Abstract

Objective

The 2019 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for the management of cervical cancer screening abnormalities recommend 1 of 6 clinical actions (treatment, optional treatment or colposcopy/biopsy, colposcopy/biopsy, 1-year surveillance, 3-year surveillance, 5-year return to regular screening) based on the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, adenocarcinoma in situ, or cancer (CIN 3+) for the many different combinations of current and recent past screening results. This article supports the main guidelines presentation1 by presenting and explaining the risk estimates that supported the guidelines.

Methods

From 2003 to 2017 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), 1.5 million individuals aged 25 to 65 years were screened with human papillomavirus (HPV) and cytology cotesting scheduled every 3 years. We estimated immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for combinations of current test results paired with history of screening test and colposcopy/biopsy results.

Results

Risk tables are presented for different clinical scenarios. Examples of important results are highlighted; for example, the risk posed by most current abnormalities is greatly reduced if the prior screening round was HPV-negative. The immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ used to decide clinical management are shown.

Conclusions

The new risk-based guidelines present recommendations for the management of abnormal screening test and histology results; the key risk estimates supporting guidelines are presented in this article. Comprehensive risk estimates are freely available online at https://CervixCa.nlm.nih.gov/RiskTables.

Key Words: risk-based, management guidelines, cervical screening, HPV

Risk Estimate and Management Tables

-

Abnormal Screening Results

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for abnormal screening results, when there are no known prior HPV test results

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ after a prior HPV-negative screen documented in the medical record

-

Surveillance following results not requiring immediate colposcopic referral

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for results obtained in follow-up of HPV-negative ASC-US

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for results obtained in follow-up of HPV-negative LSIL

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for results obtained in follow-up of HPV-positive NILM

Receipt of colposcopy/biopsy results

-

Surveillance visit following colposcopy/biopsy finding less than CIN 2 (no treatment)

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ postcolposcopy at which CIN 2+ was not found, following referral for low-grade results

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ postcolposcopy at which CIN 2+ was not found, following referral for high-grade results

-

Follow-up after treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3

Immediate and 5-year risks after treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3

Long-term follow-up when there are 2 or 3 negative follow-up test results after treatment of CIN 2 or CIN 3

INTRODUCTION

The 2019 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines describe 6 clinical actions that providers can use when managing patients with abnormal cervical cancer screening test results: treatment; optional treatment or colposcopy/biopsy; colposcopy/biopsy; 1-year surveillance; 3-year surveillance; and return to 5-year regular screening.1 These clinical actions are recommended based on a patient's risk of either currently having or subsequently developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3), adenocarcinoma in-situ (AIS), or cancer (defined subsequently as CIN 3+). Exploration of numerous potential risk factors led to the determination that a patient's CIN 3+ risk can be estimated based on current human papillomavirus (HPV) and cytology test results and recent history of test results, colposcopic evaluation and biopsy results, and treatments.

The 2019 guidelines comprehensively use and expand upon the principle of “equal management for equal risks” that was introduced in the 2012 guidelines.2 Specifically, management is based on a patient's risk of CIN 3+, regardless of what combination of test results yields that risk level. The guidelines make recommendations based on immediate CIN 3+ risk, which is the probability of patient currently having CIN 3+, and 5-year CIN 3+ risk, which gives the probability of developing CIN 3+ over the ensuing 5 years.1,3 We conducted an extensive data analysis effort to produce risk estimates for all combinations of tests and recent screening history, considering 5 clinical scenarios: (a) current abnormal screening results, (b) surveillance of past screening results not requiring immediate colposcopic referral, (c) management based on colposcopy/biopsy results, (d) postcolposcopy surveillance after less than CIN 2 histology, and (e) posttreatment follow-up. This article navigates the most relevant risk-based management tables that inform the new guidelines for clinicians. The comprehensive risk database is stored at the National Institutes of Health, publicly accessible through this link: https://CervixCa.nlm.nih.gov/RiskTables. A user-friendly, electronic presentation of these risk estimates and their related recommendations is available via a smartphone app, and a web version (available via asccp.org).

METHODS

Study Population

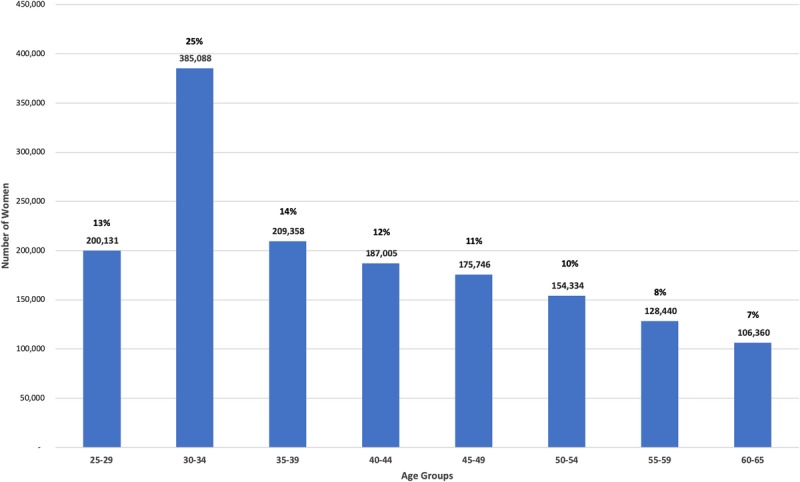

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC)/National Cancer Institute Guidelines Cohort has been previously described.3–5 In brief, from 2003 to 2017, cervical cancer screening was conducted among individuals aged 25 to 65 years, using HPV testing with Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2; Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and cytology. The age distribution of the study cohort at the first visit at which they received cotesting (i.e., enrollment) is shown in Figure 1. The largest age cohort included ages 30 to 34 years (25%), followed by 35 to 39 years (14%) and 25 to 29 years (13%). The accumulation of individuals in the 30- to 34-year age group reflects the start of cotesting at 30 years and older from 2003 until KPNC guidelines changed in 2013 to recommend beginning cotesting at age 25 years. As a result, every year in KPNC screening participants became age eligible for cotesting resulting in a peak at the age group 30 to 34 years and, starting in 2013, the same effect in those aged 25 to 29 years. We restricted the analytic sample to 1,546,462 screened individuals with both HPV and cytology results, excluding those with a prior hysterectomy, histopathologic CIN 2+ diagnosis, missing HPV results or with cytology reports of missing, uncertain, or not cervical. Cytology was performed at KPNC regional and local laboratories. The HPV status was based on HC2 testing performed on a second cervical specimen (collected at the same time as the cytology specimen) at the KPNC regional laboratory. Histopathology was also centralized. Clinical outcomes were obtained by linkage to KPNC cytology and histopathology electronic medical records.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of women at their first cotest visit based on age groups: First visit age group 30- to 34-year frequency reflects initiation of cotesting at 30 years and older starting in 2003. The 25- to 29-year age group frequency reflects KPNC initiation of cotesting starting at age 25 in 2013.

