Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major problem of health and disability, with a relevant economic impact on society (e.g., €177 billion in Europe). Despite important advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment, The primary causes of AD remain elusive, accurate biomarkers are not well characterized, and available pharmacological treatments are not cost-effective. As a complex disorder, AD is polygenic and multifactorial: hundreds of defective genes distributed across the human genome may contribute to its pathogenesis (with the participation of diverse environmental factors, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and epigenetic phenomena) and lead to amyloid deposition, neurofibrillary tangle formation, and premature neuronal death. Future perspectives for the global management of AD predict that structural and functional genomics and proteomics may help in the search for reliable biomarkers, and that pharmacogenomics may be an option in optimizing drug development and therapeutics.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, APOE, Biomarkers, CYPs, Genetics, Genomics, Pathogenesis, Pharmacogenomics, Treatment

27.1. Overview

Since the identification of its pathogenic features by Alois Alzheimer in 1906, more than 90,000 papers have been published on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to date (2.5 million references on cancer since 1818; 1.6 million on cardiovascular disorders since 1927; and 1.01 million on central nervous system disorders since 1893) [1]. The number of people affected by dementia is becoming a public and socioeconomic concern in many countries all over the world, independent of economic conditions. The growth of the elderly population is a common phenomenon in both developed and developing countries, bringing about future challenges in terms of health policy and disability rates.

In the United States, rates for the leading causes of death are heart disease (200.2 per 100,000), cancer (180.7 per 100,000), and stroke (43.6 per 100,000). AD is the fifth leading cause of death in people older than 65 years of age, representing 71,600 deaths per year. AD affects approximately 5.4 million individuals in the United States and is estimated to affect up to 16 million by 2050 [2]. Disability caused by senility and dementia affects 9.2 per 1000 in the population aged 65–74 years, 33.5 per 1000 in those within the 75–84 range, and 83.4 per 1000 in the population over 85 years [3], [4]. In low- to middle-income countries, dementia makes the largest contribution to disability, with a median population-attributable prevalence fraction of 25.1%, followed by stroke (11.4%), limb impairment (10.5%), arthritis (9.9%), depression (8.3%), eyesight problems (6.8%), and gastrointestinal impairments (6.5%) [5].

In Western countries, AD is the most prevalent form of dementia (45–60%), followed by vascular dementia (30–40%), and mixed dementia (10–20%), which in people older than 85 years of age may account for more than 80% of cases.

The different forms of dementia pose several challenges to society and to the scientific community: (1) they represent an epidemiological problem and a socioeconomic, psychological, and family burden; (2) most of them have an obscure/complex pathogenesis; (3) their diagnosis is not easy and lacks specific biomarkers; and (4) their treatment is difficult and inefficient.

In terms of economic burden, approximately 10–20% of direct costs are associated with pharmacological treatment, with a gradual increase that parallels the severity of the disease. A Canadian study [6] shows that the mean total cost to treat patients with very mild AD is $367 per month, compared with $4063 per month for patients with severe or very severe AD. Only 20–30% of patients with dementia respond appropriately to conventional drugs, and the onset of adverse drug reactions imposes the need for other drugs to neutralize side effects, thus multiplying the initial cost of the pharmacological treatment and the health risk for the patients [7]. Wimo et al. [8] studied the economic impact of dementia in Europe in the EU-funded Eurocode project and found that the total cost of dementia in EU27 countries in 2008 was estimated to be €160 billion (€22,000 per dementia patient per year), of which 56% were costs of informal care. The corresponding costs for the whole of Europe were €177 billion. Informal caregiver costs were the largest cost component, accounting for about half to just over 60% of total societal costs, depending on the country and AD severity [9].

In addition (and related) to the problem of direct and indirect costs for the management of dementia, there is an alarming abuse of inappropriate psychotropic drug consumption worldwide. Antipsychotic medications are taken by more than 30% of elderly patients with dementia [10], and conventional antipsychotics are associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents [11].

Abuse, misuse, self-prescription, and uncontrolled medical prescription of CNS drugs are becoming major problems with unpredictable consequences for brain health. The pharmacological management of dementia is an issue of special concern because of the polymedication required to modulate its symptomatic complexity where cognitive decline, behavioral changes, and psychomotor deterioration coexist. In parallel, a growing body of fresh knowledge is emerging on the pathogenesis of dementia, together with data on the neurogenomics and pharmacogenomics of CNS disorders. The incorporation of this new armamentarium of molecular pathology and genomic medicine into daily medical practice, together with educational programs for the correct use of drugs, must help researchers and clinicians to (1) understand AD pathogenesis; (2) establish an early diagnosis; and (3) optimize therapeutics either as a preventive strategy or as formal symptomatic treatment [7], [12].

27.2. Toward a Personalized Medicine for Dementia and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Common features of neurodegenerative disorders include the following:

-

•

Polygenic/complex disorders in which genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors are involved

-

•

Deterioration of higher activities of the CNS

-

•

Multifactorial dysfunction in several brain circuits

-

•

Accumulation of toxic proteins in the nervous tissue

For instance, the neuropathological hallmarks of AD (amyloid deposition in senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangle formation, and neuronal loss) are merely the phenotypic expression of a pathogenic process in which different gene clusters and their products are potentially involved [7], [12].

A large number of the genes that form the structural architecture of the human genome are expressed in the brain in a time-dependent manner along the lifespan. The cellular complexity of the CNS (103 different cell types) and synapses (each of the 1011 neurons in the brain having around 103–104 synapses with a complex multiprotein structure integrated by 103 different proteins) requires very powerful technology for gene expression profiling, which is still in its very early stages and is not devoid of technical obstacles and limitations [13]. Transcripts of 16,896 genes have been measured in different CNS regions. Each region possesses its own unique transcriptome fingerprint that is independent of age, gender, and energy intake. Fewer than 10% of genes are affected by age, diet, or gender, with most of these changes occurring between middle and old age. Gender and energy restriction have robust influences on the hippocampal transcriptome of middle-aged animals. Prominent functional groups of age- and energy-sensitive genes are those encoding proteins involved in DNA damage responses, mitochondrial and proteasome functions, cell fate determination, and synaptic vesicle trafficking [14].

The introduction of novel procedures in an integral genomic medicine protocol for CNS disorders and dementia is imperative in drug development and in clinical practice in order to improve diagnostic accuracy and to optimize therapeutics. Personalized strategies, adapted to the complexity of each case, are essential to depict a clinical profile based on specific biomarkers correlating with individual genomic profiles [7], [15].

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of CNS disorders and dementia has advanced dramatically during the last 30 years, especially in terms of their molecular pathogenesis and genetics. The drug treatment of CNS disorders has also made remarkable strides with the introduction of many new drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and AD, among many other quantitatively and qualitatively important neuropsychiatric disorders.

Improvement in terms of clinical outcome, however, has fallen short of expectations, with up to one-third of patients continuing to experience clinical relapse or unacceptable medication-related side effects in spite of efforts to identify optimal treatment regimes with one or more drugs. Potential reasons for this historical setback might be: (1) that the molecular pathology of most CNS disorders is still poorly understood; (2) that drug targets are inappropriate, not fitting into the real etiology of the disease; (3) that most treatments are symptomatic but not antipathogenic; (4) that the genetic component of most CNS disorders is poorly defined; and (5) that the understanding of genome–drug interactions is very limited [7], [12].

The optimization of CNS therapeutics requires the establishment of new postulates regarding (1) the costs of medicines, (2) the assessment of protocols for multifactorial treatment in chronic disorders, (3) the implementation of novel therapeutics addressing causative factors, and (4) the establishment of pharmacogenomic strategies for drug development [12]. Personalized therapeutics based on individual genomic profiles implies the characterization of five types of gene clusters:

-

•

Genes associated with disease pathogenesis

-

•

Genes associated with the mechanism of action of drugs

-

•

Genes associated with drug metabolism (phase I and II reactions)

-

•

Genes associated with drug transporters

-

•

Pleiotropic genes involved in multifaceted cascades and metabolic reactions

27.3. Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease

More than 3000 genes distributed across the human genome have been screened for association with AD during the past 30 years [16]. In the Alzgene database [17] there are 695 genes potentially associated with AD, of which the top ten are (in decreasing order of importance): APOE (19q13.2), BIN1 (2q14), CLU (8p21–p12), ABCA7 (19p13.3), CR1 (1q32), PICALM (11q14), MS4A6A (11q12.1), CD33 (19q13.3), MS4A4E (11q12.2), and CD2AP (6p12). Potentially defective genes associated with AD represent about 1.39% (35,252.69 Kb) of the human genome, which is integrated by 36,505 genes (3,095,677.41 Kb). The highest number of AD-related defective genes concentrate on chromosomes 10 (5.41%; 7337.83 Kb), 21 (4.76%; 2289.15 Kb), 7 (1.62%; 2584.26 Kb), 2 (1.56%; 3799.67 Kb), 19 (1.45%; 854.54 Kb), 9 (1.42%; 2010.62 Kb), 15 (1.23%; 1264.4 Kb), 17 (1.19%; 970.16 Kb), 12 (1.17%; 1559.9 Kb), and 6 (1.15%; 1968.22 Kb), with the highest proportion (related to the total number of genes mapped on a single chromosome) located on chromosome 10 and the lowest on chromosome Y [18] (Figure 27.1 ).

Figure 27.1.

Distribution of AD-related genes in the human genome.

