Abstract

Background:

Rotavirus vaccination was introduced in the United States in 2006. Our objectives were to examine reductions in diarrhea-associated health care utilization after rotavirus vaccine implementation and to assess direct vaccine effectiveness (VE) in US children.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study using claims data of US children under 5 years of age. We compared rates of diarrhea-associated health care utilization in prevaccine versus postvaccine introduction years. We also examined VE and duration of protection.

Results:

Compared with the average rate of rotavirus-coded hospitalizations in the prevaccine years, overall vaccine rates were reduced by 75% in 2007 to 2008, 60% in 2008 to 2009, 94% in 2009 to 2010, 80% in 2010 to 2011, 97% in 2011 to 2012, 88% in 2012 to 2013, 98% in 2013 to 2014 and 92% in 2014 to 2015. RotaTeq-adjusted VE was 88% against rotavirus-coded hospitalization among 3–11 months of age, 88% in 12–23 months of age, 87% in 24–35 months of age, 87% in 36–47 months of age and 87% in 48–59 months of age. Rotarix-adjusted VE was 87% against rotavirus-coded hospitalization among 3–11 months of age, 86% in 12–23 months of age and 86% in 24–35 months of age.

Conclusion:

Implementation of rotavirus vaccines has substantially reduced diarrhea-associated health care utilization in US children under 5 years of age. Both vaccines provided good and enduring protection through the fourth year of life against rotavirus hospitalizations.

Keywords: rotavirus, diarrhea, United States, RotaTeq, Rotarix, rotavirus vaccine, vaccine effectiveness

Before the introduction of rotavirus vaccines—RotaTeq (RV5) Merck & Co., Inc. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) in 2006 and Rotarix (RV1) (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) in 2008—rotavirus was the leading cause of severe diarrhea in US children < 5 years of age.1–3 Previous studies, including those using data from Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, have found that after the implementation of rotavirus vaccination, diarrhea-associated health care utilization in US children has significantly declined, and both vaccines provided good and durable protection.4–8 We extend the previous work on MarketScan claims data for 2007 to 2011 among children < 5 years old by examining 4 additional years (2012 to 2015) of data to (1) assess rotavirus vaccine coverage; (2) examine the total effects of rotavirus vaccination; and (3) analyze direct vaccine effectiveness (VE) and duration of protection.

METHODS

Data Source and Identification of Diarrhea-associated Health Care Events

We examined data from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (CCAE) from 2001 to 2015.9 MarketScan data were extracted from insurance claims and contain deidentified health care information from various public and private health plans. Medicaid recipients were not included. We identified diarrhea-associated health care events using standard International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes.4–5 A hospitalization was defined as an event if coded as the primary discharge diagnosis or listed in any of the 15 diagnosis categories from the inpatient-admission table. An outpatient visit was counted if specified in 1 of the 2 diagnosis fields in the outpatient-service table. Emergency department (ED) visit was included (ie, not hospitalizations or outpatient visits) if “urgent care facility” or “emergency room” was specified in either the inpatient-services table or the outpatient-services table. Patients evaluated for more than 1 setting for the same diarrhea episode had their visit included for each setting in which they were evaluated for the single episode.

RV5 and RV1 Coverage

Vaccine coverage was examined using data from January 2006 to June 2015. Coverage was defined as receipt of at least 1 dose of RV5 or RV1 in a subgroup of children with continuous enrollment from birth to at least 3 months of age. The criterion of continuous enrollment ensured that any vaccinations given to children were captured in the database.

Children from states with universal vaccination programs that included rotavirus vaccine at any time during the assessment period or where rotavirus vaccine inclusion in the universal vaccination program could not be determined were excluded from the coverage evaluation. This was to control for any bias introduced as vaccination in those states was unlikely to have been billed to third-party payers and therefore not captured in MarketScan database.

