and cccApro_tt_rev to obtain mutagenesis according to Figure 7B, and with primers cccApro_ccc_for and cccApro_ccc_rev to obtain mutagenesis according to Figure 7D, and with primers cccApro_ccc_for and cccApro_tt_rev to obtain both binding sites mutated. The positive clones were subsequently sequenced to confirm DNA mutagenesis. The wild type and the mutagenized promoters were amplified with primers cccAp.y1 and cccAp.y2 and fused with the lacZ coding gene, the ptrA cassette for pyrithiamine selection, and the two pksP flanking regions. The five fragments were assembled in the pYes2 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the transformation-associated recombination cloning in yeast. The gained plasmids were linearized and used to transform A. fumigatus strains AfS77 and ΔhapX respectively. Correct single copy integration of constructs was verified by Southern blot analysis (Supplementary Figure S2)

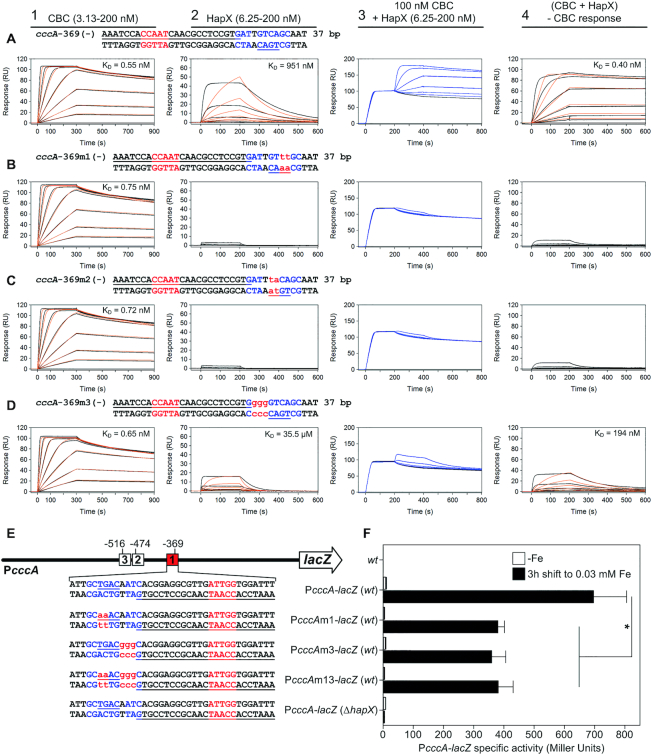

Figure 7.

In vitro and in vivo analysis of the regulatory function of HapX cccA promoter binding motifs. (A–D) SPR co-injection analysis of HapX binding to CBC bound A. fumigatus cccA promoter DNA duplexes carrying mutations within their conserved 5′-RWT-3′ and 5′-TKAN-3′ submotifs. Data are presented as described in figure legend 6. (E) Graphical representation of native or mutated A. fumigatus cccA promoter E. coli lacZ fusions integrated in single copy at the A. fumigatus pksP gene locus. Numbers indicate the positions of the three evolutionary conserved CBC:HapX binding sites (F) Effect of site 1 (-369) mutations on PcccA-lacZ expression after 18 h growth under iron depleted (−Fe) conditions followed by a 3 h shift of identical cultures to iron sufficiency (0.03 mM Fe). Iron dependent PcccA-lacZ expression was determined as β-galactosidase specific activity from soluble cell extracts. The host strains, AfS77 (wt) and ΔhapX, were used as negative controls. Data represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates.

β-Galactosidase activity assay

AMM media (50 ml) without iron were inoculated with 106 spores per ml and grown at 37°C and 180 rpm for 18 h. Subsequently the −Fe cultures were transferred into fresh shaker flasks and supplemented with 30 μM FeSO4. After additional 3 h of growth, the mycelia were harvested, dried, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Preparation of the proteins extracts and LacZ activity assays were performed as described previously (45) with three biological and three technical replicates (nine samples for each reporter strain).

Western blot analysis of HapX

Western blot analysis of A. fumigatus wild type and mutant protein levels was performed using a reported protocol (46). Briefly, lyophilized mycelial biomass was solubilized in NaOH, proteins were precipitated using trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and separated by SDS-PAGE using NuPAGE 4–12% (w/v) Bis–Tris gradient gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane using the iBlot 2 dry blotting system (Invitrogen). Western blots were reacted with rabbit α-HapX antiserum (1:20 000) and rabbit anti-β Actin (1:5000; abcam, ab119716) as primary antibodies and with peroxidase coupled anti-Rabbit IgG (1:10,000; Sigma, A1949) as secondary antibody. The membrane was developed using the 1-Step Ultra TMB-Blotting chromogenic substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Northern blot analysis

For northern blot analyses, total RNA was isolated using TRIsure™ reagent (Bioline) and analyzed as described previously (5). DIG-labeled hybridization probes were generated by PCR. Primers for amplification of hybridization probes are listed in Supplementary Table S2B.

Fluorescence microscopy

Visualization of A. fumigatus hyphae during iron starvation was performed as reported recently (3). In brief, fungal strains were cultivated on cover slips in 0.3 ml AMM without iron for 16 h. Microscopy pictures were taken by Axio Imager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss) and the AxioCam MRm camera (Carl Zeiss). Zen 2012 software (Carl Zeiss) was used to process images. Nuclei were stained by DAPI.

Measurement of siderophore production

Fungal strains were grown in liquid cultures under iron limitation conditions. After 24 h, the culture supernatants were transferred to new reaction tubes and saturated with FeSO4. Next, 0.2 volumes of chloroform or phenol: chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, PCI) were added for extraction of triacetylfusarinine C (TAFC) or extraction of total extracellular siderophores (TAFC and fusarinine C, FsC), respectively. After centrifugation, the chloroform or PCI phase was mixed with 5 volumes of diethylether and 1 volume of water. In a last step, the upper diethylether containing phase was removed and the amount of TAFC or TAFC + FsC in the aqueous phase was quantified spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a molar extinction coefficient of ϵ = 2996 M−1 cm−1 at 440 nm.

RESULTS

In vivo analysis reveals association of HapX with CBC DNA-binding sites in promoters of genes involved in iron homeostasis

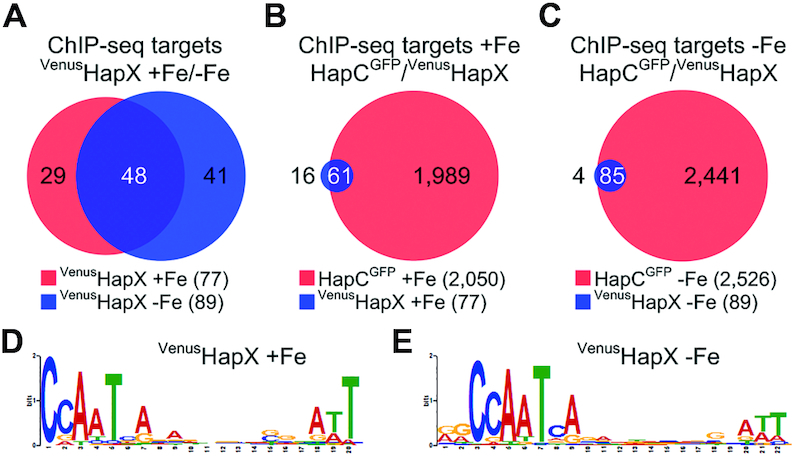

To identify genome-wide binding patterns of HapX, we performed ChIP-seq analysis using an A. fumigatus strain encoding an N-terminally Venus-tagged derivative of HapX (VenusHapX) in steady-state iron-replete (+Fe) and iron-starvation (−Fe) conditions. Peak calling revealed 581 and 1565 reproducible (n = 2, q-value < 0.01) genome wide HapX binding regions respectively, of which 297 (51%) and 606 (39%) are located within 1.5 kb of the 5′-upstream region of an annotated gene (Supplementary Table S3). Comparison of highly enriched ChIP-seq peaks (>3-fold enrichment, q-value <0.01) revealed that over 50% of the peak regions are common between the two conditions, indicating that at many promoters, HapX is bound irrespective of environmental iron concentrations (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Identification of common direct targets of HapX and the CBC by genome-wide ChIP-seq analysis and de novo discovery of a CBC:HapX motif. Venn diagrams showing comparison of ChIP-seq target sites of HapX and the CBC were depicted using a modified version of Cistrome software (47). For comparison of common ChIP-seq target sites, 150 bp sequences centered at the peak summit regions were used. The total number of ChIP-seq target sites is reported in parentheses. Numbers in white indicate how many ChIP sequence targets overlap in the respective comparison. (A) Comparison of the VenusHapX ChIP-seq target sites (>3-fold enrichment, found within the 1.5-kb of the 5′-upstream region) during iron sufficiency (+Fe) versus iron starvation (−Fe) conditions. (B) Comparison of the HapCGFP and the VenusHapX ChIP-seq target sites (>2-fold enrichment for the CBC, >3-fold enrichment for HapX, found within 1.5 kb of the 5′-upstream region) during +Fe conditions. (C) Comparison of the HapCGFP and the VenusHapX ChIP-seq target sites during −Fe conditions. CBC:HapX consensus DNA recognition motifs identified by MEME from the VenusHapX ChIP-seq peak summit regions for +Fe (D) and −Fe (E) conditions.