The genetic and epigenetic defects identified in AD can be classified into four major categories: Mendelian mutations; susceptibility SNP; mtDNA mutations; and epigenetic changes. Mendelian mutations affect genes directly linked to AD, including 32 mutations in the amyloid beta precursor protein (APP) gene (21q21)(AD1), 165 mutations in the presenilin 1 (PSEN1) gene (14q24.3)(AD3), and 12 mutations in the presenilin 2 (PSEN2) gene (1q31–q42) (AD4) [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. PSEN1 and PSEN2 are important determinants of γ-secretase activity responsible for proteolytic cleavage of APP and NOTCH receptor proteins. Mendelian mutations are very rare in AD (1:1000). Mutations in exons 16 and 17 of the APP gene appear with a frequency of 0.30% and 0.78%, respectively, in AD patients. Likewise, PSEN1, PSEN2, and microtubule-associated protein Tau (MAPT)(17q21.1) mutations are present in less than 2% of cases. Mutations in these genes confer specific phenotypic profiles to patients with dementia: amyloidogeneic pathology associated with APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations and tauopathy associated with MAPT mutations represent the two major pathogenic hypotheses for AD [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21].

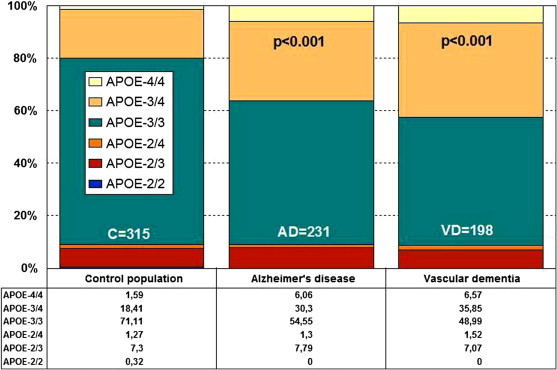

Multiple polymorphic risk variants can increase neuronal vulnerability to premature death (see Appendix A). Among these susceptibility genes, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene (19q13.2)(AD2) is the most prevalent as a risk factor for AD, especially in those subjects harboring the APOE-4 allele (Figure 27.2 ), whereas carriers of the APOE-2 allele might be protected against dementia. APOE-related pathogenic mechanisms are also associated with brain aging and with the neuropathological hallmarks of AD [16].

Figure 27.2.

Distribution and frequency of APOE genotypes in AD and vascular dementia.

Source: Adapted from Cacabelos[18].

27.4. Pathogenic Events

The dual amyloidogenic-tauopathic theory of AD has dominated the pathogenic universe of AD-related neurodegeneration (and divided the research community) for the past 50 years, nourished by the presence of APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and MAPT mutations in a very small number of cases with early-onset AD. Nevertheless, this theory does not explain AD pathogenesis in full, and consequently novel (or complementary) theories have been emerging recently and during the past decades. A summary of the pathogenic events in AD is given in the following sections.

27.4.1. Genomic Defects

As a complex polygenic/multifactorial disorder, in which hundreds of polymorphic variants of risk might be involved (Appendix A, Figure 27.1), AD fulfils the “golden rule” of complex disorders, according to which the larger the number of genetic defects distributed in the human genome, the earlier the onset of the disease and the poorer its therapeutic response to conventional treatments; conversely, the smaller the number of pathogenic SNPs, the later the onset of the disease and the better its therapeutic response to different pharmacological interventions [12], [16], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Genetic variation associated with different diseases interferes with microRNA-mediated regulation by creating, destroying, or modifying microRNA (miRNA) binding sites. miRNA-target variability is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the adult human brain which may influence gene expression in physiological and pathological conditions. AD-related SNPs interfere with miRNA gene regulation and affect AD susceptibility. Significant interactions include target SNPs present in seven genes related to AD prognosis with the miRNAs miR-214, -23a and -23b, -486-3p, -30e*, -143, -128, -27a and -27b, -324-5p, and -422a. The dysregulated miRNA network contributes to aberrant gene expression in AD [29], [30], [31].

27.4.2. Epigenetic Phenomena

Epigenetic factors have emerged as important mediators of development and aging, gene–gene and gene–environmental interactions, and the pathophysiology of complex disorders. Major epigenetic mechanisms (DNA methylation, histone modifications and chromatin remodeling, and noncoding RNA regulation) may contribute to AD pathology [30], [31].

27.4.3. Cerebrovascular Dysfunction

Vascular and metabolic dysfunctions are key components in AD pathology throughout the course of disease. Although common denominators between vascular and metabolic dysfunction are oxidative stress and Aβ [32], genetic factors and cardiovascular risk factors may also account for the cerebrovascular damage present in AD [33]. Inherited polymorphisms of the vascular susceptibility gene Ninjurin2 (NINJ2) are associated with AD risk [34]. Endothelial dysfunction has been implicated as a crucial event in the development of AD.

Breakdown of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) as a result of disruption of tight junctions and transporters leads to increased leukocyte transmigration and is an early event in the pathology of many CNS disorders. BBB breakdown leads to neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, with mitochondrial dysfunction. The high concentration of mitochondria in cerebrovascular endothelial cells might account for the sensitivity of the BBB to oxidant stressors [35], [36].

Chronic brain hypoperfusion may be sufficient to induce premature neuronal death and dementia in vulnerable subjects [16], [23], [24], [25], [37], [38], [39]. APOE-related changes in cortical oxygenation and hemoglobin consumption are evident, as revealed by brain optical topography analysis, and reflect that APOE-4 carriers exhibit deficient brain hemodynamics and a poorer panneocortical oxygenation than do APOE-3 or APOE-2 carriers [18]. Hypoperfusion in frontal, parietal, and temporal regions is a common finding in AD. White matter hyperintensities (WMH) correlate with age and with disease severity [40].

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) accounts for the majority of primary lobal intracerebral hemorrhages (ICH) among the elderly, and represents the cause of 20% of spontaneous ICHs in patients over 70 years of age. The basis for this disease process is the deposition and formation of eventually destructive amyloid plaques in the walls of brain vessels, predominantly arterial but not excluding venules and capillaries. CAA and CAA-associated microhemorrhages may also participate in the pathogenesis of AD [41]. Aβ deposition in asymptomatic elderly individuals is associated with lobar MH (LMH).

LMH is present in 30.8% of AD, 35.7% of MCI, and 19.1% of controls [42]. Neurovascular dysfunction in AD leads to reduced clearance across the BBB and accumulation of neurotoxic Aβ peptides in the brain. The ABC transport protein P-glycoprotein (P-gp, ABCB1) is involved in the export of Aβ from the brain into the blood. P-gp, LRP1, and RAGE mRNA expression is reduced in mice treated with Aβ1–42. In addition to the age-related decrease in P-gp expression, Aβ1–42 itself downregulates the expression of P-gp and other Aβ transporters, which could exacerbate the intracerebral accumulation of Aβ and thereby accelerate neurodegeneration in AD and cerebral β-amyloid angiopathy [43].

27.4.4. Phenotypic Expression of Amyloid Deposits and Neurofibrillary Tangles

β-Amyloid deposits in senile and neuritic plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) are extracellular and intracellular expressions, respectively, of the AD neuropathological phenotype, together with selective neuronal loss in hippocampal and neocortical regions. Aβ plaque in the brain is the primary (postmortem) diagnostic criterion of AD. The main component of senile plaques is Aβ, a 39–43 amino acid peptide, generated by the proteolytic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the action of beta- and gamma-secretases. Aβ is neurotoxic, and this neurotoxicity is related to its aggregation state [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21].

27.4.5. Neuronal Apoptosis

Neuronal loss is a pathognomonic finding in AD and the final common path of multiple pathogenic mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration in dementia. Atrophy of the medial temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus, is considered to be AD’s most predictive structural brain biomarker. The medial and posterior parts of the parietal lobe seem to be preferentially affected, compared to the other parietal lobe parts [18].

27.4.6. Neurotransmitter Deficits

An imbalance of different neurotransmitters (glutamate, acetylcholine, noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, and some neuropeptides) has been proposed as the neurobiological basis of behavioral symptoms in AD. Altered reuptake of neurotransmitters by vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs), excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs), the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT), or the dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) are involved in the neurotransmission imbalance in AD. Protein and mRNA levels of VGLUTs, EAAT1-3, VAChT, and SERT are reduced in the disease [44].

27.4.7. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative damage is a classic pathogenic mechanism of neurodegeneration [36], [45]. It is greater in brain tissue from patients with AD than age-matched controls. Tayler et al. [46] studied the timing of this damage in relation to other pathogenic AD processes. Antioxidant capacity is elevated in AD and directly related to disease severity as indicated by the Braak tangle stage and the amount of insoluble Aβ. Accumulation of Aβ has been shown in brain mitochondria of AD patients and in AD transgenic mouse models. The presence of Aβ in mitochondria leads to free radical generation and neuronal stress.

A novel mitochondrial Aβ-degrading enzyme, presequence protease (Pre), has been identified in the mitochondrial matrix. hPreP activity is decreased in AD human brains and in the mitochondrial matrix of AD transgenic mouse brains (TgmAβPP and TgmAβPP/ABAD). Mitochondrial fractions isolated from AD brains and TgmAβPP mice have higher levels of 4-hydroxynonenal, an oxidative product. Cytochrome c oxidase activity is significantly reduced in the AD mitochondria. Decreased PreP proteolytic activity, possibly due to enhanced ROS production, may contribute to Aβ accumulation in mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial toxicity and neuronal death in AD [47].

