Abstract

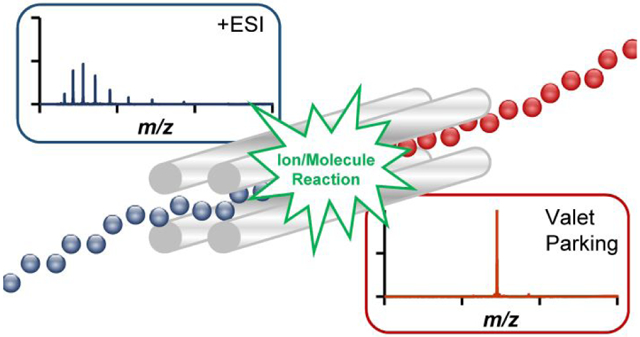

There are several analytical applications in which it is desirable to concentrate analyte ions generated over a range of charge states into a single charge state. This has been demonstrated in the gas-phase via ion/ion reactions in conjunction with a technique termed ion parking, which can be implemented in electrodynamic ion traps. Ion parking depends upon the selective inhibition of the reaction of a selected charge state or charge states. In this work, we demonstrate a similar charge state concentration effect using ion/molecule reactions rather than ion/ion reactions. The rates of ion/molecule reactions cannot be affected in the manner used in conventional ion parking. Rather, to inhibit the progression of ion/molecule proton transfer reactions, the product ions must be removed from the reaction cell as they are formed and transferred to an ion trap where no reactions occur. This is accomplished here with mass selective axial ejection (MSAE) from one linear ion trap to another. The application of MSAE to inhibit ion/molecule reactions is referred to as “valet parking” as it entails the transport of the ions of interest to a remote location for storage. Valet parking is demonstrated using model proteins to concentrate ion signal dispersed over multiple charge states into largely one charge state. Additionally, it has been applied to a simple two protein mixture of cytochrome c and myoglobin.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Electrospray ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique capable of generating large intact bio-ion and bio-ion complexes.1,2 As ESI generates ions directly from solution, it is readily coupled to liquid chromatography and is compatible with all commonly used mass analyzers due to its propensity for generating a distribution of multiply charged ions in a modest and relatively narrow mass-to-charge range. For these and other reasons, ESI has become widely used in bioanalytical mass spectrometry. While the multiplicity of charge states can be beneficial for accurate mass measurement and for generating a range of precursor ions to be subjected to various fragmentation techniques, there are several scenarios in which it is desirable to manipulate the precursor ion distribution. Such scenarios include the generation of charge states not directly formed under normal operating conditions, reduction in spectral complexity, the concentration of ion signal into a single charge state, or a combination of the latter two for increased sensitivity.

Changes in charge state distributions in an electrospray mass spectrum resulting from changes in solution conditions can be dramatic, particularly when the conformational states of the analytes are altered.3 However, precise control over charge states via alteration in solution conditions is generally limited. Both gas-phase ion/ion and gas-phase ion/molecule proton transfer reactions, on the other hand, can be used to precisely manipulate ion charge. These approaches are relatively mature in terms of their analytical utility. Some examples of early work involving gas-phase proton transfer reactions include, but are not limited to, the improved mass determination of protein ions,4,5 the determination of product ion charge,6-8 and charge state purification.9,10 In recent years, there has been an extension of proton transfer ion/ion reactions to higher resolution instruments,11-14 due, in part, to an increase in the complexity of protein mixtures subjected to analysis and to an increase in the number of instruments equipped to perform such experiments. On the other hand, proton transfer ion/molecule reactions are less widespread in modern workflows. Rather, functional group specific reactions constitute the majority of recent literature in the field of analytical ion/molecule reactions.15-17 Nonetheless, proton transfer ion/molecule reactions are easy to implement across multiple instrument platforms as they require only the controlled admission of a gaseous reagent into a reaction region. In most cases, this can be accomplished by tapping the existing bath gas line. Additionally, many of the applications alluded to above could be accomplished via ion/molecule proton transfer reactions.

Previous work from our group involving ion/ion reactions has demonstrated that the kinetics, and the extent of reactant ion population overlap, can be affected to impede the progress of the reaction in a process referred to as “ion parking.”18 This is accomplished by the application of an auxiliary RF signal at the secular frequency of an ion/ion reaction product ion. Application of auxiliary RF serves to excite ions of a particular mass-to-charge ratio such that the velocity of the ions is increased and, consequently, the ion/ion capture cross section is decreased. Additionally, the excitation leads to a slight decrease in ion cloud overlap as one population of ions is excited away from the center of the trap while the other is retained in the center of the trap. This decrease in cross section and in ion cloud overlap is the basis for ion parking. In this approach, only a narrow band of m/z values are affected. Similarly, a broad range of frequencies can be applied to park a broad range of m/z values in “parallel ion parking.”19,20

To our knowledge, there is no equivalent technique to mass selectively inhibit ion/molecule reactions. This report demonstrates the mass selective inhibition of ion/molecule reactions denoted, herein, as “valet parking.” Valet parking uses mass selective axial ejection, MSAE,21 to axially eject ion/molecule product ions, as they are formed, into a separate region of the mass spectrometer where no further ion/molecule reaction products are formed. Previous reports have demonstrated the mass selective transfer of ions between ion traps, though not for the purposes of inhibiting ion/molecule reactions.22,23 Proof-of-concept data is presented for three model proteins, ubiquitin, cytochrome c, and myoglobin. Additionally, valet parking has been applied to a simple two component mixture of cytochrome c and myoglobin.

