Abstract

This article reviews in a historical perspective and by means of documented examples the scientific principles relevant to the concept and effectiveness of quarantine, the logistic, economic, and political barriers to its correct implementation through time, and the health impact of local and large-scale quarantine. Quarantine is overall one of the oldest and most disseminated and, despite its limits, most effective health measures elaborated by mankind. The evidence-based history of medicine and evidence-based modern epidemiology indicate that the implementation of correct quarantine procedures is today still feasible and useful provided that a proactive collaboration is operative among those concerned and that the measures are tailored according to geographical, social, and health conditions.

Keywords: Avian influenza, Epidemiology, Epistemology, Evidence-based medicine, Health care, History of medicine, Medical semantics, Plague, Prevention, Quarantine, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Therapy, Transmissible diseases, Tuberculosis

Background

Quarantine may be defined as the restraint or segregation of human beings or other living creatures, who may have come, either potentially or actually, into contact with transmissible pathologies, until the moment when it is considered certain that they no longer constitute a health risk. The term and the concept of quarantine are profoundly rooted in culture and world health procedures, and have periodically recalled peak interest in the course of epidemics. In the past the concept of quarantine was used to refer to the period of isolation of people alone, whereas in more recent times it has come to be applied to animals and things as well (Gensini et al., 2004).

Quarantine has been implemented in many different ways in the course of Western history, undergoing periods in which it was highly considered and periods in which it was relatively neglected. In Europe and North America, during the last decades of the twentieth century, quarantine was substantially underrated, given that the spectacular achievements of modern medicine, from effective vaccines to powerful antibiotics, generated, in the general public but sometimes in health systems and operators too, the false impression that the battle against infectious diseases could be considered won. The recent, worldwide realities of ‘new’ transmissible pathologies, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the avian influenza, have provided evidence of the fact that human beings are still engaged in a struggle against pathogen agents. These communicable diseases have determined a boost in the popularity of quarantine: in the United States, because of the avian influenza, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has opened many new control stations at the border points in which there is a higher influx of people (Mafart and Perret, 2003).

The history of quarantine paradoxically indicates that people do not learn enough from history itself. Recent surveys conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that if avian influenza were to expand through the United States, the mandatory cooperation of U.S. citizens would be low, if not very low. Furthermore, in the case of an epidemiological emergency, the collaboration of the majority of the population in health measures planned by the government would be limited, largely because the majority of the interviewed people did not know what quarantine is, what it is for, and what it exactly entails.

Reviewing quarantine from a historical-didactic perspective therefore constitutes a notable formative opportunity to illustrate an ever-pertinent health measure, whose general potentialities and limits of application must be precisely understood not only by health administrators, medical historians, and technical operators, but also by the general public.

The Ancient Past

The word ‘quarantine’ was first documented in the English language, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in 1663, as “A period (originally of forty days) during which persons who might serve to spread a contagious disease are kept isolated from the rest of the community; especially a period of detention imposed on travellers or voyagers before they are allowed to enter a country or town, and mix with the inhabitants; commonly, the period during which a ship, capable of carrying contagion, is kept isolated on its arrival at a port. Also, a period of seclusion or isolation after exposure to infection from a contagious disease” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2004). After other specifications, the description of the term concludes as follows: “Hence, the fact or practice of isolating or of being isolated in this way.”

Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1976) presents two different origins for the etymology of the term, one deriving from the Italian and the other from the French. The latter appears restricted to the legal sense of the word (Coke, On Litt. 32b, 1628: “If she marry within the forty days she loseth her quarentine”) and is considered a variation of the French term ‘quarantaine’ (Old French), deriving from ‘quarante’ (forty), in turn from Latin ‘quadraginta’ (quadra- (akin to quattuor, four) +-ginta (akin to viginti, twenty)). In its health-medical meaning, quarantine is considered a modification of the Italian word ‘quarantena’ (quarantine of ships), from the Italian ‘quaranta’ (forty), in turn from Latin ‘quadraginta.’

