Abstract

There are few case reports in which circulating levels of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), placental growth factor (PlGF), and soluble endoglin (sEng) were measured before the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia in women with hemodialysis. A 40-year-old Japanese nulliparous women with hemodialysis due to diabetic nephropathy became pregnant by frozen embryo transfer. Intensive hemodialysis was started at 5 weeks of gestation. Her blood pressure (BP) in the first trimester was around 130/80 mmHg. At 20+3 weeks, she was admitted for close monitoring; her BP was 137/75 mmHg. Her BP increased to 157/88 mmHg at 31+2 weeks, and nifedipine at 20 mg/day was started at 31+6 weeks. However, the serial longitudinal measurements of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng did not predict the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia. Cesarean section was performed at 33+6 weeks due to uncontrollable hypertension. A healthy female infant weighing 2138 g was delivered. As for the changes of biomarkers between just before and just after hemodialysis, sFlt-1 was significantly higher just after compared with just before hemodialysis (5774 ± 1875 pg/mL vs. 2960 ± 905 pg/mL, respectively, p < 0.001). PlGF was also significantly higher just after compared with just before hemodialysis (2227 ± 1038 pg/mL vs. 1377 ± 614 pg/mL, respectively, p < 0.001). However, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio and sEng levels were not significantly different between just before and just after hemodialysis (p = 0.115, p = 0.672, respectively). In conclusion, prediction of early-onset super-imposed preeclampsia using angiogenic and anti-angiogenic markers in pregnant women with hemodialysis might be difficult.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, Soluble endoglin, Placental growth factor, Preeclampsia

Introduction

The incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant women with dialysis is very high [1]: the occurrence rates of preeclampsia in pregnant women with dialysis were reported as 20–66% [2–5]. In women with dialysis, not only preeclampsia but also severe hypertension often occurs [6]. Recent systematic reviews concluded that intensive hemodialysis may improve pregnancy outcomes [6–8]. Although angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors, such as placental growth factor (PlGF), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), and soluble endoglin (sEng), are associated with the onset of preeclampsia [9–12], there are few case reports in which circulating levels of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng were measured before the onset of hypertension in women with hemodialysis [13–15]. Unfortunately, previous studies failed to predict super-imposed preeclampsia on chronic nephritis with hemodislysis [13–15]. Therefore, it is unknown whether the measurement of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors is clinically useful to predict the onset of preeclampsia in pregnant women with hemodialysis as well as pregnant women without hemodialysis. Thus, we examined whether longitudinal monitoring of these biomarkers could predict the occurrence of super-imposed preeclampsia in a pregnant woman with hemodialysis due to diabetic nephropathy.

In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there were no reports on the changes of sEng after dialysis [16, 17]. In this study, we examined the changes of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng from just before until just after hemodialysis during pregnancy in the same woman.

Case report

A 40-year-old Japanese nulliparous women, who had been treated with hemodialysis (3 times per week and 5 h per every treatment) due to diabetic nephropathy from 32 years old, consulted us with letter of introduction from a nephrologist in our hospital. She had long-term infertility and hoped to become pregnant by assisted reproductive technology. Her mother and brother had non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. She had developed non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus at 14 years old. Her other past histories were hyperprolactinemia, left ovarian cyst, and diabetic retinopathy with photocoagulation, but she was not complicated with hypertension. She had not smoking habit. She had been prescribed as follows: menatetrenone 45 mg/day, Vitamedin® combination capsules 3 capsules/day, calcitrol 0.25 μg/day, folic acid 5 mg/week, insulin aspart (NovoRapid®) 3, 2, and 2 units s.c. just before breakfast, supper, dinner, respectively, and insulin detemir (Levemir®) 8 units s.c. at bedtime. We decided that her hemodialysis times should be lengthened from 15 to 30 h per week (5 times per week and 6 h per treatment) and she soon became pregnant by frozen embryo transfer. Intensive hemodialysis was started at 5 weeks of gestation. Her body mass index just before pregnancy was 21.9, and her blood pressure (BP) was around 130/80 mmHg. Low dose aspirin of 100 mg/day was started soon after pregnancy and was continued until 32+1 weeks. Her prescription of insulin was changed after pregnancy; and final dose of insulin during pregnancy was as follows: Insulin aspart 12, 14, and 4 units s.c. just before breakfast, supper, dinner, respectively, at day of hemodialysis, whereas insulin aspart 10, 5, and 5 units s.c. just before breakfast, supper, dinner, respectively, at day of non-hemodialysis; and insulin detemir 3 units s.c. at bedtime irrespective hemodialysis. Her HbA1c values during pregnancy were within normal range. At 20 weeks and 3 days, she was admitted for close monitoring; her BP was 137/75 mmHg. Her BP increased to 157/88 mmHg at 31+2 weeks, and nifedipine at 20 mg/day was started at 31+6 weeks. Lansopazole of 15 mg/day was started at 26+6 weeks due to reflex esophagitis. At 33+5 weeks, she abruptly vomited intestinal juice and became appetite loss with high systolic blood pressure level of > 180 mmHg. HELLP syndrome was ruled out by laboratory findings. Cesarean section was performed at 33+6 weeks due to uncontrollable hypertension and severe appetite loss. A healthy female infant weighing 2138 g was delivered. Nausea and vomiting disappeared after operation, and she soon recovered her appetite. Hemodialysis was returned to the pre-pregnancy method (15 h per week) after delivery. Hypertension was alleviated without medication 11 days after delivery. Her blood pressure at 1 month after delivery was almost normal range without prescription of anti-hypertensive drugs. Dose of insulin was controlled using sliding scale after delivery, and final prescription of insulin was set to insulin aspart 3, 3, and 4 units s.c. just before breakfast, supper, dinner, respectively, and insulin detemir 3 units s.c. at bedtime, irrespective hemodialysis.