Experimental

Materials and Sample Preparation

Ubiquitin from bovine erythrocytes, cytochrome c from equine heart, and myoglobin from equine heart were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Trimethylamine was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). HPLC-grade methanol and Optima LC/MS-grade water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), and acetic acid was purchased from Mallinckrodt (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Protein stock solutions were prepared at a concentration of approximately 1 mg/mL. Stocks were diluted to a concentration of 1 μM, 2 μM, and 2 μM for ubiquitin, cytochrome c, and myoglobin, respectively, in 49.5/49.5/1, by volume, water/methanol/acetic acid. A simple protein mixture of 1μM cytochrome c and 1 μM myoglobin was prepared in 49.5/49.5/1, by volume, water/methanol/acetic acid.

Mass Spectrometry

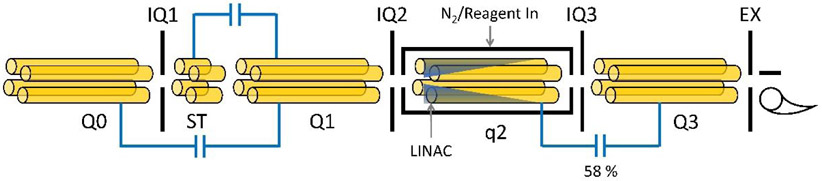

All experiments were performed on a modified QTRAP 4000 hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada). The ion path is depicted in Figure 1. The major components of the ion path relevant to valet parking include a QStar collision cell (q2) equipped with a LINAC (LN) followed by an RF/DC quadrupole array (Q3). The collision cell has an inscribed radius of 4.17 millimeters and is enclosed by IQ2 and IQ3. The RF used to drive q2 was transferred from the 816 kHz Q3 power supply through a capacitive coupling network at 58%.

Figure 1.

Ion optics and essential elements of the QTRAP 4000 ion path.

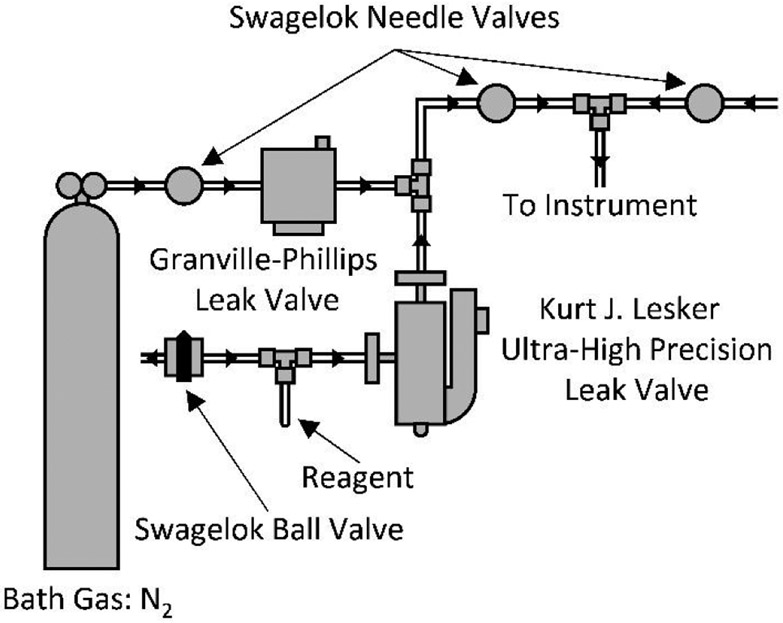

The bath gas supply line of q2 was modified ex-vacuo with an external reagent mixing manifold similar to those described by Gronert and Kenttamaa (Figure 2).24,25 The supply line was split using a tee connector with the mixing manifold on one side and a pure nitrogen gas supply on the other. To perform ion/molecule reactions, the needle valve of the pure nitrogen gas supply line was closed, and the needle valve of the manifold was opened. Initially, the variable leak valve (Granville-Phillips, Series 203, Boulder, CO, USA) was fully closed; the valve was slowly opened until the pressure in the main vacuum chamber was approximately 3.5 x 10−5 Torr, corresponding to a pressure of approximately 6.67 mTorr in q2. The neutral reagent (trimethylamine) was introduced into the nitrogen flow by opening the ultra-high precision leak valve (Kurt J. Lesker, VZLVM263R, Jefferson Hills, PA, USA). For all experiments, admittance of trimethylamine into q2 did not result in a change in the ion gauge reading, and, therefore, the precise concentration of trimethylamine is unknown. However, based on the sensitivity of the ion gauge, the concentration of neutral reagent can be deduced as less than 0.3% of the total pressure. The instrument was allowed to equilibrate for approximately 20 minutes prior to data collection.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the external manifold used to introduce reagent in q2 for ion/molecule reactions.

