Abstract

Introduction:

The pervasive use of technology has raised concerns about its association with adolescent mental health, including internalizing symptoms. Existing studies have not always had consistent findings. Longitudinal research with diverse subgroups is needed.

Methods:

This study examines the relationship between screen-based sedentary (SBS) behaviors and internalizing symptoms among 370 Hispanic adolescents living in Miami, Florida- United States, who were followed for 2 ½ years and assessed at baseline, 6, 18 and 30 months post-baseline between the years 2010 and 2014. Approximately 48% were girls, and 44% were foreign-born, most of these youth being from Cuba. Mean age at baseline was 13.4 years, while at the last time-point it was 15.9 years.

Results:

Findings show that girls had higher internalizing symptoms and different patterns of screen use compared to boys, including higher phone, email, and text use. SBS behaviors and internalizing symptoms cooccurred at each time-point, and their trajectories were significantly related (r =0.45, p < .001). Cross-lagged panel analyses found that SBS behaviors were not associated with subsequent internalizing symptoms. Among girls, however, internalizing symptoms were associated with subsequent SBS behaviors during later adolescence, with internalizing symptoms at the 18-month assessment (almost 15 years old) associated with subsequent SBS behaviors at the 30-month assessment (almost 16 years old; β = 0.20, p < .01).

Conclusions:

Continued research and monitoring of internalizing symptoms and screen use among adolescents is important, especially among girls. This includes assessments that capture quantity, context, and content of screen time.

Keywords: Screen use, Sedentary behaviors, Internalizing symptoms, Hispanic, Adolescent girls

Adolescent internalizing symptoms, or depression and anxiety symptoms, can cause significant distress, impair social and academic functioning, and intensify risk for later mental health problems (Bor, Dean, Najman, & Hayatbaksh, 2014; Hughes & Gullone, 2008; Kessler et al., 2007; Rueter, Scaramella, Wallace, & Conger, 1999; Wesselhoeft, Sorensen, Heiervang, & Bilenberg, 2013). Certain subgroups of youth show disproportionate risk for elevated internalizing symptoms. For instance, adolescent girls show significantly higher rates of internalizing symptoms and depressive disorders compared to boys (Garber, 2006; Kessler et al., 2012). Several studies have found also higher rates of internalizing symptoms among ethnic minority adolescents in the United States (U.S.) (Anderson & Mayes, 2010). According to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance study, compared to 38% of white adolescent girls,47% of Hispanic girls endorsed feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for at least 2 weeks in the past year, such that it interfered with usual activities (Kann et al., 2016). Youth who experience socioeconomic disadvantage, for example poverty or limited parental education, are also at elevated risk of internalizing symptoms, depressive disorders and poorer mental health (Reiss, 2013; Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, 2012).

The search for determinants that contribute to youth internalizing symptoms is an important way to identify modifiable targets for preventive interventions (Garber, 2006). Growing research has focused on screen-based sedentary behaviors (SBS) as possible influences on adolescent mental health, concerns exacerbated by the pervasive availability and utilization of technology among young people (Costigan, Barnett, Plotnikoff, & Lubans, 2013; Hoare, Milton, Foster, & Allender, 2016; Liu, Wu, & Yao, 2016; Madden et al., 2013; Suchert, Hanewinkel & Isensee, & Iäuft Study Group, 2015). Sedentary behavior has typically been defined as behavior during waking moments in which energy expenditure is low (< = 1.5 metabolic units), and occurring while a person is sitting or reclining (Tremblay et al., 2017). While this can include automotive transportation, sitting while doing schoolwork, or having face-to-face conversations, increasingly this involves screen-based sedentary behaviors (SBS), such as television watching, playing video games, internet surfing, social media use, mobile phone use, and texting (Tremblay et al., 2017).

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of youth SBS behaviors is high. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System monitors these behaviors among U.S. children through two items: 1) three or more hours per day of television viewing, and 2) three or more hours per day of using a computer or playing video/computer, other than for school work (Kann et al., 2016). In 2015, approximately 25% of children reported three or more hours of television viewing daily, and about 42% reported using a computer/playing video games for three or more hours daily (Kann et al., 2016). While boys and girls reported comparable rates of television watching and computer use/video games, the rates of screen time among Hispanic adolescents were higher than among white youth, at nearly 28% versus 20% for television viewing, and 46% versus 39% for computer use/video game playing, respectively (Kann et al., 2016). Evidence also suggests that socio-economically disadvantaged youth spend more time engaging in sedentary behavior compared to more advantaged youth (Gebremariam et al., 2015; Iannotti & Wang, 2013).

