Abstract

Our focus is the evolution of business strategies and network structure decisions in the commercial passenger aviation industry. The paper reviews the growth of hub-and-spoke networks as the dominant business model following deregulation in the latter part of the 20th century, followed by the emergence of value-based airlines as a global phenomenon at the end of the century. The paper highlights the link between airline business strategies and network structures, and examines the resulting competition between divergent network structure business models. In this context we discuss issues of market structure stability and the role played by competition policy.

1. Introduction

Taking a snapshot of the North American commercial passenger aviation industry in the spring of 2003, the signals on firm survivability and industry equilibrium are mixed; some firms are under severe stress while others are succeeding in spite of the current environment.1 In the US, we find United Airlines in Chapter 11 and US Airways emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. We find American Airlines having just reported the largest financial loss in US airline history, while Delta and Northwest Airlines along with smaller carriers like Alaska, America West and several regional carriers are restructuring and employing cost reduction strategies. We also find Continental Airlines surviving after having been in and out of Chapter 11 in recent years, while Southwest Airlines continues to be profitable. In Canada, we find Air Canada in Companies Creditors Arrangement Act (CCA) bankruptcy protection (the Canadian version of Chapter 11), after reporting losses of over $500 million for the year 2002 and in March 2003. Meanwhile WestJet, like Southwest continues to show profitability, while two new carriers, Jetsgo and CanJet (reborn), have entered the market.

Looking at Europe, the picture is much the same, with large full-service airlines (FSAs hereafter) such as British Airways and Lufthansa sustaining losses and suffering financial difficulties, while value-based airlines (VBAs) like Ryanair and EasyJet continue to grow and prosper. Until recently, Asian air travel markets were performing somewhat better than in North America, however the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic had a severe negative effect on many Asian airlines.2

Clearly, the current environment is linked to several independent negative demand shocks that have hit the industry hard.3 A broad multi-country macroeconomic slowdown was already underway in 2001, prior to the 9–11 tragedy, which gave rise to the ‘war on terrorism’ followed by the recent military action in Iraq. Finally, the SARS virus has not only severely diminished the demand for travel to areas where SARS has broken out and led to fatalities, but it has also helped to create yet another reason for travellers to avoid visiting airports or travelling on aircraft, based on a perceived risk of infection. All of these factors have created an environment where limited demand and price competition has favoured the survival of airlines with a low-cost, low-price focus.

In this paper we examine the evolution of air transport networks after economic deregulation, and the connection between networks and business strategies, in an environment where regulatory changes continue to change the rules of the game.

2. The story so far

The deregulation of the US domestic airline industry in 1978 was the precursor of similar moves by most other developed economies in Europe (beginning 1992–1997), Canada (beginning in 1984), Australia (1990) and New Zealand (1986).4 The argument was that the industry was mature and capable of surviving under open market conditions subject to the forces of competition rather than under economic regulation.5

Prior to deregulation in the US, some airlines had already organized themselves into hub-and-spoke networks. Delta Airlines, for example, had organized its network into a hub at Atlanta with multiple spokes. Other carriers had evolved more linear networks with generally full connectivity and were reluctant to shift to hub-and-spoke for two reasons. First, regulations required permission to exit markets and such exit requests would likely lead to another carrier entering to serve ‘public need’. Secondly, under regulation it was not easy to achieve the demand side benefits associated with networks because of regulatory barriers to entry. In the era of economic regulation the choice of frequency and ancillary service competition were a direct result of being constrained in fare and market entry competition. With deregulation, airlines gained the freedom to adapt their strategies to meet market demand and to reorganize themselves spatially. Consequently, hub-and-spoke became the dominant choice of network structure.

The hub-and-spoke network structure was perceived to add value on both the demand and cost side. On the demand side, passengers gained access to broad geographic and service coverage, with the potential for frequent flights to a large number of destinations.6 Large carriers provided lower search and transactions costs for passengers and reduced through lower time costs of connections. They also created travel products with high convenience and service levels—reduced likelihood of lost luggage, in-flight meals and bar service for example. The FSA business model thus favoured high service levels which helped to build the market the market at a time when air travel was an unusual or infrequent activity for many individuals. Building the market not only meant encouraging more air travel but also expanding the size of the network which increased connectivity and improved aircraft utilization.

On the cost side the industry was shown to have few if any economies of scale, but there were significant economies of density. Feeding spokes from smaller centres into a hub airport enabled full service carriers to operate large aircraft between major centres with passenger volumes that lowered costs per available seat.

An early exception to the hub-and-spoke network model was Southwest Airlines. In the US, Southwest Airlines was the original ‘VBA’ representing a strategy designed to build the market for consumers whose main loyalty is to low-price travel. This proved to be a sustainable business model and Southwest's success was to create a blueprint for the creation of other VBAs around the world. The evolution has also been assisted by the disappearance of charter airlines with deregulation as FSAs served a larger scope of the demand function through their yield management system.

Meanwhile, benefits of operating a large hub-and-spoke network in a growing market led to merger waves in the US (mid-1980s) and in Canada (late-1980s) and consolidation in other countries of the world. Large firms had advantages from the demand side, since they were favoured by many passengers and most importantly by high yield business passengers. They also had advantages from the supply side due to economies of density and economies of stage length.7 In most countries other than the US there tended to be high industry concentration with one or at most two major carriers. It was also true that in most every country except the US there was a national (or most favoured) carrier that was privatized at the time of deregulation or soon thereafter.

In Canada in 1995 the Open Skies agreement with the US was brought in.8 Around this time we a new generation of VBAs emerged. In Europe, Ryanair and EasyJet experienced rapid and dramatic growth following deregulation within the EU. Some FSAs responded by creating their own VBAs: British Airways created GO, KLM created BUZZ and British Midland created BMiBaby for example. WestJet airlines started service in western Canada in 1996 serving three destinations and has grown continuously since that time.

Canadian Airlines, faced with increased competition in the west from WestJet as well as aggressive competition from Air Canada on longer haul routes, was in a severe financial by the late 1990s. A bidding war for a merged Air Canada and Canadian was initiated and in 2000, Air Canada emerged the winner with a ‘winners curse’, having assumed substantial debt and constraining service and labour agreements. Canada now had one FSA and three or four smaller airlines, two of which were VBAs.