It has been shown that binding of the A. fumigatus HapX at several promoter regions is dependent on its interaction with the CBC (3,13,29). To assess if HapX is associated with the CBC at all of its binding sites and to obtain further evidence for the requirement of the CBC for target specific binding of HapX, we compared the HapX ChIP-seq datasets with CBC ChIP-seq datasets generated in a previous study using C-terminal GFP-tagged HapC (HapCGFP) (29). Of the significant HapX binding peaks (>3-fold changes, q-value <0.01), approximately 80% (+Fe) and 96% (−Fe) of the HapX peak regions showed overlap with the CBC peak regions that satisfy an arbitrary cut-off value (>2-fold changes, q-value < 0.01) (Figure 2B and C).

Further evaluation of the sites where our automated analysis could not confirm an association between HapX and CBC binding sites was performed by directly visualizing the ChIP-seq data mapped to the A. fumigatus A1163 genome using the UCSC genome browser. There are a total of four peak regions (2 for +Fe; region 13 and 16, and 2 for −Fe; region 18 and 20), within this cohort of the HapX binding peaks, in which we could not adequately assess their association with the CBC binding because of the inaccuracy of the sequencing output in the corresponding CBC ChIP-seq data (Supplementary Figure S7). However, from this analysis, we were able to confirm that all remaining loci bound by HapX were also bound by the CBC. These results, taken in the context of previously published data (3,13,29), indicate that HapX is indeed dependent on the CBC for binding its target sites in vivo.

To assess if the genes immediately downstream of the loci bound by HapX were functionally related, we performed gene set enrichment analysis for the 77 (+Fe) and 89 (−Fe) genes with significant HapX ChIP-seq peaks (>3-fold enrichment, q-value < 0.01) located within 1.5 kb of their 5′-upstream region. Prior to the downstream data analyses, specificity of the HapX binding to these significant ChIP-seq peak regions were confirmed by cross-referencing the peak regions detected in the VenusHapX ChIP-seq and the NLS-Venus background control ChIP-seq datasets (Supplementary Table S3). A total of 14 different FunCat categories with significant enrichment (P-value < 0.05) were identified. Consistent with our knowledge of the functional role of HapX, enriched functional categories were associated with the TCA cycle, electron transport, respiration, biosynthesis of leucine, heme binding, Fe/S binding, and heavy metal binding (Supplementary Figure S3).

Although numerous transcripts are dysregulated upon the loss of HapX (4), direct interaction of HapX has been confirmed at only three loci, namely the promoters of cccA, cyp51A and cycA (3,13,29). This has prevented any in depth evaluation of a consensus sequence for HapX binding. We have therefore carried out de novo motif discovery analysis using the MEME suite (31) using our HapX ChIP-seq data (>3-fold enrichment, q-value < 0.01). The highest scoring sequence (E-value: 4.6 × 10−28 for +Fe and E-value: 3.9 × 10−68 for −Fe conditions) was a bipartite nucleotide motif comprising 5′-CSAAT-3′ and 5′-RWT-3′ submotifs separated by a 12 bp non-conserved region. This bipartite motif was present in 63/77 (+Fe) and 82/89 (−Fe) of the HapX ChIP-seq binding peak regions (Figure 2D, E and Supplementary Table S4). The 5′-CSAAT-3′ submotif is a precise match for the CBC consensus site while the central non-conserved region affords the spatial requirements necessary for CBC binding as attachment of the CBC at the CCAAT motif would cover 13 nucleotides (nt) downstream of this binding site (30). This suggests that the 5′-RWT-3′ submotif marks a HapX specific recognition sequence. Interestingly, a bipartite structure for CBC:HapX complex binding has been proposed at both cccA (3) and cycA promoters (13). However, while these binding sites include the 5′-RWT-3′ signature located at position 13 bp downstream of the CCAAT box (cccA: 5′-13GATTGTCAGC-3′, cycA: 5′-GAT13GATTCA-3′), it is clear from our previous studies that additional nt proximal but outwith these sequences are required for efficient CBC:HapX:DNA interaction (3). This prompted us to speculate that some component of the HapX binding site may be promoter specific and hence not detectable using MEME analysis from genome-wide binding studies. We therefore decided to assess cross-species conservation in promoter sequences bound by HapX.

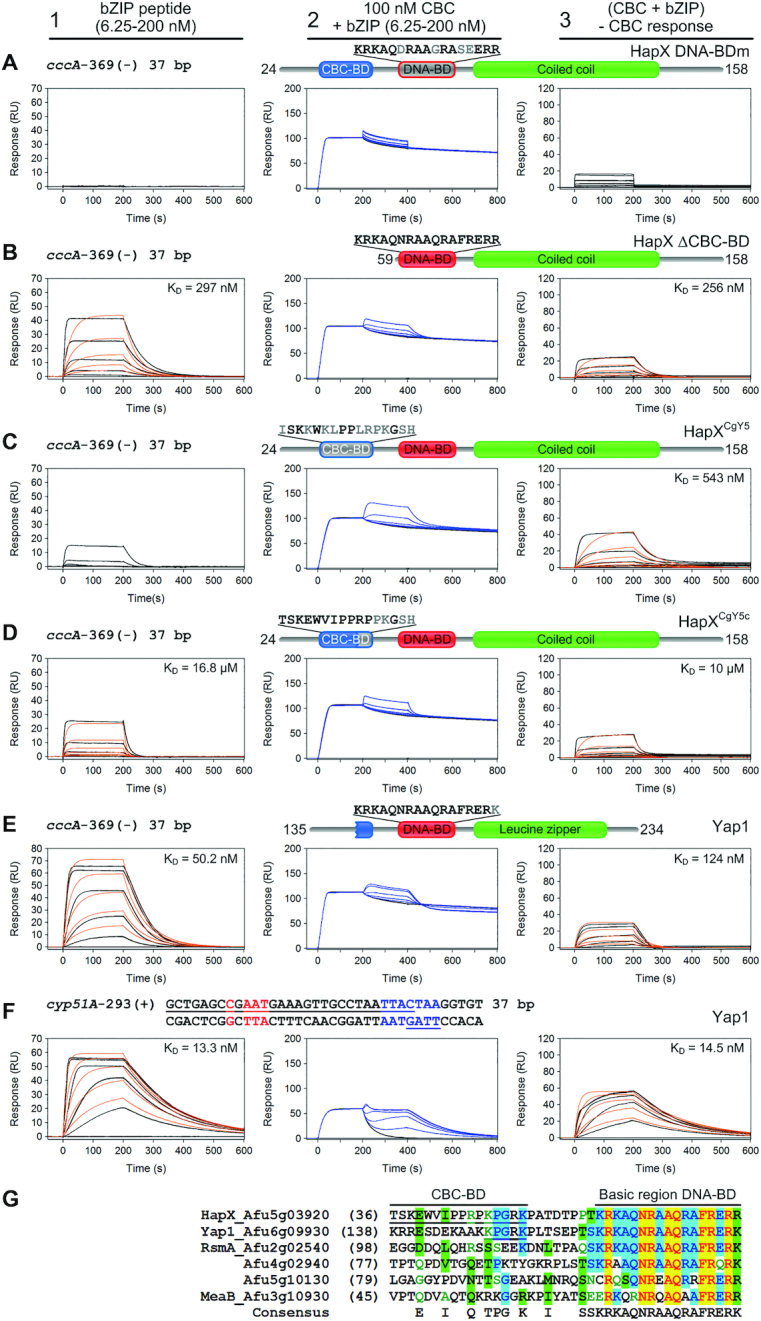

Cross-species analysis of promoters of orthologous genes identifies additional CBC:HapX target motifs

To enhance our chances of detecting additional function motifs we chose to assess binding sites that were identified in our ChIP-seq analysis and upstream of genes regulated in a HapX dependent manner. Previous microarray-based, genome-wide, transcriptional profiling has identified 131 genes that are repressed during iron starvation and short-term activated by iron in a HapX dependent manner (4,48). From this cohort, we selected the promoters of 33 genes where our ChIP-seq data indicated specific HapX binding (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S5).

