Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) surrounding cancer cells becomes stiffer during tumor progression, which influences cancer cell behaviors such as invasion and proliferation through modulation of gene expression as well as remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. In this study, we show that MMP24 encoding matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-24 is a novel target gene of Yes-associated protein (YAP), a transcription coactivator known as a mechanotransducer. We first examined the effect of substrate stiffness on MMP24 expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells and showed that the expression of MMP24 was significantly higher in cells grown on stiff substrates than that on soft substrates. The MMP24 expression was significantly reduced by knockdown of YAP. In contrast, the expression of constitutively active YAP increased MMP24 promoter activity. In addition, binding of YAP to the MMP24 promoter was confirmed by the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. These results show that ECM stiffening promotes YAP activation, thereby inducing MMP24 expression. Based on the Human Protein Atlas database, breast cancer patients with lower MMP24 expression exhibit the worse survival rates overall. Thus, MMP24 may negatively regulate the aggressiveness of cancer cells under the stiff ECM environment during tumor progression.

Keywords: MMP, YAP, ECM, mechanical signal transduction, cancer progression, prognosis

1. Introduction

The mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) surrounding cancer cells are altered in the process of tumor progression. Secretion of ECM proteins by cancer-associated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment causes stiffening of the ECM [1,2]. The increase in ECM stiffness modulates cancer cell behaviors via the alteration of both migration and gene expression, wherein remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton plays an integral role. Binding of the ECM to integrins, transmembrane receptors for ECM proteins, activates Rho GTPases and thereby promotes actin polymerization and myosin activation [3,4,5,6]. Rigid ECM enhances this integrin signaling, leading to an increase in actin filament formation. Interaction of Yes-associated protein (YAP) and angiomotin (AMOT), which sequesters YAP in the cytoplasm, is attenuated by F-actin association to AMOT, resulting in the nuclear translocation of YAP [7,8]. Our previous study using MCF-7 cells has shown that an increase in actomyosin activity upregulates YAP-dependent gene expression [9,10].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) belong to a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases and are categorized into two distinct classes: soluble MMPs and membrane-type (MT) MMPs [11]. MT-MMPs cleave not only the ECM but also other substrates including prototype MMPs [12]. Substrates of MMP24, also known as MT5-MMP, include ECM proteins such as gelatin and fibronectin, N-cadherin, amyloid precursor protein and MMP2 [12,13,14]. MMP24 is dominantly expressed in neuronal cells and the function of MMP24 in Alzheimer’s disease has been well studied. However, little is known about the role of MMP24 in cancer—particularly breast cancer.

Here, we showed that substrate stiffening enhances YAP-dependent MMP24 expression through the activation of actomyosin contraction. Breast cancer patients with lower MMP24 expression show lower survival rates. Considering that cancer cell behaviors such as invasion and proliferation are often promoted in response to rigid substrates, MMP24 is likely to act as a negative regulator for cancer progression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Materials

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells and 293T human embryonic kidney cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2. N-acryloyl-6-aminocaproic acid-copolymerized acrylamide gels for polyacrylamide culture substrates were prepared as described previously [15,16]. Latrunculin A and blebbistatin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Merck Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA), respectively. An 8× GTIIC-luciferase plasmid obtained from Addgene contains 8× TEAD binding sites. pCS2-YAP 5SA, a gift from Dr. Hiroshi Nishina, expresses a constitutive active form of YAP, and contains the insert phosphorylation-defective YAP 5SA mutant.

2.2. Retroviral Vectors and Retroviral Infection

The retrovirus vectors encoding small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against human YAP and human ROCK2, the YAP target sequences #1: 5′-GCCACCAAGCTAGATAAAGAA-3′, #2: 5′-GACATCTTCTGGTCAGAGA-3′ and ROCK2 target sequence: 5′-GGTTTATGCTATGAAGCTT-3′, were cloned into the pSuper retro puro vector (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA, USA) and pSuper retro hygro vector [10], respectively. Retroviral infection was performed as described previously [16]. The cells were selected using puromycin (1.5 μg/mL) or hygromycin (300 μg/mL) for 3 days.

