Abstract

Organized after-school programs can mitigate risk and build resilience for youth in urban communities. Benefits rely on high-quality developmental experiences characterized by a supportive environment, structured youth–adult interactions, and opportunities for reflective engagement. Programs in historically disenfranchised communities are underfunded; staff are transient, underpaid, and undertrained; and youth exhibit significant mental health problems which staff are variably equipped to address. Historically, after-school research has focused on behavior management and social-emotional learning, relying on traditional evidence-based interventions designed for and tested in schools. However, after-school workforce and resource limitations interfere with adoption of empirically supported strategies and youth health promotion. We have engaged in practice-based research with urban after-school programs in economically vulnerable communities for nearly two decades, toward building a resource-efficient, empirically informed multitiered model of workforce support. In this paper, we offer first-person accounts of four academic– community partnerships to illustrate common challenges, variability across programs, and recommendations that prioritize core skills underlying risk and resilience, align with individual program goals, and leverage without overextending natural routines and resources. Reframing obstacles as opportunities has revealed the application of mental health kernels to the after-school program workforce support and inspired lessons regarding sustainability of partnerships and practice.

Keywords: After-school programs, Urban, Poverty, Workforce support, Public health

Nearly two decades ago, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation increased teacher accountability for children’s grade-level achievement, bringing higher demands and competing priorities to schools. A slow but steady narrowing of curriculum followed, accompanied by diminishing time for classroom social-emotional programming. Ongoing enthusiasm for social-emotional learning (SEL) led to a cornucopia of life skills, character development, and prevention programs designed and tested with schools in mind. At the same time, mounting data pointed to the value and opportunity of after-school programs (ASP) as a place for positive youth development. Enrollment in community-based ASP has increased steadily among children of low-income households, and demand for programming is consistently highest among families of color (Afterschool Alliance, 2014). In this paper, we offer first-person accounts of four academic–community partnerships, revealing common challenges and variability in ASP across two cities and two decades, and illustrating a multitiered approach to workforce support, infused with mental health kernels of influence. Overall, our goal is to share lessons, that continue to inspire our ongoing work, about entering partnerships with humility, engaging in both teaching and learning, and appreciating the value of turning obstacles into opportunities.

A Brief Primer on ASP

Increased reliance over time on organized ASP reflected a shifting educational landscape, growing labor market, and changing economy characterized by more working families requiring after-school childcare. ASP materialized to provide safe, supervised places for homework and play. With a narrowing curriculum in schools came a widespread reduction of recess and extra-curricular classes, including art, music, and physical education, all of which found a new home after school. Still, the expectation for ASP to contribute meaningfully to youth development remained low; parents, particularly those of low-income and ethnic/racial minority families, were satisfied for children to be safe, supervised, and completing homework (Duffett, Johnson, Farkas, Kung, & Ott, 2004); Sanderson & Richards, 2010). Low expectations for ASP quality coincided with a persistent lack of local or federal investment (Afterschool Alliance, 2014), resulting in a transient after-school workforce that remains under-resourced, inadequately trained, and often overwhelmed by children’s social-emotional difficulties manifesting in significant rates of disruptive and disengaged behaviors. In turn, after-school mental health research has focused to a large extent on behavior management.

Investigators borrowed school-based behavior interventions that now feature prominently in the after-school literature (e.g., Smith, Osgood, Oh, & Caldwell, 2018), with many requiring significant time, training and technical assistance for effective implementation and impact. Our own efforts to simplify and transport behavioral tools (Frazier, Cappella, & Atkins, 2007) revealed the great extent to which ASP differ from schools and vary in design and delivery. Observed variability appeared to be reflected in program characteristics (e.g., setting, mission, curriculum), organizational policies and procedures (e.g., roles, management, training), and workforce (e.g., education, experience). Such variability also has been documented in case studies (Baldwin & Wilder, 2014) and may help to explain inconsistent findings regarding the benefits of ASP for children’s academic, health, and behavior trajectories. These differences made salient for us the considerable challenges of moving school-based interventions to after-school settings.

A closer look at program variability reveals an overall low investment in fiscal, material, and human resources; significant discrepancies in resources across states, counties, and school districts; and regular shifts in budgets and institutional priorities (Afterschool Alliance, 2006). Programs commonly rely on multiple funding “strands,” though parent tuition and fees account for the majority of costs (~76%), including programs serving low-income communities (~54%). Unpredictable funding year to year interferes with workforce development (e.g., hiring, training, compensation) and curriculum planning, and influences enrollment and staff-to-child ratios. Relatedly, material resources also can fluctuate over time and across programs. While existing literature characterizing the logistic challenges of ASP is scarce, our experience in two major cities over the last two decades indicates that space, equipment, and supplies are often in short supply, and access to online resources is limited in programs with poor reception or no Wi-Fi, particularly in communities of poverty.

Most relevant to workforce support is what we know about community “youth professionals” from national survey data (1000+ respondents in eight cities across the U.S.) that reveal they are “relatively young” (59% under age 35), mostly women (70%) and African-American (59%), with 60% having completed at least a 2-year college degree and fewer than half reporting previous education, childcare, or related social service experience (Yohalem, Pittman, & Moore, 2006). ASP staff spend nearly all of their paid hours working directly with children, limiting time for activity planning or problem-solving, and minimizing opportunities for training and supervision that accompany manualized prevention programs. Moreover, their responsibilities inherently require broad knowledge related, at minimum, to education, recreation, and youth development (Baldwin & Wilder, 2014).

Absent requirements for education or experience, and with few options for career advancement, after-school providers represent a part-time and transient workforce characterized by low salaries and high turnover (National Afterschool Association, 2006). Importantly, staff experience, wages, and staff-to-child ratios longitudinally influence elementary school children’s ASP experiences and social-emotional outcomes (Wade, 2015). In the absence of formal after-school guidelines, curricula, and standards, many frontline staff become responsible for planning routines and activities. The absence of rigid requirements highlights why ASP are a valuable tool and space for SEL and health promotion, while also demonstrating why classroom interventions—inherently designed to engage students in structured lessons—are often insufficient.

Altogether, distinguishing features of community-based ASP may limit the relevance, utility, or infusion of evidence-based recommendations that have been designed for and tested in schools. Two decades of partnerships on our team have revealed that after-school workforce support requires explicit consideration for differences across programs and fluctuations in staffing, enrollment, and resources, taking heed of challenges reported consistently in the after-school literature. Responding to the unique obstacles of ASP across multiple collaborators has influenced the content and methods by which we support ASP partners to mitigate risk, build resilience, and promote positive health trajectories for youth. Specifically, we (a) abandoned efforts to transport new and complex school-based behavioral interventions or SEL curriculum, in favor of creating and leveraging teachable moments inherent to recreational activities, and (b) focus support on three generalizable skill sets underlying risk and resilience pathways and common across evidence-based youth prevention (e.g., violence, suicide) programs (Boustani et al., 2015). These three skill sets include emotion regulation (e.g., awareness/insight, flexible thinking, mindfulness, relaxation), communication (e.g., verbal and nonverbal, assertive versus aggressive, code-switching, electronic), and problem-solving (e.g., identify the problem, consider feasibility, costs and outcomes of potential solutions). Discussions with after-school partners consistently have revealed high enthusiasm for explicitly targeting these skill sets, as they reflect what already are widely perceived as the natural, inherent benefits of sports and recreation.

