Abstract

This chapter gives a summary of the economic development of Hong Kong. Since its early colonial days, Hong Kong has been an open port serving China and the international community. Reexport trade was the traditional advantage until 1949, when China adopted a closed-door policy. Industrialization since the 1950s has brought growth and expansion, taking advantage of the low cost of labor and the British legal system. However, the situation changed after the early 1980s, partly because of low costs in China pulled investment from Hong Kong, and the post-1997 political uncertainty also resulted in short-term investment behavior. Economic overheating in the mid-1990s led to severe recession after the Asian financial crisis. Economic restructuring has been slow since 1997. Economic narrowness with concentration in real estate development and finance, together with an increase in welfare spending, lowered competitiveness. Economic integration with China would best be based on comparative advantage, with “win, win” outcomes.

Keywords: Laissez-faire, short-term investment behavior, comparative advantage, Hong Kong

I. Introduction

It has been observed that many former British colonies performed poorly after gaining independence. Whether the Hong Kong economy would be an exception to other former British colonies was yet to be seen, as Hong Kong was not given independence but sovereignty reversion to China in 1997. There were several differences between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. Hong Kong comprised mainly people from Southern China, and ethnic Cantonese are usually entrepreneurial and keen to start businesses rather than seek assistance from the government. The preference on self-reliance and enterprising behavior among traditional Chinese had further implications for economic activity. Economic difficulties tended to be localized, and obtaining assistance from family or relatives in difficult times was a more common practice than seeking welfare assistance in the early colonial days in Hong Kong.

During the 155 years of British colonialism, Hong Kong was transformed from a “barren rock” to a flamboyant immigration center, industrial and export center, international banking and financial center. The extent of economic openness, together with the well-established and rooted British institutions, made the Hong Kong economy acceptable to the international community. The “business as usual” nature meant that the economy was influenced by the economic scene of the world, taking advantage of economic booms, but also suffering from economic crises. While other former British colonies gained political independence, in Hong Kong the case was a reversion of sovereignty to communist China, which had a different and opposing political and ideological system to that of capitalist Hong Kong.

There are numerous recent studies on the Hong Kong economy, covering different economic areas and the Sino−British Negotiations (Haddon-Cave, 1980; Jao, 1988; Rabushka, 1989; Huang, 2003; Latter, 2007; Mushkat and Mushkat, 2009; Goodstadt, 2013; Ip, 2015). This chapter summarizes the discussion on the Hong Kong economy based on the ideas in Li (2006,2012a)Li (2006)Li (2012a). While the pre-1997 performance was a world record of economic freedom and laissez-faire practices, the focus is on whether the post-1997 period would suffer a similar fate of economic decline as in other former British colonies, or stand up to confront the ideological battle with mainland China. Hong Kong’s post-1997 development would be a unique case in world economic development.

II. Laissez-Faire Policies

The economics adopted by the British colonial government were to keep things simple, meaning that Hong Kong citizens were allowed to conduct their own businesses and the government was “hands-off” in business activities, involved only when necessary. Hong Kong began as a “free port” between mainland China and overseas countries. Immigrants were free to enter, while British types of institutions were gradually introduced, including the rule of law and a business-friendly fiscal policy. The big British businesses were dominant, but local businesses also flourished. The enterprising immigrants formed a key component in the development of Hong Kong. Appropriate infrastructure and public utilities had been developed as the pace of urbanization and population expanded.

The role of the laissez-faire government was to monitor and ensure efficiency. Fiscal consistency and certainty had over the years become an advantage. The growth-led nature of economic development would focus on “supply-side” economics. The high degree of domestic “preparedness” was important in the political economy in Hong Kong. Other laissez-faire practices included the duality in the supply of such public goods as schools, hospitals, and medical centers, housing provision, media, and transportation. The combined economic forces of “supply-side” economics and “duality in supply” produced promising scenarios for foreign investment. Economic opportunities expanded exponentially, and mutual positive-sum outcomes were realized, as both foreign and local businesses benefitted from their activities in Hong Kong.

The high degree of stability in Hong Kong contrasted with the periodic instability in mainland China, resulting in a continuous inflow of enterprising immigrants who came to look for opportunities and alternatives. It was only after the 1960s that border control was instituted as the population in Hong Kong expanded, but there were still periodic floods of immigrants from mainland China. In many ways, the stability and “supply-driven” nature of economic development in Hong Kong was shown to be a better alternative to development in mainland China at various historical periods. Thus, Hong Kong had been serving as a shelter for mainland refugees whenever mainland China was faced with crises and difficulties. This, in itself, would make the enterprising immigrants to act, behave, and conduct activities differently from people in mainland China. The opportunities and alternatives that Hong Kong offered eventually created differences between Hong Kong and mainland China.

The only period when the British colonial government lost control of Hong Kong was the “3 years and 8 months” during the Japanese occupation from December 25, 1941, to the end of the Second World War. The establishment of the communist regime in China in 1949, and the subsequent trade embargo by the western world, had put an end to the reexport trade of Hong Kong. Instead, the migration of Chinese capital to Hong Kong paved the way for industrialization, with labor-intensive manufacturing from the 1950s. Hong Kong also attracted much foreign investment after the end of the Second World War, as world demand for light manufacturing increased. Thus, Hong Kong’s exports increased gradually and labor-intensive manufacturing included wigs, toys, transistor radio, textiles and clothing, plastic flowers, and related products. Electronics production became popular after the 1980s.

In much of the 1950s and 1960s, the colonial government was reluctant to introduce welfare-related policies, arguing that improvements in “supply-side” factors should be the more appropriate prerequisites for development in Hong Kong. Other than the rule of law, the colonial government also introduced professional institutions from Britain so that local students could follow the practice and standards that existed in the United Kingdom. The establishment of the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) on February 15, 1974, was a milestone in lifting Hong Kong to a fully fledged civic society where privileges, vested interests, cronyism, and “backdoor” activities were replaced by transparency, fairness, and equity before the law. Beginning from the mid-1960s, the Hong Kong colonial government began to modernize Hong Kong. Massive “supply-side” developments turned Hong Kong into a modern metropolitan economy. Examples included the construction of industrial towns for low-cost labor supply for industrial plants, urbanization and creation of new towns in the New Territories to cater for the growing population, provision of public housing for low income families and the “sandwich” class, construction of cross-harbor tunnels and underground railways, reclamation of land for residential purposes, and expansion of public health provisions and postsecondary educational institutions.