2.3. Luciferase Assay

The reporter construct MMP24-luc was generated by sub-cloning the PCR-amplified fragment encompassing the promoter region (−1010 to +3) of the human MMP24 gene into the pGL3-basic vector. The control plasmid phRL-TK (Renilla luciferase reporter) was obtained from Toyobo (Osaka, Japan). Luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was purified using NucleoSpin RNA kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). cDNA was prepared using PrimeScript 1st strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed with Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) under the following conditions: 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 55 °C for 1 min using StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used: human YAP forward 5′-AGGAGAGACTGCGGTTGAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCCAGGAGAAGACACTGCAT-3′; human MMP24 forward 5′-GCAGAAGGTGACCCCACTGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CATTTCCTAGCGTCCATGGC-3′; human MMP7 forward 5′-GGGCAAAGAGATCCCCCTGCAT-3′ and reverse 5′-CCCAGGCGCAAAGGCATGAG-3′; human CTGF forward 5′-ACCGACTGGAAGACACGTTTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CCAGGTCAGCTTCGCAAGG-3′; human ROCK2 forward 5′-CAACTGTGAGGCTTGTATGAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGCAAGGTGCTATAATCTCCTC-3′, and human ubiquitin forward 5′-TGACTACAACATCCAGAA-3′ and reverse 5′-ATCTTTGCCTTGACATTC-3′.

2.5. Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were fixed with 4% PFA and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking with 2% BSA in phosphatase buffered saline (PBS), the cells were incubated with the anti-YAP rabbit polyclonal antibody (D8H1X; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes Carlsbad, CA) was used as a secondary antibody. DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) was used to stain nuclei. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (LSM700; Zeiss) and then analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH).

2.6. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The assay was performed as described previously [10]. Cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-YAP rabbit polyclonal antibody (D8H1X; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or normal rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) antibodies. Precipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. The following primers were used to amplify the human MMP24 promoter region −689 to −460 containing the predicted TEAD-binding sequence: forward 5′-GATCTTCCCAGCTGGATGAGC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTAAAGGCGGGGTTCGAGAG-3′.

2.7. ChIP-Seq Database Analysis

Genome-wide occupancy dataset for TEAD4 in MCF-7 cells was obtained from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) consortium with track names MCF-7 TEAD4_V11_1 and _2. ChIP analysis was performed using anti-TEAD4 antibody (SantaCruz Biotechnology, sc-101184, Lot A1811) and the ChIP-seq data was mapped to the NCBI GRCh37/hg19 human genome sequence. The ENCODE dataset was visualized using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html).

2.8. The Human Protein Atlas Analysis

Correlations between MMP24 or MMP7 expression and the survival rate of breast, lung, pancreatic, renal and colorectal cancer patients were analyzed using the Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org) [17].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using the unpaired Student’s two-sided t-test.

3. Results

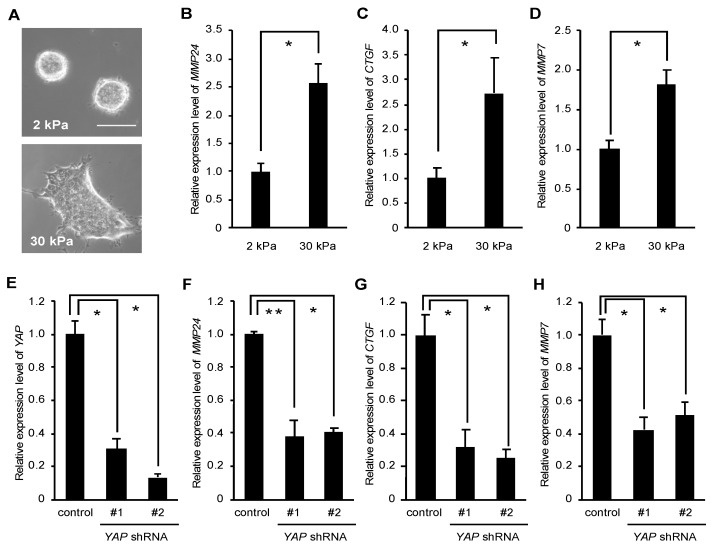

Using a microarray to compare the gene expression profile of T84 human colorectal cancer cells grown on stiff versus soft substrates, Nukuda et al. showed that the expression level of several MMPs including MMP24 was elevated when cells were cultured on stiff substrates [18]. We wondered whether rigid substrates also promote MMP24 expression in breast cancer cells. As shown previously, MCF-7 human breast cancer cells cultured on the soft substrate (2 kPa) formed spheroids and those cultured on the rigid substrate (30 kPa) were spread out (Figure 1A), indicating that MCF-7 cells sense and respond to the differential stiffness between 2 kPa and 30 kPa. Using quantitative real time PCR, we observed that the expression level of MMP24 was significantly higher in cells grown on the rigid substrate compared to those on the soft substrate (Figure 1B). Similarly, the expression levels of two YAP target genes, CTGF and MMP7, were also elevated in cells grown on the rigid substrate (Figure 1C,D). We have previously shown that rigid substrates promote YAP-dependent transcription in MCF-7 cells [9,10]. We therefore examined whether YAP regulated MMP24 expression. To this end, we depleted YAP expression using two shRNAs against human YAP (Figure 1E) and evaluated the expression of MMP24 and CTGF, a well-known YAP target gene, in cells grown on plastic dishes, i.e., rigid substrates (elastic modulus ~106 kPa). We observed that YAP knockdown caused ~2.5-fold reduction, ~3.3-fold reduction and ~2-fold reduction in the MMP24, CTGF and MMP7 expression levels, respectively (Figure 1F–H).

