Abstract

Psychotic patients with a lifetime history of cannabis use generally show better cognitive functioning than other psychotic patients. Some authors suggest that cannabis-using patients may have been less cognitively impaired and less socially withdrawn in their premorbid life. Using a dataset comprising 948 patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and 1313 population controls across 6 countries, we examined the extent to which IQ and both early academic (Academic Factor [AF]) and social adjustment (Social Factor [SF]) are related to the lifetime frequency of cannabis use in both patients and controls. We expected a higher IQ and a better premorbid social adjustment in psychotic patients who had ever used cannabis compared to patients without any history of use. We did not expect such differences in controls. In both patients and controls, IQ was 3 points higher among occasional-users than in never-users (mean difference [Mdiff] = 2.9, 95% CI = [1.2, 4.7]). Both cases and control daily-users had lower AF compared to occasional (Mdiff = −0.3, 95% CI = [−0.5; −0.2]) and never-users (Mdiff = −0.4, 95% CI = [−0.6; −0.2]). Finally, patient occasional (Mdiff = 0.3, 95% CI = [0.1; 0.5]) and daily-users (Mdiff = 0.4, 95% CI = [0.2; 0.6]) had better SF than their never-using counterparts. This difference was not present in controls (Fgroup*frequency(2, 2205) = 4.995, P = .007). Our findings suggest that the better premorbid social functioning of FEP with a history of cannabis use may have contributed to their likelihood to begin using cannabis, exposing them to its reported risk-increasing effects for Psychotic Disorders.

Keywords: schizophrenia, marijuana, sociability, education, cognition, preillness

Introduction

Cannabis use is well established as a risk factor for psychosis.1–3 While cannabis is known to have an acute adverse effect on cognition in healthy subjects,4,5 paradoxically, patients with psychotic disorders who report lifetime cannabis use, but not current use,6 appear to have better cognitive performance than patients who do not.7–9

Many, but not all, people with a diagnosis of psychosis show subtle cognitive and social impairments before the emergence of prodromal symptoms10–12 and some authors suggest that cannabis-using patients may constitute a phenotypically distinct group, with different neurological, cognitive, clinical, and prognostic characteristics.13 One explanation of the counterintuitive cognitive findings concerning cannabis is that those psychotic patients who use cannabis had better premorbid cognitive function than those who have not.

In the Genetics and Psychosis (GAP) study,14 we found that first-episode psychotic patients (FEP) with a history of cannabis use at any time in their life, had a higher premorbid IQ compared to other FEP patients, a difference not witnessed among controls. We proposed that cannabis use increases the risk of psychosis in a subgroup of patients with less neurodevelopmental vulnerability to the disease.7,14–19

It has been suggested that good premorbid social functioning is crucial to develop and sustain an illegal drug habit.20–22 However, there are few studies on the relationship between cannabis use and neurocognitive functioning in psychosis that controlled for premorbid functioning. One study on 104 FEP22 reported higher premorbid sociability, but not differences in premorbid IQ, in those with cannabis use before the onset compared to those without any use. Two other studies23,24 have shown that FEP with a history of cannabis use23 or cannabis use disorder24 have a better premorbid social adjustment but poorer premorbid academic adjustment and less educational attainment compared to other patients with no such history. Nonetheless, neither of these 2 studies had data on IQ.

Longitudinal studies on nonpsychotic subjects consistently showed a relationship between higher IQ in childhood and occasional or discontinued cannabis use (but not to habitual use which was linked to lower or equal IQ, compared with nonuse) probably due to the tendency of those with higher IQ to experiment with drugs.25–31

Using data from the only EUropean network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) study, we set out to examine the association between current IQ, premorbid social and academic adjustment and lifetime frequency of cannabis use in patients with a FEP disorder and a sample of population controls.

We expected a higher IQ and a better social premorbid adjustment in psychotic patients who had ever used cannabis compared to patients without any history of use. We did not expect such differences in controls.

Methods

Study Design

Data were derived from EU-GEI study (http://www.eu-gei.eu).32,33 Subjects were identified between May 01, 2010 and April 01, 2015 across centers in 5 different European countries and Brazil to examine incidence rates of psychotic disorders. We performed an extensive assessment of approximately 1000 FEP patients and 1000 population-based controls during the same period to investigate risk factors for psychosis.

Subjects

Patients.

Screening was run by skilled researchers on all potential FEP patients at their first contact with the mental health services and residents in each catchment area, who were aged 18–64 years and received a diagnosis of psychoses (ICD-10: F20–F33)34 in the study period. We excluded those with psychotic symptoms precipitated by acute intoxication (ICD-10: F1X.5), or psychosis due to another medical condition (ICD-10: F09), and those who had previously received antipsychotic medication.

Controls.

Population-based volunteers aged 18 to 64 years, who had never received treatment for psychosis, representative of each local population, were recruited through a mixture of random and quota sampling (population stratification by age, gender, and ethnicity).33,35 All the study sites received approval from their local ethical committees. All subjects signed a written consent form and data was stored anonymously.32

Measures

We used the modified version of the Medical Research Council (MRC) socio-demographic scale.36 Diagnoses, first ascertained by clinical interview, were operationalized through the 90-item computerized OPCRIT system for psychosis.37,38 The Cannabis Experience Questionnaire, further modified for the EU-GEI study (CEQEU-GEI),35 included a section from Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) on other substances of abuse, and tobacco use in the last 12 months.39

An abbreviated version of the WAIS was used in patients and controls in order to estimate full scale-IQ scores.40 Given the multisite design, we could not use a psychometric test to assess premorbid IQ, but only performed an exploratory supplementary analysis on the WAIS subtests, to examine the relation with cannabis use of the “hold” intellectual capacities.41 To assess premorbid adjustment, we used 9 scales from the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)42,43 to examine in patients and controls “the degree of achievement of developmental goals”,44–46 in 2 distinct developmental age-periods: childhood to age 11 and early adolescence (ie, 12 to age 16), so that all patients could score the same scales, regardless of their age-of-onset47,48 (further details on measures are in the supplementary material).

Statistical Analysis

In the patient/control comparisons, we used either t-test or ANCOVA and Welch test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared tests, for categorical variables, with adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for cannabis variables. Confounders were selected if they resulted associated with both patient/control status and the outcomes. Cannabis and premorbid variables were adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, and country. IQ was further corrected by education.

The frequency of cannabis use in the lifetime was reduced to 3 categories by adjusted logistic regression and codified as never use=0; occasional use=1; daily use=2. Daily use was conservatively chosen as the highest category. Never use was separated a priori as the baseline category, for theoretical reasons. Occasional-users were people who used cannabis up to “more than once a week” (supplementary table 1).

We calculated a reverse-score and extracted 2 factors from the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS), namely the Social Factor (SF) and the Academic Factor (AF), obtained by a principal-component analysis (PCA), which explained the 64.4% of the variance (supplementary material).