In the new millennium, some consolidation has begun to occur amongst VBAs in Europe with the merger of, EasyJet and GO in 2002, and the acquisition of BUZZ by Ryanair in 2003. More importantly perhaps, the VBA model has emerged as a global phenomenon with VBA carriers such as Virgin Blue in Australia, GOL in Brazil, Germania and Hapag-Lloyd in Germany and Air Asia in Malaysia.

Looking at aviation markets since the turn of the century, casual observation would suggest that a combination of market circumstances created an opportunity for the propagation of the VBA business model—with a proven blueprint provided by Southwest Airlines. However a question remains as to whether something else more fundamental has been going on in the industry to cause the large airlines and potentially larger alliances to falter and fade. If the causal impetus of the current crisis was limited to cyclical macro factors combined with independent demand shocks, then one would expect the institutions that were previously dominant to re-emerge once demand rebounds. If this seems unlikely it is because the underlying market environment has evolved into a new market structure, one in which old business models and practices are no longer viable or desirable. The evolution of business strategies and markets, like biological evolution is subject to the forces of selection. Airlines who cannot or do not adapt their business model to long-lasting changes in the environment will disappear, to be replaced by those companies whose strategies better fit the evolved market structure. But to understand the emerging strategic interactions and outcomes of airlines one must appreciate that in this industry, business strategies are necessarily tied to network choices.

3. Network structure and business strategy

The organization of production spatially in air transportation networks confers both demand and supply side network economies and the choice of network structure by a carrier necessarily reflects aspects of its business model and will exhibit different revenue and cost drivers. In this section we outline important characteristics of the business strategy and network structures of two competing business models: the full service strategy (utilizing a hub-and-spoke network) and the low cost strategy model which operates under a partial point-to-point network structure.

3.1. Hub-and-spoke networks and the full-service strategy

The full service business model is predicated on broad service in product and in geography bringing customers to an array of destinations with flexibility and available capacity to accommodate different routings, no-shows and flight changes. The broad array of destinations and multiple spokes requires a variety of aircraft with differing capacities and performance characteristics. The variety increases capital, labour and operating costs. This business model labours under cost penalties and lower productivity of hub-and-spoke operations including long aircraft turns, connection slack, congestion, and personnel and baggage online connections. These features take time, resources and labour, all of which are expensive and are not easily avoided. The hub-and-spoke system is also conditional on airport and airway infrastructure, information provision through computer reservation and highly sophisticated yield management systems.

The network effects that favoured hub and spoke over linear connected networks lie in the compatibility of flights and the internalization of pricing externalities between links in the network. A carrier offering flights from city A to city B through city H (a hub) is able to collect traffic from many origins and place them on a large aircraft flying from H to B, thereby achieving density economies. In contrast A carrier flying directly from A to B can achieve some direct density economies but more importantly gains aircraft utilization economies. In the period following deregulation, density economies were larger than aircraft utilization economies on many routes, owing to the limited size of many origin and destination markets.

On the demand side, FSAs could maximize the revenue of the entire network by internalizing the externalities created by complementarities between links in the network. In our simple example, of a flight from A to C via hub H the carrier has to consider how pricing of the AH link might affect the demand for service on the HB link. If the service were offered by separate companies, the company serving AH will take no consideration of how the fare it charged would influence the demand on the HB link since it has no right to the revenue on that link. The FSA business model thus creates complexity as the network grows, making the system work effectively requires additional features most notably, yield management and product distribution. In the period following deregulation, technological progress provided the means to manage this complexity, with large information systems and in particular computer reservation systems. Computer reservation systems make possible sophisticated flight revenue management, the development of loyalty programs, effective product distribution, revenue accounting and load dispatch. They also drive aircraft capacity, frequency and scheduling decisions. As a consequence, the FSA business model places relative importance on managing complex schedules and pricing systems with a focus on profitability of the network as a whole rather than individual links.

The FSA business model favours a high level of service and the creation of a large service bundle (in-flight entertainment, meals, drinks, large numbers of ticketing counters at the hub, etc.) which serves to maximize the revenue yields from business and long-haul travel. An important part of the business service bundle is the convenience that is created through fully flexible tickets and high flight frequencies. High frequencies can be developed on spoke routes using smaller feed aircraft, and the use of a hub with feed traffic from spokes allows more flights for a given traffic density and cost level. More flights reduce total trip time, with increased flexibility. Thus, the hub-and-spoke system leads to the development of feed arrangements along spokes. Indeed these domestic feeds contributed to the development of international alliances in which one airline would feed another utilizing the capacity of both to increase service and pricing.

3.2. Point-to-point networks and the low-cost strategy

Like the FSA model, the VBA business plan creates a network structure that can promote connectivity but in contrast trades off lower levels of service, measured both in capacity and frequency, against lower fares. In all cases the structure of the network is a key factor in the success of VBAs even in the current economic and demand downturn. VBAs tend to exhibit common product and process design characteristics that enable them to operate at a much lower cost per unit of output.9

On the demand side, VBAs have created a unique value proposition through product and process design that enables them to eliminate, or “unbundle” certain service features in exchange for a lower fare. These service feature trade-offs are typically: less frequency, no meals, no free, or any, alcoholic beverages, more passengers per flight attendant, no lounge, no interlining or code-sharing, electronic tickets, no pre-assigned seating, and less leg room. Most importantly the VBA does not attempt to connect its network although their may be connecting nodes. It also has people use their own time to access or feed the airport.10

There are several key areas in process design (the way in which the product is delivered to the consumer) for a VBA that result in significant savings over a full service carrier. One of the primary forms of process design savings is in the planning of point-to-point city pair flights, focusing on the local origin and destination market rather than developing hub systems. In practice, this means that flights are scheduled without connections and stops in other cities. This could also be considered product design, as the passenger notices the benefit of travelling directly to their desired destination rather than through a hub. Rather than having a bank of flights arrive at airports at the same time, low-cost carriers spread out the staffing, ground handling, maintenance, food services, bridge and gate requirements at each airport to achieve savings.