Variables

Cytology results at KPNC were reported based on the 2001 Bethesda System, categorized as: negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), atypical squamous cells cannot exclude an high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H), atypical glandular cells (AGC) (note, subcategorization of AGC is described in Perkins et al.1), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or worse (HSIL+), and inadequate.

We reported HPV status as negative versus positive for infection with any of the 13 pooled high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68), recognizing that HC2 also detects through cross-reaction a percentage of closely related HPV types (e.g., 53, 66, 67, 70, 82, and 82v).6 A subset of HC2-positive cervical specimens at KPNC had HPV typing, as part of the National Cancer Institute-KPNC Persistence and Progression Study. These results are reported separately by Demarco et al.7

For the main analyses and consensus guidelines, precancer was defined as a histopathologic diagnosis of CIN 3+ (CIN 3/AIS/cancer). CIN 2 was de-emphasized because it is a less reliable histopathologic definition of precancer. However, ancillary analyses considered CIN 2+ (CIN 2/CIN 3/AIS/cancer) as an alternative definition of precancer and cancer by itself as an alternative outcome (please refer to the comprehensive tables available online at https://CervixCa.nlm.nih.gov/RiskTables).

Statistical Analysis

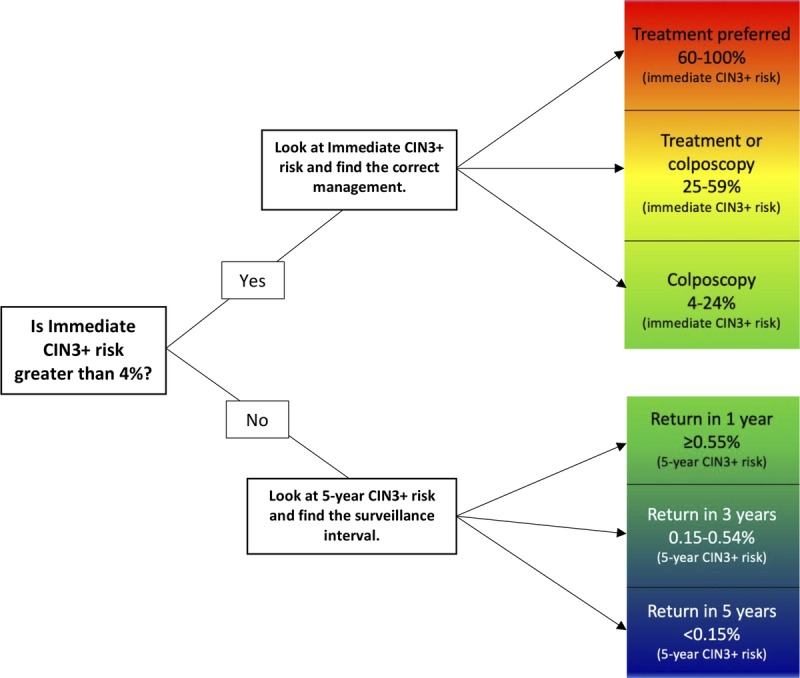

We used prevalence-incidence mixture models.8–10 The model is a mixture of logistic regression for events present at the time of the current visit (prevalent disease) and proportional hazards model for events occurring after the current visit (incident disease). We estimated risk of CIN 3+ at years 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5; most decisions considered the immediate risks at year 0 and the 5-year risks (see Figure 2 and Cheung et al. for details).3

FIGURE 2.

Determining suggested management based on calculated risk.