Laissez-faire noninterventionism based on capitalist market principles, popularly known as “positive noninterventionism,” was the approach adopted by the colonial government in the 1970s, although the provision of water, land use, and road and park construction were entirely controlled by the government. The Hong Kong experience showed that there were numerous advantages in laissez-faire economic principles, typically in the form of a private-led economy, macroeconomic stability and fiscal certainty, indirect support through “supply-side” channels, coupled with a hard-working, enterprising, and disciplined labor force; opportunities and chances of upward mobility were the major outcome of these advantages.

However, there were inadequacies. For example, technological advancement had not been a major concern. Government spending on research and development activities was minimal. Foreign investment related to industrial production either concentrated in labor-intensive manufacturing, or brought along with their own technology. The local businesses comprised mainly small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) which did not promote technology. Nonetheless, the laissez-faire nature permitted Hong Kong to achieve a high level of development, and the flexibility and ability to move along with the international economic community remained the cutting-edge of the Hong Kong economy. Nonetheless, Hong Kong over the decades had developed brand names in several lines of consumer products, especially in clothing, food processing, and beverage industries. Despite the lack in technological advancement, growth in Hong Kong proceeded favorably, diversifying into such areas as finance and business services.

As the British sinologists’ strategy was to ensure Hong Kong’s economic supremacy over the socialist economy in mainland China, the advance economy would serve as a “cushion” for Hong Kong in its post-1997 years. As Hong Kong people were keen on making “money” and economic progress, rising incomes and growth would serve to pacify the political demand for democratic changes. This could be a misunderstanding on the part of the sinologists. Hong Kong had all along been an immigrant city, and many held a “siege mentality” as certainty and stability was not guaranteed. As such, amassing wealth and assets were seen as an “insurance” policy and a source of security and reliance. Should they eventually have to emigrate to another destination as a result of political uncertainty, their economic survival would be assured.

III. Performance Prior to 1997

The rise in incomes and growth in the two decades of the 1960s and 1970s in Hong Kong also led to a rise in the costs of production, thereby eroding Hong Kong’s competitiveness, as discussed in the “pull and push” argument. The opening-up of China in 1978 had profusely influenced the Hong Kong economy. China’s low costs of production attracted investment from Hong Kong. Hence, there emerged a process of “industrial-hollowing” in much of the 1980s and 1990s. Unfortunately, the departed industries were not replenished by new and different kinds of industrial investment to Hong Kong. The “industrial vacuum,” however, was made up for by the rapid expansion in the service sector. Instead of exports of local manufacturing, e.g., reexport business flourished as exports from China used Hong Kong’s port facilities. The “front office, back factory” concept gained popularity as Hong Kong’s rise in producer services (front office) would complement the industrial production (back factory) in mainland China.

Political uncertainty during the Sino–British Negotiation (1982–84) in Hong Kong led to professionals and businesses migrating to other English-speaking Commonwealth countries and the United States. The United Kingdom government was not prepared to allow large numbers of Hong Kong citizens to migrate to Britain. Thus, the colonial government had to deliver policies that would maintain economic vitality in Hong Kong. “Stability and prosperity” had been promoted to maintain the confidence of the Hong Kong people. While there was continuous construction in large infrastructure projects, such as the new international airport and all the related railway constructions, there were various expansions and upgrading of institutions, such as the establishment of the Hospital Authority and additional universities that involved large fiscal capital commitments. There were handsome pay rises and wage increases in all these years, in some years reaching double digit growth rates (Li, 2006, 2012aLi, 2006Li, 2012a). Large increments in salary boosted the employees in the short-term, but the gap in the salary range had increased over time.

The fast increase in salaries and the persistent low interest rates should have promoted inflationary pressures. Indeed, after the late-1980s, high inflation, large salary increases, and low interest rates coexisted and encouraged bank lending. Together with the trend in “industrial-hollowing,” industrialists looked to “investment” that produced higher returns by turning to invest or speculate in stocks and properties, causing a continuous rise in the stock price and property prices. The resulting economic boom produced short-term “stability and prosperity,” but it had long-term unintended consequences. The rising property prices further eroded Hong Kong’s cost competitiveness. Li (2006,2012a)Li (2006)Li (2012a) talked about “short-term investment behavior,” as investors and speculators considered July 1997 as the terminal date when profits and gains would have to be maximized. As investment and speculation in stocks and properties became the most effective route to maximize gains and profits, few investors would consider long-term investment in industries. Such behavior did not help to rescue the process of “industrial-hollowing” in Hong Kong, as people got used to speculation.

Beginning from 1994, a new welfare scheme known as Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) was introduced that substantially enlarged social welfare. While it was fiscally manageable at that time, the widening of the welfare spending took place over two dimensions by enlarging the number of welfare-related items, and spending more on each welfare item. At the same time, the rapid increase in salary tax exemption had effectively narrowed the salary tax base from a V-shape to a T-shape, where different income groups would have to pay salary tax creating a situation where the salary tax burden was shouldered only by the high income earners. Government statistics show that in the fiscal year of 2011–12 the taxpaying population was 1,634,000, while the nontax paying population amounted to 1,971,000. In the case of the salaries tax, the top highest 100,000 tax payers paid 65.9% of the salaries tax, and the cumulated 0.5 million of salary tax payers paid 97.1% of the salaries tax (Treasury Branch, Hong Kong SAR Government). Effectively, the 0.5 million salary tax payers supported the entire population of about 7 million people in Hong Kong. The salary tax burden could further deteriorate when income had fallen and the government would be faced with an I-shape, where little tax could be collected. The change in the welfare policy came in at the wrong time, when Hong Kong experienced an economic boom in the early 1990s. Indeed, fiscal theory argues the contrary, that government spending should contract and shrink at times of economic boom so as to avoid overheating. The colonial government kept increasing its fiscal spending on welfare at times of economic boom, to make the economy look “prosperous.”