Given that the ultimate origin of both etymologies is the Latin ‘quadraginta,’ the common denominator of the word is the temporal indication of a period of 40 days. This period had already been identified with precision by the Hippocratic School, which, around the fifth century B.C., described a number of diseases with specific reference to their duration. Plague was considered a ‘pathological paradigm’ for acute illnesses, those that manifested themselves within 40 days; diseases clinically evident after 40 days could not be acute, and consequently could not be the dangerous plague. Forty days was therefore considered in ancient Greek medicine a medical turning point useful in differentiating different diseases, and 40 days accordingly became the established length of quarantine for transmissible diseases (Gensini and Conti, 2004).

The Holy Bible describes health control measures. The Old Testament (Leviticus 13) suggests isolating infected people, also indicating the need to burn their garments. Specifically, the text refers to the plague and leprosy, thus evidencing how people affected both by rapidly beginning and developing diseases, such as the plague, and by slowly evolving ones, such as leprosy, were to be segregated from healthy people for variable periods. In the New Testament, too, leprosy is considered a determinant of social discrimination, capable of being cured only by means of a divine miracle, and isolation of sick people continues to be implemented as the most effective strategy to control the spread of transmissible diseases (Conti and Gensini, 2007).

“The Holy Bible interestingly describes health control measures. The Old Testament (Leviticus 13) suggests isolating infected people, also indicating the need to burn their garments. Specifically, the text refers to the plague and leprosy, evidencing how people affected both by rapidly beginning and developing diseases, such as the plague, and by slowly evolving ones, such as leprosy, were to be segregated from healthy people for variable periods of time. In the New Testament too leprosy is still considered a determinant of social discrimination, capable of being cured only by means of a divine miracle, and isolation of sick people continues to be implemented as the most effective strategy to control the spread of transmissible diseases.” (Conti and Gensini, 2007)

In 549, Justinian, emperor of Byzantium, issued laws targeted to isolate individuals coming from regions infested by the epidemics of bubonic plague. A few decades later the Council of Lyons forbade lepers, or at least those retained such, from associating with healthy subjects. It is precisely the historical conceptual difficulty in separating actually healthy from apparently healthy people that remains one of the major problems in the operational implementation of quarantine.

Medieval Rules and Regulations

The Middle Ages are conventionally considered the ten centuries from the end of the fifth century AD to the end of the fifteenth century AD (1492, the discovery of America). Historical sources from the sixth to the fifteenth centuries AD clearly indicate that, from a clinical and epidemiological standpoint, what today is called the plague, the infectious disease caused by Yersinia pestis (the Latin ‘pestis’), gave rise to recurrent epidemics throughout Europe. In the course of the fourteenth century, for example, the plague caused the death of more than 30% of the European population. Towns and villages tried to defend themselves by isolating recognizably sick persons, quarantining potentially infectious individuals, and forbidding the entry into healthy communities of goods and persons coming from infected environments. Documentary historical evidence indicates that, in the seventh century AD, armed guards were stationed between plague-stricken Provence and the diocese of Cahors. In the absence of vaccines and drugs, quarantine was the only effective health measure against the spread of transmissible diseases (Knowelden, 1979). It has been calculated that in medieval times, no more than two consecutive generations (40–50 years) passed before a new explosion of an epidemic of the plague.

It is in this context, and specifically during the fourteenth century, that, at least in the Western world, the concept of structured preventive quarantine emerges. As has been said, in Medieval times the plague continued to represent a major public health and economic danger, and therefore, to protect their people and their trade, the great mercantile potencies issued, in the course of the fourteenth century, rules and regulations regarding quarantine.

In 1348, during a notorious epidemic of the plague (the “Black Death” described by the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio in his masterpiece Il Decamerone) the Republic of Venice (Italy) established a system of quarantine assigning to a council of three the responsibility and power of detaining individuals and entire ships in the Venetian lagoon for 40 days (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the “Black Death” from the Toggenburg Bible (1411).

