Abstract

Objective: To assess the private hospital development in China during 2005-2016 from a global perspective.

Methods: We searched the English and Chinese literature in PubMed, CNKI and Google Scholar databases with the keywords including “private hospitals in China”, “hospital ownership”, “public and private hospital”, “private hospital development”. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to assess the trend of the private hospital development in China and worldwide. Both the change of private hospitals in supply capacity and health care delivery were studied in this paper. The number of hospitals, number of hospital beds and the average number of hospital beds per hospital were employed to measure the supply capacity. The visit number, inpatients number, and bed occupancy rate (BOR) were used to measure the healthcare delivery. The data was collected from the China Health Statistical Yearbook and the “Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development (OECD) Statistics” website.

Results: The private sector rapidly expanded in China’s hospital market in recent years. The number of private hospitals exceeded the public in 2015. There has also been a significant rise for the indicators of both the supply capacity (including number of hospitals, number of hospital beds and the average number of hospital beds per hospital) and the health care delivery (inpatients number and BOR) of the private hospitals. However, the growth rates of them were relatively lower than the public. The expansion trend of China’s private sector in the hospital market accorded with most the OECD countries around the world. In 2016, China was above the medium level of the share of the private hospitals’ number with the OECD countries, but below the medium for the supply capacity, in terms of the hospital beds.

Conclusion: As a result of the economic growth and supporting policy, the private sector has experienced a vast expansion in China’s hospital market in the past decade. The rising gap in average size between private and publicly owned hospitals, and the inconsistent development between the private hospitals’ supply capacity and their market share, have become the two main challenges. Meanwhile, the future policy in supporting the private sector should be carefully introduced to advance the whole healthcare delivery system development in China.

Keywords: private hospital, publicly owned hospital, health reform, China

Introduction

“The difficulty and costliness for healthcare services” became a serious social problem from the end of the 1990s to present in China.

To solve it, the new round of national health reform was launched in 2009. One of the five main policies is to encourage the private hospital development [1], aiming at improving the total healthcare supply capacity, as well as generating pressure on public hospitals for higher quality of affordable care.

The publicly owned hospital has long been taken the dominant position in China 2., 3.. According to the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (previously the Ministry of Health), the public hospitals took around 90% of the total hospital beds in 2009.

There would be several advantages in encouraging the private hospitals development: Firstly, the new private hospitals would increase the total provision of healthcare services [4]. Secondly, the development of private hospitals would result into competition, thus stimulate the publicly owned hospitals’ internal impetus to improve the quality of care delivered and decrease the patients’ cost 5., 6.. Thirdly, the new private hospitals would boost the healthcare market vitality, and more patient-oriented healthcare services would be provided to meet the diversified needs 7., 8..

Followed by the reform, a series of specific policies were implemented to encourage the private investment in the healthcare sector, such as clearing the obstacles in new hospital’s permission and being contracted with the basic health insurance programs, as well as introducing the tax exemption policy for the new for-profit private hospitals in the first three years 9., 10., 11., 12.. With these supportive policies, the private hospitals rapidly increase in China and play a more important role in the hospital care delivery nowadays.

This study aims to assess the private hospital development in China from a global perspective and provide reference for the development of the private hospitals in China.

Methods

We searched the English and Chinese literature in PubMed, CNKI and Google scholar databases with the keywords including “private hospitals in China”, “hospital ownership”, “public and private hospital”, “private hospital development”.

The data was collected from China Health Statistics Yearbook 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24. from 2005–2016 and the website of “the Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development (OECD) Statistics” (http://stats.oecd.org) [25]. The descriptive statistical analysis was used to access the development of the private hospital in China and OECD countries. Without employing any statistical inference method to explore the causes and consequences of the time trend, the statements in the discussion part are implication of the descriptive results. In future research, more comprehensive data and analysis can provide a stronger evidence to understand the topic.

According to the China Health Statistics Yearbook, the hospitals in China could be divided into public hospitals and private hospitals by ownership. The public hospitals are defined in this study as the hospitals whose registered business type is state-owned or collective-owned, while the others are private.

The data of private/public hospital number and hospital beds in OECD countries was obtained from the website of “OECD Statistics” (http://stats.oecd.org), in the parts of “Health-Health Care Resources-Hospitals” and “Health-Health Care Resources-Hospital beds”. The website of “OECD Statistics” is available for the public. Excluding the countries with no or not enough data of required indicators (for example, there are 33 countries in terms of the hospital number, however, only 24 countries are available.) during the research period, total 22 OECD countries are analyzed in this paper. Specifically, the data of Poland and Hungary after 2011 is not available from this website, therefore the data in 2011 was used in this paper [25].

