Abstract

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is overexpressed in over 20% of breast cancers. The dimerization of HER2 receptors leads to the activation of down-stream signals enabling proliferation and survival of malignant phenotypes. Owing to the high expression levels of HER2, combination therapies are currently required for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Here, we designed non-toxic transformable peptides that self-assemble into micelles in aqueous conditions, but, upon binding to HER2 on cancer cells, transform into nanofibers, which disrupt HER2 dimerization and subsequent downstream signalling events, leading to apoptosis of cancer cells. The phase transformation of the peptides enables specific HER2-targeting and inhibition of HER2 dimerization blocks the expression of proliferation and survival genes in the nucleus. We demonstrate that these transformable peptides can be used as a monotherapy for the treatment of HER2+ breast cancer in mouse xenograft models.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is overexpressed in over 20% breast cancers, and to a lesser degree in gastric cancers, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancers and bladder cancers.1-5 Unlike those cancers caused by mutated or fusion oncogenes (e.g. EGFR in lung cancers) which respond well to monotherapy,6, 7 cancers with HER2 overexpression often require drug combinations.8, 9 It is because this latter group of tumours are driven by gene amplification and massive overexpression of HER2. HER2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is normally activated via induced dimerization with itself or with its family members EGFR, HER3 or HER4.10-12 In HER2 positive tumours, HER2s are massively overexpressed and constitutively dimerized, leading to unrelenting activation of down-stream proliferation and survival pathways and malignant phenotype. Here, we report on a HER2-mediated, peptide-based, and non-toxic transformable nanoparticle that is highly efficacious as a monotherapy against HER2+ breast cancer xenograft models.

Supramolecular chemistry involves chemical systems formed by self-assembly of molecular subunits via non-covalent interactions.13-16 Harnessing the advantages of the dynamic nature and adaptive behaviour of supramolecular chemistry, Xu et al. and Wang et al. proposed an “in vivo self-assembly” strategy for in situ construction of nanomaterials in vivo.17-21 Here, we designed and synthesized a smart supramolecular peptide, BP-FFVLK-YCDGFYACYMDV, capable of (1) assembling into nanoparticles (NPs) under aqueous condition and in blood circulation, and (2) in situ transformation into nanofibrillar (NFs) structure upon binding to the cell surface HER2 at the tumour sites. This transformable peptide monomer (TPM) was comprised of three discrete functional domains: (1) the bis-pyrene (BP) moiety with aggregation induced emission (AIE) property for fluorescence reporting, and as a hydrophobic core to induce the formation of micellar NPs, (2) the KLVFF β-sheet forming peptide domain originated from β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide,22-24 and (3) the YCDGFYACYMDV disulfide cyclic peptide HER2-binding domain,25-27 an anti-HER2/neu antibody peptidic mimic derived from the primary sequence of the CDR-H3 loop of the anti-HER2 rhumAb 4D5. Under aqueous condition, TPM would self-assemble into spherical NPs, in which BP and KLVFF domains constituted the hydrophobic core and YCDGFYACYMDV peptide constituted the negatively charged hydrophilic corona. NPs, injected intravenously (i.v.) into mice bearing HER2+ tumours, were found to be preferentially accumulated at the tumour site. Upon interaction with HER2 displayed on the tumour cell surface, the NPs would undergo in situ transformation into fibrillar structural network, which in turn suppress the dimerization of HER2 and prevent downstream cell signaling and expression of proliferation and survival genes in the nucleus (Schema 1). These structural transformation-based supramolecular peptides represent a class of receptor-mediated targeted nanotherapeutics against cancers.

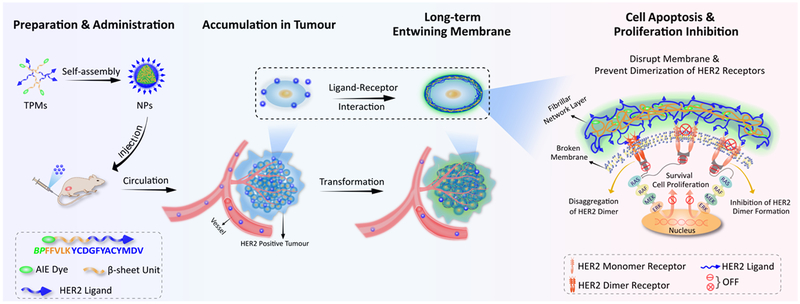

Schema 1.

Schematic illustration of self-assembly, accumulation and in situ fibrillar transformation of transformable peptide monomers (TPM) in tumour tissue of HER2 positive cancer, and the extracellular and intercellular mechanisms of apoptosis promotion and proliferation inhibition events.

Self-assembly and fibrillar-transformation

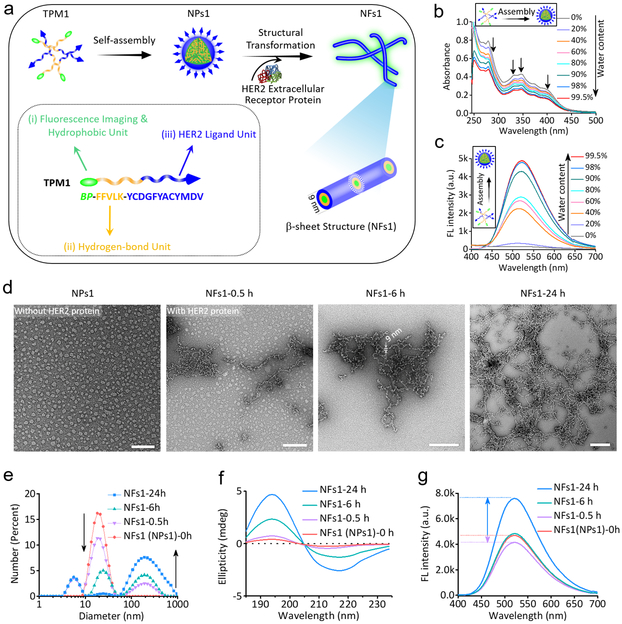

The transformable peptide monomer 1 (TPM1), BP-FFVLK-YCDGFYACYMDV, and the negative control peptides TPM2 (BP-GGAAK-YCDGFYACYMDV), TPM3 (BP-FFVLK-PEG1000) and TPM4 (BP-GGAAK-PEG1000) were synthesized and characterized (Fig. 1a, Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2). As the proportion of water in the mixed solvent (water and DMSO) of TPM1 solution was increased, there was a gradual decrease in absorption peaks (250–450 nm), reflecting the gradual formation of nanoparticles NPs1 via self-assembly (Fig. 1b). Concomitantly, the fluorescence peak at 520 nm was found to increase dramatically, due to the AIE fluorescence properties of BP dye (Fig. 1c).28, 29 TPM2, TPM3 and TPM4 all showed similar self-assembling property (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Nanoparticles (NPs1, NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4) were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3b). The diameters of NPs1–4 were found to be around 20 nm, 30 nm, 25–60 nm and 20 nm, respectively. The critical aggregation concentrations (CAC) of NPs1–4 were calculated to be 4.2, 7.0, 10.5 and 9.8 μM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Fig. 1. The assembly and fibrillar-transformation of transformable peptide monomer 1 (TPM1) BP-FFVLK-YCDGFYACYMDV.