Another less obvious, but important cost saving can be found in the organization design and culture of the company. It is worth noting at this point that the innovator of product, process, and organizational re-design is generally accepted to be Southwest Airlines. Many low-cost start-ups have attempted to replicate that model as closely as possible; however, the hardest area to replicate has proved to be the organization design and culture.11

Extending the “look and feel” to the aircraft, there is a noticeable strategy for low-cost airlines. Successful VBAs focus on a homogeneous fleet type (mostly the Boeing 737 but this is changing; e.g. Jet Blue with A320 fleet). The advantages of a ‘common fleet’ are numerous. Purchasing power is one—with the obvious exception of the aircraft itself, heavy maintenance, parts, supplies; even safety cards are purchased in one model for the entire fleet. Training costs are reduced—with only one type of fleet, not only do employees focus on one aircraft and become specialists, but economies of density can be achieved in training.

The choice of airports is typically another source of savings. Low-cost carriers tend to focus on secondary airports that have excess capacity and are willing to forego some airside revenues in exchange for non-airside revenues that are developed as a result of the traffic stimulated from low-cost airlines. In simpler terms, secondary airports charge less for landing and terminal fees and make up the difference with commercial activity created by the additional passengers. Further, secondary airports are less congested, allowing for faster turn times and more efficient use of staff and the aircraft. The average taxi times shown in Table 1 (below) are evidence of this with respect to Southwest in the US and one only has to consider the significant taxi times at Pearson Airport in Toronto to see why Hamilton is such an advantage for WestJet.

Table 1.

Aircraft utilization and operating cost of 737-300 and 737-700 fleets (3rd Q, 2001)

| Airline | Departures | Block hours | Flight hours | Average stage length (miles) | Average taxi time in minutesa | Cost per available seat mile (US cents) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontier | 4.5 | 11.2 | 9.8 | 933 | 19 | 5.6 |

| Southwest | 7.6 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 472 | 13 | 4.0 |

| ATA | 3.9 | 10.4 | 8.8 | 1032 | 25 | 4.3 |

| United | 5.0 | 9.3 | 7.5 | 639 | 22 | 8.1 |

| Continental | 3.4 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 895 | 26 | 6.2 |

| America West | 4.5 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 602 | 21 | 6.2 |

| US Airways | 5.1 | 8.3 | 6.3 | 466 | 24 | 8.9 |

| Delta | 4.6 | 7.8 | 6.1 | 546 | 22 | 7.1 |

Source: Aviation Daily, March 27, 2002.

Calculated using the difference between block times, flight times and dividing by the number of departures.

Essentially, VBAs have attempted to reduce the complexity and resulting cost of the product by unbundling those services that are not absolutely necessary. This unbundling extends to airport facilities as well, as VBAs struggle to avoid the costs of expensive primary airport facilities that were designed with full service carriers in mind. While the savings in product design are the most obvious to the passenger, it is the process changes that have produced greater savings for the airline.

The design of low-cost carriers facilitates some revenue advantages in addition to the many cost advantages, but it is the cost advantages that far outweigh any revenue benefits achieved. These revenue advantages included simplified fare structures with 3–4 fare levels, a simple ‘yield’ management system, and the ability to have one-way tickets. The simple fare structure also facilitates Internet booking. However, what is clearly evident is the choice of network is not independent of the firm strategy. The linear point-to-point network of VBAs allows it to achieve both cost and revenue advantages.

Table 1 below, compares key elements of operations for US airlines 737 fleets. One can readily see a dramatic cost advantage for Southwest Airlines compared to FSAs. In particular, Southwest is a market leader in aircraft utilization and average taxi times.

If one looks at the differences in the US between VBAs like Southwest and FSAs, there is a 2:1 cost difference. This difference is similar to what is found in Canada between WestJet and Air Canada as well as in Europe. These carriers buy the fuel and capital in the same market, and although there may be some difference between carriers due to hedging for example, these are not structural or permanent changes. The vast majority of the cost difference relates to product and process complexity. This complexity is directly tied to the design of their network structure.

Table 2 compares cost drivers for FSAs and VBAs in Europe. The table shows the key underlying cost drivers and where a VBA like Ryanair has an advantage over FSAs in crew and cabin personnel costs, airport charges and distribution costs. The first two are directly linked to network design. A hub-and-spoke network is service intensive and high cost. Even distribution cost-savings are related indirectly to network design because VBAs have simple products and use passengers’ time as an input to reduce airline connect costs.

Table 2.

Comparison of cost drivers for VBAS and FSAs

| Unit costs in US$ |

ASK adjusted for 800 km |

Stagelength (2001) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 major EU Flag carries | Ryanair | Easyjet | |

| Aircraft ownership | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Airport/ATC | 3.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Distribution | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Crew | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Total | 8.3 | 3.3 | 3.0 |

Source: Hyped for hopes: Europe's low-cost airlines (McKinsey Quarterly, No. 4, 2002).

In Europe, Ryanair has been a leader in the use of the internet for direct sales and ‘e-tickets’. In the US Southwest Airlines was an innovator in “e-ticketing”, and was also one of the first to initiate bookings on the Internet. VBAs avoid travel agency commissions and ticket production costs: in Canada, WestJet has stated that Internet booking account for approximately 40% of their sales, while in Europe, Ryanair claimed an Internet sales percentage of 91% in March 2002.12 While most VBAs have adopted direct selling via the internet, the strategy has been hard for FSAs to respond to with any speed given their complex pricing systems. Recent moves by full service carriers in the US and Canada to eliminate base commissions should prove to be interesting developments in the distribution chains of all airlines.

To some degree, VBAs have positioned themselves as market builders by creating point-to-point service in markets where it could not be warranted previously due to lower traffic volumes at higher FSA fares. VBAs not only stimulate traffic in the direct market of an airport, but studies have shown that VBAs have a much larger potential passenger catchment area than FSAs. The catchment area is defined as the geographic region surrounding an airport from which passengers are derived. While an FSA relies on a hub-and-spoke network to create catchment, low-cost carriers create the incentive for each customer to create their own spoke to the point of departure. Table 3 provides a summary of the alternative airline strategies pursued in Canada, and elsewhere in the world.

Table 3.

