Abstract

Objectives

We describe payor for contraceptive visits 2013 - 2014, before and after Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in a large network of safety net clinics. We estimate changes in the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits and the independent associations of the ACA, Title X, and state family planning programs.

Methods

Our sample included 237 safety net clinics in 11 states with a common electronic health record. We identified contraception-related visits among women ages 10-49 using diagnosis and procedure codes. Our primary outcome was an indicator of an uninsured visit. We also assessed payor type (public/private). We included encounter, clinic, county, and state-level covariates. We used interrupted time series and logistic regression, and calculated multivariable absolute predicted probabilities.

Results

We identified 162,666 contraceptive visits in 219 clinics. There was a significant decline in uninsured contraception-related visits in both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states, with a slightly greater decline in expansion states (DID −1.29 percentage points; CI −1.39—1.19). The gap in uninsured visits between expansion and non-expansion states widened after ACA implementation (from 2.17 to 4.1 percentage points). The Title X program continues to fill gaps in insurance in Medicaid expansion states.

Conclusion

Uninsured contraceptive visits at safety net clinics decreased following Medicaid expansion under the ACA in both expansion and non-expansion states. Overall levels of uninsured visits are lower in expansion states. Title X continues to play an important role in access to care and coverage. In addition to protecting insurance gains under the ACA, Title X and state programs should continue to be a focus of research and advocacy.

Keywords: safety net, contraception, Title X, insurance, ACA, Medicaid expansion

INTRODUCTION

Contraception is a key part of women’s preventive health care.(1) High quality and continuous access to contraception is a core strategy(2, 3) to reduce the proportion of births in the US that are unintended, a national public health goal.(4) Unintended pregnancy continues to be endemic in the US(5), and is increasingly concentrated among low-income families and people of color.(5, 6) Unintended pregnancy is a health disparity with multigenerational consequences and leads to worse health outcomes for women and their children. (7)

The United States (US) safety net health system includes community health centers (CHCs), Federally Qualified Health Centers, and non-profit entities that use federal and state funds to provide services regardless of patients’ ability to pay.(8) It is the largest system of primary care for our nation’s low-income, uninsured, and publicly insured patients,(9, 10) and an important source of reproductive health care. In 2015, safety net providers delivered contraceptive care to 6.2 million low-income women,(11) relying on three key funding mechanisms for family planning in the US: Medicaid, Title X (12) and state family planning programs (Medicaid 1115 waiver or State Plan Amendments (13)); each has distinct eligibility and scope.

Medicaid expansion under The Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased the number of individuals with insurance coverage (14), including reproductive aged women.(15) Medicaid expansion explicitly excludes undocumented and new (less than 5 years) immigrants.(16) Title X is a federal program that provides block grants to pay for sexual and reproductive health services for low-income women and men who do not have other coverage, such as undocumented or new immigrants, young people, or those who fall through coverage gaps in Medicaid. Title X grantees follow quality of care guidance from the CDC and provide comprehensive care in terms of counseling and method choice; safety net clinics that are not Title X grantees may not provide a full range of contraceptive methods.(17) State family planning programs, either through a Medicaid waiver (1115 waiver) or a state plan amendment (SPA), pay for contraceptive services; states that implement such programs have different scope of coverage and eligibility criteria, and not all clinics in a state will be members of the program.(18)

There are ongoing policy debates about how best to use public funds to provide family planning services for low-income women; it is imperative to understand how Medicaid expansion, Title X, and state family planning programs contribute to contraceptive services across the safety net system to inform policy discussions.(17, 19, 20) Evidence about payors across the safety net is limited due to fragmented service delivery and payment. Available data are reported at the facility level (21, 22), focus exclusively on one payor (23, 24) or program (25), or include only specialized reproductive health clinics.(26-28)

We use patient-level data from across the safety net system to describe how Medicaid expansion under the ACA impacted rates of uninsured contraceptive visits in safety net clinics and explore the independent associations of Medicaid expansion, Title X, and state family planning programs to payment for contraceptive services in safety net clinics.

METHODS

We conducted an historical cohort study(29) of face-to-face clinic visits by women of reproductive age in safety net clinics that participate in a shared Electronic Health Record (EHR) system with one master patient index.(30) The shared EHR is administered by OCHIN (not an acronym), a non-profit entity that hosts and manages an EHR platform for 451 safety net clinics, with over 3,059 primary care providers serving more than 889,965 adult patients across 17 states. The OCHIN network encourages practice-based research that advances understanding of the health of underserved populations, improves quality of care, and informs policy. OCHIN data have been validated in several studies.(31, 32) In this study, we included 237 clinics that participated in the EHR for the entire study period.

The primary outcome for this study was insurance coverage for contraceptive visits, which we examined as a binary variable (insured, uninsured) as well as by payor type (public, private, uninsured). Contraceptive visits were classified as uninsured visits if the source of payment was identified as uninsured versus any type of insurance used (public or private). The OCHIN EHR data allow robust tracking of both insured and uninsured visits.

The primary independent variable in this study was Medicaid expansion at the state level under the ACA. As of April 2016, 32 states and the District of Columbia implemented expansions and 18 states did not, creating a natural experiment.(33, 34) We included safety net clinics located in seven states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 (California, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Wisconsin, and Washington) and in four non-expansion states (Alaska, Indiana, Montana, and North Carolina). We included visits from 12 months pre-expansion (January 1, 2013-December 31, 2013) through 12 months post-expansion (January 1, 2014-December 31, 2014). We classified Wisconsin as an expansion state, following previous literature(32, 35, 36), given that they expanded Medicaid to 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), although outside of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). We chose to focus on 2013 and 2014 only to focus on the immediate post-ACA Medicaid expansion period and also to avoid dropping clinics from our sample as they move on and off the EHR.

