Abstract

This paper examines the structure of bilateral tourism and identifies five broad categories of factors that may affect the overall size of tourism flows. Such analysis of tourism is important because diplomacy and trade continues to be conducted on a nation-to-nation basis despite a growing shift towards multilateralism in free trade blocks such as the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement. Further, Bilateralism is important because countries have reduced abilities to control tourism imports in an era of growing globalization. A framework that may be employed to analyze problems in bilateral tourism flows is also outlined.

Keywords: bilateral framework, destination competitiveness, tourism flows

Résumé

Les facteurs ayant un effet sur les flux du tourisme bilatéral. Cet article examine la structure du tourisme bilatéral et identifie cinq grandes catégories de facteurs qui peuvent avoir des conséquences sur l’importance globale de ses flux. Une telle analyse du tourisme est importante, parce que la diplomatie et le commerce continuent à être menés entre deux nations à la fois, bien qu’il y ait actuellement une croissance de relations multilatérales avec des blocs de libre-échange tels que l’Union européenne et l’Accord de libre-échange nord-américain. En plus, les accords bilatéraux sont importants, parce que les pays ont des possibilités réduites pour contrôler les importations de tourisme à une époque de mondialisation croissante. On expose aussi les grandes lignes d’un cadre théorique qui pourrait être utilisé pour analyser des problèmes de flux bilatéraux.

Mots-clés: cadre bilatéral, compétitivité des destinations, flux de tourisme

Introduction

In recent decades, tourism has emerged as one of a small group of service industries that increasingly dominate the post-industrial global economy. Because of the volume of funds involved, estimated to be $514 billion (WTO 2003), tourism imports and exports can significantly influence national balance of payments accounts. In 2000, for example, Japan and Germany recorded net tourism deficits of $28.5 billion and $29.9 billion, respectively, while the United States recorded a net tourism balance of $20.2 billion (WTO 2002). As world trade moves towards reducing trading barriers, the ability of countries to unilaterally control tourism exports and imports is becoming increasingly difficult (Wanhill 2000). There are forced to look for non-regulatory measures to influence flows, such as increasing national attractiveness and competitiveness on a market-by-market or bilateral basis.

This paper examines a range of factors that determine the structure of bilateral tourism. The discussion focuses on techniques for identifying underlying demand factors and identifies the role of non-economic factors. Increased understanding of these factors will assist policymakers in developing more effective policies to increase destination competitiveness and attractiveness within a bilateral setting.

Bilateral tourism describes the flow of tourists between two countries, irrespective of proximity, and is measured by actual tourists, their percentage as a proportion of inbound and outbound flows, and the state of the tourism balance of payments. The quantum of the flow between country pairs is a function of a matrix of interrelated factors that includes the public and private sector structures supporting flows, diplomatic relations, and economic and noneconomic factors. Countries that have removed barriers to citizens undertaking foreign tourism have limited capability to regulate outbound flows, but still retain significant capacity to increase inbound flows through measures designed to enhance destination competitiveness and encourage citizens to substitute domestic for international tourism. Policies designed to alter the level of inbound and outbound flows through nonregulatory measures may become important where countries facing a balance of payments crisis decide to adopt policies designed to increase exports and reduce imports of tourism. However, the recent trend towards multilateralism is a factor that compounds the problems encountered when attempts are made to reduce imbalances. As Prideaux and Kim (1999) observed, it is unrealistic to expect bilateral tourism to be in balance between countries because of the complexities of the international nature of demand, differences in national income, exchange rates, existing trading relationships, and differences in population size. Therefore, the study of bilateral tourism is closely allied to research into competitiveness, flows, and attractiveness, but differs in that it looks at factors that influence the volume and composition of flows in both directions between country pairs.

To date a framework for the systematic analysis of bilateral tourism has not been developed. Such analysis of the factors underpinning bilateral flows will enable identification of strategies that can be adopted to increase inbound flows, to reduce monetary imbalance, and thus to increase overall destination competitiveness. Examples of the types of strategies used were identified by Prideaux and Kim (1999), who also noted that one of the major issues in this area may be the desire to maximize opportunities and encourage tourism for the benefits that may accrue in other areas, including cultural exchanges, defense, trade, and international goodwill.

Bilateralism in tourism

The methodology used in this study combined a review of the literature with an analysis of tourist flow data and limited case study analysis. The steps adopted were: review of the literature to identify factors influencing bilateral flows; examination of models, typologies, and previous research into destination competitiveness to identify economic and noneconomic factors affecting flows; and an analysis of bilateral tourism data and the circumstances governing these flows to identify further factors. Based on these findings, the Bilateral Tourism Framework was developed (Table 1 ). To examine the significance of specific factors, Australia was used as a case study.

Table 1.

Categories of Factors that Comprise the Bilateral Framework

| Category | Factors (Examples) |

|---|---|

| Demand | |

| Price | Cost of travel |

| Personal choice | Travel versus other forms of consumption |

| Government Responsibilities | |

| State of diplomatic relations | Facilitates or discourages travel |

| Government policy towards tourism | Visa and passport regulations |

| Transport policy | Bilateral aviation agreements |

| Currency restrictions | Level of restrictions on import or export of currency |

| Promotion and marketing | Level of public and private sector funding |

| Government regulations | Designed to assist or hinder tourism development |

| Government supplied goods and services | Security, public health, policing |

| Economic policy | Does government have expansionary policies to stimulate tourism |

| Private Sector Factors | |

| Travel infrastructure | Efficiency of tour operators |

| Domestic price levels | Restrict or encourage personal consumption |

| Intangible Factors | |

| Quality of the nation’s attractions and national attractiveness | Positive attractiveness encourages travel, negative attractiveness discourage travel |

| Icons and images | Unique icons encourage travel |

| Barriers to bilateral tourism | Distance, cultural differences |

| Other factors including media | Positive or negative images |

| External Economic Factors | |

| Efficiency of national economy | An efficient economy provides competitively prices goods and services |

| Competition | Impacts on visitor numbers and destination prices |

| Exchange rates | Impacts on relative price levels |

| Income effect | Determines number of people able to participate in travel |

| Elasticity and Substitution effect | If prices increase consumers seek substitute destinations |

| External Political and Health Factors | |

| Terrorism and political risk | Known level of terrorist risk |

| State of international relations | Friendly is a positive factor, unfriendly is a negative factor |

| Health | State of public health system |

The structure and significance of bilateral tourism has received relatively little attention in the literature, although a number of theories have been developed to explain flows between countries. Demand factors were the most frequently cited, followed by destination competitiveness (Crouch 1994). In an analysis of 100 papers examining demand factors, Lim (1999) found that the most often cited explanatory variables for demand were income (84%), followed by relative prices (74%), and transport costs (55%). In assessing bilateral tourism from an economic viewpoint, Mathieson and Wall (1982) discussed the implications of measures designed to regain trade balances, Prideaux and Witt (2000) examined bilateral flows between countries in the ASEAN group and Australia, King and Choi (1999) considered the case of South Korea and Australia, Yu (1998) examined flow patterns between China and Taiwan, and Dwyer (2001) examined a range of issues related to destination competitiveness.