Figure 1.

Yes-associated protein (YAP) mediates MMP24 expression induced by stiffening substrates. (A–D) MCF-7 cells were cultured on substrates with elasticities of 2 and 30 kPa. Phase contrast images of the cells were obtained with an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41). Scale bar, 50 μm (A). The expression of MMP24 (B), CTGF (C) and MMP7 (D) were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.005. (E–H) Cells were infected with a control, YAP shRNA-#1, or -#2-expressing retrovirus. The expression of YAP (E), MMP24 (F), CTGF (G), and MMP7 (H) were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.005. Double asterisk represents p < 0.01.

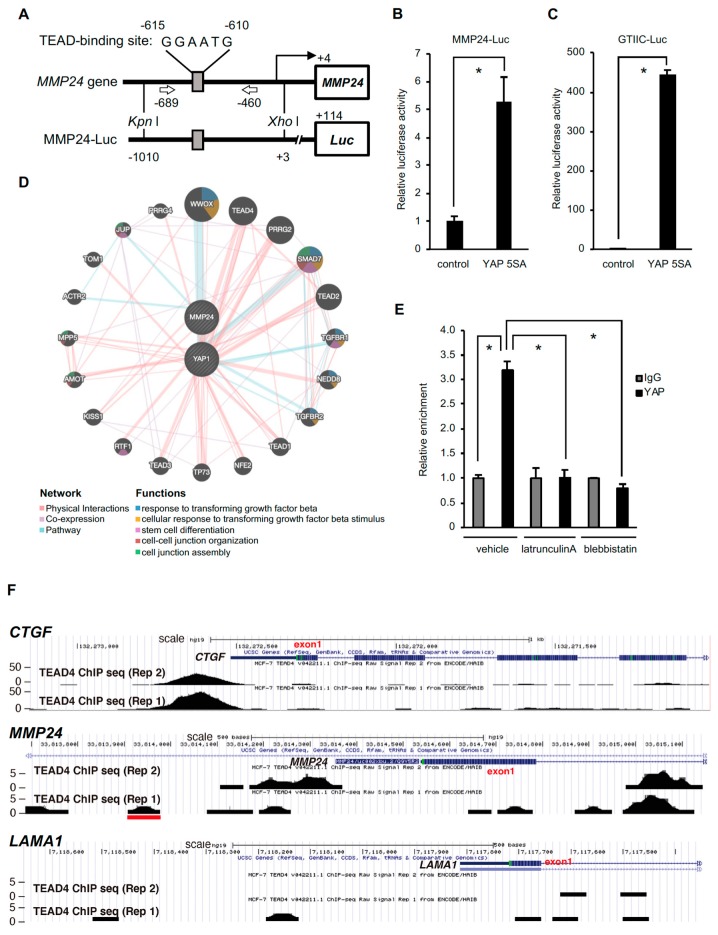

The MMP24 gene has the TEA domain (TEAD) recognition sequence GGAATG at −610 to −605 upstream of the transcription start site, and YAP may bind to this sequence through TEAD (Figure 2A). We then constructed a luciferase reporter plasmid containing the region −1010 to +3 of the MMP24 gene and used it to examine the role of YAP in the MMP24 promoter activation. Ectopic expression of the constitutive active form of YAP (YAP 5SA) increased the MMP24 promoter activity (Figure 2B) as well as the TEAD-dependent reporter activity (Figure 2C). In addition, the signal pathway analysis using the public database GeneMANIA suggests a link between MMP24 and YAP (Figure 2D). We then performed ChIP assay to confirm the binding of YAP to the MMP24 promoter and found that the amount of precipitated DNA of the MMP24 promoter region (−689 to −460) containing the predicted TEAD-binding sequence, using anti-YAP antibody, was significantly higher than that using anti-IgG antibody as a negative control (Figure 2E). Furthermore, analysis using the UCSC Genome Browser showed that TEAD4 binds to the CTGF and MMP24 promoters but not LAMINA promoter, which was used as a negative control (Figure 2F). Peak TEAD4 binding was observed in the region containing the predicted TEAD-binding sequence of the MMP24 promoter (Figure 2F, middle, red line). All these results indicate that MMP24 is a target gene of YAP-TEAD.