We assess the development of private hospitals in China by examining both of the change in supply capacity and health care delivery. The number of hospitals, number of hospital beds and the average number of hospital beds per hospital were employed to measure the supply capacity. The visit number, inpatients number and bed occupancy rate (BOR) were used to measure the healthcare delivery. The number of outpatients in hospitals by ownership is not available in the dataset of China Health Statistics Yearbook, so we used the visit number and inpatient number instead of the outpatient number 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.. The share of private/public hospitals’ number (in all hospitals) was calculated by dividing the number of private/public hospitals by overall number of all types of hospital in China. The share of private/public hospital beds (in all hospitals) was calculated by dividing the number of private/public hospital beds by overall number of hospital beds in all types of hospitals. The average number of hospital beds per hospital was calculated by dividing the overall number of private or publicly owned hospital beds by overall number of private or publicly owned hospital numbers 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.. The visit number includes outpatients, emergency patients, patients for health checkup and health counseling. The bed occupancy rate was calculated by the following formula:

The development of private hospitals in OECD countries were also studied in this paper in contrast with China. The OECD has included major developed countries in the world. Their experience developing private hospitals can provide reference for China.

Results

Supply capacity of private hospitals

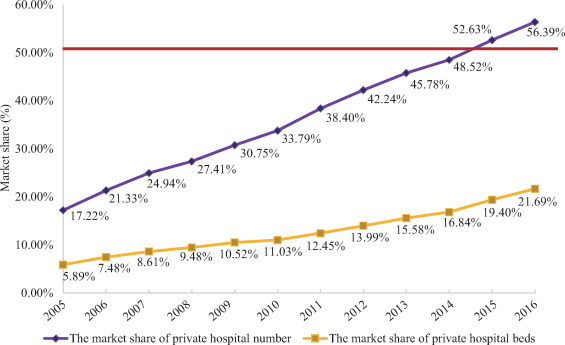

Figure 1 showed the rapid expansion of private hospitals in China during 2005–2016. The percentage of private hospitals in all hospitals increased from 17.22% in 2005 to 56.39% in 2016, while the private hospital beds increased from 5.89% to 21.68%. Even though the private hospital number exceeded the public hospitals in 2015 (52.63%), the share of private hospital beds is still around 20% in 2016. The growth of the share of private hospital number was higher than the private hospital beds.

Figure 1.

The share of private hospital number and hospital beds in China, 2005–2016 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.

Note: The red line is the median line (50%)

Table 1 showed the time trend in hospital size on average by private and public hospitals. Both of the private and public hospitals increased in size by year. The average number of hospital beds of the private and public hospitals increased from 45 and 149 beds per hospital in 2005 to 75 and 351 in 2016, respectively. However, the disparity in size between private and public hospitals was increasing. The average publicly owned hospital bed number was around 3.32 times of private in 2005, while 4.67 times in 2016. Combining the results in Figure 1 and Table 1, the size of most new private hospitals was relatively smaller than the public ones during this period.

Table 1.

Differences in the average number of hospital beds per hospital between the private and public hospitals in China, 2005–2016 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.

| Average number of hospital beds | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private hospitals (beds per hospital) | 44.75 | 46.66 | 46. 52 | 50.57 | 52.6 | 52.87 | 54.68 | 59.49 | 63.04 | 66.59 | 71.23 | 75.08 |

| public hospitals (beds per hospital) | 148.61 | 156.45 | 164.07 | 182.38 | 198.74 | 217.6 | 239.58 | 267.43 | 288.55 | 309.88 | 328.75 | 350.59 |

| Ratio of private/public | 1/3.32 | 1/3.35 | 1/3.53 | 1/3.61 | 1/3.78 | 1/4.12 | 1/4.38 | 1/4.50 | 1/4.58 | 1/4.65 | 1/4.62 | 1/4.67 |

Healthcare delivered by private hospitals

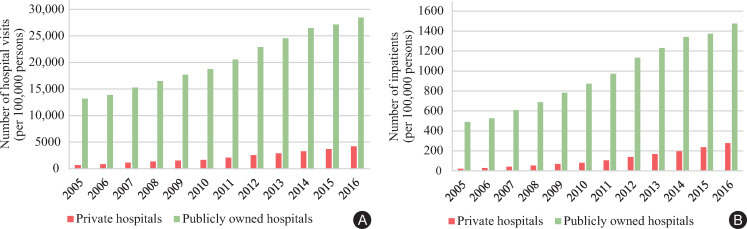

Figure 2 showed the hospital visits and inpatients number by ownership in China during 2005–2016. The hospital visits and inpatients by both of private and public hospitals were increasing. Both of the increasing rates of hospital visits and inpatients of private hospitals exceeded the public.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the number of hospital visits (A) and inpatients (B) between types of hospital ownership in China, 2005–2016 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.

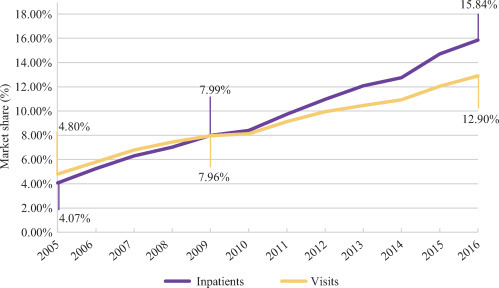

Figure 3 showed the change in share of private hospital visits and inpatients in the whole hospital market in China during 2005–2016. Both shares kept increasing, from 4.80% and 4.07% for visits and inpatients in 2005, to 12.90% and 15.84% in 2016, respectively. In 2009, the share of inpatients in private hospitals exceeded the share of their visits, since then, the gap between them was increasing.

