Abstract

We evaluated the minimum inhibitory concentrations of clindamycin and erythromycin toward 98 Bacillus licheniformis strains isolated from several types of fermented soybean foods manufactured in several districts of Korea. First, based on recent taxonomic standards for bacteria, the 98 strains were separated into 74 B. licheniformis strains and 24 B. paralicheniformis strains. Both species exhibited profiles of erythromycin resistance as an acquired characteristic. B. licheniformis strains exhibited acquired clindamycin resistance, while B. paralicheniformis strains showed unimodal clindamycin resistance, indicating an intrinsic characteristic. Comparative genomic analysis of five strains showing three different patterns of clindamycin and erythromycin resistance identified 23S rRNA (adenine 2058-N6)-dimethyltransferase gene ermC and spermidine acetyltransferase gene speG as candidates potentially involved in clindamycin resistance. Functional analysis of these genes using B. subtilis as a host showed that ermC contributes to cross-resistance to clindamycin and erythromycin, and speG confers resistance to clindamycin. ermC is located in the chromosomes of strains showing clindamycin and erythromycin resistance and no transposable element was identified in its flanking regions. The acquisition of ermC might be attributable to a homologous recombination. speG was identified in not only the five genome-analyzed strains but also eight strains randomly selected from the 98 test strains, and deletions in the structural gene or putative promoter region caused clindamycin sensitivity, which supports the finding that the clindamycin resistance of Bacillus species is an intrinsic property.

Introduction

Recently, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has been speculated to be a potent reservoir of antibiotic-resistance genes, and the food chain is considered a possible transfer route for antibiotic resistance from animal- and environment-associated antibiotic-resistant bacteria into the human GI tract where antibiotic-resistance genes may be transferred to pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria [1]. Thus, food fermentation starters with antibiotic resistance genes can act as possible reservoirs and vehicles for transfer of antibiotic resistance determinants to microbiota in fermented foods, and these determinants can then spread to humans through food consumption. In this context, the European Food Safety Authority requires the absence of any acquired genes for antimicrobial resistance that could cause potential risks to humans when implementing a strain for human use. Although the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in food ecosystems is becoming a global concern, only pathogenic bacteria and lactic acid bacteria have received particular attention, and limited information is available about the antibiotic resistance of Bacillus spp.

Bacillus spp. have been reported as populous bacteria present in alkaline-fermented foods from Asia and Africa, especially in Asian fermented soybean foods [2]. In this context, they have been considered to be potential candidate starter cultures for Asian and African fermented food production. Bacillus spp. are also used for biotechnological applications, including as probiotic dietary supplements for humans and animal feed inoculants, based on their ability to stimulate the immune system and produce antimicrobial compounds inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms [3].

B. licheniformis is an extensively used species in many bioindustries. B. licheniformis can be intentionally added to foods or feeds in the European Union based on the European Food Safety Authority’s qualification of the species as a safe biological agent [4], and the US Food and Drug Administration allows genetically modified strains of this species to be used for enzyme production.

B. licheniformis has been isolated as a predominant species in fermented soybean foods from Korea and exhibits the highest salt tolerance among isolated Bacillus spp. [5]. Based on the salt tolerance and high protease activity, we considered that B. licheniformis could be a potential starter culture candidate for high-salt soybean fermentations. We assessed the antibiotic susceptibilities and technological properties of 94 B. licheniformis isolates from our stock cultures to select a safe and functional candidate starter strain [6]. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of eight tested antibiotics (chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, tetracycline, and vancomycin) were determined for the 94 isolates; clindamycin and erythromycin susceptibility profiles exhibited acquired resistance properties. However, B. licheniformis strains from African traditional bread showed intrinsic resistance to clindamycin [7]. Acquired antibiotic resistance occurs as a result of either genetic mutation of pre-existing genes or horizontal transfer of new genes. Intrinsic antibiotic resistance is a natural insensitivity in bacteria that have never been susceptible to a particular antibiotic. Possession of an intrinsic antibiotic resistance gene is not a safety concern in the selection of bacterial strains for human use.

