Abstract

A range of binary, ternary (CFS), and quaternary (CZTS) metal sulfide materials have been successfully deposited onto the glass substrates by air-spray deposition of metal diethyldithiocarbamate molecular precursors followed by pyrolysis (18 examples). The as-deposited materials were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (p-XRD), Raman spectroscopy, secondary electron microscopy (SEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy, which in all cases showed that the materials were polycrystalline with the expected elemental stoichiometry. In the case of the higher sulfides, EDX spectroscopy mapping demonstrated the spatial homogeneity of the elemental distributions at the microscale. By using this simple and inexpensive method, we could potentially fabricate thin films of any given main group or transition metal chalcogenide material over large areas, theoretically on substrates with complex topologies.

Keywords: metal chalcogenide, CZTS, metal sulfide, molecular precursors, spray pyrolysis, thin film solar cells

Introduction

Metal chalcogenides constitute an important family of medium to narrow band gap semiconductors. Much attention has been given to the synthesis of binary metal chalcogenides, such as FeS, CdS, CoS, ZnS, SnS, PbS, NiS, MnS, Ag2S, Cu2S, In3S2, Bi2S3, Ga2S3, Sb2S3, WS2, and MoS2 for applications in optoelectronics,1−3 photovoltaics,4−8 piezoelectronics,9 thermoelectronics,10−12 and, for the layered metal chalcogenides, as solid lubricants in mechanical systems.13−15 Furthermore, many ternary and quaternary metal sulfides, for example, copper iron sulfide (CuFeS2, CFS) and copper zinc tin sulfide (CZTS, Cu2ZnSnS4), are used as absorber layers in thin film photovoltaic devices because of their photoelectric characteristics, which are suitable for potentially inexpensive and sustainable solar energy generation.16−18 Various methods have been used for the deposition of metal chalcogenide thin films, such as chemical vapor deposition, electrodeposition, anodization, successive ionic adsorption and reaction (SILAR), electroconversion, chemical bath deposition, and solution–gas interface techniques.19−26 Among those techniques, spray deposition is potentially a very simple and cost-effective technique for the deposition of metal sulfide films for large and complex surfaces.

Spray annealing is used to deposit ceramic coatings, including thick and thin films of metal oxides. In this method, a solution is sprayed onto the preheated substrate to obtain homogeneous microcrystalline semiconducting and photoconductive films. This deposition method can also be used for the fabrication of multilayer films. Spray pyrolysis has been used for a number of decades in the glass industry to produce coatings, for example, during the Pilkington process and for the production of solar cells.27,28 There has also been some research into the deposition of higher metal sulfides, that is, ternary and quaternary systems by spray coating. Sayed et al. deposited Cu2SnS3 (CTS) film onto the molybdenum coated soda lime glass substrates using a chemical spray pyrolysis method. The films were deposited by using an aqueous solution of copper nitrate, tin methanesulfonate, and thiourea and was further annealed at 550 °C for 30 min in the presence of elemental sulfur and SnS. The effect of the annealing on the films deposited by spray annealing method was also studied.29 Chen et al. also studied the deposition of ternary Cu2SnS3 (CTS) by spray pyrolysis and by rapid thermal annealing method.30 Moumen et al. deposited CuO thin films using the spray pyrolysis technique at several temperatures. The effect of substrate temperature on the structural and optical properties of the films deposited onto the glass substrate using an aqueous solution of copper chloride were explored.31

The advent of aerosol assisted chemical vapor deposition (AACVD) has also made it possible to deposit metal chalcogenide materials from solution based precursors, such as metal xanthate and metal dithiocarbamate complexes. In these processes, precursors in a solvent are nebulized and carried by an inert gas to an heated substrate where deposition occurs. AACVD is scalable, and the requirement of precursor volatility is removed thus expanding the palette of possible metal complex precursors that can be of use. An excellent review of the area has been produced by Knapp and Carmalt.32

The benefits of spray pyrolysis (excellent scalability) can potentially be combined with those of AACVD (wide precursor choice and products); in this Article, we investigate the feasibility of deposition of main group and transition metal sulfides directly using spray deposition. Molecular precursors based on metal dithiocarbamates decompose under thermal stress to the corresponding metal sulfide. We, therefore, reasoned that if we spray solutions of these molecular precursors to coat materials, followed by a relatively low temperature thermal treatment step (<500 °C), we could obtain metal sulfides from a very simple processing route with great potential for scalability, and be able to coat substrates with complex topologies. The molecular precursor method that we propose is particularly powerful for this approach as the deposited precursors can be sprayed in the correct stoichiometry to produce the desired metal sulfide after thermolysis. By using single precursors we could access binary sulfides. By using mixtures two or three precursors in tandem, we could potentially access the higher ternary and quaternary transition metal and main group sulfides. This Article explores these possibilities.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All solvents and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received without further purification.

Instrumentation

Elemental analysis and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA with a heating rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen from 30 to 600 °C) were performed by the University of Manchester, Department of Chemistry microanalytical laboratory. Powder X-ray diffraction (p-XRD) was performed using Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer. All samples were scanned between 10° to 80° using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) with step 0.02° and integration time of 3 s. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Specac single reflectance ATR instrument (4000–400 cm–1, resolution 4 cm–1). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was carried out using a TESCAN Mira3 microscope. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy was performed with an LC FEGSEM + OI EBSD + EDX instrument.

Synthesis of Molecular Precursors

All the metal complexes in this study were prepared as described previously.33−41 A brief description of the synthesis and characterization of each metal complex is given in the Supporting Information.