We also explore the independent associations of Medicaid expansion, Title X, and state family planning programs to payment for contraceptive services in safety net clinics. We classified each clinic as receiving Title X funding or not during the study period. We classified each state has having a state family planning program or not (including both 1115 waiver or State Plan Amendment (SPA) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

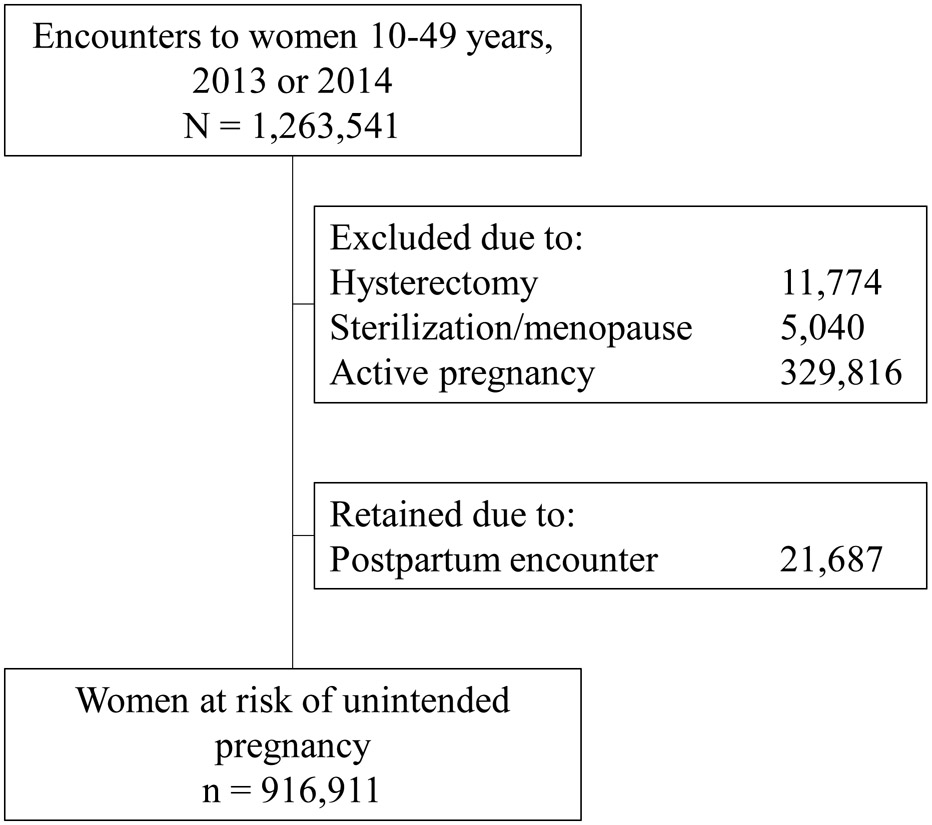

We identified all face-to-face visits among women aged 10 to 49 years (N = 1,263,541 visits). We excluded visits by women with evidence of hysterectomy or sterilization/menopause. We excluded visits by pregnant women (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for codes) as they are not at risk of pregnancy, but retained visits which were identified as postpartum since the first postpartum visit is an opportune time to receive contraception (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3).(37, 38) Our final analytic sample consisted of 916,911 visits by 236,783 unique women at risk of pregnancy in 237 clinics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study sample.

We identified contraceptive visits using International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes, Physician’s Current Procedural Terminology Coding System, 4th Edition (CPT) codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, and orders for drugs and devices that were related to contraception (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4). Our measure of a contraceptive visit was designed to be broad; we captured counseling as well as initiation and surveillance of a method. Our interest was in payment for contraception-related services broadly, not specific types of services or contraceptive methods.

We included encounter, clinic, woman’s census tract, woman’s county, and state-level variables from the EHR or merged in from additional sources.(39) Visit-level EHR data included: age, race/ethnicity, FPL category, whether an interpreter was needed, if the encounter was with a women’s health specialist (OB/Gyn or Women’s Health Nurse Practitioner versus other provider type), and patient-reported migrant worker status. In addition to clinic Title X status, we included rural (vs. not) location of the clinic, based on the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes(40) linked to patients’ zip code of last-known residence. We considered characteristics of the woman’s county of residence. These variables included the 2010–2014 census tract-specific proportion of the population at less than 200% federal poverty level(41) and presence of Planned Parenthood clinics within the woman’s county of residence as a proxy for supply of alternative sources of contraceptive services. In addition to Medicaid expansion and state family planning program, we included state-level maximum FPL limit for adult Medicaid eligibility in 2013 (for parents in a family of 3).(42)

Our unit of analysis is the visit. First, among all contraceptive visits we identified, we compared encounter/woman, clinic, county, and state-level variables by time (pre- and post-ACA) and state Medicaid expansion status. We described payor (uninsured, public, private). All descriptive analyses relied on frequencies and bivariate tests. We calculated crude difference-in-difference of change pre- and post-ACA by expansion status for our outcome (uninsured contraceptive visit) and graphically examined trends in the proportion of uninsured visits by month.

We next conducted an interrupted time series analysis to compare the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits per month by expansion status. We set January 1, 2014 as the change point. All regression models also included a first-order autoregressive term to control for serial autocorrelation(43) by time (month of encounter). This analysis does not explicitly account for woman, clinic, county, or state-level factors that could also influence the outcome, but the time series approach does account for underlying secular trends in both groups and is thus a valid approach to examining differences between Medicaid expansion groups.

