Abstract

Background

Improper practices and unprofessional conduct in clinical research have been shown to waste a significant portion of healthcare funds and harm public health.

Objectives

Our objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of educational or policy interventions in research integrity or responsible conduct of research on the behaviour and attitudes of researchers in health and other research areas.

Search methods

We searched the CENTRAL, MEDLINE, LILACS and CINAHL health research bibliographical databases, as well as the Academic Search Complete, AGRICOLA, GeoRef, PsycINFO, ERIC, SCOPUS and Web of Science databases. We performed the last search on 15 April 2015 and the search was limited to articles published between 1990 and 2014, inclusive. We also searched conference proceedings and abstracts from research integrity conferences and specialized websites. We handsearched 14 journals that regularly publish research integrity research.

Selection criteria

We included studies that measured the effects of one or more interventions, i.e. any direct or indirect procedure that may have an impact on research integrity and responsible conduct of research in its broadest sense, where participants were any stakeholders in research and publication processes, from students to policy makers. We included randomized and non‐randomized controlled trials, such as controlled before‐and‐after studies, with comparisons of outcomes in the intervention versus non‐intervention group or before versus after the intervention. Studies without a control group were not included in the review.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. To assess the risk of bias in non‐randomized studies, we used a modified Cochrane tool, in which we used four out of six original domains (blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias) and two additional domains (comparability of groups and confounding factors). We categorized our primary outcome into the following levels: 1) organizational change attributable to intervention, 2) behavioural change, 3) acquisition of knowledge/skills and 4) modification of attitudes/perceptions. The secondary outcome was participants' reaction to the intervention.

Main results

Thirty‐one studies involving 9571 participants, described in 33 articles, met the inclusion criteria. All were published in English. Fifteen studies were randomized controlled trials, nine were controlled before‐and‐after studies, four were non‐equivalent controlled studies with a historical control, one was a non‐equivalent controlled study with a post‐test only and two were non‐equivalent controlled studies with pre‐ and post‐test findings for the intervention group and post‐test for the control group. Twenty‐one studies assessed the effects of interventions related to plagiarism and 10 studies assessed interventions in research integrity/ethics. Participants included undergraduates, postgraduates and academics from a range of research disciplines and countries, and the studies assessed different types of outcomes.

We judged most of the included randomized controlled trials to have a high risk of bias in at least one of the assessed domains, and in the case of non‐randomized trials there were no attempts to alleviate the potential biases inherent in the non‐randomized designs.

We identified a range of interventions aimed at reducing research misconduct. Most interventions involved some kind of training, but methods and content varied greatly and included face‐to‐face and online lectures, interactive online modules, discussion groups, homework and practical exercises. Most studies did not use standardized or validated outcome measures and it was impossible to synthesize findings from studies with such diverse interventions, outcomes and participants. Overall, there is very low quality evidence that various methods of training in research integrity had some effects on participants' attitudes to ethical issues but minimal (or short‐lived) effects on their knowledge. Training about plagiarism and paraphrasing had varying effects on participants' attitudes towards plagiarism and their confidence in avoiding it, but training that included practical exercises appeared to be more effective. Training on plagiarism had inconsistent effects on participants' knowledge about and ability to recognize plagiarism. Active training, particularly if it involved practical exercises or use of text‐matching software, generally decreased the occurrence of plagiarism although results were not consistent. The design of a journal's author contribution form affected the truthfulness of information supplied about individuals' contributions and the proportion of listed contributors who met authorship criteria. We identified no studies testing interventions for outcomes at the organizational level. The numbers of events and the magnitude of intervention effects were generally small, so the evidence is likely to be imprecise. No adverse effects were reported.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence base relating to interventions to improve research integrity is incomplete and the studies that have been done are heterogeneous, inappropriate for meta‐analyses and their applicability to other settings and population is uncertain. Many studies had a high risk of bias because of the choice of study design and interventions were often inadequately reported. Even when randomized designs were used, findings were difficult to generalize. Due to the very low quality of evidence, the effects of training in responsible conduct of research on reducing research misconduct are uncertain. Low quality evidence indicates that training about plagiarism, especially if it involves practical exercises and use of text‐matching software, may reduce the occurrence of plagiarism.

Keywords: Humans, Plagiarism, Attitude, Biomedical Research, Biomedical Research/ethics, Controlled Before‐After Studies, Controlled Before‐After Studies/ethics, Controlled Before‐After Studies/standards, Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic, Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic/ethics, Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic/standards, Publishing, Publishing/ethics, Publishing/standards, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/ethics, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/standards, Research Personnel, Research Personnel/ethics, Research Personnel/standards, Scientific Misconduct, Scientific Misconduct/ethics

Plain language summary

Preventing misconduct and promoting integrity in research and publication

Doctors and patients need to be able to trust reports of medical research because these are used to help them make decisions about treatments. It is therefore important to prevent false or misleading research. Problems with research include various types of misconduct such as altering results (falsification), making up results (fabrication) or copying other people's work (plagiarism). Good systems that produce reliable research are said to show 'research integrity'. We studied activities, such as training, designed to reduce research misconduct and encourage integrity. The effects of some of these activities on researchers' attitudes, knowledge and behaviour have been studied and we brought together the evidence from these studies.

Some studies showed positive effects on researchers' attitudes to plagiarism. Practical training, such as using computer programs that can detect plagiarism, or writing exercises, sometimes decreased plagiarism by students but not all studies showed positive effects. We did not find any studies on fabrication or falsification. Two studies showed that the way in which journals ask authors for details about who did each part of a study can affect their responses.

Many of the studies included in this review had problems such as small sample sizes or had used methods that might produce biased results. The training methods tested in the studies (which included online courses, lectures and discussion groups) were often not clearly described. Most studies tested effects over short time periods. Many studies involved university students rather than active researchers.

In summary, the available evidence is of very low quality, so the effect of any intervention for preventing misconduct and promoting integrity in research and publication is uncertain. However, practical training about how to avoid plagiarism may be effective in reducing plagiarism by students, although we do not know whether it has long‐term effects.

Background

Description of the problem or issue

The two World Conferences on Research Integrity and the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity, Resnik 2011, called for the development of more comprehensive standards, codes and policies to promote research integrity both locally and on a global basis. However, there is little systematic evidence to guide the development and implementation of these standards. This systematic review assesses the existing evidence and identifies research questions that need to be addressed.

Description of the methods being investigated

Research integrity and responsible conduct of research emerged as a research topic in the 1990s after public reports of scientific fraud and the response by national policy makers to deal with the problem (Steneck 2006). Together with the growing understanding of research behaviour, there is also a growth of empirical information about interventions by institutions, funders, regulators, journal editors and other stakeholders to improve responsible conduct of research and foster research integrity. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the prevalence of fabrication, falsification or manipulation of research findings showed that an average of 1.97% (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 4.45) of scientists admitted such practices and that 9.54% (95% CI 5.15 to 13.94) admitted other questionable research practices (Fanelli 2009). Another meta‐analysis on authorship in research publications also demonstrated a high prevalence of reported problems with authorship (pooled weighted average of 29% (95% CI 24 to 35) of authors reporting their own or others' experience of abuse of authorship) (Marusic 2011).

There is a growing body of evidence on attitudes and practices of researchers relating to the responsible conduct of research, serious forms of misconduct (i.e. fabrication, falsification and plagiarism or 'FFP') and so‐called 'questionable research practices' (Steneck 2006). It is generally recognised that these behaviours form a continuum from outright misconduct at one end to ideal practices at the other, but that the boundaries between acceptable, careless, questionable and fraudulent behaviour are not universally defined.

How these methods might work

Interventions to foster responsible conduct of research or deter misconduct have been tested in a number of research settings and across research disciplines, although predominantly in medicine. Since some forms of misconduct and questionable research practices are assumed to result from ignorance rather than a deliberate intention to deceive, it is widely assumed that training will reduce such behaviours (Anderson 2007; Funk 2007; Hren 2007; Plemmons 2006). Other interventions are based on the concept of screening acting as a deterrent, for example text‐matching software may be used to screen material for plagiarism and it is believed that this will deter authors from these practices (Bilić‐Zulle 2008). Since misconduct involves breaches in ethics, other interventions focus on establishing or reinforcing an ethical culture, for example by the use of honour codes (Boyd 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

Improper practices and unprofessional conduct in clinical research have been shown to waste a significant portion of healthcare funds and adversely impact public health (Angel 2004). A synthesis of evidence for effective ways to promote responsible conduct of research and deter poor research practices should therefore have an important impact on the quality of research output. Understanding which techniques are effective will help institutions focus on these activities and also avoid interventions that may be counterproductive.