Air-Spray Deposition of Metal Sulfides

Glass substrates were thoroughly washed with acetone to remove any contamination and used for the deposition of metal sulfide films. In a typical deposition, 0.2 g (0.35 mmol) of precursors was dissolved in 25 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and filtered. The solution was held in a small glass container attached to a shop-bought artistic air brush. The solution was carried in the form of spray by a stream of argon (500–600 cm3 min–1) onto the glass substrates placed on the hot plate at 200 °C. The solvent evaporated quickly and left the precursor in the form of uniform film on the glass substrate. The spraying time, the solution flow rate and the distance between the nozzle and the substrate were optimized to fabricate smooth, homogeneous and visually crack free films. These films were loaded into a quartz tube and heated between 350 to 450 °C under Ar for 30–60 min (see Table 1 for specific temperatures and Figure S8 for a picture of the apparatus).

Table 1. Elemental Quantification and Structural Characterisation by pXRD and Raman Spectroscopy of Binary, Ternary and Quaternary Metal Sulfides Deposited in This Studya.

| compounds | precursor formula and stoichiometry | processing temperature (°C) | EDXS (atomic %) | metal sulfide empirical formula (found, normalized to sulfur) | major X-ray reflections (2θ deg/hkl, Cu Kα)b | Raman scattering peak maxima/cm–1 (phonon, exc 514 nm) | structural assignment (corresponding mineral name) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fe(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | Fe: 50.5, S: 49.5 | FeS | 30.7 (200) | no peaks observed | hexagonal FeS (troilite) |

| 34.6 (201) | |||||||

| 44.7 (202) | |||||||

| 65.1 (213) | |||||||

| 2 | Ni(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Ni: 46.6, S: 53.4 | Ni0.9S1.0 | 30.2 (100)* | no peaks observed | |

| 3 | Ga(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | Ga: 40.7, S: 59.3 | Ga2S3 | 29.7 (111) | no peaks observed | cubic γ-Ga2S3 |

| 49.4 (220) | |||||||

| 58.7 (311) | |||||||

| 4 | In(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | In: 34.4, S: 65.6 | In1.9S3.0 | 14.2 (111) | 132 | cubic α-In2S3 |

| 23.3 (220) | 165 | ||||||

| 27.4 (311)* | 248 | ||||||

| 33.1 (400) | 312 | ||||||

| 43.4 (511) | 365 | ||||||

| 47.6 (440) | |||||||

| 5 | Cd(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Cd: 48.0, S: 52.0 | CdS | 24.8 (100) | 300 (1LO) | hexagonal CdS (greenockite) |

| 26.5 (002) | 600 (2LO) | ||||||

| 28.2 (101) | |||||||

| 6 | Bi(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | Bi: 49.5, S: 50.5 | BiS | 15.7 (020) | 121 | orthorhombic Bi2S3 |

| 22.4 (220) | 227 | ||||||

| 25.0 (111) | |||||||

| 28.6 (211) | |||||||

| 48.3 (060) | |||||||

| 7 | Mn(S2CNEt2)2 | 350 | Mn: 50.3, S: 49.7 | MnS | 34.3 (200) | no peaks observed | cubic MnS (alabendite) |

| 49.3 (220) | |||||||

| 8 | Pb(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Pb: 49.3, S:50.7 | PbS | 30.0 (200)* | 130 (LAM/TAM) | cubic PbS (galena) |

| 431 (2LO) | |||||||

| 602 (3LO) | |||||||

| 9 | Ag(S2CNEt2) | 450 | Ag: 65.8, S: 34.2 | Ag2S | 25.9 (−111) | no peaks observed | monoclinic Ag2S (acanthite) |

| 37.7 (−103) | |||||||

| 10 | Sb(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | Sb: 32.7, S: 67.3 | Sb2.1S3.0 | 11.1 (101) | 127 | orthorhombic Sb2S3 |

| 15.6 (200) | 146 | ||||||

| 17.5 (201) | 185 | ||||||

| 22.2 (202) | 234 | ||||||

| 24.8 (301) | 279 | ||||||

| 28.4 (302) | 300 | ||||||

| 35.4 (402) | |||||||

| 45.4 (404) | |||||||

| 11 | Co(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Co: 52.4, S: 47.6 | Co1.1S1.0 | 30.6 (100) | no peaks observed | hexagonal CoS |

| 34.7 (002) | |||||||

| 35.3 (101) | |||||||

| 46.9 (102) | |||||||

| 54.4 (110) | |||||||

| 12 | Cu(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Cu: 48.5, S: 51.5 | Cu0.9S1.0 | 27.3 (102) | 471 | tetragonal Cu2S |

| 32.6 (111) | |||||||

| 39.0 (104) | |||||||

| 45.3 (200) | |||||||

| 13 | Zn(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Zn: 44.3, S: 55.7 | Zn0.8S1.0 | 31.7 (107)* | no peaks observed | hexagonal ZnS (wurtzite) |

| 14 | Sn(But)2(S2CNEt2)2 | 400 | Sn: 50.5, S: 49.5 | SnS | 31.4 (111)* | 158 (B3g) | orthrhombic SnS (herzenbergite) |

| 182 (B1g) | |||||||

| 15 | WS3(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | W: 28.8, S: 71.2 | W0.8S2.0 | 33.4 (101) | 171 | hexagonal 2H-WS2 (tungstenite) |

| 59.2 (008) | 351 (E12g) | ||||||

| 415 (A1g) | |||||||

| 16 | Mo(S2CNEt2)4 | 450 | Mo: 33.8, S: 66.2 | MoS2 | 32.8 (100) | 382 (E12g) | hexagonal 2H-MoS2 (molybdenite) |