Data Presentation: Clinical Scenarios

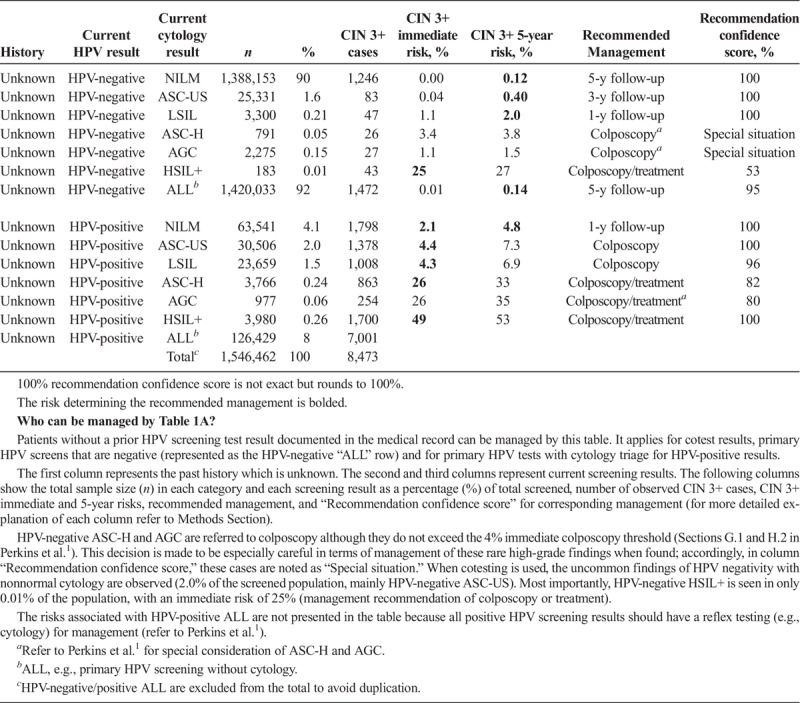

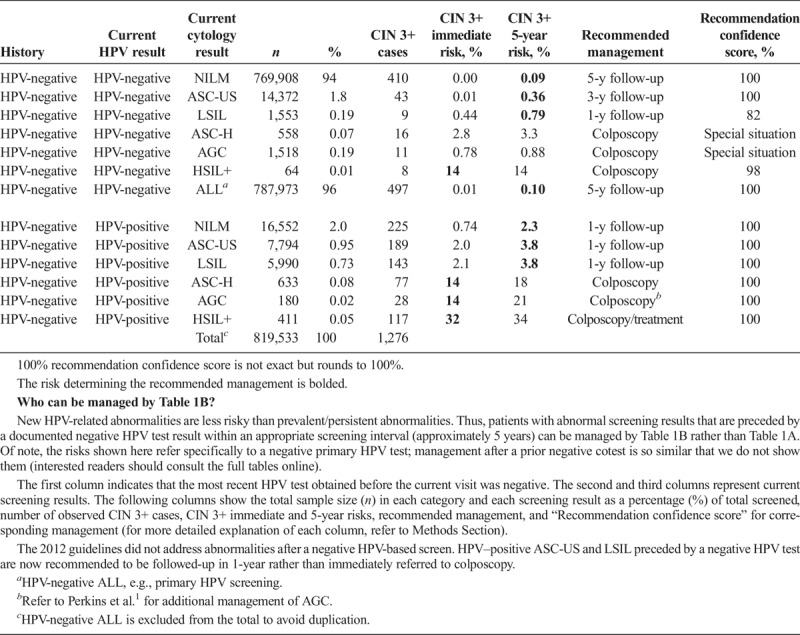

Risk-based management tables are organized under the 5 clinical scenarios. It is important to emphasize that for a given patient over time, a clinician is likely to consult various tables as the management scenarios are encountered, from initial abnormality to resolution. Scenario 1 describes initial management of abnormal screening results. Table 1A addresses patients without a documented recent HPV test result. To qualify for Table 1B, a patient's current abnormal screening test result must be preceded by a negative HPV test documented in the medical record within the past approximately 5 years (e.g., a normal screening interval).

TABLE 1A.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ for Abnormal Screening Results, When There Are No Known Prior HPV Test Results

TABLE 1B.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ After a Prior HPV-Negative Screen Documented in the Medical Record