Current Procedural Terminology codes 90680 and 90681 were used to identify children who received RV5 and RV1, respectively. The coverage results were validated by comparing the proportion of children who had received at least 1 diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) dose by 3 months of age in the MarketScan Database among the same cohort with the DTaP coverage from the National Immunization Survey reports.10

Total Effects of Rotavirus Vaccination

We examined the total effects of vaccination, which are the direct benefits of the vaccine in vaccinated children combined with the indirect benefits in unvaccinated children. Diarrhea-associated health care utilization rates were calculated for enrolled children < 5 years of age who were seen in inpatient, EDs and outpatient settings. In addition, rotavirus-specific coded hospitalizations were examined. Rates were calculated by the number of health care events per 10,000 person-years. We used the number of days each child was enrolled per calendar month and year of the study as the follow-up time in calculating utilization rates per 10,000 person-years of follow-up. We assessed the total effects of vaccination by comparing the same study population before and after vaccine introduction. Thus, data from all states, including those with universal vaccination programs, were included in the analysis of trends. Temporal trends of the diarrhea-associated health care utilization rate during the entire study period were evaluated. We also compared rotavirus-coded hospitalization and diarrhea-associated health care utilization rates during each of the postvaccine years of 2007 to 2015 (July to June) with the annual mean rates during the 5-year prevaccine baseline period from July 2001 to June 2006, according to age group. We excluded July 2006 to June 2007 from the postvaccine analysis as this was considered a transition period, as the first rotavirus vaccine was introduced in February 2006. Poisson regression models were fitted to estimate rate reductions and 95% confidence intervals.

VE and Duration of Protection From Rotavirus Vaccination

To examine direct vaccine benefits from RV5 and RV1, we compared rates of rotavirus-coded hospitalization and diarrhea-associated health care utilization among vaccinated versus age-eligible unvaccinated children by age group. A single child’s diarrhea-associated health care event was restricted to 1 event per age group. All children who were age-eligible to receive RV5 or RV1 and who were continuously enrolled for the entire time period were included. RV5 age-eligible children were those younger than the first dose upper limit of 14 weeks and 6 days when RV5 was licensed. RV1 age-eligible children were those younger than the first dose upper limit of 12 weeks (initial recommendation) when RV1 was licensed. Children from states with universal vaccination programs or those who had received mixed vaccine schedules with both RV1 and RV5 doses were excluded. Poisson regression models were fitted to estimate rate ratio and 95% confidence intervals associated with RV5 or RV1 administration adjusting for birth quarter. The adjusted rate ratios were subtracted from 1 to obtain adjusted VE estimates.

RESULTS

RV5 and RV1 Coverage

In the cohort of > 1,124,000 children < 5 years of age from 39 states, 69% had received at least 1 dose of RV5, and 15% had received at least 1 dose of RV1 by December 31, 2014 (Table 1). Coverage for both vaccines increased gradually in all age groups. After RV5 licensure, coverage increased from 64% on December 31, 2007, to 72% on December 31, 2014, in children < 1 year old. In the same time period, coverage increased from 23% to 70% in 1 year old and 8% to 68% among 2–4-year-old children. Similarly, after RV1 introduction, RV1 coverage continued to increase from 12% on December 31, 2009, to 16% by December 31, 2014, in < 1 year old, 1% to 16% in 1 year old and 0% to 14% in children 2–4 years old. In the same cohort, the proportion of children who had received at least 1 DTaP dose by 3 months of age was 92%, in comparison with 88% coverage reported by National Immunization Survey 2014 data.10

TABLE 1.

Annual Rates of Rotavirus-Coded and Diarrhea-Associated Health Care Utilization Among Children < 5 Years of Age Before and After Rotavirus-Vaccine Introduction by Age Group and Health Care Setting, 2001 to 2015

| Coverage* | Rotavirus-coded Hospitalizations | Diarrhea-associated Hospitalizations | Diarrhea-associated ED Visits | Diarrhea-associated Outpatient Visits |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV5† | RV1‡ | Rate, n/10,000 PY | Rate Reduction (95% CI), % | Rate, n/10,000 PY | Rate Reduction (95% CI), % | Rate, n/10,000 PY | Rate Reduction (95% CI), % | Rate, n/10,000 PY | Rate Reduction (95% CI), % | |

