Abstract

Background

The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of central nervous system tumors stratifies isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)–mutant gliomas into 2 major groups depending on the presence or absence of 1p/19q codeletion. However, the grading system remains unchanged and it is now controversial whether it can be still applied to this updated molecular classification.

Methods

In a large cohort of 911 high-grade IDH-mutant gliomas from the French national POLA network (including 428 IDH-mutant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion and 483 anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeleted), we investigated the prognostic value of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene homozygous deletion as well as WHO grading criteria (mitoses, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis). In addition, we searched for other retinoblastoma pathway gene alterations (CDK4 amplification and RB1 homozygous deletion) in a subset of patients. CDKN2A homozygous deletion was also searched in an independent series of 40 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas.

Results

CDKN2A homozygous deletion was associated with dismal outcome among IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion (P < 0.0001 for progression-free survival and P = 0.004 for overall survival) as well as among anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, IDH-mutant + 1p/19q codeleted (P = 0.002 for progression-free survival and P < 0.0001 for overall survival) in univariate and multivariate analysis including age, extent of surgery, adjuvant treatment, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis. In both groups, the presence of microvascular proliferation and/or necrosis remained of prognostic value only in cases lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion. CDKN2A homozygous deletion was not recorded in grade II gliomas.

Conclusions

Our study pointed out the utmost relevance of CDKN2A homozygous deletion as an adverse prognostic factor in the 2 broad categories of IDH-mutant gliomas stratified on 1p/19q codeletion and suggests that the grading of these tumors should be refined.

Keywords: anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeleted, anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, glioblastoma, IDH-mutant, microvascular proliferation, CDKN2A homozygous deletion

Key Points.

1. CDKN2A homozygous deletion characterizes diffuse malignant IDH-mutant gliomas with worst outcome.

2. Microvascular proliferation stratifies IDH-mutant gliomas lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion.

Importance of the Study.

The 2016 WHO classification of central nervous system tumors stratifies IDH-mutant gliomas in 2 major groups of distinct prognosis depending on the presence of 1p/19q codeletion. However, it remains controversial whether WHO histopathological grading remains significant in these groups. Here we showed in a large cohort of 428 malignant IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion that CDKN2A homozygous deletion was a strong adverse prognosis factor. The same results were recorded in 483 anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, IDH-mutant + 1p/19q codeleted. Moreover, in each group microvascular proliferation (associated or not with necrosis) was of prognostic relevance among tumors lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion. Of importance, CDKN2A homozygous deletion was not recorded in an independent series of 40 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas. These results are of interest for a future grading approach of IDH-mutant gliomas.

Diffuse gliomas are the most frequent and aggressive primary brain tumors in adults. They are stratified according to the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of central nervous system tumors1 into 3 major groups depending on the presence or absence of 2 genetic alterations: isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation and 1p/19q codeletion. Among malignant diffuse gliomas in adults, the worst prognosis is recorded in glioblastoma (GB) IDH wild type (grade IV), the best in anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO) IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted (grade III), whereas the last group of malignant glioma, IDH mutant without 1p/19q codeletion (which comprises anaplastic astrocytoma [AA], IDH mutant grade III; and GB, IDH mutant grade IV), carries an intermediate prognosis.

Besides, although IDH gene status has been the major criterion for the classification of adult diffuse gliomas, no change has been made in the 2016 WHO classification regarding the grading system based on histologic criteria and it is now unclear, whereas it can still be applied. Indeed, some recent studies have highlighted that grades II and III IDH-mutant astrocytic tumors share the same prognosis,2–6 whereas other authors still report a prognostic significance of the grade.7

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) is a gene located at chromosome 9, band p21.3. In the “pre-IDH era,” some studies had reported a prognostic value of CDKN2A genetic alteration in different glioma subtypes, including grades II and III astrocytoma.8,9 Recent studies identified homozygous deletions involving CDKN2A/B as a statistically significant marker of poor prognosis in IDH-mutant astrocytic gliomas,7,10 whereas other authors reported the prognostic relevance of combined altered retinoblastoma pathway gene alterations, including CDKN2A/B, CDK4, and RB1.11–13 As a consequence, among IDH-mutant astrocytic tumors (ie, lacking 1p/19q codeletion) the actual 2016 WHO grading classification based solely on histologic criteria does not seem fully appropriate, and some authors7,11 have suggested including additional genetic markers such as copy number variation or CDKN2A/B status. Regarding AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted, we reported a few years ago that allelic loss of 9p21.3, including CDKN2A, was an adverse prognostic factor; however, we did not investigate the prognostic value of the specific CDKN2A locus homozygous deletion.14