We then developed two multivariable logistic regression models to test the association between Title X, state family planning programs and uninsured visits, stratified by Medicaid expansion status. These models included woman, clinic, county, and state-level covariates as described above. Women classified as non-Hispanic other were combined with those of unknown race/ethnicity in models due to the small sizes of both groups. We clustered on the individual as one woman may have more than one visit in our dataset.

We undertook several sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of our results. We ran analyses with and without a “wash-out” period of July-December 2013(14), since some women were able to access insurance under the ACA prior to the January 1 2014 start date. We also ran analyses using different expansion dates for Wisconsin encounters, since they expanded Medicaid April 1, 2014. Results were unchanged (data not shown). Finally, we ran models with and without Title X and state family planning program variables; estimates of the association of the ACA and odds of an uninsured visit were robust to these changes; data not shown. The final models were selected based on utilization of healthcare theory (44) and previous literature about access to and use of health services (45), stability to sensitivity analyses, and examination of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).(46)

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX); figures were prepared in R (version 3.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna Austria). This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 162,666 (17.7% of the N=916,911 total sample of visits by women at risk of pregnancy) contraceptive visits in 219 clinics, the large majority of which (95.6%) were from expansion states. Of these contraceptive visits, about one-quarter were by women ages 15 to 19 (26% pre-ACA, 23.7% post-ACA), 62% by women with incomes less than 100% of FPL, and about one-third by Hispanic women, half by non-Hispanic White women, and 12% by non-Hispanic Black women with differences by Medicaid expansion status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Woman, clinic, woman’s residence and state-level sample characteristics of visits with contraception provision.

| Overall | Expansion | Non-expansion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of encounters | 162,666 | 155,482 | 7,184 | ||||||

| Pre-ACA | Post- ACA |

p | Pre-ACA | Post-ACA | p | Pre-ACA | Post-ACA | p | |

| 80,806 (49.70) | 81,860 (50.32) | 77,233 (49.67) | 78,249 (50.33) | 3,573 (49.74) | 3,611 (50.26) | ||||

| Woman-level characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (at encounter) | |||||||||

| 10 to 14 | 1,886 (2.33) | 1,677 (2.05) | 1,772 (2.29) | 1,562 (2.00) | 114 (3.19) | 115 (3.18) | |||

| 15 to 19 | 21,007 (26) | 19,416 (23.72) | 20,117 (26.05) | 18,449 (23.58) | 890 (24.91) | 967 (26.78) | |||

| 20 to 24 | 17,760 (21.98) | 17,404 (21.26) | 16,784 (21.73) | 16,463 (21.04) | 976 (27.32) | 941 (26.06) | |||

| 25 to 29 | 15,830 (19.59) | 16,211 (19.8) | 15,116 (19.57) | 15,484 (19.79) | 714 (19.98) | 727 (20.13) | |||

| 30 to 34 | 11,195 (13.85) | 12,366 (15.11) | 10,775 (13.95) | 11,944 (15.26) | 420 (11.75) | 422 (11.69) | |||

| 35 to 39 | 6,926 (8.57) | 8,003 (9.78) | 6,705 (8.68) | 7,771 (9.93) | 221 (6.19) | 232 (6.42) | |||

| 40 to 44 | 4,084 (5.05) | 4,542 (5.55) | 3,939 (5.1) | 4,407 (5.63) | 145 (4.06) | 135 (3.74) | |||

| 45 to 49 | 2,118 (2.62) | 2,241 (2.74) | <0.001 | 2,025 (2.62) | 2,169 (2.77) | <0.001 | 93 (2.6) | 72 (1.99) | 0.423 |

| Federal Poverty Level (FPL) category | |||||||||

| <100% | 50,060 (61.95) | 50,489 (61.68) | 47,993 (62.14) | 48,268 (61.69) | 2,067 (57.85) | 2,221 (61.51) | |||

| 101-150% | 11,765 (14.56) | 11,867 (14.5) | 11,306 (14.64) | 11,436 (14.61) | 459 (12.85) | 431 (11.94) | |||

| 151-200% | 4,747 (5.87) | 4,795 (5.86) | 4,480 (5.8) | 4,530 (5.79) | 267 (7.47) | 265 (7.34) | |||

| Over 200% | 6,741 (8.34) | 6,950 (8.49) | 6,351 (8.22) | 6,573 (8.4) | 390 (10.92) | 377 (10.44) | |||

| Missing/unknown | 7,493 (9.27) | 7,759 (9.48) | 0.476 | 7,103 (9.2) | 7,442 (9.51) | 0.142 | 390 (10.92) | 317 (8.78) | 0.007 |

| Need for an interpreter | 12,363 (15.3) | 13,360 (16.32) | <0.001 | 12,292 (15.92) | 13,262 (16.95) | <0.001 | 71 (1.99) | 98 (2.71) | 0.042 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 25,139 (31.11) | 27,434 (33.51) | 24,933 (32.28) | 27,211 (34.77) | 206 (5.77) | 223 (6.18) | |||

| non-Hispanic White | 41,144 (50.92) | 40,161 (49.06) | 39,373 (50.98) | 38,449 (49.14) | 1,771 (49.57) | 1,712 (47.41) | |||

| non-Hispanic Black | 10,319 (12.77) | 9,845 (12.03) | 8,855 (11.47) | 8,321 (10.63) | 1,464 (40.97) | 1,524 (42.2) | |||

| non-Hispanic Other | 3,042 (3.76) | 3,139 (3.83) | 2,934 (3.8) | 3,016 (3.85) | 108 (3.02) | 123 (3.41) | |||

| Missing/unknown | 1,162 (1.44) | 1,281 (1.56) | <0.001 | 1,138 (1.47) | 1,252 (1.6) | <0.001 | 24 (0.67) | 29 (0.8) | 0.390 |