| < 1 year old | ||||||||||

| 2001–2006§ | NA | NA | 16 | Ref. | 65 | Ref. | 212 | Ref. | 1713 | Ref. |

| 2007–2008 | 64 | NA | 3 | 81 (77–84) | 50 | 24 (20–27) | 204 | 4 (1–6) | 1608 | 6 (5–7) |

| 2008–2009 | 73 | NA | 4 | 78 (74–81) | 45 | 30 (27–34) | 185 | 13 (11–15) | 1499 | 13 (12–13) |

| 2009–2010 | 64 | 12 | 1 | 95 (93–96) | 34 | 47 (45–50) | 131 | 38 (37–40) | 1197 | 30 (30–31) |

| 2010–2011 | 68 | 10 | 2 | 88 (85–90) | 36 | 45 (43–48) | 140 | 34 (32–36) | 1211 | 29 (29–30) |

| 2011–2012 | 67 | 15 | 0 | 98 (96–98) | 31 | 52 (49–54) | 133 | 37 (36–39) | 1158 | 32 (32–33) |

| 2012–2013 | 70 | 15 | 1 | 91 (89–93) | 34 | 48 (45–51) | 151 | 29 (27–31) | 1192 | 30 (30–31) |

| 2013–2014 | 72 | 16 | 1 | 97 (95–98) | 28 | 57 (54–59) | 148 | 30 (29–32) | 1196 | 30 (30–31) |

| 2014–2015 | 72 | 16 | 1 | 93 (91–95) | 27 | 58 (55–61) | 140 | 34 (32–36) | 1135 | 34 (33–34) |

| 1 year old | ||||||||||

| 2001–2006§ | NA | NA | 33 | Ref. | 96 | Ref. | 324 | Ref | 2376 | Ref |

| 2007–2008 | 23 | NA | 9 | 72 (69–76) | 56 | 41 (38–44) | 282 | 13 (11–15) | 2265 | 5 (4–6) |

| 2008–2009 | 64 | NA | 9 | 74 (71–77) | 60 | 38 (35–41) | 298 | 8 (6–10) | 2355 | 1 (0–2) |

| 2009–2010 | 72 | 1 | 1 | 96 (95–97) | 35 | 64 (62–66) | 198 | 39 (37–40) | 1825 | 23 (23–24) |

| 2010–2011 | 64 | 12 | 4 | 87 (85–89) | 39 | 59 (57–61) | 220 | 32 (30–34) | 1933 | 19 (18–19) |

| 2011–2012 | 68 | 10 | 1 | 98 (97–99) | 28 | 71 (69–72) | 184 | 43 (42–45) | 1743 | 27 (26–27) |

| 2012–2013 | 67 | 15 | 3 | 91 (89–92) | 34 | 64 (62–66) | 245 | 24 (23–26) | 1943 | 18 (18–19) |

| 2013–2014 | 71 | 15 | 0 | 99 (98–99) | 23 | 76 (75–78) | 197 | 39 (37–41) | 1711 | 28 (27–29) |

| 2014–2015 | 70 | 16 | 2 | 94 (92–95) | 30 | 69 (67–71) | 245 | 24 (22–26) | 1847 | 22 (22–23) |

| 2–4 years old | ||||||||||

| 2001–2006§ | NA | NA | 8 | Ref. | 32 | Ref. | 130 | Ref | 871 | Ref. |

| 2007–2008 | 0 | NA | 2 | 72 (67–76) | 21 | 34 (31–37) | 119 | 9 (7–11) | 871 | 0 (−1 to 1) |

| 2008–2009 | 8 | NA | 6 | 26 (19–32) | 29 | 9(5–13) | 155 | −19 (−21 to −17) | 984 | −13 (−14 to −12) |

| 2009–2010 | 29 | 0 | 1 | 89 (87–91) | 17 | 49 (46–51) | 105 | 19 (17–21) | 795 | 9 (8–9) |

| 2010–2011 | 53 | 0 | 3 | 63 (59–67) | 20 | 37 (35–40) | 124 | 5 (3–7) | 865 | 1 (0–1) |

