To the Editor:

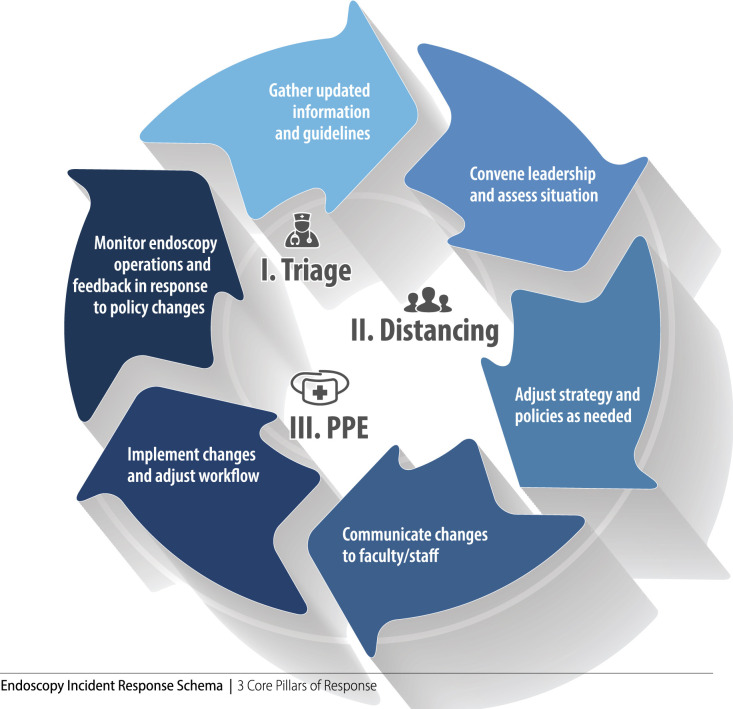

We have read with great interest the paired articles on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2/novel coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) in this issue of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The first, entitled “Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know” by Repici et al,1 describes the Italian experience and the second, “Considerations in performing endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic” by Soetikno et al,2 is drawn largely from the Hong Kong experience. We congratulate the authors for their development and rigorous account of the endoscopic practices they have successfully used to minimize infection of endoscopy staff while providing essential services in this high-risk environment. We would also like to share a U.S. hospital perspective gained from our experience contending with numerous COVID-19 cases after the Biogen conference in Boston, Massachusetts. A COVID-19 standard operating procedure for endoscopy is included in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

COVID-19 endoscopy unit standard operating procedure.

These 2 articles have several similarities and also cover unique aspects regarding the management of COVID-19 in the endoscopy unit. The need for clear communication across the entire endoscopy team, and anesthesia if involved, was emphasized. We also believe a daily huddle with endoscopy leadership is critical to review policies and discuss issues so that all groups are represented in the decision-making process and can deliver the most comprehensive, accurate updates to their staff in this incredibly fluid time when guidelines may change seemingly hour by hour. Creating a step-by-step approach to suspected or COVID-19–positive patients from the time they enter the endoscopy unit to the time they leave and ensuring everyone on the team is on the same page was also addressed. Once the team has created this detailed workflow with clear delineation of who is responsible for each step and whom to call for any necessary equipment that may not be readily available in the endoscopy unit such as powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), mock drills should be conducted with the teams.

The articles also nicely addressed the mandate to minimize nonurgent procedures in an effort to limit the spread of infection from asymptomatic patients and providers and to conserve precious personal protective equipment (PPE), hospital beds, and other important resources. We have classified nonurgent procedures into nonurgent/perform and nonurgent/postpone. Examples of nonurgent cases that may be performed include cancer staging and prosthetic removal. All screening, breath tests, most surveillance, motility, and capsule endoscopy procedures should be delayed. Disposable belt covers and straps should be used for capsule endoscopy. Many diagnostic procedures, including evaluation of chronic GERD, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, may be postponed as well.

