Abstract

Background

Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (sPAH) results in a dilated and dysfunctional right ventricle (RV) together with a small left ventricle (LV) with preserved systolic function. RV size and function parameters have an established association with poor prognosis in sPAH. We sought to determine the impact of RV geometry and function on LV mechanics and its relationship with mortality.

Methods

We studied 114 patients (54 ± 13 years) with sPAH, normal LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and complete two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) and compared them with 70 normal controls of similar age and gender distribution. TTE measurements of atrial sizes, ventricular volumes and function, tricuspid and mitral regurgitation (TR, MR), and LV diastolic function were performed. Speckle-tracking strain was measured in all four chambers, including LV global longitudinal strain (GLS). Cox proportional hazards regression with forward selection was performed to determine the associations between measured indices and mortality over a 20-month follow-up period. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated for variables most associated with death.

Results

Compared with controls, sPAH patients had greater TR severity and right-chamber size with worse function. Of note, LVEF was normal in both groups. Left atrial peak strain and LV GLS were reduced in sPAH, with greater reductions in nonsurvivors. In multivariate analysis, right atrial volume index (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.02 [CI, 1.01–1.04], P < .01), RV free-wall strain (HR = 1.08; CI [1.01–1.15]; P = .03), and LV GLS (HR = 1.11 [CI, 1.01–1.22]; P = .04) were independently associated with mortality.

Conclusions

Although PAH is predominantly a right heart disease, in our cohort of sPAH with normal LVEF, LV GLS was independently associated with death in addition to RV and right atrial abnormalities. These findings indicate that the role of left heart dysfunction in sPAH may be underappreciated in clinical practice.

Keywords: Left ventricle, Longitudinal strain, Pulmonary arterial hypertension

In severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (sPAH), characteristic changes of the right ventricle (RV) are seen with echocardiography, including RV dilatation, impaired contractility, and paradoxical motion of the interventricular septum with associated right heart failure.1 However, there are limited data on the impact of RV failure on the left heart chambers, especially when considering that geometric changes occurring in the RV could exert a deleterious effect on the left ventricle (LV).2 While traditional two-dimensional (2D) echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular (LV) size and function is frequently normal in these patients, recent data have suggested that LV dysfunction might be present in patients with PAH3 Although the mechanism of this LV dysfunction is not completely understood, contributing factors are thought to include impaired LV filling due to abnormal interventricular septal motion, as well as intrinsic diastolic abnormalities of the LV myocardium.3 Small studies in patients with PAH using speckle-tracking techniques have supported the presence of LV dysfunction reflected by impaired LV longitudinal and circumferential strain in these patients.4–6

Given that RV size and function have been shown to be prognostic in patients with pulmonary hypertension,7 we studied patients with sPAH and apparently normal LV systolic function, in whom RV function had already deteriorated to a degree that it portends poor prognosis and in whom additional markers may be useful to better strategize treatment. We hypothesized that RV mechanical and loading changes in sPAH may have deleterious effects on LV function, and aimed to determine whether, despite the normal LV dimensions and function on 2D echocardiography, interventricular interaction impacts left heart function to a degree that subclinical changes in LV diastolic function and peak systolic strain would become apparent and would be associated with poor outcomes.

METHODS

Patient Population

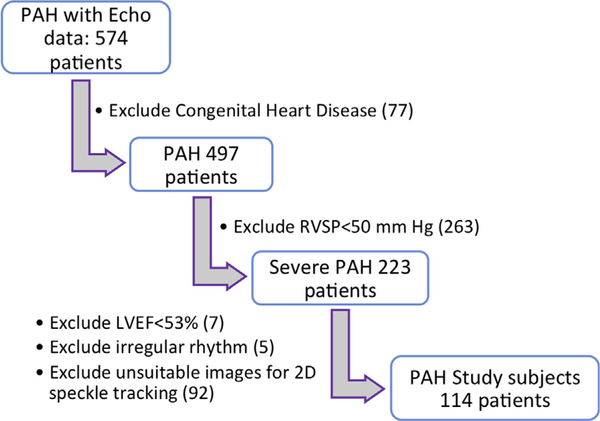

We retrospectively screened adult subjects (age > 18 years) with severe group I PAH8 and normal LV ejection fraction (LVEF), who were followed in a tertiary-care pulmonary hypertension clinic (n = 574, from April 2007 to October 2015). To be included in the study (Figure 1), patients with a complete 2D transthoracic echocardiography (2D TTE) had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) documented severe pulmonary hypertension on TTE (estimated pulmonary arterial [PA] systolic pressure ≥50 mm Hg, and D-shaped interventricular septum during systole and diastole on parasternal short-axis views)9; (2) absence of congenital heart disease or intracardiac shunt physiology; (3) preserved LVEF (≥53%)10; (4) normal sinus rhythm; (5) image quality adequate for LV and RV strain analysis by 2D-speckle tracking. A total of 114 patients were included in the final analysis. To compare left heart parameters in sPAH patients to those found in healthy subjects, we enrolled a group of 70 healthy controls with similar age and gender distribution who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) no previous history of cardiovascular disease and (2) normal baseline TTE (normal RV and LV function, no evidence for valvular regurgitation, and estimated PA systolic pressure <25 mm Hg). In all study subjects, heart rate, noninvasive blood pressure (BP), and body mass index were obtained at the time of the echocardiogram. All sPAH patients underwent right heart catheterization as part of their clinical care.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart demonstrating patient inclusion criteria. RVSP, Right ventricular systolic pressure.