| 33.6 (101) | 406 (A1g) | ||||||

| 58.6 (110) | |||||||

| 1 and 12 | 1 equiv of Fe(S2CNEt2)3 | 450 | Cu: 19.7, Fe: 25.8, S: 54.6 | Cu0.7Fe0.9S2.0 | 29.5 (112)* | 215 (A1) | tetragonal CFS (chalcopyrite) |

| 1 equiv Cu(S2CNEt2)2 | 49.0 (204) | 281 (A1) | |||||

| 57.9 (312) | 392 (B2) | ||||||

| 12, 13, and 14 | 2 equiv of Cu(S2CNEt2)2 | 450 | Cu: 30.5, Zn: 12.0,Sn: 9.4 S: 48.1 | Cu2.5Zn1.0Sn0.8S4.0 | 28.5 (112)* | 285 | tetragonal CZTS (kesterite) |

| 1 equiv of Zn(S2CNEt2)2 | 47.3 (220) | 332 | |||||

| 1 equiv of Sn(But)2(S2CNEt2)2 | 56.2 (312) | ||||||

The EDX data is compiled from integrated emission peak intensity in EDX spectra.

Asterisk (*) indicates the preferred orientation.

Results and Discussion

Thermogravimetric Analysis of Metal Dithiocarbamate Precursors

All precursors were subject to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to investigate the decomposition of the metal dithiocarbamate complexes to the corresponding metal sulfides and in order to find suitable processing temperatures to convert the air sprayed precursors to metal sulfides (Figure S1). This is especially important for the higher ternary and quaternary systems where incongruent decomposition could potentially produce unwanted mixtures of binary chalcogenides rather than the target materials. TGA of diethyl dithiocarbamato complexes of cadmium, indium, copper, zinc, nickel, lead, and iron show single-step decompositions in the temperature range of 300–400 °C. The TGA profile of molybdenum precursor shows a four step decomposition with final residue of 27.82%, which is within the experimental error of the calculated value 27.88% for MoS2. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of WS3L2 also shows four step decomposition at 133.50, 197.08, 319.71, and 394.13 °C which correspond to weight losses of 10.7%, 16.7%, 7.79%, and 7.84%, respectively, with a total weight loss of 43.0% (calcd 57%). The difference between the calculated and theoretical weight loss is potentially due to decomposed ligand contamination under the conditions imposed by TGA.

Structural Characterization of Deposited Binary Metal Sulfides

TGA profiles of the precursors revealed the complete decomposition of metal complexes in the temperature range of 300–450 °C. Therefore, the optimum annealing temperature for the films deposited by air spray was selected to be 450 °C. Metal dithiocarbamates were loaded into a quartz tube and heated in a furnace at this temperature under argon for 1 h to allow the complete decomposition to their respective metal sulfides. Powder X-ray diffraction (p-XRD) and Raman spectroscopy were used in tandem to identify the crystalline phases of the products, and the results of these analyses are summarized in Table 1 (see Supporting Information for full discussion with p-XRD patterns and Raman spectra). In all cases, we demonstrate the production of a single identifiable crystalline phase that corresponded to the metal sulfide for each metal dithiocarbamate studied, for both transition metal chalcogenide and main group chalcogenide examples. We note that in some cases using an excitation wavewlength of 514 nm did not give rise to observable Raman signals which is potentially due to interference from luminescence in these samples.

Electron Microscopy Characterization of Deposited Binary Metal Sulfides

The morphologies of the metal sulfide films deposited by the air-spray annealing method were investigated by SEM (Figure 1). The growth of MoS2 nanostructures has been demonstrated recently with a direct melt process from molybdenum dithiocarbamates.42 It has also recently been demonstrated that such molecules are useful precursors for producing nanocrystalline MoS2 at the liquid–liquid interface at room temperature.43 Indeed the SEM images of as-deposited MoS2 from air spray deposition reveals sheet-like crystallites as suggested by the p-XRD patterns and consistent with its layered crystal structure. The growth of the nanocrystals along the planes (100) and (101) consistent parallel to the substrate surface rather than lamellar morphology corresponding to (002) planes of MoS2 film as reported in the previous studies.44−47 This was further investigated by analyzing MoS2 sheets using TEM (Figure S7), which reveals nanosheets of MoS2 rather than multilayered bulk structure, which confirm the growth of nanosheets in the [hk0] direction, that is, the basal plane as suggested by the preferred orientation and significant peak broadening in the p-XRD pattern that leads to the disappearance of the (002) peak, which is usually intense in samples of bulk molybdenite. TEM images of MoS2 nanosheets are also consistent with the result from Raman spectroscopy which shows two strong peaks at the in-plane E2g1 and the out-of-plane A1g vibration both are the characteristics peaks of MoS2. The selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of the deposited MoS2 nanosheets is highly diffuse and broadened rings are consistent with the p-XRD pattern and TEM images of MoS2.48−51 Hence, it may be possible to produce TMDC nanosheets directly from a spray-on process as demonstrated here.

Figure 1.

SEM images of binary metal sulfide films deposited onto glass substrates by air spray. Each film is labeled for clarity with the crystalline metal sulfide produced based on p-XRD and Raman data collected.