In order to establish differences in SF, AF, and IQ (the outcomes) related to frequency of cannabis use and patient/control group as fixed factors, we performed a MANCOVA which allowed us to take into account the correlation among these dependent variables. In the case of asymmetric distributions of the outcomes, bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) 95% CIs were calculated, using 1000 Bootstrap samples.49 Box’s M was used to test the covariance matrix. Pillai’s trace statistics tested statistical significance. Bonferroni multiplicity correction for multiple comparisons was applied. Interactions were explored in a follow-up ANCOVA for each dependent variable.

One hypothesized mechanism involving cannabis in risk of psychosis implicates dopaminergic dysregulation,50 similarly to other drugs’, such as stimulants51 and tobacco.52 Additionally, current cannabis use53 is associated with worse cognitive performance, and the effect of nicotine on neurocognition is still controversial in schizophrenia.54,55 Therefore, to ensure that the results were not biased, we ran sensitivity analyses by eliminating from the sample, alternatively and then simultaneously in any combination, all subjects (1) who used cannabis in the last 12 months (ie, current cannabis users), (2) who used tobacco in the last 12 months (ie, current tobacco users), and (3) who abused at least one illegal drug, other than cannabis, in their lifetime (ie, lifetime other drug-abusers). Figures were obtained by transforming the outcome variables into standardized scores. To account for symptomatology, which could confound results in IQ, we wanted to exploratory correct the primary analysis, by including the patients’ group only, for the negative symptoms dimension score extracted from the OPCRIT.56

We used an inverse probability weight, calculated on key demographics such as age, gender, and ethnicity, to account for controls’ under- or oversampling35 and this weight was applied to all the analyses (supplementary material). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

The sample studied comprised those 2261 subjects (948 patients and 1313 controls) from the original sample who completed at least the CEQEU-GEI and the PAS instrument (supplementary figure 1C; supplementary table 2). Patients were more often men (61.9% (587) vs 47.6% (625); χ 2(1) = 45.3) and younger than controls (mean age = 30 (10.4) vs 36.1 (13); t(2257) = −10.9). Controls were more likely to be of white ethnicity (77.3% (1015) vs 63.2% (599); χ 2(2) = 54.8) and to have achieved a university degree (38.8% (508) vs 16% (151); χ 2(3) = 222.7) than patients. Patients were more often unemployed at the time of the interview (73.8% (962) vs 42.4% (394); χ 2(1) = 225.2); they were also more likely to be single (64.1% (605) vs 30.5% (399); χ 2(2) = 272.6) or living with their parents (57.5% (539) vs 27.1% (353); χ 2(2) = 252.9) (all P < .001) (supplementary table 3).

Cannabis Use

Patients were almost twice as likely to have used cannabis in their lifetime (OR = 1.71 95% CI = [1.41; 2.07]), to have chosen high potency cannabis (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = [1.31; 2.27]) (ie, total levels of THC ≥ 10%) and to currently use cannabis (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = [1.26; 2.06]); patients were also 5 times more likely to have used cannabis on a daily basis (OR = 5.0, 95% CI = [3.75; 6.69]), compared to controls. 77.3% (464) of patients and 84.9% (535) of controls (χ 2(1) = 11.5, P = .001) who had ever used cannabis declared they started smoking cannabis socially, ie, because their friends were using it. However, patients mostly used cannabis in solitude at the time of the interview compared to controls (OR = 3.78, 95% CI = [2.69; 5.32]). Finally, patients were more than 3 times more likely to be current tobacco users (OR = 3.47, 95% CI = [2.88; 4.19]) and to have abused other drugs in their lifetime (OR = 3.43, 95% CI = [2.35; 4.99]) (supplementary table 4).

Clinical Characteristics

Compared to controls, patients had lower IQ (mean difference [Mdiff] = −17.3, 95% CI = [−18.6; −15.40]), lower SF (Mdiff −0.4, 95% CI = [−0.5; −0.3]), and AF scores (Mdiff = −0.5, 95% CI = [−0.6; −0.4]) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison Between Psychotic Patients and Controls for Social Factor (SF), Academic Factor (AF) and IQ: Estimated Marginal Mean and Partial η 2

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI)a | Partial η 2 | Estimated marginal mean (SE)b | Adjusted Mean difference (95% CI)a | Adjusted partial η 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ, N = 2087 | ||||||

| Patients | 85.28 (18.04) | −17.04 (−18.8; −15.35) | 0.178 | 80.40 (0.01) | −11.8 (−11.83; −11.77) | 0.102 |

| Controls | 102.24 (17.6) | 92.27 (0.01) | ||||

| SF, N = 2234 | ||||||

| Patients | −0.26 (1.1) | −0.44 (−0.52; −0.36) | 0.048 | 0.26 (0.47) | −0.48 (−0.57; −0.4) | 0.053 |

| Controls | 0.18 (0.87) | 0.22 (0.47) | ||||

| AF, N = 2234 | ||||||

| Patients | −0.35 (1.05) | −0.61 (−0.59; −0.53) | 0.092 | −0.37 (0.03) | −0.51 (−0.6; −0.43) | 0.060 |

| Controls | 0.25 (0.87) | 0.14 (0.03) |

Note: aConfidence intervals for the mean difference. Bonferroni adjusted and 1000 samples bootstrapped, Bias-corrected, and accelerated.

bIQ was adjusted for age, gender, education, ethnicity, and country. SF and AF were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and country.

The outcomes (SF, AF, and IQ) were weakly skewed (SF = −0.68; AF = −0.97; IQ = 0.13). SF and AF were related to IQ (Spearman’s Rho: IQ*AF = 0.439, P < .001; IQ*SF = 0.049, P < .026).

IQ and Premorbid Adjustment by Frequency of Cannabis Use in Patients and Controls

There was a significant effect of patient/control status (Pillai = 0.15, F(1, 2040) = 122.8; P < 0.001), frequency of cannabis use (Pillai = 0.03 F(2, 2040) = 13.6, P < 0.001), country (Pillai = 0.16, F(5, 2040) = 23, P < .001), gender (Pillai = 0.04, F(1, 2040) = 30.8, P < .001], age (Pillai = 0.008, F(1, 2040) = 5.5, P = 0.001), and ethnicity (Pillai = 0.11; F(2, 2040) = 42.8, P < 0.001) on IQ, SF and AF scores (Table 2). The association between the 3 outcomes and frequency of cannabis use was different in patients and controls (Pillaigroup*frequency = 0.006, F(2, 2040) = 2.17, P = .042). Follow-up analysis revealed that frequency of use had a similar effect on the IQ of patients and controls (Fgroup*frequency(2, 2062) = 0.45, P = .635). Overall, occasional-users had 3 points higher IQ, compared to never-users (Mdiff = 2.9, 95% CI = [1.2, 4.7]), but there were no differences between daily-users and both occasional (Mdiff = −2.1, 95% CI = [−4.6, 0.3]) and never-users (Mdiff = 0.8, 95% CI = [−1.7, 3.3]).