Existing research suggests that SBS behaviors may have implications for adolescent mental health and social-behavioral problems, although the majority of studies continue to explore data cross-sectionally (Costigan et al., 2013; Hoare et al., 2016). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found that screen use is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and psychological distress among adolescents (see Costigan et al., 2013), with worse mental health with high-duration screen time, for example of more than two or three hours daily (Hoare et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). Especially among girls, SBS behaviors have been associated with lower self-reported psychological well-being and social support (Costigan et al., 2013). Suchert, Hanewinkel, Isensee, and Iäuft Study Group (2015) found that screen-based sedentary behaviors were especially problematic for girls in terms of their relationship with depressive symptoms and low self-esteem. While certain longitudinal research shows that adolescent screen time is associated with subsequent mental health symptoms (Primack, Swanier, Georgiopoulos, Land, & Fine, 2009), other work shows that mental health symptoms are associated with subsequent screen time (Gunnell et al., 2016), indicating that screen time may be a form of coping.

Indeed, findings have been inconsistent (see Casiano, Kinley, Katz, Chartier, & Sareen, 2012; Ferguson, 2017; Hoare et al., 2016; Maras et al., 2015), likely due to methodological differences across studies, differences in samples, and discrepancies in how sedentary behavior and mental health outcomes have been operationalized and measured. Moreover, changes in patterns and type of screen use across the years may influence the findings, requiring more recent longitudinal studies. Some studies highlight the need for further research that: 1) examines relationships longitudinally rather than cross-sectionally, 2) investigates moderating variables that might explain discrepant findings by subgroup, and 3) examines the possible reciprocal relationships between internalizing symptoms and screen-based sedentary behaviors.

Guidelines for screen time among children and adolescents reflect the complexity in research findings and the need for additional research. While American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines have clear screen time limits for children 0–5 years of age (AAP Council on Communications and Media, 2016a), specific limits for older children and adolescents were recently removed (see AAP Council on Communication and Media, 2016b). Among several reasons, this reflects that existing research shows both benefits and risks to adolescent media use, and that there may not be a single recommendation for setting limits around media use for this age group. Instead, AAP recommends that for older children, parents and pediatricians develop “Family Media Use Plans” individualized to the developmental stage, needs and situation of each child (AAP Council on Communications & Media, 2016b, p. 3). These guidelines highlight the importance of assessing more than just amount of screen time, but also the content, context and quality of media use in order to understand its relationship to youth mental health (Hoare et al., 2016; Ybarra, Alexander, & Mitchell, 2005). Continued research is needed to build our understanding of how mental health and SBS behaviors are related among different subgroups and as screen use activities and patterns change (Lewis, Napolitano, Buman, Williams, & Nigg, 2017).

The objective of this study is to better understand screen-based sedentary behavior, internalizing symptoms, and the relationship between these two variables across time among a vulnerable subgroup: Hispanic adolescents in the U.S. Given the high risk of internalizing symptoms among Hispanic girls, analyses of this group of adolescents by gender can add to our understanding regarding mental health risks for these young people. This work was driven by the following research questions: 1) What are the levels and patterns of screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms for Hispanic youth, and how do these differ by gender? and 2) What is the relationship between screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms across time for Hispanic youth, and how do these relationships differ by gender? We hypothesized that there would be a bi-directional relationship between screen time behaviors and internalizing symptoms across time.

1. Method

1.1. Research design

The population of interest is Hispanic adolescents. Sample data for this research come from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial of the Familias Unidas intervention, an evidence based program that has been found to prevent substance use, sexual risk and internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents (Perrino et al., 2016; Prado et al., 2007, 2012). This effectiveness trial was conducted from September 2010 to June 2014, recruiting adolescents and parents from 18 public middle schools in Miami during September 2010–November 2011 and following them for 30 months post-Baseline during January 2013–June 2014 (Estrada et al., 2017). Effectiveness trials such as this one test the effects of an intervention in real-world settings without the controls of an efficacy trial (Gartlehner, Hansen, Nissman, Lohr, & Carey, 2006). To be eligible for the study, adolescents had to identify as being of Hispanic origin, in eighth grade in school at the time of baseline assessment (mean age was 13.4 years), live with an adult primary caregiver who was willing to participate, live within the catchment areas of the participating middle schools, and plan to live in South Florida for the entire study period. Other than indicated by these criteria, this study did not seek to sample youth with specific characteristics.

Following participant recruitment, a total of 746 Hispanic adolescents were randomized to the intervention or a community practice control condition, which involved the standard education and services available to Miami-Dade County Public School students. The present analyses included only participants from the community control condition, because this allowed an examination of the relationship among variables longitudinally in the absence of intervention. Analyses show no statistically significant differences between intervention and control group at Baseline on demographics (adolescent’s age or gender, family income, parent education), internalizing symptoms or screen-based sedentary behaviors.

1.2. Human subjects considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Miami’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the Miami Dade County School’s Research Board. Parent participants provided informed consent, while adolescents provided assent to participate.