In staphylococci, resistance to clindamycin and erythromycin was reported to occur through methylation of their ribosomal target sites [8]. The ribosomal target site modification mechanism, so-called macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance, results in cross-resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, and streptogramin B. Such resistance is typically mediated by erythromycin ribosome methylase (Erm) genes and is the most widespread resistance mechanism to macrolides and lincosamides [9].

To clarify the genomic background explaining clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis, we evaluated the MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin toward an additional 98 B. licheniformis strains isolated in Korea and undertook comparative genomic analysis of five strains exhibiting different patterns of clindamycin and erythromycin resistance.

Materials and methods

Bacillus strains and cultures

To evaluate the MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin for B. licheniformis with diverse strains, we collected 42 and 56 B. licheniformis strains from the Korea Food Research Institute (http://www.kfri.re.kr) and the Microbial Institute for Fermentation Industry (http://mifi.kr), respectively. The strains were isolated from several types of fermented soybean foods manufactured in several districts of Korea.

Genome sequence-published strains B. licheniformis DSM 13T (KCTC 1918T) and B. paralicheniformis KJ-16T (KACC 18426T) were purchased from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC; http://kctc.kribb.re.kr/) and the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC; http://genebank.rda.go.kr/), respectively. Genome sequence-published strains B. licheniformis 14ADL4 (KCTC 33983), B. licheniformis 0DA23-1 (KCTC 43013), and B. paralicheniformis 14DA11 (KCTC 33996) were isolated from traditional Korean fermented soybean foods and are deposited at KCTC [10–12]. All Bacillus strains were cultured in tryptic soy agar (TSA; BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD, USA) and tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD Diagnostic Systems) at 30°C for 24 h.

Taxonomic identity confirmation of B. licheniformis strains

The identity of 98 strains was confirmed by spo0A (stage 0 sporulation protein A) gene sequence analysis [13].

Determination of MICs

MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin were determined by the broth microdilution method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [14]. A twofold serial dilution was prepared for each antibiotic in deionized water, and final concentrations in each well of the microplate ranged between 0.5 and 4096 mg/L. Tested strains were cultured twice in TSB and matched to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France). The cultured strains were further diluted (1:100) in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hants, UK) to achieve the desired inoculum concentration. The final inoculum density was 5×105 colony-forming units/mL in each well in 96-microwell plates. Microwell plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h to determine the MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin. The MIC of each antibiotic was recorded as the lowest concentration where no growth was observed in the wells after incubation for 18 h. MIC results were confirmed by at least three independently performed tests.

Comparative genomic analysis

For comparative genomic analysis of the genomes of Bacillus strains showing different clindamycin and erythromycin resistance patterns, complete genome sequence data for B. paralicheniformis 14DA11 (CRER, clindamycin and erythromycin resistance; GenBank accession, NZ_CP023168), B. paralicheniformis KJ-16T (CRER; LBMN02000039), B. licheniformis DSM 13T (CRES, clindamycin resistance and erythromycin sensitivity; NC_006270), B. licheniformis 14ADL4 (CRES; CP026673), and B. licheniformis 0DA23-1 (CSES, clindamycin and erythromycin sensitivity; CP031126) were obtained from NCBI (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes). The Efficient Database framework for comparative Genome Analyses using BLAST score Ratios (EDGAR) was used for core genome, pan-genome, and singleton analyses [15]; the genome of strain 0DA23-1 was used as a reference genome for Venn diagram construction in analysis of the five genomes. Comparative analyses at the protein level were performed by an all-against-all comparison of the annotated genomes. The algorithm used was BLASTP and data were normalized according to the best score [16]. The score ratio value, which shows the quality of the hit, was calculated by dividing the scores of further hits by that for the best hit [17]. Two genes were considered orthologous when a bidirectional best BLAST hit with a single score ratio value threshold of ≥32% was obtained in orthology estimation.

Identification of potential clindamycin resistance genes

Genomic DNA of Bacillus strains was extracted using a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Identification of potential clindamycin resistance genes was performed by PCR amplification with specific primer sets ermC-106/ermC-535, ereAB-229/ereAB-806, and speG-23/speG-243 (Table 1) using a T-3000 Thermocycler (Biometra, Gottingen, Germany). PCR mixtures consisted of template DNA, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.25 units of Taq polymerase (Inclone Biotech, Daejeon, Korea), 10 mM dNTPs, and 2 mM MgCl2. Samples were preheated for 5 min at 95°C and then amplified using 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Amplified PCR products were sequenced using a custom service provided by Bionics (Seoul, Korea). The web-hosted BLAST program was used to find sequence homologies of the amplified fragments with known gene sequences in the NCBI database. For the analysis of putative promoter sequences of speG, the primer set PspeG-Up/PspeG-Down was designed based on the genome sequence of strain 14DA11 (Table 1).

