Abstract

Tissue engineering scaffolds are intended to provide mechanical and biological support for cells to migrate and engraft and ultimately regenerate the tissue. Development of scaffolds with sustained delivery of growth factors and chemokines would enhance the therapeutic benefits, especially in wound healing. In this study, we incorporated our previously designed therapeutic particles, composed of fusion of elastin-like peptides (ELPs) as the drug delivery platform to keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), into a tissue scaffold, Alloderm. The results demonstrated that sustained KGF-ELP release was achieved and the bioactivity of the released therapeutic particles was shown via cell proliferation assay, as well as a mouse pouch model, where higher cellular infiltration and vascularization were observed in scaffolds functionalized with KGF-ELPs.

Keywords: Elastin-like polypeptides, keratinocyte growth factor, tissue scaffolds, mouse pouch model, Alloderm

Introduction

The management of wound healing and subsequent scarring severely burden the US healthcare system with an overall annual cost of $25–50 billion, and 5% of the total cost of Medicare and Medicaid (Fife, Carter, & Walker, 2010; Sen et al., 2009; Vowden & Vowden, 2016). Over the last several decades, the biology of wound healing has been extensively studied and growth factors have been identified as critical signaling molecules that control migration, proliferation and cellular differentiation over the tissue regeneration process (Broughton, Janis, & Attinger, 2006; Greenhalgh, 1996; Werner & Grose, 2003). Thus, growth factor-based therapies appeared as an attractive strategy to stimulate angiogenesis and re-epithelialization and accelerate wound healing (Barrientos, Brem, Stojadinovic, & Tomic-Canic, 2014). However numerous clinical trials remained ineffective due to issues associated with the rapid clearance and short half-life of the growth factors in the harsh microenvironment of proteolytic wound sites (Mast & Schultz, 1996).

Dermal tissue scaffolds, such as Alloderm have been developed to promote dermis regeneration. Cell types crucial for wound healing have been infused into these scaffolds (e.g. Dermagraft) for increased efficacy. However, success has been limited. Moreover, the inclusion of living cells introduces a host of safety and regulatory issues (Berthiaume, Maguire, & Yarmush, 2011; Marston, 2004; Wong & Gurtner, 2012). Alternatively, many growth factor-based approaches have been investigated, such as the direct incorporation into skin equivalents, however, none of them are widely used. Most cytokines do not express well recombinantly in prokaryotic hosts, leading to costly production requirements (Grazul-Bilska et al., 2003). In addition, highly proteolytic wound environment results in rapid loss of biological activity and require repeated applications (Barrientos, Stojadinovic, Golinko, Brem, & Tomic-Canic, 2008). For these reasons, a delivery platform which ensures a prolonged release of the growth factor during the entire regeneration process and which is compatible with the existing products on the market for easy clinical translation would be of great interest (Hoffman, 2013).

In this study, we introduce a dermal scaffold functionalized with a protein-based biomaterial, based on elastin-like polypeptides (ELP). ELPs are repetitive chains of pentapeptide amino acids typically composed of [VPGXG]n, where X and n represent any amino acid except proline and the number of repeats, respectively. ELPs can undergo temperature dependent, reversible phase transition between their soluble form and aggregated particle form above their transition temperature. This characteristic thermal property of ELPs makes them suitable for various biomedical applications including regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, as particle formation can be achieved in-situ at physiologically relevant temperatures allowing for sustained release of the fusion protein of interest. ELP particles have been shown to be non-toxic, to not induce an immune response and to provide excellent biocompatibility, presenting themselves as convenient biomaterials (Chilkoti, Christensen, & MacKay, 2006; Floss, Schallau, Rose-John, Conrad, & Scheller, 2010; Yeboah, Cohen, Rabolli, Yarmush, & Berthiaume, 2016). Fusion of growth factors and other cytokines of interest to ELP chains at the genetic level can lead to therapeutic particles capable of sustained delivery of the therapeutic moiety.

Previously, we have genetically fused keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) to an ELP sequence composed of 120 repeats (Devalliere et al., 2017) and showed that keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) fused to ELP accelerated wound healing, compared to recombinant KGF or ELP alone. Fusion of growth factors to ELP sequences has multiple advantages over the delivery of therapeutic protein alone, including prolonged circulation times due to protection from proteolytic enzymes (Yeboah, Cohen, Rabolli, et al., 2016). In this study, we incorporated KGF-ELP fusion particles into a clinically approved tissue scaffold (Alloderm) to improve upon the delivery platform, resulting in sustained delivery of KGF, and to functionalize commercially available products at the same time. The particle release profile as well as the biological activity of released KGF-ELP were studied via in vitro cell proliferation assays and in vivo animal studies. A pouch model was employed in mice whereby KGF-ELP-incorporated scaffolds were implanted into a subcutaneous pouch. Histology analysis was performed on Alloderm sections to assess cellular infiltration and vascularization profile whereby KGF-ELP group performed superior compared to ELP alone and recombinant KGF groups. The results of this study demonstrate that protein-based biomaterials can be combined with commercially available grafts to improve therapeutic benefits, with potential applications in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids, Cells and Chemicals.