In this paper, we offer first person accounts of work conducted over two decades to illustrate common challenges and proposed solutions that inform ongoing shifts in our broad approach to ASP workforce support. Collaborating ASP serve urban communities characterized by frequent violence, resource poverty, underemployment, food insecurity, and housing instability. They enroll youth across developmental stages (i.e., preschool through high school) and encompass many program goals (e.g., physical activity and recreation, SEL, academic achievement, music and arts education). We begin with a brief summary of our long-standing and previously described collaboration with the Chicago Park District (Frazier, Mehta, Atkins, Hur, & Rusch, 2013; Frazier et al., 2007) to acquaint readers with the origin of our work. This is followed by more detailed accounts of recent and ongoing partnerships in Miami with publicly funded, faith-based, and nonprofit ASP and efforts to strengthen their role, capacity, and contribution to youth and community resilience and wellness. Branches South Miami provides an example of individual site-level partnership and consultation. Miami Dade Parks Recreation and Open Spaces Department illustrates our work at the county-level with larger groups of frontline ASP staff who work across many sites. Children are Blessings represents an organizational-level approach to workforce support that extends beyond frontline staff to program managers and administrative leaders. In each first-person account, we offer a brief description of our collaboration and highlight challenges, solutions, and lessons that continue to inform our ongoing work. We conclude with recommendations for redefining sustainability to encourage ongoing partnerships and workforce support that remains flexible and responsive over time to the changing structures, priorities, strengths, and opportunities of collaborating ASP.

First Person Accounts

Chicago Park District

Just after the millennium, Frazier’s Chicago-based team conducted a mental health services research study for children with disruptive behavior disorders in under-resourced schools. The NCLB landscape inspired our increased focus on academic achievement and our reduced focus on socio-emotional learning. A school security guard escorted us to a local neighborhood park where many students completed homework and played sports after school. Discussion over many months with part-time recreation leaders, full-time physical instructors, and the park supervisor revealed that front-line staff, while compassionate and well-intentioned, had neither the training nor the resources to address children’s significant social and behavioral difficulties and culminated in an NIH grant to (a) examine the strengths and needs of organized community-based ASP; (b) adapt and deliver evidence-based interventions for instruction and behavior management via real-time consultation; and (c) examine benefits to children’s mental health (Frazier et al., 2007). Park collaborators named the Project NAFASI—Nurturing All Families through Afterschool Improvement—Kiswahili for opportunity.

In the absence of studies explicitly examining afterschool interventions, we borrowed from literature on contingency-based classroom management by modifying and implementing variations on evidence-informed recommendations. Workshops focused on minimizing and managing disruptive behaviors were followed by in vivo coaching instruction and real-time consultation around rules and routines. We introduced evidence-based tools by pairing children for Peer Assisted Learning (Fuchs, Fuchs, Mathes, & Simmons, 1997), communicating with families via Good News Notes (Metzler, Biglan, Rusby, & Sprague, 2001), and applying principles of behavior management and reinforcement via the Good Behavior Game (Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf, 1969) and Daily Report Card (Kelley & McCain, 1995). Findings revealed high staff satisfaction and encouraging but modest improvements in children’s adaptive functioning (Frazier et al., 2013). Independent observations not only revealed warm adult–youth relationships and consistent routines but also missed opportunities to explicitly target children’s social-emotional skills. Challenges associated with implementing and sustaining interventions once consultation ended (Lyon, Frazier, Mehta, Atkins, & Weisbach, 2011) hinted at salient differences between schools and ASP contexts that brought into question the relevance and utility of classroom-based strategies, and the need to engage with partners at multiple levels of organizational hierarchy, despite inherent intraorganizational transience. Altogether, findings informed our decision to reconceptualize workforce support—away from behavior management and toward youth development. Concurrently, we moved away from big and complex disruptive interventions and toward small and incremental improvements in daily routines, minimizing the difference between new and current practice and maximizing likelihood of adoption and impact (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001). Although we continue to offer workshops (didactics, demonstration, and practice with feedback) and on-site coaching (support and problem-solving), often by request of our partnering ASPs, we have simplified recommendations and sought ways to harness strengths indigenous to programs and staff.

Branches South Miami

Our Branches partnership began at a 2014 child mental health conference, where a program director asked our team to consult on disruptive behavior and SEL goals. Branches is a small non-profit, faith-based neighborhood organization offering four local ASP providing homework assistance, recreation, and structured group reading activities to low income youth of color (i.e., 59% African American, 23% Haitian, 8% Hispanic). Most full-time staff are college educated, experienced childcare workers who receive regular training, and several represent AmeriCorps, resulting in substantial annual turnover. Funding comes from local foundation grants as well as corporate and personal donations. Programs are delivered in local churches and are occasionally displaced for special events (e.g., holiday services, funerals). Eighteen months of structured meetings with frontline staff and the program director at one site, alongside informal observations and interactions, revealed areas of both strength (e.g., organizational commitment to promoting positive youth and staff development, eager workforce) and opportunity (e.g., high staff-to-youth ratio, wide age range).

Challenges.

As a faith-based program, Branches relied on church multipurpose rooms, which meant limited space and storage, shared resources, inconsistent access, and program disruptions due to church activities and special events. Variability in youth attendance also disrupted routines, relationships, and instruction, reflecting challenges associated with transportation to/from school, competing afterschool activities and responsibilities, and fluctuations in perceived safety corresponding to spikes in neighborhood violence. Inconsistent attendance contributed to shifting routines, weak rapport, and disengagement, making it more difficult to prevent and manage conflicts among youth as well as reducing opportunities to interact with parents. Furthermore, youth were familiar with peers from school or extended family, resulting in risk for interpersonal problems to materialize into aggression and conflict after school. Altogether, constraints on space, time, and resources, high and fluctuating staff-to-child ratio, and heterogeneity in children’s ages, grades (i.e., K–4th), and skills drove our universal application of a peer-assisted learning approach (Fuchs et al., 1997) to build social competence.

Recommendations.