| Visit to a women's health care provider | 7,037 (8.71) | 6,623 (8.09) | <0.001 | 7,037 (9.11) | 6,613 (8.45) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 10 (0.28) | 0.002 |

| Clinic-level characteristics | |||||||||

| Visit to a Title X clinic | 24,863 (30.77) | 22,178 (27.09) | <0.001 | 24,541 (31.78) | 21,835 (27.9) | <0.001 | 322 (9.01) | 343 (9.5) | 0.477 |

| Rural clinic location | 2,893 (3.58) | 2,832 (3.46) | 0.187 | 2,753 (3.56) | 2,722 (3.48) | 0.358 | 140 (3.92) | 110 (3.05) | 0.044 |

| Woman’s county level characteristics | |||||||||

| % < 200% Federal Poverty Level in census tract | |||||||||

| < 30 | 11,767 (14.56) | 12,291 (15.01) | 11,394 (14.75) | 11,919 (15.23) | 373 (10.44) | 372 (10.3) | |||

| ≥30 and < 40 | 40,127 (49.66) | 37,383 (45.67) | 38,665 (50.06) | 35,992 (46) | 1,462 (40.92) | 1,391 (38.52) | |||

| ≥ 40 | 28,742 (35.57) | 31,868 (38.93) | 27,007 (34.97) | 30,041 (38.39) | 1,735 (48.56) | 1,827 (50.6) | |||

| Missing/unknown | 170 (0.21) | 318 (0.39) | <0.001 | 167 (0.22) | 297 (0.38) | <0.001 | 3 (0.08) | 21 (0.58) | 0.001 |

| Number of Planned Parenthood clinics in county | |||||||||

| 0 | 23,369 (28.92) | 24,654 (30.12) | 21,111 (27.33) | 22,367 (28.58) | 2,258 (63.2) | 2,287 (63.33) | |||

| ≥ 1 | 57,437 (71.08) | 57,206 (69.88) | <0.001 | 56,122 (72.67) | 55,882 (71.42) | <0.001 | 1,315 (36.8) | 1,324 (36.67) | 0.903 |

| State-level characteristics | |||||||||

| State family planning program | 65,981 (81.65) | 67,487 (82.44) | <0.001 | 64,723 (83.8) | 66,266 (84.69) | <0.001 | 1,258 (35.21) | 1,221 (33.81) | 0.214 |

| Maximum FPL for 2013 adult Medicaid eligibility | |||||||||

| < 50% | 46,309 (57.31) | 2,089 (2.55) | 44,295 (57.35) | 0 (0) | 2,014 (56.37) | 2,089 (57.85) | |||

| 50 - 138% | 32,102 (39.73) | 2,928 (3.58) | 30,543 (39.55) | 1,406 (1.8) | 1,559 (43.63) | 1,522 (42.15) | |||

| ≥ 138% | 2,395 (2.96) | 76,843 (93.87) | <0.001 | 2,395 (3.1) | 76,843 (98.2) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.204 |

In Medicaid expansion states, the proportion of contraceptive visits that took place in Title X clinics decreased after ACA implementation (31.78% in 2013 versus 27.9% in 2014, p <0.001), while only about 10% of contraceptive visits in non-expansion states were at Title X clinics (9.01% in 2013 vs. 9.5% in 2014, p = 0.477) (Table 1).

The overall proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits decreased after ACA implementation in both Medicaid expansion (Table 2; 24.77% to 16.66%) and non-expansion (27.37% to 20.55%) states. The crude difference-in-difference, or the difference in the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits in 2014 versus 2013 in states that did not expand Medicaid under the ACA minus the difference in the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits in 2014 versus 2013 in states that did expand Medicaid under the ACA, was −1.29 percentage points (95% confidence interval (CI) (−1.39, −1.19)), indicating a slightly greater decline in uninsured visits in expansion states. This decline in uninsured contraceptive visits was mirrored by an increase in publicly insured visits, with larger increases in expansion (62.80% to 70.20%) versus non-expansion (41.23% to 46.19%) states (2.44 crude difference-in-difference (95% CI (2.41, 2.46)). Private insurance utilization for contraceptive visits accounts for over one-third of visits in non-expansion states, and 12–13% in expansion states. Private insurance increased slightly in both expansion and non-expansion states but increased more in non-expansion states (−1.15 percentage point difference-in-difference (95% CI −1.16, −1.13)).

Table 2.

Source of payment for contraceptive visits (2013-2014)

| Overall N=162,666 | Expansion N=155,482 | Non-expansion N=7,184 |

Crude difference- in-difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ACA | Post- ACA* |

Pre-ACA | Post- ACA* |

Pre-ACA | Post- ACA* |

%age point (95% confidence interval) |

|

| n = | 80,806 | 81,860 | 77,233 | 78,249 | 3,573 | 3,611 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Uninsured/ Self-pay | 24.88 | 16.83 | 24.77 | 16.66 | 27.37 | 20.55 | −1.29 (−1.39, −1.19) |

| Public | 61.85 | 69.14 | 62.80 | 70.20 | 41.23 | 46.19 | 2.44 (2.41, 2.46) |

| Private | 13.27 | 14.03 | 12.43 | 13.14 | 31.40 | 33.26 | −1.15 (−1.16, −1.13) |

