Introduction

Few antiviral drugs are currently approved for treating respiratory virus infections and most of these are specific inhibitors of influenza viruses (Table 154-1 ). However, considerable progress is being made in the development of new therapeutics for other respiratory viruses.1 The emergence of new pathogens such as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has also led to screening efforts to identify new therapeutics.2, 3 Clinical studies to examine novel targets (Table 154-1), combinations designed to increase potency and reduce resistance emergence, therapeutic antibodies, and immunomodulatory agents selected to mitigate immunopathologic host responses, particularly for influenza, are in progress.4 Neutralizing antibodies have been proven effective for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease, although not for treatment,5 but specific neutralizing antibodies (convalescent plasma, monoclonals) appear to be promising for treating novel influenza and coronavirus infections. This chapter reviews the properties and clinical applications of currently approved antiviral agents.

TABLE 154-1.

Agents Used to Prevent and Treat Influenza6

| Class | Drug | USUAL ADULT DOSAGE* |

Dose Adjustment State | Suggested Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prophylaxis | Treatment | ||||

| M2 inhibitor |

Amantadine |

100 mg q12h |

100 mg q12h |

Age 1–9 years (yr) | 5 mg/kg to max of 150 mg in two divided doses |

| CrCl 30–50 mL/min | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| CrCl 15–30 mL/min | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| CrCl 10–15 mL/min | 100 mg q week | ||||

| CrCl 10 mL/min | 100 mg q week | ||||

| Age ≥65 yr | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| Rimantadine |

100 mg q12h |

100 mg q12h |

Age 1–9 yr* | 5 mg/kg to max of 150 mg in two divided doses | |

| CrCl <10 mL/min | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| Severe hepatic dysfunction | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| Age ≥65 yr | 100 mg q24h | ||||

| Neuraminidase inhibitor | Laninamivir |

20 mg QD × 2 days |

40 mg once |

Age <10 yr |

20 mg once |

| Oseltamivir† |

75 mg q24h |

75 mg q12h |

CrCl <30 mL/min‡ | Treatment: 75 mg q24h Prophylaxis: 75 mg every other day |

|

| ≤15 kg§ | 30 mg q12h (5 mL¶) | ||||

| 15–23 kg§ | 45 mg q12h (7.5 mL¶) | ||||

| 23–40 kg§ | 60 mg q12h (10 mL¶) | ||||

| >40 kg§ | 75 mg q12h (12.5 mL¶) | ||||

| Any weight, 2 weeks to <1 yr | 3 mg/kg q12hr (0.5 mL/kg¶) | ||||

| Peramivir |

NA |

300 mg once |

For patients with severe infection | 600 mg QD as a single or multi-dose regimen | |

| Children 6–17 yr | 10 mg/kg QD for 5 days (max of 600 mg QD) | ||||

| Children 180 days–5 yr | 12 mg/kg QD | ||||

| CrCl 31–49 mL/min§ | Adult: 150 mg QD Age 6–17 yr: 2.5 mg/kg QD§ Age 180 days–5 yr: 3 mg/kg QD |

||||

| CrCl 10-30 mL/min§ | Adult: 100 mg QD Age 6–17 yr: 1.6 mg/kg QD§ Age 180 days–5 yr: 1.9 mg/kg QD |

||||

| CrCl <10 mL/min | Adult: 100 mg on day 1 then 15 mg QD Age 6–17 yr: 1.6 mg/kg on day 1 then 0.25 mg/kg QD Age 180 days–5 yr: 1.9 mg/kg on day 1 then 0.3 mg/kg |

||||

| Intermittent hemodialysis (HD) (dose on HD days only) | ≥18 yr: 100 mg on day 1 then 100 mg 2 hours after HD Age 6–17 yr: 1.6 mg/kg on day 1 then 1.6 mg/kg 2 hours after HD Age 180 days–6 yr: 1.9 mg/kg on day 1 then 1.9 mg/kg 2 hours after HD |

||||

| Inhaled zanamivir‖ | 2 puffs (10 mg) twice a day for 5 days | 2 puffs (10 mg) twice a day for 5 days | No dose adjustment needed | ||

| iv zanamivir | NA | 600 mg q12h | Renal insufficiency | Loading dose (all patients): 600 mg Maintenance dosing based on CLcr/CLCRRT values: 80–50 mL/min: 400 mg 30–50 mL/min: 250 mg 15–30 mL/min: 150 mg <15 mL/min: 60 mg The interval between the initial dose and the start of maintenance dosing by CLcr/CLCRRT: 15–30 mL/min: 24 hrs <15 mL/min: 48 hrs |

|

CLcr/CLCRRT: Ratio of creatinine clearance to continuous renal replacement therapy clearance.

Duration of treatment is usually 5 days. Duration of prophylaxis depends on clinical setting.

Oseltamivir is indicated for prophylaxis in children ≥1 year old and for treatment in children in ≥2 weeks of age.

No treatment or prophylaxis dosing recommendations are available for patients undergoing renal dialysis.

Initial loading dose of 600 mg or age adjusted equivalent; maximum dose 600 mg QD.

Volume of suspension.

Zanamivir is indicated for prophylaxis in children ≥5 years old and for treatment in children ≥7 years old.

Recommendations based on those provided by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.4

M2 Inhibitors

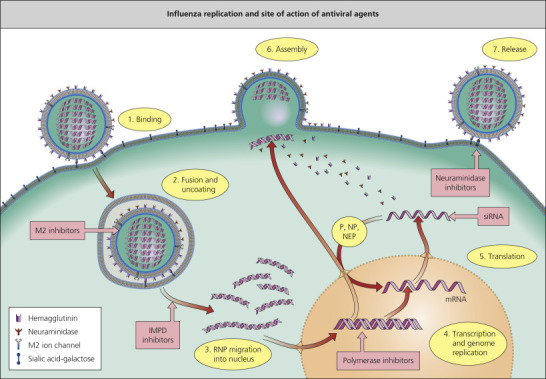

Amantadine (Symmetrel) and rimantadine (Flumadine) are symmetric tricyclic amines that specifically inhibit the replication of influenza A viruses at low concentrations (<1.0 µg/mL) by blocking the action of the M2 protein (Figure 154-1 ).7, 8, 9 Unfortunately, widespread resistance to all M2 inhibitors has been documented in circulating influenza A strains, and this class of agents is not currently recommended for the prevention or treatment of influenza.6

Figure 154-1.

Influenza replication and site of action of antiviral agents. IMPD, inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase; NEP, nuclear export protein; NP, nucleoprotein; P, polymerase; RNP, ribonuclear protein; siRNA, small inhibitory ribonucleic acid.

(Reprinted from Beigel J, Bray M. Current and future antiviral therapy of severe seasonal and avian influenza. Antiviral Res 2008; 78:91–102.)

