Abstract

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disease. Evidence has suggested that probiotics may benefit IBS symptoms. However, clinical trials remain conflicting.

Aims

To implement a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials regarding the efficacy and safety of probiotics for IBS patients.

Methods

We searched for relevant trials in Medline(1966 to Jan 2019), Embase(1974 to Jan 2019), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(up to Jan 2019), the ClinicalTrials.gov trials register(up to Jan 2019), and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database(1978 to Jan 2019). Risk ratio (RR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were calculated for continuous outcomes.

Results

A total of 59 studies, including 6,761 patients, were obtained. The RR of the improvement or response with probiotics versus placebo was 1.52 (95% CI 1.32–1.76), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 71%, P < 0.001). The SMD of Probiotics in improving global IBS symptoms vs. Placebo was -1.8(95% CI -0.30 to -0.06), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 65%, P < 0.001). It was impossible to draw a determinate conclusion. However, there were differences in subgroup analyses of probiotics type, dose, treatment duration, and geographic position. Probiotics seem to be safe by the analysis of adverse events(RR = 1.07; 95% CI 0.92–1.24; I2 = 0, P = 0.83).

Conclusion

Probiotics are effective and safe for IBS patients. Single probiotics with a higher dose (daily dose of probiotics ≥1010) and shorter duration (< 8 weeks) seem to be a better choice, but it still needs more trials to prove it.

Keywords: efficacy, safety, irratable bowel syndrome, probiotics, meta-analysis

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder associated with abdominal pain, bloating and altered bowel habits (Drossman et al., 2002). It affects 11% of the world-wide population (Lovell and Ford, 2012). IBS reduces health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (Gralnek et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2012) and leads to a significant economic healthcare burden. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis underlying IBS are still incompletely understood, studies show that IBS was associated with the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota, chronic low-grade mucosal inflammation, altered regulation of the gut-brain axis, immune function, visceral hypersensitivity, and psychosocial factors(Parkes et al., 2008; Dupont, 2014; Hayes et al., 2014). Since there is no effective cure for IBS, the treatment focuses on alleviating the particular symptoms. New therapeutic options for IBS include tricyclic antidepressants (Rahimi et al., 2009), spasmolytics (Tack et al., 2016), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Bundeff and Woodis, 2014), lubiprostone (Chang et al., 2016) and linaclotide (Chey et al., 2011), and 5-hydroxytryptamine type-3 antagonists such as ramosetron and alosetron (Andresen et al., 2008). However, current treatments are not very useful or may cause adverse reactions (Trinkley and Nahata, 2014).

Evidence (Durban et al., 2013; Jalanka-Tuovinen et al., 2014) has suggested that intestinal microorganisms play an important role in IBS, as numerous studies have indicated that an irregular composition or metabolic activity of intestinal flora in patients with IBS (Simrén et al., 2013; Spiller et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017; Shin et al., 2018). Therefore, the regulation of the gut microbiota by probiotics is a promising treatment for IBS (Hyland et al., 2014). Probiotics can improve intestinal flora and limit colonization of pathogenic bacteria (Guarner et al., 2012). Investigators have performed numerous clinical trials to assess the efficacy of probiotics for IBS. However, the conclusions have been controversial. Some trials have suggested that probiotics can improve global IBS symptoms (Lyra et al., 2016). Others have demonstrated no effect (Charbonneau et al., 2013). Several articles have not found an apparent effect of probiotics on global IBS symptoms, but have found improvement of individual IBS symptoms (Sisson et al., 2014). Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to examine the efficacy of global IBS symptoms improvement, global symptoms scores, and individual symptom scores, such as abdominal pain and bloating. Additionally, this study evaluated the safety of probiotics.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We included all eligible randomized placebo-controlled, trials (RCTs) of probiotics treatment in adult IBS. We searched Medline(1966 to Jan 2019), Embase(1974 to Jan 2019), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(up to Jan 2019), the ClinicalTrials.gov trials register(up to Jan 2019), and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database(CBM) (1978 to Jan 2019) for relevant trials. We used the terms “probiotics” and “irritable bowel syndrome” both as medical subject heading (Mesh) and free text terms. The exact search strategy in Medline was (“probiotics”[MeSH Terms] OR “probiotics”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“irritable bowel syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR “irritable bowel syndrome”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“randomized controlled trial” [pt] OR “randomized controlled trial” [tiab]).

We used the following eligibility criteria: (1) the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing probiotics with placebo; (2) diagnostic criteria included but were not limited to the Manning criteria, and Rome I, Rome II, or Rome III criteria. We did not exclude trials in which patients were stated to be diagnosed with IBS but no diagnostic criteria were described; (3) the age of participants were ≥ 18 years; (4) minimum treatment duration was 7 days. Studies were excluded if they met: (1) studies with inadequate information; (2) probiotics along with other drugs; (3) control group was not placebo; (4) data were not available after contacting the authors. There were no language limitation. Articles in foreign language were translated as needed.

Outcome Assessment

The primary outcomes were the efficacy of probiotics on global IBS symptoms improvement or response to therapy. Secondary outcomes involved the effect on global symptoms scores and individual symptom scores, such as abdominal pain and bloating. The safety of probiotics was also evaluated.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted data from included trials independently. All data was inspected by a third reviewer. Any divergence was solved by consensus. Following data were extracted:author publication year, country, type of IBS(%), diagnostic criteria for IBS, recruitment, sample size, number of male/female, age, probiotic, dosage, duration of therapy, criteria to define symptom improvement or response, and outcomes.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Two reviewers performed the assessment of study quality independently. Disagreements were solved by discussion. The risk of bias were evaluated according to the Cochrane handbook (Higgins and Green, 2011). Random sequence generation and allocation concealment(selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel(performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment(detection bias), incomplete outcome data(attrition bias), selective reporting(reporting bias), and other biases were assessed.

Statistical Analyses

Random effects model was used (Dersimonian and Laird, 1986) to get a conservative estimation for the effect. As dichotomous outcomes, the efficacy on global IBS symptoms improvement or overall symptom response and the safety of probiotics were evaluated by RR(risk ratio) and 95% CIs(confidence intervals). As continuous outcomes, global symptoms scores, and individual symptoms scores were assessed using standardised mean difference (SMD) and corresponding 95% CIs. A negative SMD was defined to indicate beneficial effects of probiotics compared with placebo for outcomes. Subgroup analyses based on probiotic type, dosage, and treatment duration were conducted.

Heterogeneity was tested by I2 statistic and the Cochran Q-test. I2 ≥ 50 and P < 0.10 were considered as a significant heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2003). When there was significant heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were conducted to give possible explanation. Review Manager version 5.3.5 (the Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to obtain forest plots of RRs and SMDs Egger test (Egger et al., 1997) (P < 0.10 defined existence of possible publication bias) and funnel plots was calculated by Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 (StataCorp LP; College Station, TX).

