Abstract

Background

Human neural stem cell implantation may offer improved recovery from stroke. We investigated the feasibility of intracerebral implantation of the allogeneic human neural stem cell line CTX0E03 in the subacute—chronic recovery phase of stroke and potential measures of therapeutic response in a multicentre study.

Methods

We undertook a prospective, multicentre, single-arm, open-label study in adults aged >40 years with significant upper limb motor deficits 2–13 months after ischaemic stroke. 20 million cells were implanted by stereotaxic injection to the putamen ipsilateral to the cerebral infarct. The primary outcome was improvement by 2 or more points on the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) subtest 2 at 3 months after implantation.

Findings

Twenty-three patients underwent cell implantation at eight UK hospitals a median of 7 months after stroke. One of 23 participants improved by the prespecified ARAT subtest level at 3 months, and three participants at 6 and 12 months. Improvement in ARAT was seen only in those with residual upper limb movement at baseline. Transient procedural adverse effects were seen, but no cell-related adverse events occurred up to 12 months of follow-up. Two deaths were unrelated to trial procedures.

Interpretation

Administration of human neural stem cells by intracerebral implantation is feasible in a multicentre study. Improvements in upper limb function occurred at 3, 6 and 12 months, but not in those with absent upper limb movement at baseline, suggesting a possible target population for future controlled trials.

Funding

ReNeuron, Innovate UK (application no 32074-222145).

Trial registration number

EudraCT Number: 2012-003482-18

Keywords: stroke, stem cells, human neural stem cells

Background

Stroke is the second most common cause of death and the primary cause of long-term adult disability.1 Cell therapies may modify early brain injury, or may enhance subsequent recovery from stroke through mechanisms that include modulation of inflammation, neural plasticity and neovascularisation via secretion of cytokines, growth and other factors in response to injury.2 Prior clinical studies have explored safety and feasibility of stem cell administration in either early subacute or chronic stages. Intravenous or intra-arterial administration of bone marrow or peripheral blood-derived cells of various kinds have been delivered predominantly in the subacute phase days to weeks after stroke, intended to modulate early secondary brain injury through systemic action. This has been explored in several small feasibility studies3–8 and in two completed randomised trials of insufficient size to reliably determine efficacy.9 10 In chronic stroke, intracerebral delivery of allogeneic cells of various types has been explored.11–13

The human neural stem cell line CTX0E03 modifies the local inflammatory response, and in animal models promotes both host cell neurogenesis after stroke, and host cell angiogenesis after limb ischaemia.14 15 CTX0E03 cells injected 4 weeks after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats showed a dose-dependent11 and implantation site-16dependent improvement in behavioural outcome along with histological evidence of increased host striatal angiogenesis13 and neurogenesis.14 Preclinical observations suggest that implanted CTX0E03 cells enhance tissue repair in vivo.14 15 17

In a phase I safety trial, 11 patients with stable, moderate to severe functional neurological impairments after ischaemic stroke underwent intracerebral implantation of CTX0E03 cells an average of 30 months after stroke in doses of up to 20 million cells.11 No cell-related safety issues were observed up to 24 months postimplantation, and modest neurological and functional improvements were observed in some patients. Continuing follow-up has identified no cell-related safety issues up to 8 years postimplantation.

We undertook the current study of CTX0E03 cell implantation to explore effects on arm motor function during earlier stages of stroke recovery, gain further safety data and assess practicality of multicentre recruitment.

Methods

We undertook an open-label, single-arm, multicentre study to investigate the motor response of the weak arm following stereotaxic intrastriatal injection of 20 million CTX0E03 cells ipsilateral to a supratentorial ischaemic stroke that had occurred between 2 and 13 months earlier. The study was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

Patient eligibility

Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in the online supplementary material. We included male or non-pregnant female patients aged ≥40 years, with imaging-confirmed supratentorial ischaemic stroke, and with stable arm weakness satisfying both of the following criteria at time of consent: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) Motor Arm score of 2, 3 or 4; and a score of 0 or 1 for test 2 of the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT: grasp a 2.5 cm3 block and move it from the starting position to the target end position).

jnnp-2019-322515supp001.pdf (11.9MB, pdf)

Main exclusion criteria were prior disabling stroke; history of intracranial haemorrhage; other significant functional impairment of the affected arm; contraindications to MRI; life expectancy <12 months; malignancy (except for non-melanoma skin cancer) within the previous 5 years; malignant brain tumours or metastases; current tamoxifen treatment; intermittent oral antispasticity medication.