Demographic information and clinical data (including PAH etiology and mortality outcomes) were obtained from chart review. The primary end-point was all-cause mortality. Confirmation of mortality was obtained using the Social Security Death Index and/or availability of death certificate in the medical record. An Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All subjects signed consent to be enrolled in the Pulmonary Hypertension Connection database.11

2D Echocardiography

Comprehensive 2D, Doppler, and color Doppler echocardiography were performed by an experienced sonographer using the iE33 imaging system (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA). Linear dimensions of LV were measured in the parasternal long-axis view. LV volumes and LVEF were measured from the apical two- and four-chamber views using the biplane method of disks (MOD). Left atrial (LA) volumes were measured from LA focused apical two- and four-chamber views using biplane MOD and indexed to body surface area (LA volume index [LAVi]).10 LV mass was determined using the Devereux formula,2,10 and LV eccentricity index (EI) was measured in systole as previously described.9 RV basal and midventricular diameters, RV fractional area change and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), PA systolic pressure, and inferior vena cava collapsibility were assessed per recommended guidelines.10 Right atrial (RA) volume was determined using the single-plane MOD technique from an apical four-chamber view and indexed to body surface area (RA volume index [RAVi]). Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) severity was assessed by vena contracta (VC) width, measured in the RV inflow view and apical four-chamber view and then averaged, with grading as follows: mild if VC < 0.3 cm; moderate if VC ≥ 0.3 but <0.7 cm; severe if VC ≥ 0.7 cm. Similarly, mitral regurgitation (MR) was quantified by VC, from the parasternal long-axis view. Pulsed-wave and tissue Doppler imaging were used to measure mitral inflow E and A velocities, E/A ratio, and mitral inflow E-wave deceleration time as well as lateral and medial e′ velocities.

2D Speckle-Tracking Analysis

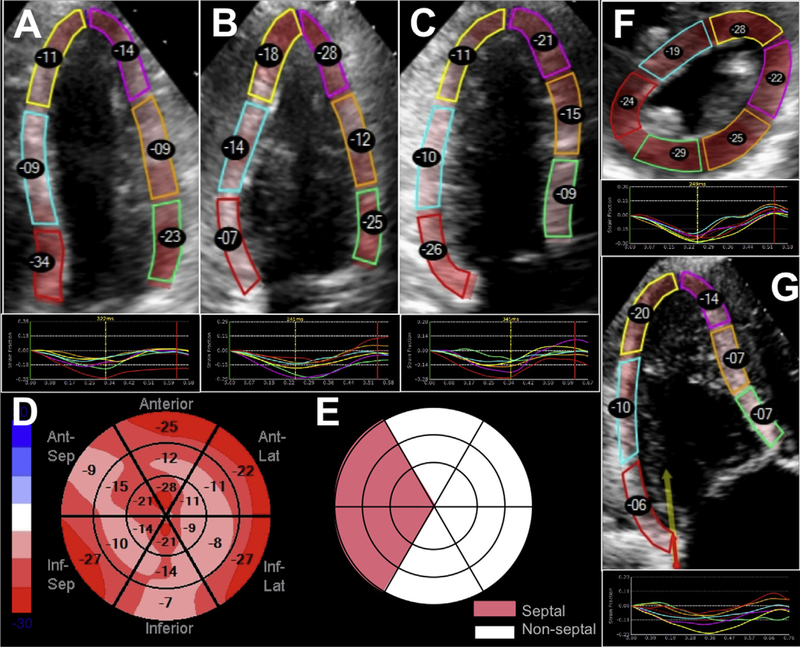

Two-dimensional speckle-tracking was performed (EchoInsight, Epsilon Imaging, Ann Arbor, MI) to obtain global longitudinal strain (GLS) for the LV, including, separately, longitudinal strain (LS) of the septal and nonseptal LV walls, and the RV, including total and free-wall, strain. LV endocardial border was traced in the apical four-, three-, and two-chamber views to determine LV GLS. LV circumferential and radial strains were measured by tracing the endocardium in the parasternal short-axis view at the papillary muscle level. LS of the RV free-wall and total (free-wall and septal) RV strain were measured from the RV-focused view (Figure 2). Both RA and LA LS were measured from an apical four-chamber view, with the interatrial septum included in both chambers. Volume curves obtained by the speckle-tracking software were used to calculate LA reservoir, conduit, and booster functions as previously described.12,13

Figure 2.