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5ʹ–3ʹ) | Use |

|---|---|---|

| ermC-106 | ATTGTGGATCGGGCAAATATT | ermC identification |

| ermC-535 | TGGAGGGGGAGAAAAATG | ermC identification |

| ereAB-229 | CTGCATCAGGAATTAGGATTTC | ereAB identification |

| ereAB-806 | TTGATGTGAAGGTTGTGAGCC | ereAB identification |

| speG-23 | GTCCGCTTGAAAGAGAAGACC | speG identification |

| speG-243 | TTATGATTTGAAACTCCGCC | speG identification |

| ermC-Up | TCCCCCGGGGATGAGAGGAAGAGGAAACATG | ermC cloning |

| ermC-Down | GAAGATCTTATTTCTCCGGGTTTTCGCTTATTTGC | ermC cloning |

| ereAB-Up | CCGATATCGGAGAGATTCAAGAGATGGGCAACC | ereAB cloning |

| ereAB-Down | GAAGATCTCCTTAGAGGTTATGCTTAACCCGTC | ereAB cloning |

| speG-Up | CCGATATCGATCGGCCTGCGCCTTACATCAT | speG cloning |

| speG-Down | GAAGATCTGGGAAGAGGTTGACAAAGACG | speG cloning |

| pCL55-itet-F | GGCCCTTTCGTCTTCAAGAAT | Cloned DNA sequence confirmation |

| pCL55-itet-R | ATTTTACATCCCTCCGGATCC | Cloned DNA sequence confirmation |

| PspeG-Up | GTTCGCTTAGTGCTCTGGTGATC | Putative speG promoter identification |

| PspeG-Down | GCGGACGCAATTTAAGCTGATT | Putative speG promoter identification |

Restriction sites are underlined. The boxed sequence is the deleted region of speG absent from the gene in strain 0DA23-1.

Cloning of potential clindamycin resistance genes

Total DNAs of B. paralicheniformis strains 14DA11 and KJ-16T were used as the templates for PCR amplification of potential clindamycin resistance genes. The candidates, 23S rRNA (adenine 2058-N6)-dimethyltransferase gene (ermC), erythromycin esterase gene (ereAB), and spermidine acetyltransferase gene (speG), were amplified with primer sets ermC-Up/ermC-Down, ereAB-Up/ereAB-Down, and speG-Up/speG-Down, respectively (Table 1). Each primer contained a restriction enzyme site: SmaI in ermC-Up; EcoRV in ereAB-Up and speG-Up; and BglII in ermC-Down, ereAB-Down, and speG-Down. The amplified PCR products were double-digested with SmaI/BglII or EcoRV/BglII and then inserted into EcoRV and BglII digested pCL55-itet under the control of a tetracycline inducible promoter [18]. The successful integration of the target fragments was confirmed by sequence analysis using primer set pCL55-itet-F/pCL55-itet-R. Plasmid DNA was introduced into B. subtilis ISW1214 by electroporation [19] with a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell growth monitoring in the presence of clindamycin and erythromycin

Transformants cultured in TSB were normalized to 0.5 turbidity at OD600 and then diluted 1:100 in TSB supplemented with clindamycin or erythromycin to check the function of candidate genes. Clindamycin and erythromycin were employed at 32 μg/mL. Cell growth was monitored by measuring OD600 using a Varioskan Flash (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All analyses were performed in triplicate on independent samples prepared in the same way.

Results and discussion

Taxonomic status of 98 B. licheniformis strains

Recently, B. paralicheniformis was separated from B. licheniformis on the basis of phylogenomic and phylogenetic studies [20]. spo0A sequence analysis separated 24 strains as B. paralicheniformis from the 98 strains previously identified as B. licheniformis.

