Abstract

Within the field of biomedical research in the United States, the proportion of underrepresented minorities at the Full Professor level has remained consistently low, even though trainee demographics are becoming more diverse. Underrepresented groups face a complex set of barriers to achieving faculty status, including imposter syndrome, increased performance expectations, and patterns of exclusion. Institutionalized racism and sexism have contributed to these barriers and perpetuated policy that excludes underrepresented minorities. These barriers can contribute to decreased feelings of belonging, which may result in decreased retention of underrepresented minorities. Though some universities have altered their hiring practices to increase the number of underrepresented minorities in the applicant pool, these changes have not been sufficient. Here we argue that departmental invited seminar series can be used to provide trainees with scientific role models and increase their sense of belonging while institutions work towards more inclusive policy. In this study, we investigated the demographics (gender and race) of invited seminar speakers over 5 years to the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Michigan. We also investigated current trainee demographics and compared them to invited speaker demographics to gauge if our trainees were being provided with representation of themselves. We found that invited speaker demographics were skewed towards Caucasian men, and our trainee demographics were not being represented. From these findings, we proposed policy change within the department to address how speakers are being invited with the goal of increasing speaker diversity to better reflect trainee diversity. To facilitate this process, we developed a set of suggestions and a web-based resource that allows scientists, committees, and moderators to identify members of underserved groups. These resources can be easily adapted by other fields or subfields to promote inclusion and diversity at seminar series, conferences, and colloquia.

INTRODUCTION

Long-standing systemic bias, sexism, and racism have contributed to the underrepresentation of many racial and ethnic groups, as well as of women, in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields (1–4). Specifically, within the field of biomedical research in the United States, the proportion of underrepresented minorities at the Full Professor level has remained consistently low at 4% (survey data taken from the NIH from 2001 to 2013) (5, 6). Similar discrepancies exist for women in biomedical sciences, as Full professorships are currently held mostly by men (7, 8). As demographics of faculty within the biomedical sciences remain skewed towards Caucasian men, the demographics of trainees (graduate students and postdocs) are becoming more diverse (5).

Policy changes are needed to support inclusion of all individuals, particularly in the biomedical sciences, since underrepresented groups face a complex set of barriers to achieving faculty status (9). For example, the dedication of women—who have children—to their work is perceived to be less than that of their colleagues, including men who also have children (10–12). Historically underrepresented minorities (HURM) in the United States, Asian/Asian-Americans, and women are all held to stricter competency standards and report having to work harder than Caucasian men to be perceived as legitimate scholars (13, 14). Asian/Asian-Americans suffer from imposter syndrome at greater rates than other marginalized groups, and Asian women report a lack of sponsors (15, 16). Increased performance expectations and patterns of exclusions are consistent themes in studies characterizing the HURM faculty experience (17, 18). While HURM and other marginalized groups share some experiences, differences including varying rates of hiring and tenure promotion mean that unique considerations are important for inclusion of each group (3).

Here, we argue that to support the retention of faculty from marginalized groups at the professor level, universities should provide trainees with a visual representation of themselves as successful scientists. Recent studies have shown that women in STEM benefit from women role models through improved belonging and self-efficacy (19, 20). Predictably, a lack of active inclusion also decreases self-efficacy in URMs, which can result in decreased feelings of belonging (21). However, as the demographics of trainees have become more diverse, those who are not Caucasian men are lacking role models. Institutionalized racism and sexism (22), defined as policies, societal norms, and ideologies that reinforce inequities, have played a large role in access to, inclusion in, and hiring policies at U.S. universities (23, 24). Accordingly, faculty from marginalized groups are eliminated from the applicant pool and subsequent hires, leaving university policies and practices to be predominantly created by Caucasian men. Thus, institutionalized racism and sexism are perpetuated (25, 26). Universities have begun adjusting hiring practices and creating initiatives to address inequitable hiring practices, but they have had limited results (27). Considering that most faculties within the United States are still skewed towards Caucasian men, invited seminar series are a possible tool to provide marginalized trainees with representations of themselves as successful scientists.