Measurement of GLS for the LV using the apical four-, apical two-, and apical three-chamber views (A-C). A bull’s-eye depicting the segments of the LV used to determine GLS is shown in panel D. Division of the LV segments into septal and nonseptal regions is illustrated in panel E. The measurement of circumferential and radial strain using the LV mid short-axis view is shown in panel F. The right ventricular-focused view is used to obtain right ventricular free-wall (three free-wall segments) and total (all six segments) strain from the apical four-chamber view (G).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD or medians (interquartile ranges). Categorical variables were expressed in absolute numbers and percentages. Independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests (Wilcoxon rank sum test) were used for comparisons between groups (sPAH vs controls and sPAH nonsurvivors vs survivors). The χ2-test of ratios was used to compare categorical variables. Continuous variables were checked for normality using Shapiro-Wilk’s test, and then they were checked for correlations using Spearman’s correlations. Continuous variables with significant correlations >0.70 or <−0.70 were considered to have collinearity. Clinical relevance determined which variables were to be included in the Cox proportional hazards regression models. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine associations of relevant variables and all-cause mortality. Significant associations from the univariate analysis then were analyzed with a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model with forward selection depending upon likelihood ratio statistics. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CIs were calculated per unit of each independent continuous variable. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using tertiles of the significant association variables from the Cox proportional hazards regression and compared with the use of a log rank test. The last date of follow-up was January 2016. Statistical analysis was performed using the software package IBM SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

To assess interobserver variability in LV GLS, 15 sPAH patients were remeasured by an independent observer who was blinded to the initial observer’s results. This investigator also independently selected the best cardiac cycle for analysis. Interobserver variability was expressed in terms of intraclass correlation and percent variability, defined as the absolute differences between pairs of repeated measurements divided by their mean.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of sPAH and control groups are presented in Table 1. PAH subjects were predominantly female, with the most common etiologies of sPAH being connective tissue disease (n = 51, 44%) and idiopathic (n = 43, 37%). When compared with control subjects, patients with sPAH demonstrated significant RA and RV dilatation, in addition to other parameters indicative of RV dysfunction. In addition, sPAH patients demonstrated a slightly higher LVEF when compared with controls (65% ± 6% vs 63% ± 4%; P = .008). LV diastolic dysfunction was present in patients with sPAH, as evidenced by low E/A ratios, reduced mitral annular tissue Doppler e′ velocities, and higher E/e′ values compared with controls. These diastolic abnormalities occurred in the absence of LA enlargement. Impaired LA phasic function was concomitantly present with smaller LA dimensions in sPAH patients, exhibiting significantly diminished reservoir (48% ± 11%) and booster function (24% ± 13%), when compared with controls (114% ± 48% and 35% ± 11%; P <.001 for both).

Table 1.

Baseline and echocardiographic characteristics of PAH and control subjects

| Parameter | PAH (n = 114) | Controls (n = 70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 93 (82) | 59 (83) | .64 |

| Age, years | 54 ± 13 | 53 ± 11 | .49 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | .57 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 80 ± 14 | 69 ± 11 | <.001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 119 ± 20 | 127 ± 16 | <.01 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 70 ± 11 | 71 ± 11 | .56 |

| PAH etiology | |||

| Idiopathic PAH | 43 (37) | NA | |

| Connective tissue disease | 51 (44) | NA | |

| Portopulmonary hypertension | 11 (10) | NA | |

| Anorexigen use | 3 (3) | NA | |

| HIV | 3 (3) | NA | |

| Other | 3 (3) | NA | |

| Echocardiography | |||

| Right heart | |||

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg | 85 ± 18 | 18 ± 7 | <.01 |

| RV FAC, % | 32 ± 10 | 51 ± 4 | <.01 |

| RV basal dimension, cm | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | <.01 |

| RV mid dimension, cm | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | <.01 |

| TAPSE, cm | 1.7 ± 0.5 (n = 81) | 2.3 ± 0.5 (n = 6 8) | <.01 |

| Lateral S′, cm/sec | 10 ± 2 (n = 79) | 13 ± 2 (n = 68) | <.01 |

| TR VC width, mm | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | <.01 |

| Left heart | |||

| LVEF, % | 65 ± 6 | 63 ± 4 | <.01 |

| LVEDD, cm | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | <.01 |

| LVESD, cm | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | <.01 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 65 ± 21 | 65 ± 11 | .330 |

| MR VC width, mm | 0.4 ± 1 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | <.01 |

| EI | 1.9 ± 0.5 | NA | <.01 |

| LV diastolic function | |||

| E velocity, cm/sec | 72 ± 23 | 78 ± 15 | <.01 |

| A velocity, cm/sec | 77 ± 20 | 71 ± 20 | .04 |

| E/A ratio | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | <.01 |

| Deceleration time, sec | 0.22 ± 0.1 | 0.22 ± 0.1 | .73 |

| Medial e′ velocity, cm/sec | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 2.1 | <.01 |

| Lateral e′ velocity, cm/sec | 8.7 ± 3.2 | 11 ± 3.2 | <.01 |

| Lateral E/e′ | 9.7 ± 5.8 | 7.6 ± 3.0 | .02 |

| Atrium | |||

| RA volume index, mL/m2 | 43 ± 22 | 15 ± 5 | <.01 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 20 ± 10 | 22 ± 6 | <.01 |

| Atrial phasic data | |||

| LA reservoir fraction, % | 48 ± 11 | 114 ± 48 | <.01 |

| LA conduit fraction, % | 33 ± 17 | 31 ± 12 | .50 |

| LA booster fraction, % | 24 ± 13 | 35 ± 11 | <.01 |

| Pericardial effusion (%) | |||

| No effusion | 65 (57) | ||

| Effusion <1 cm | 36 (32) | ||

| Effusion ≥ 1 cm | 13(11) | ||

LVEDD, LV end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; RA, right atrium; RV FAC, right ventricular fractional area change.