1.3. Participants

Participants were 370 Hispanic adolescents from the control condition. As seen in Table 1, 47.6% (n = 176) of participants were girls, and the sample’s mean age was 13.4 years (SD = 0.69) at baseline. Mean ages at subsequent time-points were: 13.8 (SD = 0.74) at 12 month-, 14.8 (SD = 1.09) at 18 month-, and 15.9 years (SD = 0.78) at 30-month follow-ups. All participants were of Hispanic background, with approximately 44% of youth being foreign-born. Foreign born youth came primarily from Cuba (17%), followed by multiple countries in Central and South America, as well as the Caribbean (less than 4% from each of the other countries). Parents had a mean of 12.54 (SD = 2.61) years of education. Approximately 49.5% (n = 183) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, which is below the U.S. federal poverty level of $24,250 for a family of four in 2015 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2015). Nearly 35.1% (n = 130) had an annual income between $20,000–49,000, while 13.2% (n = 49) had a family income of $50,000 or greater. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic variables between boys and girls.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Participant characteristics | Full sample (n=370) | Males (n=194, 52.4%) | Females (n=176, 47.6%) | t- or χ2(df)a | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Mean age at Baseline | 13.38 (0.69) | 12.85 (0.69) | 13.81 (0.69) | .50 (366) | = .612 | |||

| Parental education – Years at Baseline | 12.54 (2.61) | 12.54 (2.60) | 12.52 (2.61) | .05 (368) | = .961 | |||

| Annual Household Income at Baseline | ||||||||

| – $0–$9,999 | 78 (21.1) | 44 (22.7) | 34 (19.3) | 7.40 (4) | = .149 | |||

| – $10,000–$19,999 | 105 (28.4) | 60 (30.9) | 45 (25.6) | |||||

| – $20,000–$29,999 | 64 (17.3) | 36 (18.6) | 28 (15.9) | |||||

| – $30,000–$49,999 | 66 (17.8) | 25 (12.9) | 41 (23.3) | |||||

| – > = $50,000 | 49 (13.2) | 26 (13.4) | 23 (13.1) | |||||

| – Missing | 8 (2.2) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.8) | |||||

| SBS Behaviors at Baseline ( > 2 h per day) | ||||||||

| – Watching television | 234 (63.2) | 128 (66.0) | 106 (61.2) | 1.31 (1) | = .252 | |||

| – Playing video, computer or electronic games | 169 (45.7) | 108 (55.7) | 61 (34.7) | 16.42 (1) | < .001 | |||

| – Instant messaging, emailing, or browsing internet | 171 (45.0) | 70 (36.1) | 101 (57.4) | 16.85 (1) | < .001 | |||

| – Talking on the phone | 164 (44.3) | 72 (37.1) | 92 (52.3) | 8.59 (1) | < .001 | |||

| Main repeated outcomes | ||||||||

| Internalizing Symptoms Scale | ||||||||

| – Time 1: Baseline | 10.59 (9.20) | 8.89 (8.61) | 12.36 (9.52) | 3.57 (368) | < .001 | |||

| – Time 2: 6-month | 9.82 (10.47) | 7.73 (9.13) | 12.14 (11.37) | 4.01 (347) | < .001 | |||

| – Time 3: 18-month | 9.01 (8.80) | 7.65 (8.17) | 10.43 (9.23) | 2.88 (326) | < .01 | |||

| – Time 4: 30-month | 8.16 (9.11) | 6.51 (7.83) | 9.92 (10.04) | 3.36 (311) | < .001 | |||

| SBS Behaviors Scale | ||||||||

| – Time 1: Baseline | 2.69 (.99) | 2.64 (.97) | 2.74 (1.00) | .91 (368) | = .365 | |||

| – Time 2: 6-month | 2.80 (1.01) | 2.75 (1.00) | 2.86 (1.02) | 1.07 (348) | = .286 | |||

| – Time 3: 18-month | 2.63 (.94) | 2.62 (.94) | 2.63 (.93) | .12 (326) | = .906 | |||

| – Time 4: 30-month | 2.62 (.92) | 2.52 (.92) | 2.72 (.90) | 1.91 (310) | = .056 | |||

These values represent the statistical comparison across gender.

1.4. Measures

Participants were assessed at four time-points across 30 months: baseline, 6-, 18- and 30-months. Parent participants were compensated $40, $45, $50, and $55 respectively for assessment completion at each time-point, whereas adolescents were compensated one, two, three, and four movie tickets respectively for assessment completion at each time-point. Family socio-demographic information was provided by the parent, while other data were provided by the youth.

1.4.1. Demographics

Demographics were collected at baseline, and included participant gender, age, birthplace, language(s) spoken at home, and number of years living in the U.S. Annual family income was a categorical variable collected at baseline. Parents’ number of completed years of education was a continuous variable also collected at baseline.