If published, fraudulent medical research can harm patients directly or indirectly. For example, a clinical trial that used a new method of predicting response to chemotherapy had to be stopped when the research on which the method was based was shown to be fraudulent. The paper was subsequently retracted but probably led to some cancer patients receiving suboptimal therapies (Reich 2011).

Although it is difficult to estimate the impact of misconduct outside of health research (Steneck 2006), a recent case study of the cost of research misconduct estimated the direct cost of an actual investigation to be USD 525,000 and indirect costs to be USD 1.3 million (Michalek 2010).

Objectives

Our objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of educational or policy interventions in research integrity or responsible conduct of research on the behaviour and attitudes of researchers in health and other research areas.

Since serious research and publication misconduct are relatively rare, and interventions may be designed to have long‐term effects, the effects of interventions on the frequency of misconduct are hard to measure. Therefore we also considered surrogate endpoints such as researcher attitudes.

In this review, we particularly focused on interventions aimed at fostering research integrity, which views research behaviour from the perspective of professional standards (Steneck 2006). We also explored interventions to prevent unacceptable or fraudulent research and publication practices.

As there is significant variability in defining how researchers should behave when performing and communicating research (Steneck 2006), for the purpose of this review we used the following definitions:

Responsible conduct of research was defined as "conducting research in ways that fulfil the professional responsibilities of researchers, as defined by their professional organizations, the institutions for which they work and, when relevant, the government and public" (Steneck 2006).

Research integrity was defined as "the quality of possessing and steadfastly adhering to high moral principles and professional standards, as outlined by professional organizations, research institutions and, when relevant, the government and public" (Steneck 2006). Research integrity was differentiated from academic integrity, which is broader than research integrity and is defined as commitment to "six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage" (ICAI 2013); lack of academic integrity also includes engaging in plagiarism, unauthorized collaboration, cheating or facilitating academic dishonesty (ICAI 2013). We included a study dealing with academic integrity in this review when it addressed plagiarism, because writing is an important component of authorship in research (ICMJE 2014).

Research ethics was defined as "moral problems associated with or that arise in the course of pursuing research" (Steneck 2006). Studies dealing with research ethics, regardless of how they were defined in the study, were included in the systematic review. We did not include studies dealing with professional ethics, which was defined as ethics related to professional work. While professional work generally includes research activities (Cogan 1953), we included studies which dealt with professional ethics only if research was explicitly specified as a study topic.

Research misconduct included all misbehaviours in research, from fabrication, falsification and plagiarism (FFP) as defined by the US Office of Research integrity to a more inclusive list of misbehaviours as defined by research integrity bodies in Scandinavian countries (Steneck 2006).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies of educational or policy interventions are usually conducted in natural settings where a true randomized controlled design may not always be feasible. This is probably even truer for the topic of research integrity, which has only relatively recently become the focus of scientific investigations. For these reasons, we planned to include in our review not only randomized controlled trials, but also non‐randomized controlled trials, such as controlled before‐and‐after studies, interrupted time series and regression discontinuity designs. We excluded observational (survey) data when there was no clear intervention or manipulation. We also excluded study designs without a comparison group. For controlled before‐and‐after studies we included studies that had before‐and‐after measurements for the intervention group and only one measurement for the control group. We examined quasi‐experimental designs closely for threats to validity.

We included studies irrespective of publication status and language.

Types of data

We included studies that measured the effects of one or more interventions, such as teaching, training, mentoring, use of checklists, screening and policy, on research integrity or responsible conduct of research in its broadest sense, including 'questionable research practices' and publication misconduct. We considered interventions in any type of researcher or student, at any period of their research career, in all fields of research, including sciences, social sciences and humanities. We did not evaluate the effectiveness of reporting guidelines for improving the presentation of research data, as this is not directly related to research integrity, but rather to the quality of reporting, and has been covered by other systematic reviews (e.g. Plint 2006; Turner 2012).

Types of participants

The participants included any stakeholders in the research and publication process, such as: 1) students, who may or may not have an interest in becoming researchers, if they received an intervention related to research integrity; 2) health workers involved in research; 3) researchers working at institutions or commercial research establishments; 4) authors, peer reviewers and/or editors of scholarly journals; 5) professional and/or research organizations; and 6) policy makers.

Types of interventions

Eligible interventions included any direct or indirect procedure that may have an impact on research integrity, from direct educational interventions, such as a formal course or training required by institutions or authorities (such as training required by Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees), to indirect interventions, such as policy change (e.g. introduction of statements on conflict of interest or authorship contribution declarations in journals).

Types of methods

We included the studies with comparisons of outcomes in intervention versus non‐intervention groups or before versus after the intervention. We assessed the groups for baseline comparability, such as age, gender, educational/professional level and other relevant variables. We included studies that we judged to have reasonable baseline comparability and to be similar in important demographic characteristics that might reasonably be thought to influence response to the intervention or otherwise affect outcomes.

Types of outcome measures

The basis for our classification of outcomes was the four‐level typology first described by Kirkpatrick (Kirkpatrick 1967) and modified by Barr et al (Barr 2000):

Level 1 outcomes refer to learners' reaction to the intervention, including participants' views of their learning experience and satisfaction with the programme.

Level 2a outcomes refer to modification of attitudes and/or perceptions regarding responsible conduct of research.

Level 2b outcomes refer to acquisition of knowledge and/or skills related to responsible conduct of research.

Level 3 outcomes refer to behavioural change transferred from the learning environment to the workplace prompted by modifications in attitudes or perceptions, or the application of newly acquired knowledge/skills in practice. We further divided this level into:

3a – behavioural intentions; and

3b – actual change in research or publication practices, or both.

Level 4 outcomes refer to organizational changes attributable to the intervention.

We included outcomes at the individual level (e.g. individual behaviour change) and as aggregated units of analysis (e.g. frequency of retracted articles).

There was no outcome measure or set of outcome measures that we could consider 'standard' for the purposes of this review as we expected a wide range of different outcomes to be found in included studies. Our intention was to classify them in a theoretically grounded way, so that we could meaningfully present the study results if meta‐analysis was not appropriate due to the high heterogeneity of the studies. Kirkpatrick's four‐level model (Kirkpatrick 1967) is a standard approach in educational research (Barr 2000). As we assessed interventions aimed at reducing/preventing misconduct, we considered actual change in behaviour, either on the individual level (3rd level in Kirkpatrick's model) or at the organizational level (4th level) as a hierarchically higher (or 'better', more desirable) outcome than participants' satisfaction with an intervention (1st level). As 1st level outcomes are the easiest to assess, they are commonly used in educational research. However, they are the least informative and relevant, so we categorized them as secondary outcomes.

The inclusion of studies addressing perceptions and attitudes in the systematic review was based on Ajzen's theory of planned behaviour, in which the main predictors of behavioural intentions are attitudes towards the behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen 2005; Armitage 2001). Harms outcomes or potentially adverse effects were not expected and we did not assess them in this review.

Primary outcomes

We assessed the following primary outcomes:

Primary outcome 1: Organizational change (level 4 outcome according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology).

Primary outcome 2: Behavioural change (level 3 outcome according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology).

Primary outcome 3: Acquisition of knowledge and/or skills (level 2b outcome according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology).

Primary outcome 4: Modification of attitudes and/or perceptions (level 2a outcome according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology).

Secondary outcomes

Level of satisfaction or participants' experience with the intervention (level 1 outcome according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology).

Search methods for identification of studies

As the concepts of research integrity and responsible conduct of research emerged in the scientific community only after the establishment and active work of the Office for Research Integrity (ORI) in the USA in 1989 (Steneck 2006) and in Denmark in 1992 (Nylenna 1999), we limited our search to 1990 to December 2014.