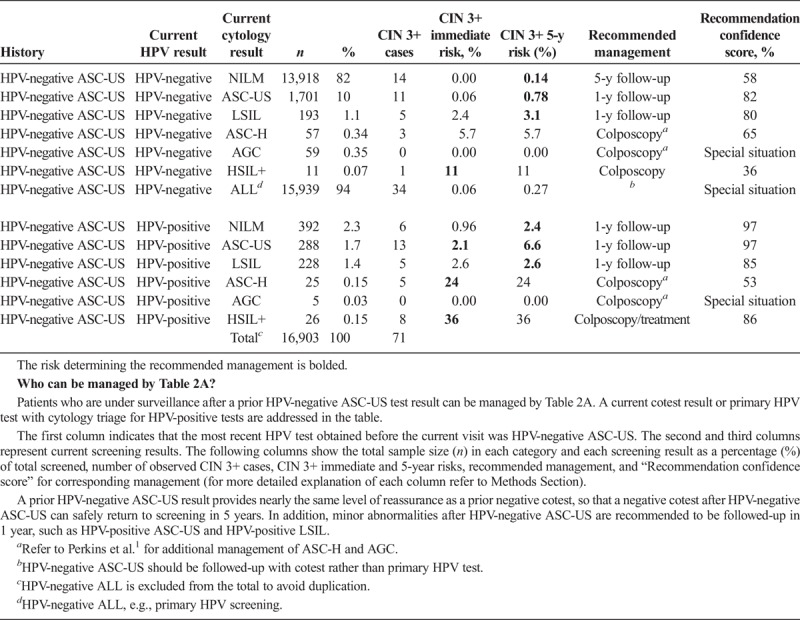

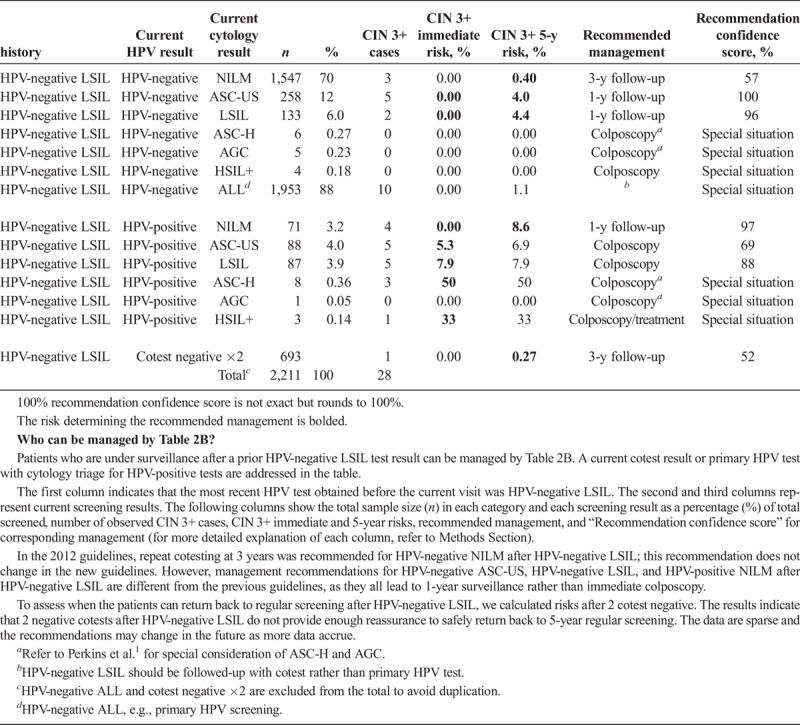

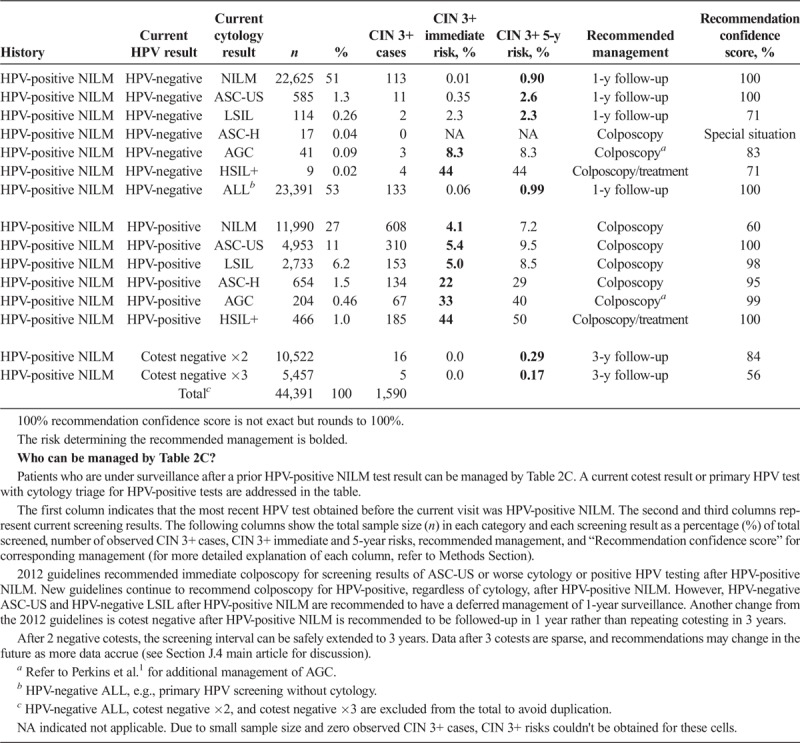

Scenario 2 describes surveillance after abnormal results not requiring immediate colposcopic referral. Management of current cotest results is described after a previous result of HPV-negative ASC-US (see Table 2A), HPV-negative LSIL (Table 2B), and HPV-positive NILM (Table 2C).

TABLE 2A.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ for Results Obtained in Follow-up of HPV-Negative ASC-US

TABLE 2B.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ for Results Obtained in Follow-up of HPV-Negative LSIL

Table 2C.

Immediate and 5-year risks of CIN 3+ for results obtained in follow-up of HPV-positive NILM