Figure 3.

Share of visits and inpatients in private hospitals in China, 2005–2016 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.

It should be noticed that, from the aspect of inpatients, the growth of the delivery (represented by the share of inpatients) caught up with the growth of private hospital’s supply capacity (represented by the share of private hospital beds). During 2005–2016, the share ratio of private hospital’ inpatients and beds maintained around 70%. However, from the aspect of visits, the delivery (represented by the share of visits) lagged behind the growth of private hospital’s supply capacity. The share ratio of private hospital’s visits and beds decreased from around 80% (4.80%/5.89%) in 2005, to 60% (12.9%/21.69%) in 2016.

Figure 4 further compared the BOR of hospital beds between private and public hospitals in China during 2005-2016. The BOR of both private and public hospitals increased from 49.80% and 71.50% in 2005, to 62.80% and 91.00% in 2016, respectively. From Figure 4, we could find that the BOR of private hospitals reached the highest in 2013 (63.40%), and then slightly decreased in the following years. And the publicly owned hospital had the similar trend and reached the highest in 2012 (94.20%), then went back down a bit. Although the bed occupancy rate of private hospitals was increasing in general, it was still much lower than public hospitals. In 2016, the bed occupancy rate of private hospitals was a third less than the public.

Figure 4.

The comparison of the bed occupancy rate between types of hospitals in China, 2005–2016 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24.

Combining with the result of the share of private hospital number and private hospital beds in Figure 1, while the share of private hospital number in China was 56.39% and the share of hospital beds in private hospitals was 21.69% in 2016 (Figure 1), the total visits in private hospitals was only 12.90% (Figure 3). This result confirmed the low BOR of private hospitals in China (62.80%).

Comparison with OECD countries

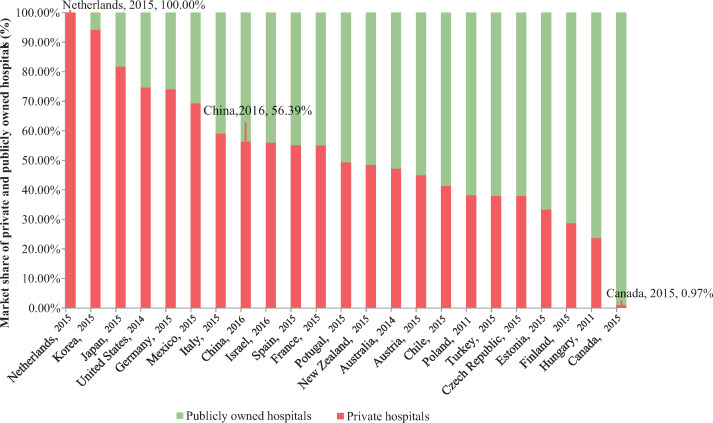

Besides China, the private sector is now playing an essential role in hospital market in most countries around the world. Figure 5 showed the share of private and publicly owned hospital number (in all the hospitals) in China and 22 OECD countries. The data of Poland and Hungary after 2011 is not available, therefore the data in 2011 was used in this paper. The share of private hospital number differs among countries. All the hospitals in Netherlands were private, while in Canada were almost public (private hospitals took only 0.97% in 2015). Referring to the data in China (private hospitals took 56.39% in 2016, Figure 1), compared with OECD countries, the share of private hospital number in China was above the median level (Portugal, 49.33%).

Figure 5.

The market share of private and publicly owned hospital number in China and 22 OECD countries [25]

Note: Data of Poland and Hungary after 2011 is not available, therefore the data in 2011 was used; OECD: Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development

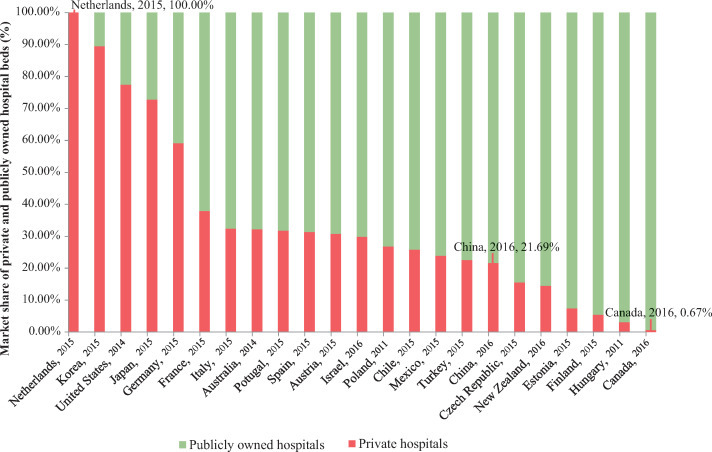

Figure 6 presented the share of private and publicly owned hospital beds in total for China and 22 OECD countries. The situation was similar with Figure 5. Netherlands and Canada were the two extremes (the share of private hospital beds took 100% in Netherlands and 0.67% in Canada). Comparing with OECD countries, China (21.69%, Figure 1) was around 30% below the median level (Israel, 29.87%) of OECD countries in term of the share of private hospital beds.