Result

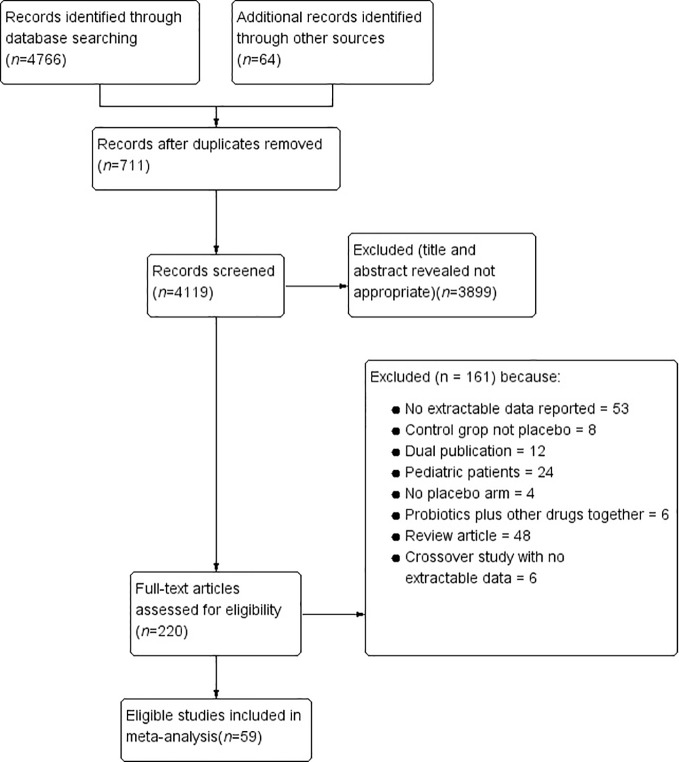

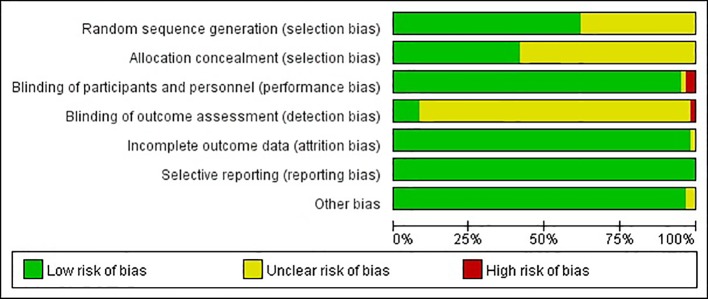

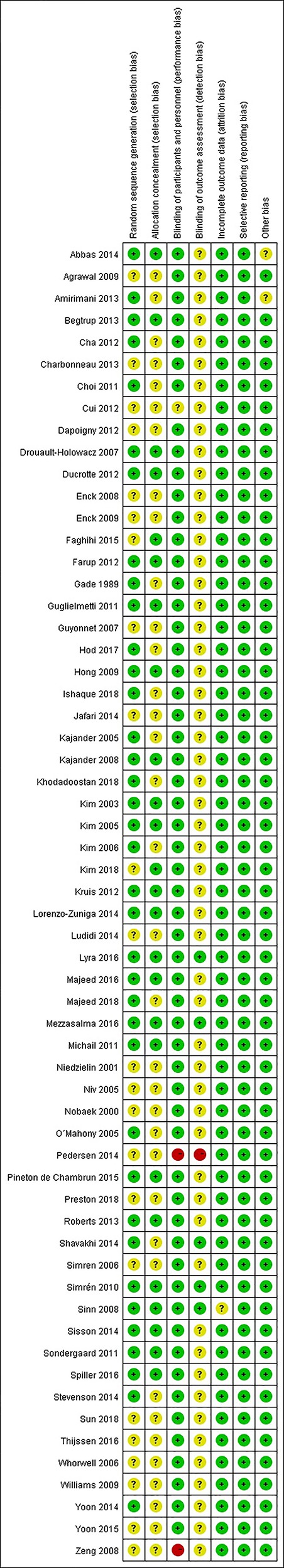

Based on network searching, a total of 4,830 citations were retrieved. By removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 220 studies remained to be relevant ( Figure 1 ). Excluding 161 studies for diverse reasons, 59 studies (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Niv et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2008; Kajander et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Enck et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Farup et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Jafari et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2014; Shavakhi et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Faghihi et al., 2015; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Majeed et al., 2016; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017; Ishaque et al., 2018; Khodadoostan et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018; Preston et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), which contained 6,721 participants, were eligible evaluating. The agreement between the two researchers was well established (kappa value = 0.91). The characteristics of the included RCTs are presented in Table 1 . The risk of bias was shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 . Twenty-three studies did not describe the details of the sequence generation process (Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Niv et al., 2005; Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Enck et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Enck et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Faghihi et al., 2015; Thijssen et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Preston et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), and 35 studies did not describe the method of allocation concealment (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kajander et al., 2005; Niv et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Enck et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Enck et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2014; Shavakhi et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Majeed et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017; Ishaque et al., 2018; Khodadoostan et al., 2018; Preston et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), which lead to an unclear risk of selection bias. The risk of blinding the participants and personnel was low, except two studies (Zeng et al., 2008; Pedersen et al., 2014) were at high risk and one (Cui and Hu, 2012) was unclear. The risk of outcome assessment was mostly unclear. However, one study (Pedersen et al., 2014) was an unblinded controlled trial, leading to a high risk of performance and detection bias. Attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases were low.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials of probiotics versus placebo in irritable bowel syndrome.

| Study | Year | Country | Type of IBS(%) | diagnostic criteria for IBS | recruitment | Sample size | Sex (Male/Female) | Age[years],mean ± SD | Probiotic | Probiotic dosage(CFU/D) | Duration of therapy | Criteria used to define symptom improvement following therapy or response | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | Placebo | |||||||||||||

| Gade and Thorn (1989) | 1989 | Denmark | all types | Manning | Primary care | 54 | 5/27 | 7/15 | 34 | Streptococcus faecium | Not stated | 4 weeks | IBS symptoms “improved” | Improvement in IBS symptoms Adverse events |

| Nobaek et al. (2006) | 2000 | Sweden | all types | Rome I | Advertisement | 52 | 9/16 | 7/20 | 51 | Lactobacillus plantarum | 5×107 | 4 weeks | > 1.5 improvement in VAS scale for abdominal pain, and continuous scale for IBS symptoms |

Abdominal pain(VAS) |

| Niedzielin et al. (2001) | 2001 | Poland | all types | clinical diagnosis | Primary care | 40 | 5/15 | 3/17 | 45 | Lactobacillus plantarum | 2×1010 | 4 weeks | improvement in IBS symptoms | Improvement in IBS symptoms Adverse events |

| Kim et al. (2003) | 2003 | USA | D:100 | Rome II | Secondary care | 25 | 2/10 | 5/8 | 42.8 ± 16.7 | Combination | 9×1011 | 8 weeks | Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms for 50% of weeks, and continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Response(Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms for 50% of weeks) Overall symptoms score Bloating(100-mm VAS) Abdominal pain(100-mm VAS) Adverse events |

| Kajander et al. (2005) | 2005 | Finland | D:48 C:23 A:29 |

Rome I and II | Advertising | 103 | 13/39 | 11/40 | 46 | Combination | 8–9×109 | 6 months | Relief of IBS symptoms, and continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Abdominal pain(a 4-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Kim et al. (2005) | 2005 | USA | D:42 C:33 A:25 |

Rome II | Secondary care and advertising | 48 | 3/21 | 0/24 | 43 | Combination | 9×1011 | 4-8 weeks | Satisfactory relief of IBS symptom for 50% of weeks | Response(Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms for 50% of weeks) Bloating(100-mmVAS) Abdominal pain(100-mmVAS) Adverse events |

| Niv et al. (2005) | 2005 | Israel | D:37 C:18.5 M:44.4 |

Rome II | Secondary care | 54 | 7/20 | 11/16 | 45.6 | L. reuteri ATCC 55730 | 4×108 for 1wk, then 2×108 | 6 months | continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Adverse events |

| O'Mahony et al. (2005) | 2005 | Ireland | D:28 C:26 A:45 |

Rome II | Secondary care | 75 | not stated | 44.3 | L. salivarius UCC4331 or B. infantis 35624 | 1×1010 | 8 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Abdominal pain(7-point Likert score) Bloating(7-pointLikert score) Adverse events |

|

| Kim et al. (2006) | 2006 | Korea | D:70 A:30 |

clinical diagnosis | Secondary care | 34 | 14/3 | 11/6 | 39.35 ± 11.9 | Combination | 3×109(Bacillus subtilis) 2.7×1010(Streptococcus faecium) |