The Rector of Ragusa (currently Dubrovnik, Croatia), an outstanding rival sea potency of Venice, enacted in 1377 a decree officially establishing the so-called ‘trentina’ (an Italian word derived from ‘trenta,’ the number thirty), a period of isolation of 30 days for ships coming from infected, or even only suspected to be infected, places (Figure 2 ). The 30-day period became 40 days for land travelers. Travelers coming from areas in which the plague was epidemic or endemic could not be hosted in Ragusa until they had been segregated in isolation for (approximately) a month, and whoever did not observe this edict was fined. No citizen of Ragusa had permission to reach the isolation area, apart from selected officials assigned by the Great Council to the care of the quarantined persons. Moreover, the chief physician of Ragusa, Jacob of Padua, advised building a site far from the town for the health care of suspected or definitely sick people (Frati, 2000).

Figure 2.

The Republic of Raguse. Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/image:Map-of-Ragusa.jpg.

A few years later Venice established that the quarantine of infected or suspected should occur on the island of the lagoon where the monastery of Santa Maria of Nazareth was, and whose health staff came from the hospital of Saint Lazzaro (Cosmacini, 2001). This maritime quarantine station was consequently called “lazaretto,” and from this, in succeeding centuries, the term ‘lazaretto’ became the defining word for all quarantine centers in Italy and often also abroad.

Venice and Ragusa may be said to share, at the end of the Middle Ages, the primacy of drawing up edicts, rules, and regulations regarding quarantine. Quarantining policies were of course determined by health necessities, but also to a notable extent by economic reasons, as is evident from the naval trading roles of Venice and Ragusa in Medieval Europe. Not by chance did the attention of the Venetian and Ragusan rulers to the medical features of the plague and also to its important economical and social effects lead to the elaboration of the first official quarantine systems. These rules and regulations became a template for many other European countries during the following centuries.

The Renaissance Period and the Sixteenth Century

The European Renaissance is conventionally considered to be the period covering part of the fifteenth century and the sixteenth. At the beginning of the sixteenth century a maritime quarantine center was opened in the French port of Marseilles. The selective concentration of quarantine stations in ports is typical of this period, since sea trade was the far more practiced form of mobile commerce and therefore constituted the major route of contagion between mobile populations.

It is precisely in the sixteenth century that a first structured notion of infectiousness appears and develops. Much of the merit for this must be attributed to the Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro, who identified and described the concept of contagion, through the idea that small particles were able to transmit disease. This new and relevant medical hypothesis allowed official medicine to elaborate more precise (even if always local) quarantine interventions (Gensini et al., 2004).

It was during the sixteenth century, too, that the quarantine system was expanded by the introduction of bills of health. These were typologies of certification that the last port of call of ships was not affected by disease. Consequently, a ‘clean bill’ enabled the ship to use a port without the need for quarantine. In the Renaissance period the plague finally diminished in frequency and virulence, at least in western Europe, whereas other diseases, such as cholera and yellow fever, spread. Quarantine laws were consequently extended to these diseases, gradually acquiring, during the sixteenth century, additional features as compared with their original application during the Middle Ages. One of these was the definition of a social body to warrant the indispensable isolation framework, including the dispositions and effective application of the regulations themselves. Another key feature was the acquisition, through time, of the understanding of the basic mechanisms of contagion (Fidler, 1999).

The Seventeenth and the Eighteenth Centuries

During the first half of the seventeenth century more pertinent action was adopted with regard to quarantine and related measures. In Europe, particularly in Venice, health officials were required by health legislation to visit private houses during plague epidemics so as to identify infected individuals and isolate them in pest houses located far from urban centers. The seventeenth century Milanese ‘lazaretto’ became famous when Alessandro Manzoni described it in his nineteenth century novel I Promessi Sposi, in which the plague plays an important part.

Still in the first half of the seventeenth century, but this time on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Bostonian officials issued an ordinance compelling every ship on arrival to remain at anchor in harbor for a certain period under penalty of a heavy fine. In 1663 a smallpox epidemic in the city of New York forced the General Assembly to draw up a law requiring persons coming from infected, or suspected to be infected, areas to remain outside the town until health officials decided that they were no longer a threat to residents.

