Abstract

Background

Preeclampsia refers to the new onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive woman. Pregnant women with preeclampsia are at an increased risk of adverse maternal, fetal and neonatal complications. The objective of the study is, therefore, to determine the maternal and perinatal outcome of preeclampsia without severity feature among women managed at a tertiary referral hospital in urban Ethiopia.

Methods

A hospital-based prospective observational study was conducted to evaluate the maternal and perinatal outcome of pregnant women who were on expectant management with the diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe feature at a referral hospital in urban Ethiopia from August 2018 to January 2019.

Results

There were a total of 5400 deliveries during the study period, among which 164 (3%) women were diagnosed with preeclampsia without severe features. Fifty-one (31.1%) patients with preeclampsia without severe features presented at a gestational age between 28 to 33 weeks plus six days, while 113 (68.9%) presented at a gestational age between 34 weeks to 36 weeks. Fifty-two (31.7%) women had maternal complication of which, 32 (19.5%) progressed to preeclampsia with severe feature Those patients with early onset of preeclampsia without severe feature were 5.22 and 25.9 times more likely to develop maternal and perinatal complication respectively compared to late-onset after 34 weeks with P-value of <0.0001, (95% CI 2.01–13.6) and <0.0001(95% CI 5.75–115.6) respectively.

Conclusion

In a setting where home-based self-care is poor expectant outpatient management of preeclampsia without severe features with a once per week visit is not adequate. It’s associated with an increased risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Our findings call for special consideration and close surveillance of those women with early-onset diseases.

Introduction

Preeclampsia is defined as a systemic syndrome characterized by the new onset of raised blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive woman [1, 2]. Globally preeclampsia complicates 2–8% of pregnancies and contributes to 10–15% maternal death [3]. It’s called preeclampsia without severity feature in the absence any of the following features: cerebral symptoms (like visual disturbance, headache), right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, serum transaminase concentration ≥ twice normal, systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg, and or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mm Hg on two occasions at least four hours apart, severe thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets/micro), Oliguria <500 mL in 24 hours and pulmonary edema [2, 4, 5].

Multiple observational studies reported a prevalence of preeclampsia in Ethiopia ranging from 4 to 12% and contribute to 15% maternal deaths [6–9]. In five year’s retrospective review of the perinatal outcome at three teaching hospitals in Ethiopia, preeclampsia contributed to perinatal mortality of 290/1000 total births [10].

The only curative treatment of preeclampsia is birth. However, in the case of preterm pregnancies, expectant management is advocated to increase the chance of fetal maturity, if the risk for the mother remains acceptable [11]. The Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At near Term (HYPITAT) which is a multicenter RCT comparing expectant management versus induction of labour in a woman with mild gestational hypertension or mild preeclampsia at 36 to 37 weeks of gestation has shown that routine induction was associated with a significant reduction in composite adverse maternal outcome without affecting the neonatal outcome [12]. An observational study has also shown that the onset of mild gestational hypertension or mild preeclampsia at or near term is associated with minimal to low maternal and fetal complications [13].

World Health Organization (WHO) recommends expectant management of preeclampsia without severity feature until 37 weeks [14]. In Ethiopia in general and Saint Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC), preeclampsia without severity features is managed expectantly until 37 weeks. At SPHMMC preeclampsia without severity feature is managed as an outpatient with once per week visit. Patients will visit their physician once per week and evaluated for any severe features by history, blood pressure(BP) measurement, laboratory evaluation, and obstetric ultrasound.

The justification for expectant management was the risk of increased assisted vaginal delivery, cesarean section and prematurity, and its complication, thus generating additional morbidity and cost [15]. On the other hand, there is the possibility of progression of the preeclampsia without severe feature to preeclampsia with severity feature leading to eclampsia, severe hypertension, abruption, pulmonary edema, HEELP (Hemolysis, Elevated liver Enzymes and Low Platelet) syndrome and adverse neonatal outcome [5, 16–18].