The WS2 film deposited by air spray annealing method also show sheetlike morphology whilst films deposited by AACVD onto glass substrates show floret-like morphology.20 The morphology of MnS film shows the aggregation of small particles leads to bulk particles, which may be due to the formation of a large number of small nuclei prior to crystallization of the final material.52 Iron sulfide films exhibit small hexagonal platelike crystallites agglomerated together into clusters. We note that FeS films deposited by different methods also show hexagonal plates and sheet like crystallites. The crystallites of cobalt sulfide (CoS) show petal like morphology with different sizes, while some of these are agglomerated into clusters. The SEM analysis of NiS and Cu2S reveal small crystallites with spheroidal morphology. The surface morphology of the Ag2S film examined by SEM shows that it is comprised of densely packed and homogeneous small sized grains, while the zinc sulfide film is constituted by spheroidal crystallites.

SEM images of CdS film shows highly agglomerated spherical nanoparticles. The SEM images of gallium sulfide (Ga2S3) and lead sulfide (PbS) films revealed the cubic morphologies of the crystallites deposited onto glass substrates. Indium sulfide (In2S3) films shows floret like morphology. The SnS film is polycrystalline with sheet-like crystallite morphology. The sheets are randomly distributed throughout the film without any cracks and holes. The SEM images of antimony sulfide (Sb2S3) and bismuth sulfide (Bi2S3) films show nanoparticles agglomerated on the surface of dense and uniform nanowires.

EDX elemental quantification of the peak intensity of the elemental emission lines was performed for all binary sulfide materials produced by sampling microscale areas of the as-deposited materials in the SEM (Table 1). In most cases, the materials show the expected elemental stoichiometry for binary metal sulfides, with the exception of the sulfides of Ni, In, Sb, Co, Cu, W, and Zn, which deviate away from the ideal elemental composition. We note that the results in the table are normalized to the sulfur content; it is impossible to tell if they are sulfur rich or metal deficient from the EDX quantification alone; further characterization of the electronic properties of the materials would be needed to determine this, which is beyond the scope of this study here which focuses on the synthetic pathway.

Air Spray Deposition and Characterization of an Exemplar Ternary Metal Chalcogenide: Copper Iron Sulfide (CFS)

Ternary materials including the elements Cu–Fe–S have attracted attention for photovoltaic applications where they act as inexpensive and robust absorber layers.53,54 There are six copper iron compounds in the Cu–Fe–S ternary system including chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bornite (Cu5FeS4), cubanite (CuFe2S3), mooihoekite (Cu9Fe9S16), talnakhite (Cu9Fe8S16) and haycockite (Cu4Fe5S8). In particular, chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) is a semiconductor which has been extensively studied due to its narrow band gap.55−57 A number of methods have been used for the deposition of chalcopyrite thin films including flash evaporation, vacuum evaporation, electrochemical deposition, and chemical bath deposition (CBD).57−60

We found that we could also successfully deposit CFS films using air spraying of molecular precursors. The solution for deposition was prepared by dissolving precursors 1 and 12 with 1:1 ratio into 25 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and stirred for 30 min. The solution was sprayed onto the preheated glass substrates. These samples were then loaded into a quartz tube and heated in a furnace at temperature 450 °C under argon for 1 h to allow for complete decomposition of metal dithiocarbamate complexes into their respective metal sulfides. The p-XRD pattern of the as-deposited material (Figure 2) could be indexed to tetragonal chalcopyrite (CuFeS2, ICDD No. 00-009-0423) with preferred orientation of growth along the (112) plane. The Raman spectrum of CuFeS2 (Figure 3) shows two strong peaks at 215.2 and 281.4 cm–1, which we assign to the A1 optical phonon modes and a weak peak at 292.1 cm–1, which corresponds to the B2 optical phonon mode of CuFeS2.61

Figure 2.

p-XRD pattern of copper iron sulfide (CuFeS2; CFS) deposited onto a glass substrate by air-spraying a mixture of 1 and 12 in a 1:1 mol ratio. The standard pattern (red sticks) is tetragonal chalcopyrite (CuFeS2, ICDD No. 00-009-0423).

Figure 3.

Raman spectrum of copper iron sulfide (CuFeS2; CFS) film deposited onto a glass substrate by air-spraying a mixture of 1 and 12 in a 1:1 mol ratio.

Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy of the CuFeS2 film deposited onto glass substrate by air-spray annealing show that the chalcopyrite materials are sulfur rich and copper deficient (Table 1). The SEM images of the CuFeS2 film shows that the material is comprised of microscale crystallites with spheroidal morphology (Figure 4). EDX spectrum mapping of the CuFeS2 film show that the distributions of copper, iron, and sulfur are uniform throughout the particles as demonstrated by their spatial colocalization at the microscale (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

SEM images of copper iron sulfide (CFS) film deposited onto glass substrate by air-spray substrate by air spraying a mixture of 1 and 12 in a 1:1 mol ratio.

Figure 5.

EDX spectrum maps (20 kV) of the Cu Kα, Fe Kα and S Kα emission lines from CuFeS2 thin films deposited onto a glass substrate by air spraying a mixture of 1 and 12 in a 1:1 mol ratio.