An ELP construct of 120 pentapeptide repeats of VPGVG was fused to human KGF gene in the pET24a(+) backbone as described before (Devalliere et al., 2017). Terrific broth media for protein expression, DMEM and Williams’ E (WE) Medium, Pierce BCA protein assay kit and CyQUANT cell proliferation assay were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Alloderm regenerative tissue matrix (size: 8 × 16 cm & thickness: 1.04 – 2.28 mm) was purchased from Lifecell. For release studies, porcine pancreas elastase was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Collagenase from C. histolyticum and lysozyme from chicken egg white were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). A-431 epithelial cell line, responsive to KGF, was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Recombinant KGF was purchased from BioVision (Milpitas, CA). Anti-CD31 antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). All other reagents and materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated.

Protein Expression and Purification.

ELP construct by itself and fused to KGF (KGF-ELP) were expressed in 1 L of sterilized Terrific Broth supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and inoculated with 8 mL overnight culture. The cell cultures were incubated at 37 °C overnight while shaking and protein expression was achieved via leaky expression of the T7 promoter present in the pET24a(+) plasmid. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min and resuspended in 30 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per L of culture. Cells were lysed via sonication with an ultrasonication probe in ice bath. The lysed cell suspensions were centrifuged at 15000 g for 40 min and the soluble fraction was collected. The ELP and KGF-ELP were purified by the inverse transition cycling (ITC) method as described elsewhere (Hassouneh, Christensen, & Chilkoti, 2010). In summary, both samples were incubated at 40 °C for 15 min following NaCl addition to a final concentration of 1 M. The precipitated proteins were collected in the pellet following centrifugation at 13000 g for 15 min at 37 °C. The supernatants containing E.coli contaminants were discarded. The pellets were resuspended in 5 mL of ice cold PBS and centrifuged at 13000 g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove any insoluble contaminants. This cycle of warm/cold spins was repeated 4 times. Protein concentrations were determined via NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 1490 cm−1 M−1 and 38765 cm−1 M−1 for ELP and KGF-ELP, respectively.

Dynamic Light Scattering and Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Dynamic light scattering analysis was performed via a temperature controlled Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., United Kingdom) instrument. The temperature of KGF-ELP in PBS was changed from 25 °C to 45 °C, where 3 readings were taken at 1 °C increments and the data were plotted as mean ± SEM. The transition temperature was determined by recording the change in particle size, where aggregated particles with diameters in nm range were observed above 33 °C. Mean effective aggregate diameter was also determined via Zetasizer Nano Software and plotted as normalized intensities as a function of temperature. The readings were taken in triplicate. For particle imaging, a 1 μM solution of KGF-ELP was prepared and a standard negative staining procedure was followed. Briefly, the sample was adsorbed to a carbon coated grid (EMS, Hatfield, PA), following incubation at 37 °C for 10 min. The grid was then stained with 0.75% uranyl formate and examined via a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA Inc., Peabody, MA). The images were recorded with an AMT 2k CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ).

ELP Particle Incorporation into Alloderm and Cumulative Release Studies.

Circular disks of scaffolds 6 mm in diameter were obtained via sterile punches from Acuderm Inc. (Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA). For particle incorporation, the scaffolds were incubated in ELP, KGF or KGF-ELP solutions for 30 min at 37 °C. Alloderm and ELP-incorporated Alloderm pieces were placed into eppendorf tubes with 100 μL cell culture media or 100 μL cell culture media supplemented with 125 U mL−1 collagenase, 1 mU mL−1 elastase and 40 U mL−1 lysozyme. These concentrations were determined based on our previous study with KGF-ELP (Dooley, Devalliere, Uygun, & Yarmush, 2016b). The media was replaced with fresh media every 24 hr for a month. Protein concentration in each sample was determined via Pierce BCA protein assay kit and cumulative protein release was plotted over time. The amount of protein in the control group (Alloderm only) was subtracted from the experimental group (Alloderm + KGF-ELP) in order to determine the amount of released KGF-ELP. The experiments were performed in triplicates.

Cell Proliferation Assay.

ELP-incorporated Alloderm pieces were incubated in 100 μL of serum-free DMEM for 4 weeks. 15 μL of this media was mixed with 185 μL of fresh serum-free DMEM media. KGF responsive epithelial cell line A-431 were grown in DMEM media supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 % L-glutamine, 1 % penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were cultured in T-75 flasks in DMEM. Upon reaching 85–90 % confluency, cells were trypsinized and plated in a 96 well plate with a seeding density of 10,000 cells/well. Eight hours following seeding, media was changed to DMEM without serum. After overnight serum starvation, 200 μL of conditioned media was added to cells. For the positive control group (recombinant KGF), cells were incubated with 0.5 μM KGF solutions in serum-free DMEM. Cells were cultured for 48 hr, at 37 °C and at 5 % CO2. Cell proliferation was quantified via CyQUANT assay following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 100 μL dye reagent in HBSS buffer was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr. Fluorescence was measured on a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 528 nm, respectively. The results of each group were normalized to the one of the untreated control group.