The optimal management of preeclampsia without severe features remains controversial especially in developing countries like Ethiopia where home-based self-care like blood pressure monitoring is barely possible. Limited studies suggest that patients offered outpatient monitoring should be able to comply with frequent maternal and fetal evaluations, some form of blood pressure monitoring at home and should have ready access to medical care [4, 19, 20]. There is no data on maternal and perinatal outcomes of preeclampsia without severity feature in Ethiopia with current outpatient management by once per week visit. The aim of the study was; therefore, to determine the maternal and perinatal outcome of expectantly managed pregnant women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia without severity feature between gestational age of 28 and 36 completed weeks at the tertiary teaching hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at Saint Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from August 1, 2018, to January 31, 2019. SPHMMC is a tertiary teaching referral hospital giving the highest maternity service in Ethiopia. The hospital handles complicated obstetric cases and often referring normal or less complicated pregnant mothers to other hospitals or health centers for birth. According to the statistics office of the hospital, 9000 births were attended in 2018,35% of births were by cesarean section. This was a prospective non-comparative observational study conducted to determine the maternal and perinatal outcome of expectantly managed pregnant women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia without severity feature among women receiving Antenatal care (ANC) and birthing at Saint Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College. Preeclampsia without severity feature was the exposure variable. Outcome variables considered in this study were admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Confounding variables were socio-demographic characteristics (maternal age, educational status, occupation, residency) and obstetrics variables (Gravidity, mode of delivery, gestational age, ANC visit).

Operational definitions

Preeclampsia without severe feature: raised BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg plus 24-hour urine protein greater than or equal to 300mg/24 hour or urine dipstick >+1 after 20 weeks of gestation in previously normotensive women [2].

Adverse perinatal outcome: pregnancy outcome including stillbirth, growth restriction (IUGR), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), low birth weight, low 5th minute APGAR score, neonatal death.

Stillbirth: fetus born with no sign of life after 28 weeks of gestational age.

Adverse maternal outcome: pregnancy complicated by severe preeclampsia [2] with one of the following features: cerebral symptoms (like visual disturbance, headache), right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, serum transaminase concentration ≥ twice normal, systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg, and or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mm Hg, severe thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets/micro), acute kidney injury and pulmonary edema. Eclampsia, Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation(DIC), abruption, HEELP (Hemolysis, Elevated liver Enzymes, and Low Platelet) syndrome, and maternal death was also considered as an adverse maternal outcome.

Expectant management: Women who have at least one visit at SPHMMC with an established diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features between 28–36 weeks of gestational age.

Early-onset preeclampsia without severe feature: preeclampsia without severe feature diagnosed at a gestational age between 28–34 weeks.

Late-onset preeclampsia without severe feature: preeclampsia without severe feature diagnosed at a gestational age between 34–36 weeks.

The study Included all consented pregnant women, irrespective of the number of gestations, with the diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe feature at a gestational age of 28 weeks to 36 weeks who had at least one visit and managed at SPHMMC from August 1/2018 to January 31/2019. Pregnant women with gestational age less than 28 weeks and greater than 36 weeks, those with other types of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy like preeclampsia with severity feature, gestational hypertension, eclampsia, superimposed preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and patients with known fetal lethal congenital anomalies were excluded from the study. Pregnant mothers with comorbid chronic medical disorders like diabetes, severe anemia, renal disease, cardiac disease, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and those with known TORCH infections were also excluded.

Data were collected by trained midwives at regular ANC units, emergency unit and labour ward and nurse at NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. At initial visit data collectors at regular ANC enrolled those mothers who consented and diagnosed to have preeclampsia without severe features based on criteria and then documented their socio-demographic and obstetrics characters. Card and phone number of mothers were also registered for later tracing of maternal and perinatal outcomes. Women were followed till birth and data regarding maternal and perinatal outcomes was collected using a well-structured questionnaire by observation and from the maternal and neonatal cards at the birth unit and NICU including the first week after delivery. For those discharged home maternal and neonatal condition was checked on the seventh day during follow up and those who didn’t appear on follow up day were reminded by cell phone call.