P <0.001 for distribution of insurance by time period

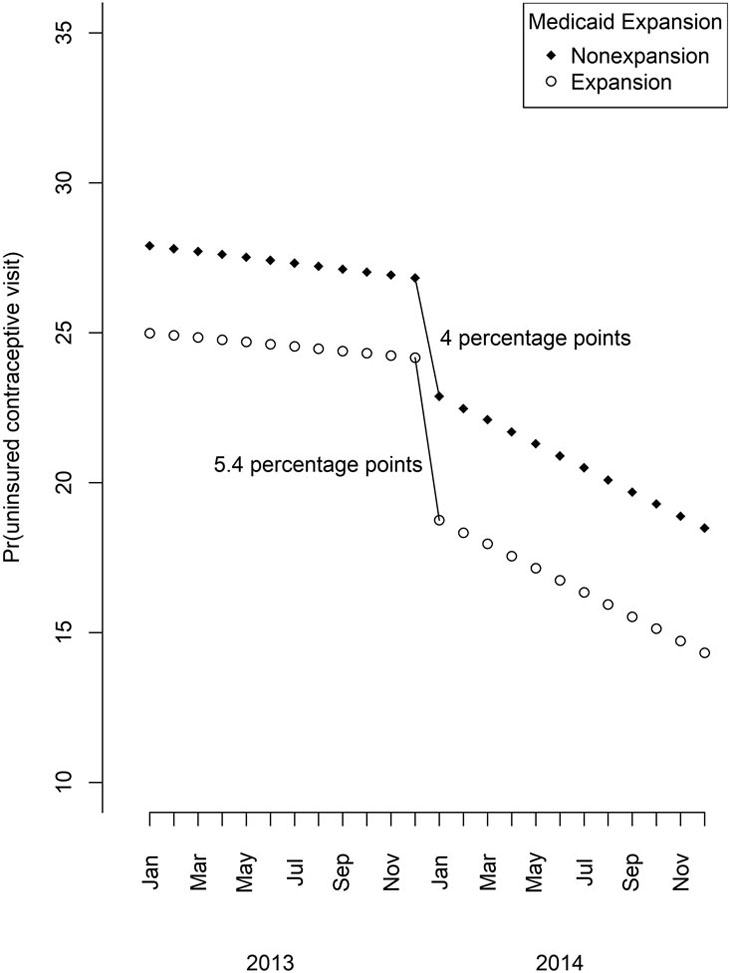

In the time series analysis, the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits each month is consistently lower in Medicaid expansion states than in non-expansion states both before and after ACA implementation. Uninsured visits dropped over time and sharply after ACA implementation in both expansion and non-expansion states. The decline in the probability of uninsured contraceptive visits was statistically significant (p<0.001) for both expansion and non-expansion states (Figure 2). The gap in uninsured visits between expansion and non-expansion states widened after ACA implementation (2.7 percentage point difference in December 2013 versus 4.1 percentage point difference in January 2014).

Figure 2.

Interrupted time series for the probability of uninsured contraceptive visits in expansion and non-expansion states.

The multivariable models support the crude difference-in-difference and the time series analyses, with the ACA associated with lower odds of an uninsured contraceptive visit for both expansion (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.57 – 0.61) and non-expansion (aOR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.56 – 0.73) states (Table 3). Clinic Title X status was associated with larger odds of an uninsured visit in expansion states (aOR = 1.14; 95% CI = 1.07 – 1.20) while we observed a non-significant association in non-expansion states (aOR = 0.77; 95% CI = 0.50 – 1.19), perhaps explained by the lack of variance (only 9% of visits were to Title X clinics). The presence of a state family planning program was associated with much lower odds of an uninsured visit in expansion states (aOR = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.06 – 0.07).

Table 3.

Association between woman, clinic, and state-level characteristics and an uninsured contraceptive visit. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

| Medicaid expansion states |

Medicaid non-expansion states | |

|---|---|---|

| Post-ACA encounter | 0.59 (0.57 - 0.61) | 0.64 (0.56 - 0.73) |

| Title X status | 1.14 (1.07 - 1.20) | 0.77 (0.50 - 1.19) |

| State family Planning Program |

0.06 (0.06 - 0.07) | 4.86 (2.78 - 8.50) |

| Woman-level variables | ||

| Age at encounter | ||

| 10 to 14 | 0.65 (0.52 - 0.80) | 0.16 (0.08 - 0.30) |

| 15 to 19 | 0.85 (0.79 - 0.91) | 0.36 (0.28 - 0.47) |

| 20 to 24 | 0.88 (0.83 - 0.94) | 0.89 (0.72 - 1.11) |

| 25 to 29 | Referent | Referent |

| 30 to 34 | 1.08 (1.01 - 1.15) | 1.08 (0.81 - 1.44) |

| 35 to 39 | 1.13 (1.04 - 1.22) | 0.97 (0.69 - 1.37) |

| 40 to 44 | 1.21 (1.10 - 1.33) | 1.46 (0.91 - 2.34) |

| 45 to 49 | 1.12 (0.98 - 1.28) | 0.73 (0.43 - 1.25) |

| FPL category | ||

| 100% and below | 0.94 (0.86 - 1.02) | 1.80 (1.34 - 2.41) |

| 101-150% | 0.98 (0.89 - 1.08) | 2.12 (1.52 - 2.98) |

| 151-200% | 0.96 (0.85 - 1.08) | 1.94 (1.34 - 2.82) |

| Over 200% | Referent | Referent |

| missing/unknown | 2.34 (2.10 - 2.62) | 0.52 (0.33 - 0.81) |

| Need for interpreter | 3.02 (2.83 - 3.22) | 4.61 (2.50 - 8.50) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3.79 (3.55 - 4.04) | 1.60 (1.08 - 2.37) |

| Non-Hispanic white | Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.25 (1.14 - 1.37) | 0.39 (0.29 - 0.53) |