Sample size

A minimum sample size of 21 treated patients was estimated to ensure that a response rate of ≥20% could not be excluded at the lower one-sided 50% CI for the population mean using the Clopper-Pearson method. The desired minimum response rate was 20% (5/21 subjects) achieving improvement of ≥2 points on ARAT test item 2, for which the probability of spontaneous improvement was predicted to be <5%.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the response (improvement by ≥2 points 3 months after cell implantation) on ARAT item 2. Secondary efficacy outcomes were numbers of participants showing a predefined minimum response on total ARAT score (≥6 points); NIHSS score (≥10 points); Barthel Index (≥9 points); Fugl-Meyer motor score (≥10 points) on either Motor Function Upper Extremity score or Motor Function Lower Extremity score (added in protocol amendment 8) and modified Rankin Scale (mRS, ≥1 grade).

Data were analysed for the overall dataset. Post hoc subgroup analysis was undertaken for primary and secondary efficacy measures in patients grouped by baseline upper limb function defined by NIHSS arm motor score (4 vs 3 or 2).

The study schedule is detailed in online supplementary table 1. Pretreatment assessments occurred from day 28 (±7 days) following the stroke up to 1–14 days prior to implantation of CTX0E03 DP (day 0). Functional outcomes were evaluated 30, 90, 180 and 360 days after treatment.

jnnp-2019-322515supp002.pdf (84.2KB, pdf)

Antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment was withheld for a maximum of 7 days prior to surgery but stroke treatments as determined by the treating clinician otherwise continued throughout. All patients received a minimum 1.5 hours/week physiotherapy directed at the weak arm for 6 weeks. Additional physical and other therapy inputs were delivered according to individual patient needs, determined by the local clinical team.

CTX cells

CTX0E0318 is clonally derived from human fetal cortical neuroepithelial cells and incorporates a retrovirally inserted c-mycERTAM transgene that confers phenotypic and genotypic stability. CTX0E03 drug product (CTX0E03 DP) is a sterile suspension composed of CTX0E03 cells at a passage of ≤37 and formulated in HypoThermosol at a concentration of 5×104 cells/μL. Growth factors and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) used in the manufacturing process are not part of the final formulation. Myc-dependent cell replication is curtailed by removing 4-OHT in cultures, restoring the cells’ capability to differentiate.19 Cryopreserved CTX0E03 DP has a shelf life of 6 months at −135°C and was thawed rapidly at the time of use.

Procedures

Under general anaesthesia, a neurosurgeon experienced in stereotaxic surgery injected a single intracerebral dose of 20 million CTX cells (400 μL CTX0E03 DP) into the putamen ipsilateral to the ischaemic stroke using coordinates and trajectories based on individual preoperative imaging, as previously described.11 20 CTX cells were delivered in 20 μL deposits at a rate of 5 μL /min, pausing for at least 20 s between each bolus. The deepest implant was delivered first and the cannula withdrawn for subsequent boluses along any single trajectory. Five deposits of 20 μL each were placed along each of four needle tracts. Administration of the entire dose was completed within 3 hours of CTX0E03 DP being brought to room temperature.

Protocol evolution

The protocol and amendment history are included as online supplementary material. The initial eligibility criteria required an NIHSS arm score of 2 or 3: this was later amended to include NIHSS arm score of 4 (no movement). The primary endpoint was modified to day 90 from day 180 (amendment 8). Eligibility criteria were modified during the course of the study to remove an upper age limit. The Fugl-Meyer Assessment was added to the protocol and was therefore not conducted in all trial participants. A statistical analysis plan was finalised and approved prior to database lock.

Role of the funding source

ReNeuron funded the study and designed the protocol with input from investigators. An independent contract research organisation managed data collection. Analysis was undertaken by an independent statistician contracted to provide the study report. The funder was not aware of outcomes until database lock. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for submission for publication.