After data collection, data cleaning was performed to check for outliers, missed values, and any inconsistencies. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics (frequency and proportions) were used to characterize the variables and determine the proportion of maternal and perinatal outcomes of preeclampsia without severe features. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to see the association of variables and to identify independent factors affecting maternal and perinatal outcomes and control confounders. Odds Ratio (OR),95% confidence interval and a P-value set at 0.05 were used to determine the statistical significance of the association.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Saint Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College ethical review committee. Written informed consent to conduct a study and publish the outcome was obtained from each patient and confidentiality was maintained during data collection, analysis, and interpretation. All the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the manuscript and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results of the study

Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of participants

There was a total of 5400 births at SPHMMC during the study period of which 164 (3.0%) of them were women managed with the diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features. In this cohort of women diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe feature was made by BP and urine dipstick for protein >+1 in 102 (62.2%) women. The remaining 62 (37.8%) of women were diagnosed to have preeclampsia with raised BP and twenty-four-hour urine protein excretion greater than 300 mg. Gestational age at the time of diagnosis was between 28–36 weeks and there was no loss to follow up.

Most of the women 99 (60.4%) were aged 20–34 years and lived in Addis Ababa 117 (71.3%). Most women were multigravida 84 (51.2%) and the gestation at first presentation was predominantly between 34+0 weeks and 36+6 weeks. Table 1 describes the Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of the cohort. (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio demographic and obstetric characteristics of mothers on expectant management with a diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe feature at SPHMMC,2018 (N = 164).

| Variable. | Category. | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Religion. | Orthodox | 75(45.7%) |

| Muslim | 67(40.9) | |

| Protestant | 20(12.2%) | |

| Catholic | 2(1.2%) | |

| Age(years) | <20 | 41(25%) |

| 20–34 | 99(60.4%) | |

| 35–49 | 24(14.6%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 146(89%) |

| Single | 15(9.1%) | |

| Divorced | 3(1.9%) | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 49(29.9%) |

| Primary | 89(54.3%) | |

| Secondary | 23(14%) | |

| College and above | 3(1.8%) | |

| Occupation | Government employee | 23(14%) |

| Merchant | 43(26.2%) | |

| Housewife | 81(49.3%) | |

| Daily laborer | 17(10.5%) | |

| Residency | From Addis Ababa. | 117(71.3%) |

| Rural. | 47(28.7%) | |

| Gravidity | Primigravida. | 80(48.8%) |

| Multigravida. | 84(51.2%) |

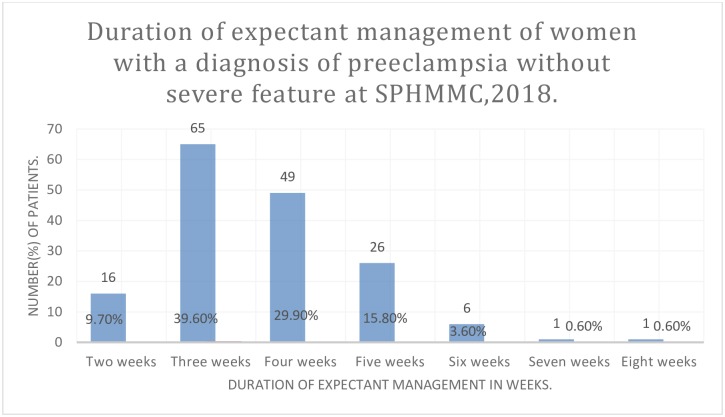

The mean duration of expectant management was 4.6 weeks. The follow-up duration ranges from two weeks to eight weeks. Figure one describes the duration of expectant management in weeks with a respective number of women (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Duration of expectant management of women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe feature at SPHMMC, 2018.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes of the study population

One third (52, 31.7%) of the women had maternal complications of which 32 (19.5%) progressed to preeclampsia with a severe feature. There were two (1.22%) maternal deaths. Thirty-two (19.5%) of women delivered before 37 weeks. Twenty-two (12.5%) of neonates had a birth weight of less than 2.5 kg. Sixty (36.6%) neonates were admitted to NICU. There were three (1.7%) stillbirths and four (2.27%) early neonatal deaths. The perinatal mortality rate was 4.26% (42.6/1000). Five (71%) of perinatal deaths occurred in preterm births. Table 2 describes the maternal, fetal and neonatal adverse outcomes.