In France, since 2008, a dedicated program has been set up to homogenize the management of de novo adult high-grade glioma with an oligodendroglial component (the POLA [Prise en charge des Oligodendrogliomes Anaplasiques/Management of Anaplastic Oligodendrogliomas] network). One of the aims of the program was to provide a pathological centralized review of glioma cases with an oligodendroglial component and histologic features of malignancy (including the presence of microvascular proliferation [MVP] or necrosis and, in cases lacking these criteria, a mitotic activity superior to 1 per 10 high-power field [HPF] for oligoastrocytomas and superior to 6 per 10 HPF for oligodendrogliomas). In the present study we took advantage of the large series of patients included in the POLA network to investigate the prognostic relevance of CDKN2A homozygous deletion as well as the prognostic value of the WHO 2016 grading system based on histologic criteria (MVP and necrosis) in 911 high-grade IDH-mutant gliomas, including 428 IDH-mutant high-grade astrocytic tumors (212 AA IDH mutant and 216 GB IDH mutant) and 483 AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted. In addition, we searched for other retinoblastoma pathway gene alterations (CDK4 amplification and RB1 homozygous deletion) in a subset of patients. Because the POLA series lack grade II gliomas, we also searched for the occurrence of CDKN2A homozygous deletion in an independent series of 40 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas (20 diffuse astrocytomas IDH mutant and 20 oligodendrogliomas IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted).

Materials and Methods

Study Population

A total number of 911 patients from the French nationwide POLA network were included in this study. Inclusion criteria were: (i) the written consent of the patient for clinical data collection and genetic analysis according to national and POLA network policies, (ii) sufficient material for molecular studies allowing concordance with the WHO 2016 classification (ie, evaluation of IDH mutation + 1p/19q codeletion status), and (iii) an established diagnosis of high-grade glioma (WHO grade III or IV) with IDH mutation. This study was approved by the ethics committees or institutional review boards of all participating institutes.

Pathological Review

All cases were centrally reviewed by Prof D. Figarella-Branger (or Dr K. Mokhtari for the patients managed in the city of Marseille). Evaluated in all cases were the mitotic index (defined as the number of mitotic figures per 10 HPF), the Ki67 labeling index (defined as the number of immunostained nuclei with Ki67 antibody [clone Mib1, 1/100, Dako] in 400 cells in the most positive area), and the presence or absence of MVP and necrosis (either palisading or not). The mitotic activity threshold that should be used to distinguish WHO grade II diffuse astrocytoma from WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma is not provided by the WHO classification. In this study, we used the number of mitotic figures per 10 HPF superior to 1 as the threshold for the diagnosis of AA IDH mutant. Similarly, in the absence of MVP and necrosis we retained a diagnosis of AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted when the number of mitotic figures per 10 HPF was superior to 6.

IDH mutation status was assessed by immunohistochemistry with anti–IDH1 R132H antibody (clone H09, 1/75, Dianova) and in almost all cases (901/911) by direct sequencing using the Sanger method and primers as previously described.15 The genomic profile and assessment of 1p/19q codeletion status was determined based on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) arrays, or microsatellite marker analysis as previously described.15

Evaluation of Retinoblastoma Pathway Gene Alterations

CDKN2A homozygous deletion status was retrieved from POLA electronic case report forms. CDKN2A homozygous deletion was evaluated by SNP arrays (n = 552) when DNA extracted from frozen tissue was available. Outsourced for the SNP array experiments (Integragen) was 1.5 µg of DNA. Two types of platforms were used: HumanCNV370-Quad and Human610-Quad from Illumina. When only DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue was available, CDKN2A homozygous deletion was assessed using oligonucleotide-based CGH arrays (Agilent, n = 111) or next generation sequencing (NGS) (BrainCap Custom Capture from Roche, n = 227). Depending on the technology used, CDKN2A homozygous deletion was evaluated by visual assessment of copy number profiles for SNP array and CGH array analysis or visual examination of the depth of CDKN2A sequencing coverage compared with adjacent regions for NGS analysis. When the quantity of DNA was insufficient to perform SNP or CGH arrays (n = 4), the genomic profile was assessed by PCR-based loss-of-heterozygosity assays as described elsewere.16

Additionally, we retrieved available SNP array data regarding RB1 homozygous deletion and CDK4 amplification status from 436 cases, including 189 IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion and 247 AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted. As described previously, these alterations were evaluated by visual assessment of copy number profiles.

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical data collected included sex, age at diagnosis, extent of surgery (biopsy or resection), date of surgery, adjuvant treatment, date of relapse, and date of death or last contact. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to recurrence or death from any cause, censored at the date of the last documented disease evaluation. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to death from any cause, censored at the date of last contact.

Additional Independent Cohort of Grade II IDH-Mutant Gliomas

We retrieved copy number variation analysis profiles for an additional independent cohort of 40 patients with grade II IDH-mutant gliomas, including 20 diffuse astrocytomas IDH mutant and 20 oligodendrogliomas IDH-mutant + 1p/19q codeleted. IDH mutation status of all these cases was assessed by both immunohistochemistry and Sanger sequencing, and the genomic profile was assessed using oligonucleotide-based CGH arrays as previously described. Follow-up data were not recorded for this series because these were cases of recent diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival distributions. Log rank tests were used for univariate comparisons. Cox proportional hazards models were used for multivariate analyses. Multivariate analysis included CDKN2A homozygous deletion and clinical or pathological characteristics with a P-value <0.05 in univariate analyses (ie, age at diagnosis, extent of surgery, adjuvant treatment, and the presence of MVP and/or necrosis considered as composite criteria, which correspond to WHO grades III versus IV among the IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion). All statistical tests were two-sided, and the threshold for statistical significance was P = 0.05. Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS statistics software v24. In addition, to explore how covariables can predict outcome, we used a machine learning algorithm based on the random survival forest method17 (“randomForestSRC” and “ggRandomForests” packages, R-project v3.3.3, https://www.r-project.org). It allows the determination of the variable importance as predictor of outcome (ie, corresponding to the delta error rate with vs without the inclusion of the variable in the model). We included CDKN2A deletion, 1p/19q codeletion status, MVP, and the presence of necrosis in the random forest survival using 1000 tree iteration to predict PFS and OS.