In vivo Mice Pouch Model.

C57BL/6N wild-type mice from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were used for the in vivo studies at the age of 6 weeks. A day prior to the surgery, the backs of the mice were shaved, and a depilatory cream was applied to remove the remaining hair. On the day of the surgery, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). The backs of the mice were cleaned with alcohol and povidone-iodine pads (Dynarex, Orangeburg, NY) to prepare the dorsal skin. A full-thickness incision was made to the panniculus carnosus of mice to create an approximately 1 cm2 subcutaneous pouch and the tissue scaffold of approximately 0.3 cm2 (incubated either with just PBS, ELP, recombinant KGF or KGF-ELP) was transplanted into this pouch, with the reticular side of Alloderm facing the muscle layer (Fig. S2) (Cherubino et al., 2016; Izumi, Feinberg, Terashi, & Marcelo, 2003; Kuo et al., 2018). The pouch was sutured closed and covered with Tegaderm dressing (3M, St. Paul, MN). Five scaffolds were implanted for each group. Following the surgery, the animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines set by the Committee on Laboratory Resources, National Institutes of Health. The surgical protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Massachusetts General Hospital. The mice were sacrificed after 15 days and the tissue scaffolds were harvested for histological analysis.

Histology Analysis.

Harvested skin scaffolds were fixated in 3.7 % formaldehyde. The samples were cut in the middle, embedded, and sectioned along the diameter line at 5 μM. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain for general morphological assessment and for quantification of cellular infiltration. To determine the cellular infiltration, 5 sections were analyzed for each experimental group. In each section, the distance of cells that are farthest from the surface was determined using NDP view software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ) where a total of 75 measurements were performed per group. Total cell number was determined by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), using the H&E stained sections (5 sections per group were analyzed). The number of nuclei present up to 600 μm depth of each section was determined. The 600 μm limit was chosen considering the cell penetration depth measurements to include the majority of cells that penetrated the constructs. In addition to total cell number, the number of cells was determined with respect to the Alloderm depth where 3 zones (namely, surface (top) (0–200 μm), middle (200–400 μm) and deep (bottom) (400–600 μm)) were examined (Fig. S3). The number of cells in each zone was counted using ImageJ and represented as mean ± SEM. Three region of interests (ROIs) (600×600 μm) were analyzed per section through dividing each ROI to the respective zones (9 regions per sample). Additional sections of each group were stained with anti CD31 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) as an endothelial cell marker. Complete tube formation was assessed in each sample (n=5) of PBS, ELP, recombinant KGF and KGF-ELP groups and quantified by counting stained hollow circles lined by endothelial cells.

Statistical Analysis.

GraphPad Prism software (Graphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. For cell proliferation assay (n=3), one-way ANOVA was performed with Dunnett’s correction. In the analysis of the results of the in vivo study (n=5) (cellular infiltration & blood vessel formation), PBS, ELP, recombinant KGF and KGF-ELP groups were compared via one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction. For all analyses, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant and the results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Particle Characterization.

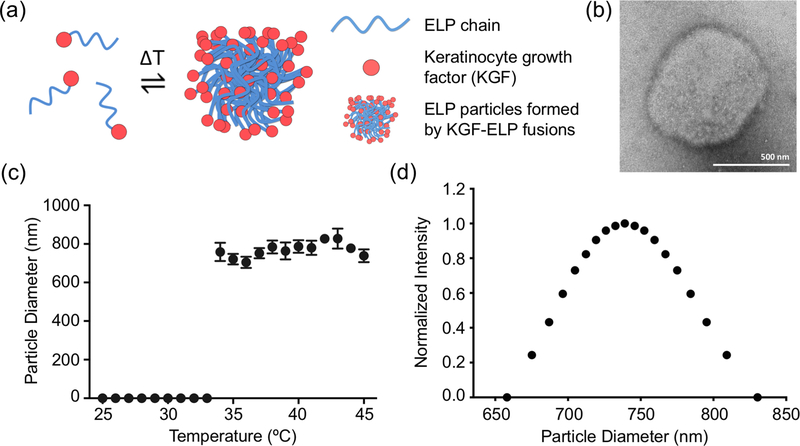

ELP particles have been used as efficient drug delivery platforms. Previously, we have genetically fused keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) to an ELP sequence composed of 120 repeats (Devalliere et al., 2017). KGF-ELP particles are expressed in E.coli and easily purified via inverse transition cycling. As demonstrated in Figure 1a, KGF-ELP amino acid chains form aggregated particles above their transition temperature. Figure 1b shows a representative TEM image of aggregated KGF-ELP particles. Dynamic light scattering analysis demonstrated that KGF-ELP fusions formed particles with diameters in 650–800 nanometer range above 33 °C (Fig. 1c). The particle size distribution is shown in Figure 1d, where the average particle diameter is found to be 769 nm. These findings confirmed the results of our previous study (Devalliere et al., 2017). As the next step, we probed the use of KGF-ELPs in combination with clinically approved tissue scaffolds; and assessed their activity in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1. KGF-ELP Particle Characterization.