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

Both drugs achieve peak levels 3-5 hours after ingestion (see detailed pharmacokinetic data in Table 154-2 ).10, 11, 12 Amantadine is excreted unchanged by the kidney while rimantadine undergoes extensive metabolism by the liver before being excreted by the kidney; as a result, dose adjustment with renal dysfunction is required (Table 154-2).

TABLE 154-2.

| Drug | Dose | Route | Cmax (µg/L) | Tmax (h) | AUC0–12 h (mg/mL•h) |

(h) (h) |

Bioavailability (Oral, %) | Protein Binding (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amantadine5, 6* |

200 mg | Oral (young) | 510 (140) | 2.1 (1) | 10.2 (3.4) | 14.4 (6) | 62–93 | 67 |

| 200 mg | Oral (elderly) | 800 (200) | 2.2 (2.1) | 17.6 (6.5) | 19 (9.1) | 54–100 | ||

| Rimantadine5, 6* |

200 mg | Oral (young) | 240 (70) | 4.6 (2.1) | 9.8 (4.5) | 36.5 (17.3) | 75–93 | 40 |

| 200 mg | Oral (elderly) | 250 (50) | 4.0 (2.4) | 11.5 (3.0) | 36.5 (14.5) | NA | ||

| Laninamivir | 40 mg | Inhaled | NA | NA | NA | 3 | ~15 | NA |

| Oseltamivir8* |

100 mg q12h | Oral (18–55 years) | 439 (40.8) | 3.5 (1) | 3.85 (0.6) | 6–10 | 79 | 42 |

| 100 mg q12h | Oral (≥65 years) | 575 (83.8) | 3.5 (1.4) | 4.94 (1.0) | – | – | ||

| Peramivir | 600 mg | Intravenous | 46.8 | NA | 102.7 | 20 | NA | <30 |

| Zanamivir7† | 16 mg | Inhaled | 29 (23–69) | 0.75 (0.08–2) | 0.03 (0.02–0.06) | 3.6 (2.2–9.4) | 4–17 | 10 |

| 16 mg | Inhaled | 54 (34–96) | 0.75 (0.25–1) | 0.16 (0.02–0.32) | – | 4–17 | ||

Cmax, maximum serum drug concentration; Tmax, time to Cmax;  , serum elimination half-life; AUC, area under the curve for serum drug concentration versus time for the dose interval; bioavailability, percentage of intravenous Cmax.

, serum elimination half-life; AUC, area under the curve for serum drug concentration versus time for the dose interval; bioavailability, percentage of intravenous Cmax.

Values are mean (SD).

Values are median (range).

Route of Administration and Dosage

Amantadine and rimantadine come as 100 mg tablets and a syrup formulation (50 mg/5 mL). In adults, the usual dose for treatment or prevention of influenza A infection is 100 mg q12h for both drugs (see Table 154-2).

Indications

The current recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) should be consulted before using this class clinically, including in infections by novel strains of influenza-like avian H5N1. A triple drug regimen (amantadine, ribavirin, oseltamivir) is currently under study for influenza A infections, including those due to adamantane-resistant strains.6 When used against susceptible strains, both agents are 70–90% effective in preventing infection and reduce duration of fever and symptoms when used for treatment.15, 16, 17 Dosage in special circumstances is summarized in Table 154-1.

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

The most common side-effects of the M2 inhibitors are minor central nervous system (CNS) complaints (anxiety, difficulty concentrating, insomnia, dizziness, headache and jitteriness) and gastrointestinal upset, which are particularly prominent in the elderly and those with renal failure.11 Patients who receive amantadine may develop antimuscarinic effects, orthostatic hypotension and congestive heart failure. Rates of adverse effects are lower for rimantadine than amantadine.11, 18 Given drug–drug interactions, care should be used when co-administering either agent with antihistamines or anticholinergic drugs, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, triamterene–hydrochlorothiazide, quinine, quinidine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, antidepressants and minor tranquilizers.19

Resistance

Cross-resistance to both agents occurs as the result of single amino acid substitutions in the transmembrane portion of the M2 protein.9 The resistant virus appears to retain wild-type pathogenicity and causes an influenza illness indistinguishable from susceptible strains. Resistance has emerged within 2–4 days after the start of therapy in up to 30% of patients infected with initially susceptible strains.11 Emergence of resistant variants may be associated with protracted illness and shedding in immunocompromised hosts20; spread to contacts causes failures of antiviral prophylaxis in nursing homes and households.11

Neuraminidase Inhibitors

Influenza A and B viruses possess a surface glycoprotein with neuraminidase activity whereas influenza C viruses do not (Figure 154-1). This enzyme cleaves terminal sialic acid residues from various glycoconjugates and destroys the receptors recognized by viral hemagglutinin. This activity is essential for release of virus from infected cells, for prevention of viral aggregates, and for viral spread within the respiratory tract.21 Oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, a prodrug of the active carboxylate), laninamivir (Inavir®), peramivir (Rapiacta®, Peramiflu®) and zanamivir (Relenza®) are sialic acid analogs that potently and specifically inhibit influenza A and B neuraminidases by competitively and reversibly interacting with the active enzyme site.22, 23 These drugs are active against all nine influenza neuraminidase subtypes in nature. Oseltamivir and zanamivir are globally available, while laninamivir is approved in Japan and peramivir is approved in China, Japan, South Korea and the USA.

Laninamivir

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

Laninamivir octanoate (CS-8958) is a prodrug that is converted in the airway to laninamivir (R-125489), the active neuraminidase inhibitor and is retained at concentrations that exceed the IC50 for most influenza neuraminidases for at least 240 hours (10 days) after a single inhalation of 40 mg.24 Only 15% of the drug is systemically absorbed after inhalation. Laninamivir has excellent in vitro activity against wild-type influenza A and B viruses currently circulating, including those H1N1 viruses containing H275Y mutations in the neuraminidase.

Route of Administration and Dosage

Laninamivir octanoate (CS-8958) is currently only approved in Japan and is available as a 20 mg dry powder inhaler. It is undergoing clinical investigation outside of Japan at present.

Indications

Prophylaxis

Laninamivir is approved for the prevention of influenza in adults and children ≥ 10 years of age; a single inhalation of 20 mg daily for 2 days is recommended for this indication. Among household contacts of an index patient with influenza, 2 and 3 days of laninamivir 20 mg daily was associated with a 77% and 78% protective efficacy, respectively, compared with placebo.25

Treatment

Laninamivir is approved for the treatment and prevention of influenza A and B infection in Japan. For treatment, laninamivir is approved as a single inhalation of 40 mg for individuals ≥10 years of age and 20 mg for children less than 10 years of age. Laninamivir was associated with more rapid time to alleviation of influenza illness due to infections by seasonal H1N1 virus with the H275Y substitution in children compared to a standard 5-day oseltamivir regimen, while studies in adults demonstrated noninferiority versus oseltamivir in such patients.26, 27 Laninamivir demonstrates a similar duration of fever in ambulatory children when compared to patients treated with zanamivir.28, 29

Dosage in Special Circumstances

No dose adjustment is currently indicated in any patient population.