Table 2. Maternal, fetal and neonatal complications of expectantly managed preeclampsia without severe feature at SPHMMC, 2018.

| Outcome measures | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal complications | ||

| Preeclampsia with severity | 32 | 19.5 |

| Placental abruption | 9 | 5.4 |

| Partial/complete HEELP | 4 | 2.43 |

| Eclampsia | 2 | 1.22 |

| DIC | 2 | 1.22 |

| Maternal death | 2 | 1.22 |

| 2. Fetal complications | ||

| Stillbirth. | 3 | 1.7 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction(IUGR). | 22 | 12.5 |

| Preterm birth | 32 | 18.18 |

| 3. Neonatal complications. | ||

| NICU admission | 60 | 36.6 |

| Low APGAR score. | 4 | 2.27 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome(RDS). | 7 | 3.97 |

| Early neonatal death(END). | 4 | 2.27 |

Factors associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes

Occupation, religion, marital status, educational status and place of residency are not associated with poor maternal and perinatal outcomes. There is no significant difference in the rate of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes between primigravid and multigravida women. Women older than 35 years were 2.54 times more likely to develop adverse maternal outcomes compared to those in the middle age group (20–35) with a P-value of 0.030, (95%CI 1.021–6.32). Those patients with early onset of preeclampsia without severe feature were 5.22 and 25.9 times more likely to develop maternal and perinatal complication respectively compared to late-onset preeclampsia after 34 weeks with P-value of <0.0001, (95% CI 2.01–13.6) and <0.0001, (95% CI 5.75–115.6) respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes during expectant management of preeclampsia without severe feature at SPHMMC, 2018.

| Character. | Adverse maternal outcome. | COR(95%Cl) | AOR(95%Cl) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <20years | 16 | 25 | 1,63(0.75–3.48) | 1.26(0,56–2.81) | 0.2147 |

| 20–34 years | 28 | 71 | 1 | 1 | |

| >35 years | 12 | 12 | 2.54(1.02–6.32) | 1.56(1.01–2.77) | 0.030 |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 31 | 49 | 1.493(0.78–2.846) | 1.704(0.84–3.45) | 0.2260 |

| Multi gravida | 25 | 59 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gestational age | |||||

| 28–34 weeks | 19 | 14 | 4.99(2.24–11.12) | 5.22(2.01–13.6) | 0.0001 |

| 34–36 weeks | 28 | 103 | 1 | 1 | |

| Character. | Adverse perinatal outcome | ||||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <20years | 24 | 21 | 2.22(0.92–4.54) | 1.41(0.66–3.03) | 0.0285 |

| 20–34 years | 35 | 68 | 1 | 1 | |

| >35 years | 13 | 15 | 1.68(0.72–3.93) | 1.12(0.68–1.74) | 0.2281 |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 40 | 52 | 1.25(0.65–2.3) | 1.24(0.63–2.35) | 0.4684 |

| Multigravida | 32 | 52 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gestational age | |||||

| 28–33 weeks + 6 days. | 33 | 8 | 10.15(4.31–23.87) | 25.9(5.75–115.6) | <0.0001 |

| 34–36 weeks | 39 | 96 | 1 | 1 | |

Discussion

The current study is peculiar in that deals it with preeclampsia without severity feature alone which is unlike previous studies [10, 21–24]. The incidence of preeclampsia without severe features in this study was about 3.0% and 60.4% of women in the current study were in the age group 20–34. This finding is similar to other studies [7, 9, 22].