KGF-ELP particles were characterized for their particle size and transition temperature. (a) A cartoon demonstrating the phase transition of KGF-ELP chains, which form aggregated particle above their transition temperature. (b) Representative transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of aggregated KGF-ELPs. Scale bar: 500 nm. (c) The transition temperature of KGF-ELP is determined to be 33 °C via dynamic light scattering, where particle size was recorded over a temperature range of 25 °C - 45 °C. The data obtained from three readings are plotted as the change in particle size over temperature. The results are reported as mean ± SEM. (d) The particle size distribution data is plotted as normalized intensity over particle diameter in nm.

Release Profile of KGF-ELP from Tissue Scaffolds.

Alloderm disks were incubated with KGF-ELP solution (in PBS) to allow for particle incorporation via absorption. Following particle incorporation, scaffolds were incubated in cell culture media for over a month, where media was replaced with fresh media every day to determine the cumulative release profile of KGF-ELP. As shown in Figure 2, complete release was achieved after 32 days and 137.5 ± 1.5 μg KGF-ELP was incorporated into the scaffolds. Initially, KGF-ELP incubation included 180 μg of protein per Alloderm disk. Thus, the incorporation efficiency was 75 %. The same experiment was repeated in media supplemented with enzymes responsible for protein degradation, which are known to be up-regulated in the wound environment (Cutting, 2003; Krejner & Grzela, 2015; Nessler, Puchala, Chrapusta, Nessler, & Drukala, 2014). Cell culture media was supplemented with 125 U mL−1 collagenase, 1 mU mL−1 elastase and 40 U mL−1 lysozyme and release profile in the presence of these proteases are shown in Figure 2b, whereby total protein release was achieved at the end of 16 days. This result showed that total particle release could be expected to be complete within this time frame in vivo in the presence of these proteolytic enzymes.

Figure 2. KGF-ELP Release Profile and Bioactivity.

Following the incorporation of KGF-ELP into Alloderm, release profiles were assessed; and the activity of the released therapeutic ELP particles were tested. (a) Tissue scaffolds were incubated in cell culture media for 4 weeks. KGF responsive A431 cells were incubated with this conditioned media and cell proliferation was assessed via CyQUANT assay. (b) Cumulative release profile in cell culture media showed that total protein release occurred over 32. Same experiment was repeated in cell culture media supplemented with proteolytic enzymes typically present in the wound environment. (c) Four groups were tested for the bioactivity of released KGF-ELP: Non-treated cells, cells incubated with conditioned media obtained from the incubation of Alloderm in cell culture media following absorption of either control group (PBS only) or KGF-ELP; and cells incubated with 0.5 μM recombinant KGF. The results are reported as mean ± SEM, n = 3, **** = p < 0.0001.

In vitro Biological Activity of the Released KGF-ELP.

In order to assess the bioactivity of the released particles, KGF-ELP incorporated Alloderm disks were incubated in cell culture media for 4 weeks and this media was used as the conditioned media in cellular assays (Fig. 2). This way, the bioactivity of released particles was investigated over a time course of 4 weeks. The estimated concentration for KGF-ELP group (based on the release data) was 1.41 μM. KGF responsive A431 cells were serum starved overnight and treated with these conditioned media for 48 hours. Media from Alloderm without KGF-ELP group (PBS control) was included in the experiment as an additional control group in addition to non-treated cells; and 0.5 μM and 1 μM recombinant KGF served as the positive controls (Fig. 2c, Fig. S1). Proliferation was assessed via CyQUANT assay as described in Materials and Methods section and all data were normalized to non-treated cell group. As demonstrated in Figure 2c, statistically significant increase in cell proliferation was observed in KGF-ELP (5.3 ± 0.1 fold, p < 0.0001), and recombinant KGF groups (6.8 ± 0.1 fold, p < 0.0001), compared to non-treated cells. In addition, the KGF-ELP group achieved higher proliferation compared to the PBS group (p < 0.0001). No statistically significant difference was observed between non-treated cells and PBS group. In addition, cell proliferation was saturated at 0.5 μM KGF as indicated in Figure S1, as no difference between 0.5 μM and 1 μM groups was observed.

In vivo Biological Activity of KGF-ELP via Mouse Pouch Model.

