Abstract

Through a close reading of texts, this essay traces the development of catatonia from its origination in Kahlbaum’s 1874 monograph to Kraepelin’s catatonic subtype of his new category of Dementia Praecox (DP) in 1899. In addition to Kraepelin’s second to sixth textbook editions, I examine the six articles referenced by Kraepelin: Kahlbaum 1874, Brosius 1877, Neisser 1887, Behr 1891, Schüle 1897, and Aschaffenburg 1897 (Behr and Aschaffenburg worked under Kraepelin). While Brosius and Neisser confirmed Kahlbaum’s descriptions, Behr, Schüle, and Aschaffenburg concluded that his catatonic syndrome was nonspecific and only more narrowly defined forms, especially those with deteriorating course, might be diagnostically valid. Catatonia is first described by Kraepelin as a subform of Verrücktheit (chronic nonaffective delusional insanity) in his second to fourth editions. In his third edition, he adds a catatonic form of Wahnsinn (acute delusional-affective insanity). His fourth and fifth editions contain, respectively, catatonic forms of his two proto-DP concepts: Psychischen Entartungsprocesse and Die Verblödungsprocesse. Kahlbaum’s catatonia required a sequential phasic course. Positive psychotic symptoms were rarely noted, and outcome was frequently good. While agreeing on the importance of key catatonic signs (stupor, muteness, posturing, verbigeration, and excitement), Kraepelin narrowed Kahlbaum’s concept, dropping the phasic course, emphasizing positive psychotic symptoms and poor outcome. In his fourth to sixth editions, as he tried to integrate his three DP subtypes, he stressed, as suggested by Aschaffenburg and Schüle, the close clinical relationship between catatonia and hebephrenia and emphasized the bizarre and passivity delusions seen in catatonia, typical of paranoid DP.

Keywords: catatonia, dementia praecox, Kraepelin, history

This report is the third in a series tracing the origins of Kraepelin’s concept of Dementia Praecox (DP) articulated in the 1899 sixth edition of his textbook.1,2 The first and second articles traced the development of the paranoid3 and hebephrenic subtypes.4 Here, I examine the catatonic subtype. I review all relevant clinical sections of the earlier editions of Kraepelin’s textbook, all of the 6 articles/monographs cited by Kraepelin in the catatonic DP section of his sixth edition, and 2 short relevant articles by Kraepelin.5,6

I include crucial quotes in the text, but most are placed into supplementary table 1. Table 1 summarizes the key catatonic signs and symptoms presented in Kahlbaum,7 Brosius,8 Neisser,9 and all of Kraepelin’s editions. Confusingly, Kraepelin uses the same term—DP—for his hebephrenic subtypes in his fourth and fifth editions as he later applies to the entire syndrome in his sixth edition. To avoid confusion, we use the term hebephrenia for this syndrome from the fourth to sixth edition.

Table 1.

Key Catatonic Signs, Symptoms, and Course of Illness as Reported by Reviewed Documents

| Author/Year | Diagnosis | YA | PC | SM | NEG | CE | PWF | TD, VER | DEL | DOI, BD | HAL | PO | Extra Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kahlbaum 1874 | Katatonie | − | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | +− | |

| Kraepelin 1887 2nd edition | Katatonic Verrücktheit | NI | − | +++ | NI | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | |

| Brosius 1877 | Katatonie | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | − | + | +- | |

| Neisser 1887 | Katatonie | − | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Kraepelin’s 1889 3rd edition | Katatonic Verrücktheit | NI | − | +++ | NI | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | |

| Kraepelin’s 1889 3rd edition | Katatonic Wahnsinn | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | Acute onset. disorientation |

| Kraepelin’s 1893 4th edition | Katatonic Verrücktheit | NI | − | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Kraepelin’s 1893 4th edition | Katatonie: Psychische Entartungs-processe | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | Association with hebephrenia |

| Kraepelin’s 1896 5th edition | Katatonie: Die Verblödungs- processe | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Notes importance of remissions |

| Kraepelin’s 1899 6th edition | Dementia Praecox | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | Flattened affect, indifference |

NI, no information provided; YA, young age at onset; PC, phasic sequential course; SM, stupor and mutism; NEG, negativism; CE, catatonic excitement; PWF, posturing or waxy flexibility; TD, thought disorder; VER, verbigeration; DEL, delusions; DOI, delusions of influence; BD, bizarre delusions; HAL, hallucinations; PO, poor outcome.

This is a relevant time to review the historical origins of catatonic DP. For the first time in the history of the DSM, DSM-510 does not contain a category of catatonic schizophrenia. Instead catatonia is present as a specifier associated with any mental disorder and can be diagnosed in the absence of knowledge as to the underlying disorder. In addition, interest in catatonia has increased recently.11–14

Kahlbaum 1874

The modern history of catatonia begins with Karl Kahlbaum’s (1828–1899) 1874 monograph: “Catatonia or “Muscular Tension” Insanity: A clinical form of psychiatric illness. The text contains 7 chapters and 25 case histories. I begin with 2 quotes, from the beginning and the end of the monograph:

In this work, I will attempt to describe a disease pattern which has somatic components, with particular involvement of the musculature; they occur as often here as in GPI [general paresis of the insane] and go along with certain psychic manifestations of the disease; in this particular mental disorder, they also play an important part in the form taken by the entire process of the disease. (see ref. 7, p. 8)

Catatonia is a brain disease with a cyclic, alternating course, in which the mental symptoms are, consecutively, melancholy, mania, stupor, confusion and eventually dementia. (see ref. 7, p. 93)

Three points are noteworthy. First, Kahlbaum saw parallels between his concept of catatonia and GPI, a recurring theme. Second, motoric/muscular abnormalities are central to his concept of catatonia. Third, the disorder has sequential phases experienced by all patients.

I focus on chapters 2 (symptomatology) and 6 (prognosis). First, Kahlbaum distinguishes between “an initial developmental stage” of catatonia and the terminal stage. He emphasizes the “changing, cyclic” course of the early stages. Sometimes the first depressive phase evolves directly into stupor. More commonly, patients transition to a state of “mania” which Kahlbaum characterizes as “rage, frenzy, excitation” (see ref. 7, p. 31). He writes “repeated transitions between conditions of depression and mania are frequently observed” (see ref. 7, p. 29). Only “in very rare” circumstances, does catatonia start with atonia. Kahlbaum’s approach to catatonia is part of his “prognostic-clinical” schema, which defined disorders jointly by distinct symptoms and specific stages of illness.15

Second, the later phases of catatonia are dominated by motoric and postural signs especially atonia, mutism and stupor. Typically, this phase includes posturing, “a prominent tendency to strange fixed positions … [patients] assume very strange postures” (see ref. 7, pp. 38–40). In more advanced cases, “grotesque stereotypes movements … [and] frequent grimacing” (see ref. 7, p. 49) are common.

Third, negativism is often prominent during this latter phase. Patients frequently demonstrate “involuntary rigidity of the limbs which often offers remarkable resistance to attempts at passive movement” (see ref. 7, p. 26). Kahlbaum elaborates in quote Ka-1 (supplementary table 1). Typical is case 14 (quote Ka-2).

