Abstract

Background:

Left atrial (LA) longitudinal strain is a novel parameter used for the evaluation of LA function, with demonstrated prognostic value in several cardiac diseases. However, the extent of load dependency of LA strain is not well known. Our aim was to evaluate the impact of acute changes in preload on LA strain, side-by-side with LA volume, in normal subjects.

Methods:

We prospectively enrolled 25 healthy volunteers (13 men, age 31±2 years), who underwent 2D and 3D echocardiographic imaging during acute stepwise reductions in preload using a tilt maneuver: baseline at 0 degrees, followed by 40 and 80 degrees. Left ventricular (LV) and LA size and function parameters were measured using standard methodology, and LA strain time curves were obtained using speckle tracking software (TomTec), resulting in reservoir, conduit and contractile strain components. All parameters were compared between the three loading conditions using one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements.

Results:

Although there were no significant changes in blood pressure, heart rate increased significantly with tilt. As expected, LA volumes, LV volumes and LV ejection fraction, as well as E-wave, A-wave and e’ significantly decreased with progressive inclination. In parallel, LA reservoir, conduit and contractile strain values decreased with reduction in preload (reservoir: 42.9±3.9 to 27.5±3.8%, P<0.001; conduit: 29.3±2.7 to 20.2±5.0%, P<0.001; contractile: 13.6±2.9 to 7.3±3.5%, P<0.001). Paired post-hoc analysis showed that all LA strain values were significantly different between all three tilt phases. Of note, percent change in LA reservoir strain was significantly smaller than that in LA maximum volume.

Conclusion:

In normal subjects, LA strain is preload dependent, but to a lesser degree than LA volume. This difference underscores the relative advantage of LA strain over maximum volume, when LA assessment is used as part of the diagnostic paradigm.

Keywords: left atrium, atrial function, preload, tilt maneuver

Introduction

The left atrium plays a pivotal role in the filling of the left ventricle through its reservoir, conduit and contractile functions. In clinical practice, maximum left atrial (LA) volume is a simple measurement routinely used for the evaluation of left ventricular (LV) diastolic function and has well-known prognostic value in a number of cardiac disease states (1–5). However, LA volume is known to be influenced by loading conditions (6).

Recently, LA longitudinal strain has been suggested as an alternative measure of LA function, which can be obtained using commercial speckle tracking software tools, similarly to LV deformation parameters (7). These measurements have been shown to be feasible and reproducible (8, 9). More recently, LA strain has proven useful for the non-invasive evaluation of LV filling pressure (10–12), and shown to provide added value in the prognostication of patients with heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ischemic and valvular heart disease (13–15). Furthermore, recent publications of normal values of LA strain (16–18) are likely to advance the widespread utilization of this parameter in daily practice.

In contrast to the presumed load dependency of LV ejection fraction, LV strain has been postulated to be relatively independent of variations in loading conditions. However, recent studies have disputed this notion, underscoring that accurate interpretation of LV strain must be performed alongside with hemodynamic evaluation (19–22). Studies have shown that LA strain responds to preload alterations induced in patients with conditions known to reduce LA compliance. This included response to hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease (23), induction of anesthesia or changes in ventilator settings in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (24). However, the response of LA strain to changes in loading conditions has not been systematically investigated in normal subjects, in whom there are no potentially confounding effects of disease.

Therefore, the goal of our study was to define the physiological effects of alterations in preload on LA longitudinal strain in normal subjects. Specifically, we aimed to determine the magnitude of the response of LA strain to acute reductions in preload caused by postural changes in normal subjects, in comparison to the response of the most common clinically used parameter, namely LA maximum volume, measured by both two- and three-dimensional (2D and 3D) echocardiography.

Methods

Study design and population

We prospectively enrolled 25 healthy volunteers (13 men, age 31±2 years) at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Study subjects were recruited from staff members and selected on the basis of good quality of echocardiographic images and no known pathology, including cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, no chronic medication use and no cardiovascular risk factors. The acute reductions in preload were induced by postural changes with the inclination of a tilt table from a 0-degree baseline to two subsequent levels of 40 and 80 degrees. The study protocol consisted of echocardiographic imaging during each of the three tilt phases. Image acquisitions at 40 and 80 degrees were completed within 2 minutes after reaching the respective position. Heart rate and blood pressure were monitored throughout the study. The institutional review board approved the study, and all subjects gave informed consent.

