Abstract

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), extracellular matrix molecules that increase dramatically following a variety of CNS injuries or diseases, have long been known for their potent capacity to curtail cell migrations as well as axon regeneration and sprouting. The inhibition can be conferred through binding to their major cognate receptor, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Sigma (PTPσ). However, the precise mechanisms downstream of receptor binding that mediate growth inhibition have remained elusive. Recently, CSPGs/PTPσ interactions were found to regulate autophagic flux at the axon growth cone by dampening the autophagosome-lysosomal fusion step. Because of the intense interest in autophagic phenomena in the regulation of a wide variety of critical cellular functions, we summarize here what is currently known about dysregulation of autophagy following spinal cord injury, and highlight this critical new mechanism underlying axon regeneration failure. Furthermore, we review how CSPGs/PTPσ interactions influence plasticity through autophagic regulation and how PTPσ serves as a switch to execute either axon outgrowth or synaptogenesis. This has exciting implications for the role CSPGs play not only in axon regeneration failure after spinal cord injury, but also in neurodegenerative diseases where, again, inhibitory CSPGs are upregulated.

Keywords: PTPσ, Autophagy, Autophagic flux, Axon Regeneration, Lysosome, CSPGs, Spinal Cord Injury, Growth Cone, Axonal Dystrophy, Neural Plasticity, Synaptogenesis, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

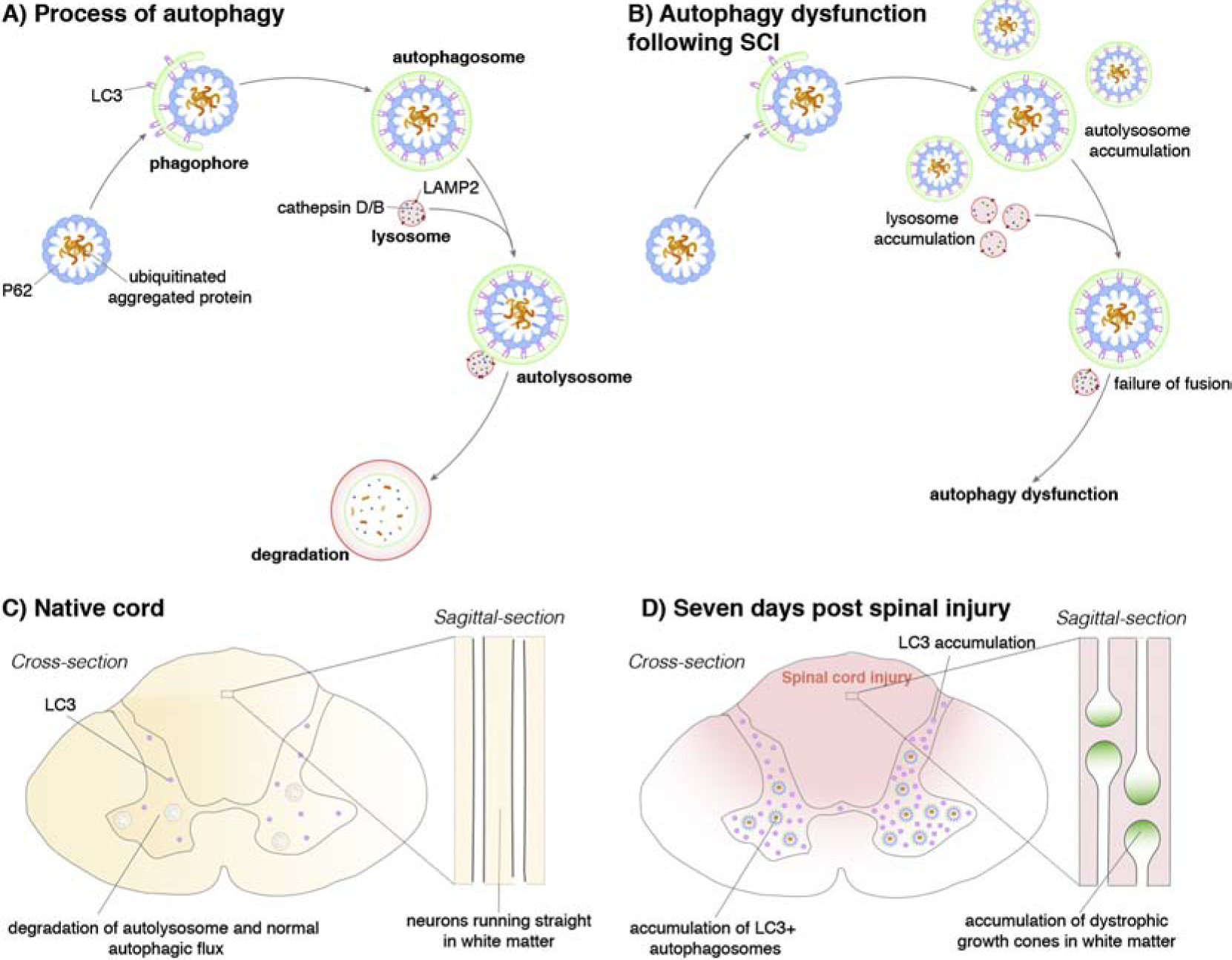

Autophagy is a ubiquitous, complex phenomenon interlocked with various signaling cascades to vitally influence essentially every aspect of cellular homeostasis. Canonical (microautophagy, macroautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy) and non-canonical autophagic pathways have been best characterized in S. cerevisiae yeast where they were first reported as nutrient-sensing mechanisms, allowing execution of a catabolic process in response to cellular starvation (Harding, 1995; Thumm et al., 1994; Tsukada and Ohsumi, 1993). Macroautophagy (referred to as “autophagy”) involves the multistep formation and maturation of a special form of membrane vesicles that arise from the engulfment of cellular materials. Upon activation of autophagy, proteins destined for degradation are encapsulated by a phagophore and sequestered in a double-membrane autophagosome. A full sequence of autophagy is completed when the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome (autolysosome) and the cargo is degraded by lysosomal proteases (Figure 1A; see Dikic and Elazar, 2018 for review).

Figure 1:

A schematic depiction of the process of macroautophagy (‘autophagy’) before and after spinal cord injury (SCI). A) Following initiation of autophagy in an uninjured spinal cord, the cytoplasmic cargo is engulfed, initially through the ‘C’ shaped phagophore and ultimately by the autophagosome. This structure fuses with acidic lysosomes (which contain cathepsin D/B and LAMP2 receptors), forming autolysosomes, where the cytoplasmic material is broken down. Highlighted is the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 protein (LC3) which can bind to cargo receptors, aiding autophagosome formation, causing accumulation of both molecules and ultimately autophagy dysfunction. B) Following SCI, lysosomes show decreased levels of cathepsin D/B and LAMP2 receptors. Autolysosome formation does not occur due to the failure of lysosome and autophagosome fusion. C) Schematic depicting the human spinal cord showing correct autophagic processes occurring within the grey matter. D) However, 7 days following SCI (red) there is a buildup of LC3+ autophagosomes and LC3 showing the breakdown of the autophagic process. This is especially prevalent in the growth cones of axons, causing accumulation of dystrophic end bulbs (also known as dystrophic growth cones, insert).

Autophagy interacts with major cellular signaling mechanisms that are intimately involved with a variety of processes such as metabolic regulation, protein quality control, immune function and cell death, as well as other cellular homeostatic pathways. Among post-mitotic cells, such as neurons, autophagy plays an imperative role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and the health of cells that have especially exuberant amounts of membrane. Autophagic dysregulation can be broadly defined as an imbalance of induction and/or reduced autophagic efficiency due to impaired lysosomal degradation that may result in an accumulation of intermediary constituents. Thus, like a factory assembly line, blockage of any part of the pathway will impair the entire process, potentially leading to severe consequences. For example, in older individuals, impaired autophagic induction has been implicated in age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (Cuervo, 2008; Finkbeiner, 2019). Unbalanced autophagic flux at any age can negatively impact cancer progression, bacterial infection, heart disease, autoimmune diseases, neurodegeneration (Dikic and Elazar, 2018) and, of particular interest for this review, axonal regeneration or sprouting after CNS injury.

Recent work has revealed that Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Sigma (PTPσ) - a transmembrane receptor responsible for the regeneration/sprouting inhibitory actions of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs see below) - plays a critical role in regulating autophagic flux in the dystrophic growth cone following spinal cord injury (SCI) (Sakamoto et al., 2019). This finding pinpoints CSPGs as an extracellular modulator of autophagy with enormous implications for how we view SCI and neurodegenerative diseases associated with upregulated CSPGs. Here, we discuss what is currently known about autophagy following SCI, recent findings on how CSPGs and their cognate receptor regulate autophagy, and the implications for the control of neuronal plasticity, axon regeneration, and synaptogenesis.

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Dysregulates Autophagy

In rodent models of contusive SCI, autophagy becomes dysregulated one to three days post injury as reflected by a general increase in cleaved microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (Atg8 or LC3) detected through western blots of the lesioned spinal cord (Liu et al., 2015). Neuronal autophagy remains dysregulated for at least a week before attempts are made to recover towards pre-injury levels (Liu et al., 2015). The cleaved status of LC3 is frequently utilized as a convenient indicator of autophagosome pool size. Thus, either the enhancement of its synthesis or decreased degradation of the pro-form of LC3 is involved in the formation of autophagosomes. The processed form of LC3 is associated with matured autophagosomes (Klionsky et al., 2016). Munoz-Galdeano et al. (Muñoz-Galdeano et al., 2018) showed that after SCI, LC3 immunostaining was increased in neurons and along axons including their end bulbs. This change could indicate an increase of autophagic flux – that is, the rate of autophagosome degradative activity. However, an increase of LC3 could also indicate an enhancement of autophagy initiation or the accumulation of immature and mature autophagic vesicles. To better contextualize the increase of LC3 immunostaining, Munoz-Galdeano et al. (Muñoz-Galdeano et al., 2018), also investigated markers involved in the regulation of autophagic initiation such as Beclin 1, which remained stable following injury. Most notably, an accumulation of p62 (or SQSTMI), an adaptor protein associated with autophagic activation and apoptosis, was detected around a week following injury, suggesting an accumulation of autophagosomes at this stage (Liu et al., 2015). Coupled with a noted decrease in the lysosomal protease, cathepsin D, and lysosome membrane-associated protein, LAMP2, which chronically persists following SCI (Liu et al., 2015), it appears that autophagosomes may be accumulating without completing the lysosomal fusion step in damaged neural tissue. Indeed, an elegant study from Sakamoto et al. (and more fully described later) suggests that a special sugar motif on CSPGs, which increases after cord injury and binds with high affinity to PTPσ, inhibits autophagosomes from fusing with lysosomes and severely affects protein turnover (Sakamoto et al., 2019).