Fourth, Kahlbaum singles out the “striking” feature of waxy flexibility (flexibilitas cerea), “lingering signs [of which] … may still be evidence in the stage of terminal dementia.” This somatic feature is, he states “unique in the diagnosis of this particular illness” (see ref. 7, p. 9). See quote Ka-3.

Fifth, phases of catatonic excitement were frequently present. In case 11 such “attacks” were characterized by “Wild, insane behavior, with arbitrary striking, shouting and talking … and biting” (see ref. 7, p. 36). Sixth, catatonia also manifests itself by “numerous abnormalities … of thought processes” (see ref. 7, p. 31). Most common were particular language/thought disorders outlined in quote Ka-4.

Seventh, active psychotic symptoms were rarely noted in Kahlbaum’s descriptions. Such features are “less characteristic and therefore less useful for the purpose of distinguishing the disease [catatonia] from other psychiatric disorders than the formal [motoric] symptoms” (see ref. 7, pp. 46–47). Delusions were noted in only 5 of Kahlbaum’s cases, 3 of which were bizarre, and hallucinations in 8 cases.

His chapter on prognosis begins:

… catatonia shows a contrast to GPI…. Whereas the prognosis of GPI is known … to be extremely bad, the prognosis of all forms of catatonia is by no means hopeless…. Recovery is relatively so frequent that this gratifying contrast with paralysis … must be recognized immediately. (see ref. 7, p. 87)

Kahlbaum does not comment systematically on outcome in his case reports. However, recoveries were not rare. Excluding cases dying in hospital, I found statements about outcome in 13 cases. Five did poorly while 8 cases had good outcomes. Kahlbaum notes that “as regards the general risk of a relapse, this is on the whole relatively small in catatonia” (see ref. 7, p. 91). However, a poor outcome is common when the patient displayed preoccupation with delusional beliefs (see ref. 7, p. 90).

Regarding age at onset, Kahlbaum writes “Catatonia occurs at all ages, from puberty to the most senior ages” (see ref. 7, p. 54). Kahlbaum does not give age at onset for his cases nor can it easily be determined. Age at evaluation is given for 22 cases with a mean (SD) of 32 (7.8). I would estimate the mean age at onset in his series was 28–30.

In summary, in addition to his emphasis on motoric signs, seven features of Kahlbaum’s catatonia are noteworthy (table 1): (1) sequential/phasic course, (2) wide range of ages at onset, (3) prominent signs of stupor and mutism, odd postures, and waxy flexibility, (4) typical excited phases of “wild, insane behavior”, (5) thought/language disturbances including disorganization and verbigeration, (6) infrequent positive psychotic symptoms and rare bizarre delusions, and (7) a mixed course frequently ending in recovery, although deterioration also occurred.

Brosius 1877

Casper Brosius (1825–1910) published in 1877 a review titled, “Catatonia: A psychiatric sketch”.8 The review begins with a discussion of the symptoms, signs and course of catatonia and then presents one case in detail and 3 more briefly. Brosius endorsed Kahlbaum’s description and emphasized eleven features of the catatonic syndrome.

First, its essence “lies in motor disturbances.” Second, Brosius endorsed the sequential phasic nature of catatonia. Third, stupor, a central feature of catatonia, is characterized by “muteness and immobility” and always occurs in catatonia but is “not permanent.” Fourth, negativism is often encountered including refusals to eat and toilet appropriately.

Fifth, catalepsy and posturing are frequently seen. Sixth, immobility is rarely complete, and careful observations will reveal short movements or expressions that indicate that the patient is aware of his surroundings. Seventh, speech abnormalities are common and quite characteristic. He gives a clear description of verbigeration “the same words or even whole sentences are repeated over and over in the same way or with small changes” (see ref. 8, p. 780). Eighth, “movement stereotypes” are frequent and highly indicative of catatonia. They can be violent and unexpected: “the patients who seem mute, immobile, withdrawn into themselves, entirely lacking in will and seemingly mindless, often react very violently” (see ref. 8, p. 775).

Ninth, catatonic agitation is common in this syndrome and described in quote Br-1. This excited phase is clinically distinct from that seen in mania lacking jokes and frequent rhyming. Tenth, Brosius never comments on the presence of positive psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) in catatonia. He does note that “a delusional intent can often not be found” (see ref. 8, p. 777). Of his 4 cases, one presents with delusions described as being of “crimes committed.” Hallucinations are not mentioned in the main text but are briefly noted in 2 cases. Finally, Brosius provides no clear statements about the course and prognosis of catatonia but implies that it is very variable (see quote Br-2).

The terminal state of his 4 cases varied from some symptoms of deterioration to apparent full recovery. The mean ages of his 4 cases was 23. Published 3 years after Kahlbaum, Brosius endorsed almost entirely his description of catatonia.

Kraepelin’s Second Edition 1887

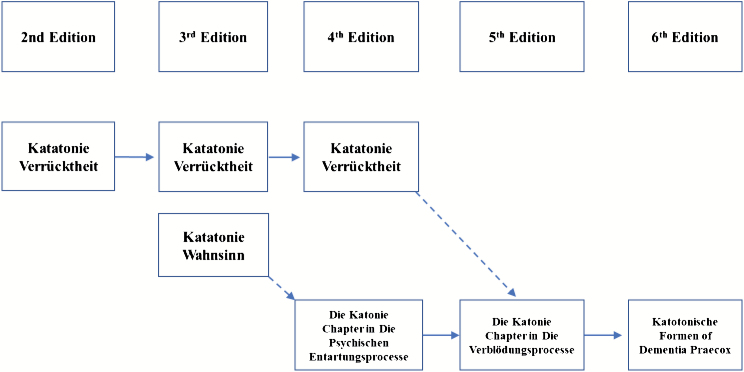

Catatonia had a migratory history in Kraepelin’s early editions (figure 1). The term does not occur in his first edition.16 In the second edition,17 Kraepelin describes one catatonic syndrome—a subform of Verrücktheit. This diagnostic category, then a broad category of delusional psychoses, evolved later into Kraepelin’s mature concept of paranoia (1899).3,18 His description begins

Figure 1.

The relationship of Kraepelin’s catatonic categories from his second through his sixth textbook edition.

As a further peculiar developmental form, primarily of hallucinatory persecutory delusion, we have to consider another clinical picture, which has been described as catatonic insanity (Verrücktheit). Initially, the psychosis displays the gradual development of delusions involving persecution, poisoning or also of influences…. After a short or a long time of the illness, often in connection with a vehement anxious exacerbation, the patient sinks into deep silence and apparently complete apathy…. His head is sunk, eyes closed, and his facial expression is rigid, mask-like and vacant. The whole day he stands in one place in a down-sunken or theatrical posture, countering passive movement with rigid resistance or, more commonly, providing pronounced “waxen flexibility” of the limbs…. (see ref. 17, pp. 336–337)

Contrary to Kahlbaum’s view that psychotic symptoms play a minimal role in catatonia, Kraepelin’s first catatonic syndrome emphasized such symptoms prominently.