1.4.2. Screen-based sedentary behavior

The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents’ (PAQ-A; Kowalski, Crocker, & Donen, 2004) Sedentary Behavior subscale is a 4-item self-report measure completed by adolescents that includes items that assess the amount of time during the preceding week spent: 1) watching television, 2) playing video/computer games, 3) instant messaging, emailing, texting or browsing internet, and 4) using the telephone. Using the telephone was categorized as “screen-time” because of the pervasive use of screen-based phones, including during the study time period of 2010–2014. Indeed, while 23% of U.S. teenagers had smartphones in 2012, 77% had cell phones and 75% reported texting. By 2012, daily telephone conversations between teenagers and peers were down to 15% from 30% in 2009, and by 2014, 88% of teenagers reported access to a mobile phone, 73% to a smartphone (Lenhart, 2012; 2015). This measure’s questions instructed participants to exclude school- or work-related screen time. For the first three items, the response scale was 1 (not at all/less than 1 h) to 5 (4 h per day or more). The response scale for telephone use was 1 (not at all/less than 15 min/day) to 5 (2 h per day or more). A mean score of these four items was calculated in the analyses. For descriptive purposes, also calculated was a categorical variable using “at least 2 h per day” of each form of screen-time as the cut-point given findings that worst symptoms are associated with more than 2 or 3 h of daily use (Hoare et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). This measure has been used successfully with diverse adolescent groups (Janz, Lutuchy, Wenthe, & Levy, 2008; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2009).

1.4.3. Adolescent internalizing symptoms

The internalizing subscale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach, 1991) measure was used to measure adolescent reports of internalizing symptoms over the preceding 6 months. This 30-item scale is a self-report measure that uses a three-point Likert scale for each item ranging from “Not True” (0). “Somewhat or Sometimes True” (1) or “Very True or Often True” (2). Internalizing scale items include: “I cry a lot”, “I am nervous or tense”, “I feel overtired”, “I feel worthless or inferior”. The internalizing problems variable was created by summing three subscales: a) anxious-depressed (α = 0.86 at baseline), b) withdrawn (α = 0.78 at baseline), and c) somatic complaints (α = 0.82 at baseline). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating higher levels of internalizing symptoms. Prior research has found generalizability of YSR scores across cultures and high concurrent validity with measures of depressive symptoms (de Groot, Koot, & Verhulst, 1996).

1.5. Statistical analyses

The analyses involved several steps, all conducted using Mplus version 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). For Research Question 1, descriptive statistics were used to characterize the internalizing symptoms and screen-based sedentary behavior levels of the control group sample. Separate descriptive statistics were conducted by gender. For Research Question 2, bivariate latent growth curve modeling (LGCM; Curran & Hussong, 2003) was used to estimate the relationship between internalizing symptoms and SBS behavior across the four time-points. Moderating effects of gender were estimated on the LGCM. To investigate that the same model parameters were estimated by gender, the parameter equality tests were conducted using Wald-statistics. Then, the relationship between screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms across time was also examined using cross-lagged panel models (Selig & Little, 2012). We also conducted the same gender equality tests for regression coefficients in the cross-lagged panel model. To evaluate model fit, we report chi-square, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Because the chi-square test is often statistically significant in larger samples (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980), we considered good model fit when CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.05, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 (Kline, 2010). Missing data were accounted for using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) procedures (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

2. Results

The first research question examined levels and trajectories of screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms among youth, as well as differences by gender. Table 1 reports the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics, levels of internalizing symptoms and sedentary behaviors for the whole sample and by gender. In terms of the internalizing subscale scores, baseline means (standard deviation) for the “withdrawn” subscale were 3.99 (3.03) for girls and 3.32 (2.79) for boys, “anxious/depressed” subscale were 5.34 (4.65) for girls and 3.68 (3.97) for boys, and “somatic complaints” subscale were 3.04 (3.01) for girls and 1.98 (2.68) for boys. These subscales scores all fell within the normal and non-clinical range, consistent with a community-based sample of youth (Achenbach, 1991). However, at all time-points, girls had higher and statistically significant differences in levels on the internalizing symptoms scale compared to boys.

Mean scores on the screen-based sedentary behavior summary scale were not significantly different by gender at any time-point, as shown in Table 1. However, comparisons of certain specific types of SBS behavior did differ by gender. The percentage of youth engaging in at least two hours of sedentary behavior at baseline shows that while viewing television for more than 2 h per day was similar by gender (66% for boys, 61% for girls; χ(1)2 = 1.31, p = .252), higher percentages of boys had more than 2 h of daily video and computer game playing (56% for boys, 35% for girls; χ(1)2 = 16.42, p < .001), whereas a higher percentage of girls had more than 2 h of daily internet, instant messaging and email use behaviors (36% for boys, 57% for girls; χ(1)2 = 16.85, p < .001), as well as phone use (37% for boys, 52% for girls; χ(1)2 = 8.59, p < .001).