Invited seminar series are common within biomedical departments across the United States (28). Usually, seminar series consist of faculty members selecting a scientist from another institution to visit their university and present their research, as well as meet with other faculty members and trainees. Named lectureships follow the same format but are decided by committee and are considered more prestigious because they are named in honor of prominent local scientists. These seminar series and lectureships provide an opportunity for trainees to be exposed to research outside of their department. Additionally, being an invited speaker provides the scientist with an opportunity to make future collaborations and build their own curriculum vitae (CV). Scientists invited to give seminars are widely regarded as successful and the top in their field, providing an opportunity for trainees to be exposed to successful scientists in that field. Some studies have examined the addition of more women speakers at conferences to promote inclusion (29–31); however, we have only identified one other study that has focused on invited speakers at universities (28). In that study, Nittrouer et al. examined 3,652 talks at 50 U.S. institutions in 2013 to 2014 and found that women faculty were less likely to be invited speakers (28). We have not been able to identify any publications examining scientific speaker diversity beyond gender or how department speaker series compare to trainee diversity in that department.

In this study, we examined and compared the demographics of invited speakers to Caucasian men in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Michigan. Additionally, we compared invited speaker demographics to the current trainee demographics to gauge if trainee demographics were being represented throughout the seminar series. Following our investigation, we proposed a policy change to the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in how invited speakers are selected to promote inclusion in our department and reduce unconscious bias. In order to facilitate inviting a more diverse group of scientists, we developed a set of resources that allow scientists, within the fields of microbiology and immunology, to self-identify any underrepresented or underserved identity including HURM, non-Caucasian/non-HURM (NCNH), or a Caucasian woman. These resources will promote inclusion and diversity by providing greater representation of all scientists and will provide hosts an opportunity to invite a more diverse group of scientists.

METHODS

Each academic year, each faculty member in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Michigan has the opportunity to invite one speaker per year for a weekly seminar series. Some of these seminar slots are dedicated to named lectureships, which are decided by committee, and there are three trainee-invited speakers. We analyzed the demographics of invited speakers and faculty hosts for five academic years (fall 2014 to spring 2019) and compared them to the current trainees when the data were analyzed (spring 2019). Each speaker was only counted once, and those listed as departmental faculty members or as a “host” at any point could not also be considered “invited speakers.” The list of faculty hosts was used as a proxy for faculty demographics, because as hosts, these faculty members are visible representatives of the department. There were a total of 142 invited speakers and paired hosts. The trainees were identified using departmental e-mail lists that included master’s students, doctoral students, and postdoctoral fellows. There were 44 students and 45 postdoctoral fellows.

This was a retrospective study; thus, speakers were not asked for their identities at the time of visit. Instead, we hand-coded proxy demographics of the speakers, faculty hosts, and trainees, using first names, publicly available photos, and CVs (32–36). Information from CVs, such as undergraduate institutions and activity in HURM groups, helped inform our demographics by indicating identities that might be held by that individual. For instance, an undergraduate at a Puerto Rican university and activity in the nonprofit Ciencia Puerto Rico suggested that even if the individual appears Caucasian, they probably identify as Puerto Rican and qualify as a HURM. Because these data were collected from publicly available sources, this study was not submitted to an IRB for consideration. The presenting gender of each individual was inferred using a binary system (man/woman). Due to the low number of individuals in the study, race/ethnicity demographics were only split into three groups: Caucasian, HURM, and NCNH, each with a binary (yes/no) possibility. Caucasian was inferred using the current U.S. Census definition, where those of Middle Eastern, European, and Russian descent are included. URM individuals include those of African-American, Indigenous American, Alaskan/Hawaiian Native, and Latinx and/or Hispanic heritage (20 USC §1067k); we use the HURM designation to recognize the history of enslavement and active oppression in the United States for these populations. The NCNH group predominantly included Asian/Asian-Americans, but also African immigrants (37).

Data were compiled and figures generated in R statistical software, using relevant packages (38–50).

Code and data availability

The anonymized data, code for all analysis steps, and an Rmarkdown version of this manuscript is available at https://github.com/akhagan/Hagan_SpeakerDiversity_JMBE_2019. Template and complete instructions for generating a field-specific diversity website are available at https://github.com/diversifymicrobiology/DiversifyMicrobiology.github.io/.