a, Schematic illustration of self-assembly and in situ structural transformation of TPM1. b,c, Changes in (b) UV-vis absorption and (c) fluorescence of NPs1 upon gradual addition of water (from 0% to 99.5%) into a solution of NPs1 in DMSO; Ex = 380 nm; experiments were repeated three times. d, TEM images of initial NPs1 and NPs1 transformed into nanofibers (NFs1) after interaction with HER2 protein (Mw ≈ 72 KDa) at different time points (0.5, 6 and 24 h). The scale bar in d is 100 nm. Experiments were repeated three times. e-g, Variation of (e) size distribution, (f) CD spectra and (g) fluorescence signal of initial NPs1 and NFs1 at the different time points. Representative picture from three independent tests is shown. The molar ratio of HER2 protein/peptide ligand was approximately 1:1000.

Table 1.

Molecular composition of transformable peptide monomers (TPM) 1-4.

| TPM | BP | FFVLK | GGAAK | YCDGFYACYMDV | PEG1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | − | + | − |

| 2 | + | − | + | + | − |

| 3 | + | + | − | − | + |

| 4 | + | − | + | − | + |

TPM1 BP-FFVLK-YCDGFYACYMDV (with HER2 binding peptide and β-sheet forming peptide)

TPM2 BP-GGAAK-YCDGFYACYMDV (with HER2 binding peptide, but without β-sheet forming peptide)

TPM3 BP-FFVLK-PEG1000 (without HER2 binding peptide, but with β-sheet forming peptide)

TPM4 BP-GGAAK-PEG1000 (without HER2 binding peptide nor β-sheet forming peptide).

Soluble extracellular domain of HER2 protein was used to investigate the interaction of HER2 with NPs1 in vitro. The minimum ratio of HER2 protein/peptide ligand required for maximum promotion of fibrillar network formation was determined to be 1:1000 (Supplementary Fig. 4). NPs1 was found to maintain a spherical structure at around 20 nm before interaction with HER2 (Fig. 1d). After incubation at room temperature with HER2 protein for 30 min, a small number of particulate nanofibrillar structures (NFs1, width diameter about 9 nm) became apparent; more NFs1 were detected at 6 h. By 24 h, a fibrillar network with a broad size distribution was clearly detected. No transformation was observed in the NPs1 preparation without the addition of HER2 protein, even after 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 5). The structural transformation from NPs1 to NFs1 was also confirmed in solution by DLS (Fig. 1e). In contrast, similar treatment of NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4 with HER2 did not reveal any significant changes over 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 6). Common features of the TPMs that formed these three negative control NPs were the lack of concurrent presence of the two essential domains for receptor-mediated transformation in NPs1: HER2 ligand and KLVFF β-sheet forming peptide. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy analysis of the transformation process showed a gradual progression of the negative signal at 216 nm and positive signal at 195 nm progression and therefore β-sheet formation over 24 h (Fig. 1f).22, 30 No obvious change of CD signal was observed in NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4 (Supplementary Fig. 7). The unique AIE fluorescent property of BP was used to monitor the kinetics of TPM1 transformation (Fig. 1g). The fluorescence intensity of BP in NPs1 dropped about 11.8% after addition of HER2 for 30 min, but turned around and increased as transformation to NFs1 progressed, and eventually reached about 61.7% increase by 24 h. A more detail study and interpretation of this phenomenon is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a,b. The zeta potential of NPs1 was found to change from −12 to −30 mV over time during the transformation process (Supplementary Fig. 8c,d). Serum stability and proteolytic stability of NPs over 7 d at 37 °C was good (Supplementary Fig. 8e-l).

The morphological characterizations on cell surface

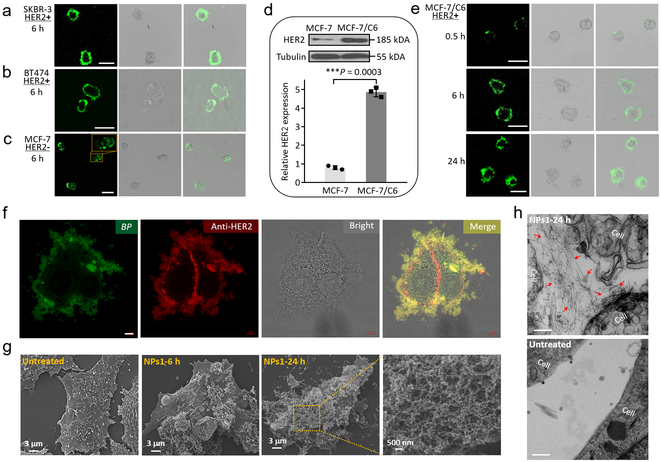

Six hours after incubating HER2+ breast cancer cell lines (SKBR-3 and BT474 cells) with NPs1, a strong green fluorescence signal was observed on the cell surface but not inside the cells (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, for MCF-7 breast cancer cells with low-expression level of HER2, the majority of the fluorescent signal was found to reside inside the cells after 6–24 h (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating that cell surface display of HER2 protein was required for transformation of NPs1 to nanofibrillar network at the cell vicinity. Cellular uptake of NPs1 by MCF-7 cells was found to be inhibited by amiloride (2 mM), β-CD (5 mM), and hypertonic sucrose (450 mM), indicating that NPs1 might enter the cell by caveolae-dependent, clathrin-dependent and macropinocytosis-dependent endocytosis (Supplementary Fig. 10 and 11).