During valet parking experiments, q2 and Q3 were both operated as linear ion traps. Analyte cations were generated via electrospray ionization and injected into q2. During injection, the LINAC voltage was set to 20 V and the ions were trapped axially in q2 by DC barriers applied to IQ2 and IQ3. After injection, the DC voltage of IQ3 was lowered and ions were bunched in q2 near the fringing-field of IQ3 using a LINAC voltage of 200 V. The amplitude of the RF applied to Q3 was adjusted to place the desired ion/molecule product ion at q = 0.4 in q2. The ions were allowed to react with the neutral reagent for up to 900 ms, during which, an auxiliary sinusoidal waveform was applied to q2 in a dipolar fashion at q = 0.4 (calculated). The auxiliary waveform was generated using the buffered and amplified output of an Agilent 33220A waveform generator which was monitored using an oscilloscope (Tektronix, TDS 2014C, Beaverton, OR, USA). The frequency of the auxiliary waveform was tuned to be on resonance with the secular frequency of the desired ion/molecule product ion. After the reaction period, the auxiliary waveform was switched off and any product ions that were transferred into Q3 during valet parking were mass analyzed via MSAE. After detection, the voltages of the ion path were adjusted to eject the remaining ions in q2.

Results and Discussion

Valet Parking Premise and Theory

Unlike ion/ion reactions, where the reaction rates follow a v−3 dependence,26,27 the reaction rates for ion/molecule reactions under accessible conditions are not strongly dependent upon ion velocity.28 Therefore, ion/molecule reaction rates cannot be significantly affected by simply applying auxiliary RF to excite the product ion of interest. Rather, to halt ion/molecule reactions, product ions must be transferred from the reaction cell to a region of the instrument where no further reactive ion/molecule collisions occur. Here, the inhibition of ion/molecule reactions via the shuttling of a reaction product of interest to a location where no reactions occur is referred to here as “valet parking”. The premise for valet parking is the physical separation of product ions from the neutral reagent, which can be accomplished via MSAE.

With MSAE, ions can be axially ejected from a linear ion trap in a mass selective fashion as a consequence of the electric fields near the fringing region. In the fringing region, there is a diminishing quadrupolar potential where an ion’s radial motion is coupled to axial motion. Superposition of a repulsive DC potential of the endcap lens with the diminishing quadrupolar potential generates a cone of reflection.21 The cone of reflection is a conical shaped barrier that separates a region of reflection and a region of ejection (i.e. ions inside the cone are reflected back into the quadrupole while ions outside of the cone are axially ejected). In the absence of an auxiliary signal, ions will remain trapped. The ions, however, can be selectively excited on the basis of mass-to-charge.

The mass dependent frequencies of ion motion are described by the equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where u represents the x- or y-dimension, n is an integer, Ω is the angular frequency of the drive RF, and a and q parameters are the Mathieu dimensionless parameters given by:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where C1 and C2 are constants that vary depending on the operating mode of the ion trap, U is the amplitude of DC, V is the amplitude of RF used to trap the ions, ro is the radius of the quadrupole array, m is the mass of the ion, and e is the charge of the ion. In the special case where n is equal to zero, we obtain the ion’s fundamental frequency written as:

| (5) |

Equation 5 contains β, which, as shown in Equation 2 is dependent on au and qu. As the cone of reflection is only present in the fringing regions, ions can be bunched into the fringing region using the LINAC. Application of auxiliary RF at the fundamental frequency increases the radial displacement of the desired product ion. Once the ion’s radial displacement passes the cone of reflection barrier, the ion is axially ejected into Q3.