One can conclude that the colonial government in the years before 1997, other than the construction of large scale infrastructure projects, basically changed their economic policies from “supply-side” to “demand-side” policies that involved high spending and subsidies. The prolonged low interest rates further discouraged saving on the one hand, and encouraged borrowing to hedge against inflation on the other. The rise in income was based purely on expansion in the nominal economy, while such real activities as industrial production and export of manufactures were shrinking. The coexistence of expansion in nominal economic activities and contraction in real economic activities provided the best combination for the formation of a financial bubble.

The massive shift in the orientation of economic policies was overshadowed as income kept rising literally in a “one-way” direction, but these policies would have numerous drawbacks over time in terms of competitiveness and sustainability. The erosion of economic competitiveness over time could endanger economic sustainability, thereby challenging the Hong Kong economy in regaining its vitality, strength, and diversity. In focusing on “demand-side” factors, industrial output gave way to services. Among the three economic sectors in Hong Kong, services occupied over 90% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while industry occupied less than two digits in GDP, and agriculture’s share in GDP was minimal. While industrial outputs were regarded as tradable goods, many services were regarded as nontradable, thereby reducing the amount of exports from Hong Kong. Many services did not require much skill, and salaries in unskilled service jobs tended to be low, thereby limiting the chances of upward mobility. Indeed, many service jobs had a rather short employment life, as they did not favor aging workers. A shorter employment life would mean a greater chance of seeking welfare and unemployment assistance, should unskilled service workers become unemployed. A generous welfare package would mean more fiscal spending that would work against the long-term sustainability of the Hong Kong economy.

Typical businesses in a “demand-driven” economy include tourism, retail, restaurants, and personal services. However, many of these services are regarded as “derived,” meaning that their survival depends a lot on income trends and business cycles. Once there is a drop in income and growth, the demand for these services immediately falls. In other words, a heavy service-oriented economy tends to be more vulnerable to shocks and crises, especially in a small and open economy with little natural resources. In “supply-driven” economies, economic policies aim to promote employment, job expansion, and upward mobility, and individuals become more progressive economically. On the other hand, economies that pursue “demand-driven” policies concentrate on fiscal spending on welfare and subsidy provisions that ensure a certain level of living standards, but the recipients might not be provided with employment and job possibilities. As such, growth would be unlikely, as welfare spending is merely a transfer payment that is not output-promoting. It is easier to promote “demand-driven” policies than “supply-driven” policies at the individual level, but will not help the economy at the macrolevel. Indeed, once an economy switched from “supply-driven” to “demand-driven” economic policies, it would be difficult for the economy to switch back, because subsidies, once given, cannot possibly be cut.

The reorientation of economic policies in pre-1997 Hong Kong also meant that the Hong Kong economy was geared more to “internal” than “external” issues. The dominance of domestic features and issues meant that the economy might not align closely with the international community. With the high cost of production and low competitiveness, the Hong Kong economy could price itself out of the market. In short, appropriate policies would have to be introduced so that continued economic expansion would be possible.

IV. Macroeconomic Performance

The data on the Hong Kong macroeconomy can be obtained from various established sources, including the Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and UNCTAD. The China Statistical Yearbook annually provides China’s economic data with Hong Kong, e.g., in the amount of utilized outward foreign investment from Hong Kong to China. In the statistics, utilized foreign direct investment in China refers to the actual amount, while the contractual amount will be bigger. Fig. 17.1 shows the GDP trend, its growth rates, and GDP per capita. In the case of the GDP trend, the “dips” Hong Kong experienced included the oil crisis in 1975, the Sino–British Negotiation 1982–84, the Asian financial crisis after 1997, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, and the global financial crisis of 2008. The Asian financial crisis in 1998 was the hardest hit, with a negative growth rate of 5%.

Figure 17.1.

GDP performance of Hong Kong.

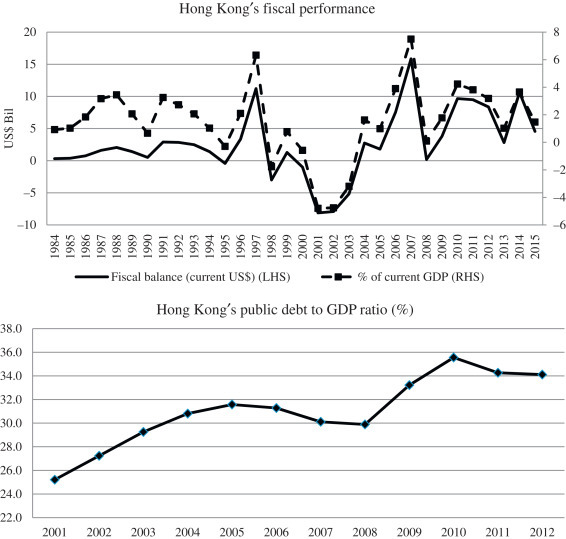

Fig. 17.2 reports the healthy fiscal performance. Other than the few years after the Asian financial crisis, it has become normal for Hong Kong to have a fiscal surplus, though in all cases, the size of the fiscal surplus has never exceeded 10% of GDP. Nonetheless, Hong Kong also enjoyed a healthy public debt-to-GDP ratio, which has never exceeded 36% of GDP. Without the need to spend on the military, the healthy fiscal policy owes more to Hong Kong’s economic openness and adherence to “supply-side” economic policies.

Figure 17.2.

Fiscal and debt performance of Hong Kong.