RESULTS

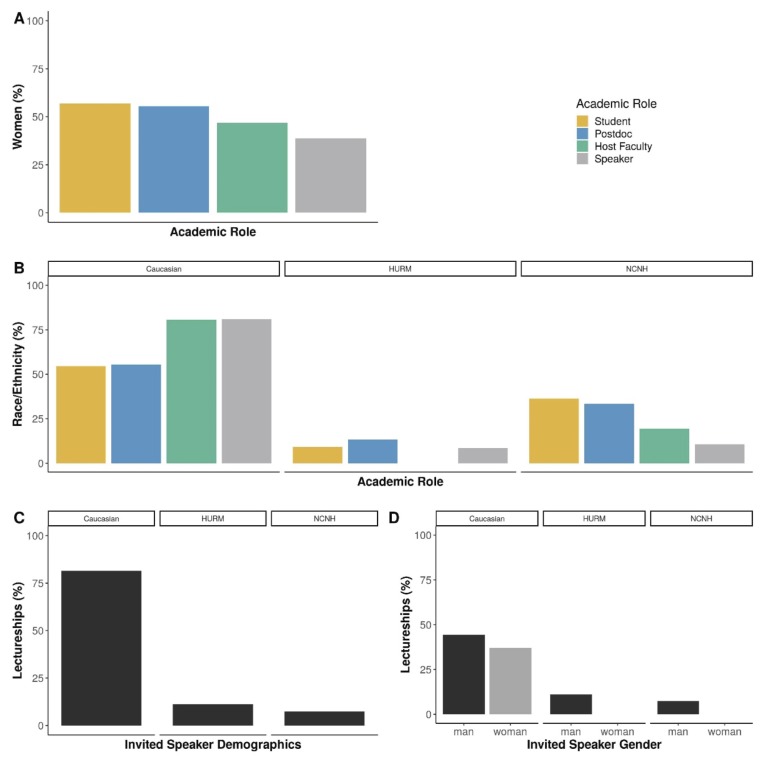

To understand the representation of women, we compared the proportion of women in each academic role. At the trainee level, more than half of students and postdoctoral fellows were women. That dropped to 46.77% of faculty hosts and 38.73% of the invited speakers (Fig. 1A). Of 27 lectureships over the 5-year period, 37.04% were awarded to women.

FIGURE 1.

The demographics of invited speakers, hosting faculty, and trainees. A) The proportion of women in each academic role. B) The proportion of each academic role represented by individuals that are Caucasian (left), HURM (center), or NCNH (right). C, D) The percentages of lectureships awarded to individuals who are C) Caucasian, HURM, or NCNH and D) Caucasian, HURM, or NCNH by gender.

Our analysis identified an overrepresentation of Caucasian individuals as hosting faculty and invited speakers (80% each), relative to the proportion of Caucasian trainees, which was 55% (Fig. 1B). We also observed declines in the representation of HURM and NCNH faculty and speakers relative to the trainees (Fig. 1B). HURM trainees made up 11% of the department, on track with the 11% of U.S. microbiology and immunology doctorates awarded in 2017 (51). However, only 8.5% of invited speakers, and none of the hosting faculty, were HURM scientists. NCNH trainees were 34% of department students and postdocs (versus 22% of U.S. microbiology and immunology doctorates in 2017), but only 19% of hosting faculty and 10.5% of invited speakers (51).

The more prestigious invited speaker lectureships were also dominated by Caucasian scientists, who comprised 81.48% of those awarded (Fig. 1C). HURM and NCNH scientists were awarded three and two lectureships, respectively. Because the intersection of identities can compound biases and outcomes, we further examined the lectureships by gender and race/ethnicity status (52). Caucasian men and women accounted for 44.44% and 37.04% of the lectureships, respectively. Just 18.52% of lectureships were held by non-Caucasian men, while none was held by non-Caucasian women (Fig. 1D).