Electronic searches

We searched the following bibliographic databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, December 2014) via OvidSP;

MEDLINE via OvidSP (1946 to December 2014);

LILACS via BIREME (to December 2014);

CINAHL via EBSCOhost (1981 to December 2014).

We also searched the following specialized or general electronic databases:

Academic Search Complete – multi‐disciplinary full‐text and bibliographical database from the EBSCO Publishing platform (1887 to December 2014).

AGRICOLA, multidisciplinary database from the US National Agricultural Library, available via the OvidSP platform (1970 to December 2014).

GeoRef – database from the American Geosciences Institute, available via the EBSCO Publishing platform (1933 to December 2014).

PsycINFO – database from the American Psychological Association, available via the OvidSP platform (1806 to December 2014).

ERIC – database of education literature, via OvidSP platform (1965 to December 2014).

SCOPUS – citation database from Elsevier.

Web of Science (WoS): SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI – citation database from Thomson Reuters.

We did not separately search the EMBASE bibliographic database because SCOPUS includes EMBASE data (Burnham 2006).

For the identification of studies to be included or considered for this review, we developed separate search strategies for each database searched. These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE but revised appropriately for each database to take account of differences in the controlled vocabulary and syntax rules.

The subject search used a combination of controlled vocabulary, if appropriate, and free‐text terms based on the search strategy for searching MEDLINE. The initial search strategy for MEDLINE, as presented in the protocol, was partly changed and further developed. The search strategies we used for each database are reported in Appendix 1. We performed all searches in January 2013 and updated them in April 2015, searching for articles published between 1990 and 2014, inclusive. There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched conference proceedings and abstracts in the following resources:

Research presented at the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) Research Integrity Conferences (https://ori.hhs.gov/conference).

Peer Review Congresses (http://www.peerreviewcongress.org/previous.html).

Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research Conferences (http://www.primr.org/conferences/).

Research Ethics site (http://researchethics.ca/).

We also searched a book on promoting research integrity by education (Institute of Medicine 2002) and publications from ORI‐funded research, listed at: http://ori.dhhs.gov/research/extra/rri_publications.shtml.

Finally, we handsearched the electronic tables of contents of the following journals that regularly publish on research integrity topics:

Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics (available online from volume 1 in 2006).

Science and Engineering Ethics (available online from volume 1 in 1995).

Accountability in Research (available online from volume 1 in 1989).

Ethics and Behavior (available online from volume 1 in 1991).

Journal of Higher Education (last available volume: 2002).

Journal of Medical Ethics (available online from volume 1 in 1975).

Academic Medicine (available online from volume 1 in 1926).

Medical Education (available online from volume 1 in 1966).

Medical Teacher (available online from volume 1 in 1979).

Teaching and Learning in Medicine (available online from volume 1 in 1989).

Professional Ethics: A Multidisciplinary Journal (available online from 1992; merged in 2004 with Business and Professional Ethics, which is available online since 1981).

American Psychologist (available online from volume 1 in 1946).

Journal of Business Ethics (available online from volume 16 in 1997).

Journal of Academic Ethics (available online from volume 1 in 2003).

We also searched the references of all studies analysed in full text, as well as retrieved review articles, using both 'forward' (through citation databases such as Web of Science) and 'backward' (examining reference lists) citation searching (Horsley 2011).

Data collection and analysis

Following the execution of the search strategies, we collated the identified records (titles and available abstracts) in an EndNote database for de‐duplication (Thomson Reuters 2011). We created the final unique record set and full text of potentially eligible studies as a separate EndNote file, from which we carried out screening of records and extraction of data from included articles.

Selection of studies

We expected a large volume of records from the initial database search because of the broad and general nature of many search terms. For this reason, we first conducted an initial screening of the titles only, including the screening of the abstract when the title was uninformative. In the next step, we screened the abstracts (and full text when needed, particularly in publications outside of biomedicine and health, which often had brief abstracts). After exclusions at these two steps, we reviewed all remaining potentially eligible articles in full text for eligibility, using a priori defined eligibility criteria. Two review authors (AM and EW) independently performed each step. Disagreements between review authors at the stage of full‐text analysis were resolved by consensus or by a third member of the team (HRR).

Data extraction and management

Two members of the review team (AM and EW) independently extracted the data on study characteristics and outcome data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consultation with the third team member (HRR). The review authors were not blinded to the authors, interventions or results obtained in the included studies.

We extracted and entered the following data in a customized collection form:

Study design (e.g. randomized controlled trial, controlled before‐and‐after, etc.), date and length of follow‐up.

Participants: a) sample size and b) inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographic characteristics of participants: age, sex, country of origin, ethnicity, gender, field of research, academic level or research experience.

Setting: type of institution or broader setting where the intervention(s) took place.

Interventions: details of the type and duration of intervention and comparisons.

Outcomes: detailed description of the outcomes of interest, including the method and timing of measurement.

Source of funding.

We extracted results for pre‐specified types of outcomes of interest. We extracted the raw data available in the study, such as means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes and number of events and participants for dichotomous outcomes. As meta‐analysis of retrieved studies was not possible, we did not attempt to obtain original data if they were not adequately presented in the retrieved publication.

For studies that presented results in graphs (Brown 2001; Landau 2002), we generated numerical values using digitizing software (Huwaldt 2014). For one study (Brown 2001), which presented data for individual scales but performed statistical analysis for composite scores, we averaged mean scores and standard deviations for composite scores using appropriate formula (Headrick 2010).

We designed the data extraction form for this review based on forms available from other Cochrane Review Groups, and piloted it before use. When several articles reported different outcomes of the same study, we considered them a single entry in the data extraction form.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For randomized controlled trials, we assessed the risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool, which addresses the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (separately for researcher‐assessed and self reported outcomes), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias.

For the assessment of non‐randomized studies, we used a modified Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, in which we used four out of six original domains (blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias) and two additional domains (comparability of groups and confounding factors) to assess the risk of bias in the included non‐randomized studies. For the additional two domains we used the following questions for assessment: "Were the study groups comparable at baseline?" and "Were potential confounding factors adequately addressed?". As recommended in Chapter 13 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we collected factual information on the confounders considered in the included studies and reported them in a table. We did not assess the risk of bias on the domains of sequence generation and concealment of allocation sequence, as a high risk on these domains is inherent in the design of non‐randomized studies and therefore expectable by default. We participated in the pilot study for a Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool for Non‐Randomized Studies of Interventions ‐ ACROBAT‐NRSI tool (Sterne 2014), but found that it was not fully suitable because the published articles on studies included in the review did not report many of the items needed for the NRSI tool.

For all study designs, we assessed compliance with intervention and possible contamination (spillover effect) between the groups under the domain of other sources of bias. We recorded each piece of information extracted for the 'Risk of bias' tool together with the precise source of this information. We first tested data collection forms and assessments of the risk of bias on a pilot sample of articles. Two assessors (AM and DS) independently carried out the assessment of risk of bias. The assessors were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, journal or results of a study. We tabulated risk of bias for each included study, along with a judgement of low, high or unclear risk of bias, as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Measures of the effect of the methods

In the meta‐analyses planned in the protocol for this systematic review, we had intended to use standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals. However, we decided that meta‐analysis would not be appropriate because of the heterogeneity of the included studies.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was generally the individual study participant. Where the unit of assignment to an intervention was not the individual, but some larger entity (e.g. a department or an institution), the unit of analysis was the larger entity.

Dealing with missing data

In the protocol, we planned to address the problem of missing data required for data synthesis or 'Risk of bias' assessment by contacting the authors to request the data (Young 2011). However, because most of the studies with missing information were published a long time ago, often did not show an e‐mail address for the corresponding author and were published in fields outside biomedicine and health, we did not systematically contact study authors. In a single case where we contacted two authors of a study, we did not get a response.

Data synthesis

There were significant differences in the study designs and outcomes among included studies, therefore it was not possible to carry out a meta‐analysis. The results are presented descriptively for individual studies, grouped according to four‐level typology for educational outcomes (Barr 2000). This did not lend itself to building a 'Summary of findings' table. In 'Additional tables', we noted whether there was a significant effect or not for each outcome. We are aware that "vote counting" is not recommended in data analysis, but the tables make the findings more understandable within the context of our qualitative synthesis.