In the normal cord, basal autophagy is different among neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (Muñoz-Galdeano et al., 2018); however after SCI, all three cell types increase expression of LC3. Thus, the dysregulation of autophagy following SCI has broad implications for injury progression including altering remyelination, neuroinflammation and neuroprotection (H.-C. Chen et al., 2013). Disruption of autophagy up to one week following SCI additionally correlates with neuronal and glial apoptosis (Tran et al., 2018b). Interestingly, treatment of SCI with drugs broadly activating autophagic flux (ex. mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin (Fan et al., 2018) and metformin(Zhang et al., 2016) attenuates pro-inflammatory cytokine expression while treatment with autophagic inhibitors such as 3-methyladenine, a PI3K inhibitor that blocks autophagosome formation, have increased neuroinflammation after injury (Meng et al., 2018). In a model of traumatic brain injury where autophagy is also dysregulated (Sarkar et al., 2015), indirectly increasing autophagy through rapamycin-mediated mTORC1 inhibition resulted in attenuated glial scar formation (Fan et al., 2018). Likewise, indirectly activating autophagy through treatments with metformin and other drugs conferred neuroprotection by decreasing neuronal apoptosis after SCI (Gao et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2019). For a comprehensive list of autophagic activators and inhibitors, see Yang et al. (Y.-P. Yang et al., 2013)

Chronically, autophagic dysregulation affects functional recovery following SCI. Blocking autophagy through conditional deletion of the autophagy gene Atg5 in oligodendrocytes, for example, significantly reduced hind limb recovery in SCI mice (Saraswat Ohri et al., 2018) while rapamycin treatment improved remyelination in explant cultures from neuropathic mice (Rangaraju et al., 2010). Moreover, several groups have shown that treatment after SCI with rapamycin or other autophagy-stimulating therapeutics such as Resveratrol enhances functional recovery (J. Chen et al., 2018; Nie et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). Restoring autophagic flux following SCI may be enhancing functional recovery at the level of the axon since autophagy is an intrinsic pathway responsible for axonal homeostasis as well as outgrowth. Loss of the autophagy associated protein Atg7, for example, has been implicated in producing axonal swelling and progressive dystrophy ultimately manifesting as degeneration of axon terminals (Deng et al., 2017; Komatsu et al., 2007). Conversely, He et al. observed that induction of autophagy using a synthetic peptide stabilizes microtubules to enhance axon regeneration as assessed by cortical spinal tract tracing following SCI (He et al., 2016). Indeed, microtubule stabilization is a well-characterized strategy to enhance axon outgrowth after SCI (Hellal et al., 2011; Ruschel et al., 2015).

Repairing dysregulated autophagy following CNS injury, however, requires more than therapeutically enhancing its induction alone. Too strongly upregulating autophagic induction in specific cells that are prone to inefficient autophagic flux, such as during dampened lysosomal function, causes autophagic stress with deleterious downstream cellular signaling affecting metabolism and, potentially, cellular apoptosis. Autophagy is ubiquitous and its regulation of cell pathways is cell-type and context-dependent. This helps to explain why both impaired or enhanced functional outcomes can occur following the administration of therapeutics targeting autophagy in CNS injuries. In one such example, enhancing autophagy in endothelial cells and immune cells has been noted to worsen neuroinflammation after injury by stimulating the production of pro-inflammatory fibrotic scar components (T. Zhou et al., 2019). Although stimulating autophagy has been found to increase neuroprotection after several types of CNS injuries including TBI, stroke, and ischemia-reperfusion injury (Yin et al., 2017), boosting autophagy has also been found to play a role in enhancing apoptosis in some SCI studies (Chen et al., 2014). In contrast, several research groups have found that inhibiting autophagy with chloroquine (an endosomal acidification inhibitor) or other indirect methods, reduced neuroinflammation and aided in functional recovery following CNS injuries (Wang et al., 2018; F. Wu et al., 2018). Strengthening this process in immune cells such as T-cells, for example, can augment their inflammatory function (Chang et al., 2010). Due to its crosstalk with immune, inflammatory (see Cadwell, 2016), and apoptotic signaling processes, enhancing autophagy may facilitate the activation of apoptotic or necrotic pathways to induce autophagic cell death (see Doherty and Baehrecke, 2018). Autophagy, therefore, requires tight regulation and coordination of each major phase of the pathway in specific cells to regulate regeneration in the context of CNS injuries. Fan et al., for example, have found that a large dose of rapamycin following TBI worsened hindlimb function while a moderate dose enhanced axon regeneration and function following injury (Fan et al., 2018). Moving forward, it will be important to fully dissect changes in autophagic dysregulation in different cell types following injury to better improve functional outcomes. The recent revelation that CSPGs are an autophagic regulator allows us to view SCI in a new light; specifically, of chronic axon regeneration failure and related SCI sequelae as a long-term issue with cellular homeostasis wrought by autophagic dysregulation.

CSPGs Dampen Autophagic Flux Through PTPσ: A critical new mechanism to explain regeneration failure

CSPGs and growth cone dystrophy following SCI

CSPGs within the nervous system comprise a key component of the ECM with each CSPG consisting of a core protein upon which chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan (CS-GAG) chains with repeating disaccharide units (between 20–220) are attached (Kjellen and Lindahl, 1991). They are well known to be potent inhibitors of cell and axonal migration as well as cell differentiation (Karimi-Abdolrezaee and Billakanti, 2012; Kuboyama et al., 2017; Wiese and Faissner, 2015; Zhong et al., 2019). Each disaccharide moiety within the CS-GAG chain may be differently sulfated (Properzi et al., 2003) from CS-A through CS-E which determine the specific binding patterns of the CS-GAGs with other molecules and, thus, the inhibitory properties of specific CSPGs within the ECM (Brown et al., 2012). CSPGs are normally enriched in specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structures called perineuronal nets (PNN) surrounding synaptic boutons upon a variety of neuronal sub-types throughout the CNS (Celio et al., 1998). Within the PNNs distal to a cord lesion, in regions that have undergone axotomy-induced deafferentation, CSPGs greatly upregulate (Alilain et al., 2011; Massey et al., 2006). In addition to matrix increases in the PNN, following injury to the spinal cord and subsequent inflammation, the glial scar forms with a gradient of CSPGs increasing from the penumbra toward the lesion epicenter (Davies et al., 1997; Tran et al., 2018b) inhibiting regeneration (Alilain et al., 2011; Bradbury et al., 2002; Warren et al., 2018). Thus, CSPGs increase rather expansively both near and far from the lesion which creates an environment that becomes largely restrictive to frank regeneration as well as local sprouting.

The growth cones of potentially regenerating axons after lesion become swollen in response to an increasing gradient of CSPGs (Y. Li and Raisman, 1995; Tom et al., 2004). First described by Ramon y Cajal in the injured spinal cord of the adult cat, these unusual dystrophic endings were referred to as “sterile clubs” that would eventually be eliminated (Cajal, 1959). However, modern live-imaging studies have since altered the idea that the dystrophic end bulb is inevitably targeted for death. Instead, dystrophic growth cones are initially highly dynamic structures that eventually become entrapped, some indefinitely (Ruschel et al., 2015), by their surrounding ECM. A useful tool to study this phenomenon in vitro has been the development of the spot assay, which takes advantage of the differing drying properties of aggrecan and laminin to create a reciprocal gradient in a coffee-ring like distribution (Tom et al., 2004; Yunker et al., 2011). Growth cones of adult dorsal root ganglion axons form classic dystrophic end bulbs within the gradient 44. Combined with time-lapse imaging, Tom et al.44 observed that these growth cones, for a time, actively extend and retract their finger-like filopodia and lamellipodia without any net forward movement. Continuous engulfment of membrane with large bubbles of cycling vesicles occurred in a subset of particularly swollen dystrophic growth cones. Dystrophic growth cones with similar large vesicles were detected by Cajal 46 and more recently at the tips of axons following SCI in rats (Davies et al., 1999; Filous et al., 2014; Tom et al., 2004). However, for many years, the underlying mechanisms that controlled the stalled behavior of dystrophic growth cones were unknown.

Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Sigma (PTPσ) is a CSPG Receptor

First cloned by the Schlessinger group in 1993, PTPσ was initially found to be enriched in rat brains (Yan et al., 1993) and has since been observed in a number of regions throughout the CNS and PNS with an important role in axon guidance during development (Schaapveld et al., 1998; Shen, 2014). In 1994, the Tremblay group generated a constitutive knockout mouse (Wagner et al., 1994), which exhibited some endocrinological abnormalities among other defects in the developing hypothalamo-pituitary axis (Elchebly et al., 1999). However, it took an additional decade before PTPσ would be appreciated as a tractable candidate for enhancing axonal regeneration following CNS injury. Shen et al. first revealed that PTPσ was the cognate receptor for the potent axonal growth inhibition mediated by CSPGs (Shen et al., 2009). PTPσ binds with highest affinity to the CS-E sulfation moieties of CSPGs (Brown et al., 2012; Sakamoto et al., 2019) which are highly upregulated following SCI (Yi et al., 2014).