Description of strategies in the Canadian airline industry

| Strategy | High cost, Full service | Low cost, No frills | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network type | Hub-and-spoke, scheduled service | Point-to-point, scheduled service | Point-to-point, charter/scheduled | Point-to-point, charter | Point-to-point, scheduled |

| Characteristics | High fixed costs | Moderate fixed costs | Low fixed costs | Low fixed costs | Low costs |

| High labour costs | Moderate labour costs | Moderate labour costs | Low labour costs | Lower labour costs | |

| Inflexible job tasks | Moderate job tasks | Moderate job tasks flexibility | Flexible job tasks | Flexible job tasks | |

| Full service | Flexibility | Low-end full service | Low-end service | No frills service | |

| Multiple classes | Full service | Single and multiple classes | Single class (few wider seats) | Single class | |

| High Frequencies | Multiple classes | Low frequencies | Low frequencies | Increasing frequencies | |

| Low frequencies | |||||

| Example | Air Canada American, United, British Airways, JAL | Roots Air-failed in 2001 | Canada 3000, Royal Airlines (pre-merger)-failed in 2001 | Air Transat Skyservice | WestJet |

| CanJet | |||||

| Ryanair | |||||

| Southwest | |||||

| Jet Blue | |||||

Source: Korol (2000).

3.3. Survival of the fittest?

The trend worldwide thus far indicates two quite divergent business strategies. The entrenched FSA carriers’ focuses on developing hub and spoke networks while new entrants seem intent on creating low-cost, point-to-point structures. The hub and spoke system places a very high value on the feed traffic brought to the hub by the spokes, especially the business traffic therein, thereby creating a complex, marketing intense business where revenue is the key and where production costs are high. Inventory (of seats) is also kept high in order to meet the service demands of business travellers. The FSA strategy is a high cost strategy because the hub-and-spoke network structure means both reduced productivity for capital (aircraft) and labour (pilots, cabin crew, airport personnel) and increased costs due to self-induced congestion from closely spaced banks of aircraft.13

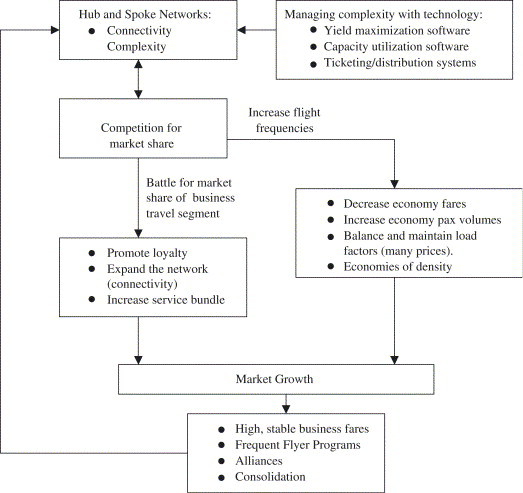

The FSA business strategy is sustainable as long as no subgroup of passengers can defect from the coalition of all passenger groups, and recognizing this, competition between FSAs included loyalty programs designed to protect each airline's coalition of passenger groups—frequent travellers in particular. The resulting market structure of competition between FSAs was thus a cozy oligopoly in which airlines competed on prices for some economy fares, but practiced complex price discrimination that allowed high yields on business travel. However, the vulnerability of the FSA business model was eventually revealed through the VBA strategy which (a) picked and chose only those origin-destination links that were profitable and (b) targeted price sensitive consumers.14 The potential therefore was not for business travellers to defect from FSAs (loyalty programs helped to maintain this segment of demand) but for leisure travellers and other infrequent flyers to be lured away by lower fares (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The rise of the FSA hub-and-spoke system.

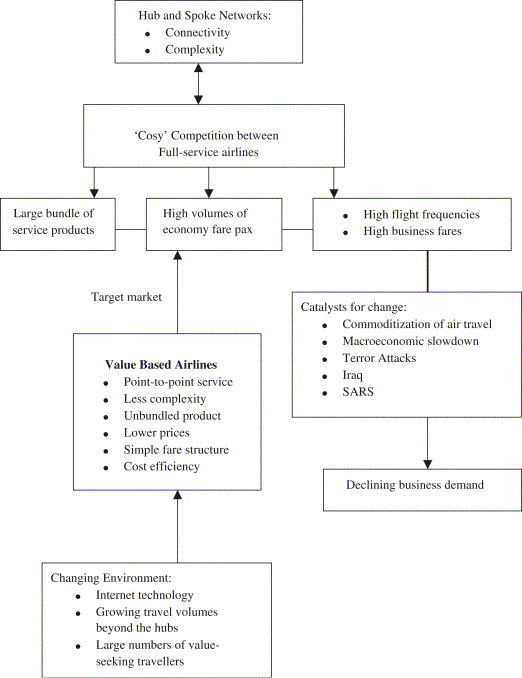

Fig. 2, Fig. 3 present a schemata that help to summarize the contributory factors that propagated the FSA hub-and-spoke system and made it dominant, followed by the growth of the VBA strategy along with the events and factors that now threaten the FSA model.

Fig. 2.

Hub-and-spoke networks under threat: the growth of VBA point-to-point networks.

Fig. 3.

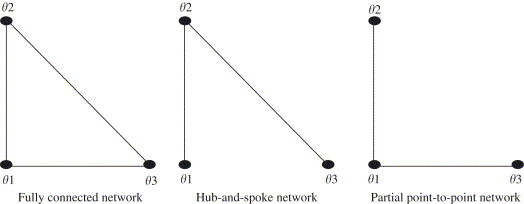

Alternative network structures.

4. The economics of networks and airline competition

In this section we set out a simple framework to explain the evolution of network equilibrium and show how it is tied to the business model. The linkage will depend on how the business models differ with respect to the integration of demand conditions, fixed and variable cost and network organization.

Let three nodes {, ,; (0,0), (0,1), (1,0)}, form the corner coordinates of an isosceles right triangle. The nodes and the sides of the triangle may thus represent a simple linear travel network that defines two ‘short-haul’ travel links [(, ) (, ) ]and one ‘long-haul’ link (, ). In this travel network, the nodes represent points of entry and exit to/from the network, thus if the network is assumed to be an air travel market, the nodes represent airports rather than cities. This may be important when considering congestion or other factors affecting passenger throughput at airports.

This simple network structure allows us to compare three possible structures for the supply of travel services: a complete (fully connected) point-to-point network (all travel constitutes a direct link between two nodes); a hub-and-spoke network (travel between and requires a connection through ) and limited (or partial) point-to-point network (selective direct links between nodes). These are illustrated in Fig. 3 below.