Quality of the evidence

We followed the GRADE approach in the assessment of the quality of evidence (Grade Working Group 2004). We considered limitations of included studies (risk of bias), indirectness of evidence, inconsistency (heterogeneity), imprecision of effect estimates and potential publication bias. We considered randomized controlled trials to start from 'high quality' and observational studies from 'low quality'. As we did not pool the data and the outcomes in the included studies were very diverse, we could only make a general statement on the quality of the evidence as a whole, taking into account the different GRADE domains. Also, we commented on possible factors affecting the quality of the evidence.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies. We ordered the included studies so that randomized studies are presented first, followed by other types of study designs.

Results of the search

We identified 20,888 unique published records, of which we excluded 20,658 after title screening and a further 188 after abstract/full‐text screening. This left 42 potentially eligible publications for detailed independent eligibility assessment (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Thirty‐one studies involving 9571 participants, described in 33 articles, met the inclusion criteria. All were published in English. Fifteen studies reported the dates of the study, which ranged from 2001 to 2009 (Arnott 2008; Ballard 2013; Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Brown 2001; Dee 2012; Estow 2011; Ivaniš 2008; Kose 2011; Marshall 2011; Marušić 2006; Moniz 2008; Risquez 2011; Roberts 2007; Rolfe 2011).

Randomized studies

Fifteen studies were randomized controlled trials, involving 5275 participants (Aggarwal 2011; Ballard 2013; Brown 2001; Compton 2008; Dee 2012; Ivaniš 2008; Landau 2002; Marušić 2006; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Roberts 2007; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011). One of these was presented in two published articles (Roberts 2007). Six had two intervention arms (Aggarwal 2011; Dee 2012; Ivaniš 2008; Newton 2014; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004); four had three arms (Brown 2001; Marušić 2006; Moniz 2008; Roberts 2007), and four had four arms (Ballard 2013; Compton 2008; Landau 2002; Youmans 2011). All randomized controlled trials, except one (Aggarwal 2011), had only post‐test evaluation without baseline measurement. The trials took place mostly in the USA (nine studies: Ballard 2013; Compton 2008; Dee 2012; Landau 2002; Moniz 2008; Roberts 2007; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011), one each in Australia (Newton 2014), India (Aggarwal 2011), Ireland (Risquez 2011), and the UK (Brown 2001), and two were performed in an international general medical journal published in Croatia (Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006). Participants included undergraduate students from different disciplines, such as psychology, humanities, communication and entrepreneurship (10 studies: Ballard 2013; Brown 2001; Compton 2008; Dee 2012; Landau 2002; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011), medical students (one study; Roberts 2007), graduate students in graduate students in physical, biological, engineering and social science fields (Rose 1998), and scientists/journal authors (three studies: Aggarwal 2011; Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006). The sample size ranged from 58 to 1462 participants (median 211, interquartile range (IQR) 91 to 398). Funding was reported for five out of the 15 randomized controlled trials; of the 10 studies without stated funding, one reported that the course was developed by a spin‐off company. Interventions were related to plagiarism, research ethics courses and journal authorship.

In studies related to plagiarism, the comparisons included inoculation of educational statements about plagiarism in teaching material versus no intervention (Brown 2001), use of Turnitin in preventing plagiarism (Ballard 2013; Newton 2014), fear‐based, guilt‐based and reason‐based messages versus no intervention (Compton 2008), online tutorial on understanding and avoiding plagiarism versus no intervention (Dee 2012), plagiarism detection exercise with feedback, examples or their combination versus no intervention (Landau 2002), direct lecture or student‐centred, practical instruction on plagiarism versus standard teaching (Moniz 2008), in‐class tutorial on plagiarism prevention versus no instruction (Risquez 2011), composite intervention of instruction and homework on plagiarism versus standard teaching on citations and referencing (Schuetze 2004), and brief paraphrasing instruction versus no intervention (Youmans 2011). The studies assessed a variety of outcomes (median of 2 per study, IQR 1 to 3).

Studies on plagiarism mostly investigated the effects of intervention on students' knowledge and attitudes toward plagiarism and its prevalence and prevention, as well as the extent of plagiarism in submitted student works (Ballard 2013; Brown 2001; Compton 2008; Dee 2012; Landau 2002; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011).

Two studies investigated the effects of research ethics courses, one comparing an online versus on‐site course and assessing the knowledge at the end of the course and three months after the course (Aggarwal 2011), and the other comparing criteria‐oriented and participant‐oriented teaching on evaluating the ethical soundness of research on humans versus no ethics instruction, assessing medical student's rating of the significance of ethical problems and their attitudes towards ethical conduct of clinical research (Roberts 2007). One study investigated the impact of authorship policies on students' judgements of authorship in graduate student‐professor collaboration (Rose 1998). Finally, two studies in the same general medical journal investigated satisfaction of authorship criteria from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) in different situations of authorship declaration: one study compared a categorical or instructional declaration form versus an open‐ended form for authorship declaration (Marušić 2006), and the other compared a binary (yes/no) to an ordinal rating scale of authorship contributions (Ivaniš 2008). In both studies the reporting outcome was the number of authors satisfying ICMJE authorship criteria.

Non‐randomized studies

Sixteen studies had other study design types: nine were controlled before‐and‐after studies involving 2293 participants (Arnott 2008; Chertok 2014; Clarkeburn 2002; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Hull 1994; May 2013; Strohmetz 1992; Walker 2008), four were non‐equivalent controlled studies with a historical control involving 1897 participants (Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Marshall 2011; Rolfe 2011), one was a non‐equivalent controlled study with a post‐test only (Chao 2009) (116 participants) and two were non‐equivalent controlled with pre‐ and post‐test for the intervention group and post‐test for the control group, involving 108 participants (Barry 2006; Kose 2011).

One study was presented in two published articles (Bilić‐Zulle 2008). The non‐randomized studies took place mostly in the USA (11 studies: Arnott 2008; Barry 2006; Belter 2009; Chao 2009; Chertok 2014; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Hull 1994; May 2013; Strohmetz 1992; Walker 2008), two were performed in the UK (Clarkeburn 2002; Marshall 2011; Rolfe 2011), and one each in Croatia (Bilić‐Zulle 2008) and Turkey (Kose 2011). Participants were mostly undergraduate students, predominantly from psychology (11 studies: Aggarwal 2011; Barry 2006; Belter 2009; Chao 2009; Clarkeburn 2002; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Kose 2011; Rolfe 2011; Strohmetz 1992; Walker 2008); one study involved medical students (Bilić‐Zulle 2008), one study involved health students (Chertok 2014), three involved postgraduate students, including masters degree students (Hull 1994; Marshall 2011; Rose 1998), and one had a mixture of undergraduate and postgraduate students (May 2013). The sample size ranged from 36 to 1085 participants (median 146, IQR 65 to 385.5). Funding was reported by six out of 16 studies. Interventions included prevention of plagiarism (10 studies) and research ethics training (six studies).

Plagiarism comparisons included different forms of paraphrasing exercises versus standard instruction on plagiarism (Barry 2006; Chao 2009; Chertok 2014; Kose 2011; Marshall 2011; Rolfe 2011; Walker 2008), as well as instructions on plagiarism and its prevention versus no intervention (Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Estow 2011). Research ethics training comparisons included dialogue‐based computer tutoring systems versus standard teaching (Arnott 2008), ethics discussion embedded into science courses versus no intervention (Clarkeburn 2002), or embedded ethics training or stand‐alone ethics training versus no ethics instruction (May 2013), ethics‐enhanced discussions versus standard ethic course (Fisher 1997), research ethics course versus no intervention (Hull 1994), and role‐playing in research ethics training versus no intervention (Strohmetz 1992).