Clindamycin and erythromycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis

The MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin toward the 74 B. licheniformis strains and 24 B. paralicheniformis strains are summarized in Table 2. Four B. licheniformis strains and 21 B. paralicheniformis strains were resistant to erythromycin, and their resistance profiles exhibited an acquired characteristic. More than fourfold higher resistance to clindamycin than the breakpoint was identified in 70.2% of the 74 B. licheniformis strains and the population distribution of the 74 strains was discontinuous. B. paralicheniformis strains exhibited a unimodal clindamycin resistance profile, which supports that this resistance is an intrinsic characteristic.

Table 2. Distribution of 74 Bacillus licheniformis and 24 Bacillus paralicheniformis strains isolated from traditional Korean fermented soybean foods over a range of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for clindamycin and erythromycin.

| Species | Antibiotic | MIC (mg/L) | Breakpoint (mg/L)a | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 | |||

| B. licheniformis | Clindamycin | 15 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 19 | 12 | 4 | ||||||

| Erythromycin | 25 | 23 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||

| B. paralicheniformis | Clindamycin | 2 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Erythromycin | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20 | 4 | ||||||||||

aBreakpoint values for Bacillus spp. taken from EFSA [21].

If independent determinants of clindamycin and erythromycin resistance contribute to the phenotype of Bacillus strains, four combinations of phenotypes can be exhibited. Three such patterns of resistance (CRER; CRES; and CSES) were identified among the B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis strains we tested (Table 3). These results stimulated further studies to illuminate the determinants and characteristics of clindamycin resistance in B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis.

Table 3. MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin, and identification of ermC, ereAB, speG, and putative speG promoter in selected B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis strains.

| Phenotype | Species | Strain | GenBank accession no. | MIC (mg/L) | Gene identification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin | Erythromycin | ermC | ereAB | speG | Promotera | ||||

| CRER | B. paralicheniformis | 14DA11 | CP023168 | 32 | 2048 | + | – | + | – |

| B. paralicheniformis | KJ-16T | LBMN00000000 | 16 | 4096 | + | + | + | – | |

| B. paralicheniformis | SRCM100038 | – | 128 | 4096 | + | + | + | – | |

| B. licheniformis | SRCM100160 | – | 128 | 4096 | + | – | + | + | |

| B. licheniformis | SRCM100163 | – | 32 | 2048 | + | + | + | + | |

| CRES | B. licheniformis | 14ADL4 | CP026673 | 64 | 0.5 | – | – | + | + |

| B. licheniformis | DSM 13T | CP000002.3 | 128 | 0.5 | – | – | + | + | |

| B. paralicheniformis | CHKJ1206-1 | – | 16 | 2 | – | – | + | + | |

| B. paralicheniformis | CHKJ1310 | – | 16 | 1 | – | – | + | + | |

| B. licheniformis | TPP0006 | – | 64 | 2 | – | – | + | + | |

| CSES | B. licheniformis | 0DA23-1 | CP031126 | 0.5 | 0.5 | – | – | ND | + |

| B. licheniformis | F1082 | – | 0.5 | 2 | – | – | ND | + | |

| B. licheniformis | SRCM100107 | – | 0.5 | 0.5 | – | – | ND | + | |

Strains with names beginning “SCRM” were selected from 56 strains kindly provided by the Microbial Institute for Fermentation Industry. Strains CHKJ1206-1, CHKJ1310, TPP0006, and F1082 were selected from 42 strains kindly provided by the Korea Food Research Institute.

ND means nucleotide deletions occurred in the open reading frame. aIdentification of a putative promoter sequence upstream of speG.

Genomic insight into clindamycin resistance

To shed light on the genetic background behind clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis, we attempted comparative genome analysis of five strains showing different clindamycin and erythromycin resistance patterns (S1 Table).

