Abstract

Background:

Donor nerve myelinated axon counts correlate with functional outcomes in reanimation procedures, however there exists no reliable means for their intraoperative quantification. Herein, we report a novel protocol for rapid quantification of myelinated axons from frozen sections, and demonstrate its applicability to surgical practice.

Methods:

The impact of various fixation and FluoroMyelin Red™ staining strategies on resolved myelin sheath morphology from cryosections of rat and rabbit femoral and sciatic nerves was assessed. A protocol comprising fresh cryosection and rapid staining was developed, and histomorphometric results compared against conventional osmium post-fixed, resin-embedded, toluidine blue-stained sections of rat sciatic nerve. The rapid protocol was applied for intraoperative quantification of donor nerve myelinated axon count in a cross-facial nerve grafting procedure.

Results:

Resolution of myelinated axon morphology suitable for counting was realized within ten minutes of tissue harvest. Though mean myelinated axon diameter appeared larger using the rapid fresh-frozen as compared to conventional nerve processing techniques (mean ± standard deviation; rapid, 9.25 ± 0.62; conventional, 6.05 ± 0.71; p < 0.001), no difference in axon counts was observed on high power fields (rapid, 429.42 ± 49.32; conventional, 460.32 ± 69.96; p = 0.277). Whole nerve myelinated axon counts using the rapid protocol herein (8435.12 ± 1329.72) were similar to prior reports employing conventional osmium processing of rat sciatic nerve.

Conclusions:

A rapid protocol for quantification of myelinated axon counts from peripheral nerves using widely available equipment and techniques has been described, rendering possible intraoperative assessment of donor nerve suitability for reanimation.

Keywords: Peripheral Nerves; Nerve Transfer; Histology; Fluorescent Dyes; Outcome Assessment; Surgical Flaps; Grafts, Tissue

Introduction

Strategies for smile reanimation in the setting of facial palsy include nerve or functional muscle transfers.1–3 The choice of donor nerve for reanimation is of utmost importance, where the risk of sub-optimal neurotization of muscle that may occur where cross-facial nerve grafts are used must be weighed against the absence of spontaneous emotional expression inherent to the use of other donor nerves, such as the nerve-to-masseter muscle. Though cross-facial neurotization of free functional muscle may restore emotionality and synchronicity to reanimated smile, failure to attain meaningful excursion is not uncommon,4 and symmetry of full-effort smile is uncommonly achieved.5–7 In contrast, transfer of the nerve-to-masseter muscle to native facial musculature or free muscle for smile reanimation achieves powerful excursion with low failure rates.8,9 Donor nerve axonal load and target proximity are critical factors in functional outcomes of reanimation procedures.10–15 It is believed that the proximity and increased number of myelinated axons afforded by the nerve-to-masseter as compared to a cross-facial donor nerve explains the mean differences in smile excursion observed between the techniques. The descending branch of the nerve-to-masseter comprises over 1500 axons,11,16 while a typical donor branch for cross-facial nerve grafting carries substantially fewer.14,17 Terzis et al first noted a correlation between cross-facial donor nerve axonal load and ultimate smile excursion, with meaningful smile achieved in 70% of cases where myelinated axon counts exceeded 900.14 Hembd et al demonstrated that facial nerve branches lateral as opposed to medial to the anterior border of the parotid gland in the zygomaticobuccal region more often carry 900 or more myelinated axons.17 Selection of a large-caliber facial nerve donor branch to enhance the likelihood of achieving sufficient commissure excursion must be carefully weighed against the risk of weakening donor-side smile, and the risk of including large numbers of axons controlling expressions other than smile, such as eye closure. A means for rapid assessment of axon counts would permit intraoperative confirmation of sufficient number of myelinated axons within a cross-facial donor nerve branch, to maximize the chances of adequate smile reanimation while minimizing the risk of donor-side morbidity. Herein, we describe a robust and cost-effective staining protocol for rapid assessment of myelinated axon counts from peripheral nerve.