A number of researchers have postulated that increasing flows between countries involved in some form of hostility may be a positive force, able to reduce tension and suspicion by influencing national politics, international relations, and world peace (D’Amore, 1988, Hobson and Ko, 1994, Jafari, 1989, Var et al, 1989). Other researchers have focused on the role that tourism can play in normalizing relationships between partitioned countries (Kim and Crompton, 1990, Yu, 1997, Zhang, 1993, Kim and Prideaux, 2003). While usually classified as peace studies, these relationships also describe a specific form of bilateral tourism. Butler and Mao (1996), for example, postulated that tourism between politically divided states could assist in reducing tensions and promote greater political understanding.

A number of studies have identified specific issues that affect bilateral flows (Godfrey, 1999, Langlois et al, 1999, Murphy and Williams, 1999). Culture is one such issue that has been identified by numerous researchers (Master and Prideaux, 2000, Reisinger and Turner, 1997, Reisinger and Turner, 2002, Sussmann and Rashcovsky, 1997). However, research into international flows has generally overlooked the importance of bilateral tourism and focused on issues such as international competitiveness (Chon and Mayer, 1995, Pearce, 1997) and destination choice. McKercher (1998) noted the effect of market access on destination choice, stating that more proximate destinations exhibited a competitive advantage over destinations that offered similar products but were less proximate. While these are significant factors determining the size of flows between countries, these concepts have yet to be integrated into a specific study of bilateral tourism.

Researchers have also investigated issues of destination competitiveness, including Ritchie and Crouch, 2000, Crouch and Ritchie, 1994, Crouch and Ritchie, 1995, Crouch and Ritchie, 1999, Poon, 1993, Kim (2001, cited in Dwyer 2001), Dwyer, 2001, Dwyer et al., 2000a, Dwyer et al., 2000b, Buhalis, 2000, and Hassan (2000). According to Dwyer “the issue of destination competitiveness is broad and complex: defying attempts to encapsulate it in universally acceptable terms” (2001:37), because competitiveness is both relative and multidimensional. As a consequence, no clear definition or model has emerged.

Limited analysis of international flows have been developed by Leiper, 1989, Pearce, 1995, Oppermann, 1999a, Coshall, 2000 and Thurot (1980). Analysis of cross-border tourism by Timothy, 1995a, Timothy, 1995b, Timothy, 1998, Timothy, 2000 found that physical barriers such as fortifications and demarcation markers, the severity of crossing formalities (visas, customs procedures, and quarantine measures), and psychological barriers that include cultural differences, and perceptions of safety and economic factors, all influence bilateral flows. The role of government is a recurrent theme in many studies. Geographers have identified distance, demographics, cost, and lack of information as the main variables influencing the volume of flows. Geographical concepts used to explain international flows include distance decay, gravity models, spatial hierarchy, origin-destination models (Thurot, 1980, Lundgren, 1982), and reciprocity (Pearce 1995). While these models offer a descriptive primarily spatial analysis of tourism, other issues, including political considerations and economic constraints, are largely ignored. As a consequence, existing models have failed to systematically analyze the entire spectrum of factors involved in the authorization, operation, and conduct of international tourism, particularly from a bilateral perspective.

Factors contributing to destination choice have received considerable attention in the literature (Chon, 1990, Mansfeld, 1992, Oppermann, 1999a), although the structures that facilitate tourism have received little. Mansfeld (1992) suggested a conceptual model of destination choice, while Crompton and Ankomh (1993) examined the proposition of choice sets in destination selection. Other researchers looking at this issue include Woodside and Lysonski, 1989, Um and Crompton, 1990, and Chon (1990). Furthermore, push and pull factors have been cited as explanations for motivation and destination selection (Dann, 1977, Laws, 1995, Josiam et al, 1999, Godfrey, 1999, Klenosky, 2002). As each destination in any bilateral pair will have only a limited number of potential pull factors, individual destinations may encounter difficulties in attracting tourists from the other country in the bilateral relationship.

Multilateral flows have some implications for understanding bilateral tourism. Pearce (1995) referred to this type as circuit tourism, with the concept illustrated in a model developed by Thurot (1980). The extent of circuit tourism is often difficult to estimate, as many countries do not require every country visited on a specific journey to be listed in immigration or visa documentation.

The literature review found that demand relies on the interaction of a large range of factors that include price, personal preferences, destination image, government regulations, personal financial capacity to travel, international political/military tensions, health epidemics, concerns for personal safety, and fear of crime. While these issues are explored in some detail in the literature, less research has been undertaken into the structures that facilitate the operation of bilateral tourism. Its structure and operation can be explained by two groups of elements. The first includes a number of conceptual processes explained by theories such as push-pull, distance decay, and destination competitiveness. The second centers on the structure of bilateral tourism and includes the public and private sectors, linkages, and economic and noneconomic factors.

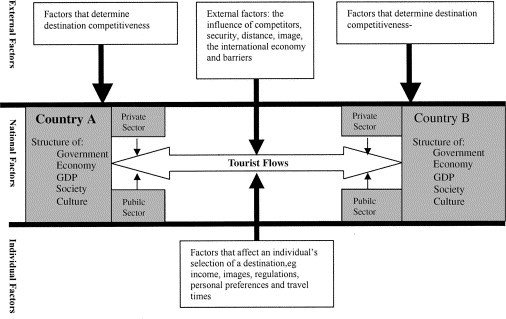

Based on these findings, Figure 1 was developed to model the flows and factors involved. Table 1 categorizes the major public and private sector factors as well as the economic and noneconomic factors that constitute the structure of bilateral tourism. The categories are not mutually exclusive, because there may be overlaps between the government and private sectors in the provision of tourism specific goods and services and spill over effects among the different categories of factors. In addition, some jurisdictions may choose to enact legislative frameworks to control or regulate specific areas of tourism activity, while others may choose to leave these areas to the market or simply ignore them altogether. It was also apparent that the factors affecting flows from Country A to Country B might not affect the opposite flow. The range of factors involved is outlined in Table 1. While not exhaustive, it does illustrate their range and complexity.