Air Spray Deposition and Characterization of an Exemplar Quaternary Metal Chalcogenide: Copper Zinc Tin Sulfide (CZTS)

CZTS is a quaternary metal sulfide semiconductor with a direct band gap of ∼1.5 eV and a high optical absorption coefficient (∼104–105 cm–1), making it extremely useful for solar devices which now have PCEs above 10%.62 Previously, the deposition of CZTS thin films has been carried out using several methods including thermal evaporation, pulsed laser deposition, electron beam evaporation, spin coating, and electrodeposition.63−66 Olger et al. reported the deposition of CZTS by sputter deposition of metallic layers onto Mo coated glass substrates followed by the annealing at 530 and 560 °C in the presence of elemental sulfur.67 Long et al. reported deposition of CZTS thin films from sol–gels followed by sulfurization.68 Benachour et al. studied the influence of annealing time on the structural and optical properties of CZTS thin films deposited by dip-coating from a mixture of hydrated chloride salts of copper, zinc, tin, and thiourea dissolved in methoxyethanol.69

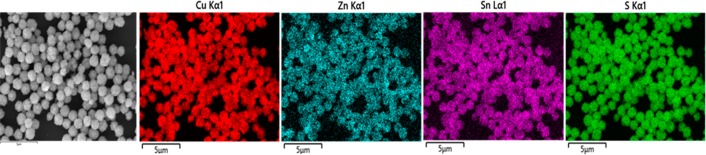

CZTS films were successfully deposited using air spray deposition. The solution for deposition was prepared by dissolving the precursors 12, 13, and 14 with 2:1:1 ratio into 25 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and stirred for 30 min. The solution was loaded into the magazine and sprayed onto the preheated glass substrates. These substrates were loaded into a quartz tube and heated in a furnace at temperature 450 °C under argon for 1 h to allow for complete decomposition of metal dithiocarbamate complexes into their respective metal sulfides. The p-XRD pattern of CZTS confirms the deposition of kesterite, Cu2ZnSnS4 (Figure 6a, ICDD No. 00-026-0575) with some minor reflections from cubic copper sulfide, Cu2S (ICDD No. 00-002-1287), which is consistent with a copper rich CZTS film. The preferred orientation of the crystallites growth is along the (112) plane. The Raman spectrum of the thin film shows two main peaks at 284.9 and 332.3 cm–1, which can be attributed to CZTS (Figure 6b).70 Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy of CZTS films confirms that the deposited phase is copper-rich, which is suggested by p-XRD pattern with minor diffraction peaks of Cu2S. The surface morphology of the CZTS films is investigated by SEM and images taken at different magnifications are shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that small sheets agglomerate to form the floret like clusters of different sizes. EDX spectrum mapping of Cu, Zn, Sn, and S emission lines in the as-deposited CZTS demonstrate that the constituent elements are uniformly distributed throughout the film at the microscale (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Structural characterization of an exemplar quaternary sulfide. (a) p-XRD pattern of copper zinc tin sulfide (Cu2ZnSnS4; CZTS) deposited onto glass substrate by air-spraying a mixture of 12, 13, and 14 in a 2:1:1 mol ratio. The standard pattern presented (red sticks) is tetragonal kesterite, (Cu2ZnSnS4, ICDD No. 00-026-0575). The asterisk (*) indicates reflections from cubic copper sulfide, Cu2S (ICDD No. 00-002-1287). (b) Raman spectrum of the as-deposited CZTS showing Raman shifts at 284.9 and 332.3 cm–1 and corresponding to tetragonal kesterite.

Figure 7.

SEM images at various magnifications of CZTS deposited onto glass substrate by air spraying a mixture of 12, 13, and 14 in a 2:1:1 mol ratio.

Figure 8.

EDX spectrum maps (20 kV) of Cu Kα, Zn Kα, Sn Lα, and S Kα emission in Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films deposited onto a glass substrate by air spraying a mixture of 12, 13, and 14 in a 2:1:1 mol ratio. The elements are observed to be spatially colocalized at the microscale consistent with formation of the quaternary material.

Conclusions

A range of binary, ternary (CFS), and quaternary (CZTS) metal sulfide films have been successfully deposited onto the glass substrates by air-spray annealing method. All the films were deposited using metal diethyldithiocarmato complexes as single source precursors. Powder X-ray diffraction in tandem with Raman spectroscopy was used to identify the phases of the materials. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) confirms that empirical formulae are close to those of the target materials. Electron microscopy revealed that the as-deposited materials are polycrystalline with varying morphologies. Significantly, we were also able to use the same approach for the deposition of CFS and CZTS, which are materials pertinent to inexpensive and sustainable solar energy generation using the photovoltaic effect.

In summary, we have shown that air spray annealing is a very simple and inexpensive method for the deposition of binary, ternary, and quaternary metal sulfide films. This now gives the exciting prospect of simple 'spray and go' direct deposition processes for metal sulfide semiconductors. We believe that, given the range of materials successfully deposited here, that the approach is likely to be universal–and that with the correct choice of precursors can be used to deposit many metal chalcogenide materials, on potentially large substrates with complex topologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding and technical support from BP through the BP International Centre for Advanced Materials (BP-ICAM), which made this research possible. We thank Dr Ben Dennis-Smither (BP Hull) for useful discussions. D.J.L. acknowledges support from EPSRC (Grants EP/R020590/1 and EP/R022518/1).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsaem.9b02359.

