Abstract

North America is in the midst of an overdose crisis. In some of the hardest hit areas of Canada, local responses have included the implementation of low-threshold drug consumption facilities, termed Overdose Prevention Sites (OPS). In Vancouver, Canada the crisis and response occur in an urban terrain that is simultaneously impacted by a housing crisis in which formerly ‘undesirable’ areas are rapidly gentrifying, leading to demands to more closely police areas at the epicentre of the overdose crisis. We examined the intersection of street-level policing and gentrification and how these practices re/made space in and around OPS in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. Between December 2016 and October 2017, qualitative interviews were conducted with 72 people who use drugs (PWUD) and over 200 hours of ethnographic fieldwork were undertaken at OPS and surrounding areas. Data were analyzed thematically and interpreted by drawing on structural vulnerability and elements of social geography. While OPS were established within existing social-spatial practices of PWUD, gentrification strategies and associated police tactics created barriers to OPS services. Participants highlighted how fear of arrest and police engagement necessitated responding to overdoses alone, rather than engaging emergency services. Routine policing near OPS and the enforcement of area restrictions and warrant searches, often deterred participants from accessing particular sites. Further documented was an increase in the number of police present in the neighbourhood the week of, and the week proceeding, the disbursement of income assistance cheques. Our findings demonstrate how some law enforcement practices, driven in part by ongoing gentrification efforts and buttressed by multiple forms of criminalization present in the lives of PWUD, limited access to needed overdose-related services. Moving away from place-based policing practices, including those driven by gentrification, will be necessary so as to not undermine the effectiveness of life-saving public health interventions amid an overdose crisis.

Keywords: harm reduction, overdose, place-based policing, safe consumption site, Canada

INTRODUCTION

Although North America’s overdose crisis is often framed as a consequence of the over-prescription of opioids (Madras, 2017), it is now understood that the crisis is primarily driven by the proliferation of fentanyl and fentanyl-adulterated drugs (Seth, Scholl, Rudd, & Bacon, 2018; Smolina et al., 2019). However, the epidemic is intimately linked with structural inequities (e.g. entrenched poverty, strained health care systems) (Dasgupta, Beletsky, & Ciccarone, 2018; Davis, Green, & Beletsky, 2017; McLean, 2016) in ways that disproportionately impact structurally vulnerable populations. Here, we define structural vulnerability as a marginalized position within a social hierarchy that renders particular populations or individuals (e.g. people who use drugs [PWUD], sex workers) more susceptible to forms of suffering due to social and structural violence (e.g. racism, gender inequities, poverty) (Farmer, Connors, & Simmons, 1996; Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011). The synergistic relationship between substance use and poverty is reinforced in spaces of advanced marginality (Wacquant, 2007) – that is, where a dearth of economic opportunity, spatial segregation, and an amplification of the criminal justice system reinforce inequity (Wacquant, 2008).

Areas of advanced marginality are often spatially bound and concentrated in urban neighbourhoods that are subsequently stigmatized (Wacquant, 2007). To regulate such marginality, including drug use, local governments have increasingly drawn on mechanisms of urban control (Merry, 2001; Smith, 1996; Wacquant, 2007). Such spatialized practices and strategies have aimed to regulate public spaces and displace, exclude, and incarcerate structurally vulnerable populations, including PWUD, through by-laws (e.g. anti-loitering ordinances) (Beckett & Herbert, 2008), the implementation of urban control strategies (e.g. security cameras, ‘community policing’) (Hermer & Mosher, 2002; Wallace, 1988), and socio-legal mechanisms such as area restrictions (i.e. court-ordered restrictions prohibiting an individual from re-entering an area where they were arrested) (Beckett & Herbert, 2009; McNeil, Cooper, Small, & Kerr, 2015; Sylvestre, Damon, Blomley, & Bellot, 2015). These mechanisms of urban control, however, are typically more pronounced in areas that are targeted for ‘revitalization’ or gentrification (i.e. the process of transforming vacant or low-income inner-city areas into economic, recreational, and residential use by middle- and upper- income individuals), and are thus intimately linked with broader economic, political, environmental, and social contexts (August, 2014; Blomley, 2004; Hackworth, 2006; Smith, 1996; Wallace, 1990). Given this, there is a need to understand how such mechanisms are connected to and reinforced by broader environmental milieus within the context of an urban public health crisis.

While street-level policing practices in street-based drug scenes are often cited as critical to limiting access to the drug supply and reducing violence and disorder (Aitken, Moore, Higgs, Kelsall, & Kerger, 2002; Maher & Dixon, 1999; Werb et al., 2011; Zimmer, 1990), they disproportionately target and impact racialized persons (Beletsky, 2018). Moreover, research has demonstrated how such models are not effective, but rather contribute to additional harms for PWUD, including increased violence (Cooper, 2015; Werb et al., 2011; Wood, Tyndall, et al., 2003). An extensive body of research has also highlighted the adverse impacts drug scene policing can have on the health of PWUD (e.g. Bluthenthal, Kral, Lorvick, & Watters, 1997; Cooper, Moore, Gruskin, & Krieger, 2005; Kerr, Small, & Wood, 2005; Maher & Dixon, 1999). Within this work, street policing has been associated with risks such as reduced access to harm reduction and ancillary services (Bluthenthal et al., 1997; Cooper et al., 2005; CS Davis, Burris, Kraut-Becher, Lynch, & Metzger, 2005; Werb et al., 2015; Wood, Kerr, et al., 2003), rushed injections (Cooper et al., 2005; Small, Kerr, Charette, Schechter, & Spittal, 2006; Werb et al., 2008), increase risk of overdose (Bohnert et al., 2011; Dovey, Fitzgerald, & Choi, 2001; Maher & Dixon, 1999), and an increased risk of disease transmission (Cooper et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2006; Werb et al., 2008). Given these factors, the continued use of place-based policing practices (e.g. increased police presence in specific areas, street checks, utilization of civil statutes), or policing that targets crime hot “spots” or segments of place (e.g. street blocks, buildings) (Eck & Weisburd, 1995; Weisburd, 2008), particularly within the context of a public health crisis, can negatively impact the health and well-being of structurally vulnerable PWUD and reinforce their susceptibility to harm. Importantly, it has been argued that to be effective, harm reduction interventions should be established in the settings where drug use occurs (Moore & Dietze, 2005). However, research has documented that these same spaces overlap with law enforcement presence (Bluthenthal et al., 1997; Cooper et al., 2005; CS Davis et al., 2005; T. Kerr, Small, et al., 2005). As such, there is a further need to understand the social-spatial practices of PWUD within these settings and how these spatial practices are altered by broader structural factors that contribute to the making and remaking of space (Duff, 2010).