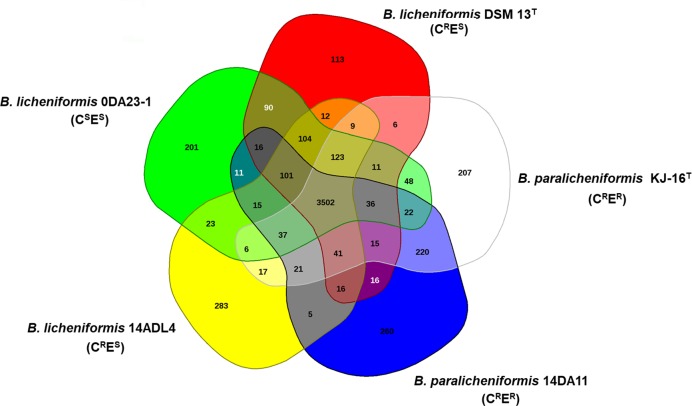

The gene pools shared by the genomes of the five strains—B. paralicheniformis 14DA11 (CRER), B. paralicheniformis KJ-16T (CRER), B. licheniformis DSM 13T (CRES), B. licheniformis 14ADL4 (CRES), and B. licheniformis 0DA23-1 (CSES)—are depicted in a Venn diagram (Fig 1). The five strains share 3,502 protein-coding sequences (CDSs) in their core genome, corresponding to 73.5%–81.7% of their own open reading frames. Many of the CDSs in the core genome were assigned via Clusters of Orthologous Groups annotation to functions relating to metabolism and the transport of amino acids and carbohydrates.

Fig 1. Venn diagram of five Bacillus genomes (B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis).

The Venn diagram shows the pan-genome of strains 0DA23-1, DSM 13T, KJ-16 T, 14DA11, and 14ADL4 generated using EDGAR. Overlapping regions represent common coding sequences (CDSs) shared between the genomes. The numbers outside the overlapping regions indicate the numbers of CDSs in each genome without homologs in the other genomes.

Comparative genomic analysis revealed that two CRER strains, KJ-16T and 14DA11, shared 220 CDSs that are absent from the other three analyzed Bacillus genomes (Fig 1). The shared CDSs correspond to 4.6% and 4.8% of the total CDSs, respectively, and include an annotated ermC (S2 Table). A variety of erm genes have been reported in a large number of microorganisms and ermC is a typical staphylococcal gene class that can endow MLSB resistance [22]. PCR amplification with the ermC-specific primer set ermC-106/ermC-535 confirmed the presence of ermC in strains exhibiting the CRER phenotype (Tables 1 and 3). ermC potentially contributes to the clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis.

An annotated ereAB was identified only in the genome of strain KJ-16T (CRER) and this gene was amplified from some of the CRER strains with an ereAB-specific primer set (Tables 1 and 3). Erythromycin esterase was reported to confer erythromycin resistance through erythromycin esterification [23].

Comparative genomic analysis revealed that two CRES strains, DSM13T and 14ADL4, have 12 CDSs that are shared only between them (Fig 1 and S3 Table). Four of these CDSs were predicted hypothetical protein-encoding genes. Six CDSs were homologs of multicopy genes and homologs were identified in the genomes of strains 0DA23-1, 14DA11, and KJ-16T. The other two genes were a putative lysine transporter gene and a DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase gene. However, we could not find any earlier report to correlate those genes with clindamycin resistance.

Erm proteins were reported to dimethylate a single adenine in nascent 23S rRNA, which is part of the large 50S ribosomal subunit [8]. Schlunzen et al. [24] reported that the nucleotide residues G2057, A2058, A2059, A2503, A2505, and C2611 of the Escherichia coli 23S rRNA sequence are interaction sites with the lincosamide clindamycin and nucleotide residues G2057, A2058, A2059, A2062, A2505, and C2609 interact with the macrolide erythromycin. We could not find any difference in the corresponding base residues of the 23S rRNA sequences of the five genome-analyzed B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis strains (S4 Table). This finding supports that 23S rRNA gene mutation was not the cause of clindamycin or erythromycin resistance in these strains.