Echocardiographic imaging and analysis

Echocardiographic imaging was performed by expert sonographers using iE33 imaging system (Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts) equipped with an X5–1 probe. All 2D acquisitions were optimized by adjusting gain, depth, compress and time-gain compensation. 2D imaging included apical 2- and 4-chamber views (4Ch and 2Ch), focused separately on the left ventricle and the left atrium, respectively. Pulsed-waved Doppler imaging of the trans-mitral flow at the tips of the mitral leaflets and tissue Doppler imaging of the septal and lateral mitral annular points were performed in the 4Ch view. After 2D imaging was completed, 3D full-volume datasets of the left ventricle and atrium were acquired using ECG-gating over 4 consecutive cardiac cycles. Frame rate was maximized by minimizing imaging depth and sector width, resulting in frame rates of at least 55 Hz for 2D images and 27 Hz for 3D datasets.

2D LA strain and 3D LA and LV volume measurements were performed offline using vendor independent software (2D Cardiac Performance Analysis and 4D Cardio-View, respectively; TomTec Imaging System, Munich, Germany) by an expert reader blinded to the tilting position and all prior measurements. 2D LA volumes were calculated using the biplane method of disks. 2D LA maximal and minimal volumes (maxVol, minVol) were measured at ventricular end-systole and end-diastole, respectively. 2D LA pre-A-wave volume (Pre-AVol) was measured at the onset of the EKG P-wave. 3D LA volume was measured throughout the cardiac cycle, resulting in a volume time-curve, from which LA maxVol and LA minVol were identified at the time points when the LA cavity was largest and smallest, respectively. 3D LA Pre-AVol was also obtained from the LA volume time-curve at the onset of the EKG P-wave. These volumes were used to calculate LA emptying fraction, including its total, active and passive components. Mitral E-wave, A-wave, E/A ratio and E-wave deceleration time (DT) were measured along with the mitral annular septal and lateral e’ velocity, which were averaged to obtain mean e’. E/e’ ratio was also calculated.

2D LA longitudinal strain measurements were performed by tracing LA border at end-systole in the LA-focused apical 4Ch view, taking care to exclude the appendage and pulmonary veins from the LA cavity. LA strain measurement throughout the cardiac cycle was set to start at the beginning of the QRS complex and a global LA strain time-curve was generated. LA reservoir strain (εR) was measured from the maximal inflection point on the LA strain time-curve, LA contractile strain (εCT) was measured at the onset of the EKG P-wave, and LA conduit strain (εCD) was obtained from the difference between LA εR and LA εCT (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left atrial strain-time curve for a single cardiac cycle with the reservoir, conduit and contractile strain measurements shown in yellow.

All measurements were repeated for all 3 tilt phases and compared between the phases. To allow comparisons between parameters in the magnitude of response to acute changes in preload, the changes in each parameter from the 0-degrees to the other two phases were expressed in percent of the baseline values of the corresponding parameter.

Reproducibility Analysis

LA strain measurements were repeated in all 25 study subjects by two readers for purposes of reproducibility analysis. This included repeated measurements by the same observer, at least two weeks later, as well as measurements by a second independent observer, both blinded to all prior measurements, as well as to the tilt phases. The repeated analyses were performed on the same pre-selected loops, but the reader was free to choose the cardiac cycle for measurement. Inter-and intra-observer variability were calculated as an absolute difference between the corresponding pairs of repeated measurements as a percentage of their mean and by intraclass correlation coefficients.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normal distribution of the quantitative variables was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For each parameter, differences between different tilt phases were tested using paired one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements. A post-hoc pairwise t-test analysis with Bonferroni’s correction for repeated hypothesis testing was performed for LA strain, when statistically significant differences were found within subject variance. Values of P<0.05 were considered significant. Confidence intervals were defined at the 95th percentile around the mean.

Results

Results are summarized in Table 1. Heart rate significantly increased during tilt maneuver. In contrast, no significant changes in blood pressure were noted. LV volumes and EF showed a significant reduction during progressive tilt for both 2D and 3D measurements. Mitral E-wave, A-wave and e’ also decreased from baseline, while E/e’ significantly increased with tilting.

Table 1.