Demonstration of Valet Parking

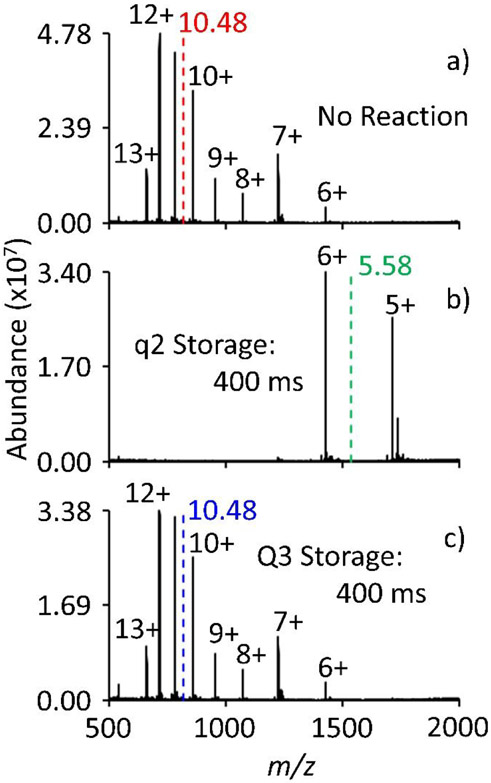

For valet parking to effectively inhibit ion/molecule reactions, ions must be transferred to a region of the mass spectrometer where no further ion/molecule reaction occurs. Figure 3 establishes the fact that the number density of neutral reagent in Q3 is sufficiently low such that there is no observable ion/molecule reaction over an extended period. Electrospray ionization of ubiquitin prior to introduction of trimethylamine generates the mass spectrum shown in Figure 3a. The abundance weighted average charge state was calculated to be 10.48 and is shown in red. After a 400 ms reaction with trimethylamine in q2, the abundance weighted average charge states shifts to 5.58 (Figure 3b). Conversely, when the ubiquitin ions are injected through q2 and trapped in Q3 for 400 ms, the abundance weighted average charge state is identical to that of the pre ion/molecule reaction spectrum (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Positive electrospray mass spectrum of ubiquitin with a) no additional storage time in q2 or Q3, b) 400 ms storage in q2 (i.e. 400 ms ion/molecule reaction), and c) 400 ms storage in Q3 prior to mass analysis. The abundance weighted average charge state is represented with the colored dashed line.

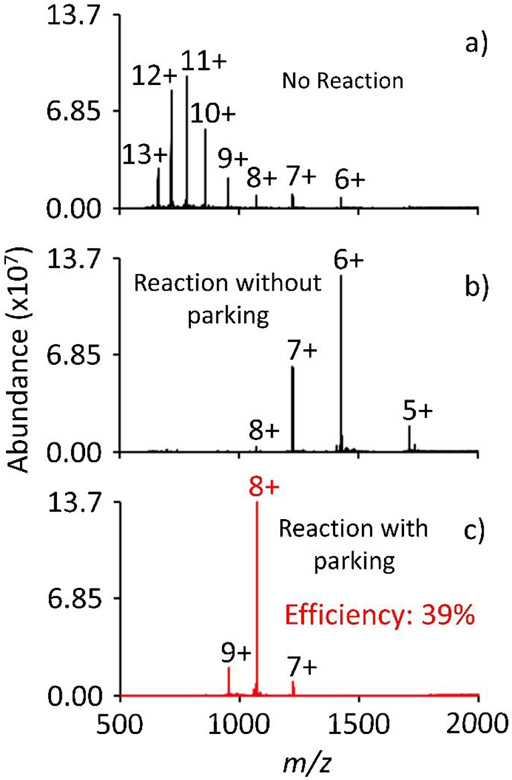

Valet parking is first demonstrated using ubiquitin ions. Figure 4a shows the electrospray mass spectrum of ubiquitin under denaturing conditions. Here, ubiquitin ions were transmitted through q2, trapped and stored in Q3 for 900 ms, and subsequently mass analyzed. Akin to a normal electrospray mass spectrum with no neutral admitted into q2, the spectrum shows a bimodal distribution spanning the 13+ to the 6+ charge states (compare Figure 3a to Figure 4a). Figure 4b shows the mass spectrum after the ubiquitin cations were stored in q2, with trimethylamine, for 900 ms prior to being transferred to Q3 and subsequently mass analyzed. Under these conditions, the ubiquitin distribution shifts to lower charge states. The base peak in the post ion/molecule reaction spectrum is the 6+.

Figure 4.

Positive electrospray mass spectrum of ubiquitin a) pre-ion/molecule reaction, b) post ion/molecule reaction, and c) valet parking of the 8+ charge state. The ion/molecule reaction time is 900 ms, the IQ3 barrier was set to 1.5 V, and a valet parking waveform of 1.9 V at 114.367 kHz was used.

Figure 4c displays the resulting mass spectrum after valet parking, where the reagent concentration and the ion/molecule reaction duration is identical to Figure 4b. In this experiment, however, the Q3 low mass cut off (LMCO) was set to m/z 876.5, which places the 8+ charge state of ubiquitin at approximately q = 0.4 in q2. Additionally, during the reaction period, a 1.9 V auxiliary signal was applied to q2 at a frequency of 114.367 kHz. By applying a dipolar sine wave at a frequency corresponding to q = 0.4, and by judiciously lowering the IQ3 barrier to 1.5 V, any ions at q = 0.4 will be axially transferred from q2 to Q3 as a consequence of their radial displacement in response to the auxiliary signal.

The progression of the ion/molecule proton transfer reaction is significantly affected in the valet parking experiment as evidenced by the abundance of 8+ ion in Figure 4c relative to that depicted in Figure 4b. Transferring the 8+ ions to Q3 as they are formed halts the reactions and concentrates the ion signal into largely the 8+ charge state. In fact, when comparing the area of the parked 8+ to the area of the 8+ in the pre ion/molecule spectrum, there is a 16x increase in signal. Additionally, the efficiency of valet parking can be quantified as a percentage of the summed charge state area for all charge states prior to, and including, the 8+ from the pre ion/molecule spectrum. In the case of ubiquitin 8+, valet parking showed an efficiency of 39%. In other words, 39% of the signal preceding, and including ubiquitin 8+, in the pre ion/molecule spectrum was concentrated into ubiquitin 8+ during valet parking.