Figure 6.

The market share of private and publicly owned hospital beds in China and 22 OECD countries [25]

Note: the data of Poland and Hungary after 2011 is not available, therefore the data in 2011 was used; OECD: Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development

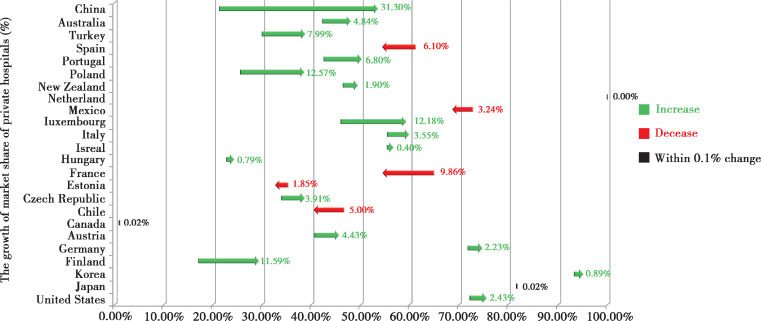

The private hospitals development of OECD countries in the past 12 years were further studied to compared with China. Figure 7 showed the time trend of the private hospital’s number in China and 22 OECD countries during 2006–2015.

Figure 7.

The trend of private hospitals’ share in China and OECD countries, 2006–2015 [25]

OECD: Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development

Like China, most of the OECD countries (16 of 22) had an increase in the share of private hospital number during 2006–2015. From 2005 to 2016, Poland (12.57%) and Finland (11.59%) experienced the top two growths, while France declined the most (9.86%). The growth of private hospitals number share in China (31.30%) exceeded all the OECD countries.

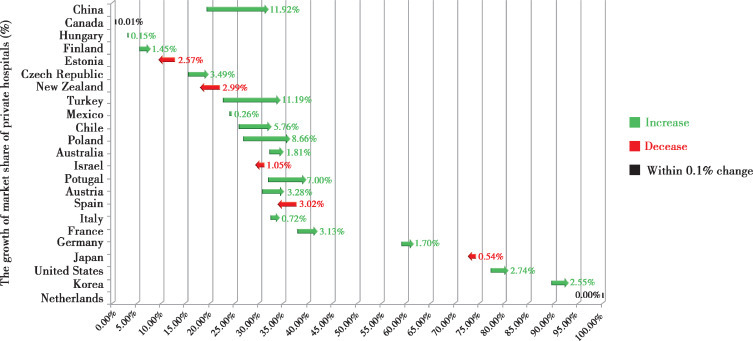

Figure 8 showed the time trend of private hospital beds shares in China and 22 OECD countries during 2006–2015. The share of private hospital beds was increasing in 15 OECD countries, out of 22. From 2005 to 2016, Turkey (11.19%) and Poland (8.66%) ranked the first two counties. 5 OECD countries declined in the same period, the maximum decrease happened in Spain (3.02%). China’s increasement in the share of private hospital beds (11.92%) exceeded all the OECD countries.

Figure 8.

The trend of private hospital beds’ share in China and OECD countries, 2006–2015 [25]

OECD: Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development

Combining the results from Figure 7 and Figure 8, there are two main findings. First, most OECD countries experienced a growth of private sector in hospital market as China. Although individual countries, like Chile, had a decline in hospital number, but a growth in hospital beds, showed the expanding size of private hospitals. Second, the new private hospitals’ size would be smaller than the public, which was similar with China. Taking Finland as an example, the number of private hospitals’ number increased 11.59% (Figure 7) during the past decade, but the hospital beds in private hospitals increased only 1.45% (Figure 8).

Discussions

Economic development and supporting policy would be two main drivers of the private hospital’s expansion in China

The private sector has experienced a vast expansion in China’s hospital market in the past decades for both healthcare supply capacity and delivered care. The shares of private hospitals’ number, beds, visits, and inpatients in 2016 were 3.27, 3.68, 2.69, and 3.89 times as in 2005, respectively (Table 1). Since 2015, the private hospital number even exceeded the publicly owned hospitals (Figure 1). The economic development and supporting policy would be the two main factors driving the expansion of private hospitals in China.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, since the great economic reform in 1978, the gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita disposable income in China increased from 368 billion CNY and 385 CNY in 1978, to 82,712 billion CNY and 25,974 CNY in 2017, respectively [26]. The economic development has greatly improved consumption capacity and boosted the demand for health care [27], in both the level of individuals and society. Consequently, it promotes the development of the whole hospital market, including both private and public hospitals.