4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Bloating(10-pointVAS) Abdominal pain(10-pointVAS) Adverse events |

| Simren and Lindh (2006) | 2006 | Sweden | all types | Rome II | Advertising | 76 | not stated | 40 | L.plantarum DSM 9843 | 2×1010 | 6 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score(IBS-SSS) | |

| Whorwell et al. (2006) | 2006 | UK | D:55.5 C:20.7 A:23.8 |

Rome II | Primary care | 362 | 0/270 | 0/92 | 41.9 ± 10.46 | B. infantis 35624 | 1×106,1×108,1×1010 | 4 weeks | Subjects' Global Assessment (SGA) of IBS symptoms,and continuous scale symptoms for IBS | Response(SGA) Global symptoms score Bloating(a 6-point numerical scale) Abdominal pain(a 6-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Guyonnet et al. (2007) | 2007 | France | C:100 | Rome II | Primary care | 267 | 29/106 | 39/93 | 49.3 ± 11.4 | Combination | B. animalis DN173010 (1.25×1010 c.f.u./125 g) S. thermophilus (1.2×109 c.f.u./125 g) and L. bulgaricus (1.2×109 c.f.u./125 g) b.i.d. | 6 weeks | improvement at least 10% vs. baseline | Response(improvement at least 10% vs. baseline) Global symptoms score(a 7-pointLikert score) Bloating(a 7-Likert score) Abdominal pain(a 7-Likert score) Adverse events |

| Drouault-Holowacz et al. (2007) | 2007 | France | D:29 C:29 A:41 non-classified:1% |

Rome II | Not stated | 100 | 8/40 | 16/36 | 45.4 ± 14 | Combination | 1 × 1010 | 4 weeks | Satisfactory relief of global IBS symptoms | Satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms Abdominal pain(a 4-pointLikert score) |

| Enck et al. (2008) | 2008 | Germany | all types | Primary care physicians | Primary care | 297 | 77/72 | 73/75 | 49.6 ± 13.6 | Enterococcus faecalis DSM16440 and Escherichia coli DSM17252 | (3.0-9.0×107c.f.u./1.5 ml)×0.75 ml t.i.d. for 1 week, then 1.5 ml t.i.d. for weeks 2 and 3, then 2.25 ml t.i.d. for weeks 3–8 | 8 weeks | 50% improvement in IBS global symptoms,and continuous scale symptoms for IBS | Response(50% improvement in IBS global symptoms) Global symptoms score(GSS) Adverse events |

| Kajander et al. (2008) | 2008 | Finland | D:45 C:30 A:25 |

Rome II | Primary care | 86 | 2/41 | 4/39 | 48 ± 13 | Combination | 1 × 107 | 20 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Flatulence(a 5-point numerical scale) Distension(a 5-point numerical scale) abdominal pain(a 5-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Sinn et al. (2008) | 2008 | Korea | D:20 C:27.5 M:62.5 |

Rome III | Secondary care | 40 | 6/14 | 8/12 | 44.7 ± 13 | L. acidophilus SDC 2012 and 2013 | 4×109 | 4 weeks | Any reduction in abdominal pain score | Response(Any reduction in abdominal pain score) Abdominal pain(a 6-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Zeng et al. (2008) | 2008 | China | D:100 | Rome II | Tertiary care | 29 | 10/4 | 9/6 | 45.2 ± 10.7 | Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium Longum | S.thermophilus (4×1010 c.f.u.), L. bulgaricus (4×109 c.f.u.), L. acidophilus (4×109 c.f.u.), and B. longum (4×109 c.f.u.) |

4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Bloating(100-mm VAS) Abdominal pain(100-mm VAS) Adverse events |

| Agrawal et al. (2009) | 2009 | UK | C:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 34 | 0/17 | 0/17 | 39.4 ± 10.6 | Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus |

B. lactis DN-173 010(2.5×1010 c.f.u.), S.thermophilus (2.4×109 c.f.u.), L. bulgaricus (2.4×109 c.f.u.), |

4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score Bloating(a 6-point numerical scale) Flatulence(a 6-point numerical scale) Abdominal pain(a 6-point numerical scale) |

| Enck et al. (2009) | 2009 | Germany | All types | Kruis score | Primary care | 298 | 76/72 | 75/75 | 49.6 ± 13.6 | E. coli DSM17252 | (1.5–4.5×107 c.f.u./ml) 0.75 ml drops t.i.d. for 1 week, then 1.5 ml t.i.d. for weeks 2–8 | 8 weeks | No longer having IBS symptoms | Response(no longer having IBS symptoms) General symptom score Adverse events |

| Hong et al. (2009) | 2009 | Korea | D:45.7 C:20 M:8.6 non-classified:25.7 |

Rome III | tertiary care | 70 | 25/11 | 22/12 | 37 ± 14.85 | Combination | 4×1010 | 8 weeks | Reduction of symptom score by at least 50% | Response(Reduction of symptom score by at least 50%) Adverse events |

| Williams et al. (2009) | 2009 | UK | D:11.5C:27 A:61.5 |

Rome II | Advertising | 52 | 3/25 | 4/20 | 39 ± 11.5 | Combination | 2.5×1010 | 8 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptom score |

| Simrén et al. (2010) | 2010 | Sweden | D:35 C:15 M:50 |

Rome II | Tertiary care | 74 | 11/26 | 11/26 | 43 ± 15.43 | Combination | 2×1010 | 8 weeks | Adequate relief of their IBS symptoms at least 50% of the weeks | Response(Adequate relief of their IBS symptoms) Global symptom score Abdominal pain(100-mm VAS) Bloating(100-mm VAS) Adverse events |

| Choi et al. (2011) | 2011 | Korea | D:71.6 M:28.4 |

Rome II | Tertiary care | 90 | 18/17 | 19/20 | 40.4 ± 12.9 | Saccharomyces boulardii | 4×1011 | 4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score(7-point Likert scale) Bloating(7-point Likert scale) Abdominal pain(7-point Likert scale) Adverse events |

| Guglielmetti et al. (2011) | 2011 | Germany | D:21.3 C:19.7 M:58.2 non-classified:0.8 |

Rome III | Secondary care and advertising | 122 | 19/41 | 21/41 | 38.9 ± 12.75 | B. bifidum MIMBb75 | 1×109 | 4 weeks | Improvement in average weekly global IBS symptom score of 1 or more for 50% of weeks, and continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Response(Improvement in average weekly global IBS symptom score of 1 or more for 50% of weeks) Global symptoms score(7-point Likert score) Bloating(7-point Likert scale) Abdominal pain(7-point Likert scale) Adverse events |

| Michail and Kenche (2011) | 2011 | USA | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 24 | 5/10 | 3/6 | 21.8 ± 17 | Combination | 9×1011 | 8 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score(a clinical rating scale GSRS) Bloating(GSRS) Abdominal pain(GSRS) Adverse events |

| Sondergaard et al. (2011) | 2011 | Denmark and Sweden | all types | Rome II | Primary and secondary care | 52 | 7/20 | 6/19 | 51.3± 9.5 | Combination | 2.5×1010 | 8 weeks | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms and continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms Global symptoms score(IBS SSI Francis et al) Abdominal pain(100-mm VAS) |

| Cha et al. (2012) | 2012 | Korea | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 50 | 12/13 | 14/11 | 39.1 ± 11.76 | Combination | 1×1010 | 8 weeks | Adequate relief of their IBS symptoms at least 50% of the weeks and continuous scale for IBS symptoms |

Response(Adequate relief of their IBS symptoms at least 50% of the weeks) Global symptoms score(10-point VAS) Abdominal pain(10-point VAS) Bloating(10-point VAS) Adverse events |

| Cui et al. (2012) | 2012 | China | D:48.3 C:20 M:11.7 non-classified:10 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 60 | 11/26 | 7/16 | 44.66 ± 15.23 | Combination | 1.5×107 | 4 weeks | reduction of symptom score by at least 30% | Improvement in IBS symptoms |

| Dapoigny et al. (2012) | 2012 | France | D:30 C:22 M:34 U:14 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 50 | 5/20 | 10/15 | 47.05± 10.98 | Lactobacillus casei rhamnosus LCR35 | 6×108 | 4 weeks | IBS severity score reduced by at least 50% | Response (IBS severity score reduced by at least 50%) Adverse events |

| Ducrotte et al. (2012) | 2012 | India | all types | Rome III | Primary care | 214 | 70/38 | 81/25 | 37.28± 12.6 | L. plantarum LP299V DSM 9843 | 1×1011 | 4 weeks | Patients rated treatment efficacy as excellent or good | Global assessment of treatment efficacy Adverse events |

