Abstract

Carboplatin is characterized by low nephrotoxicity, including acute tubular necrosis (ATN), compared to a conventional platinum complex due to its low accumulative property in the renal tubules. Therefore, there are extremely few reports of carboplatin-induced kidney injury and only one case has been histologically examined. Herein, we describe the case of a 53-year-old man who presented with acute kidney injury (AKI) that occurred after carboplatin administration and was diagnosed with biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis (AIN). To our knowledge, this is the second case report of carboplatin-related AIN. The patient was diagnosed with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, and chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and irinotecan was initiated. However, 1 week later, he was admitted to our institution with fever, fatigue and an increase in C-reactive protein (CRP) level. The chemotherapy regimen was altered to carboplatin and etoposide, but high fever occurred on the first day, and CRP re-elevation and AKI became apparent 9 days later. Renal biopsy revealed prominent inflammatory cell infiltration into the interstitium, which lead to the pathological diagnosis of AIN. On immunostaining for surface markers, CD3- and CD68-positive cells were found to be predominant, and CD20-positive cells were relatively few. Although the serum creatinine level increased to 6.81 mg/dL, it decreased to 1.43 mg/dL 15 days after steroid therapy. This case demonstrated that carboplatin-related kidney injury includes not only ATN but also AIN. Appropriate pathological diagnosis including renal biopsy and indications for steroid treatment should be carefully considered.

Keywords: Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Acute interstitial nephritis, Acute kidney injury, Renal biopsy

Introduction

Cisplatin and carboplatin are platinum-based antineoplastic agents. Approximately 30% of patients receiving cisplatin have acute kidney injury (AKI), and it is not unusual for subsequent treatment to be limited [1]. On the other hand, carboplatin, which was developed as a derivative of cisplatin in the same platinum formulation, is considered to be less nephrotoxic. As a mechanism of cisplatin nephropathy, cisplatin is taken into the proximal renal tubule epithelial cells via organic cation transporter 2 (OCT 2) on the tubular basolateral membrane, and mitochondrial DNA damage and apoptosis are induced. Furthermore, the intracellular deposition of cisplatin causes acute tubular necrosis (ATN) through inflammation and oxidative stress [2, 3]. In contrast, carboplatin is not transported by OCT 2 and has been suggested to reduce nephrotoxicity due to low tubular accumulation [4].

To date, articles regarding carboplatin-induced kidney injury are extremely rare. Among them, there is only one case report whose pathological findings have been proven by renal biopsy. The authors experienced a case of carboplatin-related acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) and described it along with renal pathological features and clinical course.

Case report

A 53-year-old man was admitted to our facility after chemotherapy. His medical history is as follows. The patient was diagnosed with stage IV Hodgkin's lymphoma 12 years prior and achieved complete remission using a chemotherapy regimen composed of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD therapy). Epigastric pain appeared 4 months ago, and computerized tomography (CT) showed multiple lymphadenopathy. As a result of a left supraclavicular lymph node biopsy, he was diagnosed with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Anticancer treatment including cisplatin and irinotecan was initiated, but he was hospitalized 1 week after the first dose due to fever, general fatigue and C-reactive protein (CRP) level elevation. After admission, CRP level decreased. There was no evidence of infectious disease, and the efficacy of ceftriaxone (CTRX) and tazobactam/piperacillin (TAZ/PIPC) was unclear. The chemotherapy regimen was altered 2 weeks after admission, and carboplatin and etoposide were administered. A high fever appeared on the first day, and subsequently, the serum creatinine concentration increased to 1.93 mg/dL with CRP re-elevation 23 days after hospitalization (9 days after switching to chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide). An abdominal CT performed at this time revealed remarkable bilateral renal enlargement in comparison to the time of admission (Fig. 1). The patient was then introduced to our department, 27 days after hospitalization for AKI.