| Non-Hispanic other/Unknown | 1.76 (1.59 - 1.96) | 1.17 (0.73 - 1.86) |

| Visit to women’s health specialist | 1.25 (1.17 - 1.34) | Predicts outcome perfectly; removed from model |

| Clinic-level variables | ||

| Rural clinic | 1.15 (1.01 - 1.30) | 0.92 (0.56 - 1.51) |

| Woman’s residence-level variables | ||

| % population < 200% FPL in census tract | ||

| < 30 | Referent | Referent |

| ≥30 and < 40 | 0.73 (0.68 - 0.78) | 0.35 (0.23 - 0.55) |

| ≥ 40 | 0.67 (0.62 - 0.71) | 0.56 (0.37 - 0.86) |

| Planned Parenthood clinics in county | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| ≥ 1 | 1.28 (1.21 - 1.36) | 1.69 (1.24 - 2.29) |

| State-level variables | ||

| Max FPL for 2013 adult Medicaid eligibility | ||

| < 50% | Referent | Referent |

| 50 - 138% | 0.10 (0.09 - 0.10) | 0.23 (0.13 - 0.42) |

| ≥ 138% | 0.88 (0.76 – 1.02) | No observations |

DISCUSSION

Medicaid expansion after the ACA resulted in a decline in uninsured contraceptive visits across the safety net system. However, the gap in uninsured visits between expansion and non-expansion states widened after ACA implementation; states that expanded Medicaid coverage had a slightly larger decline in uninsured visits than states that did not expand coverage. Following implementation of Medicaid expansion, in our sample of contraceptive visits across safety net clinics in the US, thousands more women used insurance to pay for a visit.

Our findings on declines in uninsured contraceptive visits are consistent with previous literature examining the impact of the ACA on the rate of uninsured safety net clinic clients overall; the proportion of visits to safety net primary care clinics that are covered by insurance has grown.(32) Previous literature focused on state-level Medicaid expansion has found that it was associated with increased self-reported access to family planning services in Michigan(47), but not in California(48), possibly due to a pre-existing robust state family planning program. Potential “spill-over” effects of Medicaid expansion in states that did not expand Medicaid could operate via new state family planning programs, such as the one Indiana, a non-expansion state, implemented.(49) ACA spillover is also suggested in our data by increases in contraceptive coverage via private insurance gained through insurance exchanges under the ACA.(50-53)

Our study addresses an important gap in the literature by examining the role of different payors in the fragmented family planning safety net system. Understanding how distinct payors contribute to key health outcomes is essential data to guide policy. Each funding stream has comparative advantages and disadvantages.(54) The fragmented coverage of family planning in the US has made it challenging to examine contraceptive utilization in safety net clinics as a whole: our findings support the need for broad access to family planning services through Medicaid expansion, with specialized reproductive health services available from complementary systems (Title X and state family planning programs). In the current political environment, each program faces an uncertain future.(20, 55) For example, although it is known that Title X clients have experienced gains in insurance (56, 57) our findings report on gains in insurance across the safety net system for contraception-related services and show that even in states that expanded Medicaid, Title X continues to play a key role providing access to women who remain uninsured due to Medicaid eligibility limits, immigration status, or for other reasons. Further, Title X may be even more crucial in non-expansion states where uninsurance remains higher. An understanding of the role Title X plays in promoting reproductive health, and mitigating health disparities is essential. Evidence to date shows that Title X funds have an impact beyond direct service provision in enhancing overall clinic services for all clients (whether or not their visit is paid for by Title X) such as expanded clinic hours, community outreach, interpreter services and provider training. (58, 59)

Current proposed changes to the Title X program, include a reduced focus on offering a broad range of FDA-approved contraceptive methods, including the most effective methods, the exclusion of reproductive health care specialty clinics from the Title X program, and less protection for confidentiality for adolescent clients.(60) These proposed changes are anticipated to result in decreasing access to a broad range of contraceptive methods.(17, 61)

Studies of the impacts of state family planning programs consistently find that they increase access to contraception and contribute to the reduction of disparities in use of contraception and unintended pregnancy by age, race/ethnicity, or insurance status.(5, 24, 47, 58, 62-64) Recent evidence also points to negative impacts on access to contraception when family planning specialty providers are excluded from state family planning programs.(65, 66) Our results show that state family planning programs are strongly associated with an insured visit in Medicaid expansion states, suggesting a crucial continued role for these programs.

Our study should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, despite the advantage of an encounter-level dataset with a diversity of safety net clinics, our sample does not include all safety net clinics in participating states nor all states. Second, our ability to isolate the effects of diverse but sometimes overlapping policies (ACA, Title X, state programs) is imperfect. For example, our sample of Title X clinics in non-expansion states is small, and only one of our non-expansion states had a state family planning program. Results from the non-expansion states model should be interpreted with some caution. Third, we only included clinics that contributed data for the entire study period. This was done in an attempt to reduce bias introduced by influential individual clinics leaving or entering the EHR. However, states with small samples of clinics still likely exert disproportionate influence. These results may not be generalizable to the entire universe of safety net clinics. Finally, we include two years of data, 2013 and 2014. Our goal was to examine 2014 as an inflection point for changes in payment for contraceptive services across the safety net, and previous work has shown that the safety net population rapidly enrolled.(67, 68) However, our ability to extrapolate to the current day is obviously limited. Our findings can serve as a baseline of the impacts of expanding Medicaid; future studies will need to include more years of data.