Data in parentheses are percentages.

Within the sPAH cohort, 48 (42%) subjects died during a mean follow-up period of 20 ± 20 months. Cause of death was clearly cardiovascular in 42%, unlikely cardiovascular in 15%, and probably cardiovascular in the remainder. There were no differences in age, gender, or PAH etiology among the patients who died versus those who survived (Table 2). Nonsurvivors had significantly higher estimated PA systolic pressure and greater TR VC, as well as larger right heart dimensions and worse measures of RV function. There were no significant differences in LV systolic or diastolic parameters between patients with PAH who survived and those who died. Assessment of LA phasic function revealed markedly impaired booster function (20% ± 15% in nonsurvivors vs 26% ± 12% in survivors; P = .024), despite no significant difference in LA size.

Table 2.

Characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors with severe PAH

| Parameter | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 66 (58) | 48 (42) | |

| Gender (% female) | 54 (82) | 39 (82) | .94 |

| Age, years | 55 ± 12 | 53 ± 14 | .37 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | .34 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 78 ± 14 | 83 ± 15 | .07 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 122 ± 20 | 114 ± 18 | .03 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 70 ± 11 | 69 ± 12 | .60 |

| PAH etiology (%) | |||

| Idiopathic PAH | 29 (44) | 14 (29) | .28 |

| PAH with connective tissue disease | 25 (38) | 26 (54) | .03 |

| PAH with liver disease | 6 (9) | 5 (11) | .83 |

| Anorexigen use | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | .76 |

| HIV | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | .14 |

| Others | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | .40 |

| Right heart catheterization data* | |||

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg | 81 ± 18 | 86 ± 18 | .20 |

| Mean PAP, mm Hg | 49 ± 11 | 53 ± 13 | .07 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mm Hg | 10 ± 4 | 11 ± 5 | .11 |

| Cardiac output | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | .33 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| Right heart | |||

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg | 79 ± 15 | 92 ± 20 | <.01 |

| RV FAC, % | 34 ± 10 | 28 ± 9 | <.01 |

| RV basal dimension, cm | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | <.01 |

| RV mid dimension, cm | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | <.01 |

| TAPSE, cm | 1.7 ± 0.4 (n = 52) | 1.5 ± 0.5 (n = 29) | .04 |

| Lateral S′, cm/sec | 10.7 ± 1.7 (n = 50) | 9.8 ± 1.9 (n = 29) | .03 |

| TR VC width, mm | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | <.01 |

| Left heart | |||

| LVEF, % | 65 ± 5 | 65 ± 6 | .83 |

| LVEDD, cm | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | .02 |

| LVESD, cm | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | .07 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 65 ± 20 | 64 ± 22 | .51 |

| EI | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | <.01 |

| Diastolic function | |||

| E velocity, cm/sec | 73 ± 20 | 71 ± 26 | .28 |

| A velocity, cm/sec | 80 ± 21 | 74 ± 17 | .16 |

| E/A ratio | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | .86 |

| Deceleration time, msec | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | .11 |

| Medial e′ velocity, cm/sec | 5.0 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 1.8 | .48 |

| Lateral e′ velocity, cm/sec | 8.9 ± 2.9 | 8.4 ± 3.6 | .47 |

| Lateral E/e′ | 9 ± 4 | 11 ± 7 | .77 |

| Atrium | |||

| RA volume index, mL/m2 | 36 ± 15 | 54 ± 25 | <.01 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 21 ± 9 | 19 ± 11 | .10 |

| Atrial phasic data, % | |||

| LA reservoir fraction | 49 ± 11 | 48 ± 11 | .58 |

| LA conduit fraction | 32 ± 18 | 34 ± 14 | .63 |

| LA booster fraction | 26 ± 12 | 20 ± 15 | .03 |

| Pericardial effusion (%) | |||

| No effusion | 40 (61) | 25 (52) | .63 |

| Effusion < 1 cm | 18 (27) | 18 (38) | .41 |

| Effusion ≥ 1 cm | 8(12) | 5(10) | .08 |

LVEDD, LV end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; RA, right atrium; RV FAC, right ventricular fractional area change.

*Earliest available.

Compared with controls, patients with sPAH exhibited abnormal peak strain in all of the four cardiac chambers (Table 3). Despite demonstrably higher LVEF, patients with PAH had significantly reduced global longitudinal, circumferential, and radial strain when compared with controls. Within the sPAH cohort, peak RV free-wall strain was lower in nonsurvivors (Table 4). LV GLS and radial strain were also significantly lower in nonsurvivors, with both the septal and nonseptal LV regions demonstrating greater impairment in nonsurvivors. Peak LA strain was also abnormal, with lower values in nonsurvivors, but peak RA strain was not significantly different.

Table 3.