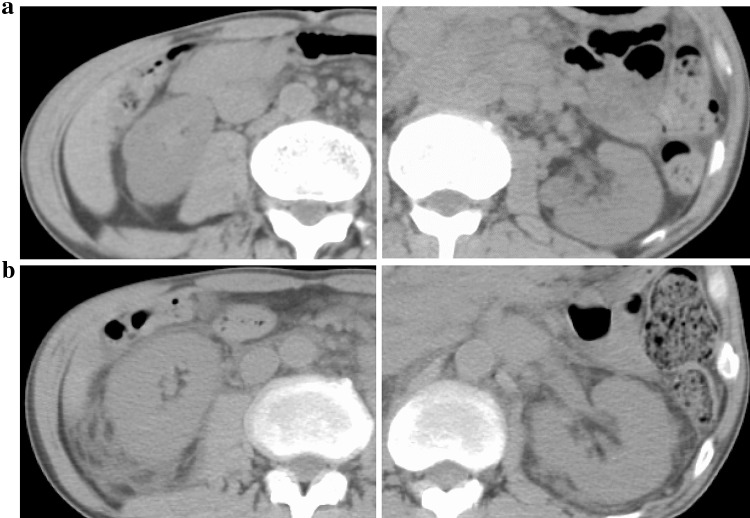

Fig. 1.

a The comparison of abdominal computerized tomography findings at admission and b at the onset of acute kidney injury (23 days after hospitalization). In a short period, bilateral kidneys significantly enlarged

At the initial visit to our department, he had a blood pressure of 104/73 mmHg, heart rate of 105 beats/min, and body temperature of 37.8 °C. The body height and weight were 169.5 cm and 57.0 kg, respectively. Physical examination revealed edematous erythema of the trunk and bilateral edema of the lower extremities. No abnormal signs were observed in the lungs, heart, and abdomen. Intraoral or ophthalmologic abnormalities were not identified.

There was no Sicca syndrome or submandibular gland swelling. Details of the clinical laboratory data are presented in Table 1. Urinalysis showed proteinuria with a protein excretion of 1.0 g/24 h and 1–4 red and white blood cells per high-power field. Urinary β2 microglobulin and N-acetylglucosaminidase levels were 99,324 μg/L and 22.1 U/L, respectively, suggesting severe tubular injury. No casts were found in the urine sediment. Urine cytodiagnosis did not detect eosinophils. Hematological tests indicated a white blood cell count of 2.2 × 103/μL, hemoglobin level of 8.6 g/dL, and platelet count of 108 × 103/μL. Laboratory investigation revealed a serum creatinine concentration of 5.26 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen level of 38.6 mg/dL, and estimated glomerular filtration rate of 10 mL/min/1.73 m2. The total serum protein level was 4.4 g/dL with a serum albumin level of 2.0 g/dL. The following laboratory data were obtained: total cholesterol (136 mg/dL), uric acid (8.9 mg/dL), serum sodium (135 mmol/L), serum potassium (3.9 mmol/L), serum chloride (100 mmol/L), serum calcium (7.3 mg/dL), creatine kinase (32 U/L), and CRP (10.34 mg/dL). Liver dysfunction and carbohydrate metabolism disorders were not observed. Immunological studies detected serum concentrations of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (633 mg/dL; normal range 870–1700 mg/dL), IgG4 (6.7 mg/dL; normal range 4.5–117 mg/dL), immunoglobulin A (IgA; 101 mg/dL; normal range 110–410 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin M (IgM; 291 mg/dL; normal range 35–220 mg/dL). The serum complement C3 level was 98.0 mg/dL (normal range 65–135 mg/dL) and C4 level was 18.9 mg/dL (normal range 13–35 mg/dL). The complement activity (CH50) was 34.7 U/mL (normal range 30–40 U/mL). The concentration of serum angiotensin I converting enzyme (ACE) was 8.7 U/L (normal range 8.3–21.4 U/L). The findings of the tests for hepatitis B and C, rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-SS-A/SS-B antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody were all negative. For infection-related examinations, blood and urine cultures, interferon-γ release assay, β-D glucan, and cytomegalovirus antigen were all negative. A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed 35 days after hospitalization to establish an accurate diagnosis for progressive kidney injury.

Table 1.