In such cases, while acutely ill, speech was typically disordered and sometimes incomprehensible. Kraepelin describes the occurrence of “…foolish, incoherent, phrases which are repeated countless times (verbigeration according to Kahlbaum)” (see ref. 17, pp. 338–339) noting the diagnostic significance of this symptom “cannot be underestimated.”

The acute phase typically lasts weeks to months. Outcome is variable. Superficial recovery frequently occurs, although a patient often “still displays clear residues of the preceding disorder in his peculiar theatrical and stilted behavior, occasional unmotivated ‘poses’, [and] stereotypical … affected expressive movements” (see ref. 17, p. 338). More rarely, “… patients never entirely come out of the catatonic state, and instead pass over directly into definitive, more or less deep dementia” (see ref. 17, p. 339).

Furthermore, in his section on Melancholia attonita (ie, stuporous melancholia—a common pre-Kahlbaum diagnosis for “catatonia”), Kraepelin distinguished it from catatonic Verrücktheit (quote K2-1 supplementary table 1). In summarizing catatonic Verrücktheit, Kraepelin writes

The circumstance that catatonic conditions could occur in a whole series of illnesses, prompted Kahlbaum to summarize all these forms as a single clinical picture under the name catatonia. As this attempt does not seem satisfactory to me, I have separated, also in the description, such very divergent diseases according to clinical development, course and prognosis. (see ref. 17, p. 339)

In the first appearance of a catatonic syndrome in his textbook, Kraepelin does not accept Kahlbaum’s unitary view of this syndrome. The specific form of catatonia he describes, like Kahlbaum, included the key signs of stupor, waxy flexibility and verbigeration. However, distinct from Kahlbaum’s formulation, his syndrome featured prominent positive psychotic symptoms and made no mention of sequential phases.

Neisser 1887

Although Clemens Neisser’s (1841–1940) “Regarding Catatonia—A Contribution to Clinical Psychiatry” 9 was only a doctoral dissertation, written at the University of Leipzig in 1887, it was considered important enough by Kraepelin to cite. Beginning with a review of the catatonia concept, focused on Kahlbaum’s monograph, the remaining text included 12 detailed case histories interspersed with a few briefer cases and more general comments on the optimal nature of psychiatric diagnostic categories generally and Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia more specifically.

Contrary to the typical cross-sectional, symptom-focused diagnoses, Neisser was a strong advocate for Kahlbaum’s clinical method for conceptualizing psychiatric disorders (see quotes N-1 and N-2 supplementary table 1). He emphasized the importance of moving away from a solely psychological or symptomatic view of illness (quote N-3). Neisser strongly endorsed Kahlbaum’s concept of the sequential phases of catatonia, using the older term “melancholia attonita’ for the stuporous catatonic syndrome (quote N-4).

Neisser emphasized that the catatonic patient needs to be seen in his totality. It cannot be a symptomatic diagnosis—the course, the pattern of key symptoms and signs need to be taken into account. Like Kahlbaum, Neisser emphasizes the importance of the motoric features of catatonia. He describes the odd ritualistic behaviors seen even during periods of partial remissions in catatonic (quote N-5). He concluded his introductory summary with three points:

Firstly, melancholia attonita … is not an independent illness, instead it forms a more or less defined stage during the course of an illness process, which is distinguished by a typical sequence of different and specifically characterized disorders. Secondly, that a regular accompanying and essential partial phenomenon of this mental clinical picture, consists of tension anomalies in the region of the voluntary movement apparatus…. Thirdly … in the different stages of the illness, another series of symptoms with a more or less pathognomonic value, tend to occur, namely negativistic tendencies, fear of eating, mutism, verbigeration, movement and postural stereotypes…. (see ref. 9, p. 14)

Neisser firmly rejects a psychological explanation of catatonia (quote N-6) and then presents his 12 cases, hoping that they “may provide further material to confirm the empirical correctness of Kahlbaum’s clinical data” (see ref. 9, p. 15). Two differences between his cases and those of Kahlbaum are noteworthy. First, 10 of the cases demonstrated delusions or hallucinations, although only two included bizarre delusions. Second, of the 8 cases where outcome could be meaningfully determined, only one had a clear recovery. The mean age at evaluation of these cases was 30.5 (8.3) and nearly all had recent onsets.

Overall, Neisser’s monograph strongly supported the validity of Kahlbaum’s conceptualization of catatonia including its sequential phases, its emphasis on motoric abnormalities and a rather late age at onset. However, the case series differed in having a worse outcome and a much higher proportion of cases with positive psychotic symptoms.

Kraepelin’s Third Edition 1889

In his third edition, Kraepelin’s description of the catatonic form of Verrücktheit from the second edition is repeated with minimal change.19 In addition, he introduces a new diagnosis of “Katatonic Wahnsinn.” Wahnsinn is a problematic category of delusional psychosis typified, in Kraepelin’s nosology, by an acute presentation with mixed psychotic and affective symptoms. Behr gives a helpful description in quote B-1 supplementary table 1.

This category, included in his second through fourth editions disappears in his fifth, incorporated into Melancholia. In his overall introduction, Kraepelin writes: “Catatonic Wahnsinn, finally, includes the essential part of those clinical pictures which Kahlbaum has given the name of ‘catatonia’” (see ref. 19, p. 311).

When he gets to this form, Kraepelin provides more detail:

Under the name of catatonia, Kahlbaum has described a clinical picture which presents the symptoms of melancholia, mania, and stupor, in the case of an unfavorable course also that of disorientation and dementia, and which in addition, due the existence of certain motor symptoms such as spasms and inhibitions, also has the characteristic “catatonic” symptoms…. Although I must consider this summary with its conditions which are often contradictory etiologically, clinically and prognostically, as a schematic over-estimation …, as a result of certain experiences, I consider it appropriate to single out a certain group of cases from the field of “catatonia” as “catatonic Wahnsinn.” This is essentially the rather acute occurrence of confused delusions and hallucinations with episodic depressive or expansive states of agitation, and the phenomena of peculiar psychomotor constraints, which manifests, among other things, in cataleptic and spasmodic states. (see ref. 19, p. 332)

The emphasis is on the acute onset typically in young individuals. He continues

The emergence of the psychosis is usually very rapid …The patients then become disorientated, agitated, do not recognize their environment and give totally incoherent and inappropriate answers…. Usually, the patients, after a short time, sink into a peculiar condition of rigid stupor. They stop speaking or lisp occasional incoherent words. They lie or sit immobile, often with their eyes closed, curled up, do not react to being spoken to, to touch, to pin pricks, refuse to eat. (see ref. 19, pp. 333–334)

As with catatonic Verrücktheit, Kraepelin emphasized the positive symptom psychosis that typically accompany the stuporous phase (quote K3-1). He describes a number of classical catatonic symptoms typical of these cases (quote K3-2). Verbigeration is noted: “The patients declaim in pathetic but monotonous modulation, for hours or even days, the same meaningless combination of words…” (see ref. 19, p. 334). He refers only briefly to the differential diagnosis of his two catatonic syndromes:

Catatonic Verrücktheit differs from catatonic Wahnsinn in the acute development without a long-prepared delusional system [in the latter], as also by the outcome into disorientation or recovery. (see ref. 19, p. 336)

Outcome of Catatonic Wahnsinn is generally poor: “The prognosis is always to be regarded as doubtful. A great number of cases go over into conditions of incurable weakness” (see ref. 19, p. 335).