As shown in Fig. 17.3 , the level of market capitalization in the Hong Kong stock exchange increased drastically around 2005 when many mainland enterprises, especially the state-owned commercial banks, came to raise capital in Hong Kong. The trends of inward and outward foreign direct investment are similar, implying that much foreign direct investment may have passed through Hong Kong. By 2014, close to 70% of China’s utilized foreign direct investment came from Hong Kong. It is possible that inward foreign direct investment from mainland China to Hong Kong would become outward foreign direct investment from Hong Kong to China, as that would be regarded as foreign investment in China and would enjoy some advantages.

Figure 17.3.

Market capitalization and foreign direct investment of Hong Kong.

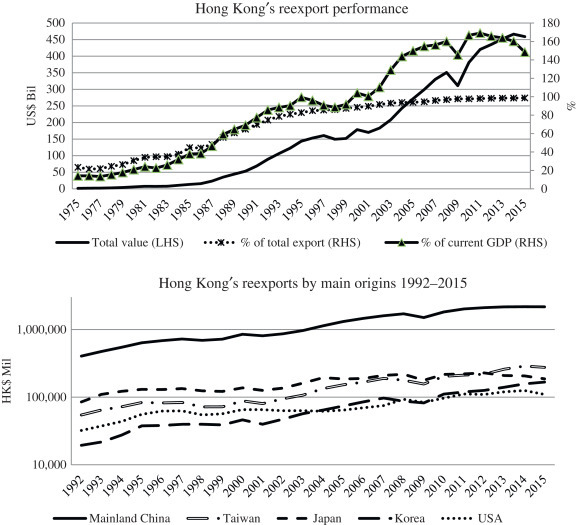

Since Hong Kong has served as a trading post between China and foreign countries, reexport business has flourished. The export of domestic manufacturing has risen since the industrialization process in Hong Kong in the 1960s. By the 1980s, after China opened up, the reexport business returned. However, with the new establishment of port facilities in southern China, Hong Kong is faced with a decline in the export of manufactured goods as the level of industrial activities declined, and there are challenges from mainland ports for the reexport business. Fig. 17.4 shows that Hong Kong has enjoyed trade surpluses, but the level of exports has slackened since 2010. However, export as a percentage of GDP has been very high, exceeding 200% of GDP, reflecting very much the open nature of the Hong Kong economy. Since the turn of the 21st century, Hong Kong’s exports to mainland China have surpassed that of the United States. Nonetheless, both mainland China and the United States are the two largest export destinations. However, one can see from Fig. 17.5 that reexport has become the dominant export in Hong Kong, as reexport as a percentage of total exports is close to 100%. But the total value of reexport has declined since 2013, suggesting that either Hong Kong’s reexport business is losing it competitiveness, or that there is a fall in Chinese exports, resulting in a lower level of reexports. China is Hong Kong’s largest reexport destination, while other reexport destinations include the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Figure 17.4.

Trade performance of Hong Kong.

Figure 17.5.

Reexport performance of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong still shows a healthy economy statistically, especially in the fiscal aspect. Hong Kong’s economic openness has been its greatest asset for all activities. It is probably true that the financial sector is increasingly becoming more important, while the trade sector may face severe challenges. To improve the trade sector, there is a need to revitalize the industrial sector so that more manufactured goods can boost the level of domestic exports.

V. Ability to Restructure Post-1997

The economic prosperity based on various short-term policies prior to 1997 provided channels for Hong Kong’s people to gain wealth as the value of their assets expanded until the outbreak of crises. One was the “chicken-flu” crisis in late 1997, and more devastatingly the Asian financial crisis in mid-1998, with the deployment of large reserve funds to rescue the stock market. The “stability and prosperity” image was soon shattered as the crisis deepened into a prolonged period of economic recession. When the economic bubble burst, the hardest hit areas were those speculative activities in the stock market and the property market. While the Hong Kong SAR government attempted to rescue the stock market from falling, ad hoc policies on restricting housing supply were instituted so as to rescue the property market, especially when pressed by the developers. Business and investment confidence remained weak as the number of bankruptcy cases rocketed. Fiscal surplus turned to face deficit, and large tax exemptions granted previously would now expose the government to fiscal narrowness. The government did marginally rewind the salary exemption down, but preferred to bite the bullet by running down the fiscal reserve and raising the salary tax rate. The fiscal deficit was spent largely on welfare provisions, as unemployment reached a record high level.

The first decade after the turn of the 21st century experienced more crises and shocks, some originating from foreign countries, such as the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack in the United States, and the world financial crisis in 2008, but the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) health hazard was originated from Guangdong across the border. However, economic recovery started around 2005, and it was only after a government decision to issue short-term bonds that fiscal performance returned to normal. As fiscal surplus reappeared, salary tax exemptions expanded again to return to the T-shape nature. Despite fiscal recovery, the Hong Kong economy in the first decade of the new century was faced with a number of rigidities. The “demand-driven” policies introduced in the 1990s expanded further when the second Chief Executive, Mr. Donald Tsang, introduced the Community Care Fund (CCF) in 2011 to provide another layer of welfare subsidy on top of the existing social security net.

The numerous economic and financial crises had resulted in a “crisis mentality,” meaning that fiscal spending and investment activities were conducted as if the economy was in a crisis situation. This implied that fiscal spending concentrated mainly on solving short-term ills, rather than creating and building long-term potential and capacity. At the same time, the focus on immediate problems would reduce short-term pains, but the delay in constructing long-term potential would result in further delays in economic progress. And in turn, the lack of progress would produce more short-term problems as the economy could not see any light at the end of the tunnel. A “vicious circle” could have developed, which would further be reinforced by “short-term investment behavior” as investment returned mainly to speculative activities.

The “demand-driven” policies persisted when mainland China provided a number of rescue packages to Hong Kong after the SARS epidemic in 2003. By using the “people’s strategy,” the “visa free” travel policy allowed a large number of mainland travelers into Hong Kong. The influx led to rapid increases in retail rentals that benefitted property owners, especially in those popular locations. Many retail shops opened, but their business concentrated on foreign luxurious brand products catering solely for the mainland tourist market. Due to the unreliability of many consumer products and the high consumption tax in mainland China, large numbers of mainland “shoppers” made multiple trips as an informal market had developed across the border in Shenzhen, where popular consumer items could easily be sold to agents on the “black market.”