When the plague reached Russia (1664), sanitary officials in charge of the quarantining policies in Moscow strictly forbade travelers from other countries from entering the Russian capital under penalty of death. A few years later the English Crown enacted royal decrees aimed at permanent quarantine. The problem of the time was that, despite the availability of a number of official acts regarding quarantine, this health measure was regarded with vexation by the majority of the population and, what was even worse from the general public and sanitary point of view, it was often disregarded. This made the passing of even more stringent regulations necessary. As a result, in England, in the second half of the seventeenth century, every London-bound ship had to remain at the mouth of the Thames for 40 days; sometimes this period was prolonged to 80 days (Figure 3 ). This flexibility as to the duration of quarantine was in fact the cause of the uncertainty and antagonism with which such measures were regarded. The absence of a clear and shared definition of the length of quarantine biased the perception of the utility and scientific basis of quarantine on the part of the resident populations of the various countries in Europe, and even more that of the travelers. Furthermore, quarantine regulations were sometimes implemented as pretexts for repressive measures; the disinfection of correspondence, for example, was used as an excuse for political espionage (Mafart and Perret, 2003).

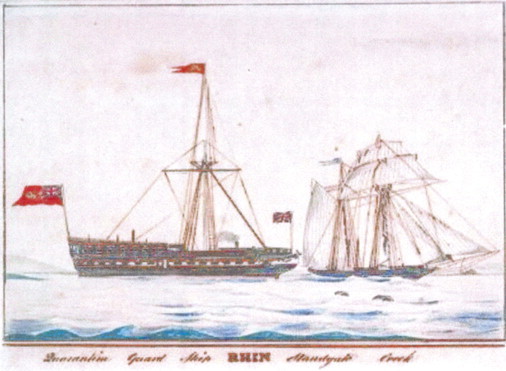

Figure 3.

A quarantine ship out near sheerness (UK National Maritime Museum).

At the beginning of the eighteenth century the plague, cholera, yellow fever, and smallpox were still terrible transmissible diseases requiring quarantine. The Quarantine Act was passed in England in 1710, which stipulated a sentence of death for persons not respecting the compulsory 40-day quarantine for humans and goods arriving on the island and suspected or known to have been in contact with the plague. Similar laws were passed in the United States, too; a quarantine anchorage off Bedloe's Island was issued in 1738 by the City Council of New York to prevent the diffusion of yellow fever and smallpox. In 1797 Massachusetts passed a public health statute that established the power of state quarantine. In the last decade of the eighteenth century the administration of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania had a ten-acre quarantine station built south of the town along the Delaware River to combat yellow fever, which had continued to be an extremely serious biological danger for the whole state. This health and architectural effort documents well the importance attributed by city politicians and health officials to quarantine as a preventive and therapeutic intervention. From this period on, an awareness of the need for an ample standardization of quarantine measures began to grow in many places, both in Europe and in the United States. Nonetheless, there was still a long way to go, and it was only during the nineteenth century that shared rules and regulations appeared on a large scale, following scientific and political international conferences.

The Nineteenth Century

The various historical periods were characterized by diseases with different infectious patterns. The plague, for example, was, in its predominant forms a typically acute, if not hyper-acute, potentially healable condition; leprosy, in contrast, was a chronic, non-healable disease. Unfortunately, from a health measure point of view, the common denominator among such illnesses was that quarantine policies lacked homogeneity not only across different nations but also within the same nation (Fidler, 1999).

In the nineteenth century frequent cholera epidemics finally prompted the necessity for a uniform quarantine policy. In 1834, France proposed an international meeting for the evaluation and sharing of supra-national standardizations of quarantine. However, notwithstanding the high incidence of epidemics of communicable diseases, it was only in 1851 that the First International Sanitary Conference was convened in Paris (Maglen, 2003).