Figure 2.

Binding of YAP to the MMP24 promoter is decreased by inhibition of actomyosin contractility. (A) Location of TEAD-binding sequences within the MMP24 promoter and the luciferase reporter gene construct. TEAD-binding sequences within the MMP24 promoter are shown (top). The MMP24-Luc reporter plasmid contains the promoter region of the human MMP24 gene located at position −1010 to +3. (B) The pCS2-YAP 5SA expression vector was co-transfected with the reporter plasmid into 293T cells. Luciferase activity was measured 24 hours after transfection. The activity was normalized to that of the control vector. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.05. (C) A TEAD-responsive element luciferase reporter plasmid (8× GTIIC-Luc) was used as a control. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.005. (D) Predicted network for YAP and MMP24 was created using the GeneMANIA online software at http://www.genemania.org/. A graphic representation of how YAP and MMP24 are related to each other and to other genes in terms of physical interactions, pathways, and co-expression is shown in [19]. (E) MCF-7 cells were treated with 200 nM latrunculin A or 50 μM blebbistatin for 40 min. The binding of YAP to the MMP24 promoter was evaluated by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay followed by quantitative real-time PCR. The position of the primers is indicated by arrows in (A). Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.005. (F) The UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html) results show the locations of TEAD4 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-Seq signals on the CTGF, MMP24 or LAMA1 locus. TEAD4 ChIP-Seq data from MCF-7 cells was obtained from the ENCODE consortium. Two replicated results are shown. The red line indicates the human MMP24 promoter region (approximately −590 to −650) containing the predicted TEAD-binding sequence.

Even though the binding of TEAD4 to the MMP24 promoter was weaker than that to the CTGF promoter (Figure 2F), the effect of substrate stiffness or YAP knockdown on MMP24 expression was similar to that on CTGF expression (Figure 1B vs. Figure 1C, Figure 1 F vs. Figure 1 G, respectively). Notably, TEAD4 also binds to intron 1 of the MMP24 gene (Figure 2F, upper vs. middle). Thus, YAP and TEAD may upregulate MMP24 expression by their binding not only to the promoter but also to intron 1 of MMP24.

The nuclear translocation of YAP has been shown to be dependent upon actomyosin contractility [7,8,9,10]. We thus set out to investigate the role of actomyosin in the interaction between YAP and the MMP24 promoter. Treatment with latrunculin A, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, or blebbistatin, a myosin II inhibitor, diminished the binding of YAP to the MMP24 promoter (Figure 2E), indicating the importance of actomyosin activity for YAP-dependent MMP24 expression.

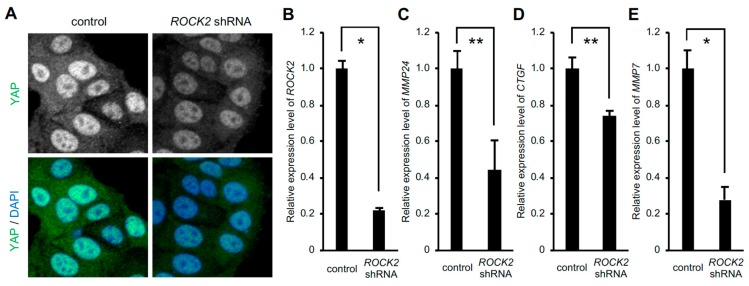

We have demonstrated that expression of the gene encoding Rho-associated coiled coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK) 2, which induces the activation of myosin II, is increased in response to the rigid substrate in a YAP-TEAD dependent manner [9]. On the other hand, nuclear accumulation of YAP, in turn, depends on ROCK2 expression, as shown previously [10] and in Figure 3A. Therefore, we wondered whether ROCK2 played a role in the expression of MMP24 in cells cultured on the rigid substrate. Knockdown of ROCK2 significantly reduced expression levels of MMP24 as well as CTGF and MMP7 (Figure 3B–E), indicating that ROCK2 was involved in YAP-dependent MMP24 expression.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of ROCK2 decreases MMP24 expression. Cells were infected with ROCK2 shRNA-expressing retrovirus. Confocal images of cells stained for YAP (green) and DAPI (blue) are shown (A). The expression of ROCK2 (B), MMP24 (C), CTGF (D), and MMP7 (E) were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D.; n = 3. Asterisks represent p < 0.005. Double asterisks represent p < 0.01.