Results are reported as Mean ± SD. P-value are from paired one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements. P<0.05 was defined as significant.

| 0° | 40° | 80° | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Parameters | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 118.7± 11.4 | 118.1± 12.8 | 117.5± 12.5 | 0.772 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.0± 8.0 | 75.5± 6.6 | 75.9± 5.9 | 0.052 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 87.5± 6.9 | 89.7± 6.4 | 89.8± 6.8 | 0.101 |

| HR (bpm) | 68.7± 11.4 | 72.4± 13.0 | 80.4± 13.8 | <0.001 |

| Left Ventricle | ||||

| 2D LVEDV (ml/m2) | 51.0± 7.9 | 42.5± 8.3 | 35.9± 6.9 | <0.001 |

| 2D LVESV (ml/m2) | 19.3± 3.4 | 16.7± 3.8 | 14.6± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| 2D LVEF (%) | 62.1± 4.1 | 60.6± 4.4 | 59.6± 3.3 | 0.012 |

| 3D LVEDV (ml/m2) | 51.3± 11.4 | 43.1± 9.2 | 37.1± 7.9 | <0.001 |

| 3D LVESV (ml/m2) | 19.0± 4.1 | 17.6± 4.2 | 15.8± 3.4 | <0.001 |

| 3D LVEF (%) | 62.7± 4.2 | 59.3± 3.5 | 57.4± 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Left Atrium | ||||

| 2D LAεR (%) | 42.9± 3.9 | 33.8± 5.3 | 27.5± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| 2D LAεCD (%) | 29.3± 2.7 | 23.0± 4.5 | 20.2± 5.0 | <0.001 |

| 2D LAεCT (%) | 13.6± 2.9 | 10.7± 3.7 | 7.3 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| 2D LA MaxVol (ml/m2) | 27.3± 6.1 | 15.2± 3.8 | 10.2± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| 2D LA Pre-AVol (ml/m2) | 14.3± 3.1 | 8.8± 2.5 | 5.5± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| 2D LA MinVol (ml/m2) | 9.6± 2.2 | 6.5± 2.1 | 4.3± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| 2D LA EF (%) | 64.2±6.5 | 57.1±7.7 | 58.0±11.3 | 0.003 |

| 2D LA Passive EF (%) | 47.3±6.9 | 42.1±7.2 | 48.±11.3 | <0.001 |

| 2D LA Active EF (%) | 32.2±7.6 | 26.1±8.8 | 22.2±12.3 | <0.001 |

| 3D LA MaxVol (ml/m2) | 28.7± 6.0 | 19.1± 4.8 | 13.8± 3.3 | <0.001 |

| 3D LA Pre-AVol (ml/m2) | 16.1± 3.7 | 11.0± 3.2 | 7.6± 2.1 | <0.001 |

| 3D LA MinVol (ml/m2) | 9.8± 2.6 | 7.1± 2.2 | 4.9± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| 3D LA EF (%) | 65.7±6.4 | 62.4±7.8 | 64.4±7.3 | 0.158 |

| 3D LA passive EF (%) | 43.9±7.5 | 42.3±8.8 | 44.5±9.6 | 0.561 |

| 3D LA active EF (%) | 38.8±8.4 | 34.5±10.9 | 35.2±11.4 | 0.221 |

| Mitral Inflow | ||||

| E wave (cm/s) | 86.7± 11.7 | 65.1± 10.0 | 60.7 ± 8.3 | <0.001 |

| A wave (cm/s) | 47.3± 8.6 | 40.2± 5.9 | 38.9± 5.2 | <0.001 |

| E/A | 1.9± 0.5 | 1.6± 0.4 | 1.6± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| DT (ms) | 197± 32.9 | 240± 48.8 | 229± 40.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean e’ (cm/s) | 15.7± 2.4 | 11.6 ± 2.0 | 9.3± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| E/e’ | 5.6± 0.9 | 5.7± 1.2 | 6.6± 0.9 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: 2D – two-dimensional, 3D – three-dimensional, SBP/DBP/MBP – systolic/diastolic/mean blood pressure, HR – heart rate, LVEDV/LVESV – left ventricular end-diastolic/end-systolic volume, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, LAεR – left atrial reservoir strain, LA εCD – left atrial conduit strain, LA εCT – left atrial contractile strain, LA Max/Pre-A/Min Vol – left atrial maximum/pre-atrial contraction/minimum volume, LA EF – left atrial emptying fraction, DT - deceleration time.