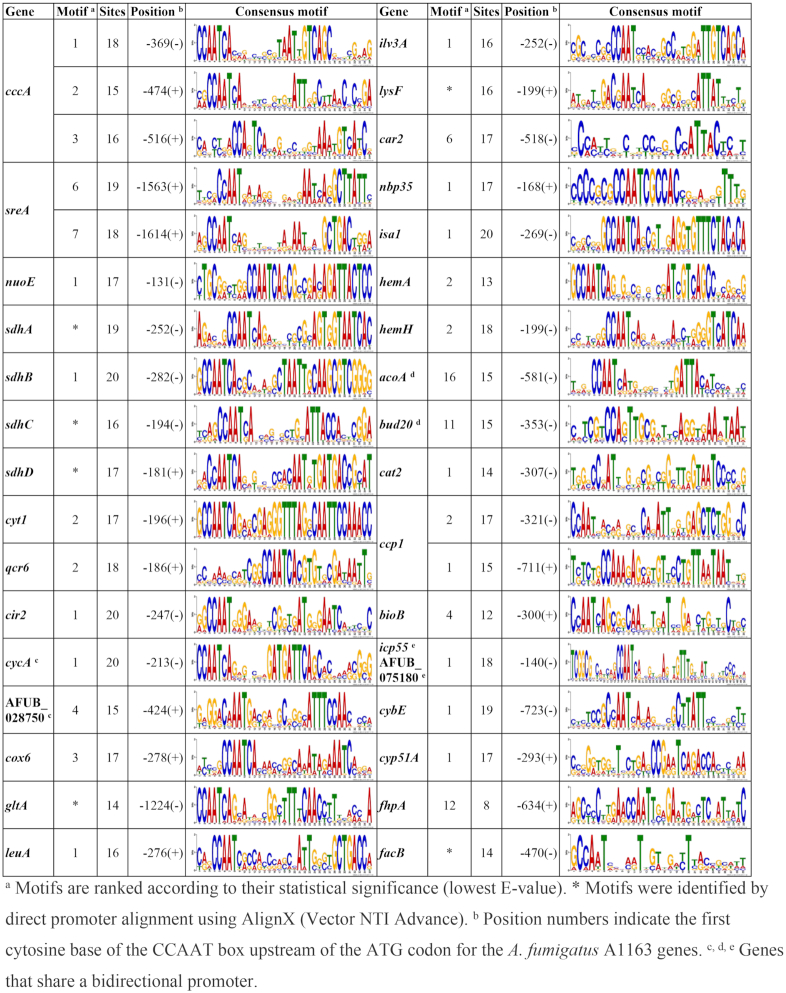

We used MEME analysis to search for evolutionary conserved regulatory motifs in the orthologous promoters across 20 Aspergillus species (Supplementary Table S8). This approach identified 35 conserved CCAAT-containing bipartite motifs in 32 of the 33 promoters (no conserved bipartite feature was observed in cyp51A) with more than one bipartite motif appearing in three genes (3-times in cccA; 2-times in sreA and ccp1, respectively) (Table 1). We observed higher levels of sequence conservation in the HapX bound promoters of orthologous genes (cross-species) than we saw between HapX bound promoters in A. fumigatus. The conserved gene-specific motifs that we identified were highly diverse (Table 1).

Table 1.

35 Phylogenetically conserved CCAAT-containing motifs in the orthologous promoter regions of 33 HapX-regulated genes from 20 Aspergillus spp.

|

Our data suggests that there could be significant evolutionary pressure acting at the CBC:HapX DNA-binding site of the promoters of several of these genes. The absence of a conserved bipartite CBC:HapX binding motif in the cyp51A promoter was a surprise as we had previously identified a critical region downstream of the CBC binding site that resembles a yeast Yap1-like bZIP binding site in the cyp51A promoter of A. fumigatus (29). Although a CGAAT-containing consensus motif was found (also displayed in Table 1) the Yap1-like bZIP binding site appears to be restricted to A. fumigatus and its closest relatives (data not shown). The bipartite CBC:HapX consensus motif predicted in 13 species at the hemA promoter was not identified in A. fumigatus indicating further species-specific binding sites. Manual inspection of the 5′ region of the A. fumigatus hemA combined with ChIP-seq analyses of strains producing GFP-tagged HapC or Venus-tagged HapX did however lead to the identification of a CBC:HapX binding site elsewhere in this promoter (Table 2). In addition, ChIP-seq analysis revealed that the fhpA promoter motif that was predicted by cross-species promoter MEME (CSP-MEME) at position −634 is not the prominent binding site targeted by CBC:HapX in A. fumigatus. However, the vast majority of CBC:HapX binding motifs do appear to be conserved in A. fumigatus. With a few exceptions (genes gltA, bioB, and cybE in −Fe conditions; cyt1, cir2 and gltA in +Fe conditions), all the motifs identified in the CSP-MEME analysis (Table 1) match VenusHapX ChIP-seq peak regions (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S6). Moreover, at least under one of the growth conditions, iron starvation or sufficiency, respectively, 22 of 33 promoters showed a HapX MEME site that matches the phylogenetically conserved motif derived from our CSP-MEME analysis (Supplementary Table S6). This excellent correlation of CBC:HapX DNA-binding sites, detected in vivo by ChIP-seq and predicted in silico by CSP-MEME, largely confirms the predictions of the phylogenetic conservation of CBC:HapX DNA-binding sites in Aspergilli and underlines the value of the cross-species comparison for in silico prediction of promoter elements.

Table 2.

Alignment of 36 A. fumigatus CBC:HapX sites (40 nt N5-CCAAT-N30) present in the promoter regions of 33 HapX ChIP-seq positive genes

|

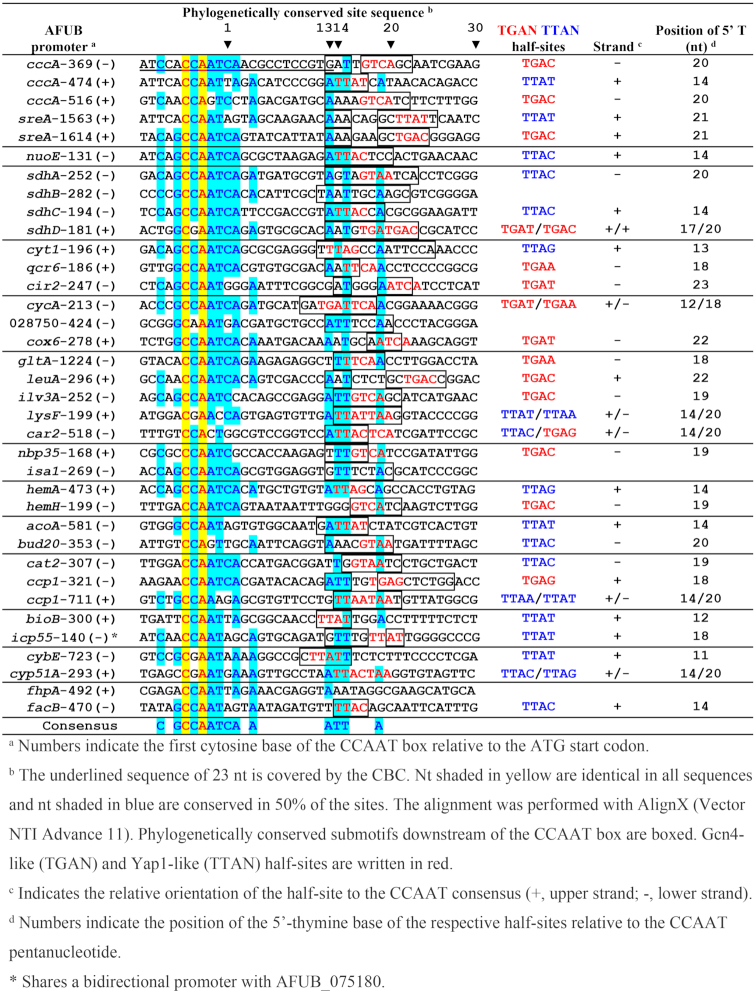

CBC- and HapX-binding sites are arranged with a preferred spacing in phylogenetically conserved CBC:HapX target sites

To further characterize the CBC:HapX recognition motifs, we aligned the phylogenetically conserved A. fumigatus sites (Table 1) plus the two binding sites identified by ChIP-seq from the hemA and fhpA promoter regions according to the position of their CCAAT-box incorporating 5 nt upstream and 30 nt downstream (Table 2). This alignment unequivocally reveals the CCAAT consensus binding sequence of the CBC, being invariant for only the first (C) and the third (A) nt position. Consistent with our ChIP-seq results, a 5′-RWT-3′ motif located exactly 12 bp downstream of the CCAAT consensus motif became apparent by MEME analysis of the 36 sequences from Table 2 (Figure 4A). Apart from this A/T-rich trinucleotide, the phylogenetically conserved submotifs located downstream of the CCAAT box (boxed in Table 2) display no obvious similarity with respect to their spacing and nucleotide sequence.

Figure 4.

(A) MEME analysis of 36 A. fumigatus CBC:HapX sites identified an A/T-rich trinucleotide (5′-RWT-3′) located 12 bp downstream of the CBC binding site. (B) The sequence logo of Yap1-like (TTAN) and Gcn4-like half-sites (TGAN) found in the 3′-submotifs of 32 CBC:HapX sites was generated by WebLogo (54). The distance between the CCAAT box and HapX 5′-T(T/G)AN-3′ half-site consensus motifs shows a remarkable variation (C), whereas their DNA strand orientation tends to be distance specific with preferred positions at 14(+) and 20(−) nt downstream of the CBC consensus motif (D).