| 2011–2012 | 62 | 5 | 0 | 96 (95–97) | 14 | 57 (55–59) | 95 | 27 (25–28) | 735 | 16 (15–16) |

| 2012–2013 | 67 | 8 | 1 | 80 (77–83) | 17 | 47 (44–49) | 135 | −4 (−6 to −2) | 860 | 1 (0–2) |

| 2013–2014 | 68 | 11 | 0 | 97 (96–98) | 13 | 61 (59–63) | 105 | 19 (18–21) | 732 | 16 (15–17) |

| 2014–2015 | 68 | 14 | 1 | 89 (86–91) | 13 | 59 (57–61) | 127 | 2 (0–4) | 823 | 5 (5–6) |

| < 5 years old | ||||||||||

| 2001–2006§ | NA | NA | 14 | Ref. | 52 | Ref. | 185 | Ref | 1348 | Ref. |

| 2007–2008 | 17 | NA | 4 | 75 (72–77) | 35 | 33 (31–35) | 169 | 9 (7–10) | 1303 | 3 (3–4) |

| 2008–2009 | 32 | NA | 6 | 60 (58–63) | 39 | 25 (23–27) | 188 | −2 (−3 to 0) | 1360 | −1 (−1 to 0) |

| 2009–2010 | 45 | 3 | 1 | 94 (93–95) | 24 | 54 (52–55) | 128 | 31 (30–32) | 1079 | 20 (20–20) |

| 2010–2011 | 58 | 5 | 3 | 80 (78–81) | 27 | 47 (46–49) | 145 | 22 (21–23) | 1139 | 16 (15–16) |

| 2011–2012 | 64 | 8 | 0 | 97 (97–98) | 21 | 60 (59–61) | 120 | 35 (34–36) | 1015 | 25 (24–25) |

| 2012–2013 | 67 | 11 | 2 | 88 (86–89) | 24 | 53 (52–54) | 158 | 15 (13–16) | 1134 | 16 (16–16) |

| 2013–2014 | 69 | 13 | 0 | 98 (97–98) | 18 | 65 (63–66) | 132 | 29 (28–30) | 1021 | 24 (24–25) |

| 2014–2015 | 69 | 15 | 1 | 92 (91–93) | 20 | 62 (61–63) | 151 | 18 (17–19) | 1085 | 20 (19–20) |

CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; NA not applicable; PY, person-year; Ref., reference group.

Some states (Alaska, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, Wyoming) with RV vaccines through a state-sponsored childhood vaccine program were excluded from the coverage evaluation.

Coverage was defined as receipt of at least 1 dose of RV5 by December 31, 2007; December 31, 2008; December 31, 2009; December 31, 2010; December 31, 2011; December 31, 2012; December 31, 2013; December 31, 2014, in children who had been in the database since birth and for at least 3 months continuously enrolled. Coverage for children < 1 year of age was restricted to those who were eligible for vaccination (i.e., children 3–11 months).

Coverage was defined as receipt of at least 1 dose of RV1 by December 31, 2009; December 31, 2010; December 31, 2011; December 31, 2012; December 31, 2013: December 31, 2014, in children with the same criteria as defined for RV5 coverage. Because RV1 was not introduced until April 2008, coverage of RV1 begins with the first full season starting 2009.

For 2001 to 2006, the average annual rate for the time period is shown.