Understanding these dynamics is particularly important across North America, where the current overdose crisis has led to the retrenchment of tactics utilized in the War on Drugs. This has included strategies targeting both the legal and illegal drug markets to reduce supply, such as prescription opioid monitoring systems, increased border policing, and an intensification of prosecuting and incarcerating drug dealers and other PWUD (e.g. drug-induced homicide charges) (Beletsky & Davis, 2017; C. Davis et al., 2017; Werb, 2018), which systematically target racialized persons (Beletsky, 2018). However, this supply-side focus, largely spurred by the view that the current overdose crisis is a ‘white opioid epidemic’ (Netherland & Hansen, 2016), is occurring alongside the implementation of – or in some instances, efforts to implement – overdose prevention interventions and evidence-based public health initiatives (e.g. widespread naloxone distribution, expanded access to opioid agonist therapies). Examining how these factors intersect given the potential for policing practices to shape the effectiveness of such interventions (Cooper et al., 2005; Werb et al., 2015; Wood, Kerr, et al., 2003) is thus needed.

These dynamics are particularly relevant in Vancouver, Canada, which has rolled out a robust overdose response effort, spearheaded by community activists, since December 2016. As part of these efforts, low-threshold drug consumption facilities – termed overdose prevention sites (OPS) – have been rapidly implemented (Collins, Bluthenthal, Boyd, & McNeil, 2018). OPS are staffed by peers or support workers, who administer naloxone and, in some locations, oxygen in the event of an overdose. Unlike sanctioned supervised consumption sites (SCS), OPS do not require federal approval as these have been implemented as temporary public health interventions amid a public health emergency by order of the provincial Ministry of Health. By pushing for overdose prevention interventions, and specifically OPS, activists, drug user-led groups, and public health officials have sought to create neighbourhood conditions that improve the ability for PWUD to use in safer environments in the context of a public health emergency (J. Boyd et al., 2018). Five OPS were opened in Vancouver by December 2016, all in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, with additional OPS opening in subsequent months.

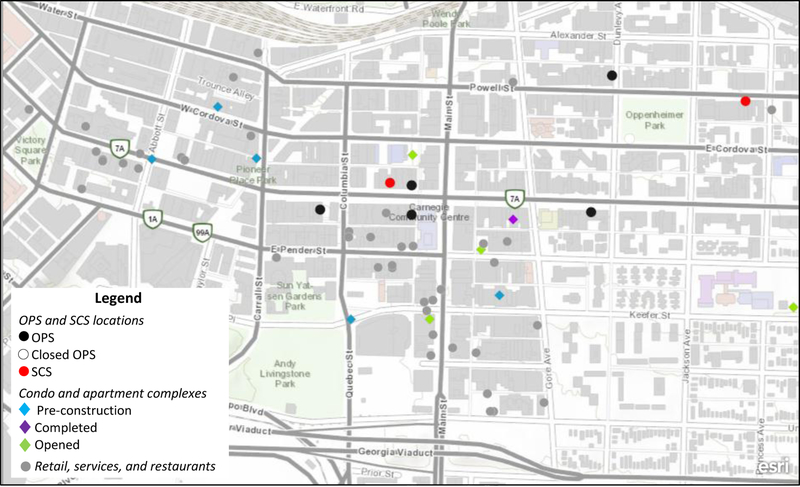

Vancouver’s OPS are largely clustered within the street-based drug scene, most visible through income generating activities (e.g. vending, drug selling, sex work). During the course of this study, all OPS established in Vancouver were situated in the most visible area of the drug scene and the epicenter of Vancouver’s overdose crisis, which also contains one of city’s SCS (see Figure 1). In addition to their close proximity to the SCS, three of the city’s OPS were integrated within existing services within an approximate one-block radius from the Street Market – a daily, community-driven vending space and one of the central points of the street economy. The Street Market acts as a social hub for many neighbourhood residents, in that it provides a space for income generating activities and socializing, while geographically overlapping with primary drug purchasing and consumption locales.

Figure 1.

Overdose prevention interventions in relation to gentrifying businesses

City of Vancouver, Province of British Columbia, Esri Canada, Esri, HERE, Garmin, INCREMENT P, Intermap, USGS, METI/NASA, EPA, USDA, AAFC, NRCan

*Map only includes a subsection of businesses, condos, and services opened in 2016 or later.

In addition to the robust public health response in the Downtown Eastside and the location of OPS in this study, the neighbourhood is also the site of increasing gentrification and ‘revitalization’ efforts aimed at meeting the growing demand for housing amid an ongoing housing crisis driven by factors such as external capital flows, an increasing population, and weak housing policies (Bardwell, Boyd, Kerr, & McNeil, 2018; Collins, Boyd, et al., 2018; Lee, 2016). Specifically, the Downtown Eastside is experiencing an influx of high-end condominiums whose placement overlaps with the main economies of the drug scene. Such gentrification efforts have also been paired with mechanisms of urban control, including private security guards, security cameras, and local policing (J. Kerr, 2018; Markwick, McNeil, Small, & Kerr, 2015). Given these overlapping practices, as well as inadequate social assistance rates (Klein, Ivanova, & Leyland, 2017), and the gentrification of low-income neighbourhoods like the Downtown Eastside, PWUD have experienced increasing housing instability (Bardwell, Fleming, Collins, Boyd, & McNeil, 2018; Collins, Boyd, et al., 2018; Fleming et al., 2019), with Vancouver’s homelessness rate having increased over 60% from 2005 to 2018 (Urban Matters CCC & BCNPHA, 2018). However, no research to date has examined the impact of neighbourhood-level policing on OPS utilization within the context of overlapping housing and overdose crises. Understanding the impacts of such urban social-spatial control is imperative to increasing the effectiveness of OPS as a response to a public health emergency.

To discern the impact of these neighbourhood changes, we undertook this study to examine how drug-scene policing practices intersected with the social-spatial practices of PWUD to shape the utilization of OPS implemented as part of a public health response. In doing so, we explore how law enforcement practices within a street-based drug scene contribute to the making and remaking of space, and the impact such space-making has on the health and well-being of PWUD.

METHODS

We undertook rapid ethnographic research between December 2016 and April 2017 as part of an established community-based research program in Vancouver. This research examined the implementation and utilization of OPS, focusing on structural forces (e.g. policing, territorial stigmatization) and the implications of such factors on the implementation and operation of OPS services within the broader neighbourhood. Conducting rapid ethnographic research has been highlighted as an important methodological adaptation within the context of public health emergencies (Johnson & Vindrola-Padros, 2017; Pink & Morgan, 2013). Further, when paired with community-based research methods, rapid qualitative research can more adequately advance understanding of concerns within the communities under study (McNall & Foster-Fishman, 2007).

The larger study included over 200 hours of observational fieldwork at OPS and surrounding areas conducted by team members and peer researchers. During fieldwork, informal and unstructured conversations occurred between team members and individuals accessing the OPS. After each session, detailed fieldnotes were written, which documented observations and interactions in relation to the implementation of OPS. Additional fieldwork was conducted by the lead author and two peer researchers during October 2017, to further elucidate social-spatial practices of PWUD in and around five OPS as part of this analysis. Fieldwork sessions were conducted in close proximity to OPS, including adjacent alleys and streets, and lasted between 2–3 hours. These sessions were spread out to cover various days of the week as well as times of day, including evening sessions. Fieldwork observation sheets specific to each location were developed to record physical and social information about the sites, including presence of security cameras, lighting, social-spatial practices of individuals in the area (e.g. sleeping, socializing, working), presence of police and first responders, as well as documenting overdose-related events. Each team member completed fieldwork observation sheets, which were reviewed together after the fieldwork session and used to construct more robust fieldnotes.