We developed and piloted a peer-assisted social learning (PASL; Helseth & Frazier, 2018) model to promote peer-facilitated problem-solving during recreational activities. Children were paired for activities, which kept them engaged and freed staff to reinforce on-task behavior, cooperation, rule-following, and social problem-solving. Staff received a 2-hour initial training (didactic, modeling, and role-play components), followed by brief weekly meetings during which PASL data, observed adherence, and staff feedback were used to iteratively refine activities, delivery, and tools for workforce support (National Research Council, 2002). Early PASL activities were modeled and led by the research team and co-facilitated by Branches staff, who ultimately implemented PASL activities independently, with ongoing consultation and support from academic partners as needed. Cue cards reminded children of the five-step problem-solving sequence and PASL activity rules (e.g., share materials, help your partner) for which frontline staff awarded points for compliance. Pilot implementation (3 months, 5 staff, 30 children, 21 activities) revealed strong evidence for feasibility (i.e., attendance, participation, and enthusiasm), fidelity (i.e., adherence and competence), and staff confidence in their ability to lead future activities, hinting at the potential for sustainability (Helseth & Frazier, 2018).

Lesson: Leverage Without Over-Extending Existing Resources.

Due to limited and fluctuating resources, and with an eye toward sustainability, we prioritized content that relies on readily available equipment and materials; is flexible with space, time, and resources needed for success; minimizes burden on staff; and maximizes opportunities for engagement and learning for children in attendance each day. In particular, we capitalized on mixed-age peer groups by extending peer-assisted learning (Fuchs et al., 1997) to recreation (Helseth & Frazier, 2018). As well, we replaced complex reward systems that require planning, preparation, and reliable follow-through with easy-to-implement, low-cost, high-reach tools that rely on evidence-based kernels of influence (see Embry & Biglan, 2008), such as shout-out walls (encouraging positive staff and peer reporting of prosocial behaviors via ‘catch ‘em being good’ and Tootling; Fantuzzo, Rohrbeck, Hightower, & Work, 1991) and good news notes (sent home to parents to reinforce subtle and salient examples of rule following and SEL skills).

Miami Dade Parks Recreation and Open Spaces (MDPROS) Department

Our team has been collaborating with frontline staff, district managers, and division directors from MDPROS and several other county partners (e.g., Miami Dade County Public Schools and Juvenile Services Department) since 2015, toward the development and study of a county-funded after-school initiative called Fit2Lead. Fit2Lead is a free daily ASP, delivered annually in ~10 parks across the county, with academic support and life skills-infused sports/recreation for youth ages 12–14 (enrolled 2016– 2017: n = 13 parks, 400 youth, 64% male, 70% Non-Hispanic Black, 20% Hispanic/Latinx, 28% families report household income between $5,000 and $20,000). Inspired by the Mayor’s Roundtable on Youth Violence, Fit2Lead was designed to reduce youth violence and victimization in Miami’s most vulnerable and turbulent communities. The program was designed explicitly to leverage teachable moments of sports and physically active recreation to introduce and practice core life skills. The original 55 Recreation Leaders hired in 2016 were 51% non-Hispanic Black, 36% Hispanic/Latinx, 53% male, and 73% college graduates; of these, close to only one-fourth remain in front-line roles, despite a competitive pay scale. Park staff collect individual (academic, mental health, biometric) and population health data from youth and families at the start and end of each school year.

Challenges.

Frontline park staff report diverse educational backgrounds, previous experiences, and professional goals corresponding to differences in life and career stage, motivation, time and availability, job and organizational commitment, individual resources, and comfort with technology—all known to influence adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices (Damschroder et al., 2009). Specifically, data from two cohorts of Fit2Lead park staff reveal multidisciplinary educational backgrounds (e.g., psychology, education, public health, recreation science, physical education) and professional experiences (e.g., teachers, coaches, counselors), and a nearly inverse relationship between formal schooling and youth care work. We also have discovered that “floaters” work in ASP temporarily (e.g., part-time job helps pay for education) on their way to full-time careers, while “lifers” are seasoned (e.g., they “grew up” in ASP) and seeking part-time youth work to give back to their communities and share their local knowledge and experience. Theoretically, attitudes, knowledge, and skills influence staff interest in and interpretation of training material, and in turn what they learn, retain, and transfer to their work (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Baldwin & Wilder, 2014), though packaged curricula or trainings may minimize or fail to address these individual differences. Moreover, packaged curricula typically require considerable up-front time and investment in each staff member, in the form of training, instruction, and support, that can be lost in the face of high turnover. Relatedly, new staff replacing those who have left are often asked to “jump in” mid-stream without receiving the extensive training opportunities previously offered. New staff may find it challenging to align with more seasoned team members who were trained to implement complex curriculum. Similarly, workforce variability increases under conditions of high turnover and complicates traditional one-and-done workshops—for new and seasoned staff—that tend not to differentiate instruction or follow up with ongoing support.

Recommendations.