Speckle-tracking results of severe PAH and controls

| (%) | PAH (n = 114) | Controls (n = 70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV strain | |||

| Global longitudinal | −17 ± 3 | −21 ± 2 | <.01 |

| Septal longitudinal | −15 ± 4 | −20 ± 3 | <.01 |

| Nonseptal longitudinal | –18 6 3 | −21 ± 3 | <.01 |

| Circumferential | −27 ± 7 | −31 ± 4 | <.01 |

| Radial | 21 ± 10 | 34 ± 12 | <.01 |

| RV strain | |||

| RV free-wall longitudinal | −16 ± 6 | −27 ± 4 | <.01 |

| RV total wall longitudinal | −13 ± 5 | −22 ± 3 | <.01 |

| Atrial strain | |||

| LA peak | 20 ± 8 | 34 ± 9 | <.01 |

| RA peak | 24 ± 11 | 46 ± 17 | <.01 |

Table 4.

Speckle-tracking results of survivors and nonsurvivors with severe PAH

| (%) | Survivors (n = 66) | Non-survivors (n = 48) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV strain | |||

| Global longitudinal | −18 ± 3 | −16 ± 4 | <.01 |

| Septal longitudinal | −16 ± 3 | −13 ± 5 | <.01 |

| Nonseptal longitudinal | −19 ± 3 | −17 ± 4 | .02 |

| Circumferential | −28 ± 6 | −26 ± 8 | .08 |

| Radial | 22 ± 10 | 18 ± 9 | .02 |

| RV strain | |||

| RV free-wall longitudinal | −18 ± 5 | −14 ± 6 | <.01 |

| RV total wall longitudinal | −15 ± 4 | −11 ± 5 | <.01 |

| Atrial strain | |||

| LA peak | 23 ± 8 | 15 ± 8 | .01 |

| RA peak | 26 ± 12 | 21 ± 11 | .24 |

Parameters Associated with Mortality

On univariate analysis, multiple right heart parameters were found to be significantly associated with mortality including systolic pulmonary artery pressure, RAVi, peak RA strain, RV fractional area change, and RV free-wall LS (Table 5). Interestingly, none of the diastolic parameters were significant on univariate analysis. Of the left heart parameters, EI, peak LA strain, and LV GLS (including separately septal and nonseptal LS) were the only significant parameters. In addition to echocardiographic parameters, heart rate and systolic BP were also significantly associated with mortality on univariate analysis. When testing for associations between parameters, significant Spearman rank correlations < −0.70 and > 0.70 were observed between RV dimensions (basal and midchamber), between RV free-wall LS, RV total wall LS, and RV fractional area change, and between LV GLS, LV septal LS, and LV non-septal LS. Thus, when selecting parameters for multivariate analysis, we opted to choose only one of the highly correlated parameters. Ultimately, we included those variables that were easiest to measure and that were most likely to be measured clinically. The following parameters were therefore chosen as inputs for a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model with forward selection based on likelihood ratio statistics: LV GLS, RV free-wall LS, both atrial strains, RAVi, EI, TR VC, estimated systolic PA pressure, and RV basal dimension. The model resulted in three significant variables of interest: RAVi (HR = 1.02; Cl, 1.01–1.04; P < .01); LV GLS (HR = 1.11; Cl, 1.01–1.22; P = .04), and RV free-wall LS (HR = 1.08; Cl, 1.01–1.15; P = .03; Table 6), which showed the strongest independent associations with mortality. Of note, neither heart rate nor systolic BP were independently associated with mortality. Furthermore, when septal and, separately, nonseptal LS were entered into the regression model, septal LS was not independently associated with mortality, while the nonseptal LS reached a P value of .05.

Table 5.

Results of univariate analysis for mortality

| Parameter | Univariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI |

||||

| P | HR | Lower | Upper | |

| Age | .84 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 |

| Body surface area | .61 | 1.37 | 0.41 | 4.58 |

| Systolic BP | .02 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| Heart rate | <.01 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 |

| PAH etiology | .20 | 1.68 | 0.75 | 1.06 |

| Right heart | ||||

| Systolic PAP, mm Hg | <.04 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| RV FAC, % | <.01 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.97 |

| RV mid length, cm | <.01 | 1.57 | 1.19 | 2.08 |

| RV basal length, cm | <.01 | 1.92 | 1.37 | 2.70 |

| RV length, cm | .03 | 1.43 | 1.04 | 1.97 |

| TR VC width, mm | <.01 | 1.29 | 1.14 | 1.45 |

| Left heart | ||||

| LVEF, % | .47 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 |

| LVEDD, cm | .05 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.99 |

| LVESD, cm | .05 | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.99 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | .50 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| EI | <.01 | 2.47 | 1.43 | 4.29 |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| E velocity, cm/sec | .50 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| A velocity, cm/sec | .27 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| E/A ratio | .63 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 2.33 |

| Deceleration time, msec | .17 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 3.50 |

| Medial e′ velocity, cm/sec | .31 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 1.10 |

| Lateral e′ velocity, cm/sec | .21 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.04 |

| Lateral E/e′ | .09 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.10 |

| Atrium | ||||

| RA volume index, mL/m2 | <.01 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.05 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | .47 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 |

| LV strain, % | ||||

| Global longitudinal | <.01 | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.31 |

| Septal longitudinal | <.01 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.27 |

| Nonseptal longitudinal | <.01 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.29 |

| Circumferential | .06 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.10 |

| Radial | .14 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 |

| RV strain, % | ||||

| RV free-wall longitudinal | <.01 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.22 |

| RV total wall longitudinal | <.01 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.23 |

| Atrial strain, % | ||||

| LA peak | <.01 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| RA peak | <.01 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 |

| Pericardial effusion | .21 | 1.31 | 0.86 | 2.01 |

LVEDD, LV end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; RA, right atrium; RV FAC, right ventricular fractional area change.