Results

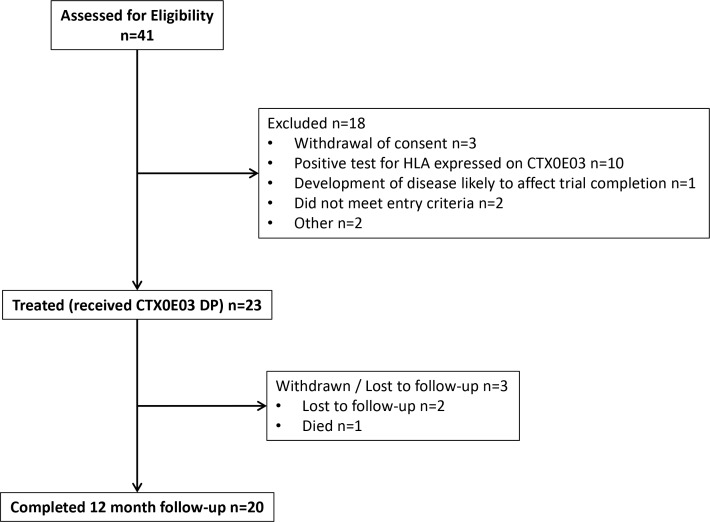

Patients were enrolled and treated between July 2014 and August 2016, and follow-up completed in August 2017. Of 41 patients who underwent screening for eligibility, 23 proceeded to cell injection (figure 1). One patient died before 12-month follow-up (sepsis of unknown cause on day 241), and two others did not attend for 12-month review. Demographics, medical history and baseline stroke characteristics are described in table 1. Baseline ARAT item 2 scores were 0 in 22/23 and 1 in one participant. Successful implantation of CTX0E03 DP was completed in all 23 patients.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition through the study. HLA, human leucocyte antigen. CTX0E03 DP; CTX0E03 Drug Product.

Table 1.

Demographics, medical history and stroke characteristics of participants

| Age (years) | Mean (SD), range | 62.4 (10.8), 41–79 |

| Sex | ||

| Male:female | n (%) | 13 (57): 10 (43) |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | n (%) | 22 (96) |

| Asian | n (%) | 1 (4) |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypertension | n (%) | 12 (52) |

| Atrial fibrillation | n (%) | 5 (22) |

| Previous stroke | n (%) | 5 (22) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | n (%) | 3 (13) |

| Current or previous smoker | n (%) | 16 (70) |

| Diabetes | n (%) | 2 (9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | n (%) | 2 (9) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smoked | n (%) | 7 (30) |

| Previous smoker | n (%) | 13 (57) |

| Current smoker | n (%) | 3 (13) |

| Stroke characteristics | ||

| Onset to enrolment months | Median (IQR), range | 7 (IQR 5), range 2–13 |

| Affected hemisphere | n (%) | Left 9 (39); Right 14 (61) |

| Location of infarct | ||

| Cortical | n (%) | 12 (52) |

| Subcortical | n (%) | 12 (52) |

| Basal ganglia | n (%) | 8 (35) |

| Internal capsule | n (%) | 7 (30) |

| Corona radiata | n (%) | 5 (22) |

| Other | n (%) | 2 (9) |

| Both cortical and subcortical | n (%) | 7 (30) |

| OCSP classification | ||

| TACS | n (%) | 10 (43.48) |

| PACS | n (%) | 8 (34.78) |

| LACS | n (%) | 5 (21.74) |

| NIHSS | Median (range) | 6 (3–15) |

| UL=2 | n (%) | 9 (39) |

| UL=3 | n (%) | 5 (22) |

| UL=4 | n (%) | 9 (39) |

| Barthel Index | Median (range) | 70 (15–100) |

| Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) | Median (range) | 3 (2–5) |

| mRS 2 | n (%) | 3 (13) |

| mRS 3 | n (%) | 11 (48) |

| mRS 4 | n (%) | 8 (35) |

| mRS 5 | n (%) | 1 (4) |

| Fugl-Meyer Assessment (n=8) | Median (range) | |

| UL | 6 (2–22) | |

| Lower limb | Median (range) | 18.5 (2–28) |

| Total Motor Score | Median (range) | 31.5 (4–47) |

| Action Research Arm Test | ||

| Total Score, affected arm | Median (range) | 0 (0–7) |

LACS, lacunar stroke syndrome; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OCSP, signifies Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project; PACS, partial anterior circulation stroke; TACS, total anterior circulation stroke; UL, upper limb.

Numbers of participants exhibiting predefined response criteria are detailed in table 2. Individual patient data are detailed in online supplementary material.

Table 2.