2.1. Growth model analyses

Bivariate latent growth curve modeling was used to model change across time for both SBS behaviors and internalizing symptoms, adjusting for adolescent age, adolescent gender, parent education and family income. Model fit was good (χ2 = 64.10, p < .01; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04). Of the covariates, age (unstandardized b = 1.64, p = .01) and female gender (unstandardized b = 3.50, p < .001) were significantly and positively associated with the intercept of internalizing. Neither of the adjusted trajectories of internalizing symptoms or SBS behaviors were significantly different from zero, and neither demonstrated significant variation by gender (Wald-test: 0.22, p = .90).

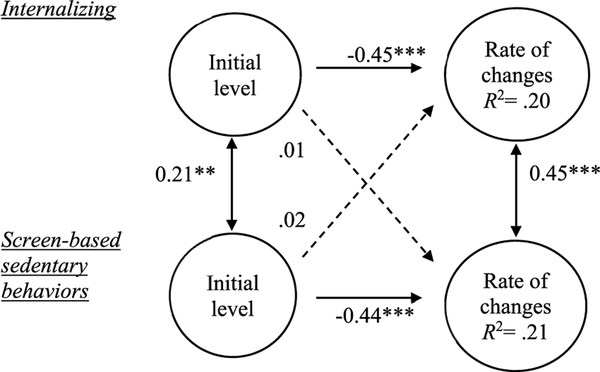

The second research question investigated the relationship between screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms over this time-period in adolescence. We specified regression paths from the intercepts to the slopes in the bivariate growth model, again adjusting for adolescent gender, adolescent age, parent education and family income (see Fig. 1). The results suggest that initial level of internalizing symptoms was not associated with the trajectory of SBS behaviors (standardized β = 0.01, p = .92). Similarly, initial level of SBS behaviors did not predict the trajectory of internalizing symptoms (standardized β = 0.02, p = .81). However, significant correlations were found between baseline levels of internalizing and SBS behaviors, as well as between the trajectories of internalizing symptoms and SBS behaviors. In other words, there was a positive and significant association between internalizing symptoms and sedentary behaviors in both their initial levels (r = 0.21, p = .01) and in their trajectories (r = 0.45, p < .001). These associations were consistent across gender (Wald-test: 5.32, p = .50).

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal associations in growth parameters between internalizing symptoms and screen-based sedentary behaviors adjusting for adolescent gender, adolescent age, parent education and household income. Note. All coefficients are standardized. Dotted lines indicate non-significant paths. χ2 = 64.10, p < .01, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

2.2. Cross-lagged panel analyses

To further clarify the second research question examining the relationship between screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms across time, cross-lagged panel analyses were used to investigate the direction of the relationship, and whether a bidirectional relationship was evident (Fig. 2). Model fit was good (χ2 = 10.85, p = .21; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.02). As expected in longitudinal data analyses, there were significant auto-regressive pathways for both internalizing symptoms and SBS behaviors. Within every time-point, internalizing symptoms were positively and significantly correlated with SBS behaviors, providing evidence of the co-occurrence of internalizing symptoms and SBS behaviors among these Hispanic adolescents.

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal associations between internalizing symptoms and screen-based sedentary (SBS) behaviors over four time points adjusting for adolescent gender, adolescent age, parent education and household income (n = 370). Note. All coefficients were standardized. Dotted lines indicate non-significant paths. χ2 = 10.85, p = .21. CFI = 0.99. RMSEA = 0.03. SRMR = 0.02. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

This model also examined transactional effects between screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms. The results showed that the relationships between internalizing symptoms and SBS behaviors between adjacent time-points were not statistically significant, although one relationship approached significance: the association between internalizing symptoms at 18months post-baseline and SBS behaviors at 30-months post-baseline (standardized β = 0.10, p = .055). This finding suggests that higher internalizing symptoms when youth were approximately 15 years old may be associated with higher levels of SBS behavior when youth were 16 years old.

Post-hoc analyses examined differences by gender by estimating the model separately for boys and girls. The association between internalizing behavior at 18-months and SBS behavior at 30-months was significant for girls (standardized β = 0.20 p < .01) but not boys (standardized β = −0.02, p = .81), as seen in Fig. 3. This difference was statistically significant (Wald-test: 4.32, p = .04).

Fig. 3.

Gender differences for hypothesized cross-lagged model Note. All coefficients were standardized. Dotted lines indicate non-significant paths. χ2 =15.09, p = .52. CFI = 1.00. RMSEA < 0.001. SRMR = 0.02. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

3. Discussion

Existing research regarding the relationship between screen-based sedentary behavior and mental health among adolescents has not always yielded consistent findings (see Casiano et al., 2012; Hoare et al., 2016; Suchert et al., 2015). Methodological differences across studies, overreliance on cross-sectional analyses, changing patterns of screen use across time, and potential differences across youth subgroups require continued research in this area. The present analyses respond to this need by studying a vulnerable group of Hispanic adolescents in the U.S. and exploring potential gender differences and bidirectional relationships between these variables across time. The study’s sample is noteworthy in the large proportion reporting low family income, with nearly 50% having annual household incomes below $20,000. This is a subgroup that has been found to be at special risk for poor mental health and sedentary behavior (Gebremariam et al., 2015; Yoshikawa et al., 2012).