DISCUSSION

This study found that the proportion of HURM and NCNH invited speakers were underrepresentative of the trainee populations for each group. Additionally, within the last 5 years, no HURM or NCNH woman was awarded a lectureship, despite that in 2017 non-Caucasians were 30% of the professoriate (53). This means that the department is not providing non-Caucasian trainees with adequate representation of successful scientists and failing to support an inclusive environment in terms of visual faculty representation. We also found that the proportion of women as faculty hosts and speakers in our study population is equivalent to global estimates that 40% of microbiologists are women, though women only represent about 30% of academic biomedical faculty (7, 54). Women are also overrepresented as graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in this department. Overall, Caucasian scientists are overrepresented as host faculty and invited speakers, compared to their presence as trainees, particularly when lectureships are considered.

We have not been able to identify any publications examining scientific speaker diversity beyond gender (28). This report seems to be the first, which is concerning since conclusions drawn from gender-based studies are often framed, and considered, to be applicable to other marginalized groups (e.g., HURM), for instance, the assumption that African-American and Caucasian women benefit equally from the same policy change. This is a flawed assumption (55). While there is no doubt some overlap, each group remains marginalized due to a unique complex set of factors that cannot always be solved by gender-based solutions. The historical exclusion of HURMs by U.S. institutions means that these institutions have a particular responsibility to improving the academic experience for these populations (23). We therefore call on U.S. institutions to apply intersectional framing to their discussions and research.

Departments have different processes and criteria for selecting invited speakers, but it is a matter of pride to bring the best scientists possible. The barriers to achieving faculty status for HURMs, Caucasian women, and NCNH may also impact their speaking invitations. For instance, the perceived prioritization and commitments of women to family over work may cause faculty to doubt their acceptance of a speaking invitation, despite the prestigious nature of these invitations and evidence that men and women accept at similar rates (28, 56). As a result, the faculty member may invite a different colleague who they feel is more likely to agree (and is a man). It may also be that the definition of “best” poses a problem to underrepresented and underserved groups (e.g., women, HURM, and Asian) who are held to stricter competency standards (13, 14). Some departments may only invite tenured faculty, which severely limits the number of potential speakers who are Caucasian women or non-Caucasian. Yet, another scenario is that pre-tenure faculty members invite prestigious, tenured faculty in their field to network and secure letters for their own tenure package. The increased burden of women and non-Caucasian scientists to prove competency decreases their likelihood to be considered for either tenure or as a possible source of tenure letters. In particular, the proportion of HURM faculty at the Assistant and Associate Professor level is currently higher than at the Full Professor level, so it would be difficult to increase speaker diversity if early-career researchers are not being considered (57). Even when HURM speaker rates match the proportion of HURM faculty employment, HURM trainees will be represented at a significantly higher proportion. We argue that inclusion of marginalized faculty in seminar series is an important factor to increasing their representation among Associate and Full Professors. It is just one aspect of larger institutional change that is needed, but one that will benefit trainee experiences and the CVs of faculty from marginalized groups (58).

We recognize that our proxy demographics are a limitation of the analysis and want to acknowledge that biological sex (male/female) is not always equivalent to the gender that an individual presents as (man/woman), which is also distinct from the gender(s) that an individual self-identifies as. We also want to acknowledge that there are many other identities that are not captured in this limited analysis and that our personal implicit biases may have impacted our assignment of demographics. While our pilot study combined 5 years’ worth of seminars, our n is still quite low, and we did not have other departments for comparison. Consequently, our results cannot be generalized to other departments, fields, or universities. Another limitation to looking at a single department is that trainees may interact with faculty from many other departments, depending on their research and interests. Therefore, the individual experience of representation would vary by trainee. Future research needs to consider multiple departments, universities, and/or fields to bolster generalizability. There is a paucity of research on speaker identities other than their gender, so this also needs to be addressed in future studies. However, we caution that representation is a shallow metric on which a single-minded focus can cause more harm than help (25). We recommend that future research also survey trainee and speaker experiences and trainee participation in seminar series to better understand the dynamics at play.