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

Clinical studies in Asia found similar rates of nausea in laninamivir octanoate- and oseltamivir- treated patients, lower rates of vomiting in the laninamivir octanoate arm, and similar to slightly higher rates of diarrhea in laninamivir octanoate arms.26, 27 Dizziness was seen in 0.9–1.8% of laninamivir octanoate-treated patients but not oseltamivir-treated patients.26 Laninamivir was not associated with significant bronchospasm or other respiratory adverse effects in patients with chronic respiratory disease.30

Oseltamivir

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

Oral oseltamivir ethyl ester is well absorbed and rapidly cleaved by esterases in the gastrointestinal tract, liver or blood. The bioavailability of the active metabolite, oseltamivir carboxylate, is estimated to be ~80% in previously healthy persons (see Table 154-3 ).13 The plasma elimination half-life is 6–10 hours but is more prolonged in the elderly, although dose adjustments are not generally necessary. Administration with food appears to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal upset without decreasing bioavailability. Both the prodrug and parent are eliminated primarily unchanged through the kidney by glomerular filtration and anionic tubular secretion. The dose should be reduced by half for patients with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min, and further reductions when clearance is below 10 mL/min.31 Distribution is not well characterized in humans, but peak bronchoalveolar lavage, middle ear fluid and sinus fluid levels are similar to plasma levels.13 Recent data suggest that significant relationships exist between oseltamivir carboxylate AUC0–24 and area under the curve (AUC) of symptom scores, time to alleviation of composite symptom scores, and time to cessation of viral shedding in experimentally infected volunteers.32

TABLE 154-3.

Summary of Antiviral Agents in Advanced Clinical Development for Respiratory Viruses

| Drug | Spectrum | Target of Antiviral Action | Antiviral Resistance in Clinical Isolates | Route of Dosing | Pharmacokinetic Properties | Principal Adverse Effects | Clinical Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zanamivir | Influenza A + B | Enzymatic action of viral NA | Rare | iv | Renal excretion with plasma elimination half-life of ~2 hrs; dose adjustment required for renal insufficiency | iv delivery avoids bronchospasm risk with aerosol treatment | Significant antiviral effects in severely ill A(H1N1)pdm09-infected patients not responding to oseltamivir. |

| Favipiravir/T-705 | Influenza A, B, C and other RNA viruses | Influenza RNA polymerase; lethal mutagenesis | Not reported to date | Oral | Intracellular ribosylation and phosphorylation to its active triphosphate form. Good oral bioavailability; parent compound metabolized to inactive moiety by and also inhibitor of aldehyde oxidase >65% renally excreted as metabolite by 48 hrs | Dose-related hyperuricemia; teratogenic in preclinical testing – restricted use in pregnancy | BID dosing regimen more effective than TID regimen. Approved in Japan for use in novel or drug-resistant influenza infections. No data from severe influenza |

| DAS181 | Influenza A + B, PIV | Host cell receptor for viral HA. Sialidase removes both the human-like a2,6- and avian-like a2,3-linked sialic acids from cellular receptors | Not reported to date | Inhaled | In ex vivo human airway epithelium and human bronchial tissue, the inhibitory effect of DAS181 treatment lasts ≥2 days. Tracheobronchial delivery and degree of systemic absorption dependent on particle size | Elevated alkaline phosphatase due to reduced clearance, no associated increases in transaminases | Reduced pharyngeal influenza virus detection but little clinical benefit in treating uncomplicated influenza; unstudied in serious influenza. Case reports of antiviral effectiveness and clinical improvement in serious PIV illness in transplant recipients; RCT in progress |

| Nitazoxanide | A + B and other RNA viruses | Influenza HA maturation; possible immune-modulatory and other antiviral mechanism of action | Not reported to date | Oral | Metabolized by plasma esterases metabolize to its active desacetyl derivative tizoxanide, which undergoes glucuronidation and urinary elimination with elimination half-life of ~7 hrs. Tizoxanide is highly bound by (>99%) plasma proteins. Need for dose adjustments uncertain | GI; respiratory distress | Shorter duration of viral replication and illness compared to placebo in phase 2 RCT in uncomplicated influenza; evidence for clinical benefit in influenza-like illness without detectable virus by RT-PCR |

| VX-787 | Influenza A | Influenza RNA polymerase | Common | Oral | Not reported | Antiviral efficacy and associated reduction in illness measures in experimentally infected volunteers; no studies in natural influenza reported to date | |

| AVI-7100 | Influenza A | M1 (matrix) and M2 (ion channel) genes | Not reported | iv | Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer with three modified linkages; active after topical or iv dosing in ferrets | Not reported | Phase 1 study of iv formulation in progress |

| Brincidofovir (CMX-001) | Adenovirus, other DNA viruses | Viral DNA polymerase | Infrequent | Oral | Infrequent dosing (weekly or bi-weekly) possible due to high intracellular concentration and long intracellular half-life (up to 4-6.5 days) of the active antiviral cidofovir-diphosphate | Diarrhea, other GI symptoms; transaminase elevations | Antiviral effects in case series of transplant recipients intolerant of or failing cidofovir for serious adenovirus infection and with bi-weekly dosing in RCT for pre-emptive treatment of adenoviremia; follow-up RCT in progress |

| GS-5806 | RSV | F protein-fusion | Not reported but common in preclinical studies with other fusion inhibitors | Oral | Fusion inhibitor | Limited clinical data | Protective effects in experimentally infected volunteers; placebo-controlled RCTs in progress for treating elderly hospitalized with RSV and for transplant recipients with upper or lower respiratory illness due to RSV |

| ALS-8176 | RSV | Polymerase | Not reported | Oral | Nucleoside analog | Not reported | Phase 1 studies in healthy adults completed; phase 2 in progress |

| MDT-637 (formerly VP-14637) | RSV | F protein-fusion | Not reported but common in preclinical studies with other fusion inhibitors | Inhaled | Fusion inhibitor | Not reported | Phase 1 studies up to 10 days dosing in healthy adults completed |

| ALN-RSV01 | RSV | Nucleocapsid gene | Not reported | Inhaled | Small interfering RNA | Generally well-tolerated in studies to date | Protective against RSV infection in experimental human RSV challenge. Two placebo- controlled phase 2 RCTs in RSV-infected lung transplant patients found reduced incidence of new or progressive BOS |

Note: this table summarizes small molecular weight inhibitors in active clinical development and does not include combinations, biologics like therapeutic antibodies, or immunomodulators.

Abbreviations: BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; HA, hemagglutinin; NA, neuraminidase; NAI, neuraminidase inhibitor; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RCT, randomized, controlled trial.

Route of Administration and Dosage

Oseltamivir is available for oral delivery only. Oseltamivir comes as 30, 45, and 75 mg tablets and as a white tutti-frutti-flavored suspension (360 mg oseltamivir base for a final concentration of 6 mg/mL). The approved adult dose for treatment is 75 mg twice daily for 5 days and for prophylaxis is 75 mg once daily. Pediatric dosing is based on weight and is outlined in Table 154-2.