Although Kraepelin’s concept of catatonic Wahnsinn shared many of the signs described by Kahlbaum, it occurs in a different context—in an active acute psychotic state with prominent delusions and hallucinations and frequently disorientation. No mention is made of required phases. As suggested by this quote from his third edition, at this point, Kraepelin was clearly cognizant of the variability of catatonic signs and symptoms depending on clinical context.

… catatonic phenomena, similar to those of depression or exaltation, may develop under certain circumstances in the course of various mental disturbances. The symptom complex, however, appears to exhibit notable differences, depending on the ground upon which it is formed. (see ref. 19, p. 373)

Behr 1891

Albert Behr (1860–1919) received his medical degree from Dorpat in 1891 with a dissertation “The Question of Catatonia or Muscular Tension Insanity” 20 completed under the likely close supervision of Kraepelin, Professor at Dorpat from 1886 to 1891. His introduction reads “The present work originated as a result of the advice of Prof. Dr. E. Kraepelin, currently in Heidelberg, and I thank him for the friendly congeniality he always showed me.”

Behr began with a summary of Kahlbaum’s work (see quote B-2 supplementary table 1) and the literature evaluating Kahlbaum’s monograph, concluding that

the majority of authors lauded the masterfulness and the fineness of the clinical description of individual symptoms, such as “stupor,” “verbigeration,” etc. However, [most] declared that they were not in agreement with “catatonia” as a distinct illness. (see ref. 20, p. 5)

He concludes from his review that

… there are two viewpoints with regard to the conception of catatonia. The one speaks of catatonia as a disease unit, the other sees in it the partial symptoms and complications of the most varied mental disturbances. (see ref. 20, p. 7)

He supports the latter viewpoint (for details, see quote B-3). He suggests a way forward: “Only the prejudice-free observation and sober enumeration of facts can lead to a system, to an acutely defined diagnosis, to a symptomatology of mental disturbances” (see ref. 20, p. 8). He then quotes admiringly from Kraepelin’s inaugural Dorpat lecture21 (quote B-4). Behr specifically criticized Kahlbaum’s sequential stage model (quote B-5). Later, Behr states that “catatonia is not a cyclical illness and does not proceed in phases” (see ref. 20, p. 56). He notes the nonspecificity of many of the “catatonic” symptoms (quote B-6).

In a brief report to the Association of East-German Psychiatrists on 15 June 1890, entitled “Regarding Catalepsy”, Kraepelin quotes the same figure noted by Behr (8%–10%) for the rate of catalepsy in his Dorpat patients.5 Kraepelin describes 28 cases, the most common single cause being GPI. Of these 28, only six fitted into his most current categories of catatonic Verrücktheit or Wahnsinn.

Behr’s cases are typical of those presented by previous authors. Positive psychotic symptoms were seen in two cases both involving passivity phenomenon. Average age at evaluation was 27 (5.7). Only one case had a moderately good recovery, one could perform daily tasks but the other four had poor outcomes.

He begins his conclusion by criticizing the coherence of the catatonia concept (quote B-7). He argues that the diversity of the “character” of these cases, especially as manifest by differences in their course and outcome, belie the effort to consider them a single disease group. He re-emphasizes this key point, probably echoing the views of his mentor Kraepelin:

In the grouping and classification of mental disturbances especially the clinical character of the origin, the course, the duration and the outcome should be considered, while the formal elements, the picture of the condition, should be considered only secondarily. (see ref. 20, p. 55)

He then concludes:

As it follows from what has been discussed and from the examination of the individual case studies, that various mental disturbances display catatonic symptoms, we thus neither accept a common illness “catatonia” (Kahlbaum), nor do we believe that catatonia can be allocated to certain psychoses…. Instead, we are of the opinion that the majority of mental disturbances may display catatonic symptoms, that catatonic psychoses exist, but not catatonia. (see ref. 20, pp. 55–56)

Behr concludes that the catatonic syndrome as described by Kahlbaum and his supporters, Brosius and Neisser, does not constitute a single disorder. It fails to demonstrate a common origin, course and outcome. Perhaps Kraepelin took this conclusion as a challenge. Could he, in his life-long nosology project, find a form of catatonia that would meet these criteria?

Kraepelin’s Fourth Edition 1893

Catatonia syndromes are included in two places in Kraepelin’s fourth edition.22 Catatonic Verrücktheit is briefly described with half of the text being new, including this opening description:

Another peculiar type of course is distinguished by the emergence of certain catatonic characteristics. The patients become monosyllabic, withdrawn, finally entirely mute, alternating between cataleptic and negative resistance, take on intricate positions, drape their bedding in a striking manner, remain still for a long time in the same position. Typical verbigeration does not appear to occur…. Most commonly such catatonic episodes develop in the course of physical persecutory delusions or in cases where physical influencing is present. (see ref. 22, pp. 425–426)

Kraepelin notes a specific association between this catatonic syndrome and bizarre delusions of physical influence. Cases of Verrücktheit which demonstrated such prominent delusions were re-labeled fantastic Verrücktheit in his fifth edition and then placed into Paranoid Dementia Praecox in the sixth edition.3

Outcome is far from benign: “In many cases, one can observe, after the patient awakens from this state, that there is a considerable increase in mental weakness accompanied by very fantastic delusions” (see ref. 22, p. 426).

In the fourth edition section on Wahnsinn, Kraepelin writes

… I have, based on the latest observations, entirely eliminated the much disputed “catatonic” Wahnsinn, and instead placed it closer to the mental processes of degeneracy decline (Psychische Entartungsprocesse). (see ref. 22, p. 318)

Kraepelin was concerned with where to best place catatonic syndromes in his nosology. He decides to focus on an entirely new chapter in his text entitled Psychische Entartungsprocesse (Psychological Degeneration Process). It may be no accident that he here first cites Behr’s thesis.

This new category contains three chapters each of which will each evolve into a major DP subtype. The second, entitled “Katatonie,” begins with the text that introduced his third edition description of Catatonic Wahnsinn, supporting the thesis that part of the core of what is to become catatonic DP comes from the third edition description of catatonic Wahnsinn. I quote the last common sentence and then his novel perspective on the catatonic syndrome:

… as a result of certain observations, I will now single out a group of cases from the sphere of “Catatonia,” as a peculiar form of illness. Here we are essentially concerned with the acute and sub-acute appearance of peculiar states of agitation, accompanied by confused delusions, isolated hallucinations and the emergence of stereotypical and suggestible expressive gestures and actions, which transform into stupor and subsequent mental weakness (Schwachsinn). (see ref. 22, pp. 445–446)

Kraepelin is singling out a subgroup of Kahlbaum’s syndrome with two key features: positive psychotic symptoms of delusions and hallucinations and a poor outcome. While these features were also noted in catatonic Wahnsinn, this new syndrome does not share with the earlier version an emphasis on the acute presentation with associated confusion, depression and elation.