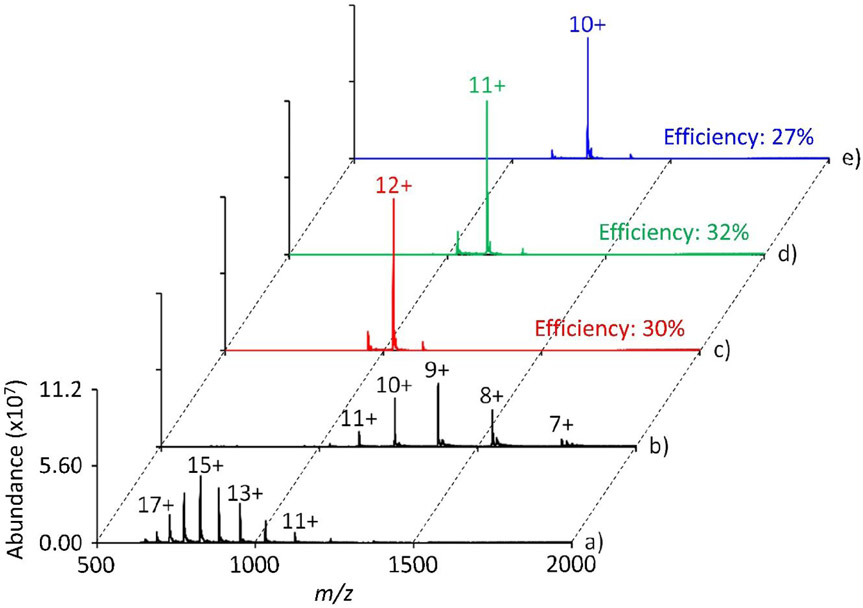

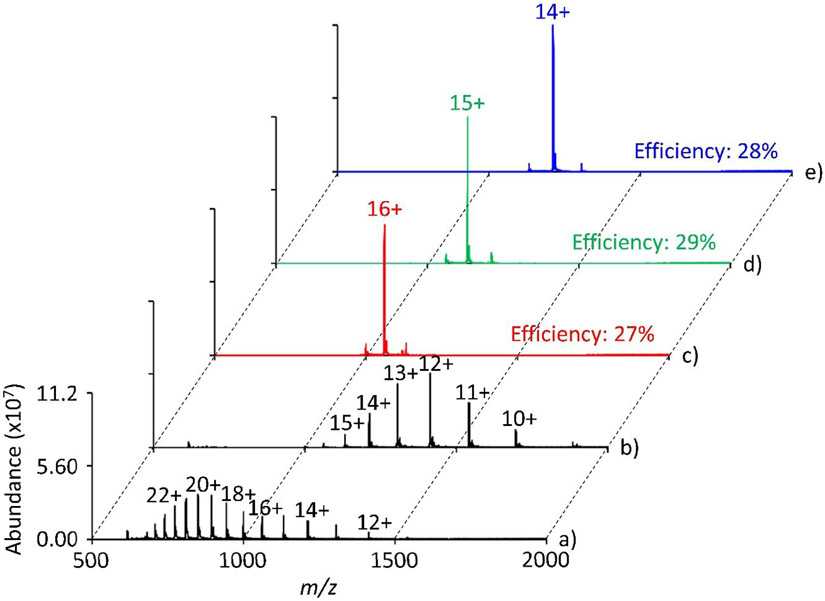

Valet parking was also successfully demonstrated with cytochrome c and myoglobin with efficiencies ranging from 27% to 32% (Figures 5 and 6, respectively). In the case of cytochrome c, separate valet parking experiments were performed on three charge states during a 900 ms ion/molecule reaction. The Q3 LMCO was set to m/z 843.8, 919.8, and 1011.4 to place cytochrome c 12+, 11+, and 10+, respectively, at q = 0.4. For parking, the IQ3 barrier was set to 1.8 V and a 1.8 V resonance excitation waveform at 114.367 kHz was applied to q2. Similarly, for myoglobin, valet parking was performed on the 16+, 15+, and 14+ charge states using an IQ3 barrier of 2.0 V and a 2.0 V sine wave at 114.367 kHz. In all cases, the progression of the ion/molecule reaction is largely inhibited in a mass selective fashion. There is, however, a small degree of undesired charge states that are also transferred to Q3 during valet parking that are likely due to limitations of the current apparatus, as discussed further below.

Figure 5.

Positive electrospray mass spectrum of cytochrome c a) pre-ion/molecule reaction, b) post ion/molecule reaction, and valet parking of the c) 12+, d) 11+, or e) 10+ charge state. The ion/molecule reaction time is 900 ms, the IQ3 barrier was set to 1.8 V, and a valet parking waveform of 1.8 V at 114.367 kHz was used.

Figure 6.

Positive electrospray mass spectrum of myoglobin a) pre-ion/molecule reaction, b) post ion/molecule reaction, and valet parking of the c) 16+, d) 15+, or e) 14+ charge state. The ion/molecule reaction time is 600 ms, the IQ3 barrier was set to 2.0 V, and a valet parking waveform of 2.0 V at 114.367 kHz was used.