Additionally, semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted with 72 PWUD who were engaged in the street-based drug scene. Participants were recruited by team members, including peer researchers, directly from four OPS during fieldwork. After recruitment at the OPS, a peer researcher walked each participant back to our field office for the interview. An interview guide was used to facilitate discussion on topics such as experiences at OPS, overdose-related events, the impact of housing on OPS access, interactions with police, and income generating activities. Interviews lasted approximately 30 to 60 minutes, were audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim by a transcription service. After the interview, participants received $30 CAD honoraria for their time. Of the 72 participants, 43 identified as women (including three transgender and Two Spirit persons), 33 identified as Indigenous, and the average age was 42 years old (see Table 1). Additionally, 44 participants reported experiencing an overdose event in the last year and 13 participants reported being incarcerated in the two weeks prior to interview.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n=72)

| Participant characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean | 42 |

| Range | 20–64 years |

| Ethnicity | |

| Indigenous | 33 (45.8%) |

| White | 32 (44.4%) |

| Other (Hispanic, Black) | 7 (9.8%) |

| Gendera | |

| Women | 43 (59.8%) |

| Men | 29 (40.2%) |

| Transgender persons | 3 (4.2%) |

| Two Spirit personsb | 1 (1.4%) |

| Overdoses in past year | |

| One | 15 (20.8%) |

| Two | 10 (13.9%) |

| Three or more | 19 (26.4%) |

| Incarcerationc | |

| In the two weeks prior to interview | 13 (18.1%) |

| In the six months prior to interview | 10 (13.9%) |

| In the last year prior to interview | 9 (12.5%) |

| Current housing | |

| Apartment | 8 (11.2%) |

| Unstably housedc | 40 (55.5%) |

| Unsheltered | 24 (33.3%) |

Participants could select more than one response.

A non-binary and fluid term denoting Indigenous persons with both a masculine and feminine spirit, used to describe one’s gender or sexuality (Ristock, Zoccole, & Passante, 2010).

Defined as currently living in a single room accommodation hotel, shelter, hostel, or having no fixed address.

Written fieldnotes and interview transcripts were imported into NVivo qualitative software, where they were analyzed using the same coding framework. Initial coding frameworks were comprised of a priori categories derived from fieldnotes and the interview guide and emergent themes identified by the research team (Creswell, 2009). Throughout the analytical process, data were interpreted by drawing on structural vulnerability frameworks (Quesada et al., 2011) and elements of social geography related to the ‘disciplining’ of populations (Beckett & Herbert, 2008; Merry, 2001) to better understand the ways in which space was made and remade, and how this impacted the social-spatial practices of PWUD (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Duff, 2007). Pseudonyms were created using an online pseudonym generator and assigned to participants. ArcGIS online software by Esri was used to create the map, with geographic coordinates sourced from Google Maps. Ethical approval for this study was received from the Providence Healthcare/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

FINDINGS

Shifting social-spatial practices of daily life

Given their location within the larger drug scene, OPS were situated within the established social-spatial practices of structurally vulnerable PWUD as they overlapped with existing drug selling and consumption locations, low-income housing, health services, and other resources (e.g. food services, drop-in centres). Simultaneously, however, OPS locations also intersected with place-based policing efforts occurring within the same spaces, driven in large part, according to participants, by the rapid gentrification of the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. As a result, space immediate to OPS was continuously being constructed and reconstructed in ways that altered the ‘boundaries’ of the street-based drug scene. Strategies used to secure space in the neighbourhood included relocating PWUD further from areas where OPS were readily accessible through the displacement of dealers by law enforcement and a persistent police presence that participants described as “pushing” people back into alleys. Many participants described these placed-based policing practices as producing new “hotspots” of drug use and overdose risk as the drug scene was pushed eastward by new, gentrifying businesses entering the area. Additionally, changes to neighbourhood environment, including the installation of multiple, large flood lights in the alley behind the Street Market, also deterred people from accessing particular spaces as it increased their visibility. These intersecting policing and gentrification practices thus created additional displacement and barriers for certain participants, and contributed to the ever-evolving boundaries of the drug scene. In describing neighbourhood-level changes and their impact on PWUD, one participant explained:

There’s people being displaced all the time. They’re [i.e. cops] pushing us all – I don’t know where they’re going to put us, right? …Go down there and start walking up this way. You’ll see it. All brand new, all brand new, new and old mixed. And pretty soon that’ll be all – there’ll be no more old. (‘Matthew,’ 44-year-old Indigenous man)

Similarly, ‘Jason,’ a 56-year-old white man, described the impact of gentrification he saw within the neighbourhood in relation to the housing and overdose crises:

Part of what is going on…is that gentrification is happening. Things are changing and a new attitude moving in, new people and things like that. They don’t want things openly out there…open drug use around the park up and down the street, you don’t see that anymore. It’s in the alleys and the police will tolerate that more. […] I think there is a more overriding long-term agenda of moving people out of this area or at least making it so that they’re not as visible and stuff like that.

Both of these examples highlight the ways in which participants’ daily activities both constructed space and were shaped by the construction of space in the neighbourhood.

Given participants’ structural vulnerability, there was a need to regularly access public spaces which became more problematic as the neighbourhood changed. Specifically, the influx of high-income apartment complexes and condominiums, cafés and restaurants, and other retail spaces in the neighbourhood contributed to pervasive surveillance and place-based policing practices, which placed a strain on individuals who regularly engaged with this particular space as visible drug use became more contentious. As one participant described:

People are kind of getting pushed. Like they closed down one side of the street, but everybody just moved to the other side. …Now they started the little market for people to go there and sell their stuff, but you still see people out on the sidewalks selling all their shit. […] It’s hard to kind of put your finger on exactly what is going on. But I think also, with a lot of the trendier stores and stuff coming, like they don’t want people standing in front of your store, you know, smoking a crackpipe or shooting up or something, right? So you know, they frown upon that, which is understandable. But…people aren’t able to be as open about it as they used to be. (‘Laura,’ a 52-year-old white woman)

As Laura highlighted, the decreasing of accepted locations for these street-based economies by gentrification created challenges for participants who had to navigate this area to meet basic needs (e.g. food services, health services). Such efforts aimed at redefining the Downtown Eastside necessitated a renegotiation of participants’ social-spatial practices. It also underscores what participants described as a city-wide effort driven by policing practices and gentrification to dismantle their sense of place within the neighbourhood as their ability to access and engage with needed services became more challenging.

As made evident within these examples, the overlapping housing and overdose crises shifted the environment of the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood in a way that was at times contradictory to the overdose response. In particular, media coverage of the overdose crisis had spotlighted the neighbourhood, while additional city efforts (e.g. urban redevelopment, increased police visibility) simultaneously created barriers to particular spaces that could exacerbate drug-related harms. Importantly, gentrification practices in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood were intimately linked with policing. Specifically, an increase in complaints from surrounding businesses, residents, and visitors, incited heightened foot patrol within a main area of the street-based drug scene (Eagland, 2018; J. Kerr, 2018; Rabinovitch, 2018). Such policing practices by law enforcement, while implemented to increase a sense of safety for condo-owning residents, visitors, and business owners (Eagland, 2018; Rabinovitch, 2018), represent a more modern approach to urban policing in street-based drug scenes, aimed at altering the spatial patterns of PWUD. As such, the increased visibility of the neighbourhood due to its high-volume of overdoses and rapid response to the crisis through the implementation of OPS, was often undermined by the proliferation of law enforcement in the same area.