Responders to primary and secondary endpoints

| Response definition | ARAT subtest 2 (grasp) primary outcome | ARAT total response | modified Rankin Scale | Barthel Index | FMA | One or more of ARAT, mRS or BI, (%) |

| ≥2 point improvement, (%) | >6 point improvement, (%) | >1 category improvement, (%) | >9 point improvement*, (%) | >10 point improvement†, (%) | ||

| 3 months | 1/23 (4) | 3/23 (13) | 7/23 (30) | 8/23 (35) | 4/10 (40) | 13/23 (57) |

| 6 months | 3/22 (14) | 4/22 (18) | 6/22 (27) | 7/22 (32) | 13/22 (59) | |

| 12 months | 3/20 (15) | 5/20 (25) | 7/20 (35) | 8/20 (40) | 3/10 (30) | 14/20 (70) |

*Improvement by the specified threshold could not be evaluated in three subjects in whom baseline score was 100 and three subjects in whom baseline score was 95.

†Response on Fugl-Meyer Assessment is ≥10 points on either Motor Function Upper Extremity score or Motor Function Lower Extremity score.

ARAT, signifies Action Research Arm Test; BI, Barthel Index; FMA, Fugl-Meyer Assessment; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Primary endpoint

At 3 months, one patient showed ≥2 points improvement on ARAT item 2. Three patients exhibited a response at 6 and at 12 months: one patient exhibiting a response at 6 months did not achieve the response at 12 months, but had increased scores for other ARAT test items (5 cm3 and 7.5 cm3 blocks).

Secondary Endpoints

Total ARAT score improved at the last observation in 7/23 patients, with individual improvements ranging between 1 and 54 points. Five (22%) patients met the response criterion of improvement by ≥6 points. No participant exhibited a change in total NIHSS score of 10 or more points as defined in the statistical analysis plan therefore this is omitted from table 2; however, only four participants had baseline NIHSS >10. Change in Barthel Index of ≥9 points was seen in 8/20 participants at 12 months, but could not be evaluated in six subjects in whom baseline score was 95 or 100 (ceiling). Fugl-Meyer motor scores were undertaken in only 10 participants and improved by ≥10 points in 3. Improvement in mRS by ≥1 grade was seen in 7/20 participants at 12 months (details in table 2).

Secondary analyses

Responses rates in prespecified assessments were explored with respect to age, time elapsed since stroke and baseline NIHSS arm motor scores. No participant exhibited a response to all four scales at any time point; the number of participants exhibiting a response to 3, 2 or 1 scales was 1, 4 and 8 at 3 months, 2, 3 and 8 at 6 months, and 3, 3 and 8 at 12 months (online supplementary figure 1). Changes in mRS grade were from grade 5 to 3 in one patient; from grade 4 to grade 3 in two patients, both of whom returned to grade 4 at subsequent visits, and one of whom died before the 12 months assessment; grade 3 to grade 2 in five patients and grade 2 to grade 1 in one patient.

At 6 months, 4/22 participants exhibited improvement in either ARAT subitem 2 or total ARAT: the responders were significantly younger (mean 53±6 years vs 64±11 years, p=0.025) but had no differences in time elapsed from stroke to intervention or total baseline NIHSS compared with non-responders. At 12 months, 5/20 participants exhibited ARAT response as above, but no differences were seen in age, baseline NIHSS or time to intervention compared with non-responders.