PTPσ, along with LAR and PTPδ, are classified in the type IIA LAR subfamily of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (Chagnon et al., 2004). Like other receptor PTP subtypes, members of the LAR subfamily are transmembrane receptors with several discrete domains including two intracellular domains: the phosphatase active D1 domain and a phosphatase inactive D2 domain (Andersen et al., 2001; Chagnon et al., 2004) sandwiching a regulatory intracellular wedge domain (Oblander and Brady-Kalnay, 2010). Extracellularly, PTPσ includes a variable region of four to eight fibronectin type III repeats and three immunoglobulin domains depending on the alternatively spliced isoform (R Pulido et al., 1995). Notably, the immunoglobulin domain of the N-terminus of the receptor confers binding to both axon growth-permissive heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as well as inhibitory CSPG ligands (Coles et al., 2011). PTPσ is, therefore, a bifunctional receptor able to execute either axon growth inhibition or permissiveness depending on the immediate extracellular matrix milieu sensed by the growth cone.

Work from Coles et al. (Coles et al., 2011) has proposed that the uneven distribution of sulfated moieties of the GAG domain of HSPGs may promote PTPσ aggregation on the membrane of the growth cone with subsequent inhibition of intracellular phosphatase activity. Binding to CSPGs, however, promotes the monomeric conformation of the receptor and activation of its intracellular phosphatase activity. This hypothesis was recently validated by the Tremblay group using a split luciferase assay that monitored both PTPσ dimerization and phosphatase activity in live-cell assays (C.-L. Wu et al., 2017). While the immediate PTPσ intracellular binding partners conferring axon inhibition or outgrowth are still largely unknown, recent studies have suggested that the ERK (Kaplan et al., 2015; Lang et al., 2015) and Rho/ROCK pathways (Dyck et al., 2015) may be involved especially in the context of CSPG binding and downstream axonal inhibition.

Since its initial discovery and especially after it was found to be a CSPG receptor, PTPσ has become an attractive target to enhance axon outgrowth following injury. PTPσ knockout mice, for example, show enhanced axon regeneration in a variety of models of CNS injuries including spinal cord crush (Shen et al., 2009), contusive trauma (Fry et al., 2010), and optic nerve lesion (Sapieha et al., 2005). Knock out of PTPσ is also effective in enhancing regeneration in peripheral nerve injuries including after sciatic (McLean et al., 2002) and facial nerve crushes (Thompson et al., 2003). Moreover, our lab has illustrated the effectiveness of peptide modulation of PTPσ with ISP (Intracellular Sigma Peptide), which was designed as a blood brain barrier and cell membrane-penetrating peptide mimetic of the wedge domain of PTPσ to overcome CSPG-induced inhibition (Lang et al., 2015). Systemic injections of ISP relieve CSPG barriers and improve functional recovery in a variety of injury models involving axons, including sympathetic nerve re-innervation of the forming CSPG-enriched scar following myocardial infarction (Gardner and Habecker, 2013), functional recovery following spinal root avulsion (H. Li et al., 2015), and sprouting of serotonergic neurons with locomotor and bladder recovery following contusive SCI (Lang et al., 2015; Rink et al., 2018). Recent work examining CSPG and PTPσ convergence on autophagic flux may reveal how CSPGs further inhibit regeneration following CNS injury and how targeting PTPσ may ameliorate this inhibition to enhance outgrowth at the level of the growth cone.

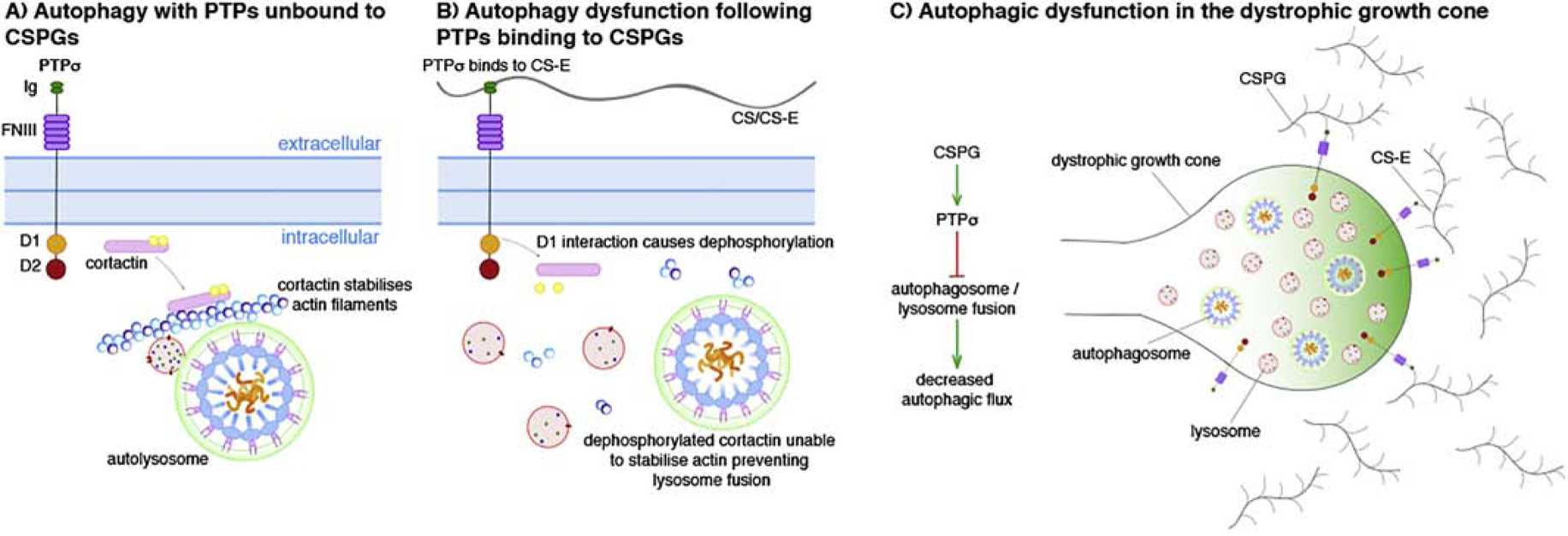

PTPσ is a Regulator of Autophagosome-Lysosomal Fusion

Martin et al. first identified PTPσ as a regulator of autophagic flux following an RNAi screen in 2011 and found that RNAi-mediated knockdown or constitutive knockout of PTPσ induced autophagic hyperactivity with increased autophagic vesicle abundance in an eGFP-LC3 cell line (Martin et al., 2011). New and pioneering work from the Kadomatsu group (Sakamoto et al., 2019) directly links CSPGs acting through PTPσ in the regulation of autophagy. They found that the rare sugar motif on CSPGs, the CS-E sulfation pattern, binds with highest affinity to PTPσ on axonal growth cones and that this binding, in turn, monomerizes the receptor and disrupts autophagic flux specifically at the autophagosome-lysosome fusion step (Sakamoto et al., 2019). In addition, they found that the CSPG-induced catalytic activity of the D1 domain of PTPσ dephosphorylates residue Y421 of cortactin, an actin-binding protein implicated in providing the actin infrastructure to enable autophagosome and lysosomal fusion. Activation of PTPσ by CSPGs therefore prevents local autophagosome and lysosomal fusion through dephosphorylation of cortactin (Figure 2). This finding links extracellular CSPGs to regulation of autophagic flux. Using the spot assay, Sakamoto et al. additionally found that axons caught in a CSPG gradient accumulate unfused lysosomes and autophagic vesicles in large bleb-like structures. This recalls to mind the bubbling vesicles in dystrophic end bulbs formed by axons originally documented by Ramon y Cajal (Cajal, 1959) and live-imaged by Tom et al (Tom et al., 2004). Indeed, engulfment of cell surface membrane involves autophagic proteins and lysosomal degradation in a process known as macroendocytic engulfment (Florey and Overholtzer, 2012). Importantly, disrupting autophagy/lysosomal fusion through knockdown of cortactin or with autophagic inhibitors choloroquine and bafilomycin-A was sufficient to induce classic dystrophic growth cones (Sakamoto et al., 2019) while modulation of PTPσ with ISP restored autophagic flux and switched dystrophic endings into normally migrating growth cones(Lang et al., 2015; Sakamoto et al., 2019). Further evidence suggests that inhibiting autophagy in peripheral neurons reduces neurite outgrowth in vitro (Clarke and Mearow, 2016) while in unusual animals with normally higher baselines of autophagy such as the naked mole rat, some axon regeneration (after optic nerve crush) can occur spontaneously even in the adult (Park et al., 2017). Thus, CSPGs acting through PTPσ may be inhibiting axon regeneration following CNS injury by dampening autophagy/lysosomal fusion and impairing downstream growth cone homeostasis.

Figure 2:

Schematic depicting how protein tyrosine phosphate sigma (PTPσ) and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG) binding can decrease autophagic flux through the stabilization of actin filaments. A) When unbound to CSPGs, the D1 domain of PTPσ does not interact with cortactin meaning that the molecule is still phosphorylated and acts to stabilize the actin filaments to enable autophagosome and lysosomal fusion. B) The binding of PTPσ with chondroitin sulfate-E (CS-E) causes the D1 domain to dephosphorylate residue Y421 of cortactin. This prevents the molecule from stabilizing actin and thus lysosome fusion causing autophagic dysfunction. C) Within the dystrophic growth cone, the prevention of autophagosome/lysosome fusion following the binding of PTPσ with CS-E causes a decrease in autophagic flux.