Clinical laboratory findings at the first visit to our department

| Hematological test | ALP | 291 | U/L | HBs-Ag | Negative | |||

| WBC | 2200 | /μL | LDH | 137 | U/L | HCV-Ab | Negative | |

| Neutro | 71 | % | Amy | 56 | U/L | IFN-γ release assay | Negative | |

| Lympho | 23 | % | CK | 32 | U/L | β-D-glucan | 5.0 > | pg/mL |

| Mono | 6 | % | CRP | 10.34 | mg/dL | CMV-Ag | Negative | |

| Eosino | 0 | % | Glu | 90 | mg/dL | Blood gas analysis (vein) | ||

| RBC | 290 | × 104/μL | HbAlc | 5.3 | % | pH | 7.392 | |

| Hb | 8.6 | g/dL | Immunological study | PC02 | 38.3 | mmHg | ||

| Plt | 10.8 | × 104/μL | IgG | 633 | mg/dL | P02 | 55.1 | mmHg |

| Laboratory investigation | IgA | 101 | mg/dL | HC03 | 22.8 | mmol/L | ||

| TP | 4.4 | g/dL | IgM | 291 | mg/dL | BE | −1.9 | mmol/L |

| Alb | 2.0 | g/dL | IgE | 146 | IU/mL | Urinalysis | ||

| UN | 38.6 | mg/dL | IgG4 | 6.7 | mg/dL | pH | 6.0 | |

| Cre | 5.26 | mg/dL | C3 | 98 | mg/dL | Protein | (2+) | |

| eGFR | 10 | mL/min/1.73 m2 | C4 | 18.9 | mg/dL | Occult blood | (±) | |

| UA | 8.9 | mg/dL | CH50 | 34.7 | U/mL | Glu | (−) | |

| TC | 136 | mg/dL | RF | 3.0 > | IU/mL | WBC | (−) | |

| Na | 135 | mmol/L | ANA | 40 > | Urinary sediment | |||

| K | 3.9 | mmol/L | Anti-SS-A Ab | Negative | RBC | 1–4 | /HPF | |

| Cl | 100 | mmol/L | Anti-SS-B Ab | Negative | WBC | 1–4 | /HPF | |

| Ca | 7.3 | mg/dL | MPO-ANCA | 1.0 > | U/mL | Cellular cast | Not detected | |

| P | 3.2 | mg/dL | PR3-ANCA | 1.0 > | U/mL | 24-h urinary protein | 1.0 | g/24 h |

| Mg | 1.5 | mg/dL | Anti-GBM Ab | 2.0 > | U/mL | B2MG | 99,324 | μg/L |

| T-bil | 0.26 | mg/dL | ACE | 8.7 | U/L | NAG | 22.1 | U/L |

| AST | 14 | U/L | Infection-related survey | BJP | Negative | |||

| ALT | 16 | U/L | Blood culture (vein) | Negative | Urinary culture | Negative |

WBC white blood cell, Neutro neutrophil, Lympho lymphocyte, Mono monocyte, Eosino eosinophil, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Plt platelet, TP total protein, Alb albumin, UN urea nitrogen, Cre creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, UA uric acid, TC total cholesterol, T-bil total bilirubin, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, Amy amylase, CK creatine kinase, CRP C-reactive protein, Glu glucose, Ig immunoglobulin, RF rheumatoid factor, ANA anti-nuclear antibody, Ab antibody, MPO myeloperoxidase, PR3 proteinase3, ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, GBM glomerular basement membrane, ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, HBs hepatitis B surface, Ag antigen, HCV hepatitis C virus, IFN interferon, CMV cytomegalovirus, BE base excess, HPF high-power field, β2MG β2-microglobulin, NAGN-acetylglucosaminidase, BJP Bence Jones protein