At the individual level, along with the income improvement, people have increasing expectation for health care quality and life quality. As a result, the demand of healthcare is increasing tremendously. In addition, Chinese government also made great efforts to adjust to economic development and growing demands, which put significant pressure on its health care system to become more accessible, affordable, and efficient. Firstly, the government developed and further improved a system of universal medical insurance with three major insurance programs: Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (Urban Employee Insurance) covering individuals employed in the formal sector in cities; Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (Urban Resident Insurance) for urban residents, defined by household registration status, who are unemployed or who work in the informal sector; and the New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance (Rural Resident Insurance) for rural residents. In 2002, less than 10% of rural populations and even fewer urban residents had insurance coverage. Currently, more than 95% of citizens are covered by basic medical insurance [27]. Secondly, after the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (SARS) in 2003, the Chinese government has put more budget outlay into health care and changed the financing model from supply-side to demand-side, where government financial support went directly to the demand side (patients) through medical insurance or subsidies rather than public providers (hospitals). Under such circumstances, the average per capita financing level of the basic medical insurance has been elevated. Both the increasing coverage rate and average per capita financing level of basic medical insurance can lessen individual’s medical burden significantly, and then lead to more demand of health care [28].

Besides the economic development, the supporting policy would be also an important factor of the rapid private hospitals’ expansion.

Government has pursued a new round of health reforms since the late 2000s. During this period, many policies were implemented to promote the development of private sector, as a supplement of publicly owned hospitals. In 2009, the central government launched the new round of national health reform. In the reform, it was clearly pointed out to “encourage and guide social sector to develop medical and health undertakings” [1]. Further, in December 3, 2010, five ministries jointly issued the Optnions on further encourage and guide social sector to hold medical institutions [9]. Since then, series of policies have been implemented to encourage the development of private hospitals in aspects of entry restriction, future planning, evaluation of the basic health insurance programs’ appointed hospitals, and tax exemption. For example, to solve the problem of entry restriction, it is clearly pointed out that all the fields where laws permit should be open to the social sector and all the fields open to local capital must be open to foreign capital [11]. As for the future planning, if social sectors can meet the standard of entry, they would have the priority to be chosen when configuring, adjusting and allocating medical and health resources [29].

In general, the economic development would have promoted the development of the whole hospital market, including both private and public hospitals, and the policy that encourage the development of private hospitals would further lead to the expansion of private hospitals.

The private hospital in China may keep increasing according to worldwide experience

As Figure 7 and Figure 8 showed, though the development of private hospitals in each country varies a lot, the trend is in accordance with China: the private hospital in most countries is increasing, as it is in China. In this case, it can be inferred that the private hospitals may continue expanding from a global perspective.

Firstly, the experience of the worldwide shows that the expenditure on health will increase along with the economic development. According to the World Bank, the share of health expenditure of gross domestic product in China was 6.0% in 2015 while the average level in the worldwide was 9.9%. The data in the United States was 16.9% in 2015 and it was much higher than that in China [30]. Therefore, along with the rapid economic development, the share of health expenditure of gross domestic product in China will continue increasing.

In addition, under the situation of New Normal (“New Normal” was proposed by President Xi Jinping and included three aspects: (1) In the aspect of the speed of the economy development, China’s economy has shifted gear from the previous high speed to a medium-to-high speed growth; (2) In the aspect of the economic structure, China’s economy was constantly improved and upgraded; (3) In the aspect of the motivation, Chinese economy was increasingly driven by innovation instead of input and investment), the return on investment of health industry will continue increasing while that of many other industries is decreasing. In this case, the social sector will pay more attention and invest more to take part in the health industry.

Along with the increasing investment from both government and social capital, the development of the whole hospital market, especially the private hospitals will be further promoted.

Rising disparity in size between private and public hospitals

Along with the rapid development of the private hospital in China, several important problems exist.

One of the problems is that the disparity in size between different ownerships is increasing. As Table 1 showed, though both average size of private and public hospitals did expand, the expanding speed of private hospitals was lower and the disparity in size between private and public hospitals was increasing.

In the beginning, the disparity in size between different ownerships may result from insufficient start-up capital of the private sectors. As Figure 1 showed, in 2016, even though the number of private hospitals exceeded the publicly owned hospitals in 2015 (52.63%), the share of private hospital beds was only around one fifth. It can be inferred that the new private hospitals would be almost in small size. Besides, most of them are assessed to be primary hospitals. Compared with the high-grade hospitals, which are always the publicly owned hospitals, private hospitals cannot receive patients with serious disease. The policies aiming to control the cost inflation, for example, the promotion of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs), also limit the development of private hospitals. DRGs are one of the most striking prospective payment systems around the world in recent years [31]. It groups patients into several DRG categories according to principal diagnosis, type of treatment, age, surgery, and discharge status. Under such circumstances, hospitals are paid a set fee for treating patients in a single DRG category, regardless of the actual cost of care accrued for the individual, as to create incentives for hospitals to control cost and to increase number of inpatient admissions.