Synthetic procedures and characterization of metal dithiocarbamate complexes including TGA profiles, p-XRD patterns and Raman spectra and discussion, TEM of MoS2, and a picture of apparatus used for spray deposition (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lim J.; Park M.; Bae W. K.; Lee D.; Lee S.; Lee C.; Char K. Highly efficient cadmium-free quantum dot light-emitting diodes enabled by the direct formation of excitons within InP@ ZnSeS quantum dots. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (10), 9019–9026. 10.1021/nn403594j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H.; Bai X.; Wang A.; Wang H.; Qian L.; Yang Y.; Titov A.; Hyvonen J.; Zheng Y.; Li L. S. High-Efficient Deep-Blue Light-Emitting Diodes by Using High Quality ZnxCd1-xS/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24 (16), 2367–2373. 10.1002/adfm.201302964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y.; Zhou Z.; Li T.; Wang K.; Li J.; Wei Z. Versatile Crystal Structures and (Opto) electronic Applications of the 2D Metal Mono-, Di-, and Tri-Chalcogenide Nanosheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900040. 10.1002/adfm.201900040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bragagnolo J. A.; Barnett A. M.; Phillips J. E.; Hall R. B.; Rothwarf A.; Meakin J. D. The design and fabrication of thin-film CdS/Cu 2 S cells of 9.15-percent conversion efficiency. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1980, 27 (4), 645–651. 10.1109/T-ED.1980.19917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riha S. C.; Parkinson B. A.; Prieto A. L. Solution-based synthesis and characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4 nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (34), 12054–12055. 10.1021/ja9044168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riha S. C.; Parkinson B. A.; Prieto A. L. Compositionally Tunable Cu2ZnSn (S1–x Se x) 4 Nanocrystals: Probing the Effect of Se-Inclusion in Mixed Chalcogenide Thin Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (39), 15272–15275. 10.1021/ja2058692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskin C. K.; Yang W. C.; Hages C. J.; Carter N. J.; Joglekar C. S.; Stach E. A.; Agrawal R. 9.0% efficient Cu2ZnSn (S, Se) 4 solar cells from selenized nanoparticle inks. Prog. Photovoltaics 2015, 23 (5), 654–659. 10.1002/pip.2472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinsermsuksakul P.; Hartman K.; Bok Kim S.; Heo J.; Sun L.; Hejin Park H.; Chakraborty R.; Buonassisi T.; Gordon R. G. Enhancing the efficiency of SnS solar cells via band-offset engineering with a zinc oxysulfide buffer layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102 (5), 053901. 10.1063/1.4789855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catti M.; Noel Y.; Dovesi R. Full piezoelectric tensors of wurtzite and zinc blende ZnO and ZnS by first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2003, 64 (11), 2183–2190. 10.1016/S0022-3697(03)00219-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Shi X.; Xu F.; Zhang L.; Zhang W.; Chen L.; Li Q.; Uher C.; Day T.; Snyder G. J. Copper ion liquid-like thermoelectrics. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11 (5), 422–425. 10.1038/nmat3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi S.; Candolfi C.; Vaney J.-B.; Ohorodniichuk V.; Masschelein P.; Dauscher A.; Lenoir B. Assessment of the thermoelectric performance of polycrystalline p-type SnSe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104 (21), 212105. 10.1063/1.4880817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.-D.; Lo S.-H.; Zhang Y.; Sun H.; Tan G.; Uher C.; Wolverton C.; Dravid V. P.; Kanatzidis M. G. Ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric figure of merit in SnSe crystals. Nature 2014, 508 (7496), 373–377. 10.1038/nature13184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Hu E.; Hu K.; Xu Y.; Hu X. J. T. I. Tribol. Int. 2015, 92, 172–183. 10.1016/j.triboint.2015.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Tu J.; Gan L.; Li C. J. W. Wear 2006, 261 (2), 140–144. 10.1016/j.wear.2005.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S.; Zabinski J. Lubricants: super slippery solids. Nature 1997, 387 (6635), 761. 10.1038/42820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Shavel A.; An X.; Luo Z.; Ibáñez M.; Cabot A. Cu2ZnSnS4-Pt and Cu2ZnSnS4-Au heterostructured nanoparticles for photocatalytic water splitting and pollutant degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (26), 9236–9239. 10.1021/ja502076b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shakban M.; Matthews P. D.; Savjani N.; Zhong X. L.; Wang Y.; Missous M.; O’Brien P. The synthesis and characterization of Cu 2 ZnSnS 4 thin films from melt reactions using xanthate precursors. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52 (21), 12761–12771. 10.1007/s10853-017-1367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. A.; Dunlop E. D.; Hohl-Ebinger J.; Yoshita M.; Kopidakis N.; Ho-Baillie A. W.Y. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 55). Prog. Photovoltaics 2020, 28, 3–15. 10.1002/pip.3228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa T. E.; McNaughter P. D.; Raftery J.; Lewis D. J.; O’Brien P. Full compositional control of PbS x Se 1– x thin films by the use of acylchalcogourato lead (ii) complexes as precursors for AACVD. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (47), 16938–16943. 10.1039/C8DT03443E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza G.; Venkateswaran S. P.; Thomas A. G.; O’Brien P.; Lewis D. J. Chemical vapour deposition of chromium-doped tungsten disulphide thin films on glass and steel substrates from molecular precursors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6 (35), 9537–9544. 10.1039/C8TC01991F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vikraman D.; Thiagarajan S.; Karuppasamy K.; Sanmugam A.; Choi J.-H.; Prasanna K.; Maiyalagan T.; Thaiyan M.; Kim H.-S. Shape-and size-tunable synthesis of tin sulfide thin films for energy applications by electrodeposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 479, 167–176. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.02.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udachyan I.; R. S. V.; C. S. P. K.; Kandaiah S. Anodic fabrication of nanostructured CuxS and CuNiSx thin films and their hydrogen evolution activities in acidic electrolytes. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 7674–7682. 10.1039/C9NJ00962K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Ramos D. E.; Martínez-Enríquez A. I.; González L. A. CuS films grown by a chemical bath deposition process with amino acids as complexing agents. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019, 89, 18–25. 10.1016/j.mssp.2018.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi M. S.; Ibrahim K.; Ahmed N. M.; Hmood A.; Azzez S. A. Growth and Characterization of Tin Sulphide Nanostructured Thin Film by Chemical Bath Deposition for Near-Infrared Photodetector Application. Solid State Phenom. 2019, 290, 220–224. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/SSP.290.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park G. H.; Nielsch K.; Thomas A. 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Thin Films Obtained by Chemical Gas Phase Deposition Techniques. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6 (3), 1800688. 10.1002/admi.201800688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N. P.; Meng X.; Elam J. W.; Martinson A. B. Atomic layer deposition of metal sulfide materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (2), 341–348. 10.1021/ar500360d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochel J. M.Electrically conducting coatings on glass and other ceramic bodies. US Patent US2564707, 1951.