Instituting policy change

In an attempt to promote inclusion within the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Michigan, these data were presented to faculty members and the department chair. Since trainee demographics were not represented by the seminar speaker demographics over the past 5 years, we proposed a policy change as to how seminar speakers were being invited (Table 1). One suggestion was to switch from faculty-invited to lab-invited speakers to allow trainees to choose a speaker that best represented themselves. This is easy to implement as it does not change the overall structure of the department’s seminar series; however, for this same reason it may not have a significant impact on the diversity of invited speakers. Trainees may be pressured to invite the top individuals in their subfield or may be influenced by the same unconscious biases as faculty members. This idea can be expanded by increasing the number of trainee-invited speakers and varying the trainee group that extend invitations, for instance, by training program, career interest, and/or trainees and faculty in an identity-affinity group. Invitations from trainees are often seen as an honor by potential seminar speakers and nominating as a group may decrease the pressure to invite particular subfields or ranks.

TABLE 1.

Suggestions and resources to increase invited speaker diversity.

| Suggestion | Description | Resource |

|---|---|---|

| Trainee-invited speakers | Request suggestions from trainees, increase number of trainee-group-invited speakers | |

| Use a list | Lists of scientists from under-represented and under-served groups are available in several fields | https://DiversifyMicrobiology.github.io/resources |

| Create a list | Use the GitHub template to create a self-nomination list and resource for your field | Template can be found at https://github.com/diversifymicrobiology/DiversifyMicrobiology.github.io |

| Use resources from professional societies | Many scientific societies have a committee focused on serving individuals from under-represented and underserved backgrounds. Other societies (e.g., SACNAS) are dedicated to these issues. | SACNAS, ABRCMS, AISES, ASM Subcommittee on Minority Education |

| Think outside your sub-discipline | Speakers may introduce you to a technique that is not used in your sub-discipline | |

| Consider scientists outside research-focused universities | Scientists from industry, teaching-focused institutions, and non-profit orgs have different approaches to their research | |

| Communicate invitation expectations | Unit leadership should explicitly communicate expectations about who is invited to speak and the desired atmosphere | |

| Encourage trainees to engage | When a talk is over, ensure that trainees are the first to ask questions | |

| Foster an inclusive atmosphere | Consider the identities of individuals the speaker is meeting with. Ask if the speaker would like to meet a particular student group | |

| Highlight the journey | Invite speakers to spend a few moments describing their personal science journey |

ABRCMS, Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students; AISES, American Indian Science and Engineering Society.

We also used this opportunity to begin a conversation about the purpose of seminar speakers. Seminar speakers are sometimes invited to highlight their latest high-impact paper or to share the arc of discoveries they have made over several years of their career. While both are certainly worthwhile, there are other benefits to be gained from interacting with seminar speakers, such as how to apply new techniques and how research is framed outside research-focused universities (Table 1). Thinking more broadly about what material is valuable during a seminar series may lead to more speakers from underrepresented and underserved backgrounds, as well as more diversity of career paths. For some institutions, these suggestions represent more of a structural change to the departmental seminar series as speakers focusing on techniques or from non–research-intensive universities are usually invited as part of a professional development series. If these changes are to be implemented, many members of the department must agree to the value of including these seminars in the main departmental seminar series, and these expectations must be clearly communicated by the leadership (Table 1). Departmental leadership can also ask individuals and groups to consider the unconscious biases that may be impacting their own speaker nominee lists to combat some of the barriers to inviting diverse speakers.

Presented with these ideas, several members of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Michigan expressed interest in specific resources they might use to identify individuals from diverse identities, careers, and institutions. One suggestion is to use resources organized by professional societies such as the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) and the Society for Advancing Chicanos/Hispanics & Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) (Table 1). We also chose to develop “Diversify” resources for the microbiology and immunology fields that provide a list of scientists from underrepresented and underserved groups; these resources are not associated with a specific professional society. More information on the type of resources and how to establish a Diversify list is presented below. Using list resources like those available from professional societies as well as our Diversify resources are particularly useful, as social science research has shown that the human brain is much better at recognizing and using information (such as a strong scientific speaker) from a list than it is at recalling the same information from memory (59, 60).