However, the rising disparity in size between private and public hospitals further means that the development speed of the private hospital cannot catch up development speed of the publicly owned hospitals. In other words, the private hospital is less competitive than the publicly owned hospitals. The low-competitive condition of private hospitals can also lead to the inconsistence between the status of healthcare delivery and supply capacity of private hospitals, which we will discuss it later.

Inconsistence between the status of healthcare delivery and supply capacity of private hospitals

Another problem existing in the development of private hospitals is that the healthcare delivery status of private hospitals is inconsistent with their supply capacity. As the Figure 1, Figure 3 and Figure 4 showed, in 2016, while the share of private hospitals’ number and hospital beds in China was 56.39% and 21.68% respectively, the total visits in private hospitals were only 12.90% and the bed occupancy rate in private hospitals in China decreased to 62.80% (the highest was 63.20% in 2012). It suggests that the increasing of the supply capacity has little effect in making private hospitals more competitive.

The reason of the inconsistence is the same with that of the rising disparity in size between private and public hospitals: the private hospital is less competitive than the publicly owned hospitals.

Patients prefer public hospitals for their reputation of low charge and good quality However, it still lacks sufficient evidence to prove that there are some difference between private hospitals and public hospitals in the aspect of healthcare quality and expenditure [32]. Some scholars believe private hospitals even perform better in the aspect of quality 33., 34. and charge 34., 35.. Under such circumstances, the private hospital cannot compete with the publicly owned hospital “fairly”. This phenomenon may closely relate to the reputation problem, small-size and low-level limitation, policies and poor supervision.

First of all, the private hospital lacks the accumulation of reputation. As a product of the market economy, private hospitals should control costs to take part in the competition of the market. People may feel that the private hospitals are more concerned about the economic benefits but not the benefits of patients 7., 36., 37.. Tendentious reports produced by media outlets can also deepen the misunderstanding [38]. As the result, the reputation of private hospitals was damaged [39], and contributed to the misunderstanding that private hospitals behave less social responsibility than public hospitals [40].

Secondly, private hospitals are always in small size and assessed to be primary hospitals. Meanwhile, with the increasing household income, people have increasing expectation for health care quality, which the primary hospitals cannot provide. Thus, the private hospital is less attractive for them. The low competitiveness affects the size expansion of private hospitals. On the other side, the small size can also lead to the low competitiveness. It becomes a vicious circulation.

Thirdly, the policy is also one of the main reasons [41], especially in the aspect of medical personnel. The medical personnel are the core competence. However, facility construction is easy but the recruitment of excellent doctors is difficult. Because of the inequality in professional evaluation policy [42], medical personnel in private hospitals are badly insufficient and has low stability 43., 44..

Finally, the poor supervision in private hospitals can also lead to low competitiveness. The strict supervision is always thought to be a limitation to the private hospital’s development. However, a strict but necessary supervision is important for their sustainable development, for example, the supervision on the classification of non-profit and for-profit hospitals. In most developed countries, they have a clear definition of “non-profit” and “for-profit”. In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) defined the private hospital as “An organization must be organized and operated exclusively for exempt purposes set forth in section 501(c)(3), including charitable, religious, educational, scientific, literary, testing for public safety, fostering national or international amateur sports competition, and preventing cruelty to children or animals” [45]. In China, the definition of non-profit hospital is unclear. Meanwhile, social sectors are suggested to be non-profit 46., 47. while whether non-profit hospitals perform better in quality [48], charge [49] and efficiency [50] is still a controversial question abroad. Considering the reputation, tax policy, a lot of private hospitals that should be defined as for-profit hospitals are defined as the non-profit hospitals mistakenly [51]. Thus, they can be tax-exempt and then transfer profits through varies channels [52]. They leave the bad impression in people’s mind and then go from bad to worse finally. In this case, efforts on stricter supervision should be made to prevent such things and improve the competitiveness of private hospitals.

The factors above all lead to the low competitiveness of private hospitals and then limit the development of private hospitals. On the other side, the relatively worse development also further lead to the factors before such as small size and low stability of medical personnel. Finally, it becomes a vicious circle.

Preferential policy for private hospitals should be carefully introduced

It can be seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8 that the private hospital in China experienced the largest increase among the 23 countries. Preferential policy for private hospitals is one of the main reasons why the private hospital expands rapidly. It can be inferred that the private hospital would keep expanding if the Chinese government give preferential treatment to the private hospital continually.

However, Chinese government should give more careful consideration to the further development of private hospitals: would it better for the whole hospital market to give preferential treatment to the private hospital continually and keep it expands at a high speed?