Indications

Prophylaxis

Oseltamivir is indicated for the prevention of influenza infection in patients ≥1 year, with dosing once a day. The efficacy of once-daily oseltamivir 75 mg for 6 weeks in preventing influenza illness in healthy, nonimmunized adults was 84% and in preventing influenza infection irrespective of symptoms was 50%.13 In immunized nursing home residents, the efficacy of prophylaxis was 92% against illness compared to placebo.23 Somewhat lower efficacy was seen in a household-contact prophylaxis study, and protection against influenza has been shown in children.33 Seasonal prophylaxis of high-risk immunocompromised patients was documented to provide ~80% protective efficacy against RT-PCR-confirmed influenza illness.34 Caution should be used when prescribing oseltamivir for prophylaxis in patients exposed to an index case as prophylaxis has been associated with emergence of resistant mutants;35 empiric therapy or monitoring is generally recommended in these cases as a result.

Postexposure prophylaxis in nursing home influenza outbreaks is advised for 14 days or for at least 7 days after the last culture-confirmed illness in the ward or building is effective; this regimen should be given with concomitant influenza vaccination for those not previously provided. Seasonal prophylaxis, during the 4–8 weeks of peak influenza virus circulation within the community, can be used for protection of high-risk patients who cannot tolerate immunization, who do not develop an adequate immune response to vaccine, or when the strain circulating in the community does not match the vaccine strain.

Treatment

Oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily for 5 days when started within the first 2 days of symptoms was associated with a shorter time to alleviation of uncomplicated influenza illness (29–35 hours shorter) and with reductions in severity of illness, duration of fever, time to return to normal activity, quantity of viral shedding, duration of impaired activity, and complications leading to antibiotic use, particularly bronchitis, compared to placebo in previously healthy adults.6, 16, 36 One recent study in Bangladesh suggests that oseltamivir may have efficacy up to 72 hours after symptom onset in children.37 Pediatric studies enrolling children as young as 2 weeks of age demonstrated that oseltamivir is safe and is associated with significantly reduced illness duration and severity, time to resumption of full activities, and the occurrence of complications leading to antibiotic use, particularly acute otitis media.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Most existing literature on the safety and efficacy of oseltamivir in elderly or high-risk persons, including those with underlying cardiopulmonary conditions or immunodeficiency comes from observational studies43, 44, 45, 46 and suggests that among such high risk and hospitalized individuals, there is a benefit to starting antiviral therapy through at least 5 days after symptom onset with the greatest benefit in patients started within 48 hours after symptom onset.47 All of the studies in hospitalized adults suggest that early therapy is associated with reduced incidence of lower respiratory tract complications, requirement for ICU-level care, duration of illness, duration of shedding and mortality.6, 16, 45, 46, 48

Dosage in Special Circumstances

The usual oseltamivir dose should be reduced to 75 mg once a day for treatment and 75 mg every other day or 30 mg of suspension daily for prophylaxis when a patient has a creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min. Doses of oseltamivir should be given after hemodialysis; detailed dosing for renal insufficiency and renal replacement therapy is available in Table 154-3. The safety and pharmacokinetics in patients with hepatic impairment have not been evaluated. Several studies in pregnancy suggest that oseltamivir is likely safe and provides clear therapeutic benefit to pregnant women infected with influenza.49, 50, 51 There are conflicting data about optimal dosing of oseltamivir in pregnant women, with some studies suggesting need for higher doses (75 mg TID), while others suggest no dose adjustment is needed.52, 53, 54 Current guidelines recommend treating pregnant women with influenza infection with one of the approved neuraminidase inhibitors. The recommended pediatric dosage is listed in Table 154-2.

Doubling the treatment dose of oseltamivir in hospitalized influenza patients does not appear to increase virologic efficacy, except perhaps for influenza B infections, or clinical effectiveness, although one ICU-based RCT reported that tripling the standard dose was associated with acceleration of viral RNA clearance from the respiratory tract.55, 56, 57

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

Oral oseltamivir is generally well tolerated and no serious end-organ toxicity has been found in controlled clinical trials. Oseltamivir is associated with nausea, abdominal discomfort and, less often, emesis in a minority of treated patients. Nausea and vomiting occur at approximately 10–15% excess frequency in oseltamivir recipients. Gastrointestinal complaints are typically mild-to-moderate in intensity, usually resolve despite continued dosing, and are ameliorated by administration with food. Clinical studies comparing 75 mg and 150 mg twice daily found similar frequencies of adverse events with the two doses. Other infrequent possible adverse events include insomnia, vertigo and fever. Postmarketing reports suggest that oseltamivir may be associated rarely with skin rash, hepatic dysfunction or thrombocytopenia. Additionally, there have been reports of abnormal neurologic and behavioral symptoms which have rarely resulted in deaths among mostly children; most of these reports have come from Japan. Existing data suggest that these events are more likely secondary to influenza infections than oseltamivir therapy.58, 59 It is currently recommended that patients be monitored closely for behavioral abnormalities.

No clinically significant drug interactions have been recognized to date, including studies with amoxicillin, aspirin and acetaminophen. No interactions with the cytochrome P450 enzymes occur in vitro and oseltamivir does not affect steady-state pharmacokinetics of commonly used immunosuppressive agents.60 However, probenecid blocks tubular secretion and doubles the half-life of oseltamivir. Protein binding is below 10%. Oseltamivir does not affect the immunogenicity of concomitant inactivated virus vaccine but might impair the immunogenicity of concurrent live-attenuated intranasal influenza vaccine.

Peramivir

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

Peramivir has low oral bioavailability and is therefore delivered intravenously. Peramivir achieves exceptionally high maximum concentrations (~45 000 ng/mL after 600 mg intravenous dose) with excellent concentrations of drug in the nasal and pharyngeal secrections.61 Peramivir is predominately eliminated unchanged by renal excretion with a plasma terminal elimination half-life of 12–25 hours.41, 62 Peramivir has comparable or lower activity in vitro against influenza A and B viruses than oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir.63

Route of Administration and Dosage

Peramivir is available in 150 mg and 300 mg solutions for intravenous use.

Indications

Peramivir randomized clinical trials have been conducted in previously healthy adults and children infected with uncomplicated influenza. When compared to placebo, a single 300–600 mg infusion of peramivir was associated with a significantly shorter time to alleviation of symptoms, significantly shorter time to resumption of their usual activities, and more rapid clearance of virus.64 Another study found that a single 300–600 mg infusion of peramivir was noninferior to 5 days of oral oseltamivir 75 mg BID in a season when many of the viruses were resistant to oseltamivir as the result of the H275Y mutation; these data question the efficacy of peramivir in the management of viruses with the H275Y mutation.65 In a study comparing 5 days of 200 mg or 400 mg QD of peramivir with oral oseltamivir 75 mg BID in hospitalized adults, there was a trend toward more rapid resumption of usual activities in peramivir-treated patients and greater reductions of influenza B viral titers in the nasopharynx than oseltamivir over the first 48 h.

