Abstract

Renal infarction is an uncommon condition resulting from an acute disruption of renal blood flow and it is potentially life-threatening disease. The cause and outcome of renal infarction is not well established and is frequently misdiagnosed or diagnosed late. Melanotan II is a non-selective melanocortin-receptor agonist and its effect on humans is an increasing of skin pigmentation, producing of spontaneous penile erection and sexual stimulation. Melanotan II inducing rhabdomyolysis and renal failure have been described previously. We present a review of Melanotan II and the possible effects of this drug on the kidneys by including a case of a renal infarction most likely attributed to Melanotan II. In the mechanism of renal injury with Melanotan II, thrombotic pharmacological influence and possible direct toxic effect on renal parenchyma must be considered.

Keywords: Renal infarction, Melanotan II, Kidney injury, Barbie drug

Introduction

The most common etiological and pathogenic causes of renal infarction include hypercoagulative states, cardioembolic disease, renal artery injury and idiopathic causes [1–4]. Here, we present a review of Melanotan II and the possible effects of this drug on the kidneys by including a case of a renal infarction most likely attributed to Melanotan II. Melanotan II also called “Barbie drug” [5] is mostly purchased illegally via Internet and its effect on humans is an increasing of skin pigmentation, producing of spontaneous penile erection and sexual stimulation [6]. Melanotan II is a non-selective melanocortin-receptor agonist and by this mechanism an alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone [7].

Case report

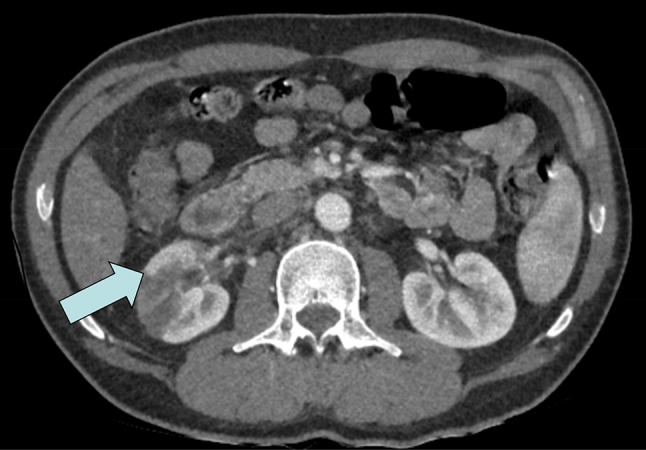

A previously healthy 45-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to the emergency room with right-sided abdominal pain, vomiting and increased frequency of voiding with no fever after a vacation in Southern Europe. Past medical history included gastroesophageal reflux which was symptom controlled with 20 mg Esomeprazole and a perforated appendectomy in childhood. He admitted to moderate alcohol consumption which increased during vacations. The condition is initially interpreted as renal colic with an ultrasound of the abdomen being reported as normal. The patient was discharged home with a single dose of Diclofenac (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug); however, he returned the next day with increasing pain and a new fever (38.5 °C). A computer tomography (CT) scan was performed which revealed a right sided renal infarction affecting approximately 50% of the kidney with marked decrease contrast enhancement and a minimal surrounding edema (Fig. 1). The renal arteries were considered to have a normal appearance and there was no evidence of renal stones or hydronephrosis. The pancreas, spleen, liver, adrenals and left kidney were of a normal appearance. Chlolelithiasis without signs of chlolecystitis was also noted. The patient is subsequently admitted to the department of nephrology for further investigation. It was noted that the patient had an intense tanning of his skin and an additional investigation revealed that he had administered a total of 27 mg of Melanotan II subcutaneously within the last 6 months for the purpose of increasing his suntan. The patient self administrated Melanotan II 10 mg per injection twice within a period of 6 months and 7 mg 3 weeks before the admission to the hospital. He obtained the medication via a web shop. A sample of the drug was provided by the patient for additional investigation at a forensic center and the presence of Melanotan II was confirmed and no other pharmacologic substances were revealed in the specimen. The patient underwent investigations of the cardiovascular system including a CT-scan of the aorta, echocardiography to rule out arrhythmias and a heart ultrasound. No sources for embolus were found. Although previously normotensive, his blood pressure was recorded at 165/95 mmHg. Abnormal hematological investigations included C-reactive protein 152 mg/L, serum creatinine 102 µmol/l, blood glucose 6 mmol/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1.96 µkat/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 1.23 µkat/L. Coagulative studies (international normalized ratio and activate partial thromboplastin time) and further coagulation analyses after a complementary contact with coagulation expertize revealed no abnormalities. Urinalysis by dipstick showed hemoglobin 1+. No signs for dehydration or rhabdomyolysis were found in this patient. Repeat AST and ALT were taken 2 weeks later and were reported to be within normal range. After 2 months an Iohexol-clearance-measurement was performed and showed a slightly reduced renal function (81 mL/min per 1.73 m2). The patient’s hypertension persisted and an Angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE)-inhibitor was introduced in the treatment. During the investigations the patient was treated with low molecular heparin, which was then stopped when all investigations were completed.

Fig. 1.