In subsequent text, Kraepelin outlines his view of this catatonic subtype of “Psychische Entartungsprocesse.” The syndrome “almost always” begins with depressive symptoms, the only nod seen here toward the original phasic nature of catatonia. But prominent delusions and often hallucinations soon ensue often of a fantastic nature. Soon thereafter, the patient sinks into stupor from which a “catatonic state” emerges, particularly characterized by negativism. Here is a characteristic quote (for the unredacted section see quote K4-1 supplementary table 1).

The patients stop speaking entirely (mutism) or only lisp occasional soft, incomprehensible words. They are completely inaccessible to any external input, do not react to being spoken to, to touch or even pin pricks…. Every attempt to actively intervene in the posture or movement of the patients usually encounters obstinate and immovable resistance. … The facial expression is motionless, mask-like. The lips are often pushed forward trunk like (“snout-spasm”) (Schauzkrampf), here and there displaying mild, rhythmically twitching movements. (see ref. 22, pp. 445–448)

Other motoric abnormalities are often noted:

A whole series of peculiar habits that patients display may originate in the same way as a result of an impulse that arises suddenly, and then, due to the tendency to stereotyping, recurs continuously. Amongst these are the already mentioned peculiar postures and the automaton-like movements which are observed here, the spasmodic pressing of splayed fingers against particular parts of the body, the compulsive head shaking and especially certain anomalies when eating. (see ref. 22, p. 451)

In addition to negativism, Kraepelin also notes opposing symptoms of an increased sensitivity to the environment (quote K4-2). Speech disorders are also characteristic (quote K4-3). States of mania/agitation are common in the course of catatonia:

More frequent than the sudden transition to dementia, is a temporary emergence of manic states of agitation. Sometimes these are only very temporarily inserted in the stupor. The patients suddenly become elated, merry, talkative, start to sing, to dance, laugh foolishly, act destructively, smear feces, become violent, to then just as rapidly return to their previous motionlessness. (see ref. 22, p. 453)

There is nothing about “sequential stages” in his description of these states. Kraepelin describes their typical outcome (for entire quote see K4-3):

After a good number of months … the catatonic symptoms gradually disappear.… The patients become freer in their movements … However, they are completely dull, impassive, are not able to provide information about simple things.… Traces of catalepsy, indications of posture or movement stereotyping, lack of cleanliness, unmotivated refusal to eat or gluttony are not uncommon. The ability to work is very meager or entirely absent … [they] often progresses to deep, apathetic dementia. (see ref. 22, pp. 452–454)

He then disagrees with Kahlbaum on the course of catatonia:

Kahlbaum did not consider the prognosis of catatonia as very unfavorable and reported a number of recoveries. I would, however, doubt that his cases were of a similar kind…. All cases with pronounced catatonic symptoms I have observed over the years, without exception, resulted in the unfavorable outcome described above. (see ref. 22, p. 454)

In a final section, he comments on the young age at onset seen with catatonia and its likely association with hebephrenia.

All these cases involved people between the ages of 19 and 26…. Catatonia may thus be closely related to hebephrenia, a view which is supported by the frequency of catatonic indications in this psychosis, as well as the occurrence of certain transitional cases between the two forms. (see ref. 22, p. 454)

Kraepelin’s fourth edition represents a shift in his view on catatonic illness as he begins to develop the concept of Psychische Entartungsprocesse into which he integrates his concept of catatonic Wahnsinn (figure 1) and which matures, two editions later, into DP. For catatonia, we see a greater focus on poor outcomes, positive psychotic symptoms, young age at onset, and the beginnings of a closer clinical and etiologic relationship with hebephrenia.

Kraepelin’s Fifth Edition 1896

In his fifth edition,23 Kraepelin removes all mention of catatonic subforms from his chapter on Verrücktheit leaving the only description of a catatonic syndrome in the chapter Die Verblödungsprocesse (dementing processes) of which 55% is new. His opening paragraph contains new text more positive about Kahlbaum’s views than he had previously articulated:

If, however, I have to doubt the cohesiveness of all the clinical pictures [of catatonia] united by Kahlbaum, I nevertheless, as a result of many observations, am compelled to acknowledge that a majority of those cases represent a peculiar form of illness. (see ref. 23, p. 442)

Within Kahlbaum’s broad syndrome, Kraepelin argues that a substantial proportion fit into his narrower construct of catatonic Verblödungsprocesse. He then adds text proposing a new mode of onset. He had previously described a typical form beginning with dysphoria, withdrawal and the slow emergence of positive psychotic symptoms before motor signs develop. The second begins with catatonic excitement (see quote K5-1 supplementary table 1).

Little change is seen in his description of the stuporous phase into which both forms of onset evolve, and the development of negativism, catalepsy and thought disorder. He gives several new examples of thought disorder (quote K5-2), a photo of 6 catatonic patients and examples of handwriting. In his section on course, he notes

An additional deviation of the usual course of the illness is distinguished by the emergence of developed delusions. Delusions and hallucinations regularly occur temporarily during the development of the illness. Sometimes, however, these conceptions are retained for a longer time and developed further. (see ref. 23, p. 455)

His examples include bizarre and passivity delusions similar to those contained in his later description of paranoid DP (quote K5-3). Finally, he comments on remissions, a topic which he did not discuss previously (where he noted that all cases “with pronounced catatonic symptoms … resulted in unfavorable outcomes”).

An extraordinarily important phenomenon during the course of catatonia is the remissions. All observers report that the patients suddenly are entirely lucid, clear and insightful, admittedly only for a short time, for hours or days…. We encounter the patients, who until then had seemed to be completely confused, immersed in their foolish actions … now suddenly are calm and entirely ordered. He knows time and place, the people in his environment, remembers events, also his own senseless actions, admits that he is ill, and writes a coherent, sensible letter to his relatives. (see ref. 23, p. 455)

Does this observation contradict his prior claims about unfavorable outcomes in catatonia?

In a considerable number of cases … more than a third …, an abatement of the illness may also continue for a long period, so that it appears to be a recovery. Almost always … there are certain peculiarities … which indicate that this was never a true recovery. Included are unfree, compulsive, stilted or strikingly quiet, withdrawn behavior, agitation and incomplete insight into the illness. The recurrence of the illness usually takes place after 5 years, but may in single cases occur after 8, 10 or even more years … a recurrence of the illness can be considered to be very likely…. (see ref. 23, p. 456)

He continues

Whether complete recovery is possible, as Kahlbaum and after him most researchers have indicated, I have to leave undecided based on my observations. I have the strong suspicion that, in many cases, they have allowed themselves to be deceived by confusing it with periodic illnesses and also due to the occurrence of long periods of remissions…. (see ref. 23, p. 456)

He continues to believe that dementia is the most common outcome for catatonia, but milder, less deteriorated outcomes do occur. Finally, he notes the young age at onset of catatonia: “About half of the cases begin before the age of 22” (see ref. 23, p. 458).