Total Effects of Rotavirus Vaccination

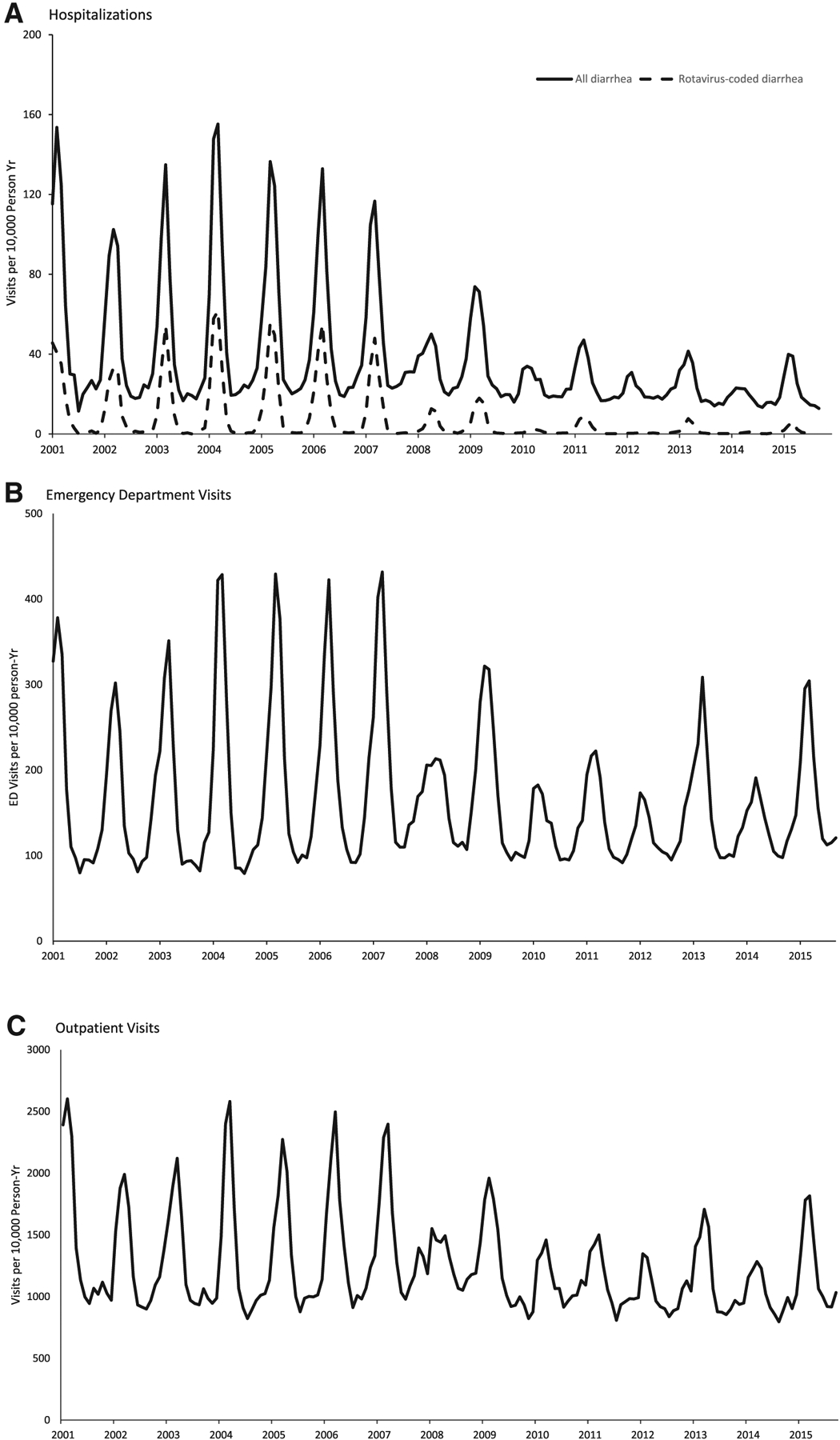

During 2001 to 2015, a total of 71,808 hospitalizations, 375,559 ED visits and 2,855,649 outpatient visits associated with diarrhea were recorded among children < 5 years of age in the MarketScan database. In the prevaccine years, the monthly diarrhea-associated health care utilization rates had an annual seasonal pattern with a sharp peak during February to March in all health care settings, which coincided with the seasonal pattern of rotavirus-coded hospitalization (Fig. 1). However, in postvaccine years, the monthly rotavirus-coded hospitalization and diarrhea-associated health care utilization rates in all settings substantially decreased and the seasonal patterns changed, with the emergence of a biennial seasonal pattern with greater rates during odd year rotavirus seasons (2009, 2011, 2013 and 2015) compared with even year rotavirus seasons (2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014).