CSPGs/PTPσ and regulation of the autophagy/lysosomal axis

Recent work from our lab implicates increases in the lysosomal enzyme, cathepsin B, as a protease of interest in CSPG-induced dystrophic dorsal root ganglion axons following PTPσ modulation by the receptor blocking peptide, ISP (Tran et al., 2018a). This may occur through ISP modulation of PTPσ and subsequent dis-inhibition of cortactin, which in addition to regulating autophagosome and lysosomal fusion, has been implicated as an essential regulator of protease secretion (Clark et al., 2007; Schnoor et al., 2018). This is significant because the regulation of lysosomal proteases such as cathepsin B is vital for regular lysosomal function including protein degradation and turnover (J. Zhou et al., 2013). This enzyme is also critical in maintaining autophagic flux as it is integral to the last step of the process where autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to fully degrade their vesicular contents (Sasaki and Yoshida, 2015). Following SCI, a related lysosomal protease, cathepsin D decreases (Liu et al., 2015) and generally perturbed lysosomal function following SCI may potentiate necroptosis (Liu et al., 2018). Moreover, inhibited or reduced cathepsin activity through Ca074-me or overexpression of its endogenous inhibitor such as cystatin B, have been reported to impair autophagy (Lamore and Wondrak, 2011; Soori et al., 2016; Tatti et al., 2012) or enhance lysosomal dysfunction (Mizunoe et al., 2017). Normal lysosomal function is necessary for axonal outgrowth as reducing or inhibiting cathepsins impair axon migration (Boonen et al., 2016). Lysosomal dysfunction alone has been implicated in axonal dystrophy similar to that seen in Alzheimer’s Disease where cargo transport is disrupted and LC3-positive swellings develop along the length of axons (Lee et al., 2014; 2011). Genetic mutations targeting proteins crucial for normal lysosomal function have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Fronto-Temporal Dementia (Klein et al., 2017), Tay-Sachs Disease (Dersh et al., 2016) and Niemann-Pick type C disease (Hammond et al., 2019) among others (see Ferreira and Gahl, 2017).

As PTPσ has been discovered to regulate fusion of the autophagosome with lysosomes (Sakamoto et al., 2019) as well as levels of cathepsin B in neurons (Tran et al., 2018a), CSPGs may play a larger role in lysosomal function than previously realized. This has greater implications for the role that CSPGs play in neurodegeneration since CSPGs are upregulated in the ECM of a variety of neurodegenerative diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis, where they block the migration and remyelinating potential of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Keough et al., 2016; Mohan et al., 2010; Niknam et al., 2019; Siebert et al., 2011). In fact, Bankston et al. recently identified the necessity of Atg5 and autophagy in oligodendrocyte differentiation, survival, and myelination (Bankston et al., 2019). Restoring autophagic flux may be one mechanism underlying oligodendrocyte survival, differentiation, enhanced myelination, and ultimately enhanced locomotor function in models of Multiple Sclerosis following PTPσ modulation with ISP (Luo et al., 2018). CSPGs are gaining wider recognition in the detrimental roles they play in other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (DeWitt et al., 1993), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Mizuno et al., 2008), and stroke (Carmichael et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2014; Soleman et al., 2012), among others. Moving forward, it will be important to fully characterize the effects of CSPG/PTPσ interactions on regulation of autophagic and lysosomal function in the context of CNS injuries and neurodegenerative diseases.

CSPGs/PTPσ Regulate Plasticity Potentially Through Autophagic Regulation

CSPGs enriched in perineuronal nets have long been observed to play a role in maintaining both structural as well as activity-dependent plasticity. In a classic example of CSPGs’ impact on activity-dependent plasticity, Pizzorusso et al. showed that injections of chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) (a bacterially-derived glycosidase that specifically cleaves the GAG chains from CSPGs) in the adult visual cortex re-initiated a period of experience-dependent plasticity in adulthood (Pizzorusso et al., 2002). The effect of the enzyme in the adult was to essentially shift the cortex back to a more juvenile state, similar to that which exists prior to the end of the critical period for ocular dominance plasticity that normally closes with the formation of CSPGs in PNNs (Gogolla et al., 2009). Furthermore, ChABC digestion of GAG chains of the PNN in E18 hippocampal neurons cultured in vitro increases the number of synaptic puncta coimmunolabeled with bassoon, ProSAP1, and Shank2 with concomitant functional changes on firing characteristics assayed through electrophysiological recordings (Favuzzi et al., 2017; Pyka et al., 2011). ChABC injections have also been linked to alterations in LTP, and ultimately, functional memory tasks (Banerjee et al., 2017; Gogolla et al., 2009). In fact, ChABC treatment of several mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease has yielded improvements in neural plasticity and memory function. P301S tau mutants, for example, show complete loss of novel object memory that is reversible following bilateral ChABC injections into the perirhinal cortex (S. Yang et al., 2015). Moreover, APP mutants, which develop memory defects concomitantly with amyloid plaques, preserve the ability to differentiate contextual memory and long term potentiation following hippocampal ChABC injections (Végh et al., 2014). Altogether, this suggests that CSPGs enriched in PNNs play an important role in limiting neural plasticity both in development and adulthood after injury or disease.

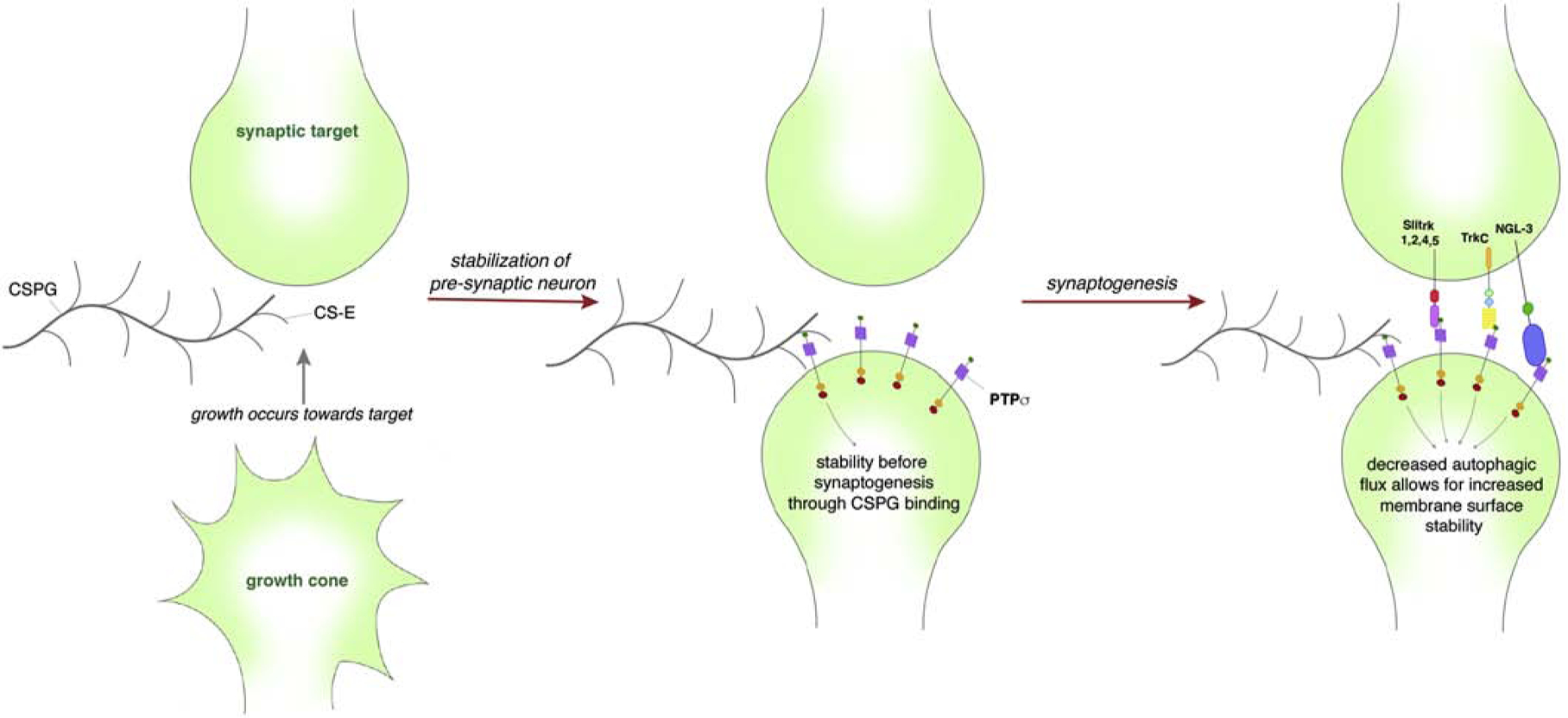

In part, the effects of CSPGs on synaptogenesis may be due to signaling events instigated through CSPG-PTPσ interactions (Figure 3). Importantly, members of the LAR family of receptors have been described as presynaptic hub-like receptors that organize synapse complexes by binding to multiple postsynaptic adhesion partners to propel synapse self-assembly (Takahashi and Craig, 2013). Recently, Bomkamp et al. found that PTPσ binds to liprin-α to initiate presynaptic differentiation (Bomkamp et al., 2019). Moreover, PTPσ itself has been found to cooperatively bind to cell-cell adhesion and synaptogenic proteins such as neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) (Han et al., 2016), netrin-G ligand-3 (NGL-3) (Kwon et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2009), and Tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk)-C (Takahashi et al., 2011). In select excitatory synapses, PTPσ initiates synaptic organization first by mediating cell-cell adhesion at burgeoning synapses to stabilize this nascent structure (Takahashi and Craig, 2013). LAR and Slitrk are additionally involved in this stabilizing process (Um et al., 2014). PTPσ, through interactions with TrkC and related proteins, then initiates bi-directional synaptic differentiation that locally recruits the necessary synaptic machinery including scaffolds and other signaling proteins for de novo synaptogenesis to proceed (Dunah et al., 2005; Takahashi and Craig, 2013). Specifically, TrkC and PTPσ binding, with the addition of NT-3 modulation, induces preand postsynaptic differentiation in a kinase-independent manner to increase vesicle recycling and NMDA receptor and PSD-95 clustering (Naito et al., 2017; Takahashi et al., 2011). Notably, TrkC binds to PTPσ and not to LAR or PTPδ and requires PTPσ-specific signal transduction to initiate synaptic differentiation (Takahashi et al., 2011). Knockdown of TrkC additionally reduced PSD-95 puncta and altered post-synaptic miniature excitatory frequency (Naito et al., 2017), while PTPσ knockout animals have been found to exhibit deficits in paired pulse facilitation and long term potentiation (Horn et al., 2012), further strengthening the role that PTPσ plays in synaptogenesis.