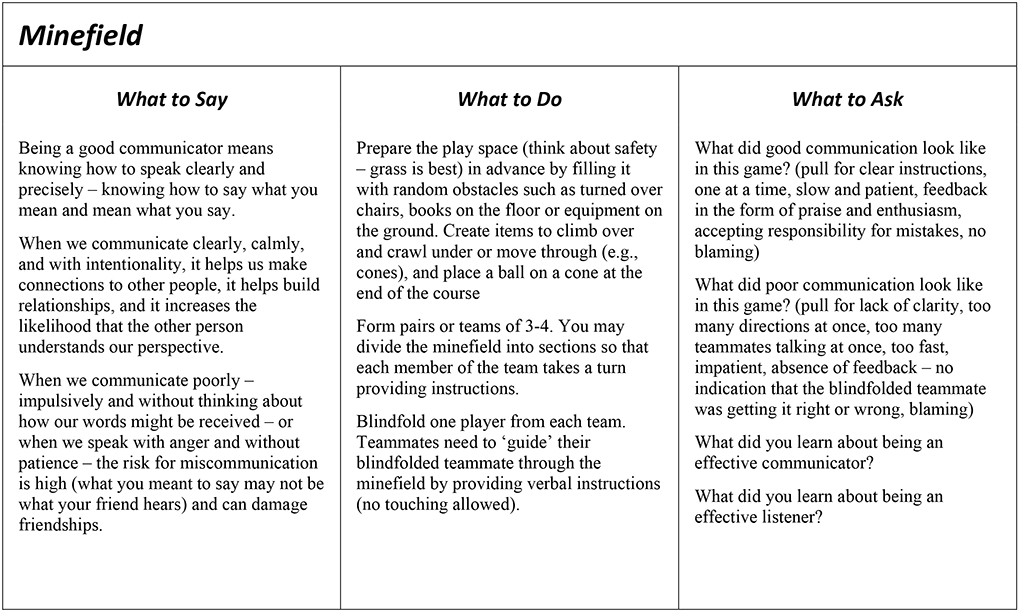

We carried forward our broad goals to simplify and align recommendations with natural ASP goals and routines by introducing Pre- and Post-Game Huddles. Before the start of an activity, Pre-Game Huddles are a time to review and operationalize standing park rules (i.e., follow instructions; respect for self, others, and space; be where you are supposed to be; do what you are supposed to be doing); introduce activity goals and instructions (demonstrate skills; check for understanding); and practice a life skills drill. Skills drills enable staff to highlight a discrete skill component (e.g., nonverbal communication, emotion awareness) with a scripted didactic introduction, game designed to expose what is difficult about the skill, and discussion guided by question prompts (see Fig. 1 for sample drill called Minefield; others available upon request). Following activities, Post-Game Huddles include staff and peer shout-outs for engaged participation or life skills (i.e., Tootling; Fantuzzo et al., 1991), reflective conversations regarding good and bad examples of life skills during the game (e.g., “Tell me about a good example you observed of clear and direct communication?” or “Let’s consider why it seemed difficult to work effectively as a team”) and generalization of skills to other relationships and settings (e.g., “Why can it be difficult to remain calm when you feel angry at school?”), ending with a brief relaxation (i.e., deep breathing or visualization).

Figure 1.

Life Skills Drill: Minefield. Content formatted for publication – for original versions, see http://nafasipartners.fiu.edu/activities/

Hence, Pre- and Post-Game Huddles are brief (5 or 10 minutes), mirror traditional pregame (assign positions and strategize) and postgame (reflect on effort and outcomes; strengths and areas for improvement; generalization of skills after the game) coaching tools; apply empirically based strategies to maximize engagement (e.g., clear rules and instructions; positive reinforcement); and rely on repetition (practice with feedback) to encourage skills building (for staff and youth). Rather than segregating life skills practice to the traditional format of many prevention programs, Post-Game Huddles leverage teachable moments that naturally occur during sports and recreation. Despite our expectation that Huddles would infuse easily into Fit2Lead routines and minimize need for extensive training or technical support, staff report inconsistent use and challenges related to time, self-efficacy, and youth engagement. In response, we have begun to use limited in-person training for low-stakes practice and problem-solving and expanded the platforms by which we disseminate and store didactic information, resources, and other evidence-based workforce support tools.

Specifically, we have embraced a three-tiered approach to workforce support that includes a virtual platform, in-person trainings, and park visits for ongoing implementation support and problem-solving. Tier 1 Website: Our MDPROS collaboration inspired us to move didactic material online (http://nafasipartners.fiu.edu), responding to direct requests from frontline staff for online resources, and enabling didactic support to begin at any point during the year whenever new staff are hired. The website presents core content in a lesson-by-lesson format, accompanied by slides and materials for download, instructions for life skills drills, and video exemplars of frontline staff demonstrating Pre- and Post-Game Huddles. Moving didactic content online has helped us to reserve in-person trainings for differentiated instruction and active practice with feedback. Tier 2 Workshops: Hence, our second tier of support includes monthly MDPROS trainings during which we describe, model, and practice Pre- and Post-Game Huddles; introduce and practice life skills drills; or provide information and field questions about youth mental health (e.g., bullying, mental health first aid, risk assessments). Seasoned staff often demonstrate skills or co-facilitate, and time is also reserved for peer circles (staff exchange ideas, share information, or provide feedback on tools and training).

Tier 3 coaching. Finally, for individual parks or providers that are struggling (e.g., have youth with the most challenging difficulties; bring the least formal training or experience), we provide real-time, on-site coaching by graduate students. Coaches model skills, co-facilitate activities, and problem-solve to promote youth and family engagement, support academic enrichment, and infuse recreation with explicit opportunities to practice and generalize core life skills. For providers who find site visits more disruptive than supportive, we offer consultation as needed, relying on phone calls, text, and email to answer questions and problem solve. However, given that 10 parks offer Fit2Lead across the county, serving diverse communities with equally diverse strengths and needs, regular coaching at every site is untenable. Thus, we also leverage expertise of on-site staff—leaning both on those with more experience and mastery of SEL skills, and on those whose backgrounds, training, and influence lend themselves to coaching and support roles. Feedback on the three tiers of workforce support mirrors reports in the literature regarding the value of training that integrates theoretical principles with active practice and opportunities for staff to exchange ideas and information (Baldwin & Wilder, 2014).

Lesson: Harness indigenous skills and strengths of program staff.

We have come to appreciate that diverse educational and professional backgrounds represent an asset—not a limitation—of transient frontline recreators. Drawing on the literature for professional learning communities (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008), we are creating in-person and online opportunities for providers to harness, share, and shape local knowledge; build organizational social capital; and contribute to the development and distribution—both via systemic dissemination and natural diffusion—of practice-based and evidence-informed recommendations. In fact, the predictable transience and turnover of ASP staff accelerated our efforts to build internal capacity via train-the-trainer approaches and teaching-and-learning sites (i.e., “lab parks”) that rely on key opinion leaders and internal champions to support newer staff. Compared to in-person training and support provided by outside stakeholders or research partners, endorsement and training offered by influential and respected colleagues who are “structurally similar” (i.e., same role and function) predict increased adoption of evidence-based practices (Burt, 1999). Hence, Fit2Lead staff with mental health experience contribute to an abbreviated Mental Health First Aid training (Kitchener & Jorm, 2004); those with teaching experience introduce activities for academic enrichment; and physical education teachers and coaches facilitate the demonstrations of Pre- and Post-Game Huddles and physical activities strategically designed to practice SEL concepts.

Operating at the nexus of local opinion leader (Valente & Davis, 1999) and task-shifting (Patel, 2009) literatures, we have come closer to identifying the point at which we stretch staff comfort and expertise enough for them to embrace opportunities for leadership roles and integrate evidence-based kernels into training and support for others, but not so far that they become uncomfortable, feel overextended, or lose enthusiasm for their elevated role. Asking staff to go too far beyond their comfort zone or expertise yields diminishing returns but engaging frontline staff who bridge the gap between scholarly (i.e., evidence-based practice) and local (i.e., practice-based evidence) knowledge has enabled us to approximate this sweet spot.

Across literatures and industries, turnover is most often perceived as an obstacle; that is, an organization invests time and resources in training staff and then staff leave, taking with them what they have learned, thus minimizing return on investment for the organization (Woltmann et al., 2008). Turnover is predictable and inherent to the after-school workforce—a function of the part-time, low-compensation nature of the position—and thus by necessity, we have come to appreciate what transience offers rather than what it impedes. First, transience means a revolving door of new staff not yet experiencing high depersonalization to their job that may accompany stress and burnout (Dunford, Shipp, Boss, Angermeier, & Boss, 2012; Jackson & Schuler, 1983); thus, they may be more open to recommendations and support. Second, each new staff member brings unique perspectives, experiences, and expertise; to the extent that we are successful in documenting and preserving what they contribute (e.g., via local knowledge sharing platforms and group discussions), organizational social capital continues to grow and expand, allowing some of their knowledge and expertise to remain behind even when they leave the organization. As mentioned above, Fit2Lead’s turnover is predictable among staff who are concurrently attending school or seeking full-time employment, but less likely among a smaller group of enthusiastic seasoned staff who are well positioned to serve as role models and mentors for new and junior recreation colleagues.