Materials and Methods

Part 1: Rapid Protocol Development

Sciatic and femoral nerves from adult Dutch-Belted rabbits and Wistar-Hannover rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were utilized for testing of various fixation and staining parameters (Table 1). Rapid nerve harvest was carried out immediately after euthanization in strict accordance with Massachusetts Eye and Ear Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee protocols. No prior nerve intervention had been performed. Nerves were cut into 10 mm segments, and subjected either to no fixation (placed in 0.01M phosphate buffered saline [PBS]), or fixation using 10% neutral-buffered formalin [NBF] or 0.01M phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde [PFA]) for 24 hours at 4 °C, or for 10 minutes at room temperature or on ice. Following brief rinsing in PBS, tissues were axially aligned in a cryomold using optimal cutting temperature compound (23-730-571, Fisher Healthcare), flash-freezed in 2-methybutane (M32631, SIGMA ALDRICH, US), and transported on liquid nitrogen for cryosectioning at 1 μm (Leica 100 Cryostat; Leica Microsystems). Sections were mounted on silane-coated slides, briefly rinsed with PBS, and immediately stained with FluoroMyelin Red™ [FMR] (F34652, Invitrogen) at PBS dilutions of 1:300 or 1:50 for 20 min or 1 min at room temperature or 37 °C, followed by three washes with 0.01M PBS lasting 10 minutes or 10 seconds each. Mounting medium (Mount Liquid Antifade, Abberior GmbH) and coverslips were placed. Sections were then imaged using a wide-field fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager A.2, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), using a 40X/1.3 objective lens (EC Plan-Neofluar, Carl Zeiss), and a broadband light source (X-Cite 120 LED, Excelitas Technologies Corp, Waltham, MA, USA). FMR stained samples were imaged using a 550/25 nm bandpass excitation filter, a 570 nm beam splitter, and a 605/70 nm emission filter, and digitized using a cooled-CCD monochrome camera (Axiocam 503 mono, Carl Zeiss). Images were acquired using ZEN 2 Blue software (Carl Zeiss), and independently assessed by two authors (W.W. and N.J.) for quality of resolved myelinated axon morphology. A time-optimized protocol was then developed (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Tested fixation and staining parameters.

| Fixative/transport | Fixation time | Fixation/transport temperature | Stain dilution | Stain time | Rinse time | Stain temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% NBF | 24 h | 4 °C | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT |

| 10 m | RT | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT | |

| 10 m | On ice | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:300 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | 37 °C | |

| 4% PFA (in 0.01 M PBS) | 24 h | 4 °C | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT |

| 10 m | RT | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT | |

| 10 m | On ice | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:300 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| 10 m | RT | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | 37 °C | |

| None (0.01 M PBS) | - | On ice | 1:300 | 20 m | 30 m | RT |

| - | On ice | 1:300 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| - | On ice | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | RT | |

| - | On ice | 1:50 | 1 m | 1 m | 37 °C |

NBF: Neutral-buffered formalin, PFA: paraformaldehyde, PBS: phosphate-buffered saline, m: minutes, h: hours, RT: room temperature

Figure 1. Protocol for rapid resolution of myelinated axons from cross-sections of peripheral nerve.

Specimens may be transported from the operating room (OR) in 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) on ice for fresh cyrosection, or cryosectioned following brief fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.01 M PBS.

Part 2: Comparison against Conventional Processing

Sciatic nerves from Wistar-Hannover rats were again freshly harvested for processing using the newly-developed rapid protocol (N = 12) or conventional means as controls (N = 12). Controls specimens were placed immediately in 0.2 M cacodylate-buffered 2% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 24 hours, then transferred to 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer until post-fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide in phosphate buffer (2 hours at 4°C), followed by staining with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (2 h at 4°C). Specimens were serially dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in epoxy resin, axially sectioned at 1μm using a diamond-blade ultra-microtome, and counter-stained with toluidine blue, prior to mounting on glass slides and cover-slipping with traditional mounting media. Controls sections were imaged brightfield, and digitized using a cooled-CCD color camera (Axiocam 503 color, Carl Zeiss).