Valet Parking of a Simple Mixture

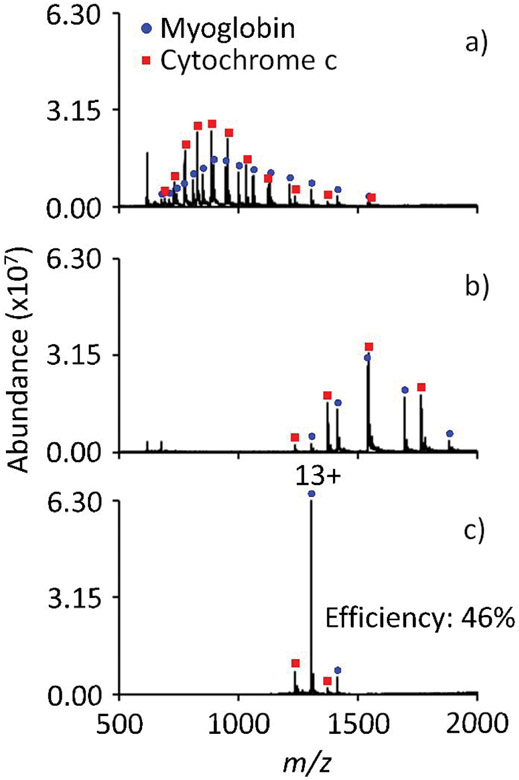

The utility of using ion parking during ion/ion reactions has been demonstrated with applications that have included precursor ion charge state concentration,29,30 enhancements in selectivity during protein quantitation,31 and gas-phase charge state purification.9,32 Similar applications for valet parking can be envisioned. Perhaps the simplest application of valet parking is the charge state purification of a simple two protein mixture. This simple scenario is beneficial when two ions from two distinct proteins are of similar mass-to-charge. An ion/molecule reaction can be used to charge state purify and concentrate one particular protein signal while the other component is largely reacted to higher m/z values. In this way, one can easily isolate the charge state purified signal and perform subsequent interrogation. This scenario is demonstrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Positive electrospray mass spectrum of a cytochrome c and myoglobin mixture a) pre-ion/molecule reaction, b) post ion/molecule reaction, and c) valet parking of the myoglobin 13+ charge state. The ion/molecule reaction time is 900 ms, the IQ3 barrier was set to 2.0 V, and a valet parking waveform of 2.0 V at 114.367 kHz was used.

Figure 7a shows the electrospray mass spectrum from a mixture of ions derived from cytochrome c and myoglobin. There are several cases where cytochrome c and myoglobin ions are close in m/z. For example, the most abundant charge state of myoglobin, [M + 19H]19+, is only 2 units higher in nominal m/z than a sodium adducted cytochrome c ion at m/z 892. A 900 ms ion/molecule reaction results in the spectrum shown in Figure 7b. Here, the majority of charge states are well resolved. A valet parking experiment allows for the concentration of one protein component while discriminating against the other component as demonstrated in the comparison of Figures 7b and 7c. Figure 7c shows the post ion/molecule reaction spectrum using the same conditions as Figure 7b except a valet parking waveform (114.367 kHz, 2.0 V) was used to park myoglobin 13+. Much of the myoglobin population is concentrated into the 13+, showing an efficiency of 46% while most of the cytochrome c ions remain in q2 for subsequent removal.

Potential Improvements

As mentioned above, during valet parking in this work, some undesired charge states are also admitted into Q3. Additionally, less than half of the potential signal is actually concentrated. Supplemental Figure S1 demonstrates that some of the precursor signal is not transferred and not all of the desired charge state is transferred during valet parking. Here, an 800 ms ion/molecule reaction is performed in q2 with a parking waveform applied to the 13+ charge state of cytochrome c. Unlike previous experiments, however, the 13+ is sent through Q3 and the remaining ions in q2 are subsequently transferred to Q3 and mass analyzed. It is clear that a significant portion of signal remains in q2 during valet parking.

While the degrees of selectivity and concentration can be maximized, to some extent, by tuning the IQ3 barrier and auxiliary waveform parameters (i.e. amplitude and frequency), these figures of merit are largely limited by the q-value at which valet parking is performed. With the current setup, q2 is capacitively coupled to Q3 at 58%, which limits the q-value in q2 to q = 0.4 before the mass of the desired ion becomes lower in m/z than the Q3 LMCO. For example, a Q3 LMCO of m/z 843.2 is needed to place the 12+ charge state of cytochrome c (m/z 1031) at q = 0.4 in q2 while a Q3 LMCO of m/z 1054.0 is needed to place the same ion at q = 0.5 in q2. It is clear that if valet parking were performed at q = 0.5 the desired ion would be transferred to but not trapped in Q3 on the basis of m/z.

Londry and Hager have demonstrated that the sensitivity and resolution of MSAE increases as a function of q-value.21,33,34 The increase in ion signal (i.e. sensitivity) is due to the changes in the shape of the cone of reflection; at higher q-values, the cone of reflection penetrates further into the quadrupole and, consequently, increases the volume in which axial ejection can occur. Therefore, it is expected that if q2 and Q3 were decoupled, valet parking could be performed at a higher q-value with greater efficiency resulting in higher percentages of concentration.