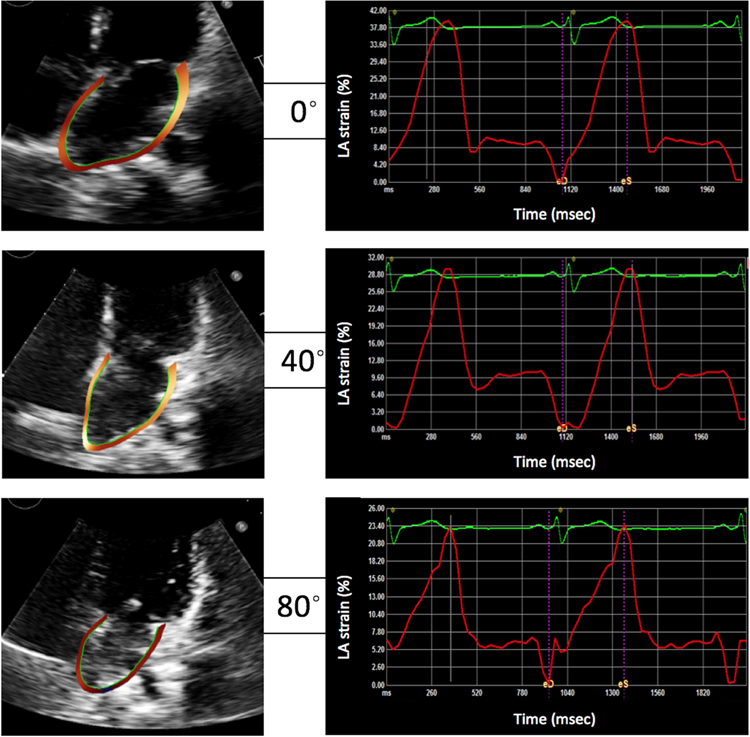

Figure 2 shows an example of LA-focused 4Ch images and the corresponding LA strain time curves obtained in one subject at all three tilt phases. This example depicts gradual decrease in LA volume (left, top to bottom) and in LA longitudinal strain (right). Figure 3 depicts the same consistent response to preload reduction in all 25 study subjects.

Figure 2.

Example of 2D echocardiographic images (left) and LA longitudinal strain curves (right) obtained in the same subject at 0-, 40- and 80-degree tilt positions.

Figure 3.

Changes in LA reservoir strain, 2D and 3D LA max volumes from baseline to 40- and 80-degree tilt positions in all 25 study subjects.

The decrease in LA volumes with tilting was significant for both 2D and 3D measurements, including maximum, minimum and pre-A-wave volumes (Table 1). Left atrial εR, εCT and εCD also showed a significant reduction with tilting (Table 1). Paired post-hoc analysis showed that all LA strain values were significantly different between all three tilt phases, demonstrating a stepwise response (Table 2). Of note, LA emptying fraction measured by both 2D and 3D showed a decrease from 0 to 40-degree position, but then went back up at 80 degrees. These changes were statistically significant for 2DE, but not so for 3DE analysis.

Table 2.

Post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni’s correction for LA strain values between the three tilt positions (0, 40 and 80°). P<0.05 was defined as significant.

| Difference between phases [CI] | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LAεR (%) | 0°→40° | 9.1 [6.5 – 11.7] | <0.001 |

| 0°→80° | 15.4 [13.3–17.6] | <0.001 | |

| 40°→80° | 6.3 [4.5–8.1] | <0.001 | |

| LAεCD (%) | 0°→40° | 6.3 [4.2–8.4] | <0.001 |

| 0°→80° | 9.0 [6.6–11.5] | <0.001 | |

| 40°→80° | 2.8 [0.1–5.4] | 0.042 | |

| LAεCT (%) | 0°→40° | 3.0 [0.8–5.2] | 0.006 |

| 0°→80° | 6.4 [4.4–8.4] | <0.001 | |

| 40°→80° | 3.4 [1.4–5.5] | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: LAεR – left atrial reservoir strain, LA εCD – left atrial conduit strain - LA εCT – left atrial contractile strain.

Interestingly, percent changes in LA reservoir strain were approximately half the magnitude of those in the 2D LA maximum volumes measurements, and about a third smaller than the 3D LA maximum volumes measurements (Figure 3 and Table 3). Similar results were obtained for LA minimum volume. Of note, the percent changes in LA min volume were smaller than those in maximum volume, but this difference has not reached statistical significance in ¾ comparisons. Also, we found that the percent changes from 0 to 40 degrees were similar in 2D LA εR, εCT and εCD (21±11, 19±19 and 21±14, respectively), but the comparisons between 0 and 80 degrees revealed that εCT changed more than εCD (46±23 vs. 31±16, p<0.01).

Table 3.