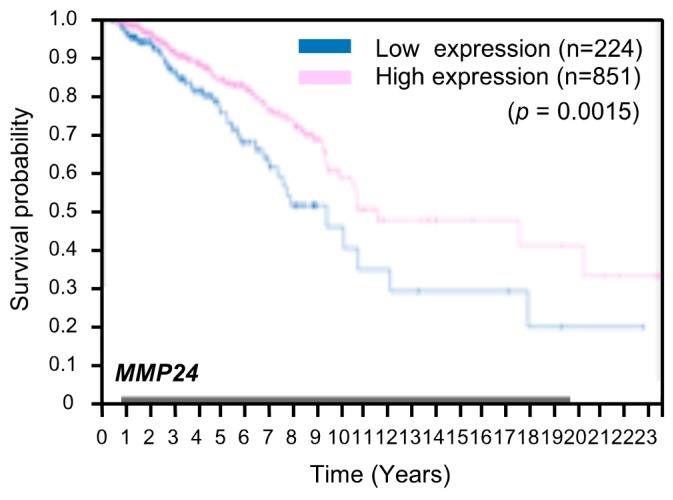

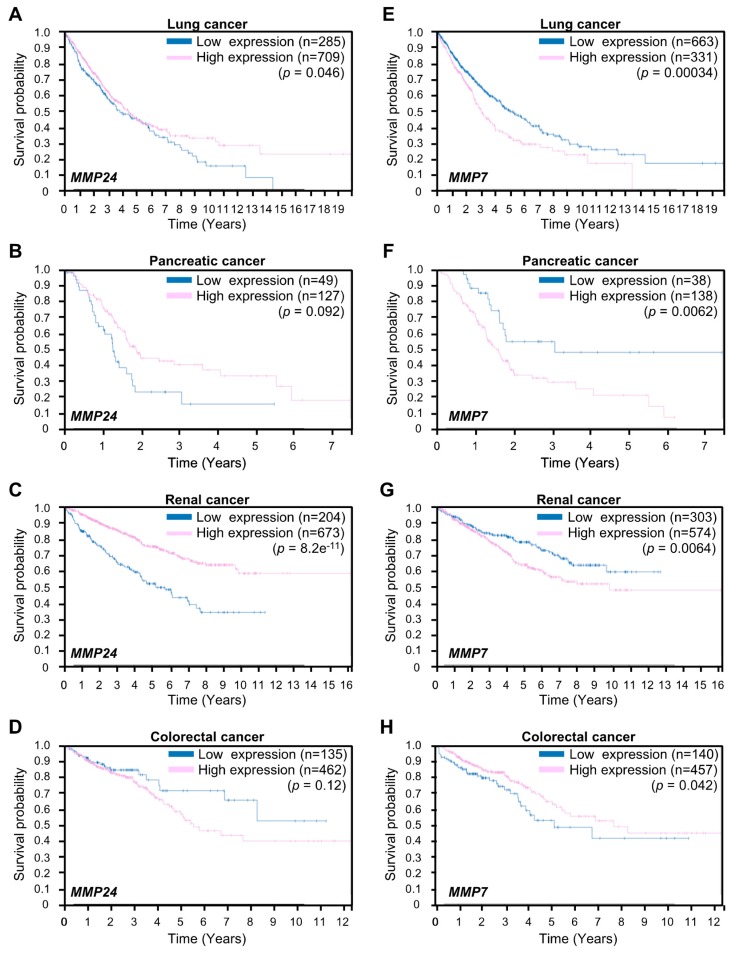

We proceeded to examine whether expression of MMP24 affects tumor aggressiveness. To this end, we investigated the correlation between MMP24 expression and the survival rate in breast cancer patients using the Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org). The result showed that breast cancer patients with lower levels of MMP24 expression exhibit worse survival rates overall (Figure 4). Further investigations revealed that also in other cancers including lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and renal cancer, patients with lower levels of MMP24 expression exhibit lower overall survival rates (Figure 5A–C). In contrast, although not statistically significant (p = 0.12; Figure 5D), there was a tendency that colorectal cancer patients with higher levels of MMP24 expression exhibit lower survival rates. While the elastic modulus of tumor ECM is correlated with the aggressiveness of cancer cells [1,2,20,21], these results imply that in cancers such as breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and renal cancer, MMP24 may retard tumor progression under the stiff environment of the cancer niche.