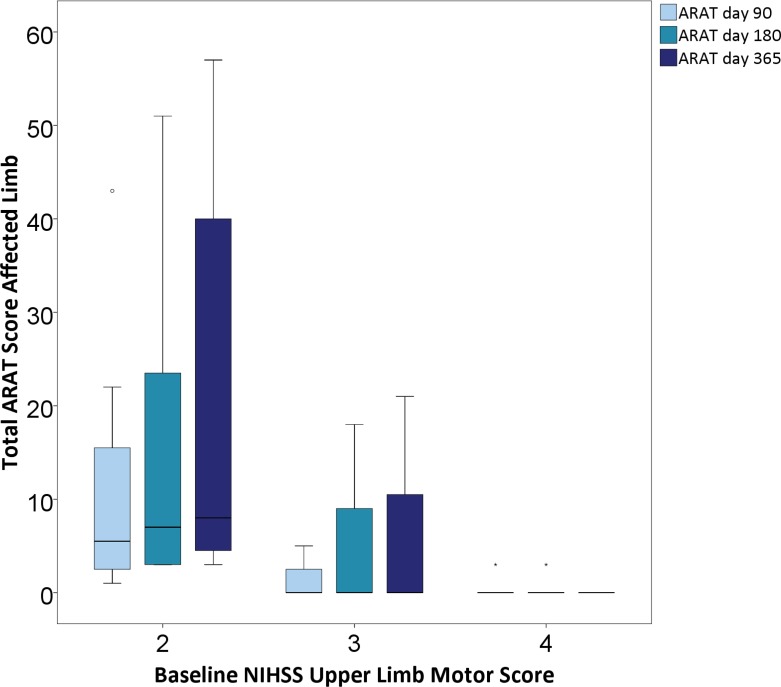

In nine participants, baseline NIHSS arm motor score was 4 (no movement); 14 participants had scores of 2 or 3, signifying at least some movement. Compared with patients with NIHSS arm scores of 2 or 3, patients with no upper limb movement (NIHSS 4) at baseline were significantly older (70±8 vs 57±9 years, p=0.002), had higher total NIHSS scores (median 7.5 (IQR 7) vs 6 (IQR 4), p=0.019) and lower Barthel scores (median 55 (IQR 38) vs 90 (IQR 31), p=0.003), but interval from stroke onset to treatment did not differ (median 8.5 (IQR 5) months vs 7 (IQR 6)). Responses on ARAT item 2 or total score were seen in none of those with baseline NIHSS arm score of 4 (figure 2 and online supplementary table 2). Improvement by one or more grades of the mRS at month 12 was seen in 6/12 (50%) patients with baseline NIHSS 2 or 3, and in 1/8 (12.5%) of those with baseline NIHSS arm score of 4. Individual patient data for all endpoints are detailed in online supplementary table 3. Responses were seen in both those with cortical and isolated subcortical infarcts (online supplementary table 4).

Figure 2.

Median total ARAT score subdivided by baseline NIHSS upper limb motor score. Solid horizontal lines represent median, boxes IQR, error bars maximum and minimum values. ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Safety

There were 17 serious adverse events (SAEs) in 11 patients (table 3). These included two deaths (sepsis on day 241, and completed suicide 7 days after the final study visit) considered unrelated to study procedures. Six SAEs in four patients were considered related to the surgical procedure, all of which resolved. These were: cerebral infarction identified on day 1 postprocedure, in a patient with carotid artery stenosis who had required prolonged general anaesthesia; subdural haemorrhage identified on day 2 postprocedure; headache and vomiting (days 2–4 postprocedure); and partial seizures and sepsis in one participant (day 22 postprocedure) considered by local investigators to be possibly related to CTX0E03 cells. The seizure episode was a single, 1-hour long episode of shaking, commencing focally in one upper limb then spreading to the opposite arm and whole body. The patient was conscious throughout. Onset was concurrent with sepsis. Cerebrospinal fluid screen and culture were both negative, and no source of infection could be confirmed.

Table 3.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurring after surgery during the study period

| System (n subjects) | Event | N events | Timing of SAE start (Days postprocedure) |

| Infections (n=5) | Sepsis | 2 | 22, 241 |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 | 108 | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 1 | 2 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 118 | |

| Viral infection | 1 | 234 | |

| Central nervous system (n=5) | Headache | 2 | 214, 1 |

| Carotid stenosis | 1 | 0 | |

| Hypertonia | 1 | 1 | |

| Ischaemic Stroke | 1 | 1 | |

| Partial seizure | 1 | 22 | |

| Gastrointestinal (n=1) | Vomiting | 1 | 2 |

| Procedural (n=1) | Subdural haemorrhage | 1 | 25 |

| Immunological (n=1) | HLA positivity | 1 | 33 |

| Psychiatric (n=1) | Suicide | 1 | 342 |

| Respiratory (n=1) | Aspiration pneumonia | 1 | 120 |

HLA, signifies human leucocyte antigen.

One patient experienced the serious event of transient, weakly detectable human leucocyte antigen antibody, to antigens which are not expressed by the CTX0E03 cell line, coincident with an intercurrent chest infection 33 days postprocedure. Infection was considered to be the likely stimulus for a non-specific immunological reaction.

Three patients experienced hypotension during the surgery, and two of these also experienced bradycardia, one during the surgery and one during the postoperative inpatient period.