Percent change from zero-degree tilt: Comparisons between LA reservoir strain and LA maximum and minimum volume measured from 2D and 3D images. P<0.05 was defined as significant.

| % Change | % Change | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From 0° to 40° tilt | 2D LA Reservoir Strain | 21±11 | 2D LA Max Volume | 43±14 | <0.001 |

| 3D LA Max Volume | 33±13 | 0.001 | |||

| 2D LA Min Volume | 30±22 | 0.110 | |||

| 3D LA Min Volume | 25±23 | 0.527 | |||

| From 0° to 80° tilt | 36±9 | 2D LA Max Volume | 62±13 | <0.001 | |

| 3D LA Max Volume | 50±10 | <0.001 | |||

| 2D LA Min Volume | 55±19 | <0.001 | |||

| 3D LA Min Volume | 48±15 | 0.003 |

Table 4 shows the results of the intra- and inter-observer variability analysis for LA strain measurements, reflecting high reproducibility for LA reservoir strain, slightly lower reproducibility for conduit strain followed by contractile strain.

Table 4.

Intra- and inter-observer variability is reported as an absolute difference between the corresponding pairs of repeated measurements as a percentage of their mean and by intraclass correlation coefficients.

| Intraobserver Variability | Interobserver Variability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variability % (SD) | ICC [CI 95%] | Variability %(SD) | ICC [CI 95%] | |

| LAεR (%) | 7±(4) | 0.97 [0.95–0.98] | 7±(6) | 0.91 [0.82–0.96] |

| LAεCD (%) | 12±(9) | 0.92 [0.87–0.95] | 9±(9) | 0.88 [0.71–0.94] |

| LAεCT (%) | 18±(15) | 0.93 [0.88–0.96] | 18±(17) | 0.89 [0.71–0.95] |

Abbreviations: LAεR – left atrial reservoir strain, LA εCD – left atrial conduit strain - LA εCT – left atrial contractile strain.

Discussion

LA strain is a relatively novel parameter used for the evaluation of LA function, which has been the subject of growing interest over recent years due to its incremental diagnostic and prognostic value in a number of common cardiac diseases. For example, in patients with acute coronary syndrome, it has been shown that LA reservoir strain can predict adverse LA remodeling (14). In patients with hypertension and diabetes, all LA strain components can identify LV diastolic dysfunction despite normal LA volumes (25). Moreover, LA reservoir strain has additional utility in distinguishing patients with heart failure with preserved EF from those with more benign forms of hypertensive heart disease (26). Furthermore, LA reservoir strain was able to discriminate between varying degrees of diastolic dysfunction (10). LA reservoir strain was able to predict the recurrence of atrial fibrillation after ablation therapy and was found to have an added value over CHA2DS2-VASc score in predicting thromboembolic risk (15, 27). In asymptomatic patients with severe primary mitral regurgitation, reduced LA reservoir strain carries worse prognosis in terms of morbidity and mortality and could serve as a marker for early surgical intervention(13).

Several recent studies have reported normal values of LA strain derived from relatively large populations (16–18, 28). However, the wide variability in values between and also within studies might hamper the translation of LA strain use into daily clinical practice. Different technical and physiological factors could account for the variability in the published normal values. Since aging has been shown to influence LA strain (29, 30), age-related normal values need to be further defined. Despite the recent inter-vendor initiative for the improvement of variability for myocardial strain software, the issue of inter-vendor differences is still of concern because of the remaining methodological differences in LA strain measurements (31). For example, different zero reference points have been described, with gating either using the P-wave or the R-wave. Moreover, different number of views have been used to obtain LA strain measurements, ranging from a single 4Ch view to the average of measurements from the three apical views (16). All of these factors likely contribute to the variability in LA strain values in normal individuals reported in the literature.

Our study examined the physiological manifestations of LA strain variability, namely the role of preload alterations. Indeed, although some evidence exists that LA strain may be preload dependent, particularly in pathological conditions (23, 24), the impact of an acute reduction in preload on LA strain in healthy individuals has never been systematically studied. Accordingly, in our study, acute modifications in preload were induced by a sudden postural change caused by a tilt from the baseline 0-degree position to 2 subsequent tilt levels of 40 and 80 degrees. This protocol allowed us to complete imaging for each level within only 2 minutes of establishing a new postural position. This maximized the effects of the normal compensatory baroreflex response, caused by a more pronounced, acute reduction in preload from baseline. The changes in vital parameters observed in our study during tilting were consistent with the described normal baroreceptor reflex that follows postural changes in healthy individuals and it is mainly the result of an increase in sympathetic activity, reflected by an increase in heart rate and arterial vasoconstriction in order to maintain constant blood pressure (32).