Figure 1.

Structure of Bilateral Tourism

To understand the significance of each of these factors it is necessary to employ evaluative theories including distance decay, push-pull, destination competitiveness, and so on. Although not pursued in this paper, theories of this nature clearly do not apply to every factor listed in Table 1. However, it is also apparent that a deeper understanding of the significance and role of these factors will be possible when each is examined by a battery of theories.

Government Responsibilities

The manner in which governments manage the domestic economy and external relations may significantly influence the size and structure of bilateral relationships. Factors operating at the government level can be subdivided into a number of categories, including diplomatic, policy, marketing, regulatory regimes, and the supply of goods and services. Tourism requires diplomatic recognition to facilitate the issue of visas (if required), recognition of passports, operation of transport modes, and recognition of civil rights. Deterioration in diplomatic relations between country pairs can reduce tourism, while improvements may have the opposite effect. The significance of diplomatic relations was noted by Krohn and O’Donnell (1999) and Butler and Mao (1996). Mok and Lam (2000) observed that restoration of diplomatic relations between the United States and Vietnam in 1995 was regarded by many Vietnamese as the return of commerce and tourism. War is also a significant factor and during the Falklands War between the United Kingdom and Argentina in 1982, tourism between the two warring nations ceased and took a long time to return to pre-war levels.

Deterioration of the United States relations with Cuba, after its 1959 revolution, reveals the extent to which poor diplomatic relations can affect flows. Prior to the revolution about 350,000 Americans visited Cuba anually, but this fell to virtually zero by 1962 and has remained at that level to date. The impact of the US embargo devastated the Cuban tourism industry for decades, with high spending Americans being replaced by a small number of frugal East Europeans from the Warsaw Block (Martin de Holan and Phillips 1997), before tourism returned to prosperity during the 90s based on a rising number of European tourists. Krohn and O’Donnell (1999) have observed that a relaxation of the US embargo would further reinvigorate the Cuban industry as well as stabilize tourism in other Caribbean countries.

Government policy may also be a significant factor in restricting both outbound and inbound flows (Hall 1994). Policies to restrict the former may include limiting who can travel (Ahmed and Krohn 1990), limiting the amount of currency taken out of the country (Edgell 1990), and limiting the value and quantity of goods imported by returning tourists (Ascher 1984). In a study of restrictions on outbound expenditure, Davila, Asgary, de los Santos and Vincent (1999) examined the effects of government restrictions by Mexican tourists in the United States and concluded that lowering duty-free limits made little difference. Inbound tourism may also be restricted by governments in an effort to prevent overstays by certain groups of tourists. Policy measures commonly employed by governments include restrictions on the issue of visas, proof of a return ticket, and evidence of sufficient funds to pay for living expenses while in the country.

Without government approval, citizens may not be entitled to visit other countries as a matter of right. Citizens of North Korea, for example, cannot leave the country unless it is for some specifically approved government purpose. In the People’s Republic of China, many citizens continue to face restrictions without prior government approval. But this restriction is being gradually lifted with the broadening of the Approved Destination Scheme (Zhou, King and Turner 1998). Until 1989 some classes of citizens of South Korea and Taiwan (particularly males of military age) were not allowed to leave the country without prior government approval.

The impact of these types of policy may be to restrict tourism in one direction only. Again citing the People’s Republic of China, the United States imposes few restrictions on citizens visiting China, but they may not necessarily be granted approval to visit. Chinese citizens are neither entitled to visit the United States without some form of Chinese government approval nor automatically granted visas to enter.

Problems resulting from illegal immigration and persons overstaying visas are sometimes cited by governments as reasons for imposing strict entry controls enforced through the selective issuing of visas. In Australia, strict entry laws require that applications for visas be approved prior to arrival. To prevent overstaying and illegal immigration, a risk-factor list was established which in 2000 listed Greek women between 20 and 29 and over 50, Russians, Chinese, Thai, and Indian nationals as having a high risk factor. The effect of this policy is illustrated by the success rate of visa applications in 1999 when immigration authorities refused visas to 26.7% of Russian applicants compared to only 0.07% from the United Kingdom (Madigan 2000). Similar restrictions are not usually applied to Australians tourists visiting India, Greece, and Thailand.

Bilateral transport policy is also an important factor. It includes the operation of transport modes between countries, operation of terminal facilities, border crossing facilities (Timothy 1998), and bilateral air service agreements. The latter usually include a number of conditions that impose limits on the ports serviced, service frequencies, and passenger numbers (Hanlon 1996). Pender (2001) observed that the bilateral monopolies of two national airlines at either end of a route could severely curtail competition, unless other airlines can operate 5th Freedom services. Conversely, liberalization of air services often stimulates bilateral flows as has occurred within the European Community (Pender 2001).

Usually employed as a measure to reduce the outflow of foreign exchange, currency restrictions may limit outbound tourism, even in the absence of other restrictions such as passport regulations (Bull 1995). Although there was some relaxation of currency restrictions on Chinese citizens after the RMB (national currency) became a convertible currency in 1996 (Zhou, King and Turner 1998), they were still restricted to a $2,000 currency limit in 2003. Exchanging RMB for other currencies in Hong Kong and other centers often circumvents this limit. Other countries that retain currency restrictions include North Korea and Cuba.

Not all national governments undertake destination marketing, either because of budgetary restrictions or in the belief that promotion is the responsibility of the private sector (Chamberlain 2000). The US federal government, for example, transferred responsibility for promotion to individual state governments and the private sector after ceasing promotion funding for its Travel and Tourism Administration in 1995, in the belief that promotion should be a function of the private sector. Bilateral tourism may reduce the need for extensive promotion if there is already considerable knowledge of the other country as found in North America between Canada and the United States and between the latter and Mexico.

The efficiency and effectiveness of government policy is often an important factor in the development of bilateral and multilateral tourism. Casado (1997) noted that there was a need for the Mexican government to introduce proactive measures to create conditions of security and safety that would attract foreign tourists. To achieve this, Casado recommended pacification of rebellious regions, eradicating narcotic traffic, and suppressing corruption.