In the network structures featuring point-to-point travel, the utility of consumers who travel depends only on a single measure of the time duration of travel and a single measure of convenience. However in the hub-and-spoke network, travel between and requires a connection at , consequently the time duration of travel depends upon the summed distance . Furthermore, in a hub-and-spoke network, there is interdependence between the levels of convenience experienced by travellers. If there are frequent flights between and but infrequent flights between and , then travellers will experience delays at .

There has been an evolving literature on the economics of networks or more properly the economics of network configuration. Hendricks et al. (1995) show that economies of density can explain the hub-and-spoke system as the optimal system in the airline networks. The key to the explanation lies in the level of density economies. However, when comparing a point-to-point network they find the hub-and-spoke network is preferred when marginal costs are high and demand is low but given some fixed costs and intermediate values of variable costs a point-to-point network may be preferred. Shy (2001) shows that profit levels on a fully connected (FC) network are higher than on a hub-and-spoke network when variable flight costs are relatively low and passenger disutility with connections at hubs is high. What had not been explained well, until Pels et al. (2000) is the relative value of market size to achieve lower costs per available seat mile (ASM) versus economies of density.

Pels et al. (2000) explore the optimality of airline networks using linear marginal cost functions and linear, symmetric demand functions; and where is a returns to density parameter and is a measure of market size. The Pels model demonstrates the importance of fixed costs in determining the dominance of one network structure over another in terms of optimal profitability. In particular, the robustness of the hub-and-spoke network configuration claimed by earlier authors (Hendricks et al., 1995) comes into question.

In our three-node network, the Pels model generates two direct markets and one transfer market in the hub-and-spoke network, compared with three direct markets in the fully connected network. Defining aggregate demand as , the profits from a hub-and-spoke network, are:

| (1) |

while the profits of a FC network are:

| (2) |

More generally, for a network of size n, hub-and-spoke optimal profits are:

| (3) |

and FC profits are:

| (4) |

Under what conditions would an airline be indifferent between network structure? The market size at which profit maximizing prices and quantities equate the profits in each network structure is

| (5) |

where,

| (6) |

The two possible values of implied by (5) represent upper and lower boundaries on the market size for which the hub-and-spoke network and the fully connected network generate the same level of optimal profits. These boundary values are of course conditional on given values of the density economies parameter () fixed costs (f), and the size of the network (n). These parameters can provide a partial explanation for the transition from FC to hub-and-spoke network structures after deregulation.

With relatively low returns to density, and low fixed costs per link, even in a growing market, the hub-and-spoke structure generates inferior profits compared with the FC network, except when the market size () is extremely high. However with high fixed costs per network link, the hub-and-spoke structure begins to dominate at a relatively small market size and this advantage is amplified as the size of the network grows. Importantly in this model, dominance does not mean that the inferior network structure is unprofitable. In () space, the feasible area (defining profitability) of the FC structure encompasses that of the hub-and-spoke structure. This accommodates the observation that not all airlines adopted the hub-and-spoke network model following deregulation.

Where the model runs into difficulties is in explaining the emergence of limited point-to-point networks and the VBA model. It is the symmetric structure of the model that renders it unable to capture some important elements of the environment in which VBAs have been able to thrive. In particular, three elements of asymmetry are missing. First, the model does not allow for asymmetric demand growth between nodes in the network. With market growth, returns to density can increase on a subset of links that would have been feeder spokes in the hub-and-spoke system when the market was less developed. These links may still be infeasible for FSAs but become feasible and profitable as independent point-to-point operations, providing an airline has low enough costs. Second, the model does not distinguish between market demand segments and therefore cannot capture the gradual commoditization of air travel, as more consumers become frequent flyers. To many consumers today, air travel is no longer an exotic product with an air of mystery and an association with wealth and luxury. There has been an evolution of preferences that reflects the perception that air travel is just another means of getting from A to B. As the perceived nature of the product becomes more commodity-like, consumers become more price sensitive and are willing to trade off elements of service for lower prices.15 VBAs use their low fares to grow the market by competing with other activities. Their low cost structure permits such a strategy. FSAs cannot do this to any degree because of their choice of bundled product and higher costs.

Third, the model does not capture important asymmetries in the costs of FSAs and VBAs, such that VBAs have significantly lower marginal and fixed costs. Notice that the dominance of the hub-and-spoke structure over the FC network relies in part on the cost disadvantage of a fixed cost per link, which becomes prohibitive in the FC network as the number of nodes (n) gets large. VBAs do not suffer from this disadvantage because they can pick and choose only those nodes that are profitable. Furthermore, FSAs variable costs are higher because of the higher fixed costs associated with their choice of hub-and-spoke network.

5. Stability, competition and regulation

It would seem that with each new economic cycle, the evolution of the airline industry brings about an industry reconfiguration. Several researchers have suggested that this is consistent with an industry structure with an ‘empty core’, meaning non-existence of a natural market equilibrium. Button (2003) makes the argument as follows. We know that a structural shift in the composition (i.e., more low-cost airlines) of the industry is occurring and travel substitutes are pushing down fares and traffic. We also observe that heightened security has increased the time and transacting costs of trips and these are driving away business, particularly short haul business trips. As legacy airlines shrink and die away, new airlines emerge and take up the employment and market slack.

The notion of the ‘empty core’ problem in economics is essentially a characterization of markets where too few competitors generate supra-normal profits for incumbents, which then attracts entry. However entry creates frenzied competition in a war-of-attrition game environment: the additional competition induced by entry results in market and revenue shares that produce losses for all the market participants. Consequently entry and competition leads to exit and a solidification of market shares by the remaining competitors who then earn supra-normal profits that once again will attract entry.

While there is some intuitive appeal to explaining the dynamic nature of the industry resulting from an innate absence of stability in the market structure, there are theoretical problems with this perspective.16 The fundamental problem with the empty core concept is that its roots lie in models of exogenous market structure that impose (via assumptions) the conditions of the empty core rather than deriving it as the result of decisions made by potential or incumbent market participants. In particular, for the empty core to perpetuate itself, entrants must be either ill advised or have some unspecified reason for optimism. In contrast, modern industrial organization theory in economics is concerned with understanding endogenously determined market structures. In such models, the number of firms and their market conduct emerge as the result of a decisions to enter or exit the market and decisions concerning capacity, quantity and price.