As in medieval times, implicit in quarantine policies to protect health was the perceived need among nations of protecting home trade. The various priorities and political views of countries constrained formal agreements. The way toward common and shared quarantine measures was accordingly long and tortuous. To face the problem of political expediency, for example, in 1881 a conference was called in Washington, DC. In 1885, during another conference held in Rome, an interesting proposal regarding the inspection of quarantine of ships from India (by means of the Suez canal) led to an animated debate between France and Britain, not specifically about health intervention or medical necessities but essentially about the question of the dominance of the canal itself.

In the United States, too, quarantine measures were the focus of political and health debates. Protection against imported diseases was traditionally considered a specific state problem rather than a general federal issue. Although in Europe it was cholera that accelerated the pace toward a more uniform quarantine system, in the United States other transmissible diseases – precisely, yellow fever in the second half of the nineteenth century – brought about in 1878 the passing of federal quarantine legislation by Congress. This legislation consisted of a corpus of laws that opened the way to the involvement of the federal government in widespread quarantine activities. Fourteen years later cholera, arriving from abroad, reached the United States, and the boost of this ‘new’ epidemic led to a revisiting of the corpus of laws previously established in order to attribute greater authority to the federal government with specific regard to the definition and implementation of quarantine requirements. As a consequence, local quarantine stations were gradually turned over to the federal government.

In 1893, both in the United States and in Europe, an agreement was reached regarding the fundamental issue of the notification of disease. This date is generally considered a turning point for the effective standardization of quarantine measures.

The Twentieth Century

From a historical point of view, quarantine has always been considered an effective public health measure adopted as a tool for managing infectious pathology outbreaks; in the course of time the attempt to control a large number of different transmissible diseases has involved quarantine, as has been previously illustrated for the plague, cholera, and yellow fever. In the twentieth century, other major epidemics have determined large-scale quarantine, namely tuberculosis and influenza. In the past the plague was termed the ‘Black Death’ because of its rapid insurgence, terrible epicrisis, and fatal conclusion; in the nineteenth and in the twentieth centuries, the ‘modern’ plague (the so-called ‘Great White Plague’) was considered tuberculosis (TB) (Conti et al., 2004). Use of the first powerful chemical agents against TB became widespread by the mid-twentieth century (streptomycin was put on the market in 1947). Before that date, for decades only direct and indirect quarantine measures had been implemented to contain the spread of the disease. Sanatoria and ‘preventoria’ had been established to provide preventive-therapeutic quarantine and isolation for people affected by TB. These institutions, on the one hand, represented a relatively simple instrument to set up to interrupt the pattern of transmission of this widespread pathology, and, on the other hand, they were official places where up-to-date (for the time) health care, if not effective therapy, was provided for TB patients. In the last 25 years of the nineteenth century and in the first 35 years of the following century, sanatoria spread both in North America and in Europe, with the specific function of isolating individuals affected by TB, as recommended by quarantine practice. In the absence of effective vaccines and drugs, quarantine, implemented in its broadest aspects, once again proved to be, in the case of tuberculosis in the course of the twentieth century, one of the most useful health interventions for such a widely disseminated disease.

However, from a historical and epidemiological perspective, it must also be recognized that quarantine implementation, in some of its exemplifications during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, had unintentional negative consequences that may be illustrated by referring to some episodes in the United States (Barbera et al., 2001). One of these damaging effects was the increased risk of disease transmission in the quarantined population, as in the instance of the quarantine issued by the New York City Port Authority to prevent and contain the diffusion of cholera. In Indiana, skepticism about government recommendations for the quarantine of smallpox led to episodes of urban violence, in particular when quarantine practice was not clearly explained by the authorities to the general public. Moreover, in the case of the quarantine established in San Francisco (1900) because of a diagnosis of the plague in the Chinese neighborhood, ethic bias caused notable and exclusive detriment to the business of the Chinese community. These historical facts should be carefully borne in mind for their instructive dimension, since they constitute magisterial lessons that every contemporary health system should clearly learn.