HapX shares the basic region aa signature sequence NxxAQxxFR of the fungal-specific Yap1/Pap1 bZIP transcription factor subfamily for DNA recognition (50) and several genome-wide ChIP-based studies on the DNA recognition of Yap-like and Gcn4-like bZIPs in S. cerevisiae revealed that fungal specific Yap bZIPs bind overlapping (5′-TTACTAA-3′) or adjacent palindromic (5′-TTACGTAA-3′) TTAC half-sites (51,52), whereas Gcn4 prefers overlapping TGAC half-sites, i.e. 5′-TGACTCA-3′ (53). The three DNA loci previously shown to be bound by the CBC and HapX contained either overlapping Yap1-like half-sites (5′-TTACTAA-3′, A. fumigatus cyp51A) or single Gcn4-like half-sites present in A. nidulans cycA (5′-TGAT-3′) and A. fumigatus cccA (5′-TGAC-3′). Therefore, we examined the 3′-submotifs that are listed in Table 2 for the presence of both types of half-sites and found that 32 of the 36 CBC:HapX sites contained Yap1-like (TTAN) and/or Gcn4-like half-sites (TGAN) in the 3′-submotifs. Overall, we identified 12 single TGAN and 14 single TTAN half-sites as well as six overlapping half-sites, the latter being either overlapping Yap1-like half-sites (lysF, cccp1-711 and cyp51A), overlapping Gcn4-like half-sites (cycA and sdhD) or one overlapping hybrid of both half-site types (car2).

An alignment of the 26 single half-sites plus three additional nt at their 3′-end and the 6 overlapping 7 nt sequences revealed the sequence logo 5′-T(T/G)AN-3′ as an additional HapX consensus binding site (Figure 4B). The individual positions of the 5′-thymine base of the respective half-sites relative to the CCAAT consensus motif displayed a remarkable variance from 11 to 23 nt. However, a strong preference for Yap1-like TTAN half-sites at a position of 14 nt downstream of the CCAAT motif was observed (Figure 4C), a position that corresponds to the first nt after the 3′-end of the DNA sequence that is covered by the CBC (30). Interestingly, the first and second thymine of these TTAN half-sites are part of the 5′-RWT-3′ submotifs discovered by ChIP-seq analysis. Furthermore, irrespective of the half-site type, half-sites up to this position are preferably located on the same (+) strand, defined by the presence of the CCAAT pentanucleotide, whereas half-sites with a distance larger than 13 nt are rather located at the opposite (−) strand with an accumulation at a position of 20 nt downstream of the CCAAT motif (Figure 4D). This apparent randomness of the spatial arrangement of CBC- and putative HapX-binding sites in the individual promoters, as well as the small size (4 nt) of the HapX half-site consensus motif provide a logical explanation for the failure to discover a common CBC:HapX motif (except the CCAAT box and the 5′-RWT-3′ motif) by CSP-MEME analysis of promoters co-regulated by HapX and the CBC. Nonetheless, the enrichment of oppositely oriented half-sites at positions of 14(+) as well as 20(−) nt downstream of the CCAAT motif suggests that the bZIP domain of HapX preferentially targets a 7 bp DNA stretch that is located immediately next to 3′-end of the CBC-covered DNA sequence.

Taken together, these analyses indicate a tripartite motif for recognition by the CBC:HapX complex comprising of the CCAAT consensus motif recognized by the CBC, and two further motifs recognized by HapX, a proximal 5′-RWT-3′ motif located 12 bp downstream of the CCAAT box and a further 3′-distal 5′-T(T/G)AN-3′ motif with variable spacing.

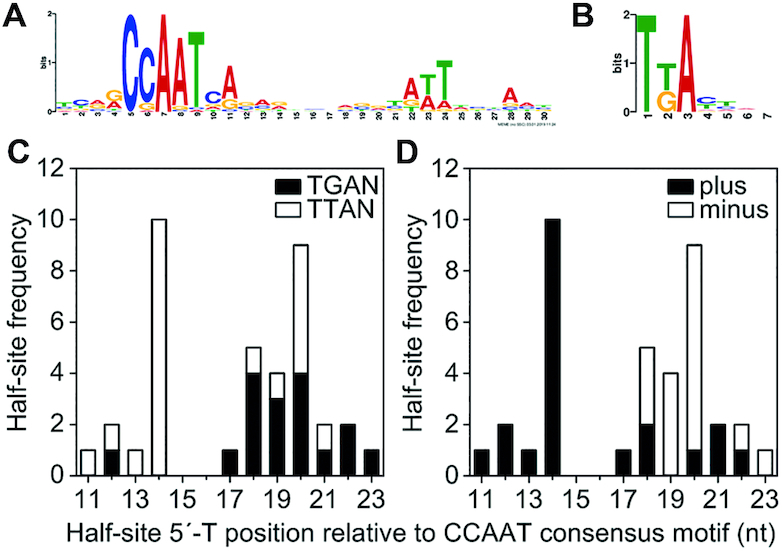

SPR analysis reveals multiple specificities for CBC:HapX binding to evolutionary conserved promoter sites of HapX regulon genes

Previously, we established surface plasmon resonance (SPR) co-injection assays to characterize the combinatorial recognition of bipartite DNA motifs by the CBC:HapX complex (3,13,29). To analyze whether all of the identified 36 A. fumigatus CBC:HapX sites are cooperatively recognized by HapX and the CBC, we performed these assays and quantified the individual DNA-binding affinities of the CBC and HapX for each of the sites (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S7). Kinetic binding responses of the CBC fitted with high affinities, typically below 10 nM. CBC binding affinities that exceeded this threshold level are clearly associated with nucleotide substitutions in the 5′-CCAATVR-3′ consensus sequence, i.e. 5′-CCACTGG-3′ (car2), 5′-CCAAAGA-3′ (ccp1-711), 5′-CCAGTCC-3′ (cccA-516), 5′-CGAATGA-3′ (cyp51A) and 5′-CGAACCA-3′ (lysF). In contrast to high- or moderate-affinity CBC binding, the majority of the sites displayed negligible or low-affinity binding by HapX without the CBC (Supplementary Table S7). However, as measured by SPR co-injection assays, cooperative CBC:HapX binding analysis revealed apparent dissociation constant (KD) values for binding of HapX to preformed CBC/DNA in the nanomolar (0.4 nM, cccA-369) up to micromolar (3.6 μM, cox6) range (Figure 5). These measurements confirm our previous results that a DNA:CBC complex is required for HapX recruitment to CBC:HapX sites in this assay. Interestingly, there is no straightforward correlation between the CBC and CBC:HapX affinities. We observed three modes of CBC:HapX binding site recognition: (i) both high CBC and CBC:HapX affinity (e.g. cccA, cat2), (ii) moderate CBC affinity and high CBC:HapX affinity (e.g. car2, cyp51A) and (iii) high CBC affinity combined with low CBC:HapX affinity (e.g. facB, cox6).

Figure 5.

Comparative SPR analysis of CBC-binding to DNA and HapX-binding to preformed CBC:DNA complexes on 36 individual A. fumigatus HapX regulon promoter sites. (A) Sites are ranked from the top to the bottom according to their apparent HapX binding affinity to CBC-bound DNA (red bars); the CBC affinity to the sites is shown as black bars. Black and white dots indicate the position of the 5′-thymine base of Gcn4-like (5′-TGAN-3′) and Yap1-like (5′-TTAN-3′) half-sites relative to the CCAAT consensus motif as well as their DNA strand orientation (black lines). Blue and light blue colored boxes indicate two 7 bp spanning DNA regions which contain 5′-T(T/G)AN-3′ half-sites at their 5′- or 3′-border. (B) The in vitro HapX DNA-binding affinity correlates with the in vivoVenusHapX ChIP-seq peak fold enrichment on 33 A. fumigatus CBC:HapX promoter sites.

The recently identified and evolutionary conserved bipartite A. fumigatus cccA promoter site at position −369 (3), which was reanalyzed in this study, clearly represents the highest affinity CBC:HapX binding site in our quantitative SPR DNA-footprint analysis. Despite the fact that this locus contains the Gcn4-like half-site 5′-TGAC-3′, we were unable to identify a general HapX preference for 5′-TGAN-3′ motifs over 5′-TTAN-3′ Yap1-like half sites. Consistent with the enrichment of oppositely oriented half-sites at positions of 14 and 20 nt downstream of the CCAAT motif, high-affinity CBC:HapX DNA recognition (KD below 100 nM) was preferentially measured on DNA sites which contained single or overlapping T(T/G)AN half-sites at these positions (e.g. cccA, cat2, sdhC, lysF, cyp51A, hemA, car2, ccp1) (Figure 5A). However, high-affinity binding of CBC:HapX to the leuA and sreA promoter motifs cannot be explained with this conclusion. The 3′-half-sites present in these bipartite motifs are located at positions of 21 and 22 nt downstream of the CCAAT motif. This finding supports the view that the HapX 5′-T(T/G)AN-3′ recognition site is shifted at this loci by 7 and 8 bp to the 3′-end, which corresponds to around a half helical DNA turn (Figure 5A). As a consequence, the phylogenetically conserved A/T-rich trinucleotides located at position 13 in the leuA and sreA promoter sites (Table 2) are not part of the respective 5′-TGAN-3′ half-site and thus, the tripartite structure of these conserved CBC:HapX DNA-binding motifs becomes evident (see Table 1).