The studies assessed different outcomes (median of 1 per study, 95% CI 1 to 2.5). In studies on plagiarism, the outcomes were mostly some form of estimation of plagiarism in submitted student work (Barry 2006; Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Chao 2009; Kose 2011; Marshall 2011; Rolfe 2011; Walker 2008), or students' knowledge about and perceptions of plagiarism (Barry 2006; Chertok 2014; Estow 2011). Interventions in research ethics training assessed knowledge (Aggarwal 2011; Fisher 1997; May 2013), moral reasoning or socio‐moral reflection (Clarkeburn 2002; Hull 1994; May 2013), ethical sensitivity (Clarkeburn 2002; Fisher 1997), or assessment of research study utility or cost in relation to ethics (Strohmetz 1992).

Five out of 31 studies also assessed satisfaction with or experience of the intervention (Aggarwal 2011; Dee 2012; Kose 2011; Moniz 2008; Rolfe 2011).

Excluded studies

We excluded studies described in 13 articles: eight did not have an adequate control group (Ali 2014; Bagdasarov 2013; Harkrider 2012; Kligyte 2008; McDonalds 2010; Mumford 2008; Powell 2007; Vallero 2007), two were on professional or academic ethics (excluding plagiarism) and not research ethics/integrity (Goldie 2001; Gurung 2012; May 2014), and two did not include testing before the intervention (Hren 2007; Pollock 1995).

Risk of bias in included studies

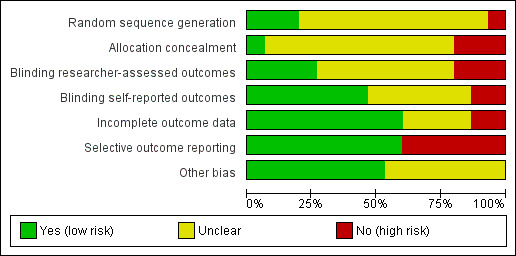

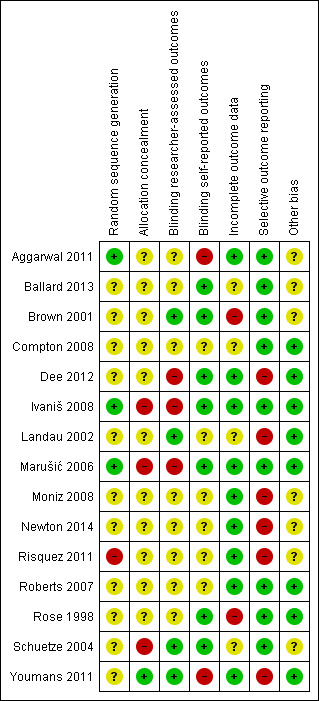

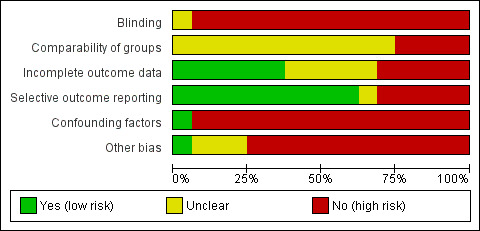

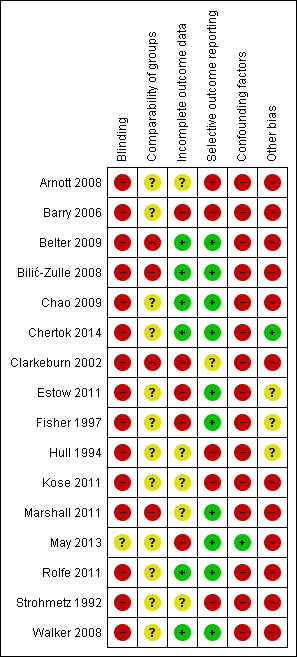

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for illustration of the risk of bias rating for each study and across studies for each domain for randomized studies and Figure 4 and Figure 5 for non‐randomized studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included randomized studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included randomized study.

4.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included non‐randomized studies.

5.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included non‐randomized study.

Allocation

A. Randomized studies

Random sequence generation

Only three included randomized studies had a properly conducted and described random sequence generation procedure (Aggarwal 2011;Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006). Most other studies failed to describe the procedure and just mentioned that participants were randomly assigned (Ballard 2013; Compton 2008; Landau 2002; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Roberts 2007; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011). One study described the procedure as block randomization with pairing on baseline traits, which we judged to be of insufficient clarity (Dee 2012). Another study distributed the intervention and control booklets from a "randomized pile", without explaining how the pile was randomized (Brown 2001). In one study, some intervention groups were assigned randomly and some non‐randomly, resulting in a high risk of bias in this domain (Risquez 2011).

Allocation concealment

No study described an attempt to conceal the allocation sequence. In one case, the selection of participants inferred that the allocation sequence would not be known to the researchers (Youmans 2011). In two randomized controlled trials, authors of this review who had participated in the included study confirmed that there was no allocation concealment, so we rated the risk of bias for these studies as high (Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006). For another study, it was clear from the report that no allocation concealment was attempted (Schuetze 2004). Although the risk of bias in this domain for all other studies had to be marked as unclear due to lack of detail provided in the reports, it seems likely that the actual risk of bias in this domain was high for all studies.

Blinding

A. Randomized studies

Researchers or outcome assessors were described as being blinded in four randomized controlled trials (Brown 2001; Landau 2002; Schuetze 2004; Youmans 2011), and participants were blinded in seven studies (Ballard 2013; Brown 2001; Dee 2012; Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004). Some studies either explicitly stated that there was no blinding of researchers (Dee 2012; Marušić 2006) or participants (Youmans 2011), or it was clear from the report that there was no blinding of researchers (Aggarwal 2011; Ivaniš 2008) or study participants (Aggarwal 2011). The rest of the studies were reported in insufficient detail to discern whether the researchers (Rose 1998), participants (Landau 2002), or both researchers and participants (Compton 2008; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Roberts 2007), were blinded.

B. Non‐randomized studies

In all but one included non‐randomized study there was no active attempt by the researchers to blind the participants or outcome assessors, so risk of bias in this domain had to be judged as high. Participants were reportedly blind to the research hypothesis in only one study, but there was no description of how blinding was achieved, so we judged the risk of bias for this study to be unclear (May 2013). However, in many cases the study design was such that participants were probably not aware that there was another intervention or control group or even that they were participating in a study, so the effect of non‐blinding was probably marginal.

Incomplete outcome data

A. Randomized studies

In most of the randomized controlled trials the attrition was small and we judged the risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data to be low (Aggarwal 2011; Brown 2001; Dee 2012; Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Roberts 2007; Youmans 2011). The low attrition rate could in many cases be ascribed to the study design, such as when interventions were associated with mandatory courses that students had to complete in order to earn their grades. Data on the number of participants were reported insufficiently or inconsistently in four studies (Ballard 2013; Compton 2008; Landau 2002; Schuetze 2004), so the risk of bias in this domain had to be judged as unclear. In one study the response rate was low, with a high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data (Rose 1998).

B. Non‐randomized studies ‐ incomplete outcome data

In six non‐randomized studies the attrition was non‐existent or very small (Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Chao 2009; Chertok 2014; Rolfe 2011; Walker 2008). In another five studies the risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data was unclear, as the attrition was not clearly reported (Hull 1994; Kose 2011; Marshall 2011; Strohmetz 1992), or there were some unexplained imbalances in attrition rates between the study arms (Arnott 2008). A high risk of bias due to a considerable attrition rate was present in five studies (Barry 2006; Clarkeburn 2002; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; May 2013), although in one study there was an attempt to analyse and explain such high attrition rates (May 2013).

Selective reporting

A. Randomized studies

All outcomes were adequately reported in most of the included randomized controlled trials (Aggarwal 2011; Ballard 2013; Brown 2001; Compton 2008; Ivaniš 2008; Marušić 2006; Roberts 2007; Rose 1998; Schuetze 2004). In one study only results of statistical analyses were reported, without absolute numbers (Dee 2012). We judged five studies to have a high risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting, as one or more outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and could not be entered in a meta‐analysis. In one of those studies, means were presented without standard deviations, non‐significant results were not reported, and the results for one of the outcomes was presented only for all participants and not for each studied group (Landau 2002). One study failed to report the numerical results altogether (Moniz 2008), and in another means were reported without standard deviations (Risquez 2011). Two studies did not report the number of participants per group (Newton 2014; Youmans 2011), and one of them did not report non‐significant outcomes (Newton 2014).