After obtaining written informed consent, serial blood samplings just before and just after hemodialysis were performed from 21+5 to 33+5 weeks of gestation, once or twice per week and at one day before delivery. Serum samples were stored at − 20 °C until use. sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Since we previously constructed gestational-age specific reference ranges of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng during 20–38 weeks of gestation [18], the levels of < 5% for PlGF and ≥ 95% for sFlt-1, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, and sEng were adopted as cut-off values. The serial longitudinal measurements of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng did not predict the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia, although the levels of sFlt-1 and sEng were increased after the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal changes in serum levels of sFlt-1, PlGF, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, and sEng using the values just before hemodialysis. Solid curves indicate 5th and 95th percentiles of these biomarkers, and the dashed curves indicate the mean of these biomarkers. sFlt-1 soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, PlGF placental growth factor, sEng soluble endoglin, HT hypertension, C/S cesarean section

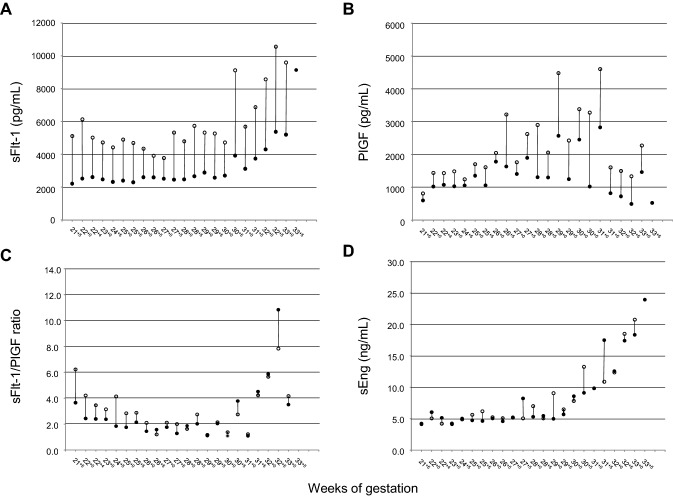

As for the changes of sFlt-1, PlGF, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, and sEng, sFlt-1 was significantly higher just after compared with just before hemodialysis (5774 ± 1875 pg/mL vs. 2960 ± 905 pg/mL, respectively, p < 0.001 by the paired t test using IBM SPSS Statistics [version 25]) (Fig. 2); PlGF was also significantly higher just after compared with just before hemodialysis (2227 ± 1038 pg/mL vs. 1377 ± 614 pg/mL, respectively, p < 0.001); however, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio and sEng levels were not significantly different between just before and just after hemodialysis (p = 0.115, p = 0.672, respectively).

Fig. 2.

