Abstract

Background:

Despite our awareness of the significant effect of Social Determinant of Health (SDoH) such as Socio Economic Status (SES), income and education on breast cancer survival, there was a serious lack of information about the effect of different level of these factors on breast cancer survival. So far, no meta-analysis has been conducted with this aim, but this gap was addressed by this meta-analysis.

Methods:

Main electronic databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were investigated up to January 2019. Epidemiological studies focusing on the association between SDoH and breast cancer were singled out. Q-test and I2 statistic were used to study the heterogeneity across studies. Begg’s and Egger’s tests were applied to explore the likelihood of the publication bias. The results were reported as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) through a random-effects model.

Results:

We identified 7,653 references and included 25 studies involving 1,497,881 participants. The HR estimate of breast cancer survival was 0.82 (0.67, 0.98) among high level of SES, 0.82 (0.70, 0.94) among high level of income and 0.72 (0.66, 0.78) among academic level of education.

Conclusion:

The SES, income, and education were associated with breast cancer survival, although the association was not very strong. However, there was a significant association between the levels of these factors and breast cancer survival.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Social determinant of health, Meta-analysis, Review

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in developed and developing countries (1). It is the second most common cause of death due to cancer after lung cancer in women (2). According to recent statistics, the incidence of this cancer is increasing globally about 2% per year (3). Increasing of BC survival rate were showed in some studies (4–6). Improved survival rate is probably attributed to progression of treatment and increased screening (7). However, unfortunately, not all women enjoy such an increase in survival rate. This problem can be due to individual differences. Results of previous studies showed that the SDoH had an effect on survival, morbidity, and mortality rate of cancers (8). The diagnostic and therapeutic methods for disease have improved. However, the morbidity, mortality and prevalence of disease has been affected by the SDoH (8). Some of these factors include childhood conditions, social status, addiction, social support, work environment, transportation, etc. (9). Some indices are used for assessing these factors such as the socioeconomic status, level of education, occupation and level of income (10). The survival rate of breast cancer in countries with low level of education is often lower than other countries. The death induced by breast cancer in patients with low levels of education is 1.39 times higher in patients with high levels of education (11). Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of breast cancer patients with low socioeconomic status were lower and poorer than other (12).

Despite our awareness of the effect of some items of SDoH on breast cancer survival, data on effect of different level of these factors on breast cancer survival is scarce. This gap was addressed by this meta-analysis. To date, several studies have been performed on the survival rate of breast cancer and the effect of SDoH on it (13–16). Despite the existence of these primary studies, no meta-analysis has been performed yet to investigate the effect of SDoH on breast cancer survival rate. This meta-analysis conducted to explore the prospective cohort studies, carried out in diverse settings, to assess the extent of effect of some SDoH factors on breast cancer survival rate.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was approved and funded by the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Inclusion criteria

Cohort studies focusing on the survival rate of patients suffering from breast cancer were put into this meta-analysis, irrespective of publication date, language, age, nationality, religion, and race. The search was not in terms of language, but all the selected appropriate references in this meta-analysis were in English. One outcome was considered: the effect of some items of SDoH (included: education level, income and Socio Economic Status (SES)) on survival rate of breast cancer.

A case of breast cancer was specified with kind of tissue cancer that chiefly deals with the inner layer of milk glands or lobules, and ducts (tiny tubes that carry the milk) (17). As specified with WHO, The SDoH cover the major features of life and job like SES, employment, insurance status, education, and race influencing one’s health both directly and indirectly (18).

Search methods

The following keyword set was used to develop the search strategy: (survival or survive or mortality or death) and (breast cancer or breast malignancy or breast tumor or breast neoplasm) and (cohort, retrospective, prospective, or follow-up or longitude) and (education level or income or employment or job or economic stability or food security or SDoH). Electronic databases including PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched until January 2019. To find extra references, the reference lists of all included studies were explored. Additionally, the authors of the selected studies were called for extra-unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (MT and AAH) made the independent decision as to which studies should be put into this meta-analysis according to the study inclusion criteria. The probable disagreements were handled by discussion between the authors until reaching consensus. The kappa statistic for between-author reliability was 83%. Two authors (MT and AAH) extracted the data from the included studies. Once more, the probable disagreements were handled by discussion between the authors until reaching consensus. The variables extracted for analysis included first author’s name, year and country of study, mean (range) age, study design, controlling for confounding (adjusted, unadjusted), sample size, items of SDoH and effect size associated 95% of confidence interval (CI).