Myelinated axon histomorphometry was then compared between groups using commercial image-analysis software (Bitplane Imaris 9.2, Oxford Instruments, Zurich, Switzerland). Analysis was performed on single high-power fields (using 40X objective) of nerve cross-sections for comparison of this protocol against conventional osmium post-fixation resin-embedding, and on entire cross-sections of nerve for comparison against previously reported rat sciatic nerve axon counts and for clinical application (Part 3). Acquisition of entire cross-sectional areas of nerve cryosections was achieved through image stitching of high-power fields in open-source software (Fiji ImageJ18–20). Digitized images were 8-bit down-sampled to grayscale, inverted, and thresholded by background subtraction. Myelinated rings were surface mapped, and numbers and diameters automatically quantified. Data was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and groups compared using the independent samples t-test in commercial software (IBM SPSS Statistics v22.0, Armonk, NY, USA), with α set to 0.05.

Part 3: Application to Clinical Practice

Written informed consent was obtained following Massachusetts Eye and Ear Internal Review Board approval. In a first-stage cross-facial nerve grafting procedure for planned two-stage free gracilis transfer for smile reanimation, a promising healthy-side lower zygomatic branch that provided an excellent smile vector when stimulated was identified near the anterior border of the parotid gland. After redundancy confirmation by identification of other branches providing smile, the donor nerve was freshly transected and a 3 mm segment was placed in 0.01 M PBS-soaked gauze on ice, processed using the rapid protocol described herein (Fig. 1), and axon counts quantified in commercial software from digitized images as above.