Part of the general problem of modeling an evolving market structure is to understand that incumbents and potential entrants to the market construct expectations with respect to their respective market shares in any post-entry market. A potential entrant might be attracted by the known or perceived level of profits being earned by the incumbents, but must consider how many new consumers they can attract to their product in addition to the market share that can appropriated from the incumbent firms. This will depend in part upon natural (technological) and strategic barriers to entry, and on the response that can be expected if entry occurs. Thus entry only occurs if the expected profits exceed the sunk costs of entry. While natural variation in demand conditions may induce firms to make errors in their predictions, resulting in entry and exit decisions, this is not the same thing as an ‘empty core’.17

In the air travel industry, incumbent firms (especially FSAs) spend considerable resources to protect their market shares from internal and external competition. The use of frequent flier points along with marketing and branding serve this purpose. These actions raise the barriers to entry for airlines operating similar business models.

What about the threat of entry or the expansion of operations by VBAs? Could this lead to exit by FSAs? There may be legitimate concern from FSAs concerning the sustainability of the full-service business model when faced with low-cost competition. In particular, the use of frequency as an attribute of service quality by FSAs generates revenues from high-value business travellers, but these revenues only translate into profits when there are enough economy travellers to satisfy load factors. So, to the extent that VBAs steal away market share from FSAs they put pressure on the viability of this aspect of the FSA business model. The greatest threat to the FSA from a VBA is that a lower the fare structure offered to a subset of passengers may induce the FSA to expand the proportion of seats offered to lower fares within the yield management system. This will occur with those VBAs like Southwest, Virgin Blue in Australia and easyjet that do attempt to attract the business traveller from small and medium size firms. However, carriers like Ryanair and Westjet have a lower impact on overall fare structure since their frequencies are lower and the FSA can target the VBAs flights.18

While FSAs may find themselves engaged in price and/or quality competition, the economics of price competition with differentiated products suggests that such markets can sustain oligopoly structures in which firms earn positive profits. This occurs because the prices of competing firms become strategic complements. That is, when one firm increases its price, the profit maximizing response of competitors is to raise price also and there are many dimensions on which airlines can product differentiate within the FSA business model.19

There is no question FSAs have higher seat mile costs than VBAs. The problem comes about when FSAs view their costs as being predominately fixed and hence marginal costs as being very low. This ‘myopic’ view ignores the need to cover the long run cost of capital. This in conjunction with the argument that network revenue contribution justifies most all routes, leads to excessive network size and severe price discounting.20 However, when economies are buoyant, high yield traffic provides sufficient revenues to cover costs and provide substantial profit. In their assessment of the US airline industry, Morrison and Winston (1995) argue that the vast majority of losses incurred by FSAs up to that point were due to their own fare, and fare war, strategies. It must be remembered that FSAs co-exist with Southwest in large numbers of markets in the US.

What response would we expect from an FSA to limited competition from a VBA on selected links of its hub-and-spoke network? Given the FSA focus on maximization of aggregate network revenues and a cognisance that successful VBA entry could steal away their base of economy fare consumers (used to generate the frequencies that provide high yield revenues), one might expect aggressive price competition to either prevent entry or to hasten the exit of a VBA rival. This creates a problem for competition bureaus around the world as VBAs file an increasing number of predatory pricing charges against FSAs. Similarly, the ability of FSAs to compete as hub-and-spoke carriers against a competitive threat from VBAs is constrained by the rules of the game as defined by competition policy.

In Canada, Air Canada faces a charge of predatory pricing for its competition against CanJet and WestJet in Eastern Canada. In the US, American Airlines won its case in a predatory pricing charge brought by three VBAs: Vanguard Airlines, Sun Jet and Western Pacific Airlines. In Germany, both Lufthansa and Deutsche BA have been charged with predatory pricing. In Australia, Qantas also faces predatory pricing charges.

Gillen and Morrison (2003) points out three important dimensions of predatory pricing in air travel markets. First, demand complementarities in hub-and-spoke networks lead FSAs to focus on ‘beyond revenues’—the revenue generated by a series of flights in an itinerary rather than the revenues generated by any one leg of the trip. FSAs therefore justify aggressive price competition with a VBA as a means of using the fare on that link (from an origin node to the hub node for example) as a way of maximizing the beyond revenues created when passengers purchase travel on additional links (from the hub to other nodes in the network). The problem with this argument is that promotional pricing is implicitly a bundling argument, where the airline bundles links in the network to maximize revenue. However when FSAs compete fiercely on price against VBAs, the price on that link is not limited to those customers who demand beyond travel. Therefore, whether or not there is an intent to engage in predatory pricing, the effect is predatory as it deprives the VBA of customers who do not demand beyond travel.

A second dimension of predatory pricing is vertical product differentiation. FSAs competition authorities to support the view that they the right to match prices of a rival VBA. However, the bundle of services offered by FSAs constitutes a more valuable package. In particular, the provision of frequent flyer programs creates a situation where matching the price of a VBA is ‘de facto’ price undercutting, adjusting for product differentiation. A recent case between the VBA Germania and Lufthansa resulted in the Bundeskartellamt (the German competition authority) imposing a price premium restriction on Lufthansa that prevented the FSA from matching the VBAs prices.

A third important dimension of predatory pricing in air travel markets is the ability which FSAs have to shift capacity around a hub-and-spoke network, which necessarily requires a mixed fleet with variable seating capacities. In standard limit output models of entry deterrence, an investment in capacity is not a credible threat to of price competition if the entrant conjectures that the incumbent will not use that capacity once entry occurs. Such models utilize the notion that a capacity investment is an irreversible commitment and that valuable reputation effects cannot be generated by the incumbent engaging in ‘irrational’ price competition. However in a hub-and-spoke network, an FSA can make a credible threat to transfer capacity to a particular link in the network in support of aggressive price competition, with the knowledge that the capacity can be redeployed elsewhere in the network when the competitive threat is over. This creates a positive barrier to entry with reputation effects occurring in those instances where entry occurs. Such was the case when CanJet and WestJet met with aggressive price competition from Air Canada on flights from Monkton NB to Toronto (Air Canada and CanJet) and Hamilton (WestJet). The FSA defense against such charges is that aircraft do not constitute an avoidable cost and should not be included in any price-cost test of predation. Yet while aircraft are not avoidable with respect to the network, they are avoidable to the extent they can be redeployed around the network. If aircraft costs become included in measures of predation under competition laws, this will limit the success of price competition as a competitive response by an FSAs responding to VBA entry.