The role of government includes the organization of government tourism departments, taxation policies, foreign investment and ownership policies, planning policies, law enforcement, and provision of education. Government regulatory regimes and their impact on the private sector are also major factors. Regulations of this nature include qualitative and quantitative controls over the wide range of private and public sector organizations that supply goods and services to the tourism industry (Hall 1994).

Governments also supply a range of goods and services to the tourism industry, including provision of many types of physical infrastructure, maintenance of public health, provision of security, education of the workforce, and, in many countries, the provision of commercial services. Tourism may suffer if government funding of these services is insufficient to maintain internationally competitive standards. In India, Ragurman (1998) observed the low level of inbound tourism is a direct result of the failure of government to allocate resources to the development of tourism infrastructure, some of which is federally owned.

Many national governments recognize that economic policy is a significant factor in encouraging international tourism. Mexico (Casado 1997) and Cuba (Martin de Holan and Phillips 1997) are two of numerous examples of governments that have allocated scarce financial resources to developing specific infrastructure on the basis of tourism plans incorporating specific economic policies. Policy instruments that may affect tourism include interest rates, anti-inflation policies, exchange rate controls, and the impact of indirect taxation.

Private Sector Factors

The structure and efficiency of the private sector exert considerable influence over the strength of bilateral flows, in addition to the level of investment in infrastructure and domestic price levels. Specialist functions undertaken by the private sector include inbound and outbound travel operations, retail services undertaken by travel agents, wholesale travel services, travel insurance, and transport services in both physical and cyberspace. The structure of this system varies substantially among countries, and both the structure of the national industry and the recommendations of agents (Klenosky and Gitelson 1998) can influence tourism. For example, Icoz, Var and Kozak (1998) observed that inbound flows to Turkey vary significantly with the number of travel agents operating in generating countries. In a study of outbound tourism from Korea to Australia, King and Choi (1999) noted that travel agents exerted a strong influence on destination choice by Koreans, while Oppermann (1999b) observed that although a significant component of tourism, the role of travel agents has been largely ignored in the literature. Buhalis (2000) noted that access to web travel sources was becoming an important factor in destination selection and inferred that destinations ignoring the Internet will suffer a decline in tourism. Therefore, it is apparent that for some nations the structure of the marketing infrastructure in generating countries may be the critical factor in increasing the competitiveness of the destination country.

Domestic price levels are influenced by the efficiency of the private and public sectors, and changes in domestic price levels may reduce a nation’s competitiveness and have a flow-on effect. Examples include a higher inflation rate than the other country in a bilateral relationship, changes in price levels caused by changes to wage and taxation levels, and changes in exchange rates. In the bilateral relationships between Australia and all other countries, the imposition of a 10% general sales tax in July 2000 on most goods and services in Australia, but not on overseas airfares, reduced the country’s competitiveness. This change may discourage international arrivals because of the increase in price and encourage the substitution of domestic for international tourism to cheaper foreign destinations. Factors of this nature can have a significant impact on destination selection (Crouch 1994).

Intangible Factors

Apart from public and private sector considerations, there are a range of factors that relate to the built and natural environments, as well as destination image, lifestyle, barriers to flows, and culture. These are grouped under the heading of intangible factors, a reference to the difficulties often encountered in measuring them. The quality of a country’s attractions may stimulate demand by enabling tourists to experience different cultures, participate in new experiences, visit national cultural and heritage icons, view unique flora and fauna, sample exotic cuisine, and shop for products not readily available domestically. National attractiveness is also an important factor, as, in a study of Korea, Kim (1998) found that the concept of overall destination attractiveness could be a positive motivator in tourism decisions. Similarly, authenticity is a significant factor often packaged by tour operators to promote products for specific destinations (Silver 1993). In a study of destination attractiveness based on Australia, Greece, Hawaii, France, and China, Hu and Richie (1994) found that scenery ranked first followed by climate, accommodation supply, prices, history, and attractions.

Icons have a significant role in promoting flows from specific bilateral partners. For example, Australia promotes a number of tourism icons, including the Great Barrier Reef, ocean beaches, Ayres Rock, unique fauna, the Sydney Opera House, and Aboriginal culture. However, what may be regarded domestically as a national icon may not attract similar interest from international arrivals. Thus, while Australia’s climate and beaches may be highly regarded by Japanese, Americans can experience similar weather and beaches domestically and may need to be enticed by other experiences and icons.

Images are also used by national tourism organizations and tour operators as a means of shaping tourism motivations (Milman and Pizam 1995), and according to Silver (1993) are also a means of providing tourists with an insight into the places that they are considering visiting. In a study of Amsterdam, Dahles (1998) observed that image might be a major attraction and notes that Amsterdam’s recent fall in popularity may require a more process-oriented approach to cultural tourism in the future. In terms of bilateral flows, changing cultural, social, and economic values in each partner country may lead to changes in destination image and affect tourism. Deterioration in bilateral relations, discussed previously, may also cause shifts in image from favorable to unfavorable, causing a decline in reciprocal flows that will only be repaired as relations improve.

In an examination of disruptions to inbound and outbound tourism to Indonesia over the period 1997–2002, Prideaux, Laws and Faulkner (2003) noted that a number of barriers could be identified, including inhibiting factors described as events in the generating country which reduce the outflow of tourists to all destinations; diverting factors described as disruptions to existing patterns perhaps by lower prices at competing destinations; and repelling factors described as disasters and crises such as civil unrest and natural disasters that repel arrivals from all origin countries. To these factors can be added other barriers such as war and government restrictions on individuals entering or leaving a country, visa controls applied to specific groups within a society and those created through restrictions imposed on bilateral air service agreements, and other transport agreements.

In a study of cross-cultural differences, Reisinger and Turner (1997) found that cultural differences (including the image of self, personal demeanour, and dietary habits) existed between Indonesian tourists and their Australian hosts and suggested that these factors should be considered when developing products and services for specific generating countries. A destination’s reputation may also be a significant factor in determining the volume of bilateral flows. Thailand’s reputation as a destination that exhibits an exotic culture and an easygoing lifestyle is attractive to Westerners. Similarly, Australia’s reputation, as a friendly country hospitable to international tourists, may be a factor in encouraging tourism; other intangible factors include attitude of hosts, political factors, and the role of the media.