Fig. 2. The morphological characterizations of fibrillar-transformable NPs1 incubation with cultured HER2 positive cancer cells.

a-c, Cellular fluorescence distribution images of NPs1 interaction with (a) SKBR-3 cells (HER2+), (b) BT474 cells (HER2+) and (c) MCF-7 cells (HER2-) for 6 h. Scale bar in a-c is 50 μm. Experiments were repeated three times. d, Western blot and quantitative analysis of relative HER2 protein expression in MCF-7 cells and MCF-7/C6 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). Representative picture from three independent tests is shown. e, Cellular fluorescence distribution images of NPs1 interaction with MCF-7/C6 cells (HER2+) at the different time points (0.5, 6 and 24 h). Scale bar in e is 50 μm. Experiments were repeated three times. f, Fluorescence binding distribution images of the nanofibrillar network of NFs1 and HER2 antibody (29D8 rabbit Ab and HER2 peptide of NPs1 recognize different epitopes of HER2 receptor) on the cell membrane of MCF-7/C6 cells. HER2 antibody was used to label HER2 receptors. Scale bar in f is 5 μm. Experiments were repeated three times. g, SEM images of untreated MCF-7/C6 cells and cells treated by NPs1 for 6 h and 24 h. Experiments were repeated three times. h, TEM images of untreated MCF-7/C6 cells and cells treated by NPs1 for 24 h. The red arrow shows fibrillar network. Scale bar in h is 200 nm. Experiments were repeated three times. The concentration of NPs1 was 50 μM.

Radiotherapy is commonly used for the management of breast cancer patients.31 It has previously been reported that long-term fraction ionizing radiation (FIR) can induce HER2 expression, both clinically and in experimental models.32, 33 In fact, the HER2+ MCF-7/C6 tumour cell line used in our current study was derived from HER2 negative human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line that had undergone 30 days of FIR induction, followed by colony formation and clonal isolation (Supplementary Fig. 12).34, 35 MCF-7/C6 cells, with five-fold higher HER2 than parent MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2d), exhibit the characteristic of radiation resistance, more aggressive phenotype, and enhanced levels of cancer stem cell properties. After 30 min incubation of MCF-7/C6 cells with NPs1 (50 μM), green fluorescent dots were observed on the cell membrane (Fig. 2e). By 24 h, a luxuriant green fluorescent layer was found surrounding the entire cell.

To further validate the binding of NPs1 to HER2, we used anti-HER2 (29D8) monoclonal antibody (MAb) followed by fluorescent red secondary antibody to detect HER2 on MCF-7/C6 cells. Overlapping green fluorescence (BP) with red fluorescence (HER2) was found around the periphery of the two adjoined cells except at the adhesion interface, which was not accessible to NPs1 present in the culture medium (Fig. 2f). 3D image rendering of these two cells is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. The cellular distribution of negative control NPs (NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4) was also investigated in MCF-7/C6 cells. After 24 h incubation, the majority of the fluorescent signal was found inside the cells instead of on the cell surface, with most of the internalized nanoparticles degraded in lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 14-17). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed the presence of nanofibrillar network on the surface of NPs1-treated MCF-7/C6 cells (Fig. 2g). In contrast, no nanofibrillar structure was detected on the surface of untreated cells or cells treated with NPs2, NPs3 or NPs4 (Supplementary Fig. 18). TEM showed similar results, with abundant bundles of nanofibrils detected on the surface of and in between MCF-7/C6 cells after incubation with NPs1 for 24 h (Fig. 2h). The fibrillar structures formed further away from the cell surface was determined to be induced by tumour cell secreted exosomes displaying HER2 (Supplementary Fig. 19). No nanofibrillar structure was detected on untreated MCF-7/C6 cells or cells treated with the three negative control NPs for 24 h. Minimal amount of nanofibrils were detected on the surface of NPs1 treated MCF-7 cell with low HER2 level (Supplementary Fig. 20).

The in vitro extracellular and intracellular mechanisms

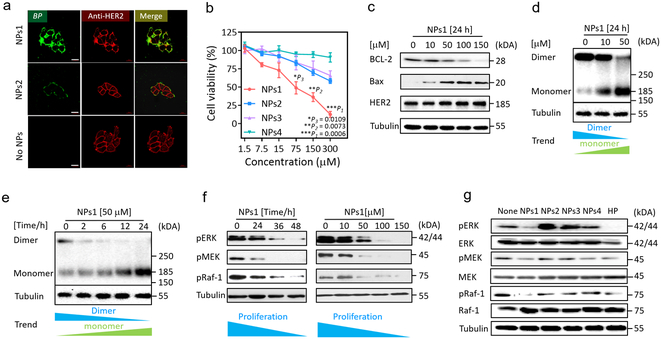

It has recently been reported that nanofibrils self-assembled from carbohydrate or peptide amphiphiles on cell membranes could alter the cell fate.36-40 It is conceivable that HER2-mediated transformation of nanoparticle to nanofibrillar network could impair HER2 dimerization leading to suppression of downstream signal transduction. To demonstrate this plausible mechanism, we first incubated MCF-7/C6 cells with NPs1, NPs2 or PBS for 8 h (Fig. 3a). As expected, NPs1 induced thick nanofibrillar network formation (fluorescent green) around the cell surface, whereas negative control NPs2 generated only a scant fluorescent green signal.

Fig. 3. The extracellular and intracellular mechanisms of fibrillar-transformable nanoparticles interaction with MCF-7/C6 breast cancer cells.

a, Fluorescence binding distribution images of NPs1 and NPs2 binding HER2 receptors of MCF-7/C6 cells for 8 h. HER2 antibody (29D8 rabbit Ab and HER2 peptide of NPs1 and NPs2 recognize different epitopes of HER2 receptor) was used to label HER2 receptors. The concentration of NPs1 and NPs2 were 50 μM. The scale bar in a is 20 μm. Experiments were repeated three times. b, The viability of MCF-7/C6 cells after incubation with NPs1-4 at the different concentration for 48 h. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent experiments. The statistical significance was calculated via a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. c, Western blot analysis of apoptosis related proteins and HER2 total protein in MCF-7/C6 cells treated by NPs1 for 24 h with different concentration. Experiments were repeated three times. d,e, Western blot analysis of inhibition and disaggregation mechanism of HER2 protein dimer in MCF-7/C6 cells treated by NPs1 (d) for 24 h with different concentration and (e) at 50 μM under different time point. Experiments were repeated three times. f, Western blot analysis of inhibition mechanism of proliferation protein in MCF-7/C6 cells treated by NPs1 at 50 μM under different time point and at 24 h under different concentration. Experiments were repeated three times. g, Western blot analysis of inhibition mechanism of proliferation protein in MCF-7/C6 cells treated by NPs1-4 and Herceptin (HP) at 36 h. The concentration of NPs1-4 were 50 μM, and the concentration of Herceptin was 15 μg/mL as a positive control group. Experiments were repeated three times.