Dosage in Special Circumstances

Since peramivir is renally cleared, dosing must be adjusted based on renal function (see Table 154-3). There are limited data to guide dosing of peramivir in children, particularly among neonates.66 Available data and models suggest that patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis need dose adjustment (see Table 154-3).66 Dosing of patients on continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) should be based on CRRT clearance.67 There is limited dosing information for patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Based on modeling data and predicted drug concentrations, it is recommended that children ≥181 days and ≤ 5 years receive 12 mg/kg daily (daily maximum of 600 mg/dose), infants 91–180 days receive 10 mg/kg daily, infants 31–90 days receive 8 mg/kg daily, and neonates ≤30 days receive 6 mg/kg daily. No dose adjustments are needed for hepatic impairment.

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

Recognized adverse events associated with the administration of peramivir are diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and neutrophil count decreased; other less common adverse events observed in studies to date include dizziness, headache, somnolence, nervousness, insomnia, feeling agitated, depression, nightmares, hyperglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated blood pressure, cystitis, ECG abnormalities, anorexia, and proteinuria.68

Zanamivir

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

The oral bioavailability of zanamivir is low (<5%), and most clinical trials have used intranasal or dry powder inhalation delivery. Following inhalation of the dry powder, approximately 7–21% is deposited in the lower respiratory tract and the remainder in the oropharynx.14, 69 Median zanamivir concentrations are above 1000 ng/mL in induced sputum 6 hours after inhalation and remain detectable up to 24 hours later. The peak plasma concentration averages 46 µg/L after a single 16 mg inhalation of zanamivir. The proprietary inhaler device for delivering zanamivir is breath-actuated and requires a cooperative patient.70

Intravenous zanamivir displays linear dosing kinetics and the volume of distribution is approximately equivalent to that of extracellular water (16L).14 Intravenous zanamivir provides high peak plasma concentrations (~35 000 ng/mL after 600 mg dose in adults).71 90% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine with an elimination half-life of approximately 2 hours. Intravenous zanamivir clearance is highly correlated with renal function (CL ≅ 7.08 + 0.826 ⋅ CLCR).72

Route of Administration and Dosage

Zanamivir is delivered by inhalation with a proprietary breath-activated device (Diskhaler®). The usual adult treatment dose is two inhalations (10 mg) twice a day for 5 days. Intravenous zanamivir is currently in advanced clinical development and available by compassionate use.

Indications

Prophylaxis

Zanamivir is indicated as once-daily inhalations for the prevention of influenza in patients >5 years old. Once-daily inhaled zanamivir for 4 weeks was 84% efficacious in preventing laboratory-confirmed illness with fever and 31% effective in preventing influenza infections, irrespective of symptoms.69 When used for postexposure prophylaxis, inhaled zanamivir for 10 days reduced the risk of secondary influenza illness by 79% in households.69 In nursing homes experiencing influenza outbreaks, inhaled zanamivir was more effective for prevention of influenza A illness than oral rimantadine, in part because of frequent resistance emergence to the M2 inhibitor.69

Treatment

In the USA, zanamivir is indicated for the treatment of uncomplicated acute illness due to influenza A and B viruses in adults and pediatric patients 7 years and older who have been symptomatic for no more than 2 days.9 Inhaled zanamivir in adults has consistently shown at least 1 fewer day of disabling influenza symptoms, and most studies have found a reduction in the number of nights of disturbed sleep, in time to resumption of normal activities, and in the use of symptom relief medications.6, 16 Similar therapeutic benefits have also been shown in children aged 5–12 years old.73 Zanamivir has also been associated with a 40% reduction in lower respiratory tract complications of influenza leading to antibiotics, particularly bronchitis and pneumonia.74 Zanamivir appears generally well tolerated and effective in treating influenza in patients with mild-to-moderate asthma or, less often, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.74, 75

Intravenous zanamivir is in advanced clinical development and has been used in seriously ill influenza patients, especially those with suspected oseltamivir-resistant variants. Most of the emergency IND (eIND) use of intravenous zanamivir were in patients who were clinically failing other antiviral therapy with at least 25% of patients having proven or clinically suspected resistance to oseltamivir.76 Available data from patients who were treated under eIND demonstrated that among those with reported outcomes, 10.5% died despite therapy.76 A phase 2 study in critically ill pandemic 2009 H1N1 patients found that treatment was associated with significant antiviral effects, even though therapy was initiated a median of 4.5 days after symptom onset. In patients with influenza detected on initial sample, 2 days of therapy was associated with a median 1.42 log10 copies/mL decline in viral load.71 There were no drug-related trends in safety parameters identified. The 14- and 28-day all-cause mortality rates were 13% and 17%, respectively.71 A phase 3 study comparing iv zanamivir and oral oseltamivir in hospitalized adults is currently in progress.

Dosage in Special Circumstances

Although the plasma elimination half-life increases with creatinine clearance ≤70 mL/min, drug accumulation is negligible after inhalation and dose adjustment is not necessary for renal or hepatic dysfunction. Certain populations, particularly very young, frail or cognitively impaired patients, may have difficulty using the drug delivery system.70

Intravenous zanamivir requires dose adjustment for renal insufficiency. All patients should receive an initial 600 mg loading dose. The maintenance dose and dosing interval are reduced with worsening renal function (see Table 154-2).71, 72

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

Topically applied zanamivir is generally well tolerated in controlled studies, including those involving patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.75 Postmarketing reports indicate that bronchospasm may be an uncommon but potentially severe problem, particularly in patients with acute influenza and underlying reactive airway disease.6 Anecdotal reports of hospitalization and fatality indicate that inhaled zanamivir should be used cautiously in such patients.6

Low bioavailability is associated with low exposure to circulating zanamivir, and no clinically significant drug interactions have been recognized. In vitro studies suggest that zanamivir does not inhibit or induce cytochrome P450 enzymes. The drug does not affect the immunogenicity of concomitant immunization with inactivated virus vaccines but effects on intranasal, live-attenuated vaccine have not been studied. One randomized control trial in ambulatory adults found that the combination of inhaled zanamivir and oral oseltamivir was less effective than oseltamivir monotherapy.77 Zanamivir is not associated with teratogenic effects in preclinical studies (FDA pregnancy category C) and should be considered as an option in pregnant women with proven influenza.78

Neuraminidase Inhibitor Resistance

Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in vitro results from mutations in the viral hemagglutinin and/or neuraminidase.79, 80 In the hemagglutinin variants, mutations in or near the receptor binding site make the virus less dependent on neuraminidase action, whereas neuraminidase mutations directly affect interaction with the inhibitors. The altered neuraminidases typically show reduced activity or stability, and the mutated viruses usually have decreased infectivity in animals.79, 80 The particular neuraminidase mutation determines the degree of resistance and cross-resistance (i.e. H275Y cause high-level resistance to oseltamivir but not zanamivir; R292K results in reduced susceptibility to both oseltamivir and zanamivir).79, 80 Oseltamivir-resistant variants have been recovered from <1% of treated adults and about 4% of treated children.22 Assessment for resistance can be assessed by sequencing of the HA or NA gene or phenotypic testing.79, 80

Ribavirin

Ribavirin (Virazole®, Rebetol®) is a guanosine analog with a wide range of antiviral activity including influenza viruses, RSV and parainfluenza viruses. Ribavirin is rapidly phosphorylated by intracellular enzymes and the triphosphate inhibits influenza virus RNA polymerase activity and competitively inhibits the guanosine triphosphate-dependent 5′-capping of influenza viral messenger RNA. In addition, ribavirin depletes cellular guanine pools81, 82 and may inhibit virus replication by lethal mutagenesis.