Next, we investigated if the in vitro HapX DNA-binding strength correlates with our quantitative HapX ChIP-seq data set. Therefore, SPR measured HapX binding affinities were plotted against the VenusHapX ChIP-seq peak fold enrichment in –Fe and +Fe conditions on the respective A. fumigatus promoter sites (Figure 5B). Spearman's rank-order analysis revealed a significant correlation (P <0.01) between both datasets, demonstrating that the in vitro SPR affinity data are biologically meaningful.

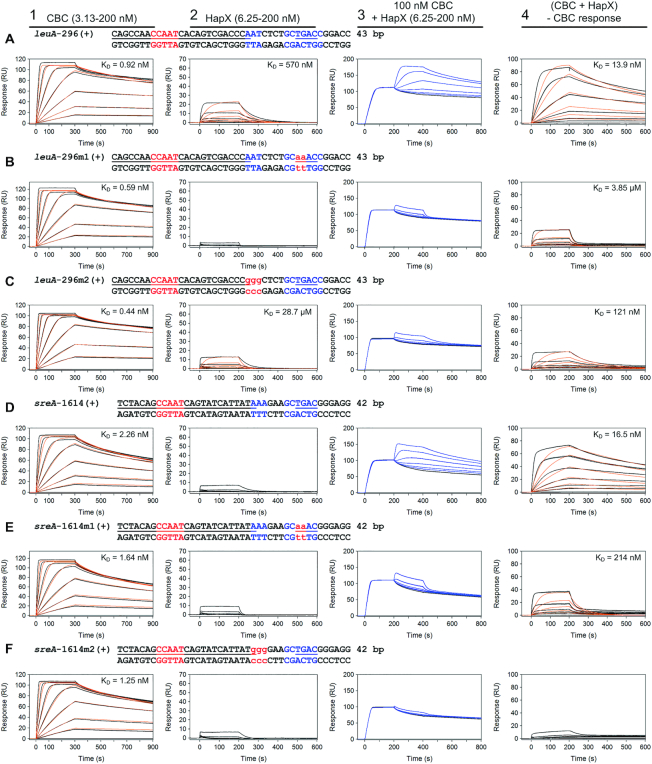

A/T-rich submotifs at the 3′-border of the CBC binding site promote high-affinity binding of HapX in vitro and cccA promoter activity in vivo

To determine the individual contribution of both the 5′-RWT-3′ and bZIP half-site submotifs to CBC:HapX binding site recognition, three types of mutations were introduced in four exemplarily selected promoter sites. First, substitutions of two nts were introduced within the 5′-TGAC-3′ half-sites of leuA, sreA-1614 as well as cccA-369. These mutations perturbed (leuA, sreA-1614) (Figure 6B and E) or completely abolished cooperative high-affinity HapX binding (cccA-369) (Figure 7B and C), which confirms HapX binding site specificity for the respective Gcn4-like half-sites. Second, the 5′-RWT-3′ submotifs located in these promoter regions at the 3′-border of the CBC-covered sequence were exchanged for a GGG trinucleotide. Consistent with our hypothesis that this site is also required for binding, these mutations resulted in a strong decrease of HapX binding affinity (leuA, Figure 6C) or the complete loss of cooperative CBC:HapX binding on the sreA-1614 and cccA-369 promoter binding sites (Figures 6F and 7D). Third, we selected the low affinity CBC:HapX binding hemH promoter site (KD = 121 nM) that contains a GGG trinucleotide at position 13 and exchanged it for the 5′-RWT-3′ motif sequence 5′-ATT-3′. Strikingly, this exchange converted the hemH motif into a high-affinity HapX target site by increasing the apparent HapX affinity to the preformed CBC:DNA complex by a factor of 70 (KD = 1.71 nM), which is comparable to that of the tightest binding site located in the cccA promoter (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 6.

HapX-binding depends in vitro on both the Gcn4-like half sites and A/T-rich submotifs within the bipartite CBC:HapX consensus sites as shown by SPR analysis. SPR analyses included binding of the CBC to DNA (panel 1), HapX to DNA (panel 2) and HapX to preformed CBC:DNA complexes (panel 3). The SPR sensorgrams are shown from sensor-immobilized duplexes covering evolutionary conserved bipartite CBC:HapX binding sites from A. fumigatus leuA and sreA promoters (A and D) as well as duplexes carrying mutations within their 3′ Gcn4-like half-site (B and E) or A/T-rich submotif (C and F). Nt underlined in black are covered by the CBC and nt marked in blue represent the A. fumigatus conserved submotifs. Gcn4-like half-sites are underlined in blue. Substituted nt relative to the wild type sequence are written in red and shown in lower case. Binding responses of the indicated CBC or HapX concentrations injected in duplicate (black lines) are shown overlaid with the best fit derived from a 1:1 interaction model including a mass transport term (red lines). Binding responses of CBC:DNA:HapX ternary complex formation (panel 3, blue lines) were obtained by concentration dependent co-injection of HapX on preformed binary CBC:DNA complexes after 200 seconds within the steady-state phase. Sensorgrams in panel 4 depict the association/dissociation responses of HapX on preformed CBC:DNA and were generated by CBC response subtraction (co-injection of buffer) from HapX co-injection responses.

In vivo impacts of the 5′-RWT-3′ and bZIP half-site submotifs on promoter activity were evaluated by using lacZ reporter gene analysis of the cccA promoter in A. fumigatus wild type and ΔhapX strains (Figure 7E and F), including mutations of the CBC:HapX cccA promoter motif 1 (Table 1) with the same nt substitutions that were characterized by SPR analysis (Figure 7B and D). As expected, cultivation of these strains under iron starvation failed to activate the cccA promoter, whereas a strong activation was observed after a short-term shift from iron starvation to iron sufficiency (Figure 7F). Mutation of the 5′-TGAC-3′ half-site of cccA-369 (strain PcccAm1-lacZ) decreased activity to 54.6 ± 5.7% of that monitored for the native promoter. Interestingly, modification of the A/T-rich submotif (strain PcccAm3-lacZ) as well as the combination of both mutations (strain PcccAm13-lacZ) reduced promoter activity to the same level, indicating (i) that, consistent with the SPR results (Figure 7A–D), both submotifs are equally important for cccA activation, and (ii) that the residual activity in the mutant strains is mediated most likely by the two remaining CBC:HapX binding sites located upstream in the cccA promoter. The complete loss of the native cccA promoter activity in the hapX deletion strain confirmed HapX-dependence of cccA promoter activation.

Taken together, the combination of our in vivo, in silico and in vitro approaches revealed three criteria that define a high-affinity CBC:HapX DNA recognition motif: (i) a CCAAT box with the consensus sequence 5′-CSAAT-3′ recognized by the CBC, (ii) a 5′-RWT-3′ signature recognized by HapX located exactly 12 bp downstream of the CCAAT box, which is the 3′-border of the CBC-covered sequence, and (iii) single or overlapping 5′-T(T/G)AN half-sites recognized by HapX located with a remarkable variance of 11–23 nt 3′-downstream of the CCAAT motif, but with a preference for 14 nt on the same strand as the CCAAT box and 20 nt on the opposite strand relative to the CCAAT box.