We caution, however, that it is not enough to invite speakers from diverse identities. An inclusive environment must be built within the department. Start by inviting all speakers to spend a few minutes describing their personal science journey and by providing time for trainees to engage with the speaker. Trainee-speaker interactions can be encouraged by ensuring that trainees are the first to ask questions at the seminar’s conclusion and by scheduling a dedicated meeting time for trainees. As speaker schedules are being designed, departments should consider how they can foster an inclusive atmosphere during the speaker visits. Speakers should be asked prior to their visit if they have any dietary, movement, or other restrictions that should be accommodated during the visit. The identities of individuals the speaker is meeting with during their visit may also need to be considered; this is not to say that all identities of a speaker should be matched on their schedule or that a HURM speaker must have a meeting a HURM faculty member, but take care to ensure that speakers are meeting with faculty that reflect the diversity of thought and identity in the department. If a portion of the department is consistently not represented on speakers’ schedules (or extending invitations), this may reflect an opportunity for increased inclusivity in the department. Finally, speakers should be provided with ample opportunity to request meetings, not only with faculty but also with student groups or campus administrators who share similar interests. Through these steps, departments can increase the diversity of speakers invited to their seminars while also increasing the impact of the seminar speakers.

Building the Diversify resource

Motivated by a lack of resources to identify scientists who are members of marginalized and/or historically underserved groups and also inspired by resources in other fields–DiversifyEEB and DiversifyChemistry–we created DiversifyMicrobiology and DiversifyImmunology (61–64). These resources are a tool for symposium organizers, award committees, search committees, and other scientists to identify individuals to diversify their pools. Additionally, we have built these as a template to be used by other fields and organizations that wish to create their own lists. Since these lists are compiled by self-nomination, we can ensure that only scientists comfortable revealing their marginalized identities are included.

The self-nomination form is a Google form with entries logged in a private Google sheet. This form is embedded within the website and can be linked to directly. The use of a Google form allows us to maintain this database at no cost and gives us the flexibility to add questions or change response options without disrupting previous responses. Entries are logged in a private spreadsheet so that entries can be screened before being added to the public database. This screening includes two steps: confirming that each person is listed in the database only once and that any submitted website is a personal, professional website. If both criteria are met, a new entry is added to the public database spreadsheet. If a person is already listed in the database, their information is updated to the most recent submission.

This public spreadsheet is embedded in the website and can be opened separately as a locked (uneditable) Google sheet, allowing the list to be easily searched. We have chosen to list individuals’ academic information first in the spreadsheet to encourage a focus on academic achievement rather than tokenization of marginalized identities. Currently, the database lists individuals in order of self-nomination, but future versions will be re-sorted based on name and/or academic field to vary the individuals who might receive more attention for simply being at the top of the list.

The website provides an interface to the Google forms and spreadsheets with template pages for viewing the list, adding a name to the list, and finding additional resources. Importantly, our website creation tool is hosted for free by GitHub, which provides a free website for each GitHub organization. Basic tools and skills required to set up a Diversify site include knowledge of, or experience with, the version control tool git, the web tool GitHub, and a text editor. A tutorial in the DiversifyMicrobiology repository on GitHub provides links to these resources and instructions for adapting the tool to your own field (Table 1) (63). We caution creators of Diversify lists that the data voluntarily submitted to these lists are not eligible for study. IRB approval must be obtained prior to launching the list if that is a goal.