Leveraging information technologies can be helpful in these nonstandard workflows. We created custom-built reports for providers within the electronic health record to facilitate triaging and rescheduling patients. The procedure list is reviewed and categorized by a nonphysician healthcare provider, with final review by a physician. The postponed cases are further classified into how long they can wait (1 month, 2 months, 3 months, etc) and classified by which providers can perform the case. Some cases involving complex situations may need multidisciplinary input as well as discussion with the patient before making a final decision. As a result, we have cut our daily endoscopy volume by over 80% and closed our ambulatory endoscopy practice.

For patients who have their elective procedures deferred, a virtual visit in the interim may be helpful in their GI management until their procedure can be safely performed. As part of the State of Emergency response in Massachusetts, telemedicine and virtual visit restrictions have greatly relaxed to promote usage across state lines and include new patient visits. Additionally, these types of visits are now reimbursed at the same rate as in-person visits. At present, telemedicine or virtual visits make up 91% of our upcoming clinic appointments.

Prescreening and categorization of patient risk is emphasized in these articles to identify those who may need COVID-19 testing before endoscopy and special isolation precautions. This includes asking about fever, respiratory symptoms, sick contacts, and travel to high-risk areas, although the latter is increasingly moot with the spread of the pandemic. As nearly 50% of infected patients report GI symptoms, including anorexia in over 80% and diarrhea in nearly 30%, with 3% having only GI symptoms without respiratory issues,3 , 4 we have added these GI symptoms to the list of prescreening questions, as well as recent loss of smell or taste, with importance placed on duration of symptoms.

All scheduled patients are called the day before by nurses for screening, and the same questions are again asked the day of the procedure in addition to measuring patients’ temperature. Our hospital created screening forms integrated into the electronic health record to facilitate standardized screening before procedures. Additionally, our health system reaches out to patients both by automated phone calls and our electronic patient portal advising patients to contact their provider before their visit if they have any symptoms.

The importance of social or physical distancing as advocated recently by the World Health Organization throughout a patient’s time in the endoscopy unit is stressed in the articles, with a 6-foot minimum between individuals. To help meet this requirement, we only allow 1 family member/chaperone per patient who waits in a centralized waiting area, and this visitor cannot enter the pre- or postprocedure areas. Some suggest all patients should wear a mask while in endoscopy. Soetikno et al2 stated that suspected and COVID-19–positive patients should be given a mask and separated from other patients by at least 6 feet or alternatively placed in a negative pressure room. We believe the latter should be emphasized with more stringent and immediate isolation precautions being instituted for these patients and procedures performed in airborne infection isolation rooms that comply with Level 3 biosafety requirements. We also agree with the need for a separate toilet as part of the isolation to minimize spread of infection due to bioaerosols from the toilet plume. If these resources are not available in the endoscopy unit, cases should be performed where the proper facilities are available. These cases should also preferably happen at the end of the day with patients recovered in the procedure room or back in their isolation unit. Consideration may be given to performing urgent procedures at the patient's bedside to minimize these high-risk patients being transported throughout the hospital.

Physical distancing by staff in the endoscopy unit is emphasized in Soetikno et al.2 We believe this is important, especially in areas with community spread. Our hospital system has recently changed policy to mandate that all employees wear surgical masks at all times while in the hospital and attest to their wellness online before reporting to work. Some also recommend checking the temperature of all staff at the beginning of the work shift. We suggest labeling each computer so the same provider uses that computer and chair for the entire day and separating by at least 6 feet. Because many procedure rooms may be empty, 1 provider per day can use these rooms as “offices.” We have converted to obtaining verbal consent by phone or in person (6 feet away) from patients and not having patients physically sign consent forms. Pens, clipboards, phones, and chairs should not be shared. If unsure, these items should be cleaned before use and hand hygiene performed after use. Deep cleaning of the entire endoscopy unit is recommended nightly. Following procedures on suspected or COVID positive patients, staff should shower and change into new scrubs. Before leaving from work, providers should remove scrubs and wear regular clothes outside the hospital. Some even suggest changing out of these clothes into fresh clothes before entering the home.