HRs and 95% CIs are reported per unit of each independent continuous variable, shown next to each variable.

Table 6.

Results of the multivariate Cox regression model with forward selection

| Parameter | Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI |

||||

| P | HR | Lower | Upper | |

| Atrium: RAVi, mL/m2 | .00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| LV strain: global longitudinal, % | .04 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.22 |

| RV strain: RV free-wall longitudinal, % | .03 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 |

HRs and 95% CIs are reported per unit of each independent continuous variable, shown next to each variable.

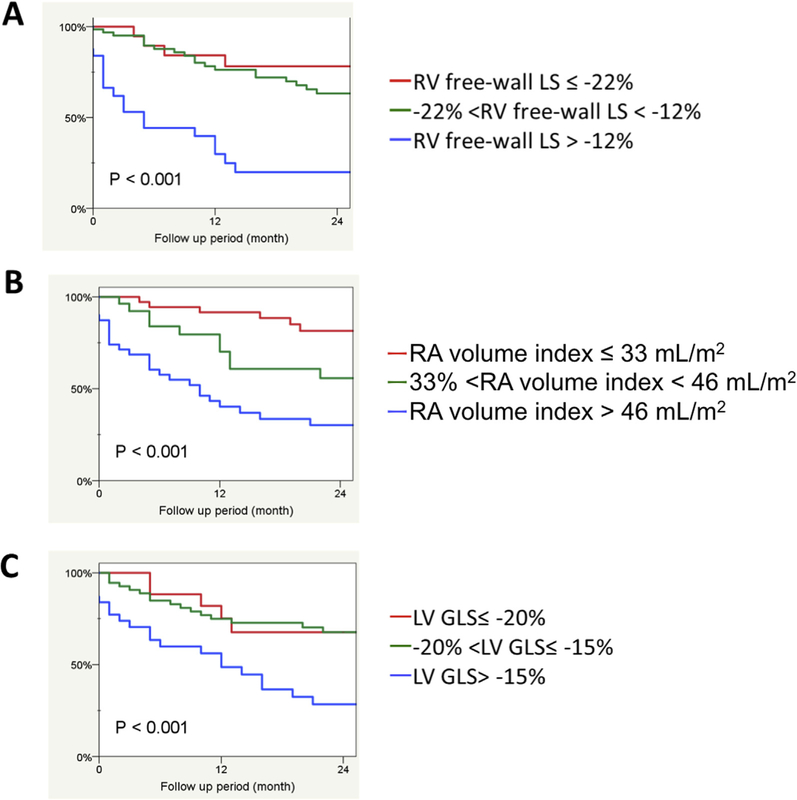

When sPAH patients were stratified into tertiles by RV free-wall strain, (≤−22%, −12 to −22%, and >−12%), a RV free-wall strain value of ≥−12% (i.e., lowest strain magnitude tertile) was strongly associated with mortality (Figure 3A, P < .001). Indexed RA volume tertiles were defined as ≤33 mL/m2, >33 to <46, and >46 mL/m2. Each stratification impacted prognosis, with RAVi > 46 mL/m2 showing a significant association with mortality (Figure 3B, P < .001). LV GLS tertiles were defined as ≤−20%, −15 to −20%, and >−15%. Kaplan-Meier analysis using LV GLS demonstrated that a value of >−15% was strongly associated with mortality (Figure 3C, P <.001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by tertiles of (A) right ventricular free-wall LS (RV free-wall LS; %), (B) indexed RA volume (mL/m2), and (C) LV GLS (%).

Interobserver Variability

Interobserver variability for LV GLS was good, as reflected by percent variability of 10% and intraclass correlation of 0.81. As expected, intraobserver variability was better with an intraclass correlation of 0.94 and percent variability of 6%.

DISCUSSION

Severe PAH is a disease characterized by significant right heart RV and RA dilatation as well as a poorly contractile RV, both of which are known to be associated with worse outcomes and mortality. Indeed, our results show these two factors are strongly associated with mortality. However, our results also demonstrate that patients with sPAH exhibit LV mechanical dysfunction, despite relatively normal LV dimensions and ejection fraction. LV GLS, like RV free-wall LS and RAVi, was independently associated with reduced survival in this population. This underscores the importance of impaired LV mechanics in patients with sPAH and RV failure, a finding that cannot be measured using traditional 2D LV size and function parameters, suggesting that in these patients, measures of LV mechanics should be included in the echocardiographic evaluation, particularly when the RV is dysfunctional.