Results

Clinical and Pathological Features Among the WHO 2016 Subgroups

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Nine hundred eleven patients with a diagnosis of IDH-mutant glioma were included in this study, 428 cases fulfilled the diagnosis of IDH-mutant malignant glioma without 1p/19q codeletion (212 AA IDH mutant and 216 GB IDH mutant) and 483 cases fulfilled the diagnosis of AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted.

Table 1.

Clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics of the 911 IDH-mutant glioma cohort and their association with PFS and OS

| Clinical, Pathological and Molecular Characteristics | IDH-Mutant Gliomas without 1p/19q Codeletion (All) | Anaplastic Astrocytoma IDH-Mutant | Glioblastoma IDH-Mutant | Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma IDH-Mutant + 1p/19q Codeleted | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | PFS | OS | N (%) | PFS | OS | N (%) | PFS | OS | N (%) | PFS | OS | |

| Total | 428 | 212 | 216 | 483 | ||||||||

| Median age (range) | 39.5 (17.1–83.1) | 0.004 | 0.001 | 39.2 (17.1–83.1) | 0.014 | 0.002 | 40.2 (17.6–77) | 0.064 | 0.042 | 49.5 (19.4–87.1) | 0.013 | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 189 (44) | 0.423 | 0.806 | 101 (48) | 0.760 | 0.349 | 88 (41) | 0.147 | 0.492 | 197 (41) | 0.06 | 0.541 |

| Male | 239 (56) | 111 (52) | 128 (59) | 286 (59) | ||||||||

| Extent of surgery | ||||||||||||

| Resection | 313 (73) | 143 (67) | 170 (79) | 375 (78) | ||||||||

| Biopsy | 92 (21) | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 56 (26) | 0.062 | 0.023 | 36 (17) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 81 (17) | <0.0001 | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 23 (5) | 13 (6) | 10 (5) | 27 (6) | ||||||||

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||||||||

| None | 42 (10) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 24 (11) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 18 (8) | <0.0001 | 0.018 | 40 (8) | <0.0001 | 0.036 |

| RT alone | 20 (5) | 7 (3) | 13 (6) | 93 (19) | ||||||||

| CT alone | 52 (12) | 32 (15) | 20 (10) | 89 (19) | ||||||||

| RT + PCV | 96 (23) | 69 (33) | 27 (12) | 83 (17) | ||||||||

| RT + TMZ | 218 (50) | 80 (38) | 138 (64) | 178 (37) | ||||||||

| Pathological features | ||||||||||||

| Microvascular proliferation | 216 (50) | 0.014 | <0.0001 | 0 | NA | NA | 216 (100) | NA | NA | 364 (75) | 0.122 | 0.096 |

| Necrosis | 73 (17) | 0.032 | 0.02 | 0 | NA | NA | 73 (34) | 0.277 | 0.489 | 111 (23) | 0.08 | 0.438 |

| Genetic alterations | ||||||||||||

| CDKN2A homozygous deletion | 47 (11) | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 12 (6) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 35 (16) | 0.003 | 0.08 | 33 (7) | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| CDK4 amplification | 6 (3.2) | 0.433 | 0.610 | 0 | NA | NA | 6 (4.7) | 0.350 | 0.882 | 1 (0.4) | 0.418 | 0.632 |

| Rb1 homozygous deletion | 9 (4.8) | 0.696 | 0.756 | 5 (8.1) | 0.353 | 0.964 | 4 (3.1) | 0.014 | 0.978 | 0 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; PCV, procarbazine + lomustine + vincristine; TMZ, temozolomide.

Among patients with IDH-mutant malignant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion, the median age at diagnosis was 39.5 years (range, 17.1–83.1 y). They were 239 men and 189 women. Seventy-seven percent benefited from surgical resection and half received adjuvant concomitant radiotherapy combined with temozolomide. The median follow-up was 35 months (range, 0–109 mo). During this follow-up period, 196 patients relapsed and 110 died. Among the clinical variables analyzed, age (≤39.5 y), surgical resection, and adjuvant treatment were predictive of a longer PFS (respectively P = 0.004, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001) and a longer OS (respectively P = 0.001, P = 0.001, and P < 0.001). In accordance with the 2016 WHO classification, among the 428 cases (AA and GB IDH mutant), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis (corresponding to GB IDH mutant) was associated with a shorter PFS (P = 0.014) and OS (P < 0.001). By definition AA IDH mutant displayed neither MVP nor necrosis. Among the 212 AA IDH mutant, we failed to identify a threshold for mitotic count or Ki67 labeling index that could be of prognostic significance (Supplementary Table 1). Among the 216 GB IDH mutant, necrosis, when present, was always associated with MVP, 143 cases demonstrated MVP without necrosis, whereas 73 displayed MVP and necrosis, and we did not observe a prognostic relevance of necrosis on PFS (P = 0.277) or OS (P = 0.489).