A great boost in scientific progress dates back to the first 40 years of the twentieth century, a period in which a profound, and appropriate, medicalization of quarantine measures emerged. At the very beginning of the twentieth century, in 1903, the expression ‘lazaretto’ was replaced by ‘health station’; this was because in Italy and France the classification of the population as sick, potentially sick, or (apparently) healthy attained solid medical value. In 1907 an International Office of Public Health was set up, to which, by 1909, at least 20 nations had joined. From a nosographical standpoint, in 1926 quarantine practices were extended to typhus and variola, and in 1928 the International Office issued additional precise rules of quarantining for all the different types of travelers. In effect, by that time, contrary to the past, sea and land were no longer the only areas of travel, since traveling by air was becoming more widespread. By the end of the twentieth century, air movements became the main transmission modalities for large-scale diseases requiring quarantine, such as SARS and avian influenza.

With the establishment of the World Health Organization (WHO), which replaced the International Office of Public Health, formal use of the term ‘quarantining diseases’ was replaced by terms indicating, on the one hand, diseases controlled by international health laws, such as cholera, plague, and yellow fever, and, on the other, diseases under surveillance, including typhus and poliomyelitis (Gensini et al., 2004). Nevertheless, even on a terminological level, quarantine, quarantine practices, and quarantining diseases have never died. In effect, although in the course of the twentieth century a number of U.S. quarantine stations were shut down following the effective use of vaccines and antibiotics against transmissible diseases, the essential epistemological and operational role of quarantine emerged again when SARS and avian influenza not only led to the restoration and empowerment of the existing quarantine stations, but also to the establishment of new and more modern quarantining centers across the States (Conti and Gensini, 2007).

In the United States, in the second half of the twentieth century, quarantine practices became a major commitment of the National Communicable Disease Center (NCDC, currently the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention). In the 1960s the NCDC was equipped with dozens of quarantine stations situated at every seaport and international airport. In the 1970s it modified its area of intervention from inspection to operational intervention, management, and regulation.

Still on this question of the reemergence and continued relevance of quarantine, it must be observed that, in the course of the twentieth century, many diseases have undergone quarantine measures. For example, the fundamental clinical, epidemiological, and epistemological model of TB quarantine has not lost its formative impact and operative functionality. This is so not only because of historical reasons (in 1913 a government-funded agency, the Medical Research Council, was established in the United Kingdom with the purpose of elaborating scientific research and political solutions to tuberculosis), but also, and more important from the current perspective, because TB, a disease that seemed to have almost disappeared in the Western world in the 1960s and 1970s, has again emerged significantly in the last few decades.

In 2003 the constitution of a new European body dedicated to surveillance, regulation, and research was proposed, also on account of the organizational and medical difficulties ensuing from the emergency of a ‘new-onset’ epidemic, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In this context quarantine achieved new popularity, as evidenced by the Fact Sheets (see Relevant Websites) issued by the CDC, in which it was explicitly written that “Quarantine is medically very effective in protecting the public from disease.” This extremely recent and sudden need for quarantine was prompted, with reference to SARS (but also to avian influenza), by the lack of a specific vaccine and targeted drugs, deficiencies that have evidenced how, even in the presence of highly technological medicine and health care, general (but not generic) preventive interventions are still fundamental. Among these, public, shared information, capillary health-care surveillance, and quarantining practices are vital. For SARS, the quarantine length, instead of the traditional time span of the past, as indicated by the term (it may be remembered that ‘quaranta’ is the Italian word for 40), has become 10 days, a period tailored on the incubation time of the pathogen agent of the syndrome. SARS has also represented a major challenge for health systems because (and this should be clearly highlighted, since the history of health has always much to teach humanity) the unexpected spread of this epidemiological condition has further put into question the real effectiveness of quarantine measures.