Children are Blessings (Bless, pseudonym)

Bless is a local nonprofit neighborhood organization serving one predominantly black and disenfranchised community facing concentrated poverty and high rates of crime. Bless initiatives include health and wellness programming (e.g., nutrition education, fresh food coops), a community space for neighborhood events that connect families to local resources, and after-school and summer programs for youth in preschool to high school. Since our partnership began in 2016, we have been collaborating with frontline staff, program managers, and organizational leadership, and providing support for preschool, elementary, and middle school programs. All three programs are housed within the same public school, and are staffed by a combination of teachers (certified educators employed at the school during the day) and assistants (part-time staff members with varying childcare, education, recreation, and mental health training). Leaders in particular are responsible for communicating with parents and teachers, monitoring academic progress, and engaging students in program activities.

Challenges.

Challenges at Bless exemplify the instability of ASP and the impact of a constantly shifting organizational landscape on the quality of programming. Daily operations have been impacted by regular shifts in frontline staff members’ hours of employment and the removal of AmeriCorps staff from the Bless workforce. In the 2 years since our partnership began, Bless has had three CEOs and two program directors. Additionally, the grants manager overseeing ASP funding and budgeting as well as two ASP team leads have left the organization with no replacement. ASP supervisors need a combination of expertise that stretches beyond even what may be required of administrators in schools or early childhood programs (Baldwin & Wilder, 2014); yet, like their frontline colleagues, they have limited opportunities for formal training or certification, which may help to explain frequent turnover, despite higher compensation and advancement.

Recommendations.

Our original workforce support goals—decided in partnership with Bless leadership—included didactic instruction, discussion, and in vivo observation and consultation around student engagement and provision of the core SEL skills. Planned activities included three monthly workshops and weekly site visits. Frontline staff feedback substantiated our own observations, both highlighting structural and logistical challenges to providing high quality, engaging academic and SEL content, and pointing to a need for organizational intervention components. Quantitative surveys helped to identify frontline key opinion leaders, and we assembled small workgroups of influential teachers and assistants. In the absence of consistent representation from leadership, however, meetings served to reveal but not resolve ASP challenges such as lack of materials, insufficient planning time, and unpredictable daily schedules. As a result, we extended our efforts upward to include the site supervisor and program directors. Informed by principles underlying organizational and leadership interventions (e.g., Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Hurlburt, 2015; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005), we suggested a steering committee form to offer frontline staff a “seat at the table” for programmatic decision-making. Concurrently, we continued to provide real-time consultation to frontline staff on the use of student engagement strategies and SEL instruction. In preparation for the steering committee, we administered questionnaires to frontline staff examining burnout and the perceived control, resources, and demands of their work. While some quantitative data supported qualitative feedback (e.g., 68.8% reported feeling emotionally drained at work, only 12.5% reported feeling able to deal with the pressures of their jobs well, 43.7% reported having little control over availability of supplies), other data contradicted previous concerns (e.g., 81.2% reported feeling they had the necessary access to supervisor support, only 31.3% reported difficulties completing their work due to insufficient staffing). Further probing into these discrepancies revealed that staff members were uncomfortable providing critical feedback, unsure how to do so, and had low confidence that their honesty would result in change (i.e., providing honest feedback was high risk, low benefit). Steering committee meetings were delayed due to aforementioned shifts in leadership, leading us once again to revisit our goals and approach to workforce support. In particular, Bless offers a salient example of organizational intervention and the parallel process of ASP consultation. While we continue to encourage frontline staff to prioritize SEL instruction to youth via natural teachable moments, we also encourage them to explicitly practice socio-emotional skills, for instance by recognizing program strengths and clearly defining problems, generating creative and resourceful solutions, communicating assertively and directly with program managers, and regulating frustration and response to stress. At the same time, we are working directly with program managers and operations supervisors to master and model the same skills, toward the overall goal of improving organizational effectiveness, building capacity for reflective practice, and promoting salience of SEL components at all levels of workforce to promote self-efficacy and mitigate stress and burnout.

Lesson: Engage in parallel process of SEL support.

As we gained more insight about structural and organizational barriers to evidence-based practice implementation, we came to rely on our own use and modeling of SEL skills—emotion regulation, communication, and problem-solving—with staff across all levels of Bless. We have since become more explicit in our use of a parallel process to overcome barriers to change. In a particularly salient example, teachers and assistants expressed concerns about their curriculum (insufficient materials, developmental appropriateness) that interfered with engaging students and elevated their own frustration. Upon hearing their concerns, we utilized their frustration as a teachable moment to remind frontline staff about shared organizational goals (i.e., healthy youth trajectories) and to model and practice SEL skills—Emotion Regulation: we utilized cognitive restructuring to focus on program strengths and reconceptualize challenges as a result of limited resources rather than disengaged leadership; Communication: we explicitly considered who (one or several staff), when (private vs. public meeting; before, during, or after programming), and where (office vs. classroom, with or without students present) staff could communicate concerns directly and respectfully to their site supervisor, with particular attention to their purpose (i.e., to express frustration or offer suggestions), tone (e.g., angry or sympathetic), and expectations for change (optimistic, realistic, or pessimistic about timeline and substance); and Problem Solving: we encouraged creativity and resourcefulness, generating ideas for providing high quality programming in the interim (e.g., modifying curriculum; substitute materials) and systematically considering the feasibility, resources, advantages, and opportunities of each. Concurrently, we engaged leadership in related conversations that similarly leveraged SEL skills to reframe or regulate their own frustrations (e.g., regarding complaints from staff not adhering to curriculum), communicate with frontline staff about program and resource limitations, and invite team problem-solving to find viable solutions. Throughout this parallel process, we rely on a team mantra: Less is MORE. More is an acronym for Model, Observe, Reinforce, and Encourage and it refers to the application of SEL skills at all levels of workforce support, both internal and external. We hope that our own modeling and consultation on their use with frontline staff, program managers, and organizational directors increase their salience and the likelihood that they will become routinized in interactions with one another and with youth.

Mental Health Kernels Influence ASP Workforce Support

Altogether, lessons learned from our diverse partnerships point to the import of evidence-based mental health kernels of influence to ASP partnerships and workforce support. In this section, we have synthesized this learning into four applications: Thoughts–Feelings–Behavior Triangle; Daily Mood Monitoring; Intensive Support, and Measurement Feedback.