Regarding AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted, the median age at diagnosis was 49.5 years (range, 19.4–87.1 y). They were 286 men and 197 women. Eighty-two percent benefited from surgical resection and 37% received adjuvant concomitant radiotherapy combined with temozolomide. The median follow-up was 45 months (range, 0–114 mo). During this follow-up period, 163 patients relapsed and 66 died. Among the clinical variables analyzed, age (≤49.5 y), surgical resection, and adjuvant treatment were predictive of a longer PFS (respectively P = 0.013, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001) and OS (respectively P < 0.0001, P = 0.001, and P = 0.036). In accordance with the 2016 WHO classification, the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was not associated with survival. Of note, necrosis, when present, was always associated with MVP. Furthermore, among the 119 AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted without MVP and/or necrosis, we failed to identify a threshold for mitotic count or Ki67 labeling index that could be of prognostic significance (Supplementary Table 1).

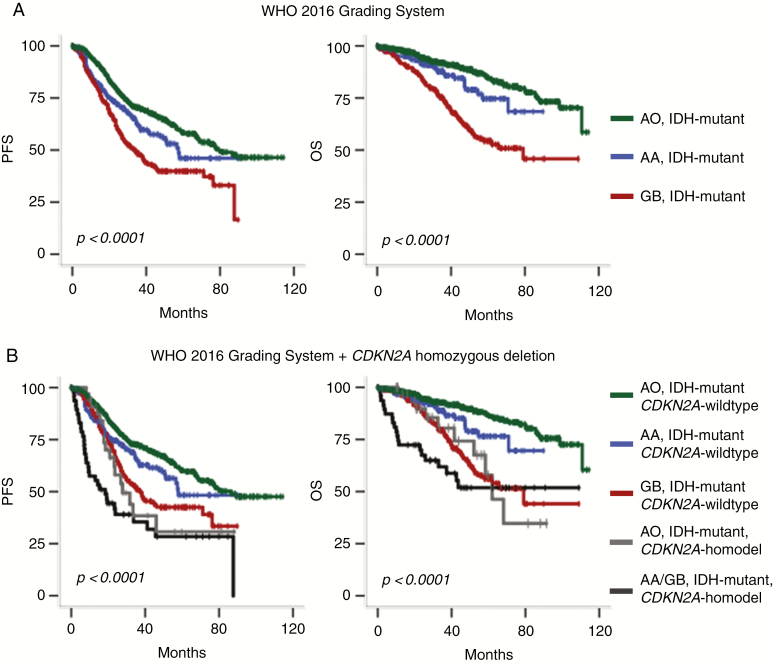

Univariate analysis performed in the whole group of 911 patients showed that the 2016 WHO integrated diagnosis was of prognostic value (P < 0.0001 for both PFS and OS; Fig. 1A). In addition, the machine learning algorithm based on the random survival forest method revealed that 1p/19q codeletion was the most important variable to predict both PFS and OS, followed by CDKN2A homozygous deletion and MVP, whereas necrosis was the worst variable (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the 911 IDH-mutant gliomas. (A) Stratification on the WHO 2016 classification. (B) Stratification on both WHO 2016 classification and CDKN2A status.

Prognostic Relevance of Retinoblastoma Pathway Genetic Alterations Among IDH-Mutant Gliomas without 1p/19q Codeletion

Among the 428 IDH-mutant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion (AA and GB), the presence of CDKN2A homozygous deletion was associated with worse outcome for PFS (P < 0.0001) and for OS (P = 0.004) (Table 1). In multivariate analysis including age at diagnosis, extent of surgery (resection versus biopsy), adjuvant treatment (radiotherapy plus chemotherapy vs others), MVP and necrosis, CDKN2A homozygous deletion was also predictive of shorter PFS (P < 0.001; hazard ratio [HR], 2.121; 95% CI = 1.399–3.216) and shorter OS (P = 0.046; HR, 1.722; 95% CI = 1.011–2.935) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis

| Clinical, Pathological, or Molecular Characteristics | IDH-Mutant Gliomas without 1p/19q Codeletion (N = 428) | Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma IDH Mutant + 1p/19q Codeleted (N = 483) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | OS | PFS | OS | |||||||||

| P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age (>median) | 0.042 | 1.405 | 1.013–1.949 | 0.023 | 1.643 | 1.072–2.518 | 0.062 | 1.412 | 0.982–2.031 | 0.001 | 4.025 | 1.801–8.992 |

| Surgical resection | 0.014 | 0.616 | 0.419–0.905 | 0.002 | 0.457 | 0.277–0.753 | 0.025 | 0.634 | 0.426–0.946 | 0.089 | 0.580 | 0.310–1.088 |

| Adjuvant treatment | <0.0001 | 0.328 | 0.230–0.468 | <0.0001 | 0.293 | 0.188–0.456 | 0.065 | 0.731 | 0.524–0.1020 | 0.937 | 0.978 | 0.563–1.699 |

| MVP and/or necrosis | <0.0001 | 1.855 | 1.311–2.625 | <0.0001 | 2.936 | 1.792–4.810 | 0.052 | 1.570 | 0.995–2.475 | 0.241 | 1.614 | 0.725–3.593 |

| CDKN2A homozygous deletion | 0.001 | 2.084 | 1.374–3.162 | 0.049 | 1.707 | 1.001–2.911 | 0.020 | 1.909 | 1.106–3.294 | 0.015 | 2.673 | 1.209–5.908 |