The cytotoxic effect of NPs1 and the three negative control NPs on MCF-7/C6 cells after 48 h incubation was determined by MTS assay. Treatment with NPs1 resulted in significant cell death at a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3b). Similar results were obtained for two other HER2+ breast cancer cell lines, SKBR-3 and BT474 (Supplementary Fig. 21a,b). However, when MCF-7 cells with low HER2 level were treated by these four NPs, no obvious cytotoxicity was observed even at the highest concentration of 300 μM (Supplementary Fig. 21c). Treatment of MCF-7/C6 cells with NPs1 resulted in down-regulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and up-regulation of apoptotic protein Bax, in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3c). To study the effect of NPs1 on HER2 dimerization, we employed a simple method of brief chemical crosslinking with 0.01% glutaraldehyde followed by Western blot analysis with anti-HER2 antibody.41 This has allowed us to determine the relative level of cellular HER2 dimer and monomer. It is clear from Fig. 3d,e that NPs1 was able to inhibit HER2 dimerization in a dose and time-dependent manner, indicating that NPs1 not only could inhibit HER2 dimerization, but could also promote conversion of HER2 from dimers to monomers. In addition, MAPK pathway was suppressed at a dose-dependent manner with a significant decrease in phosphorylation level of Erk, Mek and Raf-1 over time (Fig. 3f). For the purpose of comparison, MCF-7/C6 cells were incubated with 50 μM of each NPs for 36 h, and Herceptin was used as a positive control (Fig. 3g). Like Herceptin, NPs1 was able to strongly inhibit pErk, pMek and pRaf-1. In contrast, the three negative control NPs did not significantly alter the phosphorylation level of Erk, Mek and Raf-1. Together, these data strongly support our notion that transformation of NPs1 to nanofibrillar network on the surface of HER2+ tumour cells causes inhibition of HER2 dimerization and conversion of HER2 dimers to monomers, leading to inhibition of downstream proliferation and survival cell signaling, and cell death.

In vivo evaluation of fibrillar-transformable nanoparticle

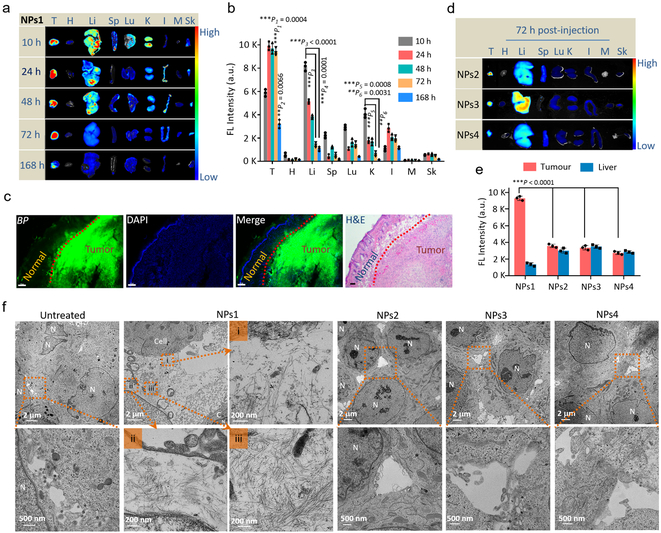

NPs1 was found to be non-toxic; blood counts, platelets, creatinine and liver function tests obtained from normal Balb/c mice treated with 8 consecutive q.o.d. doses of NPs1 were within normal limit (Supplementary Fig. 22 and 23). In vivo blood pharmacokinetic studies indicated that NPs1 possessed a long circulation time (Supplementary Fig. 24). For biodistribution studies, mice bearing MCF-7/C6 tumour were given i.v. NPs1; 10, 24, 48, 72 and 168 h later, tumour and main organs were collected for ex vivo fluorescent imaging study (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 25). Fluorescent signal persisted in tumour for over 3 days, with significant residual signal even after 7 days. In contrast, fluorescent signal in normal organs began to drop after 10 h and was almost undetectable in main organs at 72 h, and histologic examination of excised normal organs did not reveal any pathology (Supplementary Fig. 26 and 27). Fluorescent micrograph of tumour and overlying skin revealed intense fluorescent signal in tumour but negligible signal in the normal skin (Fig. 4c). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 28, the green fluorescence signal from BP was found throughout the entire tumour tissue section, and not just in the tumour periphery. In vivo biodistribution studies on NPs2–4 were also performed in the same tumour model (Supplementary Fig. 29). At 72 h, fluorescent signal of tumour derived from mice treated with NPs1 was found to be 2–3 times higher than that of mice treated with NPs2–4 (Fig. 4d,e). Prolonged retention of fluorescent signal in NPs1 treated mice, even after 7 days, could be attributed to in situ receptor-mediated transformation of NPs1 into NFs1 networks at the tumour microenvironment. TEM studies on excised tumour, 72 h after i.v. administration, showed abundant bundles of nanofibrils in the extracellular matrix of tumour sections. No such nanofibrils were observed in the negative control NP-treated and untreated mice (Fig. 4f). In addition, many cells in the tumour excised from NPs1-treated mouse appeared to be dying with large intercellular spaces. The TEM images of organs excised from the same mouse were found to be normal, without any sign of nanofibrillar networks (Supplementary Fig. 30).

Fig. 4. In vivo evaluation of fibrillar-transformable nanoparticles.

a,b, (a) Time-dependent ex vivo fluorescence images and (b) quantitative analysis of tumour tissues and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, intestine, muscle and skin) collected at 10, 24, 48, 72 and 168 h post-injection of NPs1. In b, data are presented as the mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent experiments. The statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, the fluorescence signal in tumour tissue at 72 h and 168 h compared with other organs displays tumour accumulation and in situ transformation of fibrillar network with long retention time; the fluorescence signal in liver at 10 h compared with that at 72 and 168 h displays that NPs1 could be removed rapidly from liver; the fluorescence signal in kidney at 10 h compared with that at 72 and 168 h displays that NPs1 could be removed rapidly from kidney. c, The fluorescence distribution images and H&E image of NPs1 in tumour tissue and normal skin tissue at 72 h post-injection (green colour: BP of NPs1; blue colour: DAPI; scale bar in c is 100 μm). Experiments were repeated three times. d, Time-dependent ex vivo fluorescence images of tumour tissues and major organs collected at 72 h post-injection of NPs2-4. e, Quantitative analysis of tumour tissues and livers collected at 72 h post-injection of NPs1-4. In e, data are presented as the mean ± s.d., n = 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, the fluorescence signal of tumour tissue in NPs1 group compared with that in other control groups displays that fibrillar networks in NPs1 group promote long retention time in tumour site. f, TEM images of distribution in tumour tissue and in situ fibrillar transformation of NPs1-4 at 72 h post-i.v. injection and untreated group. The dose of NPs1-4 were 8 mg/kg per injection. In f, MCF-7/C6 cell labeled as “C”; Cell nucleus labeled as “N”. Experiments were repeated three times. The statistical significance was calculated via a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test.