Figure 4.

Low expression of MMP24 predicts poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Kaplan–Meier plots for the survival analysis of human breast cancer patients with high (magenta) and low (blue) MMP24 expression obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (version 19) available at www.proteinatlas.org. The link is: (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000125966-MMP24/pathology/breast+cancer#imid_20796312).

Figure 5.

Expression of MMP24 and MMP7 in the prognosis of lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cancer, and colorectal cancers. Kaplan–Meier plots for survival analysis of human lung (A,E), pancreatic (B,F), renal (C,G), and colorectal (D,H) cancer patients with high (magenta) and low (blue) MMP24 (A–D) or MMP7 (E–H) expression obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (version 19) available at www.proteinatlas.org. The links are: lung; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000125966-MMP24/pathology/lung+cancer, https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000137673-MMP7/pathology/lung+cancer, pancreatic; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000125966-MMP24/pathology/pancreatic+cancer, https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000137673-MMP7/pathology/pancreatic+cancer renal; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000125966-MMP24/pathology/renal+cancer, https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000137673-MMP7/pathology/renal+cancer, colorectal; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000125966-MMP24/pathology/colorectal+cancer, https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000137673-MMP7/pathology/colorectal+cancer.

Expression of MMP7 encoding matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP7) is also increased in response to ECM stiffening [18]. MMP7 is known to promote cancer cell invasion [22,23]. We next examined the relationship between MMP24 and MMP7 expression with respect to tumor aggressiveness. In contrast to MMP24, higher levels of MMP7 expression were associated with lower survival rates in patients with lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, or renal cancer but not colorectal cancer (Figure 5E–H), whereas MMP7 was not a prognostic factor for breast cancer in the Human Protein Atlas database. Thus, MMP7 could have a role opposite to that of MMP24 in the regulation of aggressiveness of cancer cells.

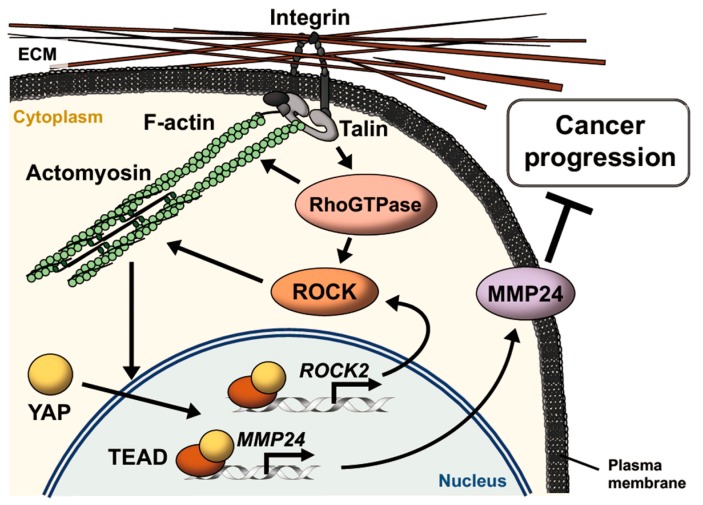

4. Discussion

Based on our results, we propose a model for hierarchical regulation of MMP24 expression (Figure 6). Rigid substrates increase actomyosin contractility via YAP-dependent expression of ROCK2, which further activates YAP and TEAD. Activation of YAP-TEAD then promotes the expression of MMP24, retarding the progression of various types of cancers such as breast cancer, lung cancer, and renal cancer.

Figure 6.

Schematic model for MMP24 expression promoted by extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffening. Integrins bind to ECM and induce the formation of focal adhesions, leading to actin polymerization via the activation of Rho GTPases such as Rho, Rac, and Cdc42. Rho GTPases also induce activation of myosin via activation of ROCK. Actomyosin contraction enhances activation of this integrin signaling pathway via conformational change of the proteins as mechanosensors including integrins and talin in an ECM stiffness-dependent manner. Increase in the number of actin filaments promotes YAP nuclear translocation, resulting in induction of ROCK2 and MMP24 expression via TEAD activation. MMP24 expression attenuates the progression of various types of cancers such as breast cancer, lung cancer, and renal cancer.

YAP expression promotes the malignancy of cancer cells [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Two well-known YAP-TEAD target genes CTGF and CCND1, which encode connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cyclin D1, respectively, contribute to the progression of cancer [32,33,34]. MMP24 expression that has been identified as a YAP-TEAD target gene in this study is believed to attenuate cancer progression, since high MMP24 expression reflects prolonged overall survival rate of patients with cancers such as breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and renal cancer (Figure 4 and Figure 5A–C). In these types of cancers, cancer aggressiveness would be promoted when expression of MMP24 induced by YAP-TEAD is hampered. Thus, MMP24 would be a prognostic factor in cancer patients and therefore, controlling MMP24 expression could be a viable treatment strategy to block cancer progression.