We found that acute reductions in preload were also associated with changes in a wide range of echocardiographic parameters. The changes in LA and LV volumes were in accordance with previous reports (19, 20). This included the most commonly used LA maximum volume and also LA minimum volume, which was recently found to have an additive and superior prognostic value (33, 34). Our findings confirmed the concept of the critical load dependence of LA and LV volumes and therefore the importance of interpreting these measurements in the context of the underlying hemodynamic conditions.

Mitral annular velocity and mitral inflow parameters also changed with preload alterations. Surprisingly, E/e’ ratio increased with decreasing preload, but similar findings have been previously reported by others (19). This finding emphasizes the limited ability of this particular parameter in isolation to estimate filling pressure with accuracy.

The novel finding of our study is the significant preload dependency of LA strain in healthy subjects. In fact, changes in LA reservoir strain induced by the tilt maneuver were larger than those reported in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis (23) or caused by general anesthesia and alterations in ventilator settings during cardiac surgery (24). This is likely due to the high compliance of the healthy left atrium in young individuals, compared to that of elderly patients exposed to a variety of pathological conditions, which may impair LA compliance. Another potential explanation could be that in our study, the changes in preload were acute without allowing a full compensatory response to take place.

Despite the fact that myocardial deformation had been thought to be load-independent, in contrast to ventricular volumes and ejection fraction, it has been recently demonstrated that varying loading conditions may critically influence LV strain (19–22). Our study showed that such dependence of strain measurements on loading conditions also exists for the left atrium. Understanding the response of LA strain to changes in preload may provide additional insights into normal LA function and potentially extend this knowledge to disease states to better characterize them. In this regard, our findings could form the premise for future studies of patients with LA abnormalities, for example secondary to mitral regurgitation, atrial fibrillation, or restrictive cardiomyopathy, to determine whether there is added value in understanding how LA function changes with preload in these disease state.

We found that changes in all LA strain components occurred in a stepwise fashion in response to the gradual decreases in preload. This finding underscores that LA strain should be evaluated in clinical practice in conjunction with the associated hemodynamic conditions, such as hypovolemia, or positional factors that may affect preload. This would include scenarios where imaging is performed with the patient in non-supine position, such as patients with acute cardiac dyspnea or in those undergoing echocardiographic bicycle stress testing.

Interestingly, we found that the percent change in LA reservoir strain (the most frequently described parameter in the LA strain literature) from baseline to the 80-degree position was considerably smaller, compared to the concomitant percent decrease in LA maximum volume (the most common parameter considered in LA assessment) and, a slightly smaller difference, in LA minimum volume. This is important because this finding provides evidence that LA strain is less load-dependent than LA volumes, supporting the argument that LA strain may be a superior approach to assessing LA function. At the present time, many echocardiographers seem to focus on measuring LA volume as a surrogate for LA function; accordingly, our study adds weight to the notion that measures of LA strain may have additional value.

Our findings could possibly also account for the results of recent publications which showed that LA reservoir strain is related to the degree of diastolic dysfunction (10) and may potentially be used as a single parameter to noninvasively estimate LV filling pressures (11, 12). Of note, it is difficult to estimate precisely the magnitude of the differences between LA strain and volume in this context, because of the differences between 2D and 3D volume measurements. These latter discrepancies may be due to the fact that 2D and 3D imaging were performed serially, during the physiological adaptation to the altered tilt position.

Furthermore, the changes in LA emptying fraction appeared to vary with preload when measured using 2DE, but not clearly so when using 3DE. It is likely that 3DE evaluation of LA volumes and emptying fractions is more accurate than the 2DE assessment, which is more affected by foreshortening during tilt maneuver. This is because the alterations in the relative position or angle of the heart to the intercostal space make it difficult to ensure optimal alignment of the imaging plane with LA anatomy. These findings underscore once again, albeit indirectly, the advantages of 3DE assessment of LA function.

Limitations

Although sample size was small, it was sufficient to detect changes in the parameters of interest with statistical significance and thus increasing the sample size would not have changed the results of the study. 2D LA strain measurement, like all 2D measurements, is limited by out-of-plane deformation and foreshortening. However, even when extreme attention was paid to acquire non-foreshortened images at all tilt phases, it is virtually impossible to prevent minimal differences in views. LA strain measurements were performed in the 4Ch view only, instead of averaging two or three views, therefore these findings cannot be extrapolated to LA strain measurements in the other views. However, no consensus has been reached regarding the best methodology for LA strain measurements, and averaging views has never been demonstrated as superior from the diagnostic or prognostic point of view. Of note, differences in views could potentially affect strain measurements, the significance of which would need to be evaluated by studying test-retest variability. Because our study did not include repeated acquisitions at different tilt angles because of time constraints, this issue should be addressed in future studies that do not involve preload manipulations.