The description of the catatonic form of his “dementing process” in Kraepelin’s fifth edition resembles closely that seen in his fourth edition. Two changes are noteworthy. First, he emphasizes more the prominence and potentially long duration of positive psychotic symptoms. Second, likely resulting from the careful follow-up studies he was then conducting at Heidelberg, Kraepelin reaffirmed, at least in part, Kahlbaum’s earlier observations on remissions in the course of catatonia but raised concerns about their permanence.

Kraepelin 1896

In 1896, Kraepelin presented a paper “Regarding Remissions in Catatonia” 6 to the Conference of Southwest German Alienists containing new data on the long-term course of catatonia. In his 63 “certain” patients, 24 (38%) demonstrated remissions. Fourteen of these relapsed and follow-up was attempted:

In the 10 cases about which there was certain news about the behavior of the patients, there was only a single female patient who was seen as healthy by her family during the remission. In all the other cases, there was either a lack of insight into the illness, or the patients displayed some or other small notable traits. (see ref. 6, p. 1126)

In the remaining 10, Kraepelin obtained information about 6 of them: “News could be obtained about 2 of them and 4 of them presented themselves personally.” From this contact “… it became clear that catalepsy, embarrassed constrained behavior, and a tendency to unmotivated laughter” (see ref. 6, p. 1126) was noted in these individuals.

Kraepelin ended with four conclusions about catatonia:

First, in catatonia remissions are frequent…. These can continue for a number of years, even more than 10. Second, during the interval the patients are frequently not entirely healthy, instead they present certain peculiarities. Third, if a person has once fallen ill with catatonia, there is a good chance that, sooner or later, they will relapse. Fourth, catatonia concerns an organic illness of the brain, which leads to a more or less high degree of dementia (Verblödung). (see ref. 6, p. 1127)

Using follow-up methods, Kraepelin collected data to verify that the cases of catatonia that he was diagnosing in Heidelberg often had a remitting, relapsing course, but typically the outcome was poor, usually ending in dementia.

Aschaffenburg 1897

When Gustav Aschaffenburg (1866–1944)24 gave a lecture to a session chaired by Kraepelin on November 7, 1897, to the Conference of South-West German Alienists entitled “The Catatonia Question,” he was working as Kraepelin’s first assistant in the psychiatric university clinic in Heidelberg, where Kraepelin was Professor of Psychiatry from 1891 to 1903. The lecture contained no case reports25 but provides “the detailed study and the most careful comparison of 227 case histories [admitted to Kraepelin’s clinic] between April 1891 and September 1897” (see ref. 25, p. 1004). This study was surely done under Kraepelin’s supervision. He starts by articulating his theoretical approach to psychiatric nosology (quote A-1).

He then reviews an exchange he had with Carl Fürstner (1848–1906), Kraepelin’s predecessor in Heidelberg, who suggested the impossibility of reviewing catatonia without including hebephrenia (quote A-2). Much of this essay reviews the history of the catatonia concept from Kahlbaum to Kraepelin. Agreeing with my review of his case material, Aschaffenburg writes of Kahlbaum’s description of catatonia that “He considers the prognosis of the [affected] individuals … to be good” (see ref. 25, p. 1007).

His comments on the recently published fifth edition of Kraepelin’s textbook (1896) are of interest (quote A-3). He then reviews results from his case series which supports Kraepelin’s conclusions. He reaches two conclusions about the course of illness. First,

… the subsequent stage of the psychosis, whether it is a condition of agitation or calm, whether delusions occur or not, will not be mania or Verrücktheit. Instead it will only be a specifically colored catatonic agitation, delusions on a catatonic basis. (see ref. 25, p. 1013)

That is, the disease course is consistent, will not go through the sequential stages of Kahlbaum and is not related to the then modern concept of the affective syndrome of mania.26 Second, “… the outcome of the illness will be mental weakness … [which] also has peculiar indicators which allow a conclusion about the background” (see ref. 25, p. 1013). That is, certain catatonic features persist in the end state. He continues “…the ultimate degree of impairment can be extraordinarily divergent. We can distinguish all levels from the deepest dementia through to seeming recovery” (see ref. 25, p. 1013).

He vividly describes the range of outcomes (quote A-4) and then outlines other subtle catatonic signs in the better outcome cases. He next then comments on the close relationship between hebephrenia and catatonia, first by noting how often cases of hebephrenia later in their course show catatonic signs:

Sometimes, however, we may observe in a patient … that the catatonic symptoms had only arisen recently, after the patient had already for a long time been considered demented. These are the cases which initially corresponded to the clinical picture of hebephrenia in Hecker’s sense. (see ref. 25, p. 1015)

He further elaborates on the frequent blending of hebephrenic and catatonic signs of illness (quote A-5) and concludes that a clear distinction between them is often impossible (quote A-6). He disagrees with Kraepelin’s fifth edition regarding the independence of the hebephrenic and catatonic syndromes (quote A-7), citing data collected in Kraepelin’s own clinic against him.

In anticipation of Kraepelin’s sixth edition, Aschaffenburg then summarizes his thinking about the relationship between hebephrenia, catatonia and the emerging concept of dementia praecox:

…my knowledge does not allow any other conclusion other than the assumption that the diseases of hebephrenia and catatonia form a unified disease process. The name “dementia praecox” seems to me to be the most suitable. It indicates the characteristic of the illness, the premature development of mental weakness…. (see ref. 25, p. 1017)

Aschaffenburg emphasizes 3 overall points about the catatonia: (1) it did not fit the “sequential stage model,” (2) the most valid form has a poor course and outcome, and (3) that form of catatonia illness is closely related to hebephrenia.

Schüle 1897

Heinrich Schüle (1840–1916), a major figure in late 19th century German psychiatry, was originally to present alongside Aschaffenburg but it was delayed due to illness, being presented later that year at a Congress in Moscow. “Regarding the Catatonia Question—A Clinical Study” contained no case histories.27 The writing style is dense.

While praising Kahlbaum’s descriptions, Schüle begins by noting the non-specificity of key catatonic signs. He writes “...the ensemble of the phenomena … applies to a number of different psychotic states of illness, partly permanent, partly episodic” (see ref. 27, p. 518). He continues in quote S-1 supplementary table 1.