Discussion

This second study of intracerebral CTX0E03 human neural stem cell injection extends the initial clinical data in several important respects. First, the feasibility of a multicentre clinical study was confirmed. The development of frozen cell product was an important technical development since the first Pilot Investigation of Stem Cells in Stroke (PISCES-1) trial to enable this. Second, additional safety data at the 20 million cell dose confirm few potentially cell-related adverse events up to 1 year of follow-up in both male and female participants, and in a wider age range than previously studied. Third, the feasibility of recruitment at earlier time points following stroke has been established. In the previous PISCES-1 study, median time from stroke to cell implantation was 30 months, compared with 7.5 months in the present study. Finally, exploratory data on functional outcome measures indicate both that the responder rate in a population expected to have a low incidence of functionally useful clinical improvement was sufficient to justify further clinical investigation, and that response rates on measures of upper limb function are likely to be poor among patients with completely absent upper limb movement at baseline assessment a median of 7.5 months after stroke. Preliminary data exploring activities of daily living, general disability and motor function suggest a range of suitable clinical outcome measures for future research.

The original study design sought to determine whether a sufficient proportion of patients experienced response of their weak arm 3 months after implantation of CTX0E03 DP to justify further investigation. The intent was to exclude response rates below 20% with 90% CI at this 3 month time point. At the 3-month evaluation, only one patient met criteria for ARAT test 2 response, and so the primary efficacy endpoint was not met. However, additional patients responded at 6 and 12 months suggesting that improvement continues beyond the 3-month time point. Overall, three participants (15% of those who completed 12-month follow-up) achieved an increase of at least 2 points at 12 months, and one further patient responded at 6 months but not at 12 months, although increased scores for the larger sized blocks assessed in the ARAT. Given the arbitrary selection of 3 months as a time point for endpoint evaluation, and absence of safety issues, further evaluation of CTX0E03 DP in randomised clinical trials is justified.

Most stroke patients experience some functional recovery in the first 6 months poststroke,21–23 varying with severity of the initial deficit.24 Patients who improve early have more favourable functional outcome regardless of clinical syndrome, while patients who fail to show significant recovery by day 10 retain significant disability at day 90.25 Prediction models adjusted for the effects of time after stroke onset suggest that outcome is largely defined within the first weeks poststroke.26 Clinical predictors of dexterity at 6 months are severity of initial arm weakness, and arm motor recovery in the first month after stroke, with no further improvement in prediction accuracy beyond this time.26–29 PISCES-2 participants were selected on the basis of poor predicted recovery, yet showed functionally relevant improvement in motor functions. Observations from the current study as well as the previous PISCES-1 study indicate potential worthwhile functional improvements even with intervention occurring in the late subacute or chronic stages after stroke.

The functional improvements observed in the study population are unlikely to have arisen as a consequence of additional physical therapy at the dose delivered, since very much larger doses appear to be necessary for an effect in chronic stroke.30 31 However, the possibility that lower doses of physical therapy interact with stem cell administration could not be excluded. We did not specifically assess other potential confounders that may lead to falsely low motor performance such as pain or perceptual deficits, therefore, cannot completely exclude the possibility that other factors may have been relevant in the observed improvement.

Expert consensus statements on trial reporting standards,32 measurement33 and biomarkers34 were produced after the initiation of PISCES-2, but the trial conformed with many of these recommendations, including the use of NIHSS to characterise stroke severity, ARAT as a measure of upper limb function and the mRS as a measure of global disability. However, the trial framework proposed did not make recommendations regarding stroke recovery studies where the intervention commenced only in the chronic stage of stroke.

Observations in PISCES-2 inform some aspects of future trial design. The ARAT response observed in PISCES-2 was related to the baseline degree of arm motor impairment, with no ARAT responders among those with absence of movement (NIHSS motor arm score of 4) at baseline. Improvements in mRS were also rarely observed in participants with absent arm movement at study entry. The Barthel index has notable ceiling effects that limit its utility, and in keeping with this, six participants could not achieve a response since already scoring near-maximum or maximum scores at baseline.35 Consensus recommendations on appropriate outcome measures from the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable group33 include the ARAT for upper limb function. Previous exploratory work on sample size requirements for motor recovery trials36 assuming a defined minimum clinically important difference (MCID) on ARAT of 6 points was based on a small sample size and early characterisation of patients: it is unclear whether the assumed MCID or changes over time apply in later subacute or chronic stages after stroke. Additional work to characterise predictors of motor response at later time points poststroke would be beneficial in stratifying patients for future trials, particularly where an invasive therapy is involved. Motor response prediction algorithms developed for early poststroke use, which include clinical evaluation supplemented where necessary by transcranial magnetic stimulation to determine the integrity of corticospinal tracts supplying upper limb muscles,37 may not be applicable to later time points and require validation.34 For confirmation of clinically important functional outcome changes in stroke, the modified Rankin Scale has been favoured by regulatory bodies, and our observations support this approach.