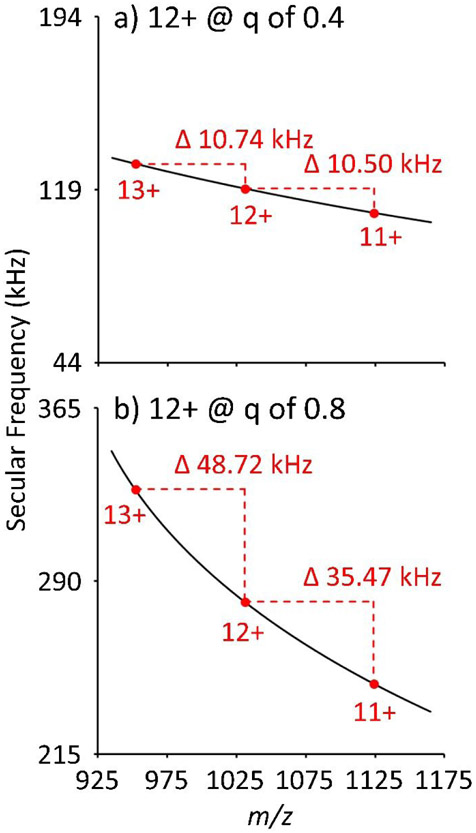

Increasing the q-value for MSAE is also expected to improve the valet parking selectivity. Figure 8 shows the calculated secular frequency dispersion between three consecutive charge states of cytochrome c. When cytochrome c 12+ is placed at q = 0.4, there is a 10.74 kHz difference between the 13+ and 12+ ions and a 10.50 kHz difference between the 12+ and 11+ ions. Yet, when cytochrome c 12+ is placed at q = 0.8, there is a 48.72 kHz difference between the 13+ and 12+ ions and a 35.47 kHz difference between the 12+ and 11+ ions. Additionally, since ions at higher q require less radial displacement to overcome the repulsive barrier of the cone of reflection, lower amplitude waveforms can be used for resonance excitation leading to less off-resonance power absorption by ions of nearby m/z. When combining the increased frequency spacing between consecutive charges states with the ability to use lower amplitude auxiliary signals, the resolution of the MSAE, and hence the selectivity of valet parking, should increase. Further improvements to valet parking may be accomplished with phase synchronous RF applied to IQ3.35 Lastly, the operating pressure of the Q3 linear ion trap may be influencing the trapping efficiency of ions admitted into Q3. Raising the buffer gas pressure may improve ion capture efficiency.

Figure 8.

Calculated ion frequencies and ion frequency dispersion for consecutive charge states of cytochrome c when cytochrome c 12+ is placed at a) q = 0.4 and b) q = 0.8.

Conclusions

Proof-of-concept data is presented for protein ion charge state concentration via ion/molecule reactions. Ions of a selected mass-to-charge ratio are transferred from the reaction cell to a region of the mass spectrometer where no ion/molecule reaction is observed. We have demonstrated valet parking on a hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer using MSAE, yet one could envision the technique to be implemented on other ion trapping instruments with consecutive trapping regions. For instance, valet parking could be implemented using a 3D ion trap using resonance ejection, provided that ions could be transferred and trapped in another trapping device. Additionally, valet parking could be coupled to higher resolution mass analysis techniques. Valet parking efficiencies up to 46% were demonstrated here, though the RF coupling between quadrupoles in the platform used here limited performance. As discussed above, performing valet parking at a higher q-value could significantly (up to a factor of 2) improve transfer efficiencies and mass selectivity. The gas-phase purification and concentration of a simple protein mixture demonstrates one application of valet parking. Implementation of valet parking is attractive for several applications and offers a means to impede ion/molecule reaction progression in a mass selective fashion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grant GM R37-45372 and by Sciex. The authors would like to acknowledge Jim Hager and Eric Dziekonski of Sciex for helpful discussions throughout this work.