Renal biopsy

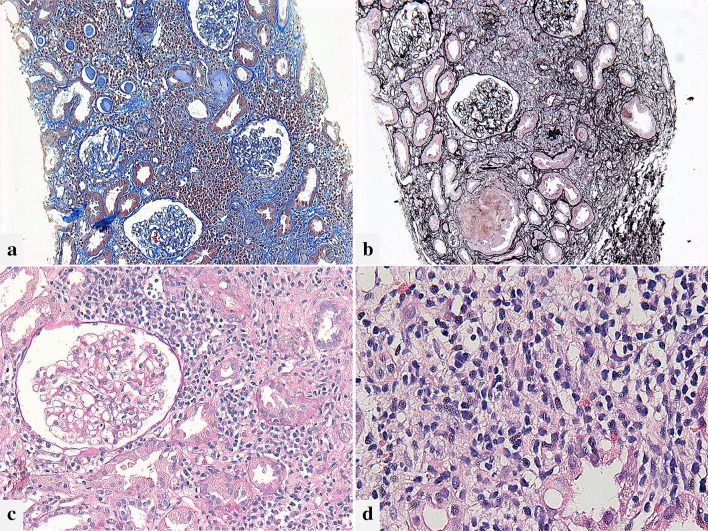

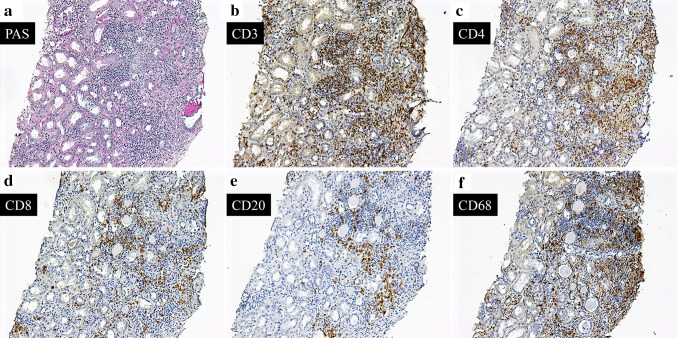

The kidney specimens were studied using light microscopy (LM), immunofluorescence (IF) staining, and electron microscopy (EM) using standard techniques. Renal pathological images are presented in Fig. 2. On LM, the sample contained 24 glomeruli, two of which showed global sclerosis. Remaining glomeruli were generally normal, and there was no mesangial proliferation, endocapillary hypercellularity, or extracapillary proliferation. A large number of inflammatory cells infiltrated into the interstitium. The major population of infiltrating cells was mononuclear cells. In addition, a small number of eosinophils and plasma cells were also observed. No granuloma formation was observed in the tissue. Leakage of Tamm–Horsfall protein (THP) into the interstitium accompanied with the rupture of the tubular basement membrane (TBM) was found. Although there was inflammatory cell invasion into the tubular epithelium, tubulitis was milder compared to the interstitial inflammation. Findings suggesting ATN, such as deciduation of tubular epithelial cells, were indistinguishable. IF staining only revealed nonspecific IgG deposition on the glomerular capillary walls, and IgA, IgM, and complement were negative. Immunoglobulin depositions were also negative in TBM. EM presented no electron-dense deposits in the tissue. The results of immunostaining for surface markers are shown in Fig. 3. In the interstitium, many CD3- and CD68-positive cells were found, and CD4-positive cells exceeded CD8-positive cells. CD20-positive cells were also present, but relatively few. These findings indicated interstitial inflammation mainly caused by infiltration of T lymphocytes and macrophages.

Fig. 2.

Light microscopic findings. a Diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells is observed in the presenting tubulointerstitial region. The area of interstitial fibrosis is minor. Masson’s trichrome staining, original magnification ×100. b The Tamm–Horsfall protein leaks into the interstitium with disruption of the tubular basement membrane. Periodic acid–methenamine silver staining, original magnification ×100. c There are no significant lesions in the glomerulus. The findings of tubulitis are less prominent compared to interstitial inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff staining, original magnification ×200. d The infiltrating cells in the interstitium are mainly composed of mononuclear cells and few eosinophils. Hematoxylin–eosin staining, original magnification ×400

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining for surface markers. Most of the interstitial inflammatory cells shown by periodic acid–Schiff staining (a) are CD3-positive cells (b). In comparison of staining for CD4- (c) and CD8- (d), CD4-positive cells are predominant. e Although CD20-positive cells are recognized in some areas, the number is generally small. f In the inflamed region, substantial CD68-positive macrophages are also observed. a–f Original magnification ×100. PAS periodic acid–Schiff