| Farup et al. (2012) | 2012 | Norway | D:37.5 C:6.25 A:56.25 |

Rome II | Secondary care | 28 | Not stated | Not stated | 50± 11 | L. plantarum MF 1298 | 1×1010 | 3 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score |

| Kruis et al. (2012) | 2012 | Germany | all types | Rome II | Tertiary care | 120 | 12/48 | 16/44 | 45.7± 12.4 | E. coli Nissle 1917 | 2.5–25×109 for 4 days then 5–50×109 for 12 weeks | 12 weeks | Patients reported contented with treatment | Response (Patients reported contented with treatment) Adverse events |

| Amirimani et al. (2013) | 2013 | Iran | all types | Rome III | Secondary care | 102 | 21/32 | 15/24 | 41.8± 12.5 | Lactobacillus reuteri | 1×1011 | 4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(questionare) Bloating(questionare) Adverse events |

| Begtrup et al. (2013) | 2013 | Denmark | D:40 C:19 M:38 U:2 |

Rome III | Primary care | 131 | 51/16 | 46/18 | 30.52± 9.42 | Combination | 5.2×1010 | 6 months | Adequate relief of global IBS symptoms for at least 50% of the time, and continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Response (Adequate relief of global IBS symptoms) Global symptoms score Abdominal pain(GSRS-IBS) Bloating(GSRS-IBS) Adverse events |

| Charbonneau et al. (2013) | 2013 | Ireland | all types | Rome II | Population based | 76 | 8/31 | 6/31 | 45.5± 11 | B. infantis 35624 | 1×109 | 8 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptom severity(a six-point scale) Abdominal pain((a six-point numerical scale) Bloating(a six-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Roberts et al. (2013) | 2013 | UK | C and M | ROME III | Primary care | 179 | 13/75 | 14/77 | 44.18± 12.36 | Bifidobacterium lactis CNCM I-2494 S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus |

2.5×1010

2.4×109 2.4×109 |

12 weeks | Subjective global assessment (SGA) of symptom relief | Subjective global assessment (SGA) of symptom relief IBS-SSS Abdominal pain(6 point Likert scale) Bloating(6 point Likert scale) |

| Abbas et al. (2014) | 2014 | Pakistan | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 72 | 27/10 | 26/9 | 35.4± 11.9 | Saccharomyces boulardii | 3×109 | 6 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(a 4-point scale) Bloating(a 4-point scale) Adverse events |

| Jafari et al. (2014) | 2014 | India | all types | Rome III | Secondary care | 108 | 21/33 | 22/32 | 36.7± 11.5 | Combination | 8×109 | 4 weeks | Satisfactory relief of global IBS symptoms for at least 50% of the time | Relief of IBS symptoms Abdominal pain(100-mm VAS) Bloating(100-mm VAS) |

| Lorenzo-Zuniga et al. (2014) | 2014 | Spain | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 84 | 16/39 | 15/14 | 46.8± 12.5 | Combination | high dose (1-3×1010) low dose (3-6×109) |

6 weeks | “Considerably relieved” or “completely relieved” of global IBS symptoms for at least 50% of the time | Health-related quality of life(a specifc questionnaire ranging from 1-100) Respond(relief of symptoms) Adverse events |

| Ludidi et al. (2014) | 2014 | Netherlands | all types | Rome III | Secondary care and advertising | 40 | 6/15 | 7/12 | 40.5± 14.4 | Combination | 5×109 | 6 weeks | A 30% or greater improvement in mean symptom composite score(MSS) | Respond(mean symptom composite score MSS) |

| Pedersen et al. (2014) | 2014 | Denmark | D:38 C:17.3 A:40.7 non-classified:4 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 81 | 14/27 | 11/29 | Not stated | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 1.2×1010 | 6 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | IBS-SSS |

| Shavakhi et al. (2014) | 2014 | Iran | D:32.6 C:45.7 A:21.7 |

Rome II | Tertiary care | 129 | 20/46 | 24/39 | 36.2± 9.2 | Combination | 2×108 | 2 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(a 4-point scale) Distension(a 4-point scale) |

| Sisson et al. (2014) | 2014 | UK | D:37.6 C:21.5 M:35.5 U:5.4 |

Rome III | Primary care and secondary care | 186 | 40/84 | 17/45 | 38.3± 10.6 | Combination | 2×108/kg | 12 weeks | Patients reported mild or no symptoms | Respond(IBS-SSS) IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Abdominal pain(IBS-SSS) Bloating(IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

| Stevenson et al. (2014) | 2014 | South Africa | D:37.6 C:21.5 |

Rome II | Secondary care | 81 | 2/52 | 0/27 | 47.9± 13 | Lactobacillus plantarum 299 v | 1×1010 | 8 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

| Yoon et al. (2014) | 2014 | Korea | D:53.1 C40.8 M:6.1 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 49 | 11/14 | 6/18 | 44.5± 14.3 | Combination | 1×1010 | 4 weeks | Global relief of IBS symptoms | Global relief of IBS symptoms Abdominal pain(a 10-point numerical scale) Bloating(a 10-point numerical scale) Adverse events |

| Faghihi et al. (2015) | 2015 | Iran | D:35.3 C39.6 M:25.1 |

Rome II | Secondary care | 139 | Not stated | Not stated | 38± 13.3 | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Not stated | 6 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Global symptoms score(Birmingham IBS Symptom Questionnaire) |

| Pineton de Chambrun et al. (2015) | 2015 | France | D:28.5 C46.9 M:24.6 |

Rome III | Not stated | 179 | 14/72 | 11/82 | 44± 13.3 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856 | 4×109 | 8 weeks | A reduction in the abdominal pain score of 1 arbitrary unit (au) for at least 50% of the time | Improvement in IBS symptoms Abdominal pain(7-point Likert scale) Adverse events |

| Yoon et al. (2015) | 2015 | Korea | D:48.1 C:18.5 M:21 U:12.4 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 80 | 24/17 | 19/20 | 59.3± 12.2 | Combination | 1×1010 | 4 weeks | Adequate relief of global IBS symptoms | Adequate relief of global IBS symptoms Global symptoms score(10-point VAS) Abdominal pain(10-point VAS) Bloating(10-point VAS) |

| Lyra et al. (2016) | 2016 | Finland | D:38.9 C:16.6 M:44 U:0.5 |

Rome III | Primary care | 391 | 62/198 | 37/94 | 47.9± 12.9 | L.acidophilus NCFM (ATCC 700396) | low-dose: 1×109

high-dose: 1×1010 |

12 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Abdominal pain(IBS-SSS) Bloating(IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

| Majeed et al. (2016) | 2016 | India | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 36 | 7/11 | 10/8 | 35.8± 10.8 | Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 | 2×109 | 90 days | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(Questionnaire) Bloating(Questionnaire) Adverse events |

| Mezzasalma et al. (2016) | 2016 | Italy | C:100 | Rome III | Not stated | 150 | Not stated | Not stated | 37.4± 12.5 | 1: L.acidophilus, L. reuteri 2: L.plantarum, L. rhamnosus, B. animalis subsp. Lactis |

1: 1×1010

2: 1.5×1010 |

60 days | A decrease of abdominal pain of at least 30% compared to the basal condition for at least 50% of the intervention time | Response(the subject reporting a decrease of symptoms of at least 30% compared to the basal condition for at least 50% of the intervention time) |

| Spiller et al. (2016) | 2016 | France | D:20.8 C47.5 M:31.7 |

Rome III | Primary care and secondary care | 379 | 31/161 | 31/156 | 45.3± 14.9 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae I-3856 | 8×109 | 12 weeks | An improvement of 50% of the weekly average''intestinal pain/discomfort score'' compared with baseline average score for at least 4 out of the last 8 weeks of the study | Response Global symptoms score Abdominal pain(8-point Likert scale) Bloating(8-point Likert scale) Adverse events |

| Thijssen et al. (2016) | 2016 | Netherlands | D:30 C:25 A:28.75 U:16.25 |

Rome II | Secondary care,tertiary care, and advertising | 80 | 13/26 | 12/29 | 41.8± 14.1 | Lactobacillus casei Shirota | 1.3×1010 | 8 weeks | An mean symptom score(MSS) decrease of at least 30% | Response (An mean symptom score(MSS) decrease of at least 30%) |

| Hod et al. (2017) | 2017 | Israel | D:100 | Rome III | Community and secondary and tertiary care | 107 | 0/54 | 0/53 | Not extractable | Combination | 5×1010 | 8 weeks | improvement in symptoms for at least 50% of the tme |