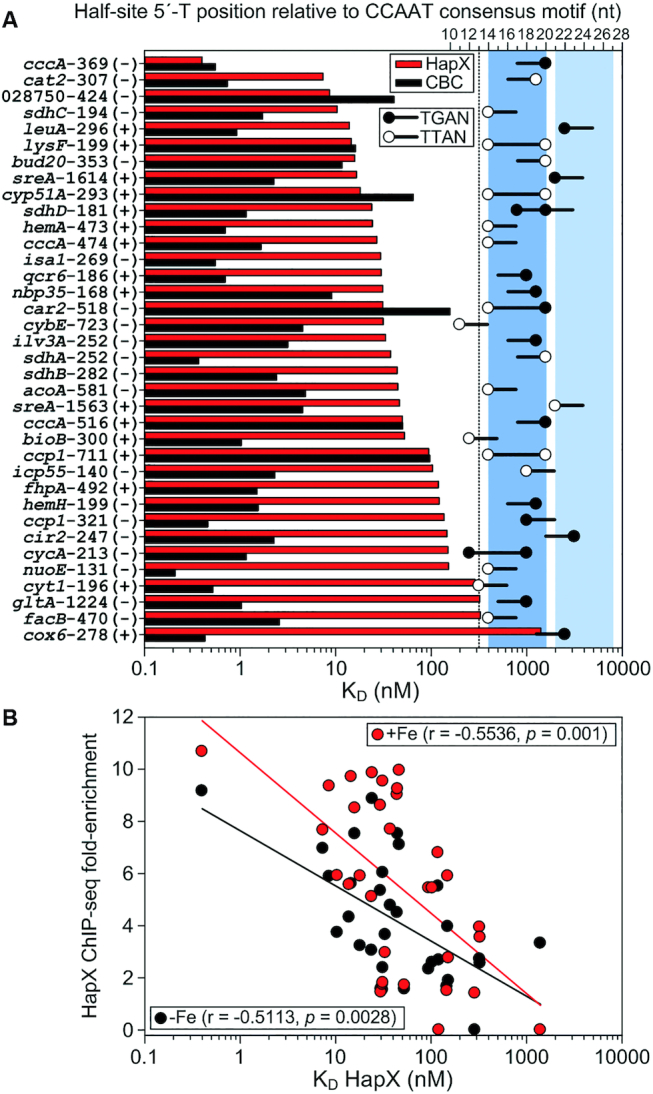

Mutations within the DNA-BD or lack of the CBC-BD of HapX abolish CBC:HapX interaction with the cccA promoter motif in vitro

Next, we investigated the role of the HapX CBC- and DNA-binding domains in vitro. We produced a DNA-BDm polypeptide in Escherichia coli that corresponds to residues 24–158 of HapX but with four aa substitutions (N65D, Q69G, F72S and R73E). Mutations at these positions were selected since they mediate nucleotide specific protein-DNA contacts in the complex between the orthologous bZIP domain of the S. pombe oxidative stress regulator Pap1 and its DNA-binding motif (17). Furthermore, similar aa substitutions in the bZIP region of the C. albicans HapX ortholog Hap43 failed to fully complement the growth defect of a hap43 deletion strain during iron starvation (10). Additionally, a HapX bZIP peptide lacking the CBC-BD was produced (aa 59–158, HapX ΔCBC-BD) and analyzed by our SPR co-injection assay.

The HapX wild type polypeptide bound with high affinity (0.4 nM) to the CBC:cccA complex but not the CBC-free DNA (Figure 7A, compare panels 2 and 4). In contrast, both HapX mutant peptides lost their capability for cooperative high-affinity binding to the CBC:cccA DNA complex (Figure 8A and B). Interestingly, the HapX ΔCBC-BD protein displayed a 3-fold increased binding affinity in the absence of the CBC (Figure 8B, panel 1) when compared to the wild type protein (Figure 7A, panel 2). In summary, we show that combinatorial high-affinity CBC:HapX DNA recognition requires both the CBC-BD and DNA-BD of HapX. This binding mode provides an explanation for distinguishing specific HapX:CBC and general CBC target genes, but does not fully reveal the selectivity of HapX for its DNA-binding motif relative to other A. fumigatus bZIP transcription factors.

Figure 8.

Loss of cooperative CBC:HapX binding is elicited by HapX DNA-BD mutations, deletion or modifications of the CBC-BD. SPR sensorgrams of HapX (A, B), HapX/CgYap5 hybrids (C, D) or Yap1 (E, F) binding to DNA (panel 1), and bZIP peptides to preformed CBC:DNA complexes (panel 2) are shown. Aa residues that differ from the native HapX sequence are marked in gray. Nt underlined in black are covered by the CBC and nt marked in blue represent the A. fumigatus HapX DNA-binding site in the cyp51A promoter. The overlapping Yap1-like half-sites in the cyp51A promoter are underlined in blue. Binding responses of the indicated bZIP concentrations injected in duplicate (black lines) are shown overlaid with the best fit derived from a 1:1 interaction model including a mass transport term (red lines). Binding responses of CBC:DNA:bZIP ternary complex formation (panel 2, blue lines) were obtained by concentration dependent co-injection of bZIPs on preformed binary CBC:DNA complexes. Sensorgrams in panel 3 depict the association/dissociation responses of bZIPs on preformed CBC:DNA and were generated by CBC response subtraction (co-injection of buffer) from bZIP co-injection responses. (G) Amino acid sequence comparison of the HapX CBC-BD and DNA-BD spanning region with A. fumigatus bZIPs carrying the basic region signature sequence of the fungal Yap1/Pap1 subfamily. Sequences are aligned according to similarity of the basic regions. The HapX CBC-BD and a rudimentary CBC-BD in the N-terminal region of Yap1 are underlined.

The Hap4-like CBC-BD domain of Yap5 is not sufficient for cooperative CBC:HapX DNA binding

Because C. glabrata Yap5 (CgYap5) contains a degenerated Hap4-like domain that corresponds to the N-terminal part of the HapX CBC-BD (26), we prepared two HapX/Yap5 bZIP hybrid proteins by domain swapping and analyzed their CBC:DNA interaction by SPR in vitro. Substitution of the entire 16 aa CBC-BD of HapX by the corresponding aa sequence of CgYap5 (32ISKKWKLPPLRPKGSH47) diminished cooperative binding of the resulting HapXCgY5 hybrid to the preformed CBC:cccA DNA complex to a level which was similar to that observed for the HapX bZIP peptide lacking the CBC-BD (Figure 8C). Remarkably, the HapXCgY5c hybrid in which only the C-terminal 47KPGRK51 stretch was exchanged by the corresponding aa sequence from CgYap5 (43PKGSH47), also failed to bind with high affinity to the CBC:cccA complex (Figure 8D). Likewise, all four HapX mutant proteins (DNA-BDm, ΔCBC-BD, HapXCgY5 and HapXCgY5c) failed to bind a CBC:cyp51A DNA complex that contained the Yap response element (YRE) 5′-TTACTAA-3′ 13 bp downstream of the CBC binding site, which is supposed to be the preferred target DNA motif of CgYap5 (26) (Supplementary Figure S5). Therefore, it appears that HapX requires its entire CBC-BD and particularly the C-terminal 47KPGRK51 pentapeptide for simultaneous CBC:DNA binding site recognition. This observation is in contrast to the obvious DNA target recognition mode of CgYap5, which solely depends on its truncated Hap4-like domain (26).

The stress-responsive bZIP type transcription factor Yap1 contains a rudimentary CBC-BD but is unable to recognize CBC:HapX binding sites cooperatively

A search in the FungiDB database (55) revealed that the A. fumigatus genome encodes at least 20 bZIPs and a blastp database search (41) using the basic region aa sequence of HapX as query identified five bZIP transcription factors sharing the Yap1/Pap1 signature, including Yap1 (56), RsmA (57), MeaB (58), and two additional uncharacterized bZIP proteins. Based on the amino acid sequence alignment of A. fumigatus Yap1-like bZIPs, we were interested if the bZIP domain of Yap1, the Pap1 ortholog in A. fumigatus, is able to recognize the cccA promoter HapX submotif 5′-GCTGAC-3′ (a single Gcn4-like half-site) on its own or by combinatorial CBC binding. This experiment was prompted by the observations that (i) HapX and Yap1 share nearly identical basic region DNA-BDs and (ii) Yap1 contains a rudimentary CBC-BD (149KPGRK153) that matches exactly the C-terminal part of the HapX Hap4-like domain (Figure 8G).

Yap1 (aa 135-234) showed relatively high affinity binding (KD of 50 nM) to a naked DNA duplex matching the Gcn4-like half-site 5′-TGAC-3′ and flanking sequences in the cccA promoter (Figure 8E, panel 1). This was 19-fold higher compared to the binding affinity of HapX (KD of 951 nM) at the same DNA duplex (Figure 7A, panel 2). However, combinatorial high-affinity CBC:Yap1 binding was not observed by co-injection of Yap1 on CBC-bound DNA (Figure 8E, panels 2 and 3). Moreover, pre-injection of the tightly bound CBC decreased Yap1 affinity 2.5-fold, indicating the opposite was happening, i.e. competitive binding due to steric hindrance.

Additionally, we performed a CBC:Yap1:DNA interaction analysis with a cyp51A DNA duplex carrying the YRE 5′-TTACTAA-3′ (Figure 8F, panels 2 and 3). Again, Yap1 did not bind cooperatively with the CBC to this CBC:HapX binding site. However, in contrast to Yap1-binding of the cccA site, its affinity here is unaffected by pre-injection of the weakly bound CBC (KD of 64.5 nM). As expected, Yap1 bound with a 3.8-fold higher affinity (13 nM) to its preferred consensus site in comparison to the non-cognate Gcn4-like half-site present in the cccA promoter (Figure 8F, panel 1). These results are in line with previous reports, which demonstrated that bZIP transcription factors possess the versatility to bind various cognate and non-cognate sequences with varying affinities (59,60). Taken together, these results revealed the non-functionality of the rudimentary Yap1 CBC-BD and the importance of both the N- and C-terminal parts of the HapX CBC-BD for simultaneous CBC and DNA recognition.