Zones of surveillance – policing around OPS

Mistrust and potential arrest

The majority of participants described having negative interactions with police in the neighbourhood at some point, which created a lack of trust. Such interactions were linked to participants’ structural vulnerability – including being harassed while using outside, being forcefully displaced while sleeping outside, and having tents, tarps, and other belongings disposed of while unhoused – and reinforced their marginality and drug-related risks. However, it is important to note that the City was complicit in such efforts, as municipal workers were often tasked with removing and disposing of individuals’ belongings as police stood by; a practice we regularly observed across the neighbourhood in parks, alleys, and on sidewalks. We also observed police regularly stopping and searching individuals, particularly Indigenous people and people of colour, within the drug-scene and within the immediate areas surrounding OPS, including blocking OPS alley entrances with a police car while searching individuals. For many participants, these interactions reinforced their mistrust of law enforcement, including their view that they disproportionately target particularly groups, and extended to their perceptions of the role of police within the overdose response. As one participant explained:

I think they’re [cops] a bunch of hypocrites. They’ll say one thing and then say something else, or do something else, when there’s no cameras around, right? …They just think of themselves better and us as just waste of space, waste of taxpayers’ money, just a waste. Right? For the most part, that’s the attitude that I get from them. (‘Mark,’ 53-year-old Black man)

As such, police surveillance created space in ways that was deemed unsafe by participants given the criminalization of drug use, which impacted how participants responded to overdoses and utilized OPS. Several participants recounted interactions they had with police during an overdose response, underscoring the potentially negative consequences such policing strategies could have for PWUD. This included leaving someone who was overdosing for fear of arrest or being the “fall guy” (i.e. blamed for someone’s overdose and facing subsequent legal consequences) in the case of a fatal overdose, with such narratives particularly common among racialized PWUD and those with histories with the criminal justice system. Additionally, participants described hesitation in engaging emergency medical services during overdose situations as they were uncertain whether police would also attend, and if they would run a warrant search upon arriving. ‘Brad,’ an OPS peer worker, explained:

I’ve seen people leave [the site] and then they come back into [the OPS] and then they’re like, ‘This guy OD’d outside, but his friends left.’ …They know that the police are going to show up. Maybe they have warrants.They just don’t want to be jacked up [i.e. searched by police] …so they just leave. (56-year-old Indigenous man)

Other participants reported aggressive interactions with police following overdose events. After responding to an overdose in an apartment building, ‘Michael’ described:

They [paramedics] were walking him down to the ambulance to take him to the hospital and there was the ambulance and there was a couple of police, and they were kind of like, you know, a little bit rude, eh? And I’ve experienced that before: ‘Just stand back! Stand back!’ But they want to know like, do you know this person, what you gave him…so I know the routines. As they work I stand back and just tell him what I know and what I gave him and stuff. […] One of the cops, he ran a CPIC [criminal record search] on me. …Maybe [he thought] I was his dealer or something. He should have asked who we are first, instead of jumping to conclusions, judging, right? That’s what some police do. (52-year-old Indigenous man)

Although the Vancouver police have a policy of non-attendance at overdoses unless advised to do so by emergency services (Vancouver Police Department, 2006a), their existing, heavy presence in various spaces left participants to choose between responding to an overdose alone, not responding, or responding with the assistance of emergency medical staff and potentially being arrested. As such, participants often chose to administer naloxone themselves and not call for emergency services as this was viewed as the safest response for both themselves and the person they were responding to within the broader context of drug criminalization.

Importantly, we observed an officer attend to an overdose call alongside a paramedic inside one of the OPS. While the officer’s assistance was requested by the paramedic, individuals accessing the service were visibly surprised and unsettled by the presence of law enforcement within a space they viewed as safe from arrest. Such remaking of space by the officer and the paramedic reinforced fears of arrest from the majority of those present, including individuals who were breaching area restrictions to access the service. This further highlights the ways in which the criminalization of drug use can undermine public health initiatives aimed at reducing overdose.

Alley patrol, cop cars, and open surveillance

While describing their engagement with OPS, participants noted how routine police surveillance occurred within the street-based drug scene and included the areas immediately surrounding OPS. Participants reported that police were “always just sitting in their cars just watching” and that “they’re on the street everywhere.” Routine police surveillance altered the social-spatial practices of participants by impacting their abilities to access certain OPS and pushing them into unsafe injecting environments, with racialized participants reporting the highest degree of surveillance. ‘Emily,’ a 25-year-old Indigenous woman, highlighted how police-implemented surveillance strategies increased drug- and health-related risks for PWUD:

I don’t trust them [cops] at all. And I do think that they are kind of preventing people from using in safe places, you know. Like they’re [PWUD] going further into unknown like empty alleys and where nobody could see them if they overdose. Well, if you’re like in the alley, let’s say, behind Insite, then at least there’s people around who could see you fall down or whatnot. […] But sometimes they [cops] park their cars in front of like Insite, and so nobody wants to be around there, right? So we’re going into unsafe alleys and whatnot.

As this participant highlighted, daily practices and engagement in space within the neighbourhood were also contingent upon the visibility of law enforcement officials. Another participant reiterated these sentiments:

There are certain areas that you don’t want to really be there because the cops will drive up and down and you never know what they are going to say or do. It is mostly [the 100 block] [i.e. the epicenter of the drug scene], but they do circle around pretty well all over the Downtown Eastside, but yeah, mostly in that area – there is a heavier presence in that area. (‘Melanie,’ 55-year-old white woman)

While participant narratives underscored the normalcy of police presence within the neighbourhood given its advanced marginality, tensions arose in relation to participants’ need to navigate highly-surveilled spaces to access OPS. For some participants, this created ongoing barriers to accessing specific sites, including the only site in which inhalation is allowed. As Brad, who both injected and smoked drugs, described:

Police cruise that alley [i.e. where an OPS entrance in located] a lot and there is a lot of drug dealers around, a lot of transactions, so the police are always patrolling that area …police are walking through, police are driving through. They could choose a different spot [for the OPS] maybe and have it taped off or something. A closed off area. [Having an OPS] inside is always the best. (56-year-old Indigenous man)