FIGURE 1.

Diarrhea-associated health care utilization rates among children, 5 years of age, 2001 to 2015.

Compared with prevaccine years, a significant reduction in rotavirus-coded hospitalization rates was observed in all 8 postvaccine years among all age groups (Table 1). The reductions exceeded the combined RV5 and RV1 coverage in each of the postvaccine years; in the early years of the vaccine program, large reductions were seen in older children despite minimal vaccine coverage in these age groups.

In each of the postvaccine years compared with prevaccine years, significant reductions were recorded in all-cause diarrhea-associated hospitalizations among children < 5 years of age (Table 1). Significant declines in diarrhea-associated ED visit and outpatient visit rates were also observed in children < 1 year of age in each of the postvaccine years and in children < 5 years of age in postvaccine seasons after 2008 to 2009. The greatest reduction for both health care settings among < 5 years of age was observed in 2014: 29% (95% CI, 28–30%) ED visits and 24% (95% CI, 24–25%) in outpatient (Table 1).

Direct VE and Duration of Protection From Rotavirus Vaccination

RV5-adjusted VE was 88% (95% CI, 86–90%) against rotavirus-coded hospitalization among 3–11 and 12–23 months of age. RV5-adjusted VE was 87% (95% CI, 85–89%) in the older age groups. RV1-adjusted VE was 87% (95% CI, 80–91%) against rotavirus-coded hospitalization among 3–11 months of age, 86% (95% CI, 80–91%) in 12–23 months of age and 86% (95% CI, 79– 91%) in 24–35 months of age (Table 2). Because of low numbers of rotavirus-coded hospitalizations among older age groups, VE estimates for RV1 could not be calculated.

TABLE 2.

VE and Duration of Protection among Children Who Received at Least 1 Dose of RV5 or RV1 Versus Unvaccinated Children by Age*

| Health Care Utilization Rate, n/10,000 | Health Care Utilization Rate, n/10,000 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV5 | Unvaccinated‡ | VE (95% CI), % | RV1 | Unvaccinated§ | VE (95% CI), % | |