The levels of sFlt-1, PlGF, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio, and sEng at just before and just after dialysis during 21 and 33 weeks of gestation, and at 1 day before delivery in a pregnant woman with hemodialysis due to diabetic nephropathy. The closed circle indicates the value just before hemodialysis, and the open circle indicates that just after hemodialysis. Circles on the same day are connected by a solid line. sFlt-1 soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1, PlGF placental growth factor, sEng soluble endoglin

Discussion

In our case, the serial longitudinal measurements of sFlt-1, PlGF, and sEng did not predict the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia in a woman with hemodialysis due to diabetic nephropathy. To the best of our knowledge, there are three case reports in which circulating levels of sFlt-1, PlGF, or sEng were measured before the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia in women with hemodialysis [13–15]. Shan et al. [13] reported a woman undergoing hemodialysis in whom BP suddenly increased at 29 weeks; the plasma levels of sFlt-1 and sEng at 29 weeks were within normal levels for pregnancy. Cornelis et al. [14] reported a woman with IgA nephropathy whose kidney function progressively decreased during pregnancy resulting in initiating intensive hemodialysis at 26 weeks; at 35+5 weeks, she developed sudden, unexplained hypertension; the serum levels of sFlt-1 and PlGF during 21 and 35 weeks were within normal ranges of these markers. Akbari et al. [15] reported a woman with interstitial nephritis who had a kidney transplant, but became a failure later due to membranous nephropathy; then she had hemodialysis, and became pregnant; at 35 weeks, hypertension occurred; serum levels of sFlt-1 at 32,33, and 34 weeks were within normal range, and the serum levels of PlGF at 32, 33, and 34 weeks were relatively higher than the normal ranges of PlGF. Thus, in all cases including our case, sFlt-1, PlGF, or sEng did not predict the onset of super-imposed preeclampsia [13–15]. Therefore, the mechanism of the occurrence of super-imposed preeclampsia during pregnancy in pregnant patients with hemodialysis might be different from that in pregnant women without hemodialysis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the changes of sEng after hemodialysis in a pregnant woman. The sEng levels were not significantly different between just before and just after hemodialysis during pregnancy. In this case, hemodialysis was performed using a hemodiafiltration filter (ABH-21P, Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd., Japan), thus this filter did not have an ability to eliminate sFlt-1 from the maternal circulation. Heparin sulfate was given for anticoagulation during hemodialysis. In our case, both sFlt-1 and PlGF were significantly higher just after compared with just before hemodialysis. The increases of sFlt-1 and PlGF after hemodialysis were already reported [16, 17]. Serum levels of sFlt-1 2 h after the administration of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) increased by 26% compared with those 2 h before its administration, and serum levels of PlGF 2 h after the administration of LMWH also increased by 15% compared with those 2 h before its administration [17]. Therefore, the increases of sFlt-1 and PlGF after hemodialysis can be explained by the addition of heparin during hemodialysis. Why the levels of sFlt-1 or PlGF were increased by the addition of heparin during hemodialysis? We suggest that sFlt-1 bound to heparin sulfate proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix may be released into the circulation by heparin treatment [17], whereas PlGF may be released from placental villi [19, 20]. Hagmann et al. [17] executed biochemical binding studies employing cation exchange chromatography in patients’ samples; the percentage of sFlt-1 bound to the cation exchange matrix was significantly decreased from 70% to 57% after addition of enoxaparin at a concentration of 10 mg/L, suggesting that low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) may mask the positive charge in the sFlt-1 bound to negatively charged heparin sulfate proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix, and may facilitate the release of sFlt-1 into the circulation. Drewlo et al. [20] exposed first trimester placental villi and term placental explants to LMWH; LMWH treatments of 0.25 IU/mL, 2.5 IU/mL, and 25 IU/mL increased the release of sFlt-1 compared with control; in addition, LMWH treatments of 0.25 IU/mL, 2.5 IU/mL, and 25 IU/mL for first trimester placental villi increased the release of PlGF dose-dependently; however, LMWH treatments did not show significant changes of the release of sEng by any concentrations of LMWH. These results suggest that heparin may have direct effect of increasing the concentration of both sFlt-1 and PlGF, but not sEng, against trophoblasts.