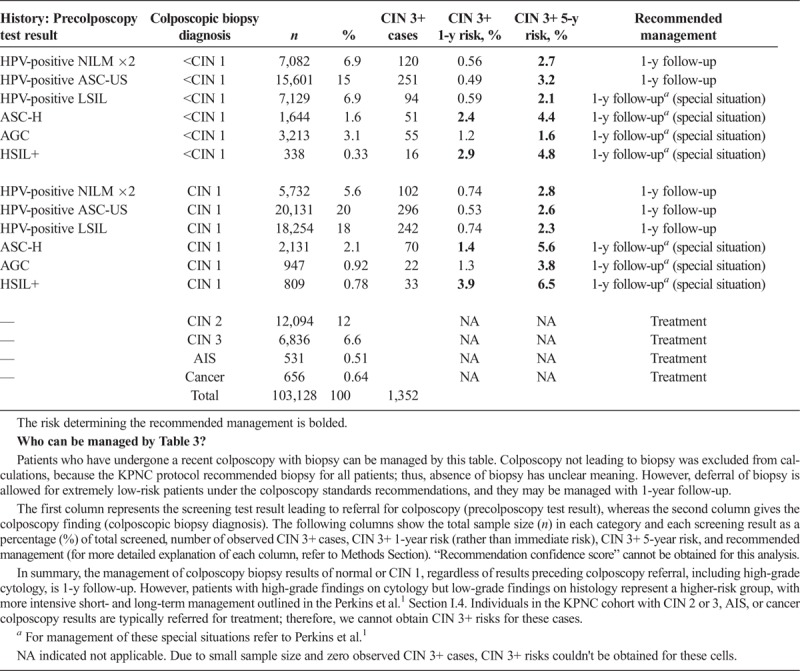

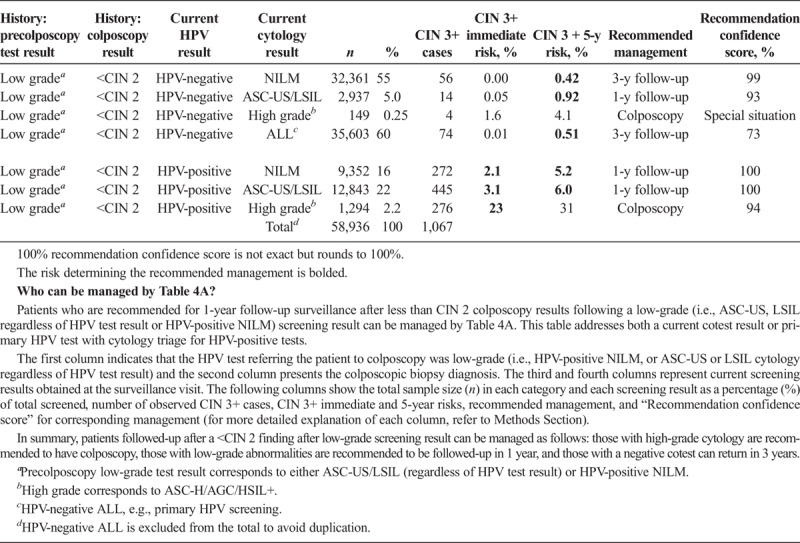

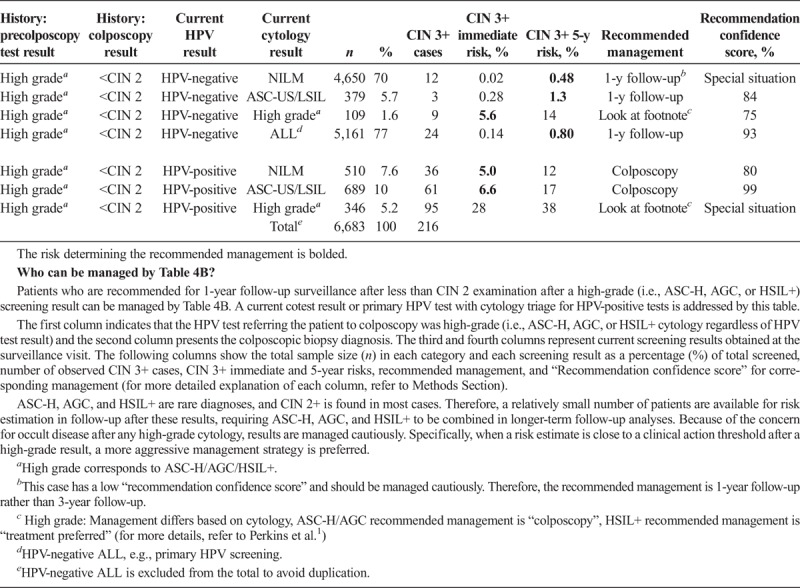

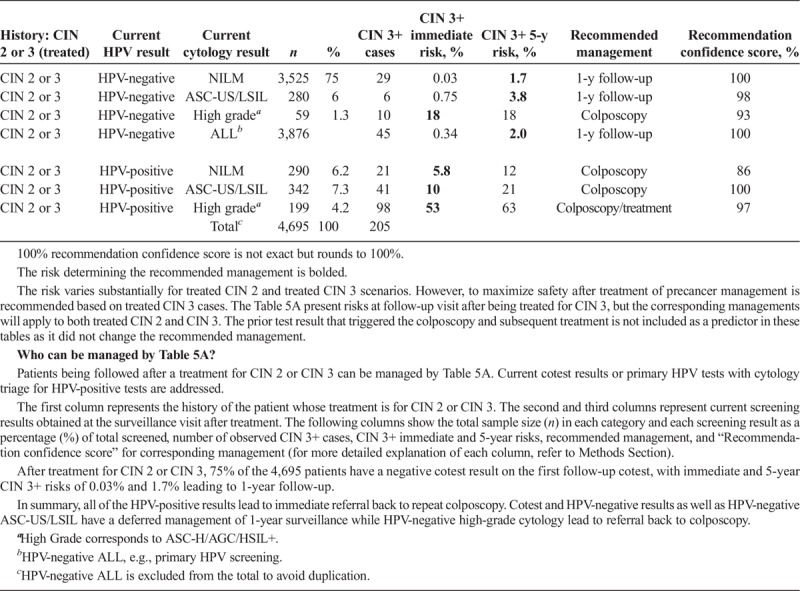

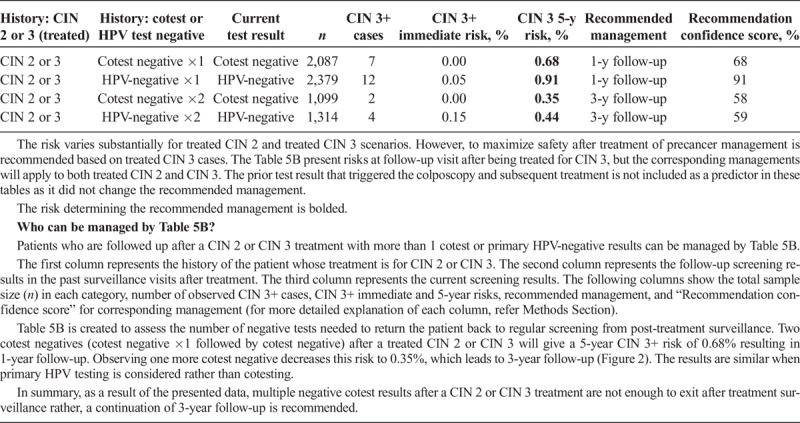

Scenario 3, management upon receipt of colposcopy/biopsy results, describes subsequent management based on the colposcopy/biopsy diagnosis (see Table 3). Scenario 4 describes management after a colposcopy at which CIN 2+ was not found (i.e., colposcopy/biopsy results were CIN 1 or normal). Table 4A describes CIN 3+ risks when the index cotest was low grade (i.e., LSIL, ASC-US, or HPV-positive NILM). Table 4B describes CIN 3+ risks when the index cotest was high grade (i.e., ASC-H, AGC, HSIL+). Scenario 5 addresses management after treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3, either short term (see Table 5A) or longer term (see Table 5B).

TABLE 3.

CIN 3+ 1-Year and 5-Year Risks Upon Receipt of Colposcopy/Biopsy Result

TABLE 4A.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ Postcolposcopy at Which CIN 2+ Was Not Found, After Referral for Low-Grade Results

TABLE 4B.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks of CIN 3+ Postcolposcopy at Which CIN 2+ Was Not Found, After Referral for High-Grade Results

TABLE 5A.

Immediate and 5-Year Risks After Treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3

TABLE 5B.

Long-Term Follow-up When There Are 2 or 3 Negative Follow-up Test Results After Treatment of CIN 2 or CIN 3

Data Presentation: Current Results and History

Two central questions underlie risk estimations: (a) What are the current results? (b) What past results affect the risk estimate for the current results? The “current results” are those for which the clinician is seeking guidance, either an HPV test or cotest result (see Tables 1A–2C 4A–5B) or a colposcopy/biopsy result (see Table 3). The past results that impact risk estimates are noted under “history.” Table 1A refers to patients without a recent documented HPV test or cotest result, so the history is simply “unknown.” In Table 1B, “history” refers to recent documented negative HPV test (management after a prior negative cotest is so similar that we do not show them, interested readers can consult the full tables online). However, documented negative cytology provides relatively less reduction in risk compared with a negative HPV or cotest as history. Therefore, patients with a negative cytology history will still be managed by Table 1A. In Tables 2ABC, “history” refers to the abnormal screening test result preceding the current result: HPV-negative ASC-US (Table 2A), HPV-negative LSIL (Table 2B), and HPV-positive NILM (Table 2C). In Table 3, “history” refers to the precolposcopy test results. In Table 4A, “history” refers to both the colposcopy result (<CIN 2) and a low-grade test result preceding colposcopy. In Table 4B, “history” again refers to both the colposcopy result (<CIN 2) and preceding test result but addresses when a high-grade test result preceded the colposcopy.

In Tables 5A and 5B, “history” refers to treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3, and “current results” are HPV test results or cotest results after treatment. For Tables 5A and 5B, the risk estimation in this scenario (i.e., posttreatment) derives specifically from treated CIN 3 and the test result at the follow-up visit after treatment. The risk remains higher for treated CIN 3 compared with CIN 2 scenarios. However, to maximize safety after treatment of precancer, management is recommended based on the risks of patients treated for CIN 3. Thus, the management recommendations apply to both treated CIN 2 and CIN 3.