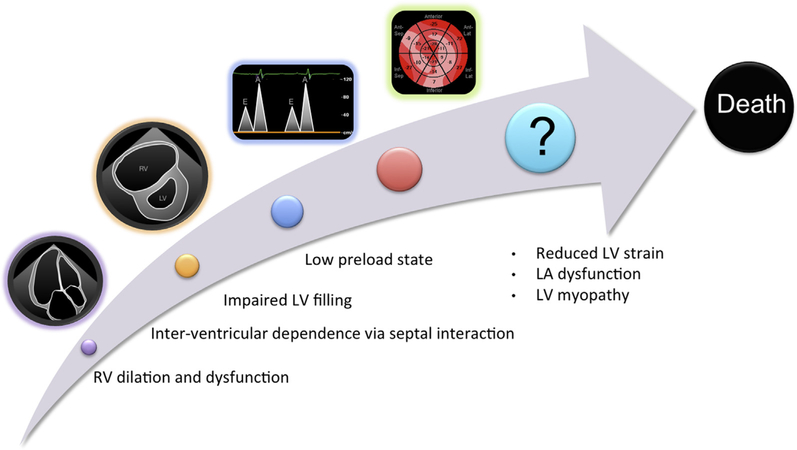

The maladaptive remodeling of the right heart in PAH has been well described, beginning with RV hypertrophy in response to increased pulmonary vascular pressures, followed by chamber dilation and impaired contractile function. As right-sided filling pressures rise and cardiac output deteriorates, a concomitant RV pressure and volume overload state develops, thereby shifting the interventricular septum leftward, leading to paradoxical septal motion. This septal shift negatively impacts the LV by impairing filling, effectively creating a physiologic low-preload state (Figure 4).5

Figure 4.

Proposed progression of left heart dysfunction in PAH. See text for details. RV, Right ventricular.

Our results support the current thinking that impaired LV function in sPAH is mediated by interventricular dependence and subsequent reduction of LV filling. First, sPAH patients exhibit diastolic dysfunction, as supported by findings of mitral E-A reversal, reduced mitral annular tissue Doppler velocities, and higher lateral E/e′ values when compared with normal subjects. The presence of LA dysfunction demonstrated in this study further supports the diastolic abnormalities associated with PAH. However, the LA enlargement known to be associated with diastolic dysfunction is absent. Additionally, there is a pattern of impaired LA reservoir function together with a deterioration of LA booster function in sPAH, when compared wih normal subjects, probably because of the decrease in preload. In nonsurvivors with sPAH, we observed progressive worsening of LA booster function compared with survivors, despite similar indexed volumes. From a physiologic standpoint, the hemodynamic consequences resulting from the loss of this critical atrial function lead to a low-preload state (Figure 4).

The LV strain abnormalities noted in this study contribute to the notion that while LV dysfunction is present in sPAH, it is predominantly subclinical as the LVEF is preserved. In the sPAH cohort, both longitudinal and radial LV strain components were significantly abnormal, despite a mean LVEF, which was higher than that in controls. Previous studies have suggested that LV strain abnormalities are limited to the septum, with preserved lateral wall strain, underscoring the importance of interventricular dependence in the resultant impaired LV performance associated with PAH.9 We were able to further investigate the impact of PAH on LV function, by analyzing regional LV GLS, in patients with severe PAH only. We found that strain for both the septal and nonseptal LV segments was reduced in sPAH when compared with controls and furthermore that both strain components were more severely reduced in nonsurvivors when compared with survivors. Of note, in our sPAH cohort, separate multivariate analyses that included septal and nonseptal LS instead of GLS allowed us to rule out that these findings were not of purely septal origin. Importantly, the mechanism of nonseptal LV involvement remains unclear. One small study used histopathologic correlates obtained with LV endomyocardial biopsy to demonstrate the presence of myocyte atrophy and dysfunction in PAH patients, but the concept of intrinsic myocyte dysfunction remains theoretical at this time.14

It is possible that progressive RV (and RA) enlargement and failure compromise the loading conditions of the left heart (LV and LA) by diminishing available preload because both ventricles and atria coexist within the confines of the pericardial sac. RV enlargement and failure therefore in turn contribute to impaired LV function and account for reduced LS. This mode of reasoning also explains why LV mechanical abnormalities become most pronounced in later stages of the disease when RV dysfunction is more severe. It is in this clinical context that echocardiographic assessment of LV strain may be most helpful; while RV dilation and dysfunction are marked, and the LV appears normal or hyperdynamic, it is LV GLS that demonstrates insidious dysfunction, portending a poorer prognosis. This is further supported by the finding in our study that sPAH patients were more tachycardiac than controls, suggesting that patients compensate for the low-preload state of the LV by increasing stroke volume. When nonsurvivors were compared with survivors, heart rate was no longer different between groups but BP was significantly lower in nonsurvivors, suggesting that perhaps LV dysfunction has reached a point at which the patient’s cardiac output could no longer be supported. Reduced cardiac output could result in reduced coronary flow, which could be an additional cause of the subclinical LV dysfunction found in this study.

In summary, improvements in current algorithms for risk stratification in sPAH are critically needed. The mortality associated with this disease is high, as evidenced by the death of 42% of our cohort during an average follow-up period of <2 years. The association between right heart abnormalities and worse outcomes is well established and evident in our cohort, where RV free-wall LS and RAVi were among the variables most strongly associated with mortality.7,15–17 Our results further demonstrate that left heart function in sPAH is also abnormal despite normal LVEF, with concomitant diastolic abnormalities and LA dysfunction present, which likely contribute to an overall low-preload state. The attendant LV systolic dysfunction, manifest as reduced GLS, involves the entire LV, not just the interventricular septum, and is also strongly associated with mortality (Figure 4).