Pharmacokinetics and Distribution

Oral ribavirin has a bioavailability of 33–45% in adults and children and achieves peak plasma concentration of 0.6 µg/mL 1–2 hours after ingestion of a 400 mg dose in adults. Ribavirin has a short initial (0.3–0.7 hour) and a long terminal (18–36 hours) phase half-life and is eliminated by hepatic metabolism and renal clearance.83 After aerosol administration, plasma levels increase with exposure and range from 0.2 to 1 µg/mL. Respiratory secretions have levels up to 1000 µg/mL, which decline with a half-life of 1.4–2.5 hours.

Route of Administration and Dosage

Ribavirin comes in three formulations: oral (approved for combined use in hepatitis C), intravenous (investigational in USA) and aerosol. Ribavirin for aerosolization is available as a 6 g/100 mL solution which is diluted to a final concentration of 20 mg/mL and delivered by small particle aerosol for 12–18 hours with a proprietary device (SPAG-2 nebulizer). A higher concentration of aerosol solution (60 mg/mL) has been given over 2 hours three times daily in some studies and appears well tolerated.84 Ribavirin also comes in 200 mg tablets and sterile solution for injection.

Indications

Ribavirin aerosol is currently indicated for the treatment of severe RSV in children. Trials of aerosolized ribavirin for the treatment of severe RSV infection in infants have shown no consistent effect on duration of hospitalization time, mortality or on pulmonary functions.85 Current guidelines recommend that aerosolized ribavirin be considered in the treatment of high-risk infants and young children, as defined by congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, immunodeficiency states, prematurity and age <6 weeks, as well as for those hospitalized with severe illness.85 Aerosolized ribavirin has shown minimal efficacy in treating influenza in hospitalized children.86

Ribavirin has also been studied for the treatment of RSV and parainfluenza virus infections in immunocompromised patients. Intravenous ribavirin appears to be ineffective in reducing RSV-associated mortality in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients with RSV pneumonia; there may be benefit among lung transplant recipients.87 Aerosolized ribavirin may provide benefit in selected patient groups with less severe RSV disease. Survival was improved when treatment was started before respiratory failure or when infection was limited to the upper respiratory tract.88 Observational studies suggest that combination therapy with antibodies (either intravenous immunoglobulin, RespiGam or palivizumab) appears more effective, particularly when started before severe respiratory distress.88 Oral ribavirin has been tried in the management of RSV with variable success.89 In the management of parainfluenza virus in bone marrow transplant recipients, two case series found that aerosolized ribavirin failed to improve 30-day mortality or reduce the duration of viral replication relative to no treatment.90

Dosage in Special Circumstances

Systemic ribavirin is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <50 mL/min and the dose should be reduced by one-third for patients under 10 years of age. Dose adjustment is needed if there is a substantial decline in hematocrit and the drug should be discontinued if the hemoglobin drops below 8.5 g/dL. There is a fixed combination of oseltamivir, amantadine and ribavirin that is active in vitro against susceptible and resistant strains and shows promise in clinical management of influenza infections.91, 92

Adverse Reactions and Interactions

Systemic ribavirin can cause a dose-related extravascular hemolytic anemia and, at higher doses, suppression of bone marrow release of erythroid elements. Aerosolized ribavirin can cause bronchospasm, mild conjunctival irritation, rash, psychological distress if administered in an oxygen tent and, rarely, acute water intoxication. Bolus intravenous administration may cause rigors. Antagonism of both drugs may occur when ribavirin is combined with zidovudine. Ribavirin is contraindicated in pregnant women and in male partners of women who are pregnant because of teratogenicity of the drug. Pregnancy should be avoided during therapy and for 6 months after completion of therapy in both female patients and in female partners of male patients taking ribavirin (pregnancy category X).

![]() References available online at

expertconsult.com

.

References available online at

expertconsult.com

.