Thoughts-Feelings-Behavior Triangle

We apply fundamental theories such as the thoughts–feelings–behavior triangle (Beck, 1967) to reduce staff frustration about the imbalance of job demands and resources; bring into focus the motivational aspects of ASP work; and create space for more compassionate staff and student interactions. We start by employing the triangle to support our own efforts. For instance, we have found that some providers interact with less warmth, enthusiasm, and effectiveness with children exhibiting the most challenging behaviors, and often their openness and receptivity to our recommendations and support are low. Although it would be easy to interpret harsh interactions and disinterest as resistance, we instead consider that what we bring may not resonate in the context of significant personal and job-related stress arising from the high stakes demands of acting as teachers, coaches, counselors, and social workers. In turn, we encourage staff to rely on similar cognitive restructuring (e.g., flexible thinking, perspective taking) to reconsider children’s disruptive behavior as less defiant but rather a manifestation of acute and chronic adversities for which they are at increased risk (e.g., exposure to violence in the community or at home, food insecurity, housing instability; SAMHSA, 2014). Hence, the thoughts–feelings–behavior triangle enables us to assist frontline staff and program managers at every level to avoid judgment about one another’s work commitment or quality, reframe behaviors in the context of individual skill and effort, minimize criticism and frustration, and promote reflection, insight, communication, and problem-solving.

Daily Mood Monitoring

We apply the principles of daily mood self-monitoring and ecological momentary assessment (aan het Rot, Hogenelst, & Schoevers, 2012) by encouraging ASP staff to quickly and unobtrusively assess and respond to indicators of emotional distress at the start of each afternoon. Specifically, we suggest taking attendance by way of Mood Cups—youth privately disclose their mood by placing a popsicle stick with their name in a labeled cup (e.g., happy, sad, angry, vibin’, chillin’, shook) that corresponds to their current mood (related is a Mood Wheel, for which youth attach clothespins with their names to a slice of the wheel that matches their mood). Kids who disclose distress (e.g., sad, scared, angry, shook) are at risk for exhibiting more disengaged or disruptive behaviors; thus, we recommend staff check in privately for a few minutes via a four-step sequence: (a) express compassion (“I’m sorry to hear your afternoon isn’t starting off well, thank you for letting us know”); (b) leverage the teachable moment related to emotional awareness, insight, and communication (e.g., “Are you feeling more angry or more frustrated? “How angry do you feel?”); (c) model and practice a quick calm (4–2–8 breaths); and (d) engage them in planned activities (behavior activation) rather than letting youth sit out (risking rumination). We discourage digging too deeply into the trigger for their negative mood, and instead encourage them to focus on engagement. Daily documentation further enables staff to systematically identify children whose chronic negative mood may warrant a referral for services, leveraging the additional opportunity for ASP to serve as a gateway to mental health care for youth suffering clinically elevated symptoms.

Intensive Support

Our partners are profoundly impacted, directly and indirectly, by trauma, violence, and disenfranchisement present in the communities they serve. For instance, Bless lost three youth last year, two of them to gun violence, inspiring discussions of community resilience and, in particular, our role in supporting efforts to grieve and heal. Frontline staff asked our team to provide psychosocial support, and while historically we have not directly provided mental health services, we offered immediate support by engaging in conversations around loss, trauma, and community violence. Indeed, frontline afterschool providers routinely report feeling unprepared for these inevitable conversations with youth and families and look to us for guidance. Borrowing from a growing literature on emergent life events in therapeutic interactions (Guan, Boustani, & Chorpita, 2018), we interpret acute stressors not as distractions that impede learning, but as opportunities for compassion and life skills practice—for staff and for youth—such as emotional awareness, mindfulness, and communication (e.g., journaling) within the very real context of grief and anger.

As an additional example, Fit2Lead partners requested abbreviated Mental Health First Aid (Kitchener & Jorm, 2004) training and resources after an enrolled teen revealed intention and plans for self-harm. In response, we provided immediate support (e.g., coaching frontline staff to create a safety plan, identify social supports, communicate with primary caregivers, when to call 911) and a comprehensive risk management plan with a simple one-page flowchart as reference for future need. The resulting suicide risk protocol has been added to staff training handbooks. During in-person training, we hear often about the frequency with which youth disclose personal stressors, exposure to violence, and risk-taking, and we offer resources and recommendations (e.g., Do’s and Don’ts of Active Listening) that help staff to avoid overstepping their role or training, but equip them to listen with compassion and without judgment during these high-stakes interactions.

Measurement Feedback

Efforts to minimize burden (for frontline staff whose expectations and responsibilities already exceed available time and resources) and maximize learning have led us to rely increasingly on implementation by-product data (i.e., functional residue, Hagermoser & Melissa, 2014; e.g., PASL cue cards, Mood Cups, shout out walls) to inform workforce support. Recently we have extended these efforts to training, where we are using Kahoot! questions (https://kahoot.com/) to assess pretraining knowledge and attitudes and post-training intentions and anticipated challenges. Rapid response data collection in this format has enabled us to ascertain and summarize the variability in staff experience and expectations for training, and tailor content, examples, and discussion in ways that stretch— but not overextend—participants’ mastery of content. Altogether, immediate and continuous by-product data enable us to identify what does and does not integrate easily and effectively (Garland, Bickman, & Chorpita, 2010), and facilitates data-informed workforce support, feedback, and problem-solving. Subsequently, we can revise training, tools, and content accordingly and often, reflecting the spirit of measurement feedback systems and partnership.

Lessons Learned

Our team embraces several lessons informed by our collaborations and a multidisciplinary empirical literature. These lessons ensure an approach to workforce support that is not about getting things adopted, but rather about getting people supported, as the name itself suggests. We recognize, however, that partnerships vary as broadly as the diverse communities and organizations they serve; thus, generalizable recommendations must be fluid and flexible. With consideration for our experiences, and the literature that guides us, we propose a series of questions that we hope may guide others to incorporate our “lessons learned” into their own community-engaged collaborations and research.

What Are the Goals and Priorities of Our Community Partner?

Although we largely abandoned tools designed and packaged for schools, lessons and kernels extracted from school mental health research continue to influence our work. While we recognize that after-school settings are inherently meaningful for children’s social and emotional development, we are careful not to “rebrand” ASP as a mental health service by hijacking time for manualized interventions that extend beyond the spirit and mission of our collaborators. We are reminded of the following insight from the school mental health literature—“Specifically, we suggest that in these high-poverty communities, the goal should not be to make mental health services a primary goal of schools, but rather to make children’s schooling a primary goal of mental health services” (Atkins, Frazier, et al. 2006, p. 156). Similarly, instead of working to replace ASP curriculum with mental health content, we instead seek to leverage the rich teachable moments naturally present in ASP spaces to maximize the benefits for staff and youth of healthy relationships and routines that encourage reflection related to critical and generalizable life skills.