27.4.8. Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism Dysfunction

Cholesterol seems to be intimately linked with the generation of amyloid plaques, which are central to AD pathogenesis. APOE variants are determinants in cholesterol metabolism and diverse forms of dyslipoproteinemia [12], [48]. Cholesterol protects the Aβ-induced neuronal membrane disruption and inhibits beta-sheet formation of Aβ on the lipid bilayer [49]. Jones et al. [50] found a significant over-representation of association signals in pathways related to cholesterol metabolism and the immune response in both of the two largest genome-wide association studies for LOAD.

27.4.9. Neuroinflammation and Immunopathology

Several genes associated with immune regulation and inflammation show polymorphic variants of risk in AD, and abnormal levels of diverse cytokins have been reported in the brain, CSF, and plasma of AD patients [16], [23]. The activation of inflammatory cascades has been consistently demonstrated in AD pathophysiology, in which reactive microglia are associated with Aβ deposits and clearance. Resident microglia fail to trigger an effective phagocytic response to clear Aβ deposits, although they mainly exist in an “activated” state. Oligomeric Aβ (oAβ) can induce more potent neurotoxicity when compared with fibrillar Aβ (fAβ). Aβ(1–42) fibrils, not Aβ(1–42) oligomers, increase microglial phagocytosis [51]. Among several putative neuroinflammatory mechanisms, the TNF-α signaling system has a central role in this process. In AD, TNF-α levels are altered in serum and CSF. The abnormal production of inflammatory factors may accompany the progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia. Abnormal activation of the TNF-α signaling system, represented by increased expression of sTNFR1, is associated with a higher risk of progression from MCI to AD [52].

27.4.10. Neurotoxic Factors

Old and new theories suggest that different toxic agents, from metals (e.g., aluminium, copper, zinc, iron) to biotoxins and pesticides, might contribute to neurodegeneration. Dysfunctional homeostasis of transition metals is believed to play a role in AD pathogenesis [18].

27.4.11. Other Players

Many novel pathogenic mechanisms potentially involved in AD neurodegeneration have been proposed in recent times. Moreover, there has been a revival of some old hypotheses. Examples of pathogenic players in AD, other than those just discussed, include the Ca2+ hypothesis, insulin resistance, NGF imbalance, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and their receptors (RAGE), the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp), c-Abl tyrosine kinase, post-transcriptional protein alterations that compromise the proteasome system and the chaperone machinery (HSPB8–BAG3), autophagy as a novel Aβ-generating pathway, hypocretin (orexin), cathepsin B, Nogo receptor proteins, adipocytokines and CD34+ progenitor cells, CD147, impairment of synaptic plasticity (PSD-95), anomalies in neuronal cell division and apoptosis, stem cell factor (SCF), telomere shortening, deficiency in repair of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage, and microDNAs [18].

27.5. Biomarkers and Comorbidity

AD’s phenotypic features represent the biomarkers to be used as diagnostic predictors and the expression of pathogenic events to be modified with an effective therapeutic intervention. Important differences have been found in the AD population (as compared with healthy subjects) in different biological parameters, including blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, transaminase activity, hematological parameters, metabolic factors, thyroid function, brain hemodynamic parameters, and brain mapping activity [7], [23], [24], [25], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

These clinical differences are clear signs of comorbidity rather than typical features of AD. Blood pressure values, glucose levels, and cholesterol levels are higher in AD than in healthy elderly subjects. Approximately 20% of AD patients are hypertensive, 25% are diabetics, 50% are hypercholesterolemic, and 23% are hypertriglyceridemic. More than 25% of patients exhibit high GGT activity, 5–10% show anemic conditions, 30–50% show an abnormal cerebrovascular function characterized by poor brain perfusion, and more than 60% have an abnormal electroencephalographic pattern, especially in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, as revealed by quantitative EEG (qEEG) or computerized mapping [7], [12], [23], [54]. Significant differences are currently seen between females and males, indicating the effect of gender on the phenotypic expression of the disease. In fact, the prevalence of dementia is 10–15% higher in females than in males from 65–85 years of age. All of these parameters are highly relevant when treating AD patients, because some of them reflect a concomitant pathology that also needs therapeutic consideration.

AD biomarkers can be differentiated into several categories: (1) neuropathological markers; (2) structural and functional neuroimaging markers; (3) neurophysiological markers (EEG, qEEG, brain mapping); (4) biochemical markers in body fluids (e.g., blood, urine, saliva, CSF); and (5) genomic markers (structural and functional genomics, proteomics, metabolomics).

27.5.1. Neuropathology

Plaques and tangles in the hippocampus and cortex are still considered the seminal findings in AD neuropathology and are the conventional means of establishing the boundary between amyloidopathies and tauopathies; however, both phenotypic markers are also present in normal brains, in more than 60% of cases with traumatic brain injury, and in many other brain disorders [60].

27.5.2. Structural and Functional Neuroimaging

Structural and functional neuroimaging techniques (MRI, fMRI, PET, SPECT) are essential tools in the diagnosis of dementia, although the specificity of visual observations in degenerative forms of dementia is of doubtful value. Nevertheless, these procedures are irreplaceable for a differential diagnosis. There is a characteristic regional impairment in AD that involves mainly the temporo–parietal association cortices, the mesial temporal structures, and, to a more variable degree, the frontal association cortex. This pattern of functional impairment can provide a biomarker for diagnosis of AD and other neurodegenerative dementias at the clinical stage of mild cognitive impairment, and for monitoring its progression. Healthy young APOE ɛ4 carriers have smaller hippocampal volumes than APOE ɛ2 carriers.

The difference in hippocampal morphology is cognitively/clinically silent in young adulthood, but can render APOE ɛ4 carriers more prone to the later development of AD, possibly because of lower reserve cognitive capacity [61]. LOAD patients exhibit a selective parahippocampal white matter (WM) loss, while EOAD patients experience a more widespread pattern of posterior WM atrophy. The distinct regional distribution of WM atrophy reflects the topography of gray matter (GM) loss. ApoE ɛ4 status is associated with a greater parahippocampal WM loss in AD. The greater WM atrophy in EOAD than in LOAD fits with the evidence that EOAD is a more aggressive form of the disease [62]. FDG-PET is quantitatively more accurate than perfusion SPECT.

Regional metabolic and blood flow changes are closely related to clinical symptoms, and most areas involved in these changes also develop significant cortical atrophy. FDG-PET is complementary to amyloid PET, which targets a molecular marker that does not have a close relation to current symptoms. FDG-PET is expected to play an increasing role in diagnosing patients at an early stage of AD and in clinical trials of drugs aimed at preventing or delaying the onset of dementia [63]. Functional neuroimaging biomarkers are becoming popular, with the introduction of novel tracers for brain amyloid deposits. Amyloid deposition causes severe damage to neurons many years before onset of dementia via a cascade of several downstream effects.

Positron emission tomography (PET) tracers for amyloid plaque are desirable for early diagnosis of AD, particularly to enable preventative treatment once effective therapeutics is available. The amyloid imaging tracers flutemetamol, florbetapir, and florbetaben labeled with 18F have been developed for PET. These tracers are currently undergoing formal clinical trials to establish whether they can be used to accurately image fibrillary amyloid, and to distinguish patients with AD from normal controls and those with other diseases that cause dementia [63].

27.5.3. Neurophysiology

There is a renewed interest in the use of computerized brain mapping as a diagnostic aid and as a monitoring tool in AD [64]. Electroencephalography (EEG) studies in AD show an attenuation of average power within the alpha band (7.5–13 Hz) and an increase in power in the theta band (4–7 Hz) [65]. APOE genotypes influence brain bioelectrical activity in AD. In general, APOE-4 carriers tend to exhibit a slower EEG pattern from early stages [16], [18], [66].

27.5.4. Biochemistry of Body Fluids

Other biomarkers of potential interest include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and peripheral levels of Aβ42, protein tau, histamine, interleukins, and some other novel candidate markers such as chitinase 3-like 1 (CHI3L1) protein [7], [16], [25], [67], [68], [69]. The concentration of the 42-amino-acid form of Aβ (Aβ1–42) is reduced in the CSF of AD patients, which is believed to reflect the AD pathology, with plaques in the brain acting as sinks. Novel C-truncated forms of Aβ (Aβ1–14, Aβ1–15, and Aβ1–16) were identified in human CSF. The presence of these small peptides is consistent with a catabolic amyloid precursor protein cleavage pathway by β- followed by α-secretase. Aβ1–14, Aβ1–15, and Aβ1–16 increase dose-dependently in response to γ-secretase inhibitor treatment, while Aβ1–42 levels are unchanged [70].

Kester et al. [71] investigated change over time in CSF levels of amyloid-beta 40 and 42 (Aβ40 and Aβ42), total tau (tau), tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (ptau-181), isoprostane, neurofilaments heavy (NfH) and neurofilaments light (NfL). Aβ42, tau, and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 differentiated between diagnosis groups, whereas isoprostane, NfH, and NfL did not. In contrast, effects of follow-up time were found only for nonspecific CSF biomarkers: levels of NfL decreased, and levels of isoprostane, Aβ40, and tau increased over time. An increase in isoprostane was associated with progression of mild cognitive impairment in AD and with cognitive decline. Contrary to AD-specific markers, nonspecific CSF biomarkers show change over time, which potentially can be used to monitor disease progression in AD.