- Hill J. E.; Chamberlin R. R.. Process for making conductive film. US Patent US3148084, 1964.

- Sayed M. H.; Robert E. V.; Dale P. J.; Gütay L. Cu2SnS3 based thin film solar cells from chemical spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Films 2019, 669, 436–439. 10.1016/j.tsf.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Jia Z.; Yuan H.; Zhu W.; Ni Y.; Zhu X.; Dou X. The properties of the earth abundant Cu 2 SnS 3 thin film prepared by spray pyrolysis and rapid thermal annealing route. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2019, 30 (5), 4519–4526. 10.1007/s10854-019-00740-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moumen A.; Hartiti B.; Comini E.; Arachchige H. M. M.; Fadili S.; Thevenin P.; et al. Preparation and characterization of nanostructured CuO thin films using spray pyrolysis technique. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 127, 2–10. 10.1016/j.spmi.2018.06.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp C. E.; Carmalt C. J. Solution based CVD of main group materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45 (4), 1036–1064. 10.1039/C5CS00651A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M.; Akhter J.; Malik M. A.; O’Brien P.; Tuna F.; Raftery J.; Helliwell M. Deposition of iron sulfide nanocrystals from single source precursors. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21 (26), 9737–9745. 10.1039/c1jm10703h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone A. A.; Lewis E. A.; Savjani N.; Zhong X. L.; Haigh S. J.; O’Brien P.; Lewis D. J. Single-Source Precursor for Tungsten Dichalcogenide Thin Films: Mo1–xWxS2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) Alloys by Aerosol-Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29 (9), 3858–3862. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b05271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien P.; Waters J. Deposition of Ni and Pd Sulfide Thin Films via Aerosol-Assisted CVD. Chem. Vap. Deposition 2006, 12 (10), 620–626. 10.1002/cvde.200506387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horley G. A.; Lazell M. R.; O’Brien P. Deposition of Thin Films of Gallium Sulfide from a Novel Liquid Single-Source Precursor, Ga (SOCNEt2) 3, by Aerosol-Assisted CVD. Chem. Vap. Deposition 1999, 5 (5), 203–205. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmler M.; Lazell M.; O’Brien P.; Otway D.; Park J.-H.; Walsh J. The growth of thin films of copper chalcogenide films by MOCVD and AACVD using novel single-molecule precursors. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2002, 13 (9), 531–535. 10.1023/A:1019665428255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haggata S.; Malik M. A.; Motevalli M.; O’Brien P.; Knowles J. Synthesis and Characterization of Some Mixed Alkyl Thiocarbamates of Gallium and Indium, Precursors for III/VI Materials: The X-ray Single-Crystal Structures of Dimethyl-and Diethylindium Diethyldithiocarbamate. Chem. Mater. 1995, 7 (4), 716–724. 10.1021/cm00052a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamen L. D.; Revaprasadu N.; Pullabhotla R. V.; Nejo A. A.; Ndifon P. T.; Malik M. A.; O’Brien P. Synthesis of multi-podal CdS nanostructures using heterocyclic dithiocarbamato complexes as precursors. Polyhedron 2013, 56, 62–70. 10.1016/j.poly.2013.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garg B.; Garg R.; Reddy M. Synthesis and spectral characterization of zinc (II), cadmium (II) and mercury (II) with tetrahydroquinoline and isoquinoline dithiocarbamates. Indian J. Chem. 1993, 32A, 697–700. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien P.; Nomura R. Single-molecule precursor chemistry for the deposition of chalcogenide (S or Se)-containing compound semiconductors by MOCVD and related methods. J. Mater. Chem. 1995, 5 (11), 1761–1773. 10.1039/jm9950501761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng N. T.; Hopkinson D. G.; Spencer B. F.; McAdams S. G.; Tedstone A. A.; Haigh S. J.; Lewis D. J. Direct synthesis of MoS2 or MoO3 via thermolysis of a dialkyl dithiocarbamato molybdenum(IV) complex. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (1), 99–102. 10.1039/C8CC08932A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins E. P. C.; McAdams S. G.; Hopkinson D. G.; Byrne C.; Walton A. S.; Lewis D. J.; Dryfe R. A. W. Room-Temperature Production of Nanocrystalline Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) at the Liquid-Liquid Interface. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (15), 5384–5391. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b05232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. Y.; Besmann T. M.; Stott M. W. Preparation of MoS 2 thin films by chemical vapor deposition. J. Mater. Res. 1994, 9 (6), 1474–1483. 10.1557/JMR.1994.1474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S.; Kumar A.; Kumar M.; Singh B. P. Large area vertical aligned MoS2 layers toward the application of thin film transistor. Mater. Lett. 2019, 250, 64–67. 10.1016/j.matlet.2019.04.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Lee J. K.; Zhou S.; Pasta M.; Warner J. H. Synthesis of Surface Grown Pt Nanoparticles on Edge-Enriched MoS2 Porous Thin Films for Enhancing Electrochemical Performance. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (2), 387–397. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b03540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adeogun A.; Afzaal M.; O’Brien P. Studies of Molybdenum Disulfide Nanostructures Prepared by AACVD Using Single-Source Precursors. Chem. Vap. Deposition 2006, 12 (10), 597–599. 10.1002/cvde.200504203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Mu X.; Zheng C.; Liu S.; Zhu Y.; Gao X.; Wu T. Structural defects in 2D MoS2 nanosheets and their roles in the adsorption of airborne elemental mercury. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 240–249. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savjani N.; Lewis E. A.; Bissett M. A.; Brent J. R.; Dryfe R. A.; Haigh S. J.; O’Brien P. Synthesis of Lateral Size-Controlled Monolayer 1 H-MoS2@ Oleylamine as Supercapacitor Electrodes. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28 (2), 657–664. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b04476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su D.; Dou S.; Wang G. Ultrathin MoS2 Nanosheets as Anode Materials for Sodium-Ion Batteries with Superior Performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5 (6), 1401205. 10.1002/aenm.201401205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone A. A.; Lewis D. J.; Hao R.; Mao S. M.; Bellon P.; Averback R. S.; Warrens C. P.; West K. R.; Howard P.; Gaemers S.; Dillon S. J.; O’Brien P. Mechanical Properties of Molybdenum Disulfide and the Effect of Doping: An in Situ TEM Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7 (37), 20829–20834. 10.1021/acsami.5b06055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. C.; Singh M. P.; Singh O.; Chandi P. S. Influence of synthesis and calcination temperatures on particle size and ethanol sensing behaviour of chemically synthesized SnO2 nanostructures. Sens. Actuators, B 2009, 143 (1), 226–232. 10.1016/j.snb.2009.09.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolden C. A.; Kurtin J.; Baxter J. B.; Repins I.; Shaheen S. E.; Torvik J. T.; Rockett A. A.; Fthenakis V. M.; Aydil E. S. Photovoltaic manufacturing: Present status, future prospects, and research needs. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A 2011, 29 (3), 030801. 10.1116/1.3569757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakutayev A. Brief review of emerging photovoltaic absorbers. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2017, 4, 8–15. 10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin I.; Goodman C.; Pengelly A. New semiconductors with the chalcopyrite structure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1956, 103 (11), 609–610. 10.1149/1.2430171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K. i.; Teranishi T.; Sato K. Optical Absorption of CuFeS2 and Fe-Doped CuAlS2 and CuGaS2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1974, 36 (1), 311–311. 10.1143/JPSJ.36.311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkat L.; Hamdadou N.; Morsli M.; Khelil A.; Bernede J. Growth and characterization of CuFeS2 thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 297 (2), 426–431. 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.10.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korzun B.; Galyas A. Thin Films of CuFeS2 Prepared by Flash Evaporation Technique and Their Structural Properties. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48 (5), 3351–3354. 10.1007/s11664-019-07005-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prabukanthan P.; Thamaraiselvi S.; Harichandran G.; Theerthagiri J. Single-step electrochemical deposition of Mn2+ doped FeS2 thin films on ITO conducting glass substrates: Physical, electrochemical and electrocatalytic properties. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2019, 30 (4), 3268–3276. 10.1007/s10854-018-00599-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonpe D.; Gattu K.; More G.; Upadhye D.; Mahajan S.; Sharma R. In Synthesis of CuFeS2 Thin Films from Acidic Chemical Baths, AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing, 2016; p 020676. [Google Scholar]