Hong Kong was designated as the offshore center for the Chinese currency, the Renminbi. As it was Beijing’s ambition to internationalize the Renminbi, Hong Kong could be a good “collection center” for the Renminbi which had been taken out of China through various channels. At the beginning when Hong Kong gained the offshore center in 2005, commercial banks in Hong Kong were not too enthusiastic, as loans could not be made in Renminbi. However, trading of Renminbi increased rapidly after 2009 when Beijing required Hong Kong’s trade with mainland China to use the Renminbi as the trading currency (Hong Kong Monetary Authority, 2016). Effectively, the Renminbi would just be another currency traded in the commercial banks. The greater connectivity between the Hong Kong currency and the Renminbi could have other advantages to the mainland economy, including the ability for mainland corporations and state-commercial banks to raise capital in the Hong Kong stock market after 2005. This, in turn, has made Hong Kong the largest world financial center in market capitalization. The Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect begun in November 2014 widened the possibility for both mainland and Hong Kong investors to invest in each other’s stock market. The Shenzhen–Hong Kong Stock Connect was eventually approved on August 16, 2016 (“Hong Kong becomes world’s largest exchange operator,” Developing Markets and Asia, April 13, 2015; “Hong Kong Stock Exchange,” “List of Public Corporations by Market Capitalization,” “Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect,” Wikipedia; South China Morning Post, August 17, 2016; and “Shenzhen–Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect,” Hong Kong Stock Exchange Limited, August 17, 2016).

The various phases of the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) after 2005 allowed tariff-free exports of Hong Kong manufactured goods to mainland China (Trade Department, Hong Kong SAR Government website). The agreement covered three areas: export of manufactured goods, services trade, and government-to-government facilitation. Tariff-free exports covered over 1700 export goods, but many items included in the list had not been produced in Hong Kong. Industrialists have not been taking advantage of the CEPA in conducting industrial production in Hong Kong for export. In the case of professional services, some professions that would benefit mainland China, typically medical, construction, and hospitality professions, were highly welcomed, but some sensitive professions, such as legal and accounting professions, would have to seek mainland qualifications. Facilitation involved information exchanges between the two governments in such issues as medical incidents, immigration matters, cross-border issues, and custom regulations.

Although there was economic recovery after 2005, the Hong Kong economy was still based on “investments” in the stock and property markets. Property prices had skyrocketed and earned the status of the highest property prices in the world (“Hong Kong tops global cities list as most valuable residential location in 2015,” World Property Journal, October 23, 2015; and South China Morning Post, January 25, 2016). Although the economy was hurt in the 2008 crisis, the fiscal situation improved as surpluses returned. Nonetheless, opportunities for economic restructuring did not come forward as time passed. There are numerous explanations for the slow pace of economic restructuring. The achievements of the Hong Kong economy were based on the dominance of the private sector, but calls for an increased role of government had been made, especially after the 1998 crisis. One should note that government officials would not be a suitable group of people for developing business. Unfortunately, due to the sequence of crises after 1997, the Hong Kong SAR government was equipped with a “crisis mentality,” even when the crisis was over. To keep a crisis mentality in a noncrisis situation means that policies would focus more on short-term results than on promoting long-term potential.

Another political argument for the lack of action could be the psychological need to wait for “orders, approvals, and/or instructions” from Beijing. Instead of making initiatives and drafting investment plans, local business people and government officials could have kowtowed to the “new boss” on what to do. On the contrary, Beijing officials, at least nominally, had been urging Hong Kong to work on its economic affairs. It was a mistake on the part of Hong Kong businesses and officials to seek “directives” from Beijing. Or indeed, Beijing did give “instructions” on what and what not to do in Hong Kong. After all, the economic fate of Hong Kong would have a direct impact on the mainland economy. For example, an economically weaker Hong Kong could suit the political outcome in Beijing as the mainland economy rises, or could demonstrate the relevance and importance of the “one country.” Such a scenario would not be infeasible, as one could indeed judge from the lack of investment action and low degree of economic advances in Hong Kong SAR since 1997, especially from the business sector.

The various domestic developments could have produced obstacles in economic restructuring. The emphasis on “demand-driven” policies, coupled with the rising welfare spending, has reduced business incentives. Although the minimum wage was introduced in 2010, the long-term impact to business may not be favorable, as there are alternative investment destinations nearby (Bloomberg, November 10, 2010). The economy had increasingly become “domestic-led.” The existence of strong pressure groups, especially the green groups which preferred to see less development, would have taken up protectionist policies unfavorable to economic growth. Hence, a dilemma was created: social groups complained about the lack of job opportunities and social upward mobility, the green groups insisted on nondevelopment.

There were other mistaken attitudes that investors in Hong Kong held. They had been led to believe that industrial development in the form of light manufacturing was no longer appropriate, because of a lack of industrial land, high costs, and the development in mainland China. Investors’ mindsets were still related to the former “glories” when Hong Kong excelled in labor-intensive manufacturing. Few thought how and what kind of industrial production would suit Hong Kong most. For example, through the CEPA, Hong Kong could be the first supplier and manufacturer to capture the mainland market, as the huge market potential in the mainland could easily cover the “high costs” in Hong Kong. Hong Kong could concentrate on nonland intensive production, such as testing and quality control activities, and medical related supplies. With rising incomes in the large mainland population, Hong Kong manufacturers needed to identify the market inadequacies on the mainland, and venture into the large potential market. More creativity would be needed on the part of the business sector. What Hong Kong has most is the sea. Different types of yacht and boat racing in the warm seasons would generate not only tourism, but also marine-related industries in the islands.