CT-scan of the right sided renal infarction

Discussion

The literature of pharmacologically induced renal infarctions is sparse [8]. Melanotan II inducing rhabdomyolysis and renal failure has been described previously where the systemic toxicity of Melanotan II with sympathomimetic excess causing renal dysfunction [6]. In the mechanism of renal injury, thrombotic pharmacological influences must be considered [8]. Melanotan II has five melanocortin receptor subtypes (MC-R) which reveal different biological functions based on localization [9]. In the skin and adrenal cortex, MC1-R and MC2-R are melanocytic and adrenocortical receptors [10–13]. Melanotan II stimulate the melanocytes in the skin (by stimulation of MC1-R) to increase the production of eumelanin which result in sunless tanning of the skin [5, 14, 15]. MC3-R is mostly expressed in the brain and digestive tract [13, 16], MC4-R is located in the nervous system [12, 13] and MC5-R is found in endo and exocrine glands [10, 11, 13]. The reported adverse effects relate to the location of the receptors are thus wide ranging including nausea, abdominal pain, anxiety, flushing, dizziness, headaches, appetite suppression, stomach pain, cramping, severe constipation, spontaneous penile erections, muscle pain and induction of cancer in the skin. The effects of Melanotan II can result in an overstimulation of the sympathic nervous system [6]. We believe that this vasoconstriction could possibly explain the mechanism of the renal infarction in our case report. Additional pharmacological considerations as a potential drug in the mechanism of renal injury include the proton pump inhibitor Esomeprazole [17] and Diclofenac, however, this was administered after the onset of the symptoms, but may have affected the renal function in the later phase of this case [18–20]. Complementary contact has been taken with the Swedish Poisons Information Centre and since January 1, 2008 until May 20, 2019, in total 215 cases (93% in adults) of given information to Melanotan II side effects were registered. No case of Melanotan II induced renal infarction has been reported to the Swedish Poisons Information Centre. To our knowledge, this case is the first that described the possible direct toxic effects of Melanotan II on renal parenchyma.

A limitation of this case report was that no examination of blood concentration of Melanotan II or its metabolites was performed at admission. It is known that this drug can be detected by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. However, there exists no routine for this in our country.

In conclusion, Melanotan II inducing rhabdomyolysis and renal failure has been described previously. In the mechanism of renal injury with Melanotan II, thrombotic pharmacological influence and possible direct toxic effect on renal parenchyma must be considered.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chu PL, Wei YF, Huang JW, Chen SI, Chu TS, Wu KD. Clinical characteristics of patients with segmental renal infarction. Nephrology (Carlton) 2006;11(4):336–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolderman R, Oyen R, Verrijcken A, Knockaert D, Vanderschueren S. Idiopathic renal infarction. Am J Med. 2006;119(4):356.e9–356.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumerman JH, Hom D, Eiley D, Smith AD. Heightened suspicion and rapid evaluation with CT for early diagnosis of partial renal infarction. J Endourol. 1999;13(3):209–214. doi: 10.1089/end.1999.13.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazanov N, Somin M, Attali M, Beilinson N, Thaler M, Mouallem M, Maor Y, Zaks N, Malnick S. Acute renal embolism. Forty-four cases of renal infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83(5):292–299. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000141097.08000.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langan EA, Nie Z, Rhodes LE. Melanotropic peptides: more than just ‘Barbie drugs’ and ‘sun-tan jabs’? Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):451–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson ME, Bryant SM, Aks SE. Melanotan II injection resulting in systemic toxicity and rhabdomyolysis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012;50(10):1169–1173. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2012.740637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan D. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(5):2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bemanian S, Motallebi M, Nosrati SM. Cocaine-induced renal infarction: report of a case and review of the literature. BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertolini A, Vergoni W, Gessa GL, Ferrari W. Induction of sexual excitement by the action of adrenocorticotrophic hormone in brain. Nature. 1969;221(5181):667–669. doi: 10.1038/221667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chhajlani V, Wikberg JE. Molecular cloning and expression of the human melanocyte stimulating hormone receptor cDNA. FEBS Lett. 1992;309(3):417–420. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80820-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine N, Sheftel SN, Eytan T, Dorr RT, Hadley ME, Weinrach JC, Ertl GA, Toth K, McGee DL, Hruby VJ. Induction of skin tanning by subcutaneous administration of a potent synthetic melanotropin. JAMA. 1991;266(19):2730–2736. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470190078033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Cone RD. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science. 1992;257(5074):1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1325670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wessells H, Levine N, Hadley ME, Dorr R, Hruby V. Melanocortin receptor agonists, penile erection, and sexual motivation: human studies with Melanotan II. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12(Suppl 4):S74–S79. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cousen P, Colver G, Helbling I. Eruptive melanocytic naevi following melanotan injection. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):707–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardones AR, Grichnik JM. α-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone-induced eruptive nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(4):441–444. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argiolas A, Melis MR, Gessa GL. Central dopamine-oxytocin-adrenocorticotropin link in the expression of yawning and penile erection. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 1988;24(3):377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, George KC, Shang WF, Zeng R, Ge SW, Xu G. Proton-pump inhibitors use, and risk of acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1291–1299. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S130568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Berko NS, Gothwal R, Tamarin F, Jesmajian SS. Kounis syndrome secondary to ibuprofen use. Int J Cardiol. 2009;137(3):e79–e80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramot Y, Nyska A. Drug-induced thrombosis–experimental, clinical, and mechanistic considerations. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(2):208–225. doi: 10.1080/01926230601156237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steciwko A, Reksa D, Grotowska M. Endothelium and its role in pathogenesis of diseases. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2006;116(3):819–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]