27.5.5. Genomics and Proteomics

Structural markers are represented by SNPs in genes associated with AD, polygenic cluster analysis, and genome-wide studies (GWSs). Functional markers attempt to correlate genetic defects with specific phenotypes (genotype–phenotype correlations). In proteomic studies, several candidate CSF protein biomarkers have been assessed in neuropathologically confirmed AD, nondemented (ND) elderly controls, and non-AD dementias (NADD). Markers selected included apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoA1), hemopexin (HPX), transthyretin (TTR), pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, total tau, phosphorylated tau, α-1 acid glycoprotein (A1GP), haptoglobin, zinc α-2 glycoprotein (Z2GP), and apolipoprotein E (ApoE). Concentrations of Aβ1–42, ApoA1, A1GP, ApoE, HPX, and Z2GP differed significantly among AD, ND, and NADD subjects. The CSF concentrations of these three markers distinguished AD from ND subjects with 84% sensitivity and 72% specificity, with 78% of subjects correctly classified.

By comparison, Aβ1–42 alone gave 79% sensitivity and 61% specificity, with 68% of subjects correctly classified. For the diagnostic discrimination of AD from NADD, only the concentration of Aβ1–42 was significantly related to diagnosis, with a sensitivity of 58% and a specificity of 86% [72]. Carrying the APOE-ɛ4 allele was associated with a significant decrease in CSF Aβ1–42 concentrations in middle-aged and older subjects. In AD, Aβ1–42 levels are significantly lower in APOEɛ4 carriers compared to noncarriers. These findings demonstrate significant age effects on CSF Aβ1–42 and pTau181 across the lifespan, and also suggest that a decrease in Aβ1–42, but an increase in pTau181 CSF levels, is accelerated by the APOEɛ4 genotype in middle-aged and older adults with normal cognition [73].

Han et al. [74] carried out a GWAS to better define the genetic backgrounds of normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and AD in terms of changes in CSF levels of Aβ1–42, T-tau, and P-tau181P. CSF Aβ1–42 levels decreased with APOE gene dose for each subject group. T-tau levels tended to be higher among AD cases than among normal subjects. CYP19A1 “aromatase” (rs2899472), NCAM2, and multiple SNPs located on chromosome 10 near the ARL5B gene demonstrated the strongest associations with Aβ1–42 in normal subjects.

Two genes found to be near the top SNPs, CYP19A1 (rs2899472) and NCAM2 (rs1022442), have been reported as genetic factors related to the progression of AD. In AD subjects, APOE ɛ2/ɛ3 and ɛ2/ɛ4 genotypes were associated with elevated T-tau levels, and the ɛ4/ɛ4 genotype was associated with elevated T-tau and P-tau181P levels. Blood-based markers reflecting core pathological features of AD in presymptomatic individuals are likely to accelerate the development of disease-modifying treatments.

Thambisetty et al. [75] performed a proteomic analysis to discover plasma proteins associated with brain Aβ burden in nondemented older individuals. A panel of 18 2DGE plasma protein spots effectively discriminated between individuals with high and low brain Aβ. Mass spectrometry identified these proteins, many of which have established roles in Aβ clearance, including a strong signal from ApoE. A strong association was observed between plasma ApoE concentration, and Aβ burden in the medial temporal lobe. Targeted voxel-based analysis localized this association to the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. APOE ɛ4 carriers also showed greater Aβ levels in several brain regions relative to ɛ4 noncarriers. Both peripheral concentration of the ApoE protein and the APOE genotype may be related to early neuropathological changes in brain regions vulnerable to AD pathology even in the nondemented elderly.

27.6. Therapeutic Strategies

Modern therapeutic strategies in AD are aimed at interfering with the main pathogenic mechanisms potentially involved in AD [7], [12], [16], [18], [23], [24], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59] (Box 27.1). Starting in the early 1990s, the neuropharmacology of AD was dominated by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, represented by tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine [76], [77], [78]. Memantine, a partial NMDA antagonist, was introduced in the 2000s for the treatment of severe dementia [79]; and the first clinical trials with immunotherapy, to reduce amyloid burden in senile plaques, were withdrawn due to severe ADRs [80], [81]. After the initial promise of β- and γ-secretase inhibitors [82], [83] and novel vaccines [84], [85] devoid of severe side effects, during the past few years no relevant drug candidates have dazzled the scientific community with their capacity to halt disease progression; however, a large number of novel therapeutic strategies for the pharmacological treatment of AD have been postulated, with some apparent effects in preclinical studies (see Box 27.1).

Box 27.1. Experimental Strategies for the Pharmacological Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease.

New cholinesterase inhibitors

Cholinergic receptor agonists

Monoamine regulators

Diverse natural compounds derived from vegetal sources:

Alkaloids from the calabar bean (Physostigma venenosum)

Huperzine A from Huperzia serrata

Galantamine from the snowdrop Galanthus woronowii

Cannabinoids (cannabidiol) from Cannabis sativa

Saffron (Crocus sativus)

Ginseng (Panax species)

Sage (Salvia species)

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis)

Polygala tenuifolia

Nicotine from Nicotiana species

Grape seed polyphenolic extracts

Fuzhisan, a Chinese herbal medicine

Resveratrol

Xanthoceraside

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Linarin from Mentha arvensis and Buddleja davidii

Carotenoids (e.g., retinoic acid, all-trans retinoic acid, lycopene and β-carotene)

Curcumin from the rhizome of Curcuma longa

Decursinol from the roots of Angelica gigas

Bacopa monniera LINN (Syn. Brahmi)

Olive oil

Phytoestrogens

Walnut extract

Erigeron annuus leaf extracts

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

Luteolin

The brown algae (Ecklonia cava)

Gami-Chunghyuldan (standardized multiherbal medicinal formula)

Punica granatum extracts

Plants of different origin:

Yizhi Jiannao

Drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera)

Ginkgo/Maidenhair tree (Ginkgo biloba)

Sicklepod (Cassia obtisufolia)

Sal Leaved Desmodium (Desmodium gangeticum)

Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis)

Garden sage, common sage (Salvia officinalis)

Immunotherapy and treatment options for tauopathies:

Tau kinase inhibitors

2-Aminothiazoles

Phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibitors

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNKs) inhibitors

p38 MAP kinase inhibitors (CNI-1493)

Harmine (β-carboline alkaloid)

Immunotherapy and Aβ breakers for AD-related amyloidopathy:

Active and passive immunization

Secretase inhibitors (β- and γ-)

Neostatins

Neurosteroids

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

Protein phosphatase methylesterase-1 inhibitors

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

mTOR inhibitors

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists

P-glycoprotein regulators

Nuclear receptor agonists

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) regulators

Histamine H3 receptor inverse agonists

Estrogens

Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibitors

Chaperones (small heat shock proteins (sHSPs); Hsp90 inhibitors and HSP inducers)

microRNAs (miRNAs) and gene silencing (RNA interference)(RNAi)

Miscellaneous strategies:

Sodium fullerenolate

Glucagon-like peptide -1 (GLP-1)

Chemokines

Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2)

Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α)

Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors

Bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP-9)

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)/AMD3100 (CXCR4 antagonist)

Vitamins (A, B, C, D)

ω-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs)

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6 n-3)

Sphingosylphosphorylcholine

Citidine-5-diphosphocholine (CDP-choline)

Cathepsin B inhibitors

Pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide

NAP (Davunetide)

Transcription factor specificity protein 1 (Sp1) inhibitors (tolfenamic acid)

- TNF inhibitors:

- 2-(2,6-Dioxopiperidin-3-yl)phthalimidine EM-12 dithiocarbamates

- N-substituted 3-(Phthalimidinp-2-yl)-2,6-dioxopiperidines

- 3-substituted 2,6-Dioxopiperidines

Pyrrolo[3,2-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine (SEN1176)

Latrepirdine

Leucettines

Dihydropyridines (inhibitors of L-type calcium channels)

Brain-penetrating angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

NADPH oxidase inhibitors (Apocynin)

Heterocyclic indazole derivatives (inhibitors of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible-kinase 1 [SGK1])

IgG-single-chain Fv fusion proteins

27.6.1. Immunotherapy

There are two main modalities of immunotherapy for AD: (1) passive immunotherapy, with the administration of monoclonal Aβ-specific antibodies [86]; and (2) active immunization with the Aβ42 antigen [87], [88] or Aβ-conjugated synthetic fragments bound to a carrier protein, thus avoiding potential problems associated with mounting a T-cell response directly against Aβ [89]. A new approach—delivering Aβ42 in a novel immunogen-adjuvant manner consisting of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)-containing liposomes, administered to APP/PS1 transgenic mice before and after the detection of AD-like pathology in the brain—has recently been developed [85].

The results from this novel vaccine (EB101) indicate that active immunization significantly prevents and reverses the progression of AD-like pathology and also clears prototypical neuropathological hallmarks in transgenic mice. This new approach strongly induces T-cell, B-cell, and microglial immune response activation, avoiding the Th1 inflammatory reaction [90].