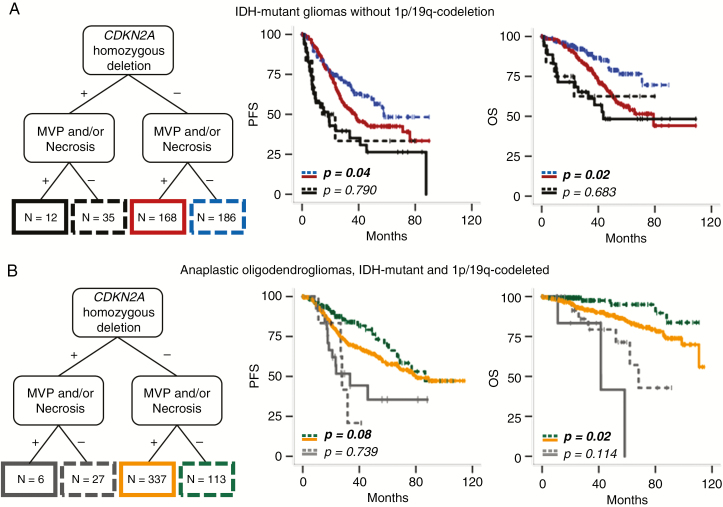

Besides, the WHO 2016 grading system (ie, presence of MVP and/or necrosis) was still relevant for PFS (P = 0.04) and for OS (P = 0.002) among tumors lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 354), whereas it lost its prognostic relevance among tumors with CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 47) (P = 0.790 for PFS and P = 0.683 for OS) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the 911 IDH-mutant gliomas stratified on 1p/19q codeletion, pathological criteria, and CDKN2A status. (A) Among IDH-mutant tumors without 1p/19q codeletion and without CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 354), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was associated with shorter PFS (P = 0.04) and OS (P = 0.002), whereas among tumors with CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 47), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was relevant for neither PFS (P = 0.790) nor OS (P = 0.683). (B) Among AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted without CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 450), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was not relevant for PFS (P = 0.085) but was associated with shorter OS (P = 0.028), whereas among tumors with CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 33), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was relevant for neither PFS (P = 0.739) nor OS (P = 0.114).

Among IDH-mutant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion, the presence of neither RB1 homozygous deletion nor CDK4 amplification had prognostic value (Table 1).

Prognostic Relevance of Retinoblastoma Pathway Genetic Alterations Among the AO IDH Mutant + 1p/19q Codeleted Subgroup

Among the 483 AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted subgroup, the presence of CDKN2A homozygous deletion was a strong adverse prognostic factor for PFS (P = 0.002) and OS (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). In multivariate analysis including age at diagnosis, extent of surgery, adjuvant treatment, and MVP and necrosis, CDKN2A homozygous deletion was also predictive of shorter PFS (P = 0.048; HR, 1.750; 95% CI = 1.004–3.049) and shorter OS (P = 0.026; HR, 2.539; 95% CI = 1.121–5.750) (Table 2).

Besides, among tumors lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 450) the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was relevant for OS (P = 0.028), although not statistically significant for PFS (P = 0.085) (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, among tumors with CDKN2A homozygous deletion (n = 33), the presence of MVP and/or necrosis was relevant for neither PFS (P = 0.739) nor OS (P = 0.114) (Fig. 2B).

Among AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted, the presence of neither RB1 homozygous deletion nor CDK4 amplification had prognostic value (Table 1).

Correlation Between CDKN2A Homozygous Deletion, Mitotic Index, and Ki67 Labeling Index

Among the 911 IDH-mutant gliomas, the presence of CDKN2A homozygous deletion was associated with higher mitotic count (median = 7 per 10 HPF, range 2–40, P < 0.0001) and higher Ki67 labeling index (median = 20%, range 2–70, P < 0.0001) compared with gliomas without CDKN2A alteration (median mitotic count = 6 per 10 HPF, range 1–50, and median Ki67 labeling index = 15%, range 1–90) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

CDKN2A Homozygous Deletion Prevalence Among Grade II IDH-Mutant Gliomas

We did not observe any CDKN2A homozygous deletion among the 40 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas of our additional series including 20 diffuse astrocytoma IDH mutant and 20 oligodendrogliomas IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the prognostic value of CDKN2A homozygous deletion as well as current histopathological criteria (mitosis, MPV and necrosis) in a large cohort of 911 high-grade IDH-mutant gliomas (428 IDH-mutant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion and 483 AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted) from the French national POLA network. In addition, we searched for other retinoblastoma pathway gene alterations (CDK4 amplification and RB1 homozygous deletion) in a subset of patients. We also searched for CDKN2A homozygous deletion in an independent cohort of 40 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas (20 diffuse astrocytomas IDH mutant and 20 oligodendroglioma IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted).