There were also complaints on the “one-sided” bias in development in infrastructure and tourism in favor of mainland visitors. The two typical examples were the Guangzhou–Kowloon rail link and the Hong Kong–Zhuhai Bridge, where massive over-budget spending was needed. The terminal of the Guangzhou–Kowloon rail link would have to be in the heart of Kowloon, but another express train service already existed there, in addition to the numerous ferries that provided daily multiple services to ports in Guangdong, and bus or cross-border bus services that provided efficient land transport. The Hong Kong–Zhuhai Bridge was meant to link Hong Kong to the western side of Guangdong and western provinces in mainland China. Other than the high cost, other practical concerns included traffic safety, as Hong Kong adopted right-hand drive while China adopted left-hand drive.

Indeed, there is no shortage of possibilities, but there is a shortage of initiative. High costs and lack of land were excuses rather than reasons for not engaging in new investment ventures in Hong Kong. Another possible explanation could be the aging business sector. Many successful business people in the 1970–80s had reached retirement age and would not be aggressive enough in creating new investment ventures, and their children stayed in their “comfort zone” and lacked foresight in creative business ventures. A new generation of young entrepreneurs would be needed. Young people with enterprising minds would have to come forward to take risks and venture into new businesses.

On the whole, economic restructuring in post-1997 Hong Kong was slow to come. Initiatives and opportunities had to be weighed against risk and cost. Returns and profits had to be weighed against time and alternatives. Would speculation in stocks and property be a better choice than investment in industries? Would securing paid employment be a better alternative to setting up a business? Would relying on welfare be a more secure outcome than remaining in employment? Would severe competition erode profits? Would the dynamic and ever changing nature of business favor only brand name products and not starters? Would the political situation erode business confidence?

The post-1997 government began to operate in July 1997, but the economy was much more mature. Since the Chief Executive was not freely elected, the government might become cautious in introducing policies. As a result of the “demand-driven” policies introduced in the years before 1997, welfare expenses became dominant and occupied a large percentage of the fiscal budget. Consequently, government intervention increased in various directions, such as assistance to small- and medium-sized enterprises, and subsidies to the movie industry. In the case of SMEs, government assistance did not meet with much success, as applications required financial and accounting disclosure by SMEs. In the case of movie production, one wondered why celebrities in Hong Kong had to be assisted by the tax payers. Once started, the network of government intervention could only expand, and more and more businesses and industries would in turn seek similar assistance.

There was a lack of distinction between welfare assistance and government intervention. Welfare assistance should be given to the needy on a “blanket” or “lump sum” basis when faced with difficulties. Intervention occurred when welfare spending was geared to a particular aspect of one’s private life, or a particular business activity. In some years, welfare spending was geared to the payment of after-school tutorial classes and piano lessons for children in welfare recipient families. This raised concerns as to why and how the government would know that children from welfare-receiving families needed after-school tutorial assistance. The irony was whether the education system was not being provided adequately. In short, the government was increasing the size of “social cost.” Yet, the tax players who financed the welfare spending did not have a say.

The severe consequences resulting from the various crises had led Hong Kong to a weaker or even a depleting private sector, and people began to seek answers from the government, which was not supposed to provide solutions for private sector activities. A “chicken and egg” situation developed when crises struck, the weakened private sector complained about the lack of government directives, initiatives, and assistance. Yet, the government excelled more in administrative implementation than in business initiation. As such, except in the provision of welfare, the Hong Kong SAR government was unable to lead the economy away from the crises and promote a new stage of development by reorienting the utilization of resources.

The ultimate prerequisite for economic restructuring, widening, and deepening would be the development of an enterprising attitude and behavior. While creative individuals look for and create opportunities, the government should facilitate through indirect means and by promoting a business-friendly infrastructure. Intervention is cancerous, as more will always be required as it spreads. Intervention and entrepreneurship are inversely related to each other, the rise of one will mean the fall of the other, and vice versa. With a population of over seven million, there would still be the need to restructure the economy by creating and diversifying industries and businesses. There needs to be a change of attitude from one of reliance on government to one of pursuit of private initiatives, from one of speculative investment to physical investment, from one of servicing the mainland economy to one of becoming the recipient of physical investment from the mainland, from one of integrating with the mainland economy to one of enlarged business corporations to capture the world market, from one of low cost service provisions to application of technology-related manufacturing, from one of a high cost mentality to one of a large market size mentality, from one of politicization with unwanted, unpleasant, or unintended “absolute” outcomes to one of profit-maximization with different magnitudes in “relative” outcomes, from one of a welfare recipient to one of a tax contributor, and finally from being the follower to becoming the creator.

VI. Absolute Versus Comparative Advantage

In many ways, the Hong Kong economy survives on the various inadequacies of the mainland economy. One could just apolitically consider the facts. From day one as a British colony, Hong Kong served as an entrépot between Qing China and the outside world. The high degree of global insensitivity in the Qing government can be blamed on no one but itself. Hong Kong had been the popular destination for immigrants whenever there were crises and hardships in mainland China. During the trade embargo imposed on communist China after 1949, it was the pro-Beijing business people in Hong Kong that helped to smuggle needed materials to mainland China. Private individuals used to bring consumables back to their villages. In the 1950s and 1960s, clothing materials, cooking oil, and processed food were high on the agenda. In the 1970s and 1980s, household appliances, such as refrigerators, televisions, and air conditioners were carried across the border.

Since China’s economic reform in 1978, provisions of formal economic activities from Hong Kong included outward investment, knowledge, management and technology transfer by businesses and institutions, financial and banking facilities provided by the financial sector, and international connectivity through Hong Kong. As the mainland economy expanded, and despite the development of various markets on the mainland, state and other large corporations came to Hong Kong to raise capital through the Hong Kong stock market. After the Asian financial crisis in 1998 when recession occurred in Hong Kong, there was a period when people in Hong Kong went shopping across the border for low-cost materials, such as curtains, massages, and restaurants. Such trends, however, ended gradually as recession gave way to recovery in Hong Kong, and the lack of improvement on the mainland discouraged cross-border spenders. However, after the “visa free” travel policy was issued to mainland citizens in 2005, Hong Kong became a shopping paradise for mainlanders for numerous consumer items. Parallel trade, informal economic activities, and “black markets” flourished on the other side of the border. Li (2006,2012a)Li (2006)Li (2012a) used the “complement–competition” model to describe the dynamic relationship between the two economies. As mainland businesses and institutions looked to Hong Kong for references and lessons, Hong Kong served as a complement to the development of these mainland institutions. While the “complement” relationship is on the “need” of Hong Kong, the “competition” relationship is about the “use” of Hong Kong by mainland enterprises. As businesses, industries, and institutions on the mainland developed and progressed, there was every possibility that they would overtake and compete with similar activities in Hong Kong. Hong Kong would lose out, unless mainland businesses also used Hong Kong for other services. The Hong Kong economy would survive so long as there were new developments in the mainland economy.