| Rotavirus-coded hospitalizations | ||||||

| 3–11 | 0.88 | 7.34 | 88 (86–90) | 0.75 | 5.83 | 87 (80–91) |

| 12–23 | 2.04 | 25.31 | 88 (86–90) | 0.89 | 22.99 | 86 (80–91) |

| 24–35 | 1.28 | 10.78 | 87 (85–89) | 5.97 | 9.76 | 86 (79–91) |

| 36–47 | 0.17 | 4.88 | 87 (85–89) | 0.00 | 4.94 | NA |

| 48–59 | 2.33 | 3.15 | 87 (85–89) | 0.00 | 2.56 | NA |

| Diarrhea-associated Hospitalizations | ||||||

| 3–11 | 39 | 59 | 43 (40–45) | 37 | 57 | 41 (36–46) |

| 12–23 | 64 | 134 | 43 (40–45) | 66 | 144 | 42 (37–46) |

| 24–35 | 36 | 76 | 42 (40–45) | 40 | 87 | 41 (36–46) |

| 36–47 | 28 | 53 | 43 (40–45) | 19 | 64 | 41 (35–46) |

| 48–59 | 23 | 32 | 42 (39–44) | 23 | 40 | 41 (34–46) |

| Diarrhea-associated emergency departments | ||||||

| 3–11 | 203 | 245 | 23 (22–25) | 194 | 244 | 24 (21–26) |

| 12–23 | 382 | 575 | 23 (22–25) | 451 | 641 | 24 (21–26) |

| 24–35 | 246 | 412 | 24 (22–25) | 264 | 503 | 24 (21–26) |

| 36–47 | 189 | 276 | 25 (23–26) | 205 | 358 | 27 (24–29) |

| 48–59 | 179 | 263 | 25 (23–26) | 193 | 376 | 25 (22–29) |

| Diarrhea-associated outpatient visits | ||||||

| 3–11 | 1511 | 1343 | −4 (−5 to −3) | 1472 | 1317 | −5 (−7 to −4) |

| 12–23 | 2790 | 2786 | −4 (−5 to −3) | 2961 | 3047 | −5 (−6 to −4) |

| 24–35 | 1752 | 1863 | −3 (−4 to −3) | 2002 | 2185 | −4 (−6 to −3) |

| 36–47 | 1187 | 1266 | −2 (−3 to −1) | 1386 | 1586 | −2 (−4 to −1) |

| 48–59 | 965 | 1216 | −2 (−3 to −1) | 1371 | 1683 | −3 (−4 to −1) |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; PY, person-year.

Vaccination status was determined by the presence or absence of a current procedural terminology code for receipt of at least 1 dose of RV5. Children who were either from states with universal vaccination programs or had received mixed vaccine schedules with both RV1 and RV5 doses were excluded.

Age at hospitalization for a diarrhea-associated event.

Children who were age-eligible for the RV5 vaccine as of February 3, 2006, when RV5 was first recommended (ie, age less than the first-dose upper limit of 14 wk and 6 d when RV5 was licensed on February 3, 2006) and who were continuously enrolled in their insurance plan for at least 3 mo.

Children who were age-eligible for the RV1 vaccine as of April 3, 2008, when RV1 was first recommended (ie, age less than the first-dose upper limit of 12 wk (previous recommendation) when RV1 was licensed on April 3, 2008) and who were continuously enrolled in their insurance plan for at least 3 mo.

We observed significant VE estimates against all-cause diarrhea-associated hospitalizations and ED visits in vaccinated children with little variation among age groups (Table 2). RV5-adjusted VE estimates ranged from 43% (95% CI, 40–45%) against diarrhea-associated hospitalizations in 3–11 months of age to 42% (95% CI, 39–44%) in 48–59 months of age. Similar VE estimates were seen among those vaccinated with RV1. RV1-adjusted VE was 41–42% among all age groups. Furthermore, the adjusted VE estimates ranged from 23% to 25% against diarrhea-associated ED visits for RV5, and for RV1, the adjusted VE ranged from 24% to 27%. However, we did not detect any VE against diarrhea-associated outpatient visits for either vaccines.

DISCUSSION

Overall, among children < 5 years of age, we observed declines in rate of rotavirus-coded hospitalization of 60–98% and in diarrhea-associated hospitalizations of 25–65% in each of the 8 postvaccine rotavirus seasons. Declines in diarrhea-associated ED visits and outpatient visits were observed in each of the 6 rotavirus seasons after 2009; these declines were less than the declines in diarrhea-associated hospitalizations as would be expected, given that rotavirus vaccines demonstrate greater efficacy against more severe gastroenteritis. For all health care outcomes, greater declines observed in later postvaccine years as vaccine coverage increased. Seasonal peaks corresponding to months of rotavirus activity in diarrhea-associated hospitalizations, ED visits and outpatient visits were blunted after vaccine introduction. These results strongly suggest that reductions in rotavirus-coded hospitalization and diarrhea-associated health care utilization were caused by rotavirus vaccination, and not because of unmeasured extraneous factors. Declines in rotavirus-coded hospitalization rates exceeded the combined coverage of RV5 and RV1 in each of the postvaccine years, and large declines were seen in some early postvaccine seasons (eg, 2007 to 2008) despite limited vaccine uptake, indicating that vaccination is likely conferring indirect benefits to unvaccinated children by reducing the overall transmission of rotavirus in the community.