Our results point out the utmost prognostic relevance of CDKN2A homozygous deletion in the 2 categories of diffuse malignant IDH-mutant gliomas stratified on 1p/19q codeletion. Moreover, CDKN2A homozygous deletion appears as the first stratification risk, before the assessment of MVP and/or necrosis. Among them, MVP seems to be the most appropriate, since in our study it is of greater prognostic significance compared with necrosis. This last result is discrepant from a previous study7 that showed a greater prognostic relevance of necrosis compared with MVP and used this criterion (depending on the model, in addition or not to the copy number variable load value) to stratify IDH-mutant astrocytoma without CDKN2A/B alteration.

A limitation of our study design might be the potential effect on survival of the treatment, since the therapeutic recommendations evolved with the recommendations of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)18 and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group.19 Thus, we cannot exclude that the heterogeneity of the treatment within each histomolecular category might influence survival. Nonetheless, CDKN2A homozygous deletion remained of prognostic significance in multivariate analysis including treatment, therefore supporting its independent prognostic value.

The CDKN2A locus on chromosome band 9p21 encodes for 2 tumor suppressors, protein p14ARF and p16INK4A, both inhibiting cell cycle progression. P14ARF activates the well-known “guardian of the genome,” p53, which plays an important role in growth arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis.20–22 P16INK4A inhibits CDK4 and CDK6, which activate the retinoblastoma family of proteins and block G1 to S phase transition. In accordance with these functions, homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A locus alters its inhibitory function and might contribute to uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation. Not surprisingly, therefore, in our cohort of 911 high-grade IDH-mutant gliomas, we observed a strong correlation between CDKN2A homozygous deletion, mitotic count (P < 0.001), and Ki67 labeling index (P < 0.001). Previous studies reported the prognosis value of other retinoblastoma pathway alterations, including RB1 homozygous deletion7,13 and CDK4 amplification,11–13 but we did not observe a prognostic significance of these alterations in our study.

The major prognostic impact of CDKN2A homozygous deletion in malignant diffuse IDH-mutant gliomas might have strong implication in daily practice, since it will require the search for this genetic alteration in all malignant diffuse IDH-mutant gliomas. Whether this alteration should also be investigated in grade II remains to be resolved. We learned from our study that this alteration was not recorded in grade II IDH-mutant gliomas. The same results were also reported previously in a series of 54 grade II IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion.7 However, other authors observed CDKN2A loss in some cases of oligodendroglioma IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted.2,8

The methods used for CDKN2A homozygous deletion assessment should be validated in each laboratory. Previous studies reported that p16 immunohistochemical detection cannot be considered as a surrogate technique to detect CDKN2A homozygous deletion.7,8,23 In our study, among the IDH-mutant gliomas without 1p/19q codeletion, the number of cases with CDKN2A homozygous deletion was similar regardless of the technique used for detection: 11% (28/257) with SNP array, 12% (7/57) with CGH array, and 12% (11/94) with NGS. Our results are comparable to the proportion of cases observed among the EORTC cohort (11%, 17/154) and the cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (14%, 31/224) reported by Shirahata et al,7 a little lower than their discovery cohort (18%, 38/211) and the Heidelberg cohort (23%, 25/108) and much lower than the cohort reported by Korshunov et al10 (43%, 42/97). We do not have a clear explanation for the low frequencies of retinoblastoma pathway gene alterations observed in our study in comparison with others but it is consistent with the longest OS of the GB IDH-mutant subgroup (median OS in our study = 79 mo) compared with previously reported survival data among this histomolecular group7,10,12,24 (median OS ranging from 33 to 60 mo). Nevertheless, although the median OS was not reached among the IDH-mutant gliomas lacking 1p/19q codeletion with CDKN2A homozygous deletion, the Kaplan–Meier curve suggests a median OS of around 37 months, which is similar to the outcome reported in other studies.7,10

Altogether, and as also suggested previously by other authors,7,11 our results suggest that the strong negative impact of CDKN2A homozygous deletion on survival in the subgroup of IDH-mutant astrocytomas should be included as a criterion in the grading scheme of these tumors (Fig. 1B). Therefore, a malignant IDH-mutant astrocytoma exhibiting CDKN2A homozygous deletion might be considered as grade IV and thus independently of the occurrence of MVP (or necrosis). Whether or not grade IV should be limited to IDH-mutant astrocytoma with CDKN2A homozygous deletion and thus a grade III be applied to malignant IDH-mutant astrocytomas that do not exhibit CDKN2A homozygous deletion despite the presence of MVP and/or necrosis is questionable. Regarding the group of IDH-mutant astrocytomas without CDKN2A homozygous deletion or MVP (or necrosis), another major problem is the prognostic relevance of mitotic activity used to distinguish grade II from grade III. The mitotic activity threshold is not provided by the WHO classification and remains subjective depending on the size of the sample analyzed. Importantly, previous studies reported that mitotic activity was not relevant for outcome among IDH-mutant astrocytomas.3,25 In addition, in the present study we failed to find a threshold for either mitotic count or Ki67 labeling index that could be of prognostic significance among our cohort of AA IDH mutant. Whether a grade II should be considered for all IDH-mutant astrocytoma lacking CDKN2A homozygous deletion and MVP (or necrosis) represents another matter of debate.