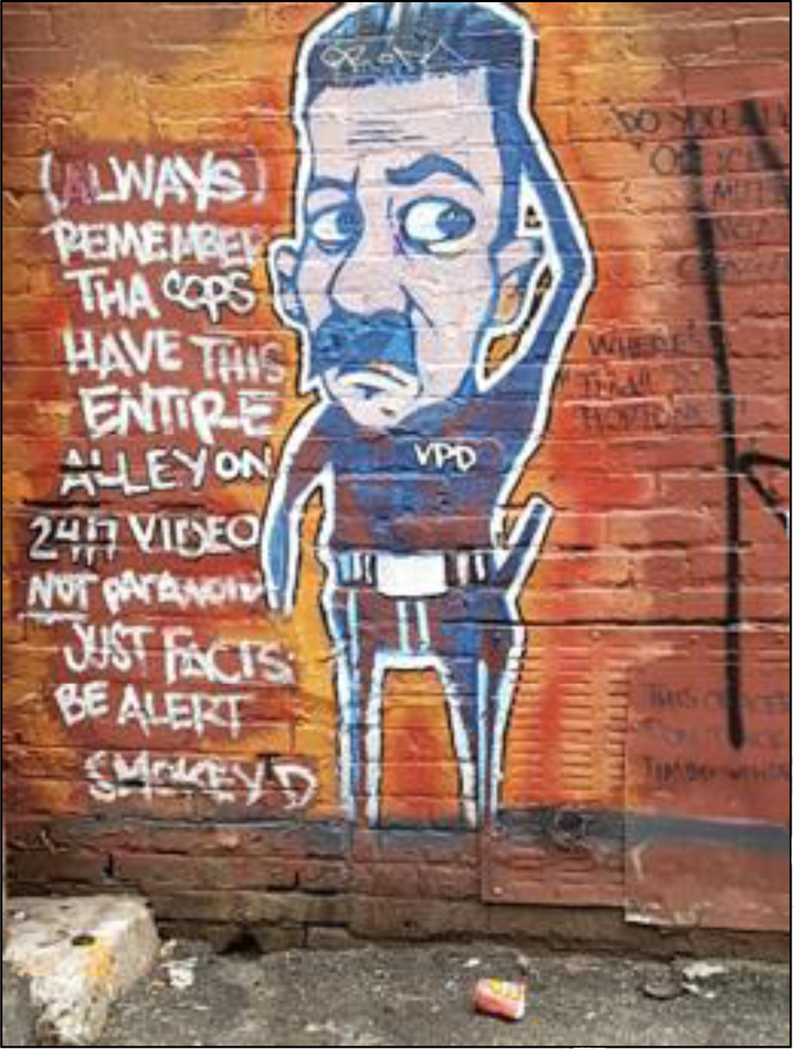

Despite the entrance being in the alley, which falls within most participants’ existing social-spatial practices and is thus widely accessed, this narrative magnifies the continuing visibility of such spaces due to police surveillance in the adjoining area. Such visibility was particularly worrisome for some participants at this OPS as it was established outside as a tent, and later trailer, and was thus viewed as more ‘open’ to police surveillance. While conducting fieldwork, we regularly observed police slowly driving through alleys both adjacent to and at OPS entrances and surrounding areas, or parking cars at alley entrances with the lights turned on. In these instances, individuals selling or using abruptly stopped, turned their backs, or left the area. These practices were further reflected by local graffiti. This particular alley was marked by a wall-sized mural of a police officer with a warning that “cops have this entire alley on 24/7 video” surveillance (see Figure 2). As such, these surveillance practices remade spaces in ways that increased risk of drug-related harms for structurally vulnerable individuals and were in conflict with public health efforts that were aimed at addressing the overdose crisis.

Figure 2.

Graffiti of policing in the alley behind the Street Market

Further, during fieldwork sessions conducted in and around OPS, more police presence was observed the week preceding and the week of cheque week (i.e. the week in which social assistance cheques are received). In these instances, surveillance tactics included drive-bys in alleys where OPS entrances were located, foot patrol around OPS, and parking police vehicles in close proximity to OPS. The increased observation of policing around cheque week has significant implications as drug use often increases during this time given the increase of income, and thus for some participants, an increased need to access safe spaces to use.

Red zones as barriers to OPS engagement

For others, however, law enforcement techniques such as area restrictions or “red zones” (McNeil et al., 2015) prevented participants’ access to needed services as they could subsequently be arrested if seen by police within these spaces. In these instances, participants’ approaches to navigating these zones of exclusion varied, including keeping their distance as well as covert navigation. ‘Joshua,’ a 32-year-old Black man who had only accessed one OPS, explained: “I’ve heard about them [other OPS] but it’s in my red zone. I’m red zoned from the whole Downtown Eastside.” As such, this participant reported using “mostly on the street” now as he had been incarcerated within the two weeks prior to the interview.

Other participants who were currently red zoned described needing to re-engage with prior social-spatial practices in the neighbourhood to reduce their risk of overdose and other health-related harms. In doing so, these participants actively challenged law enforcement tactics that not only shaped space, but also restricted their movements, as this was perceived as vital to staying alive. One participant, ‘Shawn,’ described using “lots in the alley” despite not feeling safe there. Continuing, Shawn shared how he negotiates the complexity of area restrictions and overdose prevention:

I got a red zone so I’m not allowed to be in a certain area. […] It’s the areas that I want to go to and use and all the accessibility and all the sites that I need or want to access – they’re all in my red zone. […] Like, I’m not supposed to be in certain areas, but I’m there… I feel safer in the injection sites than I do just like in the alley…I know that the cops there will let you use. You’re allowed to use there and the cops acknowledge that and they won’t look twice at you if you’re in there. (43-year-old South Asian man)

Although OPS are off-limits from police interference related to drug law enforcement, and thus seen as ‘safer,’ policing practices, including patrolling areas around OPS and implementing red zones, continued to impede OPS access, particularly for participants who had area restrictions. This retention of social-spatial practices, despite the constant surveillance of the same zone, was viewed as imperative to reduce drug- and health- related harms for participants.

DISCUSSION

Although established within the existing social-spatial practices of PWUD in the neighbourhood, ongoing ‘revitalization’ efforts intersected with law enforcement measures re/making space in ways that created barriers to needed harm reduction services for participants. Given participants’ structural vulnerability, including factors such as housing instability, types of work (e.g. sex work, drug dealing), and involvement in the street-based drug scene, they were more susceptible to placed-based policing practices. In particular, increased visibility of law enforcement and surveillance undertaken in the same areas as OPS discouraged participants from engaging in the street-based drug scene and incited fears of arrest. As such, despite OPS serving as safer environments to consume drugs amid an overdose crisis, drug-scene policing practices (e.g. neighbourhood sweeps, foot patrol) created barriers to engagement for many participants, reinforcing their structural vulnerability and increasing their risk of drug-related harm.