References

- 1.Wilm M: Principles of Electrospray Ionization. Mol. Cell. Proteom 10, M111.009407 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee S, Mazumdar S: Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: A Technique to Access the Information beyond the Molecular Weight of the Analyte. Int. J. Anal. Chem 2012, Article ID 282574 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogorzalek Loo RR, Lakshmanan R, Loo JA: What Protein Charging (and Supercharging) Reveal about the Mechanism of Electrospray. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 25, 1675–1693 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLuckey SA, Goeringer DE: Ion/Molecule Reactions for Improved Effective Mass Resolution in Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 67, 2493–2497 (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson JL Jr, McLuckey SA: Charge manipulation for improved mass determination of high-mass species and mixture components by electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom 33, 664–672 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLuckey SA, Glish GL, Van Berkel GJ: Charge determination of product ions formed from collision-induced dissociation of multiply protonated molecules via ion/molecule reactions. Anal Chem. 63, 1971–1978 (1991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herron WJ, Goeringer DE, McLuckey SA: Product Ion Charge State Determination via Ion/Ion Proton Transfer Reactions. Anal. Chem 68, 257–262 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coon JJ, Ueberheide B, Syka JEP, Dryhurst DD, Ausio J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF: Protein identification using sequential ion/ion reactions and tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 9463 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid GE, Shang H, Hogan JM, Lee GU, McLuckey SA: Gas-Phase Concentration, Purification, and Identification of Whole Proteins from Complex Mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc 124, 7353–7362(2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He M, Reid GE, Shang H, Lee GU, McLuckey SA: Dissociation of Multiple Protein Ion Charge States Following a Single Gas-Phase Purification and Concentration Procedure. Anal. Chem 74, 4653–4661 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenger CD, Lee MV, Hebert AS, McAlister GC, Phanstiel DH, Westphall MS, Coon JJ: Gas-phase purification enables accurate, multiplexed proteome quantification with isobaric tagging. Nature Methods. 8, 933 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson LC, English AM, Wang W-H, Bai DL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF: Protein derivatization and sequential ion/ion reactions to enhance sequence coverage produced by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 377, 617–624 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huguet R, Mullen C, Srzentić K, Greer JB, Fellers RT, Zabrouskov V, Syka JEP, Kelleher NL, Fomelli L: Proton Transfer Charge Reduction Enables High-Throughput Top-Down Analysis of Large Proteoforms. Anal. Chem 91, 15732–15739 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders JD, Mullen C, Watts E, Holden DD, Syka JEP, Schwartz JC, Brodbelt JS: Enhanced Sequence Coverage of Large Proteins by Combining Ultraviolet Photodissociation with Proton Transfer Reactions. Anal. Chem 92, 1041–1049 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osburn S, Ryzhov V: Ion–Molecule Reactions: Analytical and Structural Tool. Anal. Chem 85, 769–778 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong JY, Hilger RT, Jin C, Yerabolu R, Zimmerman JR, Replogle RW, Jarrell TM, Easterling L, Kumar R, Kenttamaa HI: Integration of a Multichannel Pulsed-Valve Inlet System to a Linear Quadrupole Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer for the Rapid Consecutive Introduction of Nine Reagents for Diagnostic Ion/Molecule Reactions. Anal. Chem 91, 15652–15660 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poad BLJ, Marshall DL, Harazim E, Gupta R, Narreddula VR, Young RSE, Duchoslav E, Campbell JL, Broadbent JA, Cvačka J, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ: Combining Charge-Switch Derivatization with Ozone-Induced Dissociation for Fatty Acid Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 30, 2135–2143 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLuckey SA, Reid GE, Wells JM: Ion Parking during Ion/Ion Reactions in Electrodynamic Ion Traps. Anal. Chem 74, 336–346 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA: Parallel Ion Parking: Improving Conversion of Parents to First-Generation Products in Electron Transfer Dissociation. Anal. Chem 77, 3411–3414(2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA: Parallel Ion Parking of Protein Mixtures. Anal Chem. 78, 310–316 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Londry FA, Hager JW: Mass selective axial ion ejection from a linear quadrupole ion trap. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 14, 1130–1147 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhai Y, Jiang Y, Fang Z, Zhou M, Deng Y, Xu W: Mass Selective Ion Transfer and Accumulation in Ion Trap Arrays. Anal Chem. 86, 10164–10170 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Wang X, Bu J, Zhou X, Ouyang Z: Tandem Analysis by a Dual-Trap Miniature Mass Spectrometer. Anal Chem. 91, 1391–1398 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gronert S: Estimation of effective ion temperatures in a quadrupole ion trap. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 9, 845–848 (1998) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habicht SC, Vinueza NR, Archibold EF, Duan P, Kenttämaa HI: Identification of the Carboxylic Acid Functionality by Using Electrospray Ionization and Ion–Molecule Reactions in a Modified Linear Quadrupole Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer. Anal Chem. 80, 3416–3421 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephenson JL, McLuckey SA: Ion/Ion Reactions in the Gas Phase: Proton Transfer Reactions Involving Multiply-Charged Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 118, 7390–7397 (1996) [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLuckey SA, Stephenson JL, Asano KG: Ion/Ion Proton Transfer Kinetics: Implications for Analysis of Ions Derived from Electrospray of Protein Mixtures. Anal. Chem. 70, 1198–1202(1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson EE; Ion-Molecule Reactions. A. Rev. Phys. Chem 26, 17–38 (1975) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foreman DJ, Dziekonski ET, McLuckey SA: Maximizing Selective Cleavages at Aspartic Acid and Proline Residues for the Identification of Intact Proteins. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 30, 34–44 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holden DD, McGee WM, Brodbelt JS: Integration of Ultraviolet Photodissociation with Proton Transfer Reactions and Ion Parking for Analysis of Intact Proteins. Anal. Chem 88, 1008–1016 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell JL, Le Blanc JCY: Targeted ion parking for the quantitation of biotherapeutic proteins: Concepts and preliminary data. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 21, 2011–2022 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson LC, Karch KR, Ugrin SA, Coradin M, English AM, Sidoli S, Shabanowitz J, Garcia BA, Hunt DF: Analyses of Histone Proteoforms Using Front-end Electron Transfer Dissociation-enabled Orbitrap Instruments. Mol. Cell. Proteom 15, 975 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hager JW: A new linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 16, 512–526 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hager JW Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry with Mass-Selective Axial Ejection In Practical Aspects of Trapped Ion Mass Spectrometry Volume IV Theory and Instrumentation; March RE; Todd JFJ Ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guna M, Biesenthal TA: Performance Enhancements of Mass Selective Axial Ejection from a Linear Ion Trap. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 20, 1132–1140 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.