Response Adverse events |

| Ishaque et al. (2018) | 2018 | Bangladesh | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 360 | 136/45 | 145/34 | 31.9 ± 9.9 | Combination | 8×109 | 16weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Abdominal pain(IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

| Khodadoostan et al. (2018) | 2018 | Iran | D:100 | Rome III | Secondary care and tertiary care | 67 | 21/12 | 22/12 | 34.1 ± 11.0 | Combination | 2×109 | 6 months | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(10-point VAS) |

| Kim et al. (2018) | 2018 | Korea | not stated | not stated | Advertising | 42 | 19/11 | 6/6 | 32.7 ± 6.6 | Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 | low-dose: 1×109

high-dose: 1×1010 |

4 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | Abdominal pain(5-point Likert scale) Bloating(5-point Likert scale) |

| Preston et al. (2018) | 2018 | USA | D:46.4 C:35.7 M:18.6 |

Rome III | Tertiary care | 113 | 47/29 | 21/16 | 40.4 ± 13.5 | Combination | 1×1011 | 6 weeks | Continuous scale for IBS symptoms | IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Abdominal pain(IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

| Sun et al. (2018) | 2018 | China | D:100 | Rome III | Tertiary care | 200 | 63/42 | 53/42 | 43.9 ± 12.7 | Clostridium butyricum | 5.67×107 | 4 weeks | A reduction of ≥50 points of total IBS-SSS score | Response (A reduction of ≥50 points of total IBS-SSS score) IBS symptom severity scores (IBS-SSS) Abdominal pain(IBS-SSS) Bloating(IBS-SSS) Adverse events |

Figure 2.

Risk of bias.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary.

Efficacy of Probiotics on IBS Symptoms Improvement or Response

Thirty-five RCTs (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2016; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018) with 4,392 patients reported overall IBS symptoms improvement or response as a dichotomous outcome. There were two (Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Mezzasalma et al., 2016) of these RCTs examining two different dose groups and one (Whorwell et al., 2006) examining three different dose groups. One (Gade and Thorn, 1989) RCT did not mention the dose of probiotics, so it was not included in the subgroup analysis of probiotics dose. Overall, 1,171(49.5%) of 2,367 patients in the group of probiotics declared symptoms improvement or response after therapy, compared with 644 (31.8%) of 2,025 in the placebo group. The RR of IBS symptoms improvement or response was 1.52(95% CI 1.32–1.76), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 71%, P < 0.001; Figure 4 ). The funnel plot suggested the existence of asymmetry (Egger test, P = 0.094; Figure S1 ), indicating possible publication bias. While 19 RCTs (Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017) with low bias risk were assessed, the effect was still significant (RR = 1.59; 95% CI 1.25–2.04).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of efficacy on IBS symptoms improvement or respond: subgroup of probiotics duration.

In the subgroup of duration, 18 studies (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Jafari et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2018) evaluated a shorter duration (< 8 weeks) and 17 studies (Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Enck et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017) used a longer duration (≥ 8 weeks). The RR of group with less than 8 weeks was 1.55 (95% CI 1.27–1.89; Figure 4 ), and the RR of group with more than 8 weeks was 1.52 (95% CI 1.23–1.88), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 74%, P < 0.01; I2 = 69%, P < 0.01, respectively). In the subgroup of probiotics dose, high doses (daily dose of probiotics ≥ 1010) were assessed in 21 trials (Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017). A significant effect on symptoms (RR = 1.51; 95% CI 1.20–1.91; Figure S2 ) and statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 77%, P < 0.01) were suggested. Low doses (daily dose of probiotics < 1010) were evaluated in 15 trials (Nobaek et al., 2000; Kajander et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Enck et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Cui and Hu, 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Jafari et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018). A significant effect on symptoms (RR = 1.56; 95% CI 1.33–1.83) and significant heterogeneity were also detected (I2 = 54%, P < 0.01). In the subgroup of probiotics type, there were 15 studies using single probiotics (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Nobaek et al., 2000; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Whorwell et al., 2006; Sinn et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Thijssen et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018) and 21 studies using combination probiotics (Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Cui and Hu, 2012; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Ludidi et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Mezzasalma et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017). The RR of single and combination group was 1.76 (95% CI 1.37–2.25; Figure S3 ) and 1.39 (95% CI 1.18–1.65), respectively. The I2 of the single probiotics subgroup was 69% (P < 0.01), and combination probiotics subgroup was 60% (P < 0.01), suggesting statistically significant heterogeneity. In the subgroup of geographic position, we assigned 2 trials (Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005) in USA to the North America group; five comparisons of three separate papers (Whorwell et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014) in UK, five trials (Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2016) in France, and two trials (Ludidi et al., 2014; Thijssen et al., 2016) in Netherlands to the Western Europe group; two comparisons of one papers (Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014) in Spain and two comparisons of one papers (Mezzasalma et al., 2016) in Italy to the South Europe group; two trials (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Begtrup et al., 2013) in Denmark, two trials (Nobaek et al., 2000; Simrén et al., 2010) in Sweden, one trials (Sondergaard et al., 2011) in Denmark and Sweden, and one trials (Kajander et al., 2005) in Finland to the Northern Europe group; one trials (Niedzielin et al., 2001) in Poland and four trials (Enck et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Kruis et al., 2012) in Germany to the Central Europe group; five trials (Sinn et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Cha et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015) in Korea and two trials (Cui and Hu, 2012; Sun et al., 2018) in China to the East Asian group; one trials (Hod et al., 2017) in Israel to the West Asian group; and two trials (Ducrotte et al., 2012; Jafari et al., 2014) in India to the South Asian group. There was a statistically significant benefit in favor of probiotics in North America group (RR = 1.19; 95% CI 0.66–2.15; Figure 5 ), with no significant heterogeneity noted between the studies(I2 = 0%, P = 0.48), West Europe group(RR = 1.15; 95% CI 1.01–1.30; I2 = 25%, P = 0.20), Northern Europe group(RR = 1.45; 95% CI 1.10–1.91; I2 = 33%, P = 0.19) and East Asian group(RR = 1.55; 95% CI 1.21–1.98; I2 = 39%, P = 0.13).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of efficacy of probiotics on IBS symptoms improvement or respond: subgroup of geographic position.

Efficacy of Probiotics on Global IBS Symptoms Scores

There were 29 separate trials (Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Niv et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Kajander et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Farup et al., 2012; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Faghihi et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Ishaque et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018) including 35 comparisons with 3,726 patients reporting the efficacy of probiotics on global IBS symptoms scores. One (Spiller et al., 2016) of these RCTs examining two different dose groups and one (Whorwell et al., 2006) examining three different dose groups. There was a trial (Faghihi et al., 2015) did not mention the dose of probiotics, so it was not included in the subgroup analysis of probiotics dose. Two types of probiotics were used in one trial (O'Mahony et al., 2005), and three subtypes of IBS, including IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and IBS with mixed patterns of constipation and diarrhea (IBS-M), were detected separately in one RCT (Spiller et al., 2016). Probiotics had a statistically significant effect on improving the global IBS symptoms vs. placebo (SMD = -1.8; 95% CI -0.30 to -0.06; Figure 6 ). Heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 65%, P < 0.001). There was no significant asymmetry in funnel plot (Egger test, P = 0.689; Figure S4 ), indicating no proof of publication bias.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of efficacy on global IBS symptoms scores: subgroup of probiotics duration.