The rationale for amyloid immunotherapy in AD [91] is based on the following assumptions:

-

•

β-amyloid plaques and their aggregated, proto-fibrillar, and oligomeric precursors contain immunologic neo-epitopes that are absent from the full-length amyloid precursor protein (APP), as well as from its soluble proteolytic derivatives restricted to brain tissue; consequently, β-amyloid-based immunotherapies designed to selectively target pathologic neo-epitopes present on Aβ oligomers, protofibrils, or fibrils should not cause autoimmune disease in unaffected tissues throughout the organism

-

•

β-amyloid buildup precedes neurodegeneration and functional loss, and either the prevention of its formation or its removal can be expected to result in the slowing or the prevention of neurodegeneration

-

•

β-amyloid can cause the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in vivo and in vitro. The removal of β-amyloid, or the prevention of its buildup, has the potential not only to correct β-amyloid-related toxicity, but also to prevent the formation of neurofibrillary tangles

-

•

Conformational changes of endogenously occurring proteins and the formation of insoluble aggregates are commonly associated with neurodegeneration and brain disease, so the removal or prevention of these pathologic protein aggregates is also a therapeutic goal in the principle of immunotherapy

-

•

Immunotherapy works in experimental animals and in initial clinical trials: both active immunization and passive antibody transfer consistently reduce brain β-amyloid load, improve β-amyloid-related memory impairments, and protect neurons against degeneration in many independent experiments using different mouse models and primates [90]

Since Aβ immunotherapy has a limited clearance effect of tau aggregates in dystrophic neurites, the development of an alternative therapy that directly targets pathological tau has become crucial. Increased levels of tau oligomers have been observed in the early stage of AD, prior to the detection of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) formed by aggregation and accumulation of the microtubule-associated protein tau [92]. Several approaches have been taken to treat AD by targeting tau, such as the following:

-

1.

The inhibition of tau hyperphosphorylation, by a kinase inhibitor of soluble aggregated tau formation, which also prevents related motor deficits [93].

-

2.

Activation of the proteolytic pathway, by the degrading action of calpain [94] and puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase [95].

-

3.

The stabilization of microtubules, treating tauopathies by functionally binding and stabilizing microtubules with mt-binding protein tau [96] and paclitaxel, a drug proven effective in restoring affected axonal transport and motor impairments [97].

-

4.

Tau clearance by immunotherapy in this case, the tau active vaccination uses phosphorylated antigens of tau fragments associated with neurofibrillary tangles [98] that results in an efficient reduction of both soluble and insoluble tau active fragments, reducing phosphorylated NFTs in AD-like mouse brains.

Preclinical studies have shown clear evidence that Aβ immunization therapy provides protection and reverses the pathological effects of AD in transgenic mouse models [99]. This strategy seems to improve cognition performance [100] after Aβ42 immunization, in addition to causing an effective reduction in Aβ pathology. A recent immunization study has proven that a fragment of the Aβ peptide bound to polylysines activates the immune response that diminishes AD-like pathology in APP transgenic mice. This result reinforces the notion that the immune-conjugate approach is an effective means of Aβ immunotherapy, and also that the entire Aβ peptide is not necessary for its efficacy. It is in accordance with the hypothesis that specific antibodies directed against the amino-terminal and/or central region of the amyloid peptide provide beneficial protection against amyloid pathology. Passive immunization studies have also been conducted with promising experimental results, showing that a humoral response alone, without Aβ cellular response, is sufficient to reduce the β-amyloid burden and reverse memory deficits [101].

Among the drugs and vaccines currently under development to treat the pathological effects of AD, the most promising are bapineuzumab, solanezumab, CAD106, and EB101. Solanezumab is a monoclonal antibody raised against Aβ13–28 that recognizes an epitope in the core of the amyloid peptide, binding selectively to soluble Aβ and with low affinity for the fibrillar Aβ form [102]. Thus, it presents fewer adverse events than does bapineuzumab, which binds to Aβ amyloid plaques more strongly than soluble Aβ [103]. There are a few other monoclonal antibodies against Aβ that have properties different from those of bapineuzumab, such as PF-04360365, which specifically targets the free carboxy-terminus of Aβ1–40, MABT5102A, which binds with equally high affinity to Aβ monomers, oligomers, and fibrils, and GSK933776A, which targets the N-terminus of Aβ.

Specific anti-Aβ antibodies are present in pooled preparations of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg or IGIV), which has already been approved by the FDA for the treatment of a variety of neurological conditions. Current results from these studies have shown that IVIg treatment may also be an efficacious alternative approach in the treatment of AD neuropathologies [90], [104].

Avoiding both the strong Th1 effects of the QS-21 adjuvant and the T-cell epitopes at the C-terminus of Aβ, CAD106 consists of a short N-terminal fragment of Aβ attached to a virus-like particle, with no additional adjuvant [105]. This therapeutic agent is currently in phase II trials. Affiris is testing two short 6-amino-peptides (AD01, AD02), administered with aluminum hydroxide as adjuvant, that mimic the free N-terminus of Aβ and therefore cause cross-reactivity with the native peptide in phase I trials [106]. In terms of prevention and therapeutic treatment, the EB101 vaccine showed for the first time the effectiveness of combining a liposomal immunogen-adjuvant with an Aβ antigen to induce an effective immunological response combined with an anti-inflammatory effect in preclinical studies using APP/PS1 transgenic mice [85], [90].

The EB101 vaccine immunization process has shown a marked positive effect as a preventive and therapeutic treatment, reducing amyloidosis-induced inflammation as an effective Th2 immunomodulator. Moreover, this vaccine proved to stimulate innate immunity and enable effective phagocytosis to clear amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles, which are among the major hallmarks of AD-like neuropathology observed. A few other vaccines are currently under development, and recent studies have opened up new perspectives in the immunization approach to AD pathology; in particular, gene-gun-mediated genetic immunization with the Aβ42 gene [107] shows that self-tolerance can be broken in order to produce a humoral response to the Aβ42 peptide with minimal cellular response.

27.7. Pharmacogenomics

AD patients may take 6–12 different drugs per day for the treatment of dementia-related symptoms, including memory decline (conventional antidementia drugs, neuroprotectants), behavioral changes (antidepressants, neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics), and functional decline. Such drugs may also be taken for the treatment of concomitant pathologies (epilepsy, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disorders, parkinsonism, hypertension, dyslipidemia, anemia, arthrosis, etc). The co-administration of several drugs may cause side effects and ADRs in more than 60% of AD patients, who in 2–10% of cases require hospitalization. In more than 20% of patients, behavioral deterioration and psychomotor function can be severely altered by polypharmacy. The principal causes of these iatrogenic effects are (1) the inappropriate combination of drugs, and (2) the genomic background of the patient, which is responsible for his/her pharmacogenomic outcome.

Pharmacogenomics account for 30–90% of the variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The genes involved in the pharmacogenomic response to drugs in AD fall into five major categories:

-

•

Genes associated with AD pathogenesis and neurodegeneration (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, MAPT, PRNP, APOE, and others)

-

•

Genes associated with the mechanism of action of drugs (enzymes, receptors, transmitters, messengers)

-

•

Genes associated with drug metabolism (phase I (CYPs) and phase II reactions (UGTs, NATs))

-

•

Genes associated with drug transporters (ABCs, SLCs)

-

•

Pleiotropic genes involved in multifaceted cascades and metabolic reactions (APOs, ILs, MTHFR, ACE, AGT, NOS, etc) [18] (Figure 27.1)

27.7.1. Pathogenic Genes

In more than 100 clinical trials for dementia, APOE has been used as the only gene of reference for the pharmacogenomics of AD [7], [12], [15], [16], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]. Several studies indicate that the presence of the APOE-4 allele differentially affects the quality and extent of drug responsiveness in AD patients treated with cholinergic enhancers (tacrine, donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine), neuroprotective compounds (nootropics), endogenous nucleotides (CDP-choline), immunotrophins (anapsos), neurotrophic factors (cerebrolysin), rosiglitazone, or combination therapies [108], [109], [110]; however, controversial results are frequently found that are due to methodological problems, study design, and patient recruitment in clinical trials.

The major conclusion in most studies is that APOE-4 carriers are the worst responders to conventional treatments [7], [12], [15], [16], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]. When APOE and CYP2D6 genotypes are integrated in bigenic clusters and the APOE+CYP2D6-related therapeutic response to a combination therapy is analyzed in AD patients, it becomes clear that the presence of the APOE-4/4 genotype is able to convert pure CYP2D6*1/*1 extensive metabolizers (EMs) into full poor responders to conventional treatments, indicating the existence of a powerful influence of the APOE-4 homozygous genotype on the drug-metabolizing capacity of pure CYP2D6 EMs. In addition, a clear accumulation of APOE-4/4 genotypes is observed among CYP2D6 poor (PMs) and ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs) [12].

27.7.2. Genes Involved in the Mechanism of Action of CNS Drugs

Most genes associated with the mechanism of action of CNS drugs encode receptors, enzymes, and neurotransmitters on which psychotropic drugs act as ligands (agonists, antagonists), enzyme modulators (substrates, inhibitors, inducers), or neurotransmitter regulators (releasers, reuptake inhibitors) [111]. In the case of conventional antidementia drugs, tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine are cholinesterase inhibitors, and memantine is a partial NMDA antagonist (Table 27.1 ).

Table 27.1.