In the current environment, competition policy rules are not well specified and the uncertainty does nothing to protect competition or to enhance the viability of air travel markets. However there has been increased academic interest in the issue and it seems likely that given the number of cases, some policy changes will be made (e.g., Ross and Stanbury, 2001). Once again, the way in which FSAs have responded to competition from VBAs reflects their network model, and competition policy decisions that prevent capacity shifting, price matching and inclusion of ‘beyond revenues’ will severely constrain the set of strategies an FSA can employ without causing some fundamental changes in the business model and corresponding network structure.

6. So where are we headed?

In evolution, the notion of selection dynamics lead us to expect that unsuccessful strategies will be abandoned and successful strategies will be copied or imitated. We have already observed FSAs attempts to replicate the VBA business model through the creation of fighting brands. Air Canada created Tango, Zip, Jazz, and Jetz. Few other carriers worldwide have followed such an extensive re-branding. In Europe, British Airways created GO and KLM created BUZZ, both of which have since been sold and swallowed up by other VBAs. Qantas has created a low cost long haul carrier—Australian Airlines. Meanwhile, Air New Zealand, Lufthansa, Delta and United are moving in the direction of a low-price–low-cost brand.

We are also seeing attempts by FSAs to simplify their fare structures and exploit the cost savings from direct sales over the internet. Thus there do seem to be evolutionary forces that are moving airlines away from the hub-and-spoke network in the direction of providing connections as distinct from true hubbing.

American Airlines is using a ‘rolling hub’ concept, which does exactly as its name implies. The purpose is to reduce costs through both fewer factors such as aircraft and labour and to increase productivity. The first step is to ‘de-peak’ the hub, which means not having banks as tightly integrated. This reduces the amount of own congestion created at hubs by the hubbing carrier and reduces aircraft needed. It also reduces service quality but it has become clear that the traditionally high yield business passenger who valued such time-savings is no longer willing to pay the very high costs that are incurred in producing them. However, as an example, American Airlines has reduced daily flights at Chicago so with the new schedules it has increased the total elapsed time of flights by an average of 10 min. Elapsed time is a competitive issue for airlines as they vie for high-yield passengers who, as a group, have abandoned the airlines and caused revenues to slump. But that 10-min average lengthening of elapsed time appears to be a negative American is willing to accept in exchange for the benefits.

At Chicago, where the new spread-out schedule was introduced in April, American has been able to operate 330 daily flights with five fewer aircraft and four fewer gates and a manpower reduction of 4–5%.21 The change has cleared the way for a smoother flow of aircraft departures and has saved taxi time.22 It is likely that American will try to keep to the schedule and be disinclined to hold aircraft to accommodate late arriving connection passengers. While this may appear to be a service reduction it in fact may not, since on-time performance has improved.23

7. Conclusions

The evolution of networks in today's environment will be based on the choice of business model that airlines make. This is tied to evolving demand conditions, the developing technologies of aircraft and infrastructure and the strategic choices of airlines. As we have seen, the hub-and-spoke system is an endogenous choice for FSA while the linear FC network provides the same scope for VBAs. The threat to the hub-and-spoke network is the threat to bundled product of FSAs. The hub-and-spoke network will only disappear if the FSA cannot implement a lower cost structure business model and at the same time provide the service and coverage that higher yield passengers demand. The higher yield passengers have not disappeared the market has only become somewhat smaller and certainly more fare sensitive, on average.

FSAs have responded to VBAs by trying to copy elements of their business strategy including reduced in-flight service, low cost [fighting] brands, and more point-to-point service. However, the ability of FSA to co-exist with VBA and hence hub-and-spoke networks with linear networks is to redesign their products and provide incentives for passengers to allow a reduction in product, process and organizational complexity. This is a difficult challenge since they face complex demands, resulting in the design of a complex product and delivered in a complex network, which is a characteristic of the product. For example, no-shows are a large cost for FSA and they have to design their systems in such a way as to accommodate the no-shows. This includes over-booking and the introduction of demand variability. This uncertain demand arises because airlines have induced it with service to their high-yield passengers. Putting in place a set of incentives to reduce no-shows would lower costs because the complexity would be reduced or eliminated. One should have complexity only when it adds value. Another costly feature of serving business travel is to maintain sufficient inventory of seats in markets to meet the time sensitive demands of business travellers.

The hub-and-spoke structure is complex, the business processes are complex and these create costs. A hub-and-spoke network lowers productivity and increases variable and fixed costs, but these are not characteristics inherent in the hub-and-spoke design. They are inherent in the way FSA use the hub-and-spoke network to deliver and add value to their product. This is because the processes are complex even though the complexity is needed for a smaller, more demanding, higher yield set of customers. The redesigning of business processes moves the FSA between cost functions and not simply down their existing cost function but they will not duplicate the cost advantage of VBAs. The network structure drives pricing, fleet and service strategies and the network structure is ultimately conditional on the size and preferences in the market.

What of the future and what factors will affect the evolution of network design and scope? Airline markets with their networks are continuously evolving. What took place in the US 10 years ago is now occurring in Europe. A ‘modern’ feature of networks is the strategic alliance. Alliances between airlines allow them to extend their network, improve their product and service choice but at a cost. Alliances are a feature associated with FSAs not VBAs. It may be that as FSAs reposition themselves they will make greater use of alliances. VBAs on the other hand will rely more on interlining to extend their market reach. Interlining is made more cost effective with modern technologies but also with airports having an incentive to offer such services rather than have the airlines provide them. Airports as modern businesses will have a more active role in shaping airline networks in the future.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for travel to this conference, provided by funds from Wilfrid Laurier University and the SSHRC Institutional Grant awarded to the university.

Footnotes

This scenario is true in most other countries as well; Australia, New Zealand and the EU.