Table 2.

Relationship Between IQ, Social Factor (SF), and Academic Factor (AF) by Group and Lifetime Frequency of Cannabis Use: Pairwise comparisons obtained from the MANCOVA

| Variables | IQ | SF | AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI)a | Mean difference (95% CI)a | Mean difference (95% CI)a | |

| Group | |||

| Patients vs control | −15.11 (−16.93; −13.29) | −0.47 (−0.58; −0.37) | −0.41 (−0.51; −0.31) |

| Lifetime frequency of cannabis use | |||

| Occasional use vs never use | 3.03 (0.86; 5.2) | 0.21 (0.09; 0.33) | −0.09 (−0.21; 0.027) |

| Daily use vs never use | 0.76 (−2.19; 3.71) | 0.28 (0.12; 0.45) | −0.43 (−0.59; −0.26) |

| Sex | |||

| Female vs male | −3.7 (−5.18; −2.23) | 0.004 (0.08; −0.07) | 0.24 (0.16; 0.33) |

| Age | −0.08 (−0.08; −0.08) | −0.004 (−0.004; −0.004) | −0.002 (−0.002; −0.001) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black vs white | −17.99 (−20.81; −15.17) | 0.18 (0.3; 0.34) | −0.24 (−0.4; −0.08) |

| Other vs white | −7.91 (−10.32; −5.5) | 0.07 (0.21; −0.05) | −0.005 (−0.14; −0.13) |

| Country | |||

| Holland vs United Kingdom | −2.93 (−0.54; 6.41) | 0.02 (−0.17; 0.21) | 0.01 (−0.17; 0.21) |

| Spain vs United Kingdom | −10.96 (−7.37; −14.55) | 0.4 (0.2; 0.6) | −0.38 (−0.58; −0.17) |

| France vs United Kingdom | −12.42 (−8.25; −16.59) | 0.19 (−0.04; 0.42) | −0.28 (−0.51; −0.04) |

| Italy vs United Kingdom | −4.53 (−0.39; −8.78) | 0.36 (0.13; 0.59) | −0.23 (−0.46; −0.001) |

| Brazil vs United Kingdom | −3.25 (0.21; 6.71) | 0.83 (0.63; 1.02) | −0.13 (−0.33; 0.05) |

| Group*lifetime frequency of cannabis useb | |||

| Patients | |||

| Never use vs occasional use | −3.5 (−6.48; −0.21) | −0.33 (−0.51; −0.14) | 0.08 (−0.06; 0.24) |

| Never use vs daily use | −1.89 (−5.04; 1.8) | −0.48 (−0.66; −0.3) | 0.34 (0.17; 0.52) |

| Occasional use vs daily use | 1.61 (−1.41; 4.68) | −0.15 (−0.31; 0.004) | 0.26 (0.1; 0.43) |

| Controls | |||

| Never use vs occasional use | −2.47 (−4.79; −0.26) | −0.1 (−0.22; 0.04) | 0.11 (−0.001; 0.21) |

| Never use vs daily use | 0.21 (−3.79; 4.29) | −0.14 (−0.38; 0.12) | 0.54 (0.25; 0.82) |

| Occasional use vs daily use | 2.68 (−1.49; 6.94) | −0.03 (−0.26; 0.22) | 0.43 (0.11; 0.73) |

Note: aCIs for mean difference. Bonferroni adjusted and 1000 samples bootstrapped, Bias-corrected, and accelerated.

bPairwise Comparisons resulting from ANCOVAs to explore interactions.

On the other hand, patients and controls who were daily cannabis users were very similar to each other regarding AF (Mdiff = −0.2, 95% CI = [−0.6; 0.003]) and they both had lower scores, as compared to their respective occasional (Mdiff = −0.3, 95% CI = [−0.5; −0.2]) and never-using counterparts (Mdiff = −0.4, 95% CI = [−0.6; −0.2]) (Fgroup*frequency(2, 2205) = 1.22, P = .295).

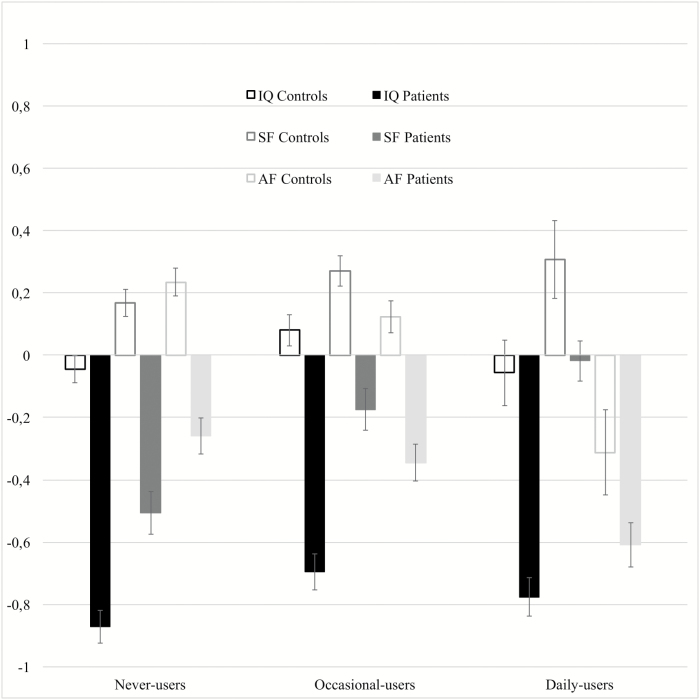

Regarding SF, we found a significant interaction effect (Fgroup*frequency(2, 2205) = 4.99, P = .007): SF was better in patients who were occasional (Mdiff = 0.3, 95% CI = [0.1; 0.5]) or daily-users (Mdiff = 0.4, 95% CI = [0.2; 0.6]), compared to never-user patients, while there was no effect of cannabis use on SF in controls (table 2, figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Standardized scores (estimated marginal means and standard errors) of IQ, Academic Factor (AF) and Social Factor (SF) by frequency of cannabis use in patients and controls.

The results concerning the patient group stayed consistent once corrected for negative symptoms (Pillaifrequency = 0.052, F(6, 1542) = 6.84, P < .001) (supplementary table 5).