After a detailed analysis of the major motoric and “mental” symptoms attributed to catatonia, Schüle begins his conclusions elaborating further in quote S-2:

Initially I would like to state that I cannot accept any of the illnesses included here by Kahlbaum. Even the later delimitation, subsequent to that of Kahlbaum, by Neisser and more recently by Kraepelin, does not seem quite right to me. (see ref. 27, p. 534)

Then exploring the relationship between the catatonia syndrome and hebephrenia, he writes

I can only recognize a repetition of the so-called primary mental impairment in the previously described (severe) clinical picture [of catatonia and], in specie, [hebephrenia as described by] … Hecker. Here, as there, the same mental symptoms of agitation and then exhaustion, mixed and alternating. In both conditions the same course leads to more or less rapid and sometimes peculiar mental weakness. …I deviate here from Kraepelin, insofar as I am not able to find dramatic differences [between catatonia and hebephrenia]…. True catatonia (severe form) is thus essentially only a primary (very often hebephrenic) mental impairment. (see ref. 27, pp. 547–548)

Is catatonia “a new species of illness”? Schüle suggests not. But the result is not “…that the catatonic cases simply and without further ado disappear into what already is in existence, and that things remain as before.” Rather, from Kahlbaum “we have discovered that catatonic mental impairment maintains a peculiar formation [and] it is … not possible to deny its special traits” (see ref. 27, p. 549).

Schüle suggests that considering catatonia as a specific form of mental impairment is one of the best uses of Kahlbaum’s general insights. But he writes

The value of this [conclusion] is not decreased by the fact that it [catatonia] occurs also in other process forms, is observed sometimes in other clinical groups and with other origins …. (p. 549)

He elaborates, in quote S-3, on the possible utility of catatonic subforms of other conditions. In his final paragraph, he comments on the prognostic utility of catatonic signs when occurring early in an illness course (quote S-4).

I would emphasize two points in this difficult text. First, along with Behr, Schüle is deeply skeptical of the validity of Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia. The features of this syndrome are too diverse and nonspecific. Second, one subform likely has clinical validity and is characterized by its poor prognosis, frequent termination in a demented state and close relationship with hebephrenia. It is noteworthy that Kraepelin added to his sixth edition references to the two recent articles by Schüle and Aschaffenburg that both support his addition to DP, a syndrome historically anchored in Hecker’s hebephrenia, of a catatonic subtype.

Kraepelin’s Sixth Edition 1899

In Kraepelin’s sixth edition, the only catatonic syndrome described is the subtype of his new disorder DP.1 His description is based on the parallel section in Die Verblödungsprocesse, but 64% is new largely reflecting enriched clinical details. The introductory paragraphs are unchanged from the fifth edition but the section in which he introduces the onset of delusions and hallucinations early in the disease course is expanded 3-fold.

The delusions are often bizarre and ornate, frequently involving passivity symptoms and including persecutory, grandiose, somatic and self-deprecatory themes. Hallucinations are also prominent. For a representative quote, see K6-1 supplementary table 1. Later in this chapter, he notes that these positive symptoms, prominent during the active catatonic symptoms, often persist after the motoric signs have disappeared.

In further new text, he emphasizes the clouding of consciousness and bewilderment demonstrated by most patients early in their course. Their speech and thought are highly disturbed: “The sequence of ideas is muddled and incoherent, and thought is in most cases seriously impaired, as is shown by the patients’ nonsensical and contradictory utterances” (see ref. 1, p. 162).

He then describes the next phase of the illness:

This first phase of the disease, which in all principal features resembles that of certain hebephrenic forms, is followed in more or less distinct development by those conditions which are characteristic of catatonia in particular, catatonic stupor and catatonic agitation. (see ref. 1, p. 163)

He emphasizes similarities in the early phases of catatonic and hebephrenia DP and their ages at onset (72% of hebephrenic and 68% of catatonic cases onsetting before age 25 (see ref. 1, p. 201)). He then reviews the specific catatonic signs including negativism, command automatisms, mutism, catalepsy. For these new vivid clinical descriptions see quote K6-2.

Kraepelin continues to support two different forms of onset of catatonia: “stupor/depression” and agitation. He elaborates on the description of catatonic agitation, noting the close association of catatonic stupor and agitation (Quote K6-3). Kraepelin comments on two clinical features not noted previously: lack of insight and flattened affect: “In keeping with their odd behavior and their delusions, the patients are mostly remarkably indifferent” (see ref. 1, p. 174).

He concludes his catatonia text with a new discussion of the course and outcome of the disorder, presumably arising from recent observations made in Heidelberg. Forty percent of catatonic cases do not reach a state of classical dementia. The largest proportion of this group (68%) have continued impairments although their classical symptoms cease.

Subtle changes persist in these patients: grimacing, mannerisms, dullness, and increased fatigability. Their work capacity is considerably impaired. In the remaining improved patients, are ones “which we usually consider to be cured…. Here, all morbid disturbances disappear so completely that the convalescents fill their former position in life again just as they did before” (see ref. 1, p. 178). But the long-term outcome of such cases remains uncertain.

… the fact that the duration of the recovery has as yet only been ascertained for a few years in most cases. … I have already seen a whole series of my seemingly cured catatonics fall ill again and so it has to be left open, for the time being, how many of the recoveries cited really are to be considered … permanent. (see ref. 1, p. 179)

He notes “It has unfortunately not yet been possible for me to discover any definite clues from which one could infer the probable outcome of the individual case” (see ref. 1, p. 180). The only prognostic features of which he feels confident is rapidity of onset. This, he concludes, explains the better outcome in catatonia vs. hebephrenia because “an acute beginning with strong agitation” is far more common in the former than the latter.

Compared with his fifth edition description of the catatonic subtype of Die Verblödungsprocesse, three changes are made in Kraepelin’s description of catatonic DP. First, the presence and persistence of positive psychotic symptoms are yet more strongly emphasized as are their bizarre features. Second, he outlines in more detail the course of catatonia including that an appreciable proportion of cases do not, at least initially, have poor outcomes. Third, he gives stronger greater emphasis to the similarity of the symptoms, signs, course and age at onset of catatonia and hebephrenia. Of these three changes, two bring catatonia closer to hebephrenic and paranoid DP, demonstrating substantial sharing of symptoms and signs. One, however, pulls in the other direction—showing a difference in course for catatonic DP compared with the other two subtypes where remissions in the course are considerably rarer.

Discussion

I have traced, through 13 relevant texts, the pathway from the diagnostic construct of catatonia proposed by Kahlbaum’s in 1874 to the catatonic subtype of Kraepelin’s DP in his 1899 sixth textbook edition. I examined: (1) 6 articles/monographs cited in the catatonia sections of Kraepelin’s texts, (2) sections of 5 of Kraepelin’s textbook editions (second to sixth) (figure 1), and (3) two published versions of talks given by Kraepelin. Two of the reviewed articles were authored by mentees of Kraepelin so he would have likely influenced their content.

Of the numerous issues raised, 6 are particularly noteworthy. First, Kahlbaum and his close followers Brosius and Neisser saw catatonia as having clear sequential stages beginning with melancholia, and then developing manic, catatonic and potentially demented phases. While central to the initial conceptualization of the catatonic syndrome, this model was largely ignored by Aschaffenburg, Schüle and Kraepelin in his fourth through sixth editions.