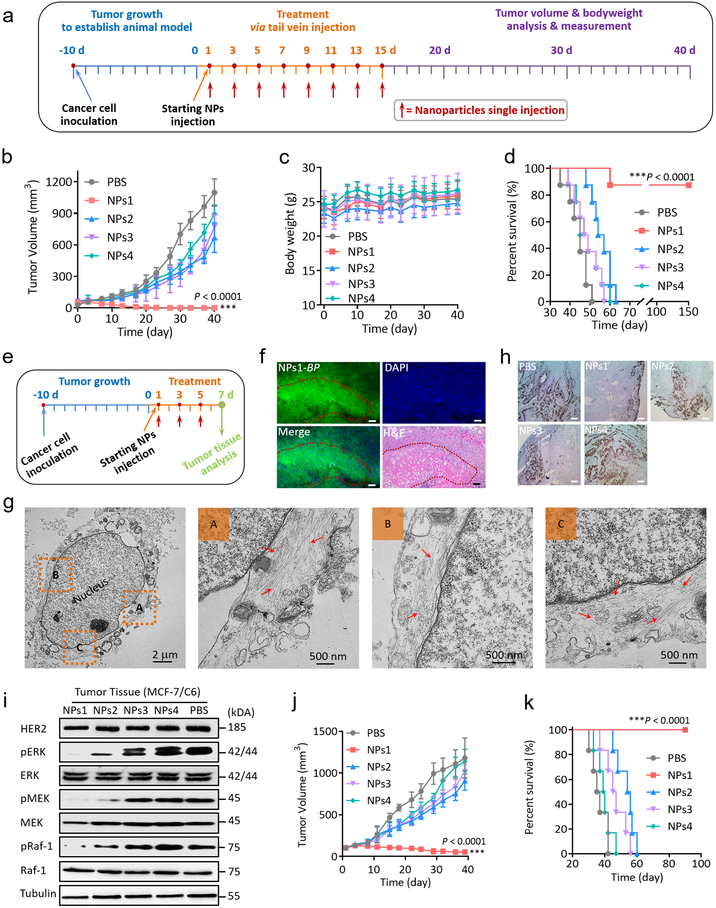

Therapeutic efficacy studies of NPs1, NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4 were performed in MCF-7/C6 HER2+ breast cancer bearing mice (Fig. 5a). NPs were injected consecutively 8 times q.o.d. via tail vein and observed continuously for 40 days. Tumour volume of NPs1 treated mice gradually shrunk and was totally eliminated after treatment without any sign of recurrence (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 31). In contrast, none of the other 3 negative control groups elicited any significant tumour response. No significant side effects were observed in this study (Fig. 5c). The survival curves correlated well with tumour growth results (Fig. 5d). In contrast, all mice in the PBS, NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4 treated groups died within 51, 63, 57, and 60 days respectively.

Fig. 5. Anti-tumour activity of fibrillar-transformable nanoparticles in Balb/c nude mice bearing HER2 positive breast tumour.

a, Schematic illustration of tumour inoculation and treatment protocol of mice. b,c, Observation of (b) the tumour inhibition effect and (c) weight change of mice in subcutaneous tumour model during the 40 days of treatment (n = 8 per group; the dose of NPs1-4 were 8 mg/kg per injection). Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. ***P < 0.001. d, Cumulative survival of different treatment groups of mice bearing MCF-7/C6 breast tumour. Seven of the eight mice receiving NPs1 treatment survived over 150 days without any sign of tumour recurrence. One of these eight mice, no longer with detectable tumour, died at around day 60 for unknown reason. e, Schematic illustration of three times treatment protocol of mice for tumour tissue analysis (n = 6 per group; the dose of NPs1-4 were 8 mg/kg per injection). f, The fluorescence distribution images in tumour tissue and H&E anti-tumour image post three times injection of NPs1 (green colour: BP of NPs1; blue colour: DAPI; scale bar in f is 100 μm). Experiments were repeated six times; a representative image is shown. g, Representative TEM images of late membrane rapture and cell death by the nanofibrillar network after injection of NPs1 three times. The red arrow shows fibrillar network. h, Ki-67 stain images of tumour tissues treated by different groups after three doses of treatment. Scale bar in h is 25 μm. Experiments were repeated six times; a representative image is shown. i, Western blot analysis of inhibition mechanism of HER2 protein and proliferation proteins in MCF-7/C6 tumour tissues treated by different groups after three doses of treatment. Experiments were repeated six times; a representative image is shown. j, Observation of the tumour inhibition effect in subcutaneous BT474 HER2 positive breast cancer models during the 40 days of treatment (n = 6 per group; the dose of NPs1-4 were 8 mg/kg per injection). Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. ***P < 0.001 compared with PBS control group. k, Cumulative survival of different treatment groups of mice bearing BT474 breast tumours. The statistical significance was calculated via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test.

To better understand the in vivo anti-tumour mechanism of NPs1, mice were sacrificed and residual tumours collected for biochemical and morphological assessment after 3 consecutive q.o.d injections of NPs1 (Fig. 5e). The degree of cell kill was found to correlate well with that of fluorescent intensity; necrosis was detected in the tumour areas with strong fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5f). To understand how the nanofibrillar network kill the HER2+ tumour cells, we performed high magnification TEM on tumours obtained from NPs1-treated mice. The TEM image of a necrotic or necroptotic cell in Fig. 5g revealed that the plasma membrane was broken, with abundant fibrillar nanostructures present inside the broken cell. Some of the nanofibrillar bundles were found adjacent to the nuclear envelope of the nucleus. No significant cell kill was detected in tumour sections obtained from mice treated with PBS, NPs2, NPs3 or NPs4 (Supplementary Fig. 32). Expression level of Ki-67 in tumour tissue was found to be markedly decrease, compared to the tumour obtained from mice treated with negative control NPs (Fig. 5h).