Results

Part 1: Rapid Protocol Development

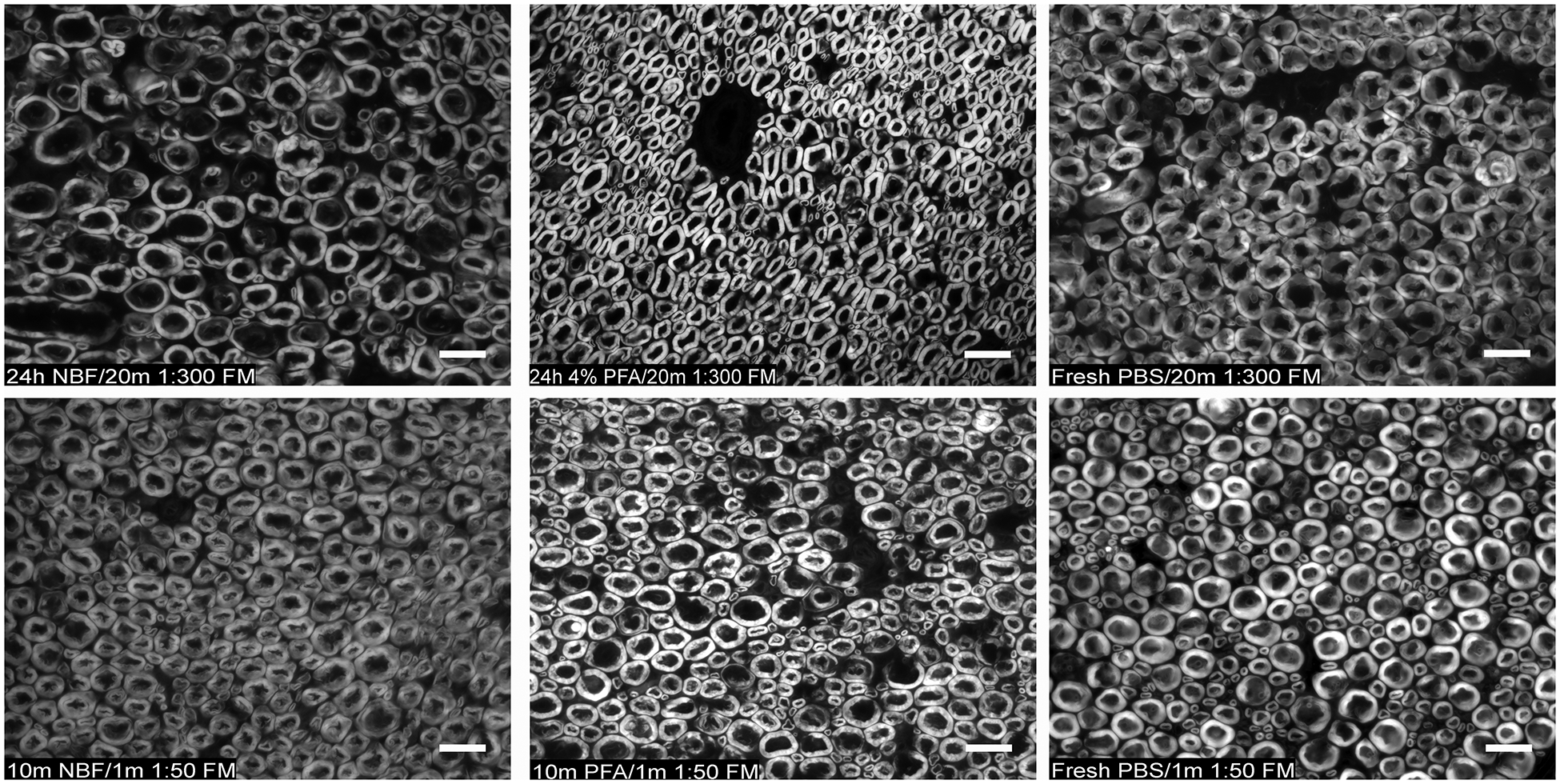

Staining of myelinated axon sheaths was readily observed for all fixation and staining protocols. Fixation with PFA resulted in improved myelinated ring morphology as compared to non-fixed sections for fixation times as short as ten minutes (Fig 2). Myelinated rings appeared more edematous and of slightly larger diameter on fresh-frozen section compared with fixed sections, however they remained readily identifiable (Fig. 2). Fixation with NBF demonstrated worse morphology as compared to fixation with PFA (Fig. 2). Fixation at room temperature with NBF or PFA yielded slightly improved morphology compared with fixation on ice for short fixation times. Consistent morphological outcomes for these fixation methods were observed in rat femoral nerve (~1 mm diameter), rat sciatic nerve (~1.5–2mm diameter), and rabbit sciatic nerve (~3 mm diameter). A staining time of one minute with 1:50 dilution of FMR followed by three 10 second PBS washes resulted in equivocal signal as that obtained using the recommended 1:300 dilution of FMR for 20 minutes followed by three 10 minute washes, without noted difference in signal-to-background contrast (Fig. 2). A minor improvement in signal strength was noted with incubation at 37 °C during FMR staining.

Figure 2. Comparison of various fixation and FluoroMyelin Red™ staining protocols on imaging of rat sciatic nerve myelinated axons.

Specimens were immediately placed in fixative or 0.01M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) following harvest, prior to axial cryosection at 1 μm. Tow row: FluoroMyelin Red™ dilution of 1:300 with 20 minute stain time. A: Specimen fixed with neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for 24 hours. B: Specimen fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.01 M PBS for 24 hours. C: No fixation (fresh frozen sectioned). Bottom row: FluoroMyelin Red™ dilution of 1:50 with 1 minute stain time. D: Specimen fixed with NBF for 10 min. E: Specimen fixed 4% PFA in 0.01 M PBS for 10 min. F: No fixation (fresh frozen sectioned). (Widefield epifluorescent microscopy, 40x/1.3 NA oil objective, scale bar = 20um)

Part 2: Comparison against Conventional Processing

Though mean myelinated axon diameter appeared larger using the rapid fresh-frozen as compared to conventional nerve processing techniques (mean ± standard deviation; rapid, 9.25 ± 0.62; conventional, 6.05 ± 0.71; p < 0.001), no difference in axon counts was observed on high power fields (rapid, 429.42 ± 49.32; conventional, 460.32 ± 69.96; p = 0.277) (Fig. 3). Automated counts from whole cross-sections of rat sciatic nerve obtained by stitching of high-power fields demonstrated a mean of 8435.12 ± 1329.72 myelinated axons. This figure is similar to prior reports that employed conventional osmium tetroxide processing, estimating the rat sciatic nerve to comprise approximately 8000 myelinated axons.21,22

Figure 3. Comparison of conventional nerve processing versus the herein reported rapid protocol on automated histomorphometry of rat sciatic nerve.