Other research has highlighted how despite supervised consumption sites (SCS) providing a safer place to use drugs away from police (Fairbairn, Small, Shannon, Wood, & Kerr, 2008; McNeil, Small, Lampkin, Shannon, & Kerr, 2014; Small, Moore, Shoveller, Wood, & Kerr, 2012), policing around SCS and other harm reduction services can impede access and reduce PWUD’s ability to engage in risk reduction practices (Cooper et al., 2005; Kerr, Oleson, Tyndall, Montaner, & Wood, 2005; Kimber & Dolan, 2007; Petrar et al., 2007; Werb et al., 2008). This study expands on these findings by highlighting how the process of gentrification led to evolving expectations and influence on space by new occupants (i.e. business and condo owners, visitors), which was operationalized through the mobilization of police against existing residents, and specifically, PWUD. Of note, condo owners filed complaints with the Vancouver Police Department (VPD), requesting additional officers be deployed to address crime, street disorder, and public safety in the Downtown Eastside (Rabinovitch, 2018). As documented, this included place-based policing practices and surveillance – as well as “above minimal staffing levels” in the Downtown Eastside (Rabinovitch, 2018, p.5) – which directly interfered with an emergency public health response in ways that can increase drug- and overdose-related risk for PWUD. Importantly, community activists, drug user-led organizations, and public health officials pushed for the rapid implementation of OPS in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood (J. Boyd et al., 2018; Collins, Bluthenthal, et al., 2018), thereby creating safer neighbourhood conditions for PWUD to use. However, as gentrification is occurring within the same areas as OPS, the shifting population risks undermining life-saving interventions by influencing policing. Unlike other forms of urban policing (e.g. ‘broken windows’ policing) (Beckett & Herbert, 2008), these findings demonstrate a form of place-based policing that is driven by gentrification, instigated by newcomer residents, visitors, and business owners, and thereby aligned with more longstanding and emerging police practices targeting PWUD even amidst an overdose crisis. Significantly, policing efforts that reinforced displacement in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood necessitated a renegotiation of participants’ daily social-spatial practices that often included more clandestine drug use that exacerbated risk as provincially-supported overdose prevention interventions were made inaccessible. As such, placed-based policing within this setting was found to increase risk of overdose and other drug-related harms for PWUD as it required them to use in less visible areas (e.g. alleyways, single room accommodations).

In line with previous research on the impact of policing strategies on health outcomes (Bohnert et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2005; CS Davis et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2006; Markwick et al., 2015; McNeil et al., 2015; Small et al., 2006; Werb et al., 2011) and engagement with SCS (Kerr, Oleson, et al., 2005), our findings highlight how policing mechanisms designed to promote safety can inadvertently intensify harms for PWUD. Similar outcomes were highlighted in previous research, as PWUD sought to evade police surveillance occurring in and around a SCS in Vancouver (Kerr, Oleson, et al., 2005). Our research illustrates how place-based policing practices within the epicenter of the province’s overdose crisis can exacerbate the overdose-related risks and harms faced by structurally vulnerable PWUD as they feared arrest in particular spaces, thus limiting the effectiveness of harm reduction interventions.

The increase in police surveillance experienced within the Downtown Eastside was implemented to increase neighbourhood safety (Rabinovitch, 2018; Vancouver Police Department, 2018a). However, this study has illustrated the unintended consequences of visible police presence within the drug scene, as it represents a threat to participants aiming to access OPS, and thus alters where they consume drugs. Such implications can increase risk of harms for PWUD and limit the coverage of OPS. Despite the VPD’s open support of evidence-based harm reduction (Vancouver Police Department, 2006b), our findings underscore how police efforts to increase neighbourhood safety reinforce the marginalization of PWUD in the same neighbourhood as they sought to avoid police. The scope of policing in the Downtown Eastside under the Beat Enforcement Team (BET) (i.e. targeted police force in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood) compared to other policing districts in Vancouver, further illustrates how particular populations are targeted. For example, from 2008–2014, there were 4,301 recorded municipal bylaw infractions (e.g. street vending, public urination) in the Downtown Eastside, compared to 2,448 elsewhere in Vancouver (Vancouver Police Department, 2015). Moreover, Indigenous and racialized persons, particularly Indigenous women, are disproportionately impacted by street checks (i.e. the stopping, questioning, and recording individuals when no specific offence is being investigated) (Vancouver Police Department, 2018b). Such racialized policing practices may partially explain disparities in overdose deaths within the local context, in which Indigenous persons are the most impacted (First Nations Health Authority, 2017). Given these diverse ways in which particular populations are targeted by policing efforts in Vancouver, and despite the VPD’s stated support of harm reduction, people will remain fearful of police interactions so long as drugs remain criminalized and other forms of policing and surveillance are deployed in ways that disproportionately target PWUD. As such, it is critical to rethink place-based policing practices as these can directly interfere with evidence-based harm reduction services aimed at addressing an overdose crisis.

Given these factors, this research suggests a reconfiguration of urban policing, in which socio-legal and spatial forms of urban control (e.g. area restrictions, gentrification, police surveillance) (Beckett & Herbert, 2008; Foucault, 1991; Merry, 2001; Sylvestre et al., 2015) both intersect with and impact upon a public health emergency and responses. This is particularly problematic given that ‘disciplining’ strategies (e.g. surveillance) are implemented in such a way – and in such a space – that they not only reinforce the marginalization and structural vulnerability of PWUD, but increase their risk of morbidity and mortality by frequently rendering OPS inaccessible. While research has illustrated similar contemporary approaches to policing urban spaces elsewhere (e.g. Bancroft, 2012; Draus, Roddy, & Asabigi, 2015; Pennay, Manton, & Savic, 2014), this research highlights how place-based policing tactics still persist even within a public health emergency. As such, this research illustrates how many participants must continuously negotiate a risk of arrest or a risk of overdosing alone, and how such tension is exacerbated for individuals who have current area restrictions or outstanding warrants. Although previous research has demonstrated that public health and police partnerships can be beneficial in connecting PWUD with harm reduction services (DeBeck et al., 2008), our research illustrates that such practices undermine the ability for PWUD to engage in risk reduction amid a public health crisis. There is thus an urgent need to abandon place-based policing practices utilized within street-based drug scene settings.

As participant narratives demonstrated efforts to undermine these overlapping practices by remaking space, there remains a need to revisit law enforcement strategies, including the discontinuation of red zones and ending police surveillance near OPS, so as to increase accessibility of OPS for PWUD and decrease risk of harm. In particular, participants’ accounts underscore the urgent need to decriminalize drug use as the risk of punitive repercussions weakens the effectiveness of public health interventions. In 2017, 72% of drug-related arrests in Canada were for personal possession of criminalized drugs (e.g. opioids, heroin) (S. Boyd, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2018) and, even as the VPD has stated publicly that arrest for possession is not a priority (Lupick, 2019), there was a slight increase in drug-related arrests in Vancouver (297 as of September 2018) (BC Coroners Service, 2018; S. Boyd, 2018). Importantly, these statistics still fail to capture the scope of policing in relation to PWUD, as documented in our study (e.g. red zoning, street checks, warrant searches). Such patterns further underscore the need to decriminalize drug use and possession, and shift resources away from policing efforts to areas more likely to reduce the unprecedented harms of the overdose crisis (e.g. harm reduction services, housing). This can be further substantiated by revising the Good Samaritan Act to provide adequate legal protection for individuals who call emergency services during an overdose event who have an outstanding warrant (Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act, 2017). Given the heavy police presence in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, there remains an ongoing risk of police being at the scene of an overdose. In these cases, we recommend police not get involved – including, not running warrants, arresting, or searching individuals – unless it is to administer naloxone. While this research is specific to Vancouver, the harmful impacts of policing in drug economies has also been established in other settings (Beletsky et al., 2014; CS Davis et al., 2005; Hayashi, Small, Csete, Hattirat, & Kerr, 2013; Maher & Dixon, 2001; Rhodes et al., 2006; Werb et al., 2011). As such, our findings may be applicable to other urban areas with street-based drug scenes working to establish overdose prevention interventions.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, this study includes data from four OPS that were established at the start of this study. As such, findings may not be representative of experiences in and around other OPS that have since been implemented. Additionally, transgender and two-spirit persons were underrepresented in this study, and thus findings may not be representative of their experiences. Because participants were recruited directly from OPS, the experiences of PWUD who were red zoned from the neighbourhood are likely not fully represented.