Methodological quality

Newcastle Ottawa Statement (NOS) Manual (19) was applied to examine the included studies in terms of the reporting quality. The NOS scale has a checklist of items to determine the risk of bias in the included studies and assigns a maximum of nine stars to the following domains: selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome. In this meta-analysis, the studies having seven star items or more were high-quality studies and those having six star items or less were low-quality ones.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

Statistical heterogeneity was explored using chi-squared test at the 95% of significance level (P < 0.05). Inconsistency between the results of studies was quantified using I2 (20). The Begg’s (21) and Egger’s (22) tests were used to check the likely publication bias. The survival rate (P) and its related 95% of confidence interval (CI) were shown as measures of survival rate from breast cancer influenced by each items of specified SDoH through a random-effects model (23). All statistical analyses were carried out at a significance level of 0.05 by Stata software (Version, 11, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Summary measures

We reported the relationship between some items of SDoH and breast cancer survival using hazard ratio (HR) with their 95% of confidence intervals (CI). Wherever reported, we applied the adapted form of HR measured for three potential confusing factors included age, race, and tumor size.

Results

Description of studies

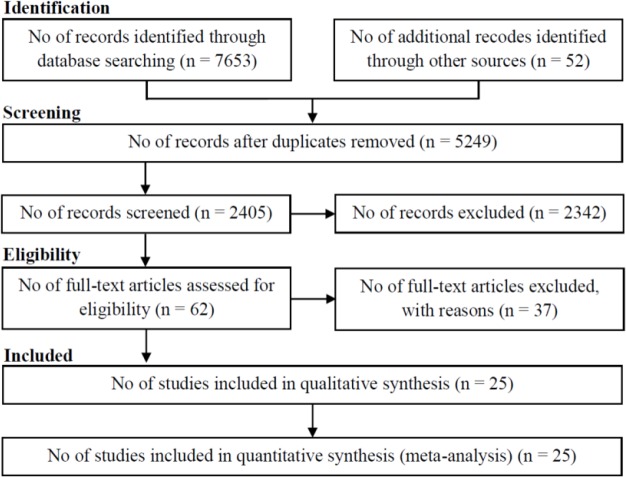

The search singled out 7653 studies involving 7602 references from electronic databases, and 52 references from reference lists. Overall, 5249 duplicates, 2342 references were unrelated by reading titles and abstracts, and 37 references not fulfilling the inclusion criteria were left out. Thus, 25 studies, including 1,497,881 participants, were put into this meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The features of the selected studies are shown in Table 1. Of the 25 selected studies in this meta-analysis, all had a cohort design; 22 were prospective (13–16, 24–41) and 3 retrospective (42–44).

Fig. 1:

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review

Table 1:

Summary of studied articles

| First author (yr) | Country | Design | Mean age (years) | Effect size | Sample size | NOS quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal, Sh 2017 | USA | Prospective | 69.7 | Hazard Ratio | 362797 | ******* |

| Angeles, A 2016 | Mexic | Retrospective | 69.3 | Hazard Ratio | 854 | ******** |

| Arias-Oritz, N 2018 | Colombia | Prospective | 63.4 | Hazard Ratio | 375 | ****** |

| Brooke, H 2017 | Sweden | Prospective | 72 | Hazard Ratio | 14231 | ******* |

| Chang, Ch 2012 | Taiwan | Prospective | 57.6 | Hazard Ratio | 3223 | ***** |

| Dabbikeh, A 2017 | Canada | Retrospective | 59.3 | Hazard Ratio | 920334 | ******* |

| Dalton, S 2007 | Denmark | Prospective | 76.5 | Hazard Ratio | 25897 | ******* |

| Davoudi, E 2017 | Iran | Prospective | 62.5 | Hazard Ratio | 797 | ******** |

| Diniz, R 2016 | Brazil | Prospective | 71.3 | Hazard Ratio | 459 | ******* |

| Du, X 2008 | USA | Prospective | 74.9 | Hazard Ratio | 35029 | ***** |

| Eaker, S 2009 | Sweden | Prospective | 71.5 | Hazard Ratio | 9908 | ****** |

| Feller, A 2017 | Swiss | Prospective | 57.5 | Hazard Ratio | 10915 | ******* |

| Gajalakshmi, CK 1997 | India | Prospective | 76.9 | Hazard Ratio | 2080 | ******* |