SARS began in China and quickly spread to Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, Canada and is emerging in the US and EU. Cathay Pacific, based in Hong Kong has seen passenger traffic drop from 35,000 per day to less than 10,000.

People want to get from A to B for business, family and vacation purposes. The demand will therefore depend upon the overall health of the economy but it will also depend on the competitive environment for air services. The growth in air travel over the last few decades was not simply a matter of general economic growth but also due to changes in the rules governing trade, such as under the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the liberalization of markets, both domestic and internationally which led to falling airfares and broader service. The demand for air travel has also grown due to shifts in the structure of economies from manufacturing to service economies and service industries are more aviation intensive than manufacturing. Developed economies as in Europe and North America as well as Australia and New Zealand, have an increasing proportion of GDP provided by service industries particularly tourism. One sector that is highly aviation intensive is the high technology sector. It is footloose and therefore can locate just about anywhere; the primary input is human capital. It can locate assembly in low-cost countries and this was enhanced under new trade liberalization with the WTO.

Canada's deregulation was not formalised under the National Transportation Act until 1987. Australia and New Zealand signed an open skies agreement in 2000, which created a single Australia–New Zealand air market, including the right of cabotage. Canada and the US signed an open skies agreement well in 1996 but not nearly so liberal as the Australian–New Zealand one.

In contrast to deregulation within domestic borders, international aviation has been slower to introduce unilateral liberalization. Consequently the degree of regulation varies across routes, fares, capacity, entry points (airports) and other aspects of airline operations depending upon the countries involved. The US–UK, German, Netherlands and Korea bilaterals are quite liberal, for example. In some cases, however, most notably in Australasia and Europe, there have been regional air trade pacts, which have deregulated markets between and within countries. The open skies agreement between Canada and the US is similar to these regional agreements.

Like telephone networks, adding a point to a hub and spoke system creates 2n connections.

Unit costs decrease as stage length increases but at a diminishing rate.

There was a phase in period for select airports in Canada as well as different initial rules for US and Canadian carriers.

Product design refers to the “look and feel” of a product, and is the most visible difference between low-cost and full service carriers to the airline passenger.

Southwest Airlines claims passengers will travel up to 1–2 h to access an airport with lower fares. In Canada, Westjet has observed the same phenomena.

It should also be noted that the VBA model is not generic. Different low cost carriers do different things and like all businesses we see continual redefinition of the model.

WestJet estimated that a typical ticket booked through their call centre costs roughly $12, while the same booking through the Internet costs around 50 cents.

Airlines were able to reduce their costs to some degree by purchasing ground services from third parties. Unfortunately they could not do this with other processes of the business.

VBAs will also not hesitate to exit a market if it is not profitable (e.g. WestJet's recent decision to leave Sault St. Marie and Sudbury) while FSAs are reluctant to exit for fear of missing feed traffic and beyond revenue.

To model a such a demand system we need a consumer utility function of the form, ; where Y represents dollar income per period and represents travel trips per period. V is an index of travel convenience, related to flight frequency and P is the delivered price of travel. This reduces each consumer's choice problem to consumption of a composite commodity priced at $1, and the possibility of taking at most one trip per period. Utility is increasing in V and decreasing in P, thus travellers are willing to trade-off convenience for a lower delivered price. Diversity in the willingness to trade off convenience for would be represented by distribution for Y, , and V over some range of parameter values. Thus the growth of value-based demand for air travel would be represented by an increase in the density of consumers with relatively low value of these parameters.

The empty core theory is often applied to industries that exhibit significant economies of scale, airlines are thought generally to have limited if any scale economies but they do exhibit significant density economies. These density economies are viewed as providing conditions for an empty core. The proponents however only argue on the basis of FSAs business model.

This has led some to lobby for renewed government intervention in markets or anti-trust immunity for small numbers of firms. However, if natural variability is a key factor in explaining industry dynamics, there is nothing to suggest that governments have superior information or ability to manipulate the market structure to the public benefit.

There are some routes in which WestJet does have high frequencies and has significantly impacted mainline carriers. (e.g. Calgary-Abbotsford)

A standard result in the industrial organization literature is that competing firms engaged in price competition will earn positive economic profits when their products are differentiated.

The beyond or network revenue argument is used by many FSAs to justify not abandoning markets or charging very low prices on some routes. The argument is that if we did not have all the service from A to B we would never receive the revenue from passengers who are travelling from B to C. In reality this is rarely true. When FSAs add up the value of each route including its beyond revenue the aggregate far exceeds the total revenue of the company. The result is a failure to abandon uneconomic routes. The three current most profitable airlines among the FSAs, Qantas, Lufthansa and BA, do not use beyond revenue in assessing route profitability.

American has also reduced its turn around at spoke cities from 2.5 h previously to approximately 42 min.

As a result of smoother traffic flows, American has been operating at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport with nine fewer mainline aircraft and two fewer regional aircraft. At Chicago, the improved efficiency has allowed American to take five aircraft off the schedule, three large jets and two American Eagle aircraft. American estimates savings of $100 million a year from reduced costs for fuel, facilities and personnel, part of the $2 billion in permanent costs it has trimmed from its expense sheet. The new flight schedule has brought unexpected cost relief at the hubs but also at the many “spoke” cities served from these major airports. Aviation Week and Space Technology, September 2, 2002 and February 18, 2003.

Interestingly, from an airport perspective the passenger may not spend more total elapsed time but simply more time in the terminal and less time in the airplane. This may provide opportunities for non-aviation revenue strategies.

References

- Button K.J. Empty cores in Airline Markets. Journal of Air Transport Management. 2003;9:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen D., Morrison W.G. Bundling, integration and the delivered price of air travel: are low-cost carriers full-service competitors? Journal of Air Transport Management. 2003;9:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks K., Piccione M., Tan G. The economics of hubs: the case of monopoly. Rand Journal of Economics. 1995;28:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S.A., Winston C. Brookings; Washington DC: 1995. The Evolution of the Airline Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Pels E., Nijkamp P., Rietveld P. A note on the optimality of airline networks. Economic Letters. 2000;69:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ross T., Stanbury Wi. MIMEO; University of British Columbia: 2001. Dealing with predatory conduct in the Canadian airline industry: a proposal. [Google Scholar]

- Shy Oz. Cambridge University Press; London: 2001. The Economics of Network Industries. [Google Scholar]