Despite these limitations, this study furthers our understandings of how street-based drug scene policing practices can re/make space in ways that increase experiences of harm for PWUD. Similar to previous research (Wallace, 1988, 1990), this work underscores how the political economy of the city can exacerbate the health- and drug-related outcomes experienced by PWUD. Moreover, these findings add to the literature on policing in areas being ‘revitalized’ (e.g. Smith, 1996; Wacquant, 2007) to demonstrate how law enforcement practices working alongside gentrification efforts can undermine the implementation of needed health and ancillary services for PWUD. Considering how surveillance and policing in spaces that overlap with harm reduction services may contribute to additional risks for PWUD amid an overdose crisis is essential. However, abandoning urban control strategies that undermine the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions, including drug scene surveillance, area restrictions, and drug criminalization, are critical to addressing the overdose crisis in a more effective way.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution as well as current and past staff and research assistants at the British Columbia Centre for Substance Use for their administrative and research assistance. This study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA044181). Alexandra Collins is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. Jade Boyd is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (PJT-155943). Mary Clare Kennedy is supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Award. Ricky Bluthenthal is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DA038965). Thomas Kerr is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant (20R74326). Ryan McNeil is supported through a CIHR New Investigator Award and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

None.

Declaration of interests

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Conflicts of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitken C, Moore D, Higgs P, Kelsall J, & Kerger M. (2002). The impact of a police crackdown on a street drug scene: evidence from the street. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- August M. (2014). Negotiating social mix in Toronto’s first public housing redevelopment: power, space and social control in Don Mount Court. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1160–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft K. (2012). Zones of exclusion: urban spatial policies, social justice, and social services. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 39(3), 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Boyd J, Kerr T, & McNeil R. (2018). Negotiating space and drug use in emergency shelters with peer witness injection programs within the context of an overdose crisis: a qualitative study. Health & Place, 53, 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Fleming T, Collins A, Boyd J, & McNeil R. (2018). Addressing intersecting housing and overdose crises in Vancouver, Canada: opportunities and challenges from a tenant-led overdose response intervention in single room occupancy hotels. Journal of Urban Health, e-pub ahea, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Coroners Service. (2018). Illicit drug overdose deaths in BC - January 1, 2018 - September 30, 2018. Vancouver.

- Beckett K, & Herbert S. (2008). Dealing with disorder: social control in the post-industrial city. Theoretical Criminology, 12(1), 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett K, & Herbert S. (2009). Banished: the new social control in urban America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L. (2018). America’s favorite antidote: drug-induced homicide in the age of the overdose crisis. SSRN, (May 18). [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, & Davis C. (2017). Today’s fentanyl crisis: prohibition’s iron law, revisited. International Journal of Drug Policy, 46, 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Heller D, Jenness S, Neaigus A, Gelpi-Acosta C, & Hagan H. (2014). Syringe access, syringe sharing and police encounters among people who inject drugs in New York City: a community-level perspective. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(1), 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomley N. (2004). Unsettling the city: urban land and the politics of property. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal R, Kral A, Lorvick J, & Watters J. (1997). Impact of law enforcement on syringe exchange programs: a look at Oakland and San Francisco. Medical Anthropology, 18(1), 61–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A, Nandi A, Tracy M, Cerda M, Tardiff K, Vlahov D, & Galea S. (2011). Policing and risk of overdose mortality in urban neighbourhoods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 113(1), 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Collins A, Mayer S, Maher L, Kerr T, & Mcneil R. (2018). Gendered violence and overdose prevention sites: a rapid ethnographic study during an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction, 113(12), 2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd S. (2018). Drug use, arrests, policing, and imprisonment in Canada and BC, 2015–2016. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Bluthenthal R, Boyd J, & McNeil R. (2018). Harnessing the language of overdose prevention to advance evidence-based responses to the opioid crisis. International Journal of Drug Policy, 55, 77–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Boyd J, Damon W, Czechaczek S, Krüsi A, Cooper H, & McNeil R. (2018). Surviving the housing crisis: social violence and the production of evictions among women who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Health & Place, 51, 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. (2015). War on drugs policing and police brutality. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(8–9), 1188–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, & Krieger N. (2005). The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: a qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine, 61(3), 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. (2009). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Washington, DC: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, & Ciccarone D. (2018). Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), 182–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Burris S, Kraut-Becher J, Lynch K, & Metzger D. (2005). Effects of an intensive street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia, PA. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 233–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Green T, & Beletsky L. (2017). Action, not rhetoric, needed to reverse the opioid overdose epidemic. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 45(S1), 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall M, Montaner J, & Kerr T. (2008). Police and public health partnerships: evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 3, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze G, & Guattari F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K, Fitzgerald J, & Choi Y. (2001). Safety becomes danger: Dilemmas of drug-use in public space. Health and Place, 7(4), 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, Roddy J, & Asabigi K. (2015). Streets, strolls and spots: sex work, drug use and social space in Detroit. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(453–460). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C. (2007). Towards a theory of drug use contexts: space, embodiment and practice. Addictions Research & Theory, 15(5), 503–519. [Google Scholar]

- Duff C. (2010). Enabling places and enabling resources: new directions for harm reduction research and practice. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagland N. (2018, February 4). Advocates fear Downtown Eastside police crackdown pushes drug users into shadows. Vancouver Sun. [Google Scholar]

- Eck J, & Weisburd D. (1995). Crime places in crime theory In Eck J & Weisburd D. (Eds.), Crime and Places (pp. 1–33). Monsey: Criminal Justice Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Small W, Shannon K, Wood E, & Kerr T. (2008). Seeking refuge from violence in street-based drug scenes: women’s experiences in North America’s first supervised injection facility. Social Science and Medicine, 67(5), 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P, Connors M, & Simmons J. (1996). Women, poverty, and AIDS: sex, drugs, and structural violence. (Farmer P, Connors M, & Eds SJ.). Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Health Authority. (2017). Overdose data and First Nations in BC. West Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T, Damon W, Collins A, Czechaczek S, Boyd J, & McNeil R. (2019). Housing in crisis: a qualitative study of the socio-legal contexts of residential evictions in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. International Journal of Drug Policy, Forthcomin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. (1991). Governmentality In Burchell G, Gordon C, & Miller P. (Eds.), The Foucault Effect: studies in governmentality (pp. 87–104). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Cooper H, Tempalski B, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom P, & Des Jarlais D. (2006). Relationships of deterrence and law enforcement to drug-related harms among drug injectors in US metropolitan areas. AIDS, 20(1), 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act (2017). Retrieved from http://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/C-224/royal-assent#enH39