There are a number of limitations to this study. The open-label design was adopted due to the early stage of clinical investigation but may bias functional assessments. Future evaluation in a randomised, controlled trial is essential. Small numbers of participants inevitably mean that the heterogeneity of stroke cannot be adequately represented, and means that any interpretation of factors related to functional or neurological response must be extremely cautious. Factors, such as age, medical comorbidities, infarct volume and location, anatomical and functional involvement of the corticospinal tract, time elapsed since the stroke, the anatomical location and distribution of cell deposits, concomitant physical therapy and its intensity, may all contribute significantly to motor and general recovery, and a much larger study would be required to evaluate these. While we observed a low incidence of potentially cell-related adverse events, the total number of patients implanted is small (23 in the current study and 2 at this dose level in PISCES-1) and follow-up period limited.

In conclusion, PISCES-2 provides additional data to support multicentre clinical trials of intracerebral stem cell injection in subacute stages of stroke recovery. Functionally relevant improvement in arm movement was observed in patients with residual upper limb motor function at baseline. Further clinical investigation in a randomised, controlled clinical trial is warranted.

Acknowledgments

AM was partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Sheffield Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and NIHR Sheffield Clinical Research Facility.

Footnotes

Twitter: @dr_nickward

Presented at: International Stroke Conference 2018

Contributors: The trial protocol was designed by JH, PS, KP and JS with input from AM, LD and other clinical investigators. Data were acquired by KWM, DB, MW, NS, AD, NW, PT and LD. PB chaired the data monitoring committee. KWM undertook analyses and drafted the manuscript. The manuscript was critically reviewed by DB, MW, NS, AD, NW, PT, AM, LD, PB, KP and JS.

Funding: This study was funded by ReNeuron Ltd., Innovate UK (application no 32074-222145).