In the subgroup of duration, 11 comparisons (Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Farup et al., 2012; Pedersen et al., 2014; Faghihi et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2018) evaluated a shorter treatment duration (< 8 weeks). There was a beneficial effect on global IBS symptoms scores with probiotics (SMD -0.09; 95% CI -0.20 to 0.02) and low heterogeneity was found (I2 = 10%, P = 0.12). In the subgroup of probiotics dose, no significant differences were found, as shown in Figure S5 . In the subgroup of probiotics type, 14 comparisons (Niv et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Simren and Lindh, 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Farup et al., 2012; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Faghihi et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018) using single probiotics were found a beneficial efficacy on global IBS symptoms scores (SMD -0.06; 95% CI -0.16 to 0.14; Figure 7 ), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 33%, P = 0.12). In the subgroup of geographic position, we assigned 2 trials (Kim et al., 2003; Michail and Kenche, 2011) in USA to the North America group; seven comparisons of five separate papers (Whorwell et al., 2006; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014) in UK, three comparisons of 1 papers (Spiller et al., 2016) in France, and three comparisons of two separate papers (O'Mahony et al., 2005; Charbonneau et al., 2013) in Ireland to the Western Europe group; two trials (Begtrup et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2014) in Denmark, two trials (Simren and Lindh, 2006; Simrén et al., 2010) in Sweden, one trials (Sondergaard et al., 2011) in Denmark and Sweden, four comparisons of three papers (Kajander et al., 2005; Kajander et al., 2008; Lyra et al., 2016) in Finland, and one trials (Farup et al., 2012) in Norway to the Northern Europe group; one trials (Guglielmetti et al., 2011) in Germany to the Central Europe group; three trials (Choi et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2015) in Korea and two trials (Zeng et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2018) in China to the East Asian group; one trials (Niv et al., 2005) in Israel and one trials (Faghihi et al., 2015) in Iran to the West Asian group; and one trials (Ishaque et al., 2018) in Bangladesh to the South Asian group; and one trials (Stevenson et al., 2014) in South Africa to the South Africa group. There was a statistically significant benefit in favor of probiotics in North America group (SMD -0.25; 95% CI -0.82 to 0.32; Figure 8 ), with no significant heterogeneity noted between the studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.68), East Asian group (SMD -0.24; 95% CI -0.43 to -0.05; I2 = 0%, P = 0.81), and South Asian group (SMD 0.06; 95% CI -0.24 to 0.36; I2 = 0%, P = 0.45).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of efficacy on global IBS symptoms scores: subgroup of probiotics type.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of efficacy of probiotics on global IBS symptoms scores: subgroup of geographic position.

Efficacy of Probiotics on Individual Symptom Scores

There were 38 trials (Nobaek et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Kajander et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Jafari et al., 2014; Shavakhi et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2016; Lyra et al., 2016; Majeed et al., 2016; Ishaque et al., 2018; Khodadoostan et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018) including 44 comparisons with 4,579 patients reporting efficacy of probiotics on abdominal pain. Probiotics had effect on improving abdominal pain (SMD -0.22; 95% CI -0.33 to -0.11; Figure S6 ), but significant heterogeneity existed (I2 = 70%, P < 0.001). However, in subgroup analysis of probiotics dose, 24 comparisons (Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Sondergaard et al., 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018) using high dose were found a significant benefit over placebo (SMD = -0.14; 95% CI -0.26 to -0.01; Figure S7 ), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 39%, P = 0.03). There was no significant asymmetry in funnel plot (Egger test, P = 0.235; Figure S8 ), indicating no proof of publication bias.

Twenty-nine trials (Nobaek et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Abbas et al., 2014; Jafari et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Majeed et al., 2016; Lyra et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018) reported continuous data for the effect of probiotics on bloating scores in 3,496 patients. Probiotics had effect on improving bloating (SMD -0.13; 95% CI -0.24 to -0.03; Figure S9 ) and heterogeneity was found (I2 = 54%, P < 0.01). In the subgroup of probiotics duration, 19 comparisons (Nobaek et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Amirimani et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Jafari et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018) using a short treatment duration (<8 weeks) were found a significant benefit over placebo (SMD -0.13; 95% CI -0.27 to -0.01). Low heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 47%, P = 0.01).There was a beneficial effect on bloating in 22 comparisons (Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2008; Agrawal et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013; Sisson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018) using high dose (SMD -0.07; 95% CI -0.20 to -0.06; Figure S10 ).Low heterogeneity among trials was discovered (I2 = 38%, P = 0.04).The funnel plot suggested the existence of asymmetry (Egger test, P = 0.095; Figure S11 ), indicating possible publication bias.

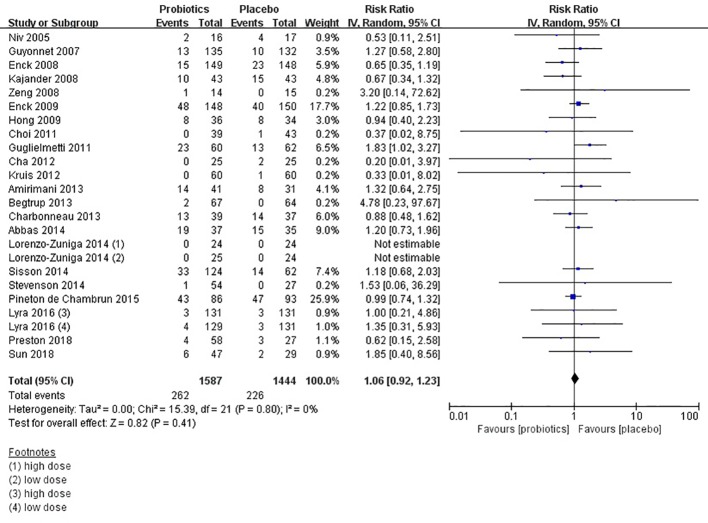

Safety of Probiotics in IBS

Forty studies (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Niv et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Enck et al., 2008; Kajander et al., 2008; Sinn et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2008; Enck et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2009; Simrén et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Guglielmetti et al., 2011; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Cha et al., 2012; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Ducrotte et al., 2012; Kruis et al., 2012; Amirimani et al., 2013; Begtrup et al., 2013; Charbonneau et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Sisson et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Pineton de Chambrun et al., 2015; Lyra et al., 2016; Majeed et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Hod et al., 2017; Ishaque et al., 2018; Preston et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018) provided safety-related data, which was assessed by adverse events. Fourteen trials (Gade and Thorn, 1989; Niedzielin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003; Kajander et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Sinn et al., 2008; Simrén et al., 2010; Michail and Kenche, 2011; Dapoigny et al., 2012; Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Hod et al., 2017; Ishaque et al., 2018) reported that there were no adverse events. Four trials (O'Mahony et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Majeed et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016) reported adverse events of both arms. Difference was detected between probiotics and placebo (RR = 1.07; 95% CI 0.92–1.24; Figure 9 ), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0, P = 0.83). The funnel plot suggested no evidence of asymmetry (Egger test, P = 0.808; Figure S12 ). Probiotics seem to be safer than placebo in IBS patients.

Figure 9.

Forest plot of safety of probiotics in IBS.

Discussion

Alterations of the intestinal microbiome could be relevant to IBS. Symptoms in IBS often developed after an infection, which was known as post-infectious IBS (Marshall et al., 2006; Marshall et al., 2007). Gut bacterial overgrowth may cause symptoms of IBS indistinguishable (Lin, 2004). Studies suggest that compared with the healthy group the colonic microbiome changes in IBS (Durban et al., 2013; Jalanka-Tuovinen et al., 2014). Despite there were many drugs and treatments for IBS, probiotics have shown beneficial (Simrén et al., 2013; Mozaffari et al., 2014). Probiotics may regulate immunity in IBS to protect the intestine (Major and Spiller, 2014). Probiotics also modify the gut microbiota, which improves some IBS symptoms, such as flatulence, bloating, and altered bowel habits (Jeffery et al., 2012; Tap et al., 2017).