Data Presentation: Total Numbers, Risks Estimates, and Recommended Management

We report the total number of patients and the number of CIN 3+ cases reported among those patients for each combination of “current results” and “history.” We present the number and percentage of the population with corresponding current test results in columns “n” and “%,” respectively. The total number of CIN 3+ detected from the initial screen until the end of follow-up is presented in column “CIN 3+ cases.” Columns “CIN 3+ immediate risk, %” and “CIN 3+ 5-y risk, %” give the estimated immediate and 5-year CIN 3+ risks (as percent probabilities). CIN 3+ immediate risk is the estimated probability of observing CIN 3+ if the patient were referred to colposcopy based on the current visit. CIN 3+ 5-year risk is the probability of observing CIN 3+ within 5 years after the current visit. The following column “Recommended management” gives the recommendation for clinical management based on the clinical action thresholds decided by the consensus group. Certain high-risk situations are managed based on factors other than risk estimates and denoted as “Special Situations.” These included rare result combinations for which insufficient data caused risk estimates to be unstable and those for which the cancer risk estimates and/or scientific literature indicated disproportionately high cancer risks relative to CIN 3+ risks, leading to recommendations for more aggressive management. Special situations are covered in Sections H and I of Perkins et al.1 and explained in the footnotes of the tables.

Data Presentation: Recommendation Confidence Score

The column named “Recommendation confidence score, %” indicates the percent probability that the KPNC risk estimates fall within the risk range dictating the recommended management (based on the sample size and how close the estimated risks are to clinical action thresholds, Cheung et al.3). A high percent suggests statistical precision, defined as adequate numbers of CIN 3+ events to generate a stable risk estimate and confidence that the estimate is yielding the correct recommendation based on the KPNC data. It is the percent probability that the estimated risk, from a random sample of that size, would support the determined management option, rather than the neighboring options. For instance, a “Recommendation confidence score” of 95% for a recommendation of 1-year surveillance means 95% statistical confidence that the recommended management is correct when considering the KPNC data, rather than colposcopy or 3-year surveillance. Generalizability to other clinical settings/populations is thought to be good, as outlined in the methods article.3 Nonetheless, the recommendation confidence score should not be misinterpreted as the true probability that a recommendation is absolutely correct. No such perfect prediction is possible or implied; the measure is given more as a warning when the percentage is low, signifying lack of confidence in the recommendation. With this strong caveat, a recommendation confidence score above 80% is suggested as a helpful guide by the statisticians directing the analyses to represent good reassurance for the recommended management, although again there is no absolute threshold for such a statistical intuition.

RESULTS

Using the Risk Tables to Determine Clinical Management

Suggested management is determined by matching a patient's risk estimate to a clinical action threshold (see Figure 2). Expedited treatment (i.e., without preceding colposcopy/biopsy) is preferred for patients with immediate CIN 3+ risk 60% or greater, treatment or colposcopy/biopsy is acceptable for risk 25% or greater and less than 60%, and colposcopy/biopsy is recommended for risk 4.0% or greater and less than 25%. Patients with immediate CIN 3+ risks of less than 4.0% are recommended to have follow-up surveillance, and their deferred clinical management is guided by 5-year risks of CIN 3+: 1-year follow-up for risk 0.55% or greater (but under the colposcopy threshold of 4.0% immediate risk), 3-year follow-up for risk 0.15% or greater and less than 0.55%, and return to routine screening at 5-year intervals for risk less than 0.15%.

To apply these clinical action thresholds using the tables in this article, the first step is to determine whether the risk denoted in the “CIN 3+ immediate risk” column is greater than or less than 4%. For immediate risks greater than 4%, the recommended management is determined by the immediate CIN 3+ risk. For immediate risks less than 4%, the “CIN 3+ 5-year risk” column is used to determine recommended follow-up interval. In the tables, the risk used to determine the recommended management is bolded. We will illustrate how risk estimates are used to determine management using hypothetical patient examples.

Patient 1: A 32-year-old woman presents for screening, she denies having colposcopy or treatment in the past, but her medical records are not available so her history is unknown. Her current test results are HPV-positive ASC-US.

This patient has an abnormal current result and an unknown/undocumented history, therefore consult Table 1A. Her immediate CIN 3+ risk is 4.4%. The recommended management is colposcopy because her immediate estimated risk is greater than 4% (the colposcopy threshold) and less than 25% (the treatment or colposcopy threshold). In the KPNC database, 30,506 women had this result combination, among whom 1,378 had CIN 3+ (detected from initial screen through the end of follow-up), leading to a recommendation confidence score rounding to 100%.

Patient 2: A 35-year-old woman presents for screening, she denies having colposcopy or treatment in the past, and medical record documentation shows that her last result was an HPV-negative NILM screening result 5 years ago. Her current test results are HPV-positive ASC-US.

This patient has an abnormal current result and history of a documented negative HPV and cytology cotest, therefore consult Table 1B (although Table 1B is for negative HPV—without cytology—history, the CIN 3+ risks are very similar with cotest negative history). Her immediate CIN 3+ risk is less than 4%, so the 5-year risk is used to determine management. Her 5-year risk is 3.8%, which is above the 0.55% threshold for a 3-year return, so the recommended management is 1-year follow-up. In the KPNC database, 7,794 women had this result combination, among whom 189 had CIN 3+, leading to a recommendation confidence score of 100%.

Patient 3: A 32-year-old woman presents for follow-up. Her history is a cotest result 1 year ago that was HPV-positive NILM. Her result today is HPV-negative ASC-US.

This patient has a history of an abnormal result that did not require colposcopy, therefore consult the Tables 2ABC section corresponding to her initial abnormal result. For HPV-positive NILM, this is Table 2C (use Tables 2A, B for HPV-negative ASC-US and LSIL, respectively). This patient's immediate CIN 3+ risk is less than 4%, so the 5-year risk is used to determine the recommended management. Her 5-year risk is 2.6%, which is above the 0.55% threshold for a 3-year return, so the recommended management is 1-year follow-up. In the KPNC database, 585 women had this result combination, among whom 11 had CIN 3+, leading to a recommendation confidence score of 100%.

Patient 4: A 32-year-old woman has a history of an HPV-positive LSIL result. Her colposcopic biopsy shows CIN 1.

This patient has colposcopy/biopsy result, therefore consult Table 3. Because we know the colposcopy/biopsy results of the patient, calculating immediate CIN 3+ risks is meaningless. Therefore, in this scenario, we are rather interested in 1- and 5-year CIN 3+ risks of the patients. For this patient, 1-year CIN 3+ risk is less than 4%, so the 5-year risk is used. Her 5-year risk is 2.3%, which is above the 0.55% threshold for a 3-year return, so the recommended management is 1-year follow-up. In the KPNC database, 18,254 women had this result combination, among whom 242 had CIN 3+.