The outbreak of SARS in 2003 clearly showed how quickly new diseases may spread, thus deeply challenging community defenses. In the light of the historical lessons learned from SARS, and from avian influenza too, quarantine regulations were recently reviewed, and on 15 June 2007 the revised International Health Regulations (IHR) became operative. The IHR are a certified set of procedures and rules aimed at rendering the planet safer from global health threats. The revised IHR requirements include basic elements related to food and environmental safety and communicable diseases. Crucial for public health are the key points regarding notification, with the enhanced openness made necessary by today's world, and the establishment of fundamental public health procedures to optimize monitoring and response. These features document the modern interest for health measures connected with quarantine and isolation in their appropriate operational context. Instead of the maximum measures previously implemented with regard to particular diseases, these revised International Health Regulations provide recommendations which are context-specific. This paradigm shift shows how the specific boundaries of application of health-care practices require continual reconsideration.

Just like every other health measure, quarantine has intrinsic limits of implementation of which the scientific and the general communities must be institutionally and socially aware. Historically speaking, the legal and ethical limits of quarantine had already emerged in the 1980s, when AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) had broken out. Quarantine effectiveness varies in accordance with the initiation and length of limitation on travel between communities (Musto, 1986). Satisfactory templates for a precise determination of these limits of quarantine application are now available, and they are particularly interesting from a historical-scientific standpoint because they have already been applied to past epidemics. For example, to understand whether rates of travel are affected by informal quarantine policies, a compartmental model for the geographical spread of infectious diseases has been applied to quantitative information deriving from a Canadian historical record regarding the period of the Spanish influenza pandemic (1918–19). This same methodological model has been used to evaluate the impact of observed differences in travel on the diffusion of epidemics (Sattenspiel and Herring, 2003). The interesting retrospective results deriving from the application of models such as the one discussed here, to historical epidemics, need to be prospectively translated, on the basis of the best scientific evidence currently available, to address the contemporary and future effectiveness of human quarantine in simulated scenarios of epidemics. From a methodological point of view, this is one of the most appropriate strategies in preparing solutions to the limits of quarantine.

Conclusions and Perspectives

This article on the historical evolution of quarantine has presented, by means of documented examples, the scientific principles relevant to the effectiveness of quarantine, the logistic, economic, and political barriers through time to its correct implementation, and the health impact of local and large-scale quarantine.

Quarantine is one of the oldest and most effective health measures elaborated by mankind, but it should not be considered the solution to every epidemiological problem. As clearly indicated by the AIDS epidemic, it has various limits with regard to ethical and legal issues, as well as to epidemiological and organizational problems.

Overall, however, the basic conceptual and operational background of quarantine still has an epistemological and applicative value. The evidence-based current epidemiology and the evidence-based history of medicine show that the implementation of correct quarantine procedures is feasible and effective if tailored to geographical, social, and health conditions and when collaboration occurs among those concerned.

The historical persistence of the term ‘quarantine,’ etymologically indicating a 40-day period but now operatively defining variable time interventions for different communicable diseases, is the best documentation of the continuing value of this health measure through the centuries.

See also

Epidemiology, Historical; The History of Public Health in the Ancient World; Influenza, Historical; Plague, Historical; Yellow Fever, Historical

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Luisa Camaiora, BA., M.Phil., for her correction of the English.

Biography

Andrea A. Conti is a graduate in Medicine and Surgery and has a specialty in Internal Medicine, a Master in Epidemiology and Public Health, and a PhD in Clinical and Ageing Pathophysiology. He is Aggregate Professor and University Researcher of the History of Medicine and Bioethics in the University of Florence (Italy), and is Scientific Assistant of the Florence Health and Research Institute of the Don Carlo Gnocchi Foundation, a national Rehabilitation Centre. Dr. Conti has specific competence in the fields of the history of medicine and bioethics, in the methodology of clinical research, in evidence-based medicine and its teaching, in the elaboration and assessment of clinical practice and health management guidelines, in biostatistics, in health technology assessment, and in the electronic search for biomedical literature and ‘information management’. He is a member of the editorial board and/or reviewer of a number of Italian and international journals and is also member of various scientific societies; he is author of more than 250 scientific contributions on national and international biomedical publications (74 of them are indexed on PubMed (Medline) database – October 2007), particularly focused on the History of Medicine and Public Health and on clinical methodology and epidemiology.