Top row: Osmium post-fixed, resin embedded, 1 μm sectioned, and toluidine blue stained specimen. Bottom row: Fresh, optimal cutting temperature compound embedded, 1 μm sectioned, and FluoroMyelin Red™ stained (1:50 for 1 min) specimen. A, D: Original images. B, D: Image pre-processing by 8-bit grayscale down-sampling, inversion, and background subtraction. C, Automated surface mapping of myelinated axons; color map represents outer diameter of mapped surfaces.

Part 3: Application to Clinical Practice

Adequate morphology of myelinated axons suitable for automated axon counting was readily obtained using the rapid fresh-frozen staining protocol described, with confirmation the donor facial nerve branch comprised in excess of 900 axons (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Rapid intraoperative quantification of myelinated axon count in zygomatic donor branch of human facial nerve.

The patient was undergoing first-stage cross-facial nerve grafting procedure for planned free gracilis transfer for smile reanimation. A: Original wide-field epifluorescence image of fresh 1 μm cryosection stained with 1:50 FluoroMyelin Red™ for one minute. B: Automated surface mapping and quantification of myelinated axons; color map represents outer diameter of myelinated axons.

Discussion

Donor nerve axon load correlates with functional outcomes when the number of myelinated axon in the donor nerve is less than the original input to the muscle.12,13 At present, intraoperative selection of donor nerves is based primarily on surgeon experience and anatomical landmarks known to correlate with axon counts. A means for rapid and reliable intraoperative quantification of axon counts would provide actionable information to the microsurgeon in the operating theatre. For example, such a technique could be employed to confirm sufficient number of myelinated axons in a chosen facial nerve donor branch in cross-facial nerve grafting procedures; where an insufficient number of axons is noted, an additional neighboring donor branch could be immediately selected for additional coaptation to the graft to boost axonal load. This protocol could also be employed to guide nerve-transfer decisions; for example, to assess the suitability of nerve-to-masseter transfer to distal facial nerve branches for volitional smile reanimation where partial trigeminal motor function exists. Trigeminal motor dysfunction concurrent with facial palsy may occur following extirpation of large cerebellopontine angle tumors including vestibular schwannomas.

Conventional nerve staining techniques are time and resource intensive, rendering them unsuitable for intraoperative use. Osmium tetroxide and silver staining protocols necessitate fixation and buffering steps to achieve reliable results, involve toxic and expensive reagents, and require hours to days to complete.23,24 Though immunostaining approaches are feasible with frozen sections, protocols require several hours to days to complete.

In 2004, the non-toxic, lipophilic, water-soluable, and highly myelin-specific dye FMR was introduced.25,26 This fluorescent dye may be applied directly to neural tissue sections, with minimal pre-processing steps. It may be used in vivo cell culture, or applied directly to sections of frozen or fixed tissue.27 Since its commercialization, reported use of the dye in the literature has been limited to laboratory studies, and no prior study has employed the dye for quantification of myelinated axons in peripheral nerve cross-sections. Current FMR staining protocols recommend 20 minutes of staining using 1:300 dilution, and 30 minutes of subsequent washing.28 Herein, we developed an expedited protocol that readies peripheral nerve for myelinated axon counting using a conventional wide-field epifluorescence microscope within ten minutes of biopsy. This fresh-frozen protocol avoids toxic fixation steps, and is ideal in facilities where transport times to the cryosection facility are short. Alternatively, where transport times are longer, fixation with 4% PFA for periods as short as ten minutes may be used to obtain similar or slightly improved resolution of myelinated axon morphology.