Clinical course

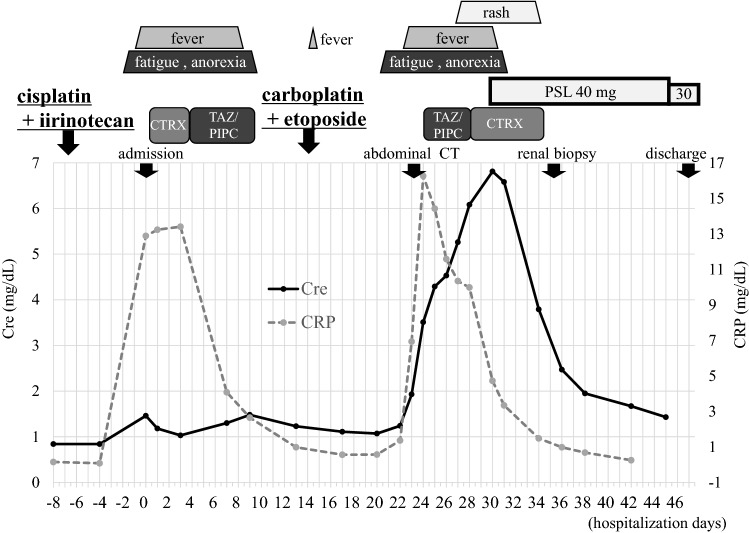

The clinical course of this case is shown in Fig. 4. Antibiotics (TAZ/PIPC and then CTRX) were re-administered for fever and elevated CRP level after chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide. However, no evidence of infection was obtained. Thereafter, erythema became prominent and was diagnosed with drug eruption. The serum creatinine level increased to 6.81 mg/dL 30 days after hospitalization, thus prednisolone (PSL; 40 mg/day) was initiated prior to renal biopsy. According to the renal pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with AIN, and steroid therapy was continued. The steroids were remarkably effective, and the serum creatinine level decreased to 1.43 mg/dL 15 days after treatment. He was discharged 47 days after hospitalization. Renal function was stable and PSL was gradually reduced to 12.5 mg/day. Unfortunately, the patient eventually died from the progression of the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Fig. 4.

Clinical course in this case. Cre creatinine, CRP C-reactive protein, CT computerized tomography, CTRX ceftriaxone, PSL prednisolone, TAZ/PIPC tazobactam/piperacillin

Discussion

We describe a case of biopsy-proven AIN that developed after carboplatin administration. To our knowledge, there has only been one other report on carboplatin-related AIN.

AIN is characterized pathologically by inflammatory cell infiltration and edematous change in the interstitium, often associated with rapidly progressive renal dysfunction. It reportedly accounts for 18.6% of cases in which renal biopsy was performed for AKI [5]. The main causes of AIN include drug-induced, infection-related, idiopathic forms containing tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome or anti-TBM disease; and systemic diseases such as vasculitis, sarcoidosis, Sjögren's syndrome, IgG4-related disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [6]. Among them, drug-induced AIN is the most frequent, and is currently on the rise [7]. Although any drug can cause AIN, antibacterial agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and proton pump inhibitors are particularly common causes [8]. With regard to drug-induced AIN, the period from drug administration to the appearance of renal manifestations has been reported to be approximately 10 days [9]. In the clinical features of AIN, almost all patients present with severe AKI, resulting in some cases that require dialysis. Leukocyturia is common in urinary findings of AIN, and it has been reported that microscopic hematuria is observed in more than half of patients [10]. The amount of urinary protein is low and rarely presents with nephrotic syndrome. Extrarenal clinical signs include fever, skin erythema, arthralgia, and eosinophilia, which are associated with allergic reactions to the drugs [11].

Since this case was diagnosed with AIN by renal biopsy, differential diagnosis was performed regarding the cause of AIN. First, infectious diseases including bacterial infections, tuberculosis, and fungal infections were ruled out from the results of culture tests, imaging findings, interferon-γ release assay, and β-D glucan assay. Clinical features suggesting vasculitis, sarcoidosis, connective tissue disease, and uveitis were not observed. Disease-specific autoantibodies were negative, and the elevation of IgG4 and ACE levels was not confirmed. Histologically, no granuloma was present, and plasma cells were very few. According to these findings, the presented case was diagnosed with drug-induced AIN. In relation to clinical features, renal failure was severe as conventionally reported, and the maximum serum creatinine level was 6.81 mg/dL. Although extrarenal manifestations were accompanied by fever and erythema, eosinophilia was not observed in the peripheral blood. An increase in urinary interstitial-related markers suggested the presence of AIN, but leukocyturia and white blood cell casts were not noted.

The cause of this drug-induced AIN was considered from the timing of drug administration and the onset of kidney injury, suggesting the possibility of carboplatin, etoposide and TAZ/PIPC. The elevation of serum creatinine level, drug-related fever and bilateral renal enlargement confirmed by abdominal CT were already observed before TAZ/PIPC administration. For renal enlargement, bilateral pyelonephritis associated with sepsis was ruled out and was considered to be a finding related to AIN. There have been no reports of etoposide-related renal failure, and it was concluded that carboplatin was the causative agent of AIN. Unfortunately, drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test (DLST) has not been performed.