As the next step in the study, we assessed the activity of KGF-ELP incorporated tissue scaffolds in vivo. Four experimental groups were assessed: tissue scaffolds incubated with PBS, ELP, recombinant KGF and KGF-ELP particles. We examined the effect of these groups on cellular infiltration and vascularization in tissue scaffolds. Alloderm disks were treated the same way as described above in order to achieve scaffolds functionalized with ELP, KGF and KGF-ELP. Five animals were used per group. Mouse pouch model was used as the study platform (Cherubino et al., 2016; Izumi et al., 2003; Kuo et al., 2018), where the Alloderm disks were implanted into a subcutaneous pouch between the skin and muscle layers (Fig. S2). The scaffolds were removed after 15 days and analyzed via histology.

H&E staining showed that cellular infiltration was highest in the KGF-ELP group (Fig. 3). Representative images of all four groups are shown in Figure 3a. This observation was quantified by measuring the total number of cells per group using NDP view and ImageJ software. Statistically significant difference was only observed for the KGF-ELP group (2173 ± 196 cells per mm2, p < 0.0001) as demonstrated in Figure 3b, followed by recombinant KGF group (1493 ± 52 cells per mm2), ELP alone and PBS groups (1106 ± 91 cells per mm2 and 1219 ± 55 cells per mm2, respectively). In addition, we investigated the distribution of cell population along the depth of the tissue scaffold to assess the infiltration distance. For this purpose, we considered 3 different sections (top, middle, bottom), each 200 μm in depth (Fig. 3b, Fig. S3). For all sections, similar results were observed where the highest cell number was present in the KGF-ELP group (top: 1,637 ± 138 cells per mm2, 0.001 < p < 0.005; middle: 435 ± 44 cells per mm2, p < 0.0001; bottom: 101 ± 21 cells per mm2, 0.005 < p < 0.010). ELP alone and recombinant KGF groups did not show statistical significance compared to the PBS group, although KGF group contained the second highest number of cells in each section.

figure 3. In vivo Bioactivity of Released KGF-ELP: Cellular Infiltration.

Alloderm grafts incorporated with the control group PBS, ELP alone, recombinant KGF or KGF-ELP were transplanted in mice and cellular infiltration was assessed after 15 days via H&E staining. (a) Representative H&E images of tissue scaffolds. Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) Quantification of total number of infiltrated cells per mm2. The number of cells in different sections of tissue scaffolds (top 200 μM, middle 200 μM and bottom 200 μM) was also counted per group as explained in Figure S3. The results are reported as mean ± SEM, n = 5, ** = 0.005 < p < 0.010, *** = 0.001 < p < 0.005, **** = p < 0.0001.

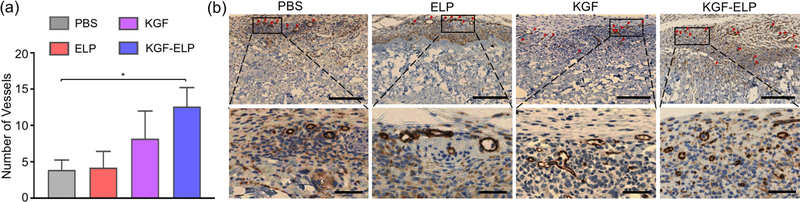

Additional immunohistochemistry analysis was performed based on the promising results of the H&E staining. Tissue sections from Alloderm disks were stained with CD31 antibody to mark endothelial cells. The number of vessels was counted per each sample (n=5). As shown in Figure 4a, highest vascularization was observed in the KGF-ELP group (12.6 ± 2.6 per section) followed by recombinant KGF group (8.2 ± 3.7 per section), ELP alone group (4.2 ± 2.2 per section) and PBS group (3.9 ± 1.3 per section). Only KGF-ELP group was found to have a significantly higher number of vessels lined by endothelial cells (p < 0.05). Representative section images are shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4. In vivo Bioactivity of Released KGF-ELP: Vascularization.

Tissue sections from Alloderm grafts were stained with CD31 as the endothelial cell marker. (a) Quantification of number of vessels in scaffolds functionalized with PBS control, ELP alone, recombinant KGF and KGF-ELP. The results are reported as mean ± SEM, n = 5, * = p < 0.05. (b) Representative images of CD31 stained sections of each group. Tubular formations are indicated with red arrows in the top panel (scale bar: 250 μm). Zoomed sections are shown in the bottom panel to allow for a closer visual (scale bar: 50 μm).

Discussion

There is a growing interest in using scaffolds for a variety of applications in tissue engineering including use of hydrogels for cell proliferation and differentiation; as well as use of porous biomaterials for new tissue growth. Various grafts were explored for use in wound healing studies, which can serve as matrices for cellular infiltration and eventual tissue regeneration. Clinically approved products were developed, such as the acellular dermal scaffold Alloderm, which are commercially available.