The first research question investigated levels and patterns of screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms among these youth, as well as possible gender differences. Girls showed significantly higher levels of internalizing symptoms compared to boys at every time-point, similar to what has been documented in prior research (Garber, 2006), including with Hispanic samples (Kann et al., 2016). While mean levels on subscales of internalizing symptoms were at non-clinical levels, as expected in a community sample such as this one, the differences by gender are noteworthy and reinforce the need to monitor adolescent girls for mental health symptoms.

As anticipated, rates of screen-based sedentary behavior in the sample were substantial. At baseline, almost two-thirds of youth watched television, and nearly half played video or computer games, engaged in email, instant messenger or texting, and used the telephone, for at least two hours per day. While mean levels of SBS behaviors (e.g., internet, television, mobile phone use) were similar by gender, girls and boys showed different and potentially consequential patterns of screen use. Levels of high duration television viewing were similar for boys and girls, but boys showed higher levels of video/computer/electronic games use, while girls had higher levels of instant messaging/emailing/browsing internet, and telephone use. These results suggest that girls’ screen use was more likely to involve social contact and communication. These high rates indicate a need to monitor high duration screen use among adolescents (Hoare et al., 2016; Suchert et al., 2015).

The second research question investigated how internalizing symptoms and SBS behaviors were related to one other and how these relationships might differ by gender. Within each time-point, SBS behaviors were significantly associated with internalizing symptoms for both genders, a cross-sectional association documented in previous research (Kremer et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Maras et al., 2015). Longitudinally, trajectories of SBS behavior and internalizing symptoms were also significantly related to one another. Screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms appear to co-occur in these adolescents.

Yet, our hypothesis that there would be a bidirectional relationship between internalizing symptoms and screen-based sedentary behaviors across time was not supported. SBS behaviors were not associated with subsequent internalizing symptoms. It may be that the quantity of screen time must exceed a certain amount to impact mental health, as has been found in some studies (Ferguson, 2017; Hoare et al., 2016). On the other hand, higher internalizing symptoms were associated with more subsequent SBS behavior, but only among girls and only across the last two time-points. Although this was a small association, girls’ internalizing symptoms at the age of 14–15 years were associated with later SBS behaviors when they were almost 16 years old. Other studies have reported that internalizing symptoms can affect later screen use (Brunet et al., 2014; Gunnell et al., 2016).

Girls experiencing internalizing symptoms, such as depressed mood, withdrawal, or anxiety symptoms, may be motivated to engage in more screen-based activities because these often require less effort and energy, and may carry less social risk compared to more direct, face-to-face interactions (Radovic, Gmelin, Stein, & Miller, 2017; Suchert et al., 2015). While this may be compelling to an adolescent struggling with internalizing symptoms, some screen use such as television viewing, may ultimately be counter-productive if done in excess because this has the potential to reinforce apathy, displace direct social contact, and reduce socialization opportunities (George & Odgers, 2015; Selfhout, Branje, Delsing, ter Bogt, & Meeus, 2009), which are important factors related to internalizing symptoms and mental health disorders (Suchert et al., 2015; Trosper, Buzzella, Bennett, & Ehrenreich, 2009).

The fact that this longitudinal relationship was found only among girls is not surprising given that others have reported gender differences related to screen use (Suchert et al., 2015). It is noteworthy that although television viewing was high among both genders, girls in this study showed some unique patterns of screen use compared to boys, in particular high-duration screen use that involved social contact, such as emailing, telephone use and texting. Studies show that girls are more likely than boys to cope with depression through expressing emotions and seeking social support (Malooly, Flannery, & Ohannessian, 2017) so this type of screen use may represent an attempt to reach out to others as a coping strategy. Interestingly this longitudinal relationship was only evident among older adolescent girls, perhaps because they are more independent and have greater access or less restrictions on technology (Minges et al., 2015).

These study findings seem to support the AAP conclusion that placing broad-based limits on screen-time may not be warranted because a single guideline may not fit all youth (AAP Council on Communications & Media, 2016b). AAP’s call for parental monitoring is important in promoting supervision of the amount of time as well as content and context of screen use, important aspects of screen use. Indeed, future research should assess duration of screen time together with content and context of screen use. Recent research, including some with depressed youth, suggests that adolescents often use technology and social media in positive ways including to connect socially, seek social support, and find helpful internet material (Ehrenreich & Underwood, 2016; Gunnell et al., 2016; Horgan & Sweeney, 2010; James et al., 2017; Radovic et al., 2017; Selfhout et al., 2009). Indeed, some forms of screen time may promote coping, and there is increasing use of web- and screen-based interventions to address youth mental health (Reyes-Portillo et al., 2014).