Second, a recurrent question in these texts was the specificity of the key catatonic signs of mutism, stupor, catalepsy, negativism, and verbigeration. Do they define a distinct disorder or were they nonspecific occurring in a wide array of psychiatric conditions? Two of the authors cited by Kraepelin, Behr—his own student—and Schüle argued for their nonspecificity. Kraepelin’s creation of catatonic DP was likely in response to their concerns, an effort to delineate a form of catatonic illness with greater diagnostic specificity than Kahlbaum’s original conceptualization.

Third, both Kahlbaum and Brosius described a catatonic syndrome where delusions and hallucinations were neither prominent nor diagnostically important. Interestingly, Neisser’s cases had more prominent psychotic features. Kraepelin’s first catatonic diagnosis, in his second edition, was a subform of the delusional syndrome of Verrücktheit. Positive psychotic symptoms were a central feature. This syndrome continued with minimal change in his third edition. However, in his fourth edition, Kraepelin more tightly linked catatonic Verrücktheit with bizarre passivity delusions. In his fifth edition, he eliminated this category and created, as his sole catatonic syndrome, a catatonic form of Die Verblödungsprocesse. Kraepelin further emphasized the prominence of bizarre and passivity delusions in the new text added to the catatonic DP section in the sixth edition. In several stages across these documents, we see a gradual steadily increasing emphasis on the role of positive psychotic symptoms in catatonia, from unimportant in Kahlbaum to central in Kraepelin’s catatonic DP.

Fourth, the outcome of Kahlbaum’s and Brosius’s cases of catatonia were quite variable, with full recovery being common. Over Kraepelin’s early editions, he modified this position considerably, increasingly emphasizing poor outcome. Interestingly, Kraepelin’s position was consistent with Kahlbaum’s formulation in one sense—that the earlier author had emphasized delusional preoccupation as a poor prognostic sign for catatonia. Kraepelin, from his second edition onward, always saw psychotic symptoms as more central to the catatonic syndrome than Kahlbaum. However, after arriving in Heidelberg, where he first conducted systematic follow-ups of his cases, he observed in his fifth edition that, at least in the short term, remissions of catatonia were not uncommon. Investigating this question further utilizing, he presented data suggesting that, given sufficient time, most catatonic cases eventually had a poor outcome. However, in his sixth edition, he returns with new data showing that, over the short-term, a significant proportion of catatonic cases had favorable outcomes.

Fifth, as described by Kahlbaum, catatonia had onsets throughout adult life (“from puberty to the most senior ages”) with an estimated median age at onset in the late 20s. However, in Kraepelin’s fourth through sixth editions, he repeatedly noted the relatively early onset of his catatonic disorder with mean onsets typically in the early 20s. Related to this view of catatonia as a disorder of early adult life, in his fourth edition, Kraepelin first proposed that catatonia may have a close relationship with hebephrenia. This point was explicitly emphasized both by Aschaffenburg and Schüle and taken up again by Kraepelin in his fourth edition.

Finally, as clearly stated in his second and third editions and later amplified by his student, Behr, Kraepelin never accepted Kahlbaum’s diagnostic concept of catatonia tout court. He cited an additional author—Schüle—who also rejected the coherence of Kahlbaum’s syndrome. Rather, Kraepelin experimented in his second through sixth editions with a range of catatonic syndromes leading up to concept of catatonic DP. All of these diagnostic formulations included catatonia as a form of another disorder rather than as a free-standing condition. He clearly stated that catatonic DP did not incorporate all possible catatonic syndromes. Indeed, in his sixth edition, he specifically noted that prominent catatonic signs can be seen in febrile delirium, general paresis and melancholia. After substantial consideration, Kraepelin judged that his catatonic subtype of DP was the most valid and clinically useful of the possible subforms of catatonic syndromes, rejecting those he initially considered to fit better into Verrücktheit or Wahnsinn.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Eric Engstrom, PhD provided advice on key references and historical background material. Eric Engstrom, PhD and Stephan Heckers, MD gave helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. The translations from the German appearing here were done in collaboration with Astrid Klee, MA. The author reports no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. 6th ed Leipzig: Barth; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kraepelin E. Psychiatry, a Textbook for Students and Physicians (Translation of the 6th Edition of Psychiatrie-Translator Volume 2-Sabine Ayed). Quen Jaques, ed. Canton, MA: Science History Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kendler KS. The development of Kraepelin’s mature diagnostic concepts of paranoia (Die Verrücktheit) and paranoid dementia praecox (Dementia Paranoides): a close reading of his textbooks from 1887 to 1899. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75:1280–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kendler KS. The development of Kraepelin’s mature diagnostic concept of hebephrenia: a close reading of relevant texts of Hecker, Daraszkiewicz and Kraepelin. Mol Psychiatry. published online ahead of print April 9, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kraepelin E. Ueber Katalepsie. Allgemeine Zeitschrift fur Psychiatrie. 1892;48:170–172. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kraepelin E. Über Remissionen bei Katatonie. Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin. 1896;52:1126–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kahlbaum KL. Catatonia: Translated from the German Die Katatonie oder das Spannungsirresein (1874) by Y. Levij, M.D. and T. Pridan, M.D. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brosius C. Die katatonie: eine psychiatrische skizze. Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin. 1877;33:770–802. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neisser C. Über Die Katatonie: Ein Beitrag zur Klinischen Psychiatrie. Stuttgart: Verlag Von Ferdinand Enke; 1887. [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition, DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shorter E, Fink M.. The madness of fear: a history of catatonia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oldham M. A diversified theory of catatonia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:554–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walther S, Stegmayer K, Wilson JE, Heckers S. Structure and neural mechanisms of catatonia. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, David AS. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:620–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kendler KS, Engstrom EJ. Kahlbaum, Hecker, and Kraepelin and the transition from psychiatric symptom complexes to empirical disease forms. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(2):102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kraepelin E. Compendium der Psychiatrie: Zum Gebrauche für Studirende und Aerzte. Leipzig: Verlag von Ambr. Abel; 1883. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch für Studirende un Aerzte. 2nd ed Leipzig: Abel; 1887. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kendler KS. The genealogy of dementia praecox I: signs and symptoms of delusional psychoses from 1880 to 1900. Schizophr Bull 2019;45:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch für Studirende un Aerzte. 3rd ed Leipzig: J.A. Barth; 1889. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Behr A. Die Frage der “Katatonie” oder des Irreseins mit Spannung Dorpat University, 1891. Riga: WF Häcker; 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stacey D, Clarke TK, Schumann G. The genetics of alcoholism. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch für Studirende un Aerzte. 4th ed Leipzig: Abel; 1893. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. 5th ed Leipzig: Barth; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanner L. In memoriam: gustav aschaffenburg 1866–1944. Am J Psychiatry. 1944;101:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aschaffenburg G. Die Katatoniefrage. Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin. 1898;54:1004–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kendler KS. The genealogy of the clinical syndrome of mania: signs and symptoms described in psychiatric texts from 1880–1900. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1573–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schüle H. Zur katatonie-frage: eine klinische Studie. Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und Psychisch-Gerichtliche Medizin. 1898;54:515–552. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.