CONCLUSION

To increase the retention of Caucasian women, HURM, and NCNH trainees in the biomedical sciences, they must also be represented as experts. However, the invited speaker diversity at one department does not represent the diversity of trainees. To facilitate the identification and recruitment of individuals in these, and other, underserved groups, we have built a tool to create self-nominated, field-specific lists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Beth Moore and Harry Mobley and the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan, for their input and financial support that enabled publication of our manuscript. We thank Bonnie Krey and former speaker series coordinators Drs. Nicole Koropatkin and Kathy Spindler for providing compiled invited speaker data. We also acknowledge and thank Nick Lesniak and Dr. Ariangela Kozick for their comments and suggestions. Financial support: Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan. A.K.H. collected the data, inferred demographics, analyzed the data, created the website, and wrote the methods and results. R.M.P. created the Google lists, forms, and website content and the description of their maintenance. J.L. wrote the introduction and provided conceptual advice. A.K.H. and J.L facilitated the policy change to the UM Department of Microbiology and Immunology. All authors contributed to preparing the final manuscript. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martinez LR, Boucaud DW, Casadevall A, August A. Factors contributing to the success of NIH-designated underrepresented minorities in academic and nonacademic research positions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2018;17:ar32. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-09-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen-Ramdial S-AA, Campbell AG. Reimagining the pipeline: advancing STEM diversity, persistence, and success. BioScience. 2014;64:612–618. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang D. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. 2000;284:1085. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.9.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbs KD, McGready J, Bennett JC, Griffin K. Biomedical science Ph.D. career interest patterns by race/ethnicity and gender. PLOS One. 2014;9:e114736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyers LC, Brown AM, Moneta-Koehler L, Chalkley R. Survey of checkpoints along the pathway to diverse biomedical research faculty. PLOS One. 2018;13:e0190606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering. National Science Foundation; Alexandria, VA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314:1149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotbart HA, McMillen D, Taussig H, Daniels SR. Assessing gender equity in a large academic department of pediatrics. Acad Med. 2012;87:98–104. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823be028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coe IR, Wiley R, Bekker LG. Organisational best practices towards gender equality in science and medicine. Lancet. 2019;393:587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33188-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firth M. Sex discrimination in job opportunities for women. Sex Roles. 1982;8:891–901. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: is there a motherhood penalty? Am J Sociol. 2007;112:1297–1339. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuegen K, Biernat M, Haines E, Deaux K. Mothers and fathers in the workplace: how gender and parental status influence judgments of job-related competence. J Soc Iss. 2004;60:737–754. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair-Loy M, Rogers L, Glaser D, Wong Y, Abraham D, Cosman P. Gender in engineering departments: are there gender differences in interruptions of academic job talks? Soc Sci. 2017;6:29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapporteur KM. National Research Council Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on Advancing Institutional Transformation for Minority Women in Academia. Seeking solutions: maximizing American talent by advancing women of color in academia: summary of a conference. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGee E. Black genius, Asian fail: the detriment of stereotype lift and stereotype threat in high-achieving Asian and Black STEM students. AERA Open. 2018;4:233285841881665. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams JC, Li S, Rincon R, Finn P. Climate control: gender and racial bias in engineering. Center for Worklife Law & Society of Women Engineers; San Francisco, CA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1363–1369. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassouneh D, Lutz KF, Beckett AK, Junkins EP, Horton LL. The experiences of underrepresented minority faculty in schools of medicine. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:24768. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.24768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrmann SD, Adelman RM, Bodford JE, Graudejus O, Okun MA, Kwan VSY. The effects of a female role model on academic performance and persistence of women in STEM courses. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2016;38:258–268. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drury BJ, Siy JO, Cheryan S. When do female role models benefit women? The importance of differentiating recruitment from retention in STEM. Psychol Inq. 2011;22:265–269. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert WM, Wells MT, Cipriano MF, Sneva JN, Morris JA, Golightly LM. Career choices of underrepresented and female postdocs in the biomedical sciences. eLife. 2020:9. doi: 10.7554/elife.48774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, Karbeah J, Kozhimannil KB. Naming institutionalized racism in the public health literature: A systematic literature review. Public Health Reports. 2018;133:240–249. doi: 10.1177/0033354918760574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey WB. Higher education and diversity: ethical and practical responsibility in the academy 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stack M. Academic stars and university rankings in higher education: impacts on policy and practice. Pol Rev Higher Educ. 2019;4:4–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iverson SV. Camouflaging power and privilege: a critical race analysis of university diversity policies. Educ Admin Q. 2007;43:586–611. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate SA, Bagguley P. Building the anti-racist university: next steps. Race Ethnicity Educ. 2016;20:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA. Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. eLife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/elife.21393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nittrouer CL, Hebl MR, Ashburn-Nardo L, Trump-Steele RCE, Lane DM, Valian V. Gender disparities in colloquium speakers at top universities. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:104–108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708414115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalejta RF, Palmenberg AC. Gender parity trends for invited speakers at four prominent virology conference series. J Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00739-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casadevall A, Handelsman J. The Presence of Female Conveners Correlates with a Higher Proportion of Female Speakers at Scientific Symposia. mBio. 2014:5. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00846-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein RS, Voskuhl R, Segal BM, Dittel BN, Lane TE, Bethea JR, Carson MJ, Colton C, Rosi S, Anderson A, Piccio L, Goverman JM, Benveniste EN, Brown MA, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Harris TH, Cross AH. Speaking out about gender imbalance in invited speakers improves diversity. Nat Immun. 2017;18:475–478. doi: 10.1038/ni.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broderick NA, Casadevall A. Gender inequalities among authors who contributed equally. eLife. 2019:8. doi: 10.7554/elife.36399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimery KM, Mellon MJ, Rinehart SM. Publishing in the accounting journals: Is there a gender bias? J Bus Econ Res. 2011:2. doi: 10.19030/jber.v2i4.2872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helmer M, Schottdorf M, Neef A, Battaglia D. Gender bias in scholarly peer review. eLife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/elife.21718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox CW, Paine CET. Gender differences in peer review outcomes and manuscript impact at six journals of ecology and evolution. Ecol Evol. 2019;9:3599–3619. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert JR. Is there gender bias in JAMAs peer review process? JAMA. 1994;272:139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okonofua BA. I am blacker than you. SAGE Open. 2013;3 215824401349916. [Google Scholar]