Of major interest, our study points out that a similar approach might be applied to AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted. Indeed, these tumors also demonstrate a dismal prognosis when CDKN2A homozygous deletion is recorded. Of note, in our cohort the prognosis of AO IDH mutant + 1p/19q codeleted with CDKN2A homozygous deletion was close to or even worse than that of GB IDH mutant (Fig. 1B). Even though a grade IV in oligodendrogliomas has never been suggested before, this genetic alteration might be taken into account to stratify these patients. Regarding histologic criteria, recent studies reported a prognostic relevance of WHO grade,12 whereas other authors reported that grades II and III oligodendrogliomas share the same prognosis.13 Our results suggest a stratification of AO without CDKN2A homozygous deletion or the presence of MVP and/or necrosis but (i) the observation period (<120 mo) may not be long enough and (ii) our cohort does not include grade II oligodendroglioma, avoiding prognostic comparison. Whether oligodendroglioma without CDKN2A homozygous deletion or MVP and necrosis shares a similar prognosis regardless of the number of mitoses remains to be confirmed by further investigations.

To conclude, in our study, performed on 911 malignant diffuse gliomas, IDH mutant included in the POLA cohort points out the utmost relevance of CDKN2A homozygous deletion as an adverse prognostic factor in 2 broad categories of patients stratified on 1p/19q codeletion as well as the prognostic relevance of MVP (associated or not with necrosis) among tumors lacking this alteration. Further studies, however, are required to confirm these findings, as well as the best technique to point out this genetic alteration. Nevertheless, we believe that these prognostic factors could be of great interest for a future grading approach of IDH-mutant gliomas.

Funding

This work is funded by the French Institut National du Cancer (INCa) and is part of the national program Cartes d’Identité des Tumeurs (CIT) (http://cit.ligue-cancer.net/), which is funded and developed by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship statement. Data collection and pathological and molecular analysis: CD, CAM, KM, DFB, AK, YM, NT. Analysis and interpretation of the data: RA, CC, ET, DFB. All authors were involved in the writing of the manuscript and have read and approved the final version.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ARTC-Sud patients’ association (Association pour le Recherche sur les Tumeurs Cérébrales), the Cancéropôle PACA and the SIRIC “CURAMUS” project. We would like to thank Raynier Devillier for the random forest variable importance analysis. Frozen specimens from the APHM institution were stored then provided by the APHM CRB-TBM tumor bank (authorization number AC-2018-31053, B-0033-00097). Frozen specimens from Bordeaux were stored in hôpital Haut Levèque CRB, 33604, Pessac, France. Frozen specimens from Montpellier were stored in CHU Montpellier, CCBH-M, 34825, Montpellier, France. Frozen specimens from Nantes were stored in IRCNA tumor bank, in CHU Nantes, Institut de Cancérologie de l’ouest, 44800 Saint-Herblain, France. Frozen specimens from Saint-Etienne were stored in CHU Saint-Etienne, CRB 42, 42055 Saint-Etienne, France. Frozen specimens from Lyon were stored in NeuroBioTec, Groupement Hospitalier Est, 69677 Bron cedex, France.

Contributor Information

POLA Network:

C Desenclos, H Sevestre, P Menei, A Rousseau, T Cruel, S Lopez, M-I Mihai, A Petit, C Adam, F Parker, P Dam-Hieu, I Quintin-Roué, S Eimer, H Loiseau, L Bekaert, F Chapon, D Ricard, C Godfraind, T Khallil, D Cazals-Hatem, T Faillot, C Gaultier, M C Tortel, I Carpiuc, P Richard, W Lahiani, H Aubriot-Lorton, F Ghiringhelli, C A Maurage, C Ramirez, E M Gueye, F Labrousse, O Chinot, L Bauchet, V Rigau, P Beauchesne, G Gauchotte, M Campone, D Loussouarn, D Fontaine, F Vandenbos-Burel, A Le Floch, P Roger, C Blechet, M Fesneau, A Carpentier, J Y Delattre, S Elouadhani-Hamdi, M Polivka, D Larrieu-Ciron, S Milin, P Colin, M D Diebold, D Chiforeanu, E Vauleon, O Langlois, A Laquerriere, F Forest, M J Motso-Fotso, M Andraud, G Runavot, B Lhermitte, G Noel, S Gaillard, C Villa, N Desse, C Rousselot-Denis, I Zemmoura, E Cohen-Moyal, E Uro-Coste, and F Dhermain