Citations

- Barbera J., Macintyre A., Gostin L. Large-scale quarantine following biological terrorism in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:2711–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti A.A., Gensini G.F. The historical evolution of some intrinsic dimensions of quarantine. Medicina nei Secoli. 2007;19:173–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti A.A., Lippi D., Gensini G.F. Tuberculosis: A long fight against it and its current resurgence. Monaldi Archives of Chest Disease. 2004;61:71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmacini G. Editori Laterza; Bari, Italy: 2001. L'arte lunga. Storia della medicina dall'antichità a oggi. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D.P. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1999. International Law and Infectious Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- Frati P. Quarantine, trade and health policies in Ragusa-Dubrovnik until the age of George Armmenius-Baglivi. Medicina nei Secoli. 2000;12:103–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensini G.F., Conti A.A. The evolution of the concept of “fever” in the history of medicine: From pathological picture per se to clinical epiphenomenon (and vice versa) Journal of Infection. 2004;49:85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensini G.F., Yacoub M.H., Conti A.A. The concept of quarantine in history: From plague to SARS. Journal of Infection. 2004;49:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowelden J. The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 15th edn. Helen Hemingway Benton; Chicago, IL: 1979. Quarantine and Isolation; pp. 326–327. [Google Scholar]

- Mafart B., Perret J.L. History of the concept of quarantine. Medecine Tropicale. 2003;58:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglen K. Politics of quarantine in the 19th century. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2873. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musto D.F. Quarantine and the problem of AIDS. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1986;64(Suppl 1):97–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2nd edn. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2004. Oxford English Dictionary. CD-ROM Version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- Sattenspiel L., Herring D.A. Simulating the effect of quarantine on the spread of the 1918–19 flu in central Canada. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2003;65:1–26. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2002.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia Britannica Inc; Chicago, IL London: 1976[1909]. Webster's Third New International Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- Al-Ateeg F.A. Isolation versus quarantine and alternative measures to control emerging infectious diseases. Saudi Medical Journal. 2004;25:1337–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeletti L.R. Environment and political institutions between antiquity and contemporary medicine. Med Secoli. 1995;7:415–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker M.J. Compliance, coercion, and compassion: moral dimensions of the return of tuberculosis. Journal of Medical Humanities. 1996;17:91–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02276811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem A., Galwankar S. Avian influenza: Preparing for a pandemic. Journal of the Associated Physicians of India. 2006;54:563–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho W. Guideline on management of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361:1313–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilwein J.H. Some historical comments on quarantine: Part one. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 1995;20:185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1995.tb00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilwein J.H. Some historical comments on quarantine: Part two. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 1995;20:249–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1995.tb00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi D., Conti A.A. Plague, policy, saints and terrorists: A historical survey. Journal of Infection. 2002;44:226–228. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matovinovic J. A short history of quarantine (Victor C. Vaughan) University of Michigan Medical Center Journal. 1969;35:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen G. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1993. A History of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Sehdev P.S. The origin of quarantine. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:1071–1072. doi: 10.1086/344062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepin O.P., Yermakov W.V. International Universities Press; Madison, CT: 1991. International Quarantine. [Google Scholar]

- Slack P. The black death past and present. 2. Some historical problems. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1989;83:461–463. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuard S.M. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia, PD: 1992. A State of Deference: Ragusa/Dubrovnik in the Medieval Centuries. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 3rd annot. edn. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1983. International Health Regulations. [Google Scholar]

- Zambon M., Nicholson K.G. Sudden acute respiratory syndrome. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:669–670. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Relevant Websites

- 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Fact Sheet: Isolation and Quarantine.

- http://www.embase.com/ – Embase (Elsevier Publishing Group)

- http://www.iss.it/ – Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Italy)

- http://www.nhs.uk/ – National Health Service (NHS) in England (UK)

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi – PubMed, Medline (National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health, USA)

- http://www.who.int/en/ – World Health Organization (WHO)