Insurance utilization for contraceptive encounters increased in safety net clinics in both expansion and non-expansion states. Medicaid expansion under the ACA reduced the proportion of uninsured contraceptive visits in safety net clinics. State family planning programs and Title X continue to play vital roles in providing access to and funding contraceptive services. Given the population health benefits of continuous, comprehensive access to reproductive health care, health policy research and advocacy should center on protecting insurance gains under the ACA, maintaining the integrity of the Title X program, and state-level efforts to enhance family planning programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Darney was supported by the Society of Family Planning (SFPRF10-II2-2 and SFPRF12-2), R01HS025155 (Cottrell, PI), and grant number K12HS022981 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Rodriguez was a Women’s Reproductive Health Research fellow; grant 1K12HD085809. Dr. Cottrell and DeVoe are supported by grant number CDRN-1306–04716 from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Portions of this work was presented at the 2017 Population Association of America (PAA) manual meeting, Chicago, IL

Contributor Information

Blair G. DARNEY, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon Health and Science University. 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Mail Code L-466, Portland Oregon 97239. National Institute of Public Health, Population Research Center (INSP/CISP). Av Universidad No 655, Cuernavaca, MORELOS 62000, Mexico.

Frances M. BIEL, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon Health and Science University. 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Mail Code L-466, Portland Oregon 97239.

Maria I. RODRIGUEZ, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon Health and Science University. 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Mail Code L-466, Portland Oregon 97239.

R. Lorie JACOB, OCHIN, Inc. 1881 SW Naito Parkway, Portland, OR 97201.

Erika COTTRELL, OCHIN, Inc. 1881 SW Naito Parkway, Portland, OR 97201.

Jennifer DEVOE, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Family Medicine, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Mail Code FM Portland, OR 97239..

REFERENCES

- 1.Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, et al. Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:214–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control 2014;63:1–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavin L, Frederiksen B, Robbins C, et al. New clinical performance measures for contraceptive care: their importance to healthcare quality. Contraception 2017;96:149–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healthy People 2020 [database online]. Washington D.C. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;374:843–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtin SC, Ventura SJ, Martinez GM. Recent declines in nonmarital childbearing in the United States. NCHS Data Brief 2014:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann 2008;39:18–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost J, LF F, Blades N, et al. Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services at U.S. Clinics, 2015. 2017. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-funded-contraceptive-services-us-clinics-2015. Accessed August 8, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin P, Sharac J, Barber Z, et al. Community Health Centers: A 2013 Profile and Prospects as ACA Implementation Proceeds Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. Menlo Park, CA: 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin P, Sharac J, Rosenbaum S. Community Health Centers And Medicaid At 50: An Enduring Relationship Essential For Health System Transformation. Health Affairs 2015;34:1096–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasstedt K Federally Qualified Health Centers: Vital Sources of Care, No Substitute for the Family Planning Safety Net. Guttmacher Policy Review 2017;20 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of Family Planning. Program Guidelines for Project Grants for Family Planning Services. In: Services USDoHaH, ed.2001 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guttmacher Institute. Medicaid Family Planning Eligibility Expansions. 2018. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/medicaid-family-planning-eligibility-expansions. Accessed 8/9/2018,

- 14.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, et al. Changes in Self-reported Insurance Coverage, Access to Care, and Health Under the Affordable Care Act. Jama 2015;314:366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttmacher Institute. Uninsured Rate Among Women of Reproductive Age Has Fallen More Than One-Third Under the Affordable Care Act. 2016. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2016/11/uninsured-rate-among-women-reproductive-age-has-fallen-more-one-third-under. Accessed 8/9/2018,

- 16.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Coverage of Immigrants. 2019. Available at: https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/. Accessed 3/7/19,

- 17.Sobel L, Rosensweig C, Salganicoff A. Proposed Changes to Title X: Implications for Women and Family Planning Providers. 2018. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Proposed-Changes-to-Title-X-Implications-for-Women-and-Family-Planning-Providers. Accessed 8/29/2018, [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttmacher Institute. Medicaid family planning eligibility expansions State Laws and Policies. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasstedt K A Domestic Gag Rule And More: The Trump Administration’s Proposed Changes To Title X. In: Affairs H, ed. Health Affairs Blog; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guttmacher Institute. Gains in Insurance Coverage for Reproductive-Age Women at a Crossroads. 2018. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2018/12/gains-insurance-coverage-reproductive-age-women-crossroads. Accessed 12/19/18, [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter MW, Gavin L, Zapata LB, et al. Four aspects of the scope and quality of family planning services in US publicly funded health centers: Results from a survey of health center administrators. Contraception 2016;94:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park H-Y, Rodriguez MI, Hulett D, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception method use among Title X providers and non Title X providers in California. Contraception 2012;86:557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Rostovtseva D, Menz M, et al. The 2007 Family PACT medical record review: Assessing the quality of services. Sacremto, CA: Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez MI, Darney BG, Elman E, et al. Examining quality of contraceptive services for adolescents in Oregon’s family planning program. Contraception 2015;91:328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins SL, Starr KA, Hellerstedt WL, et al. Differences in Family Planning Services by Rural-urban Geography: Survey of Title X-Supported Clinics In Great Plains and Midwestern States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2016;48:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood S, Beeson T, Bruen B, et al. Scope of family planning services available in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Contraception 2014;89:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood S, Goldberg D, Beeson T, et al. Health centers and family planning: A nationwide survey. Washington, DC: George Washington University; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Frohwirth LF, et al. Variation in service delivery practices among clinics providing publicly funded family planning services in 2010. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klebanoff MA, Snowden JM. Historical (retrospective) cohort studies and other epidemiologic study designs in perinatal research. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeVoe JE, Gold R, Spofford M, et al. Developing a Network of Community Health Centers With a Common Electronic Health Record: Description of the Safety Net West Practice-based Research Network (SNW-PBRN). The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2011;24:597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey SR, Heintzman JD, Marino M, et al. Measuring Preventive Care Delivery: Comparing Rates Across Three Data Sources. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:752–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angier H, Hoopes M, Marino M, et al. Uninsured Primary Care Visit Disparities Under the Affordable Care Act. The Annals of Family Medicine 2017;15:434–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Supreme Court of the United States. National Federation of Independent Business v Sebelius. 2012