The impact of fixative composition and processing temperature warrant discussion. The enhanced axonal morphology seen with the use of 4% PFA over 10% NBF may be attributable to the presence of methanol in the latter. Methanol is a lipid solvent, which negatively impacts lipid staining outcomes. The improved morphology seen with fixation at room temperature as opposed to on ice is likely the result of faster penetration of fixative into tissue at higher temperatures, with the added benefit of simplification of transport conditions. While stronger FMR signal was noted when specimens were stained at 37 °C, adequate staining was obtained for room temperature conditions, simplifying the protocol. A rapid three wash technique for these thin sections resulted in equivalent staining outcomes as compared to the recommended 30 min washing steps. Monsma et al demonstrated similar findings for live cell fluorescent imaging, whereby stained cultures could be imaged without rinsing, as FMR demonstrates weak fluorescence in aqueous solution when not bound to lipids.25

Economic Considerations

The rapid protocol described herein requires only basic supplies, access to a cryostat, and a wide-field fluorescence microscope with a standard Cy3 (red) filter cube for rapid visualization of myelinated axons. As a result, this protocol may be readily implemented across most centers for intraoperative and research applications. The fresh-frozen approach uses no toxic chemicals, and staining may be performed outside of a fume hood. The estimated material and labor costs for slide preparation assuming three slides per specimen using this protocol is approximately $15, calculated as follows: 10 ml paraformaldehyde ($ 0.06), 100 ml 2-methylbutane ($ 4.13), 300 ml liquid nitrogen ($ 0.69), 1 ml OCT ($ 0.11), one cryomold ($ 0.31), one cyrotome blade ($ 2.47), three silane-coated glass slides ($ 1.38), three coverslips ($ 0.47), 300 μL diluted FMR (dilution: 1:50, $ 1.28), 30 μl mounting medium ($ 0.10), 10 ml PBS ($ 0.04), technician time (10 minutes, $4.17, assuming $ 25 per hour including fringe). For quantification, a microscope camera and appropriate software are also required.

Limitations

This approach has several limitations. Axons of fresh-frozen sections stained with FMR appeared more edematous and of slightly larger caliber than those fixed prior to staining. Such morphological differences are likely the result of tissue shrinkage that occurs with fixation. A further limitation of this rapid protocol is its current dependence on commercial software for automated histomorphometry. Future work will seek to develop rapid axon counting from FMR stained cross-sections of peripheral nerve in open-access software packages, such as ImageJ. Unfixed fresh-frozen sections will degrade quickly if stored at room temperature; brief post-sectioning fixation of mounted specimens in 4% PFA prior to staining could be employed to prolong storage life.

Herein, normal nerves were imaged in rapid fashion; future work will seek to discern whether this rapid protocol may be employed for quantification of neural regeneration in animal studies and clinical settings, such as rapid quantification of myelinated axon counts in tips of cross-facial nerve grafts used for smile reanimation. Quantification of axonal load in tips of cross-facial nerve grafts at a standardized time point could then be correlated with long-term functional outcomes to determine the threshold number of myelinated fibers in the distal tip required for sufficient smile excursion. Subsequently, the rapid protocol could be employed to guide intraoperative decisions regarding single- (i.e. cross-facial nerve graft alone) versus dual-innervation (e.g., cross-facial nerve graft in addition to nerve-to-masseter) strategies during second-stage free muscle transfer procedures.