Previously, we have shown that ELP nanoparticles composed of ELP chains fused to therapeutic moieties and growth factors protect the therapeutic cargo from degradation, allowing for sustained delivery while maintaining the biological activity in vitro and in vivo, resulting in enhanced efficacy compared to unfused therapeutics (e.g. recombinantly produced counterparts) (Devalliere et al., 2017; Dooley, Devalliere, Uygun, & Yarmush, 2016a; Koria et al., 2011b; Yeboah, Cohen, Faulknor, et al., 2016). An ELP sequence of 120 repeats was shown to increase stability of the fused protein and to enhance the performance of the therapeutic protein (Dooley et al., 2016b). In this study, we built upon our previous work with ELP particles decorated with a growth factor (KGF) and showed that tissue scaffolds can be functionalized with these particles. Dermal tissue scaffolds have been developed to promote dermis regeneration and it has been shown that the addition of growth factors can have beneficial effects on skin graft take (Akita, Akino, Imaizumi, & Hirano, 2005). We incorporated KGF-ELP into a tissue scaffold, Alloderm, and assessed the release profile as well as in vitro and in vivo bioactivity of the released therapeutic particles. The pore size of tissue scaffolds, such as Alloderm, is in the range of micrometers (> 30 μm) (Capito, Tholpady, Agrawal, Drake, & Katz, 2012). As such, the temperature dependent particle transition of KGF-ELP, with a transition temperature of 33 °C, is to be preserved during the incorporation process since KGF-ELP particle size is shown to be less than 1 μm (Figs. 1b–d).

We employed absorption as the incorporation method, whereby Alloderm disks were incubated with ELP alone, recombinant KGF or KGF-ELP solutions in PBS. Following the incubation, they were either placed into individual containers with media for the release profile experiments and in vitro cellular assays; or were directly used in animal studies. Alloderm disks incubated with PBS only were used as the control group and cumulative release profiles were obtained by subtracting the released protein amount in the control groups from the experimental KGF-ELP groups. The release experiments showed that 137.5 ± 1.5 μg of KGF-ELP was incorporated into tissue scaffolds (Fig. 2). The cumulative release graphs indicated that sustained KGF-ELP release was achieved over 32 days. In order to mimic the wound environment, we supplemented the media with proteolytic enzymes and observed that the time frame of total protein release decreased to 16 days due to faster protein degradation.

Once the incorporation and sustained release of KGF-ELP was confirmed, we investigated the bioactivity of the released particles. Scaffolds functionalized with KGF-ELP were incubated in media for 4 weeks, which was chosen based on the results of the release studies (Fig. 2). This conditioned media was mixed with fresh media and used in keratinocyte proliferation assays. Similar to release profile experiments, Alloderm disks incubated with PBS only were used as the control group in addition to non-treated cells. As the positive control, cells were incubated with 0.5 μM recombinant KGF, which was chosen based on the results of our previous study (Devalliere et al., 2017). The results were normalized against the non-treated control group. As expected, PBS group did not enhance keratinocyte proliferation, whereas the KGF-ELP group resulted in a nearly 6-fold increase in cell proliferation. These results demonstrated that the released KGF-ELP particles retained their biological activity.

As the next step, we examined the effect of KGF-ELP presence and release on cellular infiltration and vascularization in tissue scaffolds. Previously, we have attempted to employ an excisional wound model and to suture in the tissue scaffolds on the back of mice. However, these attempts did not succeed mainly due to displacement of Alloderm disks after a few days, even with extensive suturing. We believe that these attempts mostly failed as a result of the difference in the thickness of Alloderm scaffolds compared to the skin thickness of wild-type C57BL/6N mice. Thus, we employed an established pouch model instead as an initial assessment method to investigate the in vivo bioactivity of the functionalized tissue scaffolds (Cherubino et al., 2016; Izumi et al., 2003; Kuo et al., 2018). In this model, the scaffolds were grafted into a subcutaneous pouch on the back of mice created by a full-thickness incision. We focused on four groups: PBS, ELP alone, recombinant KGF and KGF-ELP. Tissue scaffolds incubated with equal molarities of these groups were implanted in mice. The grafts were retrieved and analysed via histology at the end of 2 weeks.

The total number of cells infiltrated into the scaffold was assessed. Alloderm disks functionalized with KGF-ELP particles had the highest number of cells (Fig. 3). This result indicated that the growth factor incorporation improved the cell migration and retrieval into the scaffold. In addition, we investigated the infiltration depth by quantifying the number of cells in the top, middle and bottom 200 μm sections of the Alloderm disk. As expected, the number of cells decreased along the depth of the scaffold in all groups. The KGF-ELP group had a significantly higher number of cells in all sections, compared to PBS control group. The difference in cell numbers was not statistically significant for ELP alone or KGF groups. These results showed that incorporation of KGF-ELP into Alloderm grafts improved the overall cellular infiltration, as well as infiltration depth; and KGF-ELP performed better over its recombinant counterpart in agreement with our previous studies, where we demonstrated that recombinant KGF had no beneficial impact in in vivo studies, most likely due to rapid degradation of the free form of the growth factor (Devalliere et al., 2017; Koria et al., 2011a).