Economic Factors

A range of economic factors also influence the level of arrivals and departures between bilateral partners. These factors include efficiency of the national economy, competition, exchange rates, national income levels, and elasticity of demand. An efficient economy will result in lower prices for goods and services, while an inefficient economy will produce the opposite effect. Measures of national economic efficiency include the cost of utilities, such as communications, energy and water, cost of financial services, domestic transport costs, level of tariff protection, level of government ownership of commercial enterprises, and the level of GDP growth per person per annum. As national economic efficiency improves, the demand of outbound tourism may rise (Bull 1995). This may also enhance international competitiveness, thereby stimulating inbound flows.

The ability of one country to attract tourists from another is often determined by international competitiveness. Faulkner, Oppermann and Fredline (1999) argued that there is increasing recognition of the need to evaluate the competitiveness of destinations as part of strategic positioning and marketing plans. During the Asian Financial Crisis, Australian outbound flows to Indonesia grew by 19.6% between 1997 and 1998 when the value of the Indonesian rupiah collapsed (Prideaux 1998). Conversely, Indonesian arrivals fell by 20% in the same period (Tourism Forecasting Council 2000). Hsu (2000) found that arrivals from Taiwan to Australia remained static between 1995 and 1999 in spite of an overall substantial rise in Taiwanese departures because Australia was perceived by Taiwanese to be as an expensive destination compared to North America and Asia.

Shifts in exchange rates caused by external factors such as regional or global economic crises and wars can have a significant impact (Lim 1997; Tribe 1995). The effect of changes to exchange rates is demonstrated by the trends in bilateral flows between Australia and Thailand during the Asian Financial Crisis. Australian arrivals grew by 9.9% in 1997 and 52.8% in 1998, while Thai arrivals fell by 22.9% in 1997 and a further 28.4% in 1998 (Australian Tourist Commission 1999). Shifts in the exchange rate between bilateral partners will influence the volume of flows as illustrated in the preceding example.

Beyond such national shifts, changes that occur to consumers’ personal income may alter their purchasing intentions and/or habits. If the cost of travel to a destination increases without a parallel increase in personal income, there may be a change in consumer purchasing habits and preferences. According to standard economic theory (McTaggart, Findlay and Parkin 1999a), if purchasers of services, in this case tourism, have a choice between obtaining domestic services or foreign services, they will compare prices. Other things remaining constant, the higher the foreign price or the lower the domestic price the greater is the propensity for the purchaser to purchase domestic goods. This will also occur in a situation where the purchaser is experiencing a depreciation of their currency relative to the currency of the bilateral partner. Tourism expenditure is also relatively price sensitive (Bull 1995) and can be measured by expenditure elasticity of demand described as the amount of change in purchasing power of a specific good such as tourism in proportion to the increase in prices charged for that good.

Elasticity of demand is another economic factor that may be significant in some bilateral relationships. The higher the rate of change in demand caused by a shift in price the more elastic the product is. The degree of elasticity depends on a number of factors, including the ease one product or service can be substituted for another, the proportion of the consumer’s income spent on the product or service, and the elapse of time from the change in price. The substitution effect refers to the tendency of consumers to substitute one product for another, in this case destinations, due to a number of factors that may include changes in the elasticity of demand, shifts in price, and a desire to try new products or experiences (Tribe 1995). Economic theory states that the closer the substitutes are for a service or product, the more elastic is the demand for those services or products (McTaggart, Findlay and Parkin 1999b). During the Asian Financial Crisis, the value of the Korean won fell in relation to other countries not affected by the crisis. As a consequence, travel to Australia, and other countries not affected by the Asian Financial Crisis, became relatively more expensive for Korean consumers, who turned to domestic destinations as a substitute causing outbound flows to fall by 32.5% in 1998. Conversely, as the value of the Korean won fell, overseas consumers were encouraged to substitute Korea for other destinations, resulting in a shift from negative growth in 1996 (−1.8%) to positive growth of 6.1% in 1997 and 8.8% in 1998. The elasticity of demand and propensity to substitute among destinations are important factors that need to be included in any assessment of bilateral tourism markets.

External Political and Health Factors

Often, political factors arise that are beyond the ability of countries to control. Examples include wars, terrorism, and the state of international relations. More recently, in 2003, health emerged as a major factor when there was considerable alarm over the spread of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) from China via Hong Kong to other nations.

Terrorism presents a major challenge to the tourism industry, because of its vulnerability to political violence (Sonmez and Graefe 1998). In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attack on the United States, international tourism declined between many nations even where they had not been linked to any terrorist threat. Following the October 2002 terrorist attack in Bali, tourism between Australia and Indonesia fell because of the fear of further attacks. Measures to reassure tourists of destination safety will become increasingly important as the perceived level of safety becomes a factor in destination selection. After the Bali bombings, Australians switched to safe destinations such as Fiji, New Zealand, and North Asia. Surprisingly, Fiji, only several years before had been subject to adverse Australian government travel advisory notices following an attempted coup and had suffered a 60% decline in Australian inbound tourism. But when the advisory notice was lifted, the industry quickly recovered. In a similar observation, Cothran and Cothran (1998) noted that the remarkable potential of the Mexican tourism industry was at risk because of growing political instability.

Aside from the strength of bilateral relations at economic, cultural, and diplomatic levels, other events and forces that operate within the international economy can also affect the volume of flows between country pairs. During periods of warfare, international tensions and economic uncertainty, flows may be affected. Clements and Georgiou (1998) noted the impact of political instability on UK arrivals in the Republic of Cyprus during the crisis with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in 1997 over the purchase of Russian-made surface-to-air missiles. In another example, during the 1991 Gulf War, 36,000 international flights were cancelled in the period January to February 1991 (WTO 1991). Other examples of international uncertainty impacting on flows include the Asian Economic Crisis and the Oil Shocks of 1974 and 1979. Similarly, the Palestinian uprising against Israeli in October 2000 resulted in a rapid fall in inbound flows to Israel. Even the threat of uncertainty can cause difficulties. In 2003 the uncertainty of Iraq’s response to a US led invasion caused a decline in forward bookings from Japan to the United States.

Advances in medicine and improvements to public health in most countries during the 20th century reduced the danger of many infectious diseases, such as typhus, polio, typhoid, and malaria (Prideaux and Master 2001). Dangers from other diseases have been reduced by medical science. However, AIDS emerged as a pandemic in the later 80’s and was spread globally by tourists. In 2003, SARS, a previously unknown form of flu-like disease, appeared in Southern China and spread to Hong Kong and later Canada. Widespread and sensationalized publicity of the impact of SARS and its comparison to the 1918–19 Spanish flu pandemic which killed an estimated 18 million people (Lemonick 2003) had a significant impact on arrivals and departures in China, Hong Kong, and other countries where the disease was reported. As a consequence of the uncertainty generated by SARS, Hong Kong hotels experienced a vacancy rate of 80% in April 2003 (Carmichael 2003).