Conclusion

A non-toxic and cost-effective protocol for rapid assessment of myelinated axon counts from peripheral nerves has been described. This approach may be employed to inform intraoperative decisions regarding donor nerve selection in reanimation procedures.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01NS071067 and by a generous donation from the Berthiaume Family. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Berthiaume Family. The authors thank Eleftherios Paschalis Ilios, Ph.D., for kindly donating rabbit sciatic nerves, and Martin Selig for assistance with conventional processing of nerve specimens.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure and products: None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Harii K, Ohmori K, Torii S. Free gracilis muscle transplantation, with microneurovascular anastomoses for the treatment of facial paralysis. A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57(2):133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien BM, Franklin JD, Morrison WA. Cross-facial nerve grafts and microneurovascular free muscle transfer for long established facial palsy. Br J Plast Surg. 1980;33(2):202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klebuc M Masseter–to-Facial Nerve Transfer: A new technique for facial reanimation. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22(03):A101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenhardt SU, Eisenhardt NA, Thiele JR, Stark GB, Bannasch H. Salvage procedures after failed facial reanimation surgery using the masseteric nerve as the motor nerve for free functional gracilis muscle transfer. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2014;16(5):359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae YC, Zuker RM, Manktelow RT, Wade S. A comparison of commissure excursion following gracilis muscle transplantation for facial paralysis using a cross-face nerve graft versus the motor nerve to the masseter nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2407–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takushima A, Harii K, Asato H, Kurita M, Shiraishi T. Fifteen-year survey of one-stage latissimus dorsi muscle transfer for treatment of longstanding facial paralysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar PA, Hassan KM. Cross-face nerve graft with free-muscle transfer for reanimation of the paralyzed face: a comparative study of the single-stage and two-stage procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(2):451–462; discussion 463–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Natghian H, Fransen J, Rozen SM, Rodriguez-Lorenzo A. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of smile excursion in facial reanimation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 1- versus 2-stage procedures. Plastic and reconstructive surgery Global open. 2017;5(12):e1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klebuc MJ. Facial reanimation using the masseter-to-facial nerve transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):1909–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schreiber JJ, Byun DJ, Khair MM, Rosenblatt L, Lee SK, Wolfe SW. Optimal axon counts for brachial plexus nerve transfers to restore elbow flexion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(1):135e–141e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borschel GH, Kawamura DH, Kasukurthi R, Hunter DA, Zuker RM, Woo AS. The motor nerve to the masseter muscle: an anatomic and histomorphometric study to facilitate its use in facial reanimation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(3):363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacQuillan AH, Grobbelaar AO. Functional muscle transfer and the variance of reinnervating axonal load: part I. The facial nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(5):1570–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacQuillan AH, Grobbelaar AO. Functional muscle transfer and the variance of reinnervating axonal load: part II. Peripheral nerves. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(5):1708–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terzis JK, Wang W, Zhao Y. Effect of axonal load on the functional and aesthetic outcomes of the cross-facial nerve graft procedure for facial reanimation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(5):1499–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder-Warwick AK, Fattah AY, Zive L, Halliday W, Borschel GH, Zuker RM. The degree of facial movement following microvascular muscle transfer in pediatric facial reanimation depends on donor motor nerve axonal density. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):370e–381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombs CJ, Ek EW, Wu T, Cleland H, Leung MK. Masseteric-facial nerve coaptation--an alternative technique for facial nerve reinnervation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(12):1580–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hembd A, Nagarkar PA, Saba S, et al. Facial nerve axonal analysis and anatomic localization in donor nerve: Optimizing axonal load for cross facial nerve grafting in facial reanimation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods. 2012;9(7):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1463–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenq CB, Chung K, Coggeshall RE. Postnatal loss of axons in normal rat sciatic nerve. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1986;244(4):445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmalbruch H Fiber composition of the rat sciatic nerve. The Anatomical record. 1986;215(1):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake PL, Hazelwood KJ. Exposure-related health effects of silver and silver compounds: A review. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 2005;49(7):575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scipio FD, Raimondo S, Tos P, Geuna S. A simple protocol for paraffin-embedded myelin sheath staining with osmium tetroxide for light microscope observation. Microscopy research and technique. 2008;71(7):497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monsma PC, Brown A. FluoroMyelin™ Red is a bright, photostable and non-toxic fluorescent stain for live imaging of myelin. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2012;209(2):344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilgore J, Janes MS. A novel myelin labeling technique for fluorescence microscopy of brain sections Neuroscience Meeting; Oct. 23–27, 2004, 2004; San Dieg, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watkins TA, Emery B, Mulinyawe S, Barres BA. Distinct stages of myelination regulated by gamma-secretase and astrocytes in a rapidly myelinating CNS coculture system. Neuron. 2008;60(4):555–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FluoroMyelin™ fluorescent myelin stains. In. Product Information. Willow Creek Road, Eugene, OR Molecular Probes ThermoFisher Scientific; 2005. [Google Scholar]