Patient 5: A 32-year-old woman has a history of an HPV-positive LSIL result, followed by a colposcopic biopsy showing CIN 1. She presents for follow-up at 1 year and her cotest result is HPV-positive ASC-US.

This patient has a history of a low-grade screening test result, followed by a colposcopy where CIN 2+ was not found, and now presents with new follow-up test results, therefore consult the Table 4A. Her immediate CIN 3+ risk is less than 4%, so the 5-year risk is used. Her 5-year risk is 6.0%, which is above the 0.55% threshold for a 3-year return, so the recommended management is 1-year follow-up. In the KPNC database, 12,843 women had this result combination, among whom 445 had CIN 3+, leading to a recommendation confidence score of 100%.

Patient 6: A 32-year-old woman has a history of CIN 3 that was treated with a diagnostic excisional procedure (loop electrosurgical excision procedure). She presents for follow-up at 6 months and her cotest result is HPV-positive NILM.

This patient has a history of treated CIN 3, therefore consult Table 5A. Her immediate CIN 3+ risk is 5.6%. This exceeds the 4% colposcopy threshold but is below the threshold for offering colposcopy or treatment (25%), so the recommended management is colposcopy. In the KPNC database, 290 women had this result combination, among whom 21 had CIN 3+, leading to a recommendation confidence score of 86%.

Patient 7: A 32-year-old woman has a history of CIN 3 that was treated with diagnostic loop electrosurgical excisional procedure (LEEP), followed by 1 negative HPV test. She presents for follow-up and her second HPV test result is also negative.

This patient has a history of treated CIN 3 and more than 1 negative follow-up test, therefore consult Table 5B. Her immediate CIN 3+ risk is less than 4%, so the 5-year risk is used. Her 5-year risk is 0.91%, which is above the 0.55% threshold for a 3-year return, so the recommended management is 1-year follow-up. In the KPNC database, 2,379 women had this result combination, among whom 12 had CIN 3+, leading to a recommendation confidence score of 91%.

Summary of Concepts Underlying Changes From 2012 Guidelines1

Negative HPV tests reduce risk. An HPV-negative test is virtually as reassuring as a negative cotest. The only instance in which HPV-negative is not reassuring is when cytology is HSIL+. However, this test combination is extremely rare (0.01% of overall screens in Tables 1A, B).

As history, a negative HPV test followed by a positive HPV test suggests a new or reappearing infection, which is lower risk than a persistent infection. Therefore, a prior HPV-negative test leads to lower risks (see Table 1B) than unknown history (see Table 1A). For HPV-positive ASC-US and LSIL, this reduction in risks leads to a change of recommended management. A documented negative HPV test result before HPV-positive ASC-US and LSIL almost halves the immediate CIN 3+ risk (4.4%, 4.3%–2.0%, 2.1%, respectively) and changes the recommended management from immediate colposcopy to 1-year follow-up (see Table 1B).

The HPV–negative ASC-US is also a reassuring history result (see Table 2A). A negative cotest after HPV-negative ASC-US warrants return to screening at 5-year intervals (5-year CIN 3+ risk is 0.14%, which is less than the 0.15% 5-year surveillance threshold). Minor abnormalities (e.g., HPV-positive ASC-US and HPV-positive LSIL) after HPV-negative ASC-US are recommended to be followed in 1 year, rather than proceed immediately to colposcopy (see Table 2A). Though higher risk than HPV-negative ASC-US, HPV-negative LSIL is less risky than previously thought, allowing minor abnormalities after HPV-negative LSIL (i.e., HPV-negative ASC-US, HPV-negative LSIL, and HPV-positive NILM) to be followed in 1 year, rather than proceed immediately to colposcopy (see Table 2B). In addition, HPV-negative ASC-US and HPV-negative LSIL after HPV-positive NILM are recommended to have a deferred management of 1-year surveillance (see Table 2C).

Colposcopy performed for low-grade abnormalities, which confirms the absence of CIN 2+ reduces risk. After a colposcopic examination performed for low-grade abnormalities (e.g.; HPV-positive NILM × 2, HPV-positive ASC-US, or HPV-positive LSIL) at which CIN 1 or less was confirmed via biopsy, minor abnormalities (e.g., HPV-positive ASC-US and HPV-positive LSIL) found on the first follow-up test are recommended to be followed in 1 year, rather than proceed immediately to colposcopy (see Table 4A). Because all repeat abnormalities were referred back to colposcopy at KPNC, we cannot estimate risks for additional rounds of follow-up. Therefore, the 2019 guidelines recommend referral for colposcopy for abnormal results occurring on subsequent rounds of follow-up testing.

A history of HPV-positive results increases risk, even when the current result is negative. After HPV-positive NILM, a negative cotest is recommended to be followed-up in 1 year rather than 3 years (since 5-year CIN 3+ risk is 0.9%, higher than the 0.55% 3-year surveillance threshold, see Table 2C), as was recommended in 2012 guidelines.2 Only after 2 negative cotests can the screening interval can be safely extended to 3 years because the 5-year CIN 3+ risk drops to 0.29% (see Table 2C). Data after 3 negative cotests continue to support a 3-year interval, although data are sparse and recommendations may change in the future as more data accrue (See Section J.4 main article for discussion).

Prior treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3 increases risk. After treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3, most treated patients (82.3%, in total 4,695) have a negative HPV test result on the first follow-up screening, with immediate and 5-year CIN 3+ risks of 0.34% and 2.0% leading to 1-year follow-up (see Table 5A). Any abnormality on any follow-up test leads to re-referral to colposcopy, including HPV-negative ASC-US/LSIL cytology, HPV-negative high-grade cytology, and all HPV-positive results (see Table 5A). Two negative HPV tests (HPV negative × 1 followed by HPV negative in Table 5B) after a treated CIN 2 or CIN 3 will give a 5-year CIN 3+ risk of 0.91% resulting in 1-year follow-up (see Table 5B). Observing one more negative HPV test result decreases this risk to 0.44%, which leads to 3-year follow-up (see Table 5B). Results are similar when cotesting is considered rather than primary HPV testing. Even after 3 negative HPV tests or cotests, risks remain well above the 0.15% 5-year CIN 3+ risk threshold needed to return to screening at 5-year intervals, leading to a recommendation of continued follow-up at 3-year intervals.