B. Non‐randomized studies

In 10 included non‐randomized studies all outcomes were adequately reported (Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Chao 2009; Chertok 2014; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Marshall 2011; May 2013; Rolfe 2011; Walker 2008). In six studies, we judged the risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting to be high. Three of these studies only reported results of statistical analyses without providing scores by study group (Arnott 2008; Barry 2006; Strohmetz 1992), one reported only means without standard deviations (Hull 1994), one did not fully report all of the outcomes (Clarkeburn 2002), and one reported results only as percentages and provided ranges without medians (Kose 2011).

Other potential sources of bias

A. Randomized studies

We identified no further source of bias in seven randomized controlled trials (Compton 2008; Dee 2012; Ivaniš 2008; Landau 2002; Marušić 2006; Roberts 2007; Rose 1998; Youmans 2011). The outcome measurement instrument had not been validated (or was only partially validated) in six studies (Aggarwal 2011; Brown 2001; Moniz 2008; Newton 2014; Risquez 2011; Schuetze 2004). Course attendance rate was not reported in two studies (Aggarwal 2011; Ballard 2013), and there was a risk of contamination between the intervention and control groups in two studies (Ballard 2013; Schuetze 2004). In two studies there was an unclear or questionable baseline comparability between the study arms due to the units of randomization (Moniz 2008), or inadequate randomization procedure (Risquez 2011). We judged the risk of bias to be unclear for all studies in regard to other possible sources of bias.

B. Non‐randomized studies

Comparability of groups

Comparability of groups was unclear in 13 out of 16 non‐randomized studies (Arnott 2008; Barry 2006; Chao 2009; Chertok 2014; Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Hull 1994; Kose 2011; May 2013; Rolfe 2011; Strohmetz 1992; Walker 2008). There was either no comparison of demographic characteristics between the groups, or the number of compared characteristics was very limited. Often the participants were recruited from different study programmes, years or even universities. In some cases these differences were such that we judged the risk of bias due to questionable comparability of groups to be high (Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Clarkeburn 2002; Marshall 2011). Risk of bias under this domain was considerable for all the included non‐randomized studies, as baseline differences between the study groups were likely even among the studies whose risk of bias had to be judged as unclear due to insufficient information provided in the report.

Confounding factors

All but one of the non‐randomized studies failed to adequately control for confounding factors and we judged them to have a high risk of bias under this domain. A single study reported basic demographic characteristics of participants and used them in a regression analysis (May 2013). Although some other studies collected and reported basic demographic characteristics, none of them actually used the data to control for confounding factors.

Other sources of bias

While for a single study we could not identify other sources of bias (Chertok 2014), most of the non‐randomized studies had a high risk of bias related to other reasons, such as unvalidated outcome measurement instrument (Arnott 2008; Barry 2006; Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Chao 2009; Kose 2011; Rolfe 2011; Strohmetz 1992), poor or unknown attendance rate (Arnott 2008; Barry 2006; Clarkeburn 2002; Kose 2011; Marshall 2011; May 2013), interventions provided by different instructors or in different settings (Arnott 2008; Belter 2009; Chao 2009; Marshall 2011; May 2013; Strohmetz 1992), potentially biased selection of participants in study arms (Arnott 2008; May 2013), failure to conduct both pre‐test and post‐test of all the participants (Barry 2006; Belter 2009; Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Kose 2011; Rolfe 2011; Walker 2008), possible contamination between the groups (Kose 2011), and the use of a historical control (Bilić‐Zulle 2008; Marshall 2011).

In three studies there were no other possible sources of bias except unvalidated outcome measurement instruments and/or unknown attendance rate (Estow 2011; Fisher 1997; Hull 1994). For those studies, we rated the risk of bias under this domain as unclear, rather than high.

Effect of methods

We assessed the effects of interventions for research integrity using outcome classification levels according to the Kirkpatrick/Barr typology (Barr 2000; Kirkpatrick 1967).

Primary outcomes

1. Organizational change attributable to the intervention

No studies tested interventions directed to organizational changes for preventing or fostering research integrity.

2. Behavioural change

One randomized controlled trial evaluated participants' intentions for a behavioural change (level 3a outcome) regarding research ethics (Rose 1998), showing that male graduate students who were aware of authorship policy when deciding on a case of authorship problems in student‐faculty collaboration were more likely to report the professor who took first authorship on a student dissertation than students who were not informed about the policy. Female students aware of the policy were less likely to report such a case than those who were not aware of the policy. The awareness of policies had no effect on students' estimates of effectiveness or consequences of such actions.

Sixteen studies evaluated 21 different outcomes of actual behavioural change (level 3b outcome), related to research ethics/integrity interventions (in two studies) or plagiarism (in 14 studies). The results of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

1. Effects on behavioural change.

| Study (design) | Participants | Intervention (I) | Control (C) | Outcomes (O) | Results (I versus C, or I1 versus I2 versus In versus C) | Significant difference |

| Intention for change: | ||||||

| Rose 1998 (RCT) | Graduate students | I: Presence of authorship policy when judging authorship disputes in student‐faculty collaboration | C: No authorship policy | Likelihood, effectiveness and consequences (mean score on a scale from 1 – low to 7 – very likely) of reporting a problem with authorship arrangement (in 3 vignettes with professor's first authorship: 1 ‐ professor idea, student work; 2 ‐ student idea, professor work; 3 ‐ student's dissertation): a) talking to a dean b) filing a complaint c) contacting a journal |

Men I: 2.80 (SE 0.21) versus C: 1.89 (SE 0.22), F(1,156) = 9.08, P value < 0.01 Women I: 1.94 (SE 0.29) versus C: 2.79 (SE 0.22) for vignette where professor is the first author on student's thesis: No difference for effectiveness and consequences for any vignette |

+ for men – for women |

| Actual change ‐ research integrity | ||||||

| Marušić 2006 (RCT) | Journal authors | I1: Categorical form for declaring authorship contribution I2: Instructional form for declaring authorship contribution |

C (I3): Open‐ended form for declaring authorship contribution | Number of authors not satisfying authorship criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) | I1: 68.7 versus I2: 32.5 versus I3: 62.6; I3 versus I1 z = ‐3.034, P value = 0.002; I3 versus I2 z = ‐2.884, P value = 0.004, no diff. I2 versus I3 (z = 0.3315, P value = 0.74) | + I2 |

| Ivaniš 2008 (RCT) | Journal authors | I1: Ordinal rating of authorship contributions (on a scale from 0 = none to 4 = full) | C (I2): Binary rating of authorship contribution | Per cent of authors satisfying authorship criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) | I1: 76 versus I2: 39, P value < 0.05 | + for I1 |

| Actual change ‐ plagiarism prevention | ||||||

| Ballard 2013 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I1: Academic integrity module + Turnitin submission I2: Academic integrity module + no Turnitin submission I3: No academic integrity module + Turnitin submission |

C: No instruction, no Turnitin submission | Mean Turnitin similarity score (form 0 to 100) | I1: 11.32 (SD 10.48) versus I2: 12.24 (SD 15.09) versus I3: 15.42 (SD 15.85) versus C: 14.78 (SD 14.40); F(1,92) = 0.072, MSE = 193.26, P value = 0.789, η2 = 0.001 | ‐ |

| Landau 2002 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I1: Instruction about plagiarism with feedback I2: Instruction about plagiarism with examples I3: Instruction about plagiarism with examples and feedback |

C: No instruction | Frequency (mean no.) of using: a) overlapping words b) 2‐word strings c) 3‐word strings in assignments |

a) I1: 21.4 versus I2: 17.2 versus I3: 17.5 versus C: 19.0, F(1,90) = 6.86, P value = 0.01, MSE = 28.12, η2 = 0.07 b) I1: 8.3 versus I2: 4.1 versus I3: 4.9 versus C 8.3, F(1,90) = 12.39, P value = 0.01, MSE = 27.14, η2 = 0.12 c) I1: 4.3 versus I2: 1.4, I3: 1.6 versus C: 4.1, F(1,90) = 11.13, P value = 0.01, MSE = 15,27, η2 = 0.11 |