There is only one report of carboplatin-related AIN [12]. This article described two cases of AKI that developed after multiple intraperitoneal administrations of carboplatin for advanced ovarian tumors. A renal biopsy was performed and diagnosed with AIN. The peak serum creatinine levels of each patient showed severe AKI (9.0 mg/dL and 9.5 mg/dL) but were improved by steroid therapy. Similar to those cases, cisplatin was also given prior to carboplatin administration for our patient. An increase in the CRP level was observed at the same time after cisplatin and carboplatin administration, suggesting a drug-related event. Unlike the previous report [12], our case developed AIN after a single dose of carboplatin. He may have been sensitized by previous cisplatin use, so an allergic reaction may have occurred after the administration of carboplatin. Table 2 summarizes the review of previous report and comparison with this case regarding the clinical and pathological findings of AIN associated with carboplatin.

Table 2.

Review of previous report on carboplatin-related acute interstitial nephritis and comparison with this case

| Age | Sex | Malignancy | Treatment regimen of cisplatin administered before carboplatin | Treatment regimen of carboplatin | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Renal pathological features | Therapeutic intervention and renal prognosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | Female | Anaplastic ovarian carcinoma |

6 courses of intravenous therapy (60 mg/m2) 6 courses of intraperitoneal therapy (200 mg/m2) |

4 courses of intraperitoneal therapy (200 mg/m2 for the first course, and 300 mg/m2 for the next three cycles) | 0.9 → 8.2 within 7 days | In the interstitium, a moderate number of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils diffusely surrounding the tubules were infiltrated. The pathologic findings were consistent with focal, moderate interstitial nephritis | Oral prednisone was administered at a dose of 60 mg/day for 4 weeks. The serum creatinine decreased to 4.3 mg/dL | [12] |

| 62 | Female | Serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary |

6 courses of intravenous therapy (50 mg/m2) 6 courses of intraperitoneal therapy (200 mg/m2 for the first 4 cycles, and 100 mg/m2 for the last 2 treatments) |

5 courses of intraperitoneal therapy (200 mg/m2 for the first course, and 300 mg/m2 for the last 4 cycles) |

1.3 → 9.5 within 5 days | Marked tubular atrophy was present. The interstitium was markedly edematous and contained a mild, but diffuse, infiltration of mononuclear cells with focal areas of interstitial hemorrhage |

Prednisone at a dose of 60 mg/day was initiated orally for a 4-week course Finally, her serum creatinine recovered to 2.0 mg/dL |

[12] |

| 53 | Male | Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | 1 course of intravenous therapy (60 mg/m2) | 1 course of intravenous therapy (300 mg) | 1.24 → 6.81 within 8 days | A large number of inflammatory cells infiltrated into the interstitium. The major population of infiltrating cells was mononuclear cells. Eosinophils and plasma cells were few. Immunostaining of surface markers was observed mainly with CD3 and CD68 positive cells | Oral prednisolone was started at a dose of 40 mg/day. The steroids were remarkably effective, and the serum creatinine level decreased to 1.43 mg/dL 15 days after treatment | This case |

The renal pathological findings of drug-induced AIN are mainly based on inflammatory cell infiltration into the interstitium, and often tubulitis centering on the proximal tubule is observed. The spread of the lesion is usually diffuse but may be localized. These cellular infiltrations are replaced by fibrous tissue, and this fibrotic change appears as early as 7–10 days [10]. The infiltrating inflammatory cells are mainly composed of T lymphocytes and can include macrophages, eosinophils, and plasma cells. However, eosinophils are not necessarily observed in all cases, and it has been reported that blood eosinophil counts and interstitial eosinophil infiltration poorly correlated [10]. Cases with noncaseating granuloma are infrequent. The histopathological features of this case were consistent with AIN. Although at least 12 days had passed from the onset of AKI to renal biopsy, interstitial fibrosis was slight. A characteristic finding was the leakage of THP into the interstitium. While the disruption of TBM associated with severe tubular injury was observed, tubulitis was mild. It was suggested that a few eosinophils in the interstitium may be a result of the steroid treatment. There were almost no findings of ATN, and the influence of cisplatin was minor. The results of immunostaining for surface markers in infiltrating cells have been reported by accumulating omeprazole-induced AIN cases [13]. CD4-positive cells accounted for the majority of infiltrating cells and expression of IL-17 was observed. Th17-mediated inflammatory processes have been indicated as a mechanism of drug-induced AIN. Compared to this report, our case was similar in that there were more CD4-positive cells than CD8-positive cells. On the other hand, CD20-positive cells were relatively few, suggesting that cellular immunity was more predominant.