Measurement of Bilateral Tourism

At its simplest level, bilateral tourism is limited to describing the patterns of departures and arrivals between two countries; however, to gauge its full extent, other measures should be considered. These might include yield expressed as bed nights, revenue flows, and the composition of tourist types. For example, the majority of Australian arrivals in Korea in 1996 were aircrew and apart from limited bed nights, arrivals of this nature have little impact on other sectors of the industry.

A further method of analysis, the Outbound Visitor Flow Ratio, measures the percentage of a country’s population that visit a specific destination in any given year. This is illustrated by comparing the number of Singaporean arrivals in Australia as a percentage of its population compared to Australian arrivals in Singapore measured on a similar basis. In 1999, 0.77% of Australia’s total population visited Singapore while the flow in the other direction was 5.8%. This analysis can be further developed by segmenting arrivals by purpose (including pleasure, business, and education), or by measuring changes longitudinally. Taking the example of Singapore, it is apparent that Australia has been far more successful in attracting Singaporeans than the other way around as a percentage of population. Further, this analysis may signal that Australia could experience future decline in what appears to be a relatively mature market if Singaporeans look to new and unfamiliar destinations. For Australia, this type of analysis should signal the need to closely examine how sustainable Singaporean repeat business will be in the future, as well as indicating the need to develop new Australian products and destinations that will encourage a continued high level of Singaporean repeat tourism.

Further understanding of the structure of bilateral tourism might be achieved through the use of appropriately modified models, including Butler’s (1980) tourism area lifecycle model and Prideaux’s (2000) resort development spectrum model to identify market profiles and indications of possible future decline in international flows. Other ways to measure changes include Neo-Fordist, Post-Fordist (Torres 2001), and Postmodernist interpretations (Urry, 1990, Urry, 1995) of possible shifts from standardized production and consumption of mass tourism experiences to mass niche, specialized or individualized tour consumption. When models and interpretations of this type are applied in conjunction with the outbound visitor flow ratios there is scope to develop diagnostic tools for application to tourism policy. The previous illustration of the inability of Korea to boost Australian arrivals, because of a misunderstanding of the Australian market, is another tool. This, combined with a modified tourism area lifecycle model, the resort development spectrum model, or perhaps a Post-Fordist/Postmodernist interpretation of demand, may be used to develop destination marketing strategies and policies. It may also be useful to employ the bilateral framework shown in Table 1 to evaluate elements of tourism as illustrated in Table 2 . In this example, positive and negative effects of specific factors of government responsibilities are highlighted and possible corrective actions to reduce negative factors are outlined in the Australia to Indonesia component of their bilateral tourism. While Table 2 only considers government responsibilities, any comprehensive analysis must also include all other elements of the bilateral framework as discussed.

Table 2.

Example of a Framework for Evaluating Bilateral Tourism

| Flow From Country A to Country B | Positive Effects | Negative Effects | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Responsibilities | |||

| State of Diplomatic Relations | Nil | Often poor | Diplomatic initiatives needed to increase destination attractiveness |

| Currency | Reduced value of Rupiah stimulated tourism | Nil | Not required to attract tourists but needed to stimulate the domestic economy |

| Promotion | Nil | Promotion ceased | Need for government funding to reverse falling visitor numbers |

| Government Regulations including crime and national park protection | Nil | Non enforcement created poor national image | Action required to reduce corruption and increase internal security |

| Security | Nil | Uncertainty about tourist security during the 1997 Jakarta riots and 2002 Bali bombings | Enhance security required in tourism areas to ensure the safety of tourist |

| Economic Policy | Nil | Poor, created impression of poorly run country | Need to introduce new economic policies (Indonesia appealed to IMF for assistance) |

Note: This example only examines the government responsibilities of the bilateral framework outlined in Table 1, whose factors require a comprehensive consideration of all factors outlined in Figure 2.

Table 2 is an example of a simple diagnostic test or checklist that may be employed to examine tourism flows. Prideaux, Laws and Faulkner (2003) identified ten major shocks to Indonesia’s tourism industry during the period 1996 to 2002 that impacted on the inbound tourism from Australia. Many of these emanated from difficult internal political and economic conditions in Indonesia, which led to severe fluctuations in the level of Australian arrivals. The August 2003, terrorist bombing of the JR Marriott Hotel in central Jakarta further illustrates the need for greater security of tourists identified in Table 2.

The previous discussion illustrates the relationship among the various factors comprising the structure of the framework outlined in Figure 1. Its use for a more detailed analysis will further highlight linkages between specific factors that uniquely influence the pattern of flows between specific country pairs. For example, Australians have little difficulty obtaining visas for Thailand, but Thais face a much more rigorous process because of concern about tourists who overstay or who enter the country to work illegally. In these circumstances, reducing visa restrictions may encourage additional arrivals, although there may be an associated cost of apprehending and deporting Thais who overstay. The possible net benefit to Australia may be measured by comparing the increase in receipts from additional Thai arrivals against the cost of enforcing length of stay regulations. Similarly, the framework (Table 1) is a useful tool to broaden the analysis of issues that govern origin-destination studies and when applied as in Table 2 may reveal relationships and impediments not previously identified.

Conclusion

Although a significant component of international arrivals and departures, bilateral tourism has not been studied in detail. Given the increasing significance of tourism exports and imports and the reduced ability of governments to unilaterally impose trade barriers, an understanding of the bilateral nature of international flows is important. While this research has been able to develop a clearer understanding of the structure of bilateral flows, the multifaceted and multisector nature of the industry means it is not always possible to clearly delineate responsibility for all factors.

Understanding the mechanisms that facilitate the flows between country pairs enables the identification of barriers and/or developmental possibilities that may have otherwise been overlooked. Moreover, inefficiencies may be identified and remedial action initiated. A further benefit may also be the realization that unequal bilateral flows are not always symptomatic of structural weaknesses in national industries, but may also result from other factors related to population size, national GDP levels, and issues related to destination competitiveness.

Further research in this area should be directed towards testing the suggested framework by applying it to specific bilateral pairs to identify deficiencies and previously hidden marketing opportunities. This may include application of the tourisim area lifecycle and/or the resort development models and investigating changes in the outbound visitor flow ratio perhaps caused by change in consumer demand from societies entering Post-Fordist or postmodern periods of development. Considerable scope also exists to apply this analysis to multinational tourism structures.