Indeed, the economic relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong has also been propagandized. Leftists have been raising the flag that the rapid economic progress in Shanghai would overtake Hong Kong, and the Hong Kong economy would be marginalized. Politics aside, the economic analysis in the relationship between the two economies is an understanding between “absolute advantage” and “comparative advantage.” Given that the three economic factors of production are land, labor, and capital, one can observe that the mainland economy has much more of these three factors than the Hong Kong economy. As such, the mainland economy is said to have “absolute advantage” over the Hong Kong economy. The Hong Kong economy loses out completely when one employs the “absolute advantage” concept. The more appropriate and realistic way to consider the relationship between the two economies is to use the “comparative advantage” concept, as the Hong Kong economy does have various advantages that perform comparatively better than the mainland economy. The economic strategy for Hong Kong should be to maintain, extend, expand, and deepen the various “comparative advantages,” rather than making absolute comparisons. Therefore, one has to look for economic substance, rather than just quantified factors. Between Hong Kong and Shanghai, e.g., one has developed using free market instruments, while the other has developed from a process of deliberate designations from the state.

In many ways, one should examine the extent of cooperation rather than integration between the two economies. Economic cooperation should be mutual and show “positive-sum” outcomes, so that both economies will gain, though the magnitude of the gain can differ. The rise of the mainland economy does not mean diminishing of the Hong Kong economy. Indeed, the mainland economy should develop more modern metropolitan cities similar to that of Shanghai. It would be naive and propaganda-prone to think that the development of more urban cities and financial centers on the mainland would mean the fall of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong excels in the reliability and sustainability of the capitalist market and civic system. Businesses, investors, and leaders come and go, but the system remains to serve existing participants and new players. The economic success of Hong Kong will not rely on personalities or words from some leaders or government officials. It is the system that people trust. What will be needed is to ensure the functionality of the system, that it will be improved and can be defended. There is no perfection in the Hong Kong system, but the relevance is in perfecting the Hong Kong system.

Other than the “visa free” travel policy, the offshore Renminbi center, and the CEPA trade agreement, there are other channels of cooperation between the two economies. One has to bear in mind that Hong Kong is an open economy, and “business is always as usual” for investors and businesses. Over the years, a large number of mainland businesses have established their posts in Hong Kong, and mainland funds that came to Hong Kong were invested back to the mainland. One medium of economic cooperation established around 2008 was the Pan–Pearl River Delta Regional Cooperation (Pan–PRD) that linked Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and nine southern provinces (Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Fujian, Hainan, and Guangdong) in mainland China. The economic zone is popularly known as the 9+2 project, and is meant to become a parallel development to that of the Yangtze River Delta Economic Zone, the Bohai Economic Rim, and the Western Triangle Economic Zone in different parts of China. The Pan–PRD consists of a sizable region as it has a population of 453 million, equivalent to 35% of the total population of China. In 2003, the collective GDP of the region amounted to US$652 billion, amounting to 40% of total economic output of mainland China (Pan–Pearl River Delta Regional Cooperation). There are annual meetings among the leaders in the 9+2, but various regional differences exist. Hong Kong could indeed be easily accessible distance-wise from western provinces in China. Hong Kong can also serve China’s growing relationship with Southeast Asian economies.

The “one belt, one road” initiative, and the subsequent development of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), had led to extensive talks as if Hong Kong would definitely benefit from the project. The benefits Hong Kong could have can be summarized in the acronym “BLITT” that involved businesses in Banking, Logistics, Industry, Technology, and Trade. Commercial banks in Hong Kong will start developing trading of currencies among the countries on the “one belt, one road” route. Logistics involve various forms of logistic businesses, ranging from transportation, education, and training, to management and professional activities. Investment in industries could take place along the “belt and road” route. Hong Kong excels in applied technology and commercialization that can be used in manufacturing of consumer goods. The activities in banks, logistics, investment, and technology would add up to an increase in trade. These five areas should widen the base of the Hong Kong economy. Businesses in these areas should think forward and be the “early bird” in capturing the various opportunities. Similarly, the Hong Kong SAR can start establishing connections and facilitations with cities along the “belt and road” route. However, the “one belt, one road” proposal is still in its constructive stage, it may take years, if not decades, for projects to materialize, and may involve various types of risks: political, currency, territorial, diplomatic, security, material supplies, and financing (Szczudlik-Tatar, 2013; Rolland, 2015; Summers, 2015). Nonetheless, getting prepared will be the most appropriate action for Hong Kong. Once again, Hong Kong is exercising its comparative advantage, which should be conducted and expanded in both directions. The “extensive” direction involves the exploration of more areas of comparative advantage, while the “intensive” direction involves doing a better job in each area of comparative advantage.

VII. The “Economic Cushion”

Despite its success and the reliability of the capitalist market and civic system, the Hong Kong economy is vulnerable to shocks and decline. Yet, economic advancement is a long-term process, is apolitical, and requires the development of a “virtuous cycle” and positive participation. Hong Kong’s economic advance is the responsibility of all and every individual, business, official, and institution. The post-1997 Hong Kong economy is faced with a number of unfavorable trends that will generate more of a turning point from a rising trend to a falling trend, rather than a crossroad where the direction of the development remains unclear.