In this study gestational age at the time of diagnosis was between 34–36 weeks in 68.9% of the participants and 31.1% of the pregnant women presented at a gestational age between 28–33 weeks and 6 days. This finding is comparable to a study conducted in India that showed the incidence of late-onset preeclampsia (beyond 34 weeks) to be 72.4% and early-onset preeclampsia 27.6% with higher maternal and perinatal complications in early-onset preeclampsia [22].

The average duration of expectant management was 4.6 weeks and 34.1% of women developed one or more of the maternal, fetal or neonatal complications. In our study maternal complication was seen in 31.7% These complications were: progression to severe preeclampsia (18.2%), placental abruption (5%), HELLP syndrome (2.4%) and DIC (1.22%). These complications are high compared to a retrospective analysis of the incidence of severe disease in mild preeclampsia in China which showed 6% of preeclampsia women developed one of the following severe features: placental abruption (2.8%), eclampsia (0.9%%) and HELLP syndrome (0.6%) [25] There were two (1.22%) cases of eclampsia and maternal death in the current study which was high for women on follow up compared to similar study [25], which might imply outpatient follow up with once per week visit is inadequate for early identification and management of progression to severe preeclampsia.

The perinatal mortality in our study was 42.6 per 1000, while the overall perinatal complication rate was about 40.9%. Preterm birth was the commonest perinatal complication observed in this study accounting for 18.2%., Intrauterine growth restriction occurred in 12% of the cases, stillbirth occurred in about 1.7% and 2.27% of newborn ended up in early neonatal death. This finding is comparable to other study findings [22, 26], but since these studies are reporting on cumulative preeclampsia it’s difficult to make an exact comparison.

Consistent with other studies [27–29], the current study showed early onset of preeclampsia without severe feature was associated with increased risk of developing adverse maternal-fetal/neonatal outcomes compared to late-onset after 34 weeks. The increased perinatal complication seen might be explained by the progression of preeclampsia to severe diseases in those women who developed preeclampsia before 34 weeks and concomitant high preterm birth [30, 31]. Women older than 35 years have 2.54 times increased chance of having an adverse maternal outcome in this study compared to those in the middle age group (20–35).

The current study has limitations. Having gestational age-matched non-exposed (without preeclampsia) group would have been important to controlling confounders like the quality of care and preterm birth associated morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

In a setting where home-based self-care is poor expectant outpatient management of preeclampsia without severe features with a once per week visit is not adequate. It’s associated with an increased risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Our findings call for special consideration and close surveillance of those women with early-onset diseases.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank midwives and physicians who helped us with patient recruitment and data collection. We are grateful to our patients for their willingness to participate in the study.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Ante-Natal Care

- APGAR

Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration

- DIC

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

- END

Early Neonatal Death

- HELLP

Hemolysis Elevated Liver Enzyme Platelet

- HYPITAT

Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial at near

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- IUGR

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

- LBW

Low Birth Weight

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- RCT

Randomized Control Trial

- RDS

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- SPHMMC

Saint Paulo’s Hospital Millennium Medical College

- SPSS

Statistical Package of Social science

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.ACOG https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy.

- 2.The International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy: The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice (Pregnancy Hypertension, 2018) http://www.isshp.org/guidelines. ISSHP. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2013;170(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;102(1):181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibai BM, Barton JR. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: patient selection, treatment, and delivery indications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):514.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belay AS, Wudad T. Prevalence and associated factors of pre-eclampsia among pregnant women attending anti-natal care at Mettu Karl referral hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Clinical hypertension. 2019;25:14-. 10.1186/s40885-019-0120-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berhe AK, Kassa GM, Fekadu GA, Muche AA. Prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Ethiopia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2018;18(1):34 10.1186/s12884-018-1667-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaym A, Bailey P, Pearson L, Admasu K, Gebrehiwot Y, Team ENEA. Disease burden due to pre‐eclampsia/eclampsia and the Ethiopian health system's response. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2011;115(1):112–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muluneh M, Wagnew M, Worku A, Nyagero J. Trends of preeclampsia/eclampsia and maternal and neonatal outcomes among women delivering in Addis Ababa selected government hospitals, Ethiopia: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endeshaw G, Berhan Y. Perinatal Outcome in Women with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2015;2015:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odendaal HJ, Pattinson RC, Bam R, Grove D, Kotze T. Aggressive or expectant management for patients with severe preeclampsia between 28–34 weeks' gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1990;76(6):1070–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, Vijgen SM, Aarnoudse JG, Bekedam DJ, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks' gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomized controlled trial. The Lancet. 2009;374(9694):979–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts J, August A, Bakris G, Barton J, Bernstein I, Druzin M. Hypertension, pregnancy-induced-practice guideline. Washington, USA: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. https://wwwwhoint/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/9789241548335/en/. 2011. [PubMed]