KGF is a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family. Five members of this family have been shown to promote new blood vessel growth (Gillis et al., 1999). There have been studies showing that KGF (FGF-7) acts on endothelial cells of small blood vessels and is an inducer of neovascularization by stimulating capillary endothelial cell proliferation and migration (Gillis et al., 1999). Other in vitro work showed that KGF contributes to angiogenesis by promoting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion by endothelial cells as well as a urokinase type plasminogen activator necessary for vascularization (Barrientos et al., 2008; Johnson & Wilgus, 2014; Niu et al., 2007). Based on these previous studies, we assessed the vascularization within the tissue scaffolds via CD31 staining to mark endothelial cells and found out that the KGF-ELP group featured more vascularization compared to the PBS, ELP alone and recombinant KGF group (Fig. 4a). It should be emphasized that only vessels sectioned transversally were recognized via immunohistochemistry analysis. These results served as additional evidence that scaffolds functionalized with KGP-ELP enhanced graft uptake by promoting vascular ingrowth.

Conclusion

Previously, we have shown that fusion of therapeutics to elastin-like polypeptides increases their efficacy by achieving sustained delivery and protection from proteases present at the wound site. In this study, we built upon our previous studies and showed that therapeutic biomaterials composed of ELPs and a growth factor, KGF, can be incorporated into tissue scaffolds. The released KGF-ELP particles promoted keratinocyte proliferation, demonstrating the retainment of biological activity. In addition, KGF-ELP functionalized tissue scaffolds demonstrated higher cellular infiltration and vascularization in vivo. The findings of these studies showed that KGF-ELP particles performed superior compared to recombinant KGF, demonstrating the advantage of the ELP-based delivery platform. These results suggest that combining therapeutic KGF-ELP particles with dermal equivalents can increase the clinical translatability of these biomaterials. More broadly, this technology can be applied to any therapeutic protein of interest, increasing its potential for utilization in regenerative medicine applications, where the use of both the tissue scaffold and the growth factor delivery platform results in smart, multi-functional products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shriners Hospitals for Children research grants # 85210 (M.L.Y.) and # 85105 (B.E.U.). B.B. was supported by the NIH Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Award F32 (F32EB026916) and the Shriners Hospitals for Children postdoctoral fellowship grant, award no: 84311. J.D. was supported by the Shriners Hospitals for Children postdoctoral fellowship grant, award no: 84295. The authors would like to acknowledge the Electron Microscopy Facility at Harvard Medical School, Shriners Proteomics & Genomics Core Facilities and Translational Regenerative Medicine Shared Facility at Shriners Hospitals for Children in Boston.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

The supplementary information includes supplementary figures: Cell Proliferation with Recombinant KGF, Mouse Pouch Model and Representative H&E Image of an Alloderm Tissue Section.