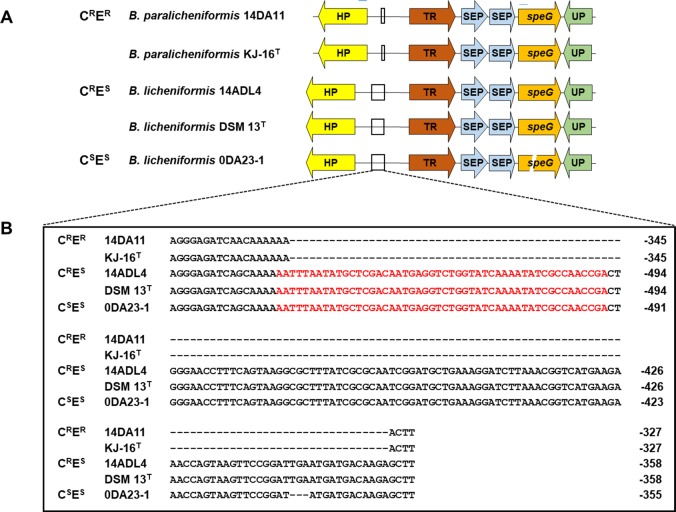

We found a report of synergistic effects between biogenic polyamines (e.g., spermidine and spermine) and antibiotics on the antibiotic susceptibility of clinically-relevant bacteria [25]. The synergistic effect of spermidine with clindamycin, gentamicin, and mupirocin, all of which are important antibiotics for treatment of staphylococcal infection, was disrupted by the presence of speG [26]. A putative speG was identified in all five Bacillus genomes. Strain 0DA23-1 (CSES) possessed a frame-shifted speG with a deletion of 11 nucleotides, while the other four strains (CRER and CRES) possessed speG with the same DNA sequence as each other (Fig 2). We identified speG in eight strains randomly selected from the 98 Bacillus strains by PCR amplification with primer set speG-23/speG-243, which was designed to encompass the deleted region of speG as observed in strain 0DA23-1 (Table 1). The gene was identified in all CRER and CRES strains, while an amplicon was not produced from strains F1082 and SRCM100107, which have a CSES phenotype (Table 3).

Fig 2.

Genetic structures surrounding the speG genes (A) and the putative speG promoter sequences (B) in Bacillus strains. Abbreviations: HP, hypothetical protein gene; TR, TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator gene; SEP, spermidine export protein gene; speG, spermidine acetyltransferase gene; UP, uncharacterized protein gene. Red letters indicate the putative promoter sequences detected using PromoterHunter software. Negative numbers show the upstream locations from TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator genes.

To find clues about how speG may have been acquired, we analyzed DNA sequences of the flanking regions of speG in five genome-analyzed strains (Fig 2). The five strains had the same genetic organization around speG in their chromosome and mobile elements were not found around the gene. However, DNA sequence differences were identified in their putative promoter sequences, detected using PromoterHunter software [27]. Two CRER strains, 14DA11 and KJ-16T, lacked the putative promoter region, while three strains sensitive to erythromycin (CRES and CSES) possessed this region. The clindamycin resistance of the two CRER strains might be attributable to the expression of ermC. To determine whether promoter deletion is a common event in B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis CRER strains, we analyzed the promoter region of eight more strains showing phenotypes CRER, CRES, and CSES randomly selected from the 98 MIC-tested strains (Table 3). Two CRER B. licheniformis strains possessing the promoter were identified. These results indicated that the expression of speG can contribute to the CRER phenotype in Bacillus species, but the phenotype mainly depends on possession of ermC. The CRES phenotype may be attributed to the expression of speG in the absence of ermC.

Functional analysis of potential clindamycin resistance genes

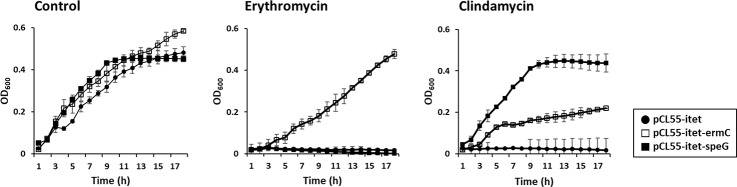

To confirm the function of ermC, the locus CK945_RS15790 of strain 14DA11 was amplified and inserted into pCL55-itet under the control of a tetracycline inducible promoter (Table 4). The resulting plasmid was designated pCL55-itet-ermC. B. subtilis ISW1214 harboring pCL55-itet-ermC grew in the presence of 32 μg/mL erythromycin, while the host containing pCL55-itet did not grow under erythromycin pressure (Fig 3). The ermC-expressing transformant also grew in the presence of 32 μg/mL clindamycin. The MICs of clindamycin and erythromycin for B. subtilis ISW1214 containing pCL55-itet-ermC were 512 mg/L and 4096 mg/L, respectively. These results confirmed that ermC was responsible for the cross-resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis to erythromycin and clindamycin.