Pharmacogenomic Profile of Antidementia Drugs

| Donepezil | |

|---|---|

| Category | Antidementia agent/cholinesterase inhibitor |

| Mechanism | Centrally active, reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; increases acetylcholine available for synaptic transmission in CNS |

| Genes | |

| Pathogenic | APOE, CHAT |

| Mechanistic | CHAT, ACHE, BCHE |

| Metabolism: substrate | CYP2D6 (major), CYP3A4 (major), UGTs, ACHE |

| Metabolism: inhibitor | ACHE, BCHE |

| Transporter | ABCB1 |

| Galantamine | |

| Category | Antidementia agent/cholinesterase inhibitor |

| Mechanism | Reversible and competitive acetylcholinesterase inhibition leading to increased concentration of acetylcholine at cholinergic synapses; modulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; may increase glutamate and serotonin levels |

| Genes | |

| Mechanistic | APOE, APP |

| Pathogenic | ACHE, BCHE, CHRNA4, CHRNA7, CHRNB2 |

| Metabolism: substrate | CYP2D6 (major), CYP3A4 (major), UGT1A1 |

| Metabolism: inhibitor | ACHE, BCHE |

| Memantine | |

| Category | Antidementia Drug; N-methyl-d-aspartate Receptor Antagonist |

| Mechanism | Binds preferentially to NMDA receptor-operated cation channels; may act by blocking glutamate actions, mediated in part by NMDA receptors. Antagonists: GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN3A, HTR3A, CHRFAM7A |

| Genes | |

| Pathogenic | APOE, PSEN1, MAPT |

| Mechanistic | GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN3A, HTR3A, CHRFAM7A |

| Metabolism: inhibitor | CYP1A2 (weak), CYP2A6 (weak), CYP2B6 (strong), CYP2C9 (weak), CYP2C19 (weak), CYP2D6 (strong), CYP2E1 (weak), CYP3A4 (weak) |

| Pleiotropic | APOE, MAPT, MT-TK, PSEN1 |

| Rivastigmine | |

| Category | Antidementia Agent/Cholinesterase Inhibitor |

| Mechanism | Increases acetylcholine in CNS through reversible inhibition of its hydrolysis by cholinesterase |

| Genes | |

| Pathogenic | APOE, APP, CHAT |

| Mechanistic | ACHE, BCHE, CHAT, CHRNA4, CHRNB2 |

| Metabolism: inhibitor | ACHE, BCHE |

| Pleiotropic | APOE, MAPT |

| Tacrine | |

| Category | Antidementia agent/cholinesterase inhibitor |

| Mechanism | Elevates acetylcholine in cerebral cortex by slowing degradation of acetylcholine |

| Genes | |

| Pathogenic | APOE |

| Mechanistic | ACHE, BCHE, CHRNA4, CHRNB2 |

| Metabolism: substrate | CYP1A2 (major), CYP2D6 (minor), CYP3A4 (major) |

| Metabolism: inhibitor | ACHE, BCHE, CYP1A2 (weak) |

| Transporter | SCN1A |

| Pleiotropic | APOE, MTHFR, CES1, LEPR, GSTM1, GSTT1 |

Source: Cacabelos [113].

27.7.3. Genes Involved in Drug Metabolism

Drug metabolism includes phase I reactions (i.e., oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis) and phase II conjugation reactions (i.e., acetylation, glucuronidation, sulphation, methylation) (Table 27.2 ). The principal enzymes with polymorphic variants involved in phase I reactions are the following: cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP3A4/5/7, CYP2E1, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2C8, CYP2B6, CYP2A6, CYP1B1, CYP1A1/2), epoxide hydrolase, esterases, NQO1 (NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase), DPD (dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase), ADH (alcohol dehydrogenase), and ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase). The major enzymes involved in phase II reactions include UGTs (uridine 5′-triphosphate glucuronosyl transferases), TPMT (thiopurine methyltransferase), COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), HMT (histamine methyl-transferase), STs (sulfotransferases), GST-A (glutathione S-transferase A), GST-P, GST-T, GST-M, NAT1 (N-acetyl transferase 1), NAT2, and others (Table 27.2).

Table 27.2.

Drug Metabolism-Related Genes

| Phase I Enzymes | |

|---|---|

| Alcohol dehydrogenases | ADH1A, ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, ADH5, ADH6, ADH7, ADHFE1 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenases | ALDH1A1, ALDH1A2, ALDH1A3, ALDH1B1, ALDH2, ALDH3A1, ALDH3A2, ALDH3B1, ALDH3B2, ALDH4A1, ALDH5A1, ALDH6A1, ALDH7A1, ALDH8A1, ALDH9A1, AOX1 |

| Aldo-keto reductases | AKR1A1, AKR1B1, AKR1C1, AKR1D1 |

| Amine oxidases | MAOA, MAOB, SMOX |

| Carbonyl reductases | CBR1, CBR3, CBR4 |

| Cytidine deaminase | CDA |

| Cytochrome P450 family | CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, CYP2B6, CYP2C18, CYP2C19, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2D7P1, CYP2E1, CYP2F1, CYP2J2, CYP2R1, CYP2S1, CYP2W1, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, CYP3A43, CYP4A11, CYP4A22, CYP4B1, CYP4F2, CYP4F3, CYP4F8, CYP4F11, CYP4F12, CYP4Z1, CYP7A1, CYP7B1, CYP8B1, CYP11A1, CYP11B1, CYP11B2, CYP17A1, CYP19A1, CYP20A1, CYP21A2, CYP24A1, CYP26A1, CYP26B1, CYP26C1, CYP27A1, CYP27B1, CYP39A1, CYP46A1, CYP51A1, POR, TBXAS1 |

| Cytochrome b5 reductase | CYB5R3 |

| Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase | DPYD |

| Esterases | AADAC, CEL, CES1, CES1P1, CES2, CES3, CES5A, ESD, GZMA, GZMB, PON1, PON2, PON3, UCHL1, UCHL3 |

| Epoxidases | EPHX1, EPHX2 |

| Flavin-containing monooxygenases | FMO1, FMO2, FMO3, FMO4, FMO5, FMO6P |

| Glutathione reductase/peroxidases | GSR, GPX1, GPX2, GPX3, GPX4, GPX5, GPX6, GPX7 |

| Peptidases | DPEP1, METAP1 |

| Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases | PTGS1, PTGS2 |

| Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases | DHRS1, DHRS2, DHRS3, DHRS4, DHRS7, DHRS9, DHRS12, DHRS13, DHRSX, HSD11B1, HSD17B10, HSD17B11, HSD17B14 |

| Superoxide dismutase | SOD1, SOD2 |

| Xanthine dehydrogenase | XDH |

| Phase II Enzymes | |

| Amino acid transferases | AGXT, BAAT, CCBL1 |

| Dehydrogenases | NQO1, NQO2, XDH |

| Esterases | CES1, CES2, CES3, CES4, CES5A |

| Glucuronosyl transferases | DDOST, UGT1A1, UGT1A10, UGT1A3, UGT1A4, UGT1A5, UGT1A6, UGT1A7, UGT1A8, UGT1A9, UGT2A1, UGT2A3, UGT2B10, UGT2B11, UGT2B15, UGT2B17, UGT2B28, UGT2B4, UGT2B7, UGT3A1, UGT8 |

| Glutathione transferases | GSTA1, GSTA2, GSTA3, GSTA4, GSTA5, GSTCD, GSTK1, GSTM1, GSTM2, GSTM3, GSTM4, GSTM5, GSTO1, GSTO2, GSTP1, GSTT1, GSTT2, GSTZ1, MGST1, MGST2, MGST3, PTGES |

| Methyl transferases | AS3MT, ASMT, COMT, GAMT, GNMT, HNMT, INMT, NNMT, PNMT, TPMT |

| N-Acetyl transferases | AANAT, ACSL1, ACSL3, ACSL4, ACSM1, ACSM2B, ACSM3, GLYAT, NAT1, NAT2, NAA20, SAT1 |

| Thioltransferase | GLRX |

| Sulfotransferases | SULT1A1, SULT1A2, SULT1A3, SULT1B1, SULT1C1, SULT1C2, SULT1C3, SULT1C4, SULT1E1, SULT2A1, SULT2B1, SULT4A1, SULT6B1, TST, CHST1, CHST2, CHST3, CHST4, CHST5, CHST6, CHST7, CHST8, CHST9, CHST10, CHST11, CHST12, CHST13, GAL3ST1 |

Note: See Appendix B for long-form names of genes listed.

Among these enzymes, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4/5 are the most relevant in the pharmacogenetics of CNS drugs [15], [111] (Table 27.1). Approximately 18% of neuroleptics are major substrates of CYP1A2 enzymes, 40% of CYP2D6, and 23% of CYP3A4; 24% of antidepressants are major substrates of CYP1A2 enzymes, 5% of CYP2B6, 38% of CYP2C19, 85% of CYP2D6, and 38% of CYP3A4; 7% of benzodiazepines are major substrates of CYP2C19 enzymes, 20% of CYP2D6, and 95% of CYP3A4 [15], [111]. Most CYP enzymes exhibit ontogenic-, age-, sex-, circadian-, and ethnic-related differences [112].

In dementia, as in any other CNS disorder, CYP genomics is a very important issue, since in practice more than 90% of patients with dementia are daily consumers of psychotropics. Furthermore, some acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (the most prescribed antidementia drugs worldwide) are metabolized via CYP enzymes (Table 27.1). Most CYP enzymes display highly significant ethnic differences, indicating that the enzymatic capacity of these proteins varies depending upon the polymorphic variants present in their coding CYP genes.

The practical consequence of this genetic variation is that the same drug can be differentially metabolized according to the genetic profile of each subject, and that, if an individual’s pharmacogenomic profile is known, his/her pharmacodynamic response is potentially predictable. This is the cornerstone of pharmacogenetics. In this regard, the CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4/5 genes and their respective protein products deserve special consideration.