In this study, we also showed that in contrast to MMP24, high expression of MMP7, which is another YAP-TEAD target gene, is associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and renal cancer but not colorectal cancer (Figure 5E–H). It remains unclear why the role of MMP24 in tumor aggressiveness is opposite to that of MMP7 and their roles are cancer type-dependent. We also discovered that ECM substrates of MMP24 and MMP7 are different and that MMP7 expression promotes angiogenesis [35], which has a central role in tumor growth and metastasis [36], whereas the role of MMP24 in angiogenesis has not been clarified. The different roles of MMP24 and MMP7 in cancer progression could be due to the different ECM types surrounding the tumor [37], which control angiogenesis for metastasis and growth of cancer cells. Further studies are required for better understanding of the mechanism underlying cancer progression that involves the link between MMP24 and MMP7.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Nishina for the YAP 5SA expression vector and Takahito Nishikata for discussion, and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S., H.H., N.T., and K.K.; investigation, W.S., T.T., and Y.M.; data curation, K.I. and Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S. H.H., T.T., Y.B., N.T., and K.K.; writing—review and editing, W.S., H.H., N.T., and K.K.; supervision, N.T. and K.K.; project administration, N.T. and K.K.; funding acquisition, W.S., N.T., and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17H04054, JP18K06231, JP19J21096, and the HIRAO TARO Foundation of Konan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Paszek M.J., Zahir N., Johnson K.R., Lakins J.N., Rozenberg G.I., Gefen A., Reinhart-King C.A., Margulies S.S., Dembo M., Boettiger D., et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levental K.R., Yu H., Kass L., Lakins J.N., Egeblad M., Erler J.T., Fong S.F., Csiszar K., Giaccia A., Weninger W., et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitra S.K., Hanson D.A., Schlaepfer D.D. Focal adhesion kinase: In command and control of cell motility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huveneers S., Danen E.H. Adhesion signaling - crosstalk between integrins, Src and Rho. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1059–1069. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotnikov S.V., Pasapera A.M., Sabass B., Waterman C.M. Force fluctuations within focal adhesions mediate ECM-rigidity sensing to guide directed cell migration. Cell. 2012;151:1513–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebata T., Hirata H., Kawauchi K. Functions of the Tumor Suppressors p53 and Rb in Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:9231057. doi: 10.1155/2016/9231057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont S., Morsut L., Aragona M., Enzo E., Giulitti S., Cordenonsi M., Zanconato F., Le Digabel J., Forcato M., Bicciato S., et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low B.C., Pan C.Q., Shivashankar G.V., Bershadsky A., Sudol M., Sheetz M. YAP/TAZ as mechanosensors and mechanotransducers in regulating organ size and tumor growth. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2663–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebata T., Mitsui Y., Sugimoto W., Maeda M., Araki K., Machiyama H., Harada I., Sawada Y., Fujita H., Hirata H., et al. Substrate Stiffness Influences Doxorubicin-Induced p53 Activation via ROCK2 Expression. BioMed Res. Int. 2017;2017:5158961. doi: 10.1155/2017/5158961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimoto W., Itoh K., Mitsui Y., Ebata T., Fujita H., Hirata H., Kawauchi K. Substrate rigidity-dependent positive feedback regulation between YAP and ROCK2. Cell Adh. Migr. 2018;12:101–108. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2017.1338233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagase H., Visse R., Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sounni N.E., Noel A. Membrane type-matrix metalloproteinases and tumor progression. Biochimie. 2005;87:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porlan E., Marti-Prado B., Morante-Redolat J.M., Consiglio A., Delgado A.C., Kypta R., Lopez-Otin C., Kirstein M., Farinas I. MT5-MMP regulates adult neural stem cell functional quiescence through the cleavage of N-cadherin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:629–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh Y. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases: Their functions and regulations. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:207–223. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yip A.K., Iwasaki K., Ursekar C., Machiyama H., Saxena M., Chen H., Harada I., Chiam K.H., Sawada Y. Cellular response to substrate rigidity is governed by either stress or strain. Biophys. J. 2013;104:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo A.K., Hou Y.Y., Hirata H., Yamauchi S., Yip A.K., Chiam K.H., Tanaka N., Sawada Y., Kawauchi K. Loss of p53 enhances NF-kappaB-dependent lamellipodia formation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014;229:696–704. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhlen M., Zhang C., Lee S., Sjostedt E., Fagerberg L., Bidkhori G., Benfeitas R., Arif M., Liu Z., Edfors F., et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. 