Figure 3:

Schematic depicting how PTPσ-CS-E binding can affect synaptogenesis through the regulation of autophagic flux. The approach of a growth cone has little binding of PTPσ with CSPGs. However, upon the approach of a target PTPσ to a CSPG-rich environment such as the perineuronal net, the decreased autophagic flux allows for increased membrane surface stability aiding synaptic assembly. Thereafter, PTPσ binds to SlitA, TrkC, NGL-3 to initiate bi-directional synaptic differentiation that locally recruits the necessary synaptic machinery for de novo synaptogenesis.

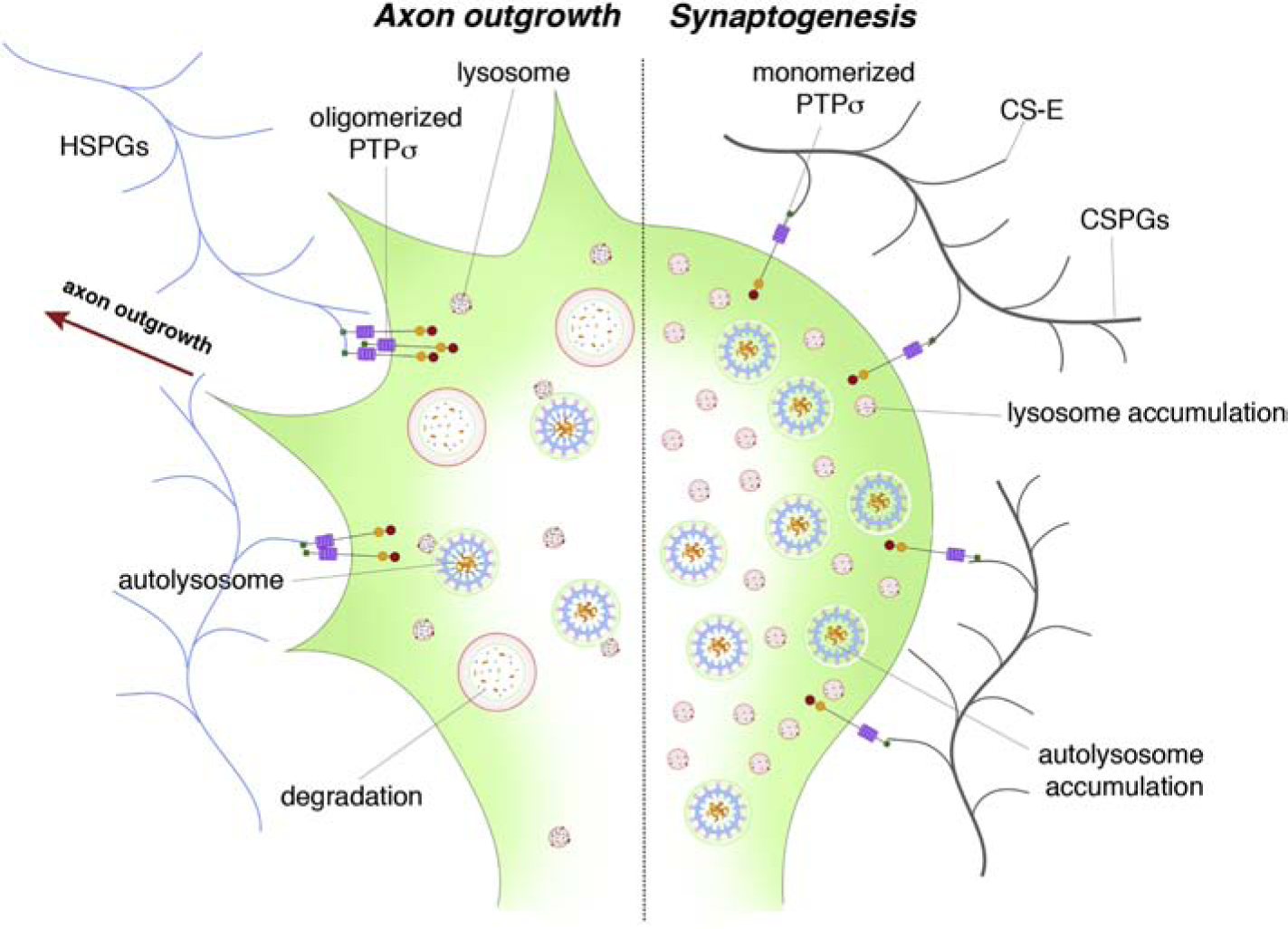

PTPσ is a Switch to Execute Axon Outgrowth or Synaptogenesis

As a CSPG and synaptogenesis hub receptor, how is PTPσ able to coordinate between axonal growth and synaptogenesis? We propose that PTPσ acts as a switch for axonal plasticity that exchanges axonal outgrowth for synaptogenesis (Figure 4). Indeed, Coles et al. have found that PTPσ binds to both HSPG and TrkC with widely different outcomes where binding to HSPG outcompeted TrkC binding to PTPσ to favor neurite outgrowth over synaptogenesis and vice versa (Coles et al., 2014). The idea that PTPσ acts as a switch for plasticity regulating axon extension or synaptogenesis has implications following injury in adulthood that may help to explain how regeneration may occur or fail. Indeed, the end state of the dystrophic growth cone in the spot assay is one where PTPσ becomes highly upregulated with the end bulb tightly adhered upon the substrate 45,66. In vivo, the terminally stalled condition of the dystrophic growth cone is now thought to be mediated through entrapment of the axonal end bulb through a synaptic-like stable bond with oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (or possibly pericytes) that produce the CSPG matrix within the lesion core (Busch et al., 2010; Filous et al., 2014). A similar synaptic-like adhesive interaction between non-regenerating sensory axons at the dorsal root entry zone after root crush has been described by the Son lab (Son, 2015). It is likely that this synaptic mechanism can help explain how dystrophic end bulbs can persist for many decades following SCI (Ruschel et al., 2015). This “adhesiveness” that CSPGs confer through PTPσ signaling may help to initially support any burgeoning synapse perhaps through downstream recruitment of scaffolds (Figure 3). Indeed, presynaptic PTPσ binding to postsynaptic adhesion-promoting proteins including NGL-3, NT-3 (Naito et al., 2017), and N-cadherin (Siu et al., 2006) are necessary for synaptogenesis.

Figure 4:

A schematic depicting how PTPσ binding may act as a switch to mediate axon outgrowth or synaptogenesis. Binding of PTPσ with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) causes axon outgrowth, potentially through the secretion of proteases. However, upon binding to CS-E and TrkC, the axon is able to form a synapse and stop axon outgrowth – the condition which occurs after SCI. This is partially mediated through the reduction in protease secretion and through the reduction of autophagic flux.

When axon outgrowth-promoting substrates outcompete CSPGs or when ChABC is injected, CSPG signaling through PTPσ is disrupted to result in a switch from stabilizing the growth cone to encouraging axon extension. Local protease secretion as previously observed (Krystosek and Seeds, 1984; McGuire and Seeds, 1990; Tran et al., 2018a) may additionally promote process elongation by digesting immediately surrounding CSPGs and other adhesion proteins to help initiate axon growth. However, once a regenerating growth cone meets its postsynaptic target, such as a soma enmeshed in a PNN or an OPC covered in the NG2 proteoglycan 51,124, the large increase of CSPGs could change the conformation of PTPσ, allowing for downstream signaling events to halt protease secretion. Continuous protease secretion could otherwise digest adhesive proteins and interfere with synaptogenesis at this critical stage.

Is there a Causal Relationship between CSPG/RPTPσ Adhesive Interactions during Synaptogenesis and Autophagic Regulation?

In addition to limiting protease secretion during the initial formation of synapses, CSPG binding to PTPσ may dampen autophagic flux normally during such highly adhesive presynaptic events, leading to reductions in the transport of synaptic-associated machinery, cytoplasmic materials, surface receptors, and other proteins into autophagosomes thereby decreasing their degradation by lysosomes. Using live-cell imaging of dorsal root ganglion neurons, Maday et al. have found that a baseline of autophagy does occur in axons undergoing synaptogenesis beginning with autophagosomes forming at presynaptic terminals that are then retrogradely transported to the soma (Maday and Holzbaur, 2014; Maday et al., 2012). By controlled reduction of autophagic flux and, thus, reducing the turnover of cell surface receptors among other proteins for degradation, CSPG-PTPσ interactions may be increasing surface stability once axons arrive at their potential synaptic sites. Conversely, Rowland et al. found that muscle GABA-A receptors lose their clustered morphology and are targeted selectively to increased numbers of autophagosomes in C. elegans when presynaptic inputs are lost (Rowland, 2006). Highly regulated modulation of autophagy is, therefore, emerging as a significant pathway required for synaptic plasticity in both structural remodeling as well as functional modification (see Liang, 2019). Glatigny et al. have found that autophagy is required for memory formation in the mouse hippocampus as induction of autophagy in hippocampal neurons enhanced activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Glatigny et al., 2019). Autophagy is, therefore, emerging as an important regulator of synaptic plasticity from synaptogenesis during development or on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the lesion core, to plasticity in adulthood, and memory decline in old age. We excitedly await future studies exploring how CSPGs and PTPσ contribute to this fine-tuning across the lifespan of a synapse.

Conclusions and Perspectives

CSPGs are beginning to gain greater recognition in the more endogenous roles they play in synaptic plasticity, memory formation, and neurodegenerative diseases beyond CNS injuries. Together, these findings are beginning to elucidate how CSPGs affect axon regeneration at the cellular level, how axonal dystrophy occurs, and generally how CSPGs can influence even normal neuronal homeostasis. These seemingly disparate findings on CSPGs in so many different areas of CNS homeostasis paint an image of CSPGs as an important regulator between synaptogenesis and axon outgrowth. After all, the goal of an emerging axon is to extend until it can innervate its target. PTPσ seems to be the molecular switch that allows for either program to occur, perhaps using autophagy to direct these molecular programs downstream.