Both articles emphasize that all endoscopic procedures (upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, EUS, ERCP) are aerosol-generating, referencing studies that show contamination of the endoscopist’s face shields during routine procedures. This makes all endoscopic procedures high risk from an infectious standpoint, and appropriate PPE is recommended. This is an important point. N95 face masks are recommended for high-risk patients undergoing any endoscopic procedure with a standard surgical mask recommended for low-risk patients. However, we believe there is a spectrum of risk severity that is regional and temporal in nature. In a pandemic where asymptomatic transmission is known to occur, significant under-testing continues, and society is expected to practice extreme physical distancing with closure of nonessential businesses, are there any truly low-risk patients? Remember that COVID-19 is believed to be at least 3 times as contagious as the flu virus, and recent reports out of China estimate that as many as 44% of transmissions could occur involving asymptomatic patients.5 This begs the question of whether all endoscopy patients should be considered high-risk in areas of active community spread. It makes little sense for healthcare providers to perform aerosolizing procedures, with patients coughing or passing gas on them, while not wearing an N95 mask or better.

We believe it is important to use full PPE for all endoscopic procedures while in a pandemic such as this, especially in areas where community mitigation strategies are being implemented, as no one is truly low risk given our ongoing difficulties with testing. A study from China showed that no medical staff working in high-risk departments who wore N95 masks and practiced strict hand hygiene regardless of patient infection status became infected.6 Ideally, an N95 mask and face shield should be used with other standard PPE for all endoscopy cases and PAPRs for known COVID-19–positive cases if the case absolutely cannot be deferred. The suggestion to use PAPRs for COVID-19–positive patients comes from China’s anecdotal experience during endoscopic endonasal procedures where infection spread was apparently not controlled with N95 masks and only possible after use of PAPRs. The CDC maintains a list of manufacturers and models of all approved N95 or better respirators, including NIOSH-Approved Air Purifying Respirators which have recently been approved for use in health care settings as part of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency.7

We fully appreciate that PPE is currently in tight supply; however, with careful conservation the above may be possible. It starts with only doing procedures that are absolutely necessary. PPE use should be tightly regulated. Our hospital has gathered all masks and face shields, with every provider signing one out each day as needed. Before this we had a PPE station in the unit where the provider signed out masks using their identification number, employee number, and patient medical record number. The mask can be reused as long as it is functional, not soiled, and not used in a suspected or COVID-19–positive patient. It is important to cover the N95 mask to prevent soiling. We prefer a face shield for this purpose because surgical masks are also running low throughout the country.

A guide to proper extended use and reuse is provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and each institution may have its own policy on this.8 Proper donning and doffing practices should also be followed.9 Some of the important steps to remember include removing dirty gloves first, performing hand hygiene, and putting on clean gloves before later taking off the face shield and N95 without touching the front of either. The face shield should be cleaned with disinfectant wipes before storage. Ultraviolet-C light and vaporized hydrogen peroxide can be effective at disinfecting masks and should be considered.10 Each PPE should be stored in its own paper bag labeled with the provider’s name; therefore, one bag may be for the N95 mask and another for the face shield.

If the use of the N95 mask with all high-risk procedures is not possible, COVID-19 testing to better risk stratify patients before all endoscopy cases may be considered as an alternative, although sensitivity of the test must be considered. Ultimately, testing all patients before high-risk procedures such as endoscopy is likely the best approach; however, this depends on significant expansion of testing capabilities as well as accuracy of the test. Hopefully, the development of highly accurate point-of-care testing with rapid results and increasing testing availability will make this a reality soon.

Additionally, we cannot have 2 levels of PPE used in our endoscopy cases, where anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists wear N95 masks because joint society anesthesia guidelines state they must wear full PPE for all aerosol-generating procedures but the endoscopy team uses only surgical masks.11 Use of Procedural Oxygen Masks (airway masks with apertures for endoscopes) may be prudent for all upper endoscopy procedures to decrease ongoing aerosolization during these procedures.12 Endotracheal intubation may also be considered in these cases to limit ongoing aerosol dispersion. We have also stopped using all topical spray anesthetics to numb the throat in favor of a lidocaine swallow. Other strategies to minimize exposure to aerosols include use of air-tight biopsy valves and limiting accessory device passage.