2017;357 doi: 10.1126/science.aan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nukuda A., Sasaki C., Ishihara S., Mizutani T., Nakamura K., Ayabe T., Kawabata K., Haga H. Stiff substrates increase YAP-signaling-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-7 expression. Oncogenesis. 2015;4:e165. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuberi K., Franz M., Rodriguez H., Montojo J., Lopes C.T., Bader G.D., Morris Q. GeneMANIA prediction server 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W115–W122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez J.I., Kang I., You W.K., McDonald D.M., Weaver V.M. In situ force mapping of mammary gland transformation. Integr. Biol. 2011;3:910–921. doi: 10.1039/c1ib00043h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gkretsi V., Stylianopoulos T. Cell Adhesion and Matrix Stiffness: Coordinating Cancer Cell Invasion and Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:145. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basu S., Thorat R., Dalal S.N. MMP7 is required to mediate cell invasion and tumor formation upon Plakophilin3 loss. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang M.C., Chen C.A., Chen P.J., Chiang Y.C., Chen Y.L., Mao T.L., Lin H.W., Chiang W.-H.L., Cheng W.F. Mesothelin enhances invasion of ovarian cancer by inducing MMP-7 through MAPK/ERK and JNK pathways. Biochem. J. 2012;442:293–302. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen J., Cao B., Wang Y., Ma C., Zeng Z., Liu L., Li X., Tao D., Gong J., Xie D. Hippo component YAP promotes focal adhesion and tumour aggressiveness via transcriptionally activating THBS1/FAK signalling in breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:175. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0850-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamar J.M., Stern P., Liu H., Schindler J.W., Jiang Z.G., Hynes R.O. The Hippo pathway target, YAP, promotes metastasis through its TEAD-interaction domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2441–E2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212021109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Sardo F., Strano S., Blandino G. YAP and TAZ in Lung Cancer: Oncogenic Role and Clinical Targeting. Cancers. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/cancers10050137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su L.L., Ma W.X., Yuan J.F., Shao Y., Xiao W., Jiang S.J. Expression of Yes-associated protein in non-small cell lung cancer and its relationship with clinical pathological factors. Chin. Med. J. 2012;125:4003–4008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang S., Zhang L., Purohit V., Shukla S.K., Chen X., Yu F., Fu K., Chen Y., Solheim J., Singh P.K., et al. Active YAP promotes pancreatic cancer cell motility, invasion and tumorigenesis in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through LPAR3. Oncotarget. 2015;6:36019–36031. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schutte U., Bisht S., Heukamp L.C., Kebschull M., Florin A., Haarmann J., Hoffmann P., Bendas G., Buettner R., Brossart P., et al. Hippo signaling mediates proliferation, invasiveness, and metastatic potential of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2014;7:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L., Shi S., Guo Z., Zhang X., Han S., Yang A., Wen W., Zhu Q. Overexpression of YAP and TAZ is an independent predictor of prognosis in colorectal cancer and related to the proliferation and metastasis of colon cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Zhao A.Y., Dai Y.J., Lian J.F., Huang Y., Lin J.G., Dai Y.B., Xu T.W. YAP regulates ALDH1A1 expression and stem cell property of bladder cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:6657–6663. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S170858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu X., Zhong J., Zhao Z., Sheng J., Wang J., Liu J., Cui K., Chang J., Zhao H., Wong S. Epithelial derived CTGF promotes breast tumor progression via inducing EMT and collagen I fibers deposition. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25320–25338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musgrove E.A., Caldon C.E., Barraclough J., Stone A., Sutherland R.L. Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:558–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu C.Y., Chang C.C., Prakash E., Kuo M.L. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cancer progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008;15:675–685. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huo N., Ichikawa Y., Kamiyama M., Ishikawa T., Hamaguchi Y., Hasegawa S., Nagashima Y., Miyazaki K., Shimada H. MMP-7 (matrilysin) accelerated growth of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2002;177:95–100. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuda A., Wang S.C., Morris J.P., Folias A.E., Liou A., Kim G.E., Akira S., Boucher K.M., Firpo M.A., Mulvihill S.J., et al. Stat3 and MMP7 contribute to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pickup M.W., Mouw J.K., Weaver V.M. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1243–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]