Sensitivity Analysis

We identified (1) 209 FEP and 146 controls who were current cannabis users; (2) 515 FEP and 311 controls who were current tobacco users; (3) 120 FEP and 37 controls who were lifetime other drug-abusers (supplementary table 2). When these subjects were removed, in any combination, the results were consistent with the primary analysis. The most interesting result was revealed when all previous categories were simultaneously removed. This final sample comprised of 382 patients and 921 controls. We found a significant interaction effect on IQ (Fgroup*frequency(2, 1208) = 4.42, P = .012). Patients who were occasional-users (N = 97; mean IQ = 87.6, SE = 1.8) had 8 points higher IQ (Mdiff = 8.3, 95% CI = [4.2; 12.7]) than never-user patients (N = 249; mean IQ = 79.3, SE = 1.1), while in controls we only found a 3 points difference (Mdiff = 2.8, 95% CI = [0.07; 5.6]) between occasional (N = 302, mean IQ = 98.7, SD = 1.1) and never-users (N = 584; mean = 95.8, SE = 0.8).

In line with the original analysis, AF was similarly related to cannabis use in patients and in controls (Fgroup*frequency(2, 1272) = 0.93, P = .392). Both patients and control daily-users had lower scores than never- (Mdiff=−0.5, 95% CI = [−0.8; −0.2]) and occasional-users (Mdiff = −0.5, 95% CI = [−0.8; −0.1]), but difference with occasional-users was more significant for controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analysis: Pairwise Comparisons Resulting From Follow-up ANCOVAs to Explore Interactions

| Group | Dependent variable | Cannabis Frequency | Mean difference | SE | P value | 95% CIdiff | BCaa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | IQ | Never | Occasional use | −8.32* | 2.13 | .001 | −12.54 | −4.3 |

| Daily use | −7.1 | 3.73 | .364 | −4.68 | 11.6 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | 1.21 | 3.93 | .124 | −2.58 | 14.9 | ||

| SF | Never | Occasional use | −0.29 | 0.14 | .046 | −0.57 | 0.001 | |

| Daily use | −0.78* | 0.18 | .001 | −1.12 | −0.37 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | −0.48* | 0.2 | .019 | −0.89 | −0.05 | ||

| AF | Never | Occasional use | −0.01 | 0.11 | .923 | −0.24 | 0.23 | |

| Daily use | 0.39 | 0.22 | .067 | 0.008 | 0.79 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | 0.4 | 0.23 | .080 | −0.01 | 0.82 | ||

| Controls | IQ | Never | Occasional use | −2.88* | 1.39 | .048 | −5.62 | −0.1 |

| Daily use | 3.86 | 4.41 | .364 | −4.68 | 11.6 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | 6.74 | 4.57 | .124 | −2.58 | 14.9 | ||

| SF | Never | Occasional use | −0.06 | 0.06 | .322 | −0.18 | 0.04 | |

| Daily use | 0.15 | 0.24 | .521 | −0.28 | 0.65 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | 0.22 | 0.24 | .367 | −0.22 | 0.73 | ||

| AF | Never | Occasional use | 0.07 | 0.06 | .244 | −0.04 | 0.20 | |

| Daily use | 0.71* | 0.18 | .001 | 0.28 | 1.07 | |||

| Occasional use | Daily use | 0.63* | 0.18 | .002 | 0.22 | 0.97 |

Note: aCIs for the mean difference. Bonferroni adjusted and 1000 samples bootstrapped, Bias-corrected, and accelerated.

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

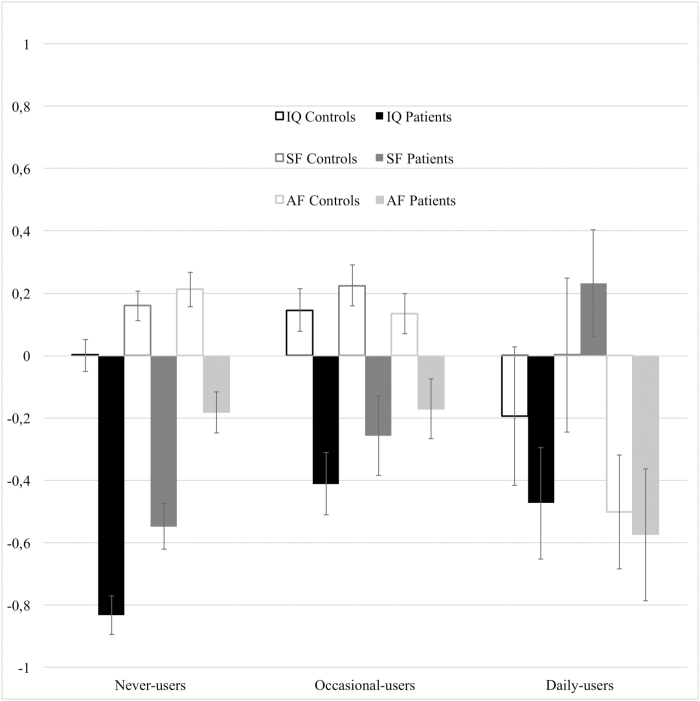

Regarding SF, we replicated the interaction effect of frequency of cannabis use in patients, but not in controls (Fgroup*frequency(2, 1272) = 6.75, P = .001): patients who were occasional (Mdiff = 0.2, 95% CI = [0.006; 0.5]) or daily-users (Mdiff = 0.7, 95% CI = [0.3; 1.1]) had higher scores than never-user patients, and daily-users scored better than occasional-users (Mdiff = 0.4, 95% CI = [0.05; 0.8]). Furthermore, patients who were daily-users had (1) similar IQ (Mdiff = −5.5, 95% CI = [−17.1, 4.2]) and AF (Mdiff = −0.07, 95% CI = [−0.6; 0.4]) compared to daily-user controls; and (2) they had very similar or even better mean scores of SF (mean = 0.2, 95% CI = [−0.1; 0.5]) than control daily- (mean = 0.3, 95% CI = [0.03; 0.5]), occasional (mean = 0.2, 95% CI = [0.1; 0.3]), and never-users (mean = 0.1, 95% CI = [0.07; 0.2]) (table 3, figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity analysis. Standardized scores (estimated marginal means and standard errors) of IQ, Academic Factor (AF) and Social Factor (SF) by frequency of cannabis use in patients and controls.

Discussion

Summary of Main Results

Our first main finding indicated higher IQ in the cannabis occasional-using subgroup of patients compared with their never-user counterparts, and a similar effect in controls. Early academic adjustment (AF) was lower when the frequency of cannabis use increased, in both patients and controls. Finally, patients with a history of occasional or daily cannabis use had been less socially withdrawn (ie, had higher SF scores) compared to those psychotic patients who never used cannabis, a difference that was not seen within controls.