Other important principles include strategic assignment of available personnel. It is important to minimize concomitant exposure of providers with similar or unique skill sets. Nonphysician practitioners and fellows who cannot participate in cases may help screening and triaging patients or perform virtual visits. We have stopped using fellows to perform procedures with certain exceptions to preserve PPE, minimize exposure, and reduce procedure times. We have been mindful about minimizing the number of providers in the endoscopy unit at one time and are trying to keep the same endoscopist in the unit all day rather than rotating providers. In addition, providers who are at higher risk because of their age, comorbidities, or immune status have been reassigned to other tasks, including virtual visits and triaging. Because of the few procedure rooms in current use, our extra nursing staff have been deployed to other areas of great need in the hospital.

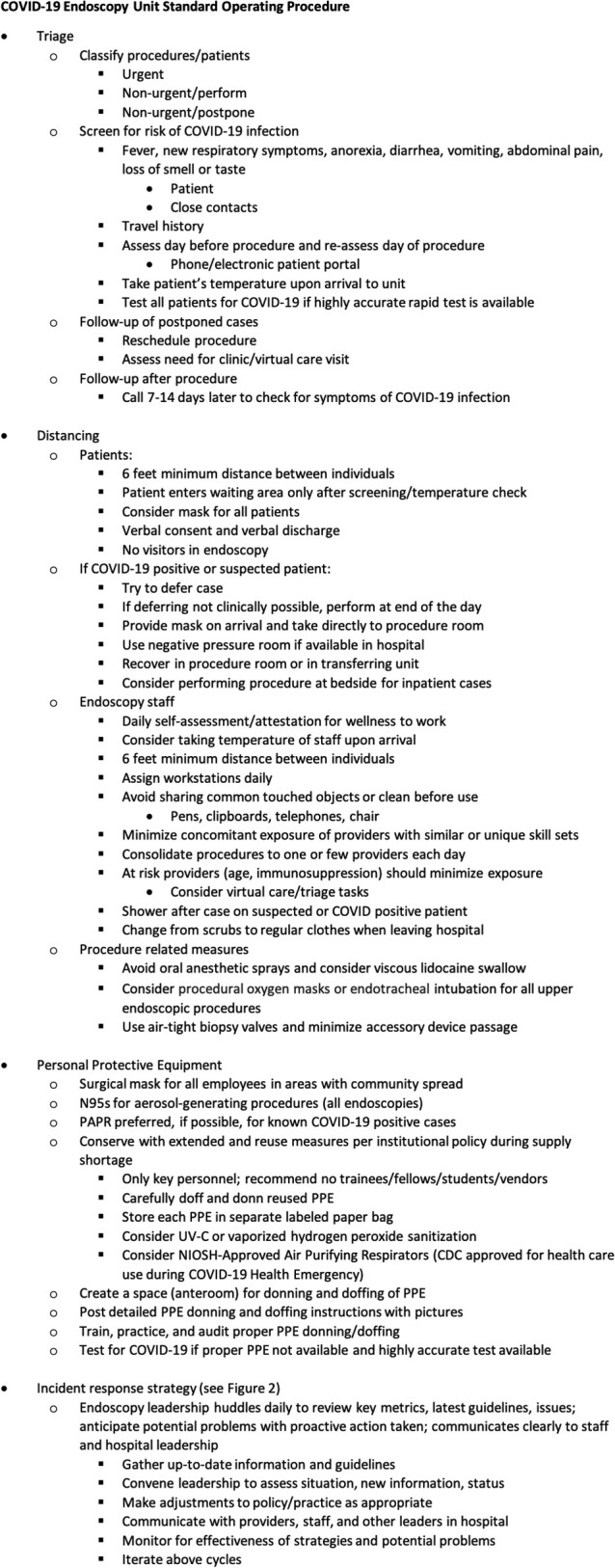

Adopting an incident response mentality is critical to endoscopy leadership during a time when providers and staff are asked to embrace significantly altered workflows, and both the situation and guidelines are constantly shifting (Fig. 2 ). The foundation of this process is having good information upon which the best decisions can be made. This information flow includes having reliable top-down information from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, state and local departments of public health, medical societies, and departmental and hospital leadership as well as accurate assessment of relevant metrics specific to the endoscopy unit. For the latter, a combination of automated means through software and manual workflows can be used to gather important data. Initial considerations may include number of symptomatic staff, number of available reserve staff, number of active procedure rooms, local epidemiology and anticipated case burden (inpatient and outpatient), stocks of PPE, and the case composition of scheduled patients, among others. Additionally, what is considered pertinent data may change over time as the pandemic evolves. It is vital to keep monitoring these metrics throughout the COVID-19 period so that any signals of potential problems can be detected early and more proactive strategies deployed. We recommend regular meetings of endoscopy leadership to review relevant information and plan in an anticipatory fashion. Last, having an upstream communication channel to hospital leadership is important, especially related to information that can affect the safety of patients and staff.

Figure 2.

Three pillars of endoscopy SOP in COVID-19: triage, distancing, PPE. Constant assessment, adjustment, and reassessment (arrows) critical to real-time modification of SOP based on changing circumstances. See Figure 1 for details of each component.