In some countries, where the publicly owned hospital takes the dominant position in the health system, people also have long life expectancy. For example, according to the World Bank, the life expectancy of China was 76 years while that of Canada, Finland and Estonia (where the public hospitals took 99.03%, 71.27%, and 66.67%, respectively) was 82, 82 and 77 years in 2016, respectively [53]. In addition, according to the Figure 5 and Figure 6, the interquartile range of market share of private hospital number and hospital beds was 38.09%–64.16% and 18.61%–35.16%, which suggests that the market share of private hospitals in the majority of countries were within the range. China is within the range. It suggests that the share of the private hospital is proper now. Finally, the expected effect in promoting the development of private hospitals has been almost achieved. The total supply capacity increased and it was reported that the pro-competition policy, which encourage the private hospitals to take part into the competition, is an effective solution for China’s publicly owned hospital reform [5].

All the facts above suggest that the private hospital in China has developed to a proper level from a global perspective.

More participants of social sectors and private hospitals makes the hospital market more competitive. However, it was reported that the high degree of competition may lead to the cut-throat competition. For example, the medical arms race 54., 55., which refers to the case where hospitals compete in purchasing expensive medical equipment in an effort to attract patients. The medical arms race always leads to higher medical expenses and lower hospital efficiency [5]. Therefore, preferential policy for private hospitals should be carefully introduced to advance the whole healthcare delivery system development in China. It should be the market rather than the government to decide the expansion of private hospitals and the speed of their expansion.

Conclusion

To summarize, there are both opportunities and challenges for the private hospital in China. The private hospitals in China is booming because of the economic development and supporting policies while the rising gap in average size between private and public hospitals, and the inconsistent development between the private hospitals’ supply capacity and their market share, have become the two main challenges. Meanwhile, the future policy in supporting the private sector would be carefully introduced to advance the whole healthcare delivery system development in China.

In the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, President Xi Jinping, emphasized the importance of New Health Reform [56]. There is no reason to doubt that the government can regulate the development of private hospitals better in the future and then the private hospitals can work better in solving the problems of “the difficulty and costliness for healthcare services”.

Additional files

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Qingling Jiang for her valuable suggestions. The authors are responsible for all remaining errors.

Funding

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71303165), Sichuan University (Grant No. 2015SCU04A19 and 2018SCUH0027), and China Medical Board (Grant No. 17-276) for their financial support.

References

- 1.Li KQ. Deepening the reform of health care. [updated 2012-03-31; cited 2018-03-14]. http://english.qstheory.cn/magazine/201201/201203/t20120331_149059.htm.

- 2.Jin JJ, Dong LJ, Qian WJ. Development of China’s private healthcare providers under the governments’ encouragement and guiding policies. Chin J Health Policy. 2017;10(9):68–74. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang GL, Ye TY. Analysis of the development of private hospital under the background of new medical reform in China. Chin Hos Manag. 2016;36(11):24–27. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan J, Zhao HQ, Wang XL. Assessing spatial access to public and private hospitals in Sichuan, China: the influence of the private sector on the healthcare geography in China. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan J, Qin X, Hsieh CR. Is the pro-competition policy an effective solution for China’s public hospital reform? Health Econ Policy Law. 2016;11(4):337–357. doi: 10.1017/S1744133116000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan J, Qin X, Li Q. Does hospital competition improve health care delivery in China? China Econ Rev. 2015;33:179–199. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu G, Guan HJ, Gao C. Analysis on status quo of private care in China. Chin J Health Policy. 2013;6(09):41–46. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JM. Understanding and thinking about the development of private hospitals in China. Chin Hos Manag. 2012;32(9):12–13. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on further encourage and guide social sector to establish medical institutions. [updated 2010-11-26; cited 2018-03-14]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2010-12/03/content_7260.htm. (in Chinese)

- 10.Xinhua News Agency. The plan for deepening the reform of medical and health system and its implementation during the 12th Five-Year Plan Period were issued. [updated 2012-03-22; cited 2018-03-18]. http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-03/22/content_2098014.htm. (in Chinese)

- 11.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on promoting the development of health service industry. [updated 2013-10-18; cited 2018-03-18]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2013-10/18/content_6067.htm. (in Chinese)

- 12.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Policy measures to accelerate development of nongovernmental hospitals. [updated 2015-06-11; cited 2018-03-17]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/15/content_9845.htm. (in Chinese)

- 13.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2005. 2005 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2006. 2006 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2007. 2007 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2008. 2008 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2009. 2009 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2010. 2010 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2011. 2011 China health statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2012 China health statistics yearbook. [cited 2018-06-25]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2012/index2012.html. (in Chinese)

- 21.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2013 China health statistics yearbook. [cited 2018-06-25]. http://www.moh.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2013/index2013.html. (in Chinese)

- 22.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2014. 2014 China health and family planning statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2015. 2015 China health and family planning statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Peking Union Medical College Press; Beijing: 2016. 2016 China health and family planning statistics yearbook. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistics and Data Directorate Department of Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Statistics by theme: health care resources: hospitals. [cited 2018-03-20]. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=HEALTH_STAT.