Biography

Bruce Prideaux is Professor of Marketing and Tourism Management at the School of Business, James Cook University (PO Box 6811 Cairns 4870, Australia. Email <bruce.prideaux@jcu.edu.au>). His research interests include issues in destination development with a particular interest in development models, tourism transport, heritage, crime, cybertourism, and development in Asia, with a particular emphasis on Korea and Indonesia.

Submitted 14 December 2000. Resubmitted 8 January 2003. Resubmitted 16 June 2003. Resubmitted 13 November 2003. Accepted 11 April 2004. Final version 15 December 2004. Refereed anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Egon Smeral

References

- Ahmed Z., Krohn F. Reversing the United States’ Declining Competitiveness in the Marketing of International Tourism: A Perspective on Future Policy. Journal of Travel Research. 1990;29(2):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher B. Obstacles to International Travel and Tourism. Journal of Travel Research. 1984;22(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Tourist Commission . Australian Tourist Commission; Sydney: 1999. Tourism Pulse. No. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Bull A. 2nd ed. Longman; Melbourne: 1995. The Economics of Travel and Tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis D. Tourism in an Era of Information Technology. In: Faulkner B., Moscardo G., Laws E., editors. Tourism in the 21st Century: Lessons from Experience. Continuum; London: 2000. pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R. The Concept of a Tourist Area Resort Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Canadian Geographer. 1980;14:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R., Mao B. Conceptual and Theoretical Implications of Tourism between Partitioned States. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 1996;1:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Casado M. Mexico’s 1989–94 Tourism Plan: Implications of Internal Political and Economic Stability. Journal of Travel Research. 1997;36(1):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain K. Asia Pacific. In: Lockwood A., Medlik S., editors. Tourism and Hospitality in the 21st Century. Buterworth and Heinemann; Oxford: 2000. pp. 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Chon K. The Role of Destination Image in Tourism: A Review and Discussion. Tourism Review. 1990;45:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chon K., Mayer K. Destination Competitiveness Models and Their Application in Las Vegas. Journal of Tourism Systems and Quality Management. 1995;1:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Clements M., Georgiou A. The Impact of Political Instability on a Fragile Tourism Product. Tourism Management. 1998;19:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton J., Ankomh P. Choice Set Propositions in Destination Selection. Annals of Tourism Research. 1993;20:461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch G. Demand Elasticities for Short-Haul Versus Long-Hall Tourism. Journal of Travel Research. 1994;23(2):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch G., and J. Ritchie 1994 Destination Competitiveness: Exploring Foundations for a Long-Term Research Program. Proceedings of the Administrative Sciences Association of Canada Annual Conference, pp. 79–88, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

- Crouch G., J. Ritchie 1995. Destination Competitiveness and the Role of the Tourism Enterprise. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Business Congress, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Crouch G., Ritchie J. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. Journal of Business Research. 1999;44:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Coshall J. Spectral Analysis of International Tourism Flows. Annals of Tourism Research. 2000;27:577–589. [Google Scholar]

- Cothran D., Cothran C. Promise or Political Risk for Mexican Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Dahles H. Redefining Amsterdam as a Tourist Destination. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:55–69. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore L. Tourism-The World’s Peace Industry. Journal of Travel Research. 1988;27(1):35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dann G. Anomie, Ego-enhancement and Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 1977;6:184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Davila V., Asgary N., de los Santos G., Vincent V. The Effects of Government Restrictions on Outbound Tourism Expenditures. Journal of Tourism Research. 1999;37:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L. 2001 Destination Competitiveness: Development of a Model with Application to Australia and the Republic of Korea. Canberra: Department of Industry Science and Resources.

- Dwyer L., Forsyth P., Rao P. The Price competitiveness of Travel and Tourism: A Comparison of 19 Destinations. Tourism Management. 2000;21:9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer L., Forsyth P., Rao P. Sectoral Analysis of Price Competitiveness of Tourism: An International Comparison. Tourism Analysis. 2000;5:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell D. Von Nostrand Reinhold; New York: 1990. International Tourism Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner B., Oppermann M., Fredline E. Destination Competitiveness: An Exploratory Examination of South Australia’s Core Attractions. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1999;5:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey K. Attributes of Destination Choice: British Skiing in Canada. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1999;5:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon P. Butterworth; Oxford: 1996. Global Airlines Competition in a Transnational Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S. Determinants of Market Competitiveness in an Environmentally Sustainable Tourism Industry. Journal of Travel Research. 2000;38:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson J., Ko G. Tourism and Politics: The Implications of the Change in Sovereignty on the Future Development of Hong Kong’s Tourism Industry. Journal of Travel Research. 1994;32(4):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M. 2000 Inbound Taiwanese Tourism in Australia. Unpublished Master Thesis. The University of Queensland.

- Hu Y., Richie J. Measuring Destination Attractiveness; A Contextual Approach. Journal of Travel Research. 1994;32(2):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Icoz O., Var T., Kozak M. Tourism Demand in Turkey. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari J. Tourism and Peace. Annals of Tourism Research. 1989;16:439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Josiam B., Smeaton G., Clements C. Travel Motivation and Destination Selection. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1999;5:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Perceived Attractiveness of Korean Destinations. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:340–361. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Crompton J. Role of Tourism in Unifying the Two Koreas. Annals of Tourism Research. 1990;17:353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.S., Prideaux B. Tourism, Peace, Politics and Ideology: Impacts of the Mt. Gumgang Tour Project in the Korean Peninsula. Tourism Management. 2003;24:675–685. [Google Scholar]

- King B., Choi H. Travel Industry Structure in Fast Growing but Immature Outbound Markets: The Case of Korea to Australia Travel. International Journal of Tourism Research. 1999;1:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Klenosky D. The “Pull” of Tourism Destinations: A Means-End Investigation. Journal of Travel Research. 2002;40:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Klenosky D., Gitelson R. Travel Agents’ Destination Recommendations. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn F., O’Donnell S. US Tourism Potential in a New Cuba. Journal of Travel and Tourism Research. 1999;38:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois S., Theodore J., Ineson E. Poland: In-bound Tourism from the UK. Tourism Management. 1999;20:461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Laws E. Routledge; London: 1995. Tourist Destination Management: Issues, Analysis and Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper N. Main Destination Ratios, Analysis of Tourism Flows. Annals of Tourism Research. 1989;16:530–542. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonick M. Will SARS Strike Here? Time. 2003;(April 14):72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. Review of International Tourism Demand Models. Annals for Tourism Research. 1997;24:835–849. [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. A Meta-Analysis Review of International Tourism Demand. Journal of Travel Research. 1999;37:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren J. The Tourist Frontier of Nouveau Quebec: Functions and Regional Linkages. Tourist Review. 1982;37:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan M. Tourists Face High Bar. The Courier Mail. 2000;(October 9):5. [Google Scholar]