DISCUSSION

We detail how risk estimates are used for clinical management according to the principles laid out by the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Guidelines. We also lay out basic principles underlying risk-based management: (a) HPV-negative test results reduce risk; (b) colposcopic examinations at which CIN 2+ is not found reduce risk; (c) HPV-positive test results increase risk; and (d) prior treatment for CIN 2 or CIN 3 increases risk. Although these principles are intuitive, their ramifications are far-reaching. At a population level, the risk of CIN 3+ for screening participants at any given age is highest at the time of the initial HPV-based screen (0.45% immediate CIN 3+ risk for patients new to HPV testing in KPNC aged 25–65 years). The first screening round will detect most prevalent CIN 3+ and reduce the risk of CIN 3+ in future screening rounds. This situation is exemplified by patients entering an HPV-based screening program for the first time.

Among 1,546,462 people at the first visit, 92% had a primary HPV-negative test result. Individuals with a negative HPV screening results are at very low risk of developing CIN 3+ within the next 5 years (0.14%); thus, a 5-year screening interval is recommended. As populations begin screening with HPV testing, most individuals will test negative, reducing their need for colposcopy in subsequent screening rounds.

Among the 8% of the population that initially tested HPV positive, immediate CIN 3+ risks ranged from 2.1% for HPV-positive NILM (below the colposcopy threshold), to 4.3% and 4.4% for HPV-positive ASC-US and LSIL, respectively (defining the colposcopy threshold), to 25% and 26% for HPV-negative HSIL+ and HPV-positive ASC-H, respectively (defining the treatment or colposcopy threshold), to 49% for HPV-positive HSIL+. Reaching the 60% threshold for preferring treatment requires an additional risk factor, such as HPV-16 infection7 or a history of not having been screened.

Management recommendations are similar to the 2012 guidelines2 for patients with an unknown screening history but are modulated to be more or less intensive for patients with a documented prior negative HPV test results or prior colposcopy results showing CIN 1 or less (indicating lower risk) or prior HPV-positive results or treatment for CIN 3 (indicating higher risk). Note that these data demonstrate that multiple negative cotest results after a CIN 2 or CIN 3 treatment are not enough to exit posttreatment surveillance. Rather, a continuation of 3-year follow-up is recommended long term, based on the follow-up data we currently have available (see Table 5B), as well as longer-term follow-up from population-based studies.1

In the future, we anticipate additional scenarios will be added as needed. One example would be changes in the risk score of the vaccinated population. HPV vaccination is expected to decrease the prevalence rate in the young population (patients between ages 25–29 years), which might change the recommended management in different scenarios for this age group. Once enough data accrue on the vaccinated population, the risk scores will be re-evaluated to determine recommended management for the vaccinated population.

LIMITATIONS

Although we had high statistical confidence in most of our estimates, the measure “Recommendation confidence score” is given more as a warning when the percentage is low, signifying lack of confidence in the recommendation because of data limitations (lack of observations or small number of observed cases).

In addition, the risks for some rare combinations could not be estimated with confidence. The ASC-H, AGC, and HSIL+ are rare cytologic results, and CIN 2+ is found in the majority. Therefore, risk estimation subsequent to diagnoses of CIN 1 or less after these cytologic results were less reliable, and because of the concern for occult disease after any high-grade cytology, results are managed cautiously. In other situations, some current cytologic results are grouped together to avoid small categories with almost zero CIN 3+ cases, allowing for calculation of risk estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

The unique KPNC screening experience, and the long-term collaborative dedication of our KPNC colleagues, permitted this detailed examination of risks. The length and size of the program, and its indisputable high quality, lend confidence to the internal comparisons of risk after different test results. The question of external validity of KPNC data-based management guidelines is addressed elsewhere in this issue.3 The generalizability of risk estimates and clinical action thresholds seems high based on comparison with 4 other data sets from varied populations. As other large prospective data sets become available, additional checks on external validity will be conducted as part of the proposed plan for ongoing updates to the guidelines.

The risk-based management tables shown in abbreviated form in this article underlie the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Consensus Management Guidelines. Moving from result-based to risk-based guidelines, it is important for the clinician to understand how these risk estimates were obtained and how to use them in clinical management of cervical screening. This article explains risk-based management tables under 5 different clinical scenarios that comprise most management visits and decisions.

A more extensive version of these tables (which include risk estimates with CIN 2+, CIN 3+, and cancer end points, as well as risk estimates for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years under each end point together with the standard error and CI for each risk estimate) can be found at a database stored at the National Institutes of Health, publicly accessible through this link: https://CervixCa.nlm.nih.gov/RiskTables.

Footnotes

The National Cancer Institute (including M.S. and N.W.) has received cervical screening results at reduced or no cost from commercial research partners (Qiagen, Roche, BD, MobileODT, Arbor Vita) for independent evaluations of screening methods and strategies. P.E.C. has received HPV tests and assays at a reduced or no cost from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Arbor Vita Corporation, and Cepheid for research. R.S.G. reports that he was an ASCCP consultant for the guideline and a DSMB consultant for Ikonosys. The other authors have declared they have no conflicts of interest.

This study was partly supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI). NCI-Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) Persistence and Progression (PaP) study have been reapproved yearly by both KPNC and NCI Institutional Review Board review committees.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24:102–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17:S1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung LC, Egemen D, Chen X, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines: methods for risk estimation, recommended management, and validation. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24:90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castle PE, Kinney WK, Cheung LC, et al. Why does cervical cancer occur in a state-of-the-art screening program? Gynecol Oncol 2017;146:546–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katki HA, Wacholder S, Solomon D, et al. Risk estimation for the next generation of prevention programmes for cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1022–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castle PE, Solomon D, Wheeler CM, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype specificity of Hybrid Capture 2. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:2595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demarco M, Egemen D, Raine-Bennett TR, et al. A study of partial human papillomavirus genotyping in support of the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24:144–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung LC, Pan Q, Hyun N, et al. Mixture models for undiagnosed prevalent disease and interval-censored incident disease: applications to a cohort assembled from electronic health records. Stat Med 2017;36:3583–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyun N, Cheung LC, Pan Q, et al. Flexible risk prediction models for left or interval-censored data from electronic health records. Ann Appl Stat 2017;11:1063–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landy R, Cheung LC, Schiffman M, et al. Challenges in risk estimation using routinely collected clinical data: the example of estimating cervical cancer risks from electronic health-records. Prev Med 2018;111:429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]