Tumours of NPs1 treated mice were excised for biochemical studies (Fig. 5i). Total HER2 level of tumour cells remained unchanged, but phosphorylation of Erk, Mek and Raf-1 was found to be markedly decrease, compared to the other negative control groups. Together, the data clearly demonstrated that NPs1 was highly effective in suppressing downstream proliferative and survival cell signaling at the tumour tissue level. We have also found that the cell surface fibrillary network greatly impaired the cellular uptake of hydrophilic Rhodamine 6G dye (Supplementary Fig. 33), suggesting that tumour cell death may be caused in part by impairment in uptake of vitamins and nutrients. To better investigate the universality of NPs1 as an efficacious therapeutic against HER2+ tumours, two other human HER2+ breast cancer xenograft models (BT474 and SKBR-3) were chosen for our studies. As shown in Fig. 5j and Supplementary Fig. 34a, the tumour volume of mice treated with NPs1 responded very well with almost complete elimination of BT474 tumour and completed elimination of SKBR-3 tumour by day 40, again without significant side effects (Supplementary Fig. 34b, c). The survival curves of NPs1 treated group in BT474 model, correlated well with tumour growth results (Fig. 5k).

One known side-effect of Herceptin is cardiotoxicity.31, 42 It cannot be given to patient together with cardiotoxic drug such as doxorubicin.43 We have found that NPs1 was able to undergo fibrillar-transformation, not only when interact with human HER2, but also with murine HER2 expressed on murine breast cancer cells (4T1/HER2) (Supplementary Fig. 35). Thus far, we did not observe any cardiotoxic effects in our xenograft studies with NPs1. No uptake of NPs1 in the myocardium was detected. This is not surprising as the coronary vessels are expected to be intact and the 20 nm NPs1 will not be able to reach the myocardium. The fact that NPs1 was highly efficacious against three different HER2+ tumours warrants further preclinical and clinical development of NPs1 against HER2+ breast, ovarian, gastric, and bladder cancers. There is good clinical evidence that some originally HER2 negative breast cancers can be induced to express HER2 after long-term fraction ionizing radiation.32 This further expands the patient population who may benefit from this HER2-mediated transformable nanoplatform.

When compared with current anti-HER2 therapy, NPs1 at 50 μM displayed similar inhibitory effects on downstream proliferation and survival cell signaling, to that of combination trastuzumab and pertuzumab (Supplementary Fig. 36a-c). We believe combination therapy of NPs1 with pertuzumab may be synergistic as the former has been shown to down-regulate HER2 homodimers and the latter is known to down-regulate HER2 heterodimers. Another promising combination therapy is NPs1 plus lapatinib. Our in vitro data clearly demonstrated that such drug combination could suppress HER2 dimerization, downregulate expression of downstream proliferation genes, and increase in cytotoxicity (Supplementary Fig. 36d-h). Receptor-mediated therapeutic fibrillar-transformation is not limited to HER2 binding ligands against HER2+ cancer. Our most recent data indicates that the concept is general and can be applied to other cancer cell surface receptors, such as α3β1 integrin, which is overexpressed in many epithelial cancers.44 Transformable nanoparticle decorated with LXY30 (ligand against α3β1 integrin) was found to be able to undergo in situ fibrillar transformation both in cell culture and in vivo at the tumour site.

TEM and DLS data clearly demonstrated that the transformation process from NPs1 to NFs1 did not occur in bulk all at once, but instead gradual recruitment did occur over the 24-hour period (Fig. 1d). Assuming the total volume of the nanostructure did not change significantly during the transformation process, the surface area of each nanostructure, from 20 nm micelle to 9 nm diameter fibril, is calculated to increase about 58%. Such increase in surface area will allow (1) 58 % more HER2 receptors to interact with the nanofibril structure, and (2) denser KLVFF β-sheet packing along the long axis of the nanofibril, resulting in a thermodynamically more stable structure. We believe these could be the two driving forces for nano-transformation. How this may occur at the molecular level is not clear at this time. What we did observe was that there was a slight initial decrease in fluorescence of NPs1 the first 40 minutes, followed by a gradual increase in fluorescence as transformation to NFs1 occurred over time, reflecting changes in conformation and packing of the TPMs within the nanostructure, when exposed to HER2 (Supplementary Fig. 8a).

Conclusions

In this study, we have demonstrated that NPs1 alone as a monotherapy was non-toxic and efficacious in curing a large percentage of mice bearing HER2+ breast cancer xenografts. Replacement of HER2 binding peptide with scrambled peptide without HER2 binding activity (TPM5 control group) resulted in loss of both nanofibril transformation property and anti-tumour activity, confirming the importance of ligand/receptor interaction in this in situ transformable nanotechnology (Supplementary Fig. 37). We believe the cell surface receptor-mediated transformable peptide nanoplatform has great clinical potential.

Methods

The preparation of transformable peptide monomers (TPM) 1–4.

The hydrophobic bis-pyrene unit (BP-COOH) was synthetized as the previous report by Wang’s research.45 The TPM1–4 were synthesized by standard solid phase peptide synthesis techniques. The BP-COOH as a hydrophobic part was linked to TPM1–4 chain. For TPM3 and 4, PEG1000 as a hydrophilic unit was linked to the peptide to replace HER2 ligand of TPM1 and 2. The molecular structures of BP dye and peptides were confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-off light mass spectrometry (ESI and MALDI-TOF mass spectra, Bruker Daltonics).

Self-assembly preparation and characterization of NPs.

The TPM1–4 were dissolved in DMSO to form a solution, respectively. Peptide solution (5 μL) was further diluted with DMSO (995, 795, 595, 395, 195, 95, 15, 0 μL) and mixed with deionized water (0, 200, 400, 600, 800, 900, 980, 995 μL), respectively. The UV–vis absorption and fluorescence spectra (UV-1800, Shimadzu and RF6000, Shimadzu) of different water content mixture solution were measured to validate the formation of NPs. The fresh NPs (99% water content, 20 μM) were used for the measurement as an initial state. The morphology transformation of NPs to NFs was administrated by adding HER2 extracellular receptor protein (expressed in HEK 293 cells, Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured for several hours at 37 °C. At different time point (0.5, 6 and 24 h), the solution was used for size/zeta potential (DLS, Nano ZS, Malvern), CD (JASCO Inc, Easton, MD, USA), and TEM measurement (Philips CM-120 TEM, America). TEM samples were dyed by uranyl acetate. Pyrene molecules were employed as an indicator to determine the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) of nanoparticles by comparing the fluorescence of their third and the first emissive peaks (I3/I1). First, NPs were diluted into different concentrations (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30 and 50 μM); then, 999 μL NPs of each dilution was incubated with 1 μL pyrene acetone solution (0.1 mM) at 37 °C for 2 h. The fluorescence spectra of pyrene (excitation is 335 nm) in different NPs dilutions were recorded. The fluorescence intensity ratio (I3/I1) of the third and first emissive peaks were measured for CAC calculation.