- 15.Van Gemund N, Hardeman A, Scherjon S, Kanhai H. Intervention rates after elective induction of labor compared to labor with spontaneous onset. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2003;56(3):133–8. 10.1159/000073771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibai BM, Mercer BM, Schiff E, Friedman SA. Aggressive versus expectant management of severe preeclampsia at 28 to 32 weeks' gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(3):818–22. 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90104-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML, Jones M. Does gestational hypertension become pre‐eclampsia? BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1998;105(11):1177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, Jacques DL, Sibai BM. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: progression and outcome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;184(5):979–83. 10.1067/mob.2001.112905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster DA, McLachlan HL, Davey M-A, Biro MA, Farrell T, Gold L, et al. Continuity of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) increases women's satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care: results from the COSMOS randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barton JR, Stanziano GJ, Sibai BM. Monitored outpatient management of mild gestational hypertension remote from term. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1994;170(3):765–9. 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70279-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deepak A, Reena R, Anirudhan D. Fetal and maternal outcome following expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term. 2017;6(12):5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aabidha PM, Cherian AG, Paul E, Helan J. Maternal and fetal outcome in pre-eclampsia in a secondary care hospital in South India. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2015;4(2):257 10.4103/2249-4863.154669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abalos E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Qureshi Z, Widmer M, Vogel J, et al. Pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes: a secondary analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014;121:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magee LA, Yong PJ, Espinosa V, Cote AM, Chen I, von Dadelszen P. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: a structured systematic review. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2009;28(3):312–47. 10.1080/10641950802601252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Q, Shen F, Gao YF, Zhao M. An analysis of expectant management in women with early-onset preeclampsia in China. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(6):379–84. 10.1038/jhh.2014.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abate M, Lakew Z. Eclampsia a 5 years retrospective review of 216 cases managed in two teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa. Ethiopian medical journal. 2006;44(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomathy E, Akurati L, Radhika K. Early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia-maternal and perinatal outcomes in a rural tertiary health center. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018;7(6):2266–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoopala HM, Hall DR. Re-evaluation of abruptio placentae and other maternal complications during expectant management of early-onset pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;16:38–41. 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wojtowicz A, Zembala-Szczerba M, Babczyk D, Kołodziejczyk-Pietruszka M, Lewaczyńska O, Huras H. Early-and Late-Onset Preeclampsia: A Comprehensive Cohort Study of Laboratory and Clinical Findings according to the New ISHHP Criteria. International journal of hypertension. 2019;2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolobo HA, Chaka TE, Kassa RT. Determinants of neonatal mortality among newborns admitted to neonatal intensive care unit Adama, Ethiopia: A case-control study. Journal of Clinical Neonatology. 2019;8(4):232 http://www.jcnonweb.com/article.asp?issn=2249-4847;year=2019;volume=8;issue=4;spage=232;epage=237;aulast=Kolobo;type=0. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhe LM, McClure EM, Nigussie AK, Mekasha A, Worku B, Worku A, et al. Major causes of death in preterm infants in selected hospitals in Ethiopia (SIP): a prospective, cross-sectional, observational study. The Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(8):e1130–e8 https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X19302207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.