- 26.National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. 2017 Statistical bulletin of national economic and social development of China. [updated 2018-02-38; cited 2018-03-20]. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201802/t20180228_1585631.html. (in Chinese)

- 27.Liu GG, Vortherms SA, Hong X. China’s Health Reform Update. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):431–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan J, Lei XY, Liu GE. Does medical insurance promote health?- based on the empirical analysis of basic medical insurance for urban residents in China. Econ Res J. 2013;(4):130–142. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on improving regional health planning, medical institutions planning, and promoting the development of non-governmental medical institutions. [update 2012-07-11; cited 2018-03-19]. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-07/11/content_2180652.htm. (in Chinese)

- 30.The World Bank Group. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). [cited 2018-03-27]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS.

- 31.Street A, Kobel C, Renaud T. How well do diagnosis-related groups explain variations in costs or length of stay among patients and across hospitals? Methods for analysing routine patient data. Health Econ. 2012;21(S2):6–18. doi: 10.1002/hec.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen YC, Eggleston K, Lau J. Hospital ownership and financial performance: what explains the different findings in the empirical literature? Inquiry. 2007;44(1):41–68. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_44.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eggleston K, Shen YC, Lau J. Hospital ownership and quality of care: what explains the different results in the literature? Health Econ. 2008;17(12):1345–1362. doi: 10.1002/hec.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang W, Li Q, Zhu ZF. Research on the Development Status of Private Hospitals in China. Chin Health Econ. 2016;35(5):29–31. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SJ, Park EC, Kim TH. Mortality, length of stay, and inpatient charges for heart failure patients at public versus private hospitals in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56(3):853–861. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.China Youth Daily. A new reprot from research institutions of the state council said ‘China’s health reform was unsuccessful’. [updated 2005-07-29; cited 2018-03-19]. http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1026/3577724.html. (in Chinese)

- 37.Montagu D, Anglemyer A, Tiwari M, et al. A Comparison of Health Outcomes in Public vs. Private Settings in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. [updated 2011-07-09; cited 2018-03-19]. http://healthsystemshub.org/uploads/resource_file/attachment/243/A_Comparison_of_Health_Outcomes_in_Public_vs_Private_Settings_in_Low-_and_Middle-Income_Countries.pdf.

- 38.Qiu H, Yang Y. Research on the development of private medical institutions in Yunnan province. Chin Hos Manag. 2011;31(5):8–10. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong LD, Liu GE, Li L. Opportunities and challenges for private hospitals in the ongoing health reform. Chin J Hos Adm. 2013;29(9):641–645. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou CH. Disscussion of the developing status and strategies of private hospitals in China. Med Soc. 2010;23(11):62–64. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mei SZ, Huang HX. The development of non-profit private hospitals in China: Institutional obstacles and policy suggestions. Chin J Health Policy. 2014;7(5):33–36. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng ZH, Gao GY, Duan T. Surviving difficulty of human resources: case study on private hospitals in Beijing. Chin Hos. 2014;(1):20–23. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Y, Fang PQ. Research on the Medical Staff Stability of Private Hospitals in China. Chin Hos Manag. 2014;34(11):31–33. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang XW. Problems and policy analysis of the development of private hospitals in China. Jiangxi Soc Sci. 2009;29(5):24–30. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Internal Revenue Service. Exemption Requirements - 501(c)(3) Organizations. [updated 2017-12-28; cited 2018-03-20]. https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/exemption-requirements-section-501-c-3-organizations.

- 46.Xiang Q, Wang Q, Zou LA. Analysis of private hospital development trend and impact on public hospital in China. Chin Health Econ. 2013;32(5):14–15. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan SJ, Yan B, Zhu QZ. The trends and experiences on private hospital’s development in United State. Chin Health Resour. 2010;13(2):95–97. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, Lacchetti C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. CMAJ. 2002;166(11):1399–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devereaux PJ, Heels-Ansdell D, Lacchetti C. Payments for care at private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2004;170(12):1817–1824. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kralewski J, Gifford G, Porter J. Profit vs. public welfare goals in investor-wwned and not-for-profit hospitals. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1988;33(3):311–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang QS. Thoughts on the development direction of private hospitals. Health Econ Res. 2002;(3):12–13. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei X, Meng QY. Major policy issues and countermeasures of non-public hospitals in China. Chin J Health Policy. 2017;10(5):53–58. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 53.The World Bank Group. Life expectancy at birth, total (years). [cited 2018-03-27]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN.

- 54.James P. Is The Medical Arms Race Still Present In Today’s Managed Care Environment? [updated 2008-10-31; cited 2018-03-19]. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1292655.

- 55.Joskow PL. The effects of competition and regulation on hospital bed supply and the reservation quality of the hospital. [cited 2018-03-19]. https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/63548/effectsofcompeti00josk.pdf?sequence=1.

- 56.Xi JP. Report to the 19th national congress of the communist party of China: secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and strive for the great success of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era. [updated 2017-10-27; cited 2018-03-24]. http://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2017-10/27/content_5234876.htm. (in Chinese)