The DNA and CBC binding domains of A. fumigatus HapX are crucial for adaptation to iron starvation and iron excess

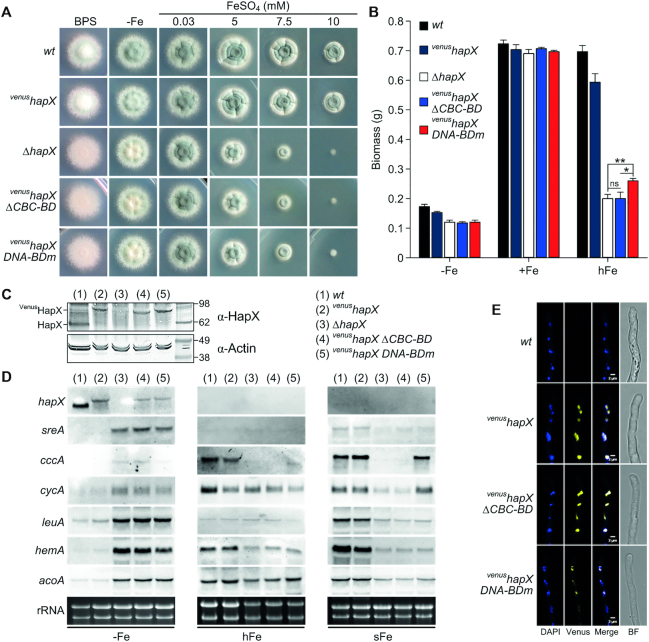

To evaluate the role of the basic region DNA-binding domain (DNA-BD) as well as the Hap4-like CBC-BD of HapX on its global iron regulatory function in vivo, we generated two A. fumigatus hapX mutant strains. Both strains expressed the coding region of the yellow fluorescent protein variant Venus fused to the 5′-end of the HapX open reading frame to allow detection of its subcellular localization. In the first mutant strain, 16 aa residues (36–51) comprising the CBC-BD of HapX were deleted (venushapX ΔCBC-BD). In the second mutant strain (venushapX DNA-BDm), the same four aa residue substitutions (N65D, Q69G, F72S and R73E) present in the recombinant HapX DNA-BDm polypeptide were performed within the HapX basic region. Both venushapX ΔCBC-BD and venushapX DNA-BDm plasmid constructs were inserted at the original hapX locus in single-copy under the control of the endogenous promoter. Phenotypes of the mutants were compared to the corresponding parental A. fumigatus wild type strain AfS77 and a strain that produces an N-terminally Venus-tagged HapX protein (venushapX) (Figure 9A and B). Notably, Western blot analysis demonstrated that the different modifications of HapX (Venus-tagging as well as mutations) did not change its cellular protein level (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

HapX DNA-binding and CBC:HapX interaction is essential for its function during iron starvation and overload. (A) Growth pattern of A. fumigatus wild type (wt, AfS77), venushapX, ΔhapX and venushapX strains expressing hapX alleles with either a deletion of the HapX CBC-BD (venushapX ΔCBC-BD) or aa substitutions within the HapX DNA-BD (venushapX DNA-BDm) on solid minimal medium at 37°C for 48 h. (B) Production of biomass during iron starvation (−Fe), iron sufficiency (0.03 mM FeSO4, +Fe) and iron excess (5 mM FeSO4, hFe) after liquid growth at 37°C for 24 h. Biomass production of the mutant strains was significantly different compared to wt and venushapX during −Fe and hFe, but not +Fe (P <0.001). (C) Western blot analysis of wild type and mutant HapX protein levels from strains grown for 24 h under iron deficiency. Actin was used as loading control. (D) Northern blot analyses were performed after liquid growth under iron starvation (−Fe) and high-iron availability (5 mM FeSO4, hFe) at 37°C for 20 h or from mycelia shifted for 30 min from −Fe to iron sufficiency (0.03 mM FeSO4, sFe). (E) Nuclear localization of Venus-tagged wild type HapX and HapX mutant proteins in iron limitation conditions.

Growth analyses under iron limitation as well as high-iron conditions revealed that lack of the HapX CBC-BD as well as aa substitutions within the DNA-BD phenocopied HapX-deficiency on solid and in liquid media (Figure 9A). The addition of the ferrous iron-specific chelator BPS, which inhibits reductive iron assimilation and induces iron-limitation, decreased sporulation on agar plates of both mutants to the same degree as the full hapX deletion. Moreover, the radial growth of all hapX mutants was drastically reduced under high-iron conditions (Figure 9A). In agreement with the in vitro data, deletion of the HapX CBC-BD or mutation of the DNA-BD decreased biomass production in liquid cultures during iron limitation and excess (Figure 9B). Interestingly, lack of the CBC-BD had a significant higher impact on biomass production during iron excess (P <0.05) than mutations within the DNA-BD. As expected, no growth defects were obvious during iron sufficiency.

Taken together, these results show that both the CBC- and DNA-BDs are essential for HapX function during iron limitation and high-iron conditions. Moreover, these data indicate that the CBC is involved in adaptation to iron starvation in A. fumigatus. Inactivation of the CBC by deletion of the gene encoding of the CBC subunit HapC (strain ΔhapC) resulted in a general slow growth effect as reported previously for A. nidulans (5) (Supplementary Figure S6A). In agreement with its function in iron homeostasis, HapC-deficiency decreased growth and blocked sporulation during iron starvation and blocked growth during high iron conditions in plate cultures (Supplementary Figure S6A). Deficiency in both HapX and HapC (strain ΔhapXΔhapC) phenocopied HapC-deficiency with respect to growth on plates (Supplementary Figure S6A) and in liquid cultures (Supplementary Figure S6B) under conditions of different iron availability as well as with respect to siderophore production (Supplementary Figure S6B). These data demonstrate that HapC-deficiency is epistatic to HapX-deficiency and, consistent with our DNA binding observations, indicate that HapX lacks CBC-independent functions.

We next examined the role of the HapX CBC and DNA-BDs on expression of HapX target genes. Specifically, we evaluated transcript levels for the heme-containing respiration enzyme CycA (cytochrome c), the iron-sulfur cluster enzymes AcoA (aconitase) and LeuA (α-isopropylmalate isomerase), involved in TCA cycle and leucine biosynthesis, respectively, as well as the heme biosynthesis protein HemA (5-aminolevulinic acid synthase), which we have previously shown to be HapX targets (Supplementary Table S5) and (4). Similar to the hapX null mutant (ΔhapX), genes coding for these iron-dependent enzymes are derepressed in the venushapX ΔCBC-BD and venushapX DNA-BDm mutants under iron starvation (Figure 9D). Transcription of the HapX target sreA was also derepressed in all three mutants (Figure 9D). These results indicate that HapX:CBC interaction and HapX DNA-binding are equally important for gene repression during low-iron conditions. Furthermore, deletion of HapX CBC-BD or mutation of its DNA-BD impaired the HapX-mediated transcriptional activation of the vacuolar iron importer-encoding cccA and heme-biosynthetic hemA under high-iron conditions (Figure 9D). In contrast to ΔhapX and venushapX ΔCBC-BD, however, the venushapX DNA-BDm mutant displayed a slightly increased cccA transcript level, which is consistent with its minor but significant growth advantage during iron excess (Figure 9B). In contrast to cccA and hemA, HapX inactivation as well as mutation of the HapX CBC-BD or the DNA-BD had only a minor impact on expression of cycA and acoA (Figure 9D). This might be explained by the fact that expression of cccA and hemA is exclusively or mainly regulated by the CBC:HapX complex, while cycA and acoA are subject to control by other regulatory circuits, which mask or override CBC:HapX complex-mediated regulation during steady-state high-iron conditions. As expected, no hapX transcript was detected during iron excess (3).

Besides its main regulatory function during iron limitation and excess, HapX seems to be involved in general upregulation of iron-dependent processes during short-term iron access (3). This was confirmed here, where both the inactivation of HapX or the deletion of the CBC-BD blocked transcriptional activation of the iron-consuming pathway genes and sreA during a 30-min shift from iron-deficient to iron-replete conditions (Figure 9D). In parallel, mutation of the HapX DNA-BD had the same effect with exception of two genes: cccA and cycA. These data suggest that requirement for the HapX DNA-BD is promoter-specific and dispensable for cccA and cycA activation during short-term adaptation to high-iron conditions.