Comparison With Previous Literature

All differences between patients and controls, in terms of socio-demographics,57–59 IQ,60–62 and premorbid conditions63,64 were expected as the control group was selected to be representative of the general population of each area and not to be matched with the case group. We also confirmed the expected differences between patients and controls in patterns of cannabis use.24,35,65–67

Regarding IQ, we confirmed that cannabis-using patients have higher IQ than never-users and showed that this effect is attributable to occasional cannabis users, who represent the biggest proportion of users.68 In contrast to previous research with a similar design,69 our results remained consistent after controlling for several confounders and the sensitivity analysis revealed an IQ more than 8 points higher in occasional-using patients than in never-users, a much greater effect than the 3-point difference detected among controls (see also70,71). To date, this is the first study that (1) included a control group in exploring this effect and (2) found a higher IQ in cannabis occasional-using population controls. These findings differ from the Dunedin study, which identified an IQ decline in cannabis users but this latter was over several decades of adult life.72 Nevertheless, in the Dunedin study, those who reported lifetime use of cannabis, but not dependence, were cognitively spared, while in currently dependent people cognition declined.72 The descriptive differences we found between daily- and occasional-user controls indicate a higher academic achievement and a later contact with the substance in the latter, which could have prevented them from dependence and related academic failure, thus influencing future IQ. However, education was not sufficient to account for the differences in IQ, according to frequency of cannabis use, in our analysis, when it was inserted to adjust comparisons. This is not surprising, as we know that IQ scores are multi-determined and partially hereditary,73 and therefore probably differently related to premorbid IQ accordingly to patterns of cannabis use, as suggested in longitudinal studies of nonpsychotic subjects.25–31 Additionally, there are recent hints that IQ in psychosis is associated with the polygenic risk score (PRS) that indexes cognition in the general population and is partly independent from PRS predisposing to schizophrenia74; this could corroborate our finding of a similar relationship of IQ with cannabis use in patients and controls.

Those patients and controls who used cannabis, especially daily-users, had shown lower AF. A recent longitudinal study conducted in the United Kingdom on a representative cohort of pupils showed that high childhood academic adjustment at age 11 increased the risk of both occasional and persistent cannabis use in late adolescence (19–20 years).75 Our study embraces different countries, and the results are in line with those from other studies with nonpsychotic people, which indicated that poor school performance was a common antecedent of cannabis and other substance use, regardless of IQ, with the odds of dropping out from school increasing with the frequency of use.76–79 Similar mechanisms are probably implicated in determining AF in patients.

Finally, we found that patients, but not controls who were cannabis users, particularly daily-users, had shown better SF than their non-using counterparts. This was even more evident when lifetime abusers of other drugs, current cannabis users, and current tobacco users were removed from the model, and daily-users scored similarly or even better than controls in SF scores.

We want to highlight here, that the confidence intervals in IQ, SF, and AF scores, in the sensitivity analysis, increased in patients who used cannabis occasionally or daily, compared to never-users; this higher variability is present also in control daily-users, compared to the other 2 groups. This may suggest a higher intragroup variability in cognition and premorbid functioning or it could, of course, be due to the small numbers, which can additionally mask the differences between patients and control daily-users, at least regarding the 5-point mean difference in IQ.

The majority of studies that explored premorbid functioning in psychotic patients selected current or recent daily-users and compared them with nonusers, revealing worse academic functioning in the former,23,24,53 conceptually in line with our results on lifetime daily-users. Other studies found no association between premorbid function and drug or cannabis abuse,80–82 probably because they used total PAS mean scores; therefore, inverse results in social and academic factors, related to cannabis use, could have nullified each other. Some authors used a different methodology, focusing on recent cannabis use, and did not find any relationships with premorbid sociability,83,84 but better current social cognition in recent cannabis-abusers.83 This last result was not replicated in a recent study, which looked at lifetime cannabis use in relation to current social cognition. However, as the authors state, it is possible that subjects with psychosis and cannabis use had higher levels of premorbid social cognition, responsible for the contact with the substance, which then decreased after the diagnosis.85

What Can We Speculate About Premorbid Predisposition to Psychosis Related to Cannabis Use?

Cannabis use is probably first self-selected, depending on predisposing factors, such as higher early sociability, and later reinforced, in some patients, in a pattern of abuse; this involves the subject in a less challenging world (eg, dropping out from school86–89), that contributes to lower the future IQ. This latter does not happen in occasional-users whose IQ is more representative of their premorbid cognition14 (see also exploratory analysis on the WAIS subtest—supplementary material).

The early neuropsychological and social deficits (ie, lower IQ and SF) of non-using patients evoke a more “classical” profile of people at-risk to develop psychosis,90 in line with the neurodevelopmental hypothesis.10,91,92 Non-using patients and controls had higher AF before their 16th year, compared with cannabis users. While this result is intuitive in controls, it apparently contradicts the expectation of a greater impairment in this group of neurodevelopmentally impaired psychotic individuals. Previous results showed that premorbid academic adjustment in psychosis is impaired and further declines from childhood to late adolescence.93,94 These studies reported the most significant deterioration between 16 and 18 years (late adolescence), while our PAS measures stop at age 16 (early adolescence) (see Supplementary Material for further details). Interestingly, one of them93 reported a greater premorbid academic decline in those with less premorbid social impairment, whom they defined “non-deficit” schizophrenic patients, similarly to our results; however, they did not account for cannabis use.

Strengths and Limitations

The EU-GEI study has strengths, such as the large sample size and the use of samples from several countries. Even if a prospective cohort study would be able to provide the most robust design for establishing causal connections, such a design is problematic, because psychosis is a rare disorder, with a large time lag between the occurrence of environmental adversities and the onset.

The quota sampling strategy to obtain controls with characteristics of each of the study catchment areas’ population at risk allowed us to have a more representative control sample, as compared to previous studies and suggests that the prevalence of patterns of cannabis use in our controls represent those of the local population.35 Sensitivity supplementary analysis revealed the appropriateness of this strategy for the outcomes measured because selection bias was unlikely to explain our findings (supplementary material).

The higher IQ in occasional cannabis-using controls could be identified thanks to the large sample across different countries. People with psychotic disorders might be more likely to recall risk factors95 and, for example, could recall greater disadvantages in their early life in PAS or to have used drugs in CEQ interview. However, the interviews were completed by at least one corroborative source of information (eg, family, clinical notes, other clinicians), and the validity of self-report at the PAS has been supported in persons with schizophrenia.96 Unlike present use, a history of lifetime use of cannabis cannot be assessed by a biological test. Results from our previous study suggest that the accuracy of self-reported data on cannabis use is high.67

Finally, family history for psychosis could be associated with the relationship between cognition and cannabis use in patients.97 However, no substantial difference in PRS for schizophrenia was found in the GAP study between FEP cannabis users and nonusers.98

Implications

Those patients who use cannabis daily, and only cannabis, in their lifetime were very similar to daily-using controls regarding IQ, early sociability and academic adjustment. Thus we can speculate that cannabis could have had a role in their psychosis onset, acting as a crucial risk factor, and in a greater proportion than in patients who were occasional-users.35

This evidence, coupled with recent confirmations about the strong link between cannabis daily use and increased risk for psychosis,35 further supports the need to improve primary prevention in the general population, and suggests that future studies should look at those factors that make the difference between cannabis daily-using subjects that develop psychosis and those who do not.