27.7.3.1. CYP2D6

CYP2D6 is a 4.38 kb gene with 9 exons mapped on 22q13.2. Four RNA transcripts of 1190–1684 bp are expressed in the brain, liver, spleen, and reproductive system, where 4 major proteins of 48–55 kDa (439–494 aa) are identified. It is a transport enzyme of the cytochrome P450 subfamily IID or multigenic cytochrome P450 superfamily of mixed-function monooxygenases. The cytochrome P450 proteins are monooxygenases which catalyze many reactions involved in drug metabolism and synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids. CYP2D6 localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and is known to metabolize as many as 25% of commonly prescribed drugs, and more than 60% of current psychotropics. Its substrates include debrisoquine, an adrenergic-blocking drug; sparteine and propafenone, both antiarrhythmic drugs; and amitryptiline, an antidepressant. CYP2D6 is highly polymorphic in the population.

There are 141 CYP2D6 allelic variants, of which -100C > T, -1023C > T, -1659G > A, -1707delT, -1846G > A, -2549delA, -2613-2615delAGA, -2850C > T, -2988G > A, and -3183G > A represent the ten most important [113], [114], [115]. Different alleles result in the extensive, intermediate, poor, and ultrarapid metabolizer phenotypes, characterized by normal, intermediate, decreased, and multiplied ability to metabolize the enzyme’s substrates, respectively. The hepatic cytochrome P450 system is responsible for the first phase in the metabolism and elimination of numerous endogenous and exogenous molecules and ingested chemicals. P450 enzymes convert these substances into electrophilic intermediates, which are then conjugated by phase II enzymes (e.g., UDP glucuronosyltransferases, N-acetyltransferases) to hydrophilic derivatives that can be excreted. According to the database of the World Guide for Drug Use and Pharmacogenomics [113], 982 drugs are CYP2D6-related: 371 are substrates, more than 300 are inhibitors, and 18 are CYP2D6 inducers.

In healthy subjects, extensive metabolizers (EMs) account for 55.71% of the population; intermediate metabolizers (IMs) account for 34.7%; poor metabolizers (PMs), 2.28%; and ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs), 7.31%. Remarkable worldwide interethnic differences exist in the frequency of the PM and UM phenotypes [116], [117], [118]. On average, approximately 6.28% of the world’s population belongs to the PM category. Europeans (7.86%), Polynesians (7.27%), and Africans (6.73%) show the highest rate of PMs, whereas Orientals (0.94%) show the lowest [116]. The frequency of PMs among Middle Eastern populations, Asians, and Americans is in the range of 2–3%. CYP2D6 gene duplications are relatively infrequent among Northern Europeans, but in East Africa the frequency of alleles with duplication of CYP2D6 is as high as 29% [119]. In Europe, there is a North–South gradient in the frequency of PMs (6–12% of PMs in Southern European countries, and 2–3% of PMs in Northern latitudes) [111].

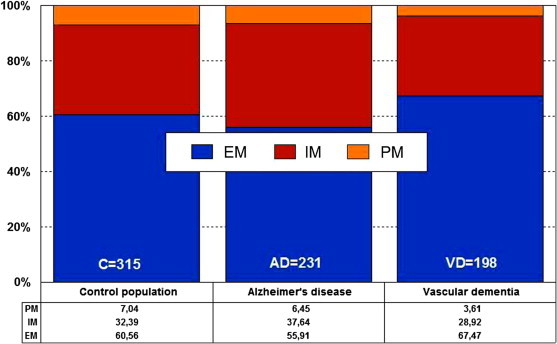

In AD, EMs, IMs, PMs, and UMs are 56.38%, 27.66%, 7.45%, and 8.51%, respectively, and in vascular dementia, they are, respectively, 52.81%, 34.83%, 6.74%, and 5.62% (Figure 27.3 ). There is an accumulation of AD-related risk genes in PMs and UMs. EMs and IMs are the best responders, and PMs and UMs are the worst responders to a combination therapy of cholinesterase inhibitors, neuroprotectants, and vasoactive substances. The pharmacogenetic response in AD appears to depend on the networking activity of genes involved in drug metabolism and genes involved in AD pathogenesis [7], [12], [15], [16], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

Figure 27.3.

Distribution and frequency of CYP2D6 phenotypes in AD and vascular dementia.

EM—extensive metabolizer; IM—intermediate metabolizer; PM—poor metabolizer; UM—ultrarapid metabolizer.

Source: Adapted from Cacabelos[18].

27.7.3.2. CYP2C9

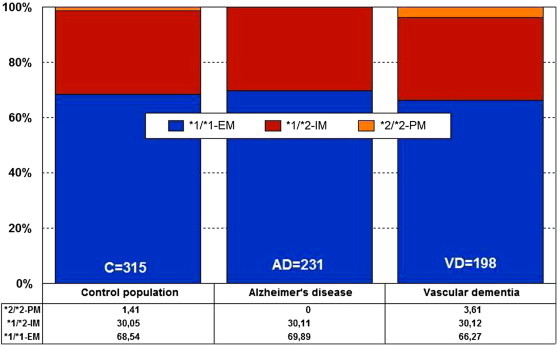

CYP2C9 is a gene (50.71 kb) with 9 exons mapped on 10q24. An RNA transcript of 1860 bp is mainly expressed in hepatocytes, where a protein of 55.63 kDa (490 aa) can be identified. More than 600 drugs are CYP2C9-related: 311 act as substrates (177 major, 134 minor); 375, as inhibitors (92 weak, 181 moderate, and 102 strong); and 41 as inducers of the CYP2C9 enzyme [113]. There are 481 CYP2C9 SNPs. By phenotype (Figure 27.4 ), in the control population, PMs represent 7.04%, IMs 32.39%, and EMs 60.56%. In AD, PMs, IMs, and EMs are 6.45%, 37.64%, and 55.91%, respectively, and in vascular dementia they are 3.61%, 28.92%, and 67.47%, respectively [18] (Figure 27.4).

Figure 27.4.

Distribution and frequency of CYP2C9 phenotypes in AD and vascular dementia.

EM—extensive metabolizer; IM—intermediate metabolizer; PM—poor metabolizer.

Source: Adapted from Cacabelos[18].

27.7.3.3. CYP2C19

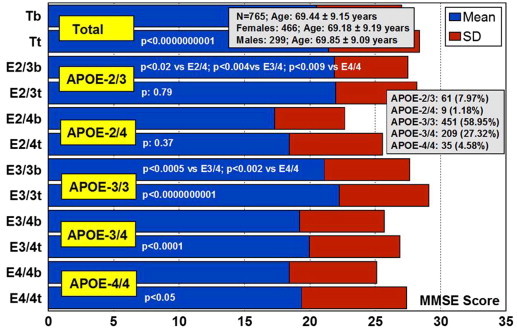

CYP2C19 is a gene (90.21 kb) with 9 exons mapped on 10q24.1q24.3. RNA transcripts of 1901 bp, 2395 bp, and 1417 bp are expressed in liver cells, where a protein of 55.93 kDa (490 aa) has been identified. Nearly 500 drugs are CYP2C19-related, with 281 acting as substrates (151 major, 130 minor), 263 as inhibitors (72 weak, 127 moderate, and 64 strong), and 23 as inducers of the CYP2C19 enzyme [113]. About 541 SNPs have been detected in the CYP2C19 gene. The frequencies of the three major CYP2C19 geno-phenotypes in the control population are CYP2C19-*1/*1-EMs, 68.54%; CYP2C19-*1/*2-IMs, 30.05%; and CYP2C19-*2/*2-PMs, 1.41%. EMs, IMs, and PMs account for 69.89%, 30.11%, and 0%, respectively, in AD, and 66.27%, 30.12%, and 3.61%, respectively, in vascular dementia [18] (Figure 27.5 ).

Figure 27.5.

Distribution and frequency of CYP2C19 pheno- genotypes in AD and vascular dementia.

EM—extensive metabolizer; IM—intermediate metabolizer; PM—poor metabolizer.

Source: Adapted from Cacabelos[18].

27.7.3.4. CYP3A4/5

CYP3A4 is a gene (27.2 kb) with 13 exons mapped on 7q21.1. RNA transcripts of 2153 bp, 651 bp, 564 bp, 2318 bp, and 2519 bp are expressed in intestine, liver, prostate, and other tissues, where four protein variants of 57.34 kDa (503 aa), 17.29 kDa (153 aa), 40.39 kDa (353 aa), and 47.99 kDa (420 aa) have been identified. The human CYP3A locus contains the three CYP3A genes (CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7), three pseudogenes, and a novel CYP3A gene termed CYP3A43. The gene encodes a putative protein with 71.5–75.8% identity with the other CYP3A proteins. The predominant hepatic form is CYP3A4, but CYP3A5 contributes significantly to total liver CYP3A activity.

CYP3A4 metabolizes more than 1900 drugs: 1033 act as substrates (897 major, 136 minor); 696, as inhibitors (118 weak, 437 moderate, and 141 strong); and 241, as inducers of the CYP3A4 enzyme [113]. About 347 SNPs have been identified in the CYP3A4 gene (CYP3A4*1A: wild-type), 25 of which are of clinical relevance. Concerning CYP3A4/5 polymorphisms in AD, 82.75% of cases are EMs (CYP3A5*3/*3), 15.88% are IMs (CYP3A5*1/*3), and 1.37% are UMs (CYP3A5*1/*1). Unlike other human P450s (CYP2D6, CYP2C19), there is no evidence of a “null” allele for CYP3A4 [113].