Summary of Main Results

Many pieces of evidence have suggested that probiotics may benefit IBS symptoms (Shavakhi et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014). However, the results of clinical trials have been conflicting. Our meta-analysis has indicated that probiotics may be beneficial and safe to improve symptoms of IBS compared with placebo. However, it was difficult to draw a precise conclusion as a result of the existence of significant heterogeneity and possible publication bias. We found that a shorter treatment duration (< 8 weeks) could reduce global IBS symptoms scores and bloating scores (Whorwell et al., 2006; Guyonnet et al., 2007; Drouault-Holowacz et al., 2008). As a chronic and recurrent disease (Sun et al., 2018), the improvement of IBS symptoms seems to be detected after a long time by taking probiotics continuously. However, according to current research shorter treatment duration seemed to be more beneficial. But due to many dropouts in the longer duration group, there may have an impact on research results, manifesting as greater improvement in the shorter duration group (Roberts et al., 2013). Although the use of single probiotics tended to have a beneficial effect on improving the bloating scores (Majeed et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), it was unknown which strain or species was more beneficial than others. Using a high dose of probiotics may reduce abdominal pain scores and bloating scores (Yoon et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018). However, Lyra et al. tested two different doses (1010 CFU/D, and 109 CFU/D) of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and reported that none of the outcomes showed a dose-response effect (Lyra et al., 2016). Small differences of dosage may contribute to no effect of dose. Probiotics could benefit overall IBS symptoms improvement in North America, West Europe, Northern Europe, and East Asian.We also found that probiotics could reduce global IBS symptoms scores in North America, East Asian, and South Asian. More pieces of evidence are needed. Probiotics seemed safe for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (O'Mahony et al., 2005; Whorwell et al., 2006; Majeed et al., 2016; Spiller et al., 2016), but more long-term trials are required to prove it.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Our meta-analysis is the first to assemble the efficacy and safety of probiotics for IBS patients with all diagnostic criteria by subgroup analyses of probiotic type, dose, treatment duration, and geographic position. We conducted this meta-analysis and systematic review using a rigorous and reproducible methodology. Two reviewers assessed eligibility and extracted data independently. The random-effects model was used to minimize the possibility of overestimating treatment results. We also tried to contact researchers of possibly eligible trials to get data. These comprehensive approaches included more than 3,300 IBS patients receiving probiotics treatment. Finally, subgroup analyses of probiotics type, dose, treatment duration, and geographic position were performed to evaluate the efficacy of treatment.

Our study has certain limitations. Bias risk of many studies was unknown, and the analysis shows considerable evidence of heterogeneity between trials. However, considering only studies with low bias risk, the positive effects remained. The number of studies on subgroup analyses of probiotics type, doses, and treatment duration was limited. It was not enough to detect significant differences in the efficacy of probiotics. In some studies, significant placebo effects have been found which can affect the results.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis has demonstrated moderate evidence for the use and safety of probiotics in IBS. A shorter treatment duration (< 8 weeks) and a single probiotic may be more beneficial. Probiotics seem to be safe for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. There is still a need for more clinical trials. Finally, probiotics may be a beneficial therapy for IBS patients.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Author Contributions

LZ and BL conceived and designed this study. BL and LL searched and selected studies. HD and JG extracted essential information. BL and HS assessed the risk of bias. BL and HD performed statistical analyses. BL and HS interpreted the pooled results. BL, LL, and LZ drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Youth Foundation of 960th Hospital of the PLA with a unique identifier of 2017QN03.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to all authors listed in these all primary studies which were included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.00332/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abbas Z., Yakoob J., Jafri W., Ahmad Z., ND Islam M. (2014). Cytokine and clinical response to Saccharomyces boulardii therapy in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 630–639. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A., Houghton L. A., Morris J., Reilly B., Guyonnet D., Goupil F. N., et al. (2009). Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 29, 104–114. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirimani B., Nikfam S., Albaji M., Vahedi S., Vahedi H. (2013). Probiotic vs. Placebo in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 5, 98–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen V., Montori V. M., Keller J., West C. P., Layer P., Camilleri M. (2008). Effects of 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) Type 3 Antagonists on Symptom Relief and Constipation in Nonconstipated Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 545–555. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begtrup L. M., de Muckadell O. B., Kjeldsen J., Christensen R. D., Jarbol D. E. (2013). Long-term treatment with probiotics in primary care patients with irritable bowel syndrome-a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 48, 1127–1135. 10.3109/00365521.2013.825314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundeff A. W., Woodis C. B. (2014). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann. Pharmacother. 48, 777–784. 10.1177/1060028014528151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha B. K., Jung S. M., Choi C. H., Song In-do., Lee H. W., Kim H. J., et al. (2012). The effect of a multispecies probiotic mixture on the symptoms and fecal microbiota in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 46, 220–227. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823712b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Chey W. D., Drossman D., Losch-Beridon T., Wang M., Lichtlen P., et al. (2016). Effects of baseline abdominal pain and bloating on response to lubiprostone in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 1114–1122. 10.1111/apt.13807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau D., Gibb R. D., Quigley E. M. M. (2013). Fecal excretion of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 and changes in fecal microbiota after eight weeks of oral supplementation with encapsulated probiotic. Gut. Microbes 4, 201–211. 10.4161/gmic.24196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chey W. D., Lembo A., Macdougall J. E., Lavins B. J., Schneier H., Johnston J. M. (2011). Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Linaclotide Administered Orally for 26 Weeks in Patients With IBS-C: Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Gastroenterology 140, S–135. 10.1016/S0016-5085(11)60550-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Jo S. Y., Park H. J., Chang S. K., Myung S. J. (2011). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of saccharomyces boulardii in irritable bowel syndrome: effect on quality of life. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 45, 679–683. 10.1097/mcg.0b013e318204593e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S., Hu Y., Lunaud B., Cardot J. M., A (2012). Multistrain probiotic preparation significantly reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 5, 238–244. 10.1155/2012/952452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapoigny M., Piche T., Ducrotte P., Lunaud B., Cardot J. M., Bern A. (2012). Efficacy and safety profile of LCR35 complete freeze-dried culture in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind study. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 2067–2075. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersimonian R., Laird N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 7, 177–178. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman D. A., Camilleri M., Mayer E. A., Whitehead W.E. (2002). AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 123, 2108–2131. 10.1053/gast.2002.37095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouault-Holowacz S., Bieuvelet S., Burckel A., Cazaubiel M., Dray X., Marteau P. (2008). A double blind randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination in 100 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroen. Clin. Biol. 32, 147–152. 10.1016/j.gcb.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducrotte P., Sawant P., Jayanthi V. (2012). Clinical trial: Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 4012–4018. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i30.4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont H. L. (2014). Review article: evidence for the role of gut microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome and its potential influence on therapeutic targets. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 39, 1033–1042. 10.1111/apt.12728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durban A., Abellan J. J., Jimenez-Hernandez N., Artacho A., Garrigues V., Ortiz V., et al. (2013). Instability of the faecal microbiota in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86, 581–589. 10.1111/1574-6941.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey S. G., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck P., Zimmermann K., Menke G., Muller-lissner S., Martens U., Klosterhalfen S. (2008). A mixture of Escherichia coli (DSM 17252) and Enterococcus faecalis (DSM 16440) for treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome - a randomized controlled trial with primary care physicians. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 20, 1103–1109. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck P., Zimmermann K., Menke G., Klosterhalfen S. (2009). Randomized controlled treatment trial of irritable bowel syndrome with a probiotic E.-coli preparation (DSM17252) compared to placebo. Z Gastroenterol. 47, 209–214. 10.1055/s-2008-1027702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi A. H., Agah S., Masoudi M., Ghafoori S. M., Eshraghi A. (2015). Efficacy of Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a Double Blind Placebo-controlled Randomized Trial. Acta Med. Indones 47, 201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farup P. G., Jacobsen M., Ligaarden S. C., Rudi K. (2012). Probiotics, symptoms, and gut microbiota: what are the relations? A randomized controlled trial in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2012, 214102. 10.1155/2012/214102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade J., Thorn P. (1989). Paraghurt for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A controlled clinical investigation from general practice. Scand. J. Prim Health Care 7, 23–26. 10.3109/02813438909103666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnek I. M., Hays R. D., Kilbourne A., Naliboff B., Mayer E. A. (2000). The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 119, 654–660. 10.1053/gast.2000.16484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarner F., Khan A. G., Garich J., Eliakim R., Gangl A., Thompson A., et al. (2012). World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol. 46 (6), 468–481. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182549092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmetti S., Mora D., Gschwender M., Popp K. (2011). Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life–a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 33, 1123–1132. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyonnet D., Chassany O., Ducrotte P., Picard C., Mouret M., Mercier C. -H., et al. (2007). Effect of a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 26, 475–486. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes P. A., Fraher M. H., Quigley E. M. (2014). Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of food in pathogenesis and management. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 164–174. 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00392.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. T., Green S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. in The Cochrane Collaboration. Available online at: http://handbook.cochrane.org.

- Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hod K., Sperber A. D., Ron Y., Boaz M., Dickman R., Berliner S., et al. (2017). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the effect of a probiotic mixture on symptoms and inflammatory markers in women with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 29, e13037. 10.1111/nmo.13037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K. S., Kang H. W., Im J. P., Ji G. E., Kim S. G., Jung H. C., et al. (2009). Effect of probiotics on symptoms in korean adults with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. Liver 3, 101–107. 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.2.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland N. P., Quigley E. M., Brint E. (2014). Microbiota-host interactions in irritable bowel syndrome: epithelial barrier, immune regulation and brain-gut interactions. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 8859–8866. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishaque S. M., Khosruzzaman S. M., Ahmed D. S., Sah M. P. (2018). A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of a multi-strain probiotic formulation (Bio-Kult®) in the management of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 71. 10.1186/s12876-018-0788-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari E., Vahedi H., Merat S., Riahi A. (2014). Therapeutic effects, tolerability and safety of a multi-strain probiotic in Iranian adults with irritable bowel syndrome and bloating. Arch. Iran Med. 17, 466–470. 0141707/AIM.003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalanka-Tuovinen J., Salojarvi J., Salonen A., Immonen O., Garsed A., Kelly F. M., et al. (2014). Faecal microbiota composition and host-microbe cross-talk following gastroenteritis and in postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 63, 1737–1745. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery I. B., O'Toole P. W., Ohman L., Claesson M. J., Deane J., Quigley EMM, et al. (2012). An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut 61, 997–1006. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander K., Hatakka K., Poussa T., Färkkilä M. A. (2005). A probiotic mixture alleviates symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a controlled 6-month intervention. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 22, 387–394. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander K., Myllyluoma E., Rajilic-Stojanovic M., Kyrönpalo S., Rasmussen M., Järvenpää S., et al. (2008). Clinical trial: multispecies probiotic supplementation alleviates the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and stabilizes intestinal microbiota. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27, 48–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodadoostan M., Shavakhi A., Sherafat Z., Shavakhi A. (2018). Effect of Probiotic Administration Immediately and 1 Month after Colonoscopy in Diarrhea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients. Adv. BioMed. Res. 7, 94. 10.4103/abr.abr_216_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Camilleri M., McKinzie S., Lempke M. B., Burton D. D., Thomforde G. M., et al. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic, VSL#3, on gut transit and symptoms in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 17, 895–904. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Vazquez Roque M. I., Camilleri M., Stephens D., Burton D. D., Baxter K., et al. (2005). A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination VSL# 3 and placebo in irritable bowel syndrome with bloating. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 17, 687–696. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. G., Moon J. T., Lee K. M., Chon N. R., Park H. (2006). The effects of probiotics on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 47, 413–419. 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.6.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y., Park Y. J., Lee H. J., Park M. Y., Kwon O. (2018). Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 27, 853–857. 10.1007/s10068-017-0296-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruis W., Chrubasik S., Boehm S., Stange C., Schulze J. (2012). A double-blind placebo-controlled trial to study therapeutic effects of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in subgroups of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 27, 467–474. 10.1007/s00384-011-1363-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. C. (2004). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA 292, 852–858. 10.1001/jama.292.7.852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Zuniga V., Llop E., Suarez C., Alvarez B., Abreu L., Espadaler J., et al. (2014). I.31, a new combination of probiotics, improves irritable bowel syndrome-related quality of life. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 8709–8716. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell R. M., Ford A. C. (2012). Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 712–721.e4. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludidi S., Jonkers D. M., Koning C. J., Kruimel J. W., Mulder L., Vaart I. B., et al. (2014). Randomized clinical trial on the effect of a multispecies probiotic on visceroperception in hypersensitive IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 26, 705–714. 10.1111/nmo.12320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra A., Hillilä M., Huttunen T., Männikkö S., Taalikka M., Tennilä J., et al. (2016). Irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity improves equally with probiotic and placebo. World J. Gastroenterol. 22, 10631–10642. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed M., Nagabhushanam K., Natarajan S., Arumugam S., Ali F., Pande F., et al. (2016). Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 supplementation in the management of diarrhea predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a double blind randomized placebo controlled pilot clinical study. Nutr. J. 15, 21. 10.1186/s12937-016-0140-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major G., Spiller R. (2014). Irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and the microbiome. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21, 15–21. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. K., Thabane M., Garg A. X., Clark W.F., Salvadori M., Collins S. M. (2006). Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology 131, 445–450. 10.1016/S0399-8320(07)89359-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. K., Thabane M., Borgaonkar M. R., James C. (2007). Postinfectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome After a Food-Borne Outbreak of Acute Gastroenteritis Attributed to a Viral Pathogen. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 457–460. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzasalma V., Manfrini E., Ferri E., Sandionigi A., Ferla B. L., Schiano I., et al. (2016). A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial: The Efficacy of Multispecies Probiotic Supplementation in Alleviating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Associated with Constipation. BioMed. Res. Int. 2016, 1–10. 10.1155/2016/4740907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michail S., Kenche H. (2011). Gut Microbiota is Not Modified by Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of VSL#3 in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Probiotics Antimicrob. 3, 1–7. 10.1007/s12602-010-9059-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari S., Nikfar S., Abdollahi M. (2014). The safety of novel drugs used to treat irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 13, 625–638. 10.1517/14740338.2014.902932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzielin K., Kordecki H., Birkenfeld B. (2001). A controlled, double-blind, randomized study on the efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 1143–1147. 10.1097/00042737-200110000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv E., Naftali T., Hallak R., Vaisman N. (2005). The efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome-a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Clin. Nutr. 24, 925–931. 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobaek S., Johansson M. L., Molin G., Ahrné S., Jeppsson B. (2000). Alteration of intestinal microflora is associated with reduction in abdominal bloating and pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95, 1231–1238. 10.1016/S0002-9270(00)00807-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony L., McCarthy J., Kelly P., Hurley G., Luo F., Chen K., et al. (2005). Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 128, 541–551. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes G. C., Brostoff J., Whelan K., Sanderson J. D. (2008). Gastrointestinal Microbiota in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Their Role in Its Pathogenesis and Treatment. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 1557–1567. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N., Andersen N. N., Végh Z., Jensen L., Ankersen D. V., Felding M., et al. (2014). Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 16215–16226. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineton de Chambrun G., Neut C., Chau A., Cazaubiel M., Pelerin F., Justen P., et al. (2015). A randomized clinical trial of Saccharomyces cerevisiae versus placebo in the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Liver Dis. 47, 119–124. 10.1016/j.dld.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston K., Krumian R., Hattner J., de Montigny D., Stewart M., Gaddam S. (2018). Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285, Lactobacillus casei LBC80R and Lactobacillus rhamnosus CLR2 improve quality-of-life and IBS symptoms: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Benef. Microbes 9, 697–706. 10.3920/BM2017.0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi R., Nikfar S., Rezaie A., Abdollahi M. (2009). Efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 1548–1553. 10.3748/wjg.15.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L. M., McCahon D., Holder R., Wilson S., Hobbs F. D. (2013). A randomised controlled trial of a probiotic ‘functional food' in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 13, 45. 10.1186/1471-230X-13-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavakhi A., Minakari M., Farzamnia S., Peykar M. S., Taghipour G., Tayebi A., et al. (2014). The effects of multi-strain probiotic compound on symptoms and quality-of-life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Adv. BioMed. Res. 3, 140. 10.4103/2277-9175.135157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. P., Choi Y. M., Kim W. H., Hong S. P., Park J. M., Kim J., et al. (2018). A double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial that breast milk derived-Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 mitigated diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 62, 179–186. 10.3164/jcbn.17-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]