Conclusions

The study confirms that patients with FEP who used cannabis occasionally have higher IQ than never-using patients. The findings also demonstrate that both occasional and daily cannabis-using patients have better premorbid sociability than non-using patients and that this difference is not present among controls. Our findings are compatible with the view that the better premorbid social adjustment of cannabis-using patients may have contributed to their early contact with the substance, and that cannabis use increases the risk of psychosis in a subgroup of patients with less neurodevelopmental vulnerability for psychosis.

Funding

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) Project is funded by grant agreement HEALTH-F2-2010–241909 (Project EU-GEI) from the Seventh Framework Programme. The project was further funded by the National Institute for Health Research, at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Kings College London. M.D.F. was supported by Medical Research Council (Clinician Scientist Fellowship - project reference MR/M008436/1) Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Sir Henry Dale Felloship, grant n. 101272/Z/13/Z) granted J.B.K.; The Brazilian study was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (grant n. 2012/0417-0); E.V. was supported by the Seaver Foundation, NY; she is a Seaver Faculty Scholar; H.J. and P.B.J. were funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care East of England. The funders contributed to the salaries of the researchers involved, but they did not contribute in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgment to all the patients and the EU-GEI team, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College (London) and the University of Palermo that supported this work. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Contributor Information

WP2 EU-GEI GROUP:

Silvia Amoretti, Grégoire Baudin, Stephanie Beards, Domenico Berardi, Chiara Bonetto, Bibiana Cabrera, Angel Carracedo, Thomas Charpeaud, Javier Costas, Doriana Cristofalo, Pedro Cuadrado, Aziz Ferchiou, Nathalie Franke, Flora Frijda, Enrique García Bernardo, Paz Garcia-Portilla, Javier González Peñas, Emiliano González, Kathryn Hubbard, Stéphane Jamain, Estela Jiménez-López, Antonio Lasalvia, Marion Leboyer, Gonzalo López Montoya, Esther Lorente-Rovira, Covadonga M Díaz-Caneja, Camila Marcelino Loureiro, Giovanna Marrazzo, Covadonga Martínez, Mario Matteis, Elles Messchaart, Ma Dolores Moltó, Carmen Moreno, Nacher Juan, Ma Soledad Olmeda, Mara Parellada, Baptiste Pignon, Marta Rapado, Jean-Romain Richard, José Juan Rodríguez Solano, Paulo Rossi Menezes, Mirella Ruggeri, Pilar A Sáiz, Teresa Sánchez-Gutierrez, Emilio Sánchez, Crocettarachele Sartorio, Franck Schürhoff, Fabio Seminerio, Rosana Shuhama, Simona A Stilo, Fabian Termorshuizen, Sarah Tosato, Anne-Marie Tronche, Daniella van Dam, and Elsje van der Ven

GROUP INFORMATION:

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) WP2 Group members includes:

Amoretti, Silvia Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, CIBERSAM, Spain;

Baudin, Grégoire MSc, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier “Mondor,” Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France;

Beards, Stephanie, PhD, Department of Health Service and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England;

Berardi, Domenico Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Psychiatry Unit, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Viale Pepoli 5, 40126 Bologna, Italy;

Bonetto, Chiara PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy;

Cabrera, Bibiana MSc, PhD, Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, CIBERSAM, Spain;

Carracedo, Angel MD, PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain;

Charpeaud, Thomas, MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France;

Costas, Javier PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain;

Cristofalo, Doriana MA, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy;

Cuadrado, Pedro, MD, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Centre, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Madrid, Spain;

Ferchiou, Aziz MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier “Mondor”, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France;

Franke, Nathalie, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands;

Frijda, Flora MSc, Etablissement Public de Santé Maison Blanche, Paris, France;

García Bernardo, Enrique MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital GeneralUniversitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Garcia-Portilla, Paz, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine, Psychiatry Area, School of Medicine, Universidad de Oviedo, ISPA, INEUROPA, CIBERSAM, Oviedo, Spain;

González Peñas, Javier Hospital Gregorio Marañón, IiSGM, School of Medicine, Calle Dr Esquerdo, 46, Madrid 28007, Spain;

González, Emiliano PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Hubbard, Kathryn Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London;

Jamain, Stéphane, PhD, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France;

Jiménez-López, Estela MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Servicio de Psiquiatría Hospital “Virgen de la Luz,” Cuenca, Spain;

Lasalvia, Antonio Section of Psychiatry, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona, Verona, Italy;

Leboyer, Marion, MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier “Mondor,” Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France;

López Montoya, Gonzalo PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Lorente-Rovira, Esther PhD, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, CIBERSAM, Valencia, Spain;

M Díaz-Caneja, Covadonga Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain.

Marcelino Loureiro, Camila MD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil;

Marrazzo, Giovanna MD, PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, “P. Giaccone” General Hospital, Palermo, Italy;

Martínez, Covadonga MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain;

Matteis, Mario, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Messchaart, Elles MSc, Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands;

Moltó, Ma Dolores, Department of Genetics, University of Valencia, Campus of Burjassot, Biomedical Research Institute INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain, Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain

Moreno, Carmen MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Nacher Juan, Neurobiology Unit, Department of Cell Biology, Interdisciplinary Research Structure for Biotechnology and Biomedicine (BIOTECMED), Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM): Spanish National Network for Research in Mental Health, Madrid, Spain, Fundación Investigación Hospital Clínico de Valencia, INCLIVA, Valencia, Spain.

Olmeda, Ma Soledad Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain;

Parellada, Mara MD, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Pignon, Baptiste MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier “Mondor,” Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France;

Rapado, Marta, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Richard, Jean-Romain MSc, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France;

Rodríguez Solano, José Juan MD, Puente de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Centro de Salud Mental Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, Spain;

Rossi Menezes, Paulo, Population Mental Health Center, University of São Paulo, Brazil, Department of Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, Brazil;

Ruggeri, Mirella, MD, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy;

Sáiz, Pilar A, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Oviedo,CIBERSAM. Instituto de Neurociencias del Principado de Asturias, INEUROPA, Oviedo, Spain; Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA), Oviedo, Spain;

Sánchez-Gutierrez, Teresa, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM, CIBERSAM, C/Doctor Esquerdo 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain. Faculty of Health Science. Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR), Madrid, Spain

Sánchez, Emilio MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, IiSGM (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain;

Sartorio, Crocettarachele PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, “P. Giaccone” General Hospital, Palermo, Italy;

Schürhoff, Franck MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier “Mondor,” Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France;

Seminerio, Fabio PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, “P. Giaccone” General Hospital, Palermo, Italy;

Shuhama, Rosana, PhD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil;

Stilo, Simona A, MSc, Department of Health Service and Population Research, and Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England;

Termorshuizen, Fabian PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands;

Tosato, Sarah, MD, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy;

Tronche, Anne-Marie MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France;

van Dam, Daniella PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands;

van der Ven, Elsje PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands.