- Hackworth J. (2006). The neoliberal city: governance, ideoilogy and development of American urbanism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Small W, Csete J, Hattirat S, & Kerr T. (2013). Experiences with policing among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: a qualitative study. PLoS Medicine, 10(12), e1001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermer J, & Mosher J. (2002). Disorderly people: law and the politics of exclusion in Ontario. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G, & Vindrola-Padros C. (2017). Rapid qualitative research methods during complex health emergencies: A systematic review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 189, 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. (2018, January 31). Vancouver police increase presence in the Downtown Eastside. Vancouver Courier; Retrieved from https://www.vancourier.com/news/vancouver-police-increase-presence-in-the-downtown-eastside-1.23160339 [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Oleson M, Tyndall M, Montaner J, & Wood E. (2005). A description of a peer-run supervised injection site for injection drug users. Journal of Urban Health, 82(2), 267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, & Wood E. (2005). The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: a review of the evidence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16, 210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J, & Dolan K. (2007). Shooting gallery operation in the context of establishing a medically supervised injecting center: Sydney, Australia. Journal of Urban Health, 84, 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Ivanova I, & Leyland A. (2017). Long overdue: why BC needs a poverty reduction plan. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. (2016). Getting serious about affordable housing: towards a plan for metro Vancouver. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Lupick T. (2019, March 12). Vancouver police stats suggest a softer touch on drugs but users say it’s a different story on the streets. Georgia Straight. [Google Scholar]

- Madras B. (2017). The surge of opioid use, addiction, and overdoses: responsibility and response of the US health care system. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 441–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, & Dixon D. (1999). Policing and public health: law enforcement and harm minimisation in a street-level drug market. British Journal of Criminology, 39, 488–511. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, & Dixon D. (2001). The cost of crackdowns: policing Cabramatta’s heroin market. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 13(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Markwick N, McNeil R, Small W, & Kerr T. (2015). Exploring the public health impacts of private security guards on people who use drugs: a qualitative study. Journal of Urban Health, 92(6), 1117–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K. (2016). “There’s nothing here”: deindustrialization as risk environment for overdose. International Journal of Drug Policy, 29, 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNall M, & Foster-Fishman P. (2007). Methods of rapid evaluation, assessment and appraisal. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(2), 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Cooper H, Small W, & Kerr T. (2015). Area restrictions, risk, harm, and health care access among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada: a spatially oriented qualitative study. Health and Place, 35, 70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, & Kerr T. (2014). “People knew they could come here to get help”: an ethnographic study of assisted injection practices at a peer-run ‘unsanctioned’ supervised drug consumption room in a Canadian setting. AIDS and Behavior, 18(3), 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry S. (2001). Spatial governmentality and the new urban social order: controlling gender violence through law. American Anthropologist, 103(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Moore D, & Dietze P. (2005). Enabling environments and the reduction of drug-related harm: re-framing Australian policy and practice. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24(3), 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherland J, & Hansen H. (2016). The war on drugs that wasn’t: wasted whiteness, “dirty doctors,” and race in media coverage of prescription opioid misuse. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 40(4), 664–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennay A, Manton E, & Savic M. (2014). Geographies of exclusion: Street drinking, gentrification and contests over public space. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(6), 1084–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrar S, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Zhang R, Montaner J, & Wood E. (2007). Injection drug users’ perceptions regarding use of a medically supervised safer injecting facility. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1088–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink S, & Morgan J. (2013). Short-term ethnography: intense routes to knowing. Symbolic Interaction, 36(3), 351–361. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, & Bourgois P. (2011). Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology, 30(4), 339–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch R. (2018). Service or Policy Complaint #2018–132 Regarding Perceived Funding Cuts and the Resultant Public Safety Issues in the Downtown Eastside. Vancouver. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/police/policeboard/agenda/2018/0926/SP-5-2-1809C03.pdf

- Rhodes T, Platt L, Sarang A, Vlasov A, Mikhailova L, & Monaghan G. (2006). Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: a qualitative study of police perspectives. Journal of Urban Health, 83(5), 911–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristock J, Zoccole A, & Passante L. (2010). Aboriginal two-spirit and LGBTQ migration, mobility and health research project: final report. Winnipeg. [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd R, & Bacon S. (2018). Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants – United States, 2015–2016. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter M, & Spittal P. (2006). Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy, 17, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Moore D, Shoveller J, Wood E, & Kerr T. (2012). Perceptions of risk and safety within injection settings: injection drug users’ reasons for attending a supervised injecting facility in Vancouver, Canada. Health, Risk & Society, 14, 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. (1996). The new urban frontier: gentrification and the revanchist city. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smolina K, Crabtree A, Chong M, Zhao B, Park M, Mill C, & Schutz C. (2019). Patterns and history of prescription drug use among opioid-related drug overdose cases in British Columbia, Canada, 2015–2016. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 194, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2018). CANSIM Table 35–10-0184–01 Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, police services in British Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre M, Damon W, Blomley N, & Bellot C. (2015). Spatial tactics in criminal courts and the politics of legal technicalities. Antipode, 47(5), 1346–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Matters CCC, & BC Non-Profit Housing Association. (2018). Vancouver Homeless Count 2018. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver Police Department. (2006a). Guidelines for police attending illicit drug overdoses In Vancouver Police Department: Regulations and Procedures Manual (p. 154). Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver Police Department. (2006b). Vancouver Police Department drug policy. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver Police Department. (2015). Municipal bylaw data. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver Police Department. (2018a). Vancouver police work to increase safety in the Downtown Eastside [Media Release]. Vancouver. Retrieved from https://mediareleases.vpd.ca/2018/01/30/vancouver-police-work-to-increase-safety-in-the-downtown-eastside/

- Vancouver Police Department. (2018b). VPD Street Check Data 2008–2017 by Gender and Ethnicity Fields. Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. (2007). Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality. Thesis Eleven, 91(1), 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. (2008). Urban outcasts: a comparative sociology of advanced marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. (1988). A synergism of plagues, planned shrinkage, contagious housing destruction, and AIDS in the Bronx. Environmental Research, 47, 1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R. (1990). Urban desertification, public health and public order: ‘planned shrinkage’, violent death, substance abuse and AIDS in the Bronx. Social Science & Medicine, 31(7), 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D. (2008). Place-based policing. Ideas in American Policing (Vol. 9). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Werb D. (2018). Post-war prevention: emerging frameworks to prevent drug use after the War on Drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 51, 160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Rowell G, Guyatt G, Kerr T, Montaner J, & Wood E. (2011). Effect of drug law enforcement on drug market violence: a systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 22(2), 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Wagner K, Beletsky L, Gonzalez-Zuniga P, Rangel G, & Strathdee S. (2015). Police bribery and access to methadone maintenance therapy within the context of drug policy reform in Tiuana, Mexico. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Wood E, Small W, Strathdee S, Li K, Montaner J, & Kerr T. (2008). Effects of police confiscation of illicit drugs and syringes among injection drug users in Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19(4), 332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Jones J, Schechter M, & Tyndall M. (2003). The impact of police presence on access to needle exchange programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 34(1), 116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall M, Spittal P, Li K, Anis A, Hogg R, … Schechter M. (2003). Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: investigation of a massive heroin seizure. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(2), 165–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer L. (1990). Proactive policing against street-level drug trafficking. American Journal of Police, 9(43) [Google Scholar]