What Inherent Strengths and Resources are Available?

In keeping with our goal to enrich existing programming and align with ASP missions, we operate as closely as possible within the means of our partners. This includes identifying native strengths and resources to avoid placing unreasonable demands on staff that—in the absence of adequate time, training, or support—overextend competencies, strain relationships or drain resources, and contribute to stress and burnout. We are influenced by the following assumption underlying Multi-Systemic Therapy, “Clinicians are hardworking, competent professionals with unique strengths and experiences, yet, to treat youth with serious clinical problems effectively, they will benefit from ongoing support” (Schoenwald, Mehta, Frazier, & Shernoff, 2013, p. 49). This principle bears relevance to ASP staff whose talents and efforts often go unseen, dismissed, or underappreciated. Significant job stress among frontline staff and program managers alike reflects an afterschool culture (local and national) characterized by increasing responsibility for youth development but diminishing investment, unpredictable conditions, and fluctuating resources. Adhering to a set of principles like those of Multi-Systemic Therapy, we value the expertise, commitment, and good intentions of ASP staff at all levels; we operate with the understanding that everyone is doing their best; and we are mindful that our presence and recommendations may involve risk if not adequately or comprehensively informed by local voices (youth, staff, families) or to the extent that they add burden, absorb resources, or create competing demands. We have altogether abandoned the idea of resistance, which inherently contradicts our priority on cultural mindfulness, and thus arrived at perhaps our greatest lesson learned, that of humility.

How Can We Align Mental Health Content to the Goals and Strengths of Our Community Partner to Encourage Feasible, Incremental, and Sustainable Change?

“The literature on diffusion of innovation suggests that the extent to which the innovation is perceived as similar to or different from prevailing practice will influence adoption of the practice.” (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001, p. 1194). Dissemination science highlights the importance of presenting mental health content in “manageable bites” which fit into planned programming and can be implemented effectively with existing knowledge and resources. We have learned to recommend small adjustments to current practice instead of big and disruptive interventions. Incremental changes that align with organizational priorities, integrate seamlessly into natural routines, and require minimal resources have the greatest chance of organizational survival. Relatedly, we neither discourage nor begrudgingly accept modifications to the structure or operation of proposed recommendations, but rather explicitly welcome and encourage them, inspired by historic and multidisciplinary evidence (e.g., literature, biology, physiology) that adaptations also improve the likelihood of endurance. Indeed, adaptations require reflection, commitment, and insight, and they can inspire creativity, enthusiasm, and ownership that ultimately lead to survival.

We frequently revisit these questions even during longstanding collaborations in order to both check our progress and guide future efforts. We encourage interested readers to apply them to their own work toward identifying areas in which workforce support efforts: (a) may not align with partner or community goals; (b) can capitalize on existing strengths and resources; (c) have mistakenly interpreted barriers to implementation as resistance to change; and (d) can reveal ways in which mental health content might be further dismantled into more digestible units for more feasible, but still meaningful, change. Joint problem-solving and shared decision-making with frontline staff and program leaders may reveal indigenous and diverse strengths and resources to absorb or adjust evidence-based recommendations; and where adoption of a new strategy stalls, we recommend simplifying and synchronizing content within the existing ASP ecosystem.

Conclusions

Historically, after-school research has focused on behavior management and SEL, relying on traditional evidence-based tools designed for and tested in schools. Workforce and resource limitations interfere with program readiness to adopt or implement complex recommendations, contributing to variable adherence and outcomes. Pervasive vulnerabilities and the extraordinary resilience of our ASP partners, particularly in urban communities characterized by poverty and violence, highlight unique strengths and opportunities to promote youth development. In-person and online formats for workforce support and resource sharing enable us to abandon one-size-fits-all approaches and reach a diverse staff characterized by individual differences in knowledge and experience. By leveraging natural routines and teachable moments inherent to recreation, and the diverse and multidisciplinary skills staff traditionally bring to their positions, we can address more intensive needs, without concern that skill development or support has temporarily stalled. The result is an iteratively evolving multitiered approach to workforce support, reflecting our diminished interest in the sustainability of particular evidence-based products and greater attention to building an evidence-informed workforce. Implementation science once defined sustainability as the integration and maintained implementation of a novel practice into routine operations (Steckler & Goodman, 1989) after the withdrawal of external support. Researchers have since relaxed strict expectations for fidelity and argued for a more dynamic conceptualization that views sustainability not as an endpoint but an ongoing process (see Dynamic Sustainability Framework; Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013), recognizing that capacity building and ongoing collaboration are not mutually exclusive. We have adopted a similar logic: systems have a natural tendency toward entropy and require ongoing infusions of energy to prevent gradual degradation of their quality. Sustained practice, therefore, should not be the end of implementation but an ongoing, low-intensity process, allowing collaborative partners to integrate new information and respond to changes in context. Accordingly, our model reflects ongoing and sustained commitment to ASP partners and professional development via flexible and responsive mechanisms for learning, retention, transfer, and workforce support. Viewed through a task-shifting lens (Patel, 2009), we encourage ASP to embrace positive youth development and SEL as program norms, intentionally and explicitly embed these values into the scope of afterschool work, and integrate them into the role and function of frontline staff, program managers, and organizational directors. Ultimately, our approach is best summarized as a parallel process by which we (a) rely on data-informed decisions for staff training (e.g., Kahoot!) and youth support (e.g., Mood Cups); (b) apply psychological concepts to interactions with staff (e.g., thoughts–feelings–behavior triangle) and encourage staff to apply related concepts in their interactions with kids (e.g., Pre- and Post-Game Huddles); and (c) offer support around emergent life events (e.g., community violence and grief) while providing tools for staff to do the same (e.g., Mental Health First Aid). Across our lessons learned, we have seen the importance of aligning with organizational goals, accommodating fluctuating priorities and resources, and continuously listening to our community partners to work from a place of strength and opportunity. The result is a multitiered and multifaceted approach to workforce support that allows us to harness, organize, and amplify frontline talent and expertise, and to embrace the very same SEL skills we seek to instill in youth and staff at all levels of after-school programming.

Highlights.

Resource and workforce challenges impede adoption of evidence-based practice in after-school programs.

Academic–community partnerships inform recommendations that align with individual program goals.

We describe a three-tiered approach to workforce support with online, workshop, and on-site components.

Content prioritizes mental health kernels: emotion regulation, communication, and problem-solving.

Support leverages teachable moments inherent to recreation and harnesses staff talent and expertise.

Acknowledgements.