References

- 1. Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. Association between cannabis and psychosis: epidemiologic evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Potvin S, Amar MB. Review: cannabis use increases the risk of psychotic outcomes. Evid Based Ment Health. 2008;11(1):28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grant I, Gonzalez R, Carey CL, Natarajan L, Wolfson T. Non-acute (residual) neurocognitive effects of cannabis use: a meta-analytic study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(5):679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schreiner AM, Dunn ME. Residual effects of cannabis use on neurocognitive performance after prolonged abstinence: a meta-analysis. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20(5):420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bogaty SER, Lee RSC, Hickie IB, Hermens DF. Meta-analysis of neurocognition in young psychosis patients with current cannabis use. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;99:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yücel M, Bora E, Lubman DI, et al. The impact of cannabis use on cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of existing findings and new data in a first-episode sample. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(2):316–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabin RA, Zakzanis KK, George TP. The effects of cannabis use on neurocognition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;128(1-3):111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Potvin S, Joyal CC, Pelletier J, Stip E. Contradictory cognitive capacities among substance-abusing patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1-3):242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howes OD, Murray RM. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet. 2014;383(9929):1677–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neumann CS, Grimes K, Walker EF, Baum K. Developmental pathways to schizophrenia: behavioral subtypes. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104(4):558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGlashan TH. Premorbid adjustment, onset types, and prognostic scaling: still informative? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sami MB, Bhattacharyya S. Are cannabis-using and non-using patients different groups? Towards understanding the neurobiology of cannabis use in psychotic disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(8):825–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferraro L, Russo M, O’Connor J, et al. Cannabis users have higher premorbid IQ than other patients with first onset psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de la Serna E, Mayoral M, Baeza I, et al. Cognitive functioning in children and adolescents in their first episode of psychosis: differences between previous cannabis users and nonusers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(2):159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leeson VC, Harrison I, Ron M, Barnes T, Joyce E. The effect of cannabis use and cognitive reserve on age at onset and psychosis outcomes in first-episode Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;38(4):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Løberg EM, Hugdahl K. Cannabis use and cognition in schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2009;3:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schnell T, Koethe D, Daumann J, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. The role of cannabis in cognitive functioning of patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schnell T, Kleiman A, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Daumann J, Becker B. Increased gray matter density in patients with schizophrenia and cannabis use: a voxel-based morphometric study using DARTEL. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2-3):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joyal CC, Hallé P, Lapierre D, Hodgins S. Drug abuse and/or dependence and better neuropsychological performance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;63(3):297–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stirling J, Lewis S, Hopkins R, White C. Cannabis use prior to first onset psychosis predicts spared neurocognition at 10-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2005;75(1):135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodríguez-Sánchez JM, Ayesa-Arriola R, Mata I, et al. Cannabis use and cognitive functioning in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2010;124(1–3):142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Compton MT, Broussard B, Ramsay CE, Stewart T. Pre-illness cannabis use and the early course of nonaffective psychotic disorders: associations with premorbid functioning, the prodrome, and mode of onset of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1–3):71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sevy S, Robinson DG, Napolitano B, et al. Are cannabis use disorders associated with an earlier age at onset of psychosis? A study in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferraro L, Sideli L, La Barbera D. Cannabis users and premorbid intellectual quotient. In: Preedy VR, ed. Handbook of Cannabis and Related Pathologies: Biology, Pharmacology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2017:223-233. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Fothergill KE. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of substance use in adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97(7):833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fleming JP, Kellam SG, Brown CH. Early predictors of age at first use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1982;9(4):285–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kellam SG, Ensminger ME, Simon MB. Mental health in first grade and teenage drug, alcohol, and cigarette use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1980;5(4):273–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White JW, Gale CR, Batty GD. Intelligence quotient in childhood and the risk of illegal drug use in middle-age: the 1958 National Child Development Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(9):654-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. White J, Mortensen LH, Batty GD. Cognitive ability in early adulthood as a predictor of habitual drug use during later military service and civilian life: the Vietnam Experience Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1-2):164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fried P, Watkinson B, James D, Gray R. Current and former marijuana use: preliminary findings of a longitudinal study of effects on IQ in young adults. CMAJ. 2002;166(7):887–891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. European Network of National Networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia (EU-GEI), van Os J, Rutten BP, et al. Identifying gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: contemporary challenges for integrated, large-scale investigations. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(4):729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jongsma HE, Gayer-Anderson C, Lasalvia A, et al. Treated incidence of psychotic disorders in the multinational EU-GEI Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Forti M, Quattrone D, Freeman TP, et al. The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe: the EUGEI case-control study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(5):427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mallett R, Leff J, Bhugra D, Pang D, Zhao JH. Social environment, ethnicity and schizophrenia. A case-control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(7):329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I. A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(8):764–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams J, Farmer AE, Ackenheil M, Kaufmann CA, McGuffin P, Group TORR. A multicentre inter-rater reliability study using the OPCRIT computerized diagnostic system. Psychol Med. 1996;26(4):775-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kishore J, Kapoor V, Reddaiah VP. The composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): its reliability and applicability in a rural community of northern India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41(4):350–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Velthorst E, Levine SZ, Henquet C, et al. To cut a short test even shorter: reliability and validity of a brief assessment of intellectual ability in schizophrenia–a control-case family study. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2013;18(6):574–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wechsler D. WAIS-R: Manual : Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8(3):470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Brill N, Bromet EJ. The premorbid adjustment scale structured interview (PAS-SI): preliminary findings. Schizophr Res. 2007;90(1-3):255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shapiro DI, Marenco S, Spoor EH, Egan MF, Weinberger DR, Gold JM. The Premorbid Adjustment Scale as a measure of developmental compromise in patients with schizophrenia and their healthy siblings. Schizophr Res. 2009;112(1–3):136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cuesta MJ, Sánchez-Torres AM, Cabrera B, et al. ; PEPs Group Premorbid adjustment and clinical correlates of cognitive impairment in first-episode psychosis. The PEPsCog Study. Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1–3):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morcillo C, Stochl J, Russo DA, et al. First-rank symptoms and premorbid adjustment in young individuals at increased risk of developing psychosis. Psychopathology. 2015;48(2):120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rabinowitz J, De Smedt G, Harvey PD, Davidson M. Relationship between premorbid functioning and symptom severity as assessed at first episode of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2021–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Mastrigt S, Addington J. Assessment of premorbid function in first-episode schizophrenia: modifications to the Premorbid Adjustment Scale. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(2):92–101. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11944510. Accessed May 9, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carpenter J, Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19(9):1141–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Murray RM, Englund A, Abi-Dargham A, et al. Cannabis-associated psychosis: neural substrate and clinical impact. Neuropharmacology. 