Furthermore, despite the good image quality requirement for inclusion in the study, one might expect imaging at 40- and 80-degree tilt to be challenging. However, we did not note substantial reduction in image quality that would affect the accuracy of the measurements.

Finally, one could question whether our findings could be affected by the fixed sequence of tilt positions, since we arbitrarily performed a stepwise tilt from the baseline of 0 degrees to subsequent levels of 40 and 80 degrees. We strictly followed this acquisition sequence in all study subjects, in order to determine the differences between three preload states, assuming that our measurements were characteristic to each position, rather than significantly influenced by the transition from the previous state. This assumption may not be completely true, and in fact, we cannot rule out that a different order of tilt angles could possibly result in slightly different measurements. This is because imaging was performed within 2 minutes from reaching the target position, and it is possible that this period was not long enough for the subject to completely adapt to the new position. However, it is unlikely that a different acquisition sequence would have shown that LA strain is not load dependent. Moreover, the parameters of LA size and function that we compared (namely LA strain and LA volume) were derived from the same images, i.e. measured in the same state. It is less important whether this particular state was steady or to some degree transitional, as long as the measurements were made at the same time. Therefore, it is also unlikely that a different acquisition sequence would have resulted in a percent change in strain from state to state larger than that in volume. In other words, we believe that our main findings would remain the same in principle, irrespective of the sequence of tilt angles.

Conclusion

In summary, (i) LA strain is preload dependent in normal subjects, (ii) acute reductions in preload result in a stepwise decrease in LA reservoir, conduit and contractile strain; (iii) LA strain is less preload dependent than LA volumes. These findings suggest that LA strain may be advantageous to LA volume, but still should be interpreted while taking into account the hemodynamic conditions and positional factors which affect preload during imaging.