Stability of NPs1–4 in the presence of human plasma and protease.

The stability of NPs1–4 was studied in 10 % (v/v) plasma from healthy human volunteers and protease solution. The mixture was incubated at physiological body temperature (37 °C) followed by size measurements at predetermined time intervals up to 168 h. And HPLC spectra of NPs (300 μM) with protease (2 mg/mL) after 7 days were recorded.

Cell lines.

MCF-7, SKBR-3 and BT474 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The induction method of MCF-7/C6 cells was obtained from Professor Jian Jian Li’ lab (Departments of Radiation Oncology, University of California Davis). The MCF-7/C6 radioresistant cell line was survived from 25 fractionated ionizing radiations with a total dose of 50 Gy γ rays (2 Gy per fraction, five times per week). A short tandem repeat DNA profiling method was used to authenticate the cell lines and the results were compared with reference database. Moreover, no mycoplasma contamination was detected in the above cell lines.

CLSM and SEM validation of NPs structural transformation on cell surfaces.

The cells were cultured in glass bottom dishes for 12 h. NPs1–4 (50 μM) was incubated with cells in DMEM at 37 °C for 0.5, 6, 24 h or 48 h, respectively. For confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, LSM 800, ZEISS) imaging, the specimens were solidified with glutaraldehyde (4%) for 10 min, washed with PBS for 3 times and examined with a 40× or 63× immersion objective lens using a 405 nm laser. To further validate the binding of NPs1 to HER2, we used rabbit anti-HER2 (29D8) monoclonal antibody (Sigma Aldrich, USA) to detect the extracellular domain of HER2 on the surface of MCF-7/C6 cells. For SEM (Philips XL30 TMP, FEI Company, Hillsboro), the cells were solidified with glutaraldehyde (4%) overnight and then coated with gold for 2 min.

In vitro cytotoxic assay.

MCF-7/C6, MCF-7, SKBR-3 and BT474 cells were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of NPs1–4. Cells per well were seeded in the 96-well plates (n = 3) cultured with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2. DMSO solution of 1–4 were diluted by DMEM (1.5, 7.5, 15, 75, 150, 300 μM) and then added into each well to incubate with cells. After 48 h of incubation, MTS reagent was added into each well. The relative cell viabilities were measured by Micro-plate reader (SpectraMax M3, USA). Percentage of cell viability represented drug effect, and 100% means all cells survived. Cell viability was calculated using the following equation: Cell viability (%) = (OD490nm of treatment/OD490nm of blank control) × 100%.

Western blot analysis.

MCF-7/C6 cells were treated by different conditions and then collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min and lysed with a 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 containing lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) with protease inhibitor. Total cellular proteins were estimated using a BCA kit (Applygen). Each sample (50 μg of protein) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking for 2 h at room temperature with 5% (wt/v) nonfat dry milk in blotto solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20), the membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Then the membranes were washed (3×5 min) with TBST solution and incubated with second antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Signals were visualized by chemiluminescence on a Typhoon Trio Variable Mode Imager. Band density was calculated using NIH Image J software.

HER2 dimer analysis used by western blot were described as before.41 Briefly, HER2 high expression MCF-7/C6 cells were treated with NPs1 or other drugs as indicated protocols and then lysed in 1.0% Triton X-100 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, and protease inhibitors cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 4 °C. For carrying out cross-linking reactions, the lysis supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes. 0.2% glutaraldehyde was added to the lysis supernatant with a final concentration 0.01% for 10 minutes at 37 °C. The reactions were terminated by adding 1 M Tris buffer to a final concentration of 50 mM Tris·Cl (pH 8.0). Samples were then separated by 6% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HER2 or other antibodies as indicated.

Animal maintenance.

All animal experiments were in accordance with protocols No.19724, which was approved by the Animal Use and Care Administrative Advisory Committee at the University of California, Davis. Experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and ethical regulations. The jugular vein of male Sprague-Dawley rats was cannulated, and a catheter was implanted for intravenous injection and blood collection (Harland, Indianapolis, IN, USA). NPs (8 mg/kg) were i.v. administrated into rat (n = 3). Whole blood samples (~100 μL) were collected via jugular vein catheter before dosing and at predetermined time points post-injection. The fluorescence of the samples for the standard curve and each experimental group was measured upon the dilution of blood serum solution in access amount of PBS (Serum:PBS = 20:80, vol%). Female Balb/c nude mice were 6–8 weeks of age (weight 22 ± 2 g), which were purchased from Envigo. MCF-7/C6 cells (5×106 cells per mouse) were inoculated subcutaneously into the flank of each female Balb/c nude mice, respectively. After around 10 days, NPs1–4 (8 mg/kg) were injected via the tail vein and ex vivo images of tumour, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, intestine, muscle, skin were collected at 10, 24, 48, 72, 168 h post injection. The images were collected by in vivo fluorescence imaging system (Carestream In-Vivo Imaging System FXPRO, USA). Tumour and Main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and brain) were collected and solidified with glutaraldehyde (4%) at 72 h post injection of NPs for TEM imaging.

In vivo therapeutic effect.