Competing interests: JH, PS, KP and JS are employees of ReNeuron. KWM has participated in advisory boards for ReNeuron and is a member of the trial steering committee for the PISCES-3 trial.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service and Gene Therapy Advisory Committee (references 13/LO1174, GTAC161, 12/LO/1963).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information. All relevant data are included in online suppplementary information.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Neurological Disorders Collaborator Group Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:877–97. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30299-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, et al. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells 2007;25:2739–49. 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suárez-Monteagudo C, Hernández-Ramírez P, Alvarez-González L, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cell neurotransplantation in stroke patients. an open study. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2009;27:151–61. 10.3233/RNN-2009-0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee JS, Hong JM, Moon GJ, et al. A long-term follow-up study of intravenous autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with ischemic stroke. Stem Cells 2010;28:1099–106. 10.1002/stem.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Honmou O, Houkin K, Matsunaga T, et al. Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain 2011;134:1790–807. 10.1093/brain/awr063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhasin A, Srivastava MVP, Mohanty S, et al. Stem cell therapy: a clinical trial of stroke. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013;115:1003–8. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banerjee S, Bentley P, Hamady M, et al. Intra-Arterial immunoselected CD34+ stem cells for acute ischemic stroke. Stem Cells Transl Med 2014;3:1322–30. 10.5966/sctm.2013-0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taguchi A, Sakai C, Soma T, et al. Intravenous autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation for stroke: Phase1/2a clinical trial in a homogeneous group of stroke patients. Stem Cells Dev 2015;24:2207–18. 10.1089/scd.2015.0160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prasad K, Sharma A, Garg A, et al. Intravenous autologous bone marrow mononuclear stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke: a multicentric, randomized trial. Stroke 2014;45:3618–24. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Clark WM, et al. Safety and efficacy of multipotent adult progenitor cells in acute ischaemic stroke (masters): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:360–8. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30046-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalladka D, Sinden J, Pollock K, et al. Human neural stem cells in patients with chronic ischaemic stroke (Pisces): a phase 1, first-in-man study. Lancet 2016;388:787–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30513-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steinberg GK, Kondziolka D, Wechsler LR, et al. Clinical outcomes of transplanted modified bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in stroke: a phase 1/2A study. Stroke 2016;47:1817–24. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.012995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang G, Li Y, Reuss JL, et al. Stable intracerebral transplantation of neural stem cells for the treatment of paralysis due to ischemic stroke. Stem Cells Transl Med 2019;8:999–1007. 10.1002/sctm.18-0220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hicks C, Stevanato L, Stroemer RP, et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of the angiogenic effect of CTX0E03 human neural stem cells. Cell Transplant 2013;22:1541–52. 10.3727/096368912X657936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katare R, Stroemer P, Hicks C, et al. Clinical-Grade human neural stem cells promote reparative neovascularization in mouse models of hindlimb ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:408–18. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith EJ, Stroemer RP, Gorenkova N, et al. Implantation site and lesion topology determine efficacy of a human neural stem cell line in a rat model of chronic stroke. Stem Cells 2012;30:785–96. 10.1002/stem.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hassani Z, O'Reilly J, Pearse Y, et al. Human neural progenitor cell engraftment increases neurogenesis and microglial recruitment in the brain of rats with stroke. PLoS One 2012;7:e50444 10.1371/journal.pone.0050444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sinden JD, Hicks C, Stroemer P, et al. Human neural stem cell therapy for chronic ischemic stroke: charting progress from laboratory to patients. Stem Cells Dev 2017;26:933–47. 10.1089/scd.2017.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pollock K, Stroemer P, Patel S, et al. A conditionally immortal clonal stem cell line from human cortical neuroepithelium for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol 2006;199:143–55. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kondziolka D, Steinberg GK, Wechsler L, et al. Neurotransplantation for patients with subcortical motor stroke: a phase 2 randomized trial. J Neurosurg 2005;103:38–45. 10.3171/jns.2005.103.1.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stinear CM, Byblow WD, Ackerley SJ, et al. Proportional motor recovery after stroke: implications for trial design. Stroke 2017;48:795–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winters C, van Wegen EEH, Daffertshofer A, et al. Generalizability of the proportional recovery model for the upper extremity after an ischemic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015;29:614–22. 10.1177/1545968314562115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langhorne P, Coupar F, Pollock A. Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:741–54. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, et al. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part II: time course of recovery. The Copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995;76:406–12. 10.1016/S0003-9993(95)80568-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sprigg N, Gray LJ, Bath PMW, et al. Stroke severity, early recovery and outcome are each related with clinical classification of stroke: data from the 'Tinzaparin in Acute Ischaemic Stroke Trial' (TAIST). J Neurol Sci 2007;254:54–9. 10.1016/j.jns.2006.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, et al. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke 2003;34:2181–6. 10.1161/01.STR.0000087172.16305.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, et al. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. outcome assessment and sample size requirements. Stroke 1992;23:1084–9. 10.1161/01.STR.23.8.1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heller A, Wade DT, Wood VA, et al. Arm function after stroke: measurement and recovery over the first three months. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:714–9. 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sunderland A, Tinson D, Bradley L, et al. Arm function after stroke. An evaluation of grip strength as a measure of recovery and a prognostic indicator. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989;52:1267–72. 10.1136/jnnp.52.11.1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lohse KR, Lang CE, Boyd LA. Is more better? using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2014;45:2053–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ward NS, Brander F, Kelly K. Intensive upper limb neurorehabilitation in chronic stroke: outcomes from the Queen square programme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019;90:498–506. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walker MF, Hoffmann TC, Brady MC, et al. Improving the development, monitoring and reporting of stroke rehabilitation research: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke 2017;12:472–9. 10.1177/1747493017711815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kwakkel G, Lannin NA, Borschmann K, et al. Standardized measurement of sensorimotor recovery in stroke trials: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke 2017;12:451–61. 10.1177/1747493017711813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boyd LA, Hayward KS, Ward NS, et al. Biomarkers of stroke recovery: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke 2017;12:480–93. 10.1177/1747493017714176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muir KW, Weir CJ, Murray GD, et al. Comparison of neurological scales and scoring systems for acute stroke prognosis. Stroke 1996;27:1817–20. 10.1161/01.STR.27.10.1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winters C, Heymans MW, van Wegen EEH, et al. How to design clinical rehabilitation trials for the upper paretic limb early post stroke? Trials 2016;17:468 10.1186/s13063-016-1592-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stinear CM, Byblow WD, Ackerley SJ, et al. Prep2: a biomarker-based algorithm for predicting upper limb function after stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2017;4:811–20. 10.1002/acn3.488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jnnp-2019-322515supp001.pdf (11.9MB, pdf)

jnnp-2019-322515supp002.pdf (84.2KB, pdf)