- 38.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickham H. Tidyverse: easily install and load the “Tidyverse” 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilke CO. Cowplot: streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for “ggplot2.” 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allaire J, Horner J, Xie Y, Marti V, Porte N. Markdown: “Markdown” rendering for r 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Y, Allaire J, Grolemund G. R markdown: the definitive guide. Chapman; Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, Florida: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allaire J, Xie Y, McPherson J, Luraschi J, Ushey K, Atkins A, Wickham H, Cheng J, Chang W, Iannone R. Rmarkdown: dynamic documents for r 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie Y. Knitr: A comprehensive tool for reproducible research in R. In: Stodden V, Leisch F, Peng, RD, editors. Implementing reproducible computational research. Chapman; Hall/CRC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie Y. Knitr: a general-purpose package for dynamic report generation in r 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grolemund G, Wickham H. Dates and times made easy with lubridate. J Stat Software. 2011;40:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wickham H, Bryan J. Readxl: Read excel files 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ooms J. Pdftools: text extraction, rendering and converting of PDF documents 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wickham H. Scales: scale functions for visualization 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuwirth E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer palettes 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Survey of doctorate recipients, survey year 2017. National Science Foundation; Alexandria, VA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989 doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9097-4. 1989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics Directorate for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences. Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering. National Science Foundation; Alexandria, VA: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allagnat L, Berghmans S, Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Hanafi S, Herbert R, Huggett S, Tobin S. Gender in the global research landscape. Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armstrong MA, Jovanovic J. Starting at the crossroads: intersectional approaches to institutionally supporting underrepresented minority women stem faculty. J Women Minorities Sci Engineer. 2015;21:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu YJ. Gender Disparity in STEM Disciplines: a study of faculty attrition and turnover intentions. Res Higher Educ. 2008;49:607–624. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whittaker JA, Montgomery BL, Martinez Acosta VG. Retention of underrepresented minority faculty: strategic initiatives for institutional value proposition based on perspectives from a range of academic institutions. J Undergrad Neurosci Educ. 2015;13:A136–A145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson MDL. mSphere of influence: hiring of underrepresented minority assistant professors in medical school basic science departments has a long way to go. mSphere. 2019:4. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00599-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loftus GR. Comparison of recognition and recall in a continuous memory task. J Experim Psychol. 1971;91:220–226. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson J. Designing with the mind in mind. Elsevier; 2014. Recognition is easy; recall is hard; pp. 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baucom R, Duffy M. DiversifyEEB. 2019. https://diversifyeeb.com.

- 62.Duffy M, McNeil AJ. DiversifyChemistry. 2019 https://diversifychemistry.com. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hagan AK, Pollet RM. DiversifyMicrobiology. GitHub repository. 2019. https://github.com/diversifymicrobiology.github.io; GitHub.

- 64.Hagan AK, Pollet RM. DiversifyImmunology. GitHub repository. 2019. https://github.com/diversifyimmunology.github.io; GitHub.