Balb/c nude mice with MCF-7/C6 cells (5 × 106 cells per mouse) tumours inoculated subcutaneously into the flank were used in our experiments. The mice were randomly divided into five groups at 10 days post-tumour inoculation. Each of them treated with PBS, NPs1, NPs2, NPs3 and NPs4 every 48 h via i.v. administration. During the process of the treatment (40 days), the tumour volumes and body weight were measured twice per week. For Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining test and Ki-67 test, MCF-7/C6 tumour-bearing mice were sacrificed after three times treatment and tumour tissues were collected. In parallel, the therapeutic effect of NPs1 was verified in the mice bearing SKBR-3 or BT474 tumours with similar experimental method mentioned above. For BT474 model, the mice were pre-implanted with a 17-Beta-Estradiol pellet.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). The comparison between groups was analyzed with the student’s t-test (two-tailed). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple-group analysis. The level of significance was defined at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data generated or analysed during this study are available in this published article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI Grants (R01CA115483, U01CA198880, R01CA199668, and R01CA232845), NIH/NIBIB Grant (R01EB012569), NIH/NICHD Grant (R01HD086195) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (51573101).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): K.S.L., L.Z., D.J. and L.W. are the co-inventors of a pending patent on the fibrillar transformable nanoparticles. K.S.L. is the founding scientist of LamnoTherapeutics Inc. which plans to develop the nanotherapeutics described in the manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permission information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to K.S.L or L.W.

Reference

- 1.Slamon DJ et al. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 235, 177–182 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arteaga CL et al. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: current status and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 9, 16–32 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gravalos C & Jimeno A HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann. Oncol 19, 1523–1529 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferte C, Andre F & Soria JC Molecular circuits of solid tumours: prognostic and predictive tools for bedside use. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 7, 367–380 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roukos DH & Briasoulis E Individualized preventive and therapeutic management of hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol 4, 578–590 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian H et al. Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 346, 645–652 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jänne PA & Johnson BE Effect of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase domain mutations on the outcome of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res 12, 4416s–4420s (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson KM Structure-based view of epidermal growth factor receptor regulation. Annu. Rev. Biophys 37, 353–373 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Saenz A & Moasser MM Targeting HER2 by combination therapies. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 808–811 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Gureasko J, Shen K, Cole PA & Kuriyan J An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell 125, 1137–1149 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA & Hynes NE The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. Embo. J 19, 3159–3167 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gschwind A, Fischer OM & Ullrich A The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 361–370 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin Y & Brangwynne CP Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357, eaaf4382 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Wang Y, Huang G & Gao J Cooperativity principles in self-assembled nanomedicine. Chem. Rev 118, 5359–5391 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattia E & Otto S Supramolecular systems chemistry. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, 111–119 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webber MJ, Appel EA, Meijer E & Langer R Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat. Mater 15, 13 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haburcak R, Shi J, Du X, Yuan D & Xu B Ligand-receptor interaction modulates the energy landscape of enzyme-instructed self-assembly of small molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 15397–15404 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng Z, Wang H, Chen X & Xu B Self-assembling ability determines the activity of enzyme-instructed self-assembly for inhibiting cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 15377–15384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J et al. Selection of secondary structures of heterotypic supramolecular peptide assemblies by an enzymatic reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 11716–11721 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He PP, Li XD, Wang L & Wang H Bispyrene-based self-assembled nanomaterials: in vivo self-assembly, transformation, and biomedical effects. Acc. Chem. Res 52, 367–378 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi GB, Gao YJ, Wang L & Wang H Self-assembled peptide-based nanomaterials for biomedical imaging and therapy. Adv. Mater 30, 1703444 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang PP et al. Host materials transformable in tumour microenvironment for homing theranostics. Adv. Mater 29, 1605869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan J et al. Role of CD40 ligand in amyloidosis in transgenic Alzheimer’s mice. Nat. Neurosci 5, 1288–1293 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hock C et al. Generation of antibodies specific for β-amyloid by vaccination of patients with Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med 8, 1270 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park BW et al. Rationally designed anti-HER2/neu peptide mimetic disables P185HER2/neu tyrosine kinases in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol 18, 194–198 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berezov A, Zhang HT, Greene MI & Murali R Disabling erbB receptors with rationally designed exocyclic mimetics of antibodies: structure-function analysis. J. Med. Chem 44, 2565–2574 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitagawa K & Abdulle R Deoxycholate-based method to screen phage display clones for uninterrupted open reading frames. Mol. Cell 4, 21–33 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser TE, Wang H, Stepanenko V & Würthner F Supramolecular construction of fluorescent J-aggregates based on hydrogen-bonded perylene dyes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 119, 5637–5640 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu X-X et al. Transformable nanomaterials as an artificial extracellular matrix for inhibiting tumour invasion and metastasis. ACS Nano 11, 4086–4096 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korevaar PA et al. Pathway complexity in supramolecular polymerization. Nature 481, 492–496 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zagar TM, Cardinale DM & Marks LB Breast cancer therapy-associated cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 13, 172–184 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duru N et al. HER2-associated radioresistance of breast cancer stem cells isolated from HER2-negative breast cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res 18, 6634–6647 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams SR et al. Anti-tubulin drugs conjugated to anti-ErbB antibodies selectively radiosensitize. Nat. Commun 7, 13019 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang L et al. Proteomics discovery of radioresistant cancer biomarkers for radiotherapy. Cancer Lett. 369, 289–297 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duru N et al. HER2-associated radioresistance of breast cancer stem cells isolated from HER2-negative breast cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res 18, 6634–6647 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuang Y et al. Pericellular hydrogel/nanonets inhibit cancer cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 53, 8104–8107 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pires RA et al. Controlling cancer cell fate using localized biocatalytic self-assembly of an aromatic carbohydrate amphiphile. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 576–579 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeena MT et al. Mitochondria localization induced self-assembly of peptide amphiphiles for cellular dysfunction. Nat. Commun 8, 26 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang D et al. In situ formation of nanofibers from purpurin18-peptide conjugates and the assembly induced retention effect in tumour sites. Adv. Mater 27, 6125–6130 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka A et al. Cancer cell death induced by the intracellular self-assembly of an enzyme-responsive supramolecular gelator. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 770–775 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H-J et al. JMJD5 regulates PKM2 nuclear translocation and reprograms HIF-1α-mediated glucose metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 111, 279–284 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mariani G, Fasolo A, De Benedictis E & Gianni L Trastuzumab as adjuvant systemic therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol 6, 93–104 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popat S & Smith IE Therapy insight: anthracyclines and trastuzumab-the optimal management of cardiotoxic side effects. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 5, 324 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao W et al. Discovery and characterization of a high-affinity and high-specificity peptide ligand LXY30 for in vivo targeting of α3 integrin-expressing human tumours. Ejnmmi. Res 6, 18 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiao S-L et al. Thermo-controlled in situ phase transition of polymer-peptides on cell durfaces for high-performance proliferative inhibition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 17016–17022 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data generated or analysed during this study are available in this published article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding author upon request.