- 34.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Accessed May 26, 2015

- 35.DeLeire T, Dague L, Leininger L, et al. Wisconsin experience indicates that expanding public insurance to low-income childless adults has health care impacts. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2013;32:1037–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garfield R, Damico A, Orgera K. The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid. 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. Accessed 8/2/2018,

- 37.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 670: Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law A, Yu JS, Wang W, et al. Trends and regional variations in provision of contraception methods in a commercially insured population in the United States based on nationally proposed measures. Contraception 2017;96:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bazemore AW, Cottrell EK, Gold R, et al. “Community vital signs”: incorporating geocoded social determinants into electronic records to promote patient and population health. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA 2016;23:407–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.USDA. Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes. 2010. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx Accessed 3/20/19,

- 41.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2014

- 42.The Kaiser Comission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Eligibility for Adults as of January 1, 2014. 2013. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/8497-medicaid-eligibility-for-adults-as-of-january-1-2014.pdf. Accessed 8/29/2018, [Google Scholar]

- 43.StataCorp. Prais-Winsten and Cochrane-Orcutt Regression Reference Manual. 2013. Available at: https://www.stata.com/manuals13/tsprais.pdf. Accessed 10/15/2018, [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behaviorial model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly 2005;83: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raftery AE. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociological Methodology 1995;25:111–163 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moniz MH, Kirch MA, Solway E, et al. Association of Access to Family Planning Services With Medicaid Expansion Among Female Enrollees in Michigan. JAMA network open 2018;1:e181627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Early DR, Dove MS, Thiel de Bocanegra H, et al. Publicly Funded Family Planning: Lessons From California, Before And After The ACA’s Medicaid Expansion. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2018;37:1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ranji U, Blair Y, Salganicoff A. Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of the ACA. 2016. Available at: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/medicaid-and-family-planning-background-and-implications-of-the-aca/view/print/. Accessed 8/15, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heisel E, Kolenic GE, Moniz MM, et al. Intrauterine Device Insertion Before and After Mandated Health Care Coverage: The Importance of Baseline Costs. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:843–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pace LE, Dusetzina SB, Keating NL. Early Impact Of The Affordable Care Act On Oral Contraceptive Cost Sharing, Discontinuation, And Nonadherence. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2016;35:1616–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finer LB, Sonfield A, Jones RK. Changes in out-of-pocket payments for contraception by privately insured women during implementation of the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. Contraception 2014;89:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Law A, Wen L, Lin J, et al. Are women benefiting from the Affordable Care Act? A real-world evaluation of the impact of the Affordable Care Act on out-of-pocket costs for contraceptives. Contraception 2016;93:392–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Private and Public Coverage of Contraceptive Services and Supplies in the United States. 2015. Available at: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/private-and-public-coverage-of-contraceptive-services-and-supplies-in-the-united-states/. Accessed 2/15, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sobel L, Salganicoff A, Rosensweig C. The Future of Contraceptive Coverage. 2017. Available at: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/the-future-of-contraceptive-coverage/. Accessed 8/29/2018, [Google Scholar]

- 56.Decker EJ, Ahrens KA, Fowler CI, et al. Trends in Health Insurance Coverage of Title X Family Planning Program Clients, 2005–2015. Journal of Women’s Health 2018;27:684–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kavanaugh ML, Zolna MR, Burke KL. Use of Health Insurance Among Clients Seeking Contraceptive Services at Title X-Funded Facilities in 2016. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 2018;50:101–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Cross Riedel J, Menz M, et al. Onsite provision of specialized contraceptive services: does Title X funding enhance access? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:428–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Maguire F, Hulett D, et al. Enhancing service delivery through Title X funding: Findings from California. Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2012;44:262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health Office of the Secretary Compliance with Statuatory Program Integrity Requirements. In: Services DoHaH, ed. 42 CFR Part 59. Federal Register2018 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bronstein JM. Radical Changes for Reproductive Health Care — Proposed Regulations for Title X. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;379:706–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chabot MJ, Navarro S, Swann D, et al. Association of access to publicly funded family planning services with adolescent birthrates in California counties. Am J Public Health 2014;104 Suppl 1:e1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cawthon L, Rust K, Efaw BW. TAKE CHARGE Final Evaluation. Three-Year Renewal: July 2006 – June 2009. A Study of Recently Pregnant Medicaid Women. 2009. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/wa/Take-Charge/wa-take-charge-final-eval-092009.pdf. Accessed 12/14/18, [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunlop AL, Adams EK, Hawley J, et al. Georgia’s Medicaid Family Planning Waiver: Working Together with Title X to Enhance Access to and Use of Contraceptive and Preventive Health Services. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health 2016;26:602–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stevenson AJ, Flores-Vazquez IM, Allgeyer RL, et al. Effect of Removal of Planned Parenthood from the Texas Women’s Health Program. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;374:853–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White K, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, et al. The impact of reproductive health legislation on family planning clinic services in Texas. Am J Public Health 2015;105:851–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Angier H, Hoopes M, Gold R, et al. An Early Look at Rates of Uninsured Safety Net Clinic Visits After the Affordable Care Act. Annals of family medicine 2015;13:10–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoopes MJ, Angier H, Gold R, et al. Utilization of Community Health Centers in Medicaid Expansion and Nonexpansion States, 2013–2014. The Journal of ambulatory care management 2016;39:290–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.