The strengths of this study lie in its sample of Hispanic, disadvantaged youth at high risk for internalizing symptoms. Results can inform existing evidence-based preventive interventions for Hispanic youth, many of which are family-based (see Prado et al., 2007; 2012). Given the centrality of families for Hispanic culture and as protective factors for mental health (Scott, Wallander, & Cameron, 2015), parents can play an important role in monitoring youth for screen use and internalizing symptoms, as well as in providing support and assistance to youth in coping with internalizing symptoms. The longitudinal research design is another strength, allowing for tests of reciprocal and more complex relationships among variables through time and adolescent development. Yet, there are limitations to this research. First, because self-reports can be open to bias, integrating more objective measures, such as accelerometers for sedentary behaviors and clinician diagnoses for internalizing problems can bolster future research. Second, the reference timepoints for reporting internalizing symptoms (i.e., past 6 months) and SBS behaviors (i.e., past week) are not parallel and may have affected the cross-sectional analyses. The longitudinal analyses, which capture latent change over time, are less likely to have been affected. Third, although phone use was common among youth during the study period as described in the Measures section, categorizing telephone use as screen time may be a limitation because the assessment question does not specify this as screen use. Finally, the SBS behaviors measure excluded screen time for schoolwork purposes, something that future research might address.

As technology continues to evolve, it will be important to attend to changing types and patterns of screen use. This study was conducted between the years 2010–2014, a time when screen time among adolescents was already prevalent yet growing. For example, the Pew Research Center reported that in 2009, 93% of 12–17 year-olds went online, 75% had cell phones, and 76% of families with teenage children had home access to broadband internet (Lenhart, 2012; Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr, 2010). By 2014, 88% had access to a mobile phone, 73% to a smartphone (Lenhart, 2015). As mobile technologies, such as smartphones become more pervasive among youth, the impact of constantly available screens may influence behavioral outcomes (George & Odgers, 2015), including among youth who experience internalizing symptoms. These changes must be considered in any longitudinal study that examines screen and technology use and its relationship to potential health outcomes.

In conclusion, adolescent girls and boys evidence distinct health risk behaviors that are important considerations for preventive interventions, including different rates of internalizing symptoms and different patterns of screen-based sedentary behaviors. The pervasive and increasing use of technology in daily life, changing patterns and types of screen based sedentary behaviors, and the potential for both negative and positive effects of different screen use have implications for preventive interventions (James et al., 2017; Madden et al., 2013). The results of this study suggest that internalizing symptoms should continue to be a target for preventive interventions, especially among Hispanic girls. Future research is needed to continue to inform parents and clinicians so they can better monitor youth for symptoms and behaviors that can affect their psychological well-being.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant #R01 DA025192- Guillermo Prado, Principal Investigator and an administrative supplement for research on gender differences from National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) grant #R01 MD007724- Guillermo Prado and Sarah Messiah, Principal Investigators.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Council on Communications and Media (2016a). Media and young minds. Pediatrics, 138, e20162591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Council on Communications and Media (2016b). Media use in school-aged children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 138, e20162592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, & Bonnet DC (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, & Hayatbakhsh R. (2014). Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet J, Sabiston CM, O’Loughlin E, Chaiton M, Low NC, & O’Loughlin JL (2014). Symptoms of depression are longitudinally associated with sedentary behaviors among young men but not among young women. Preventive Medicine, 60, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiano H, Kinley DJ, Katz LY, Chartier MJ, & Sareen J. (2012). Media use and health outcomes in adolescents: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21, 296–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan SA, Barnett L, Plotnikoff RC, & Lubans DR (2013). The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, & Hussong AM (2003). The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 526–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich SE, & Underwood MK (2016). Adolescents’ internalizing symptoms as predictors of the content of their Facebook communication and responses received from peers. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2, 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada Y, Lee TK, Huang S, Tapia M, Velazquez MR, … Prado, G. (2017). Parent-centered prevention of risky behaviors among Hispanic youths in Florida. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 607–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ (2017). Everything in moderation: Moderate use of screens unassociated with child behavior problems. Psychiatric Quarterly, 4, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J. (2006). Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31, 104–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, Lohr KN, & Carey TS (2006). A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59, 1040–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremariam M, Altenburg T, Lakerveld J, Andersen L, Stronks K, Chinapaw M, et al. (2015). Associations between socioeconomic position and correlates of sedentary behaviour among youth: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 16, 988–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, & Odgers CL (2015). Seven fears and the science of how mobile technologies may be influencing adolescents in the digital age. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 832–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot A, Koot HM, & Verhulst FC (1996). Cross-cultural generalizability of the youth self-report and teacher’s report form cross-informant syndromes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 651–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell KE, Flament MF, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, Schubert N, et al. (2016). Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Preventive Medicine, 88, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, & Allender S. (2016). The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 13, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan A, & Sweeney J. (2010). Young students’ use of the internet for mental health information and support. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EK, & Gullone E. (2008). Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: A review of family systems literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 92–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti RJ, & Wang J. (2013). Patterns of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, Davis K, Charmaraman L, Konrath S, Slovak P, Weinstein E, et al. (2017). Digital life and youth well-being, social connectedness, empathy, and narcissism. Pediatrics, 140, S71–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz KF, Lutuchy EM, Wenthe P, & Levy SM (2008). Measuring activity in children and adolescents using self-report: PAQ-C and PAQ-A. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40, 767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, … Chyen D. (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 1–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, & Ustun TB (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20, 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, … Petukhova M. (2012). Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69 372–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2010). Principles and practice of structural equations modeling (3rd ed). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski KC, Crocker PR, & Donen RM (2004). The physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) and adolescents (PAQ-A) manual. College of Kinesiology, University of Saskatchewan. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer P, Elshaug C, Leslie E, Toumbourou JW, Patton GC, & Williams J. (2014). Physical activity, leisure-time screen use and depression among children and young adolescents. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17, 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. (2012. March 19). Teens, smartphones & texting. Pew internet & American life project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/03/19/teenssmartphones-texting/. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. (2015. April). A majority of American teens report access to a computer, game console, smartphone, and a tablet Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://http:///www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/a-majority-of-american-teens-report-access-to-a-computer-game-console-smartphone-and-a-tablet/.