- Master H., Prideaux B. Culture and Vacation Satisfaction: A Study of Taiwanese Tourists in South East Queensland. Tourism Management. 2000;21:445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson A., Wall G. Longman Scientific and Technical; New York: 1982. Tourism Economic, Physical and Social Impacts. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher B. The Effect of Market Access on Destination Choice. Journal of Travel Research. 1998;37:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart D., Findlay C., Parkin M. 3rd ed. Addison-Wesley; Melbourne: 1999. Micro Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld Y. From Motivation to Actual Travel. Annals of Tourism Research. 1992;20:399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Martin de Holan P., Phillips N. Sun, Sand and Hard Cruising Tourism in Cuba. Annals of Tourism Research. 1997;24:777–795. [Google Scholar]

- Milman A., Pizam A. The Role of Awareness and Familiarity with a Destination: The Central Florida Case. Journal of Travel Research. 1995;33(3):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A., Williams P. Attracting Japanese Tourists into the Rural Hinterland: Implications for Rural Development and Planning. Tourism Management. 1999;20:487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Mok C., Lam T. Vietnam’s Tourism Industry: Its Potential and Challenges. In: Chon K., editor. Tourism in Southeast Asia: A New Diction. Haworth; New York: 2000. pp. 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann M. Predicting Destination Choice: A Discussion of Destination Loyalty. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1999;5:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann M. Database Marketing for Travel Agencies. Journal of Travel Research. 1999;37:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce D. Longmans; Harlow: 1995. Tourism Today: A Geographic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce D. Competitive Destination Analysis in South East Asia. Journal of Travel Research. 1997;35(4):16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pender L. Continuum; London: 2001. Travel Trade and transport: An Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Poon A. CAB International; Walingford: 1993. Tourism, Technology, and Competitive Strategy. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B. The Impact of the Asian Financial Crisis on Bilateral Indonesian-Australian Tourism. In: Gunawan M., editor. Volume 2. Bandung Institute of Technology; Bandung: 1998. pp. 15–29. (Pariwisata Indonesia Menuju Keputusan Yang Lebih Baik). [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B. The Role of Transport in Destination Development. Tourism Management. 2000;21:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B., Laws E., Faulkner B. Events in Indonesia: Exploring the Limits to Formal Tourism Trends Forecasting Methods in Complex Crisis Situations. Tourism Management. 2003;24:475–487. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B., Kim S. Bilateral Tourism Imbalance: Is There a Cause for Concern: The Case of Australia and Korea. Tourism Management. 1999;20:523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B., Master H. Health and Safety Issues Effecting International Tourists in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism. 2001;6:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux B., Witt S. An Analysis of Tourism Flows between Australia and ASEAN Countries: An Australian Perspective. In: Chon K., editor. Tourism in Southeast Asia: A New Direction. The Horworth Press; New York: 2000. pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ragurman K. Troubled Passage to India. Tourism Management. 1998;19:533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger Y., Turner L. Cross Cultural Differences in Tourism Indonesian Tourism in Australia. Tourism Management. 1997;18:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger Y., Turner L. Cultural Differences between Asian Tourist Markets and Australian Hosts, Part 1. Journal of Travel Research. 2002;40:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J. Brent, Crouch G. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainability Perspective. Tourism Management. 2000;21:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Silver I. Marketing Authenticity in Third World Countries. Annals of Tourism Research. 1993;20:302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Sonmez S., Graefe A. Influence of Terrorism Risk on Foreign Tourism Decisions. Annals of Tourism Research. 1998;25:112–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sussmann S., Rashcovsky C. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of English and French Canadians’ Vacation Travel Patterns. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 1997;16:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy D. Political Boundaries and Tourism: Boarders as Tourism Attractions. Tourism Management. 1995;16:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy D. International Boundaries: New Frontiers for Tourism Research. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research. 1995;1:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy D. Cross-Border Partnership in Tourism Resource Management: International Parks along the US-Canada Border. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 1998;7:182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. 2000 International Boundaries: Barriers to Tourism, Unpublished paper.

- Thurot, J. 1980 Capacité de Change et Production Touristique. Etudes Touristiques: Aixen-Province.

- Torres R. Toward a Better Understanding of Tourism and Agriculture Linkages in the Yucatan: Tourist food Consumption and Preferences. Tourism Geographies. 2001;4:282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Forecasting Council . Tourism Forecasting Council; Canberra: 2000. Forecast. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe J. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 1995. The Economics of Leisure and Tourism Environments, Markets and Impacts. [Google Scholar]

- Um S., Crompton J. Attitude Determinants in Tourism Destination Choice. Annals of Tourism Research. 1990;17:432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Urry J. Sage; London: 1990. The Tourist Gaze. [Google Scholar]

- Urry J. Routledge; London: 1995. Consuming Places. [Google Scholar]

- Var T., Schluter R., Ankomah P., Lee Y-H. Tourism and Peace: The Case of Argentina. Annals of Tourism Research. 1989;16:431–434. [Google Scholar]

- Wanhill S. Issues in Public Sector Involvement. In: Faulkner B., Moscardo G., Laws E., editors. Tourism in the 21st Century Lessons from Experience. Continuum; London: 2000. pp. 222–242. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside A., Lysonski S. A General Model of Traveler Destination Choice. Journal of Travel Research. 1989;27:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- WTO Impact of the Gulf Crisis in International Tourism. Journal of Travel Research. 1991;30:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- WTO . World Tourism Organization; Madrid: 2002. Compendium of Tourism Statistics 2002 Edition. [Google Scholar]

- WTO . Vol. 2. World Tourism Organization; Madrid: 2003. (WTO World Tourism Barometer). [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. Travel between Politically Divided China and Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 1997;2:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. Tourism Across the Taiwan Straits. Tourism Management. 1993;14:228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., King B., Turner L. The China Outbound Market: An Evaluation of Currency Constraints and Opportunities. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1998;4:109–119. [Google Scholar]