Table 4. Potential clindamycin resistance determinants identified in five Bacillus genomes.

| Product | Gene | Gene locus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM 13T | 14ADL4 | 0DA23-1 | 14DA11 | KJ-16T | ||

| 23S rRNA (adenine 2058-N6)-dimethyltransferase | ermC | CK945_RS15790 | ACH97_219465 | |||

| Erythromycin esterase | ereAB | ACH97_221905 | ||||

| Spermidine acetyltransferase | speG | TRNA_RS31465 | BL14DL4_00234 | BLDA23_RS10890 | CK945_RS11785 | ACH97_208005 |

Fig 3. Effects of ermC and speG on the growth of B. subtilis ISW1214 transformants under clindamycin and erythromycin stress.

The locus CK945_RS11785 of strain 14DA11 was amplified and used to construct a recombinant plasmid containing speG in the same way as pCL55-itet-ermC was constructed. The resulting plasmid was named pCL55-itet-speG. The transformant harboring pCL55-itet- speG grew in the presence of 32 μg/mL clindamycin, but did not grow under 32 μg/mL erythromycin pressure (Fig 3). The MIC of clindamycin for B. subtilis ISW1214 containing pCL55-itet-speG was >512 mg/L. Thus, speG was proved to endow clindamycin resistance to B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis.

The locus ACH97_221905 of strain KJ-16T was amplified and used to construct recombinant plasmid pCL55-itet-ereAB containing ereAB. The transformant harboring pCL55-itet-ereAB did not exhibit clindamycin or erythromycin resistance.

The intrinsic gene speG endows clindamycin resistance

Several studies have reported that erm genes located in mobile elements such as plasmid pE194 contribute to erythromycin resistance of bacteria [7, 28–30] and these genes can also endow clindamycin resistance [9]. In this study, we also found that ermC causes erythromycin and clindamycin resistance in B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis, while the gene is located not in mobile elements but in the chromosomes of CRER strains (S1 Fig). No transposable element was identified in the flanking regions of ermC, which suggests that insertion events by mobile elements are not the cause of ermC acquisition. The acquisition of ermC might be attributable to a homologous recombination.

Although the possible working mechanism of speG in clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis was not postulated owing to clindamycin and spermidine being chemically distinct, this study is the first to illuminate that speG contributes to the clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis and the gene was detected in not only the five genome-analyzed strains but also in eight strains randomly selected from the 98 Bacillus test strains (Table 3). We found that nucleotide deletions in this gene caused clindamycin sensitivity. We also found strains with a deletion in the putative promoter region of speG; such deletion caused clindamycin sensitivity. This study proved that clindamycin resistance of Bacillus species is an intrinsic property which can be lost by deletion events in the structural gene or promoter of speG. Therefore, clindamycin resistance of B. licheniformis and B. paralicheniformis is not a safety concern in the selection of bacterial strains for human use. However, their erythromycin susceptibility needs to be evaluated to clarify the determinants acquisition.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