Limitations

While our study included a large group of sPAH patients, important limitations to consider include that the vast majority of patients had group 1 PAH, so that findings in this study cannot be extrapolated to other etiologies of pulmonary hypertension with significant RV dysfunction. In addition, our study was retrospective. Also, one might suggest that the role of LV GLS in the prognosis and detection of subclinical worsening of disease over time in PAH should be studied in a larger number of patients representing a spectrum of pulmonary hypertension, to determine whether the prognostic importance of LV strain holds as a biomarker. However, in patients with less than severe PAH, RV function by itself provides important prognostic information, so that LV function is likely not a meaningful additional prognosticator. In contrast, our hypothesis in this study was that LV deformation may allow refining prognostic information in the sPAH population, where RV function is already deteriorated to a degree that it portends equally poor prognosis and additional markers are needed to strategize treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study indicates that left heart dysfunction may play a mechanistic, clinically important role in sPAH. We believe the significance of LV dysfunction in sPAH is important to recognize and that reduced LV GLS is clinically relevant as a high-risk marker, specifically in patients with sPAH, in whom compromised RV function alone may no longer be sufficient as a prognostic marker. Accordingly, including this parameter in the echocardiographic follow-up of these patients may be beneficial in terms of strategizing treatment. This fact becomes even more pertinent when considering that the role of the LV until now has been largely overlooked.

HIGHLIGHTS.

In severe PAH and normal LVEF, LVGLS is independently associated with mortality.

RV free-wall strain and RA size were independently associated with death.

When stratified, LVGLS >−15% had the greatest association with mortality.

Abbreviations

- 2D

Two-dimensional

- BP

Blood pressure

- EI

Eccentricity index

- GLS

Global longitudinal strain

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LA

Left atrial

- LS

Longitudinal strain

- LV

Left ventricle, ventricular

- LVEF

LV ejection fraction

- MOD

Method of disks

- MR

Mitral regurgitation

- PA

Pulmonary arterial

- RA

Right atrial

- RV

Right ventricle

- sPAH

Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension

- TAPSE

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- TR

Tricuspid and regurgitation

- TTE

Transthoracic echocardiogram

- VC

Vena contracta

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Contributor Information

Kanako Kishiki, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Amita Singh, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Akhil Narang, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Mardi Gomberg-Maitland, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Virginia.

Neha Goyal, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Francesco Maffessanti, Institute of Computational Sciences, Università della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano, Switzerland..

Stephanie A. Besser, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Victor Mor-Avi, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Roberto M. Lang, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Karima Addetia, Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Celutkiene J, Bettex D, Bueno H, Chioncel O, et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 226–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freed BH, Gomberg-Maitland M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension with right ventricular failure: the left forgotten ventricle. Chest 2013;144: 1435–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardegree EL, Sachdev A, Fenstad ER, Villarraga HR, Frantz RP, McGoon MD, et al. Impaired left ventricular mechanics in pulmonary arterial hypertension: identification of a cohort at high risk. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:748–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkett DA, Slorach C, Patel SS, Redington AN, Ivy DD, Mertens L, et al. Left ventricular myocardial function in children with pulmonary hypertension: relation to right ventricular performance and hemodynamics. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haeck ML, Hoke U, Marsan NA, Holman ER, Wolterbeek R, Bax JJ, et al. Impact of right ventricular dyssynchrony on left ventricular performance in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;30:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puwanant S, Park M, Popovic ZB, Tang WH, Farha S, George D, et al. Ventricular geometry, strain, and rotational mechanics in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2010;121:259–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine NM, Chen L, Bastiansen PM, Frantz RP, Pellikka PA, Oh JK, et al. Outcome prediction by quantitative right ventricular function assessment in 575 subjects evaluated for pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:711–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37: 67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan T, Petrovic O, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H, Conley MJ, Armstrong WF. An echocardiographic index for separation of right ventricular volume and pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5:918–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thenappan T, Shah SJ, Rich S, Gomberg-Maitland M. A USA-based registry for pulmonary arterial hypertension: 1982–2006. Eur Respir J 2007;30: 1103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamatsu K, Takeuchi M, Nakai H, Nishikage T, Salgo IS, Husson S, et al. Effects of aging on left atrial function assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otani K, Takeuchi M, Kaku K, Haruki N, Yoshitani H, Tamura M, et al. Impact of diastolic dysfunction grade on left atrial mechanics assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:961–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manders E, Bogaard HJ, Handoko ML, van de Veerdonk MC, Keogh A, Westerhof N, et al. Contractile dysfunction of left ventricular cardiomyocytes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bustamante-Labarta M, Perrone S, De La Fuente RL, Stutzbach P, De La Hoz RP, Torino A, et al. Right atrial size and tricuspid regurgitation severity predict mortality or transplantation in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2002;15:1160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medvedofsky D, Aronson D, Gomberg-Maitland M, Thomeas V, Rich S, Spencer K, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation progression and regression in pulmonary arterial hypertension: implications for right ventricular and tricuspid valve apparatus geometry and patients outcome. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;18:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachdev A, Villarraga HR, Frantz RP, McGoon MD, Hsiao JF, Maalouf JF, et al. Right ventricular strain for prediction of survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2011;139:1299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]