Key References

- Aoki F.Y., Sitar D.S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amantadine hydrochloride. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:35–51. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval X., van der Werf S., Blanchon T. Efficacy of oseltamivir-zanamivir combination compared to each monotherapy for seasonal influenza: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore A.E., Fry A., Shay D. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza – recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep/CDC. 2011;60:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden F.G. Advances in antivirals for non-influenza respiratory virus infections. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl. 3):36–43. doi: 10.1111/irv.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison M.G., Szakaly P., Shapira M.Y. Efficacy and safety of oral oseltamivir for influenza prophylaxis in transplant recipients. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:955–964. doi: 10.3851/IMP2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser L., Keene O.N., Hammond J.M. Impact of zanamivir on antibiotic use for respiratory events following acute influenza in adolescents and adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3234–3240. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyser L.A., Karl M., Nafziger A.N. Comparison of central nervous system adverse effects of amantadine and rimantadine used as sequential prophylaxis of influenza A in elderly nursing home patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1485–1488. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberlin D.W., Acosta E.P., Prichard M.N. Oseltamivir pharmacokinetics, dosing, and resistance among children aged <2 years with influenza. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:709–720. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Ison M.G. Editorial commentary. ‘Late’ treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors for severely ill patients with influenza: better late than never? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1205–1208. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie J.K., Yang S., Acosta M. Treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors for critically ill patients with influenza A (H1N1)pdm09. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1198–1204. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty F.M., Man C.Y., van der Horst C. Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous zanamivir treatment in hospitalized adults with influenza: an open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:542–550. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.T., Fry A.M., Gubareva L.V. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:159–173. doi: 10.3851/IMP2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J.T., Smee D.F., Barnard D.L. Efficacy of combined therapy with amantadine, oseltamivir, and ribavirin in vivo against susceptible and amantadine-resistant influenza A viruses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J.N., Chemaly R.F. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2755–2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-263400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South East Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research N Effect of double dose oseltamivir on clinical and virological outcomes in children and adults admitted to hospital with severe influenza: double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f3039. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M. Laninamivir and its prodrug, CS-8958: long-acting neuraminidase inhibitors for the treatment of influenza. Antivir Chem Chemoth. 2010;21:71–84. doi: 10.3851/IMP1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Hayden F.G. Advances in antivirals for non-influenza respiratory virus infections. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl. 3):36–43. doi: 10.1111/irv.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan J.F., Chan K.H., Kao R.Y. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect. 2013;67:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Wilde A.H., Jochmans D., Posthuma C.C. Screening of an FDA-Approved Compound Library Identifies Four Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Replication in Cell Culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4875–4884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden F.G. Newer influenza antivirals, biotherapeutics and combinations. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl.1):63–75. doi: 10.1111/irv.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geevarghese B., Simoes E.A. Antibodies for prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:201–211. doi: 10.3851/IMP2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiore A.E., Fry A., Shay D. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza – recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep/CDC. 2011;60:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay A.J., Wolstenholme A.J., Skehel J.J. The molecular basis of the specific anti-influenza action of amantadine. EMBO. 1985;4:3021–3024. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto L.H., Holsinger L.J., Lamb R.A. Influenza virus M2 protein has ion channel activity. Cell. 1992;69:517–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90452-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay A.J., Zambon M.C., Wolstenholme A.J. Molecular basis of resistance of influenza A viruses to amantadine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986;18(Suppl. B):19–29. doi: 10.1093/jac/18.supplement_b.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki F.Y., Sitar D.S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amantadine hydrochloride. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:35–51. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden F.G., Aoki F.Y. Amatadine, Rimantadine and Related Agents. In: Barriere S.L., editor. Antimicorbial Therapy and Vaccines. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1999. pp. 1344–1365. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden F.G., Minocha A., Spyker D.A. Comparative single-dose pharmacokinetics of amantadine hydrochloride and rimantadine hydrochloride in young and elderly adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:216–221. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClellan K., Perry C.M. Oseltamivir: a review of its use in influenza. Drugs. 2001;61:263–283. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cass L.M., Efthymiopoulos C., Bye A. Pharmacokinetics of zanamivir after intravenous, oral, inhaled or intranasal administration to healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36(Suppl.1):1–11. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alves Galvao M.G., Rocha Crispino Santos M.A., Alves da Cunha A.J. Amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in children and the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002745.pub2. CD002745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu J., Santesso N., Mustafa R. Antivirals for treatment of influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:512–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser L., Hayden F.G. Hospitalizing influenza in adults. In: Swartz M.N., editor. Current clinical topics in infectious diseases. Blackwell Science; Malden: 1999. pp. 112–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyser L.A., Karl M., Nafziger A.N. Comparison of central nervous system adverse effects of amantadine and rimantadine used as sequential prophylaxis of influenza A in elderly nursing home patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1485–1488. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wills R.J. Update on rimatadine's clinical pharmacokinetics. J Respir Dis. 1989;10:s20–s25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Englund J.A., Champlin R.E., Wyde P.R. Common emergence of amantadine- and rimantadine-resistant influenza A viruses in symptomatic immunocompromised adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1418–1424. doi: 10.1086/516358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colman P.M. Influenza virus neuraminidase: structure, antibodies, and inhibitors. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1687–1696. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscona A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1363–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamali A., Holodniy M. Influenza treatment and prophylaxis with neuraminidase inhibitors: a review. Infect Drug Resist. 2013;6:187–198. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S36601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita M. Laninamivir and its prodrug, CS-8958: long-acting neuraminidase inhibitors for the treatment of influenza. Antivir Chem Chemoth. 2010;21:71–84. doi: 10.3851/IMP1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashiwagi S., Watanabe A., Ikematsu H. Laninamivir octanoate for post-exposure prophylaxis of influenza in household contacts: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:740–749. doi: 10.1007/s10156-013-0622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe A., Chang S.C., Kim M.J. Long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate versus oseltamivir for treatment of influenza: A double-blind, randomized, noninferiority clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1167–1175. doi: 10.1086/656802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugaya N., Ohashi Y. Long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate (CS-8958) versus oseltamivir as treatment for children with influenza virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2575–2582. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01755-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koseki N., Kaiho M., Kikuta H. Comparison of the clinical effectiveness of zanamivir and laninamivir octanoate for children with influenza A(H3N2) and B in the 2011-2012 season. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014;8:151–158. doi: 10.1111/irv.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsumi Y., Otabe O., Matsui F. Effect of a single inhalation of laninamivir octanoate in children with influenza. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1431–e1436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe A. A randomized double-blind controlled study of laninamivir compared with oseltamivir for the treatment of influenza in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0460-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He G., Massarella J., Ward P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64-0802. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:471–484. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayner C.R., Bulik C.C., Kamal M.A. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic determinants of oseltamivir efficacy using data from phase 2 inoculation studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3478–3487. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02440-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welliver R., Monto A.S., Carewicz O. Effctiveness of oseltamivir in prevening influenza in household contacts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:748–754. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ison M.G., Szakaly P., Shapira M.Y. Efficacy and safety of oral oseltamivir for influenza prophylaxis in transplant recipients. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:955–964. doi: 10.3851/IMP2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baz M., Abed Y., Papenburg J. Emergence of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1 virus during prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2296–2297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiser L., Wat C., Mills T. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1667–1672. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fry A.M., Goswami D., Nahar K. Efficacy of oseltamivir treatment started within 5 days of symptom onset to reduce influenza illness duration and virus shedding in an urban setting in Bangladesh: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:109–118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acosta E.P., Jester P., Gal P. Oseltamivir dosing for influenza infection in premature neonates. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:563–566. doi: 10.1086/654930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamal M.A., Acosta E.P., Kimberlin D.W. The posology of oseltamivir in infants with influenza infection using a population pharmacokinetic approach. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(3):380–389. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimberlin D.W., Acosta E.P., Prichard M.N. Oseltamivir pharmacokinetics, dosing, and resistance among children aged <2 years with influenza. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:709–720. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitley R.J., Hayden F.G., Reisinger K.S. Oral oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:127–133. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piedra P.A., Schulman K.L., Blumentals W.A. Effects of oseltamivir on influenza-related complications in children with chronic medical conditions. Pediatrics. 2009;124:170–178. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar D., Michaels M.G., Morris M.I. Outcomes from pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in recipients of solid-organ transplants: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:521–526. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70133-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid G., Huprikar S., Patel G. A multicenter evaluation of pandemic influenza A/H1N1 in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15:487–492. doi: 10.1111/tid.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee N., Ison M.G. Diagnosis, management and outcomes of adults hospitalized with influenza. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:143–157. doi: 10.3851/IMP2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee N., Ison M.G. Editorial commentary. ‘Late’ treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors for severely ill patients with influenza: better late than never? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1205–1208. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louie J.K., Yang S., Acosta M. Treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors for critically ill patients with influenza A (H1N1)pdm09. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1198–1204. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muthuri S.G., Venkatesan S., Myles P.R. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:395–404. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beau A.B., Hurault-Delarue C., Vial T. Safety of oseltamivir during pregnancy: a comparative study using the EFEMERIS database. BJOG. 2014;121:895–900. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wollenhaupt M., Chandrasekaran A., Tomianovic D. The safety of oseltamivir in pregnancy: an updated review of post-marketing data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:1035–1042. doi: 10.1002/pds.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saito S., Minakami H., Nakai A. Outcomes of infants exposed to oseltamivir or zanamivir in utero during pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(2):130.e1–130.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beigi R.H., Han K., Venkataramanan R. Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:S84–S88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greer L.G., Leff R.D., Rogers V.L. Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir according to trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:S89–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greer L.G., Leff R.D., Rogers V.L. Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir in breast milk and maternal plasma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:524.e1–524.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee N., Hui D.S., Zuo Z. A prospective intervention study on higher-dose oseltamivir treatment in adults hospitalized with influenza a and B infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1511–1519. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.South East Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research N Effect of double dose oseltamivir on clinical and virological outcomes in children and adults admitted to hospital with severe influenza: double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f3039. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar A. 2013. Viral Clearance with Standard or Triple Dose Oseltamivir Therapy in Critically Ill Patients with Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. ICAAC. Denver, Colorado; 2013:B-1470. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toovey S., Prinssen E.P., Rayner C.R. Post-marketing assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse events in influenza patients treated with oseltamivir: an updated review. Adv Ther. 2012;29:826–848. doi: 10.1007/s12325-012-0050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffman K.B., Demakas A., Erdman C.B. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of oseltamivir in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, 1999-2012. BMJ. 2013;347:f4656. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lam H., Jeffery J., Sitar D.S. Oseltamivir, an influenza neuraminidase inhibitor drug, does not affect the steady-state pharmacokinetic characteristics of cyclosporine, mycophenolate, or tacrolimus in adult renal transplant patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2011;33:699–704. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3182399448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boltz D.A., Aldridge J.R., Jr, Webster R.G. Drugs in development for influenza. Drugs. 2010;70:1349–1362. doi: 10.2165/11537960-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chairat K., Tarning J., White N.J. Pharmacokinetic properties of anti-influenza neuraminidase inhibitors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:119–139. doi: 10.1177/0091270012440280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaiser L., Keene O.N., Hammond J.M. Impact of zanamivir on antibiotic use for respiratory events following acute influenza in adolescents and adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3234–3240. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohno S., Kida H., Mizuguchi M. Efficacy and safety of intravenous peramivir for treatment of seasonal influenza virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4568–4574. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00474-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kohno S., Yen M.Y., Cheong H.J. Phase III randomized, double-blind study comparing single-dose intravenous peramivir with oral oseltamivir in patients with seasonal influenza virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5267–5276. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00360-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arya V., Carter W.W., Robertson S.M. The role of clinical pharmacology in supporting the emergency use authorization of an unapproved anti-influenza drug, peramivir. Clin Pharmacol Therapeut. 2010;88:587–589. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thomas B., Hollister A.S., Muczynski K.A. Peramivir clearance in continuous renal replacement therapy. Hemodial Int. 2010;14:339–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.CDC . 2009. Emergency Use Authorization of Peramivir IV: Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunn C.J., Goa K.L. Zanamivir: a review of its use in influenza. Drugs. 1999;58:761–784. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Diggory P., Fernandez C., Humphrey A. Comparison of elderly people's technique in using two dry powder inhalers to deliver zanamivir: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:577–579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marty F.M., Man C.Y., van der Horst C. Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous zanamivir treatment in hospitalized adults with influenza: an open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:542–550. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weller S., Jones L.S., Lou Y. Pharmacokinetics of zanamivir following intravenous administration to subjects with and without renal impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2967–2971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02330-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hedrick J.A., Barzilai A., Behre U. Zanamivir for treatment of symptomatic influenza A and B infection in children five to twelve years of age: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:410–417. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lalezari J., Campion K., Keene O. Zanamivir for the treatment of influenza A and B infection in high-risk patients – a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:212–217. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murphy K.R., Eivindson A., Pauksens K. Efficacy and safety of inhaled zanamivir for the treatment of influenza in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Clin Drug Invest. 2000;20:337–349. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chan-Tack K.M., Gao A., Himaya A.C. Clinical experience with intravenous zanamivir under an emergency investigational new drug program in the United States. Infect Dis. 2013;207:196–198. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duval X., van der Werf S., Blanchon T. Efficacy of oseltamivir-zanamivir combination compared to each monotherapy for seasonal influenza: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nguyen J.T., Hoopes J.D., Le M.H. Triple combination of amantadine, ribavirin, and oseltamivir is highly active and synergistic against drug resistant influenza virus strains in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hurt A.C., Chotpitayasunondh T., Cox N.J. Antiviral resistance during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic: public health, laboratory, and clinical perspectives. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:240–248. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen H.T., Fry A.M., Gubareva L.V. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:159–173. doi: 10.3851/IMP2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wray S.K., Gilbert B.E., Knight V. Effect of ribavirin triphosphate on primer generation and elongation during influenza virus transcription in vitro. Antiviral Res. 1985;5:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(85)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wray S.K., Gilbert B.E., Noall M.W. Mode of action of ribavirin: effect of nucleotide pool alterations on influenza virus ribonucleoprotein synthesis. Antiviral Res. 1985;5:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(85)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paroni R., Del Puppo M., Borghi C. Pharmacokinetics of ribavirin and urinary excretion of the major metabolite 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide in normal volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1989;27:302–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chemaly R.F., Torres H.A., Munsell M.F. An adaptive randomized trial of an intermittent dosing schedule of aerosolized ribavirin in patients with cancer and respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1367–1371. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pickering L.K., editor. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. Respiratory Syncytial Virus; pp. 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodriguez W.J., Hall C.B., Welliver R. Efficacy and safety of aerosolized ribavirin in young children hospitalized with influenza: a double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1994;125:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Glanville A.R., Scott A.I., Morton J.M. Intravenous ribavirin is a safe and cost-effective treatment for respiratory syncytial virus infection after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2114–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shah J.N., Chemaly R.F. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2755–2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-263400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marcelin J.R., Wilson J.W., Razonable R.R. Transplant Infectious Diseases S. Oral ribavirin therapy for respiratory syncytial virus infections in moderately to severely immunocompromised patients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:242–250. doi: 10.1111/tid.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ison M.G. Respiratory viral infections in transplant recipients. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:627–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seo S., Englund J.A., Nguyen J.T. Combination therapy with amantadine, oseltamivir and ribavirin for influenza A infection: safety and pharmacokinetics. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:377–386. doi: 10.3851/IMP2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nguyen J.T., Smee D.F., Barnard D.L. Efficacy of combined therapy with amantadine, oseltamivir, and ribavirin in vivo against susceptible and amantadine-resistant influenza A viruses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]