- Aup-Ngoen K.; Thongtem T.; Thongtem S.; Phuruangrat A. Cyclic microwave-assisted synthesis of CuFeS2 nanoparticles using biomolecules as sources of sulfur and complexing agent. Mater. Lett. 2013, 101, 9–12. 10.1016/j.matlet.2013.03.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K.; Nakazawa T. Electrical and optical properties of stannite-type quaternary semiconductor thin films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1988, 27 (11R), 2094. 10.1143/JJAP.27.2094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C.; Shi G.; Chen Z.; Yang P.; Yao M. Deposition of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films by vacuum thermal evaporation from single quaternary compound source. Mater. Lett. 2012, 73, 89–91. 10.1016/j.matlet.2012.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanalakar S.; Agawane G.; Shin S. W.; Suryawanshi M.; Gurav K.; Jeon K.; Patil P.; Jeong C.; Kim J.; Kim J. A review on pulsed laser deposited CZTS thin films for solar cell applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 619, 109–121. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araki H.; Mikaduki A.; Kubo Y.; Sato T.; Jimbo K.; Maw W. S.; Katagiri H.; Yamazaki M.; Oishi K.; Takeuchi A. Preparation of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films by sulfurization of stacked metallic layers. Thin Solid Films 2008, 517 (4), 1457–1460. 10.1016/j.tsf.2008.09.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scragg J. J.; Dale P. J.; Peter L. M. Towards sustainable materials for solar energy conversion: Preparation and photoelectrochemical characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10 (4), 639–642. 10.1016/j.elecom.2008.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olgar M. A.; Tomakin M.; Küçükömeroğlu T.; Bacaksiz E. Growth of Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) thin films using short sulfurization periods. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 056401. 10.1088/2053-1591/aaff78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long B.; Cheng S.; Ye D.; Yue C.; Liao J. Mechanistic aspects of preheating effects of precursors on characteristics of Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) thin films and solar cells. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 115, 182–190. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2019.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benachour M.; Bensaha R.; Moreno R. Annealing duration influence on dip-coated CZTS thin films properties obtained by sol–gel method. Optik 2019, 187, 1–8. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes P.; Salomé P.; Da Cunha A. Growth and Raman scattering characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517 (7), 2519–2523. 10.1016/j.tsf.2008.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.