It was shown recently by epifluorescence microscopy that HapX is localized in the nucleus during iron starvation (3). We were concerned that the modifications that we made to HapX would alter its ability to be transported to the nucleus under these conditions especially as the putative Aspergillus oryzae HapX nuclear localization signal (NLS) overlaps the basic region of the bZIP domain (18) (Figure 1). Epifluorescence microscopy of mycelia grown in iron limitation demonstrated that neither deletion of the HapX CBC-BD nor mutations of the HapX DNA-BD affect nuclear localization, which was visualized by DAPI co-staining (Figure 9E). These data confirm that cellular mislocalization of HapX is not responsible for the growth and gene regulation defects we observed for CBC-BD and DNA-BD HapX mutant proteins.

HapX interacts with the CBC to activate siderophore mediated iron uptake during iron limitation

A. fumigatus produces two extracellular siderophores, fusarinine C (FsC) and triacetylfusarinine C (TAFC), to capture and acquire iron from the environment (61). Previously, HapX was shown to be involved in the activation of siderophore biosynthesis during iron starvation, i.e. HapX-deficiency resulted in significantly decreased production of TAFC but not FsC (4). However, so far it was unclear if the HapX:CBC interaction is required for this regulatory circuit.

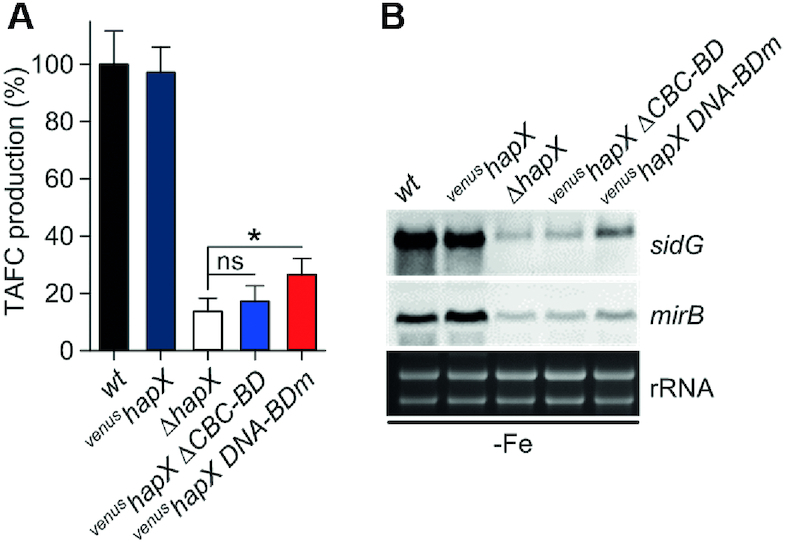

In the venushapX ΔCBC-BD strain, production of TAFC was drastically reduced to 17.2 ± 5.4% of that observed for the wt (Figure 10A). This was comparable to complete HapX inactivation (ΔhapX strain), in which TAFC production was reduced to 13.6 ± 4.6% of the wt level. We also confirmed that HapX-DNA binding was required for TAFC production (decreased to 26.5 ± 5.6% in venushapX DNA-BDm) but to a significant lesser extent (P <0.05) compared to TAFC production in ΔhapX (Figure 10A). On the transcriptional level, deletion of the HapX CBC-BD resulted in repression of genes involved in TAFC synthesis (sidG) and transport (mirB) (Figure 10B) to a level similar to that seen in ΔhapX. Mutation of the HapX DNA-BD also resulted in decreased sidG and mirB transcription. However, this decrease was less pronounced when compared to ΔhapX and venushapX ΔCBC-BD (Figure 10B), which is in agreement with the higher TAFC level determined in the supernatant of strain venushapX DNA-BDm (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

Production of TAFC is impaired by HapX-deficiency as well as deletion of the HapX CBC-BD or mutations within the HapX DNA-BD in vivo. (A) TAFC production of the mutant strains was significantly reduced compared to wt and venushapX under iron starvation (P <0.001). (B) HapX-CBC as well as HapX-DNA interaction is crucial for activation of genes that promote TAFC biosynthesis in A. fumigatus.

In summary, these data show for the first time that HapX:CBC protein-protein interaction is crucial for activation of TAFC biosynthesis during iron starvation. Further, HapX binding to DNA via its basic region DNA-BD is required, but had a lower impact on TAFC production than the deletion of the HapX CBC-BD. Nevertheless, HapX requires both CBC- and DNA-binding to fully activate TAFC production.

DISCUSSION

For adaptation to iron availability, the CBC:HapX complex regulates numerous cellular processes localized in different cellular compartments, which is reflected by the target genes analyzed in detail in this study (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S5). Of the encoded proteins, 21 are mitochondrial, 6 cytoplasmic, 2 nuclear, 1 both cytoplasmic and nuclear, 2 endoplasmatic reticular, 1 vacuolar membranous. There is a clear emphasis on mitochondria as well as on iron metabolism with direct iron-dependence (heme or iron sulfur clusters) or involvement in handling or regulation of the iron-related processes.

In this work, we characterized the genome-wide DNA-binding patterns of CBC:HapX in the opportunistic fungal pathogen A. fumigatus by using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) combined with in vitro analysis of protein-DNA interaction (surface plasmon resonance) and in silico phylogenetic comparison taking advantage of 20 genomes from Aspergillus species. Based on previous studies on the transcriptional cooperativity of the CBC and the iron-sensing bZIP transcription factor HapX in regulation of fungal iron homeostasis, we anticipated to identify a common joint pattern of bipartite cis-regulatory promoter elements, which contain both a pentameric CCAAT-box and at least either a Yap1-like or Gcn4-like bZIP half-site. Further, a uniform spacing of these sites should enable efficient protein-protein contacts between the CBC subunit HapE and the Hap4-like CBC-BD of HapX. Intriguingly, this was not the case. Instead, our studies revealed that the CBC and HapX display an extremely flexible synergetic DNA recognition. Our in vivo ChIP-seq approach identified a minimal common CBC:HapX consensus DNA-binding motif 5′-CSAATN12RWT-3′ with a bipartite structure (Figure 2D, E), but this motif alone was not sufficient for tight and specific interaction with the CBC and HapX. High-affinity binding requires an additional 5′-TKAN-3′ bZIP half-site positioned 11–23 bp downstream of the CSAAT motif, which occasionally overlaps the 5′-RWT-3′ submotif of the bipartite site (Figures 6 and 7). These results are in agreement with other large-scale studies of transcription factor DNA binding preferences, which have shown that recognition of multiple motifs, including those with variable spacing and orientation of motif half-sites, is not uncommon (62). Moreover, we demonstrate that CBC:HapX DNA-binding displays remarkable promoter-specific cross-species conservation rather than HapX regulon intra-species conservation (Table 1). These data indicate that promoter-specificity evolved previous to speciation within the Aspergillus genus. The reason for promoter specificity remains elusive but might be explained by the requirement for promoter-specific binding affinity or interference with binding sites for other transcription factors.

Regardless of this high flexibility, which results in multiple CBC:HapX binding site specificities and affinities (Table 2, Figure 5), our results provide for the first time genome-wide information on promoter sites recognized by the CBC without HapX (∼2000) and by the CBC:HapX complex (around 100), respectively (Figure 2B, C). HapX recognition depends on targeting of in total three DNA elements. One CBC-binding site bound indirectly by protein-protein interaction with the CBC and two different DNA recognition sites bound by HapX directly.

The intriguing question, of course, is which of the HapX protein domains are involved in the recognition of the two non CCAAT-related HapX binding sites. To tackle this topic, we investigated the DNA-binding properties of HapX mutant proteins harboring loss-of-function mutations in their basic region DNA-BD or a deletion of the CBC-BD. Our in vitro SPR approaches revealed that both the Hap4-like CBC-BD as well as a functional basic region segment of the bZIP domain are indispensable for effective recognition of CBC bound target DNA sites (Figure 8A, B). In agreement, A. fumigatus strains expressing the same mutant hapX alleles failed to control their target genes during both iron limitation and iron excess (Figure 9D). Similar mutations in the C. albicans HapX ortholog Hap43 caused a severe growth defect during iron starvation (10,20). Interestingly, we observed subtle distinctions between both mutants in specific growth conditions. In all in vivo studies, i.e. growth assays, regulation of HapX target genes, and siderophore (TAFC) production, we observed that lack of the HapX CBC-BD fully phenocopied HapX-deficiency (Figures 9, 10). In comparison, the four aa substitutions within the bZIP DNA-BD had a slightly lesser impact on the growth inhibition in high iron conditions as well as on TAFC production during iron deficiency. Furthermore, these mutations did not affect expression of all CBC:HapX target genes in the same way: the mutations in the bZIP DNA-BD impaired upregulation in a short-term shift from iron starvation to iron sufficiency of sreA, leuA, hemA and acoA but not of cccA and cycA (Figure 9D). This promoter specificity might be based on the number of CBC:HapX complex binding sites in the promoters of the target genes, e.g. the cccA promoter contains three binding sites (Table 1, Figure 7E), which might increase the probability of enrichment of HapX at these sites independent of the bZIP DNA-BD. Alternatively this specificity may arise because of other contextual differences at promoter specific sites that lead to differential binding affinities of the CBC or HapX.