2017;124:89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boileau I, Dagher A, Leyton M, et al. Conditioned dopamine release in humans: a positron emission tomography [11C]raclopride study with amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2007;27(15):3998–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leroy C, Karila L, Martinot JL, et al. Striatal and extrastriatal dopamine transporter in cannabis and tobacco addiction: a high-resolution PET study. Addict Biol. 2012;17(6):981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ringen PA, Melle I, Berg AO, et al. Cannabis use and premorbid functioning as predictors of poorer neurocognition in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Res. 2013;143(1):84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vermeulen JM, Schirmbeck F, Blankers M, et al. ; Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP) investigators Association between smoking behavior and cognitive functioning in patients with psychosis, siblings, and healthy control subjects: results from a prospective 6-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(11):1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mackowick KM, Barr MS, Wing VC, Rabin RA, Ouellet-Plamondon C, George TP. Neurocognitive endophenotypes in schizophrenia: modulation by nicotinic receptor systems. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Quattrone D, Di Forti M, Gayer-Anderson C, et al. Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychopathology at first episode psychosis: findings from the multinational EU-GEI study. Psychol Med. 2019;49(8):1378–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D. A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Med. 2004;2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stilo SA, Di Forti M, Mondelli V, et al. Social disadvantage: cause or consequence of impending psychosis? Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mohamed S, Paulsen JS, O’Leary D, Arndt S, Andreasen N. Generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a study of first-episode patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(8):749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zanelli J, Reichenberg A, Morgan K, et al. Specific and generalized neuropsychological deficits: a comparison of patients with various first-episode psychosis presentations. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Laurens KR, Carr VJ. A systematic meta-review grading the evidence for non-genetic risk factors and putative antecedents of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;133(1–3):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hans SL, Marcus J, Henson L, Auerbach JG, Mirsky AF. Interpersonal behavior of children at risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 1992;55(4):314–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cannon M, Walsh E, Hollis C, et al. Predictors of later schizophrenia and affective psychosis among attendees at a child psychiatry department. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Donoghue K, Doody GA, Murray RM, et al. Cannabis use, gender and age of onset of schizophrenia: data from the ÆSOP study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(3):528–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Larsen TK, Melle I, Auestad B, et al. Substance abuse in first-episode non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006;88(1–3):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Di Forti M, Morgan C, Dazzan P, et al. High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):488–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Myles H, Myles N, Large M. Cannabis use in first episode psychosis: meta-analysis of prevalence, and the time course of initiation and continued use. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(3):208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Power BD, Dragovic M, Badcock JC, et al. No additive effect of cannabis on cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1–2):245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Núñez C, Ochoa S, Huerta-Ramos E, et al. ; GENIPE Group Cannabis use and cognitive function in first episode psychosis: differential effect of heavy use. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(5):809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schnakenberg Martin AM, Bonfils KA, Davis BJ, Smith EA, Schuder K, Lysaker PH. Compared to high and low cannabis use, moderate use is associated with fewer cognitive deficits in psychosis. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2016;6:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):E2657–E2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Plomin R, von Stumm S. The new genetics of intelligence. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(3):148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Richards AL, Pardiñas AF, Frizzati A, et al. The relationship between polygenic risk scores and cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(2):336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Williams J, Hagger-Johnson G. Childhood academic ability in relation to cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use from adolescence into early adulthood: longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE). BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kandel DB. Longitudinal Research on Drug Use. Empirical Findings and Methodologocal Issues. New York, NY: Hemisphere Publishing Corp; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Legleye S, Obradovic I, Janssen E, Spilka S, Le Nézet O, Beck F. Influence of cannabis use trajectories, grade repetition and family background on the school-dropout rate at the age of 17 years in France. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(2):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Apantaku-Olajide T, James PD, Smyth BP. Association of educational attainment and adolescent substance use disorder in a clinical sample. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2014;23(3):169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lee CY, Winters KC, Wall MM. Trajectories of substance use disorders in youth: identifying and predicting group memberships. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2010;19(2):135–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Van Mastrigt S, Addington J, Addington D. Substance misuse at presentation to an early psychosis program. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(1):69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, Carlson G, Kovasznay B, Schwartz JE. Prevalence and severity of substance use disorders and onset of psychosis in first-admission psychotic patients. Psychol Med. 1998;28(6):1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. González-Blanch C, Gleeson JF, Koval P, Cotton SM, McGorry PD, Alvarez-Jimenez M. Social functioning trajectories of young first-episode psychosis patients with and without cannabis misuse: a 30-month follow-up study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. González-Pinto A, Alberich S, Barbeito S, et al. Cannabis and first-episode psychosis: different long-term outcomes depending on continued or discontinued use. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Arnold C, Allott K, Farhall J, Killackey E, Cotton S. Neurocognitive and social cognitive predictors of cannabis use in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1-2):231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Helle S, Løberg EM, Gjestad R, Schnakenberg Martin AM, Lysaker PH. The positive link between executive function and lifetime cannabis use in schizophrenia is not explained by current levels of superior social cognition. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Cannabis and educational achievement. Addiction. 2003;98(12):1681–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The short-term consequences of early onset cannabis use. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24(4):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early onset cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in young adults. Addiction. 1997;92(3):279–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rogeberg O. Correlations between cannabis use and IQ change in the Dunedin cohort are consistent with confounding from socioeconomic status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(11):4251–4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Di Forti M, Morrison PD, Butt A, Murray RM. Cannabis use and psychiatric and cogitive disorders: the chicken or the egg? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Murray RM, O’Callaghan E, Castle DJ, Lewis SW. A neurodevelopmental approach to the classification of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18(2):319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Murray RM, Lewis SW. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295(6600):681–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Strauss GP, Allen DN, Miski P, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Carpenter WT Jr. Differential patterns of premorbid social and academic deterioration in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;135(1–3):134–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Allen DN, Strauss GP, Barchard KA, Vertinski M, Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW. Differences in developmental changes in academic and social premorbid adjustment between males and females with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1–3):132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Greenland S. Interactions in epidemiology: relevance, identification, and estimation. Epidemiology. 2009;20(1):14–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Brill N, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J. Validity of the premorbid adjustment scale. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):981–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. González-Pinto A, González-Ortega I, Alberich S, et al. Opposite cannabis-cognition associations in psychotic patients depending on family history. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Di Forti M, Vassos E, Lynskey M, Craig M, Murray RM. Cannabis and psychosis - Authors’ reply. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(5):382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.