The adoption of “demand-driven” policies had unfortunately reorientated Hong Kong’s economic path negatively. And the various crises in post-1997 prolonged and deepened the effect and impact of these policies. Hong Kong is increasingly becoming a welfare state, where demand for more welfare and assistance to low income groups is rising more rapidly than the ability to generate a rise in income and output. At the same time, economic narrowness is appearing, as investment activities concentrate on speculative activities in stocks and properties. Indeed, speculation has become the only channel through which a handsome return can be obtained. Thus, despite its periodic fiscal surplus, the SAR government has not been able to widen the economy and provide visions of growth, which should be obvious as government officials are not meant to excel in business ventures. Nonetheless, policies tend to be monolithic, and not integrative and comprehensive enough to produce a convincing picture of development. For example, the land redeployment policy met with opposition from various pressure groups. Officials holding a “crisis mentality” to manage a “noncrisis” economy can only engage in policies that produce short-term results. Meanwhile, time and opportunities are wasted as restructuring is best introduced in noncrisis situations. Given the appalling property prices and the lack of opportunities, the younger generation would more likely face “downward” than “upward” social mobility.

Hong Kong cannot hold on to its “economic cushion” for too long. The dominance in the domestic nature of the Hong Kong economy cannot be sustained if only “demand-side” policies are practiced. Greater spending with delays and prolongation of new development and restructuring would generate a “vicious circle” on its own. While there is sympathy for low income earners, it is output and productivity that count. For economic sustainability, the increase in output has to be higher than the increase in welfare assistance and government spending. A growth- or productivity-related welfare system has to be instituted to ensure a balance between growth and spending. There is also a need to clarify and study what constitutes the needy group of individuals. Is aging equivalent to poverty? Is sympathy an ideology, or a propaganda instrument that imposes economic constraints?

To build up Hong Kong’s “economic cushion,” efforts are needed to redirect resources and policies to favor “supply-side” factors that promote Hong Kong’s competitiveness. Hong Kong excelled in the ability to serve others, and gained in the process of facilitating the business of others. Flexibility that allow economic factors to move with the world economy is the prerequisite condition, not rigidity that imposes economic burdens on competitiveness. Hong Kong provides an economic platform for all to work and perform, not for parasites that do not contribute but live on others. It is the multiplication of opportunities that lubricates the Hong Kong economic engine.

VIII. Conclusion

The 50 years from 1997 to 2047 are a testing ground for the Hong Kong economy. Economic development and progress will have to be compromised with political development and demands, domestic issues that could erode economic competitiveness, effectiveness of governance in directing the economy into new directions, high levels of economic capability that require further restructuring, short-term investment behavior that provides a “comfort zone” for speculation, aging businesses that need “new blood” in promoting enterprising behavior, and the various distortions in resource deployment.

The ultimate cushion Hong Kong has is its capitalist principles and the free and transparent market system that provide a base for possible revitalization, rejuvenation, recovery, and restructuring. While Hong Kong is faced with transition in the period leading to 2047, many hold a “wait and see” attitude as transition produces challenges to the local economy. On the contrary, this transition period could be Hong Kong’s opportunity to show to the world economy how Hong Kong could proceed and excel to a stage of development higher and better than that before 1997. Hong Kong does not have any “comfort zone” from being a British colony, nor should it expect to have mass subsidy from the mainland without political cost. Holding a “siege mentality” will still be needed for the Hong Kong people.

Other systemic improvements include effective governance, equality of opportunity, eradication of discrimination, ethical standards and practices, elimination of malpractice, and so on. Hong Kong will serve as a showcase to other countries that economic growth within a civic model of development will produce an optimal society. As such, Hong Kong should take the initiative and be creative instead of waiting for blessings, orders, and permissions. Hong Kong is a mature economy and should not exhibit any fear, but should be courageous to venture out into new areas of development, using opportunities to bury conflicts, using results to destroy abuse, using intellect and wisdom to overcome selfishness and bias, and using systemic effectiveness to eradicate cronyism and personality influences.

In humanity, virtues are goals that are always easier said than done. Developmental goals are often agreed in the discussion stage, but divergent views always arise in the implementation stage. Time is costly, and the longer the delay, the poorer the result could be. Leaders need to be courageous in taking bold steps, while businesses should show long-term perspectives and be forward looking in their investments. Individuals should find a way to show their best, rather than to complain about various inadequacies and wait for assistance. Hong Kong is a land of opportunities, but nothing comes free. Progress in the Hong Kong economy should not be thwarted and disillusioned by crises, but should overcome crises in the shortest possible time and reorientate its energy and resources for a faster pace in restructuring and redevelopment activities.

Hong Kong does not have a “fall back” sector, like a large agriculture sector which could absorb people’s livelihood at times of crisis and difficulty. Hence, moving forward is the only answer for the survival of the Hong Kong economy. For example, Hong Kong in 2016 has been ranked the most competitive economy based on the annual survey of 61 jurisdictions around the world conducted by the IMD World Competitiveness Center in Switzerland. Business-friendliness in the form of simple taxation and unrestricted movement of capital are the key factors in the high ranking (IMD Competitiveness Center, May 30, 2016). The economy has to proceed at the fastest possible pace through policies that foster and fortify “supply-side” factors in both extensive and intensive dimensions.

It is equally true that politicization in post-1997 Hong Kong would hurt Hong Kong, because the nature of “absolute” outcomes in politics would be divisive, fragmented, rivalrous, and antagonistic. Political problems tended to show a cumulative momentum. Between the leaders and the people, it involved compromise when the people demanded political changes, and how the leaders responded requires the art of diplomacy. The political situation would deteriorate should demands be suppressed. In a politically sensitive economy, fragmentation would occur among different groups that considered only their own narrow interests. As such, compromise and consensus would even be more difficult to achieve. Hence, the more important key in the solution to political conflict will first rest with the leaders as to whether they are prepared to respond positively or adopt a “divide and rule” strategy, thinking that would amass support by marginalizing the opponents.