| Goldberg, M 2015 | Israeel | Prospective | 60.2 | Hazard Ratio | 21034 | ******** |

| Hastert, T 2015 | USA | Prospective | 58.5 | Hazard Ratio | 25260 | ****** |

| Hussain, Sh 2008 | Sweden | Prospective | 68.4 | Hazard Ratio | 5718 | ***** |

| Lagerlund, M 2005 | Sweden | Prospective | 79.1 | Hazard Ratio | 8230 | ****** |

| Lan, N 2013 | Vietnam | Retrospective | 64.5 | Hazard Ratio | 799 | ******* |

| Larsen, S 2015 | Danmark | Prospective | 63.5 | Hazard Ratio | 1229 | ******* |

| Miki, Y 2014 | Japan | Prospective | 62.7 | Hazard Ratio | 22458 | ******** |

| Rezaianzadeh, A 2009 | Iran | Prospective | 69.9 | Hazard Ratio | 1148 | ***** |

| Schrijvers, C 1995 | Netherland | Prospective | 68.8 | Hazard Ratio | 3928 | ****** |

| Shariff, S 2015 | USA | Prospective | 60.8 | Hazard Ratio | 9372 | ******* |

| Stavraky, K 1996 | Canada | Prospective | 54.9 | Hazard Ratio | 575 | ******** |

| Teng, A 2017 | New Zealand | Prospective | 59.3 | Hazard Ratio | 11231 | ******* |

Results of the search

In this study, 10,687 references were recognized involving 10,159 references by the electronic searches and 528 by screening reference lists or calling the target authors up to July 2015. Overall, 3590 duplicates were left out and 7003 obvious unrelated references by reading titles and abstracts. Hence, 94 references remained for further assessment. Sixty references were left out because of not fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Thirty-four studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). NOS manual was applied to explore the selected studies in terms of reporting quality. Based on this scale, 15 studies were high quality (13, 14, 16, 26–28, 31–33, 36, 39, 40, 42–44) and 10 studies were low quality (15, 24, 25, 29, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41).

Synthesis of results

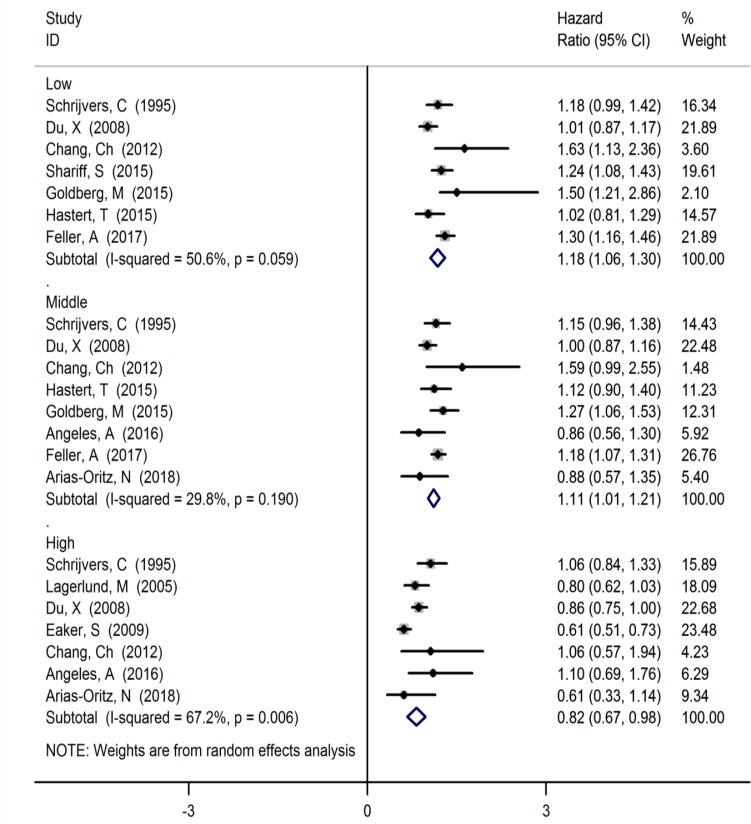

The relationship between breast cancer survival and some items of SDoH is given in Figs. 2–4. Based on these forest plots, the HR estimate of breast cancer survival was 1.18 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.30, I2=50.6%, 7 studies) among low level of SES, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.21, I2=29.8%, 9 studies) among middle level of SES and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.98, I2=67.2%, 7 studies) among high level of SES (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2:

Forest plot of the relationship between of levels of SES with breast cancer survival

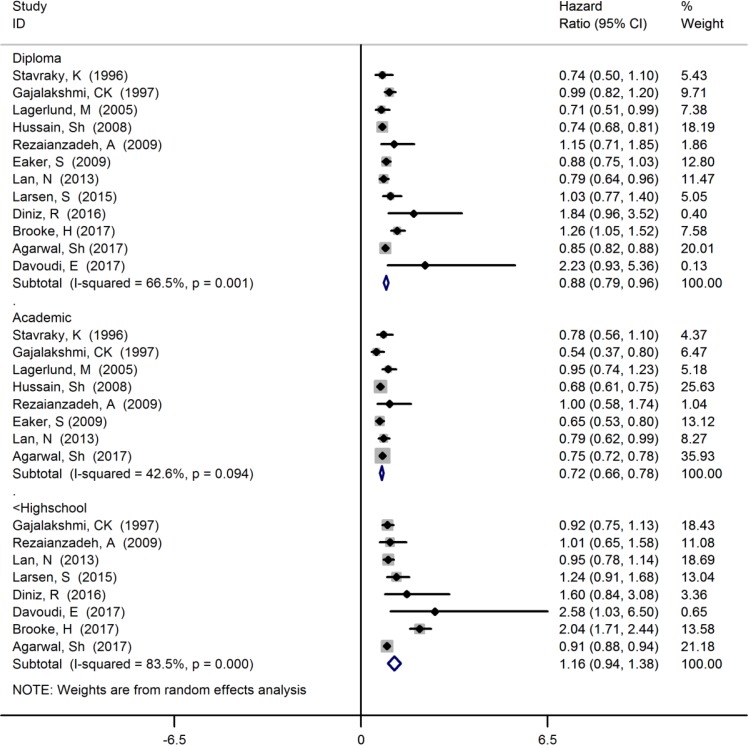

Fig. 4:

Forest plot of the relationship between of levels of education with breast cancer survival

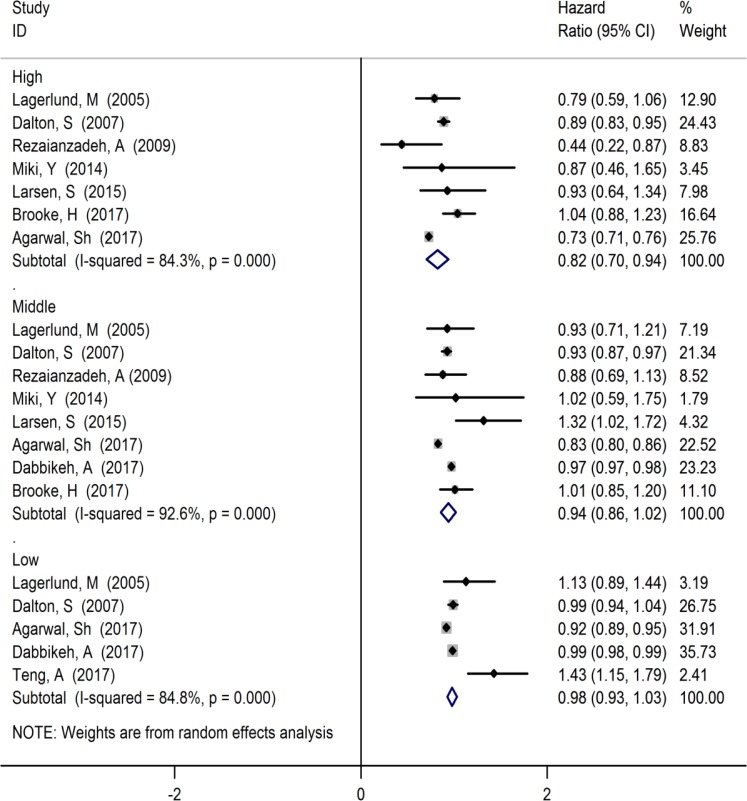

The HR estimate of breast cancer survival was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.03, I2=84.8%, 5 studies) among low level of income, 0.94 (95% CI: 0.86, 1.02, I2=92.6%, 8 studies) among middle level of income and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.70, 0.94, I2=84.3%, 7 studies) among high level of income (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3:

Forest plot of the relationship between of levels of income with breast cancer survival

The HR estimate of breast cancer survival was 1.16 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.38, I2=83.5%, 8 studies) among under the high school level of education, 0.88 (95% CI: 0.79, 0.96, I2=66.5%, 12 studies) among diploma level of education and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.66, 0.78, I2=42.6%, 8 studies) among academic level of education (Fig. 4).

Publication bias

The Begg’s and Egger’s tests were used to examine the likely publication bias that was further visualized by the funnel plot. No indication of publication bias was observed according to the Begg’s test among studies focusing on the breast cancer survival among levels of SES (P=0.414), levels of income (P=0.516), and levels of education (P=0.161). Moreover, according to the results of Egger’s test, there was no evidence of publication bias among studies addressing the breast cancer survival among levels of SES (P=0.573), levels of income (P=0.158), and levels of education (P=0.183).

Discussion

We summarized the available evidence from cohort studies addressing the relationship between some items of SDoH and breast cancer survival. Our results suggested that the high level of SES, income and education were considerably related with higher survival of breast cancer; however, this association was not very strong.

Evidence of heterogeneity was observed in all the included studies but for studies reporting the HR of breast cancer among low and middle levels of SES and academic level of education. The difference between the participants and the risk of bias of the included studies can be used to justify the observed heterogeneity relatively. However, care must be taken in the Q-test interpretation. One of problems of this test may occur in meta-analysis of observational studies with large sample size. The involvement of many studies in a meta-analysis, as in our meta-analysis, means more power of the test to spot a small amount and clinically unimportant of heterogeneity (45). The small within-study variance is one reason that may explain this heterogeneity. In addition, the issue that the studies come from different settings and different populations sample sizes and follow-up periods are the other reasons clarifying the observed heterogeneity across studies relatively.

In this study, an increase in the levels of education leads to an increase in the survival of breast cancer. The effect of levels of education on health status has been performed in previous studies (46). The results of a study expressed that the low education levels was a risk factors for death of breast cancer (47). The levels of education also are related to the levels of income and SES. In other words, the difference in educational levels reflects the difference in SES between individuals. These differences affect the health status of individuals in a variety of ways. Women with higher levels of education show up for screening for breast cancer regularly and frequently (48). As a result, their cancers will be diagnosed sooner. In the present study, the association between SES and BC survival was significant. This association also was significant in various studies. The dose-response relationship between SES and education levels with BC survival were showed in this study. The BC survival increased with the increasing the SES and education levels. The dose-response relationship is an important criterion of causality. In a study, the education levels had a positive effect on BC survival. In addition, the BC patients with higher SES had a more survival (49). Another study evaluated the SES effect on survival of breast cancer in young Australian urban women. It showed that the HR estimate of BC recurrence in women with academic education compared to incomplete high school education was 1.51; however, it was not significant. In addition, there was not association between SES and BC survival that was not consistent with our findings (50). In a study conducted by Aziz et al. the patients with BC were divided to three groups (low, middle, and high SES). The lower SES had an effect on BC survival. In addition, the association between education levels and BC survival was determined (51). There was SES inequality in BC survival rate (52). The diagnosis and screening of breast cancer related to SES levels and increased the BC survival.

Moreover, these individuals are often at higher levels of income and can receive the best health care services easily and quickly. The survival rate of breast cancer is associated with comprehensive treatment. In addition, individuals with higher levels of education study more; therefore, they have more information about screening, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

The lower use of mammography screening leads to higher late stage diagnosed cancers and lower the survival rate. The survival of cancer also is affected by age at diagnosis and tumor progression. In this study, the effect of the SES, income, and education levels on survival rate of breast cancer calculated with adjust for age and tumor progression.