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, & Zickuhr K. (2010, February). Social media & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED525056.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BA, Napolitano MA, Buman MP, Williams DM, & Nigg CR (2017). Future directions in physical activity intervention research: Expanding our focus to sedentary behaviors, technology, and dissemination. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 112–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Wu L, & Yao S. (2016). Dose-response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50, 1252–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, Gasser U, Duggan M, Smith A, et al. (2013. May). Teens, social media, and privacy. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewinternet.org/2013/05/21/teens-social-media-and-privacy/. [Google Scholar]

- Malooly AM, Flannery KM, & Ohannessian CM (2017). Coping mediates the association between gender and depressive symptomatology in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41, 185–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. (2015). Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Preventive Medicine, 73, 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez D, Martínez-de-Haro V, Pozo T, Welk GJ, Villagra A, Calle ME, … Veiga OL (2009). Reliability and validity of the PAQ-A questionnaire to assess physical activity in Spanish adolescents. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 83, 427–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minges KE, Owen N, Salmon J, Chao A, Dunstan DW, & Whittemore R. (2015). Reducing youth screen time: Qualitative metasynthesis of findings on barriers and facilitators. Health Psychology, 34, 381–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Brincks A, Howe G, Brown CH, Prado G, & Pantin H. (2016). Reducing internalizing symptoms among high-risk, Hispanic adolescents: Mediators of a preventive family intervention. Prevention Science, 17, 595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, … McCollister K. (2012). The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: Main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125(Suppl 1), S18–S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, … Lopez B. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 914–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Swanier B, Georgiopoulos AM, Land SR, & Fine MJ (2009). Association between media use and depression in young adulthood : A longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radovic A, Gmelin T, Stein BD, & Miller E. (2017). Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Portillo JA, Mufson L, Greenhill LL, Gould MS, Fisher PW, Tarlow N, et al. (2014). Web-based interventions for youth internalizing problems: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 1254–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Scaramella L, Wallace LE, & Conger RD (1999). First onset of depressive or anxiety disorders predicted by the longitudinal course of internalizing symptoms and parent-adolescent disagreements. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SM, Wallander JL, & Cameron L. (2015). Protective mechanisms for depression among racial/ethnic minority youth : Empirical findings, issues and recommendations. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18, 346–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, ter Bogt TF, & Meeus WH (2009). Different types of internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 819–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, & Little TD (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data In Laursen B, Little TD, & Card NA (Eds.). Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, & Isensee B. Iäuft Study Group. (2015). Sedentary behavior, depressed affect, and indicators of mental well-being in adolescence: Does the screen only matter for girls? Journal of Adolescence, 42, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, … Chinapaw MJ (2017). Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)–terminology consensus project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosper SE, Buzzella BA, Bennett SM, & Ehrenreich JT (2009). Emotion regulation in youth with emotional disorders: Implications for a unified treatment approach. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 234–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, & Human Services (2015). 2015 U.S. Federal poverty guidelines used to determine financial eligibility for certain federal programs. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/2015-poverty-guidelines.

- Wesselhoeft R, Sorensen MJ, Heiervang ER, & Bilenberg N. (2013). Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents - a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151, 7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Alexander C, & Mitchell KJ (2005). Depressive symptomatology, youth internet use, and online interactions: A national survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, & Beardslee WR (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist, 67, 272–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]