In conclusion, prediction of early-onset super-imposed preeclampsia using angiogenic and anti-angiogenic biomarkers in pregnant women with hemodialysis might be difficult. In addition, hemodialysis may affect serum levels of sFlt-1 and PlGF, but not sEng. The accumulation of reports on women with hemodialysis is necessary to elucidate the importance of measuring angiogenesis-related factors to predict the occurrence of super-imposed preeclampsia.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid (24592482 and 17K11247 to A.O.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and animal rights

This is a research involving a human being. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee at which the studies were conducted (IRB approval number: Dai-I-17-Hen-29-Gou) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

A written informed consent was gained from the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hiroyuki Morisawa and Chikako Hirashima contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Hirose N, Ohkuchi A, Usui R, Matsubara S, Suzuki M. Risk of preeclampsia in women with CKD, dialysis or kidney transplantation. Med J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2:1028. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luders C, Castro MC, Titan SM, De Castro I, Elias RM, Abensur H, Romão JE., Jr Obstetric outcome in pregnant women on long-term dialysis: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:77–85. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahir AK, Briggs N, Katsoulis J, Levidiotis V. An observational outcomes study from 1966–2008, examining pregnancy and neonatal outcomes from dialysed women using data from the ANZDATA Registry. Nephrol (Carlton) 2013;18:276–284. doi: 10.1111/nep.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eroğlu D, Lembet A, Ozdemir FN, Ergin T, Kazanci F, Kuşcu E, Haberal M. Pregnancy during hemodialysis: perinatal outcome in our cases. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik GH, Al-Harbi A, Al-Mohaya S, Dohaimi H, Kechrid M, Shetaia MS, Al-Hassan AO, Quiapos LS. Pregnancy in patients on dialysis–experience at a referral center. J Assoc Phys India. 2005;53:937–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piccoli GB, Conijn A, Consiglio V, Vasario E, Attini R, Deagostini MC, Bontempo S, Todros T. Pregnancy in dialysis patients: is the evidence strong enough to lead us to change our counseling policy? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:62–71. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05660809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccoli GB, Minelli F, Versino E, Cabiddu G, Attini R, Vigotti FN, Rolfo A, Giuffrida D, Colombi N, Pani A, Todros T. Pregnancy in dialysis patients in the new millennium: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis correlating dialysis schedules and pregnancy outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1915–1934. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiles K, de Oliveira L. Dialysis in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;57:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, Sibai BM, Epstein FH, Romero R, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA, CPEP Study Group Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkuchi A, Hirashima C, Matsubara S, Takahashi K, Matsuda Y, Suzuki M. Threshold of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1/placental growth factor ratio for the imminent onset of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2011;58:859–866. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.174417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohkuchi A, Hirashima C, Takahashi K, Suzuki H, Matsubara S, Suzuki M. Onset threshold of the plasma levels of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1/placental growth factor ratio for predicting the imminent onset of preeclampsia within 4 weeks after blood sampling at 19-31 weeks of gestation. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan HY, Rana S, Epstein FH, Stillman IE, Karumanchi SA, Williams ME. Use of circulating antiangiogenic factors to differentiate other hypertensive disorders from preeclampsia in a pregnant woman on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:1029–1032. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelis T, Spaanderman M, Beerenhout C, Perschel FH, Verlohren S, Schalkwijk CG, van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, Hladunewich M. Antiangiogenic factors and maternal hemodynamics during intensive hemodialysis in pregnancy. Hemodial Int. 2013;17:639–643. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akbari A, Hladunewich M, Burns K, Moretti F, Arkoub RA, Brown P, Hiremath S. Circulating angiogenic factors in a pregnant woman on intensive hemodialysis: a case report. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2016;3:7. doi: 10.1186/s40697-016-0096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavainne F, Meffray E, Pepper RJ, Néel M, Delcroix C, Salama AD, Fakhouri F. Heparin use during dialysis sessions induces an increase in the antiangiogenic factor soluble Flt1. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:1225–1231. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagmann H, Bossung V, Belaidi AA, Fridman A, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R, Schermer B, Mallmann P, Schwarz G, Benzing T, Brinkkoetter PT. Low-molecular weight heparin increases circulating sFlt-1 levels and enhances urinary elimination. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e85258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirashima C, Ohkuchi A, Takahashi K, Suzuki H, Yoshida M, Ohmaru T, Eguchi K, Ariga H, Matsubara S, Suzuki M. Gestational hypertension as a subclinical preeclampsia in view of serum levels of angiogenesis-related factors. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:212–217. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yinon Y, Ben Meir E, Margolis L, Lipitz S, Schiff E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Simchen MJ. Low molecular weight heparin therapy during pregnancy is associated with elevated circulatory levels of placental growth factor. Placenta. 2015;36:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drewlo S, Levytska K, Sobel M, Baczyk D, Lye SJ, Kingdom JC. Heparin promotes soluble VEGF receptor expression in human placental villi to impair endothelial VEGF signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2486–2497. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]