We are living through an unprecedented time and are all trying our best to protect our patients and ourselves under suboptimal conditions of limited PPE, limited testing, and limited data. However, we must continue to do the best we can, thinking creatively and strategically, planning carefully, and proceeding judiciously. It is our collective responsibility to flatten the curve as soon as possible, which can only occur through our individual actions.

Disclosure

The following author disclosed financial relationships: C. C. Thompson: Consultant for Apollo Endosurgery, Boston Scientific, Medtronic/Covidien, Fractyl, GI Dynamics, Olympus/Spiration, and USGI Medical; research support from Apollo Endosurgery, Aspire Bariatrics, Boston Scientific, GI Dynamics, Olympus/Spiration, Spatz, and USGI Medical; advisory board member for Fractyl and USGI Medical; ownership interest in GI Windows. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Repici A., Maselli R., Colombo M. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soetikno R., Teoh A.Y., Kaltenbach T. Considerations in performing endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. Epub. 2020 Mar 3 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan L., Mu M., Ren H.G. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Documents/COVID_Digestive_Symptoms_AJG_Preproof.pdf. Accessed: March 31, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. medRXiv (2020 Mar 18). Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.15.20036707v2. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 6.Wang X, Pan Z, Cheng Z. Association between 2019-nCoV transmission and N95 respirator use. J Hosp Infect. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3214288. Accessed March 3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.CDC. CDC - NPPTL - NIOSH-approved particulate filtering facepiece respirators. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/disp_part/default.html. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 8.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Filtering out confusion: frequently asked questions about respiratory problems. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2018-128/pdfs/2018-128.pdf?id=10.26616/NIOSHPUB2018128. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 9.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Protecting healthcare personnel. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/ppe.html. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 10.Viscusi DJ, Bergman MS, Eimer BC, et al. Evaluation of five decontamination methods for filtering facepiece respirators. Ann Occup Hyg 2009;53:815-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Public Relations. AANA, ASA, APSF. AANA, ASA and APSF issue joint statement on use of personal protective equipment during COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.aana.com/home/aana-updates/2020/03/20/aana-asa-and-apsf-issue-joint-statement-on-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 12.American Society of Anesthesiologists. Clinical FAQs coronavirus (2019-nCoV) COVID-19. Available at: https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/governance-and-committees/asa-committees/committee-on-occupational-health/coronavirus/clinical-faqs. Accessed March 30, 2020.