+ for I2 |

| Newton 2014 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I: Training session on paraphrasing, patch‐writing and plagiarism | C: No instruction | Quality of paraphrasing in a written assignment (average score, marked by 2 assessors, score range not provided): a) referencing b) patch‐writing c) plagiarism |

a) I: 3.49 (SE 0.19) versus C: 2.54 (SE 0.20), F(1,116) = 11.7, P value < 0.01, η2 = 0.09 b) I: 4.30 (SE 0.16) versus C: 3.77 (SE 0.17), F(1,116) = 5.63, P value < 0.05, η2 = 0.05 c) I: 4.93 (SE 0.10) versus C: 4.55 (SE 0.11), F(1,116) = 6.97, P value < 0.01, η2 = 0.06 |

+ |

| Risquez 2011 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I: 1‐hour in‐class tutorial on plagiarism prevention | C: No intervention – regular class | Reported engagement (mean score, scale from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree) in: a) copying text and using it without citations b) using internet to copy text and using it without citations c) using internet to purchase a paper and present as own |

a) I: 1.38 versus C: 1.53, t = ‐1.610, P value > 0.05 b) I: 1.39 versus C: 1.37, t = 0.187, P value > 0.05 c) I: 1.10 versus C: 1.00, t = 2.080, P value < 0.05 |

+ for c (worse behaviour) |

| Schuetze 2004 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I: Homework assignment to reduce citation problems | C: Standard teaching | Mean no. citation problems in students' term papers | I: 2.57 (SD 1.22) versus C: 3.87 (SD 1.11), t(73) = ‐4.57, P value < 0.01 | + |

| Youmans 2011 | Undergraduate students | I1: Requirement to use citation in writing assignment + warning that Turnitin will be used I2: Requirement to use citation in writing assignment + no warning that Turnitin will be used I3: No requirement to use citation in writing assignment + warning that Turnitin will be used |

C: No requirement to use citation in writing assignment + no warning that Turnitin will be used | Mean per cent text overlap in Turnitin report | I1 versus I2 versus I3 versus C F(1,85) = 0.96, not significant Requirement to use citations versus no requirement: 10.26% (SD 5.66%) versus 4.76% (SD 7.30%), F(1,85) = 8.35, P value < 0.001, η2 = 0.17 Warning versus no warning on use of Turnitin: 7.59% (SD 7.17%) versus 7.29% (SD 7.10), F(1,85) = 2.08, not significant |

– |

| Estow 2011 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Plagiarism themes and assignments embedded in a methods and statistics course | C: Non‐intervention course | Quality of paraphrasing in course assignments (mean score, scale from 1 – direct copying of a significant proportion of original without quotation marks to 4 – good paraphrasing) | I: pretest 2.54 (SD 0.86) post‐test 3.32 (SD 0.86) versus C: pretest 3.12 (SD 0.78) post‐test 2.83 (SD 0.81); t(41) = 1.55, P value = 0.13 | – |

| Walker 2008 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Paraphrasing training to avoid plagiarism | C: No training | Post‐test mean score of extent of plagiarism in written course assignments (lower score, less plagiarism) | I: 1.75 (SD 7.49) versus C: 4.56 (SD 6.52), P value < 0.01 | + |

| Chao 2009 (non‐equivalent CBA) | Undergraduate students | Training in plagiarism prevention, involving: I1: instructions and examples I2: discussion and student practice work |

C: Warning about plagiarism, no training | Percentage of students with assignments containing some amount of plagiarism | I1: 29% versus I2: 36% versus C: 55% x22 = 5.139, P value = 0.077 | – |

| Mean percentage plagiarized text in the course assignments | I1: 2.29% versus I2: 1.9% versus C: 5.45%, F(2,113) = 3.399, P value = 0.037, post hoc Tukey test for I2 versus C P value = 0.46 | + for I2 | ||||

|

Kose 2011 (non‐equivalent CBA) |

Undergraduate students | I: Use of Turnitin in practising avoiding plagiarism in academic writing | C: No intervention | Range of percentage plagiarism level in submitted essays | I: pretest 8% to 22% post‐test 0% to 12% versus C: post‐test 2% to 22% | + |

|

Belter 2009 (non‐equivalent CBA) |

Undergraduate students | C: Online module on research integrity within a course | C: No module on research integrity | Percentage plagiarized course papers | I: 6.5 versus C: 25.8, x21 = 18.39, P value < 0.001 | + |

|

Bilić‐Zulle 2008 (non‐equivalent CBA) |

Undergraduate students | I1: Warning that plagiarism is forbidden I2: Warning that student essays will be examined by plagiarism detection software and that plagiarism will be penalized |

C: No intervention | Median (5 to 95 percentile) proportion of plagiarized text in essays | I1: 21 (0 to 87) versus I2: 2 (0 to 20) versus C: 17 (0 to 89); H = 84.64, P value < 0.001; post hoc test P value < 0.05 for I2 versus I1 and C | + for I2 |

|

Marshall 2011 (non‐equivalent CBA) |

Students | I1: Warning about plagiarism (year 2) I2: Training in avoiding plagiarism (year 3 and 4) |

C: No intervention (year 1) | Number of plagiarism occurrences | I2: 0.3% versus I1 and C: 1.9%, P value = 0.013 | + |

| Overall percentage text match in year 1 to 4 for assignments: a) Critical appraisal b) Health information c) Principles and practice of HTA |

a) I2: 20.8 and 18.1 versus I1: 37.4 versus C: 28.5 b) I2: 23.6 and 20.8 versus I1: 28.0 versus C: 30.3 c) I2: 19.5 and 11.7 versus I1: 21.6 |

+ for I2 | ||||

|

Rolfe 2011 (non‐equivalent CBA) |

Undergraduate students | I: Instruction and feedback based on a plagiarism detection software | C: No intervention | Percentage of students who plagiarized | I: 80 versus C: 72 | – |

| Percentage of submissions with plagiarism due to poor paraphrasing | I: 9 versus C: 28, P value < 0.05 | + | ||||

| Percentage of submissions with plagiarism due to poor paraphrasing and failure to acknowledge source: a) plagiarism without citation b) plagiarism without reference c) plagiarism with no citation or reference |

a) I: 30 versus C: 46 b) I: 16 versus C: 8 c) I: 33 versus C: 16 |

– | ||||

| Percentage of submission with lack of citations | 59 versus 32, P value < 0.05 | + (intervention worse) |

CBA: controlled before‐and‐after study ICMJE: International Committee of Medical Journal Editors HTA: health techology assesment MSE: mean standard error RCT: randomized controlled trial SD: standard deviation SE: standard error

a) Research ethics/integrity

Two randomized controlled trials in a single general medical journal evaluated whether changes in the authorship declaration form could influence authorship qualifications according to the standard definition of authorship in biomedicine from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Fewer authors completing the instructional declaration form (which instructed the respondents about the number of contributions needed to satisfy ICMJE authorship criteria) failed to satisfy ICMJE criteria in comparison to authors who either answered an open‐ended question about their contributions or had to pick from a list of predefined categories of contributions (Marušić 2006). When authors chose their contributions from a list of contribution categories, more of them satisfied the ICMJE authorship criteria when they could indicate the extent of their contribution than when they had to provide a binary (yes‐no) response (Ivaniš 2008).

b) Plagiarism prevention

In a randomized controlled trial undergraduate students who received instruction about plagiarism definition and examples of a plagiarized text used fewer overlapping words and two‐word or three‐word strings in their assignments than students receiving feedback about why the text overlap was considered plagiarism or both the example and the feedback (Landau 2002). In another randomized controlled trial, a one‐hour in‐class tutorial to undergraduate students on plagiarism prevention was not effective in comparison to no intervention in decreasing reported engagement in plagiarism (Risquez 2011). In another randomized controlled trial, undergraduate students who had to do a homework assignment of recognizing plagiarism after receiving a 30‐minute presentation and handouts with plagiarism definition and citation guidelines had fewer citation problems in their term papers than students without the homework assignment (Schuetze 2004). In the Newton 2014 randomized controlled trial, a short training session on paraphrasing, patch‐writing and plagiarism increased the performance of students in assignment writing, as measured by referencing source material, avoiding patch‐writing and avoiding plagiarism in comparison to no intervention. In the Ballard 2013 randomized controlled trial, an interactive academic integrity module addressing plagiarism and paraphrasing, with or without examples from Turnitin text‐matching software, was not successful in decreasing similarity index in course assignments by undergraduate students in comparison to no intervention. In the Youmans 2011 randomized controlled trial, warning about the use of Turnitin did not have an effect on plagiarism level in undergraduate students' writing assignments, regardless of whether they were instructed to cite sources or if citing was not mandatory.