In a spark of imaginative speculation, the late Roger Tsien had speculated that decades-old memories may very well be encoded in the specific pattern of holes formed by perineuronal nets (Tsien, 2013). While this intriguing prediction remains untested, questions inquiring about the basic relationship between the CSPGs of perineuronal nets, memory formation, and how they regulate plasticity in general are just beginning to be answered. Work in SCI has pitched CSPGs in a largely negative role after CNS injury; indeed, CSPGs confer chronic inhibition to any regenerating axon attempting to re-innervate its target. In a broader view, CSPGs are endogenous proteins intended to maintain circuit stability in adulthood. One could imagine that unchecked plasticity during adulthood at the synaptic level through ablation of CSPGs at perineuronal nets could potentially destabilize the nature of our neuronal connections and, ultimately, ourselves. Interrogating how to induce plasticity following injury in a controlled manner, however, through CSPG digestion or receptor modulation persists as a goal to attain optimal functional axonal plasticity and regeneration following SCI.

Highlights:

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) are upregulated after traumatic CNS injuries and neurodegenerative disorders.

Extracellular CSPGs bind to the bifunctional transmembrane receptor, protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma (PTPσ).

CSPGs were recently found to dampen autophagic flux through binding to PTPσ, which subsequently dephosphorylates cortactin to prevent autophagosome and lysosomal fusion.