References

- Akita S, Akino K, Imaizumi T, & Hirano A (2005). A basic fibroblast growth factor improved the quality of skin grafting in burn patients. Burns, 31(7), 855–858. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16199295. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos S, Brem H, Stojadinovic O, & Tomic-Canic M (2014). Clinical application of growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen, 22(5), 569–578. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24942811. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, & Tomic-Canic M (2008). Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen, 16(5), 585–601. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19128254. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthiaume F, Maguire TJ, & Yarmush ML (2011). Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: history, progress, and challenges. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng, 2, 403–430. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22432625. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton G 2nd, Janis JE., & Attinger CE. (2006). The basic science of wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg, 117(7 Suppl), 12S–34S. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16799372. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000225430.42531.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capito AE, Tholpady SS, Agrawal H, Drake DB, & Katz AJ (2012). Evaluation of host tissue integration, revascularization, and cellular infiltration within various dermal substrates. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 68(5), 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubino M, Valdatta L, Balzaretti R, Pellegatta I, Rossi F, Protasoni M, … Gornati R (2016). Human adipose-derived stem cells promote vascularization of collagen-based scaffolds transplanted into nude mice. Regenerative Medicine, 11(3), 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilkoti A, Christensen T, & MacKay JA (2006). Stimulus responsive elastin biopolymers: Applications in medicine and biotechnology. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 10, 652–657. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17055770. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting KF (2003). Wound exudate: Composition and functions. British Journal of Community Nursing, 8, 1–9. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2003.8.Sup3.11577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalliere J, Dooley K, Hu Y, Kelangi SS, Uygun BE, & Yarmush ML (2017). Co-delivery of a growth factor and a tissue-protective molecule using elastin biopolymers accelerates wound healing in diabetic mice. Biomaterials, 141, 149–160. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28688286. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K, Devalliere J, Uygun BE, & Yarmush ML (2016a). Functionalized Biopolymer Particles Enhance Performance of a Tissue-Protective Peptide under Proteolytic and Thermal Stress. Biomacromolecules, 17(6), 2073–2079. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27219509. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K, Devalliere J, Uygun BE, & Yarmush ML (2016b). Functionalized Biopolymer Particles Enhance Performance of a Tissue-Protective Peptide under Proteolytic and Thermal Stress. Biomacromolecules, 17, 2073–2079. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27219509. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife CE, Carter MJ, & Walker D (2010). Why is it so hard to do the right thing in wound care? Wound Repair Regen, 18, 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floss DM, Schallau K, Rose-John S, Conrad U, & Scheller J (2010). Elastin-like polypeptides revolutionize recombinant protein expression and their biomedical application. Trends Biotechnol, 28, 37–45. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19897265. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis P, Savla U, Volpert OV, Jimenez B, Waters CM, Panos RJ, & Bouck NP (1999). Keratinocyte growth factor induces angiogenesis and protects endothelial barrier function. Journal of Cell Science, 112, 2049–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazul-Bilska AT, Johnson ML, Bilski JJ, Redmer DA, Reynolds LP, Abdullah A, & Abdullah KM (2003). Wound healing: The role of growth factors. Drugs of Today, 39, 787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh DG (1996). The role of growth factors in wound healing. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 41(1), 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassouneh W, Christensen T, & Chilkoti A (2010). Elastin-like polypeptides as a purification tag for recombinant proteins. Curr Protoc Protein Sci, Chapter 6, Unit 6 11. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20814933. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0611s61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman AS (2013). Stimuli-responsive polymers: biomedical applications and challenges for clinical translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 65, 10–16. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23246762. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Feinberg SE, Terashi H, & Marcelo CL (2003). Evaluation of transplanted tissue-enginered oral mucosa equivalents in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Tissue Engineering, 9(1), 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE, & Wilgus TA (2014). Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis in the Regulation of Cutaneous Wound Repair. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle), 3(10), 647–661. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25302139. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koria P, Yagi H, Kitagawa Y, Megeed Z, Nahmias Y, Sheridan R, & Yarmush ML (2011a). Self-assembling elastin-like peptides growth factor chimeric nanoparticles for the treatment of chronic wounds. PNAS, 108(3), 1034–1039. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21193639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009881108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koria P, Yagi H, Kitagawa Y, Megeed Z, Nahmias Y, Sheridan R, & Yarmush ML (2011b). Self-assembling elastin-like peptides growth factor chimeric nanoparticles for the treatment of chronic wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(3), 1034–1039. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21193639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009881108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejner A, & Grzela T (2015). Modulation of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity by hydrofiber-foam hybrid dressing - relevant support in the treatment of chronic wounds. Cent Eur J Immunol, 40(3), 391–394. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26648787. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2015.54605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S, Kim HM, Wang Z, Bingham EL, Miyazawa A, Marcelo CL, & Feinberg SE (2018). Comparison of two decellularized dermal equivalents. J Tissue Eng Regen Med, 12(4), 983–990. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28752668. doi: 10.1002/term.2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston WA (2004). Dermagraft, a bioengineered human dermal equivalent for the treatment of chronic nonhealing diabetic foor ulcer. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 1(1), 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast BA, & Schultz GS (1996). Interactions of cytokines, growth factors, and proteases in acute and chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen, 4(4), 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nessler MB, Puchala J, Chrapusta A, Nessler K, & Drukala J (2014). Levels of plasma matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) in response to INTEGRA(R) dermal regeneration template implantation. Med Sci Monit, 20, 91–96. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24448309. doi: 10.12659/MSM.889135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J, Chang Z, Peng B, Xia Q, Lu W, Huang P, … Chiao PJ (2007). Keratinocyte growth factor/fibroblast growth factor-7-regulated cell migration and invasion through activation of NF-kappaB transcription factors. J Biol Chem, 282, 6001–6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, … Longaker MT. (2009). Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen, 17(6), 763–771. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19903300. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowden P, & Vowden K (2016). The economic impact of hard-to- heal wounds- promoting practice change to address passivity in wound management. Wounds International, 7(2), 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Werner S, & Grose R (2003). Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev, 83, 835–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VW, & Gurtner GC (2012). Tissue engineering for the management of chronic wounds: current concepts and future perspectives. Exp Dermatol, 21(10), 729–734. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22742728. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah A, Cohen RI, Faulknor R, Schloss R, Yarmush ML, & Berthiaume F (2016). The development and characterization of SDF1alpha-elastin-like-peptide nanoparticles for wound healing. J Control Release, 232, 238–247. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27094603. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah A, Cohen RI, Rabolli C, Yarmush ML, & Berthiaume F (2016). Elastin-like polypeptides: A strategic fusion partner for biologics. Biotechnol Bioeng, 113, 1617–1627. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27111242. doi: 10.1002/bit.25998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.