In a controlled before‐and‐after study (Estow 2011), undergraduate students from a methods and statistics course with embedded plagiarism themes and assignments did not fare better than students from the control course in the quality of paraphrasing in their written assignments. In the Walker 2008 study, paraphrasing training to avoid plagiarism decreased the extent of plagiarism in the students' written course assignments compared to no training.

Two studies used a modification of the controlled before‐and‐after study design, with the control group of undergraduate students receiving post‐intervention testing only. In the Chao 2009 study, compared to the no intervention group that was tasked with writing a report and warned about plagiarism, active training in preventing plagiarism involving extensive discussion and student practice work was more effective than active training involving instructions and examples in decreasing the proportion of students who had some extent of plagiarized course assignments. However, none of the interventions was effective in decreasing the mean proportion of plagiarized text in the assignments. In the Kose 2011 study, undergraduate students using Turnitin plagiarism detection software in writing their course works had a lower level of plagiarism in submitted essays than students without experience with Turnitin.

Four studies used a historical control in their before‐and‐after study design. Undergraduate students who completed an online academic integrity module during a course had fewer instances of plagiarism in their course papers than students attending a regular course (Belter 2009). Undergraduate students who were warned during the course that their essays would be examined for plagiarism and that plagiarism would be penalized had less plagiarized text in their essays than students who either received no warning or received an explanation about plagiarism and how to avoid it (Bilić‐Zulle 2008). Similarly, warning about the use of Turnitin for checking students' assignments and additional interactive seminars on plagiarism decreased the number of plagiarism occurrences and the amount of plagiarized text (Marshall 2011). Finally, use of Turnitin feedback to help students revise their course essays before final submission did not decrease the number the number of students who plagiarized compared to the student group without intervention. The number of submissions with plagiarism due to poor paraphrasing decreased, but not due to other causes (Rolfe 2011). Actually, plagiarism due to failure to acknowledge sources, measured as the lack of citations in the text, increased in the intervention group.

3. Acquisition of knowledge and/or skills related to responsible conduct of research

Ten studies evaluated 12 different outcomes at this level, related to research ethics training (in three studies) or plagiarism (in six studies). The results of individual studies are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

2. Effects on knowledge and/or skills related to research ethics/integrity.

| Study (design) | Participants | Intervention (I) | Control (C) | Outcomes (O) | Results | Significant difference |

| Aggarwal 2011 (RCT) | Researchers | I1: Research ethics course delivered online | I2 (C): Research ethics course delivered on site | Knowledge (percentage of correct responses; median, range): a) pre‐course b) immediately after the course c) 3 months after the course |

a) I1: 62 (40 to 89) versus I2: 69 (36 to 39), P value = 0.07 b) I1: 77 (43 to 95) versus I2: 82 (44 to 93), P value = 0.02 c) I1: 80 (‐15 to 34) versus I2: 83 (54 to 98), P value = 0.69 P value < 0.005 versus baseline for I1 and I2 |

+ for I2 in b) |

| Difference in knowledge gain from baseline to 3 months (percentage of correct responses; median, range) | I1: 13% (‐15 to 34%) versus I2: 17% (0 to 41%) P value = 0.14 |

– | ||||

| Arnott 2008 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Dialogue‐based computer tutoring system on research methodology | C: Standard teaching | Post‐test‐pretest gain (main) in the score on a written knowledge test (30 questions) | I: 10.9% (SD 11.8) versus C: 3% (SD 9.4%); effect size 0.75 SDs; F(1,94) = 5.99, P value = 0.016, η2 = 0.06 | + |

| Fisher 1997 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Enhanced ethics instruction | C: Standard instruction | Knowledge of research ethics procedures and ability to weigh scientific responsibility and participant rights and welfare (mean score (0 to 5) on a written essay) | I: Pretest 1.69 (SD 1.00), post‐test 2.13 (SD 1.03) versus C: 1.72 (SD 0.92), post‐test 1.79 (SD 1.20); critical difference 0.28, P value < 0.01, effect size for pretest‐post‐test difference d = 0.44 for intervention and d = 0.05 for control | + |

CBA: controlled before‐and‐after study RCT: randomized controlled trial SD: standard deviation

3. Effects on knowledge and/or skills related to plagiarism.

| Study (design) | Participants | Intervention (I) | Control (C) | Outcomes (O) | Results | Significant difference |

| Landau 2002 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I1: Instruction about plagiarism with feedback I2: Instruction about plagiarism with examples I3: Instruction about plagiarism with examples and feedback |

C: No instruction | Plagiarism Knowledge Survey mean score* (lower scores indicated better knowledge) | Pretest I1: 8.00 versus I2: 7.84 versus I3: 7.60 versus C: 8.28, post‐test I1: 6.75 versus I2: 7.09 versus I3: 6.95 versus C: 7.99; F(1,90) = 4.41, P value = 0.04, MSE = 2.17, η2 = 0.05 | + |

| Moniz 2008 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | Enhanced instruction on plagiarism: I1: Direct I2: Student‐centred |

C: Standard teaching on plagiarism | Knowledge and understanding of plagiarism | No effect, raw data or statistical analysis not presented | – |

| Newton 2014 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I: Training session on paraphrasing, patch‐writing and plagiarism | C: No intervention | Knowledge about in‐text referencing (average score from 0 to 5) | I: 3.66 (SE 0.13) versus C: 3.22 (SE 0.13), F(1,116) = 5.75, P value < 0.05, η2 = 0.05 | + |

| Schuetze 2004 (RCT) | Undergraduate students | I: Homework assignment to reduce citation problems | C: Standard teaching | Score on knowledge test on plagiarism (mean score, max 5) | I: 3.51 (SD 1.39) versus C: 3.85 (SD 1.01); t(74) = 1.20, P value = 0.24 | – |

| Chertok 2014 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Course on academic integrity | C: No intervention | Score on 13 true/false questions on knowledge about plagiarism (mean no. correct answers) | Pretest I: 10.8 (SD 1.7) versus C: 10.5 (SD 1.6) Post‐test I: 10. 8 (SD 1.9) versus C: 10.1 (SD 1.8) No difference in change pre‐test to post‐test (P value = 0.09). |

– |

| Estow 2011 (CBA) | Undergraduate students | I: Plagiarism themes and assignments embedded in a methods and statistics course | C: Non‐intervention course | Pretest‐post‐test mean difference in identifying plagiarism in test examples (no. sentences correctly identified as plagiarism) | 1.52 (SD 0.98) to 2.59 (SD 0.75) versus 1.94 (SD 0.43) to 2.06 (SD 0.66); F(1,42 = 9.19, P value = 0.004, η2 = 0.1.8 | + |

| Pretest‐post‐test mean difference in number of identified strategies to avoid plagiarism (no. listed strategies) | 2.44 (SD 0.93) to 2.69 (SD 0.60) versus 2.63 (SD 1.18) to 2.00 (SD 0.73); F(1,41) = 5.86, P value = 0.02, η2 = 0.13 |

+ | ||||

| Barry 2006 (CS) | Undergraduate students | I: Assignments in paraphrasing quotes from publications | C: No intervention | Pretest‐post‐test mean difference in score on plagiarism definition test (scale not provided) | 2.14 (SD 0.81) to 3.23 (SD 0.99) versus (pretest not measured) to 2.33 (SD 1.08); t(62) = 3.45, P value = 0.001 for post‐test‐control comparison; pretest‐post‐test comparison d = 1.26, post‐test‐control comparison d = 0.86 | + |

CBA: controlled before‐and‐after study CS: controlled study MSE: mean standard error RCT: randomized controlled trial SD: standard deviation SE: standard error

a) Research ethics/integrity