EDGAR analysis was kindly performed by Dr. Jochen Blom at Justus-Liebig University. We thank James Allen, DPhil, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) [NRF-2016R1D1A1B01011421 for JHL and NRF-2019R1A2C1003639 for DWJ]. YO was supported by Kyonggi University’s Graduate Research Assistantship 2020. The EDGAR platform is financially supported by BMBF grant FKZ031A533 within the de.NBI network. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sommer MOA, Dantas G, Church GM. Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science. 2009;325(5944):1128–1131. 10.1126/science.1176950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamang JP, Watanabe K, Holzapfel WH. Review: Diversity of mcroorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:377 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutting SM. Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiol. 2011;28(2):214–220. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EFSA. Update of the list of QPS-recommended biological agentsintentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA 5:suitability of taxonomic units notified to EFSA until September 2016. EFSA J. 2016;15(3):4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong DW, Kim HR, Jung G, Han S, Kim CT, Lee JH. Bacterial community migration in the ripening of doenjang, a traditional Korean fermented soybean food. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24(5):648–660. 10.4014/jmb.1401.01009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong DW, Jeong M, Lee JH. Antibiotic susceptibilities and characteristics of Bacillus licheniformis isolates from traditional Korean fermented soybean foods. LWT—Food Sci Technol. 2017;75:565–568. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adimpong DB, Sorensen KI, Thorsen L, Stuer-Lauridsen B, Abdelgadir WS, Nielsen DS, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacillus strains isolated from primary starters for African traditional bread production and characterization of the bacitracin operon and bacitracin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(22):7903–7914. 10.1128/AEM.00730-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(3):577–585. 10.1128/aac.39.3.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leclercq R. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):482–492. 10.1086/324626 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Jeong DW. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11, exhibiting resistance to clindamycin and erythromycin. Genome Announc. 2017;5(43):e01216–17. 10.1128/genomeA.01216-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong DW, Lee B, Lee JH. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus licheniformis 14ADL4 exhibiting resistance to clindamycin. Korean J Microbiol. 2018;54(2):169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong DW, Lee B., Heo S., Jang M., Lee J.H Complete genome sequence of Bacillus licheniformis strain 0DA23-1, a potential starter culture candidate for soybean fermentation. Korean J Microbiol. 2018;54(4):453–455. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong DW, Lee B, Lee H, Jeong K, Jang M, Lee JH. Urease characteristics and phylogenetic status of Bacillus paralicheniformis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;28(12):1992–1998. 10.4014/jmb.1809.09030 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blom J, Albaum SP, Doppmeier D, Puhler A, Vorholter FJ, Zakrzewski M, et al. EDGAR: a software framework for the comparative analysis of prokaryotic genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:154 10.1186/1471-2105-10-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blom J, Kreis J, Spanig S, Juhre T, Bertelli C, Ernst C, et al. EDGAR 2.0: an enhanced software platform for comparative gene content analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W22–8. 10.1093/nar/gkw255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lerat E, Daubin V, Moran NA. From gene trees to organismal phylogeny in prokaryotes: the case of the gamma-Proteobacteria. PLoS biology. 2003;1(1):E19 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundling A, Schneewind O. Genes required for glycolipid synthesis and lipoteichoic acid anchoring in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(6):2521–2530. 10.1128/JB.01683-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong DW, Cho H, Lee H, Li C, Garza J, Fried M, et al. Identification of the P3 promoter and distinct roles of the two promoters of the SaeRS two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4672–4684. Epub 2011/07/19. 10.1128/JB.00353-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlap CA, Kwon SW, Rooney AP, Kim SJ. Bacillus paralicheniformis sp. nov., isolated from fermented soybean paste. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65(10):3487–3492. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000441 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EFSA. Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 2012;10:2740–2749. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts MC, Sutcliffe J, Courvalin P, Jensen LB, Rood J, Seppala H. Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(12):2823–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morar M, Pengelly K, Koteva K, Wright GD. Mechanism and diversity of the erythromycin esterase family of enzymes. Biochemistry. 2012;51(8):1740–1751. 10.1021/bi201790u . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlunzen F, Zarivach R, Harms J, Bashan A, Tocilj A, Albrecht R, et al. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature. 2001;413(6858):814–821. 10.1038/35101544 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon DH, Lu CD. Polyamine effects on antibiotic susceptibility in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(6):2070–2077. 10.1128/AAC.01472-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Planet PJ, LaRussa SJ, Dana A, Smith H, Xu A, Ryan C, et al. Emergence of the epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 coincides with horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element and speG-mediated adaptations for survival on skin. mBio. 2013;4(6):e00889–13. 10.1128/mBio.00889-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klucar L, Stano M, Hajduk M. phiSITE: database of gene regulation in bacteriophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D366–70. 10.1093/nar/gkp911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lodder G, Werckenthin C, Schwarz S, Dyke K. Molecular analysis of naturally occuring ermC-encoding plasmids in staphylococci isolated from animals with and without previous contact with macrolide/lincosamide antibiotics. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18(1):7–15. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01022.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horinouchi S, Weisblum B. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pE194, a plasmid that specifies inducible resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin type B antibodies. J Bacteriol. 1982;150(2):804–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westh H, Hougaard DM, Vuust J, Rosdahl VT. erm genes in erythromycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. APMIS. 1995;103(3):225–232. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.