In cases of debatable drug-induced AIN, it is important to discontinue the suspected drugs as soon as possible. If renal function does not recover after 3–5 days of follow-up, the necessity of renal biopsy has been pointed out [14]. Renal biopsy is valuable in the diagnosis of AIN, exclusion of other diseases, decision-making on steroid treatment, and prediction of treatment responsiveness and renal prognosis. Although steroid treatment for AIN is controversial, in cases where renal failure progresses even after drug discontinuation, steroid administration is recommended if the interstitial fibrosis area is 75% or less [14]. In this case, kidney injury due to ATN related to the platinum complex was also considered, but AIN could be diagnosed in accordance with the pathological findings and steroid treatment was successful.

In summary, we experienced a case of drug-induced AIN associated with carboplatin. AKI after carboplatin administration has the potential not only for ATN but also for AIN; therefore, appropriate diagnosis by renal biopsy and indications for steroid treatment should be carefully considered.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the excellent technical assistance of M. Yamauchi, Y. Sugiyama, and Y. Watase. The authors also acknowledge Editage for providing editorial and publication support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests involving this work.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

No information identifying the individual patient is published, and personal information is protected. The patient family provided informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Akimasa Asai, Email: asai.akimasa.002@mail.aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Takayuki Katsuno, Email: t-katsuno@aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Makoto Yamaguchi, Email: yamaguchi.makoto.231@mail.aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Shiho Iwagaitsu, Email: iwagaitsu.shiho.230@mail.aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Hironobu Nobata, Email: nobata@aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Kinashi, Email: kinashi.hiroshi.909@mail.aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Kitamura, Email: kitamura.hiroshi.kw@mail.hosp.go.jp.

Shogo Banno, Email: sbannos@aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

Yasuhiko Ito, Email: yasuito@aichi-med-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Arany I, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:460–464. doi: 10.1016/S0270-9295(03)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobyan DC, Levi J, Jacobs C, Kosek J, Weiner MW. Mechanism of cis-platinum nephrotoxicity: II. Morphologic observations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980;213:551–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pabla N, Dong Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 2008;73:994–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Yokoo S, Katsura T, Inui K. Cisplatin and oxaliplatin, but not carboplatin and nedaplatin, are substrates for human organic cation transporters (SLC22A1-3 and multidrug and toxin extrusion family) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:879–886. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas M, Spargo BH, Wit EJ, Meehan SM. Etiologies and outcome of acute renal insufficiency in older adults a renal biopsy study of 259 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:433–447. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(00)70196-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Praga M, González E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2010;77:956–961. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker RJ, Pusey CD. The changing profile of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:8–11. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:461–470. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossert J. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60:804–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González E, Gutiérrez E, Galeano C, Chevia C, de Sequera P, Bernis C, Parra EG, Delgado R, Sanz M, Ortiz M, Goicoechea M, Quereda C, Olea T, Bouarich H, Hernández Y, Segovia B, Praga M. Early steroid treatment improves the recovery of renal function in patients with drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;73:940–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarkson MR, Giblin L, O'Connell FP, O'Kelly P, Walshe JJ, Conlon P, O'Meara Y, Dormon A, Campbell E, Donohoe J. Acute interstitial nephritis: clinical features and response to corticosteroid therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2778–2783. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald BR, Kirmani S, Vasquez M, Mehta RL. Acute renal failure associated with the use of intraperitoneal carboplatin: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1991;90:386–391. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90582-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berney-Meyer L, Hung N, Slatter T, Schollum JB, Kitching AR, Walker RJ. Omeprazole-induced acute interstitial nephritis: a possible Th1-Th17-mediated injury? Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19:359–365. doi: 10.1111/nep.12226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moledina DG, Perazella MA. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:2046–2049. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07630717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]