POLA Network

Amiens (C. Desenclos, H. Sevestre), Angers (P. Menei, A. Rousseau), Annecy (T. Cruel, S. Lopez), Besançon (M-I. Mihai, A. Petit), Bicêtre (C. Adam, F. Parker), Brest (P. Dam-Hieu, I. Quintin-Roué), Bordeaux (S. Eimer, H. Loiseau), Caen (L. Bekaert, F. Chapon), Clamart (D. Ricard) Clermont-Ferrand (C. Godfraind, T. Khallil), Clichy (D. Cazals-Hatem, T. Faillot), Colmar (C. Gaultier, M. C. Tortel), Cornebarrieu (I. Carpiuc, P. Richard), Créteil (W. Lahiani), Dijon (H. Aubriot-Lorton, F. Ghiringhelli), Lille (C. A. Maurage, C. Ramirez), Limoges (E. M. Gueye, F. Labrousse), Marseille (O. Chinot), Montpellier (L. Bauchet, V. Rigau), Nancy (P. Beauchesne, G. Gauchotte), Nantes (M. Campone, D. Loussouarn), Nice (D. Fontaine, F. Vandenbos-Burel), Nimes (A. Le Floch, P. Roger) Orléans (C. Blechet, M. Fesneau), Paris (A. Carpentier, J. Y. Delattre [POLA Network National coordinator], S. Elouadhani-Hamdi, M. Polivka), Poitiers (D. Larrieu-Ciron, S. Milin), Reims (P. Colin, M. D. Diebold), Rennes (D. Chiforeanu, E. Vauleon), Rouen (O. Langlois, A. Laquerriere), Saint-Etienne (F. Forest, M. J. Motso-Fotso), Saint-Pierre de la Réunion (M. Andraud, G. Runavot), Strasbourg (B. Lhermitte, G. Noel), Suresnes (S. Gaillard, C. Villa), Toulon (N. Desse), Tours (C. Rousselot-Denis, I. Zemmoura), Toulouse (E. Cohen-Moyal, E. Uro-Coste), Villejuif (F. Dhermain)

References

- 1. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Brat DJ, Verhaak RGW, et al. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olar A, Wani KM, Alfaro-Munoz KD, et al. IDH mutation status and role of WHO grade and mitotic index in overall survival in grade II-III diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(4):585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pekmezci M, Rice T, Molinaro AM, et al. Adult infiltrating gliomas with WHO 2016 integrated diagnosis: additional prognostic roles of ATRX and TERT. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2017;133(6):1001–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reuss DE, Mamatjan Y, Schrimpf D, et al. IDH mutant diffuse and anaplastic astrocytomas have similar age at presentation and little difference in survival: a grading problem for WHO. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):867–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K, et al. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shirahata M, Ono T, Stichel D, et al. Novel, improved grading system(s) for IDH-mutant astrocytic gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(1):153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reis GF, Pekmezci M, Hansen HM, et al. CDKN2A loss is associated with shortened overall survival in lower-grade (World Health Organization grades II-III) astrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74(5):442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roy DM, Walsh LA, Desrichard A, et al. Integrated genomics for pinpointing survival loci within arm-level somatic copy number alterations. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(5):737–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korshunov A, Casalini B, Chavez L, et al. Integrated molecular characterization of IDH-mutant glioblastomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2019;45(2):108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cimino PJ, Holland EC. Targeted copy number analysis outperforms histological grading in predicting patient survival for WHO grade II/III IDH-mutant astrocytomas. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(12):819–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cimino PJ, Zager M, McFerrin L, et al. Multidimensional scaling of diffuse gliomas: application to the 2016 World Health Organization classification system with prognostically relevant molecular subtype discovery. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aoki K, Nakamura H, Suzuki H, et al. Prognostic relevance of genetic alterations in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(1):66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alentorn A, Dehais C, Ducray F, et al. ; POLA Network Allelic loss of 9p21.3 is a prognostic factor in 1p/19q codeleted anaplastic gliomas. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1325–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tabouret E, Nguyen AT, Dehais C, et al. ; for POLA Network Prognostic impact of the 2016 WHO classification of diffuse gliomas in the French POLA cohort. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(4):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaloshi G, Benouaich-Amiel A, Diakite F, et al. Temozolomide for low-grade gliomas: predictive impact of 1p/19q loss on response and outcome. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1831–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ishwaran H, Gerds TA, Kogalur UB, Moore RD, Gange SJ, Lau BM. Random survival forests for competing risks. Biostatistics. 2014;15(4):757–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cairncross JG, Wang M, Jenkins RB, et al. Benefit from procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in oligodendroglial tumors is associated with mutation of IDH. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274(5293):1672–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 1993;366(6456):704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stott FJ, Bates S, James MC, et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14(ARF), participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998;17(17):5001–5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Purkait S, Jha P, Sharma MC, et al. CDKN2A deletion in pediatric versus adult glioblastomas and predictive value of p16 immunohistochemistry. Neuropathology. 2013;33(4):405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen A, Sato M, Aldape K, et al. DNA copy number analysis of grade II-III and grade IV gliomas reveals differences in molecular ontogeny including chromothripsis associated with IDH mutation status. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duregon E, Bertero L, Pittaro A, et al. Ki-67 proliferation index but not mitotic thresholds integrates the molecular prognostic stratification of lower grade gliomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7(16):21190–21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.