The research described was partially funded by NIMH (R34MH070637 and R01MH081049 awarded to the first author; F31MH106252 awarded to the fifth author), NICHD (F31HD093348 awarded to the second author), Florida International University (Presidential Fellowship awarded to the third author; Dissertation Year Fellowship awarded to the fourth author), and Miami-Dade County.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval. All study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of external and university institutional review boards.

Informed Consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participating youth, parents, and after-school staff included in the studies.

References

- aan het Rot M, Hogenelst K, & Schoevers RA (2012). Mood disorders in everyday life: A systematic review of experience sampling and ecological momentary assessment studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 510–523. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, & Hurlburt MS (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implementation Science, 10(11). 10.1186/s13012-014-0192-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afterschool Alliance (2006). Afterschool funding forum I: A Q&A with outside experts on sustainability. Available from: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/fundingForum1.cfm [last accessed April 26 2018].

- Afterschool Alliance (2014). America after 3 pm: Afterschool programs in demand. Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/AA3PM/ [last accessed April 8, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Frazier SL, Birman D, Adil JA, Jackson M, Graczyk P, Talbott E, Farmer D, Bell C, & McKay M (2006). School-based mental health services for children living in high poverty urban communities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin TT, & Ford JK (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology, 41(1), 63–105. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CK, & Wilder Q (2014). Inside quality: Examination of quality improvement processes in afterschool youth programs. Child & Youth Services, 35(2), 152–168. 10.1080/0145935X.2014.924346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrish HH, Saunders M, & Wolf MM (1969). Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2(2), 119–124. 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1967). Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York, NY: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Boustani MM, Frazier SL, Becker KD, Bechor M, Dinizulu SM, Hedemann ER, … Pasalich DS (2015). Common elements of adolescent prevention programs: Minimizing burden while maximizing reach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(2), 209–219. 10.1007/s10488-014-0541-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS (1999). The social capital of opinion leaders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 566, 37–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1048841 [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, & Stange KC (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 117 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffett A, Johnson J, Farkas S, Kung S, & Ott A (2004). All work and no play? Listening to what kids and parents really want from out-of-school time. New York, NY: Public Agenda. [Google Scholar]

- Dunford BB, Shipp AJ, Boss RW, Angermeier I, & Boss AD (2012). Is burnout static or dynamic? A career transition perspective of employee burnout trajectories. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 637–650. 10.1037/a0027060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD, & Biglan A (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 75–113. 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, Rohrbeck CA, Hightower AD, & Work WC (1991). Teachers’ use and children’s preferences of rewards in elementary school. Psychology in the Schools, 28(2), 175–181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SL, Cappella E, & Atkins MS (2007). Linking mental health and after school systems for children in urban poverty. Preventing problems, promoting possibilities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34, 389–399. 10.1007/s10488-007-0118-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SL, Mehta TG, Atkins MS, Hur K, & Rusch D (2013). Not just a walk in the park: Efficacy to effectiveness for after school programs in communities of concentrated urban poverty. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40, 406–413. 10.1007/s10488-012-0432-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Mathes PG, & Simmons DC (1997). Peer-assisted learning strategies: Making classrooms more responsive to diversity. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 174–206. 10.3102/00028312034001174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, & Schoenwald SK (2005). The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research, 7(4), 243–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Bickman L, & Chorpita BF (2010). Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(1–2), 15–26. 10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Boustani MM, & Chorpita BF (2018). “Teaching moments” in psychotherapy: Addressing emergent life events using strategies from a modular evidence-based treatment. Behavior Therapy, 50, 101–114. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagermoser LM, & Melissa S (2014). Increasing the rigor of procedural fidelity assessment: An empirical comparison of direct observation and permanent product review. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(1), 60–88. [Google Scholar]

- Helseth SA, & Frazier SL (2018). Peer-Assisted Social Learning for diverse and low-income youth: Infusing mental health promotion into urban after school programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(2), 286–301. 10.1007/s10488-017-0823-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, & Schuler RS (1983). Preventing employee burnout. Personnel, 60(2), 58–68. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10261205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, & McCain AP (1995). Promoting academic performance in inattentive children. The relative efficacy of school–home notes with and without response cost. Behavior Modification, 19, 357–375. 10.1177/01454455950193006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener BA, & Jorm AF (2004). Mental health first aid training in a workplace setting: A randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN13249129]. BMC Psychiatry, 4, 1–8. 10.1186/1471-244X-4-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon A, Frazier SL, Mehta TG, Atkins MS, & Weisbach J (2011). Easier said than done: Intervention sustainability in an urban after-school program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 504–517. 10.1007/s10488-011-0339-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler CW, Biglan A, Rusby J, & Sprague JR (2001). Evaluation of a comprehensive behavior management program to improve school-wide positive behavior support. Education and treatment of Children, 24(4), 448–479. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42900503 [Google Scholar]

- National AfterSchool Association (2006). Understanding the afterschool workforce: Opportunities and challenges for an emerging profession. Houston, TX: Available from: http://2crsolutions.com/images/NAAUnderstandingtheAfterschoolWorkforceNovember.pdf [last accessed April 8, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2002). Scientific Research in Education Committee on Scientific Principles for Education Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V (2009). The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine, 39(11), 1759–1762. 10.1017/S0033291709005224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4801. Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson RC, & Richards MH (2010). The after-school needs and resources of a low-income urban community: Surveying youth and parents for community change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 430–440. 10.1007/s10464-010-9309-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, & Hoagwood K (2001). Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services, 52(9), 1190–1197. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Mehta TG, Frazier SL, & Shernoff ES (2013). Clinical supervision in effectiveness and implementation research. Invited for Special Issue: Advances in Applying Treatment Integrity Research for Dissemination and Implementation Science. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20, 44–59. 10.1111/cpsp.12022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Osgood DW, Oh Y, & Caldwell LC (2018). Promoting afterschool quality and positive youth development: Cluster randomized trial of the pax good behavior game. Prevention Science, 19(2), 159–173. 10.1007/s11121-017-0820-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler A, & Goodman RM (1989). How to institutionalize health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion, 3, 34–43. 10.4278/0890-1171-3.4.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, & Davis RL (1999). Accelerating the diffusion of innovations using opinion leaders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 566, 55–67. 10.1177/000271629956600105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vescio V, Ross D, & Adams A (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 80–91. 10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wade CE (2015). The longitudinal effects of after-school program experiences, quantity, and regulatable features on children’s social-emotional development. Children and Youth Services Review, 48, 70–79. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, Brunette M, Torrey WC, Coots L, ... Drake RE (2008). The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatric Services, 59(7), 732–737. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohalem N, Pittman K, & Moore D (2006). Growing the Next Generation of Youth Work Professionals: Workforce Opportunities and Challenges. Houston, TX: Cornerstones for Kids. [Google Scholar]