We found both RV1 and RV5 to be highly effective against rotavirus hospitalizations, and both vaccines provide similar protection. The birth-quarter–adjusted VE estimates were similar across all 5 age groups for both vaccines. The level of protection obtained from both RV5 and RV1 vaccination against rotavirus-specific hospitalization was persistent through the fourth year of life, with no evidence of waning protection. The high and sustained effectiveness of both vaccines demonstrated in these findings was consistent with other US studies using different methodologies and data sources.11–15 The direct VE was higher against diarrhea-hospitalization than in ED and outpatient visits. A possible explanation is that rotavirus accounts for a greater percentage of diarrhea cases in the hospital than in other health care settings, and the vaccine has been shown to be more effective against more severe rotavirus gastroenteritis.16

Rotavirus vaccine coverage, though modest, has increased steadily over the years. By the end of 2014, coverage had reached 84% of children under 5 years of age and 88% coverage among < 1 year old. However, the rotavirus coverage was still about 11% lower than DTaP coverage for the same cohort in MarketScan data. RV1 that was introduced 2 years later than RV5 had significantly lower coverage as compared with RV5 coverage in all age groups.

There were some limitations of this study. First, our analysis only included insured children. Uninsured children and children on Medicaid were not captured. The data did not include information on ethnicity/race or socioeconomic status. Additionally, MarketScan data typically come from large employers; therefore, small firms were not well represented. Second, states with universal vaccination programs were not included in the total effects and direct VE analysis. We restricted 13 states for the period 2007 to 2015. However, it is possible we did not capture all the vaccinated children during this transition year. Third, the analysis only adjusted for birth-quarters; we did not control for all other possible confounders. We were not aware of other factors in this study that could potentially influence rotavirus vaccine coverage and confound VE estimates. Fourth, rotavirus cases were identified based on the appearance of an ICD-9 diagnosis code for rotavirus on health care claims; therefore, the validity of the results depends on the accuracy and consistency of physician-assigned diagnosis of rotavirus and the diagnostic coding. Rotavirus laboratory testing and coding were not consistent across all health care settings; particularly, testing for rotavirus was not common in ED visits and outpatient visits.4–6 Therefore, we were not able to assess rotavirus-coded ED and outpatient visits.

In conclusion, after the implementation of rotavirus vaccination program, rotavirus hospitalizations and diarrhea-related health care utilization have declined dramatically among US children under 5 years of age. Both rotavirus vaccines provide a strong and durable protection against rotavirus hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresee JS, et al. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:304–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortese MM, Parashar UD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevention of rotavirus disease: updated guidelines for use of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1412–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes JE, Curns AT, Tate JE, et al. Rotavirus vaccine and health care utilization for diarrhea in U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1108–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leshem E, Moritz RE, Curns AT, et al. Rotavirus vaccines and health care utilization for diarrhea in the United States (2007–2011). Pediatrics. 2014;134:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah MP, Tate JE, Steiner CA, et al. Decline in emergency department visits for acute gastroenteritis among children in 10 US states after implementation of rotavirus vaccination, 2003 to 2013. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:782–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leshem E, Tate JE, Steiner CA, et al. Acute gastroenteritis hospitalizations among US children following implementation of the rotavirus vaccine. JAMA. 2015;313:2282–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilgore A, Donauer S, Edwards KM, et al. Rotavirus-associated hospitalization and emergency department costs and rotavirus vaccine program impact. Vaccine. 2013;31:4164–4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (USA) Database. Ann Arbor, MI: Thomson Reuters (Healthcare); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estimated vaccination coverage with individual vaccines by 3 months of age. National Immunization Survey. 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/child/data/tables-2014.html. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- 11.Payne DC, Selvarangan R, Azimi PH, et al. Long-term consistency in rotavirus vaccine protection: RV5 and RV1 vaccine effectiveness in US children, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1792–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staat MA, Payne DC, Donauer S, et al. ; New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN). Effectiveness of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e267–e275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortese MM, Immergluck LC, Held M, et al. Effectiveness of monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e25–e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Immergluck LC, Parker TC, Jain S, et al. Sustained effectiveness of monovalent and pentavalent rotavirus vaccines in children. J Pediatr. 2016;172:116–120.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panozzo CA, Becker-Dreps S, Pate V, et al. Direct, indirect, total, and overall effectiveness of the rotavirus vaccines for the prevention of gastroenteritis hospitalizations in privately insured US children, 2007–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:895–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass RI, Parashar U, Patel M, et al. The control of rotavirus gastroenteritis in the United States. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:36–52; discussion 53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]