27.7.3.5. CYP Clustering

The construction of a genetic map integrating the most prevalent CYP2D6+CYP2C19+CYP2C9 polymorphic variants in a trigenic cluster yields 82 different haplotype-like profiles. The most frequent trigenic genotypes in the AD population are *1*1-*1*1-*1*1 (25.70%), *1*1-*1*2-*1*2 (10.66%), *1*1-*1*1-*1*1 (10.45%), *1*4-*1*1-*1*1 (8.09%), *1*4-*1*2-*1*1 (4.91%), *1*4-*1*1-*1*2 (4.65%), and *1*1-*1*3-*1*3 (4.33%). These 82 trigenic genotypes represent 36 different pharmacogenetic phenotypes.

According to these trigenic clusters, only 26.51% of patients show a pure 3EM phenotype, 15.29% are 2EM1IM, 2.04% are pure 3IM, 0% are pure 3PM, and 0% are 1UM2PM (the worst possible phenotype). This implies that only one-quarter of the population normally process the drugs that are metabolized via CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 (approximately 60% of the drugs in current use) [12]. Taking into consideration the data available, it might be inferred that at least 20–30% of the AD population may exhibit an abnormal metabolism of cholinesterase inhibitors and/or other drugs that undergo oxidation via CYP2D6-related enzymes.

Approximately 50% of this population cluster shows an ultrarapid metabolism, requiring higher doses of cholinesterase inhibitors in order to reach a therapeutic threshold. The other 50% of the cluster exhibit a poor metabolism, displaying potential adverse events at low doses. If we take into account that approximately 60–70% of therapeutic outcomes depend on pharmacogenomic criteria (e.g., pathogenic mechanisms associated with AD-related genes), it can be postulated that pharmacogenetic and pharmacogenomic factors are responsible for 75–85% of therapeutic response (efficacy) in AD patients treated with conventional drugs [12], [15], [16], [17], [18], [22], [23], [24], [25], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

27.7.4. Drug Transporters

ABC genes—especially ABCB1 (ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B, member 1P-glycoprotein-1, P-gp1, Multidrug Resistance 1, MDR (17q21.12), ABCC1 (9q31.1), ABCG2 (White121q22.3), and other genes of this family—encode proteins that are essential for drug metabolism and transport. The multidrug efflux transporters P-gp, the multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4), and the breast cancer resistance-protein (BCRP), located on endothelial cells lining the brain vasculature, play important roles in limiting the movement of substances into the brain and in enhancing their efflux from the brain.

Transporters also cooperate with phase I/phase II metabolism enzymes by eliminating drug metabolites. Their major features are their capacity to recognize drugs belonging to unrelated pharmacological classes and their redundancy, by which a single molecule can act as a substrate for different transporters. This ensures efficient neuroprotection against xenobiotic invasions. The pharmacological induction of ABC gene expression is a mechanism of drug interaction, which may affect substrates of the upregulated transporter; overexpression of MDR transporters confers resistance to anti-cancer agents and CNS drugs [120], [121].

Also of importance for CNS pharmacogenomics are transporters encoded by genes of the solute carrier superfamily (SLC) and solute carrier organic (SLCO) transporter family, which are responsible for the transport of multiple endogenous and exogenous compounds, including folate (SLC19A1), urea (SLC14A1, SLC14A2), monoamines (SLC29A4, SLC22A3), aminoacids (SLC1A5, SLC3A1, SLC7A3, SLC7A9, SLC38A1, SLC38A4, SLC38A5, SLC38A7, SLC43A2, SLC45A1), nucleotides (SLC29A2, SLC29A3], fatty acids (SLC27A1-6), neurotransmitters (SLC6A2[noradrenaline transporter]), SLC6A3[dopamine transporter], SLC6A4[serotonin transporter, SERT], SLC6A5, SLC6A6, SLC6A9, SLC6A11, SLC6A12, SLC6A14, SLC6A15, SLC6A16, SLC6A17, SLC6A18, SLC6A19), glutamate (SLC1A6, SLC1A7), and others [122].

Some organic anion transporters (OAT), which belong to the solute carrier (SLC) 22A family, are also expressed at the BBB, and regulate the excretion of endogenous and exogenous organic anions and cations [123]. The transport of amino acids and di- and tripeptides is mediated by a number of different transporter families, and the bulk of oligopeptide transport is attributable to the activity of members of the SLC15A superfamily (peptide transporters 1 and 2 (SLC15A1[PepT1]) and SLC15A2[PepT2], and peptide/histidine transporters 1 and 2 (SLC15A4[PHT1] and SLC15A3[PHT2]). ABC and SLC transporters expressed at the BBB may cooperate to regulate the passage of different molecules into the brain [124]. Polymorphic variants in ABC and SLC genes may also be associated with pathogenic events in CNS disorders and drug-related safety and efficacy complications [111], [122].

27.7.5. Pleiotropic Activity of APOE in Dementia

APOE is the prototypical paradigm of a pleiotropic gene with multifaceted activities in physiological and pathological conditions [16], [22]. ApoE is consistently associated with the amyloid plaque marker for AD. APOE-4 may influence AD pathology interacting with APP metabolism and Aβ accumulation, enhancing hyperphosphorylation of tau protein and NFT formation, reducing choline acetyltransferase activity, increasing oxidative processes, modifying inflammation-related neuroimmunotrophic activity and glial activation, altering lipid metabolism, lipid transport, and membrane biosynthesis in sprouting and synaptic remodeling, and inducing neuronal apoptosis [16], [23], [24], [25].

To address the complex misfolding and aggregation that initiates the toxic cascade resulting in AD, Petrlova et al. [26] developed a 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid spin-labeled amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide to observe its isoform-dependent interaction with the ApoE protein. Oligomer binding involves the C-terminal domain of ApoE, with ApoE3 reporting a much greater response through this conformational marker. ApoE3 displays a higher affinity and capacity for the toxic Aβ oligomer. ApoE polymorphism and AD risk can largely be attributed to the reduced ability of ApoE4 to function as a clearance vehicle for the toxic form of Aβ. MAPT and APOE are involved in the pathogenic mechanisms of AD, and both the MAPT H1/H1 genotype and the APOE ɛ4 allele lead to a more rapid progression to dementia among MCI subjects, probably mediating an increased rate of amyloid-β and tau brain deposition [27].

The distribution of APOE genotypes in the Iberian peninsula is as follows: APOE-2/2 0.32%; APOE-2/3 7.3%; APOE-2/4 1.27%; APOE-3/3 71.11%; APOE-3/4 18.41%; and APOE-4/4 1.59% [18] (Figure 27.2). These frequencies are very similar in Europe and in other Western societies. There is a clear accumulation of APOE-4 carriers among patients with AD (APOE-3/4 30.30%, APOE-4/4 6.06%) and vascular dementia (APOE-3/4 35.85%, APOE-4/4 6.57%) as compared to controls (Figure 27.2). Different APOE genotypes confer specific phenotypic profiles to AD patients [15], [16], [22]. Some of these profiles may add risk or benefit when patients are treated with conventional drugs, and in many instances the clinical phenotype demands the administration of additional drugs that increase the complexity of therapeutic protocols.

From studies designed to define APOE-related AD phenotypes [7], [12], [23], [24], [25], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], several conclusions can be drawn, which are shown in Box 27.2. These 20 major phenotypic features clearly illustrate the biological disadvantage of APOE-4 homozygotes and the potential consequences that these patients may experience when they receive pharmacological treatment for AD and/or concomitant pathologies [7], [12], [23], [24], [25], [28], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

Box 27.2. Key Conclusions Regarding APOE-Related AD Phenotypes.

-

1.

The age at onset is 5–10 years earlier in approximately 80% of AD cases harboring the APOE-4/4 genotype.

-

2.

The serum levels of ApoE are lowest in APOE-4/4, intermediate in APOE-3/3 and APOE-3/4, and highest in APOE-2/3 and APOE-2/4.

-

3.

Serum cholesterol levels are higher in APOE-4/4 than in other genotypes.

-

4.

HDL-cholesterol levels tend to be lower in APOE-3 homozygotes than in APOE-4 allele carriers.

-

5.

LDL-cholesterol levels are systematically higher in APOE-4/4 than in any other genotype.

-

6.

Triglyceride levels are significantly lower in APOE-4/4.

-

7.

Nitric oxide levels are slightly lower in APOE-4/4.

-

8.

Serum and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ levels tend to differ between APOE-4/4 and the other most frequent genotypes (APOE-3/3, APOE-3/4).

-

9.

Blood histamine levels are dramatically reduced in APOE-4/4 as compared to the other genotypes.

-

10.

Brain atrophy is markedly increased in APOE-4/4>APOE-3/4>APOE-3/3.

-

11.

Brain mapping activity shows a significant increase in slow wave activity in APOE-4/4 from the early stages of the disease.

-

12.

Brain hemodynamics, as reflected by reduced brain blood flow velocity and increased pulsatility and resistance indices, is significantly worse in APOE-4/4 (and in APOE-4 carriers in general, as compared with APOE-3 carriers); brain hypoperfusion and neocortical oxygenation is also more deficient in APOE-4 carriers.

-

13.

Lymphocyte apoptosis is markedly enhanced in APOE-4 carriers.

-

14.

Cognitive deterioration is faster in APOE-4/4 patients than in carriers of any other APOE genotype.

-

15.

In approximately 3–8% of AD cases, some dementia-related metabolic dysfunctions accumulate more in APOE-4 carriers than in APOE-3 carriers.

-

16.

Some behavioral disturbances, alterations in circadian rhythm patterns, and mood disorders are slightly more frequent in APOE-4 carriers.

-

17.

Aortic and systemic atherosclerosis is more frequent in APOE-4 carriers.

-

18.