As a regulator of autophagic flux, PTPσ may serve as a switch to execute either axon outgrowth or synaptogenesis with implications on axon plasticity after injury and neurodegenerative disorders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alilain WJ, Horn KP, Hu H, Dick TE, Silver J, 2011. Functional regeneration of respiratory pathways after spinal cord injury. Nature 475, 196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JN, Elson A, Lammers R, Rømer J, Clausen JT, Møller KB, Møller NP, 2001. Comparative study of protein tyrosine phosphatase-epsilon isoforms: membrane localization confers specificity in cellular signalling. Biochem. J 354, 581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SB, Gutzeit VA, Baman J, Aoued HS, Doshi NK, Liu RC, Ressler KJ, 2017. Perineuronal Nets in the Adult Sensory Cortex Are Necessary for Fear Learning. Neuron 95, 169–179.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankston AN, Forston MD, Howard RM, Andres KR, Smith AE, Ohri SS, Bates ML, Bunge MB, Whittemore SR, 2019. Autophagy is essential for oligodendrocyte differentiation, survival, and proper myelination. Glia 33, 3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomkamp C, Padmanabhan N, Karimi B, Ge Y, Chao JT, Loewen CJR, Siddiqui TJ, Craig AM, 2019. Mechanisms of PTPσ-Mediated Presynaptic Differentiation. Front. Synaptic Neurosci 11, 7517. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2019.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonen M, Staudt C, Gilis F, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Jadot M, 2016. Cathepsin D and its newly identified transport receptor SEZ6L2 can modulate neurite outgrowth. Journal of Cell Science 129, 557–568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.179374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LDF, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB, 2002. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 416, 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Xia J, Zhuang B, Cho K-S, Rogers CJ, Gama CI, Rawat M, Tully SE, Uetani N, Mason DE, Tremblay ML, Peters EC, Habuchi O, Chen DF, Hsieh-Wilson LC, 2012. A sulfated carbohydrate epitope inhibits axon regeneration after injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 4768–4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Hawthorne AL, Bai L, Miller RH, Silver J, 2010. Adult NG2+ Cells Are Permissive to Neurite Outgrowth and Stabilize Sensory Axons during Macrophage-Induced Axonal Dieback after Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neuroscience 30, 255–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3705-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell K, 2016. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling pathways: balancing defence and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol 16, 661–675. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajal SRY, 1959. Degeneration & Regeneration of the Nervous System. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Archibeque I, Luke L, Nolan T, Momiy J, Li S, 2005. Growth-associated gene expression after stroke: evidence for a growth-promoting region in peri-infarct cortex. Experimental Neurology 193, 291–311. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR, Spreafico R, De Biasi S, Vitellaro-Zuccarello L, 1998. Perineuronal nets: past and present. Trends in Neurosciences 21, 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnon MJ, Uetani N, Tremblay ML, 2004. Functional significance of the LAR receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase family in development and diseases. Biochem. Cell Biol 82, 664–675. doi: 10.1139/o04-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y-P, Tsai C-C, Huang W-C, Wang C-Y, Chen C-L, Lin Y-S, Kai J-I, Hsieh C-Y, Cheng Y-L, Choi P-C, Chen S-H, Chang S-P, Liu H-S, Lin C-F, 2010. Autophagy facilitates IFN-gamma-induced Jak2-STAT1 activation and cellular inflammation. J Biol Chem 285, 28715–28722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H-C, Fong T-H, Hsu P-W, Chiu W-T, 2013. Multifaceted effects of rapamycin on functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats through autophagy promotion, anti-inflammation, and neuroprotection. Journal of Surgical Research 179, e203–e210. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Yan L, Wang H, Zhang Z, Yu D, Xing C, Li J, Li H, Li J, Cai Y, 2018. ZBTB38, a novel regulator of autophagy initiation targeted by RB1CC1/FIP200 in spinal cord injury. Gene 678, 8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Z, FU Q, SHEN B, HUANG X, WANG K, HE P, LI F, Zhang F, SHEN H, 2014. Enhanced p62 expression triggers concomitant autophagy and apoptosis in a rat chronic spinal cord compression model. Mol Med Report 9, 2091–2096. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ES, Whigham AS, Yarbrough WG, Weaver AM, 2007. Cortactin Is an Essential Regulator of Matrix Metalloproteinase Secretion and Extracellular Matrix Degradation in Invadopodia. Cancer Res. 67, 4227–4235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J-P, Mearow K, 2016. Autophagy inhibition in endogenous and nutrient-deprived conditions reduces dorsal root ganglia neuron survival and neurite growth in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res 94, 653–670. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CH, Mitakidis N, Zhang P, Elegheert J, Lu W, Stoker AW, Nakagawa T, Craig AM, Jones EY, Aricescu AR, 2014. Structural basis for extracellular cis and trans RPTPσ signal competition in synaptogenesis. Nat Comms 5, 5209. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CH, Shen Y, Tenney AP, Siebold C, Sutton GC, Lu W, Gallagher JT, Jones EY, Flanagan JG, Aricescu AR, 2011. Proteoglycan-Specific Molecular Switch for RPTP Clustering and Neuronal Extension. Science 332, 484–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1200840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, 2008. Autophagy and aging: keeping that old broom working. Trends in Genetics 24, 604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Fitch MT, Memberg SP, Hall AK, Raisman G, Silver J, 1997. Regeneration of adult axons in white matter tracts of the central nervous system. Nature 390, 680–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Goucher DR, Doller C, Silver J, 1999. Robust regeneration of adult sensory axons in degenerating white matter of the adult rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci 19, 5810–5822. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Purtell K, Lachance V, Wold MS, Chen S, Yue Z, 2017. Autophagy Receptors and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Trends in Cell Biology 27, 491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersh D, Iwamoto Y, Argon Y, 2016. Tay–Sachs disease mutations in HEXA target the α chain of hexosaminidase A to endoplasmic reticulum–associated degradation. Molecular Biology of the Cell 27, 3813–3827. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt DA, Silver J, Canning DR, Perry G, 1993. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are associated with the lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental Neurology 121, 149–152. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I, Elazar Z, 2018. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 349–364. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty J, Baehrecke EH, 2018. Life, death and autophagy. Nature Cell Biology 20, 1110–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Hueske E, Wyszynski M, Hoogenraad CC, Jaworski J, Pak DT, Simonetta A, Liu G, Sheng M, 2005. LAR receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases in the development and maintenance of excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci 8, 458–467. doi: 10.1038/nn1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck SM, Alizadeh A, Santhosh KT, Proulx EH, Wu C-L, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, 2015. Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans Negatively Modulate Spinal Cord Neural Precursor Cells by Signaling Through LAR and RPTPsigma and Modulation of the Rho/ROCK Pathway. Stem Cells 33, 2550–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elchebly M, Wagner J, Kennedy TE, Lanctôt C, Michaliszyn E, Itié A, Drouin J, Tremblay ML, 1999. Neuroendocrine dysplasia in mice lacking protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma. Nat. Genet 21, 330–333. doi: 10.1038/6859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y-Y, Nan F, Guo B-L, Liao Y, Zhang M-S, Guo J, Niu B-L, Liang Y-Q, Yang C-H, Zhang Y, Zhang X-P, Pang X-F, 2018. Effects of long-term rapamycin treatment on glial scar formation after cryogenic traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurosci. Lett 678, 68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favuzzi E, Marques-Smith A, Deogracias R, Winterflood CM, Sánchez-Aguilera A, Mantoan L, Maeso P, Fernandes C, Ewers H, Rico B, 2017. Activity-Dependent Gating of Parvalbumin Interneuron Function by the Perineuronal Net Protein Brevican. Neuron 95, 639–655.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira CR, Gahl WA, 2017. Lysosomal storage diseases. TRD 2, 1–71. doi: 10.3233/TRD-160005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filous AR, Tran A, Howell CJ, Busch SA, Evans TA, Stallcup WB, Kang SH, Bergles DE, Lee S-I, Levine JM, Silver J, 2014. Entrapment via Synaptic-Like Connections between NG2 Proteoglycan+ Cells and Dystrophic Axons in the Lesion Plays a Role in Regeneration Failure after Spinal Cord Injury. The Journal of Neuroscience 34, 16369–16384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1309-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S, 2019. The Autophagy Lysosomal Pathway and Neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology a033993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florey O, Overholtzer M, 2012. Autophagy proteins in macroendocytic engulfment. Trends in Cell Biology 22, 374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry EJ, Chagnon MJ, López-Vales R, Tremblay ML, David S, 2010. Corticospinal tract regeneration after spinal cord injury in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma deficient mice. Glia 58, 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Wang G, Wang Y, Han D, Bi J, Yuan Y, Yao T, Wan Z, Li H, Mei X, 2015. Neuroprotective Effect of Simvastatin via Inducing the Autophagy on Spinal Cord Injury in the Rat Model. BioMed Research International 2015, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/260161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RT, Habecker BA, 2013. Infarct-derived chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans prevent sympathetic reinnervation after cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Neurosci 33, 7175–7183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5866-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatigny M, Moriceau S, Rivagorda M, Ramos-Brossier M, Nascimbeni AC, Lante F, Shanley MR, Boudarene N, Rousseaud A, Friedman AK, Settembre C, Kuperwasser N, Friedlander G, Buisson A, Morel E, Codogno P, Oury F, 2019. Autophagy Is Required for Memory Formation and Reverses Age-Related Memory Decline. Current Biology 29, 435–448.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolla N, Caroni P, Luthi A, Herry C, 2009. Perineuronal nets protect fear memories from erasure. Science 325, 1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Wang F, Li H, Liang H, Li Y, Gao Z, He X, 2018. Metformin Protects Against Spinal Cord Injury by Regulating Autophagy via the mTOR Signaling Pathway. Neurochem Res 43, 1111–1117. doi: 10.1007/s11064-018-2525-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond N, Munkacsi AB, Sturley SL, 2019. The complexity of a monogenic neurodegenerative disease: More than two decades of therapeutic driven research into Niemann-Pick type C disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1864, 1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KA, Woo D, Kim S, Choii G, Jeon S, Won SY, Kim HM, Do Heo W, Um JW, Ko J, 2016. Neurotrophin-3 Regulates Synapse Development by Modulating TrkC-PTPσ Synaptic Adhesion and Intracellular Signaling Pathways. Journal of Neuroscience 36, 4816–4831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4024-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding TM, 1995. Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. The Journal of Cell Biology 131, 591–602. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Ding Y, Chu C, Tang J, Xiao Q, Luo Z-G, 2016. Autophagy induction stabilizes microtubules and promotes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611282113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellal F, Hurtado A, Ruschel J, Flynn KC, Laskowski CJ, Umlauf M, Kapitein LC, Strikis D, Lemmon V, Bixby J, Hoogenraad CC, Bradke F, 2011. Microtubule Stabilization Reduces Scarring and Causes Axon Regeneration After Spinal Cord Injury. Science 331, 928–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn KE, Xu B, Gobert D, Hamam BN, Thompson KM, Wu C-L, Bouchard J-F, Uetani N, Racine RJ, Tremblay ML, Ruthazer ES, Chapman CA, Kennedy TE, 2012. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma regulates synapse structure, function and plasticity. J. Neurochem 122, 147–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Wu Z-B, Zhuge Q, Zheng W, Shao B, Wang B, Sun F, Jin K, 2014. Glial scar formation occurs in the human brain after ischemic stroke. Int. J. Med. Sci 11, 344–348. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Ong Tone S, Fournier AE, 2015. Extrinsic and intrinsic regulation of axon regeneration at a crossroads. Front Mol Neurosci 8, 27. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee SS, Billakanti RR, 2012. Reactive astrogliosis after spinal cord injury-beneficial and detrimental effects. Mol Neurobiol 46, 251–264. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8287-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MB, Rogers JA, Zhang P, Jensen SK, Stephenson EL, Chen T, Hurlbert MG, Lau LW, Rawji KS, Plemel JR, Koch M, Ling C-C, Yong VW, 2016. An inhibitor of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan synthesis promotes central nervous system remyelination. Nat Comms 7, 11312. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellen L, Lindahl U, 1991. Proteoglycans: structures and interactions. Annual Review of Biochemistry 60, 443–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein ZA, Takahashi H, Ma M, Stagi M, Zhou M, Lam TT, Strittmatter SM, 2017. Loss of TMEM106B Ameliorates Lysosomal and Frontotemporal Dementia-Related Phenotypes in Progranulin-Deficient Mice. Neuron 95, 281–296.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, et al. , 2016. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Wang QJ, Holstein GR, Friedrich VL, Iwata JI, Kominami E, Chait BT, Tanaka K, Yue Z, 2007. Essential role for autophagy protein Atg7 in the maintenance of axonal homeostasis and the prevention of axonal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 14489–14494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701311104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystosek A, Seeds NW, 1984. Peripheral neurons and Schwann cells secrete plasminogen activator. The Journal of Cell Biology 98, 773–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboyama K, Tanga N, Suzuki R, Fujikawa A, Noda M, 2017. Protamine neutralizes chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-mediated inhibition of oligodendrocyte differentiation. PLOS ONE 12, e0189164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SK, Woo J, Kim SY, Kim H, Kim E, 2010. Trans-synaptic Adhesions between Netrin-G Ligand-3 (NGL-3) and Receptor Tyrosine Phosphatases LAR, Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase (PTP), and PTP via Specific Domains Regulate Excitatory Synapse Formation. J Biol Chem 285, 13966–13978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamore SD, Wondrak GT, 2011. Autophagic-lysosomal dysregulation downstream of cathepsin B inactivation in human skin fibroblasts exposed to UVA. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 11, 163–172. doi: 10.1039/C1PP05131H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang BT, Cregg JM, DePaul MA, Tran AP, Xu K, Dyck SM, Madalena KM, Brown BP, Weng Y-L, Li S, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Busch SA, Shen Y, Silver J, 2015. Modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ promotes recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature 518, 404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature13974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA, 2014. Primary lysosomal dysfunction causes cargo-specific deficits of axonal transport leading to Alzheimer-like neuritic dystrophy. Autophagy 7, 1562–1563. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.12.17956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA, 2011. Lysosomal proteolysis inhibition selectively disrupts axonal transport of degradative organelles and causes an Alzheimer’s-like axonal dystrophy. J. Neurosci 31, 7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6412-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wong C, Li W, Ruven C, He L, Wu X, Lang BT, Silver J, Wu W, 2015. Enhanced regeneration and functional recovery after spinal root avulsion by manipulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ. Sci. Rep 5, 14923. doi: 10.1038/srep14923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Raisman G, 1995. Sprouts from cut corticospinal axons persist in the presence of astrocytic scarring in long-term lesions of the adult rat spinal cord. Experimental Neurology 134, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, 2019. Emerging Concepts and Functions of Autophagy as a Regulator of Synaptic Components and Plasticity. Cells 8, 34. doi: 10.3390/cells8010034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Li Y, Choi HMC, Sarkar C, Koh EY, Wu J, Lipinski MM, 2018. Lysosomal damage after spinal cord injury causes accumulation of RIPK1 and RIPK3 proteins and potentiation of necroptosis. Cell Death Dis 9, 37. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0469-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Sarkar C, Dinizo M, Faden AI, Koh EY, Lipinski MM, Wu J, 2015. Disrupted autophagy after spinal cord injury is associated with ER stress and neuronal cell death. Cell Death Dis 6, e1582–e1582. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Tran AP, Xin L, Sanapala C, Lang BT, Silver J, Yang Y, 2018. Modulation of proteoglycan receptor PTPσ enhances MMP-2 activity to promote recovery from multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun 9, 3165. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06505-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S, Holzbaur ELF, 2014. Autophagosome assembly and cargo capture in the distal axon. Autophagy 8, 858–860. doi: 10.4161/auto.20055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S, Wallace KE, Holzbaur ELF, 2012. Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. The Journal of Cell Biology 196, 407–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KR, Xu Y, Looyenga BD, Davis RJ, Wu CL, Tremblay ML, Xu HE, MacKeigan JP, 2011. Identification of PTP as an autophagic phosphatase. Journal of Cell Science 124, 812–819. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey JM, Hubscher CH, Wagoner MR, Decker JA, Amps J, Silver J, Onifer SM, 2006. Chondroitinase ABC digestion of the perineuronal net promotes functional collateral sprouting in the cuneate nucleus after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci 26, 4406–4414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5467-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire PG, Seeds NW, 1990. Degradation of underlying extracellular matrix by sensory neurons during neurite outgrowth. Neuron 4, 633–642. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90121-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J, Batt J, Doering LC, Rotin D, Bain JR, 2002. Enhanced rate of nerve regeneration and directional errors after sciatic nerve injury in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma knock-out mice. J. Neurosci 22, 5481–5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng HY, Shao DC, Li H, Huang XD, Yang G, Xu B, Niu HY, 2018. Resveratrol improves neurological outcome and neuroinflammation following spinal cord injury through enhancing autophagy involving the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Mol Med Report 18, 2237–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H, Warita H, Aoki M, Itoyama Y, 2008. Accumulation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the microenvironment of spinal motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis transgenic rats. J. Neurosci. Res 86, 2512–2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizunoe Y, Sudo Y, Okita N, Hiraoka H, Mikami K, Narahara T, Negishi A, Yoshida M, Higashibata R, Watanabe S, Kaneko H, Natori D, Furuichi T, Yasukawa H, Kobayashi M, Higami Y, 2017. Involvement of lysosomal dysfunction in autophagosome accumulation and early pathologies in adipose tissue of obese mice. Autophagy 13, 642–653. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1274850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan H, Krumbholz M, Sharma R, Eisele S, Junker A, Sixt M, Newcombe J, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R, Lassmann H, Meinl E, 2010. Extracellular Matrix in Multiple Sclerosis Lesions: Fibrillar Collagens, Biglycan and Decorin are Upregulated and Associated with Infiltrating Immune Cells. Brain Pathology 203, no–no. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Galdeano T, Reigada D, del Águila Á, Velez I, Caballero-López MJ, Maza RM, Nieto-Díaz M, 2018. Cell Specific Changes of Autophagy in a Mouse Model of Contusive Spinal Cord Injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci 12, 13. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y, Lee AK, Takahashi H, 2017. Emerging roles of the neurotrophin receptor TrkC in synapse organization. Neuroscience Research 116, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Chen J, Yang J, Pei Q, Li J, Liu J, Xu L, Li N, Chen Y, Chen X, Luo H, Sun T, 2018. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids promotes locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol Med Report 17, 5894–5902. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niknam P, Raoufy MR, Fathollahi Y, Javan M, 2019. Modulating proteoglycan receptor PTPσ using intracellular sigma peptide improves remyelination and functional recovery in mice with demyelinated optic chiasm. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 99, 103391. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.103391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblander SA, Brady-Kalnay SM, 2010. Distinct PTPmu-associated signaling molecules differentially regulate neurite outgrowth on E-, N-, and R-cadherin. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 44, 78–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KK, Luo X, Mooney SJ, Yungher BJ, Belin S, Wang C, Holmes MM, He Z, 2017. Retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration after optic nerve injury in naked mole-rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology 525, 380–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.24070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett JW, Maffei L, 2002. Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science 298, 1248–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Properzi F, Asher RA, Fawcett JW, 2003. Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans in the central nervous system: changes and synthesis after injury. Biochem. Soc. Trans 31, 335–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyka M, Wetzel C, Aguado A, Geissler M, Hatt H, Faissner A, 2011. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans regulate astrocyte-dependent synaptogenesis and modulate synaptic activity in primary embryonic hippocampal neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience 33, 2187–2202. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Pulido CS-PMTMS, Pulido R, Serra-Pagès C, Tang M, Streuli M, 1995. The LAR/PTP delta/PTP sigma subfamily of transmembrane protein-tyrosine-phosphatases: multiple human LAR, PTP delta, and PTP sigma isoforms are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and associate with the LAR-interacting protein LIP.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92, 11686–11690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaraju S, Verrier JD, Madorsky I, Nicks J, Dunn WA, Notterpek L, 2010. Rapamycin Activates Autophagy and Improves Myelination in Explant Cultures from Neuropathic Mice. Journal of Neuroscience 30, 11388–11397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1356-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink S, Arnold D, Wöhler A, Bendella H, Meyer C, Manthou M, Papamitsou T, Sarikcioglu L, Angelov DN, 2018. Recovery after spinal cord injury by modulation of the proteoglycan receptor PTPσ. Experimental Neurology 309, 148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland AM, 2006. Presynaptic Terminals Independently Regulate Synaptic Clustering and Autophagy of GABAA Receptors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Neuroscience 26, 1711–1720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruschel J, Hellal F, Flynn KC, Norenberg MD, Blesch A, Bradke F, 2015. Axonal regeneration. Systemic administration of epothilone B promotes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Science 348, 347–352. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Ozaki T, Ko Y-C, Tsai C-F, Gong Y, Morozumi M, Ishikawa Y, Uchimura K, Nadanaka S, Kitagawa H, Zulueta MML, Bandaru A, Tamura J-I, Hung S-C, Kadomatsu K, 2019. Glycan sulfation patterns define autophagy flux at axon tip via PTPRσ-cortactin axis. Nature chemical biology 42, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapieha PS, Duplan L, Uetani N, Joly S, Tremblay ML, Kennedy TE, Di Polo A, 2005. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma inhibits axon regrowth in the adult injured CNS. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 28, 625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraswat Ohri S, Bankston AN, Mullins SA, Liu Y, Andres KR, Beare JE, Howard RM, Burke DA, Riegler AS, Smith AE, Hetman M, Whittemore SR, 2018. Blocking Autophagy in Oligodendrocytes Limits Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neuroscience 38, 5900–5912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0679-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar C, Zhao Z, Aungst S, Sabirzhanov B, Faden AI, Lipinski MM, 2015. Impaired autophagy flux is associated with neuronal cell death after traumatic brain injury. Autophagy 10, 2208–2222. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.981787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Yoshida H, 2015. Organelle autoregulation-stress responses in the ER, Golgi, mitochondria and lysosome. Journal of Biochemistry 157, 185–195. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaapveld RQ, Schepens JT, Bächner D, Attema J, Wieringa B, Jap PH, Hendriks WJ, 1998. Developmental expression of the cell adhesion molecule-like protein tyrosine phosphatases LAR, RPTPdelta and RPTPsigma in the mouse. Mech. Dev 77, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoor M, Stradal TE, Rottner K, 2018. Cortactin: Cell Functions of A Multifaceted Actin-Binding Protein. Trends in Cell Biology 28, 79–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, 2014. Traffic lights for axon growth: proteoglycans and their neuronal receptors. Neural Regen Res 9, 356–361. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.128236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Shen Y, Tenney AP, Tenney AP, Busch SA, Busch SA, Horn KP, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Cuascut FX, Liu K, Liu K, He Z, He Z, Silver J, Silver J, Flanagan JG, Flanagan JG, 2009. PTP Is a Receptor for Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan, an Inhibitor of Neural Regeneration. Science 326, 592–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1178310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JR, Stelzner DJ, Osterhout DJ, 2011. Chondroitinase treatment following spinal contusion injury increases migration of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Experimental Neurology 231, 19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu R, Fladd C, Rotin D, 2006. N-Cadherin Is an In Vivo Substrate for Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Sigma (PTP) and Participates in PTP -Mediated Inhibition of Axon Growth. Molecular and Cellular Biology 27, 208–219. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00707-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleman S, Yip PK, Duricki DA, Moon LDF, 2012. Delayed treatment with chondroitinase ABC promotes sensorimotor recovery and plasticity after stroke in aged rats. Brain 135, 1210–1223. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son Y-J, 2015. Synapsing with NG2 cells (polydendrocytes), unappreciated barrier to axon regeneration? Neural Regen Res 10, 346. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.153672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soori M, Lu G, Mason RW, 2016. Cathepsin Inhibition Prevents Autophagic Protein Turnover and Downregulates Insulin Growth Factor-1 Receptor–Mediated Signaling in Neuroblastoma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 356, 375–386. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Arstikaitis P, Prasad T, Bartlett TE, Wang YT, Murphy TH, Craig AM, 2011. Postsynaptic TrkC and presynaptic PTPsigma function as a bidirectional excitatory synaptic organizing complex. 69, 287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Craig AM, 2013. Protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP. Trends in Neurosciences 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y-J, Li K, Yang C-L, Huang K, Zhou J, Shi Y, Xie K-G, Liu J, 2019. Bisperoxovanadium protects against spinal cord injury by regulating autophagy via activation of ERK1/2 signaling. DDDT Volume 13, 513–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatti M, Motta M, Di Bartolomeo S, Scarpa S, Cianfanelli V, Cecconi F, Salvioli R, 2012. Reduced cathepsins B and D cause impaired autophagic degradation that can be almost completely restored by overexpression of these two proteases in Sap C-deficient fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 5159–5173. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KM, Uetani N, Manitt C, Elchebly M, Tremblay ML, Kennedy TE, 2003. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma inhibits axonal regeneration and the rate of axon extension. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 23, 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumm M, Egner R, Koch B, Schlumpberger M, Straub M, Veenhuis M, Wolf DH, 1994. Isolation of autophagocytosis mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters 349, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom VJ, Steinmetz MP, Miller JH, Doller CM, Silver J, 2004. Studies on the Development and Behavior of the Dystrophic Growth Cone, the Hallmark of Regeneration Failure, in an In Vitro Model of the Glial Scar and after Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neuroscience 24, 6531–6539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0994-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AP, Sundar S, Yu M, Lang BT, Silver J, 2018a. Modulation of Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Sigma Increases Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan Degradation through Cathepsin B Secretion to Enhance Axon Outgrowth. Journal of Neuroscience 38, 5399–5414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3214-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AP, Warren PM, Silver J, 2018b. The Biology of Regeneration Failure and Success After Spinal Cord Injury. Physiological Reviews 98, 881–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY, 2013. Very long-term memories may be stored in the pattern of holes in the perineuronal net. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 12456–12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y, 1993. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters 333, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um JW, Kim KH, Park BS, Choi Y, Kim D, Kim CY, Kim SJ, Kim M, Ko JS, Lee S-G, Choii G, Nam J, Do Heo W, Kim E, Lee J-O, Ko J, Kim HM, 2014. Structural basis for LAR-RPTP/Slitrk complex-mediated synaptic adhesion. Nat Comms 5, 5423. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Végh MJ, Heldring CM, Kamphuis W, Hijazi S, Timmerman AJ, Li KW, van Nierop P, Mansvelder HD, Hol EM, Smit AB, van Kesteren RE, 2014. Reducing hippocampal extracellular matrix reverses early memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 76. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0076-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Boerboom D, Tremblay ML, 1994. Molecular Cloning and Tissue-Specific RNA Processing of a Murine Receptor-Type Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase. Eur J Biochem 226, 773–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00773.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Jiang L, Zhou N, Zhou H, Liu H, Zhao W, Zhang H, Zhang X, Hu Z, 2018. Resveratrol ameliorates autophagic flux to promote functional recovery in rats after spinal cord injury. Oncotarget 9, 8427–8440. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren PM, Steiger SC, Dick TE, MacFarlane PM, Alilain WJ, Silver J, 2018. Rapid and robust restoration of breathing long after spinal cord injury. Nat Commun 9, 114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06937-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese S, Faissner A, 2015. The role of extracellular matrix in spinal cord development. Experimental Neurology 274, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Kwon S-K, Choi S, Kim S, Lee J-R, Dunah AW, Sheng M, Kim E, 2009. Trans-synaptic adhesion between NGL-3 and LAR regulates the formation of excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci 12, 428–437. doi: 10.1038/nn.2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-L, Hardy S, Aubry I, Landry M, Haggarty A, Saragovi HU, Tremblay ML, 2017. Identification of function-regulating antibodies targeting the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma ectodomain. PLoS ONE 12, e0178489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Wei X, Wu Y, Kong X, Hu A, Tong S, Liu Y, Gong F, Xie L, Zhang J, Xiao J, Zhang H, 2018. Chloroquine Promotes the Recovery of Acute Spinal Cord Injury by Inhibiting Autophagy-Associated Inflammation and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Journal of Neurotrauma 35, 1329–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Grossman A, Wang H, D’Eustachio P, Mossie K, Musacchio JM, Silvennoinen O, Schlessinger J, 1993. A novel receptor tyrosine phosphatase-sigma that is highly expressed in the nervous system. J Biol Chem 268, 24880–24886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Cacquevel M, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, Melani R, Pizzorusso T, Fawcett JW, Spillantini MG, 2015. Perineuronal net digestion with chondroitinase restores memory in mice with tau pathology. Experimental Neurology 265, 48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]