Acknowledgments

AS was supported by the NIH T32 Training Grant (#(5T32HL7381).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The remaining authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rossi A, Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Sandrini R, Golia G, Zardini P, et al. Determinants and prognostic value of left atrial volume in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(8):1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabharwal N, Cemin R, Rajan K, Hickman M, Lahiri A, Senior R. Usefulness of left atrial volume as a predictor of mortality in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(6):760–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA, Levy D. Left atrial size and the risk of stroke and death. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1995;92(4):835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(4):277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias A, Pizarro R, Oberti P, Falconi M, Lucas L, Sosa F, et al. Prognostic value of left atrial volume in asymptomatic organic mitral regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(7):699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barberato SH, Mantilla DE, Misocami MA, Goncalves SM, Bignelli AT, Riella MC, et al. Effect of preload reduction by hemodialysis on left atrial volume and echocardiographic Doppler parameters in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(9):1208–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mor-Avi V, Lang RM, Badano LP, Belohlavek M, Cardim NM, Derumeaux G, et al. Current and evolving echocardiographic techniques for the quantitative evaluation of cardiac mechanics: ASE/EAE consensus statement on methodology and indications endorsed by the Japanese Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(3):277–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirbu C, Herbots L, D’Hooge J, Claus P, Marciniak A, Langeland T, et al. Feasibility of strain and strain rate imaging for the assessment of regional left atrial deformation: a study in normal subjects. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DG, Lee KJ, Lee S, Jeong SY, Lee YS, Choi YJ, et al. Feasibility of two-dimensional global longitudinal strain and strain rate imaging for the assessment of left atrial function: a study in subjects with a low probability of cardiovascular disease and normal exercise capacity. Echocardiography. 2009;26(10):1179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A, Addetia K, Maffessanti F, Mor-Avi V, Lang RM. LA Strain for Categorization of LV Diastolic Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(7):735–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameli M, Sparla S, Losito M, Righini FM, Menci D, Lisi M, et al. Correlation of Left Atrial Strain and Doppler Measurements with Invasive Measurement of Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Pressure in Patients Stratified for Different Values of Ejection Fraction. Echocardiography. 2016;33(3):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameli M, Lisi M, Mondillo S, Padeletti M, Ballo P, Tsioulpas C, et al. Left atrial longitudinal strain by speckle tracking echocardiography correlates well with left ventricular filling pressures in patients with heart failure. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LT, Liu YW, Shih JY, Li YH, Tsai LM, Luo CY, et al. Predictive value of left atrial deformation on prognosis in severe primary mitral regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(11):1309–17.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoni ML, Ten Brinke EA, Marsan NA, Atary JZ, Holman ER, van der Wall EE, et al. Comprehensive assessment of changes in left atrial volumes and function after ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: role of two-dimensional speckle-tracking strain imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(10):1126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obokata M, Negishi K, Kurosawa K, Tateno R, Tange S, Arai M, et al. Left atrial strain provides incremental value for embolism risk stratification over CHA(2)DS(2)-VASc score and indicates prognostic impact in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(7):709–16 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathan F, D’Elia N, Nolan MT, Marwick TH, Negishi K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(1):59–70 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugimoto T, Robinet S, Dulgheru R, Bernard A, Ilardi F, Contu L, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left atrial function parameters: results from the EACVI NORRE study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miglioranza MH, Badano LP, Mihaila S, Peluso D, Cucchini U, Soriani N, et al. Physiologic Determinants of Left Atrial Longitudinal Strain: A Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking and Three-Dimensional Echocardiographic Study in Healthy Volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(11):1023–34.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negishi K, Borowski AG, Popovic ZB, Greenberg NL, Martin DS, Bungo MW, et al. Effect of Gravitational Gradients on Cardiac Filling and Performance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(12):1180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caiani EG, Weinert L, Takeuchi M, Veronesi F, Sugeng L, Corsi C, et al. Evaluation of alterations on mitral annulus velocities, strain, and strain rates due to abrupt changes in preload elicited by parabolic flight. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103(1):80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns AT, La Gerche A, D’Hooge J, MacIsaac AI, Prior DL. Left ventricular strain and strain rate: characterization of the effect of load in human subjects. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11(3):283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nafati C, Gardette M, Leone M, Reydellet L, Blasco V, Lannelongue A, et al. Use of speckle-tracking strain in preload-dependent patients, need for cautious interpretation! Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park CS, Kim YK, Song HC, Choi EJ, Ihm SH, Kim HY, et al. Effect of preload on left atrial function: evaluated by tissue Doppler and strain imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13(11):938–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard-Quijano K, Anderson-Dam J, McCabe M, Hall M, Mazor E, Mahajan A. Speckle-Tracking Strain Imaging Identifies Alterations in Left Atrial Mechanics With General Anesthesia and Positive-Pressure Ventilation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29(4):845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mondillo S, Cameli M, Caputo ML, Lisi M, Palmerini E, Padeletti M, et al. Early detection of left atrial strain abnormalities by speckle-tracking in hypertensive and diabetic patients with normal left atrial size. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(8):898–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obokata M, Negishi K, Kurosawa K, Arima H, Tateno R, Ui G, et al. Incremental diagnostic value of la strain with leg lifts in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(7):749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motoki H, Negishi K, Kusunose K, Popovic ZB, Bhargava M, Wazni OM, et al. Global left atrial strain in the prediction of sinus rhythm maintenance after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(11):1184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris DA, Takeuchi M, Krisper M, Kohncke C, Bekfani T, Carstensen T, et al. Normal values and clinical relevance of left atrial myocardial function analysed by speckle-tracking echocardiography: multicentre study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(4):364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun JP, Yang Y, Guo R, Wang D, Lee AP, Wang XY, et al. Left atrial regional phasic strain, strain rate and velocity by speckle-tracking echocardiography: normal values and effects of aging in a large group of normal subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(4):3473–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd AC, Richards DA, Marwick T, Thomas L. Atrial strain rate is a sensitive measure of alterations in atrial phasic function in healthy ageing. Heart. 2011;97(18):1513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badano LP, Kolias TJ, Muraru D, Abraham TP, Aurigemma G, Edvardsen T, et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: a consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens PM. Cardiovascular dynamics during orthostasis and the influence of intravascular instrumentation. Am J Cardiol. 1966;17(2):211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fatema K, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, Cha S, Seward JB, et al. Minimum vs. maximum left atrial volume for prediction of first atrial fibrillation or flutter in an elderly cohort: a prospective study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(2):282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu VC, Takeuchi M, Kuwaki H, Iwataki M, Nagata Y, Otani K, et al. Prognostic value of LA volumes assessed by transthoracic 3D echocardiography: comparison with 2D echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(10):1025–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]