There were some limitations in this study as follows: i) the primary objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the effect of all items of SDoH on breast cancer survival, but because of restricted number of studies for other items (employment, access to health center, economic stability and food security), finally we only included these three items (SES, education and income). ii) Other limitations of this study included inadequate prospective cohort study, low-quality studies, and unavailability of the studies for diverse reasons like outdated studies and not printed electronic papers. iii) We performed subgroup analysis to assess the effect of different level of SES, education and income (low, middle, high) on breast cancer survival. Nevertheless, the number of studies in some subgroups restricted. This probably influenced the reliability of the results of subgroup analyses. Regardless of these limitations, this meta-analysis could find evidences of association between breast cancer survival and SES, education and income.

In addition, this meta-analysis indicated an apparent relationship between the levels of SES, education and income with breast cancer survival. The amount of studies and body of identified evidence made a robust conclusion possible regarding the objective of the study for estimating the effect of these items of SDoH; seemingly, it is not probable that further research would change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Conclusion

The levels of SES, education and income were significantly associated with breast cancer survival, although these associations were not very strong. Nevertheless, this issue justifies that increased level of these factors may help increased the survival of cancers including breast cancer.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of PhD thesis of Dr. Majid Taheri in the field of Medical Sociology funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. (2013). Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer, 132(5):1133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaorsky NG, Churilla TM, Egleston BL, et al. (2017). Causes of death among cancer patients. Ann Oncol, 28(2): 400–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeSantis C, Siegel R, Bandi P, Jemal A. (2011). Breast cancer statistics, 2011. CA Cancer J Clin, 61(6): 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz de la Noval B, Frias Aldeguer L, et al. (2018). Increasing survival of metastatic breast cancer through locoregional surgery. Minerva Ginecol, 70(1): 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo F, Kuo YF, Shih YCT, et al. (2018). Trends in breast cancer mortality by stage at diagnosis among young women in the United States. Cancer, 124(17): 3500–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimura A, Ito H, Nishino Y, et al. (2018). Recent Improvement in the Long-term Survival of Breast Cancer Patients by Age and Stage in Japan. J Epidemiol, 28(10): 420–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. (2005). Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med, 353(17):1784–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Link BG, Phelan JC. (1996). Understanding sociodemographic differences in health--the role of fundamental social causes. Am J Public Health, 86(4): 471–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maia MF, Kliner M, Richardson M, Lengeler C, Moore SJ. (2018). Mosquito repellents for malaria prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2:CD011595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly MP, Bonnefoy J, Morgan A, Florenzano F. (2006). The development of the evidence base about the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouchardy C, Verkooijen HM, Fioretta G. (2006). Social class is an important and independent prognostic factor of breast cancer mortality. Int J Cancer, 119(5):1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooke HL, Weitoft GR, Talbäck M, et al. (2017). Adult children’s socioeconomic resources and mothers’ survival after a breast cancer diagnosis: A Swedish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open, 7(3): e014968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S, Ying J, Boucher KM, Agarwal JP. (2017). The association between socioeconomic factors and breast cancer-specific survival varies by race. PLoS One, 12(12): e0187018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain SK, Altieri A, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. (2008). Influence of education level on breast cancer risk and survival in Sweden between 1990 and 2004. Int J Cancer, 122(1): 165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miki Y, Inoue M, Ikeda A, et al. (2014). Neighborhood Deprivation and Risk of Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Survival: Results from a Population-Based Cohort Study in Japan. PLoS One, 9(9): e106729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ataollahi MR, Sharifi J, Paknahad MR, Paknahad A. (2015). Breast cancer and associated factors: a review. J Med Life, 8(Spec Iss 4):6–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. (2014). The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep, 129 Suppl 2:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. (2009). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S. (2008). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50(4):1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109):629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials, 7(3): 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arias-Ortiz NE, de Vries E. (2018). Health inequities and cancer survival in Manizales, Colombia: a population-based study. Colomb Med (Cali), 49(1): 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang CM, Su YC, Lai NS, et al. (2012). The combined effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on cancer survival rates. PLoS One, 7(8): e44325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalton SO, Ross L, Düring M, et al. (2007). Influence of socioeconomic factors on survival after breast cancer - A nationwide cohort study of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark 1983–1999. Int J Cancer, 121(11):2524–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davoudi Monfared E, Mohseny M, Amanpour F, et al. (2017). Relationship of Social Determinants of Health with the Three-year Survival Rate of Breast Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 18(4): 1121–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diniz RW, Guerra MR, Cintra JRD, et al. (2016). Disease-free survival in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Rev Assoc Med Bras, 62(5): 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du XL, Fang SY, Meyer TE. (2008). Impact of treatment and socioeconomic status on racial disparities in survival among older women with breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol, 31(2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eaker S, Halmina M, Bellocco R, et al. (2009). Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a National Health Care System (Sweden). Int J Cancer, 124(1): 180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feller A, Schmidlin K, Bordoni A, et al. (2017). Socioeconomic and demographic disparities in breast cancer stage at presentation and survival: A Swiss population-based study. Int J Cancer, 141(8): 1529–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajalakshmi CK, Shanta V, Swaminathan R, et al. (1997). A population-based survival study on female breast cancer in Madras, India. Br J Cancer, 75(5): 771–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg M, Calderon-Margalit R, Paltiel O, et al. (2015). Socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer incidence and survival among parous women: findings from a population-based cohort, 1964–2008. BMC Cancer, 15:921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hastert TA, Beresford SAA, Sheppard L, White E. (2015). Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality by area-level socioeconomic status: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health, 69(2):168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagerlund M, Bellocco R, Karlsson P, Tejler G, Lambe M. (2005). Socio-economic factors and breast cancer survival - A population-based cohort study (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control, 16(4): 419–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen SB, Kroman N, Ibfelt EH, et al. (2015). Influence of metabolic indicators, smoking, alcohol and socioeconomic position on mortality after breast cancer. Acta Oncol, 54(5):780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezaianzadeh A, Peacock J, Reidpath D, et al. (2009). Survival analysis of 1148 women diagnosed with breast cancer in Southern Iran. BMC Cancer, 9: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrijvers CTM, Coebergh JW, Van Der Heijden LH, Mackenbach JP. (1995). Socioeconomic variation in cancer survival in the Southeastern Netherlands, 1980–1989. Cancer, 75(12): 2946–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shariff-Marco S, Yang J, John EM, et al. (2015). Intersection of Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status in Mortality After Breast Cancer. J Community Health, 40(6): 1287–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stavraky KM, Skillings JR, Stitt LW, Gwadry-Sridhar F. (1996). The effect of socioeconomic status on the long-term outcome of cancer. J Clin Epidemiol, 49(10):1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng AM, Atkinson J, Disney G, et al. (2017). Changing socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: Cohort study with 54 million person-years follow-up 1981–2011. Int J Cancer, 140(6): 1306–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angeles-Llerenas A, Torres-Mejia G, Lazcano-Ponce E, et al. (2016). Effect of care-delivery delays on the survival of Mexican women with breast cancer. Salud Publica Mex, 58(2): 237–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dabbikeh A, Peng Y, Mackillop WJ, et al. (2017). Temporal trends in the association between socioeconomic status and cancer survival in Ontario: a population-based retrospective study. CMAJ Open, 5(3):E682–E689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lan NH, Laohasiriwong W, Stewart JF. (2013). Survival probability and prognostic factors for breast cancer patients in Vietnam. Glob Health Action, 6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JPT, Green S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steenland K, Henley J, Thun M. (2002). All-cause and cause-specific death rates by educational status for two million people in two American Cancer Society cohorts, 1959–1996. Am J Epidemiol, 156(1):11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herndon JE, Kornblith AB, Holland JC, Paskett ED. (2013). Effect of socioeconomic status as measured by education level on survival in breast cancer clinical trials. Psychooncology, 22(2): 315–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Damiani G, Basso D, Acampora A, et al. (2015). The impact of level of education on adherence to breast and cervical cancer screening: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med, 81:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Gangnon RE, et al. (2011). Socioeconomic status and survival after an invasive breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer, 117(7):1542–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morley KI, Milne RL, Giles GG, et al. (2010). Socio-economic status and survival from breast cancer for young, Australian, urban women. Aust N Z J Public Health, 34(2):200–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aziz Z, Sana S, Akram M, Saeed A. (2004). Socioeconomic status and breast cancer survival in Pakistani women. J Pak Med Assoc, 54(9): 448–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu XQ. (2009). Socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival: relation to stage at diagnosis, treatment and race. BMC Cancer, 9:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Ross RN, et al. (2018). Disparities in Breast Cancer Survival by Socioeconomic Status Despite Medicare and Medicaid Insurance. Milbank Q, 96(4):706–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]